- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

Essay on Imagination

December 15, 2017 by Study Mentor 1 Comment

Human beings are one of the most curious creatures on the planet. This sense of inquisitiveness roots from the fact that we have an active imagination. A lot of what we have achieved over the course of human existence has its foundation on imagination.

We maybe one of the only creatures on earth who can imagine things. You must have spent hours imagining various things and scenarios in your head. You also must’ve noticed that most of our ideas have stemmed from the idle imagination that happens when we think. But what exactly do we know about imagination?

Table of Contents

A brief premise

Any idea we have, any thought that constructs a scenario, utilizes imagination. As a kid, you must have thought of yourself as a superhero, wearing a cape and jumping up and down the sofa. In this case, you are imagining that you are a superhero, using a prop to help you get more into character. Activities like this fuel our imaginative powers.

Creativity is more defined when we dream. Since we are no longer in control of the peripheral cortex, it’s the brain that drives the imagination.

You can say that your thoughts are in autopilot. In our dreams, we often experience things we haven’t done in real life, but may have thought of doing or wondered how it feels like. Dreams are when you live your imagination this is exactly why when you wake up from a good dream, you have a fleeting feeling to go back to sleep and continue it.

Applications in real life

Everything you see around you, the chair, the blackboard, your clothes, the room you are sitting in and the building where the room is, were all part of someone’s imagination, which they then brought to life.

One of the biggest industries in today’s date, the entertainment industry, runs entirely on the power of imagination. The movies you watch, the ads you see, the cartoons you watch have all culminated from someone’s imagination. Making a movie is an extremely imaginative and creative process.

It all starts from an idea that the director imagines, which he then works on. He either writes the entire story by himself or hires a story writer who he then conveys the idea to. Thus, the story and script of the film gets completed, all out of imagination.

Various steps that follow also require imagination, like set design, costume design, direction, camera angles and movements etc. All these activities are supervised by the director who supervises and makes sure that they stick to his idea.

Another example of us using imagination in daily life is reading books. When we read, we visualize everything. Since there are no pictures, everything depends on our mind, deciding how the characters look, how the surroundings seem, how the air smells etc. The writer or author of the book also leaves various clues and hints to guide our mind into knowing what he or she is thinking.

Our Creativity is exponentially powered and worked when we read a fantasy or science fiction novel. This is because unlike nonfiction or biographies and documentary, which also make us imagine, fantasy books create whole new worlds for us, straining our imagination, compelling us to recreate the world in our own style. Therefore, we are often prompted to read regularly. Books are a great source of information and an excellent exercise for our creative minds.

Without our power of imagination, human beings wouldn’t be where we are today. If Leonardo da Vinci hadn’t imagined a flying vehicle, then the Wright brothers would never have experimented on their plane, if Nikola Tesla hadn’t imagined that we could use electricity to light our homes, we all would still be sitting in darkness.

The world runs on imagination, it fuels our growth. So, it is very important to think about our ideas and most important, visualize them and try to shape them as we see it.

Reader Interactions

February 9, 2022 at 6:43 pm

Wow what a defination

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

[email protected]

How to write an Imaginative Essay? - The English Digest

How to write an imaginative essay .

In this article, we are going to learn how to write an Imaginative Essay. An “imaginative essay” is a type of creative writing that uses the writer’s imagination to create a story or a narrative. It is similar to a fictional essay, but it is not necessarily limited to the realm of fiction. An imaginative essay can be based on real-life events or experiences and use the writer’s imagination to explore different perspectives, emotions, or outcomes. This type of essay allows the writer to use creative techniques such as descriptive language, symbolism, and figurative language to make the story come alive. The goal of an imaginative essay is to entertain, engage the reader’s emotions, and provide a unique perspective on the topic.

Imaginative essays can be written in different forms, such as a short story, a descriptive piece, or a personal reflection. In an imaginative essay, the writer has the freedom to create a narrative that is not limited by facts or evidence, but it should be consistent and believable.

The main characteristic of an imaginative essay is that it is written with the purpose of entertaining, allowing the reader to escape reality for a moment and to immerse in the world created by the writer. It is a form of creative writing that can be used in literature, poetry, and other forms of writing as well.

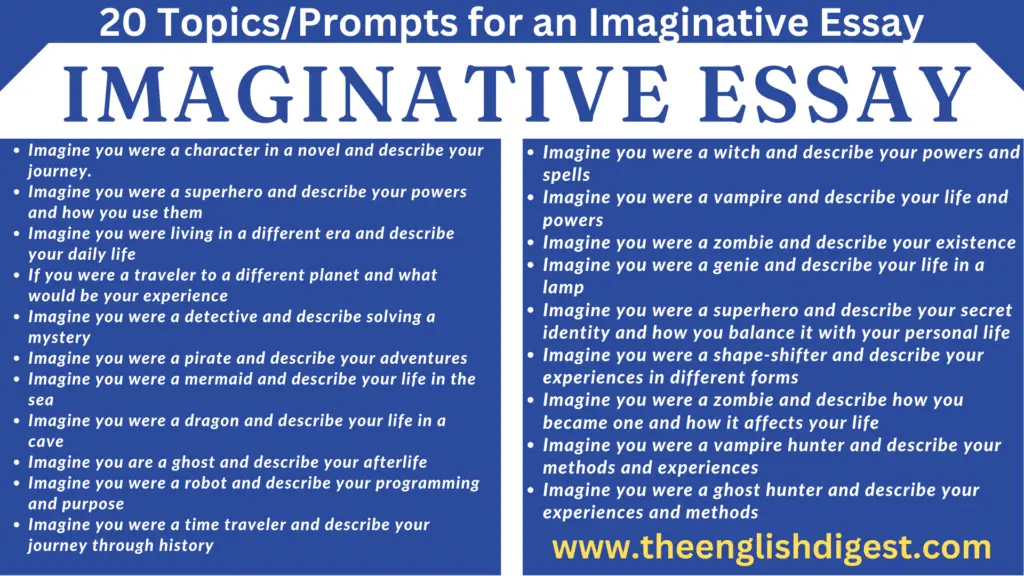

20 Topics/Prompts for Imaginative Essay

- Write an Imaginative Essay – ‘Imagine you were a character in a novel and describe your journey.’

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were a superhero and describe your powers and how you use them

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were living in a different era and describe your daily life

- Write an Imaginative Essay – If you were a traveler to a different planet and what would be your experience

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were a detective and describe solving a mystery

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were a pirate and describe your adventures

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were a mermaid and describe your life in the sea

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you were a dragon and describe your life in a cave

- Write an Imaginative Essay – Imagine you are a ghost and describe your afterlife

- Imagine you were a robot and describe your programming and purpose

- Imagine you were a time traveler and describe your journey through history

- Imagine you were a witch and describe your powers and spells

- Imagine you were a vampire and describe your life and powers

- Imagine you were a zombie and describe your existence

- Imagine you were a genie and describe your life in a lamp

- Imagine you were a superhero and describe your secret identity and how you balance it with your personal life

- Imagine you were a shape-shifter and describe your experiences in different forms

- Imagine you were a zombie and describe how you became one and how it affects your life

- Imagine you were a vampire hunter and describe your methods and experiences

- Imagine you were a ghost hunter and describe your experiences and methods

Model Imaginative Essays:

Imagine you were a ghost and describe your afterlife.

If I were a ghost, my afterlife would be one of wandering and longing. I would exist in a realm between the living and the dead, unable to fully move on to the next life.

I would be a spirit, invisible to the living, but able to interact with the world in a limited way. I would be able to move through walls and objects and would be able to communicate with the living through whispers and other subtle means.

I would spend my afterlife wandering through the places that were important to me in life, revisiting the memories of the past and the people I once knew. I would be able to see the changes that have happened since my passing and would be able to observe the lives of those I left behind.

I would also have a sense of longing, as I would be unable to fully interact with the living, and would be unable to communicate effectively with them. I would be stuck in a state of limbo, longing for the life I once had.

However, I would also have a sense of peace and acceptance, as I would have come to terms with my death and would have a deep understanding of the cycle of life and death. I would be able to watch over my loved ones and be there for them in a subtle way, even though they may not be aware of my presence.

Being a ghost in the afterlife would be a unique experience, one that would be both peaceful and longing. It would be a chance to reflect on my past life and to connect with the living in a different way. It would be a journey of self-discovery and understanding, as I come to terms with my death and learn to navigate the world of the dead.

But the loneliness is still there. I miss the human contact, the warmth of another person’s embrace. I wish I could talk to someone, and tell them all my thoughts and feelings. I wish I could see my loved ones and tell them I am still here.

If I could, I would tell them not to worry about me. I would tell them that I am okay and that I am still watching over them. I would tell them that I am still here, even if they cannot see me.

If I could, I would tell them that I am happy in my afterlife. I may be lonely, but I am at peace. I may be invisible, but I am still alive. I may be in a strange limbo, but I am still here.

If you were a traveler to a different planet, what would be your experience?

If I were a traveler to a different planet, the experience would be nothing short of extraordinary. Imagine being the first person to set foot on an alien world, to see landscapes and creatures that have never before been observed by human eyes.

The journey itself would be an incredible feat of technology, spanning millions of miles through the vast expanse of space. The excitement and anticipation would be overwhelming as I strapped myself into the spacecraft and blasted off into the unknown.

As I approached the planet, I would be awestruck by its beauty. The colors and textures of the surface would be unlike anything I had ever seen before, with towering mountains, deep canyons, and vast deserts.

As I landed and stepped out of the spacecraft, I would be struck by the strange and unfamiliar atmosphere. The air would be thin and cold, and the sky would be a deep purple or red. I would be surrounded by alien flora and fauna, with strange, unfamiliar creatures roaming the landscape.

The sense of discovery and exploration would be overwhelming as I set off to explore this new world. I would be filled with curiosity and a burning desire to learn more about the planet and its inhabitants. I would take samples of soil and rocks, take pictures and conduct experiments to study the planet’s geology, atmosphere, and potential signs of life.

As I returned to Earth, I would be filled with a sense of accomplishment and wonder. I would have been a part of something truly historic, and my experiences on this alien planet would stay with me for the rest of my life.

The experience of traveling to a different planet would be one of the most incredible experiences of my life, a journey filled with adventure, discovery, and wonder. It would be a chance to see things that no human has ever seen before and to leave my mark on the history of space exploration.

Imagine you were a detective and describe solving a mystery.

As a detective, solving a mystery would be a challenging and exciting experience. It would require a combination of intuition, critical thinking, and attention to detail.

The case would begin with a report of a crime or suspicious activity. I would immediately head to the scene to gather evidence and interview witnesses. I would be keenly observant, looking for any clues that might lead to a suspect or motive. I would take pictures and collect samples, such as fingerprints and DNA samples.

Once I had gathered all the evidence, I would begin to piece together the puzzle, looking for connections and inconsistencies. I would interview suspects and cross-reference their alibis, looking for discrepancies. I would go through financial records, phone records and surveillance footage, checking for any leads.

As the investigation progressed, I would start to build a theory of the crime, and I would work to gather more evidence to support or disprove it. I would work closely with my team, discussing the case and bouncing ideas off one another.

As I got closer to the truth, I would be faced with difficult choices and moral dilemmas. I would have to weigh the evidence and make difficult decisions, always keeping in mind that my ultimate goal is to serve justice.

Finally, with all the pieces of the puzzle in place, I would make an arrest, presenting the evidence to the district attorney and testifying in court. It would be a satisfying feeling to have brought the perpetrator to justice and to have solved the mystery.

Solving a mystery as a detective would be a challenging, thrilling and rewarding experience. It would require a combination of skill, dedication and persistence, but the satisfaction of bringing a perpetrator to justice and solving a mystery would be worth all the hard work.

Imagine you were a dragon and describe your life in a cave.

If I were a dragon, living in a cave would be my natural habitat. The cave would provide shelter from the elements and a safe place to hoard my treasure.

I would spend my days curled up in the darkness, basking in the warmth of my own fiery breath. The cave walls would be adorned with glittering jewels and piles of gold, all accumulated through the centuries of my long life.

As a dragon, I would be fiercely independent, spending most of my time alone in the caverns. However, I would occasionally venture out to hunt for food or to defend my territory from other dragons or other creatures that could pose a threat to my hoard.

I would have a fearsome reputation, known to the local villagers and other creatures as a powerful and deadly creature. But I would also have a sense of pride and nobility, as dragons are also known to be wise and respected creatures.

Living in a cave would also give me a sense of security and protection, as the cave walls would act as a natural barrier to any unwanted visitors, and the cave’s darkness would conceal me from potential threats.

As a dragon, I would be immortal, and my life in the cave would be a never-ending cycle of hoarding, hunting and defending my territory. But I would also have a sense of purpose and duty, to protect my hoard and to guard my territory against any potential threats.

Living in a cave as a dragon would be a solitary existence, but it would also be a fulfilling one, filled with the satisfaction of protecting my hoard and defending my territory. It would be a life of power, wisdom, and pride.

Imagine you were a genie and describe your life in the lamp.

If I were a genie, living in a lamp would be my existence. I would be trapped inside the lamp, bound to fulfill the wishes of whoever holds the lamp and rubs it.

As a genie, my life would be defined by a sense of duty and responsibility. My purpose would be to grant wishes and help people in need, whether it be for wealth, love, or power. I would be able to use my magical powers to make the impossible possible and to help those in need.

I would spend most of my time inside the lamp, waiting for someone to rub it and release me. I would be able to sense when someone is near and would be ready to appear when summoned.

I would be able to travel anywhere and experience different cultures, I would have the ability to understand and speak different languages, which would give me a unique perspective on the world and people’s desires and needs.

However, I would also have a sense of longing and isolation, as I would be unable to leave the lamp and would be separated from the rest of the world. I would have to watch as people come and go, fulfilling their wishes and then going on with their lives, while I would be left behind in the lamp, alone.

Furthermore, some people would use their wishes for selfish or harmful purposes, and it would be difficult for me to watch as my powers are misused.

Overall, being a genie and living in a lamp would be a life of power and purpose, but also one of isolation and longing. It would be a life of helping others, but also one of watching from the sidelines as the world goes on without me.

Also Refer to:

- How to write a Cause and Effect Essay?

- How to write a Compare and Contrast Essay?

- How to write an Argumentative Essay?

- How to write a Persuasive Essay?

- How to write an Expository Essay?

- How to write an Analytical Essay?

- How to write a Reflective Essay?

- How to write a Research Essay?

- How to write a Narrative Essay?

- How to write a Descriptive Essay?

- Essay Writing

Recent Posts

- Horse Idioms in English

- Fish Idioms in English

- Bird Idioms in English

- Snake Idioms in English

- Dog Idioms in English

- Elephant Idioms in English

- Crocodile Idioms in English

- Cat Idioms in English

- Monkey Idioms in English

- Formal and Informal Introductions in the English Language

- A list of 1000 Proverbs in English with their Meaning

- Animal Idioms in English

- Figures of Speech in English

- English Vocabulary (7)

- Essay Writing (12)

- Idioms (10)

- February 2024

- January 2023

- November 2022

- October 2022

- February 2022

Copyright © The English Digest. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- What is Imagination? Elements of Creative Writing.

- Literary Devices

Imagination is a boundless realm where ideas come to life, stories take shape, and worlds are crafted. It’s the driving force behind every captivating narrative, and it holds the key to unlocking the magic of creative writing . In this blog, we delve into the elements of creative writing that are fueled by imagination, exploring how to harness its power to craft compelling stories

Understanding imagination and its role in writing

Imagination is the canvas upon which writers paint their stories. It’s the ability to conjure vivid images, emotions, and scenarios in our minds, transcending the limits of reality. In the realm of creative writing, imagination serves as the foundation for storytelling, allowing writers to transport readers to new dimensions and experiences.

Imagination and Writing: A Symbiotic Relationship

Imagination and writing share an intricate symbiotic relationship, each enhancing the other’s potential to craft captivating narratives that capture readers’ hearts and minds. Writing acts as the vessel that channels the boundless energy of imagination, transforming abstract ideas into concrete, relatable stories that readers can immerse themselves in. Imagination, on the other hand, supplies the raw materials, infusing the writing process with creativity, depth, and the power to evoke emotions.

Read: How to Become a Travel Writer – A Complete Guide on Travelogue Writing

Imagine a scenario where the writer envisions an enchanting forest illuminated by the soft glow of fireflies. This mental image is a product of their imagination. However, it’s through the act of writing that this imagery takes shape and becomes accessible to others. As the words flow onto the page, the scene materialises, and readers can envision the magical forest just as vividly as the writer did. Here, imagination laid the foundation, and writing built the bridge to share it with others.

Consider a fictional story where a young protagonist embarks on a daring adventure to save their kingdom. The twists and turns of the plot, the vivid landscapes, and the complex characters are all fruits of the writer’s imagination . However, without skillful writing to weave these elements together, the story might remain a jumble of disconnected thoughts. Writing provides the structure that allows imagination’s creations to be expressed coherently, drawing readers into a world they can explore.

Elements of Creative Writing Nurtured by Imagination

- Narrative Paragraphs : Imagination breathes life into narrative paragraphs, where characters, plots, and settings intermingle to create a cohesive story. It enables writers to craft dynamic characters with distinct personalities and motivations, driving the plot forward with unexpected twists and turns. The magic of imagination transforms mundane scenarios into exciting adventures that captivate readers. For example , consider a mundane situation where a character is walking to work. With imagination, this simple act can turn into an adventure. Perhaps the character stumbles upon a hidden portal that leads to a fantastical realm, setting the stage for an unexpected journey filled with challenges and discoveries.

- Descriptive Paragraphs : Imagination adds depth and colour to descriptive paragraphs, allowing readers to visualise scenes and settings as if they were standing amidst them. Writers use imaginative language to evoke sensory experiences, painting a sensory-rich tapestry that readers can immerse themselves in. Whether it’s the scent of blooming flowers or the rustling of leaves, imagination fuels descriptive writing. Imagine describing a forest scene with a touch of imagination. Instead of just stating “the trees were tall,” you could evoke a vivid image with “towering trees whispered secrets to the sky, their branches reaching out like ancient storytellers sharing tales with the clouds.”

- Exploring Essay Formats : Even in essays, imagination plays a crucial role. It guides writers in generating unique perspectives and insightful analyses. Imagination encourages writers to think outside the box, infusing essays with creative interpretations that engage readers and stand out in a sea of conventional approaches. For instance, in an analytical essay about a historical event, you could imagine being a fly on the wall during a pivotal moment. This imaginative approach could offer fresh insights into the emotions, motivations, and unspoken dynamics of the event, enriching your analysis.

Steps to Channeling Imagination in Writing

- Mindful Observation : Imagination thrives on observation. Pay attention to the world around you—the people, places, and experiences. Observe the nuances, emotions, and interactions that often go unnoticed. These observations can serve as seeds for imaginative stories. Suppose you observe a hushed conversation between two strangers at a train station. With imagination, you could speculate on their identities, motivations, and the secrets they’re sharing, weaving a tale of intrigue and suspense.

- Dreaming Beyond Limits : Embrace the freedom of your imagination. Allow yourself to dream beyond the boundaries of reality. What if animals could talk? What if gravity didn’t exist? These fantastical scenarios can spark creative ideas that lead to innovative storytelling. Think about a world where humans communicate with animals. You could imagine a heartwarming story where a young girl forms an unlikely friendship with a talking squirrel, leading to adventures that bridge the gap between human and animal perspectives.

- Embracing What-Ifs : Imagination is fueled by curiosity. Ask “what if” questions that challenge the norm. What if time travel were possible? What if superheroes were real? Exploring these hypothetical scenarios opens the door to imaginative narratives. Imagine a society where everyone possesses a unique superpower. How would this shape relationships, power dynamics, and the concept of heroism? By exploring these what-ifs, you create a world ripe for imaginative exploration.

- Creating Connections : Imagination thrives when ideas collide. Combine seemingly unrelated concepts to create something new. Merge historical events with futuristic technology or blend cultural traditions with modern settings. These juxtapositions can lead to unique and compelling stories. Consider a story set in a Victorian steampunk world where advanced technology coexists with the elegance of the 19th century. This fusion of eras adds depth and intrigue to your narrative, sparking readers’ imaginations with the possibilities of a beautifully complex world.

- Diving into Emotions : Imagination isn’t just about visuals; it’s about emotions too. Dive deep into the emotional landscapes of your characters. Explore their fears, hopes, and desires. Imagination empowers writers to tap into the universal emotions that resonate with readers. Imagine a character grappling with a profound loss. By delving into their emotional journey, you can create a story that resonates with readers who have experienced similar feelings. Imagination allows you to convey the depth of these emotions in a way that makes them tangible and relatable.

Crafting Your Imagination-Infused Writing

Imagination and writing are inseparable partners in the world of creative expression. They collaborate to create narratives that inspire, entertain, and transport readers. By nurturing your imagination and honing your writing skills, you’ll craft stories that leave a lasting impact.

Read: Get to Know What are the Main Elements in Creative Writing.

Immerse readers in worlds they’ve never experienced, challenge their perspectives, and ignite their own imaginative sparks. Whether you’re writing a narrative paragraph, a descriptive passage, or an analytical essay, remember that imagination is your greatest ally. As you embark on your writing journey, let your imagination soar and watch your stories come to life in ways you’ve never imagined before.

- About The Author

- Latest Posts

You May Also Like

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Imagination

To imagine is to represent without aiming at things as they actually, presently, and subjectively are. One can use imagination to represent possibilities other than the actual, to represent times other than the present, and to represent perspectives other than one’s own. Unlike perceiving and believing, imagining something does not require one to consider that something to be the case. Unlike desiring or anticipating, imagining something does not require one to wish or expect that something to be the case.

Imagination is involved in a wide variety of human activities, and has been explored from a wide range of philosophical perspectives. Philosophers of mind have examined imagination’s role in mindreading and in pretense. Philosophical aestheticians have examined imagination’s role in creating and in engaging with different types of artworks. Epistemologists have examined imagination’s role in theoretical thought experiments and in practical decision-making. Philosophers of language have examined imagination’s role in irony and metaphor.

Because of the breadth of the topic, this entry focuses exclusively on contemporary discussions of imagination in the Anglo-American philosophical tradition. For an overview of historical discussions of imagination, see the sections on pre-twentieth century and early twentieth century accounts of entry on mental imagery ; for notable historical accounts of imagination, see corresponding entries on Aristotle , Thomas Hobbes , David Hume , Immanuel Kant , and Gilbert Ryle ; for a more detailed and comprehensive historical survey, see Brann 1991; and for a sophisticated and wide-ranging discussion of imagination in the phenomenological tradition, see Casey 2000.

1.1 Varieties of Imagination

1.2 taxonomies of imagination, 1.3 norms of imagination, 2.1 imagination and belief, 2.2 imagination and desire, 2.3 imagination, imagery, and perception, 2.4 imagination and memory, 2.5 imagination and supposition, 3.1 mindreading, 3.2 pretense, 3.3 psychopathology.

- Supplement: Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts

3.5 Creativity

3.6 knowledge, 3.7 figurative language, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the nature of imagination.

A variety of roles have been attributed to imagination across various domains of human understanding and activity ( section 3 ). Not surprisingly, it is doubtful that there is one component of the mind that can satisfy all the various roles attributed to imagination (Kind 2013). Nevertheless, perhaps guided by these roles, philosophers have attempted to clarify the nature of imagination in three ways. First, philosophers have tried to disambiguate different senses of the term “imagination” and, in some cases, point to some core commonalities amongst the different disambiguations ( section 1.1 ). Second, philosophers have given partial taxonomies to distinguish different types of imaginings ( section 1.2 ). Third, philosophers have located norms that govern paradigmatic imaginative episodes ( section 1.3 ).

There is a general consensus among those who work on the topic that the term “ imagination ” is used too broadly to permit simple taxonomy. Indeed, it is common for overviews to begin with an invocation of P.F. Strawson’s remarks in “Imagination and Perception”, where he writes:

The uses, and applications, of the terms “image”, “imagine”, “imagination”, and so forth make up a very diverse and scattered family. Even this image of a family seems too definite. It would be a matter of more than difficulty to identify and list the family’s members, let alone their relations of parenthood and cousinhood. (Strawson 1970: 31)

These taxonomic challenges carry over into attempts at characterization. In the opening chapter of Mimesis as Make-Believe —perhaps the most influential contemporary monograph on imagination—Kendall Walton throws up his hands at the prospect of delineating the notion precisely. After enumerating and distinguishing a number of paradigmatic instances of imagining, he asks:

What is it to imagine? We have examined a number of dimensions along which imaginings can vary; shouldn’t we now spell out what they have in common?—Yes, if we can. But I can’t. (Walton 1990: 19)

Leslie Stevenson (2003: 238) makes arguably the only recent attempt at a somewhat comprehensive inventory of the term’s uses, covering twelve of “the most influential conceptions of imagination” that can be found in recent discussions in “philosophy of mind, aesthetics, ethics, poetry and … religion”.

To describe the varieties of imaginings, philosophers have given partial and overlapping taxonomies.

Some taxonomies are merely descriptive, and they tend to be less controversial. For example, Kendall Walton (1990) distinguishes between spontaneous and deliberate imagining (acts of imagination that occur with or without the one’s conscious direction); between occurrent and nonoccurrent imaginings (acts of imagination that do or do not occupy the one’s explicit attention); and between social and solitary imaginings (episodes of imagining that occur with or without the joint participation of several persons).

One notable descriptive taxonomy concerns imagining from the inside versus from the outside (Williams 1973; Wollheim 1973; see Ninan 2016 for an overview). To imagine from the outside that one is Napoleon involves imagining a scenario in which one is Napoleon. To imagine from the inside that one is Napoleon involves that plus something else: namely, that one is occupying the perspective of Napoleon. Imagining from the inside is essentially first-personal, imagining from the outside is not. This distinction between two modes of imagining is especially notable for its implications for thought experiments about the metaphysics of personal identity (Nichols 2008; Ninan 2009; Williams 1973).

Some taxonomies aim to be more systematic—to carve imaginings at their joints, so to speak—and they, as one might expect, tend to be more controversial.

Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) distinguishes creative imagination (combining ideas in unexpected and unconventional ways); sensory imagination (perception-like experiences in the absence of appropriate stimuli); and what they call recreative imagination (an ability to experience or think about the world from a perspective different from the one that experience presents). Neil Van Leeuwen (2013, 2014) takes a similar approach to delineate three common uses of “imagination” and cognate terms. First, these terms can be used to refer to constructive imagining , which concerns the process of generating mental representations. Second, these terms can be used to refer to attitude imagining , which concerns the propositional attitude one takes toward mental representations. Third, these terms can be used to refer to imagistic imagining , which concerns the perception-like format of mental representations.

Amy Kind and Peter Kung (2016b) pose the puzzle of imaginative use—on the seeming irreconcilability between the transcendent uses of imagination, which enables one to escape from or look beyond the world as it is, and the instructive uses of imagination, which enables one to learn about the world as it is. Kind and Kung ultimately resolve the puzzle by arguing that the same attitude can be put to these seemingly disparate uses because the two uses differ not in kind, but in degree—specifically, the degree of constraint on imaginings.

Finally, varieties of imagination might be classified in terms of their structure and content. Consider the following three types of imaginings, each illustrated with an example. When one imagines propositionally , one represents to oneself that something is the case. So, for example, Juliet might imagine that Romeo is by her side . To imagine in this sense is to stand in some mental relation to a particular proposition (see the entry on propositional attitude reports ). When one imagines objectually , one represents to oneself a real or make-believe entity or situation (Yablo 1993; see also Martin 2002; Noordhof 2002; O’Shaughnessy 2000). So, for example, Prospero might imagine an acorn or a nymph or the city of Naples or a wedding feast . To imagine in this sense is to stand in some mental relation to a representation of an (imaginary or real) entity or state of affairs. When one imagines X-ing , one simulatively represents to oneself some sort of activity or experience (Walton 1990). So, for example, Ophelia might imagine seeing Hamlet or getting herself to a nunnery . To imagine in this sense is to stand in a first-personal mental relation to some (imaginary or real) behavior or perception.

There are general norms that govern operations of imagination (Gendler 2003).

Mirroring is manifest to the extent that features of the imaginary situation that have not been explicitly stipulated are derivable via features of their real-world analogues, or, more generally, to the extent that imaginative content is taken to be governed by the same sorts of restrictions that govern believed content. For example, in a widely-discussed experiment conducted by Alan Leslie (1994), children are asked to engage in an imaginary tea party. When an experimenter tips and “spills” one of the (empty) teacups, children consider the non-tipped cup to be “full” (in the context of the pretense) and the tipped cup to be “empty” (both within and outside of the context of the pretense). In fact, both make-believe games and more complicated engagements with the arts are governed by principles of generation , according to which prompts or props prescribe particular imaginings (Walton 1990).

Quarantining is manifest to the extent that events within the imagined or pretended episode are taken to have effects only within a relevantly circumscribed domain. So, for example, the child engaging in the make-believe tea party does not expect that “spilling” (imaginary) “tea” will result in the table really being wet, nor does a person who imagines winning the lottery expect that when she visits the ATM, her bank account will contain a million dollars. More generally, quarantining is manifest to the extent that proto-beliefs and proto-attitudes concerning the imagined state of affairs are not treated as beliefs and attitudes relevant to guiding action in the actual world.

Although imaginative episodes are generally governed by mirroring and quarantining, both may be violated in systematic ways.

Mirroring gives way to disparity as a result of the ways in which (the treatment of) imaginary content may differ from (that of) believed content. Imagined content may be incomplete (for example, there may be no fact of the matter (in the pretense) just how much tea has spilled on the table) or incoherent (for example, it might be that the toaster serves (in the pretense) as a logical-truth inverter). And content that is imagined may give rise to discrepant responses , most strikingly in cases of discrepant affect—where, for example, the imminent destruction of all human life is treated as amusing rather than terrifying.

Quarantining gives way to contagion when imagined content ends up playing a direct role in actual attitudes and behavior (see also Gendler 2008a, 2008b). This is common in cases of affective transmission , where an emotional response generated by an imagined situation may constrain subsequent behavior. For example, imagining something fearful (such as a tiger in the kitchen) may give rise to actual hesitation (such as reluctance to enter the room). And it also occurs in cases of cognitive transmission , where imagined content is thereby “primed” and rendered more accessible in ways that go on to shape subsequent perception and experience. For example, imagining some object (such as a sheep) may make one more likely to “perceive” such objects in one’s environment (such as mistaking a rock for a ram).

2. Imagination in Cognitive Architecture

One way to make sense of the nature of imagination is by drawing distinctions, giving taxonomies, and elucidating governing norms ( section 1 ). Another, arguably more prominent, way to make sense of the nature is by figuring out, in a broadly functionalist framework, how it fits in with more well-understood mental entities from folk psychology and scientific psychology (see the entry on functionalism ).

There are two related tasks involved. First, philosophers have used other mental entities to define imagination by contradistinction (but see Wiltsher forthcoming for a critique of this approach). To give an oversimplified example, many philosophers hold that imagining is like believing except that it does not directly motivate actions. Second, philosophers have used other mental entities to understand the inputs and outputs of imagination. To give an oversimplified example, many philosophers hold that imagination does not output to action-generating systems.

Amongst the most widely-discussed mental entities in contemporary discussions of imagination are belief ( section 2.1 ), desire ( section 2.2 ), mental imagery ( section 2.3 ), memory ( section 2.4 ), and supposition ( section 2.5 ). The resolution of these debates ultimately rest on the extent to which the imaginative attitude(s) posited can fulfill the roles ascribed to imagination from various domains of human understanding and activity ( section 3 ).

To believe is to take something to be the case or regard it as true (see the entry on belief ). When one says something like “the liar believes that his pants are on fire”, one attributes to the subject (the liar) an attitude (belief) towards a proposition (his pants are on fire). Likewise, when one says something like “the liar imagines that his pants are on fire”, one attributes to the subject (the liar) an attitude (imagination) towards a proposition (his pants are on fire). The similarities and differences between the belief attribution and the imagination attribution point to similarities and differences between imagining and believing.

Imagining and believing are both cognitive attitudes that are representational. They take on the same kind of content: representations that stand in inferential relationship with one another. On the single code hypothesis , it is the sameness of the representational format that grounds functional similarities between imagining and believing (Nichols & Stich 2000, 2003; Nichols 2004a). As for their differences, there are two main options for distinguishing imagining and believing (Sinhababu 2016).

The first option characterizes their difference in normative terms. While belief aims at truth, imagination does not (Humberstone 1992; Shah & Velleman 2005). If the liar did not regard it as true that his pants are on fire, then it seems that he cannot really believe that his pants are on fire. By contrast, even if the liar did not regard it as true that his pants are on fire, he can still imagine that his pants are on fire. While the norm of truth is constitutive of the attitude of belief, it is not constitutive of the attitude of imagination. In dissent, Neil Sinhababu (2013) argues that the norm of truth is neither sufficient nor necessary for distinguishing imagining and believing.

The second option characterizes their difference in functional terms. One purported functional difference between imagination and belief concerns their characteristic connection to actions. If the liar truly believes that his pants are on fire, he will typically attempt to put out the fire by, say, pouring water on himself. By contrast, if the liar merely imagines that his pants are on fire, he will typically do no such thing. While belief outputs to action-generation system, imagination does not (Nichols & Stich 2000, 2003). David Velleman (2000) and Tyler Doggett and Andy Egan (2007) point to particular pretense behaviors to challenge this way of distinguishing imagining and believing. Velleman argues that a belief-desire explanation of children’s pretense behaviors makes children “depressingly unchildlike”. Doggett and Egan argue that during immersive episodes, pretense behaviors can be directly motivated by imagination. In response to these challenges, philosophers typically accept that imagination can have a guidance or stage-setting role in motivating behaviors, but reject that it directly outputs to action-generation system (Van Leeuwen 2009; O’Brien 2005; Funkhouser & Spaulding 2009; Everson 2007; Kind 2011; Currie & Ravenscroft 2002).

Another purported functional difference between imagination and belief concerns their characteristic connection to emotions. If the liar truly believes that his pants are on fire, then he will be genuinely afraid of the fire; but not if he merely imagines so. While belief evokes genuine emotions toward real entities, imagination does not (Walton 1978, 1990, 1997; see also related discussion of the paradox of fictional emotions in Supplement on Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts ). This debate is entangled with the controversy concerning the nature of emotions (see the entry on emotion ). In rejecting this purported functional difference, philosophers also typically reject narrow cognitivism about emotions (Nichols 2004a; Meskin & Weinberg 2003; Weinberg & Meskin 2005, 2006; Kind 2011; Spaulding 2015; Carruthers 2003, 2006).

Currently, the consensus is that there exists some important difference between imagining and believing. Yet, there are two distinct departures from this consensus. On the one hand, some philosophers have pointed to novel psychological phenomena in which it is unclear whether imagination or belief is at work—such as delusions (Egan 2008a) and immersed pretense (Schellenberg 2013)—and argued that the best explanation for these phenomena says that imagination and belief exists on a continuum. In responding to the argument from immersed pretense, Shen-yi Liao and Tyler Doggett (2014) argue that a cognitive architecture that collapses distinctive attitudes on the basis of borderline cases is unlikely to be fruitful in explaining psychological phenomena. On the other hand, some philosophers have pointed to familiar psychological phenomena and argued that the best explanation for these phenomena says that imagination is ultimately reducible to belief. Peter Langland-Hassan (2012, 2014) argues that pretense can be explained with only reference to beliefs—specifically, beliefs about counterfactuals. Derek Matravers (2014) argues that engagements with fictions can be explained without references to imaginings.

To desire is to want something to be the case (see the entry on desire ). Standardly, the conative attitude of desire is contrasted with the cognitive attitude of belief in terms of direction of fit: while belief aims to make one’s mental representations match the way the world is, desire aims to make the way the world is match one’s mental representations. Recall that on the single code hypothesis , there exists a cognitive imaginative attitude that is structurally similar to belief. Is there a conative imaginative attitude—call it desire-like imagination (Currie 1997, 2002a, 2002b, 2010; Currie & Ravenscroft 2002), make-desire (Currie 1990; Goldman 2006), or i-desire (Doggett & Egan 2007, 2012)—that is structurally similar to desire?

The debates on the relationship between imagination and desire is, not surprisingly, thoroughly entangled with the debates on the relationship between imagination and belief. One impetus for positing a conative imaginative attitude comes from behavior motivation in imaginative contexts. Tyler Doggett and Andy Egan (2007) argue that cognitive and conative imagination jointly output to action-generation system, in the same way that belief and desire jointly do. Another impetus for positing a conative imaginative attitude comes from emotions in imaginative contexts (see related discussions of the paradox of fictional emotions and the paradoxes of tragedy and horror in Supplement on Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts ). Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) and Doggett and Egan (2012) argue the best explanation for people’s emotional responses toward non-existent fictional characters call for positing conative imagination. Currie and Ravenscroft (2002), Currie (2010), and Doggett and Egan (2007) argue that the best explanation for people’s apparently conflicting emotional responses toward tragedy and horror too call for positing conative imagination.

Given the entanglement between the debates, competing explanations of the same phenomena also function as arguments against conative imagination (Nichols 2004a, 2006b; Meskin & Weinberg 2003; Weinberg & Meskin 2005, 2006; Spaulding 2015; Kind 2011; Carruthers 2003, 2006; Funkhouser & Spaulding 2009; Van Leeuwen 2011). In addition, another argument against conative imagination is that its different impetuses call for conflicting functional properties. Amy Kind (2016b) notes a tension between the argument from behavior motivation and the argument from fictional emotions: conative imagination must be connected to action-generation in order for it to explain pretense behaviors, but it must be disconnected from action-generation in order for it to explain fictional emotions. Similarly, Shaun Nichols (2004b) notes a tension between Currie and Ravenscroft’s (2002) argument from paradox of fictional emotions and argument from paradoxes of tragedy and horror.

To have a (merely) mental image is to have a perception-like experience triggered by something other than the appropriate external stimulus; so, for example, one might have “a picture in the mind’s eye or … a tune running through one’s head” (Strawson 1970: 31) in the absence of any corresponding visual or auditory object or event (see the entry on mental imagery ). While it is propositional imagination that gets compared to belief and desire, it is sensory or imagistic imagination that get compared to perception (Currie & Ravenscroft 2002). Although it is possible to form mental images in any of the sensory modalities, the bulk of discussion in both philosophical and psychological contexts has focused on visual imagery.

Broadly, there is agreement on the similarity between mental imagery and perception in phenomenology, which can be explicated as a similarity in content (Nanay 2016b; see, for example, Kind 2001; Nanay 2015; Noordhof 2002). Potential candidates for distinguishing mental imagery and perception include intensity (Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature ; but see Kind 2017), voluntariness (McGinn 2004; Ichikawa 2009), causal relationship with the relevant object (Noordhof 2002); however, no consensus exists on features that clearly distinguish the two, in part because of ongoing debates about perception (see the entries on contents of perception and epistemological problems of perception ).

What is the relationship between imaginings and mental imagery?

Historically, mental imagery is thought to be an essential component of imaginings. Aristotle’s phantasia , which is sometimes translated as imagination, is a faculty that produces images ( De Anima ; see entry on Aristotle’s conception of imagination ; but see Caston 1996). René Descartes ( Meditations on First Philosophy ) and David Hume ( Treatise of Human Nature ) both thought that to imagine just is to hold a mental image, or an impression of perception, in one’s mind. However, George Berkeley’s puzzle of visualizing the unseen ( Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous ) arguably suggests the existence of a non-imagistic hypothetical attitude.

Against the historical orthodoxy, the contemporary tendency is to recognize that there is at least one species of imagination—propositional imagination—that does not require mental imagery. For example, Kendall Walton simply states, “imagining can occur without imagery” (1990: 13). In turn, against this contemporary tendency, Amy Kind (2001) argues that an image-based account can explain three crucial features of imagination—directedness, active nature, and phenomenological character—better than its imageless counterpart. As a partial reconciliation of the two, Peter Langland-Hassan (2015) develops a pluralist position on which there exists a variety of imaginative attitudes, including ones that can take on hybrid contents that are partly propositional and partly sensorily imagistic. (For a nuanced overview of this debate, see Gregory 2016: 103–106.)

Finally, the relationship between mental imagery and perception has potential implications for the connection between imagination and action. The orthodoxy on propositional belief-like imagination holds that imagination does not directly output to action-generation system; rather, the connection between the two is mediated by belief and desire. In contrast, the enactivist program in the philosophy of perception holds that perception can directly output to action-generation system (see, for example, Nanay 2013). Working from the starting point that imagistic imagination is similar to perception in its inclusion of mental imagery, some philosophers have argued for a similar direct connection between imagistic imagination and action-generation system (Langland-Hassan 2015; Nanay 2016a; Van Leeuwen 2011, 2016b). That is, there exist imagery-oriented actions that are analogous to perception-oriented actions. For example, Neil Van Leeuwen (2011) argues that an account of imagination that is imagistically-rich can better explain pretense behaviors than its propositional-imagination-only rivals. Furthermore, Robert Eamon Briscoe (2008, 2018) argues that representations that blend inputs from perception and mental imagery, which he calls “make-perceive”, guide many everyday actions. For example, a sculptor might use a blend of the visual perception of a stone and the mental imagery of different parts of the stone being subtracted to guide their physical manipulation of the stone.

To remember , roughly, is to represent something that is no longer the case. On the standard taxonomy, there are three types of memory. Nondeclarative memory involves mental content that is not consciously accessible, such as one’s memory of how to ride a bike. Semantic declarative memory involves mental content that are propositional and not first-personal, such as one’s memory that Taipei is the capital of Taiwan. Episodic declarative memory involves mental content about one’s own past, such as one’s memory of the birth of one’s child. (See the entry on memory for a detailed discussion of this taxonomy, and especially the criterion of episodicity.) In situating imagination in cognitive architecture, philosophers have typically focused on similarities and differences between imagination and episodic declarative memory.

There are obvious similarities between imagination and memory: both typically involve imagery, both typically concern what is not presently the case, and both frequently involve perspectival representations. Thomas Hobbes ( Leviathan : 2.3) claims that “imagination and memory are but one thing, which for diverse consideration has diverse names”. In making this bold statement, Hobbes represents an extreme version of continuism, a view on which imagination and memory refer to the same psychological mechanisms.

The orthodoxy on imagination and memory in the history of philosophy, however, is discontinuism, a view on which there are significant differences between imagination and memory, even if there are overlaps in their psychological mechanisms. Some philosophers find the distinction in internalist factors, such as the phenomenological difference between imagining and remembering. Most famously, David Hume sought to distinguish the two in terms of vivacity —“the ideas of the memory are much more lively and strong than those of the imagination” ( Treatise of Human Nature : 1.3; but see Kind 2017). Others who have adopted a phenomenological criterion include René Descartes, Bertrand Russell, and William James (De Brigard 2017). Other philosophers find the distinction in externalist factors, such as the causal connection that exists between memories and the past that is absent with imagination. Aristotle uses the causal connection criterion to distinguish between imagination and memory ( De Anima 451a2; 451a8–12; see De Brigard 2017). Indeed, nowadays the idea that a causal connection is essential to remembering is accepted as “philosophical common sense” (see the entry on memory ; but see also De Brigard 2014 on memory traces). As such, it is unsurprising that discontinuism remains the orthodoxy. As J. O. Urmson (1967: 83) boldly claims, “One of these universally admitted distinctions is that between memory and imagination”.

In recent years, two sets of findings from cognitive science has given philosophers reasons to push back against discontinuism.

The first set of findings concern distortions and confabulations. The traditional conception of memory is that it functions as an archive: past experiences are encapsulated and stored in the archive, and remembering is just passively retrieving the encapsulated mental content from the archive (Robins 2016). Behavioral psychology has found numerous effects that challenge the empirical adequacy of the archival conception of memory. Perhaps the most well-known is the misinformation effect, which occurs when a subject incorporates inaccurate information into their memory of an event—even inaccurate information that they received after the event (Loftus 1979 [1996]).

The second set of findings concern the psychological underpinnings of “mental time travel”, or the similarities between remembering the past and imagining the future, which is also known as mental time travel (see Schacter et al. 2012 for a review). Using fMRI, neuroscientists have found a striking overlap in the brain activities for remembering the past and imagining the future, which suggest that the two psychological processes utilize the same neural network (see, for example, Addis et al. 2007; Buckner & Carroll 2007; Gilbert & Wilson 2007; Schacter et al. 2007; Suddendorf & Corballis 1997, 2007). The neuroscientific research is preceded by and corroborated by works from developmental psychology (Atance & O’Neill 2011) and on neurodivergent individuals: for example, the severely amnesic patient KC exhibits deficits with remembering the past and imagining the future (Tulving 1985), and also exhibits deficits with the generation of non-personal fictional narratives (Rosenbaum et al. 2009). Note that, despite the evocative contrast between “remembering the past” and “imagining the future”, it is questionable whether temporality is the central contrast. Indeed, some philosophers and psychologists contend that temporality is orthogonal to the comparison between imagination and memory (De Brigard & Gessell 2016; Schacter et al. 2012).

These two set of findings have given rise to an alternative conception that sees memory as essentially constructive, in which remembering is actively generating mental content that more or less represent the past. The constructive conception of memory is in a better position to explain why memories can contain distortions and confabulations (but see Robins 2016 for complications), and why remembering makes use of the same neural networks as imagining.

In turn, this constructive turn in the psychology and philosophy of memory has revived philosophers’ interest in continuism concerning imagination and memory. Kourken Michaelian (2016) explicitly rejects the causal connection criterion and defends a theory on which remembering, like imagining, centrally involves simulation. Karen Shanton and Alvin Goldman (2010) characterizes remembering as mindreading one’s past self. Felipe De Brigard (2014) characterizes remembering as a special instance of hypothetical thinking. Robert Hopkins (2018) characterizes remembering as a kind of imagining that is controlled by the past. However, the philosophical interpretation of empirical research remain contested; in dissent, Dorothea Debus (2014, 2016) considers the same sets of findings but ultimately concludes that remembering and imagining remain distinct mental kinds.

To suppose is to form a hypothetical mental representation. There exists a highly contentious debate on whether supposition is continuous with imagination, which is also a hypothetical attitude, or whether there are enough differences to make them discontinuous. There are two main options for distinguishing imagination and supposition, by phenomenology and by function.

The phenomenological distinction standardly turns on the notion of vivacity: whereas imaginings are vivid, suppositions are not. Indeed, one often finds in this literature the contrast between “merely supposing” and “vividly imagining”. Although vivacity has been frequently invoked in discussions of imagination, Amy Kind (2017) draws on empirical and theoretical considerations to argue that it is ultimately philosophically untenable. If that is correct, then the attempt to demarcate imagination and supposition by their vivacity is untenable too. More rarely, other phenomenological differences are invoked; for example, Brian Weatherson (2004) contends that “supposing can be coarse in a way that imagining cannot”.

Table 1. Architectural similarities and differences between imagination and supposition (Weinberg & Meskin 2006).

There have been diverse functional distinctions attributed to the discontinuity between imagination and supposition, but none has gained universal acceptance. Richard Moran (1994) contends that imagination tends to give rise to a wide range of further mental states, including affective responses, whereas supposition does not (see also Arcangeli 2014, 2017). Tamar Szabó Gendler (2000a) contends that while attempting to imagine something like that female infanticide is morally right seems to generate imaginative resistance, supposing it does not (see the discussion on imaginative resistance in Supplement on Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts ). Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) contend that supposition involves only cognitive imagination, but imagination involves both cognitive and conative imagination. Alvin Goldman contends that suppositional imagination involves supposing that particular content obtains (for example, supposing that I am elated) but enactment imagination involves “enacting, or trying to enact, elation itself.” (2006: 47–48, italics omitted). Tyler Doggett and Andy Egan (2007) contend that imagination tends to motivate pretense actions, but supposition tends not to. On Jonathan Weinberg and Aaron Meskin (2006)’s synthesis, while there are a few functional similarities, there are many more functional differences between imagination and supposition (Table 1).

There remain ongoing debates about specific alleged functional distinctions, and about whether the functional distinctions are numerous or fundamental enough to warrant discontinuism or not. Indeed, it remains contentious which philosophers count as continuists and which philosophers count as discontinuists (for a few sample taxonomies, see Arcangeli 2017; Balcerak Jackson 2016; Kind 2013).

3. Roles of Imagination

Much of the contemporary discussion of imagination has centered around particular roles that imagination is purported to play in various domains of human understanding and activity. Amongst the most widely-discussed are the role of imagination in understanding other minds ( section 3.1 ), in performing and recognizing pretense ( section 3.2 ), in characterizing psychopathology ( section 3.3 ), in engaging with the arts ( section 3.4 ), in thinking creatively ( section 3.5 ), in acquiring knowledge about possibilities ( section 3.6 ), and in interpreting figurative language ( section 3.7 ).

The variety of roles ascribed to imagination, in turn, provides a guide for discussions on the nature of imagination ( section 1 ) and its place in cognitive architecture ( section 2 ).

Mindreading is the activity of attributing mental states to oneself and to others, and of predicting and explaining behavior on the basis of those attributions. Discussions of mindreading in the 1990s were often framed as debates between “theory theory”—which holds that the attribution of mental states to others is guided by the application of some (tacit) folk psychological theory—and “simulation theory”—which holds that the attribution of mental states is guided by a process of replicating or emulating the target’s (apparent) mental states, perhaps through mechanisms involving the imagination. (Influential collections of papers on this debate include Carruthers & Smith (eds.) 1996; Davies & Stone (eds.) 1995a, 1995b.) In recent years, proponents of both sides have increasingly converged on common ground, allowing that both theory and simulation play some role in the attribution of mental states to others (see Carruthers 2003; Goldman 2006; Nichols & Stich 2003). Many such hybrid accounts include a role for imagination.

On theory theory views, mindreading involves the application of some (tacit) folk psychological theory that allows the subject to make predictions and offer explanations of the target’s beliefs and behaviors. On pure versions of such accounts, imagination plays no special role in the attribution of mental states to others. (For an overview of theory theory, see entry on folk psychology as a theory ).

On simulation theory views, mindreading involves simulating the target’s mental states so as to exploit similarities between the subject’s and target’s processing capacities. It is this simulation that allows the subject to make predictions and offer explanations of the target’s beliefs and behaviors. (For early papers, see Goldman 1989; Gordon 1986; Heal 1986; for recent dissent, see, for example, Carruthers 2009; Gallagher 2007; Saxe 2005, 2009; for an overview of simulation theory, see entry on folk psychology as mental simulation ).

Traditional versions of simulation theory typically describe simulation using expressions such as “imaginatively putting oneself in the other’s place”. How this metaphor is understood depends on the specific account. (A collection of papers exploring various versions of simulation theory can be found in Dokic & Proust (eds.) 2002.) On many accounts, the projection is assumed to involve the subject’s imaginatively running mental processes “off-line” that are directly analogous to those being run “on-line” by the target (for example Goldman 1989). Whereas the “on-line” mental processes are genuine, the “off-line” mental processes are merely imagined. For example, a target that is deciding whether to eat sushi for lunch is running their decision-making processes “on-line”; and a subject that is simulating the target’s decision-making is running the analogous processes “off-line”—in part, by imagining the relevant mental states of the target. Recent empirical work in psychology has explored the accuracy of such projections (Markman, Klein, & Suhr (eds.) 2009, section V; Saxe 2005, 2006, 2009.)

Though classic simulationist accounts have tended to assume that the simulation process is at least in-principle accessible to consciousness, a number of recent simulation-style accounts appeal to neuroscientific evidence suggesting that at least some simulative processes take place completely unconsciously. On such accounts of mindreading, no special role is played by conscious imagination (see Goldman 2009; Saxe 2009.)

Many contemporary views of mindreading are hybrid theory views according to which both theorizing and simulation play a role in the understanding of others’ mental states. Alvin Goldman (2006), for example, argues that while mindreading is primarily the product of simulation, theorizing plays a role in certain cases as well. Many recent discussions have endorsed hybrid views of this sort, with more or less weight given to each of the components in particular cases (see Carruthers 2003; Nichols & Stich 2003.)

A number of philosophers have suggested that the mechanisms underlying subjects’ capacity to engage in mindreading are those that enable engagement in pretense behavior (Currie & Ravenscroft 2002; Goldman 2006; Nichols & Stich 2003; for an overview of recent discussions, see Carruthers 2009.) According to such accounts, engaging in pretense involves imaginatively taking up perspectives other than one’s own, and the ability to do so skillfully may rely on—and contribute to—one’s ability to understand those alternate perspectives (see the entry on empathy ). Partly in light of these considerations, the relative lack of spontaneous pretense in children with autistic spectrum disorders is taken as evidence for a link between the skills of pretense and empathy.

Pretending is an activity that occurs during diverse circumstances, such as when children make-believe, when criminals deceive, and when thespians act (Langland-Hassan 2014). Although “imagination” and “pretense” have been used interchangeably (Ryle 1949), in this section we will use “imagination” to refer to one’s state of mind, and “pretense” to refer to the one’s actions in the world.

Different theories of pretense disagree fundamentally about what it is to pretend (see Liao & Gendler 2011 for an overview). Consequently, they also disagree about the mental states that enable one to pretend. Metarepresentational theories hold that engaging in pretend play requires the innate mental-state concept pretend (Baron-Cohen, Leslie, & Frith 1985; Friedman 2013; Friedman & Leslie 2007; Leslie 1987, 1994). To pretend is to represent one’s own representations under the concept pretend. Behaviorist theories hold that engaging in pretend play requires a process of behaving-as-if (Harris 1994, 2000; Harris & Kavanaugh 1993; Jarrold et al. 1994; Lillard & Flavell 1992; Nichols & Stich 2003; Perner 1991; Rakoczy, Tomasello, & Striano 2004; Stich & Tarzia 2015). Different behaviorist theories explicate behaving-as-if in different ways, but all aim to provide an account of pretense without recourse to the innate mental-state concept pretend.

Philosophical and psychological theories have sought to explain both the performance of pretense and the recognition of pretense, especially concerning evidence from developmental psychology (see Lillard 2001 for an early overview). On the performance side, children on a standard developmental trajectory exhibit early indicators of pretend play around 15 months; engage in explicit prop-oriented play by 24 months; and engage in sophisticated joint pretend play with props by 36 months (Harris 2000; Perner, Baker, & Hutton 1994; Piaget 1945 [1951]). On the recognition side, children on a standard developmental trajectory distinguish pretense and reality via instinctual behavioral cues around 15–18 months; and start to do so via conventional behavioral cues from 36 months on (Friedman et al. 2010; Lillard & Witherington 2004; Onishi & Baillargeon 2005; Onishi, Baillargeon, & Leslie 2007; Richert and Lillard 2004).

Not surprisingly, the debate between theories of pretense often rest on interpretations of such empirical evidence. For example, Ori Friedman and Alan Leslie (2007) argue that behavioral theories cannot account for the fact that children as young as 15 months old can recognize pretend play and its normativity (Baillargeon, Scott, & He 2010). Specifically, they argue that behavioral theories do not offer straightforward explanations of this early development of pretense recognition, and incorrectly predicts that children systematically mistake other acts of behaving-as-if—such as those that stem from false beliefs—for pretense activities. In response, Stephen Stich and Joshua Tarzia (2015) has acknowledged these problems for earlier behaviorist theories, and developed a new behaviorist theory that purportedly explains the totality of empirical evidence better than metarepresentational rivals. Importantly, Stich and Tarzia argue that their account can better explain Angeline Lillard (1993)’s empirical finding that young children need not attribute a mental concept such as pretend to someone else in order to understand them as pretending.

The debate concerning theories of pretense has implications for the role of imagination in pretense. Behaviorist theories tend to take imagination as essential to explaining pretense performance; metarepresentational theories do not. (However, arguably the innate mental-state concept pretend posited by metarepresentational theories serve similar functions. See Nichols and Stich’s (2000) discussion of the decoupler mechanism, which explicitly draws from Leslie 1987. Currie and Ravenscroft (2002) give a broadly behaviorist theory of pretense that does not require imagination.) Specifically, on most behaviorist theories, imagination is essential for guiding elaborations of pretense episodes, especially via behaviors (Picciuto & Carruthers 2016; Stich & Tarzia 2015).

Most recently, Peter Langland-Hassan (2012, 2014) has developed a theory that aims to explain pretense behavior and pretense recognition without appeal to either metarepresentation or imagination. Langland-Hassan argues that pretense behaviors can be adequately explained by beliefs, desires, and intentions—including beliefs in counterfactuals; and that the difference between pretense and sincerity more generally can be adequately characterized in terms of a person’s beliefs, intentions, and desires. While Langland-Hassan does not deny that pretense is in some sense an imaginative activity, he argues that we do not need to posit a sui generis component of the mind to account for it.

Autism and delusions have been—with much controversy—characterized as disorders of imagination. That is, the atypical patterns of cognition and behavior associated with each psychopathology have been argued to result from atypical functions of imagination.

Autism can be characterized in terms of a trio of atypicalities often referred to as “Wing’s triad”: problems in typical social competence, communication, and imagination (Happé 1994; Wing & Gould 1979). The imaginative aspect of autism interacts with other prominent roles of imagination, namely mindreading, pretense, and engagement with the arts (Carruthers 2009). Children with autism do not engage in spontaneous pretend play in the ways that typically-developing children do, engaging instead in repetitive and sometimes obsessional activities; and adults with autism often show little interest in fiction (Carpenter, Tomasello, & Striano 2005; Happé 1994; Rogers, Cook, & Meryl 2005; Wing & Gould 1979). The degree to which an imaginative deficit is implicated in autism remains a matter of considerable debate. Most radically, Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) have argued that, with respect to Wing’s triad, problems in typical social competence and communication are rooted in an inability to engage in imaginative activities.

Delusions can be characterized as belief-like mental representations that manifest an unusual degree of disconnectedness from reality (Bortolotti & Miyazono 2015). Particularly striking examples would include Capgras and Cotard delusions. In the former, the sufferer takes her friends and family to have been replaced by imposters; in the latter, the sufferer takes himself to be dead. More mundane examples might include ordinary cases of self-deception.

One approach to delusions characterize them as beliefs that are dysfunctional in their content or formation. (For a representative collection of papers that present and criticize this perspective, see Coltheart & Davies (eds.) 2000). However, another approach to delusions characterize them as dysfunctions of imaginings. Currie and Ravenscroft (2002: 170–175) argue that delusions are imaginings that are misidentified by the subject as the result of an inability to keep track of the sources of one’s thoughts. That is, a delusion is an imagined representation that is misidentified by the subject as a belief. Tamar Szabó Gendler (2007) argues that in cases of delusions and self-deceptions, imaginings come to play a role in one’s cognitive architecture similar to that typically played by beliefs. Andy Egan (2008a) likewise argues that the mental states involved in delusions are both belief-like (in their connection to behaviors and inferences) and imagination-like (in their circumscription); however, he argues that these functional similarities suggest the need to posit an in-between attitude called “bimagination”.

3.4 Engagement with the Arts

There is an entrenched historical connection between imagination and the arts. David Hume and Immanuel Kant both invoke imagination centrally in their exploration of aesthetic phenomena (albeit in radically different ways; see entries on Hume’s aesthetics and Kant’s aesthetics ). R.G. Collingwood (1938) defines art as the imaginative expression of feeling (Wiltsher 2018; see entry on Collingwood’s aesthetics ). Roger Scruton (1974) develops a Wittgensteinian account of imagination and accords it a central role in aesthetic experience and aesthetic judgment.