Advertisement

How to Prepare an Outstanding Journal Club Presentation

- Request Permissions

Rishi Sawhney; How to Prepare an Outstanding Journal Club Presentation. The Hematologist 2006; 3 (1): No Pagination Specified. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/hem.V3.1.1308

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Dr. Sawhney is a member of the ASH Trainee Council and a Fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Journal club presentations provide a forum through which hematology trainees keep abreast of new developments in hematology and engage in informal discussion and interaction. Furthermore, honing presentation skills and mastering the ability to critically appraise the evidence add to our armamentarium as clinicians. Outlined here is a systematic approach to preparing a journal club presentation, with emphasis on key elements of the talk and references for electronic resources. Use of these tools and techniques will contribute to the success of your presentation.

I. ARTICLE SELECTION:

The foundation of an outstanding journal club presentation rests on the choice of an interesting and well-written paper for discussion. Several resources are available to help you select important and timely research, including the American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club and the Diffusion section of The Hematologist . McMaster University has created the McMaster Online Rating of Evidence (MORE) system to identify the highest-quality published research. In fact, the ACP Journal Club uses the MORE system to select their articles 1 . Specific inclusion criteria have been delineated in order to distinguish papers with the highest scientific merit 2 . Articles that have passed this screening are then rated by clinicians on their clinical relevance and newsworthiness, using a graded scale 3 . With the help of your mentors and colleagues, you can use these criteria and the rating scale as informal guidelines to ensure that your chosen article merits presentation.

II. ARTICLE PRESENTATION:

Study Background: This section provides your audience with the necessary information and context for a thoughtful and critical evaluation of the article's significance. The goals are 1) to describe the rationale for and clinical relevance of the study question, and 2) to highlight the preclinical and clinical research that led to the current trial. Review the papers referenced in the study's "Background" section as well as previous work by the study's authors. It also may be helpful to discuss data supporting the current standard of care against which the study intervention is being measured.

Study Methodology and Results: Clearly describe the study population, including inclusion/exclusion criteria. A diagrammatic schema is easy to construct using PowerPoint software and will help to clearly illustrate treatment arms in complex trials. Explain the statistical methods, obtaining assistance from a statistician if needed. Take this opportunity to verbally and graphically highlight key results from the study, with plans to expand on their significance later in your presentation.

Author's Discussion: Present the authors' conclusions and their perspective on the study results, including explanations of inconsistent or unexpected results. Consider whether the conclusions drawn are supported by the data presented.

III. ARTICLE CRITIQUE:

This component of your presentation will define the success of your journal club. A useful and widely accepted approach to this analysis has been published in JAMA's series "User's guide to the medical literature." The Centre for Health Evidence in Canada has made the complete full-text set of these user's guides available online 4 . This site offers review guidelines for a menu of article types, and it is an excellent, comprehensive resource to focus your study critique. A practical, user-friendly approach to literature evaluation that includes a worksheet is also available on the ASH Web site for your use 5 .

While a comprehensive discussion of scientific literature appraisal is beyond the scope of this discussion, several helpful tips warrant mention here. In assessing the validity of the study, it is important to assess for potential sources of bias, including the funding sources and authors' affiliations. It is also helpful to look for accompanying editorial commentary, which can provide a unique perspective on the article and highlight controversial issues. You should plan to discuss the trade-offs between potential benefits of the study intervention versus potential risks and the cost. By utilizing the concept of number needed to treat (NNT), one can assess the true impact of the study intervention on clinical practice. Furthermore, by incorporating the incidence rates of clinically significant toxicities with the financial costs into the NNT, you can generate a rather sophisticated analysis of the study's impact on practice.

IV. CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS:

Restate the authors' take-home message followed by your own interpretation of the study. Provide a personal perspective, detailing why you find this paper interesting or important. Then, look forward and use this opportunity to "think outside the box." Do you envision these study results changing the landscape of clinical practice or redirecting research in this field? If so, how? In articles about therapy, future directions may include moving the therapy up to first-line setting, assessing the drug in combination regimens or other disease states, or developing same-class novel compounds in the pipeline. Searching for related clinical trials on the NIH Web site 6 can prove helpful, as can consultation with an expert in this field.

Good journal club discussions are integral to the educational experience of hematology trainees. Following the above approach, while utilizing the resources available, will lay the groundwork for an outstanding presentation.

WEB BASED REFERENCES

www.acpjc.org

hiru.mcmaster.ca/more/InclusionCriteria.htm

hiru.mcmaster.ca/more/RatingFormSample.htm

www.cche.net/main.asp

www.hematology.org/Trainees

www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Email alerts

Affiliations.

- Current Issue

- About The Hematologist

- Advertising in The Hematologist

- Editorial Board

- Permissions

- Submissions

- Email Alerts

- ASH Publications App

American Society of Hematology

- 2021 L Street NW, Suite 900

- Washington, DC 20036

- TEL +1 202-776-0544

- FAX +1 202-776-0545

ASH Publications

- Blood Advances

- Hematology, ASH Education Program

- ASH Clinical News

- The Hematologist

- Publications

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.

- 12. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press; 2001.

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 117.5K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Expert Consult

Journal Club: How to Build One and Why

By Michelle Sharp, MD; Hunter Young, MD, MHS

Published April 6, 2022

Journal clubs are a longstanding tradition in residency training, dating back to William Osler in 1875. The original goal of the journal club in Osler’s day was to share expensive texts and to review literature as a group. Over time, the goals of journal clubs have evolved to include discussion and review of current literature and development of skills for evaluating medical literature. The ultimate goal of a journal club is to improve patient care by incorporating evidence into practice.

Why are journal clubs important?

In 2004, Alper et al . reported that it would take more than 600 hours per month to stay current with the medical literature. That leaves residents with less than 5 hours a day to eat, sleep, and care for patients if they want to stay current, and it’s simply impossible. Journal clubs offer the opportunity for residents to review the literature and stay current. Furthermore, Lee et al . showed that journal clubs improve residents’ critical appraisal of the literature.

How do you get started?

The first step to starting a journal club is to decide on the initial goal. A good initial goal is to lay the foundation for critical thinking skills using literature that is interesting to residents. An introductory lecture series or primer on study design is a valuable way to start the journal club experience. The goal of the primer is not for each resident to become a statistician, but rather to lay the foundation for understanding basic study designs and the strengths and weaknesses of each design.

The next step is to decide on the time, frequency, and duration of the journal club. This depends on the size of your residency program and leadership support. Our journal club at Johns Hopkins is scheduled monthly during the lunch hour instead of a noon conference lecture. It is essential to pick a time when most residents in your program will be available to attend and a frequency that is sustainable.

How do you get residents to come?

Generally, if you feed them, they will come. In a cross-sectional analysis of journal clubs in U.S. internal medicine residencies, Sidorov found that providing food was associated with long-lasting journal clubs. Factors associated with higher resident attendance were fewer house staff, mandatory attendance, formal teaching, and an independent journal club (separate from faculty journal clubs).

The design or format of your journal club is also a key factor for attendance. Not all residents will have time during each rotation to read the assigned article, but you want to encourage these residents to attend nonetheless. One way to engage all residents is to assign one or two residents to lead each journal club, with the goal of assigning every resident at least one journal club during the year. If possible, pick residents who are on lighter rotations, so they have more time outside of clinical duties to dissect the article. To enhance engagement, allow the assigned residents to pick an article on a topic that they find interesting.

Faculty leadership should collaborate with residents on article selection and dissection and preparation of the presentation. Start each journal club with a 10- to 20-minute presentation by the assigned residents to describe the article (as detailed below) to help residents who did not have time to read the article to participate.

What are the nuts and bolts of a journal club?

To prepare a successful journal club presentation, it helps for the structure of the presentation to mirror the structure of the article as follows:

Background: Start by briefly describing the background of the study, prior literature, and the question the paper was intended to address.

Methods: Review the paper’s methods, emphasizing the study design, analysis, and other key points that address the validity and generalizability of the results (e.g., participant selection, treatment of potential confounders, and other issues that are specific to each study design).

Results: Discuss the results, focusing on the paper’s tables and figures.

Discussion: Restate the research question, summarize the key findings, and focus on factors that can affect the validity of the findings. What are potential biases, confounders, and other issues that affect the validity or generalizability of the findings to clinical practice? The study results should also be discussed in the context of prior literature and current clinical practice. Addressing the questions that remain unanswered and potential next steps can also be useful.

Faculty participation: At our institution, the faculty sponsor meets with the assigned residents to address their questions about the paper and guide the development of the presentation, ensuring that the key points are addressed. Faculty sponsors also attend the journal club to answer questions, emphasize key elements of the paper, and facilitate the open discussion after the resident’s presentation.

How do you measure impact?

One way to evaluate your journal club is to assess the evidence-based practice skills of the residents before and after the implementation of the journal club with a tool such as the Berlin questionnaire — a validated 15-question survey that assesses evidence-based practice skills. You can also conduct a resident satisfaction survey to evaluate the residents’ perception of the implementation of the journal club and areas for improvement. Finally, you can develop a rubric for evaluation of the resident presenters in each journal club session, and allow faculty to provide feedback on critical assessment of the literature and presentation skills.

Journal clubs are a great tradition in medical training and continue to be a valued educational resource. Set your goal. Consider starting with a primer on study design. Engage and empower residents to be part of the journal club. Enlist faculty involvement for guidance and mentorship. Measure the impact.

Journal Club: How to Prepare Effectively and Smash Your Presentation

Journal club. It’s so much more than orally dictating a paper to your peers.

It’s an opportunity to get a bunch of intelligent people in one place to share ideas. It’s a means to expand the scientific vocabulary of you and the audience. It’s a way to stimulate inventive research design.

But there are so many ways it can go wrong.

Poorly explained papers dictated blandly to an unengaged audience. Confusing heaps of data shoehorned into long presentations. Everybody stood awkwardly outside a meeting room you thought would be free.

Whether you are unsure what journal club is, are thinking of starting one, or simply want to up your presentation game—you’ve landed on the ultimate journal club guide.

The whats, the whys, and the hows, all in one place.

What Is a Journal Club in Science?

A journal club is a series of meetings in which somebody is elected to present a research paper, its methods, and findings to a group of colleagues.

The broad goal is to stimulate discussion and ideas that the attendees may apply to their own work. Alternatively, someone may choose a paper because it’s particularly impactful or ingenious.

Usually, the presenter alternates per a rota, and attendance may be optional or compulsory.

The presenter is expected to choose, analyze, and present the paper to the attendees with accompanying slides.

The presentation is then followed by a discussion of the paper by the attendees. This is usually in the form of a series of questions and answers directed toward the presenter. Ergo , the presenter is expected to know and understand the paper and subject area to a moderate extent.

Why Have a Journal Club?

I get it. You’re a busy person. There’s a difficult research problem standing between you and your next tenure.

Why bother spending the time and energy participating in a series of meetings that don’t get you closer to achieving your scientific goals?

The answer: journal club does get you closer to achieving your scientific goals!

But it does this in indirect ways that subtly make you a better scientist. For example:

- It probably takes you out of your comfort zone.

- It makes you a better communicator.

- It makes you better at analyzing data.

- It improves your ability to critique research.

- It makes you survey relevant literature.

- It exposes you and your audience to new concepts.

- It exposes your audience to relevant literature.

- It improves the reading habits of you and your audience.

- It gets clever people talking to each other.

- It gives people a break from practical science.

It also provides a platform for people to share ideas based on their collective scientific experience. And every participant has a unique set of skills. So every participant has the potential to provide valuable insight.

This is what a good journal club should illicit.

Think of journal club as reading a book. It’s going to enrich you and add beneficially to the sum of your mental furniture, but you won’t know how until you’ve read it.

Need empirical evidence to convince you? Okay!

In 1988 a group of medical interns was split into two groups. One received journal club teaching and the other received a series of seminars. Approximately 86% of the journal club group reported improved reading habits. This compares to 0% in the group who received seminar-based teaching. [1]

Journal Club Template Structure

So now you know what journal club is, you might wonder, “how is it organized and structured?”

That’s what the rest of this article delves into. If you’re in a rush and need to head back to the lab, here’s a graphical summary (Figure 1).

Nobody likes meetings that flounder around and run over time. And while I have no data to prove it, I reckon people take less away from such meetings. Here’s a basic journal club template that assumes you are the presenter.

Introduce the Paper, Topic, Journal, and Authors

Let your audience know what you will be talking about before diving right in. Remember that repetition (of the important bits) can be a good thing.

Introducing the journal in which the paper is published will give your audience a rough idea of the prestige of the work.

And introducing the authors and their respective institutes gives your audience the option of stowing this information away and following it up with further reading in their own time.

Provide a Reason Why You Chose the Paper

Have the authors managed to circumvent sacrificing animals to achieve a goal that traditionally necessitated animal harm? Have the authors repurposed a method and applied it to a problem it’s not traditionally associated with? Is it simply a monumental feat of work and success?

People are probably more likely to listen and engage with you if they know why, in all politeness, you have chosen to use their time to talk about a given paper.

It also helps them focus on the relevant bits of your presentation and form cogent questions.

Orally Present Key Findings and Methods of the Paper

Simple. Read the paper. Understand it. Make some slides. Present.

Okay, there are a lot of ways you can get this wrong and make a hash of it. We’ll tell you how to avoid these pitfalls later on.

But for now, acknowledge that a journal club meeting starts with a presentation that sets up the main bit of it—the discussion.

Invite Your Audience to Participate in a Discussion

The discussion is the primary and arguably most beneficial component of journal club since it gives the audience a platform to share ideas. Ideas formulated by their previous experience.

And I’ve said already that these contributions are unique and have the potential to be valuable to your work.

That’s why the discussion element is important.

Their questions might concur and elaborate on the contents of the paper and your presentation of it.

Alternatively, they might disagree with the methods and/or conclusions. They might even disagree with your presentation of technical topics.

Try not to be daunted, however, as all of this ultimately adds to your knowledge, and it should all be conducted in a constructive spirit.

Summarize the Meeting and Thank Your Audience for Attending

There’s no particularly enlightening reason as to why to do these things. Summarizing helps people come away from the meeting feeling like it was a positive and rewarding thing to attend.

And thanking people for their time is a simple courtesy.

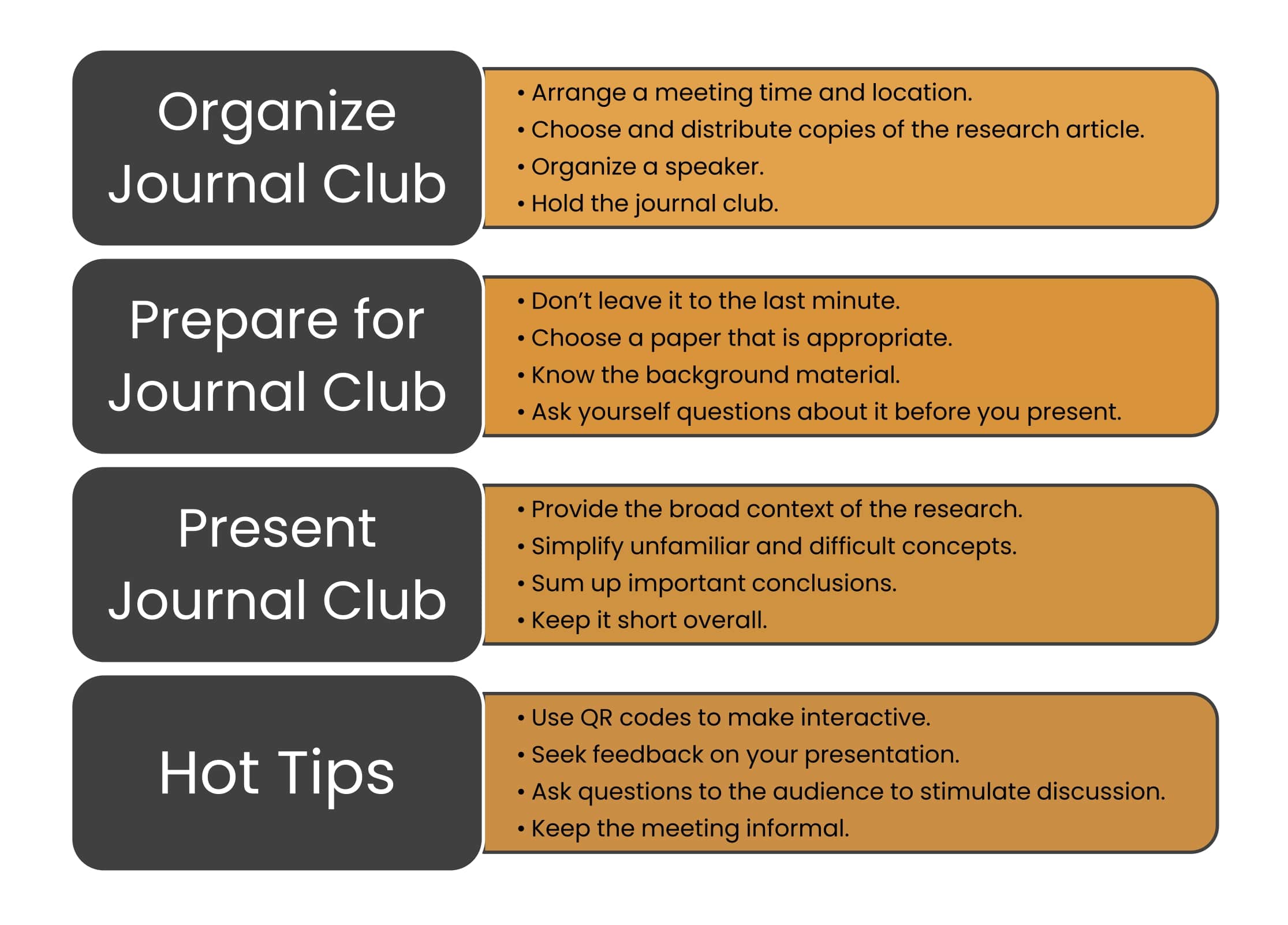

How Do You Organize It?

Basic steps if you are the organizer.

Okay, we’ve just learned what goes into speaking at the journal club. But presenter or not, the responsibility of organizing it might fall to you.

So, logistically , how do you prepare a journal club? Simply follow these 5 steps:

- Distribute copies of the research article to potential participants.

- Arrange a meeting time and location.

- Organize a speaker.

- Hold the journal club.

- Seek feedback on the quality of the meeting.

Apart from point 5, these are fairly self-explanatory. Regarding point 5, feedback is essential to growing as a scientist and presenter. The easiest way to seek feedback is simply to ask.

Alternatively, you could create a form for all the meetings in the series and ask the audience to complete and return it to you.

Basic Steps If You Are the Speaker

If somebody has done all the logistics for you, great! Don’t get complacent, however.

Why not use the time to elevate your presentation to make your journal club contribution memorable and beneficial?

Don’t worry about the “hows” because we’re going to elaborate on these points, but here are 5 things you can do to ace your presentation:

- Don’t leave it to the last minute.

- Know your audience.

- Keep your presentation slides simple.

- Keep your audience engaged.

- Be open to questions and critiques.

Regarding point 1, giving yourself sufficient time to thoroughly read the article you have chosen to present ensures you are familiar with the material in it. This is essential because you will be asked questions about it. A confident reply is the foundation of an enlightening discussion.

Regarding point 3, we’re going to tell you exactly how to prepare effective slides in its own section later. But if you are in a rush, minimize the use of excessive text. And if you provide background information, stick to diagrams that give an overview of results from previous work. Remember: a picture speaks louder than a thousand words.

Regarding point 4, engagement is critical. So carry out a practice run to make sure you are happy with the flow of your presentation and to give you an idea of your timing. It is important to stick to the time that is allotted for you.

This provides good practice for more formal conference settings where you will be stopped if you run over time. It’s also good manners and shows consideration for the attendees.

And regarding point 5, as the presenter, questions are likely to be directed toward you. So anticipate questions from the outset and prepare for the obvious ones to the best of your ability.

There’s a limit to everyone’s knowledge, but being unable to provide any sort of response will be embarrassing and make you seem unprepared.

Anticipate that people might also disagree with any definitions you make and even with your presentation of other people’s data. Whether or not you agree is a different matter, but present your reasons in a calm and professional manner.

If someone is rude, don’t rise to it and respond calmly and courteously. This shouldn’t happen too often, but we all have “those people” around us.

How Do You Choose a Journal Club Paper?

Consider the quality of the journal.

Just to be clear, I don’t mean the paper itself but the journal it’s published in.

An obscure journal is more likely to contain science that’s either boring, sloppy, wrong, or all three.

And people are giving up their time and hope to be stimulated. So oblige them!

Journal impact factor and rejection rate (the ratio of accepted to rejected articles) can help you decide whether a paper is worth discussing.

Consider the Impact and Scope of the Paper

Similar to the above, but remember, dross gets published in high-impact journals too. Hopefully, you’ve read the paper you want to present. But ask yourself what makes this particular paper stand out from the millions of others to be worth presenting.

Keep It Relevant and Keep It Interesting

When choosing a paper to present, keep your audience in mind. Choose something that is relevant to the particular group you are presenting to. If only you and a few other people understand the topic, it can come off as elitist.

How Do You Break Down and Present the Paper?

Know and provide the background material.

Before you dive into the data, spend a few minutes talking about the context of the paper. What did the authors know before they started this work? How did they formulate their hypothesis? Why did they choose to address it in this way?

You may want to reference an earlier paper from the same group if the paper represents a continuation of it, but keep it brief.

Try to explain how this paper tackles an unanswered question in the field.

Understand the Hypothesis and Methods of the Paper

Make a point of stating the hypothesis or main question of the paper, so everyone understands the goal of the study and has a foundation for the presentation and discussion.

Everyone needs to start on the same foot and remain on the same page as the meeting progresses.

Turn the Paper into a Progression of Scientific Questions

Present the data as a logical series of questions and answers. A well-written paper will already have done the hard work for you. It will be organized carefully so that each figure answers a specific question, and each new question builds on the answer from the previous figure.

If you’re having trouble grasping the flow of the paper, try writing up a brief outline of the main points. Try putting the experiments and conclusions in your own words, too.

Feel free to leave out parts of the figures that you think are unnecessary, or pull extra data from the supplemental figures if it will help you explain the paper better.

Ask Yourself Questions about the Paper Before You Present

We’ve touched on this already. This is to prepare you for any questions that are likely to be asked of you. When you read the paper, what bits didn’t you understand?

Simplify Unfamiliar and Difficult Concepts

Not everyone will be familiar with the same concepts. For example, most biologists will not have a rigorous definition of entropy committed to memory or know its units. The concept of entropy might crop up in a biophysics paper, however.

Put yourself in the audience’s shoes and anticipate what they might not fully understand given their respective backgrounds.

If you are unsure, ask them if they need a definition or include a short definition in your slides.

Sum Up Important Conclusions

After you’ve finished explaining the nitty-gritty details of the paper, conclude your presentation of the data with a list of significant findings.

Every conclusion will tie in directly to proving the major conclusion of the paper. It should be clear at this point how the data answers the main question.

How Do You Present a Journal Club Powerpoint?

Okay, so we’ve just gone through the steps required to break down a paper to present it effectively at journal club. But this needs to be paired with a PowerPoint presentation, and the two bridged orally by your talk. How do you ace this?

Provide Broad Context to the Research

We are all bogged down by minutia and reagents out of necessity.

Being bogged down is research. But it helps to come up for air. Ultimately, how will the research you are about to discuss benefit the Earth and its inhabitants when said research is translated into actual products?

Science can be for its own sake, but funded science rarely is. Reminding the journal club audience of the widest aims of the nominated field provides a clear starting point for the discussion and shows that you understand the efficacy of the research at its most basic level.

The Golden Rule: A Slide per Minute

Remember during lectures when the lecturer would open PowerPoint, and you would see, with dismay, that their slides went up to 90 or something daft? Then the last 20 get rushed through, but that’s what the exam question ends up being based on.

Don’t be that person!

A 10-15 minute talk should be accompanied by? 10-15 slides! Less is more.

Be Judicious about the Information You Choose to Present

If you are present everything in the paper, people might as well just read it in their own time, and we can call journal club off.

Try to abstract only the key findings. Sometimes technical data is necessary for what you are speaking about because their value affects the efficacy of the data and validity of the conclusions.

Most of the time, however, the exact experimental conditions can be left out and given on request. It’s good practice to put all the technical data that you anticipate being asked for in a few slides at the end of your talk.

Use your judgment.

Keep the Amount of Information per Slide Low for Clarity

Your audience is already listening to you and looking at the slides, so they have a limited capacity for what they can absorb. Overwhelming them with visual queues and talking to them will disengage them.

Have only a few clearly related images that apply directly to what you speaking about at the time. Annotate them with the only key facts from your talk and develop the bigger picture verbally.

This will be hard at first because you must be on the ball and confident with your subject area and speaking to an audience.

And definitely use circles, boxes, and arrows to highlight important parts of figures, and add a flowchart or diagram to explain an unfamiliar method.

Keep It Short Overall

The exact length of your meeting is up to you or the organizer. A 15-minute talk followed by a 30-minute discussion is about the right length, Add in tea and coffee and hellos, and you get to an hour.

We tend to speak at 125-150 words per minute. All these words should not be on your slides, however. So, commit a rough script to memory and rehearse it.

You’ll find that the main points you need to mention start to stand out and fall into place naturally. Plus, your slides will serve as visual queue cards.

How Do You Ask a Question in Journal Club?

A well-organized journal club will have clear expectations of whether or not questions should be asked only during the discussion, or whether interruptions during the presentation are allowed.

And I don’t mean literally how do you soliloquize, but rather how do you get an effective discussion going.

Presenters: Ask Questions to the Audience

We all know how it goes. “Any questions?” Silence.

Scientists, by their very nature, are usually introverted. Any ideas they might want to contribute to a discussion are typically outweighed by the fear of looking silly in front of their peers. Or they think everyone already knows the item they wish to contribute. Or don’t want to be publicly disproven. And so on.

Prepare some questions to ask the audience in advance. As soon as a few people speak, everyone tends to loosen up. Take advantage of this.

Audience: Think About Topics to Praise or Critique

Aside from seeking clarification on any unclear topics, you could ask questions on:

- Does the data support the conclusions?

- Are the conclusions relevant?

- Are the methods valid?

- What are the drawbacks and limitations of the conclusions?

- Are there better methods to test the hypothesis?

- How will the research be translated into real-world benefits?

- Are there obvious follow-up experiments?

- How well is the burden of proof met?

- Is the data physiologically relevant?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

How to Keep It Fun

Make it interactive.

Quizzes and polls are a great way to do this! And QR codes make it really easy to do on-the-fly. Remember, scientists, are shy. So why not seek their participation in an anonymized form?

You could poll your audience on the quality of the work. You could make a fun quiz based on the material you’ve covered. You could do a live “what happened next?” You could even get your feedback this way. Here’s what to do:

- Create your quiz or poll using Google forms .

- Make a shareable link.

- Paste the link into a free QR code generator .

- Put the QR code in the appropriate bit of your talk.

Use Multimedia

Talking to your audience without anything to break it up is a guaranteed way of sending them all to sleep.

Consider embedding demonstration videos and animations in your talk. Or even just pausing to interject with your own anecdotes will keep everyone concentrated on you.

Keep It Informal

At the end of the day, we’re all scientists. Perhaps at different stages of our careers, but we’ve all had similar-ish trajectories. So there’s no need for haughtiness.

And research institutes are usually aggressively casual in terms of dress code, coffee breaks, and impromptu chats. Asking everyone to don a suit won’t add any value to a journal club.

Your Journal Club Toolkit in Summary

Anyone can read a paper, but the value lies in understanding it and applying it to your own research and thought process.

Remember, journal club is about extracting wisdom from your colleagues in the form of a discussion while disseminating wisdom to them in a digestible format.

Need some inspiration for your journal club? Check out the online repositories hosted by PNAS and NASPAG to get your juices flowing.

We’ve covered a lot of information, from parsing papers to organizational logistics, and effective presentation. So why not bookmark this page so you can come back to it all when it’s your turn to present?

While you’re here, why not ensure you’re always prepared for your next journal club and download bitesize bio’s free journal club checklist ?

And if you present at journal club and realize we’ve left something obvious out. Get in touch and let us know. We’ll add it to the article!

- Linzer M et al . (1988) Impact of a medical journal club on house-staff reading habits, knowledge, and critical appraisal skills . JAMA 260 :2537–41

Forgot your password?

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive mail with link to set new password.

Back to login

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 12 May 2021

Good presentation skills benefit careers — and science

- David Rubenson 0

David Rubenson is the director of the scientific-communications firm No Bad Slides ( nobadslides.com ) in Los Angeles, California.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A better presentation culture can save the audience and the larger scientific world valuable time and effort. Credit: Shutterstock

In my experience as a presentation coach for biomedical researchers, I have heard many complaints about talks they attend: too much detail, too many opaque visuals, too many slides, too rushed for questions and so on. Given the time scientists spend attending presentations, both in the pandemic’s virtual world and in the ‘face-to-face’ one, addressing these complaints would seem to be an important challenge.

I’m dispirited that being trained in presentation skills, or at least taking more time to prepare presentations, is often not a high priority for researchers or academic departments. Many scientists feel that time spent improving presentations detracts from research or clocking up the numbers that directly affect career advancement — such as articles published and the amount of grant funding secured. Add in the pressing, and sometimes overwhelming, bureaucratic burdens associated with working at a major biomedical research institute, and scientists can simply be too busy to think about changing the status quo.

Improving presentations can indeed be time-consuming. But there are compelling reasons for researchers to put this near the top of their to-do list.

You’re probably not as good a presenter as you think you are

Many scientists see problems in colleagues’ presentations, but not their own. Having given many lousy presentations, I know that it is all too easy to receive (and accept) plaudits; audiences want to be polite. However, this makes it difficult to get an accurate assessment of how well you have communicated your message.

Why your scientific presentation should not be adapted from a journal article

With few exceptions, biomedical research presentations are less effective than the speaker would believe. And with few exceptions, researchers have little appreciation of what makes for a good presentation. Formal training in presentation techniques (see ‘What do scientists need to learn?’) would help to alleviate these problems.

Improving a presentation can help you think about your own research

A well-designed presentation is not a ‘data dump’ or an exercise in advanced PowerPoint techniques. It is a coherent argument that can be understood by scientists in related fields. Designing a good presentation forces a researcher to step back from laboratory procedures and organize data into themes; it’s an effective way to consider your research in its entirety.

You might get insights from the audience

Overly detailed presentations typically fill a speaker’s time slot, leaving little opportunity for the audience to ask questions. A comprehensible and focused presentation should elicit probing questions and allow audience members to suggest how their tools and methods might apply to the speaker’s research question.

Many have suggested that multidisciplinary collaborations, such as with engineers and physical scientists, are essential for solving complex problems in biomedicine. Such innovative partnerships will emerge only if research is communicated clearly to a broad range of potential collaborators.

It might improve your grant writing

Many grant applications suffer from the same problem as scientific presentations — too much detail and a lack of clearly articulated themes. A well-designed presentation can be a great way to structure a compelling grant application: by working on one, you’re often able to improve the other.

It might help you speak to important, ‘less-expert’ audiences

As their career advances, it is not uncommon for scientists to increasingly have to address audiences outside their speciality. These might include department heads, deans, philanthropic foundations, individual donors, patient groups and the media. Communicating effectively with scientific colleagues is a prerequisite for reaching these audiences.

Collection: Conferences

Better presentations mean better science

An individual might not want to spend 5 hours improving their hour-long presentation, but 50 audience members might collectively waste 50 hours listening to that individual’s mediocre effort. This disparity shows that individual incentives aren’t always aligned with society’s scientific goals. An effective presentation can enhance the research and critical-thinking skills of the audience, in addition to what it does for the speaker.

What do scientists need to learn?

Formal training in scientific presentation techniques should differ significantly from programmes that stress the nuances of public speaking.

The first priority should be to master basic presentation concepts, including:

• How to build a concise scientific narrative.

• Understanding the limitations of slides and presentations.

• Understanding the audience’s time and attention-span limitations .

• Building a complementary, rather than repetitive, relationship between what the speaker says and what their slides show.

The training should then move to proper slide design, including:

• The need for each slide to have an overarching message.

• Using slide titles to help convey that message.

• Labelling graphs legibly.

• Deleting superfluous data and other information.

• Reducing those 100-word text slides to 40 words (or even less) without losing content.

• Using colour to highlight categories of information, rather than for decoration.

• Avoiding formats that have no visual message, such as data tables.

A well-crafted presentation with clearly drawn slides can turn even timid public speakers into effective science communicators.

Scientific leaders have a responsibility to provide formal training and to change incentives so that researchers spend more time improving presentations.

A dynamic presentation culture, in which every presentation is understood, fairly critiqued and useful for its audience, can only be good for science.

Nature 594 , S51-S52 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01281-8

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Related Articles

- Conferences and meetings

- Research management

Overcoming low vision to prove my abilities under pressure

Career Q&A 28 MAR 24

How a spreadsheet helped me to land my dream job

Career Column 28 MAR 24

Maple-scented cacti and pom-pom cats: how pranking at work can lift lab spirits

Career Feature 27 MAR 24

China promises more money for science in 2024

News 08 MAR 24

One-third of Indian STEM conferences have no women

News 15 NOV 23

How remote conferencing broadened my horizons and opened career paths

Career Column 04 AUG 23

Superconductivity case shows the need for zero tolerance of toxic lab culture

Correspondence 26 MAR 24

Cuts to postgraduate funding threaten Brazilian science — again

The beauty of what science can do when urgently needed

Career Q&A 26 MAR 24

Expression of Interest – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions – Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 (MSCA-PF)

Academic institutions in Brittany are looking for excellent postdoctoral researchers willing to apply for a Marie S. Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship.

France (FR)

Plateforme projets européens (2PE) -Bretagne

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecological and Evolutionary Modeling

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecosystem Ecology linked to IceLab’s Center for modeling adaptive mechanisms in living systems under stress

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Faculty Positions in Westlake University

Founded in 2018, Westlake University is a new type of non-profit research-oriented university in Hangzhou, China, supported by public a...

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Postdoctoral Fellowships-Metabolic control of cell growth and senescence

Postdoctoral positions in the team Cell growth control by nutrients at Inst. Necker, Université Paris Cité, Inserm, Paris, France.

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

Inserm DR IDF Paris Centre Nord

Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine on Open Recruitment of Medical Talents and Postdocs

Director of Clinical Department, Professor, Researcher, Post-doctor

The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.19(9); 2019 Sep

Seven tips for giving an engaging and memorable presentation

Effective and memorable presentations should be fun, and informative for the presenters and the learners. Engaging presenters stimulate connections with the audience. Excellent presentations not only provide information, but also give opportunities to apply new ideas during and after the talk to ‘real-life’ situations, and add relevant ‘take-home’ messages. 1 In this article we highlight educational techniques that can be used to enhance the impact of a presentation. Although all these techniques can be incorporated in the modified form into large plenary lectures, we suggest that the ‘think-pair-share’, ‘role-playing’, and ‘flipped classroom’ techniques may be more effective in smaller classroom settings.

Tip 1: Know your audience—before and during your talk

Every audience has a different level of interest, knowledge, and experience. A presentation about asthma should be different when given to patients compared with intensivists. The presenter should have a clear a priori idea of why the learners are coming to this lecture, what may motivate them, and what would be valuable to them . Whenever feasible, an assessment of the audience's needs is helpful for the presenter to focus on meaningful points. Sometimes needs-based assessments are prepared in advance, depending on the lecture or meeting, and this information may be available from the organisers of the meeting. However, if the information is not available beforehand, there are methods for collecting real-time assessments that are themselves engaging to learners. Another benefit of engaging audiences in this way is that an audience response system (ARS) can provide real-time feedback before, during, and after a presentation. 2 ARS can range from low-technology (hand raising), to newer generation ‘iClicker’ devices, or online websites such as Poll Everywhere, which can also be used to collect free-text responses. The audience's responses can help learners reinforce the importance of the topic, and provide a gauge for the presenter to customise subsequent information. Furthermore, research has shown that incorporation of multiple-choice questions to allow for ‘test-taking’ is an effective way of solidifying new knowledge. 2 Advantages of web-based ARS programs are that they are free, user-friendly, and accessible by various mobile devices. The potential disadvantages are reliability of Wi-Fi or cell phone carrier connectivity in a lecture theatre. In the absence of connectivity, an invitation to raise hands can engage participants, although without anonymity.

Tip 2: Tell a story

Stories connect people. A story that is personal to the speaker can evoke memories that are relatable and add concrete meaning to the presentation. 3 Consider starting your presentation with a story that shows why the topic is important to you. In addition, stories focus the audience on the speaker, rather than a slideshow. Even when the stories are not based on personal experiences, they can invoke learners to imagine themselves in similar situations applying knowledge to solve a problem. Descriptions of clinical cases that focus on initial presentations of patients allow learners to imagine seeing that patient and stimulate critical thinking. Experiencing the case vicariously makes the learning more memorable.

Tip 3: Trigger videos

Trigger videos are short (ideally 30 s to 3 min) audiovisual clips that represent a case or problem. Videos can be created using a handheld video recorder or smartphone, and edited using movie-editing software. Alternatively, videos can be found online and incorporated into presentations with appropriate attributions. Chosen well, trigger videos can present a thought-provoking dilemma that encourages discussion and debate. 4 They can alter the dynamics of a presentation. Success requires careful linking or embedding the videos into the presentation, making sure they play on the computer and projector, and confirming appropriate loudness of the audio settings.

Tip 4: Think-pair-share

When introducing a novel concept to a small group, consider using the ‘think-pair-share’ technique. In this technique, learners first think quietly about the challenging idea, then pair with neighbours to discuss, and then share their collective thoughts with the audience. 5 This technique gives the audience time to pause, think, and reflect on educational content. Encouraging the audience to come to work with the knowledge in a collaborative way incorporates experiential learning into your presentation. To be successful, allow for extra time in the presentation, ensure the audience's seating arrangement is conducive to small conversations, and display summarised ideas for referencing throughout the presentation. 5 , 6

Tip 5: Role play

When presenting an abstract concept that is controversial or thought-provoking, the use of scripted actors can be helpful. Both exemplary and poor examples can be demonstrated for topics such as obtaining informed consent, speaking up about safety concerns, or giving difficult feedback. Similarly, small group role-play can allow audience members to practice and experiment with actions and language with their peers. 7 The instructor should introduce the exercise in a way that helps assure psychological safety among learners, with an emphasis on deliberate practice rather than perfect performance.

Tip 6: ‘Flip’ the classroom

In situations where homework is assigned, consider ‘flipping’ the classroom experience where work is prepared by the learners before the teaching session. Preparatory work can comprise reading material or watching videos of lectures or demonstrations. This allows for more active collaborative learning, for example learners can solve a diagnostic challenge together, debate the pros and cons of a controversial topic, or practice skills. 8 The classroom experience is enriched by the interaction of many learners, rather than the perspective of a single presenter.

Tip 7: Applying the ‘take-home message’

Many are familiar with the framework of ‘ tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then summarise what you just said. ’ We advocate an additional component in the conclusion, where learners are challenged to commit to a change in their behaviour as a result of something they just learned: ‘ What is something you can do differently and better tomorrow or with your next patient as a result of this presentation? ’ Incorporating this question in the evaluation of a presentation can help facilitate behaviour change by having the learners write an example. Similarly, incentives can be offered for behaviour change: ‘ We have your email addresses, and with your permission we would like to follow-up with you in 2 weeks to see if you have any stories to share about applying this new information. We'll be collecting the responses and having a raffle to select one person to receive a gift card... ’ Not only does this provide an incentive to experimentation, but it also gives valuable and often heart-warming feedback to the presenter.

Dynamic educational techniques increase the engagement of the audience. We emphasise the importance of connecting with the learners and obtaining a commitment to apply the new knowledge for change and improvement. The extent to which these techniques are used will depend on the level of audience expertise, time constraints, and access to audiovisual aids. When used, they can result in a more memorable experience for both learners and presenters.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Christine Mai MD MS-HPEd is assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and program director of the Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital. Her clinical and research interests are in simulation education and graduate medical education.

Rebecca Minehart MD MS-HPEd is assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and program director of the Obstetric Anesthesia Fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital.