- Contributors : About the Site

Newgeography.com

- Urban Issues

- Small Cities

- Demographics

- © 2024 New Geography

- CONTRIBUTORS :

- PRIVACY POLICY

- Stay up to date:

Understanding Society

Daniel Little

The global city — Saskia Sassen

Saskia Sassen is the leading urban theorist of the global world. (Here are several prior posts that intersect with her work.) Her The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (1991) has shaped the concepts and methods that other theorists have used to analyze the role of cities and their networks in the contemporary world. The core ideas in her theory of the global city are presented in a 2005 article, “The Global City: Introducing a Concept” ( link ). This article is a convenient place to gain an understanding of her basic approach to the subject.

Key to Sassen’s concept of the global city is an emphasis on the flow of information and capital. Cities are major nodes in the interconnected systems of information and money, and the wealth that they capture is intimately related to the specialized businesses that facilitate those flows — financial institutions, consulting firms, accounting firms, law firms, and media organizations. Sassen points out that these flows are no longer tightly bound to national boundaries and systems of regulation; so the dynamics of the global city are dramatically different than those of the great cities of the nineteenth century.

Sassen emphasizes the importance of creating new conceptual resources for making sense of urban systems and their global networks — a new conceptual architecture, as she calls it (28). She argues for seven fundamental hypotheses about the modern global city:

- The geographic dispersal of economic activities that marks globalization, along with the simultaneous integration of such geographically dispersed activities, is a key factor feeding the growth and importance of central corporate functions.

- These central functions become so complex that increasingly the headquarters of large global firms outsource them: they buy a share of their central functions from highly specialized service firms.

- Those specialized service firms engaged in the most complex and globalized markets are subject to agglomeration economies.

- The more headquarters outsource their most complex, unstandardized functions, particularly those subject to uncertain and changing markets, the freer they are to opt for any location.

- These specialized service firms need to provide a global service which has meant a global network of affiliates … and a strengthening of cross border city-to-city transactions and networks.

- The economic fortunes of these cities become increasingly disconnected from their broader hinterlands or even their national economies.

- One result of the dynamics described in hypothesis six, is the growing informalization of a range of economic activities which find their effective demand in these cities, yet have profit rates that do not allow them to compete for various resources with the high-profit making firms at the top of the system. (28-30)

Three key tendencies seem to follow from these structural facts about global cities. One is a concentration of wealth in the hands of owners, partners, and professionals associated with the high-end firms in this system. Second is a growing disconnection between the city and its region. And third is the growth of a large marginalized population that has a very hard time earning a living in the marketplace defined by these high-end activities. Rather than constituting an economic engine that gradually elevates the income and welfare of the whole population, the modern global city funnels global surpluses into the hands of a global elite dispersed over a few dozen global cities.

These tendencies seem to line up well with several observable features of modern urban life throughout much of the world: a widening separation in quality of life between a relatively small elite and a much larger marginalized population; a growth of high-security gated communities and shopping areas; and dramatically different graphs of median income for different socioeconomic groups. New York, London, and Hong Kong/Shanghai represent a huge concentration of financial and business networks, and the concentration of wealth that these produce is manifest:

Inside countries, the leading financial centers today concentrate a greater share of national financial activity than even ten years ago, and internationally, cities in the global North concentrate well over half of the global capital market. (33)

This mode of global business creates a tight network of supporting specialist firms that are likewise positioned to capture a significant level of wealth and income:

By central functions I do not only mean top level headquarters; I am referring to all the top level financial, legal, accounting, managerial, executive, planning functions necessary to run a corporate organization operating in more than one country. (34)

These features of the global city economic system imply a widening set of inequalities between elite professionals and specialists and the larger urban population of service and industrial workers. They also imply a widening set of inequalities between North and South. Sassen believes that communications and Internet technologies have the effect of accelerating these widening inequalities:

Besides their impact on the spatial correlates of centrality, the new communication technologies can also be expected to have an impact on inequality between cities and inside cities. (37)

Sassen’s conceptual architecture maintains a place for location and space: global cities are not disembodied, and the functioning of their global firms depends on a network of activities and lesser firms within the spatial scope of the city and its environs. So Sassen believes there is space for political contest between parties over the division of the global surplus.

If we consider that global cities concentrate both the leading sectors of global capital and a growing share of disadvantaged populations (immigrants, many of the disadvantaged women, people of color generally, and, in the megacities of developing countries, masses of shanty dwellers) then we can see that cities have become a strategic terrain for a whole series of conflicts and contradictions. (39)

But this strategic contest seems badly tilted against the disadvantaged populations she mentions. So the outcomes of these contests over power and wealth are likely to lead, it would seem, to even deeper marginalization, along the lines of what Loic Wacquant describes in Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality ( link ).

This is a hugely important subject for everyone who wants to understand the dynamics and future directions of the globe’s mega-cities and their interconnections. What seems pressingly important for urbanists and economists alike, is to envision economic mechanisms that can be established that do a better job of sharing the fruits of economic progress with the whole of society, not just the elite and professional end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- What Is A Global City?

Cities are centers of innovation and businesses. They portray the economic, social, and political state of the country and its people. Cities are categorized differently depending on the role they play on the global scene. Although the city of Tokyo is the largest in the world with a population of about 38,000,000, it is considered an Alpha + city, one level below the cities of New York and London which are considered Alpha ++ cities. Other Alpha + cities include Shanghai, Tokyo, Dubai, Singapore, Hong Kong, Paris, and Beijing. To be considered a global city, an urban center must prove it enjoys a significant global advantage over other cities and serves as a hub within the world economic system. Initially, global cities were ranked depending on their size. Today, several other factors other than the size of the city are being considered. Amsterdam, Houston, Mexico City, Paris, São Paulo and Zurich have all grown to be global cities. These cities possess several similar characteristics including Home to several financial service providers and institutions, headquarters to large multinationals, dominate the trade and economy of their countries and are a major hub for air, land and sea transport. They are also centers of innovation, boast of well-developed infrastructure, large population of employed people and act as the centers of communication of global news.

Some Of The World's Best-Known Global Cities

According to the A.T. Kearney’s Global Cities Index 2017, New York outsmarted London as the world’s best-performing city while the latter ranked second. Paris, Tokyo and Hong Kong followed respectively. The city of San Francisco topped the Global Cities Outlook Index ahead of New York, Paris, London, and Boston respectively. New York was ranked the best city for business activities, and human capital. Paris topped the best cities for information exchange while London was rated the best city for a cultural experience. Washington, D.C. the best city for political engagements. Hon Kong boasts of being a global leader in air freights while Brussels boasts of being the best place to set up an embassy.

Reasons Of Increase In Global Cities

The increase in global cities is linked to the globalization of economies and the centralization of mass production within urban centers. The two factors have led to the emergence of networks of activities that seek to fulfill the service and financial requirements of multinationals. The cities grow to became global while other suffer deindustrialization or stagnation of their economies.

Criticisms Of Global Cities

Despite playing significant roles in the global economy, global city thesis has been known for being a threat to state-centric perspectives. These cities have been accused of focusing their reach to other global cities and neglecting cities within the national outreach. These cities are more connected to the outside world than to their domestic economy. Although they are interconnected and interdependent, global cities are always in a competitive state. The cities of New York and London have been trying to outwit each other as the global financial centers. Local governments have been keen to promote the global cities within their territories as either economic or cultural centers, and sites of innovation.

More in Politics

What are ‘Red Flag’ Laws And How Can They Prevent Gun Violence?

The Most and Least Fragile States

What is the Difference Between Democrats and Republicans?

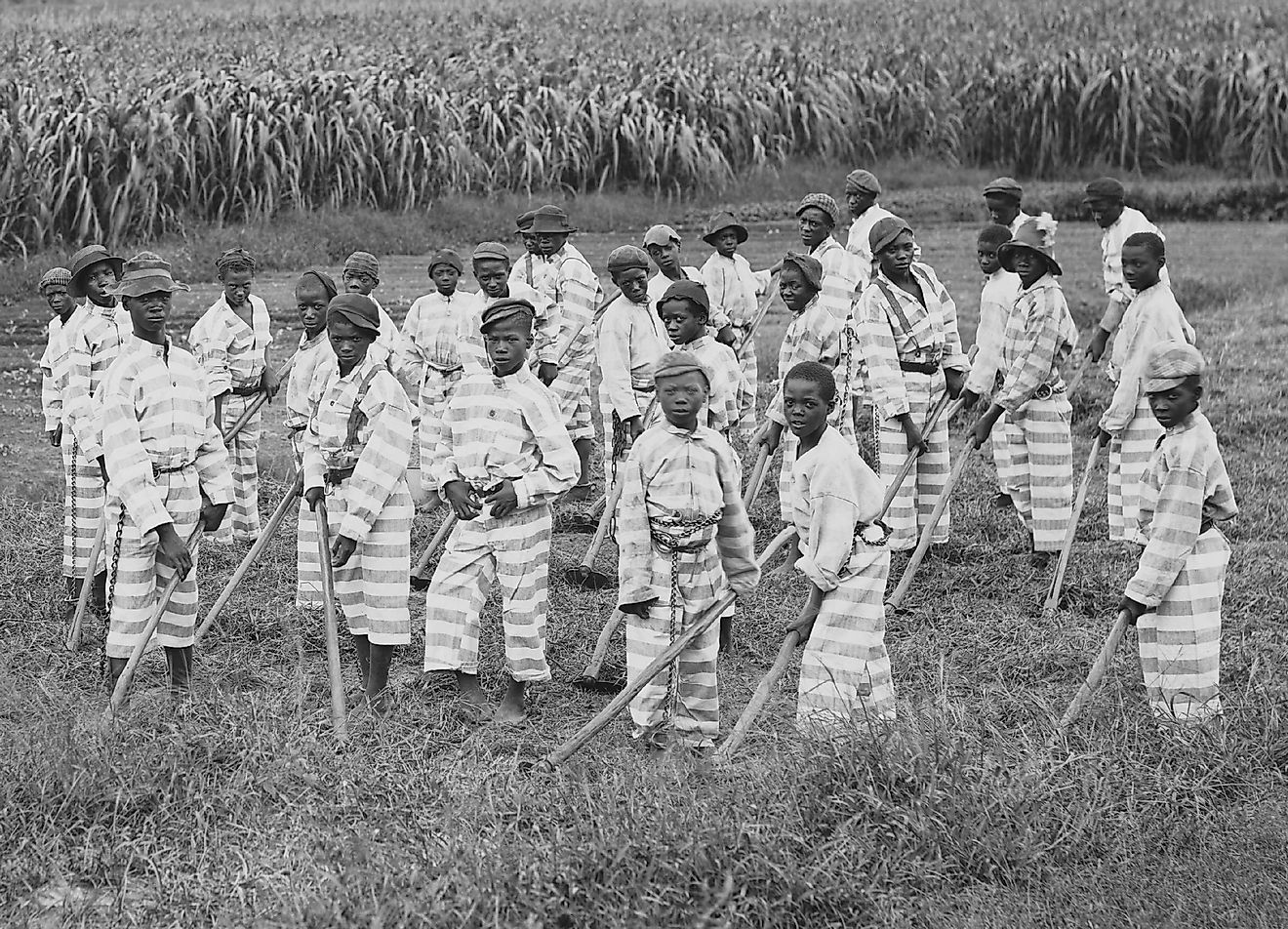

The Black Codes And Jim Crow Laws

Iroquois Great Law of Peace

United States-Iran Conflict

The War In Afghanistan

The United States-North Korea Relations

The importance of a global city

La mayor: 'we are the shot callers, the investors, the storytellers'.

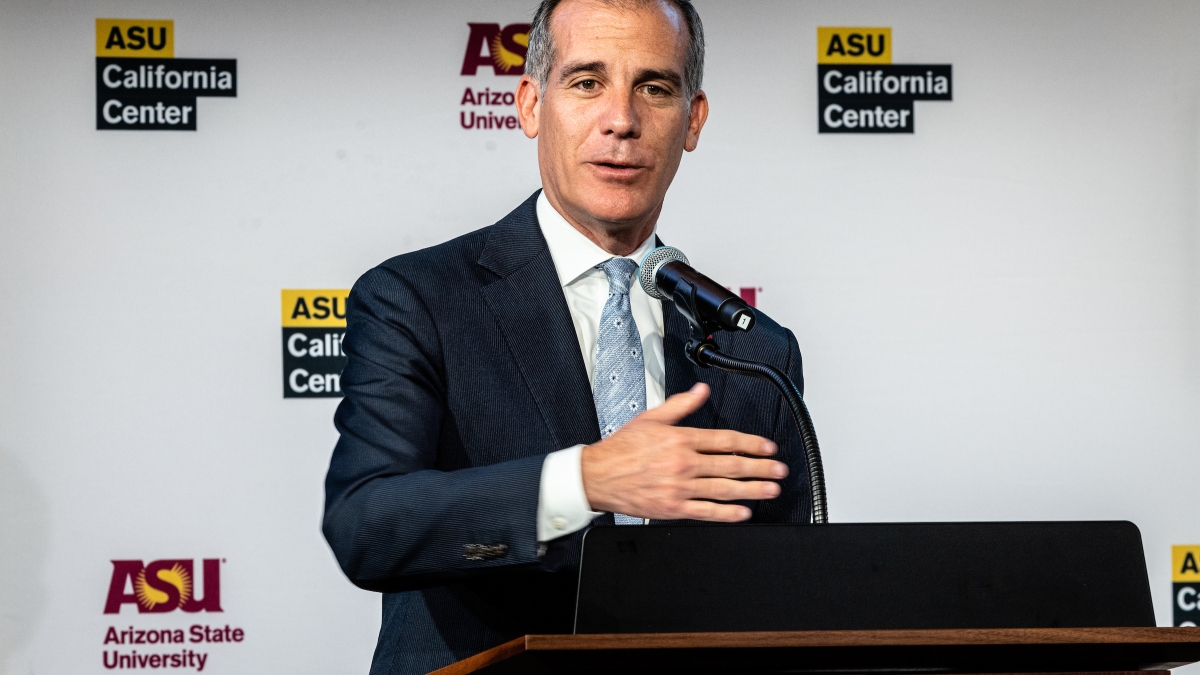

Editor's note: This story is part of our coverage of a weeklong series of events to mark ASU's expansion in California at the ASU California Center in downtown Los Angeles.

The pandemic highlighted the nimble ways that cities can quickly address problems that take national governments months to untangle, according to Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti.

In the early days of the pandemic, Garcetti jumped on a Zoom call – only his second ever – with 70 mayors from around the world, sharing information and best practices, such as how to prepare hospitals and whether to shut down.

“We talked to each other and the next day, we were implementing,” he said.

“Thousands if not tens of thousands of people are alive today because the cities of the world connected to each other.”

Garcetti spoke at an event on Monday morning called “Is LA Still a Global City?” at Arizona State University’s California Center in downtown Los Angeles. The talk is part of a weeklong celebration of ASU’s new site, based in the historic Herald Examiner Building.

Garcetti said that the important question for Los Angeles is: "What kind of global city are we?"

“Nothing about being global inherently makes you a fair city or a just city. It just makes you big,” he said.

Los Angeles, where 63% of the residents are immigrants or the children of immigrants, is at the crossroads of many of the world’s biggest industries, including not only the entertainment industry but also fashion, fine arts and new media, he said.

“We are the shot callers, the investors, the storytellers.

“Part of that is our universities, like ASU, which we welcome as an LA university joining the other great institutions,” Garcetti said.

A panel discussion followed Garcetti’s talk, in which ASU President Michael Crow emphasized the need for cities to maintain a vibrant urban core.

“We’re here because this is the place where the future is being outlined,” he said.

“You have to be downtown. We searched for years for this building. We wanted to be in downtown LA. It’s an essential location for human capital development.”

ASU President Michael Crow (second from left) speaks during the "Is LA Still a Global City?" panel discussion, following Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti's keynote speech, on Oct. 3, during a weeklong celebration of the ASU California Center in downtown Los Angeles. Joining the discussion is (from left to right) moderator Jessica Lall, CEO of the Central City Association; Stephanie Hsieh, president of Biocom CA; and Stephen Cheung, president of the World Trade Center, LA. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Steven Cheung, president of the World Trade Center in Los Angeles, said that the narrative of an influx of companies leaving California is not new.

“It’s true that it’s cheaper to do business elsewhere. But as we know, cheaper is cheaper, it’s not better,” he said.

“Companies are coming to LA not because it’s cheaper but because of the diversity of the population.

“The bottom line is that these companies still need to grow and find talent, and LA has one of the biggest and most diverse talent pools.”

The speakers emphasized the need for more education opportunities.

Stephanie Hsieh, executive director of Biocom CA and a biotech entrepreneur, said that nearly two-thirds of the workers the life sciences industry don’t have a bachelor’s degree.

“When it comes to workforce development, it starts in pre-K and it’s a continuum,” he said. “You have to get the kids in early.”

Hsieh said that with the Los Angeles Community College system, plus the Cal State and University of California systems, Los Angeles produces more PhDs in the life sciences than any other part of the country.

“But there’s a lot more we could be doing. How do we pull together to have people in our community see themselves in these positions?” she said.

The speakers noted that LA’s sprawling workforce weakens the ability to be collaborative.

“Prior to COVID, we were talking about downtown going through a renaissance,” Cheung said.

“There’s been a slight hiccup, but I think we can get back there. But also because of the transition to remote work, how do we look at the office space and attract a different type of collaboration?

“It can happen, but we need more leadership.”

Hsieh said that office space can be transformed.

“We have essentially a zero percent vacancy rate for wet lab space. We need to make room for that,” she said.

Crow said that of the top cities in the world, Los Angeles has the most potential.

“It’s the most economically diverse and has the highest concentration of forward-thinking industries,” he said.

“It also has a deep commitment to social transformation and justice. All the momentum is here.”

Top photo: Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti answers the question “Is LA Still a Global City?” during a keynote speech on Oct. 3, during a weeklong celebration of the ASU California Center in the historic LA Herald Examiner Building. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Arts, humanities and education

The Design School shines at interior design conference

The Interior Design Educators Council (IDEC) held its annual conference this March in New York City, welcoming interior design leaders who presented research, networked and learned about the latest…

Deputy director of ASU film school named one of 2024’s Influential Latinos in Media

Peter Murrieta is celebrating a particularly meaningful achievement: The deputy director of The Sidney Poitier New American Film School at Arizona State University has been named among the Imagen…

Visiting scholar takes gaming to the next level

Gaming — whether it be a video game, a mobile app or even a board game with family — can be serious business, with complex impacts in the real world. Arizona State University alum Kishonna L. Gray,…

Global Cities: Introducing the 10 Traits of Globally Fluent Metro Areas

Subscribe to the brookings metro update, brad mcdearman and brad mcdearman nonresident senior fellow - brookings metro joseph parilla joseph parilla senior fellow & director of applied research - brookings metro @joeparilla.

June 24, 2013

Swift global integration, the rapid expansion of a global consumer class, and the rise of urban regions as the engines of global economic growth have ushered in a new era. The global economy no longer revolves around a handful of dominant states and their national urban centers. This fundamental shift has both challenged the United States with greater global competition but also offered the prospect of all U.S. metropolitan areas to benefiting from engaging in growing markets abroad.

Aware of the enormous untapped opportunities offered through trade and global engagement, many U.S. metropolitan leaders are abandoning their path dependent focus on the U.S. market by improving their region’s global fluency. Our new report, “ The Ten Traits of Globally Fluent Metro Areas ,” defines global fluency as the level of global understanding, competence, practice, and reach that a metro area exhibits to facilitate progress toward its desired economic future.

In this report, we specifically isolate the 10 key traits associated with cities that have achieved global success. Many of these traits align with the key inputs to economic competitiveness: distinct specializations, infrastructure, human capital and innovation, capital investment, and good governance to name a few. But the list begins with Leadership with a Worldview because having a broad worldview enables regional leaders to be intentional in evaluating and leveraging all their other traits.

Over the next 10 weeks, starting today, a Brookings expert will post a blog related to one of the ten traits, presented in sequential order. Together, these traits provide one framework for metropolitan leaders to gauge their global starting point. The 10 traits below have proven to be particularly strong determinants of a metro area’s ability to succeed in global markets, manage the negative consequences of globalization, and better secure its desired economic future. The most successful cities are those that have a long-term outlook and achieve some level of integration between many of the traits.

- Leadership with a Worldview – Local leadership networks with a global outlook have great potential for impact on the global fluency of a metro area.

- Legacy of Global Orientation – Due to their location, size, and history, certain cities were naturally oriented toward global interaction at an early stage, giving them a first mover advantage.

- Specializations with Global Reach – Cities often establish their initial global position through a distinct economic specialization, leveraging it as a platform for diversification.

- Adaptability to Global Dynamics – Cities that sustain their market positions are able to adjust to each new cycle of global change.

- Culture of Knowledge and Innovation – In an increasingly knowledge-driven world, positive development in the global economy requires high levels of human capital to generate new ideas, methods, products, and technologies.

- Opportunity and Appeal to the World – Metro areas that are appealing, open, and opportunity-rich serve as magnets for attracting people and firms from around the world.

- International Connectivity – Global relevance requires global reach that efficiently connects people and goods to international markets through well-designed, modern infrastructure.

- Ability to Secure Investment for Strategic Priorities – Attracting investment from a wide variety of domestic and international sources is decisive in enabling metro areas to effectively pursue new growth strategies.

- Government as Global Enabler – Federal, state, and local governments have unique and complementary roles to play in enabling firms and metro areas to “go global.”

- Compelling Global Identity – Cities must establish an appealing global identity and relevance in international markets not only to sell the city, but also to shape and build the region around a common purpose.

Related Content

Brad McDearman, Greg Clark, Joseph Parilla

October 29, 2013

Brad McDearman

August 23, 2013

Amy Liu, Joseph Parilla

July 15, 2013

Related Books

Xavier de Souza Briggs William Julius Wilson

July 21, 2005

David F. Damore, Robert E. Lang, Karen A. Danielsen

October 6, 2020

Timothy H. Edgar

August 29, 2017

Brookings Metro

Muhammad Mustapha Gambo

August 15, 2023

Anthony F. Pipa, Kait Pendrak

June 28, 2023

Online only

9:30 am - 10:30 am EDT

innsbruck university press

Globalization and the city.

Introduction

Texte intégral.

1 It is often said that the world is turning into a “global village”. In reality, it is much more a “global city”: today, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities (although often under poor conditions), and many metropolises of the world are much more economically productive and significant with respect to global networks than most of the world’s states. In addition, these cities look increasingly alike, shaping a global space which is more and more indistinguishable between continents. Thus the modern city is the primary manifestation of globalization today, and its very essence is a global network of multidimensional spaces of congestion that both describes and shapes it.

2 The relevance of cities is nothing but new. While there were phases and places in history, when and where cities were not particularly important, and as a rule, only a small fraction of the population lived in these settlements, the history of civilization as we know it is very much connected to cities. From ancient to medieval and modern times, and from China, India and Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean, Europe and Mesoamerica, cities have been a recurrent phenomenon, and still archeology finds further evidence for large and hitherto undocumented – albeit not totally unexpected – settlements in distant periods and places. Hence, cities were essential for culture and civilization; they allowed a centralization of power and knowledge, and they were crucial for the division of labor and for organizing the demand of the people, on which economic development rests. And if we adopt a view of globalization that allows for a history in the longue durée , then cities emerge as the places people traveled to and from, where people exchanged news and goods, and where people could develop a view of a wider world, particularly if the city was located at the sea-shore.

1 A very recent exception is Global Cities , a large-scale collective volume by Taylor et al. (2012).

3 Hence, as places of intense and continuous interactions, cities are the locations par excellence where global history takes place, and we must study the history of cities in connection with the history of globalization from this perspective. Interestingly, although we can look back on twenty years of manifold globalization debates and shelves of books about the topic, this has hardly been done so far. 1 Hence, we lack orientation. One reason for that is, of course, methodological: it is simply impossible to fully grasp the complexities of a global social system that incorporates about seven billion individuals and a lot of collectives that are organized in different hierarchies and networks, all of them interwoven. But there are also two ways out of this dilemma: the first is to study the emergence of globalization in its various dimensions historically to identify the characteristics relevant for change and to understand the path-dependence of the process in order to comprehend recent developments and to contextualize them properly in the form of a meta-narrative; the second is to collect data about what is “really” going on, recently as well as historically, to get an idea of the structure and practical constraints of human action and choices at the micro level as well. Both help us make (more) sense of the alleged chaos of human existence.

2 See Friedman (1986), Sassen (1991, 1994), and Castells (1996, 2004).

- 3 Braudel (1986) particularly referred to Venice, Antwerp, Genoa and Amsterdam as cities that shaped (...)

4 This book is about cities and globalization for this very reason. It is centered on cities because they have played a crucial role throughout the whole process as centers of exchange and as focal points of developments. It is here that two rather different strands of literature meet: On the one hand, there is vivid research on “global cities” (or “world cities”) going back to the concepts of John Friedman and Saskia Sassen in the 1980s and early 1990s (as a global space also referencing Manuel Castell’s “network society”) although the term is certainly older. 2 On the other hand, the ideas of historians like Fernand Braudel, who observed that “central cities” shaped “world economies”, 3 are highly relevant in this context and show that certain nodes of exchange have been crucial for the overall development of the world even in times when city populations were comparably small and the world economies far from global in a literal sense.

4 See Taylor (1999), also with reference to several seminal works on global cities.

- 5 The KOF Index of Globalization was recently extended backwards until 1970; Dreher et al. (2009), 29

5 Further, Peter Taylor correctly claims that there is a clear empirical misbalance of city- and state-centered research, especially with regard to connections between cities. 4 From this approach, the research tradition of the Global and World Cities (GaWC) network emerged, which challenged this lack of data, especially when compared to data about nation-states, for which also a lot of ranking exercises referring to their degree of globalization exist. However, all this research has, so far, remained focused on the present and has lacked a historical dimension. As a result, most quantitative research about globalization focuses on variables, which are useful only for analyzing short-term trends (if any). 5 This is totally clear when data about internet access, international tourism or UN peace-keeping missions is included, which – as such – can logically only exist for a few decades. But it is also true for seemingly more neutral data like foreign direct investment (FDI), gross domestic product (GDP), migration flows or portfolio investments, which in many cases is not only poorly specified historically (and consequently hardly collected), but also – at least potentially – omits factors relevant for earlier globalization episodes, which could be informative for recent developments as well. In addition, most of this data is collected in a regular and comparable way for states only, today as well as in the past.

6 This book approaches several of the shortcomings of earlier literature about globalization and about cities. It offers a multi-dimensional perspective on several time periods, places and reference texts, on economic, cultural and social phenomena manifesting in and connecting cities in the context of globalization (or at least global relevance at the respective time). Thus it offers empirical material to understand how global processes affected these cities and vice versa. And it offers discussions of the concept of global city, especially in the context of (re) writing global history.

Now There is the Book…

7 The book starts with a general historical discussion about the connection between urbanization and the industrial revolution by Franz Mathis (Innsbruck). In the chapter No Industrialization without Urbanization: The Role of Cities in Modern Economic Development , Mathis emphasizes the role of cities as amplifiers of change. They provide agglomerations of people, of supply (of labor and capital) and demand (for goods and services), of markets and opportunities. Hence, they are a precondition, as well as an incentive, for industrialization. The connection is positive (as shown by the examples of Britain, the U.S. and Japan) as well as negative (where there are no cities, there is no industrialization) and is also relevant in today’s globalization, as more recent examples of successful industrialization in the developing world show.

6 Abu-Lughod (1989).

8 In a second overview chapter, Locating and Teaching Cities in the “New” World History: Perspectives from the U. S. after the Fall of “Western Civilization”, Jim Mokhiber (New Orleans) demonstrates how the global city concept in world history research and teaching has been neglected. Mokhiber links Sassen’s theoretical approach, which is extensively outlined in this contribution, to Janet Abu-Lughod’s work on the premodern Eurasian world system 6 and thus demonstrates the usefulness of a historically grounded debate. But he also draws the connection between city research and the teaching of world history and discusses the didactic usefulness of cities in this context, an approach that is certainly applicable beyond the context of teaching (Western) civilization history in the United States.

7 Wallerstein (1974).

9 Finally, in a third overview chapter, Bringing Economic Geography Back in: Global Cities and the Governance of Commodity Chain , Christof Parnreiter (Hamburg) argues – from a geographic perspective – that global cities have to be theoretically conceptualized and empirically scrutinized as critical nodes in commodity chains. He stresses the inherent spatial character of the concept and emphasizes the connections to world systems theory, 7 to which many of the authors in this book at least implicitly refer; he also discusses the problem of governance in this context.

10 The second part of the book contains five case studies from very diverse historical epochs and places, which are presented chronologically. The first, The Phenomenon of Global Cities in the Ancient World by Brigitte Truschnegg (Innsbruck), analyzes the reception of ancient cities as “global” (in its meaning at the respective time). In her comparative study of Alexandria, Babylon, Athens, Carthage and Rome, she not only stresses and discusses cultural significance, economic relevance and political power as notable dimensions of global reach, but also the problems in finding historically stable concepts to measure these dimensions. Hence, her contribution is also very valuable in interdisciplinary methodological terms.

11 The second case study by Robert Dupont (New Orleans), New Orleans as a Global City: Contemporary Assessment and Past Glory , describes one of the first colonial settlements in what was to become the South of the United States and its multifarious history. Throughout time, New Orleans has shown some of the features that mark a global city, especially in the early nineteenth century, when it was among the most relevant port cities in the Americas (if not the world) because of its strategic location at the mouth of the Mississippi. Besides this historical assessment, Dupont also contributes to methodological questions and provides a discussion of the global city concept in the context of urban studies.

12 In the third case study, Zanzibar: Imperialism, Proto-Globalization, and a Nineteenth Century Indian Ocean Boom Town , Erik Gilbert (Arkansas) analyzes the increasingly multiethnic city of Zanzibar. It is still perceived as “ancient”, but is actually a quite recent product of the emerging globalized Indian Ocean economy in the nineteenth century, which was ruled by the British. Here we find a second, more local example for the relevance of perception, as well as the mutual forces of influence, in a nutshell: while Zanzibar is a product of this “new” economy, it simultaneously helped to shape it. Consequently, the chapter also draws our attention to Africa, often enough neglected as a place of agency in global processes.

13 While these case studies focus on historical developments, the remaining two are more spatial in their approach. The fourth case study, The Evolution of a Global City: Vienna’s Integration into the World City System , by Robert Musil (Vienna), examines the connection between cities and globalization by focusing on a semi-peripheral (or second order) city, Vienna. This contribution is particularly interesting not only because it is explicitly spatial, but also because it directly relates to the concept of pathdependence. It does not only provide an empirical study of the global city hypothesis, but it also discusses the question of how influential the history of a city is for its current role in a larger network of cities (a concept that lies at the heart of Peter Taylor’s understanding of “global city”). While Vienna is the most likely Austrian candidate for a global city today and in the past, its connections rest on its historical function as a bridge between East and West in Europe, on its role as the metropolis of a multi-ethnic empire and also on its role in the slow industrialization of this empire during the nineteenth century.

14 Finally, in São Paulo: Big, Bigger, Global? The Development of a Megacity in the Global South , Tobias Töpfer (Innsbruck) leads us to one of the great metropolises of today’s global South and echoes discussions presented earlier in the volume (especially Mathis, Parnreiter and Musil). In his chapter, he not only provides an interesting typological discussion on the question of what kind of city São Paulo in Brazil actually is (along the main categories of global city vs. megacity), but he also stresses the consequences of its actual status for the geography of the city and the greater metropolitan area as well as its historical and recent development. As a result, while there is no doubt that São Paulo is a megacity, its status as a “global” city is debatable.

8 These chapters were selected via a call for papers for the conference preceding this book.

15 Instead of a concluding section, the third part of the book presents a collection of three shorter works from diverse disciplinary backgrounds as some kind of research outlook. 8 In the first of these, The Reach of the Continental Blockade: The Case of Toulouse , Andreas Dibiasi (Zurich) takes an economic-historical approach as he discusses the effects of the conflicts during the Napoleonic Wars on the economic situation (especially the prices) in the city of Toulouse. The second, Designing a Global City: Tokyo , is an architectural case study from a city-planning perspective by Beate Löffler (Dresden) about the largest metropolitan area today, which Sassen explicitly mentions as one of the prominent examples of a global city. The third, The Council of European Municipalities and Regions: Shared Governance in a World Featured by Globalization Issues by Manfred Kohler (Bruxelles), finally provides an institutional case study from a political-science perspective, linking the levels of regions and cities with that of nations and supra-national entities. All three of these chapters refer to important but somehow neglected topics and provide fruitful directions for further research about cities and globalization, namely economic integration, cultural perception and political governance.

16 Throughout the book, we also find reflections on various concepts related to the idea of “global” cities. Most of the authors refer explicitly to Saskia Sassen’s work, and all conceptualize their approach in the broader context of works that try to define world versus global cities, as well as about metropolises, megacities or central, imperial and primary cities. These reflections are necessary because the concepts cannot simply be used interchangeably and hence have to be clarified, especially when applied to historical material. As a result, the book is also interesting for those looking for conceptual clarifications, which is particularly relevant from a historical perspective, because the term “global city” as originally coined is a rather specific idea not easily applied to historical research. Thus, the contributions to this book also pave the way for a historically informed re-conceptualization of the approach.

… But There Also Was a Preceding Conference

- 9 For more information, see www.uibk.ac.at/fakultaeten/vwl/forschung/wsg/symp11.html (accessed 15 Feb (...)

- 10 While Christof Parnreiter could not participate in the conference, he was able to provide a chapter (...)

17 However, the book is also the result of an even longer process. It is based on a conference dedicated to discuss some of the problems associated to the global-city debate. 9 The Conference in World History: The Role and Significance of Global City was held in November 2011 in Innsbruck as a joint conference of the partner universities of Innsbruck and New Orleans. At this interdisciplinary conference, earlier versions of most of the papers were presented. 10 In the course of the event, the fruitful and intense discussions between the researchers from Europe and the United States gave rise to considerably improved papers, which now constitute the chapters of this book.

18 To assist the participants in the process of producing the chapters for the book, we ended the conference with a concluding round-table talk, dedicated to summarize the results and still-open questions. Chaired by Günter Bischof (New Orleans), Franz Mathis (Innsbruck) and James Mokhiber (New Orleans), who have also contributed to this book, as well as Katja Schmidtpott (Marburg) and Malte Fuhrmann (Istanbul), who presented papers at the conference, exchanged reflections about the conference and discussed these with the audience.

19 The first question raised in this talk was whether a global city necessarily must be multi-ethnic – which has been the case in some of the examples discussed during the conference (like Istanbul, Venice or New Orleans). On the other hand, Tokyo, one of the cities used by Saskia Sassen to elaborate her global city thesis, is certainly far from being “global” in that sense on account of its lack of “foreign faces”. Hence, as Katja Schmidtpott argued, the description of a city as global depends on the observer’s point of view. From an economic point of view, Tokyo may clearly be “global”, but from the Japanologists’perspective, things look rather different, notably less connected and interrelated. Multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism, two specific manifestations of multi-ethnicity, are particularly relevant here, although these concepts are sometimes overloaded. But they point to the fact that multi-ethnicity is neither necessarily successful nor peaceful but has to develop, often in a contradictory and discordant way.

20 In addition, the question of measurability of the concept “global” remained unanswered (and is consequently picked up and clarified in several contributions to this volume). What is regarded as “global” is often subject to a certain approach. One could, like James Mokhiber did in his talk, easily argue that the number of plane flights that arrive or depart in a city’s airport is relevant. This is an indicator of exchange in general, indeed, but also more specifically of international tourism, which can be further intensified by a proper utilization of the cultural heritage of a city, of its very nature as a global city, of codes dedicated to fulfill the expectations of international costumers. Icons are relevant, and – as some contributions to this volume very clearly show – they always have been for the perception of a city. But the connection to the global market is an additional factor in the process, and many cities became “boom towns” only after their (economic) globalization.

21 It is also worth noting that further conceptual differentiation is necessary. Franz Mathis emphasized the difference between megacities and global cities (which is explicitly picked up in this volume by Tobias Töpfer), a difference directly related to globalization. Consequently, big cities have to be divided into cities that play an important role within a global network and cities that are “merely” important for their region. In this context, megacities are cities whose economic and cultural importance grows because of their connection to their hinterland, while global cities owe their specific significance to their connections to the “wide globalized world”. Both concepts are connected: historically, many cities grew at first because of their relations to the hinterland and only later reached global importance by connections to a wider global market. But this is only one element of the “global character” of a city. As Malte Fuhrmann mentioned with reference to Immanuel Wallerstein, a starting point to conceptualize this could be a city’s connections to the world system (which is explicitly picked up in this volume by Christof Parnreiter and James Mokhiber). And here we come back to Fernand Braudel, who has identified “world cities” as the driving forces of development in early modern Europe, as exemplified by port cities in which overseas markets and connections dominated local exchange. As a result, both paths are possible, and a major city can develop from a local or a global base although the difference will most likely influence the character and potential of a city. Finally, achieving a “global” character also leads to problems, prominently problems of governability of a city and its diverse population, often also resulting in a spatial differentiation of the city in connection to the influences of globalization.

11 Schulz (2006), 53 (translation Brigitte Truschnegg).

22 Not surprisingly, many questions remain open after the conference and also after the publication of this book. It still is unclear what makes a city a global city: is it cultural factors, economic factors, multi-ethnicity, or a combination of all of these – and if so, what kind of combination? The answers may remain subject to conceptualizations specific for certain questions. A more general characterization may be approached via a description of Athens, taken from a chapter in this volume: “Never has a city in so short a time unharnessed so much tradition-building energy that even millenniums later people look upon it as a spiritual mother”. 11 What more could be said about a city than that it transcends space and time, at least as an idea? The only caveat is that a statement like this can never be said about a contemporary city, because judgments like these are always strictly retrospective.

23 While this book contributes to a critical reflection of concepts related to the global city debate and provides empirical material from various periods and places, further research is still necessary. But cities are a fruitful and at the same time rather neglected laboratory of social, economic and cultural, sometimes also political change. They are clearly worth studying, because cities are central places in the process of mutual influence of globalization on people (and vice versa). They are meeting places, communication nodes and sites of exchange as well as locations where global processes become particularly visible and influential. “Global cities” are and always have been both, products and producers of globalization. They play an important role in shaping a global economy, culture and society, but they are also shaped by it. And they are places where countervailing forces match and local reactions to globalization become especially visible. Consequently, the adverse effects of globalization are particularly apparent as well: not only economic exchange, migration, communication, and technological development take place predominantly in cities, but also political conflict, cultures clashing and amalgamating, and violence. Hence, the global city is opening a door to the world, for better or for worse, as a multifaceted information interface and as a focal point of globalization in various forms.

12 Taylor et al. (2012).

24 Some of these forms will be explored in more detail in this book. To address all would require not a single one but shelves of them. And indeed, when we were about to finish this book, Routledge published a four-volume collection of seminal contributions to research about Global Cities . 12 While its price (₤ 800) is still rather prohibitive and points to the fact that some profits can be earned by doing global city research, its publication is also showing the relevance of this book and underlining the growing importance of the subject. Furthermore, the examples stressed here can also be understood complementary, because they are special and hence particularly instructive: they do not simply discuss the usual suspects (like London or New York) but take a much broader approach; and they also re-read several of these seminal contributions from different disciplinary, geographical and historical backgrounds. In the end, they offer an elaborate arrangement of viewpoints certainly worth exploring in more detail.

Bibliographie

Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (1989): Before European Hegemony: The World System, A. D. 1250 – 1350. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Braudel, Fernand (1984): Civilization and Capitalism, 15th – 18th Centuries , Volume 3: The Perspective of the World . New York: Harper & Row.

Castells, Manuel (1996): The Rise of the Network Society . Oxford: Blackwell.

Castells, Manuel, ed. (2004): The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective . Cheltenham: Elgar.

Dreher, Axel/Gaston, Noel/Martens, Pim/van Boxem, Lotte (2009): “Measuring Globalization. Opening the Black Box. A Critical Analysis of Globalization Indices”, Bond University Messages 32.

Exenberger, Andreas (2007): “Reiche als Partner, Gegner oder Ziel? Die historischen Erfahrungen zweier europäischer Weltstädte”, in: Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 115 (1-2), 76-84.

Exenberger, Andreas/Cian, Carmen (2006): Der weite Horizont. Globalisierung durch Kaufleute . Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

Friedmann, John (1986): “The World City Hyphothesis”, in: Development and Change 17, 69-83.

Sassen, Saskia (1991): Global Cities. Princeton/NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sassen, Saskia (1994): Cities in a World-Economy . Thousand Oaks/CA: Pine Forge.

Schulz, Raimund (2006): “Die Schule von Hellas”, in: Ameling, Walter/Gehrke, Hans-Joachim/Kolb, Frank/Leppin, Hartmut/Schulz, Raimund/Streck, Michael P./Wiesehöfer, Josef/Wilhelm, Gernot (2006): Antike Metropolen . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 53-68.

Taylor, Peter J. (1999): “So-called ‘World Cities’: The Evidential Structure within a Literature”, in: Environment and Planning A 31 (11), 1901-1904.

Taylor, Peter J./Beaverstock, Jonathan V./Derudder, Ben/Faulconbridge, James/Harrison, John/Hoyler, Michael/Pain, Kathy/Witlox, Frank, eds. (2012): Global Cities . 4 vols. London: Routledge.

Wallerstein, Immanuel M. (1974): The Modern World-System , Volume 1: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century . New York-London: Academic Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel M. (2004): World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction . Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press.

3 Braudel (1986) particularly referred to Venice, Antwerp, Genoa and Amsterdam as cities that shaped late medieval and early modern Europe, at least economically. See also Exenberger/Cian (2006) and Exenberger (2007) for more extensive elaborations on the significance of Venice and the hanseatic city of Lubeck for “globalization” in Europe in medieval times.

5 The KOF Index of Globalization was recently extended backwards until 1970; Dreher et al. (2009), 29.

9 For more information, see www.uibk.ac.at/fakultaeten/vwl/forschung/wsg/symp11.html (accessed 15 Feb 2013).

10 While Christof Parnreiter could not participate in the conference, he was able to provide a chapter for the book. Unfortunately there are also three contributions, which had – for various reasons – to be withdrawn from it. Katja Schmidtpott (Marburg) talked about The Globalization of Labour in East Asia: The Japanese Treaty Port of Yokohama and Its Chinese Community , a case study from the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century; Malte Fuhrmann (Istanbul) about When the Conquering Sultan Appears in the Metro and Byzantium Sabotages the Railway Station: Istanbul’s Pasts and their Roles in the Present , a long-term city history focusing on its perception and instrumentalization; and Mathilde Leduc-Grimaldi (Tervuren) about Tide of Times in the Post-Colonial Era: Tourists, Venetians and Street Vendors in the Doge City , a contemporary case study about social relationships in a historically loaded environment.

Du même auteur

- Afrika, ein Kontinent der Extreme? in Afrika – Kontinent der Extreme , , 2011

- Afrikanerinnen und Afrikaner in Globo: Idealtypische Profile als wissenschaftliches Instrument in Afrika – Kontinent der Extreme , , 2011

- Globalization and Austria: Past and Present in Global Austria , , 2011

- Tous les textes

- Globalization and the City , , 2013

Le texte et les autres éléments (illustrations, fichiers annexes importés) sont sous Licence OpenEdition Books , sauf mention contraire.

Two Connected Phenomena in Past and Present

Vérifiez si votre institution a déjà acquis ce livre : authentifiez-vous à OpenEdition Freemium for Books. Vous pouvez suggérer à votre bibliothèque/établissement d’acquérir un ou plusieurs livres publié(s) sur OpenEdition Books. N'hésitez pas à lui indiquer nos coordonnées : OpenEdition - Service Freemium [email protected] 22 rue John Maynard Keynes Bat. C - 13013 Marseille France Vous pouvez également nous indiquer à l'aide du formulaire suivant les coordonnées de votre institution ou de votre bibliothèque afin que nous les contactions pour leur suggérer l’achat de ce livre.

Merci, nous transmettrons rapidement votre demande à votre bibliothèque.

Référence électronique du chapitre

Référence électronique du livre, collez le code html suivant pour intégrer ce livre sur votre site..

OpenEdition est un portail de ressources électroniques en sciences humaines et sociales.

- OpenEdition Journals

- OpenEdition Books

- OpenEdition Freemium

- Mentions légales

- Politique de confidentialité

- Gestion des cookies

- Signaler un problème

Vous allez être redirigé vers OpenEdition Search

Lavoisier: Greatest Hits of Baroque Chemistry

Derobotizing human thought - a sustainable response ii, openmind books, scientific anniversaries, does laboratory meat have a future, featured author, latest book, the global city: introducing a concept.

Each phase in the long history of the world economy raises specific questions about the particular conditions that make it possible. One of the key properties of the current phase is the ascendance of information technologies and the associated increase in the mobility and liquidity of capital. There have long been cross-border economic processes—flows of capital, labor, goods, raw materials, and tourists. But to a large extent these took place within the inter-state system, where the key articulators were national states. The international economic system was ensconced largely in this inter-state system. This has changed rather dramatically over the last decade as a result of privatization, deregulation, the opening up of national economies to foreign firms, and the growing participation of national economic actors in global markets.

It is in this context that we see a rescaling of what are the strategic territories that articulate the new system. With the partial unbundling or at least weakening of the national as a spatial unit due to privatization and deregulation and the associated strengthening of globalization, come conditions for the ascendance of other spatial units or scales. Among these are the sub-national, notably cities and regions; cross-border regions encompassing two or more sub-national entities; and supra-national entities, i.e., global digitalized markets and free trade blocs. The dynamics and processes that get terrritorialized at these diverse scales can in principle be regional, national or global.

I locate the emergence of global cities in this context and against this range of instantiations of strategic scales and spatial units (Sassen 2001; 2006a). In the case of global cities, the dynamics and processes that get territorialized are global. Here I examine the general conceptual and empirical elements that can be applied to a large number of very diverse cities, each with its own empirical specificities.

Elements in a new conceptual architecture

The globalization of economic activity entails a new type of organizational structure. To capture this theoretically and empirically requires, correspondingly, a new type of conceptual architecture.1 Constructs such as the global city and the global-city region are, in my reading, important elements in this new conceptual architecture. The activity of naming these elements is part of the conceptual work. There are other closely linked terms which could conceivably have been used: the old and by now classic term world cities,2 “supervilles” (Braudel 1984), informational city (Castells 1989). Thus choosing how to name a configuration has its own substantive rationality.

When I first chose to use global city (1984), I did so knowingly—it was an attempt to name a difference: the specificity of the global as it gets structured in the contemporary period. I did not chose the obvious alternative, world city, because it had precisely the opposite attribute: it referred to a type of city that we have seen over the centuries (e.g., Braudel 1984; Hall 1966; King 1990; Gugler 2004), and most probably also in much earlier periods in Asia (Abu-Lughod 1989) or in European colonial centers (King 1990) than in the West. In this regard it could be said that most of today’s major global cities are also world cities, but that there may well be some global cities today that are not world cities in the full, rich sense of that term. This is partly an empirical question; further, as the global economy expands and incorporates additional cities into the various networks, it is quite possible that the answer to that particular question will vary. Thus, the fact that Miami has developed global city functions beginning in the late 1980s does not make it a world city in that older sense of the term.

The global city model: organizing hypotheses

There are seven hypotheses through which I organized the data and the theorization of the global city model. I will discuss each of these briefly as a way of producing a more precise representation.

Firstly, the geographic dispersal of economic activities that marks globalization, along with the simultaneous integration of such geographically dispersed activities, is a key factor feeding the growth and importance of central corporate functions. The more dispersed a firm’s operations across different countries, the more complex and strategic its central functions—that is, the work of managing, coordinating, servicing, financing a firm’s network of operations.

Secondly, these central functions become so complex that increasingly the headquarters of large global firms outsource them: they buy a share of their central functions from highly specialized service firms: accounting, legal, public relations, programming, telecommunications, and other such services. Thus while even ten years ago the key site for the production of these central headquarter functions was the headquarters of a firm, today there is a second key site: the specialized service firms contracted by headquarters to produce some of these central functions or components of them. This is especially the case with firms involved in global markets and non-routine operations. But increasingly the headquarters of all large firms are buying more of such inputs rather than producing them in-house.

Thirdly, those specialized service firms engaged in the most complex and globalized markets are subject to agglomeration economies. The complexity of the services they need to produce, the uncertainty of the markets they are involved with either directly or through the headquarters for which they are producing the services, and the growing importance of speed in all these transactions, is a mix of conditions that constitutes a new agglomeration dynamic. The mix of firms, talents, and expertise from a broad range of specialized fields makes a certain type of urban environment function as an information center. Being in a city becomes synonymous with being in an extremely intense and dense information loop.

A fourth hypothesis, derived from the preceding one, is that the more headquarters outsource their most complex, unstandardized functions, particularly those subject to uncertain and changing markets, the freer they are to opt for any location, because less work actually done in the headquarters is subject to agglomeration economies. This further underlines that the key sector specifying the distinctive production advantages of global cities is the highly specialized and networked services sector. In developing this hypothesis I was responding to a very common notion that the number of headquarters is what specifies a global city. Empirically it may still be the case in many countries that the leading business center is also the leading concentration of headquarters, but this may well be because there is an absence of alternative locational options. But in countries with a well-developed infrastructure outside the leading business center, there are likely to be multiple locational options for such headquarters.

Fifthly, these specialized service firms need to provide a global service which has meant a global network of affiliates or some other form of partnership, and as a result we have seen a strengthening of cross border city-to-city transactions and networks. At the limit this may well be the beginning of the formation of transnational urban systems. The growth of global markets for finance and specialized services, the need for transnational servicing networks due to sharp increases in international investment, the reduced role of the government in the regulation of international economic activity and the corresponding ascendance of other institutional arenas, notably global markets and corporate headquarters—all these point to the existence of a series of transnational networks of cities.

A related hypothesis for research is that the economic fortunes of these cities become increasingly disconnected from their broader hinterlands or even their national economies. We can see here the formation, at least incipient, of transnational urban systems. To a large extent major business centers in the world today draw their importance from these transnational networks. There is no such thing as a single global city—and in this sense there is a sharp contrast with the erstwhile capitals of empires.

A sixth hypothesis, is that the growing numbers of high level professionals and high-profit making specialized service firms has the effect of raising the degree of spatial and socio-economic inequality evident in these cities. The strategic role of these specialized services as inputs raises the value of top-level professionals and their numbers. Furthermore, the fact that talent can matter enormously for the quality of these strategic outputs and, given the importance of speed, proven talent is an added value, the structure of rewards is likely to experience rapid increases. Types of activities and workers lacking these attributes, whether manufacturing or industrial services, are likely to get caught in the opposite cycle.

A seventh hypothesis is that one result of the dynamics described in hypothesis six is the growing informalization of a range of economic activities that find their effective demand in these cities yet have profit rates that do not allow them to compete for various resources with the high-profit making firms at the top of the system. Informalizing part or all production and distribution activities, including of services, is one way of surviving under these conditions.

Recovering place and work process

In the first four hypotheses, my effort was to qualify what was emerging in the 1980s as a dominant discourse on globalization, technology, and cities that posited the end of cities as important economic units or scales. I saw a tendency in that account to take the existence of a global economic system as a given, a function of the power of transnational corporations and global communications.

My counter argument is that the capabilities for global operation, coordination, and control contained in the new information technologies and in the power of transnational corporations need to be produced. By focusing on the production of these capabilities we add a neglected dimension to the familiar issue of the power of large corporations and the capacity of the new technologies to neutralize distance and place. A focus on the production of these capabilities shifts the emphasis to the practices that constitute what we call economic globalization and global control.

Further, a focus on practices draws the categories of place and work process into the analysis of economic globalization. These are two categories easily overlooked in accounts centered on the hypermobility of capital and the power of transnationals. Developing categories such as place and work process does not negate the centrality of hypermobility and power. Rather, it brings to the fore the fact that many of the resources necessary for global economic activities are not hypermobile and are, indeed, deeply embedded in place, notably places such as global cities, global-city regions, and export processing zones.

This entails a whole infrastructure of activities, firms, and jobs that are necessary to run the advanced corporate economy. These industries are typically conceptualized in terms of the hypermobility of their outputs and the high levels of expertise of their professionals rather than in terms of the production or work process involved and the requisite infrastructure of facilities and non-expert jobs that are also part of these industries. Focusing on the work process brings with it an emphasis on economic and spatial polarization because of the disproportionate concentration of very high- and very low-income jobs in these major global city sectors. Emphasizing place, infrastructure, and non-expert jobs matters precisely because so much of the focus has been on the neutralization of geography and place made possible by the new technologies.

The growth of networked cross-border dynamics among global cities includes a broad range of domains: political, cultural, social, and criminal. There are cross-border transactions among immigrant communities and communities of origin, and a greater intensity in the use of these networks once they become established, including for economic activities. We also see greater cross-border networks for cultural purposes, as in the growth of international markets for art and a transnational class of curators; and for non-formal political purposes, as in the growth of transnational networks of activists around environmental causes, human rights, and so on. These are largely city-to-city cross-border networks, or, at least, it appears at this time to be simpler to capture the existence and modalities of these networks at the city level. The same can be said for the new cross-border criminal networks.

Recapturing the geography of places involved in globalization allows us to recapture people, workers, communities, and more specifically, the many different work cultures, besides the corporate culture, involved in the work of globalization. It also brings with it an enormous research agenda, one that goes beyond the by now familiar focus on cross-border flows of goods, capital, and information. It opens up the global city as a space for a new type of politics, one that claims rights to the city.

Finally, by emphasizing the fact that global processes are at least partly embedded in national territories, such a focus introduces new variables in current conceptions about economic globalization and the shrinking regulatory role of the state. That is to say, the space economy for major new transnational economic processes diverges in significant ways from the duality global/national presupposed in many analyses of the global economy. The duality, national versus global, suggests two mutually exclusive spaces—where one begins the other ends. One of the outcomes of a global city analysis is that it makes evident that the global materializes by necessity in specific places, and institutional arrangements, a good number of which, if not most, are located in national territories.

Worldwide networks and central command functions

The geography of globalization contains both a dynamic of dispersal and of centralization. The massive trends towards the spatial dispersal of economic activities at the metropolitan, national, and global level that we associate with globalization have contributed to a demand for new forms of territorial centralization of top-level management and control functions. Insofar as these functions benefit from agglomeration economies even in the face of telematic integration of a firm’s globally dispersed manufacturing and service operations, they tend to locate in cities. This raises a question as to why they should benefit from agglomeration economies, especially since globalized economic sectors tend to be intensive users of the new telecommunications and computer technologies, and increasingly produce a partly dematerialized output, such as financial instruments and specialized services. There is growing evidence that business networks are a crucial variable that is to be distinguished from technical networks. Such business networks have been crucial long before the current technologies were developed. Business networks benefit from agglomeration economies and hence thrive in cities even today when simultaneous global communication is possible. Elsewhere, I examine this issue and find that the key variable contributing to the spatial concentration of central functions and associated agglomeration economies is the extent to which this dispersal occurs under conditions of concentration in control, ownership, and profit appropriation (Sassen 2001, ch. 2 & 5).

This dynamic of simultaneous geographic dispersal and concentration is one of the key elements in the organizational architecture of the global economic system. While there is no space to discuss it here, this systemic feature also enables particular types of struggles and implementations linked to environmental sustainability (Sassen 2006b; Marcotullio and Lo 2001). Let me first give some empirical referents and then examine some of the implications for theorizing the impact of globalization and the new technologies on cities.

The rapid growth of affiliates illustrates the dynamic of simultaneous geographic dispersal and concentration of a firm’s operations. By 1999 firms had well over half a million affiliates outside their home countries, and by 2005 they had well over a million such affiliates (for details see Sassen, 2006a: chapter 2). Firms with large numbers of geographically dispersed factories and service outlets face massive new needs for central coordination and servicing, especially when their affiliates involve foreign countries with different legal and accounting systems.

Another instance today of this negotiation between a global cross-border dynamic and territorially specific site is that of the global financial markets. The orders of magnitude in these transactions have risen sharply, as illustrated by the US$300 plus trillion for 2007 in traded derivatives, a major component of the global economy and one that dwarfs the value of global trade which stood at US$14 trillion. These transactions are partly embedded in electronic systems that make possible the instantaneous transmission of money and information around the globe. Much attention has gone to this capacity for instantaneous transmission of the new technologies. But the other half of the story is the extent to which the global financial markets are located in an expanding network of cities, with a disproportionate concentration in cities of the global north. Indeed, the degrees of concentration internationally and within countries are unexpectedly high for an increasingly globalized and digitized economic sector. Inside countries, the leading financial centers today concentrate a greater share of national financial activity than even ten years ago, and internationally, cities in the global north concentrate well over half of the global capital market.

One of the components of the global capital market is stock markets. The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the addition of markets such as Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, Mexico City, Bangkok, Taipei, Moscow, and growing numbers of non-national firms listed in most of these markets. The growing number of stock markets has contributed to raise the capital that can be mobilized through these markets, reflected in the sharp worldwide growth of stock market capitalization, which reached well over US$30 trillion in 2007. This globally integrated financial market, which makes possible the circulation of publicly listed shares around the globe in seconds, is embedded in a grid of very material, physical, strategic places.

The specific forms assumed by globalization over the last decade have created particular organizational requirements. The emergence of global markets for finance and specialized services, the growth of investment as a major type of international transaction, all have contributed to the expansion in command functions and in the demand for specialized services for firms (3).

By central functions I do not only mean top level headquarters; I am referring to all the top level financial, legal, accounting, managerial, executive, planning functions necessary to run a corporate organization operating in more than one country, and increasingly in several countries. These central functions are partly embedded in headquarters, but also in good part in what has been called the corporate services complex, that is, the network of financial, legal, accounting, advertising firms that handle the complexities of operating in more than one national legal system, national accounting system, advertising culture, etc., and do so under conditions of rapid innovations in all these fields (see generally Bryson and Daniels 2005). Such services have become so specialized and complex, that headquarters increasingly buy them from specialized firms rather than producing them in-house. These agglomerations of firms producing central functions for the management and coordination of global economic systems, are disproportionately concentrated in the highly developed countries—particularly, though not exclusively, in global cities. Such concentrations of functions represent a strategic factor in the organization of the global economy, and they are situated in an expanding network of global cities (4).

It is important analytically to unbundle strategic functions for the global economy or for global operation, and the overall corporate economy of a country. These global control and command functions are partly embedded in national corporate structures, but also constitute a distinct corporate subsector. This subsector can be conceived as part of a network that connects global cities across the world through firms’ affiliates or other representative offices (5). For the purposes of certain kinds of inquiry this distinction may not matter; for the purposes of understanding the global economy, it does.

This distinction also matters for questions of regulation, notably regulation of cross-border activities. If the strategic central functions—both those produced in corporate headquarters and those produced in the specialized corporate services sector—are located in a network of major financial and business centers, the question of regulating what amounts to a key part of the global economy will entail a different type of effort from what would be the case if the strategic management and coordination functions were as distributed geographically as the factories, service outlets, and affiliates generally. We can also read this as a strategic geography for political activisms that seek accountability from major corporate actors, among others concerning environmental standards and workplace standards.

National and global markets as well as globally integrated organizations require central places where the work of globalization gets done. Finance and advanced corporate services are industries producing the organizational commodities necessary for the implementation and management of global economic systems. Cities are preferred sites for the production of these services, particularly the most innovative, speculative, internationalized service sectors. Further, leading firms in information industries require a vast physical infrastructure containing strategic nodes with hyper-concentration of facilities; we need to distinguish between the capacity for global transmission/communication and the material conditions that make this possible. Finally, even the most advanced information industries have a production process that is at least partly place-bound because of the combination of resources it requires even when the outputs are hypermobile.

Theoretically this addresses two key issues in current debates and scholarship. One of these is the complex articulation between capital fixity and capital mobility and the other, the position of cities in a global economy. Elsewhere, I have developed the thesis that capital mobility cannot be reduced simply to that which moves nor can it be reduced to the technologies that facilitate movement (Sassen 2008, ch. 5 & 7). Rather, multiple components of what we keep thinking of as capital fixity are actually components of capital mobility. This conceptualization allows us to reposition the role of cities in an increasingly globalizing world, in that they contain the resources that enable firms and markets to have global operations (6). The mobility of capital, whether in the form of investments, trade, or overseas affiliates, needs to be managed, serviced, coordinated. These are often rather place-bound, yet are key components of capital mobility. Finally, states, place-bound institutional orders, have played an often crucial role in producing regulatory environments that facilitate the implementation of cross-border operations for their national and for foreign firms, investors, and markets (Sassen 2008, ch. 4 & 5).

In brief, a focus on cities makes it possible to recognize the anchoring of multiple cross-border dynamics in a network of places, prominent among which are cities, particularly global cities or those with global city functions. This in turn anchors various features of globalization in the specific conditions and histories of these cities, in their variable articulations with their national economies, and with various world economies across time and place (e.g., Abu-Lughod 1999; Allen et al. 1999; Gugler, 2004; Amen et al. 2006; Taylor 2004; Lo and Yeung 1996; Harvey 2007; Orum and Chen 2004). This optic on globalization contributes to identifying a complex organizational architecture that cuts across borders, and is both partly de-territorialized and partly spatially concentrated in cities. Further, it creates an enormous research agenda in that every particular national or urban economy has its specific and inherited modes of articulating with current global circuits. Once we have more information about this variance we may also be able to establish whether position in the global hierarchy makes a difference and the various ways in which it might do so.

Impacts of new communication technologies on centrality

Cities have historically provided national economies, polities, and societies with something we can think of as centrality. In terms of their economic function, cities provide agglomeration economies, massive concentrations of information on the latest developments, a marketplace. How do the new technologies of communication alter the role of centrality and hence of cities as economic entities?

As earlier sections have indicated, centrality remains a key feature of today’s global economy. But today there is no longer a simple straightforward relation between centrality and such geographic entities as the downtown, or the central business district (CBD). In the past, and up to quite recently in fact, the center was synonymous with the downtown or the CBD. Today, partly as a result of the new communication technologies, the spatial correlates of the center can assume several geographic forms, ranging from the CBD to a new global grid of cities (see, for instance, Herzog 2006; Burdett 2006; Short 2005; Marcuse 2003).