A 7-Step Guide To Building Your Author Persona

Before we begin, let’s break down the words.

Author: The writer of a book, the face behind a writing piece, maker of the manuscript, wordsmith of a document, owner of an article, dramatist of an incident in terms of write-ups, correspondent of a topic, screenwriter of a movie, scriptwriter of a web series, biographer of a personality, novelist of a novel, reporter of a worldly issue, journalist of the events witnessed, poet of the stanzas, songwriter of a song, pen-pusher of letters, and columnist of a newspaper.

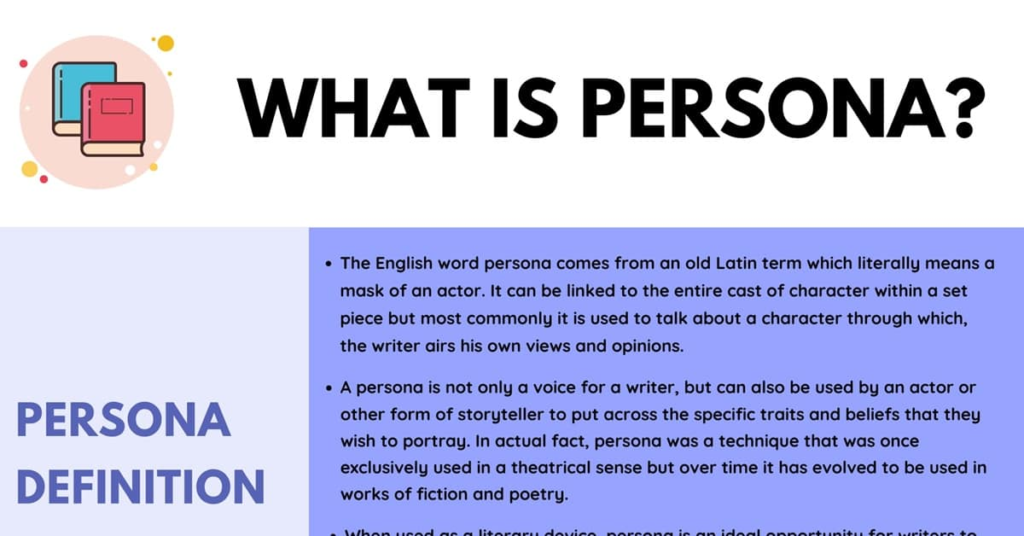

Persona: A person’s personality, facade worn by a man or a woman, identity of an individual, mask put on by a person, the front portion of a human being, exterior guise adorned by a character, role played by someone, the personality of an actor, the image of a mortal soul, the public face of a fellow.

As we can see, an author can be so many things in so many ways. Therefore, an author’s persona is an ideal way to define who the author is. A good author persona can help communicate the background and personality of the author to the reader. The author’s persona is the projection of the author, their personality, and the person behind the words the readers have come to like.

In the age of social media, it is easy to find out information about a particular author or person with just a few simple searches. However, the author’s persona is not just the author’s bio; it also gives insights that help resonate with the audience and create a brand!

This article will detail the step-by-step process of creating an author persona, which will help you to define the best brand for your book – YOU!

What is an Author Persona?

Be it Earnest Hemingway, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Stephen King, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, or modern-day authors like Dan Brown, John Grisham, Paulo Coelho, George Orwell, or Neil Gaiman, all these authors do not just have a fantastic storyline and narration, but a knack of creating stellar author personas.

And it is not just authors who have a unique persona of their own; you can see it in public figures like Michael Jackson, Vincent Van Gough, and Pablo Picasso, who have created larger-than-life images. But have you ever wondered how much of their public version is actually true? Is Hemingway the man he showcases himself to be: regal, shotgun-wielding, drunk, adventurer-genius? Is Stephen King always wise and spooky, identifying the world’s fears and taking us on a rollercoaster ride? Or is he funny, wise, and a regular person?

The author’s persona is what you would call “’your brand,” the story, the emotion, or the real-life version of who you are. An author persona will help your readers better connect with you and create a unique brand that people will be drawn to. It can be based on the characters in your stories or be a version of you that considers all the emotions, instances, and experiences that make you “YOU.”

The author persona doesn’t have to be a mask you wear to create a whole new brand or something you hide behind. Instead, it can be an eccentric version of who you are, as real as you can be. Everyone’s persona is unique, so it is your personal story or brand that you want to communicate to your readers in the form of your persona.

How to Create Your Author Persona in 7 Steps

Now that you have understood the author’s persona let us dive into understanding seven easy steps to craft an author’s persona.

1. Determine what you’d want to communicate with your audience

Remember when you fell in love with a book or a story and decided to look for the author? What is the information that you looked for? What was it about their story that instantly connected with you?

The author’s persona is a way for the writer to give the reader a glimpse of their personality and life. To craft the perfect persona, start by understanding what you want your readers to know about you. Depending on how you want to position yourself, you will need to look at several facets of your personality and craft a short bio that you want to share with your audience.

2. Understand your target readership or audience

Next, try to find out who your target audience is. What is it that they expect from the author or the writer? Your author’s persona should be such that your target audience can instantly connect with it and make you part of their tribe.

While you may not always share the same age, gender, or have similar beliefs as your target audience, understanding their perspective and ensuring that your persona addresses them are vital to creating a good impression.

For example, if you write children’s novels, you do not have to be their age to understand them. Just talk about the child within you, what compelled you to write, and the stories you have grown up with.

3. Find out your unique strengths.

To write a stellar author or writer’s persona, it is a good starting point to answer some questions such as:

- What qualities about yourself do you like the most? Do you wish to communicate these qualities to your readers?

- What do your family and friends tell you about you? What is it about you that they like the most?

- How were you introduced to writing? What made you take the plunge in writing the book or article or pursuing a career in writing?

- What makes you, YOU?

- Who do you want to be in the near future?

- What’s the best thing about you?

Knowing your strengths is essential, as you can focus on and amplify them in your persona, allowing your audience to know just what makes you tick!

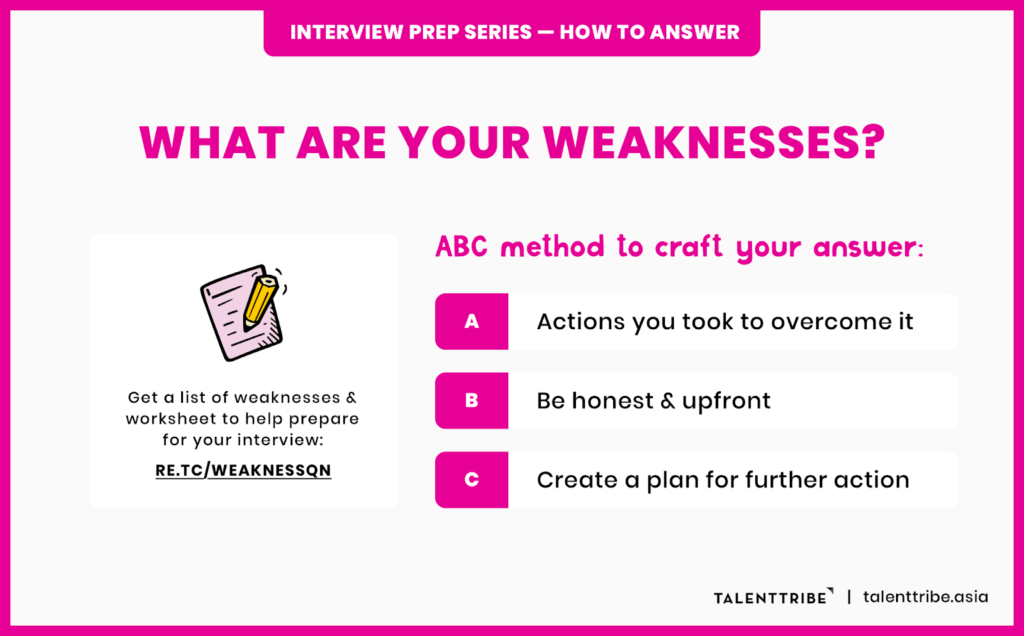

4. Be open to talking about your weaknesses.

The most honest persona openly talks about a person’s flaws or weaknesses and accepts them. No one in this world is perfect, and your audience doesn’t expect you to be either. Instead, if you are open to sharing the ups and downs of your life, do that!

It is always inspiring when someone you are in awe of tells you about the situations they have experienced, failures, or challenges of their own, and your audience will value you for being vocal about it!

5. Carve a niche

Every person is unique, and your persona should reflect that. It is important to identify your niche and focus on amplifying the person you are and the expertise you bring to the table for your persona to stand out. You can write about much, but focusing on your core proposition helps keep the persona short but impactful.

6. Have fun

Do you find the process of creating your persona tiring, tedious, or daunting? Writing about oneself is a tough job and will make you restless, but do not worry. Remember that you know yourself best.

Instead of worrying about how it sounds or how your audience will perceive you, just make sure to relax and have fun!

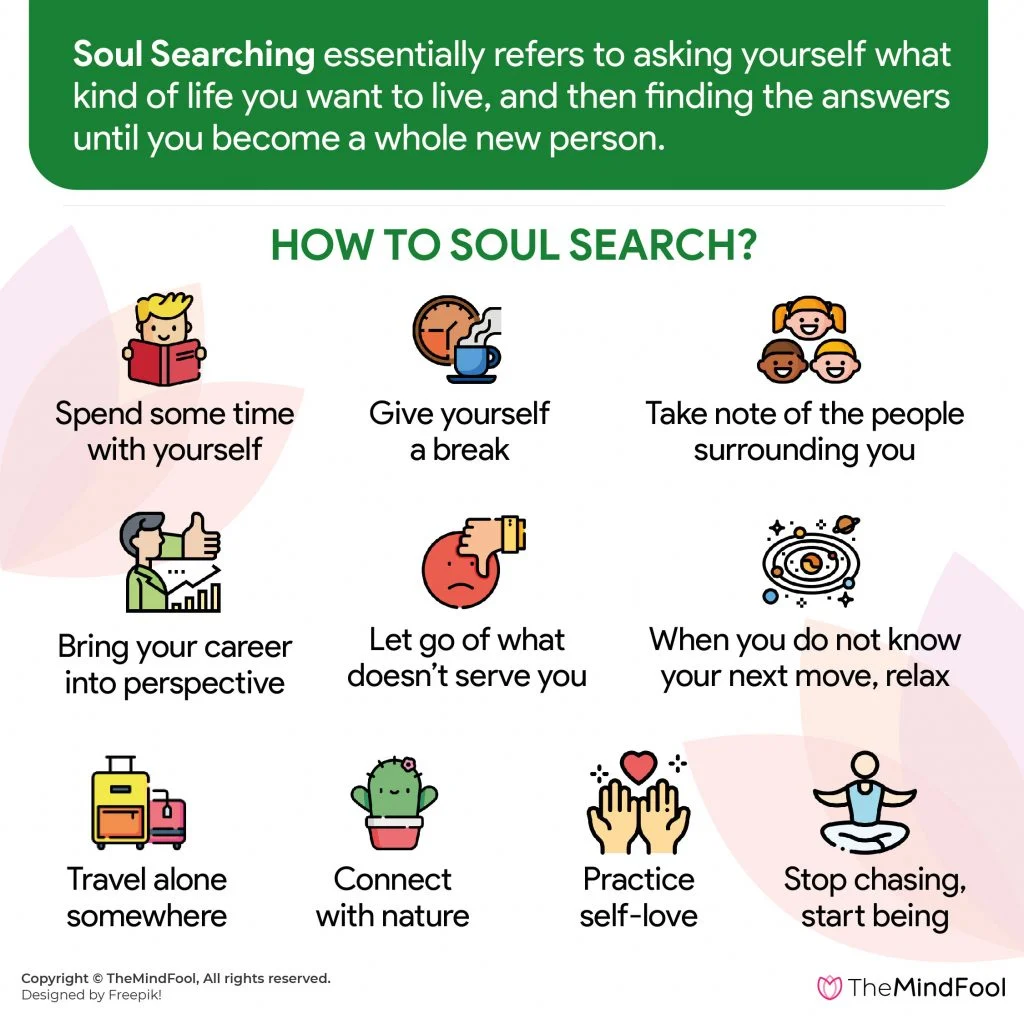

7. Do some soul searching

Finally, creating an author’s persona is an opportunity to do some soul searching and understand the multiple facets of your personality. Look deep within and uncover what you want to communicate with your readers. Ask questions like:

- What is my purpose?

- Why did I choose writing as my salvation?

- What is it that defines your writing?

- Where do you see yourself in a few years?

Source

These questions will help you create a genuine author persona, which is essential for your readers.

As famous American Novelist David Guterson has said, “I have relaxed into my persona as an author, although I used to fight that.” That is truly the key to creating a stellar and real persona, just ease into it, and allow the magic that you can weave with your words to also reflect in the person you are!

This blog should help you discover your unique writer’s persona and enable you to polish it until it feels natural and real. Enjoy the writing process, and remember, it is all about having fun and allowing your passion to take over!

Key Takeaways

- The author’s persona is what you would call “your brand,” the story, emotion, or real-life version of who you are. An author persona will help your readers connect with you better and creates a unique brand that people will be drawn to.

- To craft the perfect persona, start by understanding what you want your readers to know about you.

- Next, try to find out who your target audience is. What is it that they expect from the author or the writer? Your author’s persona should be such that your target audience can instantly connect with it and make you part of their tribe.

- Know your strengths and play on them when writing your author persona.

- Also, do not just focus on the positives. If there are weaknesses or flaws you think will add value, go ahead and share them.

- Finally, creating an author’s persona is an opportunity to do some soul searching and understand the multiple facets of your personality. Look deep within and uncover what you want to communicate with your readers.

The author’s persona is what you would call “your brand,” story, emotion, or a real-life version of who you are. An author persona will help your readers connect with you better and creates a unique brand that people will be drawn to. It can be based on the characters in your stories or be a version of you that considers all the emotions, instances, and learnings that make you “YOU.”

1. Determine what you’d want to communicate with your audience 2. Understand your target readership or audience 3. Find out your unique strengths 4. Be open to talking about your weaknesses 5. Carve a niche 6. Have fun 7. Do some soul searching

As a storyteller, the reader is genuinely interested in knowing the story behind the storyteller, and this is where an author’s persona comes into play. It tells the reader about the writer and their story, enabling them to better connect with the book, article, or any written piece.

Latest Blogs

In this blog, explore the golden rules of using AI marketing tools so you can leverage the benefits to their maximum potential.

In this blog, you’ll learn how to avoid the pitfalls of SEO over-optimization while enhancing your site’s performance.

In this article, we’ll take a look at what AMP is, its advantages and disadvantages, and how it affects SEO.

Get your hands on the latest news!

Similar posts.

9 mins read

Content Marketing vs Advertising – Which One is More Effective?

11 mins read

Interactive Content vs. Static Content: Which is More Effective?

6 mins read

Unlocking Success: 4 Case Studies of Successful Content Marketing Campaigns Using a Platform

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Voice, Tone, and Persona

Enhance the likelihood that readers will respond favorably to your document by projecting an effective voice, tone, and persona.Voice, Tone, and Persona are slippery terms/concepts. In some instances, these terms can be used interchangeably, yet important differences do exist.

The term voice may be used to define a writer’s stance toward his subject or readers. For example, a writer could say, “I’m using a satirical (or humorous, condescending, patronizing) voice in this editorial.”

Alternatively, some writers and English instructors talk about a writer’s voice as a representation of the trueness of a document. An accomplished writer is said to have found his or her voice while a beginning writer is said to be searching for his or her voice. When used in this way, voice refers to the “trueness” or “honesty” or “authority” or “power” of a writer’s message. Back in the 1960s, some writing instructors suggested inexperienced writers needed to find their true voice–that each of us has a specific voice that we need to find, that voice is a powerful, mystical force that helps us convey truth or the inner quality of a topic.

When writers and English instructors talk about tone, they are typically referring to the author’s stance toward his or her readers and message. Specific documents or authors can be described as having a condescending, arrogant, pedantic, racist, confident, or satirical tone (or voice). In this way, tone is used interchangeably with voice, although tone does not refer to the “truth” of the writer’s message, unlike voice.

The term persona refers to an author’s use of a literary mask to hide his or her true opinion about a matter. For example, if you were writing about how you act while waiting in long lines, you might want to honestly inform your reader that you become a raging lunatic, that your heart rate doubles, and that you can keep calm only by doing sit-ups and push-ups. Yet if you are not proud of this type-A tendency, you might present the persona of a patient person who has mastered the ability to meditate calmly and think deeply about important issues when forced to wait in a seemingly endless line.

Different readers may make different assessments regarding a particular author’s voice, tone, and persona. An author may describe his tone as reasoned, thoughtful, and intelligent whereas the reader might dismiss the author’s text as biased, underdeveloped, or emotional.

Why Should You Consider Your Voice, Tone, and Persona?

Just as listeners make assumptions about your personality by observing how you dress and act and by listening to the tone of your voice, readers make judgments about your personality and feelings regarding a subject based on what and how you write. When you avoid use of the first person and personal references, readers make judgments about what kind of person you are and about your professional abilities. Readers make assumptions about how clever and fair a thinker you are by noting the quality of your reasoning, the words you choose, and the way you format your text. By noting an author’s examples, organization, and word choices, we might say, for instance, that he or she displays an opinionated, logical, or emotional persona. Problems such as spelling and punctuation errors or pronoun agreement errors can turn readers against you, making them consider you to be careless or uneducated.

Consider these questions when revising a document:

- What inferences about my personality do I want my readers to make?

- Given my audience and purpose, is it appropriate to express my feelings about this subject?

- Would it be more appropriate for me to project a strong, passionate tone, or should I try to appear more objective?

- Based on what I have written, what sense about my personality or feelings about the subject will readers be likely to infer?

- Have I used any words or examples that are emotionally charged and likely to alienate my readers?

- What personal examples should I add or delete to help my readers better understand me and my message?

Why Read Your Work Out Loud?

The challenge of juggling apparently unrelated ideas can be so great that you may overlook your voice or tone. When attempting to explain complex ideas and processes, you may understandably focus your critical energies on being coherent and logical. Yet, you might also remember that readers are people too, and they are likely to be swayed as much by their sense of how credible you are as by the logic of your argument. One trick that writers use to gauge the voice in a document is to read a manuscript aloud or to speak it into a tape recorder and then listen to how they sound.

Create an Energetic Voice

The vitality of a writer’s voice or persona often has a tremendous influence on readers’ responses. Sometimes readers say they enjoy a text because an author seems straightforward and personable. In contrast, sometimes readers dislike a book because the author seems stuffy or cold-hearted. As an example of the latter, note the “computer tone” in the following letter, which I received after the birth of my first child:

Thank you for cooperating with the hospital stay verification component of your Health Insurance Policy. The company has been notified of the patient’s emergency admission. The information submitted has been reviewed and a length of stay has been assigned. This emergency stay is certified for two days.

We remind you that the review of your hospital stay was limited to determining the appropriate length of stay for the emergency admitting diagnosis and did not question medical necessity. We further remind you that payment of benefits is still subject to the terms of your Health Insurance Policy.

Surely this is an impersonal, mechanical way to say that my newborn would be covered by my insurance policy–a fact that I already knew. Although the letter was signed by a person, it seems to have been written by a computer. If I had called this person on the phone, she probably would have said something like, “Congratulations on the birth of your baby. As you already know, your insurance covers expenses for two days of hospitalization. Enjoy that little one!” One message, two very different voices.

Trying to communicate your subject in a coherent way can be so overwhelming that you forget to consider the influence of your voice or persona on the reader.

Avoid a Pedantic, Passive Tone

Based on what you say, your readers will make judgments about whether you seem knowledgeable, educated, compassionate, angry, or confused. If you use excessive jargon, write extensively in the passive voice, fail to offer specific examples to illustrate your point, or do not elaborate on essential information, then some readers might consider you to be aloof or pompous, while others might assume that you are reluctant or unable to communicate.

Sometimes people believe they need to sound “academic” when they write; they don’t think they can simply be themselves and write naturally. Rather than trying to simplify their prose, they reach for a thesaurus and select the least understood or most impressive-sounding word. Here’s a sample of terribly technical language that a colleague of mine wrote to satirize the humorous elements of jargon-ridden prose:

Health is generally benefited by the voluntary ingestion of 4000 to 5000 ml of hydrogen hydroxide in each 24-hour period, distributed more or less equally across the time period in 250 to 500 ml units.

When you read this, it may at first seem sophisticated, enshrouded as it is in pseudoscientific garb. Yet, properly translated into readable English, it simply says, “Drink eight glasses of water a day.” Pretentious jargon and obscure language can at first be intimidating because the authors appear to be implying that we should understand the message. However, college-educated, critical readers are rarely impressed by vague, abstract language. For example, what do you think of the following prose, which is excerpted from a draft of a graduate student’s essay on language development?

An oral language production system is the first one learned by children. The task of learning a written language production system occurs when children enter school. A noticeable difference between these two systems is the presence of a conversational partner. This difference is significant when you compare speaking and writing at the level of continuous discourse. Conversational partners provide constant cues, such as to elaborate, to clarify, to keep a goal in mind, to stay on the topic, etc. Evidence of children’s dependence on conversational inputs when learning to write comes from observing effects of prompting children to continue, that is to take another conversational turn. Children are dependent to some extent on conversation interchange to develop a text. However, no conversational partner exists in written composition. Learning to write involves a transition from a language introduction system dependent on inputs from a conversational partner to a system capable of functioning autonomously. Without conversational supports, children have problems in thinking what to say, in making choices appropriate to a remote audience, in staying on the topic, and in producing an intelligible whole.

Clearly, this passage is weakened by jargon. A critical reader will wonder, for example, about the need for such terms as “oral language production system,” “continuous discourse,” or “conversational interchange.” More insidious in this example, however, is the abundance of passive constructions and lack of people-oriented references. For example, who is doing the observing in the following sentence: “Evidence of children’s dependence on conversational inputs when learning to write comes from observing effects of prompting children to continue, that is to take another conversational turn”? Also, take a look at the emptiness of the third sentence: “A noticeable difference between these two systems is the presence of a conversational partner.” Even with rereading, it is unclear whether the “oral language production system” or the “written language production system” has “the presence of a conversational partner.” Of course, the author could argue that everyone knows that conversation usually involves a dialogue between speakers while writing usually lacks such an exchange. Naturally, clever readers will see through the fog with a discerning eye and recognize that the writer’s ideas are in fact relatively simple:

Perhaps children don’t learn to write until they enter school because writing demands more than speech. Whereas children can easily develop their ideas through dialogue—that is, by listening to queries and comments and suggestions from other speakers—they must conceptualize an audience when they write.

Ultimately, however, if you think about the gist of this writer’s message long enough, it becomes so obvious that you wonder about the need to say it at all. Surprisingly, you will often find this to be the case: pedantic, long-winded speakers and writers are often hiding simple concepts behind verbal smoke screens. Thus, when you read, remember to be a critical reader.

Adapted from Consider Your Voice, Tone, and Persona by Joseph M. Moxley ( Writing Commons ) licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Check Your Understanding

Writing as Critical Inquiry Copyright © by Keri Sanburn Behre, Ph.D. and Kate Comer, Ph.D. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Persona

I. What is Persona?

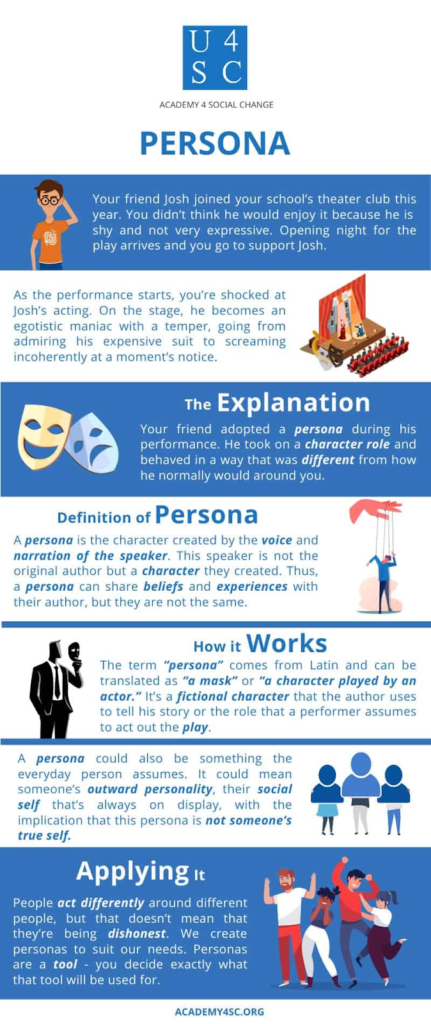

Have you ever tried to make a particular impression upon people? Such as when giving a presentation or meeting new people? Perhaps you tried to speak and act a little differently than you would if you weren’t trying to make any impression; in other words, you might have used your voice, appearance, and body language to present a particular personality to people. This personality, that you present to people, is a kind of persona (pronounced ‘per-SO-na’).

Persona is a Latin word for a type of mask that was worn by stage actors at that time, which represented their character. Nowadays , persona can refer to the characters in any dramatic or literary work. But it has another special meaning in literary studies, where it refers to the voice of a particular kind of character—the character who is also the narrator within a literary work written from the first-person point of view.

Finally, in psychology, a persona is the “mask” (the personality) that you present to the world, the role you play in public.

Simply, a persona is a personality.

The plural of persona is personae (pronounced ’per-SO-nigh’)

II. Examples of Personae

In terms of social / psychological personae, many politicians present the persona of being conscientious (caring and honest) and responsible. They want to be seen as caring about the people they represent, whether this is true or not.

For another example, the persona I use in front of the child I babysit is different from the one I use in front of my school-friends. Most people show a different persona when working than with friends.

In terms of literary personae, T.S. Elliot is well known for the unique personae of the narrators of some of his poems, such as the persona of J. Alfred Prufrock, who narrates the poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Another unique persona is the un-named femal narrator of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” There is a good reason that we use the special word persona for these narrator-characters; we only know them through their own words and thoughts, so we only know the persona they are presenting to the reader.

And don’t forget that the word is also used to refer to the characters in a dramatic production; the first character listed in the dramatis personae for Shakespeare’s Hamlet is Claudius, the King of Denmark.

III. Types of Persona

There are not really “types” of persona , only the different meanings of persona; once again:

a. Character

If you look at the beginning of any play, you will see the “dramatis personae,” the list of all of the characters, the personae. Novels also have dramatis personae, although they are usually not listed. Some novels might show you an illustration of a family tree. Every work of literature, dramatic, prosaic, or poetic has characters, or at least one—the narrator—at minimum. Every literary work has personae.

When an author writes a first-person narrator, he or she needs to adopt a particular “voice”—a verbal personality for that narrator. This is also a persona. But only when the narrator is a character—even if we don’t know their name. To be a persona, the narrator must simply have a personality and identity which is not supposed to be that of the actual author. We don’t use the word persona for the voice of the actual author.

c. Public (fake) personality

When you go out in public, you dress a certain way, talk a certain way, act a certain way. All of these behaviors change, depending upon whom you meet and what impression you want to make on them. These personalities are your public personae.

In addition, there are generic personae—personality types; we have specific ideas about how certain people should look and behave. A teacher should be like this . . . A doctor should be like this . . . A pirate is like this . . . These are also personae.

IV. The Importance of Using Personae

The importance of using persona has been discussed since ancient times. “Aristotle in the Poetics says that the poet should say very little in propria persona (in his own voice), as he is no imitator or poet when speaking from himself.” What this means is that in works of fiction (prosaic, poetic or dramatic) the author must put her own personality aside, and become a character—the narrator. This is because every word you write should be part of the art of your creation; there is no place for your real self in a piece of fiction; you should use the role of the narrator to further entertain and enlighten the reader.

Personae are also important because they are a part of how we interact with others in our lives. In front of your parents, you adopt one persona. In front of your friends, another. In front of your teachers, a third. These personas may be vastly different, or they may be similar, but they are all personas.

Using personae in your writing is important because characters must have unique personae, with different feelings and voices than you have; otherwise they would really all be you!

V. Examples of Persona in Literature

Examples of persona can be found in dramatic literature, poetry and prose.

Example 1: Dramatic Literature (plays)

This is the list of Dramatis Personae for Shakespeare’s Romero and Juliet :

Montague, Capulet, heads of warring households Romeo, son to Montague Mercutio, kinsman to the prince, and friend to Romeo Friar Laurence, Friar John, Franciscans An Apothecary Lady Montague, wife to Montague Lady Capulet, wife to Capulet Juliet, daughter to Capulet Citizens of Verona; Maskers, Guards, Watchmen, and Attendants

Example 2: Poetry

In his poem, Annabel Lee , Edgar Allan Poe uses a persona to tell his story. Poe wrote the poem, but he is not the “me” who is speaking in it. That “me” is another character, another voice.

It was many and many a year ago, In a kingdom by the sea, That a maiden there lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee; And this maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me.

Example 3: Prose

Tracy Chevalier writes historical fiction. These are fictional stories based upon historical events. In her novel, Girl with A Pearl Earring , Chevalier takes on the persona of a girl named Griet and writes the novel so that it seems as though Griet is narrating her own story:

My mother did not tell me they were coming. Afterwards she said she did not want me to appear nervous. I was surprised, for I thought she knew me well. Strangers would think I was calm. I did not cry as a baby. Only my mother would note the tightness along my jaw, the widening of my already wide eyes.

VI. Examples of Persona in Popular Culture

Look at most social groups, especially in High School; they are defined in terms of stereotypes , which have personas associated with them. Here is a list you might recognize: jocks, goths, nerds, punks, rebels, drama queens, and hippies. The list goes on. Of course, people aren’t really stereotypes; there are nerds that get bad grades and jocks who make art! But these stereotypes have personas associated with them that we all recognize and can even put on and off.

Performers almost always use personas. We can see this easily when looking at musicians. Many rappers use the “gangsta” persona, like Snoop Dogg or Dr. Dre. Gorillaz is a virtual band that uses a totally fictional persona, depicted through animation. Each member of the classic 1970’s band, The Village People, had a different persona: native American, soldier, biker, construction worker, policeman and cowboy.

Celebrities do, and to a certain extent, MUST adopt personas. If you go to a book or album signing for your favorite writer or performer, you want to meet the idealized version of this person. You are not there to hear about how normal they are, or how they have a headache or how tired they feel. You want to see the stage version. Celebrities are by definition personas. They are larger than life. They exist apart from reality.

You can also find examples of literary-like personas in television shows and movies, when a show is narrated by a character, such as in Mr. Robot . Or in shows that have a host. For example, John Stewart and Stephen Colbert have both become famous for their personae, because they host their non-fiction comedy shows in the roles of ultra-right-wing commentators, although their real political views are more left-wing.

VII. Related Terms

“The attitude toward the subject expressed in a work. Tone usually is understood as the author’s attitude but need not be identified with the author.”

The voice an author uses when writing, usually their own writing style or point of view.

- Point of View

When you write, you can use three different points of view: first person (I), second person (you), or third person (he or she). Whichever point of view you use, the narrator has a persona, but since in the third-person point of view, the narrator is supposed to be the author, usually we only talk about persona for first-person narratives . However, even a third-person narrator can have a persona which is not that of the true author.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Persona in writing shapes the perspective through which ideas, characters or individuals are understood, blending foundational roles like 'The Hero' or 'The Rebel' with personal histories and motivations. In writing, t's the intersection of your backstory with your values, strengths, interactions, and goals that lends depth and context. This article explores the myriad ways personas shape our daily interactions, stories, and self-presentations. Gain insights into how you can effectively craft an appropriate and effective persona.

Persona is a multifaceted representation of how an individual, literary character, or entity portrays their identity to the world. It’s about masks, roles, and how these shift depending on context.

Persona in writing and communication is a complex construct of characteristics that define how an individual, character, or entity is presented. Specifically, it entails:

- Role and Archetype: Foundational character types or roles, such as ‘The Hero,’ ‘The Mentor,’ or ‘The Rebel,’ offer a primary lens for understanding behavior, responses, and motivations in a narrative or real-world context.

- Background and Experience: Every individual or character carries a backstory, a history that impacts current decisions, actions, and worldviews, granting depth and context to their persona.

- Values and Motivations: Beyond mere actions, the driving forces behind decisions and behaviors are deeply tied to the core beliefs, principles, and desires that guide an individual or character.

- Strengths and Vulnerabilities: These inherent attributes influence interactions, reactions, and decisions. They shape the nature of the persona’s engagements, whether leading to success, conflict, or growth.

- Interactions and Dynamics: How a persona connects with others, the nature of their relationships (friendly, adversarial, neutral), and the quality of their engagements play a crucial role in defining them.

- Physical and Emotional Attributes: Observable traits and internal emotions, moods, and feelings add layers of depth, making the persona relatable, distinctive, or memorable.

- Goals and Aspirations: |What the persona aims for, their dreams, ambitions, or objectives, defines their journey, guiding their decisions and actions in various scenarios.

Key Concepts: Rhetorical Reasoning ; Rhetorical Stance ; Customer Discovery ; Venture Design .

Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception. Niccolo Machiavelli

Persona from a Rhetorical Perspective

For writers, persona functions as a rhetorical tool: writers meticulously engaged in rhetorical analysis , rhetorical reasoning , and customer discovery to determine the persona they need to project to accomplish their aims of discourse . For instance,

- a politician could pander by attempting to appear religious when the last time he viewed a church was watching the Exorcist or The Two Popes .

- a self-assessed introvert could present herself as an extrovert when applying for a job as a salesperson or some other sort of role that involves dealing with the public.

- a writer who views a topic to be deadly serious (e.g., environmental degradation) could use humor or satire to lighten the tone of their text.

Adopting a persona is not necessarily disingenuous. The politician could be deeply concerned about representing her constituents. The car salesman could really care that he finds the car that fits your needs and desires.

Persona as a Subjective, Interpretative Framework

Readers, right or wrong, make judgments about who you are based on their interpretation of your persona. Communication is invariably a psychosocial, semiotic process . At one level, you cannot control the interpretations of your audience. As a rhetor you may consider your tone and voice as reasoned, thoughtful, and intelligent whereas the reader might dismiss your text as biased, underdeveloped, or emotional.

Yet because your persona may play a big role in establishing whether your audience will give sufficient time to reflect on your persona–and to ask different readers to give you feedback on whether the tone of a particular text is appropriate and effective.

Persona in Literature

Persona in literature refers to a a mask, a role, a performance, which someone (a person, a literary character) projects to others in response to a particular exigency and rhetorical situation .

In 1895, Vladimir Propp, a Soviet folklorist and structuralist, analyzed hundreds of traditional Russian fairy tales to identify recurring plot structures and character roles. From his work, he delineated a set of character roles, often termed “spheres of action,” that appear consistently in tales.

- The Hero: Often the protagonist, embarking on a quest or challenged to prove their worth.

- The Villain: Opposes the hero, creating the central conflict in the narrative.

- The Donor: Provides the hero with a magical object or crucial piece of knowledge.

- The Helper: Assists and supports the hero throughout their journey.

- The Princess (or Prize): Typically the hero’s objective; their plight often prompts the hero’s journey.

- Her Father: Can act as an impediment to the hero or as the individual setting the task for the hero.

- The Dispatcher: Sends the hero on their quest.

- The False Hero: Initially perceived as good, their true nature is revealed as deceitful or malevolent.

Persona in Customer Discovery & Usability

In Customer Discovery as well as Usability Studies , two common empirical research methods, persona (sometimes Customer Persona or User Persona ) refers to a type of user who represents a cohort of other users. Founders/Developers/Investigators engage in customer discovery or venture design in order to better understand the problem space from the customer’s point of view . By interviewing loads of customers, they hope to identify how the user navigates the problem space. They talk one-on-one with customers to understand what each customer thinks, sees, feels, and does when facing a problem in a problem space . Then, over time, after repeated customer discovery interviews, founders/developers/investigators look for patterns in customer interviews. They come to divide customers into customer segments by examining how the customer navigates the problem space. For example, when interviewing customers about their experiences learning new technologies for his research study on what influences people regarding their adoption of new technologies, Everett Rogers (2003) theorized there are five major types of consumers:

- Early Adopters

- Early Majority

- Late Majority

In the world of product design and marketing, a persona shifts its meaning to represent a specific user demographic. This profile, often crafted from research and interviews, amalgamates preferences, habits, and needs of similar users, providing designers with a blueprint of who they’re catering to with a product, application, or service.

Propp, V. (1927). Morphology of the Folk Tale . Trans., Laurence Scott. 2nd ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions- Spring 2024

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Faculty Notes Submission Form

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is a Persona? || Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms

"what is a persona": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the Full Series: The Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is a Persona? Transcript (English subtitles available in video)

By Walter Moore

1 April 2021

As we learned from JT Bushnell’s “What is a Narrator?” video, when we read fiction, we should not assume that the work of literature has been written in the voice of the creator of the document. The same goes for poetry. Consider this poem by Billy Collins called “The Revenant”:

I am the dog you put to sleep, as you like to call the needle of oblivion, come back to tell you this simple thing: I never liked you--not one bit.

When I licked your face, I thought of biting off your nose. When I watched you toweling yourself dry, I wanted to leap and unman you with a snap…

You’ll notice that this poem is not written in the voice of the poet Billy Collins. Instead, Collins has chosen to write in the first-person voice of a deceased dog who has returned from the dead (as “the revenant”) to make his confessions and explanations—a final word of sorts in a voice that is not the poet.

In poetry, this literary device is what we call persona.

billy_collins_revenant_persona.jpg

Persona derives from the Latin, meaning mask, or more specifically a mask in the theater or on the stage. The employ of persona has been around for centuries, but people did not use the term until the middle of the 18th Century—and they only used it then to describe characters in stage plays. In the 19th Century, the literary scope widened and the term persona was used to describe particular poems, short stories, and novels.

More recently, in the 20th and 21st Centuries, we have used the term beyond literature to describe politicians, pop stars, and other celebrities who project a public image or, in some extreme cases, an alter ego, that drastically differs from a private identity, sometimes to the point of bizarro delusion. Just think of people such as Norma Jeane Mortenson as Marilyn Monroe, Robert Zimmerman as Bob Dylan, David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, Stephani Germanota as Lady Gaga, Niki Minaj as countless characters and/or identities, or just consider the persona of pretty much anyone in the United States Congress.

lady_gaga_persona.jpg

Famous literary examples of persona abound. We think about William Blake writing in the voice of a young chimney sweeper, or Sylvia Plath writing in the voice of Lady Lazarus, or Gwendolyn Brooks writing in the voice of teenagers who have skipped school to play pool at a bar.

As you read, ask yourself what the effect is of any given literary persona? Who is the speaker? Who is the “I” of the poem or story? Is the poet or writer being ironic ? Is the persona a vehicle for parody or satire ? Is the persona in the form of a monologue or soliloquy ? Is it written as stream-of-consciousness ? More broadly, by using a voice of a person or thing that is not themselves, what message is the poet or writer trying to convey? Why did they make this narrative choice?

In the poem “The Revenant,” Collins conveys the message that sometimes human dog owners are perhaps too self-involved to completely know what their dogs need or even want—that there is often a communicative disconnect between a dog and its owner. Collins could have written this message in the voice of a dog owner or at least in the voice of some “woke” human, but the message wouldn’t have been as convincing probably. At the very least, it wouldn’t have been as funny.

Given all of this—just think, generally, anytime a writer or an artist writes or speaks or presents themselves in the voice of someone (or even something) else, it is considered an exhibition of persona.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Moore, Walter. "What is a Persona?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 1 Apr. 2021, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-persona . Accessed [insert date].

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

Book Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write a book review, a report or essay that offers a critical perspective on a text. It offers a process and suggests some strategies for writing book reviews.

What is a review?

A review is a critical evaluation of a text, event, object, or phenomenon. Reviews can consider books, articles, entire genres or fields of literature, architecture, art, fashion, restaurants, policies, exhibitions, performances, and many other forms. This handout will focus on book reviews. For a similar assignment, see our handout on literature reviews .

Above all, a review makes an argument. The most important element of a review is that it is a commentary, not merely a summary. It allows you to enter into dialogue and discussion with the work’s creator and with other audiences. You can offer agreement or disagreement and identify where you find the work exemplary or deficient in its knowledge, judgments, or organization. You should clearly state your opinion of the work in question, and that statement will probably resemble other types of academic writing, with a thesis statement, supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Typically, reviews are brief. In newspapers and academic journals, they rarely exceed 1000 words, although you may encounter lengthier assignments and extended commentaries. In either case, reviews need to be succinct. While they vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features:

- First, a review gives the reader a concise summary of the content. This includes a relevant description of the topic as well as its overall perspective, argument, or purpose.

- Second, and more importantly, a review offers a critical assessment of the content. This involves your reactions to the work under review: what strikes you as noteworthy, whether or not it was effective or persuasive, and how it enhanced your understanding of the issues at hand.

- Finally, in addition to analyzing the work, a review often suggests whether or not the audience would appreciate it.

Becoming an expert reviewer: three short examples

Reviewing can be a daunting task. Someone has asked for your opinion about something that you may feel unqualified to evaluate. Who are you to criticize Toni Morrison’s new book if you’ve never written a novel yourself, much less won a Nobel Prize? The point is that someone—a professor, a journal editor, peers in a study group—wants to know what you think about a particular work. You may not be (or feel like) an expert, but you need to pretend to be one for your particular audience. Nobody expects you to be the intellectual equal of the work’s creator, but your careful observations can provide you with the raw material to make reasoned judgments. Tactfully voicing agreement and disagreement, praise and criticism, is a valuable, challenging skill, and like many forms of writing, reviews require you to provide concrete evidence for your assertions.

Consider the following brief book review written for a history course on medieval Europe by a student who is fascinated with beer:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, investigates how women used to brew and sell the majority of ale drunk in England. Historically, ale and beer (not milk, wine, or water) were important elements of the English diet. Ale brewing was low-skill and low status labor that was complimentary to women’s domestic responsibilities. In the early fifteenth century, brewers began to make ale with hops, and they called this new drink “beer.” This technique allowed brewers to produce their beverages at a lower cost and to sell it more easily, although women generally stopped brewing once the business became more profitable.

The student describes the subject of the book and provides an accurate summary of its contents. But the reader does not learn some key information expected from a review: the author’s argument, the student’s appraisal of the book and its argument, and whether or not the student would recommend the book. As a critical assessment, a book review should focus on opinions, not facts and details. Summary should be kept to a minimum, and specific details should serve to illustrate arguments.

Now consider a review of the same book written by a slightly more opinionated student:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 was a colossal disappointment. I wanted to know about the rituals surrounding drinking in medieval England: the songs, the games, the parties. Bennett provided none of that information. I liked how the book showed ale and beer brewing as an economic activity, but the reader gets lost in the details of prices and wages. I was more interested in the private lives of the women brewsters. The book was divided into eight long chapters, and I can’t imagine why anyone would ever want to read it.

There’s no shortage of judgments in this review! But the student does not display a working knowledge of the book’s argument. The reader has a sense of what the student expected of the book, but no sense of what the author herself set out to prove. Although the student gives several reasons for the negative review, those examples do not clearly relate to each other as part of an overall evaluation—in other words, in support of a specific thesis. This review is indeed an assessment, but not a critical one.

Here is one final review of the same book:

One of feminism’s paradoxes—one that challenges many of its optimistic histories—is how patriarchy remains persistent over time. While Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 recognizes medieval women as historical actors through their ale brewing, it also shows that female agency had its limits with the advent of beer. I had assumed that those limits were religious and political, but Bennett shows how a “patriarchal equilibrium” shut women out of economic life as well. Her analysis of women’s wages in ale and beer production proves that a change in women’s work does not equate to a change in working women’s status. Contemporary feminists and historians alike should read Bennett’s book and think twice when they crack open their next brewsky.

This student’s review avoids the problems of the previous two examples. It combines balanced opinion and concrete example, a critical assessment based on an explicitly stated rationale, and a recommendation to a potential audience. The reader gets a sense of what the book’s author intended to demonstrate. Moreover, the student refers to an argument about feminist history in general that places the book in a specific genre and that reaches out to a general audience. The example of analyzing wages illustrates an argument, the analysis engages significant intellectual debates, and the reasons for the overall positive review are plainly visible. The review offers criteria, opinions, and support with which the reader can agree or disagree.

Developing an assessment: before you write

There is no definitive method to writing a review, although some critical thinking about the work at hand is necessary before you actually begin writing. Thus, writing a review is a two-step process: developing an argument about the work under consideration, and making that argument as you write an organized and well-supported draft. See our handout on argument .

What follows is a series of questions to focus your thinking as you dig into the work at hand. While the questions specifically consider book reviews, you can easily transpose them to an analysis of performances, exhibitions, and other review subjects. Don’t feel obligated to address each of the questions; some will be more relevant than others to the book in question.

- What is the thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world you know? What has the book accomplished?

- What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? What is the approach to the subject (topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive)?

- How does the author support their argument? What evidence do they use to prove their point? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author’s information (or conclusions) conflict with other books you’ve read, courses you’ve taken or just previous assumptions you had of the subject?

- How does the author structure their argument? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- How has this book helped you understand the subject? Would you recommend the book to your reader?

Beyond the internal workings of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the circumstances of the text’s production:

- Who is the author? Nationality, political persuasion, training, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the biographer was the subject’s best friend? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they write about?

- What is the book’s genre? Out of what field does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or literary standard on which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know. Keep in mind, though, that naming “firsts”—alongside naming “bests” and “onlys”—can be a risky business unless you’re absolutely certain.

Writing the review

Once you have made your observations and assessments of the work under review, carefully survey your notes and attempt to unify your impressions into a statement that will describe the purpose or thesis of your review. Check out our handout on thesis statements . Then, outline the arguments that support your thesis.

Your arguments should develop the thesis in a logical manner. That logic, unlike more standard academic writing, may initially emphasize the author’s argument while you develop your own in the course of the review. The relative emphasis depends on the nature of the review: if readers may be more interested in the work itself, you may want to make the work and the author more prominent; if you want the review to be about your perspective and opinions, then you may structure the review to privilege your observations over (but never separate from) those of the work under review. What follows is just one of many ways to organize a review.

Introduction

Since most reviews are brief, many writers begin with a catchy quip or anecdote that succinctly delivers their argument. But you can introduce your review differently depending on the argument and audience. The Writing Center’s handout on introductions can help you find an approach that works. In general, you should include:

- The name of the author and the book title and the main theme.

- Relevant details about who the author is and where they stand in the genre or field of inquiry. You could also link the title to the subject to show how the title explains the subject matter.

- The context of the book and/or your review. Placing your review in a framework that makes sense to your audience alerts readers to your “take” on the book. Perhaps you want to situate a book about the Cuban revolution in the context of Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union. Another reviewer might want to consider the book in the framework of Latin American social movements. Your choice of context informs your argument.

- The thesis of the book. If you are reviewing fiction, this may be difficult since novels, plays, and short stories rarely have explicit arguments. But identifying the book’s particular novelty, angle, or originality allows you to show what specific contribution the piece is trying to make.

- Your thesis about the book.

Summary of content

This should be brief, as analysis takes priority. In the course of making your assessment, you’ll hopefully be backing up your assertions with concrete evidence from the book, so some summary will be dispersed throughout other parts of the review.

The necessary amount of summary also depends on your audience. Graduate students, beware! If you are writing book reviews for colleagues—to prepare for comprehensive exams, for example—you may want to devote more attention to summarizing the book’s contents. If, on the other hand, your audience has already read the book—such as a class assignment on the same work—you may have more liberty to explore more subtle points and to emphasize your own argument. See our handout on summary for more tips.

Analysis and evaluation of the book

Your analysis and evaluation should be organized into paragraphs that deal with single aspects of your argument. This arrangement can be challenging when your purpose is to consider the book as a whole, but it can help you differentiate elements of your criticism and pair assertions with evidence more clearly. You do not necessarily need to work chronologically through the book as you discuss it. Given the argument you want to make, you can organize your paragraphs more usefully by themes, methods, or other elements of the book. If you find it useful to include comparisons to other books, keep them brief so that the book under review remains in the spotlight. Avoid excessive quotation and give a specific page reference in parentheses when you do quote. Remember that you can state many of the author’s points in your own words.

Sum up or restate your thesis or make the final judgment regarding the book. You should not introduce new evidence for your argument in the conclusion. You can, however, introduce new ideas that go beyond the book if they extend the logic of your own thesis. This paragraph needs to balance the book’s strengths and weaknesses in order to unify your evaluation. Did the body of your review have three negative paragraphs and one favorable one? What do they all add up to? The Writing Center’s handout on conclusions can help you make a final assessment.

Finally, a few general considerations:

- Review the book in front of you, not the book you wish the author had written. You can and should point out shortcomings or failures, but don’t criticize the book for not being something it was never intended to be.

- With any luck, the author of the book worked hard to find the right words to express her ideas. You should attempt to do the same. Precise language allows you to control the tone of your review.

- Never hesitate to challenge an assumption, approach, or argument. Be sure, however, to cite specific examples to back up your assertions carefully.

- Try to present a balanced argument about the value of the book for its audience. You’re entitled—and sometimes obligated—to voice strong agreement or disagreement. But keep in mind that a bad book takes as long to write as a good one, and every author deserves fair treatment. Harsh judgments are difficult to prove and can give readers the sense that you were unfair in your assessment.

- A great place to learn about book reviews is to look at examples. The New York Times Sunday Book Review and The New York Review of Books can show you how professional writers review books.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Drewry, John. 1974. Writing Book Reviews. Boston: Greenwood Press.

Hoge, James. 1987. Literary Reviewing. Charlottesville: University Virginia of Press.

Sova, Dawn, and Harry Teitelbaum. 2002. How to Write Book Reports , 4th ed. Lawrenceville, NY: Thomson/Arco.

Walford, A.J. 1986. Reviews and Reviewing: A Guide. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Scriptwriting

What is a Persona — Definition & Examples in Literature & Art

I t’s not so much that there are different types of personas so much as there are different interpretations of the word. An artist’s persona, a literary work’s personae, or the persona a writer takes on in a written work. So what is a persona exactly? And how do you know when you’re looking at one? Take a look at our definition and examples below to learn why all of these interpretations are correct, and how they each influence art of all media.

What is Persona?

First, let’s define persona.

We run into different personae on a daily basis. Whether through the art we consume or the people we meet. But if you need to define it more concretely, here’s what we suggest:

PERSONA DEFINITION

What is a persona.

A persona is typically the person understood to be speaking or narrating a given work. The persona is often intended to be someone other than the author of that work, even if we never learn who the persona is. The persona, pluralized as personae or personas, is a chosen voice by which a work or story is told, always for a storytelling purpose. A persona can also be a character or mask someone (like a performer, for instance) puts on for the purpose of elevating their work and/or concealing their own identity.

Persona examples:

- A book’s narrator

- Beyonce’s alter ego Sasha Fierce

- Public-facing behaviors and personalities which may shift depending on whom you are surrounded by

Implementing personae is a common literary tool. In fact, it's so common that you’ve likely seen it a million times and had no idea (especially if you’re an avid reader). In literature, a persona is frequently the voice by which your narration is told. Consider for example the Harry Potter book series.

Clearly, the novel is written by J.K. Rowling. However, the voice explaining the action is not J.K. Rowling herself. It’s never revealed who the voice is, nor is it meant to be any kind of mystery necessarily. But we know the voice is not Harry’s (or any other character’s for that matter). We also know it is not intended to be Rowling’s.

Rowling is not meant to be an omniscient witness to the events of Harry’s life. Therefore, the voice of the narrator is a conduit for the reader. Sometimes, the narrator will be a character from the story (whether a reliable narrator or unreliable narrator ), but if not, you’re reading through the author’s persona.

This is the more common interpretation of personae as a literary device . Check out the video below for more on how else it translates into other written works.

Persona as a Literary Term

As you can see, persona comes into play with poetry, just as much as it can with works like novels and even lyric-writing. This can perhaps be attributed to the notion that much of our storytelling norms come from Aristotle’s Poetics . In that book, Aristotle emphasizes the importance of an artist separating themselves from their work in order to lend every part of their efforts, and thus themselves, to their story. Which brings us to the next section.

Characters or Personae

Persona as a character.

A number of iconic performers would do Aristotle proud. And that’s because this concept is very popular with musicians in particular. What’s particularly interesting is that artists carry out their personas in their own special way, never necessarily beholden to a set of rules or norms.

For example, Lady Gaga is Stefani Germonatta’s stage name. Whether she is in a film or in concert, Lady Gaga is the name in lights (or credits), not Stefani Germonatta. David Bowie took on a whole new persona for each era of his music. In fact, he may be responsible for some of the most iconic performer personae of all time.

Check out this video to see how these identities were integral to his career.

David Bowie's Personae

Of course, many of us don’t necessarily utilize persona on David Bowie’s level (no matter how much we wish we could). But, as human beings, we inherently understand the concept of identity. In this way, characters within our own works would understand the concept of persona as well.

Persona is, at its core, the fact that humans behave a certain way. Our actions, our personality, our “mask” is our persona, which can change depending on whether we are alone, with parents, with coworkers, or with friends. But just because our persona can change, doesn’t mean it always will. Your characters also fall somewhere on this spectrum, so it’s worth considering when you’re designing your characters or narrators.

What is Personification?

You’ve mastered persona, but don’t get it twisted: personification is its own thing entirely. Click the link below to learn about personification, and understand how it fits into your literary technique arsenal.

Up Next: Personification Explained →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- What are the 12 Principles of Animation — Ultimate Guide

- What is Pacing in Writing — And Why It’s So Important

- 2 Pinterest

- Expert Publishing Services

- 917-922-1339

- [email protected]

What Is Your Author Persona?

What is a Beta Reader? Receive Free Feedback on Your Work

Why Do Authors Use Pen Names?

- tips and tricks

Whether you write romance novels or space operas, self-help or poetry, business advice or kidlit, you have an author persona! Identifying your persona can give you insights into your process, illustrate what inspires you, and help you stay focused on your goals.

Read on to find out about different author personas and those of your writing friends and colleagues. You never know what might speak to you or what might encourage you to take your writing to the next level!

The rainy-day romantic

You are a rainy-day romantic! If there’s anything you like more than watching raindrops spatter against your windowpane, it’s writing a beautiful description of raindrops glistening like little opals on glass. Or of tiny seed pearls sewn into the lace of a cuff. Or of how the clink of silver on china sounds like lost hope. Your voice is expressive and poetic, and you write lush, lovely books that transport readers to beautiful places and times while taking their hearts on emotional rollercoasters.

If you’re a rainy-day romantic, you might be a little worried about how often you find yourself lost in your daydreams, but embrace that tendency! It’s part of what feeds your creativity. Try journaling what goes through your mind at idle moments or keep a vision board of beautiful pictures and phrases that inspire you.

Your love of beauty means that when the time comes, getting your book’s cover design just right will be key—and then a video book trailer will let you captivate your readers with a few choice words and images drawn from your active imagination.

Schedules might not work for you, so lean into your writing when the literary muse finds you, and at other times, engage with other aspects of your artistry! Paint, sing in the sunshine, dance in the rain—just create!

The coffee-shop connoisseur

You are a coffee-shop connoisseur! Fueled by java and the warm buzz of human connection, you often find there’s nothing like a little overheard conversation to invigorate your writing. You’ve long-since figured out which table is yours: exactly the right amount of workspace, a handy electrical outlet, good natural light, a clear path to the bathroom, and ready access to refills. Your quick mind zings with fresh ideas, some of which come at you faster than you can type—but that’s okay because there are always more where they came from. You love a fast-paced plot (or strong central thesis) and prefer not to get bogged down in flowery descriptions or tangents. Smart, sassy, and to the point—that’s you!

Coffee-shop connoisseurs like you tend to be extroverts (or socially skilled introverts) who thrive on connection and community. Have you thought about getting a writing buddy ? Or taking your social media up a notch? (Elite can help you connect to others with our social strategy sessions!) You might be happily surprised by the caffeine-free energy you gain by writing with others!

That’s not to say you shouldn’t spend time alone. Consider making weekly coffee dates with yourself—put them in the calendar and account for the ten bucks in your budget planning. Guilt-free creative time is key for you.

Keep your eye on the prize by dreaming of your amazing launch party . We can see it now—canapes and coffee and champagne on ice! (Please invite us?)

The park-bench poet

You are a park-bench poet! For you, nature is your muse. Whether it’s the play of sunlight on the gold-green of spring grass or the summer sizzle of a cicada song or the crumpled-paper crunch of fall leaves or the almost-taste of early snow, your writing is infused with and informed by the world around you. Just like the seasons whisper their secrets to you, people’s faces tell you their stories without them saying a word. You don’t mind being part of a crowd, and yet you are always apart—seeing everything, understanding so much, carefully judging what to say and what to save up for your next book.

As an observant park-bench poet, you might find it well worth your time to write yourself a few notes when you’re people-watching . Note their facial expressions, body language, or unusual turns of phrase. If you’re artistically inclined, maybe add a few rough sketches. This is one really rewarding way to infuse your characters with vibrant realism.

Your finely tuned senses and sensibilities mean that it’s crucial to you that you get things right. Don’t fall into the trap of endlessly revising, however! Trust yourself and your instincts, and when you have a finished manuscript, finding the right editing services will ensure your book is top notch.

Getting things down on paper is crucial, but be certain to feed your senses as well. Make sure you spend time outside every week to take in the natural world and your surroundings. And leave your phone in the car or switch it off. There will be time enough to reengage with the bustling world.

The sporadic napkin scribbler