- Arts & Humanities

Unhealthy vs. Healthy Food

30 Dec 2022

- Arts & Humanities

Format: APA

Academic level: College

Paper type: Essay (Any Type)

Downloads: 0

Unhealthy food is much more affordable and available than healthy food

Did you know that over 35 percent of adults and 20 percent of the children between 2 and 19 years old in the United States are either obese or overweight? The main reason for this alarming rate of obesity in contemporary society is the increased presence of junk foods. From a definitional perspective, junk foods refer to food products without substantial nutritional value to the users. Junk foods are packaged or pre-prepared. For example, the pre-prepared junk foods incorporate the cooked products before the consumers make substantial order; thus, burgers, pizzas, French fries, and tacos among others. Alternatively, packaged junk foods emanate from the companies in diverse tins, wrappers, or bottles such as the carbonated drinks, chocolate, candy, and pastries. In the fast-paced society, junk foods (unhealthy foods) have become popular because they are highly convenient, as well as cheaper in comparison to the healthy foods at the disposal of the consumers (Cecchini, Sassi, Lauer, Lee, Guajardo-Barron, & Chisholm, 2010). Notably, healthy food choices should be more affordable and available for all to help tackle the growing cases of obesity in modern society.

Because of fast food, as well as corporate farming implications, the food market is a mess. It is ideal for society to go back to the local food, as well as organics to promote healthy eating practices and activities in modern society. According to reality, junk food is a cheaper and convenient option for most Americans. Junk foods are highly available. With the presence of the fast-food chains at every corner in a town, more and more people in the fast-paced society focus on optimizing the convenient and cheaper junk foods because of their busy schedules and increased commitment to their jobs or work expectations. Other than just being widely available, junk foods or unhealthy foods taste good (Kern, Auchincloss, Stehr, Diez Roux, Moore, Kanter, & Robinson, 2017). Consumers do not spend time in preparing for the food as they can acquire them from the chains. Amid all these, there is a growing perception among the consumers that healthy foods are more expensive compared to junk foods. Researchers believe that eating healthy foods is highly expensive. It is about three times as expensive as consuming junk foods at fast food chains (Tam, Yassa, Parker, O'Connor, & Allman-Farinelli, 2017). In making it worse, the price gap between healthy and unhealthy foods is widening. The increased price difference between healthy and unhealthy foods is the main contributor to the growing cases of food insecurity, as well as increasing aspects of health inequalities, thus, the growing deterioration in the health outcomes of the population. One of the reasons for increasing food poverty is the high cost of healthy options. The cost of healthy food is a reflection of the sociological problem rather than just an individual’s choice.

Delegate your assignment to our experts and they will do the rest.

Why is this a problem? Unhealthy foods are the main contributors to obesity in the context of the fast-paced society. Other than causing obesity, junk foods are elements of poor nutrition associated with high blood pressure. Junk foods also lead to high cholesterol, as well as heart disease and stroke among consumers. Food is an important component of the physical and mental health of the consumer; thus, the need to avoid consuming unhealthy foods or junk foods. Unhealthy foods also contribute to tooth decay, different types of cancer, and diabetes. These aspects contribute to the negative implications of the health outcomes within society. More and more people continue to spend more on healthcare costs rather than securing healthy foods, as well as ideal eating habits for their health. The society has more obese and overweight people because of the increased consumption of the convenient, widely available, tastier, and cheaper unhealthy foods compared to the consumption of the healthy foods, which consumers deem to the expensive.

How is it possible to address the issue? The answer is quite simple. The government should adopt and implement appropriate measures to make healthy food choices more affordable and available for all. In this aspect, consumers will have the chance to optimize education on nutrition while understanding the perception and need for healthy eating habits to consume the available healthy foods rather than go for the unhealthy foods or junk foods.

One of the ways of addressing this is to increase awareness through improved communication channels from the authoritative support agencies to increase the knowledge among the consumers on the consumption of healthy foods. In this aspect, education as an intervention approach is ideal in the improvement of the negative perceptions among the consumers on the affordability of healthy foods (Harrison, Lee, Findlay, Nicholls, Leonard, & Martin, 2010). There is also the improvement of access to the farm products as a win-win strategy for the consumers and producers.

The authorities should also achieve this by moving the markets to the consumer through eradication of the geographical barriers (Niebylski, Redburn, Duhaney, & Campbell, 2015). The approach will create room for the establishment of the distribution channels such as food hubs, which are accessible to more and more consumers. Over 20 million Americans tend to live in low-income towns, as well as rural neighborhoods, which are far away from the supermarkets. In such aspects, it is appropriate to consider taking the market to the people/consumers. Conclusively, in curbing the growing cases of obesity and other health issues emanating from increased consumption of tastier, convenient, cheaper, and widely available unhealthy foods, healthy food choices should be more affordable and available for all.

Cecchini, M., Sassi, F., Lauer, J. A., Lee, Y. Y., Guajardo-Barron, V., & Chisholm, D. (2010). Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. The Lancet , 376 (9754), 1775-1784.

Harrison, M., Lee, A., Findlay, M., Nicholls, R., Leonard, D., & Martin, C. (2010). The increasing cost of healthy food. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health , 34 (2), 179-186.

Kern, D., Auchincloss, A., Stehr, M., Diez Roux, A., Moore, L., Kanter, G., & Robinson, L. (2017). Neighborhood prices of healthier and unhealthier foods and associations with diet quality: Evidence from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. International journal of environmental research and public health , 14 (11), 1394.

Niebylski, M. L., Redburn, K. A., Duhaney, T., & Campbell, N. R. (2015). Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition , 31 (6), 787-795.

Tam, R., Yassa, B., Parker, H., O'Connor, H., & Allman-Farinelli, M. (2017). University students' on-campus food purchasing behaviors, preferences, and opinions on food availability. Nutrition , 37 , 7-13.

- The Rate of Return on Your Investment

- The Relationship Between Ethics and the Law

Select style:

StudyBounty. (2023, September 16). Unhealthy vs. Healthy Food . https://studybounty.com/unhealthy-vs-healthy-food-essay

Hire an expert to write you a 100% unique paper aligned to your needs.

Related essays

We post free essay examples for college on a regular basis. Stay in the know!

The Downfalls of Oedipus and Othello

Words: 1402

Why I Want To Become a Physician

The perception of death in the play "everyman".

Words: 1464

How to Reverse Chronic Pain in 5 Simple Steps

Words: 1075

“Boyz n the Hood” director and Auteur Theory paper

Free college and university education in the united kingdom, running out of time .

Entrust your assignment to proficient writers and receive TOP-quality paper before the deadline is over.

- All Medicines

- Order Online

Covid Essentials

- Personal & Home Essentials

- Business Essentials

- Mask, Gloves & Protective Equipment

- Travel Essentials

- Breathe Easy

- Surgical Accessories

- Measurements

- Orthopaedics

Diabetes Support

- Glucometers

- Sugar Substitutes

- Diabetes Management Supplements

- Diabetes Care Ayurveda

- Lancets & Test Strips

- Eye Glasses

- Reading Glasses

- Contact Lenses (EW)

- Weight Management

- Sports Supplements

- Smoking Cessation Support

- Vitamins And Supplements

- Family Nutrition

- Health Food And Drinks

- Ayurvedic Supplements

Health Conditions

- Women's Care

- Bone And Joint Pain

- Weight Care (EW)

- Stomach Care

- Mental Care

- De-Addiction

- Diabetic Care

- Cardiac Care

- Cold And Fever

- Immunity Care

Mom & Baby

- Feminine Hygiene

- Maternity Care

- Baby Bath Time

- Maternity Accessories

Personal Care

- Home & Health

- Senior Care

- Face Personal Care

- Hands & Feet

- Bath & Shower

- Personal Care Tools & Accessories

- Bathing Accessories

Sexual Wellness

- Massagers/Vibrators

- Sexual Health Supplements

- Sprays/Gels

- Respiratory Supplies

- Surgical Consumables

- Iv Infusion

- Surgical Instrument

- Urinary Care

- Wound Treatment

- Farm Animals

- Vitamin Store

- Derma Cosmetics

- Diabetes Center

- Hair Styling

- Hair Tools & Accessories

- Scalp Treatments

- Shop By Hair Type

Men's Grooming

- Face Makeup

- Make-Up Tools & Brushes

- Toys & Games

- Aromatherapy

- Face Skin Care

- Moisturizers

- Toners & Serums

Tools & Appliances

- Face/Skin Tools

- Hair Styling Tools

- Massage Tools

- Health Library

- PatientsAlike

- All About Cancers

- Corona Awareness

Junk Food Vs Healthy Food: Advantages, Disadvantages And Healthier Food Choices

Quick reads, content details.

Many of us love greasy and sugary foods and for those used to eating junk food - cheese, deep-fried, sweetness loaded delicacies are an obsession of sorts.

Thanks to globalization, various junk foods belonging to global cuisine have crept into your daily diet plan in the last couple of decades leading to an increase in the rate of childhood obesity and the risk of developing chronic diseases like cancer , diabetes , cardiovascular diseases etc.

If you ask, which one is better from the taste point of view, the battle between healthy food and junk food never ends. Mindful eaters might argue that nutritional food items are tastier too but when it comes to choosing between the two, junk food always win the race.

But why? Well, agree or disagree cravings are irresistible and unhealthy eating habits are actually a norm. We can kill our mid-day hunger pangs with an apple or a fistful of nuts, but most of us end nibbling upon a pile of French fries or pizza and even guzzle down fizzy drinks. It in fact, has become a mammoth task for these days parents in convincing their children to pick fresh veggies, fruits, nuts, salads, soups over these unhealthy and calorie loaded recipes.

What Is Junk Food?

Junk food is the best example of an unbalanced diet categorised by a huge proportion of simple carbs, refined sugar, salt, saturated fat and with very low nutritional value. These foods are processed to a great extent where they almost lose all of their vital nutrients, fibre and water content. Junk food may be quite convenient, readily available on the go, cheap whereas healthy food is best for maintaining weight, getting an adequate amount of essential nutrients and for keeping you in good state of health.

Also Read: Craving For Junk Food? Try These Healthy Swaps Loaded With Nutrition – Infographic

Junk Vs Healthy Food

Healthy food refers to a whole lot of fresh and natural products such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins and good fats that deliver your body with essential nutrients for carrying out several bodily processes, combat sickness and keep diseases at bay. Some of the healthy foods include apples, greens, carrots, oatmeal, whole grain, beans and legumes, fish, eggs, avocado, milk and milk products and olive oil to mention a few.

While, junk food is a highly processed food that is made up of ‘empty’ calories foods loaded with full of saturated fat, sugar and devoid of nutrients which neither helps the body to nurture, focus and perform vital functions all through the day. It includes packaged food products like chips, cookies , cakes, pastry, candy soda, ice-cream and a list of fast food items on the restaurant menus like pizza, pasta, burgers and French fries.

Why Is Healthy Food Better Than Junk Food?

When you consume a diet that is packed with natural fresh produce, it facilitates to lower the risk of several chronic disorders like cancer, obesity, cardiovascular problems, diabetes and many more. Furthermore, healthy foods are mostly low on calories and contain huge amounts of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and dietary fibre that are well-known for promoting total well-being.

Advantages Of Healthy Foods

Healthy foods like fruits and veggies or whole grain cereals are a source of good dietary fibre. An adequate amount of fibre in the diet helps with delaying gastric emptying time, keep you satiated and prevent you from overeating. Fibre-rich foods also benefit to maintain the digestive system healthy and function effectively thereby lowering cholesterol and blood glucose level.

Also Read: 5 Healthy Food Choices To Start Your Day

Healthy foods are basically unprocessed, low on calories and do not miss out on vital nutrients. Consuming a wholesome meal comprising of whole-grain cereal, legume, low-fat dairy –paneer or curd , veggies and fruit meets your daily demands of nutrition.

Natural food produce is low on saturated fat, trans fat and calories which help you to manage weight.

Incorporating a rich array of healthful foods imbued with dense nutrient profile safeguard your heart, maintain lipid profile, control blood pressure and blood sugar levels, avert the risk of inflammation, boost metabolism, promote smooth digestion process, bolster immunity and keep diseases at bay .

Yes, healthy food not only provides you with needed essential nutrients but also delivers you with a spectrum of health incentives which hold a significant role in uplifting your overall physical, mental and emotional well-being.

The perks of healthy food and cons of junk food are quite clear, making mindful choices with your meals and snacks will let you to focus and concentrate well throughout the day. As the body’s needs are met by nutritionally loaded food choices it will keep you satiated and content. Moreover, this averts untimely snacking or binge eating.

When kids prefer healthy food it ensures them to be more productive and efficient with time and memorize things they have learned, rather than being sleepy and reading the same things over and over again.

High fibre foods release energy slowly, whereas sugar laden foods offer you a sudden burst of energy. You may be tempted to reach for that pack of chocolates around afternoons but choose an apple with peanut butter or banana or carrot sticks with yoghurt for conferring you with sustained energy needed to accomplish your day task.

Also Read: 5 Successful Healthy Eating Habits To Practice - Infographic

Junk food can result in long-term damage, going for unhealthy food stuffs like French fries, pizza, pastries and candy can increase your risk of developing depression, obesity, heart disease and cancer.

Difference Between Healthy Food vs Junk Food

Junk food tends to be high on fat, unrefined carbohydrates and added sugars, all of which up their energy density or caloric values. Consuming plenty of energy-dense foods increases your risk of obesity and other metabolic disorders. On the other hand, healthy foods are low in energy and fat content and high on nutrients, thus a diet low in calories help you lose weight and maintain good health status.

One of the key variants between junk and healthy food is the amount and type of saturated and unsaturated fats they contain. Unsaturated fatty oils are healthier options like olive oil, sunflower oil , sesame oil etc., these oils contain the right proportion of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids which are healthier for the heart and also maintain the lipid profile. While junk foods are loaded with a high amount of saturated fats and trans fat like butter, lard, palm oil and dalda are unhealthy and harm health.

Junk or fast foods are those items with empty calories, which means they only offer you a high amount of calories without providing you with needed vital nutrients. Studies have also disclosed that people who consume fast foods on a regular basis have lower micronutrient intake and may have a nutritional deficiency. Choosing wholesome foods will assure you with an increase in the nutrients per calorie making it feasible to meet the recommended dose of macro and micronutrients.

Well, fast food can be a cheaper option than adopting a healthy eating habit, however, you can still plan a nutritious meal plan by including low-cost locally available fresh natural produce that will save your money compared to convenience foods. Furthermore, the merits of eating healthy food go way beyond in maintaining your overall health, where the cost factor is often neglected when health is your top priority.

Addictive Qualities

Junk food is considered to have addictive qualities as they are revolved around sugar and fat. Sugar is known to kindle the brain reward pathways, sugar, when combined with fat, becomes hard to resist. Studies observe that the blend of sugar and fat is mostly linked with addictive symptoms like withdrawal or loss of self-control over food. Well, regular or even intermittent intake of junk foods has the potential to drive the habit formation in the brain which can increase your cravings leading to overconsumption of junk food and with time results in weight gain.

Simple Ways To Eat Less Junk Food

There are a number of ways one can gradually reduce the intake of junk food. First and foremost, never stock up in your homes which can easily take away the temptation.

Secondly, stay alert and be mindful of eating chips or other snacks directly from the pack, instead, portion a small quantity into a bowl and relish. Share junk food with friends or eat with other people who will help you to slow down and enjoy good conversation and your nachos.

Staying healthy while eating junk food is possible when you have it moderation, the key mantra is don’t overdo it.

Junk food tastes delicious but not satiating, it’s packed with empty calories. Hence if you are hungry steer clear of the readily available junk foods and wait uncomplainingly for something wholesome.

If you want to eat junk food, then ensure to stay active and do include some physical activity into your routine. A brisk walk post-dinner or quick cardio can help you to stay active and keep things in balance. On the other hand, if you don’t want to move your body, then reconsider the junk food you wish to eat.

Consider junk food the exception, rather than the norm. Focus on eating a healthy diet all through the week and have a cheat day during the weekend, where you can treat yourself with favourite candy or fries, and you don’t have to feel guilty about it.

Likewise, swap your junk food with healthier choices which includes

Fruits: apples, bananas , oranges, and berries

Vegetables: Leafy greens, sweet potato, carrots, broccoli, and cauliflower

Whole Grains: Cereals, oats, brown rice, quinoa , and wheat

Seeds and Nuts: Almonds, walnuts, flaxseeds and sunflower seeds

Legumes: Beans, peas, and lentils

Lean Protein Sources: Fish, eggs and poultry

Dairy: Curd, yogurt, cheese, and fermented dairy products like kefir

Healthy Fats: Olive oil, nut butter, avocados, and coconut

Healthy Beverages: Water, green tea, and herbal teas

Fitting Fast Food Into A Healthy Diet

A well-balanced meal plan comprises of about half fruits and vegetables, while other half consists of whole-grain cereals and legumes or lean meats. When you visit a fast-food restaurant lookout for the healthiest options, it can be a grilled or baked food instead of deep-fried stuff. Start with a soup or salad with low-fat dressing as they are low in calories and keep you filled, then get a smaller serving of your main course. Vegetarian choices are often healthier than meat-based starters, as long as they are not fried. Try to skip fattier toppings like mayo, sauces, cheese and creams.

Healthier Junk Food Options

Craving for unhealthy junk food stuff is real and powerful. Well, instead of struggling and fighting your cravings, just try to feed it with a healthier version. There are certain junk foods that are pretty good for you which include:

Popcorn baked or made at home with a drizzle of olive or vegetable oil is a source of good dietary fibre.

Ice-creams and Greek yoghurt are great options loaded with calcium and protein.

Look for dark chocolate bars that are 70% cocoa for your guilt-free indulgence for something sweet. Dark chocolates abound in antioxidants, protein and fibre.

Tortilla chips made from kale, greens are preferred choice versus traditional potato chips.

Sweet potato fries though has a high amount of carbs and calories, it is heaped with dietary fibre and a massive amount of vitamin A.

Snacking on one or two cubes of cheese will offer you a boost of calcium and protein. It is a good idea to top up the cheese with fruit or nuts for that bonus vitamins.

Oatmeal cookies is one of the best bet for a healthful snack packed with fibre, calcium and iron.

Conclusion :

Junk food are highly processed foods loaded with calories, sugar and fat, however, it is devoid of essential nutrients like fibre, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. It is believed to be a key factor in the obesity epidemic and a driving force in the development of chronic diseases. Moderation is the key mantra when it comes to food. The combination of fat and sugar make junk foods more addicting and easy to overdo. Relishing your favourite treat on occasional basis is a more realistic, healthful and sustainable approach for your health.

Disclaimer:

The content provided here is for informational purposes only. This blog is not intended to substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare provider for any questions or concerns you may have regarding a medical condition. Reliance does not endorse or recommend any specific tests, physicians, procedures, opinions, or other information mentioned on the blog.

- ← Previous

- Next →

Related Posts

Maharashtra Bans Junk Food, Soft Dr..

Vegetable khicdi, rajma-rice and idli - vada are set to be among the dishes that..

Junk Food Consumption Ups Allergy R..

Researchers have found that high consumption of junk food such as microwaved foo..

Craving For Junk Food? Try These He..

Let’s confess that we all love junk foods and for many of us eating deep f..

Healthy Eating Food Pyramid: A Guid..

Healthy eating is all about making smart food choices. A food pyramid serves as ..

5 Successful Healthy Eating Habits ..

Eating healthy is not really about strict restrictions, staying whimsically thin..

Drinking Soft Drinks Linked To Obes..

Researchers have found that sugar-sweetened acidic drinks, such as soft drinks, ..

Obesity: Causes, Symptoms And Treat..

Obesity is a chronic and severe lifestyle disorder in which excess fat accumulat..

Related Products

Latest Posts

Ayurveda For Stamina: Spectacular Natura..

Have you experienced a feeling of undue tiredness and weakness not just at the e..

Sprained Ankle: 7 Effective Exercises To..

Ankle sprains are most common injuries that can happen to anyone, irrespective o..

Marine Collagen: Unleash The Amazing Bea..

In the vast depths of the ocean, where life takes on extraordinary forms, there ..

Soursop/Graviola: Health Benefits And Cu..

Have you ever noticed a prickly green fruit called Graviola at an exotic fruit m..

- Free Essays

- Citation Generator

Junk Food vs. Healthy Food

You May Also Find These Documents Helpful

Warnings on unhealthy food.

Firstly, junk food can be the reason of a lot of illnesses, such as stomach ulcer, obesity, sugar diabetes, etc. For example, according to the article Health warnings on junk food “…hamburgers, chips, soybean oil, pizza give rise to obesity and it can be the reason of heart attacks and even cancer…” So, people should know what they eat.…

New Study Reveals Junk Food Good For You By Billy Bunting

There is controversy over whether or not people should stop eating junk food. In the article “New Study Reveals Junk Food Good for You,” Billy Bunting believe some types of sugary, fatty junk foods “are better for you than so-called healthy foods” (Bunting). Throughout the article, he accounts evidences to verify his argument that eating large doses of junk food is good and a key to a long and healthy life. In “New Study Reveals Junk Food Good for You,” Bunting accounts studies, action points, and seven “tips to enjoy eating junk food so that its benefits can be fully realized” (Bunting).…

Eating Healthily and Advantages Disadvantages of Foods

Today, every people and every country were all developing and moving forward, by then shall we keep in mind, what make us live until today and keeping us healthy.“Eating Healthily With A Busy Lifestyle”, is the topic that I chose. By reading the topic, the main point that I chose, straight away in people’s mind they will think of delicious food, delicacy that bring up the appetite, but do they have the time to eat what they want, to enjoy such appetizing meals? Does it suit our healthy life since nowadays we usually eat what we, just like the often phrase we usually heard, saw in the advertisements, ‘eat all you can’ or ‘eat while you can’. Some people neglect the healthy food thing, because they thought that healthy food is boring, not delicious and many more.…

Junk Food Should Be Banned In Schools Essay

that are eaten by many people. Junk foods are unhealthy because it doesn’t have much…

Taxing Junk Food

Usually, and as the medical reports say, junk food is unsafe. We can explain this in an easy way. Most of the restaurants that serve fast food do not serve healthy and safe food to people where as they serve junk food. “Unsafe food” means that the reference of the food is unknown. If we take meat as an example, because it is used in most fast food restaurants’ sandwiches, we do not know whether the health organizations in the government approved that this kind of meat which is being sold in the fast food restaurant is clean and healthy or is not appropriate to be eaten. People do not know the reality, but they have a big field of research they can do so they know more about junk food.…

Obesity In The United States

Many people are wondering why they are getting so sick, but they have not realized what causes the sickness. There is a great number of people including young children, adult and young adults, and the elders who are being affected by consuming junk food every day. Junk food is very dangerous to human’s health, and not many people are aware of that. Research shows that people living in the United State are more affected by eating junk food than many people in other countries. It is very crucial to know the side effects of junk food although junk food may taste very delicious. People need to be knowledgeable about what they eat every day. Therefore, knowing what junk food can cause to the human’s health is very important. There are mainly three…

Eating Healthy and Staying Active

Many Americans continuously eat junk food and see no problem with it. It is fast, cheap, and delicious so how could it be bad for you. That couldn’t be further from the truth. The fact is most fast food companies make their food cheap and long lasting. How they accomplish this is by adding many doses of preservatives to their food. This can have bad effects on your health. Continuous consumption of these foods could cause strokes, heart attacks, and diabetes. In order to avoid these health problems it is suggested that you even out your diet to consist of a varity of different food groups. It is ok to have junk food every once in a while but in order to maintain your health you must also eat some fruits and vegetables. By evening out your diet your body will be able to pull out all the nutrients it needs to stay healthy.…

Persuasive Essay on Eating Healthy

When you keep your body strong, well, and clean, you are being healthy. In order to be healthy, the person will have to eat the right kind of food, exercise daily, take a shower, keep him/herself clean, and stay well. People who are healthy are likely to have the background of being and staying drug free. Junk food is not one of the things people eat to be healthy. Eating junk food affects your body and can make you sick.…

Determinants of Health

Junk food contains to much sugar or to much salt which can negatively affect our health in short or long term…

Taxing Junk Food Essay

Junk food can be known as different types of food, candy, and even sugary drinks. Some foods that can be considered ‘junk food’ are candies, chips, gum, and salted snacks are just a few examples of ‘junk food’. Pizza, hamburgers and tacos could be considered healthy or junk food. Sweetened drinks can be considered ‘junk food’ because they have a lot of sugar. Some drinks that are under the ‘junk food’ category are sports drinks, sodas, frappes, and milkshakes. These are just some of the many unhealthy drinks.…

Junk food; a slow poison

Junk food may be affordable and delicious, yet it is deadly. Examples of junk food include burger, pizza, hot dog, tacos, fries, biscuits, cookies, and soft drinks. Today many people are addicted to junk food. They grab junk food without planning to or making many decisions. Even when time is available, people still prefer to consume junk food rather than prepare a normal wholesome meal, which is healthier. Junk food is very popular around the world today. Junk food popularity is due the busy nature of the society in which we live. Junk food is also popular because of its price, good taste, availability, and attractive sight. In as much as junk food is advantageous, over consumption of junk food can be devastating to the health. Junk food contains elements like sodium, fat, and sugar, which when accumulated in the body can lead to numerous diseases. Hence, junk food can kill slowly like a slow poison.…

Consuming Unhealhy Food Against Healthy Food

Unhealthy food is referring to junk food, which is a term applied to some foods that are perceived to have little or no nutritional value (Michael Jacobson). We can consider junk food as everything that is fast food. All these food are easy to make and easy to consume. Such as, pizza, hamburgers, hot dogs, chips, candy, gum, most sweet desserts, fried fast food and carbonated beverages. On the other hand, healthy food is considered to be whole food, non processed food and organic food such as, vegetables, fruits, whole wheat products, whole grain products, etc.…

Junk Food Advertising Should Be Banned in Australia

The purpose of this report was to present the definition of junk food and how junk food advertising has recently become an important issue around the world which began to concern governments, health authorities and families in every country, especially in Australia .Therefore, this report will address the problem of junk food very carefully and in order to accomplish that this report will involve an internet research and will include a number of evidences, which have been taken from books, magazines and newspapers. This report has described an important solution for this problem which is banning advertisements of junk food and then discussed three reasons behind this ban in a wide range. Also, it will include many facts and statistics about junk food advertising. These statistics show and improve one important fact which is junk food advertising should be banned. .…

Although junk food is not health and cheap, like Bittman said, but I think junk food also is very convenient and appetitive. Since the fast food by the people's "favorite", it certainly has its benefits; otherwise it cannot become a mainstream food culture. First, when people feel hungry, and they do not have time to cook, when you order at the general restaurant, teahouse, people usually need to wait for some time to have a food supply. Thus, it is not easy to satisfy people. Second, junk food usually uses the high cooking method which has the good color, flavor and taste, such as frying and high concentration of ingredients; those can stimulate people's appetite. People who is weekday rush and poor appetite is very suitable to eat junk food. Many parents are worried about their children eating problem that most children don’t like eating real food. Eating junk food is a way to solve this problem.…

The phrase "junk food" itself speaks of endangerment to health. Junk food typically contains high levels from sugar or fat with little protein and minerals. Foods usually considered junk foods are salted snack foods, gum, candy, fast food, and carbonated drinks. People should acknowledge that junk foods contained high amount of chemical substance, which will lead various disease. Yes, junk foods are tasty and the sweetness gives you pleasure, but health is way more important if you people don’t take the first step to avoid! As we said, prevention is better than cure.…

Related Topics

Healthy Food Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on healthy food.

Healthy food refers to food that contains the right amount of nutrients to keep our body fit. We need healthy food to keep ourselves fit.

Furthermore, healthy food is also very delicious as opposed to popular thinking. Nowadays, kids need to eat healthy food more than ever. We must encourage good eating habits so that our future generations will be healthy and fit.

Most importantly, the harmful effects of junk food and the positive impact of healthy food must be stressed upon. People should teach kids from an early age about the same.

Benefits of Healthy Food

Healthy food does not have merely one but numerous benefits. It helps us in various spheres of life. Healthy food does not only impact our physical health but mental health too.

When we intake healthy fruits and vegetables that are full of nutrients, we reduce the chances of diseases. For instance, green vegetables help us to maintain strength and vigor. In addition, certain healthy food items keep away long-term illnesses like diabetes and blood pressure.

Similarly, obesity is the biggest problems our country is facing now. People are falling prey to obesity faster than expected. However, this can still be controlled. Obese people usually indulge in a lot of junk food. The junk food contains sugar, salt fats and more which contribute to obesity. Healthy food can help you get rid of all this as it does not contain harmful things.

In addition, healthy food also helps you save money. It is much cheaper in comparison to junk food. Plus all that goes into the preparation of healthy food is also of low cost. Thus, you will be saving a great amount when you only consume healthy food.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Junk food vs Healthy Food

If we look at the scenario today, we see how the fast-food market is increasing at a rapid rate. With the onset of food delivery apps and more, people now like having junk food more. In addition, junk food is also tastier and easier to prepare.

However, just to satisfy our taste buds we are risking our health. You may feel more satisfied after having junk food but that is just the feeling of fullness and nothing else. Consumption of junk food leads to poor concentration. Moreover, you may also get digestive problems as junk food does not have fiber which helps indigestion.

Similarly, irregularity of blood sugar levels happens because of junk food. It is so because it contains fewer carbohydrates and protein . Also, junk food increases levels of cholesterol and triglyceride.

On the other hand, healthy food contains a plethora of nutrients. It not only keeps your body healthy but also your mind and soul. It increases our brain’s functionality. Plus, it enhances our immunity system . Intake of whole foods with minimum or no processing is the finest for one’s health.

In short, we must recognize that though junk food may seem more tempting and appealing, it comes with a great cost. A cost which is very hard to pay. Therefore, we all must have healthy foods and strive for a longer and healthier life.

FAQs on Healthy Food

Q.1 How does healthy food benefit us?

A.1 Healthy Benefit has a lot of benefits. It keeps us healthy and fit. Moreover, it keeps away diseases like diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol and many more. Healthy food also helps in fighting obesity and heart diseases.

Q.2 Why is junk food harmful?

A.2 Junk food is very harmful to our bodies. It contains high amounts of sugar, salt, fats, oils and more which makes us unhealthy. It also causes a lot of problems like obesity and high blood pressure. Therefore, we must not have junk food more and encourage healthy eating habits.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essays About Eating Healthy Foods: 7 Essay Examples And Topic Ideas

If you’re writing essays about eating healthy foods, here are 7 interesting essay examples and topic ideas.

Eating healthy is one of the best ways to maintain a healthy lifestyle. But we can all struggle to make it a part of our routine. It’s easier to make small changes to your eating habits instead for long-lasting results. A healthy diet is a plan for eating healthier options over the long term and not a strict diet to be followed only for the short.

Writing an essay about eating healthy foods is an exciting topic choice and an excellent way to help people start a healthy diet and change their lifestyles for the better. Tip: For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

1. The Definitive Guide to Healthy Eating in Real Life By Jillian Kubala

2. eating healthy foods by jaime padilla, 3. 5 benefits of eating healthy by maggie smith, 4. good food bad food by audrey rodriguez, 5. what are the benefits of eating healthy by cathleen crichton-stuart, 6. comparison between healthy food and junk food by jaime padilla, 7. nutrition, immunity, and covid-19 by ayela spiro and helena gibson-moore, essays about eating healthy foods topic ideas, 1. what is healthy food, 2. what is the importance of healthy food, 3. what does eating healthy mean, 4. why should we eat healthy foods, 5. what are the benefits of eating healthy foods, 6. why should we eat more vegetables, 7. can you still eat healthy foods even if you are on a budget.

“Depending on whom you ask, “healthy eating” may take many forms. It seems that everyone, including healthcare professionals, wellness influencers, coworkers, and family members, has an opinion on the healthiest way to eat. Plus, nutrition articles that you read online can be downright confusing with their contradictory — and often unfounded — suggestions and rules. This doesn’t make it easy if you simply want to eat in a healthy way that works for you.”

Author Jillian Kubala is a registered dietitian and holds a master’s degree in nutrition and an undergraduate degree in nutrition science. In her essay, she says that healthy eating doesn’t have to be complicated and explains how it can nourish your body while enjoying the foods you love. Check out these essays about health .

“Eating provides your body with the nourishment it needs to survive. A healthy diet supplies nutrients (such as protein, vitamins and minerals, fiber, and carbohydrates), which are important for your body’s growth, development, and maintenance. However, not all foods are equal when it comes to the nutrition they provide. Some foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are rich in vitamins and minerals; others, such as cookies and soda pop, provide few if any nutrients. Your diet can influence everything from your energy level and intellectual performance to your risk for certain diseases.”

Author Jaime Padilla talks about the importance of a healthy diet in your body’s growth, development, and maintenance. He also mentioned that having a poor diet can lead to some health problems. Check out these essays about food .

“Eating healthy is about balance and making sure that your body is getting the necessary nutrients it needs to function properly. Healthy eating habits require that people eat fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fats, proteins, and starches. Keep in mind that healthy eating requires that you’re mindful of what you eat and drink, but also how you prepare it. For best results, individuals should avoid fried or processed foods, as well as foods high in added sugars and salts.”

Author Maggie Smith believes there’s a fine line between healthy eating and dieting. In her essay, she mentioned five benefits of eating healthy foods – weight loss, heart health, strong bones and teeth, better mood and energy levels, and improved memory and brain health – and explained them in detail.

You might also be interested in our round-up of the best medical authors of all time .

“From old generation to the new generation young people are dying out quicker than their own parents due to obesity-related diseases every day. In the mid-1970s, there were no health issues relevant to obesity-related diseases but over time it began to be a problem when fast food industries started growing at a rapid pace. Energy is naturally created in the body when the nutrients are absorbed from the food that is consumed. When living a healthy lifestyle, these horrible health problems don’t appear, and the chances of prolonging life and enjoying life increase.”

In her essay, author Audrey Rodriguez says that having self-control is very important to achieving a healthy lifestyle, especially now that we’re exposed to all these unhealthy yet tempting foods that all these fast-food restaurants offer. She believes that back in the early 1970s, when fast-food companies had not yet existed and home-cooked meals were the only food people had to eat every day, trying to live a healthy life was never a problem.

“A healthful diet typically includes nutrient-dense foods from all major food groups, including lean proteins, whole grains, healthful fats, and fruits and vegetables of many colors. Healthful eating also means replacing foods that contain trans fats, added salt, and sugar with more nutritious options. Following a healthful diet has many health benefits, including building strong bones, protecting the heart, preventing disease, and boosting mood.”

In her essay, Author Cathleen Crichton-Stuart explains the top 10 benefits of eating healthy foods – all of which are medically reviewed by Adrienne Seitz, a registered and licensed dietitian nutritionist. She also gives her readers some quick tips for a healthful diet.

“In today’s generation, healthy and unhealthy food plays a big role in youths and adults. Many people don’t really understand the difference between healthy and unhealthy foods, many don’t actually know what the result of eating too many unhealthy foods can do to the body. There are big differences between eating healthy food, unhealthy food and what the result of excessively eating them can do to the body. In the ongoing battle of “healthy vs. unhealthy foods”, unhealthy foods have their own advantage.”

Author Jaime Padilla compares the difference between healthy food and junk food so that the readers would understand what the result of eating a lot of unhealthy foods can do to the body. He also said that homemade meals are healthier and cheaper than the unhealthy and pricey meals that you order in your local fast food restaurant, which would probably cost you twice as much.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked both an increased clinical and public interest in the role of nutrition and health, particularly in supporting immunity. During this time, when people may be highly vulnerable to misinformation, there have been a plethora of media stories against authoritative scientific opinion, suggesting that certain food components and supplements are capable of ‘boosting’ the immune system. It is important to provide evidence-based advice and to ensure that the use of non-evidence-based approaches to ‘boost’ immunity is not considered as an effective alternative to vaccination or other recognized measures.”

Authors Ayela Spiro, a nutrition science manager, and Helena Gibson-Moore, a nutrition scientist, enlighten their readers on the misinformation spreading in this pandemic about specific food components and supplements. They say that there’s no single food or supplement, or magic diet that can boost the immune system alone. However, eating healthy foods (along with the right dietary supplements), being physically active, and getting enough sleep can help boost your immunity.

If you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, you have to define what healthy food is. Food is considered healthy if it provides you with the essential nutrients to sustain your body’s well-being and retain energy. Carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water are the essential nutrients that compose a healthy, balanced diet.

Eating healthy foods is essential for having good health and nutrition – it protects you against many chronic non-communicable diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. If you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, show your readers the importance of healthy food, and encourage them to start a healthy diet.

Eating healthy foods means eating a variety of food that give you the nutrients that your body needs to function correctly. These nutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. In your essay about eating healthy foods, you can discuss this topic in more detail so that your readers will know why these nutrients are essential.

Eating healthy foods includes consuming the essential nutrients your body requires to function correctly (such as carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water) while minimizing processed foods, saturated fats, and alcohol. In your essay, let your readers know that eating healthy foods can help maintain the body’s everyday functions, promote optimal body weight, and prevent diseases.

Eating healthy foods comes with many health benefits – from keeping a healthy weight to preventing long-term diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer. So if you’re looking for a topic idea for your essay, you can consider the benefits of eating healthy foods to give your readers some useful information, especially for those thinking of starting a healthy diet.

Ever since we were a kid, we have all been told that eating vegetables are good for our health, but why? The answer is pretty simple – vegetables are loaded with the essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals that our body needs. So, if you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, this is an excellent topic to get you started.

Of course, you definitely can! Fresh fruits and vegetables are typically the cheapest options for starting a healthy diet. In your essay about eating healthy foods, you can include some other cheap food options for a healthy diet – this will be very helpful, especially for readers looking to start a healthy diet but only have a limited amount of budget set for their daily food.

For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

Bryan Collins is the owner of Become a Writer Today. He's an author from Ireland who helps writers build authority and earn a living from their creative work. He's also a former Forbes columnist and his work has appeared in publications like Lifehacker and Fast Company.

View all posts

Healthy Food Essay

500+ words essay on healthy food.

Before starting your daily activity, you must have food. Food is essential for our body besides water. Eating healthy food gives you the required nutrients you need to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Your daily food should have carbohydrates, proteins, water, vitamins, fat and minerals. To keep ourselves fit, we need healthy food.

When we talk about our health, healthy food plays a crucial role. It helps preserve our health, and some nutrients renew the health of various organs. Besides, healthy food is always delicious and mouthwatering. Kids, nowadays, should eat healthy food more than ever. We must encourage kids to eat healthy food so that our future generations become healthy and fit.

We should speak more often about the harmful effects of unhealthy food and the positive impact of healthy food. In this way, we can teach our kids about eating healthy foods from an early age.

To keep our internal organs healthy, we should make a habit of eating healthy food. Unhealthy food welcomes life-threatening diseases like heart attack, high or low blood pressure, increased or decreased glucose level, etc. In today’s scenario, with so many changes around the world in terms of climate, pollution, etc., eating healthy food should be on our priority list.

Advantages of Eating Healthy Food

- We get a solid and fit body by eating healthy and nutritious food.

- Healthy food also gives the body physical strength; that way, one can go about their duties comfortably.

- Eating healthy food gives good health, saving you from wasting time, money and resources seeking medical assistance and solutions.

- By eating nutritious food, we can protect our bodies from getting serious diseases like diabetes, hypertension, elevated cholesterol, and so forth.

- It also helps maintain our weight, and unhealthy food leads to obesity.

- Likewise, healthy sustenance gives us a fit and fine body and smooth skin.

- We never feel lazy in the wake of eating light and solid nourishment; instead, we feel dynamic and energetic.

- Eating healthy food helps build the body and its immunity levels, enhancing the living standards one gets to enjoy.

- It is one of the ways individuals enjoy life as they get to spend good time with friends and family.

- Healthy food is, therefore, a principal requirement for the body.

Junk Food vs Healthy Food

In today’s scenario, consumption of junk food is increasing rapidly, due to which the fast-food market is also growing fast. Junk foods are easier to prepare and delicious. It became more accessible after the arrival of the food delivery apps. People can now sit at their homes and order junk food as per their choice.

But, unknowingly, we are compromising our health by having junk food. After eating it, you will feel more satisfied. Junk food leads to poor concentration and creates digestive problems as it contains less fibre, which causes indigestion.

Junk food also results in varying blood sugar levels because it contains less protein and carbohydrates. Consumption of junk food also increases levels of triglyceride and cholesterol.

When we talk about healthy food, it contains a plethora of nutrients. It keeps our bodies physically and mentally fit. It enhances our immune system and develops our brain functionality. If we are worried about our health, we should not consume processed food.

We know that junk food seems to be more appealing and tempting, but it comes at a very high price. Therefore, we should eat healthy food to live a longer and healthier life.

Conclusion of Healthy Food Essay

We can end the essay by stating that eating healthy food is our primary need. Eating healthy food is a simple way to increase the ease of the body and the happiness of the mind. Eating junk food will make our bodies weaker and have low immunity. So, it is essential to consume healthy food to maintain good health.

Students of the CBSE Board can get essays on different topics from BYJU’S website. They can visit our CBSE Essay page and learn more about essays.

Frequently Asked Questions on Healthy Food Essay

What are the negative impacts of junk food.

1. High sodium content 2. Excessive carb intake and cholesterol intake 3. Obesity and cardiac diseases

What are some of the healthy food items?

1. Fruits and vegetables 2. Foods with high fibre content 3. Foods containing saturated fats 4. Foods with less salt and sugar

How to regulate our body with food intake?

1. Eat at regular intervals 2. Do not overeat or have junk food 3. Drink water and be hydrated

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

Essay on Healthy Food vs Junk Food

Students are often asked to write an essay on Healthy Food vs Junk Food in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Healthy Food vs Junk Food

Introduction.

Healthy food and junk food are two types of food often discussed. Healthy food is nutritious, while junk food lacks essential nutrients but is high in harmful substances.

Healthy Food

Healthy food includes fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains. They provide the body with necessary vitamins, minerals, and fiber to maintain good health.

Junk food includes fast food, sweets, and soda. They contain high amounts of sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats, which can lead to health problems like obesity and heart disease.

In conclusion, healthy food is the best choice for maintaining good health, while junk food can harm our health.

250 Words Essay on Healthy Food vs Junk Food

The escalating health crisis worldwide has brought into the spotlight the critical role diet plays in overall health. The debate between healthy food and junk food is more relevant than ever, with the former being associated with wellness and the latter with numerous health problems.

The Allure of Junk Food

Junk food, characterized by high levels of sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats, is often preferred for its convenience and addictive taste. However, the immediate gratification it offers comes with long-term health consequences. Overconsumption of junk food is linked to obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. It also negatively impacts cognitive functions, affecting academic performance and productivity.

The Power of Healthy Food

On the other hand, healthy food, rich in nutrients like vitamins, minerals, protein, and fiber, provides the body with the necessary components for optimal functioning. These foods boost the immune system, enhance cognitive abilities, and lower the risk of chronic diseases. They also contribute to maintaining a healthy weight and promote overall well-being.

Changing the Narrative

Despite the clear benefits of healthy food, the pervasive culture of fast food has normalized junk food consumption. However, changing this narrative is possible through education and awareness. Understanding the detrimental effects of junk food and the benefits of a balanced diet can help steer societal preferences towards healthier options.

In conclusion, while junk food may appeal to our taste buds and offer convenience, its long-term effects on health are detrimental. In contrast, healthy food, despite being less convenient, provides numerous health benefits, making it the superior choice. It is essential for individuals, especially college students, to make informed dietary choices for a healthier future.

500 Words Essay on Healthy Food vs Junk Food

The debate between healthy food and junk food has been a topic of interest for many years. As society becomes more health-conscious, the importance of dietary choices is increasingly recognized. This essay aims to explore the differences between healthy and junk food, their impact on our health, and the societal implications of these choices.

Understanding Healthy Food and Junk Food

Healthy food refers to foods that are rich in essential nutrients like vitamins, minerals, protein, carbohydrates, and fats. These foods include fruits, vegetables, lean meats, whole grains, and dairy products. They provide the body with the necessary nutrients for growth, development, and maintenance of overall health.

On the other hand, junk food is typically high in unhealthy fats, sugars, and salt, while being low in nutritional value. Common examples include fast food, candy, soda, and chips. These foods may be appealing due to their taste and convenience, but their regular consumption can lead to various health issues.

The Health Implications

The consumption of healthy food has numerous health benefits. It provides the necessary nutrients that the body needs to function optimally. A balanced diet can help maintain a healthy weight, boost the immune system, and reduce the risk of chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer.

Conversely, the excessive consumption of junk food can lead to obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and other health problems. High levels of sugars and fats can lead to weight gain and elevated cholesterol levels. Moreover, the lack of essential nutrients can result in deficiencies that affect the body’s normal functioning.

Societal Implications

The choices between healthy food and junk food also have broader societal implications. The rising consumption of junk food is often linked to the global obesity epidemic. The ease of access and low cost of junk food, combined with aggressive marketing strategies, contribute to its popularity, particularly among younger generations.

Meanwhile, healthy food is often perceived as more expensive and less accessible, especially in low-income communities. This creates a socio-economic divide in dietary choices and health outcomes. Promoting the consumption of healthy food and making it more accessible and affordable can help address these disparities.

In conclusion, the choice between healthy food and junk food has significant impacts on individual health and society as a whole. While junk food may offer convenience and taste, its long-term health implications cannot be ignored. On the other hand, healthy food, despite its perceived cost and accessibility barriers, provides essential nutrients for our bodies and contributes to long-term health. As we become more health-conscious, it’s crucial to make informed dietary choices for our well-being and for a healthier society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Disadvantages of Junk Food

- Essay on Harmful Effects of Junk Food

- Essay on Harmful Effects of Video Games

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges and Departments

- Email and phone search

- Give to Cambridge

- Museums and collections

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Postgraduate events

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

Healthy vs unhealthy food: the challenges of understanding food choices

- Research home

- About research overview

- Animal research overview

- Overseeing animal research overview

- The Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body

- Animal welfare and ethics

- Report on the allegations and matters raised in the BUAV report

- What types of animal do we use? overview

- Guinea pigs

- Naked mole-rats

- Non-human primates (marmosets)

- Other birds

- Non-technical summaries

- Animal Welfare Policy

- Alternatives to animal use

- Further information

- Funding Agency Committee Members

- Research integrity

- Horizons magazine

- Strategic Initiatives & Networks

- Nobel Prize

- Interdisciplinary Research Centres

- Open access

- Energy sector partnerships

- Podcasts overview

- S2 ep1: What is the future?

- S2 ep2: What did the future look like in the past?

- S2 ep3: What is the future of wellbeing?

- S2 ep4 What would a more just future look like?

- Research impact

We know a lot about food but little about the food choices that affect the nation’s health. Researchers have begun to devise experiments to find out why we choose a chocolate bar over an apple – and whether ‘swaps’ and ‘nudges’ are effective.

Perceiving food as tasty is important. It’s not good enough simply to tell people what is healthy if they don’t think those foods are also tasty. Suzanna Forwood

The solution to the obesity epidemic is simple: eat less, move more. But take a deep breath before you type these four words into a search engine. The results exceed 9 million. Of the top four results, two websites argue against the statement and two for it. Below, arguments about eating and exercise rage fast and furious with dozens of assertions backed by equations, flowcharts, promises of slimming success, and lists of the latest superfoods.

“Despite all we know about food, we know remarkably little about the process of food choice,” says Dr Suzanna Forwood, until recently Research Associate at the Behaviour and Health Research Unit (Cambridge University) and now Lecturer in Psychology at Anglia Ruskin University. “In a supermarket we’re bombarded with the thousands of products on the shelves and but most of the time we happily make relatively quick decisions about what to buy. So what’s going on in our minds when we reach out for our favourite breakfast cereal?”

When it comes to eating, we’re all experts. We’re secure in our own opinions (and prejudices) and have no shortage of advice for everyone else. The truth is that, in common with many human activities, our relationship with food is complex and deeply embedded in culture. Forwood says: “Whenever I give a talk, even to an academic audience, people will listen to me talk about the big picture and then come up to me afterwards to tell me about their personal experiences – typically what they spotted in other people’s trolleys the day before.”

We might broadly agree that eating less (and better) and moving more, a message endorsed by the NHS, makes sense – but do we act accordingly? We don’t. Finding out exactly what people eat is hard, finding out why they make those choices is harder – and changing those eating patterns is harder still. “Most of the data we have – and we have lots of it – is observational rather than experimental,” says Forwood. “There have been relatively few experiments looking at food choice – and those that have been carried out tend to have a low number of participants.”

In the late 1980s government began to realise that it was facing an obesity epidemic on a scale that demanded intervention. Levels of obesity in the UK have tripled since 1980: almost 25% of the adult population is now obese with the UK topping the tables for Western Europe. These worrying figures led to nationwide initiatives to promote healthy living – and increased efforts to understand food choice behaviour.

Research has shown that obesity is linked to deprivation and low levels of education – as well as to a whole range of life-threatening conditions. Top of the list of ‘avoidable diseases’ associated with obesity is type 2 diabetes (treatment of type 2 diabetes costs the NHS an estimated £8.8 bn each year), followed by cancer, high blood pressure and heart disease. “In the past, weight status has long been regarded as a matter of personal choice,” says Forwood. “And this is reflected by the government’s desire for non-regulatory interventions.” The preference for a light touch approach is exemplified by the establishment of the so-called Nudge Unit (Behavioural Insight Team).

In 2009 the government launched its Change4Life campaign as a ‘movement’ to improve the nation’s health. Change4Life’s online advice for adults makes a series of suggestions for ‘swaps’ and ‘nudges’. Swap a large plate for a smaller one, swap fast eating for slow eating, and swap food high in fat or sugar for healthy fruit and vegetables. Look closely at labelling and make healthy choices based on a comparison of calories and nutritional information.

The current focus is on reducing intake of sugar – not the sugar that occurs naturally in fruit, or even the sugar we sprinkle on our cereal, but the hidden sugar that sweetens so many processed foods and flavours so many popular drinks. In the case of sugar, what is proposed is a financial nudge in the form of a ‘sugar tax’. “Taxes have been shown to be effective but they have to be carefully designed,” says Forwood. “Sugar taxes, for example, need to avoid raising the price of fruit juices which are high in sugar.”

Do other strands of swaps and nudges work? Research suggests that people are remarkably resilient in their food choices. Taste emerges as the most important factor. Forwood’s work shows that healthy foods (such as fruit and vegetables) are not perceived as tasty, particularly by groups who are reluctant to choose healthy foods. She says: “That might seem tautological but there is strong observational data to suggest that perceiving food as tasty is important. It’s not good enough simply to tell people what is healthy if they don’t think those foods are also tasty.”

The perception of healthy foods as less tasty than unhealthy foods prompts the question: could product labelling, promoting the tastiness of healthy foods, nudge consumers into making ‘better’ choices when they’re shopping. In research published last year, Forwood and colleagues looked at the ‘nudging power’ of labelling to increase the percentage of people who might say ‘no’ to a chocolate bar and ‘yes’ to an apple as part of a notional meal deal.

In the online study, around half of a representative sample of people expressed a preference for an apple when given the choice of apple or chocolate bar. Participants were divided into five groups and given the same choice (apple or chocolate bar) with the apple labelled in five different ways: ‘apple’, ‘healthy apple’, ‘succulent apple’, ‘healthy and succulent apple’, ‘succulent and healthy apple’. Labels combining both health and taste descriptors significantly increased the rate of apple selection – to 65.9% in the case of ‘healthy and succulent’ and 62.4% for ‘succulent and healthy’.

Another study , also published last year, looked at the potential for food swaps – often used as part of social media campaigns – as a means for reducing dietary levels of energy, fat, sugar or salt. Using the model of an online supermarket, built as a testing platform, participants were asked to complete a 12-item shopping task. In the course of the purchasing process, they were offered alternatives with lower energy densities (ED). For each item, lower ED alternatives were offered or imposed, either at the point of selection or at the checkout.

“Our study showed that within-category swaps did not reduce the ED of food purchases. Only a minority of swaps were accepted by the consumer and the notional benefits to swaps were slight. It was striking that more than 47% of the participants offered alternatives did not accept any of the swaps they were offered,” says Forwood. “Female participants and better-off participants were more likely to accept swaps. This was predictable in that these are the people who we know from other research typically make healthier choices anyway.”

It has been argued that omnipresence of food imagery in the modern built environment, and via all kinds of media, contributes to rising rates of obesity with adverts for less healthier foods identified as a driver for consumption of such foods. A study in Australia showed that people who watched commercial television channels (which carry advertising for fast foods) were, perhaps not surprisingly, more likely to purchase TV dinners .

“What we’re talking about here is, of course, observational data,” says Forwood, “It may, for example, be that people who consume TV dinners are more attracted to certain television programmes that are on commercial channels. Remember that huge sums of money are spent targeting TV adverts in order to make sure that the right population sees them. But this raises the question: could advertising represent an opportunity for policy makers looking to promote consumption of healthier choices?”

‘Priming’ is described as a psychological effect in which exposure to a stimulus – such as advertising – modifies behaviour. When Forwood and colleagues tested the effectiveness of priming by asking volunteers to look at an advertisement for healthy food (such as fruit) and then choose between healthy and unhealthy, they found that the priming had little difference. The observations were different, however, when the participants were hungry, in which case the preference for the energy dense foods rose. However, when the hungry volunteers were shown an advertisement for fruit in advance of their choice, the ‘hungry factor’ was offset by the priming.

The initial experiment was carried out in Cambridge where the participants were predominantly female, well-educated and older – and likely to be in favour of healthy eating. When the experiment was carried out with a more nationally representative sample, the results showed that priming was ineffective in socially disadvantaged groups. “These people are hard to reach and represent a real challenge to policy-makers,” says Forwood. “Research tells us that 89% of people want to make dietary changes to improve their health. We need to identify the levers that can support them.”

Read this next

Fish fed to farmed salmon should be part of our diet, too, study suggests

Farm to factories

AI predicts healthiness of food menus

Genetic mutation in a quarter of all Labradors hard-wires them for obesity

Nancy's Fruit Salad by John Hritz

Credit: Flickr Creative Commons

Search research

Sign up to receive our weekly research email.

Our selection of the week's biggest Cambridge research news and features sent directly to your inbox. Enter your email address, confirm you're happy to receive our emails and then select 'Subscribe'.

I wish to receive a weekly Cambridge research news summary by email.

The University of Cambridge will use your email address to send you our weekly research news email. We are committed to protecting your personal information and being transparent about what information we hold. Please read our email privacy notice for details.

- food choices

- Public health

- Global food security

- food security

- Suzanna Forwood

- Behaviour and Health Research Unit (BHRU)

- School of Clinical Medicine

- Cambridge Institute of Public Health

Related organisations

- Anglia Ruskin University

Connect with us

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility statement

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 29 November 2018

Availability of healthier vs. less healthy food and food choice: an online experiment

- Rachel Pechey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6558-388X 1 &

- Theresa M. Marteau 1

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 1296 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

26 Citations

47 Altmetric

Metrics details

Our environments shape our behaviour, but little research has addressed whether healthier cues have a similar impact to less healthy ones. This online study examined the impact on food choices of the number of (i) healthier and (ii) less healthy snack foods available, and possible moderation by cognitive load and socioeconomic status.

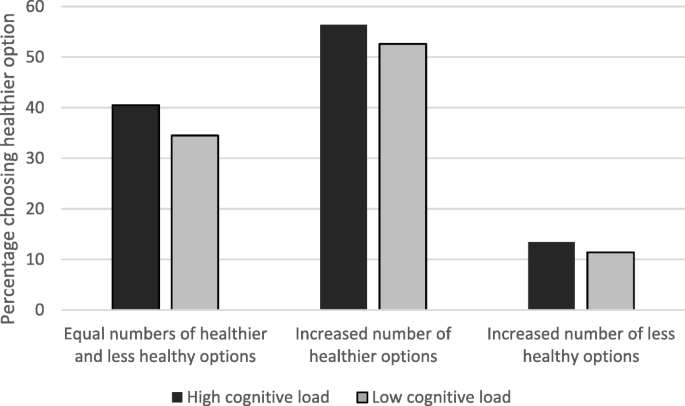

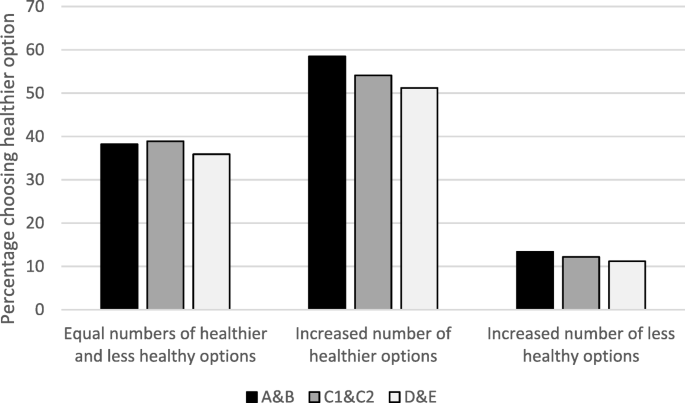

UK adults ( n = 1509) were randomly allocated to one of six groups (two cognitive load x three availability conditions). Participants memorised a 7-digit number (7777777: low cognitive load; 8529713: high cognitive load). While remembering this number, participants chose the food they would most like to eat from: (a) two healthier and two less healthy foods, (b) six healthier and two less healthy foods, or (c) two healthier and six less healthy foods.

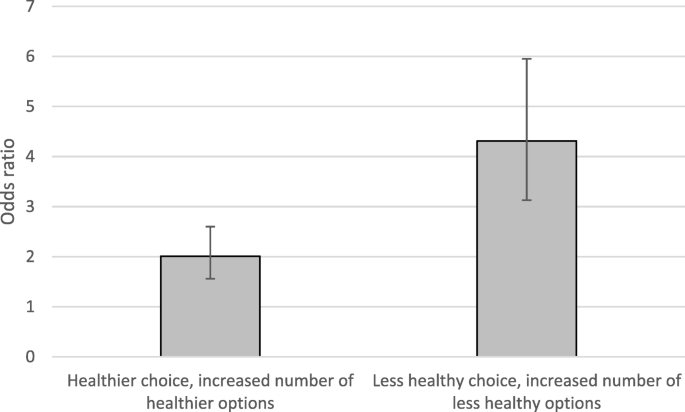

Compared to being offered two healthier and two less healthy options, the odds of choosing a healthier option were twice as high (Odds Ratio (OR): 2.0, 95%CI: 1.6, 2.6) with four additional healthier options, while the odds of choosing a less healthy option were four times higher (OR: 4.3, 95%CI: 3.1, 6.0) with four additional less healthy options. There were no significant main effects or interactions with cognitive load or socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

This study provides a novel test of the impact of healthier vs. less healthy food cues on food choice, suggesting that less healthy food cues have a larger effect than healthier ones. Consequently, removing less healthy as opposed to adding healthier food options could have greater impact on healthier choices. Studies are now needed in which choices are made between physically-present foods.

Peer Review reports

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, now cause the majority of premature preventable deaths worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. Patterns of unhealthy behaviour, including excessive energy intake, are key contributors to these NCDs, and are socially patterned, i.e. less healthy behaviours are generally more common amongst the poorest, contributing in turn to the substantial socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy and years lived in good health.

One strategy that may be effective in targeting these behavioural risk factors is to target the physical micro-environment, addressing the multiple cues – aspects of our environments that can influence behaviour – which act detrimentally by limiting healthier options or promoting less healthy ones [ 3 ]. This approach (sometimes termed ‘choice architecture’ or ‘nudging’) [ 4 , 5 , 6 ] is based on dual process models of behaviour [ 7 , 8 ]. It has been hypothesised that interventions targeting non-conscious processes regulating behaviour are more effective than more information-based interventions, as they do not necessarily rely on individuals’ cognitive resources [ 3 , 9 ]. One such environmental cue is the availability (including both the number and range) of healthier vs. less healthy foods, which represents one of the top three interventions suggested in the McKinsey Global Institute report on obesity [ 10 ] as having the highest likely impact across the population. While the mechanisms underlying the effects of altering availability have not been explored to our knowledge, increasing the availability of product(s) may influence consumption by increasing the visibility or salience of these products to consumers, and/or increased options may lead to these appealing to a wider range of people. Evidence is beginning to accumulate to support the effectiveness of targeting product availability to change behaviour [ 11 , 12 , 14 ].

One choice when designing interventions to alter availability is whether to increase healthier foods, decrease less healthy foods or both simultaneously. Thus far, there is a paucity of evidence on this, although observational data suggests that the availability of less healthy foods but not fruit and vegetables is associated with body mass index (BMI) [ 15 ]. Establishing if there is a difference in response to healthier vs. less healthy food cues could help prioritise interventions that are likely to be most effective to change behaviour.