The Human Condition: What It Is, How to Find It, Why We Talk About It, & How To Write About It

- Post author By Riley M

- Post date January 18, 2021

I remember being in high school when my English teachers would toss out the phrase “the human condition” as we discussed the dystopian nightmare of Orwell’s 1984 , or Jay Gatsby’s unshakeable obsession with the past. The phrase, at first, meant nothing to me– I had never heard of it before, yet my teachers seemed to think it was relevant enough to bring up with nearly every novel we read. I even remember once being told by a fellow classmate, “If you write about the human condition in your paper, you’ll get a good grade.”

So, what really is the human condition? And why is it worth talking about? And why is its mention in an essay rewarded with a good grade? Well, let’s first say that I don’t think that last bit is necessarily always the case, but that just shows us that the human condition is definitely worth discussing.

‘Defining’ the Human Condition

Instead of listing some sort of dictionary definition of the human condition, let’s go at it this way– referring to something as relating to “the human condition” means that it captures some aspect of the universal experience of being a human.

And this “aspect” I’m talking about definitely isn’t just one kind of thing. It isn’t just one emotion, or one experience, or one characteristic. I mean, think of all the things that you know about being human, just for the next five seconds. I immediately think of things like becoming attached to people, falling in love, experiencing loss, feeling lonely, being flawed. You probably thought of different ones than I did, and those are only aspects that we thought of in five seconds. So, if we think of all the different kinds of literature and writing over the course of history, we can imagine how many different aspects of the human condition have been depicted.

But Why the Human Condition?

Now, obviously, when we read a novel, there’s no blaring bold faced font that says THIS CHARACTER’S EXPERIENCE OF HEARTBREAK IS AN ASPECT OF THE HUMAN CONDITION . No, the wonderful variety of authors over the thousands of years of human writing have become much more subtle (and creative) than that. Instead, through their descriptions of characters’ emotions and experiences (often crafted with really cool diction and purposeful narration), they showcase aspects of the human condition. This is why when you’re reading a book, and a certain character is going through something, you are often able to think, “Oh yeah, I understand that feeling.” This is because it’s something that we’ve all experienced at one point, or will experience, because we’re all humans and we all deal with highs and lows.

And this is why writers talk about it—to connect with their readers. And also to convey some message about humanity, to portray something about this experience that they find compelling and important to their readers.

However, this understanding of the human condition can seem a bit convoluted, at it raises some questions in skeptics. The question on the lips of many of these folks is: “Can there really be one human condition?” And honestly, there is discussion to be had there.

Back to Definitions

We are all extremely different as humans, with our own identities, backgrounds, races, genders–the list goes on and on. So some say that there can’t be just one human condition when we take into account all these distinctions. However, what the idea of the human condition aims to convey is not that these differences don’t exist or that they are invalid to experience, but instead that we all have a commonality, too; that commonality is what it aims to capture. This is because the human condition is about general experiences that people go through regardless of what sets us all apart; people all deal with growing up, love, death, friendship, and maturation. While our differences and various identities often color these aspects of life and present them in different ways, they are still things that, at their roots, we all experience universally, more or less.

How to Implement It in Your Writing

Alright, so we know what the human condition is, how to find it when we’re reading, and why it’s there on the page—now all that’s left is including it in our own writing. After all, don’t we all want that “guaranteed A” on our next English essay? (Once again, I do not think that’s necessarily true).

As far as how to write about it, I think you have the tools with you already, after everything we discussed. You just need to go ahead and use them now. When you’re talking about a quote in a rhetorical analysis, explain how that author is exemplifying the human condition there through, for example, the character’s grief after losing a loved one. Or through displaying the main character’s infatuation with their new lover. The opportunities are endless, because the human condition encompasses the immense universality of simply being us , and authors are representing it in new and different ways every day.

Share this:

The Human Condition (Definition + Explanation)

There are over 7.5 billion people alive today. We live different lifestyles, have different opinions, and follow different rules in our different societies. But there are things that remain true for all 7.5+ billion people around the world. We are all born. We all grow. We all die.

Being human means we love, struggle, hope, and sometimes feel lost. We ask big questions like "Why are we here?" and "What's our purpose?" Throughout history, artists, writers, and thinkers have tried to explore and understand these feelings and questions.

In this article, we'll journey through the maze of the human experience, touching on emotions, relationships, dreams, and more. It's like a mirror reflecting what it means to be us. So, are you ready to dive deep and explore the essence of being human? Let's get started!

What Is The Human Condition?

The concept of the human condition refers to the shared experiences, emotions, and challenges that are common to all human beings, regardless of culture, race, or background. It encompasses both the positive and negative aspects of human existence, including joy, love, and fulfillment, as well as suffering, pain, and mortality.

Human condition is often confused with human nature, but human nature is just one part of the human condition. The term “human nature” refers to the traits, behaviors, and other characteristics that are natural to human beings.

Human condition is much larger than just human nature. It includes the characteristics natural to all humans, but also looks at the events that all humans go through and the moral conflicts that they face. It looks at what we do with our natural characteristics and how we use them to shape the world around us.

You may have a very different life from someone across the world. But you both show love and affection toward others. You both experience emotions like fear, happiness, or grief. While you may not agree with someone’s political views or behavior, when you look closely at the motives behind your actions, you may find that you hold similar values or want to protect similar things.

Where do these feelings come from? Why are we so similar at our core, yet so different on the surface? What is the point of being born, living, accomplishing things, making an impact, only to die?

These are big questions. You don’t have a definite answer. I don’t have a definite answer. The smartest people in the world don’t have definite answers. But contemplating these questions has been central to psychology, philosophy, art, literature , and religion. One might say that thinking about the human condition is part of the human condition.

Effect of Human Condition

It’s hard to define what the human condition is without picking specific beliefs about why humans are on this Earth. Beliefs about the human condition may influence a person’s personality or behavior. A religion’s views on the human condition, for example, may be the basis for the rules a follower of that religion lives by. If a person believes there is a higher power behind the human condition, they may be inclined to follow the teachings of that higher power.

The human condition influences psychology and what psychologists have to say about the human condition. Like religion, art, or science, psychology does not provide one answer that explains the human condition.

The Human Condition In Psychology

What drives behavior?

For some psychologists, the answer lies in human nature. Our genes influence the traits that we develop and the behaviors we display later in life.

For others, the answer can be found in the way that we are nurtured. The environment we grow up in influences the person that we become. Trauma, comfort, and relationships all play a part in how we see the world and how we see our place in it.

Nature vs. nurture is one of the great debates in psychology. All of these debates can be traced back to the human condition:

- The mind vs. body debate

- Free will vs. determinism

- Holism vs. reductionism

The list goes on and on. These debates, and our questions about the human condition, work in a cycle. We can only determine that the mind and body are separate by studying the human condition. By choosing a side of this debate, we say a lot about the human condition.

These debates are found within many approaches to psychology. These different approaches, including behaviorism or humanistic psychology, are rooted in theories about the human condition. Some of these approaches have become “outdated” and replaced with other approaches. What does this say about psychology’s view of the human condition?

Humanistic Psychology and the Human Condition

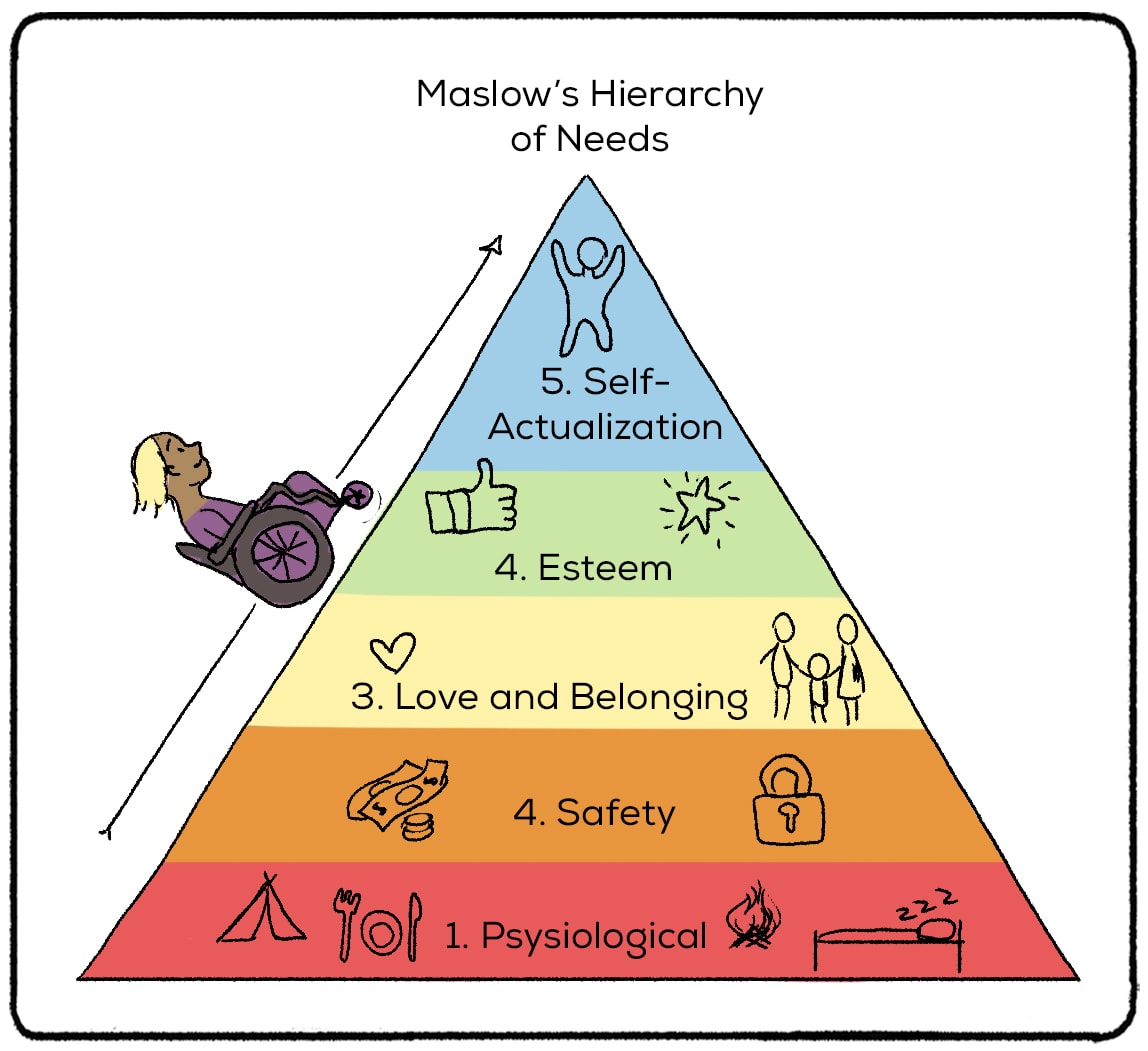

Psychology underwent a major shift, starting in the 1940s. In 1943, Abraham Maslow created a hierarchy of needs that speaks to the human condition. He believed that once our basic needs (including water, food, love, and safety) are achieved, humans can start to self-actualize.

The process of self-actualization includes personal development, growth, and fulfilling one’s true potential. While a self-actualized person is independent and accepts themselves, they may turn their focus to larger problems and begin to help others. A self-actualized person may seek the answers about the human condition, with the ability to get closer to the answers because they are fulfilled in other capacities.

This is a very positive position to be in, and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs gives us a road map to get there. It kickstarted the popularity of humanistic psychology, a so-called “third-wave” of psychology that follows the more pessimistic school so behaviorism and psychoanalysis.

Positive Psychology

Humanistic psychology is often compared to positive psychology. These two schools of thought have similar goals and views. They are both a response to behaviorism and psychoanalysis. The biggest difference between these two approaches is how they set out to study, test, and confirm their theories. While humanistic psychology relies on more qualitative data, positive psychology chooses the quantitative route.

Positive psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on the positive aspects of human experience, including happiness, well-being, and personal growth. In the context of the human condition, positive psychology offers a framework for understanding how we can cultivate positive emotions and experiences, even in the face of adversity and challenges.

One key concept in positive psychology is the idea of resilience, which refers to the ability to bounce back from adversity and to thrive in the face of challenges. Resilience is a key aspect of the human condition, as we all face difficulties and setbacks at various points in our lives. By cultivating resilience through practices like mindfulness, gratitude, and social support, we can better navigate the challenges that life presents us with.

Ways to Explore Humanity

Psychologists, philosophers, and people have been seeking the answers to life’s biggest questions for centuries. Why not join them? Recognizing the importance of these questions is the first step to finding the answer.

Educate Yourself

People study the great philosophers to discover their thoughts on life and humanity. (Ancient Grecians had a lot of time on their hands to debate these things!) Whether it’s reading a book or attending a class on philosophy, education on the mind and humanity can give you a lot of basic information on what perspectives are out there. You might find that you agree with some philosophers. Or, you blend their perspectives together to form your own beliefs. At the very least, you’ll be able to sound very smart at parties when you discuss the world’s greatest minds!

Try New Things

The answers to the world’s biggest questions are probably not found at home. (Or maybe they are!) If you are seeking a new perspective, try new things. Travel to a foreign country. Talk to someone that you wouldn’t normally talk to. Try to live your life in the shoes of a complete stranger for a day. The more you expose yourself to, the more you will see how other humans view the world. Every individual’s perspective is so limited. There are billions of people living complex, exciting, dramatic lives. No one will be able to understand every person on this Earth, but trying new things is the best way to understand more people.

Write Out Your Experiences

How do you make sense of the world? You can think about it. You can also write it down! Our minds process emotions differently when we write them on paper versus when we sit around and think about them. Write out your experiences like you’re writing a story. What does your story say about the human condition?

Here are a few other ideas to explore humanity and experience the full human condition:

- Explore the role of culture in shaping the human condition. How do cultural beliefs and values shape our experiences and understanding of the world around us? How does culture influence our sense of identity, belonging, and purpose?

- Investigate the ways in which different individuals and groups experience the human condition differently. For example, how do experiences of race, gender, sexuality, and socioeconomic status shape our understanding of the human condition? How do these experiences intersect and influence each other?

- Reflect on the role of emotions in the human condition. How do emotions like joy, love, fear, and sadness shape our experiences and understanding of the world? How do we cope with challenging emotions like grief and anxiety?

- Examine the quest for meaning and purpose in the human condition. How do we find meaning in our lives, and what gives our lives a sense of purpose and significance? How does this quest for meaning shape our experiences of happiness, fulfillment, and well-being?

- Consider the impact of technology on the human condition. How have advances in technology changed our experiences of the world and each other? How do we navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by technology in the context of the human condition?

Quotes About the Human Condition

What do the world’s greatest psychologists, philosophers, and authors have to say about humanity? Let’s find out!

Quotes About Human Nature

“Humanity is an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.” -Mahatma Gandhi

“Whatever the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve.” -Napoleon Hill

“I have learned over the years that when one’s mind is made up, this diminishes fear.” -Rosa Parks

“For every reason it’s not possible, there are hundreds of people who have faced the same circumstances and succeeded.” -Jack Canfield

“To argue with a man who has renounced the use and authority of reason, and whose philosophy consists in holding humanity in contempt, is like administering medicine to the dead, or endeavoring to convert an atheist by scripture.” -Thomas Paine

“In my view, the best of humanity is in our exercise of empathy and compassion. It's when we challenge ourselves to walk in the shoes of someone whose pain or plight might seem so different than yours that it's almost incomprehensible.” -Sarah McBride

Quotes About the Purpose of Humanity

“The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity.” -Leo Tolstoy

“Life is ours to be spent, not to be saved.” -D. H. Lawrence

“The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.” -Fyodor Dostoyevsky

“True glory consists in doing what deserves to be written, in writing what deserves to be read, and in so living as to make the world happier and better for our living in it.” -Pliny the Elder

“The cities, the roads, the countryside, the people I meet – they all begin to blur. I tell myself I am searching for something. But more and more, it feels like I am wandering, waiting for something to happen to me, something that will change everything, something that my whole life has been leading up to.” -Khaled Hosseini

“Life is difficult. Not just for me or other ALS patients. Life is difficult for everyone. Finding ways to make life meaningful and purposeful and rewarding, doing the activities that you love and spending time with the people that you love – I think that’s the meaning of this human experience.” -Steve Gleason

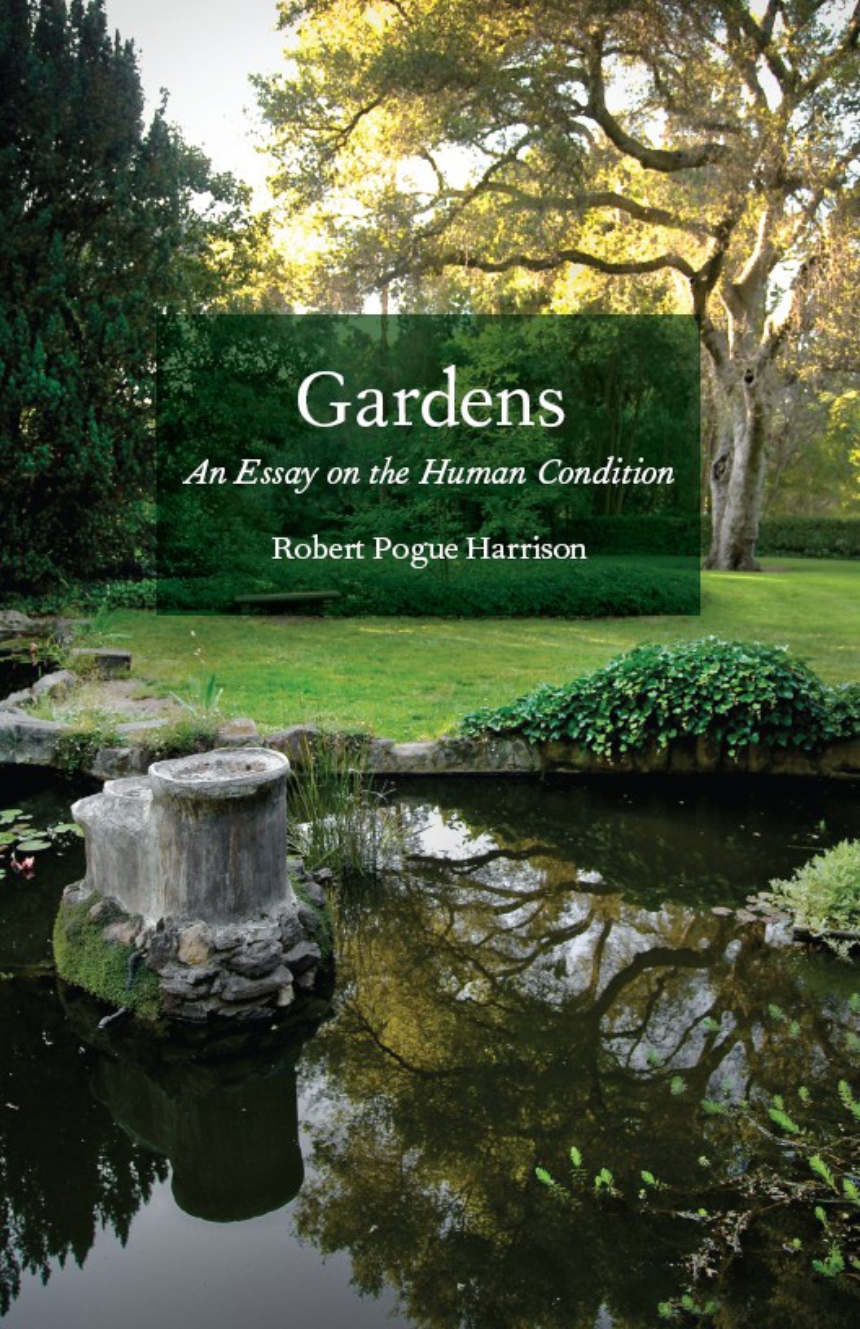

Books About The Human Condition

As P.T. Barnum once said, “Literature is one of the most interesting and significant expressions of humanity.” Plenty of books have been written about what it means to be a human and how to carry forth on our journeys. These are just a few favorites. Enjoy them when you’re in a philosophical mood.

“The Alchemist” by Paulo Coelho

“Ishmael” by Daniel Quinn

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari

“Man's Search for Meaning” by Viktor E. Frankl

“Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by Robert M. Pirsig

“The Midnight Library” by Matt Haig

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman

“And the Mountains Echoed” by Khaled Hosseini

Overwhelmed By These Questions? Reach Out to a Professional

The main schools of thought in psychology today have a more optimistic focus. But not everyone has such positive views on the human condition and why we are on Earth. Thinking about the human condition and the nature of our existence can be overwhelming. We all experience conflicting feelings and anxiety over these topics. If this anxiety is becoming overwhelming, reach out to a professional. Today’s therapists and psychiatrists are trained to help navigate the conflicts of the human condition and put you on a path toward self-actualization.

Related posts:

- 40+ Famous Psychologists (Images + Biographies)

- Dream Interpreter & Dictionary (270+ Meanings)

- PERMA Model of Happiness (Examples + Images)

- The Emotion Wheel (9 Wheels + PDF + How To Use)

- Martin Seligman Biography - Contributions To Psychology

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Stories of Our Lives and 'The Human Condition'

Being human confers on us dramatic life stories, both joyful and painful..

Posted October 3, 2021 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- "The human condition" is used ironically to refer to the state of being a human, with both the wondrous and the woeful feelings we experience.

- We are the only species that can describe in words and works of art our perceptions, thoughts, and feelings to ourselves and to others.

- We all have diverse and unique life stories, but each one of them depicts times love and loss, communality and loneliness, joy and sadness.

The phrase "the human condition" has always fascinated me.

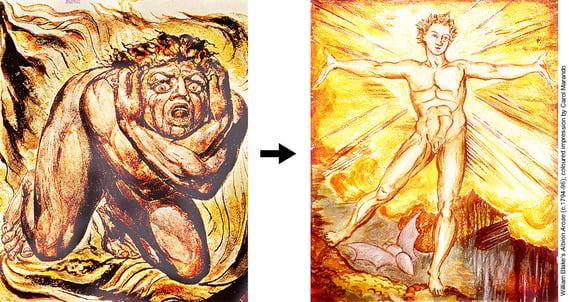

It was coined in 1958 by the political thinker Hanna Arendt, and summarizes for me the complexities, and both the rewarding and difficult experiences of being a human being.

Of all earthly creatures, only we humans can describe through words our sensed perceptions, thoughts and feelings, and convey the touching stories of our lives. Our cognitive and verbal powers enable us to consciously experience, exult, and endure.

Our life stories are unique and diverse yet they all contain compelling narratives of drama and romance, pain and disappointment, joys and achievements.

There are oft-asked questions as to whether the “human condition” is a serious affliction with which we cope or endure, or conversely, whether it is a privilege and blessing for which we should be grateful and enjoy? The answer is, of course, “Both.”

We have wide ranges of emotions at different times, from love to hate, camaraderie to rancor, generosity to selfishness, and celebration to sadness.

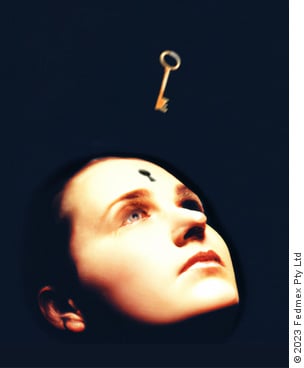

We can keep our personal feelings and thoughts private, ‘locked’ in our private cerebral 'vaults,' or we can choose to share (or not) our stories with chosen confidantes.

As a psychiatrist I am interested in diagnoses and treatments, but I’m particularly moved by the varied stories of peoples’ lives. My career has allowed me the privilege of learning about others’ fears, loves, hopes, and meaningful relationships.

I was motivated to work with and help people with psychological and emotional challenges. I was also captivated by the mysterious workings of the human mind (my own included), the places it takes one, the emotions it stirs, and the dreams it produces. It is an intellectually challenging area of study, enabling clinical work, education , research, and writing.

Personal experiences also influenced my career choice: I had a brother born with severe autism , my mother had recurrent depressions, a close classmate had committed suicide , and to be sure, I harbored my own self-doubts and anxieties.

I first became interested in life stories from my parents whose lives were like multicolored tapestries, dark narratives of early poverty, antisemitism, immigration, and strife, as well as later colorful tales of family, accomplishments, and generativity.

I’ve thus been fortunate to ‘accompany’ people on parts of their journeys, which are always moving stories. I am always struck by the uniqueness of life stories, the diverse personalities we inhabit, the dramas and challenges we face, and the loves and joys we experience. Our brief life journeys are unpredictable, complex, and moving.

We humans are a social species, and in these roiling times of conflicts, viruses, and uncertainties abounding in our lives, we need each other more than ever. An important paradox (and sad tragedy) is that at the very time in human existence when we are “hyperconnected” by the internet and social media , we frequently lead intensely private and even lonely lives. The sad fact is we are now less emotionally connected, more alienated, even estranged from each other.

We are a social species, and we thrive on “social cohesion,” our relationships with others. (This is admittedly more difficult when the pandemic necessitates “social distancing.”) Our mutual sharing of feelings and ideas are vital to our well-being, but we are too often isolated and disconnected that we have little meaningful time to spend with each other. We are so preoccupied that we haven’t the time or the interest to listen and really hear each other.

The human condition is complex: We can live in atmospheres of isolation, camaraderie, or enmity. We can experience mutual cooperation , tolerance, and love, or we can succumb to the negative parts of our natures, like intolerance, aggression , racism , and hatred. We can live our lives in an avoidance bubble, in relative solitude and private discordance, or we can live in social atmospheres of communality and harmony.

Our human condition is a blessing that can bring psychological, social, and spiritual sustenance and meaning to our lives. But that same ‘condition’ can at times bring us major distress.

The ‘condition’ (painful) part of the human condition, however, is existential, and not a psychiatric disorder that necessitates treatment. Medication and psychotherapy are not the answers to the challenging aspects of the human condition.

What humanity needs for the prevention and mitigation of the demons in our nature are more education, egalitarianism, and exposure to the better angels in our midst and our souls.

It will take commitment and hard cooperative work to engender our human resilience so that we maximize our strengths and overcome our intrinsic human quandaries.

“The human condition” can be our salvation or our curse. I yearn for when it is less a metaphor for a psychological ‘mixed bag’ of both the supportive and the difficult parts of being human, and more a description of how we have transcended our harmful frailties and faults. We have shown that we can evolve to better versions of ourselves.

In spite of human antipathies and conflicts, I believe we can achieve a mutually humane and benevolent existence, and leave a positive emotional footprint. The very nature of our life stories depends on how we live, work and play together, or how we fail to do so.

Saul Levine M.D. , is a professor emeritus at the University of California at San Diego.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was one of the most influential political philosophers of the twentieth century. Born into a German-Jewish family, she was forced to leave Germany in 1933 and lived in Paris for the next eight years, working for a number of Jewish refugee organizations. In 1941 she immigrated to the United States and soon became part of a lively intellectual circle in New York. She held a number of academic positions at various American universities until her death in 1975. She is best known for three works that had a major impact both within and outside the academic community. The first, The Origins of Totalitarianism , published in 1951, was a study of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes that generated a wide-ranging debate on the nature and historical antecedents of the totalitarian phenomenon. The second, The Human Condition , published in 1958, was an original philosophical study that investigated the fundamental categories of the vita activa (labor, work, action). The third, Eichmann in Jerusalem , reported on the trial of a major Nazi perpetrator and coined the controversial term “banality of evil”. In addition to these important works, Arendt published a number of influential essays on topics such as the nature of revolution, freedom, authority, tradition and the modern age. At the time of her death in 1975, she had completed the first two volumes of her last major philosophical work, The Life of the Mind , which examined the three fundamental faculties of the vita contemplativa (thinking, willing, judging).

1. Biographical Sketch

2. introduction, 3. arendt’s concept of totalitarianism, 4.1 arendt’s conception of modernity, 4.2 the vita activa : labor, work and action, 4.3 freedom, natality and plurality, 4.4 action, narrative, and remembrance, 4.5 action and the space of appearance, 4.6 action and power, 4.7 the unpredictability and irreversibility of action, 5.1 citizenship and the public sphere, 5.2 citizenship, agency, and collective identity, 6.1 eichmann in jerusalem : arendt’s reconceptualization of evil, 6.2 the moral significance of thinking and judgment, 6.3 self-consciousness, social pressure and autonomy, 6.4 judgment and politics: two models, 6.5 opinion and truth in politics, works by arendt, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

Hannah Arendt, one of the leading political thinkers of the twentieth century, was born in 1906 in Hannover and died in New York in 1975. In 1924, after having completed her high school studies, she went to Marburg University to study with Martin Heidegger. The encounter with Heidegger, with whom she had a brief but intense love-affair, had a lasting influence on her thought. After a year of study in Marburg, she moved to Freiburg University where she spent one semester attending the lectures of Edmund Husserl. In the spring of 1926 she went to Heidelberg University to study with Karl Jaspers, a philosopher with whom she established a long-lasting intellectual and personal friendship. She completed her doctoral dissertation, entitled Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin (hereafter LA) under Jaspers’s supervision in 1929. She was forced to flee Germany in 1933 as a result of Hitler’s rise to power, and after a brief stay in Prague and Geneva she moved to Paris where for six years (1933–39) she worked for a number of Jewish refugee organisations. In 1936 she separated from her first husband, Günther Stern, and started to live with Heinrich Blücher, whom she married in 1940. During her stay in Paris she continued to work on her biography of Rahel Varnhagen , which was not published until 1957 (hereafter RV). In 1941 she was forced to leave France and moved to New York with her husband and mother. In New York she soon became part of an influential circle of writers and intellectuals gathered around the journal Partisan Review . During the post-war period she lectured at a number of American universities, including Princeton, Berkeley and Chicago, but was most closely associated with the New School for Social Research, where she was a professor of political philosophy until her death in 1975. In 1951 she published The Origins of Totalitarianism (hereafter OT), a major study of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes that soon became a classic, followed by The Human Condition in 1958 (hereafter HC), her most important philosophical work. In 1961 she attended the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem as a reporter for The New Yorker magazine, and two years later published Eichmann in Jerusalem (hereafter EJ), which caused a deep controversy in Jewish circles. The same year saw the publication of On Revolution (hereafter OR), a comparative analysis of the American and French revolutions. A number of important essays were also published during the 1960s and early 1970s: a first collection was entitled Between Past and Future (hereafter BPF), a second Men in Dark Times (hereafter MDT), and a third Crises of the Republic (hereafter CR). At the time of her death in 1975, she had completed the first two volumes on Thinking and Willing of her last major philosophical work, The Life of the Mind , which was published posthumously in 1978 (hereafter LM). The third volume, on Judging , was left unfinished, but some background material and lecture notes were published in 1982 under the title Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy (hereafter LKPP).

Hannah Arendt was one of the seminal political thinkers of the twentieth century. From the very beginning, her interest was not in the human being in the singular, but in human beings in the plural and in the conditions and forms of their shared lives. Even though Arendt only became politically interested after her dissertation, in this first work she already asks about the conditions of the possibility of a human community (Stark/Scott 1996, 116). By analyzing the Augustinian concept of love, she criticizes the worldlessness of the philosophical tradition (LA, 112). The question of how the world can be transformed from a natural kosmos , in which people are initially strangers, into a polis shared by all, has pervaded Arendt’s writings since her dissertation. Thus, the leitmotif of her work is the question of how people can live together in a common world (Tömmel 2013).

The power and originality of her thinking is evident in works such as The Origins of Totalitarianism , The Human Condition and The Life of the Mind . In these books and numerous essays she grappled with the most crucial political events of her time, trying to grasp their meaning and historical import, and showing how they affected our categories of moral and political judgment. In her political writings, and especially in The Origins of Totalitarianism , Arendt claimed that the phenomenon of totalitarianism has broken the continuity of Occidental history, and has rendered meaningless most of our moral and political categories. Faced with the events of the Holocaust and the Gulag, we can no longer go back to traditional concepts and values, so as to explain the unprecedented by means of precedents, or to understand the monstrous by means of the familiar. The burden of our time must be faced without the aid of tradition, or as Arendt once put it, “without a bannister” (RPW, 336). What was required, in her view, was a new framework that could enable us to come to terms with the twin horrors of the twentieth century, Nazism and Stalinism. She provided such framework in her book on totalitarianism, and went on to develop a new set of philosophical categories that could illuminate the human condition and provide a fresh perspective on the nature of political life.

The assumption that the thread of tradition is irrevocably broken influenced Arendt’s method : The hermeneutic strategy she employed to re-establish a link with the past is indebted to both Walter Benjamin and Martin Heidegger. From Benjamin she took the idea of a fragmentary historiography, one that seeks to identify the moments of rupture, displacement and dislocation in history. Such fragmentary historiography enables one to recover the lost potentials of the past in the hope that they may find actualization in the present. From Heidegger she took the idea of a deconstructive reading of the Western philosophical tradition, one that seeks to uncover the original meaning of our categories and to liberate them from the distorting incrustations of tradition. Such deconstructive hermeneutics enables one to recover those primordial experiences ( Urphänomene ) which have been occluded or forgotten by the philosophical tradition, and thereby to recover the lost origins of our philosophical concepts and categories.

By relying on these two hermeneutic strategies Arendt hopes to redeem from the past its lost or “forgotten treasure,” that is, those fragments from the past that might still be of significance to us. In her view it is no longer possible, after the collapse of tradition, to save the past as a whole; the task, rather, is to redeem from oblivion those elements of the past that are still able to illuminate our situation. Only by means of this critical reappropriation can we discover the past anew, endow it with relevance and meaning for the present, and make it a source of inspiration for the future. The breakdown of tradition may in fact provide the great chance to look upon the past “with eyes undistorted by any tradition, with a directness which has disappeared from Occidental reading and hearing ever since Roman civilization submitted to the authority of Greek thought” (BPF, 28–9). Arendt’s return to the original experience of the Greek polis represents, in this sense, an attempt to break the fetters of a worn-out tradition and to rediscover a past over which tradition has no longer a claim.

How can Arendt’s philosophy be classified ? Although some of Arendt’s works now belong to the classics of the Western tradition of political thought, she has always remained difficult to classify. Her political philosophy cannot be characterized in terms of the traditional categories of conservatism, liberalism, and socialism. Nor can her thinking be assimilated to the recent revival of communitarian political thought, to be found, for example, in the writings of A. MacIntyre, M. Sandel, C. Taylor and M. Walzer. Her name has been invoked by a number of critics of the liberal tradition, on the grounds that she presented a vision of politics that stood in opposition some key liberal principles. There are many strands of Arendt’s thought that could justify such a claim, in particular, her critique of representative democracy, her stress on civic engagement and political deliberation, her separation of morality from politics, and her praise of the revolutionary tradition. However, it would be a mistake to view Arendt as an anti-liberal thinker. Arendt was in fact a stern defender of constitutionalism and the rule of law, an advocate of fundamental human rights (among which she included not only the right to life, liberty, and freedom of expression, but also the right to action and to opinion), and a critic of all forms of political community based on traditional ties and customs, as well as those based on religious, ethnic, or racial identity.

Arendt’s political thought cannot, in this sense, be identified either with the liberal tradition or with the claims advanced by a number of its critics. Arendt did not conceive of politics as a means for the satisfaction of individual preferences, nor as a way to integrate individuals around a shared conception of the good. Her conception of politics is based instead on the idea of active citizenship, that is, on the value and importance of civic engagement and collective deliberation about all matters affecting the political community. If there is a tradition of thought with which Arendt can be identified, it is the classical tradition of civic republicanism originating in Aristotle and embodied in the writings of Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Jefferson, and Tocqueville. According to this tradition politics finds its authentic expression whenever citizens gather together in a public space to deliberate and decide about matters of collective concern. Political activity is valued not because it may lead to agreement or to a shared conception of the good, but because it enables each citizen to exercise his or her powers of agency, to develop the capacities for judgment and to attain by concerted action some measure of political efficacy.

In what follows, we reconstruct Arendt’s philosophy along five major themes: (1) her concept of totalitarianism, (2) her conception of modernity, (3) her theory of action, (4) her conception of citizenship, (5) her theory of thinking and judgment and how it concerns the problems of evil and autonomy.

The Origins of Totalitarianism , first published in 1951, established Hannah Arendt’s reputation as a political thinker. In it, Arendt examines the historical development and the shared political characteristics of National Socialism and Stalinism. Faced with the horrors of the extermination camps and what is now termed the Gulag, Arendt strove to understand these phenomena in their own terms, neither deducing them from precedents nor placing them in some overarching scheme of historical necessity. The work is one of the earliest standard works of totalitarianism research.

The book contains three volumes in one: Antisemitism, Imperialism, and Totalitarianism. In the first part, she traces the development of anti-Semitism in the 18th and 19th century. The second part covers the emergence of racism and imperialism in the 19th and 20th century up to National Socialism. Here she argues that imperialism prepared the ground for totalitarianism and provided the preconditions and precedents for its perpetrators (cf. Canovan 2000, 30). The third part is devoted to the two historical manifestations of total domination. In analyzing antisemitism, imperialism, and racism, Arendt did not want to provide a causal explanation for totalitarianism, but rather a historical investigation of the elements that “crystallized into totalitarianism” (Canovan 2000, 27).

What does Arendt understand by the term? Emphasizing its “horrible originality” (UP in EU, 309), Arendt understood totalitarianism to be an entirely new political phenomenon that differed “essentially from other forms of political oppression known to us such as despotism, tyranny and dictatorship” (OT, 460) and thus broke with all political and legal tradition. In the 14 chapters of the third part, Arendt analyzes the conditions and features of this “novel form of government” (OT, 460). According to her, important factors that made totalitarianism possible included collapsed political structures and masses of uprooted people who had lost their orientation and sense of reality in a world marked by socio-economic transformation, revolution and war. While the leaders of the movements belonged to the “mob” (OT, 326), their many supporters were recruited from these rootless and lonely “masses” (OT, 311) through propaganda (OT, 341): “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” (OT, 474).

Thus, totalitarianism is based on a secular, pseudo-scientific ideology that reduces the complexity of reality to the logic of one idea pretending to be able to explain everything. In its self-understanding, the movement is merely carrying out the alleged laws of nature or history outlined by the ideology. It is quintessential, however, that this “central fiction” a totalitarian system rests upon, is translated into a “functioning reality” (OT, 364) by a “completely new” form of “totalitarian organization” (OT, 364): Characteristically, the state is not a monolithic, strictly ordered system, but has a deliberately chaotic, fluid and shapeless structure with competing institutions and a “fluctuating hierarchy” (OT, 369), which makes predictability, trust and accountability impossible. Above this “maze”, however, “lies the power nucleus of the country, the superefficient and supercompetent services of the secret police” (OT, 420). Thus, the organization combines deliberate chaos with the “iron band” (OT, 466) of total control through extreme coercion and terror.

While the regime openly claims unlimited power and aims at world domination, their “real secret” (OT, 436) are the concentration and extermination camps as their “true central institution” (OT, 438). According to Arendt, the camps “serve as laboratories in which the fundamental belief of totalitarianism that everything is possible is being verified.” (OT, 437). The total terror in the camps is the “essence of totalitarian government” (OT, 466), because here total domination reaches its abysmal goal: To reduce “the infinite plurality” of human beings into one interchangeable “bundle of reactions” and thus eliminate “spontaneity itself” (OT, 438). It seemed as if the real mission of the totalitarian apparatus was to “to make men superfluous” (OT, 445). Therefore, the “hurricane of nihilism” (Canovan 2000, 30) unleashed by the totalitarian regime cannot create an new world order, but ultimately leads to nothing but unprecedented destruction: It even “bears the germ of its own destruction.” (OT, 478).

What makes totalitarianism difficult to understand is not only the gigantic scale of atrocities committed by it, but its senselessness. Arendt maintained that totalitarianism defy common sense understanding, because their crimes cannot be explained by self-interested or utilitarian motives or ends (cf. OT, 440).The camps did not serve evil, but useful purposes like forced labor or slavery, but showed that an “absolute” (OT, viii-ix) and “radical evil” is possible (OT, 443; cf. section 6).

Understanding totalitarianism despite this, is of the utmost political importance, because insight into its structures and mode of operation provides “the politically most important yardstick for judging events in our time, namely: whether they serve totalitarian domination or not.” (OT, 442)

4. The Human Condition

Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism “throws into relief […] the political condition itself.” (Canovan (2000, 35). In other words, it sheds light on the basic conditions of politics, Arendt turned to in her major philosophical work, The Human Condition . Published in 1958, the book contains her critical conception of the modern age, the tripartite division of the vita activa in labor, work and action, and thus Arendt’s political theory, which examines the basic conditions of political agency.

Arendt’s theory of action and her revival of the ancient notion of praxis represent one of the most original contributions to twentieth century political thought. By distinguishing action ( praxis ) from fabrication ( poiesis ), by linking it to freedom and plurality, and by showing its connection to speech and remembrance, Arendt is able to articulate a conception of politics in which questions of meaning and identity can be addressed in a fresh and original manner. Moreover, by viewing action as a mode of human togetherness, Arendt is able to develop a conception of participatory democracy which stands in direct contrast to the bureaucratized and elitist forms of politics so characteristic of the modern epoch.

Shaped by her experience of totalitarianism in the twentieth century, Arendt articulated a fairly negative conception of modernity in The Human Condition , and in some of the essays collected in Between Past and Future . In these writings Arendt is primarily concerned with the losses incurred as a result of the eclipse of tradition, religion, and authority, but she offers a number of illuminating suggestions with respect to the resources that the modern age can still provide to address questions of meaning, identity, and value.

For Arendt modernity is characterized by the loss of the world , by which she means the restriction or elimination of the public sphere of action and speech in favor of the private world of introspection and the private pursuit of economic interests. Modernity is the age of mass society, of the rise of the social out of a previous distinction between the public and the private, and of the victory of animal laborans over homo faber and the classical conception of man as zoon politikon . Modernity is the age of bureaucratic administration and anonymous labor, rather than politics and action, of elite domination and the manipulation of public opinion. It is the age when totalitarian forms of government, such as Nazism and Stalinism, have emerged as a result of the institutionalization of terror and violence. It is the age where history as a “natural process” has replaced history as a fabric of actions and events, where homogeneity and conformity have replaced plurality and freedom, and where isolation and loneliness have eroded human solidarity and all spontaneous forms of living together. Modernity is the age where the past no longer carries any certainty of evaluation, where individuals, having lost their traditional standards and values, must search for new grounds of human community as such.

Arendt articulates her conception of modernity around a number of key features: these are world alienation, earth alienation, the rise of the social, and the victory of animal laborans . World alienation refers to the loss of an intersubjectively constituted world of experience and action by means of which we establish our self-identity and an adequate sense of reality. Earth alienation refers to the attempt to escape from the confines of the earth; spurred by modern science and technology, we have searched for ways to overcome our earth-bound condition by setting out on the exploration of space, by attempting to recreate life under laboratory conditions, and by trying to extend our given life-span. The rise of the social refers to the expansion of the market economy from the early modern period and the ever increasing accumulation of capital and social wealth. With the rise of the social everything has become an object of production and consumption, of acquisition and exchange; moreover, its constant expansion has resulted in the blurring of the distinction between the private and the public. The victory of animal laborans refers to the triumph of the values of labor over those of homo faber and of man as zoon politikon. All the values characteristic of the world of fabrication — permanence, stability, durability — as well as those characteristic of the world of action and speech — freedom, plurality, solidarity — are sacrificed in favor of the values of life, productivity and abundance.

Arendt’s interpretation of modernity can be criticized on a number of grounds. We focus here on her assessment of the social: Arendt identifies the social with all those activities formerly restricted to the private sphere of the household and having to do with the necessities of life. Her claim is that, with the tremendous expansion of the economy from the end of the eighteenth century, all such activities have taken over the public realm and transformed it into a sphere for the satisfaction of our material needs. Society has thus invaded and conquered the public realm, turning it into a function of what previously were private needs and concerns, and has thereby destroyed the boundary separating the public and the private. Arendt also claims that with the expansion of the social realm the tripartite division of human activities has been undermined to the point of becoming meaningless. In her view, once the social realm has established its monopoly, the distinction between labor, work and action is lost, since every effort is now expended on reproducing our material conditions of existence. Obsessed with life, productivity, and consumption, we have turned into a society of laborers and jobholders who no longer appreciate the values associated with work, nor those associated with action.

From this brief account it is clear that Arendt’s concept of the social plays a crucial role in her assessment of modernity. However some have argued that this may have led her to a series of questionable judgments:

- In the first place, Arendt’s characterization of the social is overly restricted. She claims that the social is the realm of labor, of biological and material necessity, of the reproduction of our condition of existence. She also claims that the rise of the social coincides with the expansion of the economy from the end of the eighteenth century. However, having identified the social with the growth of the economy in the past two centuries, Arendt cannot characterize it in terms of a subsistence model of simple reproduction. (See Benhabib 2003, Ch. 6; Bernstein 1986, Ch. 9; Hansen 1993, Ch. 3; Parekh 1981, Ch. 8.)

- Secondly, Arendt’s identification of the social with the activities of the household is responsible for a major shortcoming in her analysis of the economy. She is, in fact, unable to acknowledge that a modern capitalist economy constitutes a structure of power with a highly asymmetric distribution of costs and rewards. By relying on the misleading analogy of the household, she maintains that all questions pertaining to the economy are pre-political, and thus ignores the crucial question of economic power and exploitation. (See Bernstein 1986, Ch. 9; Hansen 1993, Ch. 3; Parekh 1981, Ch. 8; Pitkin 1998; Pitkin 1994, Ch. 10, Hinchman and Hinchman; Wolin 1994, Ch. 11, Hinchman and Hinchman.)

- Finally, by insisting on a strict separation between the private and the public, and between the social and the political, she is unable to account for the essential connection between these spheres and the struggles to redraw their boundaries. Today many so-called private issues have become public concerns, and the struggle for justice and equal rights has extended into many spheres. By insulating the political sphere from the concerns of the social, and by maintaining a strict distinction between the public and the private, Arendt is unable to account for some of the most important achievements of modernity — the extension of justice and equal rights, and the redrawing of the boundaries between the public and the private. (See Benhabib 2003, Ch. 6; Bernstein 1986, Ch. 9; Dietz 2002, Ch. 5; Pitkin 1998; Pitkin 1995, Ch. 3, Honig; Zaretsky 1997, Ch. 8, Calhoun and McGowan.)

Arendt analyzes the vita activa via three categories which correspond to the three fundamental activities of our being-in-the-world: labor, work, and action. Labor is the activity which is tied to the human condition of life, work the activity which is tied to the condition of worldliness, and action the activity tied to the condition of plurality. For Arendt each activity is autonomous, in the sense of having its own distinctive principles and of being judged by different criteria. Labor is judged by its ability to sustain human life, to cater to our biological needs of consumption and reproduction, work is judged by its ability to build and maintain a world fit for human use, and action is judged by its ability to disclose the identity of the agent, to affirm the reality of the world, and to actualize our capacity for freedom. Although Arendt considers the three activities of labor, work and action equally necessary to a complete human life, in the sense that each contributes in its distinctive way to the realization of our human capacities, it is clear from her writings that she takes action to be the differentia specifica of human beings, that which distinguishes them from both the life of animals (who are similar to us insofar as they need to labor to sustain and reproduce themselves) and the life of the gods (with whom we share, intermittently, the activity of contemplation). In this respect the categories of labor and work, while significant in themselves, must be seen as counterpoints to the category of action, helping to differentiate and highlight the place of action within the order of the vita activa .

In The Human Condition Arendt stresses repeatedly that action is primarily symbolic in character and that the web of human relationships is sustained by communicative interaction (HC, 178–9, 184–6, 199–200). Thus, action entails speech: by means of language we are able to articulate the meaning of our actions and to coordinate the actions of a plurality of agents. Conversely, speech entails action, not only in the sense that speech itself is a form of action, or that most acts are performed in the manner of speech, but in the sense that action is often the means whereby we check the sincerity of the speaker. Thus, just as action without speech runs the risk of being meaningless and would be impossible to coordinate with the actions of others, so speech without action would lack one of the means by which we may confirm the veracity of the speaker. As we shall see, this link between action and speech is central to Arendt’s characterization of power, that potential which springs up between people when they act “in concert,” and which is actualized “only where word and deed have not parted company, where words are not empty and deeds not brutal, where words are not used to veil intentions but to disclose realities, and deeds are not used to violate and destroy but to establish relations and create new realities ” (HC, 200).

For Arendt, action constitutes the highest realization of the vita activa . In the opening section of the chapter on action in The Human Condition Arendt discusses one of its central functions, namely, the disclosure of the identity of the agent. In action and speech, she maintains, individuals reveal themselves as the unique individuals they are, disclose to the world their distinct personalities. In terms of Arendt’s distinction, they reveal “who” they are as distinct to “what” they are — the latter referring to individual abilities and talents, as well as deficiencies and shortcomings, which are traits all human beings share. Neither labor nor work enable individuals to disclose their identities, to reveal “who” they are as distinct from “what” they are. In labor the individuality of each person is submerged by being bound to a chain of natural necessities, to the constraints imposed by biological survival. When we engage in labor we can only show our sameness, the fact that we all belong to the human species and must attend to the needs of our bodies. In this sphere we do indeed “behave,” “perform roles,” and “fulfill functions,” since we all obey the same imperatives. In work there is more scope for individuality, in that each work of art or production bears the mark of its maker; but the maker is still subordinate to the end product, both in the sense of being guided by a model, and in the sense that the product will generally outlast the maker. Moreover, the end product reveals little about the maker except the fact that he or she was able to make it. It does not tell us who the creator was, only that he or she had certain abilities and talents. It is thus only in action and speech, in interacting with others through words and deeds, that individuals reveal who they personally are and can affirm their unique identities. Action and speech are in this sense very closely related because both contain the answer to the question asked of every newcomer: “Who are you?” This disclosure of the “who” is made possible by both deeds and words, but of the two it is speech that has the closest affinity to revelation. Without the accompaniment of speech, action would lose its revelatory quality and could no longer be identified with an agent. It would lack, as it were, the conditions of ascription of agency.

The two central features of action are freedom and plurality . By freedom Arendt does not mean the ability to choose among a set of possible alternatives, but spontaneity, i.e. the capacity to begin, to start something new, to do the unexpected, with which all human beings are endowed by virtue of being born. Action as the realization of freedom is therefore rooted in natality , in the fact that each birth represents a new beginning and the introduction of novelty in the world. “It is in the nature of beginning” — she claims — “that something new is started which cannot be expected from whatever may have happened before. This character of startling unexpectedness is inherent in all beginnings … The fact that man is capable of action means that the unexpected can be expected from him, that he is able to perform what is infinitely improbable. And this again is possible only because each man is unique, so that with each birth something uniquely new comes into the world ” (HC, 177–8). To act means to be able to do the unanticipated; and it is entirely in keeping with this conception that most of the concrete examples of action in the modern age that Arendt discusses are cases of revolutions and popular uprisings. Her claim is that “revolutions are the only political events which confront us directly and inevitably with the problem of beginning,” (OR, 21) since they represent the attempt to found a new political space, a space where freedom can appear as a worldly reality. The favorite example for Arendt is the American Revolution, because there the act of foundation took the form of a constitution of liberty. Her other examples are the revolutionary clubs of the French Revolution, the Paris Commune of 1871, the creation of Soviets during the Russian Revolution, the French Resistance to Hitler in the Second World War, and the Hungarian revolt of 1956. In all these cases individual men and women had the courage to interrupt their routine activities, to step forward from their private lives in order to create a public space where freedom could appear, and to act in such a way that the memory of their deeds could become a source of inspiration for the future.

Plurality , to which we may now turn, is the other central feature of action. For Arendt, plurality is the necessary condition of all political life (HC, 7). For if to act means to take the initiative, to introduce the novum and the unexpected into the world, it also means that it is not something that can be done in isolation from others, that is, independently of the presence of a plurality of actors who from their different perspectives can judge the quality of what is being enacted. In this respect action needs plurality in the same way that performance artists need an audience; without the presence and acknowledgment of others, action would cease to be a meaningful activity. Action, to the extent that it requires appearing in public, making oneself known through words and deeds, and eliciting the consent of others, can only exist in a context defined by plurality.

Arendt establishes the connection between action and plurality by means of an anthropological argument. In her view just as life is the condition that corresponds to the activity of labor and worldliness the condition that corresponds to the activity of work, so plurality is the condition that corresponds to action. She defines plurality as “the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world,” and says that it is the condition of human action “because we are all the same, that is, human, in such a way that nobody is ever the same as anyone else who ever lived, lives, or will live ” (HC, 7–8). Plurality thus refers both to equality and distinction, to the fact that all human beings belong to the same species and are sufficiently alike to understand one another, but yet no two of them are ever interchangeable, since each of them is an individual endowed with a unique biography and perspective on the world. It is by virtue of plurality that each of us is capable of acting and relating to others in ways that are unique and distinctive, and in so doing of contributing to a network of actions and relationships that is infinitely complex and unpredictable.

One of the principal drawbacks of action, Arendt maintains, is to be extremely fragile, to be subject to the erosion of time and to forgetfulness; unlike the products of the activity of work, which acquire a measure of permanence by virtue of their sheer facticity, deeds and words do not survive their enactment unless they are remembered. Remembrance alone, the retelling of deeds as stories, can save the lives and deeds of actors from oblivion and futility. And it is precisely for this reason, Arendt points out, that the Greeks valued poetry and history so highly, because they rescued the glorious (as well as the less glorious) deeds of the past for the benefit of future generations (HC, 192 ff; BPF, 63–75). Through their narratives the fragility and perishability of human action was overcome and made to outlast the lives of their doers and the limited life-span of their contemporaries. They preserve the memory of deeds through time, and in so doing, they enable these deeds to become sources of inspiration for the future, that is, models to be imitated, and, if possible, surpassed.

The function of the storyteller is thus crucial not only for the preservation of the doings and sayings of actors, but also for the full disclosure of the identity of the actor. The narratives of a storyteller, Arendt claims, “tell us more about their subjects, the ‘hero’ in the center of each story, than any product of human hands ever tells us about the master who produced it” (HC, 184). Indeed, it is one of Arendt’s most important claims that the meaning of action itself is dependent upon the articulation retrospectively given to it by historians and narrators. Narratives can thus provide a measure of truthfulness and a greater degree of significance to the actions of individuals.

However, to be preserved, such narratives needed in turn an audience, that is, a community of hearers who became the transmitters of the deeds that had been immortalized. As Sheldon Wolin has aptly put it, “audience is a metaphor for the political community whose nature is to be a community of remembrance” (Wolin 1977, 97). In other words, behind the actor stands the storyteller, but behind the storyteller stands a community of memory . It was one of the primary functions of the Greek polis to be precisely such a community, to preserve the words and deeds of its citizens from oblivion and the ravages of time, and thereby to leave a testament for future generations.

For Arendt the polis stands for the space of appearance , for that space “where I appear to others as others appear to me, where men exist not merely like other living or inanimate things, but to make their appearance explicitly.” Such public space of appearance can be always recreated anew wherever individuals gather together politically, that is, “wherever men are together in the manner of speech and action” (HC, 198–9). However, since it is a creation of action, this space of appearance is highly fragile and exists only when actualized through the performance of deeds or the utterance of words. The space of appearance must be continually recreated by action; its existence is secured whenever actors gather together for the purpose of discussing and deliberating about matters of public concern, and it disappears the moment these activities cease. It is always a potential space that finds its actualization in the actions and speeches of individuals who have come together to undertake some common project. It may arise suddenly, as in the case of revolutions, or it may develop slowly out of the efforts to change some specific piece of legislation or policy. Historically, it has been recreated whenever public spaces of action and deliberation have been set up, from town hall meetings to workers’ councils, from demonstrations and sit-ins to struggles for justice and equal rights.

The capacity to act in concert for a public-political purpose is what Arendt calls power. Power needs to be distinguished from strength, force, and violence (CR, 143–55). Unlike strength, it is not the property of an individual, but of a plurality of actors joining together for some common political purpose. Unlike force, it is not a natural phenomenon but a human creation, the outcome of collective engagement. And unlike violence, it is based not on coercion but on consent and rational persuasion.

For Arendt, power is a sui generis phenomenon, since it is a product of action and rests entirely on persuasion. It is a product of action because it arises out of the concerted activities of a plurality of agents, and it rests on persuasion because it consists in the ability to secure the consent of others through unconstrained discussion and debate. Its only limitation is the existence of other people, but this limitation, she notes, “is not accidental, because human power corresponds to the condition of plurality to begin with” (HC, 201). It is actualized in all those cases where action is undertaken for communicative (rather than strategic or instrumental) purposes, and where speech is employed to disclose our intentions and to articulate our motives to others.

Arendt maintains that the legitimacy of power is derived from the initial getting together of people, that is, from the original pact of association that establishes a political community, and is reaffirmed whenever individuals act in concert through the medium of speech and persuasion. For her “power needs no justification, being inherent in the very existence of political communities; what it does need is legitimacy … Power springs up whenever people get together and act in concert, but it derives its legitimacy from the initial getting together rather than from any action that then may follow” (CR, 151).

Beyond appealing to the past, power also relies for its continued legitimacy on the rationally binding commitments that arise out of a process of free and undistorted communication. Because of this, power is highly independent of material factors: it is sustained not by economic, bureaucratic or military means, but by the power of common convictions that result from a process of fair and unconstrained deliberation.

Power is also not something that can be relied upon at all times or accumulated and stored for future use. Rather, it exists only as a potential which is actualized when actors gather together for political action and public deliberation. It is thus closely connected to the space of appearance, that public space which arises out of the actions and speeches of individuals. Indeed, for Arendt, “power is what keeps the public realm, the potential space of appearance between acting and speaking men, in existence.” (HC, 200).

Power, then, lies at the basis of every political community and is the expression of a potential that is always available to actors. It is also the source of legitimacy of political and governmental institutions, the means whereby they are transformed and adapted to new circumstances and made to respond to the opinions and needs of the citizens. “It is the people’s support that lends power to the institutions of a country, and this support is but the continuation of the consent that brought the laws into existence to begin with … All political institutions are manifestations and materializations of power; they petrify and decay as soon as the living power of the people ceases to uphold them” (CR, 140).

The legitimacy of political institutions is dependent on the power, that is, the active consent of the people; and insofar as governments may be viewed as attempts to preserve power for future generations by institutionalizing it, they require for their vitality the continuing support and active involvement of all citizens.

In this section, we examine the unpredictability and irreversibility of action, and their respective remedies, the power of promise and the power to forgive . Action is unpredictable because it is a manifestation of freedom, of the capacity to innovate and to alter situations by engaging in them; but also, and primarily, because it takes place within the web of human relationships, within a context defined by plurality, so that no actor can control its final outcome. Each actor sets off processes and enters into the inextricable web of actions and events to which all other actors also contribute, with the result that the outcome can never be predicted from the intentions of any particular actor. The open and unpredictable nature of action is a consequence of human freedom and plurality: by acting we are free to start processes and bring about new events, but no actor has the power to control the consequences of his or her deeds.

Another and related reason for the unpredictability of action is that its consequences are boundless: every act sets in motion an unlimited number of actions and reactions which have literally no end. As Arendt puts it: “The reason why we are never able to foretell with certainty the outcome and end of any action is simply that action has no end” (HC, 233). This is because action “though it may proceed from nowhere, so to speak, acts into a medium where every action becomes a chain reaction and where every process is the cause of new processes … the smallest act in the most limited circumstances bears the seed of the same boundlessness, because one deed, and sometimes one word, suffices to change every constellation” (HC, 190).

Closely connected to the boundlessness and unpredictability of action is its irreversibility. Every action sets off processes which cannot be undone or retrieved in the way, say, we are able to undo a faulty product of our hands. If one builds an artifact and is not satisfied with it, it can always be destroyed and recreated again. This is impossible where action is concerned, because action always takes place within an already existing web of human relationships, where every action becomes a reaction, every deed a source of future deeds, and none of these can be stopped or subsequently undone. The consequences of each act are thus not only unpredictable but also irreversible; the processes started by action can neither be controlled nor be reversed.

The remedy which the tradition of Western thought has proposed for the unpredictability and irreversibility of action has consisted in abstaining from action altogether, in the withdrawal from the sphere of interaction with others, in the hope that one’s freedom and integrity could thereby be preserved. Platonism, Stoicism and Christianity elevated the sphere of contemplation above the sphere of action, precisely because in the former one could be free from the entanglements and frustrations of action. Arendt’s proposal, by contrast, is not to turn one’s back on the realm of human affairs, but to rely on two faculties inherent in action itself, the faculty of forgiving and the faculty of promising . These two faculties are closely connected, the former mitigating the irreversibility of action by absolving the actor from the unintended consequences of his or her deeds, the latter moderating the uncertainty of its outcome by binding actors to certain courses of action and thereby setting some limit to the unpredictability of the future. Both faculties are, in this respect, connected to temporality: from the standpoint of the present forgiving looks backward to what has happened and absolves the actor from what was unintentionally done, while promising looks forward as it seeks to establish islands of security in an otherwise uncertain and unpredictable future. Forgiving enables us to come to terms with the past and liberates us to some extent from the burden of irreversibility; promising allows us to face the future and to set some bounds to its unpredictability (HC, 237). Both faculties, in this sense, depend on plurality , on the presence and acting of others, for no one can forgive himself and no one can feel bound by a promise made only to one’s self. At the same time, both faculties are an expression of human freedom , since without the faculty to undo what we have done in the past, and without the ability to control at least partially the processes we have started, we would be the victims “of an automatic necessity bearing all the marks of inexorable laws” (HC, 246).

5. Arendt’s Conception of Citizenship

In this section, we reconstruct Arendt’s conception of citizenship around two themes: (1) the public sphere, and (2) political agency and collective identity, and to highlight the contribution of Arendt’s conception to a theory of democratic citizenship.

For Arendt the public sphere comprises two distinct but interrelated dimensions. The first is the space of appearance , a space of political freedom and equality which comes into being whenever citizens act in concert through the medium of speech and persuasion. The second is the common world , a shared and public world of human artifacts, institutions and settings which separates us from nature and which provides a relatively permanent and durable context for our activities. Both dimensions are essential to the practice of citizenship, the former providing the spaces where it can flourish, the latter providing the stable background from which public spaces of action and deliberation can arise. For Arendt the reactivation of citizenship in the modern world depends upon both the recovery of a common, shared world and the creation of numerous spaces of appearance in which individuals can disclose their identities and establish relations of reciprocity and solidarity.

There are three features of the public sphere and of the sphere of politics in general that are central to Arendt’s conception of citizenship. These are, first, its artificial or constructed quality; second, its spatial quality; and, third, the distinction between public and private interests.

As regards the first feature, Arendt always stressed the artificiality of public life and of political activities in general, the fact that they are man-made and constructed rather than natural or given. She regarded this artificiality as something to be celebrated rather than deplored. Politics for her was not the result of some natural predisposition, or the realization of the inherent traits of human nature. Rather, it was a cultural achievement of the first order, enabling individuals to transcend the necessities of life and to fashion a world within which free political action and discourse could flourish.

The stress on the artificiality of politics has a number of important consequences. For example, Arendt emphasized that the principle of political equality does not rest on a theory of natural rights or on some natural condition that precedes the constitution of the political realm. Rather, it is an attribute of citizenship which individuals acquire upon entering the public realm and which can be secured only by democratic political institutions.

Another consequence of Arendt’s stress on the artificiality of political life is evident in her rejection of all neo-romantic appeals to the volk and to ethnic identity as the basis for political community. She maintained that one’s ethnic, religious, or racial identity was irrelevant to one’s identity as a citizen, and that it should never be made the basis of membership in a political community.