Case Summary – Hypovolemic Shock & the Role of Early Volume Resuscitation

- Rapid Fluid Bolus

The term “shock” originates from the term “choc” which dates back to the 18 th century, when French army surgeon Henri Francois Le Dran coined the term to describe the loss of vital functions leading to death, which he observed often in the soldiers on which he operated. 1 About a century later, John Collins Warren reported shock as a “momentary pause in the act of death.” 1 Although our understanding of the physiology related to shock is more informed today, a diagnosis of shock still carries the same urgency that it did when Henri and John Collins practiced. While prompt treatment of shock is crucial to lowering morbidity and mortality in all types of shock, Meyer et al. showed every minute before volume resuscitation in hypovolemic shock increased the mortality risk by 5%. 2 The following hemorrhagic hypovolemic cases illustrate the positive impact that early, rapid volume resuscitation can have on patient outcomes.

Case #1: A 39-Year old Male with Haematemesis

A 39-year old male presented to the emergency department with haematemesis, jaundice and hypotension with a blood pressure of 59/22mmHg. The patient was conscious with a medical history of esophageal varices secondary to alcoholic hepatitis, previous GI bleed with banding and thrombocytopenia. Haematemesis was preceded by nausea the previous day and EMS reported 1-2L of blood lost via emesis. Upon arrival, in addition to the severe hypotension, he was tachycardic with an oxygen saturation of 95% with 3L of oxygen through a nasal cannula. His arterial blood sample had a pH of 6.60, pCO2 of 103mmHg, pO2 of 63mmHg, bicarbonate level of 10.2mEq/L, and base excess -28mEq/L.

Due to the dangerous state of hypovolemic shock, two large bore IV’s were placed and 3L of normal saline was given over the next few minutes (2L with the LifeFlow device and 1L with a pressure bag). His vitals immediately improved substantially to a blood pressure of 118/60 and pulse oximetry value of 100%. The patient’s CBC lab results came back post volume resuscitation with values of hemoglobin at 8.6g/dL and platelets at 24X10^9/L. The thrombocytopenia and anemia were treated with 10 units of red blood cells, 1 unit of platelets, and three units of fresh frozen plasma in the ER without further incidence of hypotension. The patient was transferred to the ICU and a few days later the patient underwent surgery to insert a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to reduce portal hypertension. The patient recovered back to baseline and was discharged 5 days post-operatively.

Case #2: A 60-Year old Male with Lower GI Bleed

A 60-year old male presented to the emergency department via EMS after complaining of rectal bleeding. His medical history included COPD, hypertension, diabetes and cocaine use. The patient arrived in the ED with a 17-gauge peripheral IV, blood pressure of 96/40mmHg, respiratory rate of 22, oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, and a hematocrit of 15g/dL. While awaiting packed red blood cells to arrive from the blood bank, 1L of normal saline was administered with the LifeFlow rapid infusion device. While still in hemorrhagic, hypovolemic shock, this improved his mean arterial blood pressure to 80 from 70mmHg. After the blood was transfused, the blood pressure was 86/51, and the patient was transferred to the OR to stop the rectal bleed. He recovered and was discharged with home health support 3 days post-operatively.

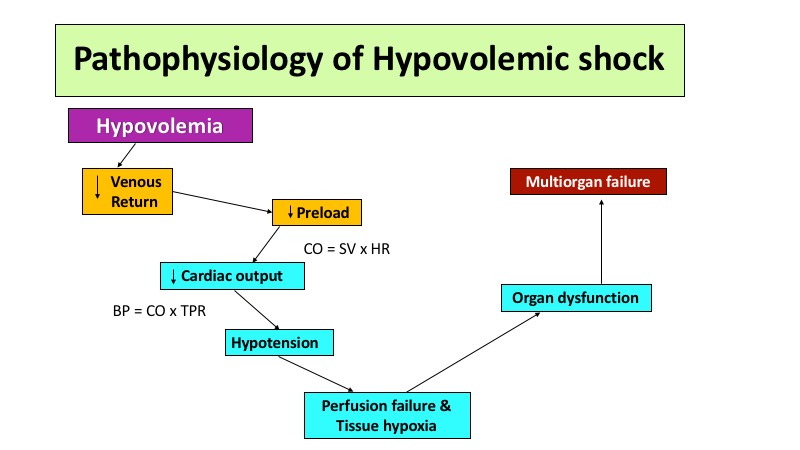

Hypovolemic shock is one of the most acute forms of shock, necessitating swift recognition and treatment. 3 Lost intravascular volume leads to decreased preload and ultimately reduced oxygen delivery. 3 Treatment recommendations include swift fluid resuscitation to replace intravascular volume, endotracheal intubation if hypoxic, and quick bleeding control if possible. 2-4 These two cases exemplify patients we often see where the progression to refractory or irreversible shock is imminent but not inevitable. With swift diagnosis and intervention we can arrest the downward spiral and stabilize the patient.

Interested in learning more about LifeFlow? Contact us .

- Frost P, Wise M. Recognition and management of the patient with shock. Acute Med . 2006;5(2):43-47.

- Meyer DE, Vincent LE, Fox EE, et al. Every minute counts: Time to delivery of initial massive transfusion cooler and its impact on mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg . 2017;83(1):19-24. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001531.

- Standl T, Annecke T, Cascorbi I, Heller AR, Sabashnikov A, Teske W. The Nomenclature, Definition and Distinction of Types of Shock. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018 Nov 9;115(45):757-768. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0757. PMID: 30573009; PMCID: PMC6323133.

- Moranville MP, Mieure KD, Santayana EM. Evaluation and Management of Shock States: Hypovolemic, Distributive, and Cardiogenic Shock. Journal of Pharmacy Practice . 2011;24(1):44-60. doi: 10.1177/0897190010388150 .

MIS-C Experience at Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital: Case reviews using specialized protocol including LifeFlow – Part 1

An empty “tank” can be bad, maybe worse than you think.

- Patient Stories

- OB Hemorrhage

- Hypotension

- Infection Control

- Pre-hospital

Subscribe to Blog & Updates

Please leave this field empty.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for subscribing!

Have questions about LifeFlow?

Want to get in touch?

Schedule a LifeFlow demo now with one of our Clinical Specialists

NurseStudy.Net

Nursing Education Site

Hypovolemic Shock Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Care Plan

Last updated on May 16th, 2022 at 05:51 pm

Hypovolemic Shock Nursing Care Plans Diagnosis and Interventions

Hypovolemic Shock NCLEX Review and Nursing Care Plans

Hypovolemic shock is a potentially fatal condition characterized by uncontrolled blood or extracellular fluid loss. It is manifested by a drop in blood volume, blood pressure, and urine output of 0.5 ml/kg/hr.

Its pathological process develops upon loss of intravascular volume, thereby decreasing blood pressure and venous return. When the intravascular volume is decreased, the physiologic response frequently results in reduced tissue perfusion and impaired cellular metabolism, both shock features.

Metabolic acidosis, which impairs mentation, can result from decreased tissue perfusion. Moreover, if hypovolemic shock persists, multiple organ failures may occur.

Signs and Symptoms of Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock develops in stages. The symptoms may vary in each stage:

- Stage 1: Loss of blood volume (0.7L), anxiety, paleness, prolonged capillary time

- Stage 2: Loss of blood volume (0.7-1.5L), tachycardia, high diastolic pressure, altered mental state, rapid heart rate, decreased urinary output

- Stage 3: Loss of blood volume (1.5-2L), decreased blood pressure, disorientation

- Stage 4: Loss of blood volume (>2L), decreased BP, lethargy, disorientation, insufficient or no urinary output, lightheadedness, shallow breathing

Other physical manifestations of hypovolemic shock include:

- Dry mucous membranes

- Decreased skin turgor

- A clammy appearance of the skin

- Jugular vein distention

Additionally, a patient in shock may be less responsive as a result of alterations in cerebral hemodynamics, which manifest as lethargy, confusion, and restlessness.

Causes of Hypovolemic Shock

The most common causes of hypovolemic shock are categorized into four etiologies:

- Renal. Renal losses of sodium and water can lead to hypovolemic shock. Hypernatremia is a condition in which increased sodium secretion occurs in conjunction with increased water secretion due to medications or diuretic use (e.g., osmosis diuresis, loop diuretics). It can also arise from water loss secondary to Diabetes insipidus, which occurs when kidney response to arginine vasopressin (AVP) is impaired.

Other renal causes:

- Tubular and interstitial diseases

- Salt wasting nephropathy

- Gastrointestinal. This is a case of absolute hypovolemia. Gastrointestinal losses have various causes, but diarrhea, external discharge, and vomiting are the most common. As a result, external and internal shifts cause inadequate tissue perfusion, precipitating shock. Moreover, dehydration, hypochloremia, hyponatremia, and hypokalemia are possible outcomes. Diarrhea-causing conditions can also result in volume loss due to poor intestinal absorption. As with vomiting, electrolyte losses via defecation are expected. Although these two processes are typically self-limiting, symptomatic and intensive care is necessary when the patient becomes hypovolemic.

Other causes of gastrointestinal etiology include:

- Nasogastric suction

- Biliary diseases

- Digestive fistula

- Skin. Excessive fluid loss can also occur when skin integrity is impaired . Exposure to hot climates can lead to extreme sweating and insensible losses, such as mouth-breathing, evaporation from the skin, and respiratory loss. Moreover, it can result in water loss of up to 1 L per hour.

Patients with a compromised skin barrier caused by burns or other skin lesions may also have a significant fluid loss, resulting in HS.

- Third Spacing. Third spacing is a phenomenon that occurs when fluid migrates to regions that are ordinarily absent of fluid. This condition can arise from pancreatitis , intestinal blockage, embolus, compromised vascular endothelium, and burn victims due to exudates and blister formation. Additionally, relative hypovolemia can occur, resulting in intestinal blockage and tissue due to the pooling of fluids.

- Intravascular volume depletion. Capillary permeability is the most prevalent cause of electrolyte shifts, resulting in large-scale fluid redistribution from blood vessels into the interstitial space. When fluid shifts occur, the body’s extracellular or intracellular fluid volume is affected.

Blood loss can also occur as a result of either relative or absolute volume loss.

- Absolute hypovolemia – occurs as a result of hypovolemia due to bleeding, gastrointestinal loss, diuresis, or diabetes insipidus

- Relative hypovolemia – occurs when fluid exits the circulatory system and enters the extravascular space.

5. Hemorrhagic. Hemorrhagic shock is a hypovolemic shock caused by blood loss and altered cellular metabolism. Moreover, it can induce hypoxia due to insufficient oxygen delivery. If hypoxia exceeds the usual threshold, insufficient perfusion to the tissues can result in tissue damage, organ malfunction, and death.

Other causes of hemorrhagic origin are:

- Mechanical trauma: Bruising as a result of major cuts or wounds, blunt traumatic injuries sustained in accidents, internal bleeding from abdominal organs

- Internal bleeding: Ruptured aneurysm, ectopic pregnancy, gastrointestinal bleeding , endometriosis, post-partum bleeding

- Exteriorization of internal bleeding

Risk Factors to Hypovolemic Shock

- Pre-existing conditions (e.g., bleeding disorders, stenosis, peritonitis , liver disorders)

- Risk of Injury (e.g., accidents, trauma, major surgeries)

- Dehydration

- Prolong hospitalization

- Medications

Diagnosis of Hypovolemic Shock

- Medical History. Obtaining a complete medical history enables evaluation of any history of trauma or recent operation. Previous gastrointestinal, renal, third spacing, and skin diseases should be considered.

- Physical Examination. Patients experiencing HS due to electrolyte imbalances and acid-base disorders typically complain of thirst, muscle cramps, and orthostatic hypotension . Hypovolemic shock, in severe cases, can result in coronary ischemia due to insufficient oxygen delivery, manifesting as abdominal and chest pain . While excessive bleeding is instantly noticeable, internal bleeding may not be.

Other tests include:

- Blood tests

- Echocardiogram

- Venous oximetry

- Lactic acid levels

- Central Venous Pressure (CVP)

- Sodium determination

Treatment of Hypovolemic Shock

- Intravenous fluid therapy. One of the primary goals of addressing HS is restoring fluid loss. Fluid resuscitation remains the therapy of choice to address hypoperfusion and improve oxygen delivery. Crystalloid infusions (isotonic solutions containing electrolytes) are excellent for rapidly restoring tissue perfusion. Fluids should be administered at a fast rate and at sufficient volume. As a result of this procedure, the clinical response can be re-evaluated continuously.

- Bleeding control. For severe bleeding, administration of blood components (e.g., blood plasma, red blood cell, platelet) may be necessary. Applying tight dressings, elevating the extremity, and additional pressure can help reduce bleeding.

- Catheterization. Set up two IV cannulas with a large-bore needle (16 gauge or more).

- Treatment of any underlying condition. The physician may address underlying disorders that contribute to hypovolemic shocks, such as gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, vomiting), bleeding, and dehydration .

- Oxygen therapy

Prevention of Hypovolemic Shock

- Early recognition of signs and symptoms. However, it is important to note that there are cases when the healthcare team may not note any warning signs of an impending hypovolemic shock. The symptoms may appear after the patient has developed the condition.

- For individuals with pre-existing conditions, routinely monitor oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and pulse rate

- Maintain adequate ventilation and fluid intake.

- Seek medical treatment and control bleeding in the event of severe trauma.

Hypovolemic Shock Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing care plan for hypovolemic shock 1.

Decreased Cardiac Output

Nursing Diagnosis: Decreased Cardiac Output related to changes in heart rate and breathing, reduced ventricular filling (preload), a 30 percent or more significant loss in fluid volume, and late unexplained volume depletion secondary to hypovolemic shock as evidenced by low oxygen content in the blood, acidosis, capillary refill time of more than 3 seconds, dysrhythmias of the heart, a shift in one’s level of consciousness, icy, and clammy skin, reduced urinary output (less than 30 ml per hour), reduced peripheral pulses, reduced pulse and blood pressure, and tachycardia.

Desired Outcome: The patient will maintain adequate cardiac output, as evidenced by peripheral solid pulses, systolic blood pressure within 20 mm Hg of baseline, heart rate 60 to 100 beats per minute with a regular rhythm, urinary output 30 ml/hr or more significant, warm and dry skin, and an average level of consciousness.

Nursing Care Plan for Hypovolemic Shock 2

Deficient Fluid Volume

Nursing Diagnosis: Deficient Fluid Volume related to active excessive fluid loss, such as abnormal bleeding, diarrhea, increased urination, unusual drainage, internal fluid transitions, insufficient fluid consumption or severe dehydration, regulatory mechanism breakdown, or trauma secondary to hypovolemic shock as evidenced by capillary refill time higher than three seconds, variations in consciousness, cool or sweaty skin, significantly reduced skin turgidity, lightheadedness, dry mucous membranes, extreme thirst, pulse pressure narrowing, postural hypotension, and palpitations.

Desired Outcome: The patient will be normovolemic, as demonstrated by a heart rate of 60 to 100 heartbeats per minute, a systolic blood pressure of equal or greater to 90 mm Hg, the apparent lack of orthostasis, an urine output greater than 30ml per hour and natural skin turgidity.

Nursing Care Plan for Hypovolemic Shock 3

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion

Nursing Diagnosis: Ineffective Tissue Perfusion related to significantly reduced stroke volume, diminished preload, lowered venous return, and significant blood loss secondary to hypovolemic shock as evidenced by cool, shivery fair-skinned color, cyanosis, deferred capillary refill, lightheadedness, superficial respirations, and a weak pulse.

Desired Outcome: As evidenced by dry and warm skin, current and potent peripheral pulses, vitals within the patient’s healthy range, regular intake and output, total lack of edema , standard ABGs, alert loss of consciousness, and absence of breathing difficulties, the patient will preserve optimum tissue perfusion to vital organs.

Nursing Care Plan for Hypovolemic Shock 4

Nursing Diagnosis: Anxiety related to alterations in health status, apprehension about death, and a distinctive environment secondary to hypovolemic shock as evidenced by uneasiness, irritability, impaired concentration, increased awareness, increased questioning, sympathetic arousal, and articulated anxiety.

Desired Outcomes:

- The patient will define a decrease in his or her level of anxiety.

- The patient will employ appropriate coping strategies.

Nursing Care Plan for Hypovolemic Shock 5

Risk for Impaired Gas Exchange

Nursing Diagnosis: Impaired Gas Exchange related to alterations in the oxygen-carbon dioxide stability secondary to hypovolemic shock. As a risk nursing diagnosis, Risk for Impaired Gas Exchange is entirely unrelated to any signs and symptoms since it has not yet developed in the patient, and safety precautions will be initiated instead.

- The patients will maintain optimal gas exchange as demonstrated by standard mental health status, unlabored respiratory rate of 12-20 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation results within average limits, venous gas within standard parameters, and patient’s baseline heart rate.

- The patient has clear lung fields and no signs of respiratory depression .

- The patient expresses his or her comprehension of oxygen and other treatment strategies.

- The patient takes part in methods for improving oxygen saturation and in a management regimen appropriate for his or her level of capability or condition.

- The patient shows signs of resolution or lack of respiratory failure symptoms.

Nursing References

Ackley, B. J., Ladwig, G. B., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M. R., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnoses handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Gulanick, M., & Myers, J. L. (2022). Nursing care plans: Diagnoses, interventions, & outcomes . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Ignatavicius, D. D., Workman, M. L., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2018). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for interprofessional collaborative care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Silvestri, L. A. (2020). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Disclaimer:

Please follow your facilities guidelines, policies, and procedures.

The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes.

This information is intended to be nursing education and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Evidence and practice

Pathophysiology and treatment of hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock, rebecca summers phd researcher, swansea university, swansea, wales.

• To familiarise yourself with the pathophysiology of hypovolaemia

• To recognise the signs and symptoms of hypovolaemic shock

• To refresh your knowledge of the treatment pathways for hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock

Hypovolaemia involves a fall in circulatory volume resulting from a loss of blood, plasma and/or plasma fluid, which is caused by internal or external haemorrhage. In turn, hypovolaemic shock occurs as a result of insufficient oxygen supply and is associated with significant mortality. Therefore, it is essential that nurses have a comprehensive understanding of the presentation, progression and treatment of hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock. This article details the physiology and development of hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock, and uses a case study to demonstrate an appropriate assessment and treatment pathway.

Nursing Standard . doi: 10.7748/ns.2020.e10675

This article has been subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software

None declared

Summers R (2020) Pathophysiology and treatment of hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock. Nursing Standard. doi: 10.7748/ns.2020.e10675

Published online: 10 February 2020

blood - blood loss - clinical - clinical skills - emergency care - haemorrhage - intravenous therapy - nursing care - signs and symptoms - trauma - urgent care

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

03 April 2024 / Vol 39 issue 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Pathophysiology and treatment of hypovolaemia and hypovolaemic shock

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Michael Haslam and Edwin Rios

Mrs. L is a 72-year-old woman who was admitted to the emergency department after she fell down the stairs of her apartment. Upon assessment, she was diaphoretic and pale and has diminished pulses in her bilateral lower extremities. She complained of 8/10 pain in her pelvic region and upon palpation, her pelvic was found to be unstable. Her vital signs upon admission were: temperature of 97.8, RR of 26, HR of 148, and a BP of 74/40. Laboratory values were Hgb of 6.8, Hct of 22.6%, BUN of 28, creatinine of 1.4, and a serum lactate of 6.8 mmol/L. Her ABG’s showed metabolic acidosis. A pelvic CT scan revealed an open book fracture. She was admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of pelvic fracture and hemorrhage where she received fluid resuscitation and multiple units of packed RBC’s. After surgical repair and stabilization of her pelvis she remained in the ICU on a ventilator and was hemodynamically stable. Her vital signs post-op day 1 were: temperature of 98.8, RR 12 (ventilated), HR 84 , and a BP of 108/64. Attempts at weaning Mrs. L off the ventilator have been unsuccessful and she remained in the ICU on the ventilator. By post-op day 3, Mrs. L is extubated successfully. The following morning, Mrs. L’s family reported that she is growing increasingly agitated and had been pulling at the IV lines. Her vital signs revealed that she was going into septic shock. Mrs. L was then reintubated and fluid resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated. She was started on vasopressors because a satisfactory BP could not be achieved. Mrs. L is now unable to follow commands and unresponsive to painful stimuli. On post-op day 7, Mrs. L goes into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The physician and family discuss options for her future care, and the option of DNR and withdrawal of life support is discussed with the family.

- Mrs. L’s ARDS resulted from her Hypovolemic and septic shock. What are the nursing interventions and goals for managing hypovolemic and septic shock?

- What are the nurse’s roles regarding the conversation the family had with the physician about DNR and withdrawal of life support?

- If life support is removed and a DNR is put in place, what are the goals for care?

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

5 Hypovolemic Shock Nursing Care Plans

Utilize this comprehensive nursing care plan and management guide to provide effective care for patients experiencing hypovolemic shock . Gain valuable insights on nursing assessment , interventions, goals, and nursing diagnosis specifically tailored for hypovolemic shock in this guide.

Table of Contents

What is hypovolemic shock, nursing problem priorities, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing goals, 1. managing decrease in cardiac output, 2. improving deficiencies in fluid volume, 3. improving cardiac tissue perfusion, 4. monitoring and preventing complications, 5. reducing anxiety and providing emotional support, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, recommended resources.

Hypovolemic shock , characterized by decreased intravascular volume, is a medical condition resulting from blood loss, leading to reduced cardiac output and inadequate tissue perfusion . It can be caused by external fluid losses, such as traumatic blood loss, or internal fluid shifts, like severe dehydration or edema. Symptoms vary based on the severity of fluid or blood loss, but all symptoms of shock require immediate medical treatment. Hypovolemic shock occurs when there is a reduction in intravascular volume by 15% to 30%, representing a loss of approximately 750 to 1,500 mL of blood in a 70-kg person. This reduction in intravascular volume leads to decreased venous return, decreased ventricular filling, decreased stroke volume, decreased cardiac output , and ultimately, inadequate tissue perfusion.

The primary objectives in treating hypovolemic shock are to restore intravascular volume, redistribute fluid, and address the underlying cause of fluid loss. These goals are typically addressed concurrently to reverse the progression of inadequate tissue perfusion.

Nursing Care Plans & Management

Nursing care management for patients with hypovolemic shock involves rapid assessment to determine the cause and severity of hypovolemia, administering intravenous fluids for volume resuscitation, closely monitoring vital signs and perfusion parameters, using invasive hemodynamic monitoring when needed, providing oxygen therapy and respiratory support, addressing the underlying cause of hypovolemia, and collaborating with the healthcare team for timely interventions and adjustments.

The following are the nursing priorities for patients with hypovolemic shock:

- Monitoring vital signs and perfusion parameters. Continuous assessment and monitoring of vital signs and perfusion parameters (skin color, temperature, capillary refill time, and urine output) are essential in determining the patient’s hemodynamic status and response to therapeutic management.

- Fluid resuscitation. This is to restore blood volume, enhance cardiac output, and improve tissue perfusion. Close monitoring of the patient’s fluid balance , including input and output , is crucial in preventing fluid overload or under-resuscitation.

- Oxygen administration and providing airway support. Maintaining adequate oxygenation and tissue perfusion by assessing oxygen saturation, providing oxygen therapy, and assisting with airway management as needed.

- Achieving hemodynamic stability . Collaborating with the healthcare team to monitor invasive hemodynamic parameters (such as central venous pressure, and arterial blood pressure ) if indicated, to assist with fluid resuscitation and optimize cardiac output.

- Emotional support and patient/family education . Providing emotional support, clear and concise communication, and education to the patient and family members about the condition, treatment, and possible complications can help decrease anxiety and promote understanding and involvement in the care.

Assess for the following subjective and objective data:

- Abnormal arterial blood gases ( ABGs ) indicating hypoxemia and acidosis.

- Prolonged capillary refill time (>3 seconds).

- Cardiac dysrhythmias.

- Altered level of consciousness.

- Cold and clammy skin.

- Decreased skin turgor.

- Dry mucous membranes.

- Increased thirst.

- Narrowing of pulse pressure.

- Orthostatic hypotension.

- Tachycardia.

- Variable urine output ranging from normal (>30 ml/hr) to as low as 20 ml/hr.

Assess for factors related to the cause of hypovolemic shock:

- Alterations in heart rate and rhythm (tachycardia).

- Decreased ventricular filling (preload) and diminished venous return.

- Fluid volume loss of 30% or more (severe blood loss).

- Late uncompensated hypovolemic shock.

- Active fluid volume loss (abnormal bleeding , diarrhea , diuresis, or abnormal drainage).

- Internal fluid shifts.

- Inadequate fluid intake and/or severe dehydration.

- Regulatory mechanism failure.

- Decreased urinary output (less than 30 ml per hour).

- Decreased peripheral pulses and decreased pulse pressure.

- Decreased blood pressure.

- Decreased stroke volume and decreased preload.

After conducting a thorough assessment of a patient experiencing hypovolemic shock, the next step of the nursing process is to formulate an appropriate nursing diagnosis. This diagnosis reflects the patient’s current health condition and needs and guides the development of a tailored care plan.

Goals and expected outcomes may include:

- The client will maintain adequate cardiac output, as evidenced by strong peripheral pulses, systolic BP within 20 mm Hg of baseline, HR 60 to 100 beats per minute with a regular rhythm, urinary output of 30 ml/hr or greater, warm and dry skin, and normal level of consciousness.

- The client will be normovolemic as evidenced by HR 60 to 100 beats per minute, systolic BP greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg, absence of orthostasis, urinary output greater than 30ml/hr, and normal skin turgor.

- The client will experience a decrease in anxiety levels.

Nursing Interventions and Actions

Preventing shock is a key aspect of nursing care. Close monitoring of at-risk patients and prompt fluid replacement can help prevent hypovolemic shock. Nursing care also involves supporting the treatment of the underlying cause and restoring intravascular volume. Safe administration of fluids and medications, documentation of their effects, and the use of volumetric IV pumps for vasopressor medications are important nursing responsibilities. Monitoring for complications and side effects and promptly reporting them are crucial in providing comprehensive care. Therapeutic interventions and nursing actions for patients with hypovolemic shock may include:

In hypovolemic shock, there is a significant loss of blood volume, resulting in reduced venous return to the heart. This leads to decreased preload, impairing the ability of the heart to fill adequately, which in turn decreases cardiac output. Furthermore, the body initiates compensatory mechanisms such as increased heart rate and systemic vascular resistance but these can only partially offset the decrease in cardiac output. The following are assessment and nursing interventions for managing decrease in cardiac output:

1. Administer fluid and blood and fluid replacement therapy as prescribed. Safe administration of blood transfusions is a critical nursing responsibility. Prompt acquisition of blood specimens, baseline blood tests, and blood typing are important in emergency situations. Close monitoring of patients receiving blood products is essential to detect adverse effects. Complications related to fluid replacement, such as cardiovascular overload and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, must be carefully monitored. Older adults, patients with preexisting cardiac disease, and those receiving multiple blood products are at increased risk. Transfusion-related acute lung injury is a potential complication characterized by pulmonary edema and respiratory distress. Monitoring parameters include hemodynamic pressure, vital signs, blood gases, lactate levels, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, bladder pressure, and fluid intake and output. Temperature should also be closely monitored to prevent hypothermia . Physical assessment focuses on jugular vein distention and jugular venous pressure, which increases with fluid overload. Close monitoring of cardiac and respiratory status is crucial, with prompt reporting of any changes to the primary provider.

2. Assess the client’s HR and BP, including peripheral pulses. Use direct intra-arterial monitoring as ordered. Sinus tachycardia and increased arterial BP are seen in the early stages to maintain an adequate cardiac output. Hypotension happens as the condition deteriorates. Vasoconstriction may lead to unreliable blood pressure. Pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic) decreases in shock. Older clients have reduced response to catecholamines; thus their response to decreased cardiac output may be blunted, with less increase in HR.

3. Assess the client’s ECG for dysrhythmias. Cardiac dysrhythmias may occur from the low perfusion state, acidosis, or hypoxia, as well as from side effects of cardiac medications used to treat this condition.

4. Assess capillary refill time. Capillary refill is slow and sometimes absent.

5. Assess the respiratory rate, rhythm, and auscultate breath sounds. Characteristics of a shock include rapid, shallow respirations and adventitious breath sounds such as crackles and wheezes.

6. Monitor oxygen saturation and arterial blood gases . Pulse oximetry is used in measuring oxygen saturation. The normal oxygen saturation should be maintained at 90% or higher. As shock progresses, aerobic metabolism stops and lactic acidosis occurs, resulting in an increased level of carbon dioxide and decreasing pH.

7. Monitor the client’s central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (PADP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and cardiac output/cardiac index. CVP provides information on filling pressures of the right side of the heart; pulmonary artery diastolic pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure reflect left-sided fluid volumes. Cardiac output provides an objective number to guide therapy.

8. Assess for any changes in the level of consciousness. Restlessness and anxiety are early signs of cerebral hypoxia while confusion and loss of consciousness occur in the later stages. Older clients are especially susceptible to reduced perfusion to vital organs.

9. Assess urine output. The renal system compensates for low BP by retaining water. Oliguria is a classic sign of inadequate renal perfusion from reduced cardiac output.

10. Assess skin color, temperature, and moisture. Cool, pale, clammy skin is secondary to a compensatory increase in sympathetic nervous system stimulation and low cardiac output and desaturation.

11. Provide electrolyte replacement as prescribed. Electrolyte imbalance may cause dysrhythmias or other pathological states.

12. If possible, use a fluid warmer or rapid fluid infuser. Fluid warmers keep core temperature. Infusing cold blood is associated with myocardial dysrhythmias and paradoxical hypotension. Macropore filtering IV devices should also be used to remove small clothes and debris.

Identifying and addressing the underlying cause of hypovolemia, such as controlling bleeding or correcting dehydration, is important in managing the patient’s condition effectively. To improve fluid volume deficiency in patients with hypovolemic shock, immediate administration of intravenous fluids such as crystalloids (e.g., normal saline , lactated Ringer’s solution) and colloids (e.g., albumin) is essential. These fluids help replenish blood volume, increase preload, and restore cardiac output. The following are assessment and nursing interventions for enhancing fluid volume deficit :

1. Monitor BP for orthostatic changes (changes seen when changing from a supine to a standing position). A common manifestation of fluid loss is postural hypotension. The incidence increase with age. Note the following orthostatic hypotension significances:

- Greater than 10 mm Hg: circulating blood volume decreases by 20%.

- Greater than 20 to 30 mm Hg drop: circulating blood volume is decreased by 40%.

2. Assess the client’s HR, BP, and pulse pressure. Use direct intra-arterial monitoring as ordered. Sinus tachycardia and increased arterial BP are seen in the early stages to maintain an adequate cardiac output. Hypotension happens as the condition deteriorates. Vasoconstriction may lead to unreliable blood pressure. Pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic) decreases in shock. Older clients have reduced response to catecholamines; thus their response to decreased cardiac output may be blunted, with less increase in HR.

3. Assess for changes in the level of consciousness. Confusion, restlessness, headache, and a change in the level of consciousness may indicate an impending hypovolemic shock.

4. Monitor for possible sources of fluid loss. Sources of fluid loss may include diarrhea , vomiting , wound drainage, severe blood loss, profuse diaphoresis, high fever , polyuria, burns , and trauma.

5. Assess the client’s skin turgor and mucous membranes for signs of dehydration. Decreased skin turgor is a late sign of dehydration. It occurs because of the loss of interstitial fluid.

6. Monitor the client’s intake and output. Accurate measurement is important in detecting negative fluid balance and guiding therapy. Concentrated urine denotes a fluid deficit.

7. Monitor coagulation studies, including INR, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, fibrin split products, and platelet count as ordered. Specific deficiencies guide treatment therapy.

8. Obtain a spun hematocrit, and reevaluate every 30 minutes to 4 hours, depending on the client’s ability. Hematocrit decreases as fluids are administered because of dilution. As a rule of thumb, hematocrit decreases by 1% per liter of normal saline solution or lactated Ringer’s used. Any other hematocrit decrease must be evaluated as an indication of continued blood loss.

9. Place patient in a modified Trendelenburg position. Proper positioning of the patient can aid in fluid redistribution in addition to fluid administration. The modified Trendelenburg position, also known as passive leg raising, is recommended for patients with hypovolemic shock. Elevating the legs facilitates venous blood return and serves as a dynamic assessment of fluid responsiveness. The nurse monitors vital signs, specifically blood pressure and pulse pressure, for improvement. It is important to note that a full Trendelenburg position is not recommended as it may impede breathing and does not increase blood pressure or cardiac output.

10. If hypovolemia is a result of severe diarrhea or vomiting, administer antidiarrheal or antiemetic medications as prescribed, in addition to IV fluids. Treatment is guided by the cause of the problem.

11. Encourage oral fluid intake if able. The oral route supports maintaining fluid balance.

12. Prepare to administer a bolus of 1 to 2 L of IV fluids as ordered. Use crystalloid solutions for adequate fluid and electrolyte balance. The client’s response to treatment relies on the extent of the blood loss. If blood loss is mild (15%), the expected response is a rapid return to normal BP. If the IV fluids are slowed, the client remains normotensive. If the client has lost 20% to 40% of circulating blood volume or has continued uncontrolled bleeding, a fluid bolus may produce normotension, but if fluids are slowed after the bolus, BP will deteriorate. Extreme caution is indicated in fluid replacement in older clients. Aggressive therapy may precipitate left ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary edema.

13. Initiate IV therapy. Start two shorter, large-bore peripheral IV lines. Maintaining adequate circulating blood volume is a priority in treating hypovolemic shock. The amount of fluid infused is more important than the specific type of fluid used. Large-bore IV catheters should be used to maximize the volume that can be infused. Rapid access for fluid administration is achieved through the insertion of two or more large-gauge IV lines. In challenging cases, an intraosseous catheter may be considered. Multiple IV lines allow for simultaneous administration of fluids, medications, and blood components. The choice of fluids aims to restore intravascular volume and prevent intracellular fluid shifts. For further details on commonly used fluids in shock treatment, refer to Table 14-3.

14. Administer blood products (e.g., packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) as prescribed. Transfuse the client with whole blood-packed red blood cells. Preparing fully crossmatched blood may take up to 1 hour in some laboratories. Consider using uncross-matched or type-specific blood until cross-matched blood is available. If type-specific blood is not available, type O blood may be used for exsanguinating clients. If available, Rh-negative blood is preferred, especially for women of childbearing age. Autotransfusion may be used when there is massive bleeding in the thoracic cavity.

15. Monitor the client’s central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (PADP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and cardiac output/cardiac index. CVP provides information on filling pressures of the right side of the heart; pulmonary artery diastolic pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure reflect left-sided fluid volumes. The cardiac output provides an objective number to guide therapy.

Enhancing cardiac tissue perfusion is vital in hypovolemic shock for multiple reasons. It prevents myocardial ischemia , supports organ function, and maintains hemodynamic stability. The following are interventions to improve cardiac tissue perfusion:

1. Assess for signs of decreased tissue perfusion. Particular clusters of signs and symptoms occur with differing causes. Evaluation provides a baseline for future comparison.

2. Assess for rapid changes or continued shifts in mental status. Restlessness and anxiety are early signs of cerebral hypoxia while confusion and loss of consciousness occur in the later stages.

3. Assess capillary refill. Capillary refill is slow and sometimes absent.

4. Observe for pallor, cyanosis, mottling, and cool or clammy skin. Assess the quality of every pulse. The nonexistence of peripheral pulses must be reported or managed immediately. Systemic vasoconstriction resulting from reduced cardiac output may be manifested by diminished skin perfusion and loss of pulses. Therefore, assessment is required for constant comparisons

5. Record BP readings for orthostatic changes (a drop of 20 mm Hg systolic BP or 10 mm Hg diastolic BP with position changes). Stable BP is needed to keep sufficient tissue perfusion. Medication effects such as altered autonomic control, decompensated heart failure , reduced fluid volume, and vasodilation are among many factors potentially jeopardizing optimal BP.

6. Use pulse oximetry to monitor oxygen saturation and pulse rate. Pulse oximetry is a useful tool to detect changes in oxygen saturation.

7. Review laboratory data (ABGs, BUN, creatinine , electrolytes , international normalized ratio, and prothrombin time or partial thromboplastin time) if anticoagulants are utilized for treatment. Blood clotting studies are being used to conclude or make sure that clotting factors stay within therapeutic levels. Gauges of organ perfusion or function. Irregularities in coagulation may occur as an effect of therapeutic measures.

8. Assist with position changes. Gently repositioning the patient from a supine to a sitting/standing position can reduce the risk of orthostatic BP changes. Older patients are more susceptible to such drops of pressure with position changes.

9. Provide oxygen therapy if indicated. Oxygen is administered to increase the amount of oxygen carried by available hemoglobin in the blood.

10. Administer IV fluids as ordered. Sufficient fluid intake maintains adequate filling pressures and optimizes cardiac output needed for tissue perfusion.

Monitoring and preventing complications during hypovolemic shock is important for timely intervention and optimizing patient outcomes, as it allows for early recognition of worsening conditions, appropriate resuscitation, and prevention of organ damage or failure. The following are nursing assessments and interventions to prevent complications for patients experiencing hypovolemic shock:

1. If the only visible injury is an obvious head injury, look for other causes of hypovolemia (e.g., long-bone fractures, internal bleeding, external bleeding). Hypovolemic shock following trauma usually results from hemorrhage .

2. If trauma has occurred, evaluate and document the extent of the client’s injuries; use a primary survey (or another consistent survey method) or ABCs: airway with cervical spine control, breathing, and circulation. A primary survey helps identify potentially life-threatening injuries. This serves as a quick primary assessment.

3. Perform a secondary survey after all life-threatening injuries are ruled out or treated. A secondary survey uses a methodical head-to-toe inspection.

4. For post-surgical clients, monitor blood loss (mark skin area, weigh dressing to determine fluid loss, monitor chest tube drainage). It is important to observe an expanding hematoma or swelling or increased drainage to identify bleeding or coagulopathy.

5. Control the external source of bleeding by applying direct pressure to the bleeding site. External bleeding is controlled with firm, direct pressure on the bleeding site, using a thick dry dressing material. Prompt, effective treatment is needed to preserve vital organ function and life.

6. For trauma victims with internal bleeding (e.g., pelvic fracture ), military antishock trousers (MAST) or pneumatic antishock garments (PASGs) may be used. These devices are useful for tamponade bleeding. Hypovolemia from long-bone fractures (e.g., femur or pelvic fractures) may be uncontrolled by splinting with air splints. Hare traction splints or MAST and/or PASG trousers may be used to reduce tissue and vessel damage from the manipulation of unstable fractures.

7. If hypovolemia is a result of severe burns , calculate the fluid replacement according to the extent of the burn and the client’s body weight. Formulas such as the Parkland formula, which follows, guide fluid replacement therapy:

% BSA (body surface area) burned x weight in kg x 4 ml lactated Ringer’s = Total fluid to be infused over 24 hours: half given intravenously over 8 hours and a half given over the next 16 hours.

8. If the client’s condition progressively deteriorates, initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation or other lifesaving measures according to Advanced Cardiac Life Support guidelines, as indicated. Shock unresponsive to fluid replacement can worsen into cardiogenic shock . Depending on etiological factors, vasopressors, inotropic agents, antidysrhythmics, or other medications can be used.

9. If bleeding is secondary to surgery , anticipate or prepare for a return to surgery. Surgery may be the only option to fix the problem.

Anxiety in hypovolemic shock may arise from physiological stress responses and awareness of the critical condition. Nursing assessments and interventions can effectively alleviate anxiety in these patients. The following are nursing assessments and interventions to help reduce anxiety in patients experiencing hypovolemic shock:

1. Assess the previous coping mechanisms used. Anxiety and ways of decreasing perceived anxiety are highly individualized. Interventions are most effective when they are consistent with the client’s established coping pattern. However, in the acute care setting these techniques may no longer be feasible.

2. Assess the client’s level of anxiety. Shock can result in an acute life-threatening situation that will produce high levels of anxiety in the client as well as in significant others.

3. Acknowledge awareness of the client’s anxiety. Acknowledgment of the client’s feelings validates the client’s feelings and communicates acceptance of those feelings.

4. Encourage the client to verbalize his or her feelings. Talking about anxiety-producing situations and anxious feelings can help the client perceive the situation in a less threatening manner.

5. Reduce unnecessary external stimuli by maintaining a quiet environment. If medical equipment is a source of anxiety, consider providing sedation to the client. Anxiety may escalate with excessive conversation, noise, and equipment around the client.

6. Explain all procedures as appropriate, keeping explanations basic. The information helps reduce anxiety. Anxious clients were unable to understand anything more than simple, clear, brief instructions.

7. Maintain a confident, assured manner while interacting with the client. Assure the client and significant others of close, continuous monitoring that will ensure prompt intervention. The staff’s anxiety may be easily perceived by the client. The client’s feeling of stability increases in a calm and non-threatening atmosphere. The presence of a trusted person may help the client feel less threatened.

Expected outcomes for the patient with hypovolemic shock include:

- Maintained fluid volume at a functional level.

- Reported understanding of the causative factors of fluid volume deficit.

- Maintained normal blood pressure, temperature, and pulse.

- Maintained elastic skin turgor, most tongue and mucous membranes, and orientation to person, place, and time.

The discharge and home care guidelines for patients recovering from hypovolemic shock may vary depending on the severity of the condition and the specific needs of the individual. However, here are some general considerations:

- Follow-up appointments: The importance of complying with the follow-up appointments with the healthcare provider to evaluate the progress of recovery and to adjust treatment if needed.

- Rest and recovery: Ensure an adequate period of rest and gradually increase activity levels as advised by the healthcare provider.

- Hydration and nutrition : Ensure adequate hydration by increasing fluid intake as indicated by the HCP. Follow any dietary recommendations to promote healing and restore lost nutrients.

- Wound care: Adhere to instructions on proper wound care , such as keeping the area clean, changing dressings as directed, and observing for signs of infection if there are any wounds or surgical incisions.

- Patient and family education: Recognizing the warning signs and symptoms that may indicate a worsening condition or potential complications.

- Emotional support: Hypovolemic shock can be a traumatic experience. Seeking emotional support from friends, family, or support groups to help cope with any anxiety, or emotional distress that may arise.

The focus of documentation includes:

- Degree of deficit and current sources of fluid intake.

- I&O, fluid balance , changes in weight, presence of edema, urine specific gravity, and vital signs.

- Results of diagnostic studies.

- Functional level and specifics of limitations.

- Needed resources and adaptive devices.

- Availability and use of community resources.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s responses to interventions, teachings, and actions performed

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcomes .

- Modifications to plan of care.

Recommended nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan books and resources.

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing Diagnosis Handbook: An Evidence-Based Guide to Planning Care We love this book because of its evidence-based approach to nursing interventions. This care plan handbook uses an easy, three-step system to guide you through client assessment, nursing diagnosis, and care planning. Includes step-by-step instructions showing how to implement care and evaluate outcomes, and help you build skills in diagnostic reasoning and critical thinking.

Nursing Care Plans – Nursing Diagnosis & Intervention (10th Edition) Includes over two hundred care plans that reflect the most recent evidence-based guidelines. New to this edition are ICNP diagnoses, care plans on LGBTQ health issues, and on electrolytes and acid-base balance.

Nurse’s Pocket Guide: Diagnoses, Prioritized Interventions, and Rationales Quick-reference tool includes all you need to identify the correct diagnoses for efficient patient care planning. The sixteenth edition includes the most recent nursing diagnoses and interventions and an alphabetized listing of nursing diagnoses covering more than 400 disorders.

Nursing Diagnosis Manual: Planning, Individualizing, and Documenting Client Care Identify interventions to plan, individualize, and document care for more than 800 diseases and disorders. Only in the Nursing Diagnosis Manual will you find for each diagnosis subjectively and objectively – sample clinical applications, prioritized action/interventions with rationales – a documentation section, and much more!

All-in-One Nursing Care Planning Resource – E-Book: Medical-Surgical, Pediatric, Maternity, and Psychiatric-Mental Health Includes over 100 care plans for medical-surgical, maternity/OB, pediatrics, and psychiatric and mental health. Interprofessional “patient problems” focus familiarizes you with how to speak to patients.

Other recommended site resources for this nursing care plan:

- Nursing Care Plans (NCP): Ultimate Guide and Database MUST READ! Over 150+ nursing care plans for different diseases and conditions. Includes our easy-to-follow guide on how to create nursing care plans from scratch.

- Nursing Diagnosis Guide and List: All You Need to Know to Master Diagnosing Our comprehensive guide on how to create and write diagnostic labels. Includes detailed nursing care plan guides for common nursing diagnostic labels.

Other care plans for hematologic and lymphatic system disorders:

- Anaphylactic Shock

- Aortic Aneurysm

- Bleeding Risk & Hemophilia

- Deep Vein Thrombosis

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

- Sepsis and Septicemia

- Sickle Cell Anemia Crisis

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- MedEdPORTAL

Hypovolemic Shock in a Child: A Pediatric Simulation Case

Molly rideout.

1 Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine at the University of Vermont

William Raszka

2 Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine at the University of Vermont

Associated Data

B. Laboratory Values.docx

C. Critical Actions Checklist and Evaluation Tools.docx

D. Faculty Resources.docx

E. Standardized Patient Information.docx

F. Flow Diagram of Case.docx

G. One Page Case Summary.docx

H. Intraosseous Instructions.docx

I. Survey.docx

J. Clinical Signs Dehydration Table.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Introduction

Volume depletion is a common problem in pediatrics. Interns need to be able to recognize critical illness such as hypovolemic shock, obtain access, and manage complications. This simulation case involves a child with hypovolemic shock who requires intraosseous (IO) needle placement. While designed for subinterns in pediatrics, it is relevant for clerkship students and interns in family medicine and emergency medicine.

In this case, a 3-year-old child presents with vomiting, diarrhea, and lethargy, and is in hypovolemic shock. As IV access cannot be obtained, he requires IO access. Laboratory results reveal hypoglycemia, hypernatremia, and acute kidney injury. Required equipment includes an IV arm task trainer and a child mannequin with IO capacity (or a child mannequin plus a separate IO task trainer). Learning objectives include recognizing and managing hypovolemic shock, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte disturbances; obtaining IO access; and communicating with a distraught parent. Critical actions include attempting IO access, requesting labs, and administering fluids. Students complete a selfassessment survey following the case.

A pilot study was conducted in 2017 with all subinterns ( N = 16) on the pediatric service. Students' perceived competence in assessment and management of volume depletion and procedural skills such as IO placement were high following the session, and students rated the case as a highly beneficial learning experience.

This clinical simulation case allows students to demonstrate clinical reasoning skills, procedural skills, and management skills regarding hypovolemic shock. It may be used as part of a curriculum for fourth-year students entering pediatric residency.

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

- 1. Recognize a child with hypovolemic shock based on vital signs, physical exam, and a limited history.

- 2. Interpret laboratory tests related to hypovolemic shock.

- 3. Develop management plans for volume depletion and fluid/electrolyte abnormalities.

- 4. Demonstrate proper technique for obtaining intraosseous access.

- 5. Demonstrate effective communication with a distraught parent.

As subinterns, students have primary responsibility for patients, but during emergency clinical situations, they do not usually play a central role. As a result they may be underprepared when they encounter similar clinical situations during residency. Although residency preparatory courses (usually with simulated emergency cases) are increasing in popularity, we feel that it is important to have structured hands-on learning opportunities earlier in the fourth year so that performance gaps may be recognized and addressed. The length of this simulation case provides ample opportunity to observe students' ability to clinically solve problems, and the complexity and acuity of the case demands that every student take an active role. Through problem solving in a small group setting, learners develop teamwork skills and practice communicating with a distraught parent while making clinical decisions.

This module provides a stand-alone resource to be used for fourth-year students in pediatrics to learn about fluid management and intraosseous (IO) needle placement. It is helpful for the learners to have an understanding of the basic concepts of volume depletion prior to starting the case. It is not designed to be an evaluated exercise but to be used in an environment where it is safe for learners to make mistakes and learn from them. It could be used effectively as an application exercise for a flipped-classroom exercise or as an isolated simulation exercise. We use it during the subinternship, but it could also be used during a residency preparatory course or intern orientation. It could be used in conjunction with our previously published case 1 and others as a curriculum for fourth-year medical students entering pediatrics. It is also suitable for third-year medical students or early first-year residents in pediatrics, family medicine, or emergency medicine.

Although assessment and management of volume depletion are essential skills in pediatrics and ones that are frequently utilized during pediatric residency, there are few published curricular tools for working with learners to develop the knowledge and procedural skills to effectively diagnose and manage hypovolemia in children. There are published cases of shock in pediatric patients, but they involve newborns, 2 , 3 don't include IO needle placement, 4 or are geared toward pediatric residents or fellows. 5 This case adds to the growing number of simulation cases available for use in the fourth year of medical school. 6

Development

We developed this simulation exercise as part of a series for fourth-year students administered during weekly education sessions as part of their subinternship in pediatrics. There are between two and four students completing subinternships at the same time, so we designed it as a team exercise to focus on clinical reasoning skills in a safe environment. We selected the topic as it is addressed in the Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics/Association of Pediatric Program Directors (COMSEP/APPD) Fourth Year Curriculum 7 in the following areas: “Describe the diagnostic evaluation and management of hospitalized patients with fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base disturbances,” “Recognize variations in common laboratory findings and vital signs,” and “Describe the signs and symptoms that suggest deterioration (including signs of shock and respiratory failure) or improvement of a patient's clinical condition.” Students were not expected to prepare specifically for the exercise and did not know the topic ahead of time. It was essential for facilitators to have a working knowledge of fluid/electrolyte management and IO placement skills in order to provide a robust discussion and skills session on these topics following the case (background information provided in Appendix D ).

Equipment/Environment

We recommend the following equipment for successful implementation of this simulation case:

- ○ Child mannequin and separate IO partial task trainer.

- • IO kit, including driver (EZ-IO), 15g pediatric needle, stabilizer, instructions, or manual IO needle.

- • Child IV arm task trainer.

- ○ Length-based tape.

- ○ PICU resuscitation card.

- ○ Bags of normal saline, ½ normal saline, lactated Ringer's solution, Normosol.

- ○ Bags of dextrose solution, including D10W, D25W, D50W.

- ○ Antibiotic bag (Ceftriaxone).

- ○ Nasal cannula, venturi mask, nonrebreather mask.

- ○ Child bag and mask (2 sizes mask).

- ○ Oxygen tubing.

- ○ Foley catheter, lubricating jelly, simulated swabsticks, sterile urine cup, sterile gloves.

- ○ Tourniquet, 22-guage IV needle X2, microbore extension set, IV connector set, IV pole, extra IV tubing, tape, saline flushes (4), 1cc, 5cc, 10cc, 20cc syringes, alcohol swabs, 18- or 20-guage 1.5 inch needles.

- • Bedside glucose measurement tool.

- • Acetaminophen suppository.

Ideally played by a standardized patient (SP), the parent gives history and answers questions. The parent may be played as “distraught.”

May be played by a nursing student or the facilitator. The nurse assists in carrying out orders and enlisting help from students for various tasks. If the facilitator plays this role, they can be inside the room making observations on the “nursing chart” throughout the case to use as discussion points during the debriefing.

Simulation staff member

Changes vital signs on monitors as indicated and gathers any missing equipment during case.

Facilitator

Provides physical exam findings and assists students in finding equipment. Alternatively, the facilitator could be out of room watching through one-way glass and listening with headphones. The facilitator could play the role of nurse.

Implementation

One of us met with students for weekly sessions in the Clinical Simulation Laboratory during the month-long pediatrics subinternship, and this case comprised one of the sessions. After students arrived at the lab, we met outside of the simulation space to have a brief check-in and discuss expectations and ground rules for the session (e.g., a safe space for learning free from formal evaluation; procedures beyond their scope of practice are acceptable in this setting, etc.) We described the setting (the emergency department) and our role (nurse), and we discussed the importance of staying in roles to maximize learning for the entire team. We explained that we would stay in the role of nurse except to provide physical exam findings, and that we would provide students with any needed supplies as well as lab results when available.

We found it most successful to meet with students in the mid-afternoon so that they had time following morning rounds to perform necessary tasks before signing out to the senior resident. We maintained large labeled Ziplock bags with materials for the cases, including “IV supplies,” “syringes,” and “respiratory supplies” among others, to ensure consistent restocking and easy access. We used a whiteboard in the room during the case, so students could keep track of their thoughts and plans, and for use by teams during the debriefing. A child mannequin was central to the case, and since at times the mannequin with IO capability was unavailable, we occasionally used an IO task trainer with a low fidelity child mannequin with acceptable results. We found that the case usually takes about 45 minutes for students to work through, followed by 45 minutes of debriefing and 30 minutes on procedural skills practice.

The case is fully presented in the simulation case file ( Appendix A ). Laboratory values ( Appendix B ) are formatted for easy viewing and lamination. These individual lab results were provided to students when requested, along with the reference for normal laboratory values. The critical actions checklist (CAC, Appendix C ) may be adapted for evaluative use. A faculty reference document Appendix D with information for facilitators to review to help guide the discussion following the case is also provided and can be adapted for student use as well. An in-depth description of the case from the SP's point of view Appendix E is the template used at our institution to provide SPs with in-depth information about their character. The case is longer than many simulation cases, designed to last approximately 90–120 minutes, so it is essential that the SP knows the case well. A one-page flow diagram Appendix F may be used with a two-sided summary of the case Appendix G for easy quick reference during the case for both the facilitator and the simulation center technician. A concise description of the IO technique is provided Appendix H for easy lamination to be used by students during the case. Additional information about IO access is also provided in the faculty reference document, including a reference for an instructional video, and this information could be reviewed prior to the session by participants or following the case as part of debriefing and/or skills-station practice. The survey used for student self-assessment following the case is included Appendix I , Finally, the clinical signs of dehydration table is included, formatted for lamination and easy use during the case Appendix J .

Participants received formative feedback following the case during the 45-minute debriefing. Facilitators reviewed each learning objective in detail with students and completed a critical actions checklist. The items included on the CAC were agreed on by the authors as the minimum essential actions learners should be able to perform in order to say they successfully worked through the case.

Following the case, students completed a survey reporting perceived competence and improvement in related skills. We made an intentional decision to not provide summative evaluation for this learning exercise, based on informal student surveys, as they uniformly opposed formal evaluation and highly valued the fact that the case was a safe learning environment free from formal evaluation. However, a summative evaluation could easily be designed for the exercise, and published checklist for IO placement that may be used for this purpose. 8 SPs could also complete a checklist following the case regarding communication skills.

We use a student-centered “plus-delta” approach for debriefing. As described in our previous publication 1 , in this technique, the facilitator focuses first on what participants felt they did successfully and then focuses on what they would want to do differently. SPs and any members of the interprofessional team are part of the initial debriefing, including discussion about team skills and roles. Then the facilitator asks students to present a summary of the clinical scenario in order to develop a shared mental model. Facilitators review learning objectives, critical actions, and any questions students have as they arise. Procedural practice takes place following the debriefing. A list of questions and discussion points used during the debriefing are included below:

General questions for all participants:

- 1. What went well?

- 2. What could have been done differently?

- 3. How did you work as a team?

- 4. What was the clinical scenario? What happened?

Specific questions/discussion points related to educational content:

- 1. Describe how to estimate fluid deficit and calculate fluid replacement.

- 2. Review the different types of shock and vital signs characteristic of shock.

- 3. Compare fluid management at the initial presentation of shock versus the stabilization/deficit replacement stage.

- 4. Compare types of fluid, including crystalloid and colloid, with indications for use of each.

- 5. Discuss indications for administering a dextrose bolus as well as dextrose-containing isotonic fluid.

- 6. Review the basic principles of management of hypernatremia.

- 7. Review the basic principles for management of acute kidney injury.

- 8. Review the differential diagnosis and management of metabolic acidosis.

- 9. Discuss the options and challenges of access, including the risks/benefits of IO access.

- 10. Discuss the issues involved when caregivers question, challenge, or refuse treatment.

We have run this case approximately 35 times with over 80 fourth-year students during their subinternship rotation in pediatrics from 2013–2017. There are usually 2–3 students participating, and we have found that this is an ideal size. It is possible to run the case with four students, but it has not run as smoothly. All students participating in the module during 2017 (N= 16) completed a survey following the session ( Table ). Survey results showed that students' perceived competence in assessment and management of volume depletion and IO placement was high (average scores of 4.38 and 4.50, respectively, on a 5-point Likert scale), and that they felt the session improved clinical decision-making, procedural skills, and team skills (4.38, 4.25, and 4.56 respectively). Overall, they rated it as a highly beneficial learning experience (4.88).

Starting in 2016, four other pediatric hospitalists received training in and routinely facilitate the scenarios. Minor changes in the scenarios have been made based on their feedback. Preparation time for facilitators was minimal and included reviewing the case, reading any of the background resource material that they felt would be helpful for teaching, and reviewing the debriefing methods. We generally arrive 15–30 minutes early to confirm room set-up and clarify expectations and plan with Simulation Center staff and the SP.

This simulation case has been successful in helping students to recognize hypovolemic shock and associated abnormalities through history, clinical signs and symptoms, and interpretation of lab values. The case also helped develop appropriate management plans. Students work through the case as a team, similar to a true patient presentation in the emergency room. They place an IO needle and provide dextrose and fluid boluses, witnessing normalization of vital signs and lab values. Throughout the case, they engage with a distraught parent, sharing thoughts about a differential diagnosis and management plans.

The case has become a successful tool for simulation-based learning based on surveys and informal feedback, and it contains all necessary instructions and supplements to provide a rich educational experience. It may be used in isolation or in combination with our previously published case 1 or other cases targeting the fourth year. 5 It adds to the growing number of published resources for use in pediatric fourth year rotations or early internship. Students who have completed the exercise have asked for more frequent sessions, stating that the sessions are practical and relevant.

We encountered several challenges inherent to the format of the cases:

- 1. IO needle placement is outside of the scope of practice for subinterns, and they are sometimes hesitant to attempt this procedure without help. We provide specific instruction prior to the case that it is appropriate in this simulation setting to attempt the procedure they would not otherwise do without supervision. Likewise, we discuss this with the SP so they are aware. Alternatively, the facilitator could provide instruction either by breaking roles or by playing the role of “chief resident” to instruct the students.

- 2. Students must be unsuccessful in obtaining intravenous access in order to necessitate IO needle placement. We routinely provide students with a malfunctioning child IV task trainer to attempt intravenous access and when they are unsuccessful, the nurse tries and fails as well, hopefully prompting the students to consider the IO route. Following the case, we provide direct instruction with a functioning child IV task trainer arm so students experience success.

- 3. When students perform a procedure improperly, it is important to review following the case so they learn from the mistakes. We have chosen to not interrupt the case to provide procedural instruction in an effort to make the case as realistic as possible without breaking roles. Following the case, all learners receive specific instruction and practice on each procedure using skill stations or at the bedside.

- 4. It is challenging to provide physical exam findings without breaking roles. Even with high fidelity manikins, many subtle exam findings are impossible to portray. We have chosen to have the facilitator break their role to provide physical exam findings. Other options are to provide a printed record of the physical exam or to have the findings relayed over audio.

There were a few limitations to the case. Although the response rate was high (100%) for the surveys following the case, the absolute number is small ( N = 16) and thus limited in statistical significance. Our results successfully addressed the learning objectives but were limited to student self-assessment (Kirkpatrick's pyramid level 1). 9 For a more robust assessment, we could incorporate assessment of a student's clinical abilities as reported by either residents or attendings during their subinternship. At this time, we have not provided summative evaluations for the students participating in the modules, however this may not be an option at other institutions. There is a CAC that may be used for scoring, and a more detailed evaluation tool could be easily developed for this resource if desired, including a procedure checklist for IO placement and/or communications skills checklist. We prefer to rely on in-person formative comments during the debriefing, maintaining a safe learning environment where learners feel comfortable making mistakes in order to learn from them.

As a learning tool, this case is rich with opportunity for clinical reasoning, problem solving, and teamwork. The opportunity to practice decision-making and procedural skills in a safe learning environment before encountering similar clinical situations in early residency is invaluable. This case adds to a growing number of simulation-based scenarios that may be instrumental in preparing students for early residency.

A. Simulation Case Template.docx

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Clinical Simulation Laboratory at the Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine at the University of Vermont for their Standardized Patient Template used in Appendix E .

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

Ethical approval.

The University of Vermont Committees on Human Subjects approved this study.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

AMBOSS. Shock. 2020. https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Shock (accessed 1 April 2020)