Research to Action

The Global Guide to Research Impact

Social Media

Framing challenges

Synthetic literature reviews: An introduction

By Steve Wallis and Bernadette Wright 26/05/2020

Whether you are writing a funding proposal or an academic paper, you will most likely be required to start with a literature review of some kind. Despite (or because of) the work involved, a literature review is a great opportunity to showcase your knowledge on a topic. In this post, we’re going to take it one step further. We’re going to tell you a very practical approach to conducting literature reviews that allows you to show that you are advancing scientific knowledge before your project even begins. Also – and this is no small bonus – this approach lets you show how your literature review will lead to a more successful project.

Literature review – start with the basics

A literature review helps you shape effective solutions to the problems you (and your organisation) are facing. A literature review also helps you demonstrate the value of your activities. You can show how much you add to the process before you spend any money collecting new data. Finally, your literature review helps you avoid reinventing the wheel by showing you what relevant research already exists, so that you can target your new research more efficiently and more effectively.

We all want to conduct good research and have a meaningful impact on people’s lives. To do this, a literature review is a critical step. For funders, a literature review is especially important because it shows how much useful knowledge the writer already has.

Past methods of literature reviews tend to be focused on ‘muscle power’, that is spending more time and more effort to review more papers and adhering more closely to accepted standards. Examples of standards for conducting literature reviews include the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions and the guidelines for assessing the quality and applicability of systematic reviews developed by the Task Force on Systematic Review and Guidelines . Given the untold millions of papers in many disciplines, even a large literature review that adheres to the best guidelines does little to move us toward integrated knowledge in and across disciplines.

In short, we need we need to work smarter, not harder!

Synthetic literature reviews

One approach that can provide more benefit is the synthetic literature review. Synthetic meaning synthesised or integrated, not artificial. Rather than explaining and reflecting on the results of previous studies (as is typically done in literature reviews), a synthetic literature review strives to create a new and more useful theoretical perspective by rigorously integrating the results of previous studies.

Many people find the process of synthesis difficult, elusive, or mysterious. When presenting their views and making recommendations for research, they tend to fall back on intuition (which is neither harder nor smarter).

After defining your research topic (‘poverty’ for example), the next step is to search the literature for existing theories or models of poverty that have been developed from research. You can use Google Scholar or your institutional database, or the assistance of a research librarian. A broad topic such as ‘poverty’, however, will lead you to millions of articles. You’ll narrow that field by focusing more closely on your topic and adding search terms. For example, you might be more interested in poverty among Latino communities in central California. You might also focus your search according to the date of the study (often, but not always, more recent results are preferred), or by geographic location. Continue refining and focusing your search until you have a workable number of papers (depending on your available time and resources). You might also take this time to throw out the papers that seem to be less relevant.

Skim those papers to be sure that they are really relevant to your topic. Once you have chosen a workable number of relevant papers, it is time to start integrating them.

Next, sort them according to the quality of their data.

Next, read the theory presented in each paper and create a diagram of the theory. The theory may be found in a section called ‘theory’ or sometimes in the ‘introduction’. For research papers, that presented theory may have changed during the research process, so you should look for the theory in the ‘findings’, ‘results’, or ‘discussion’ sections.

That diagram should include all relevant concepts from the theory and show the causal connections between the concepts that have been supported by research (some papers will present two theories, one before and one after the research – use the second one – only the hypotheses that have been supported by the research).

For a couple of brief and partial example from a recent interdisciplinary research paper, one theory of poverty might say ‘Having more education will help people to stay out of poverty’, while another might say ‘The more that the economy develops, the less poverty there will be’.

We then use those statements to create a diagram as we have in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Two (simple, partial) theories of poverty. (We like to use dashed lines to indicate ’causes less’, and solid lines to indicate ’causes more’)

When you have completed a diagram for each theory, the next step is to synthesise (integrate) them where the concepts are the same (or substantively similar) between two or more theories. With causal diagrams such as these, the process of synthesis becomes pretty direct. We simply combine the two (or more) theories to create a synthesised theory, such as in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Two theories synthesised where they overlap (in this case theories of poverty)

Much like a road map, a causal diagram of a theory with more concepts and more connecting arrows is more useful for navigation. You can show that your literature review is better than previous reviews by showing that you have taken a number of fragmented theories (as in Figure 1) and synthesised them to create a more coherent theory (as in Figure 2).

To go a step further, you may use Integrative Propositional Analysis (IPA) to quantify the extent to which your research has improved the structure and potential usefulness of your knowledge through the synthesis. Another source is our new book from Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation (see especially Chapter 5). (For the basics, you can look at Chapter One for free on the publisher’s site by clicking on the ‘Preview’ tab here. )

Once you become comfortable with the process, you will certainly be working ‘smarter’ and showcasing your knowledge to funders!

Contribute Write a blog post, post a job or event, recommend a resource

Partner with Us Are you an institution looking to increase your impact?

Most Recent Posts

- Keeping up with the AI revolution

- Four lessons for improving Theory of Change use in research uptake M&E

- Empowering Climate Action: The Essential Role of Knowledge Brokering

- Memorandum of Understanding-a Communication Tool

- Re-thinking impact: the role of context, voice, and power

This Week's Most Read

- What do we mean by ‘impact’?

- How to write actionable policy recommendations

- 12ft Ladder: Making research accessible

- How to develop input, activity, output, outcome and impact indicators

- Gap analysis for literature reviews and advancing useful knowledge

- Outcome Mapping: A Basic Introduction

- AEN Evidence 23 – Online Access Registration now open!

- Policymaker, policy maker, or policy-maker?

- Key questions to ask when putting together a Theory of Change for Research Uptake (Part 1 of 2)

- Framework for impact evaluation in grant applications

Research To Action (R2A) is a learning platform for anyone interested in maximising the impact of research and capturing evidence of impact.

The site publishes practical resources on a range of topics including research uptake, communications, policy influence and monitoring and evaluation. It captures the experiences of practitioners and researchers working on these topics and facilitates conversations between this global community through a range of social media platforms.

R2A is produced by a small editorial team, led by CommsConsult . We welcome suggestions for and contributions to the site.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Our contributors

Browse all authors

Friends and partners

- Global Development Network (GDN)

- Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

- On Think Tanks

- Politics & Ideas

- Research for Development (R4D)

- Research Impact

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Literature Reviews: Systematic, Scoping, Integrative

Characteristics of review types, choosing a review type.

Steps in a Systematic/Scoping/Integrative Review

Confirming the Knowledge Gap

Standards and reporting guidelines.

- Creating a Search Strategy

- Limits and Inclusion Criteria

- Review Protocols

- Elements of a Systematic Review

- Review Tools and Applications

Additional Resources

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis Process outlines for multiple types of evidence reviews. A great source to cite in your methods section.

- PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Guidance for authors and peer reviewers on best practices in reporting for evidence reviews. Includes extensions for different types of reviews, including scoping reviews

Not sure which review type is right for your research question? Check out the links below for help choosing.

- What Review is Right for You? v2 14 page PDF survey to help you determine which review type might work best for you. Very thorough!

- Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Creating an effective search for a systematic review means walking a tightrope between comprehensiveness and managability. You want to try to include all of the studies that could possibly be relevant while simultaneously getting your search results down to a number of articles that you can realistically review.

The Basic Process:

- Develop a research question.

- Search databases to see if a review has already been published on your topic.

- Select the type of review (systematic, scoping, integrative)

- Select databases.

- Select grey literature sources (if applicable). Read this article for helpful suggestions on systematically searching for grey literature.

- Formulate an initial search for one of your selected databases. For tips on searching, consult our Mastering Keyword Searching guide.

- Review results from initial search, scanning titles, abstracts, and subject headings to identify additional terms. You may also want to use the subject heading database you can find within each database.

- Run the search again. Continue to add relevant terms and adjust the scope of your question (which may require eliminating terms) until results are a reasonable size and predominantly relevant to your question.

- When you think your search is nearly final, gather 2-3 of your most relevant articles and test their reference lists against your search results. If your search contains a large majority of the relevant articles from those reference lists, your have your final search (remember no search is ever perfect, and you will nearly always add articles you find via reference lists, recommendations, etc. that did not appear in your search results).

- Translate your search to your other databases. Generally your keywords will stay the same across databases, but you will most likely need to adjust your subject headings, because those can vary from database to database.

- Ask a librarian to peer review your search. Try the PRESS checklist .

- Develop inclusion and exclusion criteria in preparation for reviewing articles (this step may come later for a scoping review)

- Write a protocol .

- Database name (be as specific as possible, including the full title, especially for databases that are offered in multiple formats, e.g. Ovid Medline) and dates of coverage.

- Search terms, including indicating which are subject headings and which are keywords plus any limitations to where the keywords were search if relevant.

- Database limits/filters applied to the results (e.g. publication year, language, etc.).

- Date of your search.

- Number of results.

- Begin title/abstract screening. Two reviewers for each item is best practice.

- Begin full-text review of the articles still remaining. Again, two reviewers for each item is best practice.

- Conduct citation mining for the articles that make it through full-text review. That means looking at reference lists (backwards searching) and searching for articles that cite back to the article you have (forward searching). You might also consider setting aside all of the systematic and scoping reviews that came up with your search (generally those are excluded from your review) and mining their reference lists as well. Repeat the title/abstract screening and full-text reviews for the articles identified through citation mining.

- Check all articles that made it through the full-text review for retractions, and remove any articles that have been retracted.

- If doing a systematic review, conduct a critical appraisal of included articles (aka Risk of Bias Assessment).

- Covidence. (2024). A practical guide to data extraction for intervention systematic reviews .

- Pollock et al. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews . JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21 (3), 520-532.

- Prepare your manuscript (for information on writing each section of your manuscript, see our guide to Writing up Your Own Research ).

Before beginning your review, you need to be sure that no other reviews with the same research question as yours already exist or are in progress. This is easily done by searching research databases and protocol registries.

Databases to Check

Protocol Registries

- PROSPERO PROSPERO accepts registrations for systematic reviews, rapid reviews and umbrella reviews. PROSPERO does not accept scoping reviews or literature scans. Sibling PROSPERO sites register systematic reviews of human studies and systematic reviews of animal studies.

It is a good idea to familiarize yourself with the standards and reporting guidelines for the type of review you are planning to do. Following the standards/guidelines as you plan and execute your review will help ensure that you minimize bias and maximize your chances of getting published.

Systematic Reviews

- PRISMA Statement The PRISMA statement is currently the standards and guidelines of choice for systematic reviews. At the link you will find the statement as well as explanations of each element, a checklist of elements, a PRISMA flow diagram template, and more.

- IOM Finding What Works in Healthcare: Standards for Systematic Reviews Standards from the National Academy of Medicine and National Academies Press. The free download link is all the way over on the right.

Scoping Reviews

- PRISMA-SCR Extension for Scoping Reviews A PRISMA statement, explanation and checklist specifically for scoping reviews.

- Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews While the PRISMA-SCR provides reporting guidelines, these guidelines from JBI are for how to actually plan and do your review. This is the explanation for updates made to the manual linked below. You can skip this article and go directly to the JBI manual if you prefer.

Integrative Reviews

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52 (5), 546–553. This article is the current standard for designing an integrative review. more... less... https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Tavares de Souza, M., Dias da Silva, M., & de Carvalho, R. (2010). Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein, 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134

- Next: Creating a Search Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 6:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.massgeneral.org/reviews

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

A lexical and syntactic study of research article titles in Library Science and Scientometrics

- Published: 16 May 2021

- Volume 126 , pages 6041–6058, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Junli Diao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9603-8278 1

745 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

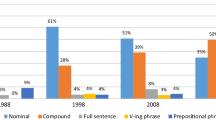

Title of a research article is an abstract of the abstract. Titles play a decisive role in convincing readers at first sight whether articles are worth reading or not. Not only do research article titles show how carefully words are chosen by authors, but also reflect disciplinary differences in terms of title words and structure between hard sciences and soft sciences. This study examined the lexical density and syntactic structure of 690 research article titles chosen from five Library Science and Scientometrics journals, aiming to reveal disciplinary differences. The result suggested both Library Science and Scientometrics have almost the same title length and the prevalent usage of Nominal Phrase (NP) to govern the title structure. The result also stated some disciplinary differences: Library Science demonstrates more punctuation complexity, particularly a greater frequency in using colons; but Scientometrics shows more involvement of words related to research methods, which is an indicator to papers’ scientific value, and more usage of declarative Full Sentence (FS) structure, which were mostly discovered in the research articles in hard sciences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A diachronic comparative study of research article titles in linguistics and literature journals

Xuechun Xiang & Jing Li

Titles in research articles and doctoral dissertations: cross-disciplinary and cross-generic perspectives

Jialiang Hao

Scientometric analysis of social science and science disciplines in a developing nation: a case study of Pakistan in the last decade

Malik Muhammad Saad Missen, Sajeeha Qureshi, … V. B. Surya Prasath

Ávila-Argüelles, R., Calvo, H., Gelbukh, A., & Godoy-Calderón, S. (2010). Assigning Library of Congress Classification codes to books based only on their titles. Informatica, 34 , 77–84

Google Scholar

Adams, W. M. (1967). Relationship of keywords in titles to references cited. American Documentation, 18 , 26–32

Article Google Scholar

Anthony, L. (2001). Characteristic features of research article titles in computer science. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44 , 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1109/47.946464

Appiah, K. R., Ankomah, C., Osei, H. Y., & Hattoh-Ahiaduvor, T. (2019). Structural organisation of research article titles: A comparative study of titles of business, gynaecology and law. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 10 (3), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.10n.3p.145

Archibald, A. J. B. (2017). A linguistic analysis of conference titles in Applied Linguistics. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching & Research, 5 (18), 11–25

Arsenault, C., & Ménard, E. (2011). Searching titles with initial articles in library catalogs: A case study and search behavior analysis. Library Resources & Technical Services, 51 , 190–203. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.51n3.190

Baicchi, A. (2003). Relational complexity of titles and texts: A semiotic taxonomy. In L. Merlini Barbaresi (Ed.), Complexity in language and text. (pp. 319–341). Edizione Plus-Universidad de Pisa.

Berkenkotter, C., & Huckin, T. N. (1995). Genre knowledge in disciplinary communication: Cognition, culture, power . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Busch-Lauer, I. A. (2000). Titles of English and German research papers in Medicine and Linguistics. Analysing Professional Genres, 74 , 77–94

Buxton, A. B., & Meadows, A. J. (1977). The variation in the information content of titles of research papers with time and discipline. Journal of Documentation, 33 , 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026633

Casson, L. (2001). Libraries in the ancient world . Yale University Press.

Cheng, S. W., Kuo, C.-W., & Kuo, C.-H. (2012). Research article titles in Applied Linguistics. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 6 (1), A1–A14

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Diers, D., & Downs, F. S. (1994). Colonizing: A measurement of the development of a profession. Nursing Research, 43 , 316–318

Dillon, J. T. (1981). The emergence of the colon: An empirical correlate of scholarship. American Psychologist, 36 , 879–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.8.879

Dillon, J. T. (1982). In pursuit of the colon: A century of scholarly progress: 1880–1980. The Journal of Higher Education, 53 , 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1982.11780427

Fortanet, I., Coll, J. F., Palmer, J. C., & Posteguillo, S. (1997). The writing of titles in academic research articles. In R. M. Chamorro & A. R. Navarrete (Eds.), Lenguas aplicadas a las ciencias y la tecnología. Aproximaciones. (pp. 155–158). Universidada de Extremadura, Servicio de Publicaciones.

Fortanet, I., Posteguillo, S., Coll, J. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1998). Linguistic analysis of research articles: Disciplinary variations. In I. Vazquez & I. Camilleu (Eds.), Perspectivas praguietices en linguistica aplicada, zaragoza. (pp. 443–447). Anubar Ediciones.

Gómez, I. F., Gómez, S. P., García, J. F. C., & Silveira, J. C. P. (1998). Linguistic analysis of research article titles: Disciplinary variations. In I. V. Orta & I. G. Galve (Eds.), Perspectivas pragmáticas en lingüística aplicada. (pp. 443–448). Anubar Ediciones.

Gesuato, S. (2008). Encoding of information in titles: Academic practices across four genres in linguistics. In C. Taylor (Ed.), Ecolingua: The role of e-corpora in translation and language learning. (pp. 127–157). EUT.

Goodman, R. A., Thacker, S. B., & Siegel, P. Z. (2001). What’s in a title? A descriptive study of article titles in peer-reviewed medical journals. Science Editor, 24 , 75–78

Haggan, M. (2004). Research paper titles in literature, linguistics and science: Dimensions of attraction. Journal of Pragmatics, 36 , 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(03)00090-0

Hartley, J. (2007). Planning that title: Practices and preferences for titles with colons in academic articles. Library & Information Science Research, 29 , 553–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.05.002

Jahoda, G., & Stursa, M. L. (1969). A comparison of a keyword from title index with a single access point per document alphabetic subject index. American Documentation, 20 , 377–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630200422

Lewison, G., & Hartley, J. (2005). What’s in a title? Numbers of words and the presence of colons. Scientometrics, 63 , 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-005-0216-0

Maiti, D. C., & Dutta, B. (2013). Comparative study between words in titles and keywords of some articles on knowledge organisation. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 33 , 498–508

Michelson, G. (1994). Use of colons in titles and journal status in industrial relations journals. Psychological Reports, 74 , 657–658. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.74.2.657

Milojević, S. (2017). The length and semantic structure of article titles—Evolving disciplinary practices and correlations with impact. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 2 (2), 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2017.00002

Milojević, S., Sugimoto, C. R., Yan, E., & Ding, Y. (2011). The cognitive structure of library and information science: Analysis of article title words. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62 , 1933–1953. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21602

Moattarian, A., & Alibabaee, A. (2015). Syntactic structures in research article titles from three different disciplines: Applied linguistics, Civil Engineering, and Dentistry. Journal of Teaching Language Skills, 34 , 27–50

Morales, O. A., Perdomo, B., Cassany, D., Tovar, R. M., & Izarra, É. (2020). Linguistic structures and functions of thesis and dissertation titles in Dentistry. Lebende Sprachen, 65 , 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2020-0003

Nagano, R. L. (2015). Research article titles and disciplinary conventions: A corpus study of eight disciplines. Journal of Academic Writing, 5 (1), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v5i1.168

O’Connor, J. (1964). Correlation of indexing headings and title words in three medical indexing systems. American Documentation, 15 , 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090150207

Perry, J. A. (1985). The Dillion hypothesis of titular colonicity: An empirical test from the ecological sciences. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 36 , 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630360405

Sahragard, R., & Meihami, H. (2016). A diachronic study on the information provided by the research titles of Applied Linguistics journals. Scientometrics, 108 , 1315–1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2049-4

Salager-Meyer, F., Ariza, M. A. A., & Briceño, M. L. (2013). Titling and authorship practices in medical case reports: A diachronic study. Communication & Medicine, 10 (1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197775

Soler, V. (2007). Writing titles in science: An exploratory study. English for Specific Purposes, 26 , 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.001

Soler, V. (2011). Comparative and contrastive observations on scientific titles written in English and Spanish. English for Specific Purposes, 30 , 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2010.09.002

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research setting . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slougui, D. (2018). Dissertation titles in EFL and UK-based contexts: How much do they differ? ASp, 74 , 135–161. https://doi.org/10.4000/asp.5466

Trosborg, A. (2000). Introduction. In A. Trosborg & J. Benjamins (Eds.), Analysing professional genres. (pp. vii–xvi). ProQuest Ebook Central.

Chapter Google Scholar

Wang, Y., & Bai, Y. (2007). A corpus-based syntactic study of medical research article titles. System, 35 , 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.01.005

Xie, S. (2020). English research article titles: Cultural and disciplinary perspectives. SAGE Open, 10 (2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020933614

Yakhontova, T. (2002). Titles of conference presentation abstracts: A cross-cultural perspective . Retrieved on October 9, 2020 from, https://www.academia.edu/36296603/Titles_of_conference_presentations_abstracts_A_cross_cultural_perspective .

Yitzhaki, M. (1997). Variation in informativity of titles of research papers in selected humanities journals: A comparative study. Scientometrics, 38 , 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02457410

Ziebland, S., & Pope, C. (1995, September/October) Use of the colon in titles of British Medical Sociology Conference papers, 1970 to 1993. Annals of Improbable Research , 7–9.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

York College Library, The City University of New York, New York, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Junli Diao .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Diao, J. A lexical and syntactic study of research article titles in Library Science and Scientometrics. Scientometrics 126 , 6041–6058 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04018-6

Download citation

Received : 27 December 2020

Accepted : 26 April 2021

Published : 16 May 2021

Issue Date : July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04018-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Library Science

- Scientometrics

- Lexical density

- Syntactic structure

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Semantic interoperability in health records standards: a systematic literature review

Blanda helena de mello.

Software Innovation Laboratory, SOFTWARELAB Universidade Do Vale Do Rio Dos Sinos - Unisinos, São Leopoldo, Brazil

Sandro José Rigo

Cristiano andré da costa, rodrigo da rosa righi, bruna donida, marta rosecler bez, luana carina schunke, associated data.

Not applicable.

The integration and exchange of information among health organizations and system providers are currently regarded as a challenge. Each organization usually has an internal ecosystem and a proprietary way to store electronic health records of the patient’s history. Recent research explores the advantages of an integrated ecosystem by exchanging information between the different inpatient care actors. Many efforts seek quality in health care, economy, and sustainability in process management. Some examples are reducing medical errors, disease control and monitoring, individualized patient care, and avoiding duplicate and fragmented entries in the electronic medical record. Likewise, some studies showed technologies to achieve this goal effectively and efficiently, with the ability to interoperate data, allowing the interpretation and use of health information. To that end, semantic interoperability aims to share data among all the sectors in the organization, clinicians, nurses, lab, the entire hospital. Therefore, avoiding data silos and keep data regardless of vendors, to exchange the information across organizational boundaries. This study presents a comprehensive systematic literature review of semantic interoperability in electronic health records. We searched seven databases of articles published between 2010 to September 2020. We showed the most chosen scenarios, technologies, and tools employed to solve interoperability problems, and we propose a taxonomy around semantic interoperability in health records. Also, we presented the main approaches to solve the exchange problem of legacy and heterogeneous data across healthcare organizations.

Introduction

A semantically integrated health system allows sharing data among organizations and their internal ecosystem without missing the meaning. The search for semantic interoperability in health records and different clinical annotations is one of the main challenges for systems, being a constant objective of studies in the last years, such as [ 1 – 3 ]. Implementing interoperability can allow healthcare professionals to manage the complete electronic patient record, regardless of the organization that generated the clinical session entries [ 4 ]. As reinforced by Kim and Joshi [ 5 ], health record interoperability became a crucial issue in the healthcare scenario, especially in the COVID-19 pandemic, to further disease control.

Semantic interoperability (SI) aims to share data among organizations or systems and ensure they understand and interpret data regardless of who is involved, using domain concepts, context knowledge, and formal data representation [ 6 ]. On the other hand, semantic interoperability also can be understood by taking a step back: semantics is the study of meaning, focused on the relationship between people and their words, which is essential to help people understand each other despite different experiences or viewpoints [ 7 ]. Interoperability is the ability of two or more systems to work together, regardless of its different interfaces, platforms, and technologies adopted [ 8 ].

The HIMSS [ 9 ] 1 – a global advisor supporting the transformation of the health ecosystem, with 480 provider organizations and more than 450 non-profit partners – had designed defined in three levels the interoperability technology: 1) Foundation; 2) Structural and 3) Semantic. The Foundational level defined requirements to connect different systems and securely exchange data. The Structural level defines the format, syntax, and data to interpret at the field level; the Semantic level allows one to work with terminologies, vocabularies, standardized values publicly defined and makes a complete understanding meaning.

According to Gancel et al.. [ 10 ], there are many challenges to overcome to achieve an electronic health record, such as understanding the wide variety of terms, addressing disambiguation, identifying and updating the concepts. That scenario is reinforced by [ 11 , 12 ], where the authors had discussed the three fundamental levels of interoperability to improve the workflows across health information systems to allow true interoperability. To the healthcare area, interoperability means different systems, applications, and devices share, use, and process data from any place and keep the real meaning.

Using standards allows sharing data between clinicians, lab, hospital and, pharmacies regardless of vendor, achieving semantic interoperability. In other words, interoperability allows health information systems to work across organizational boundaries.

From the above, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- discussion about the state of the art of semantic interoperability in health records.

- introduce a taxonomy in semantic interoperability in electronic health records.

- recognize the main approaches commonly used to achieve semantic interoperability in EHR (Electronic Health Record) systems.

- expose the grown adoption using semantic web technologies combining international standards to solve semantic interoperability problems.

Thus, this systematic review aims to answer the following central question: what is the state of the art of semantic interoperability in health records in the sense of approaches and international health standards?

We organized the systematic review as follows. Section 0 presents a background of semantic interoperability and electronic health records. Follow, Sect. 0 shows the protocol defined, describing the inclusion/exclusion criteria and the quality assessment. Section 0 presents the results of the conducted review and the research questions answered, and Sect. 0 discusses some open questions and the main approaches used by the selected studies. Lastly, we discuss future directions to work in Sect. 0.

According to ISO/TS18308 [ 13 ], an EHR aims to integrate health records in a processable format, securely storing and communicating. Using an information model commonly accepted to exchange data, making it accessible to authorized users. That aims to ensure the patient’s life-long integrated healthcare, efficiently with high-quality and security. The EHR structure holds the patient’s health status, and that format must be processed digitally [ 14 ], maintaining patients’ data throughout their life and stored accurately in a repository.

There are different data formats in EHR systems, such as structured data and non-structured textual data. EHR covers an extensive part of the medical histories, includes more patients’ complete information and potential risk factors. In addition, it maintains patient health records and supports the provision of daily care in hospitals and primary care clinics [ 15 ]. Furthermore, it allows the reuse of patient data for many purposes, including managing individual patients, medical and health services research, and management of health care facilities [ 16 ].

Adopting an EHR is essential to manage healthcare and exchange data between healthcare organizations. An EHR allows communication among clinicians, nurses, laboratories, and hospitals despite different systems. Sharing data between health organizations and health agents must foster the correct interpretation, with the same precision and meaning adopted from the sender [ 17 ], achieving semantic interoperability. Therefore, semantic interoperability is the ability to share data between systems and ensure understanding at the concept’s level of the domain [ 13 ].

Different health standards aim to enable data sharing among healthcare organizations. However, the adoption of standards still presents several challenges to achieving interoperability at the semantic level. The semantic web focuses on sharing data, integration, and reuse through ontologies, linked open data, and knowledge graphs to ensure the correct meaning of shared data. The semantic web is also known as one of the fundamental technologies to achieve semantic interoperability in health information systems [ 4 ], often using ontologies, a well-established technology to support knowledge-intensive tasks related to EHR systems [ 3 ].

Related work

Recently, the demand for systems that allow data interoperability at a semantic level has been an object of interest, mainly in health system providers. Different studies explore approaches to solving interoperability problems. However, there are difficulties in adopting health standards and tools to adequate data representation (ontologies, databases, clinical models) that ensure healthcare professionals efficiently manage the data.

The authors in [ 18 ] discuss interoperability in electronic health records from the management and business perspective. In this way, they highlight how data integration and exchange across organizational boundaries can improve quality of care, work processes, and effectiveness to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Also, the authors had shown how related healthcare with other areas such as Telemedicine, Big Data, and Business Intelligence. On the technology side, it helps eliminate rework, reduce errors, and promote individualized patient care. On the citizens’ side, it highlighted the support to create the primary public health initiatives, control, monitor diseases, reduce costs, and increase the effectiveness.

On the other hand, [ 19 , 20 ] analyzed technological aspects regarding health integration, interoperability, and data exchange. The first work describes the advantages of implementing integrated data repositories, a clinical data warehouse that allows clinical research, specialized analysis, and advanced data processing. The second paper proposes a transnational model integrating health records. The study suggests adopting a widely used health standard called HL7 FHIR, 2 vocabularies, and terminologies.

The systematic review [ 21 ] discusses the strong trend in adopting standards. The authors showed interest in analyzing the literature according to ontologies, specifically fuzzy ontology (Fuzzy ontology). The study presents a comprehensive background to context for the leading health standards and their different structures, highlighting characteristics they may have in common. The article also named the adopted standards using the “e-Health Standard” term, whereas we keep the broad term as a health standard. Also, the authors had highlighted trends of semantic interoperability in four categories that contribute to identifying challenges and research opportunities: a) frameworks to solve SI problems, b) using ontologies to achieve interoperability issues, c) standards in an Interoperable EHR, d) barriers and the heterogeneous problem EHR semantic interoperability.

Furthermore, the studies developed by [ 20 , 21 ] richly exposed the growth and interest of the healthcare sector in using standards for electronic medical records, breaking organizational barriers, and achieving interoperability among healthcare providers. Given this scenario, we conduct this review by scrutinizing the evolutions in adopting standards in recent years and the tools that eventually make up the environment for a semantically interoperable EHR.

Therefore, we consider it more coherent with the selected studies to observe the ecosystem involved in the construction and development of an EHR. Furthermore, understanding how secondary artifacts – semantic web tools, databases, terminologies – interact and impact project definition. Besides the standards and semantic web tools, we highlight ontologies not exclusively used to represent raw data but to represent clinical model structures.

Material and methods

This section describes the protocol used for the systematic literature review and shows the research questions designed to extract the information of interest from the selected studies. The research strategy for filtering and selecting the studies involved the adoption of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, we show aspects of the quality assessment for the selected articles, later applied to answer the research questions.

Study design

The protocol followed the steps from previous works of [ 22 , 23 ] and aimed to map relevant and recent research in semantic interoperability. A systematic literature review is a research method that allows the identification, evaluation, and interpretation of the studies without bias in the process.

- Research questions: introduce the research questions investigated.

- Search strategy: outline the strategy and libraries explored to collect data.

- Article selection: explain the criteria for selecting the studies.

- Quality assessment: describe the quality assessment applied to the selected studies.

- Data extraction: compare the selected studies and research questions.

Research questions

The research questions represent a fundamental part of the systematic review [ 22 ], as they allow directing the research and extracting information as needed, as they follow the topic of interest. Table Table1 1 presents the research questions of interest in the systematic review. There are two sets of questions, the first global context questions, including an overview of all studies. The latter are specific questions to answer about each article, as shown below.

Research questions to extract information of interest from the articles selected in this review

Search strategy

The search strategy aims to find studies to answer the research questions through the definition of keywords and the scope of the research. The correct selection of keywords ensures adequate research results on the databases. As guided by [ 22 ], we used the five PICOC questions (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Context) to define the scope of the research, as explained below.

Population involves keywords, related terms, and variants around the interest area. We used “semantic interoperability” as the central term in the search string shown in Frame 1. In the Intervention, being “semantic interoperability” a general term, we used some other keywords to filter: health record, medical record, patient record, and hospital record, aiming to allow filtering semantic interoperability standards applied in health records. Comparison, on this research, aims to find different health standards allowing semantic interoperability in health records. The Outcomes determine relevant studies that can answer the research questions.

Also, we evaluated studies that explore the limitations of applying health standards. We define Context as the concern to identify the different application scenarios and data used on the proposal. This research focused on selecting studies concerned with proposing solutions to semantic interoperability problems in health records. In addition, we notice that different kinds of data come from the real world, and most come from a controlled environment (case study) or simulated data.

The research string formatted as shown in Frame 1 demonstrates the mandatory terms, such as semantic interoperability and his acronyms; health record and his acronyms; the term standard. At the selection step, the terms applied aim to filter the articles by title, abstract, and keywords.

Frame 1 This frame shows the search string defined to research.

Article selection

Next, the studies with neither a key term addressed nor a PICOC definition aligned, called impurities, are removed. Finally, qualify our results, and for that, we defined the exclusion criteria based on the research question:

- Exclusion criteria 1: the article is not in the range (search date 2010 to September 24, 2020).

- Exclusion criteria 2: the article does not address semantic interoperability or related acronyms (population criteria I).

- Exclusion criteria 3: the article does not address the health record, medical record, patient record, hospital record, and related acronyms (intervention criteria II).

- Exclusion criteria 4: the article does not address standard or related acronyms (comparison criteria III).

- Exclusion criteria 5: the article has less than six pages.

- Exclusion criteria 6: impurities articles (e.g., duplicate papers and non-English studies).

Quality assessment

The quality assessment consists of a filter focused on the quality and relevance of studies related to the interest area. The quality assessment ensures that selected articles have a relevant impact in the research area. As a criterion to filter the rest studies, we defined the h5-index score, equal to or higher than 28. If the article passes the cutoff, it can be accepted in this review..

Data extraction

After selecting articles to satisfy the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the quality assessment, the data extraction step occurs. The other articles represent the corpus qualified for full reading and analysis. The research questions target to extract information from selected studies according to the topic of interest, and data extraction aims to correlate the area of interest with the defined research questions. The studies propose different solutions to the research problem presented: what health standards approaches can solve semantic interoperability problems in health records? The questions have a limited response context to avoid bias, to respond objectively.

The methodology to answer the research questions proposes to extract the results as presented in Table Table2, 2 , where the General Question (GQ) and Specific Question (SQ) have an expected location to search for data.

Follows we shows the quality assessment of article and related questions

Results and discussion

The discussion of these different results extracted through the research questions defined, such as shown in Table Table1, 1 , allows understanding the semantic interoperability scenario and the solutions usually applied in this scenario.

Conducting the search strategy

We chose seven different research bases to cover studies in the health and technology field, such as ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore Library, Science Direct, Springer Link. Moreover, we added Google Scholar to cover studies outside those bases. Our criterion was the relevance of these databases concerning the health and information technology literature. The search step in the databases, as mentioned above, aimed to index the search for studies published in the last ten years. Each database presents a way of formatting the survey, which we respect and modify to suit, but we kept all the mandatory terms defined in the PICOC strategy.

Finally, after applying the queries to the search bases, we had 6,032 articles. The initial filter aims to remove patents and citations, non-English studies, which resulted in around 783, roughly because some patents also appeared as citations.

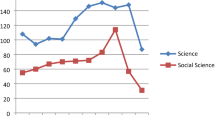

As shown in Fig. 1 , by year, the published articles in this area have been an interest constant in recent years. For this systematic review, the cutoff was September 22nd, 2020.

This graph presents, distributed by year of publication, the corpus of articles published during the range 2010 to September 2020

Figure 2 shows the selection steps, removing impurity studies unrelated to the area of interest. Usually, these impurities studies had references related to the research area or citations of related works, however, without directly informing the area of interest. In addition, articles with less than six pages and no abstract, about 735 impurities, were excluded. We removed non-primary studies, such as editorials, chapters, thesis, reviews, and reports, approximately 1195 studies.

The figure presents the entire selection process of the studies across the inclusion/exclusion criteria and quality assessment to conduct this systematic review

Then, we applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the PICOC strategy: semantic interoperability, medical record (variants such as health record, medical record, patient record, hospital record), and standard. Finally, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied to the remaining studies to filter articles directly related to the research topic, totaling 2,288 excluded studies. The filters allow selecting studies according to defined terms.

The last step had two parts; first, we filtered the studies by main interest area and evaluated the remaining corpus about its objectives. Many studies satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria but differed from the review’s interest topics. Thus, the quality assessment, the last step of the protocol, provides a cutoff parameter, where we look for studies published in relevant journals for the area of interest. Among these, we selected the highlighted studies. For this, we use the h5-index metric, which quantifies the relevance of newspapers and conferences in the last five years, a Google metric and works with the highest number H [ 24 ]. Some studies that presented relevant discussions but did not appear in this index were separated to contribute to our discussion section.

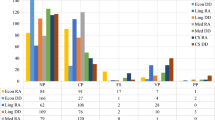

In the final selection, some bases showed a predominance of accepted articles. For example, ScienceDirect with eight studies followed for PubMed Medline with seven and Google Scholar with six studies. Next was SpringerLink with four and IEEE Explore with two, while ACM Digital Library and Web of Science had one from each research base. Figure 3 present the final corpus articles accepted in this systematic review.

This graph presents the articles accepted after the selection process, showing the number of articles by published year

Figure 3 shows the accepted articles distributed by year. Table Table3 3 shows where each article was published (journal or congress), the number of articles per location, and the H5 index used in the quality assessment stage. Three times the journals had an above-average acceptance, a scenario explained by the applied area, which is related to the research question of this review. We highlight the International Journal of Medical Informatics, with five accepted studies, BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, and the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, with four accepted studies for each, a relevant number compared to the rest of the studies shown in Table Table3 3 below.

This graph presents the number of papers by year of publication after finishing the selection and filtering steps

The information extracted from the articles aims to answer the question of interest in the review and identify approaches and solutions developed that allow achieving semantic interoperability in health records. Table Table4 4 presents the final list of articles selected for this systematic review.

This table presents the first author and respective studies by year, relating the publisher and the kind of place it was published

Follows the analysis of the selected studies against the questions of interest, and each other answered individually.

SQ1 – What are the health standards adopted in the studies?

There is no consensus on a global standard for electronic health records, and the studies selected for this review reinforced this scenario. However, the extracted data shows a trend in the standard choice with a multilevel approach, as such openEHR, ISO/CEN 13,606, and HL7 formats. That dual model approach allows specialists in health and technology to perform in a joint work. Most of the studies had related advances toward a semantic dataset choosing standards to achieve semantic interoperability, as shown in Table Table5 5 .

Health standards used in the selected studies

http://www.clinicalelement.com/

https://www.dicomstandard.org/current

http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/

https://www.ihe.net/

http://www.en13606.org/information.html

https://www.openehr.org/