Research report guide: Definition, types, and tips

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

From successful product launches or software releases to planning major business decisions, research reports serve many vital functions. They can summarize evidence and deliver insights and recommendations to save companies time and resources. They can reveal the most value-adding actions a company should take.

However, poorly constructed reports can have the opposite effect! Taking the time to learn established research-reporting rules and approaches will equip you with in-demand skills. You’ll be able to capture and communicate information applicable to numerous situations and industries, adding another string to your resume bow.

- What are research reports?

A research report is a collection of contextual data, gathered through organized research, that provides new insights into a particular challenge (which, for this article, is business-related). Research reports are a time-tested method for distilling large amounts of data into a narrow band of focus.

Their effectiveness often hinges on whether the report provides:

Strong, well-researched evidence

Comprehensive analysis

Well-considered conclusions and recommendations

Though the topic possibilities are endless, an effective research report keeps a laser-like focus on the specific questions or objectives the researcher believes are key to achieving success. Many research reports begin as research proposals, which usually include the need for a report to capture the findings of the study and recommend a course of action.

A description of the research method used, e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or other

Statistical analysis

Causal (or explanatory) research (i.e., research identifying relationships between two variables)

Inductive research, also known as ‘theory-building’

Deductive research, such as that used to test theories

Action research, where the research is actively used to drive change

- Importance of a research report

Research reports can unify and direct a company's focus toward the most appropriate strategic action. Of course, spending resources on a report takes up some of the company's human and financial resources. Choosing when a report is called for is a matter of judgment and experience.

Some development models used heavily in the engineering world, such as Waterfall development, are notorious for over-relying on research reports. With Waterfall development, there is a linear progression through each step of a project, and each stage is precisely documented and reported on before moving to the next.

The pace of the business world is faster than the speed at which your authors can produce and disseminate reports. So how do companies strike the right balance between creating and acting on research reports?

The answer lies, again, in the report's defined objectives. By paring down your most pressing interests and those of your stakeholders, your research and reporting skills will be the lenses that keep your company's priorities in constant focus.

Honing your company's primary objectives can save significant amounts of time and align research and reporting efforts with ever-greater precision.

Some examples of well-designed research objectives are:

Proving whether or not a product or service meets customer expectations

Demonstrating the value of a service, product, or business process to your stakeholders and investors

Improving business decision-making when faced with a lack of time or other constraints

Clarifying the relationship between a critical cause and effect for problematic business processes

Prioritizing the development of a backlog of products or product features

Comparing business or production strategies

Evaluating past decisions and predicting future outcomes

- Features of a research report

Research reports generally require a research design phase, where the report author(s) determine the most important elements the report must contain.

Just as there are various kinds of research, there are many types of reports.

Here are the standard elements of almost any research-reporting format:

Report summary. A broad but comprehensive overview of what readers will learn in the full report. Summaries are usually no more than one or two paragraphs and address all key elements of the report. Think of the key takeaways your primary stakeholders will want to know if they don’t have time to read the full document.

Introduction. Include a brief background of the topic, the type of research, and the research sample. Consider the primary goal of the report, who is most affected, and how far along the company is in meeting its objectives.

Methods. A description of how the researcher carried out data collection, analysis, and final interpretations of the data. Include the reasons for choosing a particular method. The methods section should strike a balance between clearly presenting the approach taken to gather data and discussing how it is designed to achieve the report's objectives.

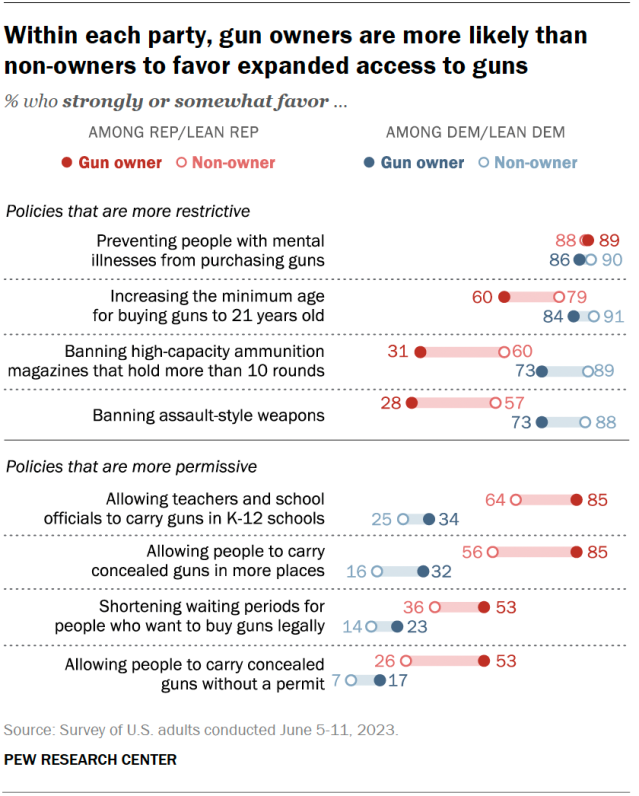

Data analysis. This section contains interpretations that lead readers through the results relevant to the report's thesis. If there were unexpected results, include here a discussion on why that might be. Charts, calculations, statistics, and other supporting information also belong here (or, if lengthy, as an appendix). This should be the most detailed section of the research report, with references for further study. Present the information in a logical order, whether chronologically or in order of importance to the report's objectives.

Conclusion. This should be written with sound reasoning, often containing useful recommendations. The conclusion must be backed by a continuous thread of logic throughout the report.

- How to write a research paper

With a clear outline and robust pool of research, a research paper can start to write itself, but what's a good way to start a research report?

Research report examples are often the quickest way to gain inspiration for your report. Look for the types of research reports most relevant to your industry and consider which makes the most sense for your data and goals.

The research report outline will help you organize the elements of your report. One of the most time-tested report outlines is the IMRaD structure:

Introduction

...and Discussion

Pay close attention to the most well-established research reporting format in your industry, and consider your tone and language from your audience's perspective. Learn the key terms inside and out; incorrect jargon could easily harm the perceived authority of your research paper.

Along with a foundation in high-quality research and razor-sharp analysis, the most effective research reports will also demonstrate well-developed:

Internal logic

Narrative flow

Conclusions and recommendations

Readability, striking a balance between simple phrasing and technical insight

How to gather research data for your report

The validity of research data is critical. Because the research phase usually occurs well before the writing phase, you normally have plenty of time to vet your data.

However, research reports could involve ongoing research, where report authors (sometimes the researchers themselves) write portions of the report alongside ongoing research.

One such research-report example would be an R&D department that knows its primary stakeholders are eager to learn about a lengthy work in progress and any potentially important outcomes.

However you choose to manage the research and reporting, your data must meet robust quality standards before you can rely on it. Vet any research with the following questions in mind:

Does it use statistically valid analysis methods?

Do the researchers clearly explain their research, analysis, and sampling methods?

Did the researchers provide any caveats or advice on how to interpret their data?

Have you gathered the data yourself or were you in close contact with those who did?

Is the source biased?

Usually, flawed research methods become more apparent the further you get through a research report.

It's perfectly natural for good research to raise new questions, but the reader should have no uncertainty about what the data represents. There should be no doubt about matters such as:

Whether the sampling or analysis methods were based on sound and consistent logic

What the research samples are and where they came from

The accuracy of any statistical functions or equations

Validation of testing and measuring processes

When does a report require design validation?

A robust design validation process is often a gold standard in highly technical research reports. Design validation ensures the objects of a study are measured accurately, which lends more weight to your report and makes it valuable to more specialized industries.

Product development and engineering projects are the most common research-report examples that typically involve a design validation process. Depending on the scope and complexity of your research, you might face additional steps to validate your data and research procedures.

If you’re including design validation in the report (or report proposal), explain and justify your data-collection processes. Good design validation builds greater trust in a research report and lends more weight to its conclusions.

Choosing the right analysis method

Just as the quality of your report depends on properly validated research, a useful conclusion requires the most contextually relevant analysis method. This means comparing different statistical methods and choosing the one that makes the most sense for your research.

Most broadly, research analysis comes down to quantitative or qualitative methods (respectively: measurable by a number vs subjectively qualified values). There are also mixed research methods, which bridge the need for merging hard data with qualified assessments and still reach a cohesive set of conclusions.

Some of the most common analysis methods in research reports include:

Significance testing (aka hypothesis analysis), which compares test and control groups to determine how likely the data was the result of random chance.

Regression analysis , to establish relationships between variables, control for extraneous variables , and support correlation analysis.

Correlation analysis (aka bivariate testing), a method to identify and determine the strength of linear relationships between variables. It’s effective for detecting patterns from complex data, but care must be exercised to not confuse correlation with causation.

With any analysis method, it's important to justify which method you chose in the report. You should also provide estimates of the statistical accuracy (e.g., the p-value or confidence level of quantifiable data) of any data analysis.

This requires a commitment to the report's primary aim. For instance, this may be achieving a certain level of customer satisfaction by analyzing the cause and effect of changes to how service is delivered. Even better, use statistical analysis to calculate which change is most positively correlated with improved levels of customer satisfaction.

- Tips for writing research reports

There's endless good advice for writing effective research reports, and it almost all depends on the subjective aims of the people behind the report. Due to the wide variety of research reports, the best tips will be unique to each author's purpose.

Consider the following research report tips in any order, and take note of the ones most relevant to you:

No matter how in depth or detailed your report might be, provide a well-considered, succinct summary. At the very least, give your readers a quick and effective way to get up to speed.

Pare down your target audience (e.g., other researchers, employees, laypersons, etc.), and adjust your voice for their background knowledge and interest levels

For all but the most open-ended research, clarify your objectives, both for yourself and within the report.

Leverage your team members’ talents to fill in any knowledge gaps you might have. Your team is only as good as the sum of its parts.

Justify why your research proposal’s topic will endure long enough to derive value from the finished report.

Consolidate all research and analysis functions onto a single user-friendly platform. There's no reason to settle for less than developer-grade tools suitable for non-developers.

What's the format of a research report?

The research-reporting format is how the report is structured—a framework the authors use to organize their data, conclusions, arguments, and recommendations. The format heavily determines how the report's outline develops, because the format dictates the overall structure and order of information (based on the report's goals and research objectives).

What's the purpose of a research-report outline?

A good report outline gives form and substance to the report's objectives, presenting the results in a readable, engaging way. For any research-report format, the outline should create momentum along a chain of logic that builds up to a conclusion or interpretation.

What's the difference between a research essay and a research report?

There are several key differences between research reports and essays:

Research report:

Ordered into separate sections

More commercial in nature

Often includes infographics

Heavily descriptive

More self-referential

Usually provides recommendations

Research essay

Does not rely on research report formatting

More academically minded

Normally text-only

Less detailed

Omits discussion of methods

Usually non-prescriptive

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

One of the reasons for carrying out research is to add to the existing body of knowledge. Therefore, when conducting research, you need to document your processes and findings in a research report.

With a research report, it is easy to outline the findings of your systematic investigation and any gaps needing further inquiry. Knowing how to create a detailed research report will prove useful when you need to conduct research.

What is a Research Report?

A research report is a well-crafted document that outlines the processes, data, and findings of a systematic investigation. It is an important document that serves as a first-hand account of the research process, and it is typically considered an objective and accurate source of information.

In many ways, a research report can be considered as a summary of the research process that clearly highlights findings, recommendations, and other important details. Reading a well-written research report should provide you with all the information you need about the core areas of the research process.

Features of a Research Report

So how do you recognize a research report when you see one? Here are some of the basic features that define a research report.

- It is a detailed presentation of research processes and findings, and it usually includes tables and graphs.

- It is written in a formal language.

- A research report is usually written in the third person.

- It is informative and based on first-hand verifiable information.

- It is formally structured with headings, sections, and bullet points.

- It always includes recommendations for future actions.

Types of Research Report

The research report is classified based on two things; nature of research and target audience.

Nature of Research

- Qualitative Research Report

This is the type of report written for qualitative research . It outlines the methods, processes, and findings of a qualitative method of systematic investigation. In educational research, a qualitative research report provides an opportunity for one to apply his or her knowledge and develop skills in planning and executing qualitative research projects.

A qualitative research report is usually descriptive in nature. Hence, in addition to presenting details of the research process, you must also create a descriptive narrative of the information.

- Quantitative Research Report

A quantitative research report is a type of research report that is written for quantitative research. Quantitative research is a type of systematic investigation that pays attention to numerical or statistical values in a bid to find answers to research questions.

In this type of research report, the researcher presents quantitative data to support the research process and findings. Unlike a qualitative research report that is mainly descriptive, a quantitative research report works with numbers; that is, it is numerical in nature.

Target Audience

Also, a research report can be said to be technical or popular based on the target audience. If you’re dealing with a general audience, you would need to present a popular research report, and if you’re dealing with a specialized audience, you would submit a technical report.

- Technical Research Report

A technical research report is a detailed document that you present after carrying out industry-based research. This report is highly specialized because it provides information for a technical audience; that is, individuals with above-average knowledge in the field of study.

In a technical research report, the researcher is expected to provide specific information about the research process, including statistical analyses and sampling methods. Also, the use of language is highly specialized and filled with jargon.

Examples of technical research reports include legal and medical research reports.

- Popular Research Report

A popular research report is one for a general audience; that is, for individuals who do not necessarily have any knowledge in the field of study. A popular research report aims to make information accessible to everyone.

It is written in very simple language, which makes it easy to understand the findings and recommendations. Examples of popular research reports are the information contained in newspapers and magazines.

Importance of a Research Report

- Knowledge Transfer: As already stated above, one of the reasons for carrying out research is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, and this is made possible with a research report. A research report serves as a means to effectively communicate the findings of a systematic investigation to all and sundry.

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps: With a research report, you’d be able to identify knowledge gaps for further inquiry. A research report shows what has been done while hinting at other areas needing systematic investigation.

- In market research, a research report would help you understand the market needs and peculiarities at a glance.

- A research report allows you to present information in a precise and concise manner.

- It is time-efficient and practical because, in a research report, you do not have to spend time detailing the findings of your research work in person. You can easily send out the report via email and have stakeholders look at it.

Guide to Writing a Research Report

A lot of detail goes into writing a research report, and getting familiar with the different requirements would help you create the ideal research report. A research report is usually broken down into multiple sections, which allows for a concise presentation of information.

Structure and Example of a Research Report

This is the title of your systematic investigation. Your title should be concise and point to the aims, objectives, and findings of a research report.

- Table of Contents

This is like a compass that makes it easier for readers to navigate the research report.

An abstract is an overview that highlights all important aspects of the research including the research method, data collection process, and research findings. Think of an abstract as a summary of your research report that presents pertinent information in a concise manner.

An abstract is always brief; typically 100-150 words and goes straight to the point. The focus of your research abstract should be the 5Ws and 1H format – What, Where, Why, When, Who and How.

- Introduction

Here, the researcher highlights the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation as well as the problem which the systematic investigation sets out to solve. When writing the report introduction, it is also essential to indicate whether the purposes of the research were achieved or would require more work.

In the introduction section, the researcher specifies the research problem and also outlines the significance of the systematic investigation. Also, the researcher is expected to outline any jargons and terminologies that are contained in the research.

- Literature Review

A literature review is a written survey of existing knowledge in the field of study. In other words, it is the section where you provide an overview and analysis of different research works that are relevant to your systematic investigation.

It highlights existing research knowledge and areas needing further investigation, which your research has sought to fill. At this stage, you can also hint at your research hypothesis and its possible implications for the existing body of knowledge in your field of study.

- An Account of Investigation

This is a detailed account of the research process, including the methodology, sample, and research subjects. Here, you are expected to provide in-depth information on the research process including the data collection and analysis procedures.

In a quantitative research report, you’d need to provide information surveys, questionnaires and other quantitative data collection methods used in your research. In a qualitative research report, you are expected to describe the qualitative data collection methods used in your research including interviews and focus groups.

In this section, you are expected to present the results of the systematic investigation.

This section further explains the findings of the research, earlier outlined. Here, you are expected to present a justification for each outcome and show whether the results are in line with your hypotheses or if other research studies have come up with similar results.

- Conclusions

This is a summary of all the information in the report. It also outlines the significance of the entire study.

- References and Appendices

This section contains a list of all the primary and secondary research sources.

Tips for Writing a Research Report

- Define the Context for the Report

As is obtainable when writing an essay, defining the context for your research report would help you create a detailed yet concise document. This is why you need to create an outline before writing so that you do not miss out on anything.

- Define your Audience

Writing with your audience in mind is essential as it determines the tone of the report. If you’re writing for a general audience, you would want to present the information in a simple and relatable manner. For a specialized audience, you would need to make use of technical and field-specific terms.

- Include Significant Findings

The idea of a research report is to present some sort of abridged version of your systematic investigation. In your report, you should exclude irrelevant information while highlighting only important data and findings.

- Include Illustrations

Your research report should include illustrations and other visual representations of your data. Graphs, pie charts, and relevant images lend additional credibility to your systematic investigation.

- Choose the Right Title

A good research report title is brief, precise, and contains keywords from your research. It should provide a clear idea of your systematic investigation so that readers can grasp the entire focus of your research from the title.

- Proofread the Report

Before publishing the document, ensure that you give it a second look to authenticate the information. If you can, get someone else to go through the report, too, and you can also run it through proofreading and editing software.

How to Gather Research Data for Your Report

- Understand the Problem

Every research aims at solving a specific problem or set of problems, and this should be at the back of your mind when writing your research report. Understanding the problem would help you to filter the information you have and include only important data in your report.

- Know what your report seeks to achieve

This is somewhat similar to the point above because, in some way, the aim of your research report is intertwined with the objectives of your systematic investigation. Identifying the primary purpose of writing a research report would help you to identify and present the required information accordingly.

- Identify your audience

Knowing your target audience plays a crucial role in data collection for a research report. If your research report is specifically for an organization, you would want to present industry-specific information or show how the research findings are relevant to the work that the company does.

- Create Surveys/Questionnaires

A survey is a research method that is used to gather data from a specific group of people through a set of questions. It can be either quantitative or qualitative.

A survey is usually made up of structured questions, and it can be administered online or offline. However, an online survey is a more effective method of research data collection because it helps you save time and gather data with ease.

You can seamlessly create an online questionnaire for your research on Formplus . With the multiple sharing options available in the builder, you would be able to administer your survey to respondents in little or no time.

Formplus also has a report summary too l that you can use to create custom visual reports for your research.

Step-by-step guide on how to create an online questionnaire using Formplus

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different online questionnaires for your research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on Create new form to begin.

- Edit Form Title : Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Research Questionnaire.”

- Edit Form : Click on the edit icon to edit the form.

- Add Fields : Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

- Edit fields

- Click on “Save”

- Form Customization: With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options: Formplus offers various form-sharing options, which enables you to share your questionnaire with respondents easily. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages. You can also send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Always remember that a research report is just as important as the actual systematic investigation because it plays a vital role in communicating research findings to everyone else. This is why you must take care to create a concise document summarizing the process of conducting any research.

In this article, we’ve outlined essential tips to help you create a research report. When writing your report, you should always have the audience at the back of your mind, as this would set the tone for the document.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- research report

- research report survey

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

Assessment Tools: Types, Examples & Importance

In this article, you’ll learn about different assessment tools to help you evaluate performance in various contexts

Ethnographic Research: Types, Methods + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on ethnographic research, it types, methods, examples and advantages. Also highlights how to conduct an ethnographic...

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Reports: Definition and How to Write Them

Reports are usually spread across a vast horizon of topics but are focused on communicating information about a particular topic and a niche target market. The primary motive of research reports is to convey integral details about a study for marketers to consider while designing new strategies.

Certain events, facts, and other information based on incidents need to be relayed to the people in charge, and creating research reports is the most effective communication tool. Ideal research reports are extremely accurate in the offered information with a clear objective and conclusion. These reports should have a clean and structured format to relay information effectively.

What are Research Reports?

Research reports are recorded data prepared by researchers or statisticians after analyzing the information gathered by conducting organized research, typically in the form of surveys or qualitative methods .

A research report is a reliable source to recount details about a conducted research. It is most often considered to be a true testimony of all the work done to garner specificities of research.

The various sections of a research report are:

- Background/Introduction

- Implemented Methods

- Results based on Analysis

- Deliberation

Learn more: Quantitative Research

Components of Research Reports

Research is imperative for launching a new product/service or a new feature. The markets today are extremely volatile and competitive due to new entrants every day who may or may not provide effective products. An organization needs to make the right decisions at the right time to be relevant in such a market with updated products that suffice customer demands.

The details of a research report may change with the purpose of research but the main components of a report will remain constant. The research approach of the market researcher also influences the style of writing reports. Here are seven main components of a productive research report:

- Research Report Summary: The entire objective along with the overview of research are to be included in a summary which is a couple of paragraphs in length. All the multiple components of the research are explained in brief under the report summary. It should be interesting enough to capture all the key elements of the report.

- Research Introduction: There always is a primary goal that the researcher is trying to achieve through a report. In the introduction section, he/she can cover answers related to this goal and establish a thesis which will be included to strive and answer it in detail. This section should answer an integral question: “What is the current situation of the goal?”. After the research design was conducted, did the organization conclude the goal successfully or they are still a work in progress – provide such details in the introduction part of the research report.

- Research Methodology: This is the most important section of the report where all the important information lies. The readers can gain data for the topic along with analyzing the quality of provided content and the research can also be approved by other market researchers . Thus, this section needs to be highly informative with each aspect of research discussed in detail. Information needs to be expressed in chronological order according to its priority and importance. Researchers should include references in case they gained information from existing techniques.

- Research Results: A short description of the results along with calculations conducted to achieve the goal will form this section of results. Usually, the exposition after data analysis is carried out in the discussion part of the report.

Learn more: Quantitative Data

- Research Discussion: The results are discussed in extreme detail in this section along with a comparative analysis of reports that could probably exist in the same domain. Any abnormality uncovered during research will be deliberated in the discussion section. While writing research reports, the researcher will have to connect the dots on how the results will be applicable in the real world.

- Research References and Conclusion: Conclude all the research findings along with mentioning each and every author, article or any content piece from where references were taken.

Learn more: Qualitative Observation

15 Tips for Writing Research Reports

Writing research reports in the manner can lead to all the efforts going down the drain. Here are 15 tips for writing impactful research reports:

- Prepare the context before starting to write and start from the basics: This was always taught to us in school – be well-prepared before taking a plunge into new topics. The order of survey questions might not be the ideal or most effective order for writing research reports. The idea is to start with a broader topic and work towards a more specific one and focus on a conclusion or support, which a research should support with the facts. The most difficult thing to do in reporting, without a doubt is to start. Start with the title, the introduction, then document the first discoveries and continue from that. Once the marketers have the information well documented, they can write a general conclusion.

- Keep the target audience in mind while selecting a format that is clear, logical and obvious to them: Will the research reports be presented to decision makers or other researchers? What are the general perceptions around that topic? This requires more care and diligence. A researcher will need a significant amount of information to start writing the research report. Be consistent with the wording, the numbering of the annexes and so on. Follow the approved format of the company for the delivery of research reports and demonstrate the integrity of the project with the objectives of the company.

- Have a clear research objective: A researcher should read the entire proposal again, and make sure that the data they provide contributes to the objectives that were raised from the beginning. Remember that speculations are for conversations, not for research reports, if a researcher speculates, they directly question their own research.

- Establish a working model: Each study must have an internal logic, which will have to be established in the report and in the evidence. The researchers’ worst nightmare is to be required to write research reports and realize that key questions were not included.

Learn more: Quantitative Observation

- Gather all the information about the research topic. Who are the competitors of our customers? Talk to other researchers who have studied the subject of research, know the language of the industry. Misuse of the terms can discourage the readers of research reports from reading further.

- Read aloud while writing. While reading the report, if the researcher hears something inappropriate, for example, if they stumble over the words when reading them, surely the reader will too. If the researcher can’t put an idea in a single sentence, then it is very long and they must change it so that the idea is clear to everyone.

- Check grammar and spelling. Without a doubt, good practices help to understand the report. Use verbs in the present tense. Consider using the present tense, which makes the results sound more immediate. Find new words and other ways of saying things. Have fun with the language whenever possible.

- Discuss only the discoveries that are significant. If some data are not really significant, do not mention them. Remember that not everything is truly important or essential within research reports.

Learn more: Qualitative Data

- Try and stick to the survey questions. For example, do not say that the people surveyed “were worried” about an research issue , when there are different degrees of concern.

- The graphs must be clear enough so that they understand themselves. Do not let graphs lead the reader to make mistakes: give them a title, include the indications, the size of the sample, and the correct wording of the question.

- Be clear with messages. A researcher should always write every section of the report with an accuracy of details and language.

- Be creative with titles – Particularly in segmentation studies choose names “that give life to research”. Such names can survive for a long time after the initial investigation.

- Create an effective conclusion: The conclusion in the research reports is the most difficult to write, but it is an incredible opportunity to excel. Make a precise summary. Sometimes it helps to start the conclusion with something specific, then it describes the most important part of the study, and finally, it provides the implications of the conclusions.

- Get a couple more pair of eyes to read the report. Writers have trouble detecting their own mistakes. But they are responsible for what is presented. Ensure it has been approved by colleagues or friends before sending the find draft out.

Learn more: Market Research and Analysis

MORE LIKE THIS

21 Best Customer Advocacy Software for Customers in 2024

Apr 19, 2024

10 Quantitative Data Analysis Software for Every Data Scientist

Apr 18, 2024

11 Best Enterprise Feedback Management Software in 2024

17 Best Online Reputation Management Software in 2024

Apr 17, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Writing up a Research Report

- First Online: 04 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

302 Accesses

A research report is one big argument about how and why you came up with your conclusions. To make it a convincing argument, a typical guiding structure has developed. In the different chapters, there are distinct issues that need to be addressed to explain to the reader why your conclusions are valid. The governing principle for writing the report is full disclosure: to explain everything and ensure replicability by another researcher.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barros, L. O. (2016). The only academic phrasebook you’ll ever need . Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

Google Scholar

Field, A. (2016). An adventure in statistics. The reality enigma . SAGE.

Field, A. (2020). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Früh, M., Keimer, I., & Blankenagel, M. (2019). The impact of Balanced Scorecard excellence on shareholder returns. IFZ Working Paper No. 0003/2019. https://zenodo.org/record/2571603#.YMDUafkzZaQ . Accessed: 9 June 2021.

Pearl, J., & Mackenzie, D. (2018). The book of why: The new science of cause and effect. Basic Books.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wirtschaft/IFZ, Campus Zug-Rotkreuz, Hochschule Luzern, Zug-Rotkreuz, Zug, Switzerland

Stefan Hunziker & Michael Blankenagel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Hunziker .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Hunziker, S., Blankenagel, M. (2024). Writing up a Research Report. In: Research Design in Business and Management. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_4

Published : 04 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-42738-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-42739-9

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 The Purpose of Research Writing

Learning objectives.

- Identify reasons to research writing projects.

- Outline the steps of the research writing process.

Why was the Great Wall of China built? What have scientists learned about the possibility of life on Mars? What roles did women play in the American Revolution? How does the human brain create, store, and retrieve memories? Who invented the game of football, and how has it changed over the years?

You may know the answers to these questions off the top of your head. If you are like most people, however, you find answers to tough questions like these by searching the Internet, visiting the library, or asking others for information. To put it simply, you perform research.

Whether you are a scientist, an artist, a paralegal, or a parent, you probably perform research in your everyday life. When your boss, your instructor, or a family member asks you a question that you do not know the answer to, you locate relevant information, analyze your findings, and share your results. Locating, analyzing, and sharing information are key steps in the research process, and in this chapter, you will learn more about each step. By developing your research writing skills, you will prepare yourself to answer any question no matter how challenging.

Reasons for Research

When you perform research, you are essentially trying to solve a mystery—you want to know how something works or why something happened. In other words, you want to answer a question that you (and other people) have about the world. This is one of the most basic reasons for performing research.

But the research process does not end when you have solved your mystery. Imagine what would happen if a detective collected enough evidence to solve a criminal case, but she never shared her solution with the authorities. Presenting what you have learned from research can be just as important as performing the research. Research results can be presented in a variety of ways, but one of the most popular—and effective—presentation forms is the research paper . A research paper presents an original thesis, or purpose statement, about a topic and develops that thesis with information gathered from a variety of sources.

If you are curious about the possibility of life on Mars, for example, you might choose to research the topic. What will you do, though, when your research is complete? You will need a way to put your thoughts together in a logical, coherent manner. You may want to use the facts you have learned to create a narrative or to support an argument. And you may want to show the results of your research to your friends, your teachers, or even the editors of magazines and journals. Writing a research paper is an ideal way to organize thoughts, craft narratives or make arguments based on research, and share your newfound knowledge with the world.

Write a paragraph about a time when you used research in your everyday life. Did you look for the cheapest way to travel from Houston to Denver? Did you search for a way to remove gum from the bottom of your shoe? In your paragraph, explain what you wanted to research, how you performed the research, and what you learned as a result.

Research Writing and the Academic Paper

No matter what field of study you are interested in, you will most likely be asked to write a research paper during your academic career. For example, a student in an art history course might write a research paper about an artist’s work. Similarly, a student in a psychology course might write a research paper about current findings in childhood development.

Having to write a research paper may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and writing a long paper requires a lot of time, effort, and organization. However, writing a research paper can also be a great opportunity to explore a topic that is particularly interesting to you. The research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice, and the writing process helps you remember what you have learned and understand it on a deeper level.

Research Writing at Work

Knowing how to write a good research paper is a valuable skill that will serve you well throughout your career. Whether you are developing a new product, studying the best way to perform a procedure, or learning about challenges and opportunities in your field of employment, you will use research techniques to guide your exploration. You may even need to create a written report of your findings. And because effective communication is essential to any company, employers seek to hire people who can write clearly and professionally.

Writing at Work

Take a few minutes to think about each of the following careers. How might each of these professionals use researching and research writing skills on the job?

- Medical laboratory technician

- Small business owner

- Information technology professional

- Freelance magazine writer

A medical laboratory technician or information technology professional might do research to learn about the latest technological developments in either of these fields. A small business owner might conduct research to learn about the latest trends in his or her industry. A freelance magazine writer may need to research a given topic to write an informed, up-to-date article.

Think about the job of your dreams. How might you use research writing skills to perform that job? Create a list of ways in which strong researching, organizing, writing, and critical thinking skills could help you succeed at your dream job. How might these skills help you obtain that job?

Steps of the Research Writing Process

How does a research paper grow from a folder of brainstormed notes to a polished final draft? No two projects are identical, but most projects follow a series of six basic steps.

These are the steps in the research writing process:

- Choose a topic.

- Plan and schedule time to research and write.

- Conduct research.

- Organize research and ideas.

- Draft your paper.

- Revise and edit your paper.

Each of these steps will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. For now, though, we will take a brief look at what each step involves.

Step 1: Choosing a Topic

As you may recall from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , to narrow the focus of your topic, you may try freewriting exercises, such as brainstorming. You may also need to ask a specific research question —a broad, open-ended question that will guide your research—as well as propose a possible answer, or a working thesis . You may use your research question and your working thesis to create a research proposal . In a research proposal, you present your main research question, any related subquestions you plan to explore, and your working thesis.

Step 2: Planning and Scheduling

Before you start researching your topic, take time to plan your researching and writing schedule. Research projects can take days, weeks, or even months to complete. Creating a schedule is a good way to ensure that you do not end up being overwhelmed by all the work you have to do as the deadline approaches.

During this step of the process, it is also a good idea to plan the resources and organizational tools you will use to keep yourself on track throughout the project. Flowcharts, calendars, and checklists can all help you stick to your schedule. See Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” for an example of a research schedule.

Step 3: Conducting Research

When going about your research, you will likely use a variety of sources—anything from books and periodicals to video presentations and in-person interviews.

Your sources will include both primary sources and secondary sources . Primary sources provide firsthand information or raw data. For example, surveys, in-person interviews, and historical documents are primary sources. Secondary sources, such as biographies, literary reviews, or magazine articles, include some analysis or interpretation of the information presented. As you conduct research, you will take detailed, careful notes about your discoveries. You will also evaluate the reliability of each source you find.

Step 4: Organizing Research and the Writer’s Ideas

When your research is complete, you will organize your findings and decide which sources to cite in your paper. You will also have an opportunity to evaluate the evidence you have collected and determine whether it supports your thesis, or the focus of your paper. You may decide to adjust your thesis or conduct additional research to ensure that your thesis is well supported.

Remember, your working thesis is not set in stone. You can and should change your working thesis throughout the research writing process if the evidence you find does not support your original thesis. Never try to force evidence to fit your argument. For example, your working thesis is “Mars cannot support life-forms.” Yet, a week into researching your topic, you find an article in the New York Times detailing new findings of bacteria under the Martian surface. Instead of trying to argue that bacteria are not life forms, you might instead alter your thesis to “Mars cannot support complex life-forms.”

Step 5: Drafting Your Paper

Now you are ready to combine your research findings with your critical analysis of the results in a rough draft. You will incorporate source materials into your paper and discuss each source thoughtfully in relation to your thesis or purpose statement.

When you cite your reference sources, it is important to pay close attention to standard conventions for citing sources in order to avoid plagiarism , or the practice of using someone else’s words without acknowledging the source. Later in this chapter, you will learn how to incorporate sources in your paper and avoid some of the most common pitfalls of attributing information.

Step 6: Revising and Editing Your Paper

In the final step of the research writing process, you will revise and polish your paper. You might reorganize your paper’s structure or revise for unity and cohesion, ensuring that each element in your paper flows into the next logically and naturally. You will also make sure that your paper uses an appropriate and consistent tone.

Once you feel confident in the strength of your writing, you will edit your paper for proper spelling, grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting. When you complete this final step, you will have transformed a simple idea or question into a thoroughly researched and well-written paper you can be proud of!

Review the steps of the research writing process. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In which steps of the research writing process are you allowed to change your thesis?

- In step 2, which types of information should you include in your project schedule?

- What might happen if you eliminated step 4 from the research writing process?

Key Takeaways

- People undertake research projects throughout their academic and professional careers in order to answer specific questions, share their findings with others, increase their understanding of challenging topics, and strengthen their researching, writing, and analytical skills.

- The research writing process generally comprises six steps: choosing a topic, scheduling and planning time for research and writing, conducting research, organizing research and ideas, drafting a paper, and revising and editing the paper.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How to produce a research report

A research report is a document in which a researcher presents the results of an original study. In the past, research reports were published as PDFs. But as you will see from the examples in this guide, the best research reports today are published as highly visual, interactive web pages.

Indeed — over the last five years, we’ve seen an explosion of research reports and white papers from businesses and NGOs.

Take, for example, this recent report on Green Mortgages from IMLA, made with the assistance of digital agency Rostrum. It’s a beautifully designed report, rich with infographics and data visualisations .

The biggest SaaS companies are also investing in reports, including Slack , Twilio , and Atlassian .

It's not only businesses publishing reports. The white paper below, from the Publishers Association, dives into an initiative on the future role of artificial intelligence in the publishing industry.

Join the BBC, Penguin, and the University of Cambridge. Craft stunning, interactive web content with Shorthand. Publish your first story for free — no code or web design skills required. Sign up now.

What is a research report?

A research report is an in-depth document that contains the results of a research project. It includes information about the research topic, the research question, the methodology used to collect data from respondents, the results of the research, and the conclusion of the researcher.

The report also includes information about the funding source or partnerships for the project, if applicable. The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of research studies to a wider audience. The report should be clear, concise, and well-organised so that readers can easily understand the information presented.

Many research reports are formally structured, with headings and — for PDFs — page numbers,

As mentioned above, research reports have traditionally been published as PDFs , but are increasingly moving to interactive content .

The rise of the research report

Why are these organisations investing in research reports and white papers?

Most of these teams aren’t filled with scientists or academics, and their readers aren’t usually trawling research databases for help with their work.

The reason is — let’s be blunt — most content published on the web underwhelms.

Even on the most well-attended blogs, organic traffic and dwell-time generally remains flat. CTAs are stubbornly un-clicked. The common fate of most content is to gather dust almost immediately after publication.

There are many reasons for this. Search has clearly become much more competitive. It’s difficult for most organisations to get their ordinary blog content ranked anywhere near the first page.

Social media, too, has long been a ‘pay-to-play’ environment, with only extremely brave (or foolish) content teams banking on their posts going viral.

The move to quality over quantity

To meet these challenges, the most successful content teams have committed to producing high-quality content. Rather than pumping out content-for-content’s-sake — which, to be frank, few humans actually want to read — these teams produce content that helps, informs, and delights their readers.

High quality content takes a range of forms, including ebooks, longform content , all-encompassing ‘skyscraper’ guides, and feature stories . It's often highly visual, immersive, and multimedia, and can include elements like audio, video, and interactive infographics .

Because this content is produced to genuinely help the reader, it’s much more likely to be read, shared, and — critically for SEO — linked. Readers tend to stay on the page for longer, another key metric for SEO. They’re also more likely to click calls-to-action.

This is borne out by our customers at Shorthand. After nine months using Shorthand as an investment in producing high quality content, Imperial College London’s feature stories saw 142% higher average unique pageviews and 50% higher average time on page.

Honda, too, saw the average site dwell time increase by 85% after transitioning to publishing immersive, high quality digital stories (again, built with Shorthand).

Clearly, quality content gets better results. But it isn’t easy to make. It requires investment, dedication, and clear goals.

In this guide, we focus on one of the best-performing genres of quality content — the research report, which has become the not-so-secret weapon for the world’s leading content teams.

What should a research report include?

For most organisations, research reports will sit somewhere between marketing and academia.

On the one hand, they need to be as rigorous, scientific, and statistically literate as any published research paper. There's no point — and real reputational risk — in publishing a sloppy, factually inaccurate report.

On the other hand, most research reports outside of academia are published to support sales and marketing efforts. For some companies, such as market research firms, these reports are the product itself. Research reports need to be beautifully produced, clearly written, and have clear takeaways for the reader.

But unlike academia, there's also no one-size-fits-all structure. With that in mind, here are some common sections to keep in mind when writing a research report.

Navigation . For print reports and PDFs, it's common to include a table of contents after the title page. But if you're producing your report natively for the web — which we highly recommend — then it's worth giving your reader a way to jump back and forth. At Shorthand, we make it simple to create a custom top navigation, which allows readers to easily browse through longer content.

Introduction section . For research reports, your introduction is a good opportunity to outline the scope of your work; note your research questions, research design, and research methods; establish context and significance; and add any background information you think might be relevant.

Literature review . These take a specific form in academic research, but outside of academia, it might pay to show some awareness of other research that has been conducted in your space.

Research Methodology . Again, this doesn't need to have all the rigour of an academic journal article. But to establish credibility, it pays to outline how you produced and analysed the qualitative or quantitative data at the heart of your report. For example, if you collected your data from an online questionnaire, it pays to point this out.

Research findings . The most important part of your report will be your results section, covering of your findings. As we discuss below, for quantitative research, this section should be rich with data visualisations and infographics . This will likely be the most compelling part of the report for your readers.

Discussion section . This is where you can contextualise the results, and offer an argument about the significance of the data. In many research reports for brands, this section and the 'research findings' sections are merged.

Conclusion. This is where you can pull the various threads of your research report together. This will also allow you to carefully advance an argument about the significance of the research, and what it suggests about the future.

Craft stunning, interactive research reports with Shorthand. Publish your first story for free — no code or web design skills required. Sign up now.

Trust the process

More than any other genre of content, research reports require consistent — and persistent — project management. Unlike blog posts or case studies, a research report can't be turned around in a week or two.

This can be daunting for teams that haven't published research before — and daunting projects have a way of getting postponed.

As with any large project, the best thing to do is create a realistic plan. This plan will need to include all the different stakeholders — including writers, designers, and management — and factor in their likely contribution. Part of this will involve taking a realistic look at their future commitments.

Plan time for data collection, drafting, data visualisation, design, editing , and writing. This will all take longer than you think.

Once you've established your plan — and once it's been signed off by all relevant stakeholders — stick to it. Trust it. Try not to deviate too much from the process.

Produce fresh data

Data is the core of any research report. It will be the stuff that gets quoted and highlighted, and it will be what earns your report any backlinks or extra addition.

Without fresh data, your report is just another bunch of unsupported assertions — and there’s more than enough of those on the web already.

The way you get fresh data will depend on what exactly you’re researching. You might be analysing usage patterns in software. You might be interviewing your customers or a professional cohort.

It could be anything — but whatever it is, make sure it’s fresh and unique to your report.

If you're looking for more examples and inspiration, check out our guide on how to get started with data storytelling , as well as our post on 8 examples of powerful data stories .

Don't cut corners with the data

(or anything else).

Odds are, your research report isn’t going to be peer reviewed, and it won’t be published in a scientific journal. But this doesn't give you an excuse to cut corners.

A research report is a form of ‘anchor’ content. It is specifically produced to earn attention for your brand.

But attention can swing both ways. If people notice mistakes or major errors in your report, then this will impact the reputation of your organisation.

What are the most common mistakes for research reports?

The most common areas where research reports fall down are in data collection, data analysis, and data visualisation. Make sure you have someone sufficiently numerate to double-check your process and results.

Establish the reputation of your brand

A research report is an invaluable way to establish your brand as a leader in your field. This is important for SEO and engagement. But it’s also important for the buying process — whatever it is your organisation is trying to sell.

Simply put, potential leads are much more likely to take action with organisations that they trust. This is true for businesses — but it is also true for NGOs, universities, and government agencies.

You can read more in our guide to brand storytelling .

The most effective research reports are presented as a neutral interpretation of data — without any embellishment or sales flourishes.

Ideally, you want your readers to engage with your report as an accurate representation of the world. You want them to trust it — and trust you. Anything that betrays your agenda will weaken this trust, and make the report less effective.

Obviously, your report isn’t neutral. It’s an investment in a piece of content. And, like all content you publish, you have an end goal in mind.

But, done well, a professionally produced report will accomplish those goals — including better engagement, reputational gain, and lead generation — without you needing to aggressively sell your product or service.

Visualise your data

After collecting data and analysing your findings, you need to consider your data visualisations. This includes any relevant charts, graphs, and maps.

Your data visualisations will be the centrepiece of your report. They will likely be the parts of your report that readers skip to. They’re also likely to be the information readers retain and share.

With this in mind, they're worth doing right. There are many different data visualisation tools out there, and there's no single best approach.

Read more about data visualisation in our guide to effective data journalism .

Some reports will benefit from a chart or map that readers can click and interrogate in the browser. Others will benefit from scroll-based animation, as used in this story from the Council of the European Union.

One constant across the best research reports on the web, though, is the use of interactive data visualisation. While it was common in the past to use static images of charts and graphs — usually recycling visual assets used in the PDF version of the report — this approach is gradually being supplanted by more advanced techniques.

Some of these data visualisation techniques will require web design and developer resource. Others — like Shorthand itself — will be easier to use out-of-the-box.

PDFs are an extraordinarily common method of publishing research reports — even today. Indeed, some organisations publish their reports as ‘PDF-first,’ with any web publication treated as a poor cousin.

This is the wrong approach. And with the rise of new web technologies and more powerful web browsers, it’s also extremely outdated. For better results, we recommend producing reports first and foremost for the web.

Web-based reports have many distinct advantages over the PDF, including:

- They can be read on all screen sizes, including phones. No pinching or zooming required.

- They can be easily indexed and optimised for search.

- They can include interactive data visualisations and animations, video, and high resolution images. Even the most beautiful PDF can't compete with a visually-immersive digital story.

- They are easier to share. A high-resolution PDF is simply too clunky to share on all channels (including social media).

If you want you to read more about the problems with the PDF, check out our guide on why the PDF is falling out of favour .

Get inspired by the best

With the rise of digital storytelling platforms, the calibre of published research reports on the web has improved markedly. That means that there are plenty of excellent reports to check out for inspiration.

At Shorthand, we’ve collected some of the best reports — including thought-leadership reports, annual reports for businesses and NGOs, and original research — in our collection of featured stories .

Publish your first story free with Shorthand

Craft sumptuous content at speed. No code required.

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews

Primary Research: Definitions and Overview

How research is defined varies widely from field to field, and as you progress through your college career, your coursework will teach you much more about what it means to be a researcher within your field.* For example, engineers, who focus on applying scientific knowledge to develop designs, processes, and objects, conduct research using simulations, mathematical models, and a variety of tests to see how well their designs work. Sociologists conduct research using surveys, interviews, observations, and statistical analysis to better understand people, societies, and cultures. Graphic designers conduct research through locating images for reference for their artwork and engaging in background research on clients and companies to best serve their needs. Historians conduct research by examining archival materials—newspapers, journals, letters, and other surviving texts—and through conducting oral history interviews. Research is not limited to what has already been written or found at the library, also known as secondary research. Rather, individuals conducting research are producing the articles and reports found in a library database or in a book. Primary research, the focus of this essay, is research that is collected firsthand rather than found in a book, database, or journal.

Primary research is often based on principles of the scientific method, a theory of investigation first developed by John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century in his book Philosophy of the Scientific Method . Although the application of the scientific method varies from field to field, the general principles of the scientific method allow researchers to learn more about the world and observable phenomena. Using the scientific method, researchers develop research questions or hypotheses and collect data on events, objects, or people that is measurable, observable, and replicable. The ultimate goal in conducting primary research is to learn about something new that can be confirmed by others and to eliminate our own biases in the process.

Essay Overview and Student Examples

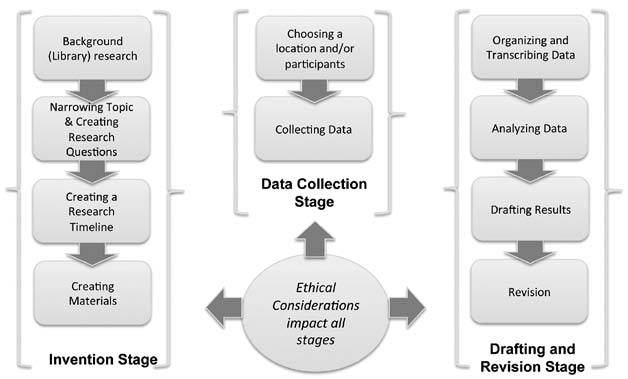

The essay begins by providing an overview of ethical considerations when conducting primary research, and then covers the stages that you will go through in your primary research: planning, collecting, analyzing, and writing. After the four stages comes an introduction to three common ways of conducting primary research in first year writing classes:

Observations . Observing and measuring the world around you, including observations of people and other measurable events.

Interviews . Asking participants questions in a one-on-one or small group setting.

Surveys . Asking participants about their opinions and behaviors through a short questionnaire.

In addition, we will be examining two student projects that used substantial portions of primary research:

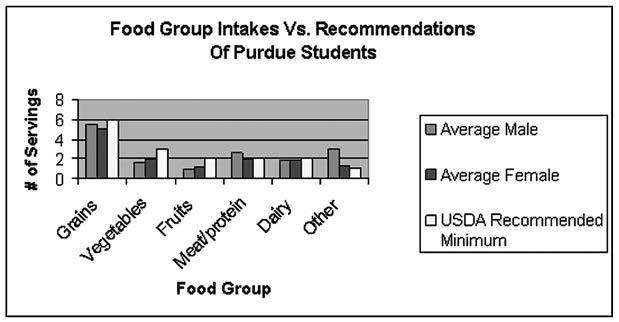

Derek Laan, a nutrition major at Purdue University, wanted to learn more about student eating habits on campus. His primary re-search included observations of the campus food courts, student behavior while in the food courts, and a survey of students’ daily food intake. His secondary research included looking at national student eating trends on college campuses, information from the United States Food and Drug Administration, and books on healthy eating.

Jared Schwab, an agricultural and biological engineering major at Purdue, was interested in learning more about how writing and communication took place in his field. His primary research included interviewing a professional engineer and a student who was a senior majoring in engineering. His secondary research included examining journals, books, professional organizations, and writing guides within the field of engineering.

Ethics of Primary Research

Both projects listed above included primary research on human participants; therefore, Derek and Jared both had to consider research ethics throughout their primary research process. As Earl Babbie writes in The Practice of Social Research , throughout the early and middle parts of the twentieth century researchers took advantage of participants and treated them unethically. During World War II, Nazi doctors performed heinous experiments on prisoners without their consent, while in the U.S., a number of medical and psychological experiments on caused patients undue mental and physical trauma and, in some cases, death. Because of these and other similar events, many nations have established ethical laws and guidelines for researchers who work with human participants. In the United States, the guidelines for the ethical treatment of human research participants are described in The Belmont Report , released in 1979. Today, universities have Institutional Review Boards (or IRBs) that oversee research. Students conducting research as part of a class may not need permission from the university’s IRB, although they still need to ensure that they follow ethical guidelines in research. The following provides a brief overview of ethical considerations:

- Voluntary participation . The Belmont Report suggests that, in most cases, you need to get permission from people before you involve them in any primary research you are conducting. If you are doing a survey or interview, your participants must first agree to fill out your survey or to be interviewed. Consent for observations can be more complicated, and is dis-cussed later in the essay.

Confidentiality and anonymity . Your participants may reveal embarrassing or potentially damaging information such as racist comments or unconventional behavior. In these cases, you should keep your participants’ identities anonymous when writing your results. An easy way to do this is to create a “pseudonym” (or false name) for them so that their identity is protected.

Researcher bias . There is little point in collecting data and learning about something if you already think you know the answer! Bias might be present in the way you ask questions, the way you take notes, or the conclusions you draw from the data you collect.

The above are only three of many considerations when involving human participants in your primary research. For a complete under-standing of ethical considerations please refer to The Belmont Report .

Now that we have considered the ethical implications of research, we will examine how to formulate research questions and plan your primary research project.

Planning Your Primary Research Project