What Is a Senior Thesis?

Daniel Ingold/Cultura/Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A senior thesis is a large, independent research project that students take on during their senior year of high school or college to fulfill their graduation requirement. It is the culminating work of their studies at a particular institution, and it represents their ability to conduct research and write effectively. For some students, a senior thesis is a requirement for graduating with honors.

Students typically work closely with an advisor and choose a question or topic to explore before carrying out an extensive research plan.

Style Manuals and the Paper's Organization

The structure of your research paper will depend, in part, on the style manual that is required by your instructor. Different disciplines, such as history, science, or education, have different rules to abide by when it comes to research paper construction, organization, and modes of citation. The styles for different types of assignment include:

Modern Language Association (MLA): The disciplines that tend to prefer the MLA style guide include literature, arts, and the humanities, such as linguistics, religion, and philosophy. To follow this style, you will use parenthetical citations to indicate your sources and a works cited page to show the list of books and articles you consulted.

American Psychological Association (APA): The APA style manual tends to be used in psychology, education, and some of the social sciences. This type of report may require the following:

- Introduction

Chicago style: "The Chicago Manual of Style" is used in most college-level history courses as well as professional publications that contain scholarly articles. Chicago style may call for endnotes or footnotes corresponding to a bibliography page at the back or the author-date style of in-text citation, which uses parenthetical citations and a references page at the end.

Turabian style: Turabian is a student version of Chicago style. It requires some of the same formatting techniques as Chicago, but it includes special rules for writing college-level papers, such as book reports. A Turabian research paper may call for endnotes or footnotes and a bibliography.

Science style: Science instructors may require students to use a format that is similar to the structure used in publishing papers in scientific journals. The elements you would include in this sort of paper include:

- List of materials and methods used

- Results of your methods and experiments

- Acknowledgments

American Medical Association (AMA): The AMA style book might be required for students in medical or premedical degree programs in college. Parts of an AMA research paper might include:

- Proper headings and lists

- Tables and figures

- In-text citations

- Reference list

Choose Your Topic Carefully

Starting off with a bad, difficult, or narrow topic likely won't lead to a positive result. Don't choose a question or statement that's so broad that it's overwhelming and could comprise a lifetime of research or a topic that's so narrow you'll struggle to compose 10 pages. Consider a topic that has a lot of recent research so you won't struggle to put your hands on current or adequate sources.

Select a topic that interests you. Putting in long hours on a subject that bores you will be arduous—and ripe for procrastination. If a professor recommends an area of interest, make sure it excites you.

Also, consider expanding a paper you've already written; you'll hit the ground running because you've already done some research and know the topic. Last, consult with your advisor before finalizing your topic. You don't want to put in a lot of hours on a subject that is rejected by your instructor.

Organize Your Time

Plan to spend half of your time researching and the other half writing. Often, students spend too much time researching and then find themselves in a crunch, madly writing in the final hours. Give yourself goals to reach along certain "signposts," such as the number of hours you want to have invested each week or by a certain date or how much you want to have completed in those same timeframes.

Organize Your Research

Compose your works cited or bibliography entries as you work on your paper. This is especially important if your style manual requires you to use access dates for any online sources that you review or requires page numbers be included in the citations. You don't want to end up at the very end of the project and not know what day you looked at a particular website or have to search through a hard-copy book looking for a quote that you included in the paper. Save PDFs of online sites, too, as you wouldn't want to need to look back at something and not be able to get online or find that the article has been removed since you read it.

Choose an Advisor You Trust

This may be your first opportunity to work with direct supervision. Choose an advisor who's familiar with the field, and ideally select someone you like and whose classes you've already taken. That way you'll have a rapport from the start.

Consult Your Instructor

Remember that your instructor is the final authority on the details and requirements of your paper. Read through all instructions, and have a conversation with your instructor at the start of the project to determine his or her preferences and requirements. Have a cheat sheet or checklist of this information; don't expect yourself to remember all year every question you asked or instruction you were given.

- What Is a Bibliography?

- Turabian Style Guide With Examples

- What Is a Citation?

- Formatting Papers in Chicago Style

- Definition of Appendix in a Book or Written Work

- Bibliography: Definition and Examples

- What Are Endnotes, Why Are They Needed, and How Are They Used?

- Tips for Typing an Academic Paper on a Computer

- How to Organize Research Notes

- MLA Style Parenthetical Citations

- What's the Preferred Way to Write the Abbreviation for United States?

- How to Write a Research Paper That Earns an A

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Formatting APA Headings and Subheadings

- MLA Bibliography or Works Cited

- Writing an Annotated Bibliography for a Paper

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

- Senior Theses

Doing a senior thesis is an exciting enterprise. It’s often the first time students are engaging in truly original research and trying to develop a significant contribution to a field of inquiry. But as joyful as an independent research process can be, you don’t have to go it alone. It’s important to have support as you navigate such a large endeavor, and the ARC is here to offer one of those layers of support.

Whether or not to write a senior thesis is just the first in a long line of questions thesis writers need to consider. In addition to questions about the topic and scope of your thesis, there are questions about timing, schedule, and support. For example, if you are collecting data, when should data collection start and when should it be completed? What kind of schedule will you write on? How will you work with your adviser? Do you want to meet with your adviser about your progress once a month? Once a week? What other resources can you turn to for information, feedback, and support?

Even though there is a lot to think about and a lot to do, doing a thesis really can be an enjoyable experience! Keep reminding yourself why you chose this topic and why you care about it.

Tips for Tackling Big Projects:

Break the process down into manageable chunks.

- When you’re approaching a big project, it can seem overwhelming to look at the whole thing at once, so it’s essential to identify the smaller steps that will move you towards the completed project.

- Your adviser is best suited to help you break down the thesis process with field-specific advice.

- If you need to refine the breakdown further so it makes sense for you, schedule an appointment with an Academic Coach . An academic coach can help you think through the steps in a way that works for you.

Schedule brief writing sessions at regular times.

- Pre-determine the time, place, and duration.

- Keep it short (15 to 60 minutes).

- Have a clear and reasonable goal for each writing session.

- Make it a regular event (every day, every other day, MWF).

- time is not wasted deciding to write if it’s already in your calendar;

- keeping sessions short reduces the competition from other tasks that are not getting done;

- having an achievable goal for each session provides a sense of accomplishment (a reward for your work);

- writing regularly can turn into a productive habit.

Create accountability structures.

- In addition to having a clear goal for each writing session, it's important to have clear goals for each week and to find someone to communicate these goals to, such as your adviser, a “thesis buddy,” your roommate, etc. Communicating your goals and progress to someone else creates a useful sense of accountability.

- If your adviser is not the person you are communicating your progress to on a weekly basis, then request to set up a structure with your adviser that requires you to check in at less frequent but regular intervals.

- Commit to attending Accountability Hours at the ARC on the same day every week. Making that commitment will add both social support and structure to your week. Use the ARC Scheduler to register for Accountability Hours.

- Set up an accountability group in your department or with thesis writers from different departments.

Create feedback structures.

- It’s important to have a means for getting consistent feedback on your work and to get that feedback early. Work on large projects often lacks the feeling of completeness, so don’t wait for a whole section (and certainly not the whole thesis) to feel “done” before you get feedback on it!

- Your thesis adviser is typically the person best positioned to give you feedback on your research and writing, so communicate with your adviser about how and how often you would like to get feedback.

- If your adviser isn’t able to give you feedback with the frequency you’d like, then fill in the gaps by creating a thesis writing group or exploring if there is already a writing group in your department or lab.

- The Harvard College Writing Center is a great resource for thesis feedback. Writing Center Senior Thesis Tutors can provide feedback on the structure, argument, and clarity of your writing and help with mapping out your writing plan. Visit the Writing Center website to schedule an appointment with a thesis tutor .

Accept that there will be some anxious moments.

- To reduce this source of anxiety, try keeping a separate document where you jot down ideas on how your research questions or central argument might be clarifying or changing as you research and write. Doing this will enable you to stay focused on the section you are working on and to stop worrying about forgetting the new ideas that are emerging.

- You might feel anxious when you realize that you need to update your argument in response to the evidence you have gathered or the new thinking your writing has unleashed. Know that that is OK. Research and writing are iterative processes – new ideas and new ways of thinking are what makes progress possible.

- Breaking down big projects into manageable chunks and mapping out a schedule for working through each chunk is one way to reduce this source of anxiety. It’s reassuring to know you are working towards the end even if you cannot quite see how it will turn out.

- It may be that your thesis or dissertation never truly feels “done” to you, but that’s okay. Academic inquiry is an ongoing endeavor.

Focus on what works for you.

- Just because your roommate wrote 10 pages in a day doesn’t mean that’s the right pace or strategy for you.

- If you are having trouble figuring out what works for you, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach , who can help you come up with daily, weekly, and semester-long plans.

Use your resources.

- There’s a lot of the thesis writing process that has to be done independently, but there are also a lot of free resources at Harvard to help you do the work.

- If you’re having trouble finding a source, email your question or set up a research consult via Ask a Librarian .

- If you’re looking for additional feedback or help with any aspect of writing, contact the Harvard College Writing Center . The Writing Center has Senior Thesis Tutors who will read drafts of your thesis (more typically, parts of your thesis) in advance and meet with you individually to talk about structure, argument, clear writing, and mapping out your writing plan.

- If you need help with breaking down your project or setting up a schedule for the week, the semester, or until the deadline, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach .

- If you would like an accountability structure for social support and to keep yourself on track, come to Accountability Hours at the ARC.

Accordion style

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Note-taking

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Senior Thesis Writing Guides

The senior thesis is typically the most challenging writing project undertaken by undergraduate students. The writing guides below aim to introduce students both to the specific methods and conventions of writing original research in their area of concentration and to effective writing process.

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

- Course-Specific Writing Guides

- Disciplinary Writing Guides

- Gen Ed Writing Guides

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, preparing for a senior thesis.

Every year, a little over half of Harvard’s senior class chooses to pursue a senior thesis. While the senior thesis looks a little different from field to field, one thing remains the same: completion of a senior thesis is a serious and challenging endeavor that requires the student to make a genuine intellectual contribution to their field of interest.

The senior thesis is a significant task for students to undertake, but there is a variety of support resources available here at Harvard to ensure that seniors can make the best of their senior thesis experience.

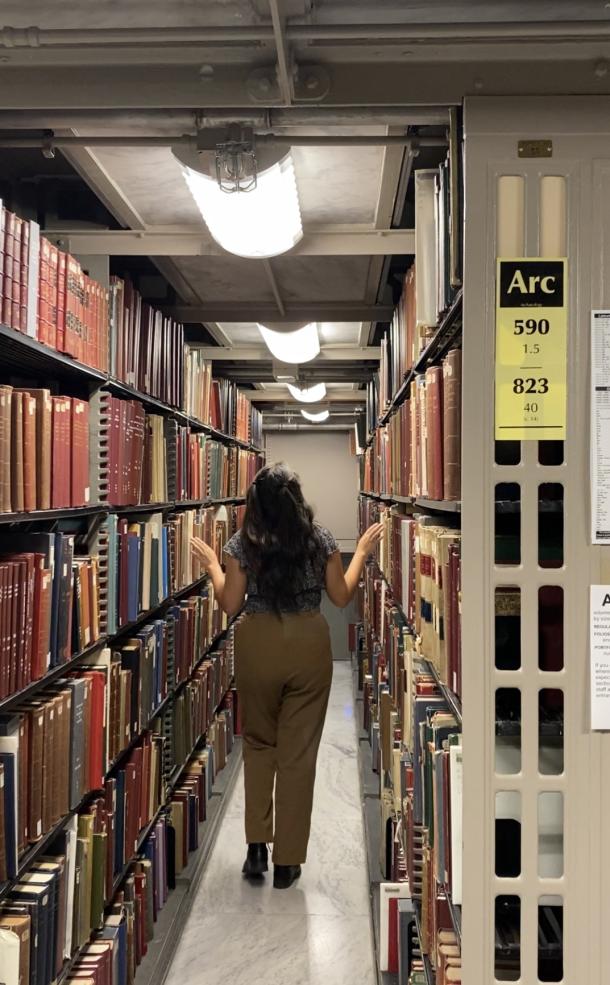

Wandering the library stacks at Widener.

I do most of my research in Widener Library. Hannah Martinez

As a rising senior in the History department, I am planning on pursuing a senior thesis on the history and use of the SAT in college admissions, and I am using the following support systems and resources to research and write my thesis:

- Staff at the History department. Every student within the department is assigned an academic advisor, who is a graduate student studying History at Harvard and knows the support available within the department. My academic advisor has helped me throughout the thesis process by connecting me with potential faculty members to advise my thesis and pick classes with a lighter course load so I can focus on completing my thesis. The Director of Undergraduate Studies in History (the History DUS) has also been pivotal in making sure that I attended a lot of information sessions about what the thesis looks like and how much of a commitment it is.

- History faculty at Harvard! All of my professors in History have been incredibly helpful in teaching me how to write like a historian, how to use primary sources in my essays, and how to undertake a serious research project over the course of a semester. Of course, while the thesis will require me to go far beyond what I’ve ever done before, I feel prepared to take on such a task because of the unwavering support from the History faculty. My mentor, Emma Rothschild, is one of the members of the faculty who has been invaluable in encouraging me to go as far as I am able.

- And last but certainly not least: funding. Funding, whether in term-time of the summer before senior year, is crucial towards making the senior thesis possible. Harvard’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships is dedicated to connecting Harvard students to funding sources across the university so they can pursue their research and get paid for it. This summer, I received a grant from the university of almost $2,000 so I am able to travel to libraries, buy books, and potentially take time off of work and do my research. Without such a grant, it would be incredibly difficult for me to do enough research so I can write a thesis this upcoming fall.

As you can see, there are multiple avenues for support and resources here at Harvard so your senior thesis is as easy as possible. While the senior thesis is still a challenging project that will take up a lot of time, Harvard’s resources make it possible for senior students to do their very best in all of their theses. I’m excited to start writing this fall!

Student Voices

How the mellon mays undergraduate fellowship propelled my love of archives into academic aspirations.

Beginning my senior thesis: A personal commitment to community and justice

Amy Class of '23 Alumni

Exploring Research at Harvard: Social Studies Edition

Olga Class of '22 Alumni

Yale College Undergraduate Admissions

- A Liberal Arts Education

- Majors & Academic Programs

- Teaching & Advising

- Undergraduate Research

- International Experiences

- Science & Engineering Faculty Features

- Residential Colleges

- Extracurriculars

- Identity, Culture, Faith

- Multicultural Open House

- Virtual Tour

- Bulldogs' Blogs

- First-Year Applicants

- International First-Year Applicants

- QuestBridge First-Year Applicants

- Military Veteran Applicants

- Transfer Applicants

- Eli Whitney: Nontraditional Applicants

- Non-Degree & Alumni Auditing Applicants

- What Yale Looks For

- Putting Together Your Application

- Selecting High School Courses

- Application FAQs

- First-Generation College Students

- Rural and Small Town Students

- Choosing Where to Apply

- Inside the Yale Admissions Office Podcast

- Visit Campus

- Virtual Events

- Connect With Yale Admissions

- The Details

- Estimate Your Cost

- QuestBridge

Search form

Writing a senior thesis: is it worth it.

Before coming to Yale, I thought a thesis was the main argument of a paper. I quickly learned that an undergraduate thesis is about fifty times harder and fifty pages longer than any thesis arguments I wrote in high school. At Yale, every senior has some sort of senior requirement, but thesis projects vary by department. Some departments require students to do a semester-long project, where you write a longer paper (25-35 pages) or expand, through writing, the research you’ve been working on (mostly applies to STEM majors). In some departments you can take two senior seminars and complete a longer project at the end of the semester. And other departments have an option to complete a year-long thesis: you spend your senior year (and in some cases your junior year), intensely researching and writing about a topic you choose or create yourself.

Both my departments––English and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration––offer all three of these options, and each student decides what they think is best for them. As a double major, I had the additional option to write an even longer thesis combining both my majors, but that seemed like way too much work––especially since I would have to take two senior thesis classes at the same time. Instead, I chose a year-long thesis for ER&M that combined my literary interests with various theoretical frameworks and the two senior seminars for English. This spring I’m taking my second seminar. Really, I chose the option to torture myself for a whole year, the end result being a minimum of 50 pages of innovative thinking and writing. I wanted to rise to the challenge, proving to myself I could do it. But there also seemed to be the pressure of “this is what everyone in the major does,” and a “thesis is proof that you actually learned.” Although these sentiments influenced my decision to complete a thesis, I know a long research paper does not validate my education or work as a scholar the last four years. It is not the end all be all.

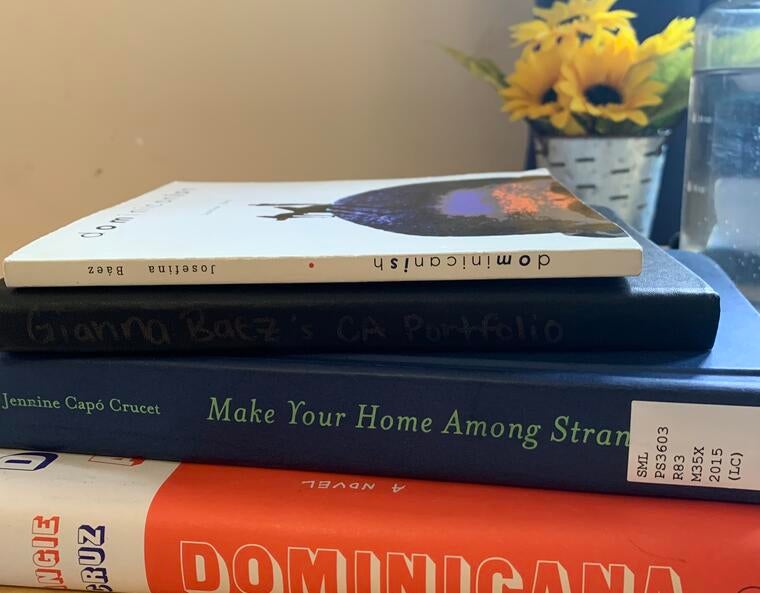

My senior thesis focuses on Caribbean literature - specifically, two novels written by Caribbean women that really look at what it means to come from an immigrant family, to move, and to find yourself in completely new spaces. These experiences are all too relatable to my own life as a second-generation woman of color with immigrant parents enrolled at Yale. In my writing, I focus on how these women make sense of “home” (a very broad and complicated topic, I know), and what their stories tell us about the diasporic experience in general. The project is very personal to me, and I chose it because I wanted to understand my family’s history and their task in making “home” in the U.S., whatever that means. But because it’s so personal, it’s also been really difficult. I’ve experienced a lot of writer’s block or often felt unmotivated and judgmental towards my work. I’ve realized how difficult it is to devote your time and energy to such a long process––not only is it research heavy, but you have to write and rewrite drafts, constantly adjusting to make sure you’re being as clear as possible. Really, writing a thesis is like writing a portion of a book. And that’s crazy! You’re writing two or three whole chapters of academic work as an undergraduate student.

The process is definitely not for everyone, and I’ve certainly thought “Why did I want to do this again?” But what’s really kept me going is the support from my advisors and friends. The ER&M department faculty does an amazing job of providing us mentorship, revisions, and support throughout the process; my advisor has served as my editor but also the person who reminds me most that this work is important, as I often forget that. It also helps to have many friends and people in the major also writing their theses. I’ve found different spaces to just have a thesis study hall or working time, with other people also struggling through. Recently, I submitted my first full draft (note: it was kind of unfinished but it’s okay because it’s a draft!), and it was crazy to think that I wrote 50+ pages, most of which are just my own original thoughts and analysis on two books that have almost no scholarship written about them. It was a relief for sure. This week I will be taking a full break from it, but it reminded me of why I began this journey. It reminded me of all the people who’ve supported me along the way, and how I really couldn’t have done it without them. And now, I’m really looking forward to how good it will feel to turn in my fully written thesis mid-April. I’ve realized that this project shouldn’t be about making it good for Yale’s standard, but for myself, for my family, and for the people who believe in this work as much as I do.

More Posts by Gianna

Senior Bucket List: All the things I had to do before I left Yale/New Haven

Meet Rhythmic Blue!

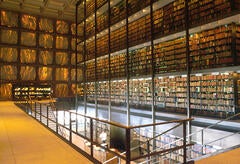

Medieval Manuscripts and the Beinecke Library

How I Navigated My Double Major

Rating Boba in New Haven

Quarantine Birthdays

Welcome to the Trumbutt!!!!

Yale IMs: Intramural Sports #MOORAH

Reimagining Virtual Relationships

Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time

For his senior thesis, Jordan Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese major, produced a nonfiction book of travel writing about the people and places along Colombia’s main river, the Magdalena.

Embracing the Classics to Inform Policymaking for Public Education

For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address inequities in the classroom.

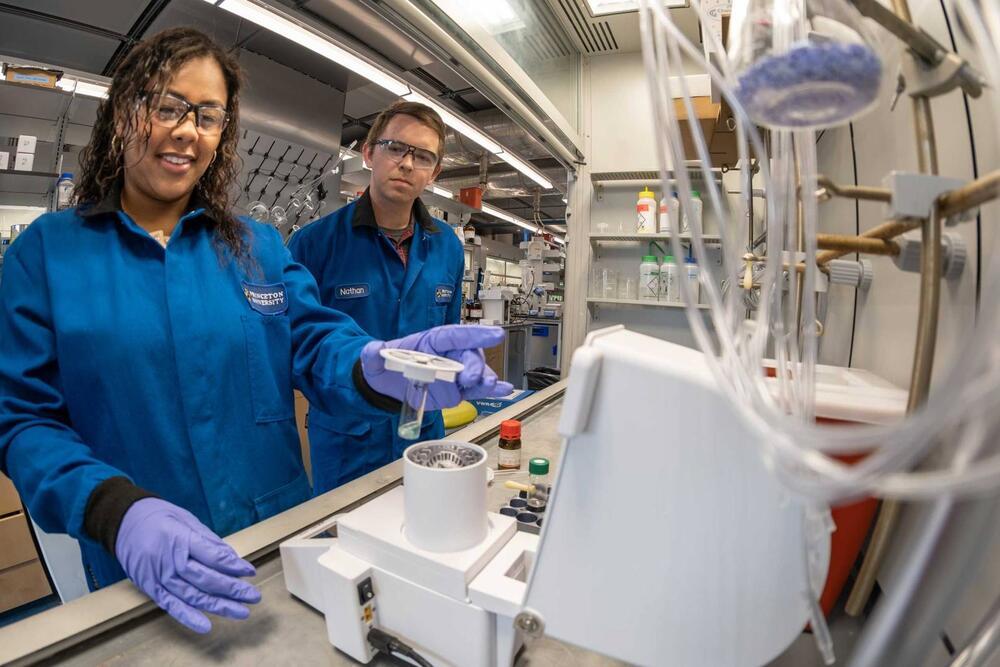

Creating A Faster, Cheaper and Greener Chemical Reaction

One way to make drugs more affordable is to make them cheaper to produce. For her senior thesis research, Cassidy Humphreys, a chemistry major with a passion for medicine, took on the challenge of taking a century-old formula at the core of many modern medications — and improving it.

The Humanity of Improvisational Dance

Esin Yunusoglu investigated how humans move together and exist in a space — both on the dance floor and in real life — for the choreography she created as her senior thesis in dance, advised by Professor of Dance Susan Marshall.

From the Blog

The infamous senior thesis, revisiting wwii: my senior thesis, independent work in its full glory, advisers, independent work and beyond.

- Sustainability

Elements of a Senior Thesis

The particulars will vary from project to project, but a Politics thesis typically includes the following elements.

Choosing the Thesis Topic

The topic is the general subject matter for your thesis. This includes the geographic area you want to study, the particular phenomenon you wish to study or the theoretical questions you wish to explore. We strongly recommend that you choose a topic that builds on work you have done earlier in your academic career. Perhaps you want to study the Polish electoral system, and you know something about Poland but nothing about the theoretical literature on electoral systems, or perhaps you know the literature on electoral systems but nothing about Poland. That’s ok. If you know nothing about either Poland or the literature on electoral systems, we encourage you to choose another topic. In your introduction, you might introduce your topic, discuss why it is important and how you came to be interested in it.

The Research Question

Coming up with a good research question is one of the most difficult steps in writing a good thesis. The question must be focused enough such that you can hope to answer it in a semester’s work. Also, the question must be placed in the context of existing literature. You cannot ask the same question that others have done without exploring first what these others have argued before you. Then you might find an issue they didn’t discover, or you may wish to see if their conclusions extend to different cases. For example, a question that seeks to explain why the countries in the European Union approach multilateral institutions differently than the United States does is probably too broad. A question that seeks to explore particular hypotheses, such that the differentials in US and European power explain these different positions, is much more workable. You might also frame a research question to address a debate among scholars within the literature. Above all, the answer to the question should be of interest to other scholars and you should be able to articulate its significance.

The Literature Review

Your question often comes out of an understanding of the scholarly literature. The literature review section of your thesis is where you consider existing literature on a particular topic and analyze how the authors came to the conclusion they did. What were their assumptions? What did they decide to examine and how did they examine it? What are their central findings or conclusions that inform your research question and theoretical framework? What questions or evidence did they leave out? The literature review helps you explain how and why your question contributes to existing knowledge on the topic. A literature review is a critical assessment of scholarship, but one that is focused. The critiques you raise about the work of other scholars ought to be ones you can address or resolve in your study.

Your Approach to Evidence

This is a statement and justification of how you will seek to answer your question. What cases will you be studying and why? What texts will you consider, and with what lens will you analyze them? What kind of evidence will you be using and how will you use it? What questions will you ask in interviews? How will you analyze roll call votes and why? What are the variables you will examine when you look at historical literature, and why do you think those variables are useful? Make sure your research strategy is linked to your question. If you engage in hypothesis testing, then be clear about how you derive your hypotheses from your theoretical framework and how you will then test them. Your thesis may also include creative work, in addition to evidence, such as your own fiction, poetry, dance or visual art.

Evidence and Analysis

These sections present your analysis of the evidence and whatever tentative conclusions you reach on the basis of this evidence. How you organize these sections, and how many sections you have, will depend on the nature of your question and your research strategy.

A short section of about eight pages or so that restates your question and summarizes your conclusions. Then the conclusion should outline the implications of your findings both for the existing literature on the topic and possibly also for policy. If the analysis is positive in nature – that is, identifying and testing hypotheses about political phenomena – then this is also a good occasion to consider the normative implications of your findings. Finally, you should discuss issues that arose that you could not answer do to a lack of resources or time, or even interest, and what further research could be done.

Future Students

Majors and minors, course schedules, request info, application requirements, faculty directory, student profile.

- Utility Menu

- Meet with an Adviser

Senior Thesis Formatting Guidelines

Contents and form.

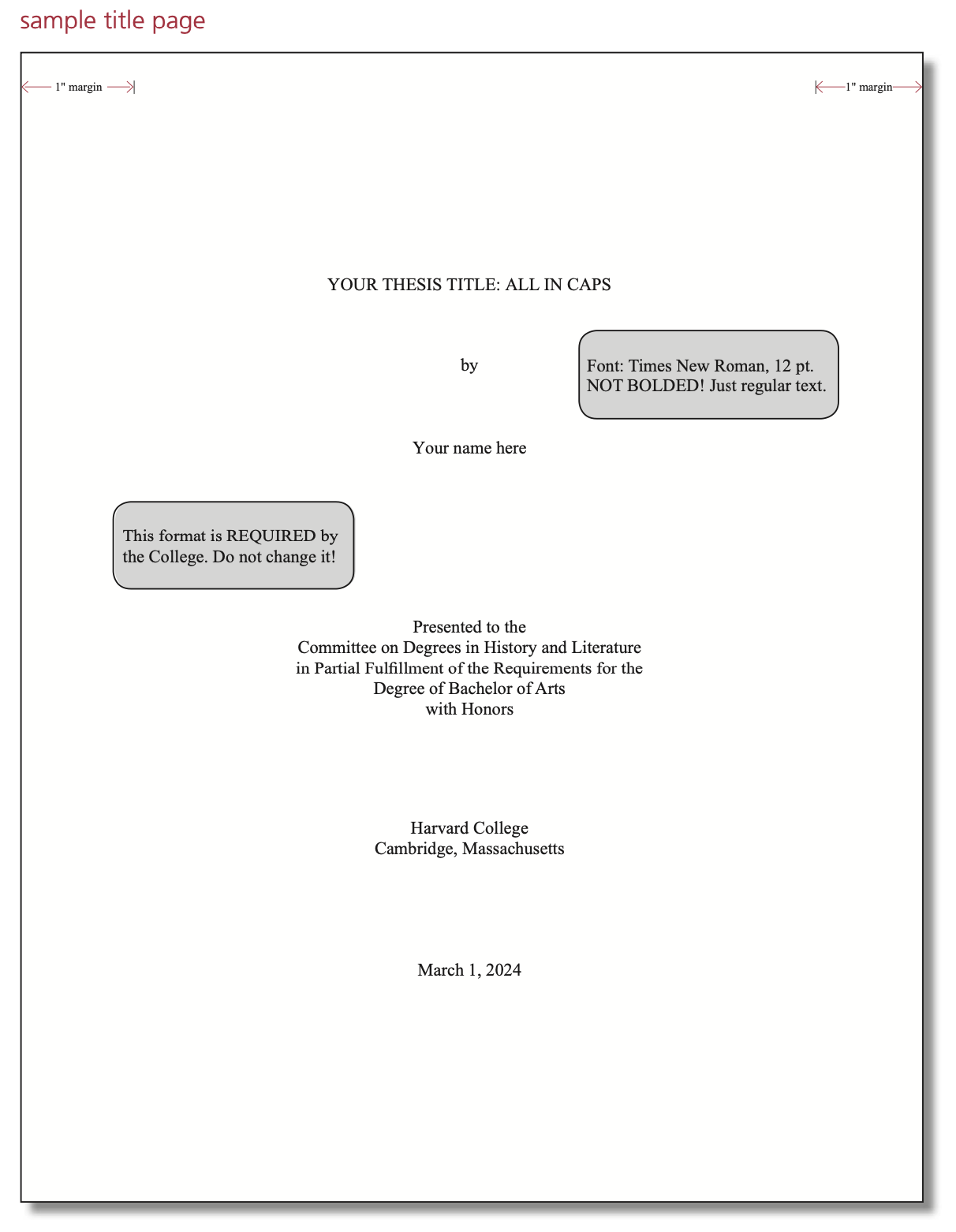

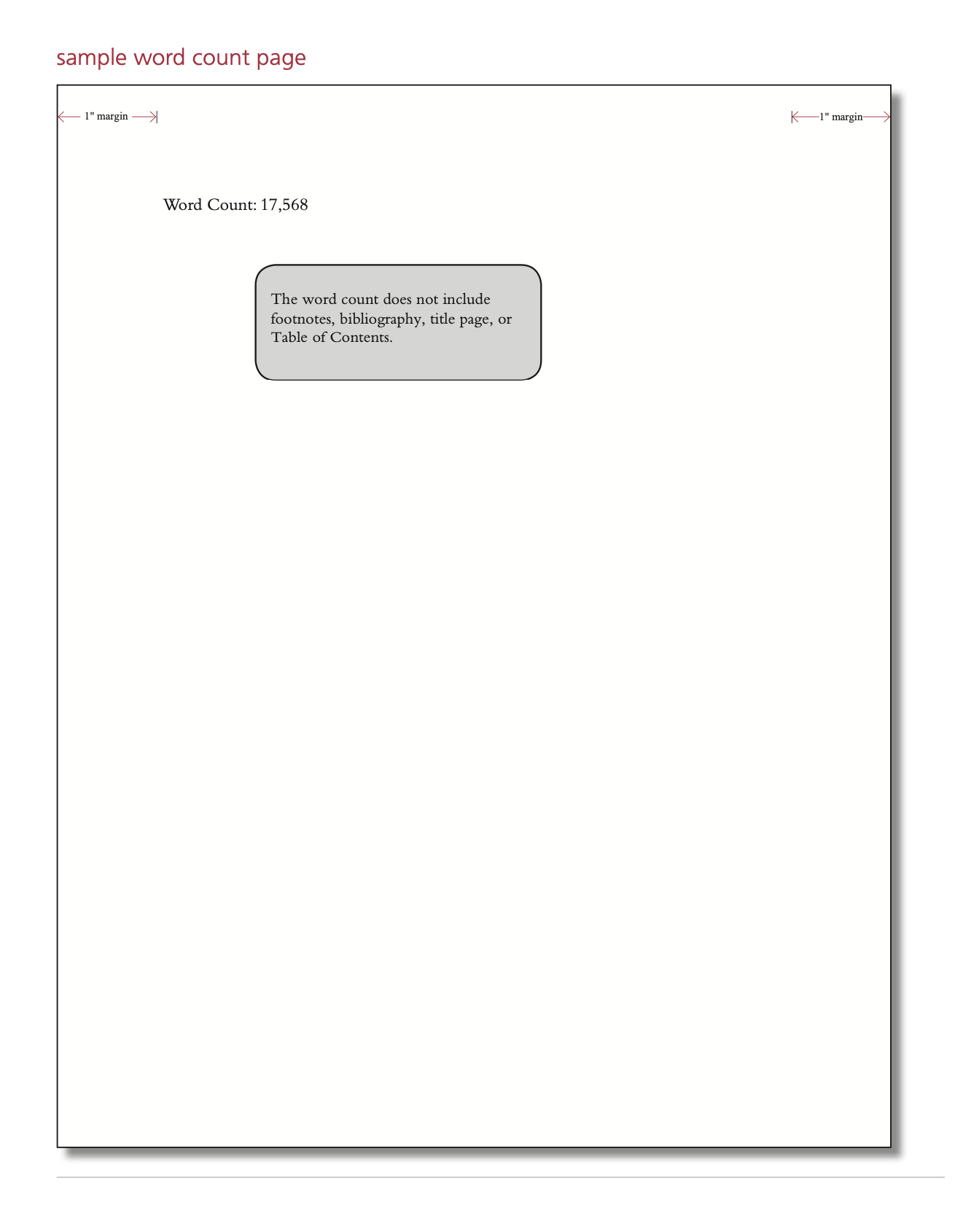

Length : The required length is between 10,000 and 20,000 words, not counting notes, bibliography, and appendices. The precise length of the main body text must be indicated on the word count page immediately following the title page . If a student expects the thesis to exceed 20,000 words, the student’s tutor should consult the Director of Studies. Please note that students’ requests to exceed 20,000 words must go through their tutors and that these requests must be made in early February. Any extension of the thesis beyond the maximum must be justified by the nature of the topic, or sustained excellence in the treatment of the subject, or both. Theses that receive permission to exceed 20,000 words can still be penalized if readers do not think that the excess length is warranted.

Acknowledgments : Please do not include acknowledgments in your final copy of the thesis. If you wish, you can add acknowledgments after your thesis has been read. Readers prefer not to know who directed your thesis, lest they be somehow swayed by that knowledge.

Illustrations : Illustrations, also called figures, might include anything from a photograph to a printed advertisement to a map to a chart. Illustrations may be inserted in the body of your thesis or included in an appendix at the end. Writers often choose to reference an illustration in the body of text, signaling to readers to refer to a particular figure that’s being discussed by turning to a nearby page or to an appendix (e.g., “See Figure 1.”) The inclusion of illustrations in a senior thesis, which has a fairly circumscribed audience, falls under fair use, so you do not need permissions to reproduce illustrations in your thesis. However, all images should be accompanied by a caption that identifies the image and may include brief explanatory text. You may also use the caption to attribute the source where you found the illustration (e.g., a url or the name of the archive where you photographed the item), or you can cite the illustration in a footnote or endnote. You do not need to cite your images in your bibliography. For more detailed guidelines on including illustrations in your thesis, see The Chicago Manual of Style or the MLA Style Manual .

Format : Pages should be 8 1/2" x 11". Margins should be 1 inch, and pages should be numbered. Do not right-justify. The lines of type must be double-spaced, except for quotations of five lines or more, which should be indented and single-spaced.

Style : If you have questions beyond those covered on this page, consult the University of Chicago's A Manual of Style or the Modern Language Association's Style Manual . Kate L. Turabian's A Manual for Writers is a good, inexpensive, brief guide to Chicago style. The Expository Writing Program guide, Writing with Sources , is very useful.

Table of Contents : Every thesis requires a Table of Contents to guide the reader.

Quotations : Quotations of four lines or fewer, surrounded by quotation marks, may be incorporated into the body of the text. Longer extracts should be indented and single-spaced; they should not be included in quotation marks. Each full quotation should be accompanied by a reference. Follow the general practice in the best periodicals in your field, and be consistent. Foreign words that are not quotations should be underlined or italicized.

Appendices : An appendix provides additional material that helps support your argument and is too lengthy to be included as a footnote or endnote. Appendices might include images, passages from primary texts in a non-English language or in your translation, or archival material that is difficult to access. It is rare but perfectly acceptable for theses to include appendices, so make sure to discuss with your tutor whether an appendix makes sense for your project.

Notes : You may use either footnotes (at bottom of page), endnotes (at end of the thesis) or MLA style parenthetical notes. However, for a History & Literature thesis, Chicago style is generally better. Footnote or endnotes are properly used:

- To state precisely the source or other authority for a statement in the text, or to acknowledge indebtedness for insights or arguments taken from other writers. Quotations should be given when necessary.

- To make minor qualifications, to prevent misunderstanding, or otherwise to clarify the text when such statements, if put in the text, would interrupt the flow.

- To carry further some topic discussed in the text, when such discussion is needed but does not fit into the text.

Bibliography : You must append a list of works cited to your thesis. It's a good idea to compile your bibliography as you write, rather than try to put it together all at once at the end (there are very powerful bibliography programs available, such as Zotero and Endnote, that generate bibliographies automatically). The purpose of the bibliography is to be a convenience to your reader. In the works cited list, primary and secondary sources should be listed under separate headings.

- Sophomore Tutorial

- Junior Tutorial

- Senior Thesis

- Senior Oral Exam

- Courses That Count

- Language Requirement

- Summer Research Funding

- Study Abroad

- Joint and Double Concentrations

Sample Title Page

Sample Word Count Page

Thesis Format Template

Classical Studies

Senior Thesis & Senior Essay

A successful Senior Thesis or Essay will deal directly with primary sources (in the original language to the extent possible), show knowledge of and critical engagement with current scholarship on the subject, and present an original argument developed in response to these sources. The topic might grow out of an oral presentation given in a class, a visit to a monument or site during an overseas study program, or a desire to study in greater depth a set of texts already encountered in a classroom setting. Students thinking about a thesis may wish to look at the past theses in Downey House 115; see a list of recent thesis titles.

While the Senior Thesis is a two-semester project, the Senior Essay is a substantial one-semester research project undertaken in the context of an individual tutorial. It may be completed in either the fall or the spring semester of the senior year. Both should be considered serious academic undertakings and students should plan to begin research in the semester or summer which precedes it. While there is no prescribed minimum length, 30-40 pages is the typical range for an Essay and 70-80 pages for a Thesis. In order to write a thesis or essay, one must first secure the agreement of a departmental faculty member to serve as an advisor. In consultation with the advisor, the student should then outline the topic and compile a basic bibliography.

All students who intend to write a Senior Thesis are required to submit a thesis proposal to the Department by April 15 of the junior year. Students who wish to write a Senior Essay should submit their proposal to the Department by the end of the previous semester (April 15 for an essay to be written in the fall semester, November 15 for the spring).

The Proposal

The Senior Thesis or Essay proposal should be a clear and concise statement of the aims and scope of the project. It should include a description of the central topic or the question to be explored, the main primary sources to be considered, and a bibliography of major secondary sources that will be consulted. The student should also outline the analytical method to be used and any theoretical approaches that may be brought to bear on the topic under consideration. The proposal should be no more than 2-3pp. in length. The student must also include in the proposal the name of the faculty member who has agreed to serve as advisor for the thesis. Students on foreign study programs in the spring of the junior year should identify an advisor as soon as possible to ensure timely submission of their proposal.

Proposals will be considered by the departmental faculty. If the project is deemed appropriate in scope, depth and sophistication for a senior thesis, it will be approved. The student will be informed of the faculty's decision by May 1 (or Dec 1 for fall essay submissions). Appeals of that decision will not be considered, so it is extremely important that students work with a faculty member well in advance of the deadline to develop a suitable project.

Junior Spring (or Senior Fall for Spring Essay-writers): After consultation with the advisor, students submit proposals to the Department for approval. Submission dates are April 15 or November 15.

Summer before Senior Year : Research. This might include broad secondary reading, gathering of data or of bibliography, or a first reading of a text in the original Greek or Latin. Students may wish to look into summer seminars, language programs, or archaeological excavations that will provide skills, ideas, or data sets for a senior thesis.

Senior Fall: Register for the thesis/essay tutorial (For thesis: GRK,LAT, or CCIV 409; for the Essay: GRK, LAT, or CCIV 403). During regular meetings the advisor, in consultation with the student, will establish expectations for the completion of the project in stages. After discussion with the advisor, a student may wish to consult other members of the department whose expertise may be relevant to the thesis topic. Work in progress reports are due in January.

Senior Spring: Submit completed thesis in mid-April. The Honors College provides information about formatting theses for submission, including standards for paper, printing and binding. Students may not use departmental printers or copy machines for theses, but may seek the help or advice of the department for printing Greek or using illustrations. ITS provides a printing service.

Evaluation and Honors

In most cases, the faculty advisor alone reads the Senior Essay and assigns a grade for the tutorial. Students should not enter upon a Senior Essay project with the expectation of being considered for honors. Departmental Honors are normally reserved for students who write a thesis, although in extraordinary circumstances the department may elect to consider a senior essay for honors. For the Thesis, the evaluating committee will consist of the advisor, one additional faculty member within the department, and one faculty member from within or outside the department. The advisor and the student will discuss and choose the other readers in the spring, with the advisor responsible for contacting readers in other departments (unless both advisor and student agree that the student shall make the contact). Promptness is recommended in speaking to possible readers in departments like English and History, which typically have many theses to read within their own departments.

Committee members will receive the thesis soon after it is submitted to the Honors College in April. They will forward to the departmental chair written evaluations, including a recommendation for a grade, and a recommendation for Honors or High Honors, or a recommendation that Honors not be awarded. Sufficient time must be allowed for the chair to forward a recommendation about grade and Honors to the Honors College by the deadline. Each reader has the option of forwarding evaluations, or an edited (shortened or expanded) version of the evaluations, directly to the student, but the student should not be told the recommendation for Honors or grade. A thesis must receive a grade of B+ or better to receive departmental Honors, and A or better to receive departmental High Honors. If the readers' recommendations differ, the chair will discuss with them possibilities for compromise or, more rarely, use of an additional reader. A student who does not receive departmental Honors may and ordinarily will still receive credit for the thesis tutorials, if the advisor feels this is appropriate. When all decisions have been made about departmental Honors, the department chair or (with the chair's approval) the advisor shall inform the student about the decision regarding Honors and grade. The advisor shall give the student a course grade for the two terms of work on the thesis; this grade need not be the same as that awarded to the thesis. Often a grade of "X" will be recorded for work on a thesis in the fall, and grades for both 409 and 410 will be determined in the spring.

Students who have been awarded departmental High Honors for the thesis and who have completed all General Education expectations are eligible to be nominated by the department for University Honors. A very small number of Wesleyan students compete for University Honors each year; only a handful receives the prize. This recommendation should accompany the grade and recommendation for High Honors sent to the Honors College on the deadline mentioned above. Selected nominees for University Honors must qualify in an oral examination administered by the Honors Committee, which includes discussion of the thesis but which focuses on other areas of questioning designed to show the students' breadth of knowledge in all areas of the curriculum.

You are using a unsupported browser. It may not display all features of this and other websites.

Please upgrade your browser .

- How It Works

- PhD thesis writing

- Master thesis writing

- Bachelor thesis writing

- Dissertation writing service

- Dissertation abstract writing

- Thesis proposal writing

- Thesis editing service

- Thesis proofreading service

- Thesis formatting service

- Coursework writing service

- Research paper writing service

- Architecture thesis writing

- Computer science thesis writing

- Engineering thesis writing

- History thesis writing

- MBA thesis writing

- Nursing dissertation writing

- Psychology dissertation writing

- Sociology thesis writing

- Statistics dissertation writing

- Buy dissertation online

- Write my dissertation

- Cheap thesis

- Cheap dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help

- Pay for thesis

- Pay for dissertation

- Senior thesis

- Write my thesis

What Is A Senior Thesis And How To Write It?

First, what is senior thesis? A senior thesis is a written project where you use different hypotheses, theory, argument, or creative thinking. It is usual practice for most students to take this project work in the senior year of college or high school.

A senior thesis tends to be more demanding than a research paper in terms of the amount of work and the length of the write-up. However, it is less than the work required for any Master’s thesis.

Is a Senior Thesis Required?

It is understandable to want to know if a senior thesis is required. I mean, anyone would want to know just how important it is before choosing to dedicate much time to it.

Well, a senior thesis is not compulsory in every college/university, and neither is it compulsory for every course of study.

In general, you can write a senior thesis if you have an overall GPA of 3.2, are ending your junior year, and meet your departmental requirements. If a senior thesis is not a requirement for completing your degree, you may decide to write one for several reasons. Some benefits are:

- It will look good on your resume

- It will give you an opportunity for some independent research

- You get some experience managing your project, etc.

If you cannot commit to finishing a senior thesis, then you shouldn’t start it. But if you would like to write one, then we’ve got lots of senior thesis topics and ideas for you! You will also get to learn how to write a senior thesis in this article!

How To Write a Senior Thesis

Writing a senior thesis can be a lot easier if you know what to do. First, you need to choose the right adviser, select a topic you would like to work on, write a proposal, and get approved. Here are some things you need to know about writing your senior thesis.

A thesis proposal is a short overview of what your senior thesis papers will look like. This document carries detailed descriptions of your senior thesis topic. Your thesis proposal can be between 1 to 5 pages long and should carry any relevant information. The proposal will also carry a list of books you’ve used or that you intend to use during the writing of your senior thesis.