Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods

Published on April 12, 2019 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When collecting and analyzing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions.

Quantitative research is at risk for research biases including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Common qualitative methods include interviews with open-ended questions, observations described in words, and literature reviews that explore concepts and theories.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs. quantitative research, how to analyze qualitative and quantitative data, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

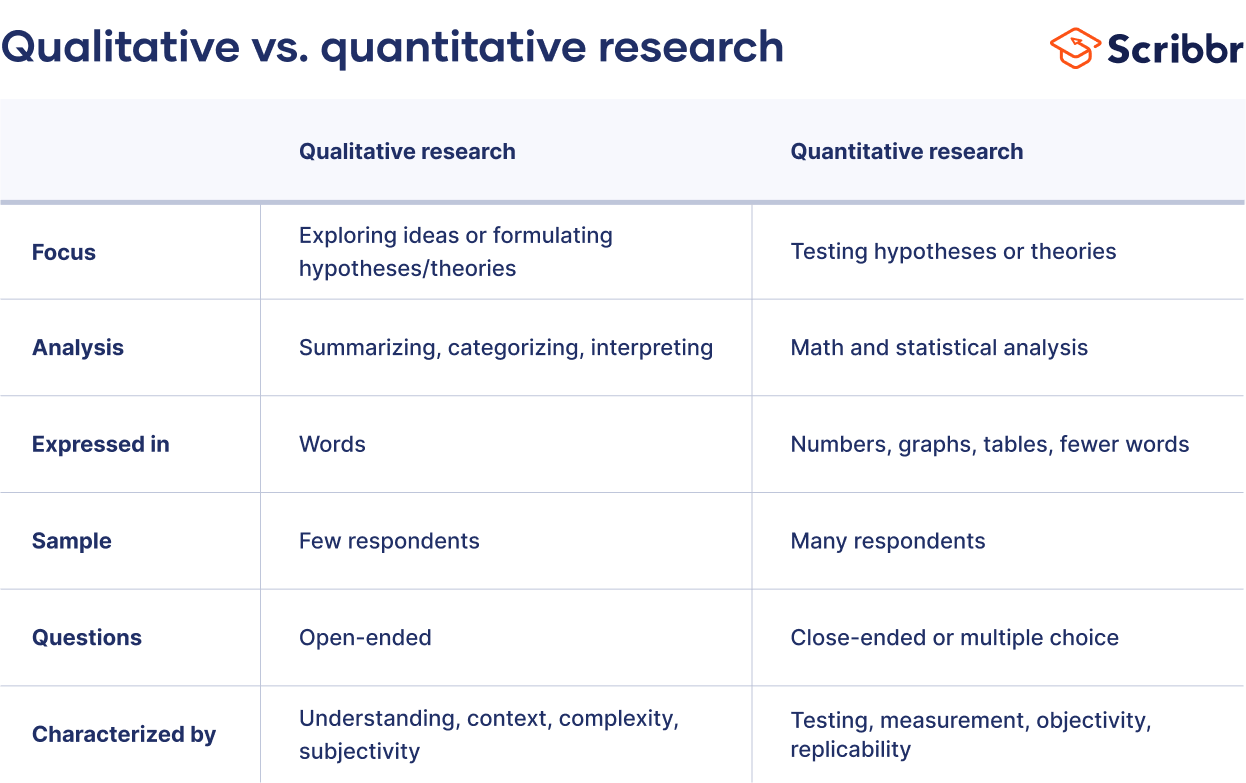

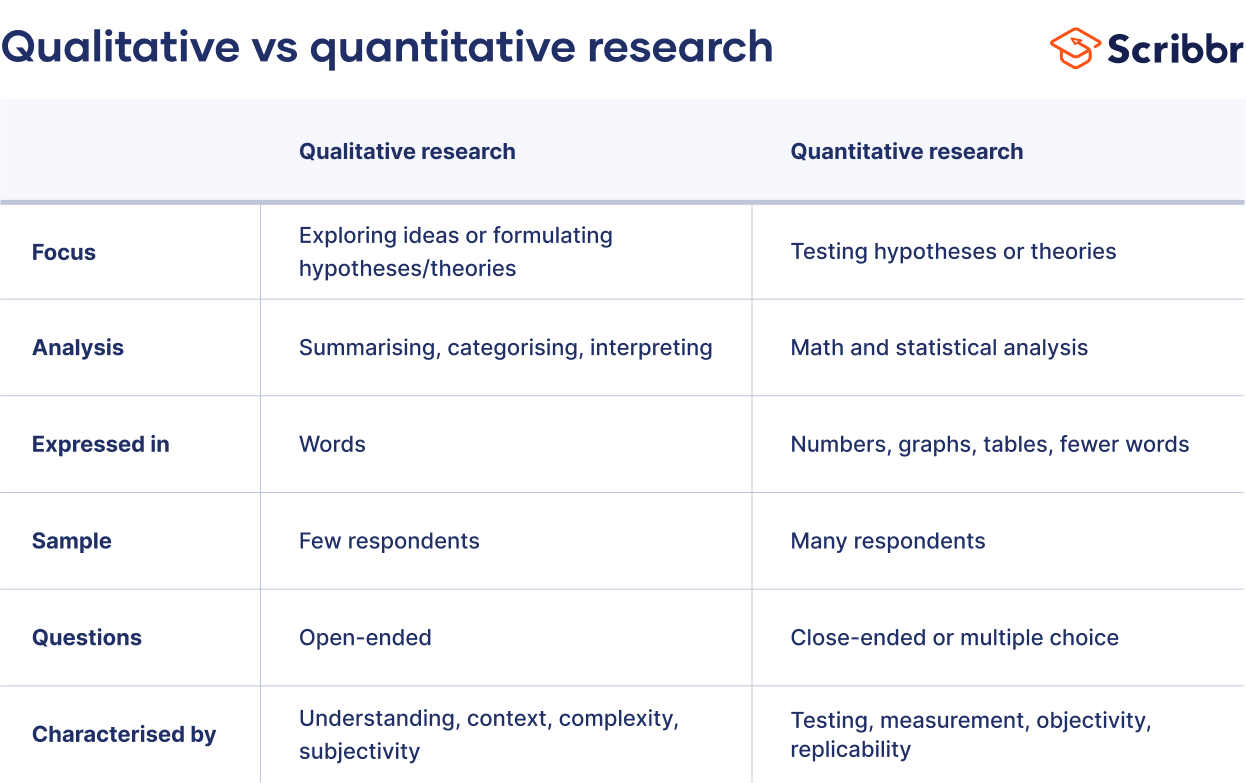

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyze data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observational studies or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g., using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g., with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which different types of variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations : Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups : Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organization for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis )

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs. deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: “on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?”

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: “on average students rated their professors 4.4”.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: “How satisfied are you with your studies?”, “What is the most positive aspect of your study program?” and “What can be done to improve the study program?”

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analyzed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analyzing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple math or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores ( means )

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analyzing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyze than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analyzing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

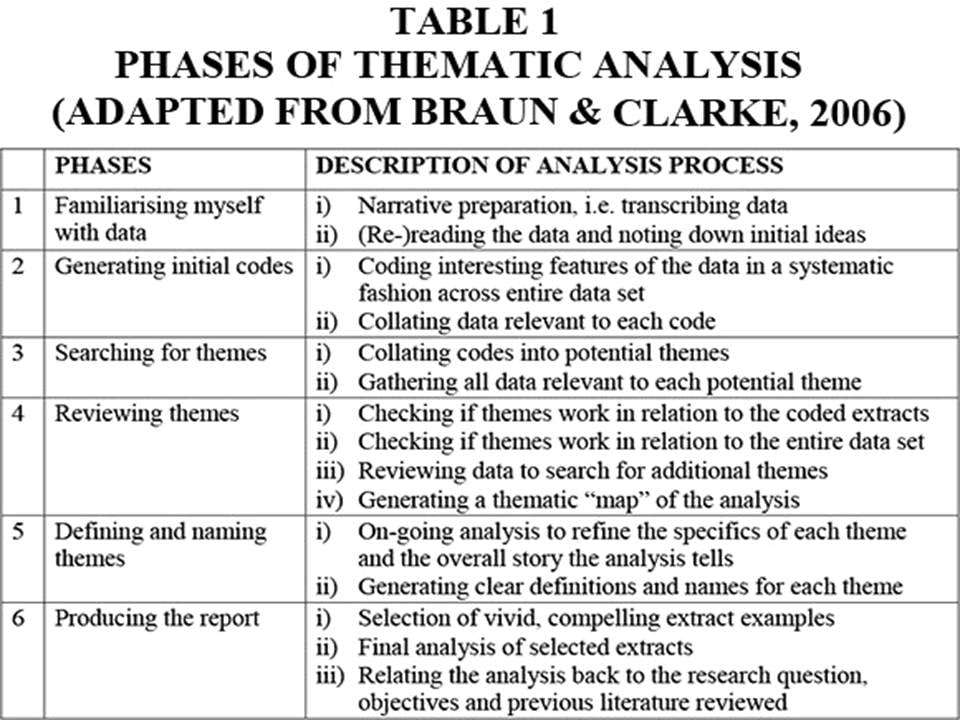

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, June 22). Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, mixed methods research | definition, guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research: Comparing the Methods and Strategies for Education Research

No matter the field of study, all research can be divided into two distinct methodologies: qualitative and quantitative research. Both methodologies offer education researchers important insights.

Education research assesses problems in policy, practices, and curriculum design, and it helps administrators identify solutions. Researchers can conduct small-scale studies to learn more about topics related to instruction or larger-scale ones to gain insight into school systems and investigate how to improve student outcomes.

Education research often relies on the quantitative methodology. Quantitative research in education provides numerical data that can prove or disprove a theory, and administrators can easily share the number-based results with other schools and districts. And while the research may speak to a relatively small sample size, educators and researchers can scale the results from quantifiable data to predict outcomes in larger student populations and groups.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research in Education: Definitions

Although there are many overlaps in the objectives of qualitative and quantitative research in education, researchers must understand the fundamental functions of each methodology in order to design and carry out an impactful research study. In addition, they must understand the differences that set qualitative and quantitative research apart in order to determine which methodology is better suited to specific education research topics.

Generate Hypotheses with Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on thoughts, concepts, or experiences. The data collected often comes in narrative form and concentrates on unearthing insights that can lead to testable hypotheses. Educators use qualitative research in a study’s exploratory stages to uncover patterns or new angles.

Form Strong Conclusions with Quantitative Research

Quantitative research in education and other fields of inquiry is expressed in numbers and measurements. This type of research aims to find data to confirm or test a hypothesis.

Differences in Data Collection Methods

Keeping in mind the main distinction in qualitative vs. quantitative research—gathering descriptive information as opposed to numerical data—it stands to reason that there are different ways to acquire data for each research methodology. While certain approaches do overlap, the way researchers apply these collection techniques depends on their goal.

Interviews, for example, are common in both modes of research. An interview with students that features open-ended questions intended to reveal ideas and beliefs around attendance will provide qualitative data. This data may reveal a problem among students, such as a lack of access to transportation, that schools can help address.

An interview can also include questions posed to receive numerical answers. A case in point: how many days a week do students have trouble getting to school, and of those days, how often is a transportation-related issue the cause? In this example, qualitative and quantitative methodologies can lead to similar conclusions, but the research will differ in intent, design, and form.

Taking a look at behavioral observation, another common method used for both qualitative and quantitative research, qualitative data may consider a variety of factors, such as facial expressions, verbal responses, and body language.

On the other hand, a quantitative approach will create a coding scheme for certain predetermined behaviors and observe these in a quantifiable manner.

Qualitative Research Methods

- Case Studies : Researchers conduct in-depth investigations into an individual, group, event, or community, typically gathering data through observation and interviews.

- Focus Groups : A moderator (or researcher) guides conversation around a specific topic among a group of participants.

- Ethnography : Researchers interact with and observe a specific societal or ethnic group in their real-life environment.

- Interviews : Researchers ask participants questions to learn about their perspectives on a particular subject.

Quantitative Research Methods

- Questionnaires and Surveys : Participants receive a list of questions, either closed-ended or multiple choice, which are directed around a particular topic.

- Experiments : Researchers control and test variables to demonstrate cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations : Researchers look at quantifiable patterns and behavior.

- Structured Interviews : Using a predetermined structure, researchers ask participants a fixed set of questions to acquire numerical data.

Choosing a Research Strategy

When choosing which research strategy to employ for a project or study, a number of considerations apply. One key piece of information to help determine whether to use a qualitative vs. quantitative research method is which phase of development the study is in.

For example, if a project is in its early stages and requires more research to find a testable hypothesis, qualitative research methods might prove most helpful. On the other hand, if the research team has already established a hypothesis or theory, quantitative research methods will provide data that can validate the theory or refine it for further testing.

It’s also important to understand a project’s research goals. For instance, do researchers aim to produce findings that reveal how to best encourage student engagement in math? Or is the goal to determine how many students are passing geometry? These two scenarios require distinct sets of data, which will determine the best methodology to employ.

In some situations, studies will benefit from a mixed-methods approach. Using the goals in the above example, one set of data could find the percentage of students passing geometry, which would be quantitative. The research team could also lead a focus group with the students achieving success to discuss which techniques and teaching practices they find most helpful, which would produce qualitative data.

Learn How to Put Education Research into Action

Those with an interest in learning how to harness research to develop innovative ideas to improve education systems may want to consider pursuing a doctoral degree. American University’s School of Education Online offers a Doctor of Education (EdD) in Education Policy and Leadership that prepares future educators, school administrators, and other education professionals to become leaders who effect positive changes in schools. Courses such as Applied Research Methods I: Enacting Critical Research provides students with the techniques and research skills needed to begin conducting research exploring new ways to enhance education. Learn more about American’ University’s EdD in Education Policy and Leadership .

What’s the Difference Between Educational Equity and Equality?

EdD vs. PhD in Education: Requirements, Career Outlook, and Salary

Top Education Technology Jobs for Doctorate in Education Graduates

American University, EdD in Education Policy and Leadership

Edutopia, “2019 Education Research Highlights”

Formplus, “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data: 15 Key Differences and Similarities”

iMotion, “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research: What Is What?”

Scribbr, “Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research”

Simply Psychology, “What’s the Difference Between Quantitative and Qualitative Research?”

Typeform, “A Simple Guide to Qualitative and Quantitative Research”

Request Information

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative?

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

Qualitative research , on the other hand, collects non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. The focus is on exploring subjective experiences, opinions, and attitudes, often through observation and interviews.

Qualitative research aims to produce rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and to uncover new insights and meanings.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography.

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis.

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded.

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research in Psychology

Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

- Key Differences

Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods.

- How They Relate

In psychology and other social sciences, researchers are faced with an unresolved question: Can we measure concepts like love or racism the same way we can measure temperature or the weight of a star? Social phenomena—things that happen because of and through human behavior—are especially difficult to grasp with typical scientific models.

At a Glance

Psychologists rely on quantitative and quantitative research to better understand human thought and behavior.

- Qualitative research involves collecting and evaluating non-numerical data in order to understand concepts or subjective opinions.

- Quantitative research involves collecting and evaluating numerical data.

This article discusses what qualitative and quantitative research are, how they are different, and how they are used in psychology research.

Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research

In order to understand qualitative and quantitative psychology research, it can be helpful to look at the methods that are used and when each type is most appropriate.

Psychologists rely on a few methods to measure behavior, attitudes, and feelings. These include:

- Self-reports , like surveys or questionnaires

- Observation (often used in experiments or fieldwork)

- Implicit attitude tests that measure timing in responding to prompts

Most of these are quantitative methods. The result is a number that can be used to assess differences between groups.

However, most of these methods are static, inflexible (you can't change a question because a participant doesn't understand it), and provide a "what" answer rather than a "why" answer.

Sometimes, researchers are more interested in the "why" and the "how." That's where qualitative methods come in.

Qualitative research is about speaking to people directly and hearing their words. It is grounded in the philosophy that the social world is ultimately unmeasurable, that no measure is truly ever "objective," and that how humans make meaning is just as important as how much they score on a standardized test.

Used to develop theories

Takes a broad, complex approach

Answers "why" and "how" questions

Explores patterns and themes

Used to test theories

Takes a narrow, specific approach

Answers "what" questions

Explores statistical relationships

Quantitative methods have existed ever since people have been able to count things. But it is only with the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (which maintains that factual knowledge obtained by observation is trustworthy) that it became a "scientific method."

The scientific method follows this general process. A researcher must:

- Generate a theory or hypothesis (i.e., predict what might happen in an experiment) and determine the variables needed to answer their question

- Develop instruments to measure the phenomenon (such as a survey, a thermometer, etc.)

- Develop experiments to manipulate the variables

- Collect empirical (measured) data

- Analyze data

Quantitative methods are about measuring phenomena, not explaining them.

Quantitative research compares two groups of people. There are all sorts of variables you could measure, and many kinds of experiments to run using quantitative methods.

These comparisons are generally explained using graphs, pie charts, and other visual representations that give the researcher a sense of how the various data points relate to one another.

Basic Assumptions

Quantitative methods assume:

- That the world is measurable

- That humans can observe objectively

- That we can know things for certain about the world from observation

In some fields, these assumptions hold true. Whether you measure the size of the sun 2000 years ago or now, it will always be the same. But when it comes to human behavior, it is not so simple.

As decades of cultural and social research have shown, people behave differently (and even think differently) based on historical context, cultural context, social context, and even identity-based contexts like gender , social class, or sexual orientation .

Therefore, quantitative methods applied to human behavior (as used in psychology and some areas of sociology) should always be rooted in their particular context. In other words: there are no, or very few, human universals.

Statistical information is the primary form of quantitative data used in human and social quantitative research. Statistics provide lots of information about tendencies across large groups of people, but they can never describe every case or every experience. In other words, there are always outliers.

Correlation and Causation

A basic principle of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Researchers can only claim a cause-and-effect relationship under certain conditions:

- The study was a true experiment.

- The independent variable can be manipulated (for example, researchers cannot manipulate gender, but they can change the primer a study subject sees, such as a picture of nature or of a building).

- The dependent variable can be measured through a ratio or a scale.

So when you read a report that "gender was linked to" something (like a behavior or an attitude), remember that gender is NOT a cause of the behavior or attitude. There is an apparent relationship, but the true cause of the difference is hidden.

Pitfalls of Quantitative Research

Quantitative methods are one way to approach the measurement and understanding of human and social phenomena. But what's missing from this picture?

As noted above, statistics do not tell us about personal, individual experiences and meanings. While surveys can give a general idea, respondents have to choose between only a few responses. This can make it difficult to understand the subtleties of different experiences.

Quantitative methods can be helpful when making objective comparisons between groups or when looking for relationships between variables. They can be analyzed statistically, which can be helpful when looking for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative data are not made out of numbers but rather of descriptions, metaphors, symbols, quotes, analysis, concepts, and characteristics. This approach uses interviews, written texts, art, photos, and other materials to make sense of human experiences and to understand what these experiences mean to people.

While quantitative methods ask "what" and "how much," qualitative methods ask "why" and "how."

Qualitative methods are about describing and analyzing phenomena from a human perspective. There are many different philosophical views on qualitative methods, but in general, they agree that some questions are too complex or impossible to answer with standardized instruments.

These methods also accept that it is impossible to be completely objective in observing phenomena. Researchers have their own thoughts, attitudes, experiences, and beliefs, and these always color how people interpret results.

Qualitative Approaches

There are many different approaches to qualitative research, with their own philosophical bases. Different approaches are best for different kinds of projects. For example:

- Case studies and narrative studies are best for single individuals. These involve studying every aspect of a person's life in great depth.

- Phenomenology aims to explain experiences. This type of work aims to describe and explore different events as they are consciously and subjectively experienced.

- Grounded theory develops models and describes processes. This approach allows researchers to construct a theory based on data that is collected, analyzed, and compared to reach new discoveries.

- Ethnography describes cultural groups. In this approach, researchers immerse themselves in a community or group in order to observe behavior.

Qualitative researchers must be aware of several different methods and know each thoroughly enough to produce valuable research.

Some researchers specialize in a single method, but others specialize in a topic or content area and use many different methods to explore the topic, providing different information and a variety of points of view.

There is not a single model or method that can be used for every qualitative project. Depending on the research question, the people participating, and the kind of information they want to produce, researchers will choose the appropriate approach.

Interpretation

Qualitative research does not look into causal relationships between variables, but rather into themes, values, interpretations, and meanings. As a rule, then, qualitative research is not generalizable (cannot be applied to people outside the research participants).

The insights gained from qualitative research can extend to other groups with proper attention to specific historical and social contexts.

Relationship Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

It might sound like quantitative and qualitative research do not play well together. They have different philosophies, different data, and different outputs. However, this could not be further from the truth.

These two general methods complement each other. By using both, researchers can gain a fuller, more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

For example, a psychologist wanting to develop a new survey instrument about sexuality might and ask a few dozen people questions about their sexual experiences (this is qualitative research). This gives the researcher some information to begin developing questions for their survey (which is a quantitative method).

After the survey, the same or other researchers might want to dig deeper into issues brought up by its data. Follow-up questions like "how does it feel when...?" or "what does this mean to you?" or "how did you experience this?" can only be answered by qualitative research.

By using both quantitative and qualitative data, researchers have a more holistic, well-rounded understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon.

Qualitative and quantitative methods both play an important role in psychology. Where quantitative methods can help answer questions about what is happening in a group and to what degree, qualitative methods can dig deeper into the reasons behind why it is happening. By using both strategies, psychology researchers can learn more about human thought and behavior.

Gough B, Madill A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect . Psychol Methods . 2012;17(3):374-384. doi:10.1037/a0029313

Pearce T. “Science organized”: Positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865–1875 . J Hist Ideas . 2015;76(3):441-465.

Adams G. Context in person, person in context: A cultural psychology approach to social-personality psychology . In: Deaux K, Snyder M, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology . Oxford University Press; 2012:182-208.

Brady HE. Causation and explanation in social science . In: Goodin RE, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press; 2011. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0049

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers . SAGE Open Med . 2019;7:2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80 . Medical Teacher . 2013;35(8):e1365-e1379. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Salkind NJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Research Design . Sage Publishing.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw Hill Education.

By Anabelle Bernard Fournier Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2023 3:14 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Published on 4 April 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 8 May 2023.

When collecting and analysing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions. Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs quantitative research, how to analyse qualitative and quantitative data, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyse data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observations or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g. using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g. with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations: Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups: Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organisation for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis)

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: ‘on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?’

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: ‘on average students rated their professors 4.4’.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: ‘How satisfied are you with your studies?’, ‘What is the most positive aspect of your study program?’ and ‘What can be done to improve the study program?’

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analysed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analysing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple maths or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analysing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyse than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analysing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, May 08). Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/quantitative-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

- How it works

Qualitative Vs Quantitative Research – A Comprehensive Guide

Published by Carmen Troy at August 13th, 2021 , Revised On September 20, 2023

What is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is associated with numerical data or data that can be measured. It is used to study a large group of population. The information is gathered by performing statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques.

Quantitative research isn’t simply based on statistical analysis or quantitative techniques but rather uses a certain approach to theory to address research hypotheses or questions, establish an appropriate research methodology, and draw findings & conclusions .

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Some most commonly employed quantitative research strategies include data-driven dissertations, theory-driven studies, and reflection-driven research. Regardless of the chosen approach, there are some common quantitative research features as listed below.

- Quantitative research tests or builds on other researchers’ existing theories whilst taking a reflective or extensive route.

- Quantitative research aims to test the research hypothesis or answer established research questions.

- It is primarily justified by positivist or post-positivist research paradigms.

- The research design can be relationship-based, quasi-experimental, experimental, or descriptive.

- It draws on a small sample to make generalisations to a wider population using probability sampling techniques.

- Quantitative data is gathered according to the established research questions using research vehicles such as structured observation, structured interviews, surveys, questionnaires, and laboratory results.

- The researcher uses statistical analysis tools and techniques to measure variables and gather inferential or descriptive data. In some cases, your tutor or dissertation committee members might find it easier to verify your study results with numbers and statistical analysis.

- The study results’ accuracy is based on external and internal validity and authenticity of the data used.

- Quantitative research answers research questions or tests the hypothesis using charts, graphs, tables, data, and statements.

- It underpins research questions or hypotheses and findings to make conclusions.

- The researcher can provide recommendations for future research and expand or test existing theories.

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is a type of scientific research where a researcher collects evidence to seek answers to a question . It is associated with studying human behavior from an informative perspective. It aims at obtaining in-depth details of the problem.

As the term suggests, qualitative research is based on qualitative research methods, including participants’ observations, focus groups, and unstructured interviews.

Qualitative research is very different in nature when compared to quantitative research. It takes an established path towards the research process , how research questions are set up, how existing theories are built upon, what research methods are employed, and how the findings are unveiled to the readers.

You may adopt conventional methods, including phenomenological research, narrative-based research, grounded theory research, ethnographies, case studies, and auto-ethnographies.

Does your Research Methodology Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of Research Methodology strong.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Again, regardless of the chosen approach to qualitative research, your dissertation will have unique key features as listed below.

- The research questions that you aim to answer will expand or even change as the dissertation writing process continues . This aspect of the research is typically known as an emergent design where the research objectives evolve with time.

- Qualitative research may use existing theories to cultivate new theoretical understandings or fall back on existing theories to support the research process. However, the original goal of testing a certain theoretical understanding remains the same.

- It can be based on various research models, such as critical theory, constructivism, and interpretivism.

- The chosen research design largely influences the analysis and discussion of results and the choices you make . Research design depends on the adopted research path: phenomenological research, narrative-based research, grounded theory-based research, ethnography, case study-based research, or auto-ethnography.

- Qualitative research answers research questions with theoretical sampling, where data gathered from the organisation or people are studied.

- It involves various research methods to gather qualitative data from participants belonging to the field of study. As indicated previously, some of the most notable qualitative research methods include participant observation, focus groups, and unstructured interviews.

- It incorporates an inductive process where the researcher analyses and understands the data through his own eyes and judgments to identify concepts and themes that comprehensively depict the researched material.

- The key quality characteristics of qualitative research are transferability, conformity, confirmability, and reliability.

- Results and discussions are largely based on narratives, case study and personal experiences, which help detect inconsistencies, observations, processes, and ideas.

- Qualitative research discusses theoretical concepts obtained from the results whilst taking research questions and/or hypotheses to draw general conclusions .

Confused between qualitative and quantitative methods of data analysis? No idea what discourse and content analysis are?

We hear you.

- Whether you want a full dissertation written or need help forming a dissertation proposal, we can help you with both.

- Get different dissertation services at ResearchProspect and score amazing grades!

When to Use Qualitative and Quantitative Research Model?

- The research title, research questions, hypothesis , objectives, and study area generally determine the dissertation’s best research method.

- If the primary aim of your research is to test a hypothesis, validate an existing theory or perhaps measure some variables, then the quantitative research model will be the more appropriate choice because it might be easier for you to convince your supervisor or members of the dissertation committee with the use of statistics and numbers.

- On the other hand, oftentimes, statistics and a collection of numbers are not the answer, especially where there is a need to understand meanings, experiences, and beliefs.

- If your research questions or hypothesis can be better addressed through people’s observations and experiences, you should consider qualitative data.

- If you select an inappropriate research method, you will not prove your findings’ accuracy, and your dissertation will be pretty much meaningless. To prove that your research is authentic and reliable, choose a research method that best suits your study’s requirements.

- In the sections that follow, we explain the most commonly employed research methods for the dissertation, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methods.

Now that you know the unique differences between quantitative and qualitative research methods, you may want to learn a bit about primary and secondary research methods.

Here is an article that will help you distinguish between primary and secondary research and decide whether you need to use quantitative and/or qualitative methods of primary research in your dissertation.

Alternatively, you can base your dissertation on secondary research, which is descriptive and explanatory.

Limitations of Quantitative and Qualitative Research

What is quantitative research, what is qualitative research.

Qualitative research is a type of scientific research where a researcher collects evidence to seek answers to a question . It is associated with studying human behavior from an informative perspective. It aims at obtaining in-depth details of the problem.

Qualitative or quantitative, which research type should I use?

The research title, research questions, hypothesis , objectives, and study area generally determine the dissertation’s best research method.

You May Also Like

A hypothesis is a research question that has to be proved correct or incorrect through hypothesis testing – a scientific approach to test a hypothesis.

In historical research, a researcher collects and analyse the data, and explain the events that occurred in the past to test the truthfulness of observations.

Descriptive research is carried out to describe current issues, programs, and provides information about the issue through surveys and various fact-finding methods.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

What’s the Difference: Qualitative vs Quantitative Research?

Discover the differences between qualitative vs quantitative research. Learn how to choose the right methodology for your research project.

There are several methodologies for conducting research, with qualitative and quantitative research being two of the most prominent. Qualitative research focuses on understanding an individual’s experiences and points of view through observation and interviews, whereas quantitative research analyses and draws conclusions based on numerical data. Both strategies have benefits as well as drawbacks, and selecting the appropriate methodology can have a considerable influence on the outcome of a study.

In this article, we will look at the differences between qualitative vs quantitative research, their benefits and drawbacks, and how to analyze based on each method. By the end of this article, you will have a better grasp of these two research methods and will be better prepared to select the best one for your research.

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is a research method that focuses on understanding individuals’ experiences, perspectives, and behaviors in their natural environment. This method is frequently used to investigate complex phenomena that are difficult to quantify, such as beliefs, attitudes, and feelings. Data for qualitative research is often gathered through methods such as observation, interviews, and focus groups. The information gathered is frequently non-numerical and might comprise text, audio, and visual records.

One of the distinctive features of qualitative research is the emphasis on context and the subjective interpretation of data. Rather than attempting to generalize the findings to a broader population, qualitative researchers strive to grasp the meaning and relevance of the data acquired by evaluating it in its context.

This strategy helps researchers to obtain a better understanding of the experiences and points of view of the individuals being examined, as well as find patterns and themes that may not have been obvious using other research methods.

What is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is a research method that focuses on the systematic collecting and analysis of numerical data. This strategy is frequently used to investigate correlations between variables and to make predictions or generalizations about a wider population based on a sample. Quantitative research often entails gathering data using methods such as surveys, experiments, and structured observations, and then evaluating the data using statistical techniques.

One of the distinctive features of quantitative research is its emphasis on impartiality and the use of standardized measurements. Quantitative researchers use rigorous methods for gathering and analyzing information to reduce the effect of personal bias and subjectivity.

This method enables researchers to test hypotheses, identify cause-and-effect correlations, and draw statistical inferences about a wider population.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

When deciding on the methodology to use, researchers should examine the advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research, as follows:

- Data richness and depth: Qualitative research enables researchers to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ experiences, attitudes, and points of view, which can offer a more complete picture of the phenomena under investigation.

- Flexibility: Qualitative research is adaptive and flexible, allowing researchers to change their method in response to new or unexpected discoveries.

- Understanding participants: Since qualitative research frequently involves direct involvement with individuals, researchers can get a better grasp of their personal experiences and points of view.

- Contextualization: Qualitative research stresses the relevance of context and subjective data interpretation, which can give insights into how individuals make meaning of their experiences in their specific settings.

- Hypothesis generation: By recognizing patterns and themes in the data, qualitative research may be utilized to develop hypotheses for additional research.

Disadvantages

- Limited generalizability: Since qualitative research occasionally relies on small sample size, it may not be representative of the wider population, its generalizability is limited.

- Subjectivity: Qualitative research entails subjective data interpretation, which may be impacted by the researcher’s bias or personal perspective.

- Time-consuming: As qualitative research includes in-depth data collecting and processing, it may be time-consuming.

- Difficulties in analysis: Qualitative data can be complicated and difficult to analyze, especially when non-textual material such as photos or audio recordings are included.

- Data saturation: Qualitative research might reach a point where new information does not yield significant insights, limiting the relevance of further data collection.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Quantitative Research

Quantitative research, like qualitative research, has advantages and disadvantages that researchers should consider when selecting this method for their study.

- Generalizability: Since quantitative research is frequently based on a larger sample size, it can yield statistically valid findings that can be generalized to a broader population.

- Objectivity: Quantitative research places an emphasis on objectivity and standardized measurements, which reduces the impact of personal bias and subjectivity.

- Replicability: Quantitative research provides an established method and standardized measurements, allowing other researchers to replicate the research.

- Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis is possible in quantitative research, which may assist researchers evaluate hypotheses and discover cause-and-effect connections.

- Effective data analysis: Quantitative research frequently involves numerical data, which may be quickly examined using statistical tools.

Disadvantages

- Lack of depth: As quantitative research frequently depends on standardized measurements, it may overlook the intricacies of participants’ experiences and points of view.

- Limited comprehension: Quantitative research frequently focuses on specific aspects of the phenomenon being examined, it may not give an in-depth understanding of the entire phenomenon being studied.

- Inflexibility: Since quantitative research relies on a set methodology and established measurements, it is frequently inflexible.

- Limited context: Quantitative research may fail to recognize the significance of context and may neglect the impact of subjective data interpretation.

- Measurement error: Quantitative research is based on numerical data, which might be prone to measurement errors or inaccuracies.

Data Collection Methods: Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

The collection of data methods differs in different ways between qualitative vs quantitative research.

Qualitative research often employs data-collecting methods such as interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. Using these methods, researchers may acquire extensive, detailed data about participants’ experiences, perspectives, and points of view.

Interviews and focus groups, for example, allow researchers to interact directly with participants and delve deeper into their personal experiences and points of view. Researchers can use observation to study participants’ behavior in their natural environment and capture their experiences in real-time.

They might investigate written or visual materials such as diaries, letters, or photos to get insights into participants’ experiences and points of view through document analysis.

Quantitative research often uses methods for collecting data such as surveys, experiments, and structured observations. These methods enable researchers to acquire numerical data that can then be examined statistically.

Surveys entail asking individuals to answer a series of standardized questions, usually in writing or online. Experiments entail tinkering with one or more variables in order to test hypotheses and quantify the effect on a dependent variable. Structured observations entail gathering data in a methodical manner, frequently utilizing pre-determined categories or checklists.

Overall, data-collecting methods are employed in both qualitative and quantitative research, although the methods utilized change based on the research’s methodology and the type of data being gathered. Quantitative research focuses on numerical data that can be evaluated using statistical tools, whereas qualitative research emphasizes rich, detailed data that can give insights into participants’ experiences and points of view.

How to Analyze Qualitative vs Quantitative Data

Due to the nature of the data, analyzing qualitative and quantitative data requires different methodologies.

The identification of patterns, themes, and categories in collected data is the primary objective of qualitative data analysis . This method frequently includes the following steps:

- Transcribing or turning recorded data into text is usually the first stage in assessing qualitative data.