Brand Consultation & Market Analysis

- Brand Audit & Strategy

- Competitor Analysis

- Consumer Interviews

- Google Analytics Review

- Persona Development

- SEO Audit & Strategy

- SEO Keyword Research

- Site Mapping & Content Architecture

- Technical Strategy & Roadmapping

Creative Design & Branding

- Copywriting & Storytelling

- Event & Exhibition

- Inbound Marketing

- Logo & Brand Development

- Mobile App Design & Development

- Presentation Design

- Print Design

- Website Design & Development

Custom Web & App Development

- API Development

- Augmented Reality App Development

- Front-End Design & Development

- Virtual Reality App Development

- Web App Development

- WordPress Theme Customization

- WordPress Theme Development

Immersive Reality & New Technologies

- 3D Environment Creation

- Advanced 3D Modeling

- Immersive Story Telling

- Mixed Reality App Development

- Photogrammetry

- Prototyping

- Quantified Biometrics

Video Production & Animation

- Drone Video

- Film Production

- Mixed Reality Video

- Motion Graphics

- Post Production & Editing

- Script Writing & Story Telling

- Storyboards & Shotlists

- Voiceover & Audio Sourcing

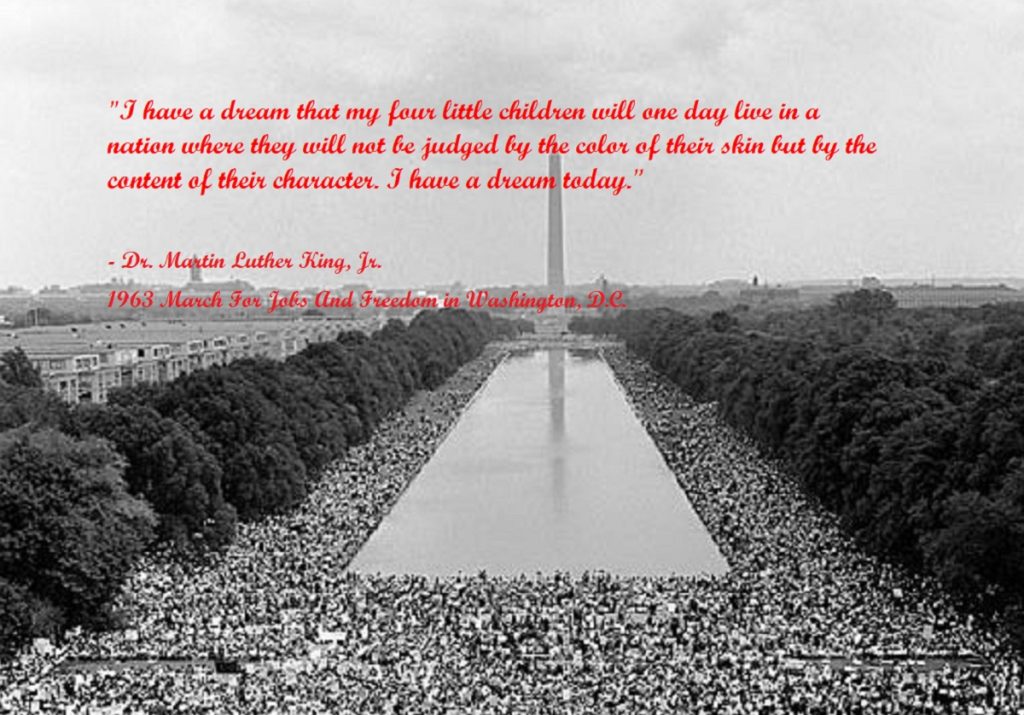

25 Examples of Rhetorical Strategies in Famous Speeches

I’m not trying to be cheesy! An emotional response is a meaningful response, and that reaction stays with you long after the presentation is over. Whenever you think of that speaker or of that topic, your brain will bring back those feelings for you- whether they be of motivation, inspiration, sadness, empathy, or otherwise.

Rhetorical strategies use language to convey special meaning and/or to persuade someone. Basically, these strategies can be used to intentionally invoke feelings in others.

If your first reaction to all this is “Huh?” that’s okay- so was mine. Here’s how I understand it now: rhetorical strategies = emotional connection = memorability.

If you’ve ever considered becoming a master presenter (no judgement if you have), you need these tools in your repertoire ASAP. They’re just so effective!

Don’t believe me? All the cool kids are using (or used) them – I’m talking about thought leader Simon Sinek , technology guru Steve Jobs, past American president Barack Obama, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., and even good old William Shakespeare.

Unless you’re above any of these greatly respected people, I’m betting that you could benefit from a little rhetorical strategy in your next speech!

25 rhetorical strategies from the best minds

We’ve compiled 25 rhetorical strategies from the most memorable presentations on the planet so that your next presentation is undeniably memorable. Ready to begin?

1. Alliteration:

Two or more words in a row that start with the same sound.

“They are part of the finest fighting force that the world has ever known. They have served tour after tour of duty in distant, different, and difficult places.” – Barack Obama

2. Allusion:

A statement that hints at something instead of being direct about it.

“You must borrow me Gargantua’s mouth first. ‘Tis a word too great for any mouth of this age’s size” – Shakespeare

3. Anadiplosis:

Repeating the last word (or words) of a sentence at the beginning of the next sentence.

“Tonight, we are a country awakened to danger and called to defend freedom. Our grief has turned to anger, and anger to resolution.” – George W. Bush

4. Analogy:

A literal comparison of two things.

“A good speech should be like a woman’s skirt: long enough to cover the subject and short enough to create interest.” – Winston Churchill

5. Anaphora:

Using the same word (or words) to begin 2 or more sentences (or paragraphs) that follow each other.

“I trust Hillary to lead this country because I’ve seen her lifelong devotion to our nation’s children – not just her own daughter, who she has raised to perfection but every child who needs a champion: Kids who take the long way to school to avoid the gangs. Kids who wonder how they’ll ever afford college. Kids whose parents don’t speak a word of English but dream of a better life. Kids who look to us to determine who and what they can be.” – Michelle Obama

6. Anastrophe:

A reversal of the typical ordering of a sentence.

“This much we pledge, and more” – JF Kennedy

7. Antistrophe:

Repeating one (or more) words at the end of a sentence.

“It was a creed written into the founding documents that declared the destiny of a nation: Yes, we can. It was whispered by slaves and abolitionists as they blazed a trail towards freedom through the darkest of nights: Yes, we can. It was sung by immigrants as they struck out from distant shores and pioneers who pushed westward against an unforgiving wilderness: Yes, we can” – Barack Obama

8. Antithesis:

A contrast of thoughts.

“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” – Neil Armstrong

9. Asyndeton:

Leaving out conjunction words (as or and) from a sentence.

“…and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” – Abraham Lincoln

10. Assonance:

Repeating a vowel sound in a sentence.

“I feel the need, the need for speed” – Tom Cruise (from the movie Top Gun)

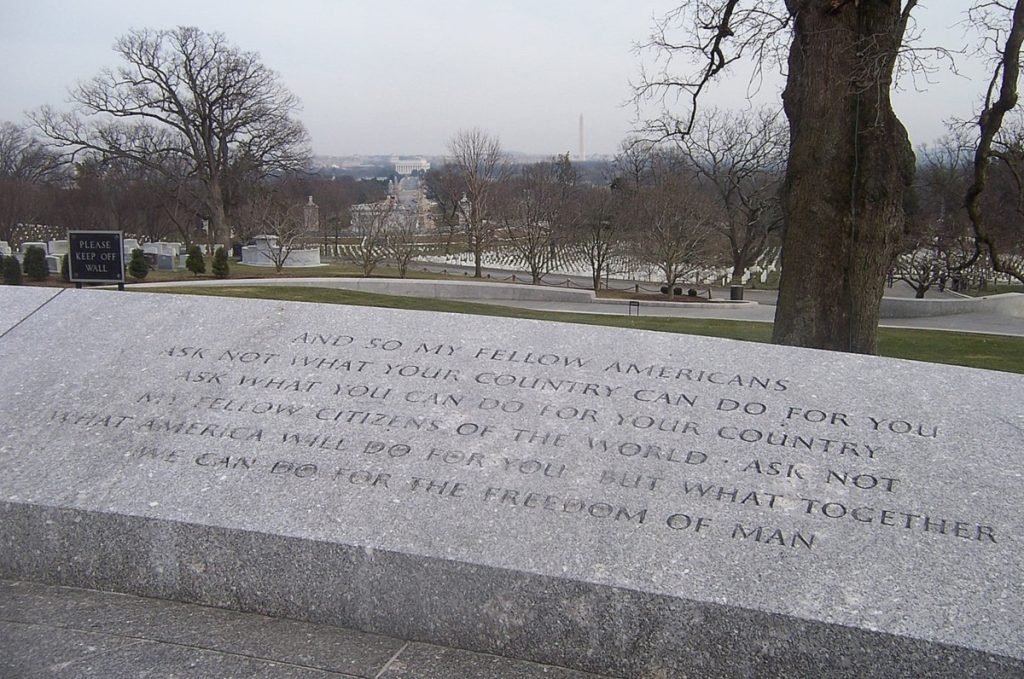

11. Chiasmus:

The reversal of the latter of two parallel sentences.

“And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country” – John F. Kennedy

12. Diacope/Tmesis:

Inserting a word (or more) between the components of a compound word.

“Free at last, free at last; thank God almighty, free at last!” – Martin Luther King

13. Epistrophe:

Another name for antistrophe (see above).

“…and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth” – Abraham Lincoln

14. Expletive:

Using a word or phrase only to fill out a sentence for grammar, rhythm or balance.

“… we shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving …” – Winston Churchill

15. Germinatio:

The repetition of a word within the sentence.

“That’s 58 songs every second of every minute of every hour of every day.” – Steve Jobs

16. Hyperbole:

Exaggerating a description for emphasis.

“Best version of Google Maps on the planet, widgets, and all with Edge and Wi-Fi networking.” – Steve Jobs

17. Hypophora:

Posing a question that you will answer yourself.

“When the enemy struck on that June day of 1950, what did America do? It did what it always has done in all its times of peril. It appealed to the heroism of its youth” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

18. Litotes:

An understatement that expresses an affirmative by negating its opposite.

“I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

19. Meiosis:

A massive understatement.

“The situation has developed, not necessarily to our advantage” – Emperor Hirohito, announcing to the Japanese people that atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

20. Metaphor:

Comparing two unlike objects to provide a clearer description.

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” – William Shakespeare

21. Parallelism:

using a sequence of identical constructions in writing

“Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I may remember. Involve me and I will learn.” – Benjamin Franklin

22. Scesis Onomaton:

Repeating two (or more) different words with identical or similar meaning within the same sentence.

“That is heart-breaking, it is wrong, and no one should be treated that way in the United States of America” – Barack Obama

23. Simile:

Comparing two unlike things using the words “like” or “as” with an example.

“We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

24. Symploce:

Repeating one (or more) words at the beginning and end of successive sentences.

“In the struggle for peace and justice, we cannot walk alone. In the struggle for opportunity and equality, we cannot walk alone. In the struggle to heal this nation and repair this world, we cannot walk alone” – Barack Obama

25. Tricolon:

A sentence with three clearly defined parts of equal length

Rhetorical strategies improve audience engagement

If you got a little lost amidst the English jargon, here are the 2 main takeaways you need to know:

- Repetition emphasizes meaning Repetition is perhaps the most common rhetorical strategy. Whether it be the repetition of a word, a phrase, or a specific sound, it is incredibly effective. Use this strategy to build meaning behind the essential points you need to get across.

- Comparisons facilitate understanding Comparisons are also an extremely popular strategy, likely because they make the subject matter more relatable. If your audience can identify with what you’re saying, that creates an opportunity for you to cultivate a connection with them.

In sum, the best designed presentations , a slick new outfit, or a commanding voice may impress an audience initially, and can be important to gain their attention, but they lack true substance for any long-term retention. Rhetorical strategies are the single greatest tool for memorability. If you recognized even one of these examples, you just proved that rhetoric strategies are memorable. Why not start using them to your advantage?

Incorporating rhetorical strategies is kind of like learning how to ride a bike – you’re going to think you look unsure the first few times you try and you’re probably going to walk away with some scrapes and bruises. But, once you gain confidence, you’ll be able to ride circles around everyone else.

See what I did there? Here’s to being memorable!

Note: All definitions have been adapted from Your Dictionary .

Looking for more presentation insights?

Check out our Top 30 Most Popular Presentations of All Time , 16 Strategies Used by Pitch Deck Designers , 10 Things to Never Do When Presenting , or read our Top 10 Presentation Tips .

Looking for some creative help for your next presentation? Our team of talented ninja designers would love to assist!

Previous Post The Ultimate Guide to VR Videos

Next post 52 creative infographics that will inspire, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Brand Consultation & Market Analysis

- Creative Design & Branding

- Custom Web & App Development

- Immersive Reality & New Technologies

- Video Production & Animation

- View All Services

- 1-888-77-NINJA

You can see how this popup was set up in our step-by-step guide: https://wppopupmaker.com/guides/auto-opening-announcement-popups/

Need a Ninja?

Tom Werner / Getty Images

By Colin Baker Leaders Staff

Colin Baker

Leadership and Business Writer

Colin Baker is a business writer for Leaders Media. He has a background in as a television journalism, working as...

Learn about our editorial policy

Updated Apr 19, 2022

8 Rhetorical Strategies to Persuade Your Audience

What are rhetorical strategies, common rhetorical choices, avoid logical fallacies, the power of persuasion is yours.

If you’ve ever had a conversation with someone who thinks the opposite of you, then you know how challenging it is to persuade them. Even when addressing a receptive audience, having people join your side takes skill and precision. Persuasion is far from an exact science, but influential leaders know how to weave different rhetorical strategies together to create a compelling argument. Their rhetorical choices form the backbone of their persuasion technique, which you can emulate to perfect your own skills. Whether preparing a new speech or writing an article, you can use these strategies to move people closer to your point of view.

In this article, find out what rhetorical strategies are and some of the most common ones you can utilize right away.

Rhetorical strategies (AKA persuasive rhetorical devices or persuasive strategies) consist of the word choice you use to persuade, initiate a response, or show meaning. While some may associate these strategies with formal situations, many people use them in casual conversation without realizing it. Any time you seek to persuade someone, you will likely use a rhetorical strategy of some type. Keep this in mind as you look at the following list.

1. Similes and Metaphors

One common rhetorical strategy is to use similes and metaphors throughout your attempt to persuade. Both of these rhetorical resources aim to compare two different items and indicate how they are alike. This makes the comparison much clearer and imparts added meaning to what you’re trying to say. People use similes and metaphors all the time, even in everyday conversation. The main difference between the two is that similes use the words “like” or “as” within the comparison, while metaphors simply say the two things are equal.

Examples of Similes

- You’re as straight as an arrow.

- The two brothers are like peas in a pod.

- The teacher has been busy as a bee.

- The pain felt like a knife stabbing him in the side.

- Her hands were as cold as ice.

Examples of Metaphors

- They considered him the black sheep of the family.

- America is a melting pot of different cultures.

- All the world’s a stage.

- She went to the conference with an army of students.

2. Euphemisms

Sometimes when making a persuasive argument, you need to reference something unpleasant or even disturbing. Doing so may cause your intended audience to feel uncomfortable or leave them with lingering questions about what you mean. They may decide to tune you out when this happens instead of listening to what makes them uneasy. To avoid this problem, you can choose to use a euphemism instead. This rhetorical device replaces the unpleasant word or phrase with something more acceptable and easier to hear (or read if you’re writing an argument). Euphemisms can sometimes go too far, especially if misused, but speakers and writers tend to use them to sidestep a topic to focus on their core message.

Examples of Euphemisms

- “Collateral damage” instead of “civilian deaths.”

- “Mature” instead of “old.”

- “Passed away” instead of “died.”

- “Between jobs” instead of “unemployed.”

- “Comfort food” instead of “junk food.”

3. Chiasmus

You want your persuasive argument to stick with people long past the point when you stop talking or writing. One of the best ways to do that is by using chiasmus . This rhetorical strategy can elicit an emotional response by simply changing the order of words to mirror each other. When you do this, you can generate catchy phrases. One of the most often cited resources of rhetoric comes from the inaugural address of John F. Kennedy, who told the people of the United States, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Notice how the sentence has two parts to it, with the second half mirroring the first half. It’s the sort of phrase that remains with you long after you first hear it.

Examples of Chiasmus

- “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight that counts, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.” —Dwight D. Eisenhower

- “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” —Knute Rockne

- “You must eat to live, not live to eat.” —Socrates

4. Cause and Effect

Another key component in making or writing a persuasive argument is to show the relationship between cause and effect. The point you want to make will help you determine what receives the most focus. For example, if you’re going to discuss why employees suffer from work burnout (the effect), you’ll want to look at the causes. When you look at causes, that shows an interest in what will happen. On the flip side, looking at effects looks at what could happen in the future. Analysis of cause and effect is a useful way to craft a historical narrative, such as what policies led to a business like Apple succeeding. It’s also an effective way to provide solutions as you show the relationship between causes and what can change to prevent undesirable effects.

Logos is the use of logic or reason to argue a point. The two types of rhetorical appeals used in this way include deductive and inductive reasoning. Logos rhetoric with inductive reasoning looks at specific facts and historical resources, then uses them to create a larger generalization. Here’s an example of inductive reasoning: the practice of prioritizing tasks helped this worker become more productive, so all workers would benefit from prioritizing their tasks. Logos rhetoric with deductive reasoning, on the other hand, starts with the generalization before using it for specific instances. So an argument using deductive reasoning would look like this: reducing the number of meetings has helped companies the world over, so it could improve one specific company. With this rhetorical device, you’re appealing to people’s logical thinking to convince them you’re right.

You can also use ethos to convince people of your opinion. This rhetorical device involves appealing to others’ sense of ethical values by showing your credibility, reliability, and good character. This isn’t always a simple feat to pull off, especially when people have little familiarity with you. However, establishing that you’re trustworthy helps sway people to your side.

How to gain the audience’s trust:

- Portray opposing viewpoints of the other writer or speaker accurately.

- Organize the argument so it’s easy for people to follow.

- Use reliable third-party sources.

- Ensure all information you use is accurate.

- Indicate why the subject interests you.

- Meet the audience on common ground by indicating shared beliefs and moral values.

- Check your argument for any spelling or grammatical mistakes if you’re writing it.

The pathos rhetorical device involves appealing to others’ emotions through language. Utilizing pathos can be tricky to do well. After all, the goal should be to persuade people based on facts, logic, and reasoning. However, pathos can add to an argument, presenting a real human element that avoids sticking to numbers and statistics like a robot. For example, a story about a woman who sacrificed time and money to get her business off the ground will likely resonate with an audience more than citing the number of people who start a business every year. The statistic is still valid, but it may not capture the actual cost. Take care not to misuse pathos as well. Don’t turn your argument into a sensational piece. You should also make sure pathos pertains to the subject, as some people will use pathos to distract from the issue at the heart of the debate.

8. Narration

Narration, which is essentially storytelling, is another strategy you can use to connect with your audience. People identify with stories more than they do statistics, even in academic writing. The best storytellers seamlessly incorporate their evidence and arguments into the stories they share. That doesn’t mean an entire speech or article should consist of one or multiple stories, but they can back up the central point of your argument. The right story at the right time can serve as the exclamation point of your persuasive piece, whether it’s real or a rhetorical situation. It’s a powerful strategy that helpfully places issues in perspective.

One way to hurt your argument is by using a logical fallacy. A logical fallacy is a false, illogical statement said with the intent of persuading an audience. Using this type of rhetorical device ultimately weakens your chances of successfully influencing someone. As such, you should avoid them as much as possible. The following are just several logical fallacies you should take care to reject.

- Straw Man: A straw man argument misrepresents an opponent’s argument, often through oversimplification or distortion.

- Ad Hominem: This involves attacking the person who makes the argument rather than the argument.

- Appeal to Majority: Also known as the bandwagon fallacy, an appeal to majority indicates that your position is correct because more people agree with you.

- False Dilemma: This fallacy places two—and only two—choices for people to consider when more options are out there.

- Appeal to Nature: The appeal to nature fallacy indicates that because something is natural, it automatically makes it better.

- Circular Argument: When someone engages in a circular argument, they repeat what they already assumed before because they believe it is proof enough.

The above rhetorical strategies can help you start writing or practicing a verbal argument that persuades people to come to your side of the fence. In business, the power to influence others through assertive communication is essential once you know what course you want to take. No matter the debate, also show respect and courtesy and don’t let arguments become personal. For example, you might want to ask the other person genuine questions about their position. Through a healthy and polite discourse, you’ll eventually reach an agreement that both sides can appreciate.

Want to work on more new skills that can help in your professional and personal life? The following articles can help:

The Top 5 Communication Skills Every Leader Needs

Top Leadership Skills Those in a Leadership Role Need

Why is Empathy Important as a Business Leader?

Search Leaders.com

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Rhetoric: How to Inform, Persuade, or Motivate your Audience

June 12, 2018 - Gini Beqiri

Persuasive speaking is needed in a wide range of situations; from arguing with a colleague, to haggling down a price, to performing a speech. Rhetoric is the key to developing this skill. In this article, we discuss how to use rhetoric for effective public speaking.

What is rhetoric?

Rhetoric is the study and art of writing and speaking persuasively. Its aim is to inform, educate, persuade or motivate specific audiences in specific situations. It originates from the time of the ancient Greeks.

Rhetoric is the art of ruling the minds of men – Plato

Rhetoric is not just a tool used only in speeches, you use it in everyday life when, for example, you only disclose certain parts of your weekend to certain people.

Treatise of rhetoric

Aristotle stated that there are three types of persuasive speech:

- Forensic / judicial rhetoric – looks at the justice or injustice of accusations and establishes evidence about the past. It’s used mainly in a court of law.

- Epideictic / demonstrative rhetoric – praises or blames and makes a declaration about the present situation. It’s used in, for example, wedding and retirement speeches etc.

- Symbouleutikon / deliberative rhetoric – tries to get the audience to take action by talking about a possible future. Politicians often use this approach and Martin Luther’s “I have a dream” speech is a good example.

Rhetorical situations

To use rhetoric you must first:

- Analyse the rhetorical situation you are in – an effective speech is one that responds to its rhetorical situation (context)

- Identify what needs to be communicated

- Provide a strategic response using rhetorical tools

When you analyse the rhetorical situation think about the following:

The rhetor (yourself) – the person speaking to the audience. Your personal characteristics and beliefs will influence what you decide to say, such as:

- Geographical location

- Previous experiences

- Socio-economic status, etc

The audience – the people you are trying to persuade . Usually the same factors that affect the rhetor affect the audience. Think about what they already know. What questions or reservations might they have? What expectations do they have? Where should you conform to and stray from these expectations?

The setting – the situation which causes the need for your speech, for example, current events, location, time period, political situation etc. Where is the speech happening and when? How do these this impact you? For example, speeches may need to differ between countries.

The topic – needs to be relevant to the rhetorical situation you are in. How does your topic limit what you can do for the audience? Depending on your audience, what should you include or exclude?

The purpose – why are you saying this? Is it to:

- Instigate action, etc

Five canons and three appeals

The five canons of rhetoric.

The Five Canons of Rhetoric are tools for creating persuasive speeches:

- Invention – the process of developing an argument. For this you need to pick effective content and sort through everything you could say and decide what should be included or excluded. There needs to be a balance between what the audience needs to hear and what you need to say.

- Arrangement – once you have determined the content you must organise and order your speech to create the most impact, such as thinking about how long each section should be and what should follow on from one point etc.

- Style – deciding how to present your chosen arguments, including thinking tactically about how your audience will respond to your word choices. Perhaps include visualisation or other techniques to evoke emotions. (See rhetorical devices and tools)

- Memory – memorising your speech.

- Delivery – this includes your projection, gestures , eye contact , pronunciation, tone and pace .

The three appeals

According to Aristotle, rhetoric rests on the three appeals: ethos, logos and pathos . They are modes of persuasion used to convince an audience.

- Ethos : your credibility and character

- Pathos : emotional bond with your listeners

- Logos : logical and rational argument

Ethos – the ethical appeal

Ethos consists of convincing your audience that you have good character and you are credible therefore your words can be trusted. Ethos must be established from the start of your talk or the audience will not accept what you say. In fact, ethos is often established before your presentation, for example, you may be the CEO of the company you’re presenting to so you’re already perceived as a specialist.

Characteristics of ethos

There are four main characteristics of ethos:

- Trustworthiness and respect

- Similarity to the audience

- Expertise and reputation/history

Improve ethos

- Ensure that people know about your expertise by promoting yourself, for example, ensure that people can easily access testimonials, reviews, papers etc.

- In your introduction draw attention to your ethos.

- Tell personal stories that show the audience that you follow your own recommendations because they are more likely to believe you on other points that cannot easily be confirmed.

- Facts, stats and quotes should be up-to-date and from reputable sources, for example, between choosing from social media or Mind’s website to quote a statistic about anxiety, you would choose Mind’s website as this has high ethos which in turn increases your ethos.

- Be unbiased by admitting that you and your opposition’s side agree on at least one matter. This highlights that you are credible because you are treating the topic with consideration and fairness.

- Stick to your promises, for example, during the Q&A you may have agreed to find out an answer to a question and tell everyone – ensure that you do this to be seen as honest.

Pathos – the emotional appeal

Pathos is to persuade by appealing to the audience’s emotions. Pathos is more likely to increase the chances of your audience:

- Understanding your point of view

- Accepting your arguments

- Acting on your requests

Improving pathos

- Use analogies and metaphors – linking your ideas with something your listeners already know about and feel strongly about can trigger emotional responses. For example, “They are terrible” compared to “They are poisonous.” This will use the audience’s knowledge that poison is bad and therefore this issue needs to be dealt with.

- Use emotionally charged words, for example, say “This brush is a life-saver” rather than “This brush is amazing.”. Another way to make a statement more emotional is to use vivid and sensory words which allow the audience to experience the emotion. For instance, “The smell of your grandparent’s house” will increase the recollection of, hopefully warm memories, and therefore will trigger certain emotions.

- Positive emotions, such as joy, should be linked with your claims.

- Negative emotions, such as anger, should be linked to your rival’s claims.

- Visual aids can sometimes be more powerful than words

- Storytelling is a quick way to form an emotional connection

- Match what you’re saying with your body language, face and eyes

- You may target the audience’s hopes by describing a positive future situation if your proposed actions are followed

Logos – logical appeal

Logos is to appeal to logic by relying on the audience’s intelligence and offering evidence in support of your argument. Logos also develops ethos because the information makes you look knowledgeable. Logos is important because logical arguments are not easily dismissed.

Improving logos

Be comprehensive : Make sure your points and arguments can be understood

- Use language that your audience will understand. Avoid jargon and technical terminology

- Use figures and charts

- Make the relationships between your evidence and conclusions clear

- Use analogies and metaphors

Be logical : Ensure that your arguments make sense and that your claims and evidence are not implausible. Have a plan for dealing with opposing viewpoints that your listeners may already believe.

- Ensure that the audience is involved by asking them engaging questions.

- Talk about opposing views as this allows you to explain why your logical arguments are more reasonable.

- Build your argument on the audience’s widely held beliefs – commonplaces. For example, a company’s main value and therefore commonplace may be “Compassion makes us the best company”. Use the audience’s commonplace like a fact and apply it to a new situation. So if you want to encourage your staff to join a committee, use their commonplace, for example, rather than your belief say: “This committee needs considerate and kind-hearted people.”

Be specific : Base your claims on facts and examples as your arguments will be accepted quicker than something nonspecific and non-concrete. The more easily the evidence is accepted, the more easily the conclusions will be accepted.

- Facts and stats cannot be debated and they signify the truth.

- Visual evidence, such as, objects and videos are hard to challenge.

- Citing specialists and authorities on a topic increases the quality of your evidence and therefore your claims.

- Tell stories, such as, case studies or personal experiences. The audience would like to hear your own stories if you’re a specialist, for example, “When I was excavating in Nottingham…”

There is uncertainty over which pillar is the most important – Aristotle thought that logos was vital but when used by itself it lacks impact. So ensure that you treat all three pillars with equal importance to succeed in persuading your audience.

Rhetorical modes

Rhetorical modes are patterns of organisation used to produce a specific effect in the audience. They assist in increasing the speaker’s ethos, pathos and logos.

- Telling a story or narrating an event.

- Uses facts – what happened, where it happened, when it happened and who was there.

- It helps put information into a logical order – usually chronological order.

- Purpose : to evoke certain emotions in the audience.

Description

- Re-create, inventing or visually presenting a person, place, object, event or action through words

- This helps the audience imagine what is being described

- Use precise verbs and nouns and vivid adjectives

- Using the five senses is especially useful

- Purpose : to evoke certain emotions in the audience

Argumentation/Persuasion

- Articulating your opinion about an issue – proving or contesting a point or view or an issue.

- Consists of presenting the evidence.

- Inductive arguments- Forming generalisations from the evidence. For example: “All the theme parks I have been to have been safe. This is a theme park. So it must be safe.”

- Deductive arguments – Forming conclusions from generalisations. For example. “I don’t like busy places. That shopping centre is really busy. So I won’t like that shopping centre.”

- Persuasion is a type of argumentation with a call to action directed at the audience.

- Purpose : the speaker tries to get the audience to agree with their opinion and in the case of persuasion the speaker tries to get the audience to take action.

- Informing, instructing or presenting ideas objectively. Exposition can use the following techniques:

Illustration/Example

- Using evidence to explain a general idea or statement.

- The stronger your evidence, the more likely the audience will consider your points.

- Usually used to support an argument.

- Use evidence suitable for your topic and audience.

- How complex the topic is

- The audience’s knowledge

- Purpose : gives your statements/arguments more credibility and helps the audience understand more quickly.

- Explaining what a word, idea etc means to your audience and/or to explain what it is not.

- This is more difficult than looking up the term in a dictionary because you may be re-defining a common term or explaining a term that is commonly used incorrectly, such as, the word depression.

- By reshaping what the audience thought a concept meant they can see and think about that concept in a different way.

- There are multiple ways you can define something, it doesn’t have to be in a clinical way – you can use the rhetorical strategies discussed later.

- Purpose : helps the audience see things from your point of view.

Process analysis

- Explaining how a particular event occurs or how something is done or how something works, for example, how to sew, or how to move on from the death of a loved one.

- This procedure is usually explained in clear steps.

- Purpose : to provide clear information so the audience can fully understand – the more the audience understands, the more likely they will be persuaded.

- Dividing one concept into smaller ones.

- This can be helpful for you, the speaker, as it can provide the audience with an insight of how you view a concept.

- Purpose : to help the audience understand a complex issue.

Classification

- Often looking at a diverse group of objects and finding similarities.

- The rhetor creates categories based on the similarities and gives each category a name.

- Purpose : useful for organising complex issues.

Cause and effect

- Examining the causes of a situation and the consequences of it.

- Causes help you understand why something happened and effect helps you understand what could happen or what has happened.

- Especially useful when the rhetor can show a cause and effect relationship the audience haven’t noticed before because this helps the audience see the situation in a different way.

- Often leads to debates as it’s not always easy to determine this relationship.

- Purpose : to determine how concepts are related to each other.

Comparison and contrast

- Comparison looks at similarities and contrast looks at differences.

- The more divergent the two things initially appear the more interesting it will be to look at the similarities.

- Purpose : generally to show something is more superior to another, to show unexpected similarities or to help the audience understand a person, place, idea etc in relation to another.

Rhetorical devices and tools, with examples

Rhetorical devices can be useful for assisting with the above modes of persuasion:

Adynaton – a type of hyperbole (exaggeration) in which the exaggeration is taken to such extreme lengths to suggest impossibility.

- Example: “When pigs fly!”

Alliteration – the occurrence of the same letter or sound at the beginning of several words that are close in proximity to each other.

- Example: “The dog dived deeply.”

- Example: “Maybe she’s born with it. Maybe its Maybelline.”

Allusion – a reference to an event, literary work, person etc usually within popular culture.

- Example: “It’s only £10, you’re acting like Scrooge.”

Anaphora – repeating a word or phrase in successive phrases.

- Example: “As you know, we’ve got the iPod, best music player in the world. We’ve got the iPod Nanos, brand new models, colours are back. We’ve got the amazing new iPod Shuffle.” – Steve Jobs

Antanagoge – when a negative point is followed by a positive one to reduce the impact.

- Example: “It’s expensive but it’s unbreakable”

Antimetabole – a phrase or sentence is repeated in reverse order.

- Example: “It is not even the beginning of the end but is perhaps, the end of the beginning.” – Winston Churchill

Antiphrasis – a phrase or word that is opposite to its literal meaning to create an ironic or comic effect.

- Example: Calling your friend Tiny even when they are 6 foot 5.

Antithesis – two opposite ideas are put together in a sentence for contrast.

- Example: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” – Neil Armstrong

Appositive – places a noun or phrase next to another noun for descriptive purposes.

- Example: “Your friend Sam is waiting outside for you.”

- Example: “The neurologist, a well-renowned expert in Paediatric Neurology, looked at the scans.”

Epanalepsis – repeating the initial part of a sentence at the end of the same sentence.

- Example: “Today, I want it done today.”

Epithet – using an adjective or phrase to emphasises a person’s characteristics. Often, this adjective or phrase becomes linked to the person and can be used with their name or instead of their name.

- Example: Eddie the Eagle

Epizeuxis – repeats one word in immediate succession for emphasis.

- Example: “That film was great, great, great.”

Hyperbole – an exaggeration not meant to be taken literally.

- Example: “I’ve got tons of work to get through.”

- Example: “I’m freezing.”

Metanoia – correcting a statement you just made deliberately to strengthen or soften it.

- Example: “This has made my day, no, my month.”

Metaphor – a comparison made by stating one thing is the other.

- Example: “This cake is heaven.”

Metonymy – where something is referred to by the name of something closely associated with it.

- Example: Referring to business professionals as “suits.”

- Example: Referring to royals as “Crown.”

- Example: Referring to a plate of food as a “dish.”

Onomatopoeia – words that are similar to the sound they describe.

- Example: Drip, pop, buzz, bang

Oxymoron – a combination of contradictory words.

- Example: Cruel kindness, definitely maybe, open secret

Parallelism – uses components in a sentence that are similar grammatically or in their construction, sound or meaning. It makes sentences flow better by adding rhythm.

- Example: “The dog was barking, the bell was ringing and the children were shouting.”

Personification – The attribution of human characteristics to something non-human.

- Example: “The traffic slowed to a crawl.”

Simile – compares one thing to another to make a description more vivid, usually uses “as” or “like”.

- Example: “As light as a feather.”

Understatement – deliberately making a situation sound less important or serious than it is. You can use it for humour, to be polite or to remain modest over something.

- Example: You won an award for a piece of artwork but you say “It’s no big deal.” (Modest)

- Example: Your friend is worried about people staring at a stain on his T-shirt, you say “I wouldn’t have even noticed if you hadn’t said anything.” (Polite)

- Example: You walk outside with your coat on and realise it’s very hot – “I may be a little over-dressed.” (Humour)

Criticisms of rhetoric

Some people believe that rhetoric is a type of lying or false behaviour and manipulation. However, even when you’re criticising rhetoric, you are engaging in an act of rhetoric because you are trying to get others to agree with you.

Rhetoric works well in many situations, such as, in business presentations, lectures etc. So rhetoric is a good tool but, like with other tools, it’s up to you how to use it effectively.

31 Useful Rhetorical Devices

What is a rhetorical device and why are they used.

As with all fields of serious and complicated human endeavor (that can be considered variously as an art, a science, a profession, or a hobby), there is a technical vocabulary associated with writing. Rhetoric is the name for the study of writing or speaking as a means of communication or persuasion, and though a writer doesn’t need to know the specific labels for certain writing techniques in order to use them effectively, it is sometimes helpful to have a handy taxonomy for the ways in which words and ideas are arranged. This can help to discuss and isolate ideas that might otherwise become abstract and confusing. As with the word rhetoric itself, many of these rhetorical devices come from Greek.

Ready, set, rhetoric.

The repetition of usually initial consonant sounds in two or more neighboring words or syllables

wild and woolly, threatening throngs

Syntactical inconsistency or incoherence within a sentence especially : a shift in an unfinished sentence from one syntactic construction to another

you really should have—well, what do you expect?

Repetition of a prominent and usually the last word in one phrase or clause at the beginning of the next

rely on his honor—honor such as his?

A literary technique that involves interruption of the chronological sequence of events by interjection of events or scenes of earlier occurrence : flashback

Repetition of a word or expression at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect

we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground

The repetition of a word within a phrase or sentence in which the second occurrence utilizes a different and sometimes contrary meaning from the first

we must all hang together or most assuredly we shall all hang separately

The usually ironic or humorous use of words in senses opposite to the generally accepted meanings

this giant of 3 feet 4 inches

The use of a proper name to designate a member of a class (such as a Solomon for a wise ruler) OR the use of an epithet or title in place of a proper name (such as the Bard for Shakespeare)

The raising of an issue by claiming not to mention it

we won't discuss his past crimes

An expression of real or pretended doubt or uncertainty especially for rhetorical effect

to be, or not to be: that is the question

Harshness in the sound of words or phrases

An inverted relationship between the syntactic elements of parallel phrases

working hard, or hardly working?

A disjunctive conclusion inferred from a single premise

gravitation may act without contact; therefore, either some force may act without contact or gravitation is not a force

The substitution of a disagreeable, offensive, or disparaging expression for an agreeable or inoffensive one

greasy spoon is a dysphemism for the word diner

Repetition of a word or expression at the end of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect

of the people, by the people, for the people

Emphatic repetition [ this definition is taken from the 1934 edition of Webster's Unabridged dictionary ]

An interchange of two elements in a phrase or sentence from a more logical to a less logical relationship

you are lost to joy for joy is lost to you

A transposition or inversion of idiomatic word order

judge me by my size, do you?

Extravagant exaggeration

mile-high ice-cream cones

The putting or answering of an objection or argument against the speaker's contention [ this definition is taken from the 1934 edition of Webster's Unabridged dictionary ]

Understatement in which an affirmative is expressed by the negative of the contrary

not a bad singer

The presentation of a thing with underemphasis especially in order to achieve a greater effect : UNDERSTATEMENT

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them ( Metaphor vs. Simile )

drowning in money

A figure of speech consisting of the use of the name of one thing for that of another of which it is an attribute or with which it is associated

crown as used in lands belonging to the crown

The naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it

A combination of contradictory or incongruous words

cruel kindness

The use of more words than those necessary to denote mere sense : REDUNDANCY

I saw it with my own eyes

A figure of speech comparing two unlike things that is often introduced by "like" or "as"

cheeks like roses

The use of a word in the same grammatical relation to two adjacent words in the context with one literal and the other metaphorical in sense

she blew my nose and then she blew my mind

A figure of speech by which a part is put for the whole (such as fifty sail for fifty ships ), the whole for a part (such as society for high society ), the species for the genus (such as cutthroat for assassin ), the genus for the species (such as a creature for a man ), or the name of the material for the thing made (such as boards for stage )

The use of a word to modify or govern two or more words usually in such a manner that it applies to each in a different sense or makes sense with only one

opened the door and her heart to the homeless boy

MORE TO EXPLORE: Rhetorical Devices Used in Pop Songs

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Usage Notes

Prepositions, ending a sentence with, hypercorrections: are you making these 6 common mistakes, a comprehensive guide to forming compounds, can ‘criteria’ ever be singular, singular nonbinary ‘they’: is it ‘they are’ or ‘they is’, grammar & usage, words commonly mispronounced, more commonly misspelled words, is 'irregardless' a real word, 8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, great big list of beautiful and useless words, vol. 3, even more words that sound like insults but aren't, the words of the week - mar. 22, 12 words for signs of spring.

4 Ways to Use Rhetorical Devices to Make Powerful Speeches (with Examples)

Hrideep barot.

- Speech Writing

I am certain all of us have come across powerful speeches, novels, or presentations that left us speechless at some point. But have you wondered how the speaker or the author managed to do so?

How did they manage to make almost everyone in the audience riveted? You might have attributed this skill of captivating the audience to good public speaking, which is partially true but the other half of this lies in their use of magic tools which are referred to as rhetorical devices.

A rhetorical device is a technique that is used by a speaker or an author for conveying a particular message to the audience in such a way that it provokes an emotional response to a particular action. It is a linguistic tool, whose employment can be used to construct an argument or make an existing one more compelling .

To put it simply, rhetorical devices are devices used to spice up your conversations, work presentations, and speeches. They are often used to provoke an emotional response and make the matter of the speech more compelling, with the goal of persuading the audience.

Why are rhetorical techniques important?

Why should rhetorical devices be used? What impact do they have? Well, here’s why,

There is one common thing between the world’s famous speeches and presentations, which is their ability to create an emotional connection with the audience. The way in which a speaker makes the audience feel is very important as that feeling will stay with the audience long after the speech or the presentation is over. This emotional response is evoked with the help of rhetorical devices.

Apart from this, rhetorical devices help you become more persuasive. It also aids in composing successful presentations and writings. It helps you make your speech crisp and improves the understanding of the audience.

Moreover, with the correct rhetorical devices, it enables you to make stronger arguments and a way of handling controversial topics. It also has a powerful impact on the audience helping them remember the ideas better through repetition or grammatical manipulation.

Most used rhetorical devices

In order to know how to use these magic tools, it is crucial to know some of these most used rhetorical devices and also its application in a speech.

1. Alliteration

This is the repetition of sounds of two or more neighboring words. This is usually used to put emphasis and to draw attention. For instance, safety and security Ate apples all afternoon

2. Anadiplosis

Repetition of the last word in a phrase at the beginning of the next phrase or sentence. For example, Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate and hate leads to suffering –Yoda, Star Wars

3. Antistrophe

This is repetition of words at the end of consecutive phrases/clauses. It can be termed as a specific type of repetition. “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny compared to what lies within us.”

The above sentence is quoted by Ralph Waldo Emerson, a prominent essayist. Here, the words ‘What lies’ is repeated leading to the creation of a poetic effect.

4. Antithesis

In this, two opposite and contrasting ideas are juxtaposed. For example, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

Here, two contrasting ideas are proposed in the same sentence in such a way that it shows the strikingly different ideas showing a compare and contrast kind of situation.

A repeated word or phrase split up by another word, to display strong emotion. Understanding it with an example, Free at last! Free at last! Thank god we are free at last!

6. Ellipsis

In this, few words are depicting an event is omitted making the readers ponder about the narrative gaps. For instance, “Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth…the proposition that all men are created equal.”

This is the start of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, where the three dots are ellipsis points suggesting a time lapse.

This is a simple method of double negatives that present a positive statement. It is often used to express irony. This is commonly used in conversations as well.

For example, ‘She is not thin’ OR ‘You are not unfamiliar with poetry’.

8. Hyperbole

This is an expression of mere exaggeration, often used to draw attention to the severity of the matter or to make a strong point. This is also frequently used in day to day language.

For instance,

‘I called her a thousand times’

‘It raining cats and dogs’.

9. Epistrophe

Repetition of words at the end of successive phrases for a poetic effect. An example of this could be the famous definition of democracy given by Abraham Lincoln, “… and that the government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

10. Personification

Attributing human qualities to inanimate objects. It aids in a better explanation of ideas and concepts.

For instance, ‘The thunder roared in the evening’

‘The brutal wind bullied the trees compelling them into giving up their leaves’

11. Epiphora

Repetition of a word/phrase at the end of every clause. An instance of this could be a speech given by Steve Jobs where this technique is effectively used,

“Well, these are their home screens . And again, as you recall, this is the iPhone’s homescreen. This is what their contacts look like . This is what iPhone’s contacts look like .”

12. Anaphora

This is slightly different from Epiphora in the sense that the repetition of the word/phrase is at the beginning of the two or more sentences or clauses.

For instance, “They’re the women whose names we’ll never know. They are domestic workers and farm workers. They are working in factories and they work in restaurants and in academia, and engineering, medicine and science. They are part of the world of tech and politics and in business. They are athletes in the Olympics and they are soldiers in the military.”

This is a small chunk of a speech made by Oprah Winfrey at the Golden Globes awards. Here, she tries to draw attention of the audience by emphasising on the word ‘They are’ highlighting the role of women in different parts of life.

13. Germinatio

This is repetition of a word in the same sentence for more than once. For instance, “And so I’ve got voice mail how I wanna listen to it, when I wanna listen to it, in any order I wanna listen to it with visual voicemail.”

The technique of germinatio was used by Steve Jobs in his speech in order to create a compelling effect on the listeners.

These are just a few commonly used rhetorical devices from an ocean of such magic tools. (Take a guess at what device is used here!)

How to use rhetorical devices in speeches?

Before we dive in to how to use rhetorical devices, we made a fun video on how these tools are the one simple thing that helps take your speech to the next level. There are a bunch of examples and tips here that will help you incorporate rhetorical devices for your next presentation. Highly recommend you check it out:

To know how to implement these rhetorical devices in your speech is also of utmost importance, apart from knowing them. Here’s a way of incorporating them in your speech.

1. Know the rhetorical appeals

It is important to know the types of rhetorical appeals as rhetorical devices fall into these categories. Make a rough draft and then insert rhetorical devices accordingly depending on the tone of the speech. Figure out the mode of persuasion, that is, whether it is Logos, Pathos, Ethos or Kairos.

This refers to giving logical and intellectual arguments and reasoning, supporting it with credible evidence. An example of logos can be a speech by Donald Trump, where he states a few figures regarding the illegal immigration,

“So here are just a few statistics on the human toll of illegal immigration. According to a 2011 government report, the arrests attached to the criminal alien population included an estimated 25,000 people for homicide, 42,000 for robbery, nearly 70,000 for sex offenses, and nearly 15,000 for kidnapping. In Texas alone, within the last seven years, more than a quarter-million criminal aliens have been arrested and charged with over 600,000 criminal offenses. … Sixty-three thousand Americans since 9/11 have been killed by illegal aliens. This isn’t a problem that’s going away; it’s getting bigger.”

This refers to making an appeal to the audience’s emotions. This includes using language in such a way that creates an empathetic feeling towards the speaker. Given below is an example of Martin Luther King Jr. “I have a dream” speech.

“Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends. And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

This refers to persuading the audience about the speaker’s credibility and the fact that his arguments carry weight.

An example of this could be the speech made by Mitt Romney, senator of the United States. In this speech, accepting the presidential nominee Mitt Romney points out to the fact that his business success would prove useful if he were to take the office.

“I learned the real lessons about how America works from experience. When I was 37, I helped start a small company. My partners and I had been working for a company that was in the business of helping other businesses. So some of us had this idea that if we really believed our advice was helping companies, we should invest in companies. We should bet on ourselves and on our advice. So we started a new business called Bain Capital…That business we started with 10 people has now grown into a great American success story. Some of the companies we helped start are names you know. An office supply company called Staples – where I’m pleased to see the Obama campaign has been shopping; The Sports Authority, which became a favorite of my sons. We started an early childhood learning center called Bright Horizons that First Lady Michelle Obama rightly praised.”

This involves an appeal to the timing of the argument, meaning that the argument has to be made in a suitable context making the audience receptive to it. An instance of Kairos can be Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech,

“This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to make to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.”

One can use these rhetorical appeals in such a way that a combination of all 4 appeals is made simultaneously.

Making the speech highly logos specific, that is giving only facts, will make the audience bored, whereas making it too pathos oriented will make the speech very emotional and lacking in rational thinking.

If you would like some more information on ETHOS, PATHOS and LOGOS, you can check out the same in this short video we made:

2. A rhetorical question

Rhetorical questions can be used to control the thoughts of the audience. These questions may have obvious answers or may not have a clear cut answer.

One technique of using such questions is inserting them in the start of the speech and then carrying on with the speech in such a way that the rhetorical question is answered in the content of your presentation.

Another way is by inserting a rhetorical question, which as an obvious answer to it at the end of the speech- making sure that the question is related to what the speech entails.

The election speech of Ronald Reagan for the 1980 presidential debate between Governor Ronald Reagan and President Jimmy Carter, where the governor ended with a bunch of rhetorical questions is a perfect example for this,

“Next Tuesday is Election Day. Next Tuesday all of you will go to the polls, will stand there in the polling place and make a decision. I think when you make that decision, it might be well if you would ask yourself, are you better off than you were four years ago? Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was four years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe, that we’re as strong as we were four years ago? And if you answer all of those questions yes, why then, I think your choice is very obvious as to whom you will vote for. If you don’t agree, if you don’t think that this course that we’ve been on for the last four years is what you would like to see us follow for the next four, then I could suggest another choice that you have.”

Check it out in action, here:

3. A powerful beginning

It is rightly said that the first impression is the last impression and hence a powerful beginning is very important. To capture the audience it is important to insert some rhetorical devices at the start of your speech which create some poetic effect that helps you engage the audience. It may also include the use of diacope or anadiplosis which focus on repetition of the words of phrases creating emphasis and a strong display of emotions.

An example of anadiplosis can be: “Tonight, we are a country awakened to danger and called to defend freedom. Our grief has turned to anger, and anger to resolution.” This was used by the George W. Bush

4. A powerful end

Climax is the most important part, be it a speech or a movie! What you say in the end is what stays with the audience hence, ending the speech with impactful rhetorical devices is advisable.

These may include inserting a rhetorical question making the audience ponder a little as mentioned above. It may also include the use of Epistrophe.

For instance, while addressing the nation about terrorism George Bush ends his speech in a powerful way assuring people that he will take the necessary actions to prevent terrorism, with appropriate use of Epistrophe:

“I will not forget the wound to our country and those who inflicted it. I will not yield, I will not rest, I will not relent in waging this struggle for freedom and security for the American people.”

Watch the full speech here:

Use of rhetorical devices by Frederick Douglass

The credit for developing the basics of rhetoric goes to Aristotle and since then there has been extensive use of these literary tools. A prominent figure who is well known for his use of rhetorical devices is also Frederick Douglass, who was a slave who had escaped and went on to become an activist, author and public speaker.

He is known not only for his idea of abolition of slavery but also his superior skill of rhetoric and the art of persuading the audience. In his memoir called the ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’, a number of rhetorical devices are used to argue against the heinous act of slavery.

Here is a look at how he used some of them to make his communication all the more poewrful:

It involves persuading the audience about the author’s qualifications and credibility pointing to the fact that the speaker’s arguments carry weight.

In the memoir, Frederick Douglass talks about his first-hand experience with slavery by talking about being oblivious about his birthday unlike other people in the first chapter itself, building his ethos.

In order to make an appeal to the audience’s emotions, Douglass talks about his experience of watching his aunt being whipped by the slaveholder until she is covered in blood.

Frederick writes, ‘He would at times seem to take great pleasure in whipping a slave. I have often been awakened at the dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an own aunt of mine, whom he used to tie up to a joist, and whip upon her naked back till she was literally covered with blood. No words, no tears, no prayers, from his gory victim, seemed to move his iron heart from its bloody purpose. The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest. He would whip her to make her scream, and whip her to make her hush; and not until overcome by fatigue, would he cease to swing the blood-clotted cow skin.’

Frederick talks about how animals were treated better than humans by the slaveholder.

He writes about the condition of the slaves by saying:

‘Everything depended upon the looks of the horses, and the state of Colonel Lloyd’s own mind when his horses were brought to him for use. If a horse did not move fast enough, or hold his head high enough, it was owing to some fault of his keepers. It was painful to stand near the stable-door, and hear the various complaints against the keepers when a horse was taken out for use. To all the complaints, no matter how unjust, the slave must answer never a word. Colonel Lloyd could not brook any contradiction from a slave. When he spoke, a slave must stand, listen, and tremble; and such was literally the case. I have seen Colonel Lloyd make old Barney, a man between fifty and sixty years of age, uncover his bald head, kneel down upon the cold, damp ground, and receive upon his naked and toil-worn shoulders more than thirty lashes at the time.’

In Fredrick Douglass’s speech- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”, he also makes a similar appeal through the use of ethos, pathos and logos . To begin with, he makes an appeal to ethos, by initiating his speech with modesty and meekness. For example, “He who could address this audience without a quailing sensation, has stronger nerves than I have.”

To steer emotions among the audience, he also uses metaphors such as “A horrible reptile is coiled up in your nation’s bosom; the venomous creature is nursing at the tender breast of your youthful republic . “

“From the round top of your ship of state, dark and threatening clouds may be seen.” This is an example of an extended metaphor where he is comparing the United States to a ship at sea and the dark and threatening clouds are compared to the ongoing threats and troubles.

There has also been use of simile , where the speaker makes a direct comparison of the slaves to animals sold in the market. For example, “I hear the doleful wail of fettered humanity, on the way to the slave-markets, where the victims are to be sold like horses, sheep, and swine.”

Other Rhetorical Devices used by Douglas

Moreover, through the phrase ‘ doleful wail of fettered humanity ’ the speaker is trying to give the human quality of being fettered to an abstract noun of humanity, pointing out to the use of personification .

Apart from these rhetorical devices, Frederick Douglass also uses rhetorical questions to make the audience ponder about the situation of slavery by asking them, “Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? Or is it in the temple?”

“What would be thought of an instrument, drawn up, legally drawn up, for the purpose of entitling the city of Rochester to a tract of land, in which no mention of land was made?”

Another important rhetorical device used by him was that of allusion . Allusion is when the author or the speaker refers to an event, object, person or to a work of art either directly or indirectly. In his speech, Frederick alludes to biblical material, knowing that the audience mostly comprises of Christians.

For instance, “ The arm of the Lord is not shortened, and the doom of slavery is certain.” Through this, the speaker makes an analogy between the Lord sending the Israelites back to their homeland and the hope that slavery will perish. Frederick Douglass has made such allusions in order to support his arguments, knowing that words from the bible would carry weight and have a strong impact.

Use of rhetorical devices in famous speeches

1. michelle obama – anaphora.

“I trust Hillary to lead this country because I’ve seen her lifelong devotion to our nation’s children – not just her own daughter, who she has raised to perfection but every child who needs a champion: Kids who take the long way to school to avoid the gangs. Kids who wonder how they’ll ever afford college. Kids whose parents don’t speak a word of English but dream of a better life. Kids who look to us to determine who and what they can be.”

This is a small part of a speech made by Michelle Obama. In this, it is seen the word “ Kids ” is used more than once to start sentences that follow each other, pointing out to the use of anaphora.

Here’s the video for the speech made by the former first lady:

2. Steve Jobs – Germination

“That’s 58 songs every second of every minute of every hour of every day.”

This is an instance from the speech of Steve Jobs, where he puts emphasis on the word “ every ” by repeating it frequently in the same sentence.

See the entire speech here:

3. Barack Obama – Antistrophe

“It was a creed written into the founding documents that declared the destiny of a nation: Yes, we can. It was whispered by slaves and abolitionists as they blazed a trail towards freedom through the darkest of nights: Yes, we can. It was sung by immigrants as they struck out from distant shores and pioneers who pushed westward against an unforgiving wilderness: Yes, we can.”

Here, the phrase “Yes, we can” is used repeatedly at the end of every sentence in order to put emphasis on the subject.

Watch the video of the speech here:

4. Martin Luther King, Jr – Antithesis

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Here, the speaker uses antithesis by inverting the statements to show that America will have a day when people are judged by their character and not their skin colour.

Given below is the historic speech made at the Lincoln Memorial by Martin Luther King Jr :

5. John Kennedy – Ellipsis

“This much we pledge — and more.”

Here the former President uses “and more” instead of listing more ideas. He also compels the audience to keep thinking about the ideas they should pledge to, instead of listing them.

In order to use a wide variety of rhetorical devices, it is important to know the different types of these literary techniques. A powerful speech is not just about a good orator or good public speaking skills but much more than that! And these rhetorical devices constitute an integral part of the components which make your speech extraordinary.

Enroll in our transformative 1:1 Coaching Program

Schedule a call with our expert communication coach to know if this program would be the right fit for you

Call or Text? Deciphering the Best Communication Method for Every Situation

Spontaneous Speaking Skills for Any Situation

Keep Your Cool: 8 Strategies to Control Emotions While Speaking

- [email protected]

- +91 98203 57888

Get our latest tips and tricks in your inbox always

Copyright © 2023 Frantically Speaking All rights reserved

Kindly drop your contact details so that we can arrange call back

Select Country Afghanistan Albania Algeria AmericanSamoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Colombia Comoros Congo Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Rwanda Samoa San Marino Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Tajikistan Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Wallis and Futuna Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe land Islands Antarctica Bolivia, Plurinational State of Brunei Darussalam Cocos (Keeling) Islands Congo, The Democratic Republic of the Cote d'Ivoire Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Guernsey Holy See (Vatican City State) Hong Kong Iran, Islamic Republic of Isle of Man Jersey Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Lao People's Democratic Republic Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Macao Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova, Republic of Mozambique Palestinian Territory, Occupied Pitcairn Réunion Russia Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan Da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Sao Tome and Principe Somalia Svalbard and Jan Mayen Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan, Province of China Tanzania, United Republic of Timor-Leste Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of Viet Nam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S.

Chapter 6: Thinking and Analyzing Rhetorically

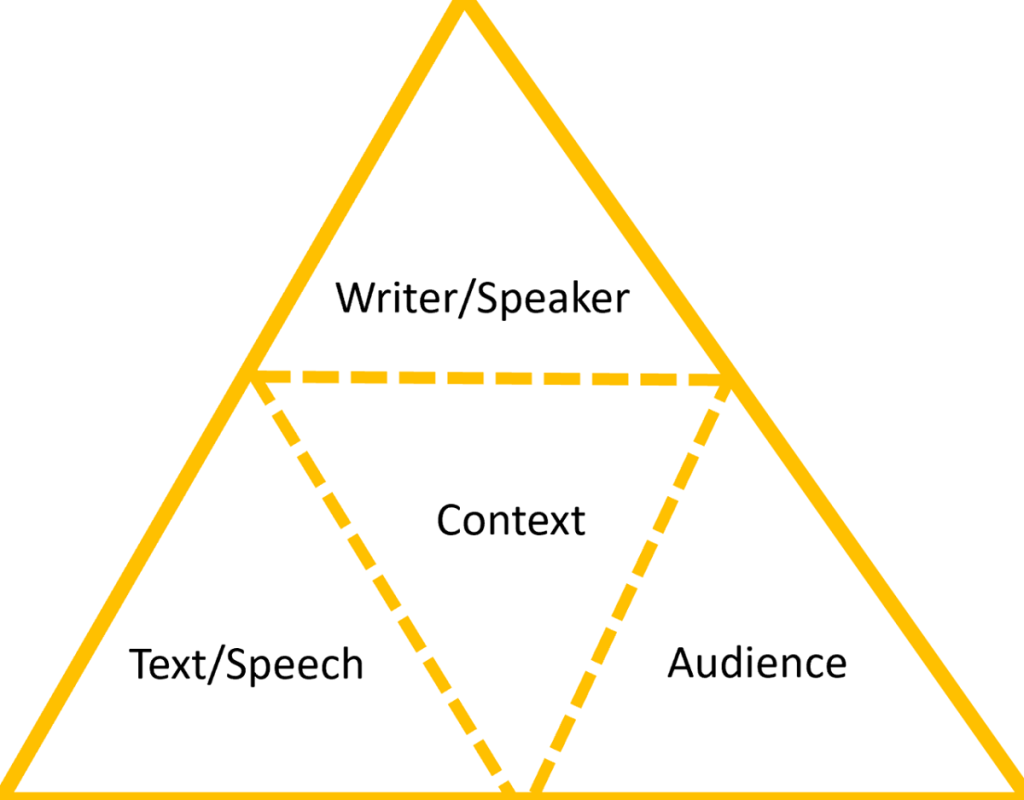

6.4 Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos Defined

Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel

Rhetoric, as the previous chapters have discussed, is the way that authors use and manipulate language in order to persuade an audience. Once we understand the rhetorical situation out of which a text is created (why it was written, for whom it was written, by whom it was written, how the medium in which it was written creates certain constraints, or perhaps freedoms of expression), we can look at how all of those contextual elements shape the author’s creation of the text.

We can look first at the classical rhetorical appeals, which are the three ways to classify authors’ intellectual, moral, and emotional approaches to getting the audience to have the reaction that the author hopes for.

Rhetorical Appeals

Rhetorical appeals refer to ethos, pathos, and logos. These are classical Greek terms, dating back to Aristotle, who is traditionally seen as the father of rhetoric. To be rhetorically effective (and thus persuasive), an author must engage the audience in a variety of compelling ways, which involves carefully choosing how to craft his or her argument so that the outcome, audience agreement with the argument or point, is achieved. Aristotle defined these modes of engagement and gave them the terms that we still use today: logos, pathos, and ethos.

Logos: Appeal to Logic

Logic. Reason. Rationality. Logos is brainy and intellectual, cool, calm, collected, objective.

When an author relies on logos, it means that he or she is using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact checked (using multiple sources) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

For example, if I were trying to convince my students to complete their homework, I might explain that I understand everyone is busy and they have other classes (non-biased), but the homework will help them get a better grade on their test (explanation). I could add to this explanation by providing statistics showing the number of students who failed and didn’t complete their homework versus the number of students who passed and did complete their homework (factual evidence).

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking , such as

- Comparison – a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic) and another, similar thing to help support your claim. It is important that the comparison is fair and valid – the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking – you argue that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim. Be careful with the latter – it can be difficult to predict that something “will” happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning – starting with a broad, general claim/example and using it to support a more specific point or claim

- Inductive reasoning – using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization

- Exemplification – use of many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point

- Elaboration – moving beyond just including a fact, but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact

- Coherent thought – maintaining a well organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around

Pathos: Appeal to Emotions

When an author relies on pathos, it means that he or she is trying to tap into the audience’s emotions to get them to agree with the author’s claim. An author using pathetic appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, or happiness. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies, or sad-looking kittens, and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money.

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic, the argument, or to the author. Emotions can make us vulnerable, and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that his or her argument is a compelling one.

Pathetic appeals might include