An introduction to exemplar research: a definition, rationale, and conceptual issues

- PMID: 24338906

- DOI: 10.1002/cad.20045

The exemplar methodology represents a useful yet underutilized approach to studying developmental constructs. It features an approach to research whereby individuals, entities, or programs that exemplify the construct of interest in a particularly intense or highly developed manner compose the study sample. Accordingly, it reveals what the upper ends of development look like in practice. Utilizing the exemplar methodology allows researchers to glimpse not only what is but also what is possible with regard to the development of a particular characteristic. The present chapter includes a definition of the exemplar methodology, a discussion of some of key conceptual issues to consider when employing it in empirical studies, and a brief overview of the other chapters featured in this volume.

© Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Publication types

- Introductory Journal Article

- Biomedical Research / methods*

- Biomedical Research / standards

- Psychology, Child / methods*

- Psychology, Child / standards

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2021

Interpersonal relationships drive successful team science: an exemplary case-based study

- Hannah B. Love ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0011-1328 1 ,

- Jennifer E. Cross ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5582-4192 2 ,

- Bailey Fosdick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3736-2219 2 ,

- Kevin R. Crooks 2 ,

- Susan VandeWoude 2 &

- Ellen R. Fisher 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 106 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

9141 Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Complex networks

- Science, technology and society

Scientists are increasingly charged with solving complex societal, health, and environmental problems. These systemic problems require teams of expert scientists to tackle research questions through collaboration, coordination, creation of shared terminology, and complex social and intellectual processes. Despite the essential need for such interdisciplinary interactions, little research has examined the impact of scientific team support measures like training, facilitation, team building, and expertise. The literature is clear that solving complex problems requires more than contributory expertise, expertise required to contribute to a field or discipline. It also requires interactional expertise, socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group. These forms of expertise are often tacit and therefore difficult to access, and studies about how they are intertwined are nearly non-existent. Most of the published work in this area utilises archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment. This study addresses the call of numerous studies to use mixed-methods and social network analysis to investigate scientific team formation and success. This longitudinal case-based study evaluates the following question: How are scientific productivity, advice, and mentoring networks intertwined on a successful interdisciplinary scientific team? This study used applied social network surveys, participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and historical social network data to assess this specific team and assessed processes and practices to train new scientists over a 15-year period. Four major implications arose from our analysis: (1) interactional expertise and contributory expertise are intertwined in the process of scientific discovery; (2) team size and interdisciplinary knowledge effectively and efficiently train early career scientists; (3) integration of teaching/training, research/discovery, and extension/engagement enhances outcomes; and, (4) interdisciplinary scientific progress benefits significantly when interpersonal relationships among scientists from diverse disciplines are formed. This case-based study increases understanding of the development and processes of an exemplary team and provides valuable insights about interactions that enhance scientific expertise to train interdisciplinary scientists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards understanding the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful collaborations: a case-based team science study

Hannah B. Love, Bailey K. Fosdick, … Ellen R. Fisher

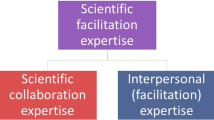

Science facilitation: navigating the intersection of intellectual and interpersonal expertise in scientific collaboration

Amanda E. Cravens, Megan S. Jones, … Hannah B. Love

A framework for developing team science expertise using a reflective-reflexive design method (R2DM)

Gaetano R. Lotrecchiano, L. Michelle Bennett & Yianna Vovides

Introduction

Scientists are increasingly charged with solving complex and large-scale societal, health, and environmental challenges (Read et al., 2016 ; Stokols et al., 2008 ). These systemic problems require interdisciplinary teams to tackle research questions through collaboration, coordination, creation of shared terminology, and complex social and intellectual processes (Barge and Shockley-Zalabak, 2008 ; De Montjoye et al., 2014 ; Fiore, 2008 ). Thus, to successfully approach complex research questions, scientific teams must synthesise knowledge from different disciplines, create a shared terminology, and engage members of a diverse research community (Matthews et al., 2019 ; Read et al., 2016 ). Despite significant time, energy, and money spent on collaboration and interdisciplinary projects, little research has examined the impact of scientific team support measures like training, facilitation, team building, and team performance metrics (Falk-Krzesinski et al., 2011 ; Klein et al., 2009 ).

Studies examining the development of scientific teaming skills that result in successful outcomes are sparse (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). The earliest studies of collaboration in science used bibliometric data to search for predictors of team success such as team diversity, size, geographical proximity, inter-university collaboration, and repeat collaborations (Borner et al., 2010 ; Cummings and Kiesler, 2008 ; Wuchty et al., 2007 ). Building from these studies, current research focuses on team processes. Literature suggests that to successfully frame a scientific problem, a team must also engage emotionally and interact effectively (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ) and that scientific collaboration involve consideration of the process, collaborator, human capital, and other factors that define an scientific collaboration (Bozeman et al., 2013 ; Hall et al., 2019 ; Lee and Bozeman, 2005 ). Similarly, Zhang et al. ( 2020 ) used social network analysis to examine how emotional intelligence is transmitted to team outcomes through team processes. Still more research is needed, and Hall et al. ( 2018 ) called for team science studies that use longitudinal designs and mixed-methods to examine project teams as they develop in order to move beyond bibliometric measures of success and to explore the complex, interacting features in real-world teams.

Fiore ( 2008 ) explained that much of what we know about the science of team science (SciTS), training scientists and team learning in productive team interactions, is anecdotal and not the result of systematic investigation (Fiore, 2008 ). Over a decade later there is still a paucity of research on how scientific teams develop the type of expertise they need to create new knowledge and further scientific discovery (Bammer et al., 2020 ). Bammer et al. ( 2020 ) has identified and defined two types of expertise: (1) contributory expertise, expertise required to make a contribution to a field or discipline (Collins and Evans, 2007 ); and (2) interactional expertise, socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group (Bammer et al., 2020 ). These forms of expertise are often tacit, codified by “learning-by-doing,” and augmented from project to project; therefore, they are difficult to measure and rarely documented in literature (Bammer et al., 2020 ).

Wooten et al. ( 2014 ) outlined three types of evaluations—developmental, process, and outcome—needed to understand how teams develop and to provide information about their future success (Wooten et al., 2014 ). A developmental evaluation focuses on the continuous process of team development, and a process evaluation focuses on team interactions, meetings, and engagement (Patton, 2011 ). Both development and process evaluations have the common goal of understanding the team’s future success or failures, also known as the team’s outcomes (e.g., grants, publications, and awards) (Patton, 2011 ). The majority of published work on outcome metrics is evaluated by archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment (Hall et al., 2018 ). Albeit informative, these studies are based upon limited outcome metrics such as publications and represent only a selective sampling of teams that have achieved success. To collect these three types of evaluation data, it is recommended to engage mixed-methods research such as a combination of social network analysis (SNA), participant observation, surveys, and interviews, although these approaches have not been widely employed (Bennett, 2011 ; Borner et al., 2010 ; Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ).

A few key studies have provided insight into successful collaboration strategies. Duhigg ( 2016 ) found that successful teams provided psychological safety, had dependable team members, and relied upon clear roles and structures. In addition, successful teams had meaningful goals, and team members felt like they could make an impact through their work on the team (Duhigg, 2016 ). Similarly, Collins ( 2001 ) explained that in business teams, moving from “Good to Great” required more than selecting the right people; the team needed development and training to achieve their goals (Collins, 2001 ). Woolley et al. ( 2010 ) found that it is not collective intelligence that builds the most effective teams, but rather, how teams interact that predicts their success (Woolley et al., 2010 ). The three traits they identified as most associated with team success included even turn-taking, social sensitivity, and proportion female (when women’s representation nears parity with men) (Woolley et al., 2010 ). Finally, Bammer et al. ( 2020 ) recommended creating a knowledge bank to strengthen knowledge about contributary and interactional expertise in scientific literature to solve complex problems. Collectively, these studies argue that the key to collective intelligence is highly reliant on interpersonal relationships to drive team success.

This article reports on a longitudinal case-based study of an exemplary interdisciplinary scientific team that has been successful in typical scientific outputs, including competing for research awards, publishing academic articles, and training and developing scientists. This analysis examines how scientific productivity, advice, and mentoring networks intertwined to promote team success. The study highlights how the team’s processes to train scientists (e.g., developing mentoring and advice networks) have propelled their scientific productivity, fulfilled the University’s land grant mission (i.e., emphasises research/discovery; education/training; and outreach/engagement) and created contributory and interactional expertise on the team. Team dynamics were evaluated by social network surveys, participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and historical social network data over 15 years to develop theory and evaluate complex relationships contributing to team success (Dozier et al., 2014 ; Greenwood, 1993 ).

Case study selection

The [BLIND] Science of team science (SciTS) team consisted of scientists trained in four different disciplines and research administrators. The SciTS team monitored twenty-five interdisciplinary teams at [BLIND] for 5 years from initiation of team formation to identify team dynamics that related to team success. This case is thus presented as part of an ongoing study of the 25 teams, supported by efforts through the [BLINDED] to encourage and enhance collaborative, interdisciplinary research and scholarship. Team outcomes were recorded annually and included extramural awards, publications, presentations, students trained, and training outcomes. An exemplary case-based study is appropriate when the case is unusual, the issues are theoretically important, and there are practical implications (Yin, 2017 ). Further, cases can illustrate examples of expertise and provide guidance to future teams (Bammer et al., 2020 ). An “exemplary team designation” was given to this team by the SciTS evaluators. Metrics used to designate an exemplary team included: team outcomes; highly interdisciplinary research; longevity of the team; fulfilment of all aspects of the land grant mission (research/discovery; education/training; and outreach/engagement); integration of team members; and use of external reviewers.

Social network survey

The exemplary team included Principle Investigators (PIs), postdoctoral researchers (postdocs), graduate students, undergraduate students, and active collaborators external to the University. The entire team was surveyed annually 2015–2019 about the extent and type of collaboration with other team members. In 2015, the team was asked about prior collaborations, and in subsequent years they were asked about additional interactions since joining the team. Possible collaborative activities included research publications, scientific presentations, grant proposals, and serving on student committees. Team members were also asked the types of relationships they had with each team member, including learning, leadership, mentoring, advice, friendship, and having fun (Supplementary 2 ). Data were collected using a voluntary online survey tool (Organisational Network Analysis Surveys). All subjects were identified by name on the social network survey but are not identified in any network diagrams or analyses. SNA software programmes R Studio (R Studio Team, 2020 ) and UCINET (Borgatti et al., 2014 ) were used to analyse data and Visone (Brandes and Wagner, 2011 ) was used to create visualisations. The response rate for the survey was 94% in 2015, 83% in 2016, 95% in 2017, and 81% in 2018. All data collection methods were performed with the informed consent of the participants and followed Institutional Review Board protocol #19-8622H.

Data from the social network survey were combined to create three different network measures: scientific productivity, mentoring, and advice. The scientific productivity network was a combination of four survey measures: research/consulting, grants, publications, and serving on student committees. Scientific productivity represents a form of cognitive or contributory expertise: expertise required to contribute to a field or discipline (Bammer et al., 2020 ; Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ). The mentoring and advice networks were created from social network survey questions: “who is your mentor?” and “who do you go to for advice?”, respectively. Mentor and advice are tacit forms of interactional expertise: socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group (Collins and Evans, 2007 ). Other studies have also found a connection between social characteristics of interdisciplinary work and other factors like productivity, career paths, and a group’s ability to exchange information, interact, and explore together (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ).

Social network data were summarised using average degree, sometimes split into indegree and outdegree. Outdegree is a measure of how many team members a given individual reported getting advice, or mentorship, from. Similarly, the indegree of an individual is a measure of how many other team members reported receiving advice, or mentorship, from that person. Average degree is the average number of immediate connections (i.e., indegree plus outdegree) for a person in a network (Giuffre, 2013 ; R. Hanneman and Riddle, 2005 a, 2005 b). To further explore the mentoring and advice networks, we calculated the average degree/outdegree/indegree of postdocs, graduate students, and faculty separately to directly compare demographic groups.

The advice, mentoring, and scientific productivity networks were directly compared using the Pearson correlation between the corresponding network adjacency matrices. We predicted a positive correlation between the advice, mentoring, and scientific productivity matrices. Statistical significance ( p < 0.05) of correlations was assessed with the network permutation-based method Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP) (R. A. Hanneman and Riddle, 2005 a, 2005 b).

Historical social network data

A historical network survey was created to determine how the connections in the network formed, developed, and changed from project-to-project. The historical social network was constructed from three forms of data: interviews with the PIs, a historical narrative written by the PIs describing the team formation process, and team rosters that listed the 81 team members since the inception of the team.

Retrospective team survey

A retrospective team survey was administered at the end of the study to determine what skills team members developed and codified through participating on the team, how membership on the team supported members personally and professionally, and their favourite aspects of the team. The survey was sent to 22 members from the 2018 team roster using Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs, 2005 ) with an 86% response rate.

Two semi-structured, one-hour interviews were conducted with two PIs in 2018 to learn about the history of the team. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Participant observations

Participant observation was conducted from 2015–2019 at four annual three-day, off-campus retreats and 1–2 additional meetings each year. Students, PIs, external collaborators, and families were all invited to attend the retreats and meetings. Field notes about team interactions were recorded immediately after each interaction. The analytic field notes captured how team members interacted across disciplines, tackled scientific problems, and engaged with others at different career stages. Analysis occurred as field notes were written, during observations, and again during data analysis.

An exemplary team

The SciTS Team identified one team from the larger study and designated it as exemplary based on six (tacit and non-tacit) elements. First, the team had outstanding team outcomes. From 2004–2018, notable accomplishments include 33 extramural awards totalling over $5.6 million, including two large federal awards totalling over $4.5 million; 58 peer-reviewed publications with 39 different universities, 13 state agencies, and 11 other organisations; 141 presentations, 21 graduate students and 15 postdocs trained; and receipt of an [BLIND]institution-wide Interdisciplinary Scholarship Team Award. Participants received many individual honours, including one of the PIs being named to the National Academy of Sciences.

Second, this interdisciplinary team combined scientific expertise from many different backgrounds, including ecologists, wildlife biologists, evolutionary biologists, geneticists, veterinarians, and numerous collaborators. Principal Investigators were housed in five main universities: Colorado State University, University of Wyoming, University of Minnesota, University of California-Davis, and University of Tasmania. They also engaged collaborators from national and international universities, federal, state, and local governmental agencies, veterinary centres, and animal shelters. Collectively, team members represented 39 different universities, 11 federal agencies, 13 state agencies, and 11 other organisations listed on their peer-reviewed publications. The team has published globally with co-authors from every continent but Antarctica.

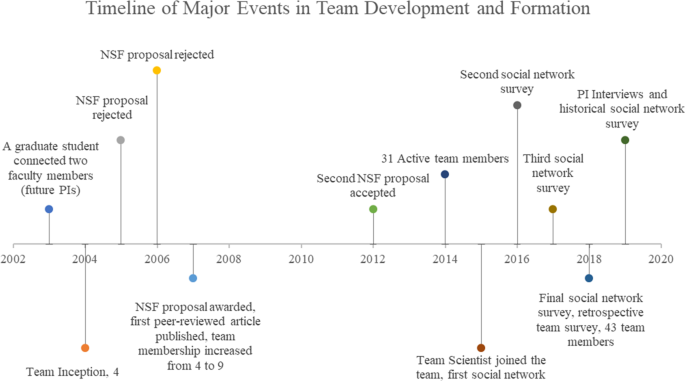

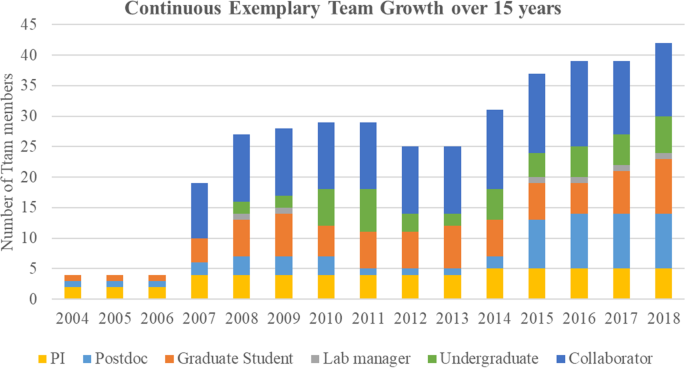

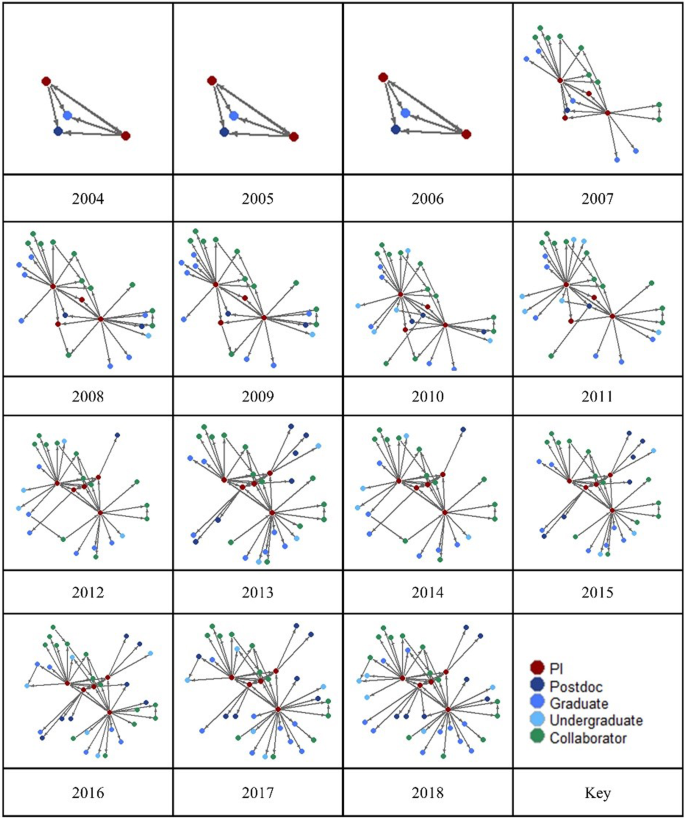

The third element identified was the team’s 15-year history and how they evolved project-to-project (Supplementary Video S1 ). In 2003, a graduate student proposed a collaborative research project between two faculty members who became two of the founding team PIs (Fig. 1 ). The team was formed in 2004 with four members—two faculty PIs, a postdoc, and a Ph.D. student (Fig. 1 ). Initial grant proposals submitted in 2005 and 2006 were not funded; however, in 2007, the team received a large federal research award from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The team roster increased from four to nine, and a second large expansion occurred after receipt of another NSF award in 2012. By 2014, membership increased to 31 people, and at the end of analysis in 2018, the roster comprised 43 members. Over the course of observation, 81 different individuals, including students, faculty, and collaborators, had participated in research activities supported by the team.

Significant events occurring over 15 years during the development and formation of an exemplary team.

The fourth reason this team was deemed exemplary was because it intertwined the components in the Land Grand mission, including research/discovery, teaching/training, and extension/engagement (Fig. 2 ). The team included undergraduates conducting research and presenting at conferences, graduate students working in multiple labs, and postdocs mentoring all the researchers in the lab. An external advisor said at the end of a retreat, “It’s really cool that students are part of the conversations that are both good/bad/ugly etc. It is not just good. It is not just one-on-one conversations. They hear it all.” A Ph.D. student wrote in the Retrospective Survey about the skills he developed: “I have developed the ability to talk about my research to people outside my field. I have also worked on broadening my understanding of disease ecology as a whole. I have been given the opportunity [to] begin placing my work in the larger framework of ecosystem health.” Faculty also wrote about what they learned, “[I] Learned from leadership of team (especially [blinded], and other PIs) how to develop and conduct research team work well - am using what I am learning to develop new research teams…. how to develop and nurture and respect interpersonal relationships and diversity of opinions. This has been an amazing experience, to be part of a well-functioning team, and to examine why and how that is maintained”

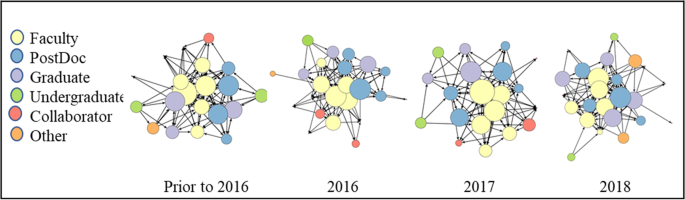

The team grew from 4 members in 2004 to 42 members in 2018. Much of the growth occurred by the addition of students and external collaborators.

Fifth, the team was effective at onboarding and integrating new members. To do so, they used two key strategies (Fig. 3 ). First, 15 of the students held co-advised graduate research positions. This shared model of mentorship provided students with opportunities to work in multiple labs, collaborate with additional team members, and gain a broader academic experience. A Ph.D. student wrote in the Retrospective Survey about the skills she learned from being a member of the team: “Leadership skills, communicating science to those in other fields, scientific writing skills, technical laboratory skills, interpersonal communication skills, data sharing experience, and many others.” The shared model supported the team’s interdisciplinary mission by providing opportunities to train future scientists to communicate, network, and conduct research across disciplines. Second, as team members developed through participation on the team, they assumed more mature scientific roles. Fourteen members of the team changed positions within the team. Many of these transitions were from undergraduate student to Ph.D. student or Ph.D. student to postdoctoral researcher. In 2012, one postdoc became a PI on the grant.

Social network diagrams of team growth and development from 2004–2018. This network reports onboarding and integration of all members, including their primary position when they joined the team. The nodes are sized by average degree (see text). Colours denote different roles on the team.

Finally, the 2018 team retreat included external reviewers. At the end of 2018 team retreat, they were asked if they had any feedback for the team. An external reviewer said: “You can check all of the boxes of a good team.”; “This is a dream team.”; “I am really impressed.”. Another external reviewer said:

The ambitiousness to execute the scope of the project, to have this many PIs, to be able to communicate; the opportunities for new insights; and the opportunities it presents for trainees are rare. There are a lot of people exposed in this. This is a unique experience for someone in training. And it extends to elementary school. I don’t think there are many projects that have this type of scope. I was impressed with just the idea that scientists are taking this across such a great scope and taking on such great questions.

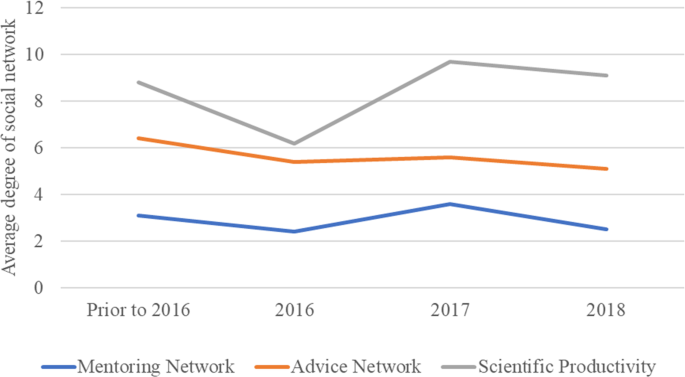

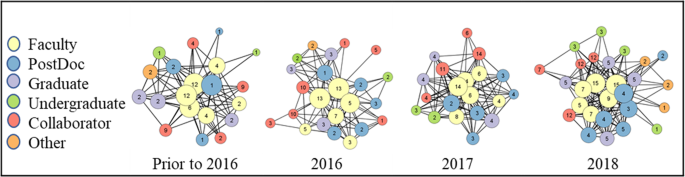

Scientific productivity network

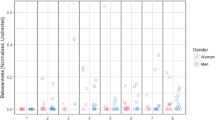

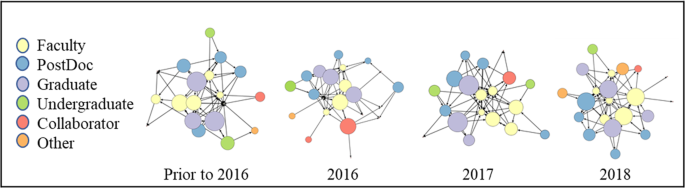

Prior to 2016, the average degree of the scientific productivity network was 8.8 (Fig. 4 ). In 2016, four faculty nodes were in the core of the network, and the periphery nodes included graduate students, postdocs, and external collaborators (Fig. 5 ). The average degree dropped slightly to 6.2 when the team integrated new members and re-formed around new roles and responsibilities on a new grant (Fig. 4 ). In 2017, the average degree peaked at 9.7 (Fig. 4 ) and faculty were still core, but graduate students and postdocs were more central than before (Fig. 5 ). During this time, productivity was at its highest as team members were working together to meet the objectives of a 5-year interdisciplinary NSF award. The network evolved further in 2018; two of the postdoc nodes overlapped with the faculty nodes in the core of the network (Fig. 5 ).

Average degree of social networks diagrams (mentoring, advice, scientific productivity) indicated strong social ties among team members.

Social network measures of productivity (research/consulting, grants, publications, and serving on student committees) were recorded over time. Each node represents a person on the team, and nodes are sized by average degree (see text). Colours denote different roles on the team. The node label indicates the number of years a person has been part of the team.

Mentoring is integral in the collaborative network

Team members reported between an average of 2.4–3.1 mentors (average outdegree) each year on the team (Fig. 6 ). More specifically, graduate students reported 6.0–7.7 mentors, whereas postdocs reported 2.4–3.5 mentors (Table 1 ). Faculty team members reported having an average of 2.2 to 4.3 mentors on the team (Table 1 ), with the highest average outdegree in 2018.

This diagram was created by using participant answers to the social network question, “who is your mentor?” Each circle or node represents a person on the team. The nodes are sized by outdegree to show who reported receiving mentorship. Node size indicates how many mentors an individual reported, and arrows indicate nodes that served as mentors. Colours denote different roles on the team.

The highest indegree for an individual was the lead PI, with an indegree ranging from 13 to 14 each year (i.e., each year, 13–14 team members reported this individual provided mentorship). In response to an interview question about this PIs favourite part of the team, this individual said, “…and of course, I really like the mentorship of the students…They are initially naive, and some people are initially underconfident, but eventually they become fluent in their subject area.” Many students wrote about the mentoring they received from the team. An undergraduate student wrote:

I have improved my communication skills after needing to collaborate with several mentors across different time zones. I’ve also improved willingness to ask questions when I don’t understand a concept. I’ve also learned what concepts I find basic in my field that others outside my discipline are less familiar with.

Faculty also wrote about the mentoring they received, such as, “I continually learn from members in the team and mentorship by the more experienced members has supported my own career progression.”

Advice is integral in the collaborative network

In the 2015–2017 advice network diagrams, the faculty were tightly clustered (Fig. 7 ). In 2018, the cluster separated as postdocs and graduate students joined the centre of the network. On average, team members reported 5.1 to 6.4 people they could go to for advice (Fig. 4 ).

This diagram was created by using participant answers to the social network question, “who do you go to for advice?” Each circle or node represents a person on the team. The nodes are sized by outdegree to show who reported receiving mentorship. Node size indicates how many mentors an individual reported, and arrows indicate nodes that served as mentors. Colours denote different roles on the team.

In a survey, faculty responded to the question, “How has the team supported you personally and professionally?” One faculty member wrote: “Just today I asked three members of the team for professional advice! And got a thoughtful and prompt response from all.” Another team member wrote: “Being a member of the…team has allowed me to develop skills in statistical analysis, scientific writing, and critical thinking. This team has opened my eyes to what is possible to achieve with science and has provided me with opportunities to network and expand my horizons both within the field of study and outside of it.” These quotes further suggest that the mentoring and advice from a large interdisciplinary team were important to train future scientists.

Interpersonal relationships as driver for scientific productivity

The mentoring and advice networks supported and built on the scientific productivity network and vice versa. The correlation between the collaboration, mentoring, and advice networks would not be possible if the networks were not intertwined. In the retrospective survey, a faculty member described how tacit interpersonal relationships were correlated with their scientific productivity:

Being a part of this grant has helped me both personally and professionally by teaching me new skills (disease ecology, team dynamics), developing friendships/mentors from the team, and strengthening my CV and dossier for promotion to early full professorship.

A Ph.D. student also described how the relationships on the large team propelled their research.

Membership on this team has provided me with a lot of mentorship that I would not otherwise receive were I not working on a large multi-disciplinary for my doctoral research. It has also allowed me to network more effectively.

Between 2015 and 2018, the mentor and advice networks were significantly correlated with the scientific productivity network, demonstrating that personal relationships are associated with scientific collaboration (Table 2 ).

To date, the literature examining successful interdisciplinary scientific team skills that result in successful outcomes is sparse (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). The majority of published work in this area is evaluated by archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment (Hall et al., 2018 ). This study answers the call of numerous researchers to use mixed-methods and SNA to investigate scientific teams (Bennett, 2011 ; Borner et al., 2010 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ; Wooten et al., 2015 ). Our case-based study also increases understanding of the development and processes of an exemplary team by providing valuable insights about how the interactions that enhance scientific productivity are synergistic with the interactions that train future scientists. There are four major implications of our findings: (1) interactional and contributory expertise are intertwined; (2) team size, tacit knowledge gained from previous project, and interdisciplinary knowledge were used to effectively and efficiently train scientists; (3) the team increased scientific productivity through interpersonal relationships; and (4) the team fulfilled the land grant mission of the University by integrating teaching/training, research/discovery, and extension/engagement into the team’s activities.

Interactive and contributory expertise are intertwined

Previous literature on scientific teams has found that great teams are not built on scientific expertise alone, but on the processes and interactions that build psychological safety, create a shared language, engage members emotionally, and promote effective interactions (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Hall et al., 2019 ; Senge, 1991 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). The team highlighted in this report created a shared language and vision through the mentoring and advice networks that helped fuel the team’s scientific productivity (Hall et al., 2012 ). To solve complex problems requires more than contributory expertise, it also requires interactional expertise (Bammer et al., 2020 ). These forms of expertise are often tacit and internalised through the process of becoming an expert in a field of study (Collins and Evans, 2007 ). Learning-by-doing is augmented from project-to-project, with expertise codified over time (Bammer et al., 2020 ). Further, cognitive, emotional, and interactions are key components of successful collaborations (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Bozeman et al., 2013 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). Using social network analysis, our case-based analysis found that the mentoring and advice ties were intertwined with the scientific productivity network.

Training scientists to be experts

The Retrospective Survey asked what personal and professional skills respondents learned from being a member of a team. We hypothesised that many respondents would report tangible skills. Surprisingly, 82% of the open-ended responses were about tacit skills. Students frequently had co-advised graduate research positions, worked in multiple labs, and communicated regularly with practitioners. Moreover, the team translated research to different disciplines within the team, mentored others, and managed interpersonal conflicts. These interactions built expertise because training was not limited to research in a single lab or only in an academic setting. Simple, discrete, and codified knowledge is relatively easy to transfer; however, teams need stronger relationships to gain complex and tacit knowledge, (Attewell, 1992 ; Simonin, 1999 ). On this team, interactions and the ability to practice communication were especially influential for students, junior scientists, and new members. These individuals provided survey responses reporting they learned a wide variety of skills ranging from leadership, scientific and interpersonal communication, networking across disciplines, scientific writing, laboratory techniques, and data sharing standards. Further, respondents noted they had gained experience in developing, nurturing, and respecting interpersonal relationships and diversity of opinions. This was reinforced with participant observation data. In other interdisciplinary groups studied in conjunction with this exemplary team, students were not typically exposed to the inner workings of the team such as leadership meetings. On this team, students were exposed to all conversations, which became an important component of the mentoring and advice structure, serving to train future scientists in all aspects of team integration and leadership development. Belonging to this large interdisciplinary team was effectively training, building, and structuring the team.

Interpersonal relationships increase scientific productivity

Longevity of relationships is an important factor in creating social cohesion, reducing uncertainty, and increasing reliability and reciprocity (Baum et al., 2007 ; Gulati and Gargiulo, 1999 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Previous literature has, however, rarely documented the importance of time in building the structure of the network (Phelps et al., 2012 ) and few longitudinal studies of scientific teams exist. Further, it has long been hypothesised that greater interaction among people increases the quality and innovativeness of ideas generated, which may in turn increase productivity (Cimenler et al., 2016 ). Our case-based study found that the mentoring and advice ties existed in a symbiotic relationship with the scientific productivity network where the practices of the team were simultaneously training scientists. This aligns with social network literature that interactions can structure the social network and the network structure influences interactions (Henry, 2009 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Second, intentional mentoring programmes have demonstrated a positive relationship between interdisciplinary mentoring and increased research productivity outcomes such as grant funding and publications (Spence et al., 2018 ). Finally, this finding also aligns with literature on the generation of new knowledge (Phelps et al., 2012 ). Knowledge creation has traditionally been framed in terms of individual creativity, but recent studies have placed more emphasis on how the contribution of social dynamics are influential in explaining this process (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Csikszentmihalyi, 1998 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ; Sawyer, 2003 ; Zhang et al., 2009 ). Thus, while we might think that science drives the team, in this case-based study, the team’s interpersonal relationships were the driver of the team’s scientific productivity.

Fulfilling the land grant mission

As noted above, this exemplary team fulfilled all three goals of the land grant mission. First, the team was training scientists at all levels, from undergraduate students, to graduate students, postdocs, new faculty, and external collaborators, including community partners. In many instances, the training and mentoring was structured in a vertically integrated manner. For example, postdocs were training graduate and undergraduate students, typical of many teams. In addition to the “top-down” scenarios, however, the team also encouraged training that went from the bottom up as well. Effectively, this is a hallmark of successful teams in other sectors such as emergency responders and elite military teams – whomever has the knowledge to drive the issue at hand is the effective “leader” in that mission (Kotler and Wheal, 2008 ). Second, the team excelled in research and discovery, partnering with a diversity of external collaborators to do so. This created a network structure wherein the team clearly utilised the collaborators for mentoring and advice. Organisations with a core-periphery network structure like this team have been reported to be more creative because ties on the periphery, such as external collaborators, can span boundaries and access diverse information (Perry-Smith, 2006 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Finally, because the team’s collaborators included community partners and practitioners, they were also influencing policy and practice. This resulted in an overall greater impact for the team’s science and allowed them to tailor their research to best meet the needs of society (Barge and Shockley-Zalabak, 2008 ).

Future research

This study provides a unique contribution to team science literature because it longitudinally studied the development and processes of a successful interdisciplinary team (Wooten et al., 2014 ). Future research on the elements of effective interdisciplinary teaming is required in five key areas. First, identification of best practices that inhibit or support teams is necessary (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). Second, previous research has found that small teams are best at disrupting science with new ideas and opportunities (Wu et al., 2019 ); however, practices large teams use to create new knowledge have been poorly documented. Third, successful training concepts for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers need additional consideration (Knowlton et al., 2014 ; Ryan et al., 2012 ; Sarraj et al., 2017 ). Fourth, we hypothesise that graduate students act as bridges in teams to connect scientific disciplines and prevent clustering the network. Future research should investigate the role of graduate students in creating knowledge through interdisciplinary teams. Finally, additional research is needed to better recognise and reward scientists who undertake integration and implementation (Bammer et al., 2020 ).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available in the Mountain Scholar repository, https://doi.org/10.25675/10217/214187

Attewell P (1992) Technology diffusion and organizational learning: the case of business computing. Organ Sci 3(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.1.1

Article Google Scholar

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D, Neuhauser L, Midgley G, Klein JT, … Richardson GP (2020). Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Barge JK, Shockley-Zalabak P (2008) Engaged scholarship and the creation of useful organizational knowledge. J Appl Commun Res 36(3):251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880802172277

Baum JAC, McEvily B, Rowley T (2007) Better with age? Tie longevity and the performance implications of bridging and closure. SSRN (vol. 23). INFORMS. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1032282

Bennett ML (2011) Collaboration and team science: a field guide-team science toolkit. Retrieved February 19, 2019, from https://www.teamsciencetoolkit.cancer.gov/Public/TSResourceTool.aspx?tid=1&rid=267

Boix Mansilla V, Lamont M, Sato K (2016) Shared cognitive–emotional–interactional platforms: markers and conditions for successful interdisciplinary collaborations. Sci Technol Human Value 41(4):571–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915614103

Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC (2014) UCINET. Encyclopedia of social network analysis and mining. Springer New York, New York, NY, 10.1007/978-1-4614-6170-8_316

Google Scholar

Borner K, Contractor N, Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Fiore SM, Hall KL, Keyton J, Uzzi B (2010). A multi-level systems perspective for the science. Sci Transl Med 2: 49

Bozeman B, Fay D, Slade CP (2013, February 28). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: the-state-of-the-art. J Technol Transf https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9281-8

Brandes U, Wagner D (2011) Analysis and visualization of social networks. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 321–340. 10.1007/978-3-642-18638-7_15

Cimenler O, Reeves KA, Skvoretz J, Oztekin A (2016) A causal analytic model to evaluate the impact of researchers’ individual innovativeness on their collaborative outputs. J Model Manag 11(2):585–611

Collins H, Evans R (2007) Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Collins JC (2001) Good to great. HarperBusiness, New York, NY

Csikszentmihalyi M (1998) Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In: Sternberg R (ed) Handbook of creativity (pp. 313–336. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807916.018

Cummings JN, Kiesler S (2008) Who collaborates successfully? prior experience reduces collaboration barriers in distributed interdisciplinary research. Cscw: 2008 Acm conference on computer supported cooperative work, Conference Proceedings, pp. 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460633

De Montjoye YA, Stopczynski A, Shmueli E, Pentland A, Lehmann S (2014) The strength of the strongest ties in collaborative problem solving. Sci Rep 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05277

Dozier AM, Martina CA, O’Dell NL, Fogg TT, Lurie SJ, Rubinstein EP, Pearson TA (2014) Identifying emerging research collaborations and networks: method development. Eval Health Prof 37(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713501693

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Duhigg Ch (2016) What google learned from its quest to build the perfect team-The New York Times. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Contractor N, Fiore SM, Hall KL, Kane C, Keyton J, Trochim W (2011) Mapping a research agenda for the science of team science. Res Eval 20(2):145–158. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X12941371876580

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fiore SM (2008) Interdisciplinarity as teamwork. Small Group Res 39(3):251–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408317797

Giuffre K (2013) Communities and networks: using social network analysis to rethink urban and community studies, 1st edn. Polity Press, Cambridge MA, 10.1177/0042098015621842

Greenwood RE (1993) The case study approach. Bus Commun Q 56(4):46–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056999305600409

Gulati R, Gargiulo M (1999) Where do interorganizational networks come from? Am J Sociol 104(5):1439–1493. https://doi.org/10.1086/210179

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Croyle RT (2019) Strategies for team science success: handbook of evidence-based principles for cross-disciplinary science and practical lessons learned from health researchers. Springer Nature, Switzerland

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Huang GC, Serrano KJ, Rice EL, Tsakraklides SP, Fiore SM (2018) The science of team science: a review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. Am Psychol 73(4):532–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000319

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Stipelman BA, Stokols D, Morgan G, Gehlert S (2012) A four-phase model of transdisciplinary team-based research: goals, team processes, and strategies. Transl Behav Med 2(4):415–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-012-0167-y

Hanneman RA, Riddle M (2005a) Introduction to social network methods: table of contents. Riverside, CA. Retrieved from http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/

Hanneman R, Riddle M (2005b) Introduction to social network methods. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Hanneman/publication/235737492_Introduction_to_social_network_methods/links/0deec52261e1577e6c000000.pdf

Henry AD (2009). Society for human ecology the challenge of learning for sustainability: a prolegomenon to. source: human ecology review (Vol. 16). Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy2.library.colostate.edu/stable/pdf/24707537.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae9ffb98fef69c055ab05ead486b9ca7e

Klein C, DiazGranados D, Salas E, Le H, Burke CS, Lyons R, Goodwin GF (2009) Does team building work? Small Group Res 40(2):181–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408328821

Knowlton JL, Halvorsen KE, Handler RM, O’Rourke M (2014) Teaching interdisciplinary sustainability science teamwork skills to graduate students using in-person and web-based interactions. Sustainability (Switzerland) 6(12):9428–9440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6129428

Kotler S, Wheal J (2008) Stealing fire: how silicon valley, the navy seals, and maverick scientists are revolutionising the way we live and work. Visual Comput (vol. 24). Retrieved from https://qyybjydyd01.storage.googleapis.com/MDA2MjQyOTY1NQ==01.pdf

Lee S, Bozeman B (2005) The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Soc Stud Sci 35(5):673–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705052359

Matthews NE, Cizauskas CA, Layton DS, Stamford L, Shapira P (2019) Collaborating constructively for sustainable biotechnology. Sci Rep 9(1):19033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54331-7

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patton MQ (2011) Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford Press

Perry-Smith JE (2006) Social yet creative: the role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Acad Manag J 49(1):85–101. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.20785503

Phelps C, Heidl R, Wadhwa A, Paris H (2012) Agenda knowledge, networks, and knowledge networks: a review and research. J Manag 38(4):1115–1166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311432640

Qualtrics Labs I (2005). Qualtrics Labs, Inc. Provo, Utah, USA

R Studio Team (2020) RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, http://www.rstudio.com/

Read EK, O’Rourke M, Hong GS, Hanson PC, Winslow LA, Crowley S, Weathers KC (2016) Building the team for team science. Ecosphere 7(3):e01291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1291

Ryan MM, Yeung RS, Bass M, Kapil M, Slater S, Creedon K (2012) Developing research capacity among graduate students in an interdisciplinary environment. High Educ Res Dev 31(4):557–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.653956

Sarraj H, Hellmich M, Chao C, Aronson J, Cestone C, Wooten K, Allan, B (2017) Training future team scientists: reflections from translational course. In: Team science training for graduate students and postdocs. Clearwater, FL. Retrieved from www.scienceofteamscience.org

Sawyer RK (2003) Emergence in creativity and development. In: Sawyer RK, John-Steiner V, Moran S., Sternberg RJ, Nakamura J et al. (eds.) Creativity and development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, pp. 12–60

Chapter Google Scholar

Senge PM (1991) The fifth discipline, the art and practice of the learning organization. Perform Instruct 30(5):37–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4170300510

Simonin BL (1999) Ambiguity and the process of knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Strateg Manag J 20(7):595–623. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199907)20:7<595::AID-SMJ47>3.0.CO;2-5

Spence JP, Buddenbaum JL, Bice PJ, Welch JL, Carroll AE (2018) Independent investigator incubator (I3): a comprehensive mentorship program to jumpstart productive research careers for junior faculty. BMC Med Educ 18(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1290-3

Stokols D, Misra S, Moser RP, Hall KL, Taylor BK (2008). The ecology of team science. Understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. Am J Prevent Med https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003

Woolley AW, Chabris CF, Pentland A, Hashmi N, Malone TW (2010) Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 330(6004):686–688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193147

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wooten KC, Calhoun WJ, Bhavnani S, Rose RM, Ameredes B, Brasier AR (2015) Evolution of multidisciplinary translational teams (MTTs): insights for accelerating translational innovations. Clin Transl Sci 8(5):542–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12266

Wooten KC, Rose RM, Ostir GV, Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, Brasier AR (2014) Assessing and evaluating multidisciplinary translational teams: a mixed methods approach. Eval Health Profession 37(1):33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713504433

Wu L, Wang D, Evans JA (2019) Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0941-9

Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B (2007) The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science 316(5827):1036–1039. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136099

Yin RK (2017) Case study research and applications: design and methods (6th edn.). Sage Publications

Zhang HH, Ding C, Schutte NS, Li R (2020) How team emotional intelligence connects to task performance: a network approach. Small Group Res 51(4):492–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496419889660

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zhang J, Scardamalia M, Reeve R, Messina R (2009) Designs for collective cognitive responsibility in knowledge-building communities. J Learn Sci 18(1):7–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400802581676

Download references

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to Elizabeth Scodfidio for helping with data, images and more!. The research reported in this publication was supported by Colorado State University’s Office of the Vice President for Research Catalyst for Innovative Partnerships Programme. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of the Vice President for Research. Supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. Funding and support were provided by grants from the National Science Foundation’s Ecology of Infectious Diseases Programme (NSF EF-0723676 and NSF EF-1413925).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Divergent Science LLC, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Hannah B. Love

Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Jennifer E. Cross, Bailey Fosdick, Kevin R. Crooks & Susan VandeWoude

University of New Mexico and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Ellen R. Fisher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HBL conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, analysed the data, conducted the investigation, worked as the project manager, managed the software, validated the data, created visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; BF conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, analysed the data, managed the software, validated the data, supervised all aspects of the research, created visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; JC conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, acquired funding, supervised data collection, and reviewed and edited the paper; KC and SV wrote the paper, secured funding, reviewed and edited the paper; and ERF conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, supervised all aspects of the research, acquired funding, created the visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hannah B. Love .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

HBL, BF, JC, and ERF declare no competing interests. KC and SV are members of the exemplary team

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, supplementary data, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Love, H.B., Cross, J.E., Fosdick, B. et al. Interpersonal relationships drive successful team science: an exemplary case-based study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00789-8

Download citation

Received : 02 January 2021

Accepted : 14 April 2021

Published : 06 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00789-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Theory, Research and Practice

- Open access

- Published: 16 October 2012

The exemplar methodology: An approach to studying the leading edge of development

- Kendall Cotton Bronk 1

Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 5 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

15 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

The exemplar methodology is a useful, but to date underutilized, approach to studying developmental phenomena. It features a unique sample selection approach whereby individuals, entities, or programs that exemplify the construct of interest in a highly developed manner form the study sample. Studying a sample of highly developed individuals yields an important view of the leading edge of development that cannot be gleaned using other methodologies. A picture of the full range of development requires not only an understanding of typical and deficient growth, as provided by existing methodologies, but also of complete or nearly complete development, as provided by the exemplar methodology. Accordingly, the exemplar methodology represents a critical tool for developmental psychologists. In spite of this, because it has rarely been written about, the exemplar methodology has only been used to study a relatively narrow range of developmental constructs. Therefore, the present article defines the exemplar methodology, addresses key conceptual issues, and briefly outlines steps to utilizing the approach.

A wide range of methods exists for studying developmental constructs, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses, but historically no methodology has existed that could yield a picture of the leading edge of development, predict the next steps in development for typical individuals, or feature instances of complete- or nearly complete- development of a particular characteristic, and without this view, a complete understanding of construct development is impossible (Damon & Colby [ in press ]). The ability to view the upper ends of development in practice represents the unique contribution of the exemplar methodology.

The exemplar methodology is a sample selection technique that involves the intentional selection of individuals, groups, or entities that exemplify the construct of interest in a highly developed manner. This definition is derived from the empirical studies in developmental psychology that have employed this approach. In using the exemplar methodology, researchers deliberately select a sample of individuals or entities that exhibit a particular characteristic in a highly developed manner. The exemplar methodology features participants who are rare, not from the perspective of the characteristics they exhibit, but in the intensity with which they demonstrate those particular characteristics. For example, most people demonstrate care and compassion at times and with some level of sincerity, but care exemplars exhibit this characteristic more consistently and more intensely then more typical individuals. While exemplars differ from more typical individuals in terms of the way they exhibit a particular characteristic, they tend to be similar to more typical individuals in most other ways (Colby & [ Damon 1992 ]). For instance, a creative genius could be considered an exemplar, but just because this individual boasts particularly creative ideas does not mean that he or she is necessarily kinder, more sociable, or more athletic than other individuals. Exemplars serve as highly developed examples of the construct of interest, but in other ways their development may be typical or even deficient.

Studying individuals who exemplify different elements of development in highly developed ways is crucial; only by doing so are we able to witness advanced development in the real world. Exemplars trace the steps of where more typical individuals are likely to go, if growth continues (Colby & [ Damon 1992 ]). We call the individuals who exhibit a particular characteristic in an intense manner exemplars , and we call the methodology used to study these individuals the exemplar methodology .

History of the exemplar methodology

Although developmental psychologists interested in positive psychology have only relatively recently begun using the exemplar methodology (e.g. Colby & [ Damon 1992 ]), the methodology has been in existence since Aristotle. In Nicomachean Ethics Aristotle wrote, “We approach the subject of practical wisdom by studying the persons to whom we attribute it” ([ Aristotle 1962 ], 6.5 1140a25). In other words, to understand how a complex construct functions and develops, it is useful to examine that construct in the lives of individuals who exhibit it in a highly developed manner. Along these same lines, [ Maslow (1971 ]) was one of the earliest scholars to actually employ the exemplar methodology, though he never called it that. Education, he claimed, “is learning to grow and learning what to grow toward” (p. 169). If we want to learn about ultimate human potential, he argued, we should study highly functional and enlightened individuals.

Use of the exemplar methodology has increased in the past twenty years in conjunction with the growth of the positive psychology movement (Seligman & [ Csikszentmihalyi 2000 ]; Sheldon & [ King 2001 ]; [ Damon 2004 ]). Historically, psychologists were primarily concerned with understanding what could go wrong with regards to human behavior, emotions, social interactions, and cognition. The focus of this one-sided, however important, field of human functioning has brought about a highly developed understanding of people’s mental vulnerabilities, deficiencies, and illnesses. However, this focus has essentially ignored issues of human thriving and flourishing (Benson et al. [ 2006 ]; Bundick et al. [ 2010 ]; Lerner et al. [ 2003 ]; [ Seligman 2011 ]). Leaders in the field of psychology, recognizing the need for additional knowledge of, research into, and practical methods to sustain people’s inner strengths and overall well-being, helped establish the new paradigm of positive psychology.

As the number of studies based on this new paradigm has increased, so too has use of the exemplar methodology (e.g. Matsuba et al. [ in press ]). The exemplar methodology lends itself to the study of optimal human development. Using a methodology that is focused on the upper ends of development is appropriate in an area concerned with ideal states of being.

Conceptual issues

The exemplar methodology represents a complex approach to studying human development, and as such, there are many issues to consider when applying it. First, the decision of whether to include a comparison sample can be contentious. Many effective exemplar studies have included matched samples (e.g. [ Bronk 2008 ]; Hart & [ Fegley 1995 ]; Matsuba & [ Walker 2004 ]; Matsuba & [ Walker 2005 ]; [ Reimer 2003 ]; Walker & [ Frimer 2007 ]), but other valuable studies have not (e.g. [ Bronk 2011 ]; [ Bronk 2012 ]; Colby & [ Damon 1992 ]; [ Mastain 2008 ]). Including a comparison sample allows the researcher to draw conclusions regarding ways in which the exemplar sample is distinct from more typical individuals, and this would seem to be an important benefit of the exemplar methodology. However, it can also be argued that what we glean by studying exemplars alone is sufficient to describe what these individuals are like with regards to their development in a particular area. If a characteristic or experience is evident among this sample, then it is evident. A comparison with a matched sample is not needed. Ultimately, the decision to use a comparison sample should be made in light on the claims that the researcher hopes to make. Without a comparison sample, researchers can claim that exemplary individuals possess certain characteristics and share particular experiences, but they cannot claim that these characteristics and experiences differentiate the exemplary individuals from more typical people.

Another complex issue with regards to the exemplar methodology has to do with the nature of exemplarity itself. How can researchers ascertain what constitutes exemplarity in any particular domain? Whose conception of exemplarity is most valid? Researchers conducting studies of moral exemplars regularly wrestle with what constitutes morality. Some studies of moral exemplars rely on lay conceptions (e.g. Walker & [ Pitts 1998 ]) and others on expert conceptions (e.g. Colby & [ Damon 1992 ]). Still others rely on behavioral manifestations of different aspects of morality (e.g. Walker & [ Frimer 2007 ]). The expert approach has the potential advantage of including a thoughtful and unbiased perspective on morality, but in some cases it ends up yielding a fairly narrow and often unrepresentative view of the construct (Matsuba & [ Walker 2005 ]). The lay perspective is likely to be broader and more representative, but it may also runs the risk of being diffuse and biased. The outcome approach can include engagement in particular acts (e.g. harboring Jews during the holocaust as a sign of altruism exemplarity; Oliner & [ Oliner 1988 ]) or winning special awards (e.g. winning national awards for care or bravery as signs of care or bravery exemplarity; Walker & [ Frimer 2007 ]). The outcome approach is likely to yield a more homogeneous sample, at least with regards to certain experiences around the construct of interest, but because it is narrower it may miss individuals who would meet the criteria, but who did not have the opportunity to engage in the exemplar qualifying acts. Ultimately, the best approach depends on the aims of the study, but regardless of the approach selected, it is important to consider the ways in which the chosen definition of exemplarity is likely to influence the study’s findings.

Finally, it is important to consider how exemplar study findings can be generalized. Findings reveal the leading edge of development, but what does this tell us about more typical development of the construct? Correlational exemplar studies predict the experiences and characteristics that are likely to accompany the construct of interest, but we cannot claim that these experiences and characteristics cause exemplarity. Furthermore, it is important to bear in mind that while the exemplars are highly developed in one particular area, they are not necessarily highly developed in others, so it is important to bracket findings to the construct of interest.

The discussion that follows outlines the steps involved in conducting an exemplar study. These conceptual issues, including the use of comparison studies, discernment of exemplarity, and generalization of findings, undergird and guide this discussion.

Steps in conducting exemplar research

To date, the exemplar methodology has largely been confined to studies or moral and ethical development. Researchers in this area, familiar with Colby & Damon’s ([ 1992 ]) influential study of moral exemplars, have applied the methodology in related studies of ethical development (e.g. care exemplars, Hart & [ Fegley 1995 ]; spiritual exemplars, [ King 2010 ]; environmental exemplars, [ Pratt 2011 ]; moral exemplars, Walker & [ Frimer 2007 ]). While the methodology is certainly useful in this area, it should be applied more broadly to studies of positive psychology. Use has been limited to a narrow sliver of the positive psychology space in large part because the methodology has rarely been written about. To encourage broader use of this methodology, guidelines for its implementation are needed. Therefore, following is a discussion of the steps involved in carrying out an effective exemplar study.

Successful use of the exemplar methodology requires special attention to sample selection. Individuals who exhibit signs of full or nearly full development in the area of interest are included in the study. To determine which individuals demonstrate complete or nearly complete development, most studies rely on carefully designed nomination criteria and thoughtfully selected nominators who use the nomination criteria to select appropriate exemplar participants.

Nomination criteria

One of the first steps to utilizing the exemplar methodology is to devise the criteria by which the exemplars are to be identified. Nomination criteria represent the standards used to qualify exemplars.

Researchers vary widely in terms of the rigor they apply to devising nomination criteria. One of the earliest and most influential exemplar studies employed a very thorough method in this regard. Colby & [ Damon (1992 ]) used an iterative process that relied on moral experts, including moral philosophers, theologians, ethicists, historians, and social scientists from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, to develop their nomination criteria for moral exemplars. Interviews were conducted with the moral experts, in which they were presented with a preliminary list of criteria that the researchers believed offered a basis for identifying moral exemplars. Experts were encouraged to edit the list as they saw fit. Eventually, the following set of five criteria emerged:

Moral exemplars exhibit a sustained commitment to moral ideals or principles that include a generalized respect for humanity, or a sustained evidence of moral virtue,

a disposition to act in accord with their moral ideals or principles implying also a consistency between their actions and intentions and between the means and ends of their actions,

a willingness to risk their self-interest for the sake of their moral values,

a tendency to be inspiring to others and to move them to moral action, and

a sense of realistic humility about their own importance relative to the world at large, implying a relative lack of concern for their own egos (p. 29).

Because the study sought to understand how morality developed and because people’s ideas of what constitutes morality vary, it was important to have in place a systematic process for devising nomination criteria.

The expert approach to devising nomination criteria has been used in many exemplar studies. For example, a study of care exemplars by Hart & [ Fegley (1995 ]) asked community leader experts, including church and youth group leaders, to come together to develop criteria for care exemplars (Hart & [ Fegley 1995 ]). Their collaboration yielded the following criteria:

Youth care exemplars are involved in community, church, or youth group activities that benefit others,

have unusual and admirable family responsibilities,

exhibit a willingness to help those in need,

volunteer their time to help others,

display emotional and social maturity,

lead others,

practice open-mindedness about others,

demonstrate a willingness to look beyond the difficulties of living in an urban locale to a better future,

show compassion,

display a sense of humility about his/her aid to others, and/or

demonstrate a commitment to friends and family (p. 1350).