An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Pregnancy intrahepatic cholestasis.

Leela Sharath Pillarisetty ; Ashish Sharma .

Affiliations

Last Update: June 4, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is the most common liver disorder in pregnancy and is associated with an increased risk of adverse obstetrical outcomes like sudden fetal demise. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of ICP, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and managing affected patients.

- Identify the typical presentation of a patient with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

- Outline how to diagnose intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

- Describe the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the detection and management of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and improve outcomes.

- Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a liver disorder in the late second and early third trimester of pregnancy. It is also known as obstetric cholestasis (OC) and is characterized by pruritus with increased serum bile acids and other liver function tests. The pathophysiology of ICP is still not completely understood. The symptoms and biochemical abnormality rapidly resolve after delivery. ICP is associated with an increased risk of adverse obstetrical outcomes, which include stillbirth, respiratory distress syndrome, meconium passage, and fetal asphyxiation. [1] This activity will cover the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of this condition.

The etiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is poorly understood and is thought to be complicated and multifactorial. Genetic susceptibility, hormonal, and environmental factors have been proposed as possible mechanisms. There appears to be a relation between cholestatic properties of reproductive hormones in genetically susceptible women and ICP. The supportive evidence for the genetic susceptibility hypothesis lies in the fact that the disease has been observed more in familial clustering patterns, first-degree relatives, and a higher risk of disease recurrence with subsequent pregnancies. [2] [3] Recent studies have shown evidence of mutations in genes (ABCB4) encoding hepatobiliary canalicular translocator proteins called multidrug resistance 3 (MDR3) and pedigrees with the mode of inheritance being a sex-limited, dominant pattern. [4] [5] Some other genes which seem to play a role in the development of ICP are ATP8B1(FIC1), ABCB11 (BSEP), ABCC2, and NR1H4 (FXR). [6] [7] [8] [9] A different form of intrahepatic cholestasis called progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is considered a broad term for the most severe forms of the different genetically discreet diseases and also has various autosomal recessive genetic mutations as mentioned above. [10] Further analysis of PFIC is out of scope for the current topic.

The role of reproductive hormones in developing ICP has also appeared in multiple studies. Many studies showed an association of high levels of estrogen conditions such as multitone pregnancy, ovarian hyperstimulation effect, and late second-trimester presentation of ICP. [11] ICP typically occurs in the late second trimester when the estrogen levels are the highest in pregnancy. ICP shows similar characteristics seen in women taking contraceptive pills high in estrogen quantity. [12] High circulating estrogen levels may induce cholestasis in genetically predisposed women in ICP. [12] The role of progesterone is only partially apparent; however, recent studies, including some animal model studies, have demonstrated that progesterone sulfated metabolites are partial agonists of farnesoid X receptor FXR (also called bile acid receptor). [13] The progesterone sulfate metabolites alter the hepatobiliary transport system by impairing the functioning of the main hepatic bile acid receptor. [13]

Environmental and seasonal factors have also correlated with ICP. ICP is noted to be more prevalent in women with a low level of selenium and vitamin D. It is also common in some countries in winters when selenium and vitamin D may be low. [14] [12] [15]

Chronic underlying liver disease correlates with ICP; however, it is not yet clear whether chronic liver diseases contribute to developing ICP or are revealed by pregnancy. [16]

- Epidemiology

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is the most common liver disease related to pregnancy. [17] The Incidence and prevalence of ICP vary with ethnicity and geographic distribution. ICP incidence rate is between 0.2 to 2% of pregnancies. [1] It is more common in South American and northern European continents. Research has described ICP in 0.2 to 0.3% of pregnancies in the USA. [18] A higher incidence of ICP is observable with a prior history of ICP, chronic liver disease, chronic hepatitis C, multifetal pregnancy, and advanced maternal age. [19] [15] The recurrence rate of ICP in subsequent pregnancies is high (60 to 70 percent). [20] Turunen K et al. did a survey of 544 former ICP patients and 1235 controls which showed 12.8% of mothers (odds ratio 9.2), 15.9% of sisters (odds ratio 5.3), and 10.3% of daughters (odds ratio 4.8) of women with a history of ICP had liver dysfunction during pregnancy. Similarly, estimates for the relative risk for the siblings of affected women were 12% in another study. [21] [2]

- Pathophysiology

Genetic susceptibility and reproductive hormones, especially estrogen, are found to be the principal contributing factors to the development of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP). See details in the etiology section. Estrogen reduces the expression of nuclear hepatic bile acid receptors and hepatic biliary canalicular transport proteins in genetically susceptible women causing impairment of hepatic bile acid homeostasis and subsequent increased level of bile acids. [13] Downregulation of placental expression of bile acid transporters organic anion transporting polypeptides OATP1A2 and OATP1B3 in ICP placenta in one report also indicates a role in pathophysiology. [22]

- Histopathology

Histopathology shows the widening of the bile canaliculi with bile plugs in hepatocytes and canaliculi in predominantly zone 3 and centrilobular cholestasis with inflammation. [23] [20] Liver biopsy is rarely a requirement for the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP).

- History and Physical

Classically, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) presents in the late second trimester to the early third trimester. The most common complaint is generalized intense pruritus, which usually starts after the 30th week of pregnancy. Pruritus can be more common in palms and soles and is typically worse at night. Other symptoms of cholestasis, such as nausea, anorexia, fatigue, right upper quadrant pain, dark urine, and pale stool, can be present. Clinical jaundice is rare but may present in 14 to 25% of patients after 1 to 4 weeks of the onset of pruritus. [24] Some patients also complain of insomnia secondary to pruritis. Generally, the physical examination is unremarkable except for scratch marks on the skin from pruritus. Pruritis is a cardinal symptom of ICP and may precede biochemical abnormalities. In patients who undergo in vitro fertilization, ovarian hyperstimulation can cause transient symptoms in the first trimester compared to persistent symptoms in the second and third trimester in ICP. [11] Family history of liver dysfunctions during pregnancy in other female relatives requires inclusion because of the role of genetics in pathophysiology.

The diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is via the presence of clinical symptom that is pruritus in the third trimester with elevated maternal total serum bile acids and excluding other diagnoses, which can cause similar symptoms and lab abnormalities. Raised liver function tests in the absence of pruritus require investigation for another cause. The most sensitive and specific marker for ICP is the total serum bile acid (91 and 93 percent) using a cut-off value of 10 micromol/L. [25] Most studies use an upper limit of bile acids between 10 and 14 micromoles/L for the diagnosis of ICP. The risk for fetal complications increases in severe cholestasis with increased serum bile acid levels, usually over 40 micromol/L. Other liver function tests, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) usually mildly elevated and do not exceed two times the upper limit of normal value in pregnancy. Serum alkaline phosphatase can be elevated physiologically sometimes up to four times the upper normal value but has little diagnostic significance in ICP. Elevated bilirubin can present in 25% percent of cases but rarely exceeds 6 mg/dL. [26] High prothrombin time can be present because of vitamin K deficiency (decreased fat-soluble vitamins), but postpartum hemorrhage is rare. [27]

Kremer et al., in their animal model study, found that autotaxin, the serum enzyme converting lysophosphatidylcholine into LPA, which is pruritogenic, was markedly increased in patients with ICP versus pregnant controls and cholestatic patients with versus without pruritus. [28] Kremer et al., in their other study, which included 145 women, also reported that increased serum autotaxin activity represents a highly sensitive, specific, and robust diagnostic marker of ICP, distinguishing ICP from other pruritic disorders of pregnancy and pregnancy-related liver diseases. Pregnancy and oral contraception increase serum autotaxin to a much lesser extent than ICP. [29] Serum autotaxin can be used as a helpful test in excluding other causes of pruritus and elevated bile acid levels.

- Treatment / Management

Once the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is confirmed, immediate treatment is necessary, and the primary goal of therapy is to decrease the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality and to alleviate maternal symptoms.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the drug of choice for the treatment of ICP. [30] The initial starting dose of UDCA is not well established, but it is reasonable to start at 300 mg BID and can be increased to 300 mg three times a day until delivery. Usually, maternal symptoms will alleviate in about two weeks, and the bile acid levels will decline in two to three weeks. If there is no improvement in the patient's symptoms or bile acid levels, the dose can be titrated every week or two to a maximum dose of 21 mg/kg/day. [1] UDCA is well tolerated by most patients; some of the common side effects are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. It has no detrimental impact on the fetus. The mechanism of action of ursodeoxycholic acid is unknown, but studies have shown that after treatment, a significant reduction in total serum bile acids occurs. In a meta-analysis, patients with ICP who received UDCA had better outcomes than those who received an alternative agent. Patients using UDCA had better resolution of pruritus, reduction in liver function tests, and bile acid levels, and decreased incidence of premature birth, fetal distress, respiratory distress syndrome, and need for neonatal intensive care unit admission. [31] [32]

For patients with no improvement of ICP, refractory to UDCA, other medications such as rifampin, cholestyramine, and S-adenosyl-L-methionine are options. [33] Rifampin increases bile acid detoxification and excretion and can be an adjunct to ursodeoxycholic acid. Cholestyramine is an anion exchange resin that decreases the ileal absorption of bile salts, thereby increasing their fecal excretion. S-adenosyl-L-methionine is often administered using a twice-daily intravenous regimen, making it a less attractive option in the management of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. One study found UDCA more effective than S-adenosyl-L-methionine at improving liver function tests but equally effective at improving pruritus. [34] An antihistamine such as chlorpheniramine is often used in ICP to alleviate pruritis. Antihistamines do not affect serum bile acids but may reduce the sensation of pruritus in some women.

Antepartum Management of ICP

In patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, the importance of regular antepartum fetal testing is not proven to be useful to identify fetuses at risk of demise. None of the existing antenatal tests has been shown to either predict or reduce the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes. Nevertheless, most providers find it reassuring to have regular antenatal testing for patients with ICP. Although there is a dearth of high-quality evidence to support antenatal screening in pregnant women with ICP, the consensus is to use weekly biophysical profiles (BPP) to detect fetal compromise.

Timing of Delivery

Many authors have advocated elective early delivery of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy to reduce the risk of sudden fetal demise. The timing of delivery should depend on balancing the risk of fetal death as opposed to the potential risks of prematurity. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies done by Ovadia et al., it was noted that the prevalence of stillbirth after 24 weeks of gestation was 3.44% (95% CI 2.05–5.37) for females with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy compared with 0.3 to 0.4% from pooled national average data among included countries. The elevated total bile acid concentrations (greater than 100 micromol/L) were highly predictive of stillbirth in single pregnancies (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve 0.83 [95% CI 0.74 to 0.92], and the conclusion was that in women with total bile acid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or more, delivery should probably occur by 35 to 36 weeks of gestation. [35] In women with ICP, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends induction of labor after 37+0 weeks of gestation whereas, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends delivery between 36+0 to 37+0 weeks of pregnancy. [36]

Consider delivery before 37 weeks of gestation in women with ICP if they have one of the following: [36]

- Maternal symptoms along with jaundice not improving with medications, and needing escalating doses of UDCA

- Previous history of intrauterine fetal demise before 37 weeks secondary to ICP

- Total serum bile acid concentration of more than 100 micromol/L

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is not an indication for cesarean delivery. Postpartum - pruritus typically disappears in the first two to three days following delivery, and serum bile acid concentrations will normalize eventually. ICP is not a contraindication to breastfeeding, and mothers with a history of ICP in pregnancy can breastfeed their infants. Postpartum monitoring and follow-up of bile acids and liver function tests should be done in 4-6 weeks to ensure resolution. Women with the persistent abnormality of liver function tests after 6 to 8 weeks require investigation for other etiologies.

- Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of cholestasis in pregnancy categorizes into two groups, conditions causing pruritis and conditions, causing elevated liver function.

Conditions Causing Pruritis

- Pemphigoid gestationis

- Pruritis gravidarum

- Prurigo in pregnancy

- Atopic dermatitis

- Allergic reactions

Conditions Causing Impaired Liver Function

- HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets)

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- Viral hepatitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Drug-induced liver damage

Maternal prognosis is benign in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) and symptoms, and abnormal liver biochemistry resolves rapidly after delivery. In some women, the abnormal LFTs may remain persistent and should be investigated further for any other etiology. In a large cohort study, women with ICP were found to have a high incidence of hepatobiliary disorders later in life and, hepatitis C, chronic hepatitis, hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis, and gallstones or cholangitis were seen more commonly in these women compared to the general population. [16] For fetal prognosis, see the section on the complication. Children born to women with ICP were also found to be at more risk of developing high body mass index and dyslipidemia at the age of 16. [37] The recurrence rate of ICP in subsequent pregnancies is high (60 to 70 percent). [20]

- Complications

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) can cause a significant risk for the fetus, and it is one of the treacherous risk factors for sudden fetal demise. [21] ICP is also associated with an increased risk of adverse obstetrical outcomes. Maternal bile acids cross the placenta and can accumulate in the fetus and amniotic fluid, causing fatal complications. Ovadia et al. conducted an aggregate meta-analysis, including 23 studies that compared perinatal outcomes of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (n=5557) vs. healthy controls (n=165136). The meta-analysis result shows evidence of the associations of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with increased fetal complications, as listed below. [35] [21]

- Sudden intrauterine demise (odds ratio 1.46 [95% CI 0.73–2.89])

- Meconium-stained amniotic fluid (2.60 [1.62–4.16])

- Spontaneous preterm birth (3.47 [3.06–3.95])

- Iatrogenic preterm birth (3.65 [1.94–6.85])

- Neonatal ICU admission (2.12 [1.48–3.03])

Maternal bile acids are transported through the placenta to the fetus and accumulate in the amniotic fluid to cause complications. The incidence of preterm labor also increases in women with ICP, the cause is unknown, but possibly related to bile acid accumulation in the uterine myometrium causing increased uterine activity. Sudden fetal death is the most concerning complication of ICP; the cause of fetal death is not well understood; still, it possibly has a relationship to the toxic effects of bile acids on the fetal heart, causing arrhythmias and chorionic vasospasm causing deprivation of maternal oxygenated blood to the fetus causing asphyxia. [38] The risk of fetal death increases with increasing levels of bile acids, notably higher with bile acid levels of more than100 micromol/L. [39]

- Consultations

Uncomplicated cases of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) are manageable by obstetrician-gynecologist; however, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist (MFM) and gastroenterologist consultation, when available, should always be considered in the patients with the complicated ICP and with other preexisting chronic liver diseases. A geneticist also can be consulted for sequence analysis when there is suspicion of the familial clustering of disease.

- Deterrence and Patient Education

In patients with a history of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), exogenous estrogen administration can lead to cholestasis. Estrogen-containing oral contraceptives should be avoided in these patients if possible or should be used in the smallest possible dose. Due to the high risk of recurrence of this disease, patients should be monitored cautiously with subsequent pregnancies.

- Pearls and Other Issues

Pruritis in the late second and third trimester is a cardinal symptom of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy along with elevated serum bile acids level.

Encephalopathy or other liver failure symptoms in ICP are rare and should prompt investigation for etiology other than ICP.

Combined oral contraceptive pills can cause cholestasis in some postpartum patients. A non-hormonal alternative for contraception merits consideration in such patients. Center for disease control and prevention okays to consider combined OCPs in patients with a history of ICP because of benefits outweigh the risks. [40]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) must be an interprofessional team approach. Typically, whenever feasible, an interprofessional team should include an obstetrician, maternal-fetal medicine specialist (MFM), gastroenterologist, anesthetist, and the nursing team.

A weekly biophysical profile for fetal health monitoring should take place in patients with ICP with elevated total bile acid level (over 100 micromol/L). Delivery between 36 to 37 weeks should be considered to avoid fetal complications in a patient with severely elevated total bile salt acid levels and other risk factors, as mentioned above. Once the condition gets diagnosed, the patient should be closely monitored by the nurse and obstetrician to ensure that the ICP is not worsening. A team approach to patient management is vital if one wants to improve outcomes.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Leela Sharath Pillarisetty declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Ashish Sharma declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Pillarisetty LS, Sharma A. Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis. [Updated 2023 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- [Clinical practice guidelines of the Team of Experts of the Polish Gynecological Society: management of the intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy]. [Ginekol Pol. 2012] [Clinical practice guidelines of the Team of Experts of the Polish Gynecological Society: management of the intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy]. Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B, Oleszczuk J, Marciniak B, Poreba R, Oszukowski P, Wielgoś M, Czajkowski K, Zespoł Ekspertów Polskiego Towarzystwa Ginekologicznego. Ginekol Pol. 2012 Sep; 83(9):713-7.

- Review Fetal complications due to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. [J Perinat Med. 2015] Review Fetal complications due to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Šimják P, Pařízek A, Vítek L, Černý A, Adamcová K, Koucký M, Hill M, Dušková M, Stárka L. J Perinat Med. 2015 Mar; 43(2):133-9.

- Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: A Case Report of Third-Trimester Onset of the Disease. [Cureus. 2022] Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: A Case Report of Third-Trimester Onset of the Disease. Bakhsh HA, Elawad MM, Alqahtani RS, Alanazi GA, Alharbi MH, Alahmari RA. Cureus. 2022 Nov; 14(11):e31926. Epub 2022 Nov 27.

- Review Effects of Intrahepatic Cholestasis on the Foetus During Pregnancy. [Cureus. 2022] Review Effects of Intrahepatic Cholestasis on the Foetus During Pregnancy. Sahni A, Jogdand SD. Cureus. 2022 Oct; 14(10):e30657. Epub 2022 Oct 25.

- Review Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. [Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018] Review Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. Wood AM, Livingston EG, Hughes BL, Kuller JA. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018 Feb; 73(2):103-109.

Recent Activity

- Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis - StatPearls Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

EPIDEMIOLOGY

● Incidence – ICP is the most common liver disease unique to pregnancy [ 1 ]. The incidence varies from <1 to 27.6 percent worldwide [ 2,3 ]. In the United States, the incidence is 0.8 percent [ 4 ] but ranged from 0.32 percent in Bridgeport Hospital, Connecticut [ 5 ] to 5.6 percent in a primarily Hispanic population in Los Angeles [ 6 ]. Across Europe, the incidence ranges from 0.5 to 1.5 percent, with the highest rates in Scandinavia [ 2 ]. In Indian Asian and Pakistani Asian populations, the incidence is 1.2 to 1.5 percent [ 7 ]. The Araucanos Indians in Chile have the highest incidence worldwide at 27.6 percent [ 8 ]. The reason for the wide variation in incidence is incompletely understood. Geographic variations may reflect differences in susceptibility between ethnic groups and differences in environmental factors [ 8,9 ].

● Seasonal occurrence and risk factors – For unknown reasons, the disease occurs more commonly in the winter months in some countries (eg, Sweden, Finland, Chile) [ 2 ].

A past history of ICP is a strong risk factor for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies (see 'Recurrence in subsequent pregnancies' below). Other risk factors include multiple gestation (twins 20.9 versus singletons 4.7 percent in one study from Chile [ 10 ]; triplets 43 percent versus twins 14 percent in one study from Finland [ 11 ]), chronic hepatitis C virus infection, personal or family history of intrahepatic cholestasis, and advanced maternal age [ 12 ].

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Cholestasis of pregnancy

To diagnose cholestasis of pregnancy, your pregnancy care provider usually will:

- Ask questions about your symptoms and medical history

- Do a physical exam

- Order blood tests to measure the level of bile acids in your blood and to check how well your liver is working

More Information

The goals of treatment for cholestasis of pregnancy are to ease itching and prevent complications in your baby.

Ease itching

To soothe intense itching, your pregnancy care provider may recommend:

- Taking a prescription medicine called ursodiol (Actigall, Urso, Urso Forte). This medicine helps to lower the level of bile acids in your blood. Other medicines to relieve itching also may be an option.

- Soaking itchy areas in cool or lukewarm water.

It's best to talk to your pregnancy care provider before you start any medicines for treating itching.

Monitoring your baby's health

Cholestasis of pregnancy can potentially cause complications to your pregnancy. Your pregnancy care provider may recommend close monitoring of your baby while you're pregnant.

Monitoring may include:

- Nonstress testing. During a nonstress test, your pregnancy care provider will check your baby's heart rate, and how much the heart rate increases with activity.

- Fetal biophysical profile (BPP). This series of tests helps monitor your baby's well-being. It provides information about your baby's heart rate, movement, muscle tone, breathing movements and amount of amniotic fluid.

While the results of these tests can be reassuring, they can't predict the risk of preterm birth or other complications associated with cholestasis of pregnancy.

Early delivery

Even if prenatal tests are within standard limits, your pregnancy care provider may suggest inducing labor before your due date. Early term delivery, around 37 weeks, may lower the risk of stillbirth. Vaginal delivery is recommended by induction of labor unless there are other reasons a cesarean section is needed.

Future birth control

A history of cholestasis of pregnancy may increase the risk of symptoms returning with contraceptives that contain estrogen, so other methods of birth control are generally recommended. These include progestin-containing contraceptives, intrauterine devices (IUDs) or barrier methods, such as condoms or diaphragms.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Home remedies may not offer much relief for itching due to cholestasis of pregnancy. But it doesn't hurt to try these soothing tips:

- Cool baths, which may make the itching feel less intense

- Oatmeal baths, creams or lotions, which may soothe the skin

- Icing a particularly itchy patch of skin, which may briefly reduce the itch

Alternative medicine

Research into effective alternative therapies for treating cholestasis of pregnancy is lacking, so pregnancy care providers generally don't recommend them for this condition.

Several studies have looked at whether the supplement S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) might ease itching related to cholestasis of pregnancy. But data are conflicting. When compared with ursodiol in early trials, SAMe didn't work as well. It may be safe when used for a short time during the third trimester. But the risks to mother and baby aren't well known. Often, this medicine isn't recommended.

The safety of other alternative therapies hasn't been confirmed. Always check with your health care provider before trying an alternative therapy, especially if you're pregnant.

Preparing for your appointment

It's a good idea to be prepared for your appointment with your obstetrician or pregnancy care provider. Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment, and what to expect.

What you can do

To prepare for your appointment:

- Make a list of any symptoms you have. Include all of your symptoms, even if you don't think they're related.

- Make a list of any medicines, vitamins, herbs and other supplements you take. Make note of doses and how often you take them.

- Have a family member or close friend go with you, if possible. You may be given a lot of information at your visit.

- Take a notebook with you. Use it to make notes of important information during your visit.

- Make a list of questions you'll ask. This can help you remember important points you want to cover.

Some questions to ask may include:

- What is likely causing my symptoms?

- Is my condition mild or severe?

- How does my condition affect my baby?

- What is the best course of action?

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- Are there any alternatives to the treatment that you're suggesting?

- Are there any restrictions that I need to follow?

- Will I need to have labor induced early?

- Do you have any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment or if you don't understand something.

What to expect from your doctor

To better understand your condition, your pregnancy care provider might ask questions, such as:

- What symptoms do you have?

- How long have you had symptoms?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- Can you feel your baby moving?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- What makes your symptoms worse?

- Have you been diagnosed with cholestasis during any previous pregnancies?

Cholestasis of pregnancy can be a worrisome diagnosis. Work with your pregnancy care provider to make sure that you and your baby receive the best possible care for this condition.

- FAQs. Skin conditions during pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/skin-conditions-during-pregnancy. Accessed Aug. 26, 2022.

- Lindor KD, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 26, 2022.

- Lee RH, et al. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #53: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.002.

- Walker KF, et al. Pharmacological interventions for treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000493.

- Xiao J, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021; doi:10/1155/2021/6679322.

- Smith DD, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000495.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Gastrointestinal and hepatic disorders in the pregnant patient. In: Schlesinger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Aug. 26, 2022.

- SAMe. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Aug. 26, 2022.

- FAQs. Special tests for monitoring fetal well-being. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/special-tests-for-monitoring-fetal-well-being. Accessed Aug. 28, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Practice Bulletins — Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 229: Antepartum fetal surveillance. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2021; doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004410.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 11, 2022.

Associated Procedures

Products & services.

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- A Book: Obstetricks

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Published: 9 August 2022

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This information is for you if you have been diagnosed with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), also known as obstetric cholestasis.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this leaflet. Your care should be personalized, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms .

- ICP is a condition that affects how your liver works when you are pregnant. It is sometimes called obstetric cholestasis.

- It usually happens towards the end of your pregnancy and will get better after you have given birth.

- ICP can make your skin very itchy but you will not have a rash.

- Your ICP will be monitored with regular blood tests to check your liver function and the levels of bile acids in your blood.

- If you develop ICP there is an increased chance that your baby may be born early.

- For a few women with severe ICP, there may be an increased chance of stillbirth.

ICP is a condition that affects your liver during pregnancy. ICP causes a build-up of bile acids in your body. Bile acids are made in your liver and they help you to digest fat and fat soluble vitamins. The main symptom of ICP is itching of your skin without any rash. ICP usually starts towards the end of the pregnancy ( the third trimester ) but can happen earlier. It should get better when your baby has been born.

ICP is uncommon. In the UK, it affects about 7 in 1000 women (less than 1%). It is more common among women of Indian-Asian or Pakistani-Asian origin, with up to 15 in 1000 women (1.5%) affected. It is often not clear why it develops in one pregnancy and not another.

ICP can be a very uncomfortable condition. It does not have any serious consequences for your health during pregnancy but can be very distressing. If you experience anxiety or low mood because of ICP discuss this with your healthcare professional who can arrange additional support.

Itching can start at any time during pregnancy, but usually begins after 28 weeks. It can vary from mild to intense and persistent and can sometimes be very distressing. It may include the palms of your hands or soles of your feet. The itching tends to be worse at night and can disturb your sleep.

There is no rash with ICP. The itching will get better soon after birth and causes you no long-term health problems.

Rarely, women with ICP can develop jaundice. This is where your skin and eyes become yellow because of liver changes. Jaundice will get better after you have had your baby.

Pre-eclampsia

You may be more likely to develop pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure and protein in your urine during pregnancy) or to have gestational diabetes and your healthcare professional will advise you what checks you may need for these conditions. Further information can found in the RCOG Patient Information Leaflets: Pre-eclampsia and Gestational diabetes .

Itching is very common in pregnancy, affecting 25 in 100 women (25%). Most women who have itching in pregnancy will not have ICP. However, itching can be the first sign of ICP and if you experience this, you should tell your health care professional.

Examination of your skin

Your skin will be examined to check whether your itching is related to a skin condition, such as eczema. It is possible that you may have more than one condition.

Blood tests

You will be offered blood tests to help diagnose ICP. These include:

- Liver function tests (LFTs). These are blood tests that look at how well your liver is working. Some of these can be raised in ICP.

- Bile acid This is a blood test that measures the level of bile acids in your blood. Bile acids are raised in ICP. Your bile acid levels can be abnormal even if your liver function tests are normal. Bile acid levels can also be raised in other conditions apart from ICP.

Some women may have itching for days or weeks before their blood tests become abnormal. If your itching persists and no other cause is found, your liver function tests and bile acids should be repeated.

If your symptoms are unusual, start very early in your pregnancy or don’t get better after your baby is born, you may be offered further investigations including more blood tests and a scan of your liver. You may also be referred to a liver specialist. This is to make sure that you don’t have another cause for your itching and raised bile acids.

There is an increased chance that your baby may pass meconium (open their bowels) before they are born.

This makes the water around your baby a green or brown colour. Your baby can become unwell if meconium gets into their lungs during labour.

There is an increased chance of you having an early birth.

The chance of having your baby preterm (less than 37 weeks) is higher if you have ICP. This may be because you go into labour naturally or because your healthcare team advises you to give birth early.

There are no known long term health risks to your baby.

However there is a small increased chance that your baby will need to go to the neonatal unit when they are born, especially if they have been born early.

Your chance of having a stillbirth depends on the level of bile acids found in your blood as well as any other pregnancy complications you may be experiencing.

If your bile acid levels are between 19 and 39 micromol/L (Mild ICP) and you do not have any other risk factors, the chance of you having a stillbirth is no different to someone who doesn’t have ICP.

If your bile acid levels are between 40 and 99 micromol/L (Moderate ICP), and you do not have any other risk factors, then the chance of you having a stillbirth is similar to someone who doesn’t have ICP until you are 38-39 weeks’ pregnant.

If your bile acid levels are 100 micromol/L or more (Severe ICP), your chance of having a stillbirth is higher than someone who doesn’t have ICP and is around 3%. Most of these stillbirths happen after 36 weeks of pregnancy.

If you have other factors (such as gestational diabetes and/ or pre-eclampsia) or are having a multiple pregnancy (twins or triplets) you may have a higher chance of stillbirth and this may affect when your healthcare team recommend that you give birth.

Once you have been diagnosed with ICP, you should be under the care of an obstetrician . Your blood tests will usually be repeated after one week and an individualised plan of care will be made for you depending on your circumstances. In some women, the level of bile acids may return to normal with no treatment, and your healthcare professionals may check again whether you definitely have ICP.

You should keep a close eye on your baby’s movements and if you are worried, you should go to your local maternity unit for a checkup straight away.

You do not need any additional scans of the baby because you have ICP.

Whether you are advised to have your baby in a consultant-led maternity unit with a neonatal unit will depend on your bile acid levels.

When your baby is born your ICP will get better.

Treatments to improve your itching are of limited benefit but might include:

- Skin creams such as aqueous cream, with or without the addition of menthol

- Antihistamines, which may help you sleep at night

- Some women have found that having cool baths and wearing loose-fitting cotton clothing helps to reduce the itching.

- There is a medication called ursodeoxycholic acid, which may slightly reduce itching in a small number of women.

There is no treatment available that helps your baby or that will make your bile acid levels better. Ursodeoxycholic acid may reduce your chance of giving birth prematurely but it does not prevent stillbirth.

A daily dose of vitamin K may be recommended for a small number of women as rarely ICP may affect blood clotting. Most women will not need this.

The recommended timing of your baby’s birth will depend on the level of bile acids in your blood and also whether you have any additional risk factors such as multiple pregnancy , gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia . To reduce your chance of having a stillbirth, you might be asked to consider a planned birth rather than waiting to go into labour naturally.

If you are having one baby and your pregnancy has had no other complications, the following recommendations apply to you:

- Planned birth by the time of your due date (40 weeks) may be considered if your bile acids are raised between 19 and 39 micromol/L. If you have no other risk factors you may also consider waiting to go into labour as your risk of stillbirth is no different to someone without ICP.

- Planned birth at 38-39 weeks’ gestation may be recommended if your bile acid levels are 40-99 micromol/L and if you have no other risk factors.

- Planned birth at 35-36 weeks’ gestation may be recommended if your bile acid levels are 100 micromol/L or more.

Your health care professional will discuss your options with you depending on your individual situation, so that you can make an informed choice about how you give birth. Your options will be to choose an induction of labour , to choose a planned caesarean birth or to wait until you go into labour naturally. You do not need to have a planned caesarean birth just because you have ICP.

A plan will be made for monitoring your baby’s heartbeat in labour depending on your circumstances and preferences. If your bile acids are more than 100 micromol/L or if you have other risk factors, you will be advised to have continuous monitoring of your baby’s heart using a machine called a CTG .

Having ICP does not affect your pain relief options in labour. For more information about pain relief during labour see the Labour Pains website ( labourpains.org ) from the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association.

ICP symptoms get better after birth. It can take several weeks for your blood tests to return to normal. At your 6-week postnatal check your healthcare professional should make sure that your itching has gone away and arrange blood tests to make sure that your liver blood tests and bile acids have returned to normal. If you still have symptoms or if your blood tests have not returned to normal by this time, you may be referred to a specialist for further investigations.

- There is an increased chance that you will have ICP again in future pregnancies.

- Your liver function tests and bile acids should be checked at the start of any future pregnancies and you should tell your healthcare professional if you develop any symptoms.

- ICP does not affect your choice of contraception once your liver blood tests and bile acids have returned to normal. If you take an estrogen containing contraceptive such as the combined pill and develop itching you should see your health care professional immediately for review.

- If you have had ICP, it is still possible for you take HRT in the future.

Further information

- ICP Support

- British Liver Trust

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions , if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

- https://aqua.nhs.uk/resources/shared-decision-making-case-studies/

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 43 Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy published in August 2022. The guideline contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

Please give us feedback by completing our feedback survey:

- Members of the public – patient information feedback

- Healthcare professionals – patient information feedback

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy Green-top Guideline

- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2024

Reproductive factors and subsequent pregnancy outcomes in patients with prior pregnancy loss

- Xin Yang 1 ,

- Fangxiang Mu 1 ,

- Jian Zhang 1 ,

- Liwei Yuan 1 ,

- Wei Zhang 1 ,

- Yanting Yang 1 &

- Fang Wang 1

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 24 , Article number: 219 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

149 Accesses

Metrics details

At present, individualized interventions can be given to patients with a clear etiology of pregnancy loss to improve the subsequent pregnancy outcomes, but the current reproductive status of the patient cannot be changed. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between female reproductive status and subsequence pregnancy outcome in patients with prior pregnancy loss (PL).

A prospective, dynamic population cohort study was carried out at the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University. From September 2019 to February 2022, a total of 1955 women with at least one previous PL were enrolled. Maternal reproductive status and subsequent reproductive outcomes were recorded through an electronic medical record system and follow-up. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between reproductive status and the risk of subsequent reproductive outcomes.

Among all patients, the rates of subsequent infertility, early PL, late PL, and live birth were 20.82%, 24.33%, 1.69% and 50.77% respectively. In logistic regression, we found that age (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.13) and previous cesarean delivery history (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.27–4.76) were risk factors for subsequent infertility in patients with PL. Age (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.10), age at first pregnancy (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.10), BMI (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.11), previous PL numbers (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.57) and without pre-pregnancy intervention (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.35–2.24) were risk factors for non-live birth. Age (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.09), age at first pregnancy (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.09), BMI (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.11), previous PL numbers (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.31) and without pre-pregnancy intervention (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.65–2.84) were risk factors for PL.

Conclusions

The reproductive status of people with PL is strongly correlated with the outcome of subsequent pregnancies. Active pre-pregnancy intervention can improve the subsequent pregnancy outcome.

Trial registration

This study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry with the registration number of ChiCTR2000039414 (27/10/2020).

Peer Review reports

Pregnancy loss (PL) is defined as the spontaneous demise of a pregnancy before the fetus reaches viability, which is a significant negative life event and impacts 10–15% of clinically recognized pregnancies. Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) refers to two or more consecutive PL episodes with the same sexual partner, accounting for approximately 1–2% [ 1 , 2 ]. There are many reasons for the occurrence of RPL, including genetic abnormalities (fetal genetic abnormalities and parental genetic abnormalities), reproductive tract anatomical abnormalities, immune diseases, endocrine diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome, thrombotic disorders, and infections, but about 40-50% of the etiologies remain unexplained, Molecular mechanisms have not been fully explored, and these are defined as unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss (URPL) [ 3 , 4 ]. In addition, PL was defined as primary if there without a previous ongoing pregnancy (viable pregnancy) beyond 24 weeks gestation, otherwise it was defined as secondary [ 1 ]. PL is a serious adverse event in life that greatly affects the physical and mental health of women. Women who experience PL have increased rates of anxiety and depression and other psychological disorders. It is reported that in RPL, the incidence of anxiety and depression in women can be as high as 47.7% and 51.7%, respectively [ 5 ]. At the same time, anxiety, and depression symptoms in women in early pregnancy are also risk factors for RPL [ 6 ].

In addition to influencing the etiology of pregnancy loss, personal factors (age, first pregnancy age, BMI) and reproductive status (total pregnancy number, pregnancy loss number, pregnancy type, induced abortion, live birth, ectopic pregnancies, molar pregnancy and, etc.) of the patient greatly influence the reproductive outcome [ 7 ]. Studies have found that age, the number of previous pregnancy loss and BMI are important influencing factors in pregnancy loss. The relationship between age and reproductive outcomes is well established, age-adjusted odds ratios for pregnancy loss were found to increase after each pregnancy loss and to be as high as 63% among women who had experienced six or more miscarriages [ 8 ]. However, the relationship between BMI and pregnancy outcomes remains controversial. Zhang et al. found that BMI ≥ 24.0 was associated with an increased risk of RPL. However, Lo and colleagues demonstrated that maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) significantly increased the risk of the disease miscarriage in couples with URPL, while there was no increased risk in women with overweight. Maconochie et al. found underweight (BMI < 18.5) was significantly associated with sporadic first trimester miscarriage, However, Lo et al. found that no increased risk of subsequent PL in women who are underweight as compared to women with normal BMI [ 9 , 10 ].

Some differences were also found between primary and secondary PL, with secondary PL and ≥ 4 prior PL strongly associated with HLA-DRB1*03, and secondary PL of a boy from a previous birth has a negative impact on the outcome of subsequent pregnancies [ 11 , 12 ]. Notably, patients with secondary PL had higher levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in peripheral blood than primary PL, while high plasma TNF-α levels are reported to increase the risk of miscarriage in women with RPL [ 13 ]. This may indicate a higher risk of miscarriage in patients with secondary PL. It is also controversial whether previous induced abortion have an effect on subsequent PL. Infante-Rivard et al. found that induced abortion was a risk factor for subsequent PL, while Chung et al. found no statistical difference between induced abortion and PL risk [ 14 , 15 ].

At present, some studies have found that reproductive history does not compromise subsequent live birth and perinatal outcomes in patients undergoing first frozen embryo transfer in in-vitro fertilization [ 16 ]. Whereas, a registry-based cohort study revealed that obstetric complications (still birth, ectopic pregnancies, and pregnancy losses) had a negative effect on the chance of live birth in the next pregnancy, and the identical pregnancy outcomes immediately preceding the next pregnancy had a larger impact than the total number of any outcome [ 17 ]. However, no studies have comprehensively evaluated reproductive factors and pregnancy outcomes in patients with prior PL.

Currently, individualized interventions can be given to patients with a clear etiology of PL to improve the outcome of subsequent pregnancies, but the current reproductive status of the patient cannot be changed. Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between reproductive factors and pregnancy outcomes in patients with prior PL.

Study population

A prospective, dynamic population cohort study was carried out at a university-affiliated fertility center. The cohort began in September 2019 and enrolled 1955 patients through February 2022. Written informed consent was obtained at the time of recruitment. Inclusion criteria: patients who had experienced at least one PL (diagnosis of PL according to the ESHRE, which spontaneous abortions prior to 24 weeks of gestation including biochemical pregnancy, and early PL was defined as PL before 10 weeks of gestational age [ 1 ]) and aged 18–42 years. Exclusion criteria: Patients who did not undergo any clinical examination after presentation and patients with severe psychiatric disorders who were not able to voluntarily enroll for subsequent follow-up. Patients are carefully asked for their reproductive history and personal demographic information when they join. If a patient had experienced a pregnancy loss and was currently non-pregnant at the time of presentation, an individualized pre-pregnancy intervention was given based on the results of the clinical examination. Pre-pregnancy interventions include improvements in thyroid function, correction of prothrombotic status, treatment of immune system disorders such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, folic acid supplementation, and advice on maintaining a healthy lifestyle. If a patient had experienced a pregnancy loss and was already pregnant at the time of presentation, pre-pregnancy intervention was lacking. During pregnancy, patients receive individualized treatment based on clinical symptoms and laboratory test results, including progesterone supplementation, aspirin, low molecular weight heparin, hydroxychloroquine, etc.

Data collection

The population data was obtained from the Reproductive Medicine Middle School at the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University. Demographic information included age (< 25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥ 35), age at first pregnancy, BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–23.9, 24.0-27.9, ≥ 28), education and ethnicity. Pregnancy status data included the patient’s total number of previous pregnancies, the history of induced abortion, live birth (delivery method), birth defects, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole, previous PL numbers and pregnancy loss type (primary or secondary). Age at menarche, menstrual cycle, dysmenorrhea status and history of pelvic surgery were also collected. Each patient was followed up every 6 months after the first visit to track the patient’s pregnancy status, most recently in August 2022. At follow-up, we collected the outcome of the next pregnancy, the gestational age, delivery method, gender, birth weight of the live birth and whether the newborn was admitted to a neonatology department. Whether the mother had gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, intrauterine cholestasis during pregnancy, and premature rupture. In addition, there are some patients in the follow-up process, both spouses want to have children, have normal sexual life, more than a year without contraception, but still do not conceive, we defined it as infertility [ 18 ]. We obtained information through a medical records registry and telephone follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the proportion and mean ± standard deviation of the demographic characteristics. Independent sample t test was used to compare the differences between the two groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the differences among the three groups. Categorical data were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The P < 0.1 of the variables were included in the Logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratio (OR) between research factors and risk of pregnancy outcome.

Characteristics of participants

From all participants, 1955 patients were enrolled into our database between September 2019 to February 2022. Table 1 shows that the average age is 30.51 ± 4.41 years and the average of first pregnancy age is 26.41 ± 3.74 years. The proportion of overweight [(BMI 24.0-27.9 kg/m 2 )/ obesity (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m 2 ) was diagnosed according to the Working Group on Obesity in China [ 19 ])] was 26.13%. Only one PL accounted for 40.87% and the RPL accounted for 59.13%. Primary PL accounted for 78.31%.

The total number of cumulative pregnancies (defined as the total number of pregnancies at the time of the first visit for all patients, excluding the current already pregnant at the time of the first visit) was 4606, of which 3696 were PLs, 445 were live births, 251 were induced abortions, 101 were ectopic pregnancies, 20 were hydatidiform moles, 75 were birth defects, and 18 were others (Supplementary Fig. 1 ).

At the time of the first visit, 1,593 patients were currently non-pregnant, preparing for their next pregnancy and seeking help. There were also 362 patients who had also experienced at least one previous PL but sought treatment after their current pregnancy was confirmed, who were already pregnant at the time of the first visit.

Reproductive status in different age, BMI, pregnancy loss numbers groups in the study

The survey showed that in different age groups (< 25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥ 35), the BMI, total pregnancy numbers, PL numbers and first pregnancy age were increased with age and the difference was statistically significant ( P < 0.001). With the increase of age, the proportion of the types of secondary PL and the proportion of those who experienced induced abortion, live birth, cesarean section and pelvic surgery are increased ( P < 0.001). The rate of ectopic pregnancies was higher in the 30–35 age group. With the increase of age, the proportion of women with regular periods increases, while the number of women with moderate or severe dysmenorrhea decreases (Supplementary Table 1 ). In different BMI groups (< 18.5 kg/m 2 , 18.5–23.9 kg/m 2 , 24.0-27.9 kg/m 2 , ≥ 28 kg/m 2 ), there were differences in patients age and first pregnancy age. In addition, with the increase of BMI, the age of menarche was slightly earlier ( P = 0.003). And the incidence of pelvic surgery was lowest in the normal-weight group ( P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2 ). In different PL numbers groups (1, 2, 3, ≥ 4), the total pregnancy numbers and age were increased with the number of PL, the first pregnancy age was decreased with the number of PL ( P < 0.001). With the increase of the number of PL, the proportion of secondary PL, live birth and regular menstruation are increased ( P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3 ).

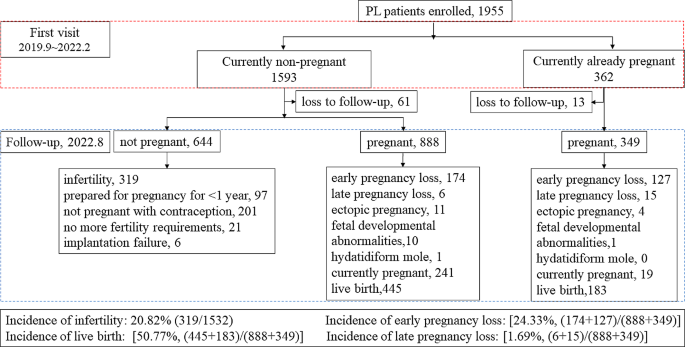

The follow-up results of 1955 patients

Figure 1 . shows that during follow-up, 74 cases were refused to accept follow-up. Of the remaining 1881 patients, 1532 were non-pregnant at the time of consultation and 349 were already pregnant at the time of consultation. In a follow-up study of 1,532 non-pregnant women, we found that 644 patients who were not pregnant, of whom 319 patients had been diagnosed as infertile for more than 1 year without contraception. A total of 888 women experienced a second pregnancy, of which 174 had early PL, 6 had late PL, and 445 had a live birth. In the follow-up study of 349 pregnant women, we found that there were 127 women experienced their next early PL, 15 had late PL, and 183 had a live birth. Among all patients, the incidence of subsequent infertility was 20.82% (319/1532), the incidence of early PL was 24.33% [(174 + 127)/ (888 + 349)], and the incidence of late PL was 1.69% [(6 + 15)/ (888 + 349)]. The live birth rate was 50.77% [(445 + 183)/ (888 + 349)].

Flow diagram of the patients selected for the study

Maternal and infant complications in patients with live birth in a subsequent pregnancy

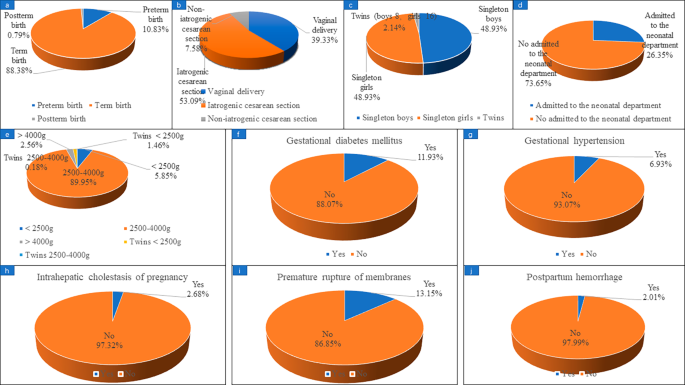

Fig. 2 . shows that, in the study, 628 confirmed live births were reported as of August 2022, of which preterm birth occurred in 68 patients, accounting for 10.83%. A total of 567 women reported their mode of delivery, including 223 (39.33%) vaginal delivery and 344 (60.67%) cesarean section. There were 43 cases of cesarean section due to patients’ request which called non-iatrogenic cesarean Sect. (43/567, 7.58%) and 301 cases of cesarean section due to medical reasons which called iatrogenic cesarean Sect. (301/567, 53.09%). The gender of the newborns was reported in 562 cases, including 275 singleton boys and 275 singleton girls. 461 cases reported whether they had gestational diabetes mellitus, of which 55 cases were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus, accounting for 11.93%; 476 cases reported whether they had gestational hypertension, and 33 cases (6.93%) were diagnosed. 447 cases were reported whether they had intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and 12 cases (2.68%) were diagnosed. 479 cases reported whether they had premature rupture, and 63 cases were confirmed, accounting for 13.15%. 298 cases reported whether they had postpartum hemorrhage, and 6 cases were confirmed, accounting for 2.01%.

Maternal and infant complications in patients with live birth in subsequent pregnancy. (a) preterm birth; (b) delivery method; (c) gender of newborn; (d) newborns admitted to the neonatal department; (e) neonatal weight; (f) gestational diabetes mellitus; (g) gestational hypertension; (h) intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy; (i) premature rupture; (j) postpartum hemorrhage

Whether the previous pregnancy status affects the patient’s subsequent pregnancy?

During follow-up, 319 patients were diagnosed with infertility after their last pregnancy loss, and 1237 patients were able to achieve a successful pregnancy. There was a significant difference in age between the infertility group and the successful pregnancy group (31.02 ± 4.79 vs. 30.16 ± 4.13, P < 0.001). There were also statistical differences between the infertility and successful pregnancy groups in the type of PL, the previous live birth and the delivery method, the previous birth defects. The age of first pregnancy and BMI were different, but not statistically significant. There were no statistical differences in the total pregnancy numbers, the previous PL numbers, the history of induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole, menarche age, menstrual cycle, dysmenorrhea or not, previous pelvic surgery, the last pregnancy termination method between the infertility group and the successful pregnancy group (Table 2 ). The P < 0.1 of the variables were included in the logistic regression and found that, increasing age (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.13) and previous cesarean delivery history (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.27–4.76) were risk factors for subsequent infertility in patients with PL (Table 3 ).

Whether the previous pregnancy status affects the live birth in subsequent pregnancy?

Of the 1237 women who had subsequent pregnancies, 977 had final pregnancy outcomes, including 628 live births and 349 non-live births. We found that the age, age at first pregnancy, BMI, and previous pregnancy loss numbers were lower in the live birth group than in the non-live birth group. Pre-pregnancy intervention increased live births compared to without pre-pregnancy intervention. Total pregnancy numbers were different but not statistically significant between the live birth group and the non-live birth group. There were no statistical differences in the total pregnancy numbers, the pregnancy interval, the pregnancy type, the history of induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole, menarche age, menstrual cycle, dysmenorrhea or not, previous pelvic surgery, the last pregnancy termination method between the live birth group and the non-live birth group (Table 2 ). In logistic regression analysis, we found that age (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.10), age at first pregnancy (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.10), BMI (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.11), previous pregnancy loss numbers (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.57) and without pre-pregnancy intervention (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.35–2.24) were risk factors for non-live birth (Table 4 ).

Whether the previous pregnancy status affects the pregnancy loss in subsequent pregnancy?

Of the 1237 women who had subsequent pregnancies, 322 had confirmed subsequent pregnancy losses and 756 had pregnancies that were > 24 W, which was considered an ongoing pregnancy. We found that age, age at first pregnancy, BMI, and previous pregnancy loss numbers were higher in the pregnancy loss group than in the ongoing pregnancy group. Pre-pregnancy intervention decreased pregnancy loss compared to without pre-pregnancy intervention. There were no statistical differences in the total pregnancy numbers, the pregnancy interval, the pregnancy type, the history of induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole, menarche age, menstrual cycle, dysmenorrhea or not, previous pelvic surgery, the last pregnancy termination method between the pregnancy loss group and the ongoing pregnancy group (Table 2 ). In logistic regression analysis, we found that age (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.09), age at first pregnancy (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.09), BMI (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.11), previous pregnancy loss numbers (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.31) and without pre-pregnancy intervention (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.65–2.84) were risk factors for PL (Table 5 ).

The incidence of PL has been increasing in recent years, but few studies have summarized the reproductive status of patients with previous PL. Our study summarized the distribution of pregnancies in 1955 pregnancy loss patients and followed them for subsequent pregnancy outcomes. We found that patients with PL also had other adverse pregnancy events, such as birth defects (3.73%), ectopic pregnancy (4.65%) and hydatidiform mole (1.02%). But none of this have an effect on subsequent pregnancies in our analysis. Of the 1955 women with PL, 20.46% had a previous live birth, of which 32.91% were delivered by cesarean section, which increased the risk of subsequent infertility in women with PL, but had no effect on the ongoing pregnancy and live birth in subsequent pregnancies. In recent years, the relationship between cesarean scar uterus and subsequent secondary infertility has been gradually recognized, but the specific mechanism is not clear [ 20 , 21 ]. Nobuta et al. found that a cause of secondary infertility in women with cesarean scar syndrome may be chronic inflammation of the uterine cavity [ 22 ]. We also found that prior induced abortion, mode of termination of the last pregnancy, age at menarche, menstrual cycle, and level of dysmenorrhea had no effect on subsequent pregnancy outcomes. However, previous studies have found that the risk of spontaneous abortion decreases with the increase in the number of induced abortions among female workers in the Jinchang Cohort [ 7 ]. This is not consistent with our results. The possible reason is that the reference population was derived from all female workers in the Jinchang cohort in China, most of whom had normal reproductive function. In contrast, all the patients in our study were women of childbearing age who had experienced at least one pregnancy loss.

Our study found that age is an important risk factor in the occurrence of infertility after PL, also resulting in an increased risk of pregnancy loss and a decreased live birth in subsequent pregnancies. The association between female age and RPL has been consistently demonstrated in several studies. The age-related risk of pregnancy loss followed a J-shaped curve, with the lowest risk at ages 25 to 29 years, an increase in risk among women 30 to 35 years of age, and then a sharp rise in risk among women 40 to 44 years of age [ 8 ].

Age at first pregnancy, BMI, and the number of previous PL were also key indicators of subsequent pregnancy failure. Based on a computer-simulated fertility model, couples should start trying to conceive when the woman is 31 or less to have at least a 90% chance of having a two-child family, and if IVF is not feasible, couples should start planning no later than 27. In order to achieve a one-child family, couples should start trying before the age of 32, or 35 if IVF is an option [ 23 ].

Our study found that approximately 26.13% (140/658) of prior PL patients were overweight/obesity, which is higher than the pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity rates found in a birth cohort in Shanghai (19.06% (106/556)) [ 24 ]. But in the USA, a 2009–2010 survey indicated that 55.8% of women of childbearing age were overweight or obese, defined as having a BMI of 25 or higher, significantly higher than our research found [ 25 ]. There are also variations in the threshold of BMI for pregnancy. Zhang et al. reported that, a BMI of 24.0 kg/m 2 or greater was associated with an increased risk of RPL, but Lo and colleagues demonstrated that maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m 2 ) significantly increased the risk of miscarriage in couples with unexplained RPL and there was no increased risk in women with overweight and underweight [ 10 , 26 ]. This suggests that BMI reference ranges should be tailored to patient geographic region and disease status.

The impact of the number of previous PL on the chance of live birth has been investigated in several cohort studies. The risk of PL during a second pregnancy is associated with the number of PL. The risk is about 20% after one PL, 28% after two PLs, and 43% after three or more PLs [ 27 , 28 ]. In a nested cohort, it was demonstrated that the number of prior miscarriages was a determinant both for time to live birth and cumulative incidence of live birth [ 29 , 30 ]. It is worth noting that for secondary URPL, only consecutive PL after the birth influenced the subsequent prognosis, while the number of losses prior to the birth did not affect the prognosis in the next pregnancy [ 31 ].

Finally, we found that individualized pre-pregnancy intervention increased the rate of live birth and decreased the rate of PL in subsequent pregnancies. These individualized pre-pregnancy interventions were based on patient clinical examination findings, including treatment for endocrine abnormalities, prethrombotic state, immune disorders, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and lifestyle modification before subsequence pregnancy. Study found that a combination of heparin and aspirin treatment can improve the APS and recurrent pregnancy loss of the pregnancy outcomes of women but add corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), cannot improve live birth rates, and increase the risk of obstetric diseases, such as premature delivery, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, enter the neonatal intensive care unit [ 32 , 33 ]. Patients with RPL who have overt hypothyroidism before or during the first trimester should be treated with levothyroxine (thyroid hormone replacement therapy). However, levothyroxine did not improve pregnancy outcomes in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism [ 34 ]. For immune diseases, the treatment of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) is still controversial [ 35 , 36 ]. At present, there are still some controversies and uncertainties in the treatment of PL patients, and further standardized treatment is needed. In addition, RPL is an independent risk factor for women’s long-term increased incidence of malignant tumors (such as breast cancer and cervical cancer) and cardiovascular diseases [ 37 ]. Therefore, we should give individualized pre-pregnancy intervention to patients with PL not only to improve the subsequent pregnancy outcome, but also to potentially reduce the risk of long-term complications.

Our study still has some limitations. We did not capture complications for all patients who had live births. Due to the individualization of pre-pregnancy treatment, the diagnosis and treatment process were not recorded in detail. However, we are in the process of establishing pregnancy-loss specific cohorts, and the management of future patients will be more careful.

Maternal age and a history of cesarean section in a previous pregnancy are key factors for subsequent failure to achieve a successful pregnancy in patients with PL. Maternal age, age at first pregnancy, BMI, number of previous PL and pre-pregnancy treatment are the key factors affecting subsequent PL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Bender Atik R, Christiansen OB, Elson J, Kolte AM, Lewis S, Middeldorp S, Nelen W, Peramo B, Quenby S, Vermeulen N, Goddijn M. ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod open. 2018;2018(2):hoy004. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoy004 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ruderman RS, Yilmaz BD, McQueen DB. Treating the couple: how recurrent pregnancy loss impacts the mental health of both partners. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(6):1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.165 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Coomarasamy A, Dhillon-Smith RK, Papadopoulou A, Al-Memar M, Brewin J, Abrahams VM, Maheshwari A, Christiansen OB, Stephenson MD, Goddijn M, Oladapo OT, Wijeyaratne CN, Bick D, Shehata H, Small R, Bennett PR, Regan L, Rai R, Bourne T, Kaur R, Pickering O, Brosens JJ, Devall AJ, Gallos ID, Quenby S. Recurrent miscarriage: evidence to accelerate action. Lancet (London England). 2021;397(10285):1675–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00681-4 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dimitriadis E, Menkhorst E, Saito S, Kutteh WH, Brosens JJ. Recurrent pregnancy loss. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2020;6(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00228-z .

Voss P, Schick M, Langer L, Ainsworth A, Ditzen B, Strowitzki T, Wischmann T, Kuon RJ. Recurrent pregnancy loss: a shared stressor—couple-orientated psychological research findings. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(6):1288–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.08.1421 .

Wang Y, Meng Z, Pei J, Qian L, Mao B, Li Y, Li J, Dai Z, Cao J, Zhang C, Chen L, Jin Y, Yi B. Anxiety and depression are risk factors for recurrent pregnancy loss: a nested case-control study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01703-1 .

Hu X, Miao M, Bai Y, Cheng N, Ren X. Reproductive factors and risk of spontaneous abortion in the Jinchang Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112444 .

Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, Weinberg CR, Håberg SE. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register based study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2019,364l869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l869 .

Maconochie N, Doyle P, Prior S, Simmons R. Risk factors for first trimester miscarriage–results from a UK-population-based case-control study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;114(2):170–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01193.x .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lo W, Rai R, Hameed A, Brailsford SR, Al-Ghamdi AA, Regan L. The effect of body mass index on the outcome of pregnancy in women with recurrent miscarriage. J Fam Commun Med. 2012;19(3):167–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.102316 .

Article Google Scholar

Kruse C, Steffensen R, Varming K, Christiansen OB. A study of HLA-DR and -DQ alleles in 588 patients and 562 controls confirms that HLA-DRB1*03 is associated with recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod (Oxford England). 2004;19(5):1215–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh200 .