An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

ten Cate O, Custers EJFM, Durning SJ, editors. Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-64828-6_1

Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students [Internet].

Chapter 1 introduction.

Olle ten Cate .

Affiliations

Published online: November 7, 2017.

This chapter introduces the concept of clinical reasoning. It attempts to define what clinical reasoning is and what its features are. Solving clinical problems involves the ability to reason about causality of pathological processes, requiring knowledge of anatomy and the working and pathology of organ systems, and it requires the ability to compare patient problems as patterns with instances of illness scripts of patients the clinician has seen in the past and stored in memory.

The purpose of the book, supporting the teaching of clinical reasoning before students enter the clinical arena, faces the paradoxical problem of the lack of clinical experience that is so essential for building proficiency in clinical reasoning. So where to start if students are to be best prepared for first clinical encounters?

The method of case-based clinical reasoning is summarized and explained in its potential to provide early rudimentary illness scripts through elaboration and systematic discussion of the courses of action between the initial presentation of the patient and the final steps of clinical management. Meanwhile, the method requires student to apply knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and pathology.

The CBCR method has been applied successfully in several medical schools over a period of decades, and support for its validity is provided.

This chapter provides a general background and summarizes the CBCR method.

Clinical reasoning is a professional skill that experts agree is difficult and takes time to acquire, and, once you have the skill, it is difficult to explain what you actually do when you apply it—clinical reasoning then sometimes even feels as an easy process. The input, a clinical problem or a presenting patient, and the outcome, a diagnosis and/or a plan for action, are pretty clear, but what happens in the doctor’s mind in the meantime is quite obscure. It can be a very short process, happening in seconds, but it can also take days or months. It can require deliberate, painstaking thinking, consultation of written sources, and colleague opinions, or it may just seem to happen effortless. And “reasoning” is such a nicely sounding word that doctors would agree captures what they do, but is it always reasoning? Reasoning sounds like building a chain of thoughts, with causes and consequences, while doctors sometimes jump at a conclusion, sometimes before they even realize they are clinically reasoning. Is that medical magic? No, it’s not. Laypeople do the same. Any adult witnessing a motorcycle accident and seeing a victim on the street showing a lower limb in a strange angle will instantly “reason” the diagnosis is a fracture. Other medical conditions are less obvious and require deep thinking or investigations or literature study. Whatever presentation, doctors need to have the requisite skills to tackle the medical problems of patients that are entrusted to their care. No matter how obscure clinical reasoning is, students need to acquire that ability. So how does a student begin to learn clinical reasoning? How must teachers organize the training of students?

Case-based clinical reasoning (CBCR) education is a design of training of preclinical medical students, in small groups, in the art of coping with clinical problems as they are encountered in practice. As will be apparent from the description later in this chapter, CBCR is not identical to problem-based learning (Barrows and Tamblyn 1980 ), although some features (small groups, no traditional teacher role) show resemblance. While PBL is intended as a method to arrive at personal educational objectives and subsequently acquire new knowledge (Schmidt 1983 ), CBCR has a focus on training in the application of systematically acquired prior knowledge, but now in a clinical manner. It aims at building illness scripts—mental representations of diseases—while at the same time supports the acquisition of a diagnostic thinking habit. CBCR is not an algorithm or a heuristic to be used in clinical practice to efficiently solve a new medical problem. CBCR is no more and no less than educational method to acquire clinical reasoning skill. That is what this book is about.

The elaboration of the method (Part II and III of the book) is preceded in Part I by chapters on the general background of clinical reasoning and its teaching.

- What Is Clinical Reasoning?

Clinical reasoning is usually defined in a very general sense as “The thinking and decision -making processes associated with clinical practice” (Higgs and Jones 2000 ) or simply “diagnostic problem solving” (Elstein 1995 ).

For the purpose of this book, we define clinical reasoning as the mental process that happens when a doctor encounters a patient and is expected to draw a conclusion about (a) the nature and possible causes of complaints or abnormal conditions of the patient, (b) a likely diagnosis, and (c) patient management actions to be taken. Clinical reasoning is targeted at making decisions on gathering diagnostic information and recommending or initiating treatment. The mental reasoning process is interrupted to collect information and resumed when this information has arrived.

It is well established that clinicians have a range of mental approaches to apply. Somewhat simplified, they are categorized in two thinking systems, sometimes subsumed under the name dual-process theory (Eva 2005 ; Kassirer 2010 ; Croskerry 2009 ; Pelaccia et al. 2011 ). Based in the work of Croskerry ( 2009 ) and the Institute of Medicine (Balogh et al. 2015 ), Fig. 1.1 shows a model of how clinical reasoning and the use of System 1 and 2 thinking can be conceptualized graphically.

A model of clinical reasoning (Adapted from Croskerry 2009)

The first thinking approach is rapid and requires little mental effort. This mode has been called System 1 thinking or pattern recognition , sometimes referred to as non-analytical thinking. Pattern recognition happens in various domains of expertise. Based on studies in chess, it is estimated that grand master players have over 50,000 patterns available in their memory, from games played and games studied (Kahneman and Klein 2009 ). These mental patterns allow for the rapid comparison of a pattern in a current game with patterns stored in memory and for a quick decision which move to make next. This huge mental library of patterns may be compared with the mental repository of illness scripts that an experienced clinician has and that allows for the rapid recognition of a pattern of signs and symptoms in a patient with patients encountered in the past (Feltovich and Barrows 1984 ; Custers et al. 1998 ). See Box 1.1 .

Box 1.1 Illness Script

An illness script is a general representation in the physician’s mind of an illness. An illness script includes details on typical causal or associated preceding features (“enabling conditions”); the actual pathology (“fault”); the resulting signs, symptoms, and expected diagnostic findings (“consequences”); and, added to the original illness script definition (Feltovich and Barrows 1984 ), the most likely course and prognosis with suitable management options (“management”). An illness script may be stored as one comprehensive unit in the long-term memory of the physician. It can be triggered to be retrieved during new clinical encounters, to facilitate comparison and contrast, in order to generate a diagnostic hypothesis.

A mental matching process can lead to an instant recognition and generation of a hypothesis, if sufficient features of the current patient resemble features of a stored illness script.

Next to this rapid mental process, clinicians use System 2 thinking: the analytical thinking mode of presumed causes-and-effects reasoning that is slow and takes effort and is used when a System 1 process does not lead to an acceptable proposition to act. Analytic, often pathophysiological, thinking is typically the approach that textbooks of medicine use to explain signs and symptoms related to pathophysiological conditions in the human body. Both approaches are needed in clinical health care, to arrive at decisions and actions and to retrospectively justify actions taken. The two thinking modes can be viewed on a cognitive continuum between instant recognition and a reasoning process that may take a long time (Kassirer et al. 2010 ; Custers 2013 ). In routine medical practice, the rapid System 1 thinking prevails. This thinking often leads to correct decisions but is not infallible. However, the admonition to slow down the thinking when System 1 thinking fails and move to System 2 thinking may not lead to more accurate decisions (Norman et al. 2014 ). In fact, emerging fMRI studies seem to indicate that in complex cases, inexperienced learners search for rule-based reasoning solutions (System 2), while experienced clinicians keep searching for cases from memory (System 1) (Hruska et al. 2015 ).

- How to Teach Clinical Reasoning to Junior Students?

It is not exactly clear how medical students acquire clinical reasoning skills (Boshuizen and Schmidt 2000 ), but they eventually do, whether they had a targeted training in their curriculum or not. Williams et al. found a large difference in reasoning skill between years of clinical experience and across different schools (Williams et al. 2011 ). Even if reasoning skill would develop naturally across the years of medical training, it does not mean that educational programs cannot improve.

One way to approach the training of students in clinical reasoning is to focus on things that can go wrong in the practice of clinical reasoning and on threats to effective thinking in clinical care. Box 1.2 shows the most prevalent errors and cognitive biases in clinical reasoning (Graber et al. 2005 ; Kassirer et al. 2010 ). See also Chap. 3 .

Box 1.2 Summary of Prevalent Causes of Errors and Cognitive Biases

Errors (graber et al. 2005 ; kassirer et al. 2010 ).

Lack or faulty knowledge

Omission of, or faulty, data gathering and processing

Faulty estimation of disease prevalence

Faulty test result interpretation

Lack of diagnostic verification

Biases (Balogh et al. 2015 )

Anchoring bias and premature closure (stop search after early explanation)

Affective bias (emotion-based deviance from rational judgment)

Availability bias (dominant recall of recent or common cases)

Context bias (contextual factors that mislead)

In general, diagnostic errors are considered to occur too often in practice (McGlynn et al. 2015 ; Balogh et al. 2015 ), and it is important that student preparation for clinical encounters be improved (Lee et al. 2010 ). In a qualitative study, Audétat et al. observed five prototypical clinical reasoning difficulties among residents: generating hypotheses to guide data gathering, premature closure, prioritizing problems, painting an overall picture of the clinical situation, and elaborating a management plan (Audétat et al. 2013 ), not unlike the prevalent errors in clinical practice as summarized in Box 1.2 . Errors in clinical reasoning pertain to both System 1 and System 2 thinking and cognitive biases causing errors are not easily amenable to teaching strategies. An inadequate knowledge base appears the most consistent reason for error (Norman et al. 2017 ). A number of authors have recommended tailored teaching strategies for clinical reasoning (Rencic 2011 ; Guerrasio and Aagaard 2014 ; Posel et al. 2014 ). Most approaches pertain to education in the clinical workplace. Box 1.3 gives a condensed overview.

Let students

- Maximize learning by remembering many patient encounters.

- Recall similar cases as they increase experience.

- Build a framework for differential diagnosis using anatomy, pathology, and organ systems combined with semantic qualifiers: age, gender, ethnicity, and main complaint.

- Differentiate between likely and less likely but important diagnoses.

- Contrast diagnoses by listing necessary history questions and physical exam maneuvers in a tabular format and indicating what supports or does not support the respective diagnoses.

- Utilize epidemiology, evidence, and Bayesian reasoning.

- Practice deliberately; request and reflect on feedback; and practice mentally.

- Generate self-explanations during clinical problem solving.

- Talk in buzz groups at morning reports with oral and written patient data.

- Listen to clinical teachers reasoning out loud.

- Summarize clinical cases often using semantic qualifiers and create problem representations.

One dominant approach that clinical educators use when teaching students to solve medical problems is ask them to analyze pathophysiologically, in other words to use System 2 thinking. While this seems the only option with students who do not possess a mental library of illness scripts to facilitate System 1 thinking, those teachers teach something they usually do not do themselves when solving clinical problems This teaching resembles the “do as I say, not as I do” approach, in part because they simply cannot express “how they do” when they engaged in clinical reasoning.

In a recent review of approaches to the teaching of clinical reasoning, Schmidt and Mamede identified two groups of approaches: a predominant serial-cue approach (teachers provide bits of patient information to students and ask them to reason step by step) and a rare whole-task (or whole-case) approach in which all information is presented at once. They conclude that there is little evidence for the serial-cue approach, favored by most teachers and recommend a switch to whole-case approaches (Schmidt and Mamede 2015 ). While cognitive theory does support whole-task instructional techniques (Vandewaetere et al. 2014 ), the description of a whole-case in clinical education is not well elaborated. Evidently a whole-case cannot include a diagnosis and must at least be partly serial. But even if all the information that clinicians in practice face is provided to students all at once, the clinical reasoning process that follows has a serial nature, even if it happens quickly. Schmidt and Mamede’s proposal to first develop causal explanations, second to encapsulate pathophysiological knowledge, and third to develop illness scripts (Schmidt and Mamede 2015 ) runs the risk of separating biomedical knowledge acquisition from clinical training and regressing to a Flexnerian curriculum. Flexner advocated a strong biomedical background before students start dealing with patients (Flexner 1910 ). This separation is currently not considered the most useful approach to clinical reasoning education (Woods 2007 ; Chamberland et al. 2013 ).

Training students in the skill of clinical reasoning is evidently a difficult task, and Schuwirth rightly once posed the question “Can clinical reasoning be taught or can it only be learned?” (Schuwirth 2002 ). Since the work of Elstein and colleagues, we know that clinical reasoning is not a skill that is trainable independent of a large knowledge base (Elstein et al. 1978 ). There simply is not an effective and teachable algorithm of clinical problem solving that can be trained and learned, if there is no medical knowledge base. The actual reasoning techniques used in clinical problem solving can be explained rather briefly and may not be very different from those of a car mechanic. Listen to the patient (or the car owner), examine the patient (or the car), draw conclusions, and identify what it takes to solve the problem. There is not much more to it. In difficult cases, medical decision-making can require knowledge of Bayesian probability calculations, understanding of sensitivity and specificity of tests (Kassirer et al. 2010 ), but clinicians seldom use these advanced techniques explicitly at the bedside.

These recommendations are of no avail if students do not have background knowledge, both about anatomical structures and pathophysiological processes and about patterns of signs and symptoms related to illness scripts. When training medical students to think like doctors, we face the problem that we cannot just look how clinicians think and just ask students to mimic that technique. That is for two reasons: one is that clinicians often cannot express well how they think, and the second is simply that the huge knowledge base required to think like an experienced clinician is simply not present in students.

As System 1 pattern recognition is so overwhelmingly dominant in the clinician’s thinking (Norman et al. 2007 ), the lack of a knowledge base prohibits junior students to think like a doctor. It is clear that students cannot “recognize” a pattern if they do not have a similar pattern in their knowledge base. It is unavoidable that much effort and extensive experience are needed before a reasonable repository of illness scripts is built that can serve as the internal mirror of patterns seen in clinical practice. Ericsson’s work suggests that it may take up to 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to acquire expertise in any domain, although there is some debate about this volume (Ericsson et al. 1993 ; Macnamara et al. 2014 ). Clearly, students must see and experience many, many cases and construct and remember illness scripts. What a curriculum can try to offer is just that, i.e., many clinical encounters, in clinical settings or in a simulated environment. Clinical context is likely to enhance clinical knowledge, specifically if students feel a sense of responsibility or commitment (Koens et al. 2005 ; Koens 2005 ). This sense of commitment in practice relates to the patient, but it can also be a commitment to teach peers.

System 2 analytic reasoning is clearly a skill that can be trained early in a curriculum (Ploger 1988 ). Causal reasoning, usually starting with pathology (a viral infection of the liver) and a subsequent effect (preventing the draining of red blood cell waste products) and ending with resulting symptoms (yellow stains in the blood, visible in the sclerae of the eyes and in the skin, known as jaundice or icterus), can be understood and remembered, and the reasoning can include deeper biochemical or microbiological explanations (How does it operate the chemical degradation of hemoglobin? Which viruses cause hepatitis? How was the patient infected?). This basically is a systems-based reasoning process. The clinician however must reason in the opposite direction, a skill that is not simply the reverse of this chain of thought, as there may be very different causes of the same signs and symptoms (a normal liver, but an obstruction in the bile duct, or a normal liver and bile duct, but a profuse destruction of red blood cells after an immune reaction). So analytic reasoning is trainable, and generating hypotheses of what may have caused the symptoms requires a knowledge base of possible physiopathology mechanisms. That can be acquired step by step, and many answers to analytic problems can be found in the literature. But clearly, System 2 reasoning too requires prior knowledge. So both a basic science knowledge base and a mental illness script repository must be available.

The case-based clinical reasoning training method acknowledges this difficulty and therefore focuses on two simultaneous approaches (1) building illness scripts from early on in the curriculum, beginning with simple cases and gradually building more complex scripts to remember, and (2) conveying a systematic, analytic reasoning habit starting with patient presentation vignettes and ending with a conclusion about the diagnosis, the disease mechanism, and the patient management actions to be taken.

Summary of the CBCR Method

When applying these principles to preclinical classroom teaching, a case-based approach is considered superior to other methods (Kim et al. 2006 ; Postma and White 2015 ). Case-based clinical reasoning was designed at the Academic Medical Center of University of Amsterdam in 1992, when a new undergraduate medical curriculum was introduced (ten Cate and Schadé 1993 ; ten Cate 1994 , 1995 ). This integrated medical curriculum with multidisciplinary block modules of 6–8 weeks had existed since 10 years, but was found to lack a proper preparation of students to think like a doctor before entering clinical clerkships. Notably, while all block modules stressed the knowledge acquisition structured in a systematic way, usually based on organ systems and resulting in a systems knowledge base, a longitudinal thread of small group teaching was created to focus on patient-oriented thinking, with application of acquired knowledge (ten Cate and Schadé 1993 ). This CBCR training was implemented in curriculum years 2, 3, and 4, at both medical schools of the University of Amsterdam and the Free University of Amsterdam, which had been collaborating on curriculum development since the late 1980s. After an explanation of the method in national publications (ten Cate 1994 , 1995 ), medical schools at Leiden and Rotterdam universities adopted variants of it. In 1997 CBCR was introduced at the medical school of Utrecht University with minor modifications and continued with only little adaptations throughout major undergraduate medical curriculum changes in 1999, 2006, and 2015 until the current day (2017).

CBCR can be summarized as the practicing of clinical reasoning in small groups. A CBCR course consists of a series of group sessions over a prolonged time span. This may be a semester, a year, or usually, a number of years. Students regularly meet in a fixed group of 10–12, usually every 3–4 weeks, but this may be more frequent. The course is independent of concurrent courses or blocks. The rationale for this is that CBCR stresses the application of previously acquired knowledge and should not be programmed as an “illustration” of clinical or basic science theory. More importantly, when the case starts, students must not be cued in specific directions or diagnoses, which would be the case if a session were integrated in, say, a cardiovascular block. A patient with shortness of breath would then trigger too easily toward a cardiac problem.

CBCR cases, always titled with age, sex, and main complaint or symptom, consist of an introductory case vignette reflecting the way a patient presents at the clinician’s office. Alternatively, two cases with similar presentations but different diagnoses may be worked through in one session, usually later in the curriculum when the thinking process can be speeded up. The context of the case may be at a general practitioner’s office, at an emergency department, at an outpatient clinic, or at admission to a hospital ward. The case vignette continues with questions and assignments (e.g., What would be first hypotheses based on the information so far? What diagnostic tests should be ordered? Draw a table mapping signs and symptoms against likelihood of hypotheses ), at fixed moments interrupted with the provision of new findings about the patient from investigations (more extensive history, additional physical examination, or new results of diagnostic tests), distributed or read out loud by a facilitator during the session at the appropriate moment. A full case includes the complete course of a problem from the initial presentation to follow-up after treatment, but cases often concentrate on key stages of this course. Case descriptions should refer to relevant pathophysiological backgrounds and basic sciences (such as anatomy, biochemistry, cell biology, physiology) during the case.

The sessions are led by three (sometimes two) students of the group. They are called peer teachers and take turns in this role over the whole course. Every student must act as a peer teacher at multiple sessions across the year. Peer teachers have more information in advance about the patient and disclose this information at the appropriate time during the session, in accordance with instructions they receive in advance. In addition, a clinician is present. Given the elaborated format and case description, this teacher only acts as a consultant, when guidance is requested or helpful, and indeed is called “consultant” throughout all CBCR education.

Study materials include a general study guide with explanations of the rules, courses of action, assessment procedures, etc. (see Chap. 10 ): a “student version ” of the written CBCR case material per session, a “peer teacher version” of the CBCR case per session with extra information and hints to guide the group, and a full “consultant version” of the CBCR case per session. Short handouts are also available for all students, covering new clinical information when needed in the course of the diagnostic process. Optionally, homemade handouts can be prepared by peer teachers. The full consultant version of the CBCR case includes all answers to all questions in detail, sufficient to enable guidance by a clinician who is not familiar with the case or discipline, all suggestions and hints for peer teachers, and all patient information that should be disclosed during the session. Examples are shown in Appendices of this book.

Students are assessed at the end of the course on their knowledge of all illnesses and to a small extent on their active participation as a student and a peer teacher (see Chap. 7 ).

- Essential Features of CBCR Education

While a summary is given above, and a detailed procedural description is given in Part II, it may be helpful to provide some principles to help understand some of the rationale behind the CBCR method.

Switching Between System-Oriented Thinking and Patient-Oriented Thinking

It is our belief that preclinical students must learn to acquire both system-oriented knowledge and patient-oriented knowledge and that they need to practice switching between both modes of thinking (Eva et al. 2007 ). In that sense, our approach not only differs from traditional curricula with no training in clinical reasoning but also from curricula in which all education is derived from clinical presentations (Mandin et al. 1995 , 1997 ).

By scheduling CBCR sessions spread over the year, with each session requiring the clinical application of system knowledge of previous system courses, this practice of switching is stimulated. It is important to prepare and schedule CBCR cases carefully to enable this knowledge application. It is inevitable, because of differential diagnostic thinking, that cases draw upon knowledge from different courses and sometimes knowledge that may not have been taught. In that case, additional information may be provided during the case discussion. Peer teachers often have an assignment to summarize relevant system information between case questions in a brief presentation (maximum 10 min), to enable further progression.

Managing Cognitive Load and the Development of Illness Scripts

Illness scripts are mental representations of disease entities combining three elements in a script (Custers et al. 1998 ; Charlin et al. 2007 ): (1) factors causing or preceding a disease, (2) the actual pathology, and (3) the effect of the pathology showing as signs, symptoms, and expected diagnostic findings. While some authors, including us, add (4) course and management as the fourth element (de Vries et al. 2006 ), originally the first three, “enabling conditions,” “fault,” and “consequences,” were proposed to constitute the illness script (Feltovich and Barrows 1984 ). Illness scripts are stored as units in the long-term memory that are simultaneously activated and subsequently instantiated (i.e., recalled instantly) when a pattern recognition process occurs based on a patient seen by a doctor. This process is usually not deliberately executed, but occurs spontaneously. Illness scripts have a temporal nature like a film script, because of their cause and effect features, which enables clinicians to quickly take a next step, suggested by the script, in managing the patient. “Course and management” can therefore naturally be considered part of the script.

A shared explanation why illness scripts “work” in clinical reasoning is that the human working memory is very limited and does not allow to process much more than seven units or chunks of information at a time (Miller 1956 ) and likely less than that. Clinicians cannot process all separate signs and symptoms, history, and physical examination information simultaneously—that would overload their working memory capacity, but try to use one label to combine many bits of information in one unit (e.g., the illness script “diabetes type II” combines its enabling factors, pathology, signs and symptoms, disease course, and standard treatment in one chunk). If necessary, those units can be unpacked in elements (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2 ).

One information chunk in the working memory may be decomposed in smaller chunks in the long-term memory (Young et al. 2014)

To create illness scripts stored in the long-term memory, students must learn to see illnesses as a unit of information. In case-based clinical reasoning education, students face complete patient scripts, i.e., with enabling conditions (often derived from history taking) to consequences (as presenting signs and symptoms). Although illness scripts have an implicit chronology, from a clinical reasoning perspective, there is an adapted chronology of (a) consequences → (b) enabling conditions → (c) fault and diagnosis → (d) course and management, as the physician starts out observing the signs and symptoms, then takes a history, performs a physical examination, and orders tests if necessary before arriving at a conclusion about the “fault.” To enable building illness script units in the long-term memory, students must start out with simple, prototype cases that can be easily remembered. CBCR aims to develop in second year medical students stable but still somewhat limited illness scripts. This still limited repository should be sufficient to quickly recognize the causes, symptoms, and management of a limited series of common illnesses, and handle prototypical patient problems in practice if they would encounter these, resonating with Bordage’s prototype approach (Bordage and Zacks 1984 ; Bordage 2007 ). See Chap. 3 . The assessment of student knowledge at the end of a CBCR course focuses on the exact cases discussed, including, of course, the differential diagnostic considerations that are activated with the illness script, all to reinforce the same carefully chosen illness scripts. The aim is to provide a foundation that enables the addition in later years of variations to the prototypical cases learned, to enrich further illness script formation and from there add new illness scripts. We believe that working with whole, but not too complex, cases in an early phase in the medical curriculum serves to help students in an early phase in the medical curriculum to learn to recognize common patterns.

Educational Philosophies: Active Reasoning by Oral Communication and Peer Teaching

A CBCR education in the format elaborated in this book reflects the philosophy that learning clinical reasoning is enhanced by reasoning aloud. The small group arrangement, limited to no more than about 12 students, guarantees that every student actively contributes to the discussion. Even when listening, this group size precludes from hiding as would be a risk in a lecture setting.

Students act as peer teachers for their fellow students. Peer teaching is an accepted educational method with a theoretical foundation (ten Cate and Durning 2007 ; Topping 1996 ). It is well known that taking the role of teacher for peers stimulates knowledge acquisition in a different and often more productive way than studying for an exam (Bargh and Schul 1980 ). Social and cognitive congruence concepts explain why students benefit from communicating with peers or near-peers and should understand each other better than when students communicate with expert teachers (Lockspeiser et al. 2008 ). The peer teaching format used in CBCR is an excellent way to achieve active participation of all students during small group education. An additional benefit of using peer teachers is that they are instrumental in the provision of just-in-time information about the clinical case for their peers in the CBCR group, e.g., as a result of a diagnostic test that was proposed to be ordered.

Case-based clinical reasoning has most of the features that are recommended by Kassirer et al.: “First, clinical data are presented, analyzed and discussed in the same chronological sequence in which they were obtained in the course of the encounter between the physician and the patient. Second, instead of providing all available data completely synthesized in one cohesive story, as is in the practice of the traditional case presentation, data are provided and considered on a little at a time. Third, any cases presented should consist of real, unabridged patient material. Simulated cases or modified actual cases should be avoided because they may fail to reflect the true inconsistencies, false leads, inappropriate cues, and fuzzy data inherent in actual patient material. Finally, the careful selection of examples of problem solving ensures that a reasonable set of cognitive concepts will be covered” (Kassirer et al. 2010 ). While we agree with the third condition for advanced students, i.e., in clerkship years, for pre-clerkship medical students, a prototypical illness script is considered more appropriate and effective (Bordage 2007 ). The CBCR method also matches well with most recommendations on clinical reasoning education (see Box 1.3 ).

Chapter 4 of this book describes six prerequisites for clinical reasoning by medical students in the clinical context: having clinical vocabulary, experience with problem representation, an illness script mental repository, a contrastive learning approach, hypothesis-driven inquiry skill, and a habit of diagnostic verification. The CBCR approach helps to prepare students with most of these prerequisites.

Indications for the Effectiveness of the CBCR Method

The CBCR method finds its roots in part in problem-based learning (PBL) and other small group active learning approaches. Since the 1970s, various small group approaches have been recommended for medical education, notably PBL (Barrows and Tamblyn 1980 ) and team-based learning (TBL) (Michaelsen et al. 2008 ). In particular PBL has gained huge interest in the 1980s onward, due to the developmental work done by its founder Howard Barrows from McMaster University in Canada and from Maastricht University in the Netherlands, which institution derived its entire identity to a large part from problem-based learning. Despite significant research efforts to establish the superiority of PBL curricula, the general outcomes have been somewhat less than expected (Dolmans and Gijbels 2013 ). However, many studies on a more detailed level have shown that components of PBL are effective. In a recent overviews of PBL studies, Dolmans and Wilkerson conclude that “a clearly formulated problem, an especially socially congruent tutor, a cognitive congruent tutor with expertise, and a focused group discussion have a strong influence on students’ learning and achievement” (Dolmans and Wilkerson 2011 ). These are components that are included in the CBCR method.

While there has not been a controlled study to establish the effect of a CBCR course per se, compared to an alternative approach to clinical reasoning training, there is some indirect support for its validity, apart from the favorable reception of the teaching model among clinicians and students over the course of 20 years and different schools. A recent publication by Krupat and colleagues showed that a “case-based collaborative learning” format, including small group work on patient cases with sequential provision of patient information, led to higher scores of a physiology exam and high appreciation among students, compared with education using a problem-based learning format (Krupat et al. 2016 ). A more indirect indication of its effectiveness is shown in a comparative study among three schools in the Netherlands two decades ago (Schmidt et al. 1996 ). One of the schools, the University of Amsterdam medical school, had used the CBCR training among second and third year students at that time (ten Cate 1994 ). While the study does not specifically report on the effects of clinical reasoning education, Schmidt et al. show how students of the second and third year in this curriculum outperform students in both other curricula in diagnostic competence.

CBCR as an Approach to Ignite Curriculum Modernization

Since 2005, the method of CBCR has been used as leverage for undergraduate medical curriculum reform in Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan (ten Cate et al. 2014 ). It has proven to be useful in medical education contexts with heavily lecture-based curricula—likely because the method can be applied within an existing curriculum, causing little disruption, while also being exemplary for recommended modern medical education (Harden et al. 1984 ). It stimulates integration, and the method is highly student-centered and problem-based. While observing CBCR in practice, a school can consider how these features can also be applied more generally in preclinical courses. This volume provides a detailed description that allows a school to pilot CBCR for this purpose.

- Audétat, M.-C., et al. (2013). Clinical reasoning difficulties: A taxonomy for clinical teachers. Medical Teacher, 35 (3), e984–e989. Available at: http://www .ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pubmed/23228082 . [ PubMed : 23228082 ]

- Balogh, E. P., Miller, B. T., & Ball, J. R. (2015). Improving diagnosis in healthcare . Washington, DC: The Institute of Medicine and the National Academies Press. Available at: http://www .nap.edu/catalog /21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care . [ PubMed : 26803862 ]

- Balslev, T., et al. (2015). Combining bimodal presentation schemes and buzz groups improves clinical reasoning and learning at morning report. Medical Teacher, 37 (8), 759–766. Available at: http: //informahealthcare .com/doi/abs/10.3109/0142159X .2014.986445 . [ PubMed : 25496711 ]

- Bargh, J. A., & Schul, Y. (1980). On the cognitive benefits of teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72 (5), 593–604. [ CrossRef ]

- Barrows, H. S., & Tamblyn, R. M. (1980). Problem-based learning. An approach to medical education . New York: Springer.

- Bordage, G. (2007). Prototypes and semantic qualifiers: From past to present. Medical Education, 41 (12), 1117–1121. [ PubMed : 18045363 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bordage, G., & Zacks, R. (1984). The structure of medical knowledge in the memories of medical students and general practitioners: Categories and prototypes. Medical Education, 18 (11), 406–416. [ PubMed : 6503748 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Boshuizen, H., & Schmidt, H. (2000). The development of clinical reasoning expertise. In J. Higg & M. Jones (Eds.), Clinical reasoning in the health professions (pp. 15–22). Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford.

- Bowen, J. L. (2006). Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. The New England Journal of Medicine, 355 (21), 2217–2225. [ PubMed : 17124019 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chamberland, M., et al. (2013). Students’ self-explanations while solving unfamiliar cases: The role of biomedical knowledge. Medical Education, 47 (11), 1109–1116. [ PubMed : 24117557 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chamberland, M., et al. (2015). Self-explanation in learning clinical reasoning: The added value of examples and prompts. Medical Education, 49 , 193–202. [ PubMed : 25626750 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Charlin, B., et al. (2007). Scripts and clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 41 (12), 1178–1184. [ PubMed : 18045370 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Croskerry, P. (2009). A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84 (8), 1022–1028. [ PubMed : 19638766 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Custers, E. J. F. M. (2013). Medical education and cognitive continuum theory: An alternative perspective on medical problem solving and clinical reasoning. Academic Medicine, 88 (8), 1074–1080. [ PubMed : 23807108 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Custers, E. J. F. M., Boshuizen, H. P. A., & Schmidt, H. G. (1998). The role of illness scripts in the development of medical diagnostic expertise: Results from an interview study. Cognition and Instruction, 14 (4), 367–398. [ CrossRef ]

- de Vries, A., Custers, E., & ten Cate, O. (2006). Teaching clinical reasoning and the development of illness scripts: Possibilities in medical education. [Dutch]. Dutch Journal of Medical Education, 25 (1), 2–2.

- Dolmans, D., & Gijbels, D. (2013). Research on problem-based learning: Future challenges. Medical Education, 47 (2), 214–218. Available at: http://www .ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pubmed/23323661 . Accessed 26 May 2013. [ PubMed : 23323661 ]

- Dolmans, D. H. J. M., & Wilkerson, L. (2011). Reflection on studies on the learning process in problem-based learning. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 16 (4), 437–441. Available at: http://www .pubmedcentral .nih.gov/articlerender .fcgi?artid=3166125&tool =pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract . Accessed 11 Mar 2012. [ PMC free article : PMC3166125 ] [ PubMed : 21861136 ]

- Elstein, A. (1995). Clinical reasoning in medicine. In J. Higgs & M. Jones (Eds.), Clinical reasoning in the health professions (pp. 49–59). Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Elstein, A. S., Shulman, L. S., & Sprafka, S. A. (1978). Medical problem solving. In An analysis of clinical reasoning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ericsson, K. A., et al. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100 (3), 363–406. [ CrossRef ]

- Eva, K. W. (2005). What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 39 (1), 98–106. [ PubMed : 15612906 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eva, K. W., et al. (2007). Teaching from the clinical reasoning literature: Combined reasoning strategies help novice diagnosticians overcome misleading information. Medical Education, 41 (12), 1152–1158. [ PubMed : 18045367 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Feltovich, P., & Barrows, H. (1984). Issues of generality in medical problem solving. In H. G. Schmidt & M. L. de Voider (Eds.), Tutorials in problem-based learning (pp. 128–170). Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Flexner, A., 1910. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching . Repr. ForgottenBooks. Boston: D.B. Updike, the Merrymount Press.

- Graber, M. L., Franklin, N., & Gordon, R. (2005). Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165 (13), 1493–1499. [ PubMed : 16009864 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guerrasio, J., & Aagaard, E. M. (2014). Methods and outcomes for the remediation of clinical reasoning. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 1607–1614. [ PMC free article : PMC4242871 ] [ PubMed : 25092006 ]

- Harden, R. M., Sowden, S., & Dunn, W. (1984). Educational strategies in curriculum development: The SPICES model. Medical Education, 18 , 284–297. [ PubMed : 6738402 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Higgs, J., & Jones, M. (2000). In J. Higgs & M. Jones (Eds.), Clinical reasoning in the health professions (2nd ed.). Woburn: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hruska, P., et al. (2015). Hemispheric activation differences in novice and expert clinicians during clinical decision making. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21 , 1–13. [ PubMed : 26530736 ]

- Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. The American Psychologist, 64 (6), 515–526. [ PubMed : 19739881 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kassirer, J. P. (2010). Teaching clinical reasoning: Case-based and coached. Academic Medicine, 85 (7), 1118–1124. [ PubMed : 20603909 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kassirer, J., Wong, J., & Kopelman, R. (2010). Learning clinical reasoning (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Kim, S., et al. (2006). A conceptual framework for developing teaching cases: A review and synthesis of the literature across disciplines. Medical Education, 40 (9), 867–876. [ PubMed : 16925637 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koens, F. (2005). Vertical integration in medical education. Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University, Utrecht.

- Koens, F., et al. (2005). Analysing the concept of context in medical education. Medical Education, 39 (12), 1243–1249. [ PubMed : 16313584 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Krupat, E., et al. (2016). Assessing the effectiveness of case-based collaborative learning via randomized controlled trial. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 723–729. [ PubMed : 26606719 ]

- Lee, A., et al. (2010). Using illness scripts to teach clinical reasoning skills to medical students. Family Medicine, 42 (4), 255–261. [ PubMed : 20373168 ]

- Lockspeiser, T. M., et al. (2008). Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: The value of social and cognitive congruence. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 13 (3), 361–372. [ PubMed : 17124627 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological Science, 24 (8), 1608–1618. [ PubMed : 24986855 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mandin, H., et al. (1995). Developing a “clinical presentation” curriculum at the University of Calgary. Academic Medicine, 70 (3), 186–193. [ PubMed : 7873005 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mandin, H., et al. (1997). Helping students learn to think like experts when solving clinical problems. Academic Medicine, 72 (3), 173–179. [ PubMed : 9075420 ] [ CrossRef ]

- McGlynn, E. A., McDonald, K. M., & Cassel, C. K. (2015). Measurement is essential for improving diagnosis and reducing diagnostic error. JAMA, 314 , 1. [ PubMed : 26571126 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Michaelsen, L., et al. (2008). Team-based learning for health professions education . Sterling: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63 , 81–97. [ PubMed : 13310704 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Norman, G., Young, M., & Brooks, L. (2007). Non-analytical models of clinical reasoning: The role of experience. Medical Education, 41 (12), 1140–1145. [ PubMed : 18004990 ]

- Norman, G., et al. (2014). The etiology of diagnostic errors: A controlled trial of system 1 versus system 2 reasoning. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (2), 277–284. [ PubMed : 24362377 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Norman, G. R., et al. (2017). The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: Cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Academic Medicine, 92 (1), 23–30. [ PubMed : 27782919 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pelaccia, T., et al. (2011). An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: The dual-process theory. Medical Education Online, 16 , 1–9. [ PMC free article : PMC3060310 ] [ PubMed : 21430797 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ploger, D. (1988). Reasoning and the structure of knowledge in biochemistry. Instructional Science, 17 (1988), 57–76. [ CrossRef ]

- Posel, N., Mcgee, J. B., & Fleiszer, D. M. (2014). Twelve tips to support the development of clinical reasoning skills using virtual patient cases. Medical Teacher , 0 (0), 1–6.

- Postma, T. C., & White, J. G. (2015). Developing clinical reasoning in the classroom – Analysis of the 4C/ID-model. European Journal of Dental Education, 19 (2), 74–80. [ PubMed : 24810116 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rencic, J. (2011). Twelve tips for teaching expertise in clinical reasoning. Medical Teacher, 33 (11), 887–892. Available at: http://www .ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pubmed/21711217 . Accessed 1 Mar 2012. [ PubMed : 21711217 ]

- Schmidt, H. (1983). Problem-based learning: Rationale and description. Medical Education, 17 (1), 11–16. [ PubMed : 6823214 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2015). How to improve the teaching of clinical reasoning: A narrative review and a proposal. Medical Education, 49 (10), 961–973. [ PubMed : 26383068 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schmidt, H., et al. (1996). The development of diagnostic competence: Comparison of a problem-based, and integrated and a conventional medical curriculum. Academic Medicine, 71 (6), 658–664. [ PubMed : 9125924 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schuwirth, L. (2002). Can clinical reasoning be taught or can it only be learned? Medical Education, 36 (8), 695–696. [ PubMed : 12191050 ] [ CrossRef ]

- ten Cate, T. J. (1994). Training case-based clinical reasoning in small groups [Dutch]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 138 , 1238–1243. [ PubMed : 8015623 ]

- ten Cate, T. J. (1995). Teaching small groups [Dutch]. In J. Metz, A. Scherpbier, & C. Van der Vleuten (Eds.), Medical education in practice (pp. 45–57). Assen: Van Gorcum.

- ten Cate, T. J., & Schadé, E. (1993). Workshops clinical decision-making. One year experience with small group case-based clinical reasoning education. In J. Metz, A. Scherpbier, & E. Houtkoop (Eds.), Gezond Onderwijs 2 – proceedings of the second national conference on medical education [Dutch] (pp. 215–222). Nijmegen: Universitair Publikatiebureau KUN.

- ten Cate, O., & Durning, S. (2007). Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Medical Teacher, 29 (6), 546–552. [ PubMed : 17978967 ] [ CrossRef ]

- ten Cate, O., Van Loon, M., & Simonia, G. (Eds.). (2014). Modernizing medical education through case-based clinical reasoning (1st ed.). Utrecht: University Medical Center Utrecht. with translations in Georgian, Ukrainian, Azeri and Spanish.

- Topping, K. J. (1996). The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. Higher Education, 32 , 321–345. [ CrossRef ]

- Vandewaetere, M., et al. (2014). 4C/ID in medical education: How to design an educational program based on whole-task learning: AMEE guide no. 93. Medical Teacher, 93 , 1–17. [ PubMed : 25053377 ]

- Williams, R. G., et al. (2011). Tracking development of clinical reasoning ability across five medical schools using a progress test. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86 (9), 1148–1154. [ PubMed : 21785314 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Woods, N. N. (2007). Science is fundamental: The role of biomedical knowledge in clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 41 (12), 1173–1177. [ PubMed : 18045369 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Young, J. Q., et al. (2014). Cognitive load theory: Implications for medical education: AMEE guide no. 86. Medical Teacher, 36 (5), 371–384. [ PubMed : 24593808 ] [ CrossRef ]

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

- Cite this Page ten Cate O. Introduction. 2017 Nov 7. In: ten Cate O, Custers EJFM, Durning SJ, editors. Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2018. Chapter 1. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-64828-6_1

- PDF version of this page (506K)

- PDF version of this title (3.4M)

In this Page

- Summary of the CBCR Method

- Indications for the Effectiveness of the CBCR Method

- CBCR as an Approach to Ignite Curriculum Modernization

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students [ 2018] Review Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students ten Cate O, Custers EJFM, Durning SJ. 2018

- Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students: A brief report of case-based clinical reasoning approach. [J Educ Health Promot. 2024] Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students: A brief report of case-based clinical reasoning approach. Alavi-Moghaddam M, Zeinaddini-Meymand A, Ahmadi S, Shirani A. J Educ Health Promot. 2024; 13:42. Epub 2024 Feb 26.

- Student and educator experiences of maternal-child simulation-based learning: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. [JBI Database System Rev Implem...] Student and educator experiences of maternal-child simulation-based learning: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. MacKinnon K, Marcellus L, Rivers J, Gordon C, Ryan M, Butcher D. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Jan; 13(1):14-26.

- Scripts and medical diagnostic knowledge: theory and applications for clinical reasoning instruction and research. [Acad Med. 2000] Scripts and medical diagnostic knowledge: theory and applications for clinical reasoning instruction and research. Charlin B, Tardif J, Boshuizen HP. Acad Med. 2000 Feb; 75(2):182-90.

- Review Understanding Clinical Reasoning from Multiple Perspectives: A Conceptual and Theoretical Overview. [Principles and Practice of Cas...] Review Understanding Clinical Reasoning from Multiple Perspectives: A Conceptual and Theoretical Overview. ten Cate O, Durning SJ. Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education: A Method for Preclinical Students. 2018

Recent Activity

- Introduction - Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Educatio... Introduction - Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- About Journal

Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research

2349-2996 (Online) 2231-1149 (Print)

Case Study Based on Clinical Reasoning Cycle

Author(s): Deepthy James

Email(s): [email protected]

Address: Deepthy James IKDRC College of Nursing, IKDRC-ITS Premises, Medicity, Asarwa Ahmedabad. *Corresponding Author

Published In: Volume - 12 , Issue - 1 , Year - 2022

ABSTRACT: Introduction: The Clinical Reasoning Cycle is a tool that helps in making decision that enable nurses to select best care options using a process systematically which takes into consideration many factors. The Clinical Reasoning Cycle by Tracy-Levette Jones stimulates critical thinking in order to deliver appropriate management plan for the patient. Aim: The aim of the paper is to adopt and apply Clinical Reasoning Cycle into the nursing care of the patient so that they can easily understand application of Clinical Reasoning Cycle in the clinical areas. Methodology: This document illustrates a case study based on Levette Jones’ Clinical Reasoning Cycle Conclusion: This paper presents a case study in medical-surgical nursing through a discussion of patient-centered, and evidence-based care provisions through a theoretical examination using the Clinical Reasoning Cycle (CRC) of Tracy Levette- Jones (2010). This paper will help the nurses both novice and proficient ones to understand implementation of Clinical Reasoning Cycle in the clinical areas and in writing the case study for the patient.

- Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- Critical thinking

- Nursing care

- Holistic care.

Cite this article: Deepthy James. Case Study Based on Clinical Reasoning Cycle. Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research. 2022; 12(1):82-5. doi: 10.52711/2349-2996.2022.00017 Cite(Electronic): Deepthy James. Case Study Based on Clinical Reasoning Cycle. Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research. 2022; 12(1):82-5. doi: 10.52711/2349-2996.2022.00017 Available on: https://ajner.com/AbstractView.aspx?PID=2022-12-1-17

Recomonded Articles:

Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research (AJNER) is an international, peer-reviewed journal devoted to nursing sciences....... Read more >>>

Quick Links

- Submit Article

- Author's Guidelines

- Paper Template

- Copyright Form

- Cert. of Conflict of Intrest

- Processing Charges

- Indexing Information

Latest Issues

Popular articles, recent articles.

- Background/Objectives:

- technologically

- Nursing"[Mesh])

- "Australia"[Mesh]

- Undergraduate

- SARS-CoV-2.

- Cross-sectional

- Stress Resilience

- Nursing students.

- national-level

- facility-based

- cross-sectional

- Multicollinearity

- Neonatal Mortality

- administration

- schoolchildren

- television/mass

- First aid and safety measures

- school children

- computer assisted Teaching.

- undergraduates

- Research anxiety

- Research methods

- Research usefulness.

- considerations

- transformative

- administrative

- Artificial intelligence

- Clinical Decision Support Systems

- Natural Language Processing

- Workflow Optimization and Resource Management.

- under-nutrition

- non-experimental

- non-probability

- Malnutrition

- School going children.

- pre-experimental

- identification

- Effective Planned Teaching Programme

- Breast Cancer

- Prevention.

- End of life care

- Attitude. Frommelt Attitude Towards Care of Dying (FATCOD).

- evidence-based

- socio-economic

- Pediatric Obesity

- Childhood Obesity

- Nursing Strategies

- Pediatric Wellness.

- Pre-experimental

- Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program

- Organ Donation

- transportation

- Nurse Practitioner

- Role of Nurse.

- physical/biological

- responsibility

- Premenstrual Syndrome

- Nursing officers

- Coping measures

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- PMS and work performance

- PMS and relationship with patients/co-workers.

- differentiation

- Care giver satisfaction

- Nursing care services

- Care givers.

- self-administered

- confidentiality

- hospitalization

- Individuals

- Prevention strategies.

- Cardiovascular

- disease-causing

- cardiovascular

- community-based

- cardio-vascular

- socio-demographic

- Younger Adults

- Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram

- District Early Intervention Centre

- Menstrual Cup

- Nursing Students.

- revolutionized

- AI based technology

- Nursing Education

- Nursing Practice.

The Clinical Reasoning Cycle: A Tool for Building Excellence in Nursing Practice

- Health Services Research Group

- Ageing Well Research Group

- Nursing, Paramedicine and Healthcare Sciences

Research output : Other contribution to conference › Presentation only › peer-review

Fingerprint

- Nursing Practice Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Reasoning Cycle Keyphrases 100%

- Clinical Practice Nursing and Health Professions 66%

- Nurse Nursing and Health Professions 66%

- Case Study Nursing and Health Professions 33%

- Nursing Nursing and Health Professions 33%

- Patient Nursing and Health Professions 33%

- Nursing Care Nursing and Health Professions 33%

T1 - The Clinical Reasoning Cycle: A Tool for Building Excellence in Nursing Practice

AU - Rossiter, Rachel

N2 - Building excellence in the delivery of patient-centred nursing care requires a nursing working force with the capacity for clinical reasoning, critical thinking and reflective practice. This presentation will describe the ‘clinical reasoning cycle’*, the development of this tool and its use in undergraduate and postgraduate nursing education at the University of Newcastle, Australia. The application of the tool in clinical practice will be illustrated using a case study from the clinical practice of a nurse working in a remote area of outback Australia. In conclusion, the potential benefits of the clinical reasoning cycle as a tool for building excellence in nursing practice will be examined. *Levett-Jones, T. (Ed.). (2013). Clinical Reasoning: Learning to think like a nurse. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia The Clinical Reasoning Cycle: A Tool for Building Excellence in Nursing Practice. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270816721_The_Clinical_Reasoning_Cycle_A_Tool_for_Building_Excellence_in_Nursing_Practice [accessed Aug 24, 2017].

AB - Building excellence in the delivery of patient-centred nursing care requires a nursing working force with the capacity for clinical reasoning, critical thinking and reflective practice. This presentation will describe the ‘clinical reasoning cycle’*, the development of this tool and its use in undergraduate and postgraduate nursing education at the University of Newcastle, Australia. The application of the tool in clinical practice will be illustrated using a case study from the clinical practice of a nurse working in a remote area of outback Australia. In conclusion, the potential benefits of the clinical reasoning cycle as a tool for building excellence in nursing practice will be examined. *Levett-Jones, T. (Ed.). (2013). Clinical Reasoning: Learning to think like a nurse. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia The Clinical Reasoning Cycle: A Tool for Building Excellence in Nursing Practice. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270816721_The_Clinical_Reasoning_Cycle_A_Tool_for_Building_Excellence_in_Nursing_Practice [accessed Aug 24, 2017].

M3 - Presentation only

T2 - 2nd Al Gharbia Hospitals International Nursing Conference

Y2 - 17 April 2013

The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing Case Study

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The case study shows how one accident may influence and change human life and how to use of the Clinical Reasoning Cycle and realize that people may need more than just expected nursing care (Levett-Jones, 2013; Salminen, Zary, & Leanderson, 2014). The Clinical Reasoning Cycle consists of several closely connected stages that cannot be ignored and have to be implemented to offer a patient an appropriate level of nursing care in a particular situation. These stages are

- the identification of the facts about a situation,

- the collection and processing of all the necessary information,

- the recognition of nursing problems for consideration,

- the establishment of the goals to be achieved,

- the description of nursing care to be offered with the strategies to rely on

- the explanation of the outcomes (Levett-Jones, 2013).

The current paper is an attempt to analyze the situation of a particular patient, William Peterson (Bill), collect information about this person and the situation he suffers from, identify three nursing problems inherent to the situation, establish the goals for this patient’s nursing care, think about the actions that should be taken (a portion of nursing care), and the outcomes to expect from all interventions.

The situation of the patient is rather clear. Bill is a 70-year-old retired print worker, who now works as a School Crossing Supervisor part-time. Six months ago, he witnessed a fatal accident with one of school children. Now, he suffers from sleeping disorders, terrible flashbacks, and the necessity of drinking about half a bottle to take a rest. He can do nothing to block the memories and follow the same style of life. He does not get the necessary portion of support because he is alone; the wife died several years ago, and they had no children. He becomes socially isolated and thinks that he can hardly restart his communication with friends and army fellows. At the same time, it seems weird that a person, who has survived the army and seen the death of people, faces such psychological problems. Maybe, it is connected to the fact that he does not have his own children and lose the one he tried to help. His psychological problems define his physical conditions considerably. Within a short period of time, Bill’s head is bowed in a quiet tone, and the loss of eye contact is observed. Regarding his medical history with his hypertension that is usually observed in many old people, Bill has a good health and should not take many drugs to keep his organism healthy. Still, one accident that happens three years after his wife’s death because of cancer changes all his current life and requires certain nursing and professional care offered to him.

Taking into consideration the situation and facts from the patient’s life, several nursing issues can be identified and analyzed to understand how to implement appropriate patient-centered care. The first issue is a problematic patient satisfaction (Smith, Turkel, & Wolf, 2012). Bill is a patient that is hard to be satisfied because of the existing psychological trauma, personal regrets, and inability to change the past or try to improve the future. Nurses have to provide patients with the necessary portion of support and understanding to make sure he is satisfied with the conditions of treatment. Still, the case under analysis shows that it can become a serious problem for the medical staff. Another issue is the patient’s family relations (Moos & Schaefer, 2013). Nurses cannot get the patient’s family support because he is alone. He does not have children, and his wife is dead. His friends are not that credible source of information and support for nurses. Family support can become a serious nursing problem that has to be solved or even neglected in a proper way to focus on other important aspects of care. Communication between the patient and nurses is the last nursing issue for consideration that has to be properly developed (Morrissey & Callaghan, 2011). Bill suffers from social isolation he created. He does not want to talk a lot. Nurses should know how to treat such patient and promote communication on the necessary level.

All goals should be directed to choose the best treatment and make Bill feeling free from the burden of the accident. There should be several long-term goals (can be observed after Bill leaves a hospital) and several short-term goals (should be achieved before transferring to a new stage of nursing care) (Burton & Ludwig, 2014). One of the first short-term goals to be set and achieved is the choice of treatment with the help of which Bill can sleep without alcohol and be free from his nightmares and flashbacks. Some psychiatric consultations can help Bill forget about the accident and explain that he could do nothing to change the situation. Still, a properly chosen treatment is not the only goal in this case. A new goal for nurses to set is the development of the connection with a patient and explanations to him about the interventions and the reasons for why they are taken. Finally, one long-term goal in Bill’s care is connected with his ability to cope with the outcomes of the accidents similar to the one he has already survived. Bill himself should be able to achieve the goal and understand that everything can happen to him or to the people around, and his reaction to different situation is his own understanding of the problems and the abilities to cope with them.

In addition to the goals and the abilities of nurses, it is necessary to discuss the process of nursing care. It is wrong to offer as many services as possible at once. Nurses should help to pass one stage of rehabilitation and start talking about the accident without fear or anger. Bill has to be ready to understand the problems of his own and find the solutions. Nurses may perform the role of catalyst to promote the communication between Bill and the doctors and Bill and his friends. The process of rehabilitation focuses on the necessity to destroy the distance between Bill and society. It is possible to remind Bill how interesting and captivating his life was before the accident. Nurses should not rely on the medical aspect of treatment only. Their care should be supportive and personal to help Bill forget his nightmares and personal uncertainties. Finally, the options that are available to him should be mentioned: special drugs help to deal with nightmares, and renewed communication with friends can replace the social hollow Bill suffers from. His friends’ and fellows’ support is another positive addition to nursing care offered. Bill should understand that there is a wonderful world waiting for him outside, and he still has a chance to enjoy it.

To make nursing care chosen more effective, several nursing strategies can be applied to this case. For example, the strategy of hourly rounding (Potter, Perry, Stockert, & Hall, 2013) may be used to improve nursing care. Every hour a nurse visits Bill to ask about his health, discuss some issues, and make sure Bill is ok. As a rule, in the beginning, Bill does not understand the frequency of nurse’s visits. With time, as soon as his condition is improved, Bill starts expecting a nurse enters his room. It will tell about his desire, intentions, and needs. Core measurement is a strategy to rely on as it helps to record everything that happens to the patient and understand the reasons for his behavior and reactions (McDowell, 2006). Nurses are able to follow the changes Bill undergoes and develop those that are favorable for Bill and avoid or decrease the level of impact of those change that are harmful to Bill. Finally, the forcing strategy has to be admitted in this case if the conflicts take place and have to be solved (Huber, 2014). If Bill does not want to accept some nursing help or even drugs explaining it as his unwillingness to believe in the power of treatment or even the necessity to continue living. Forcing can be used to make Bill follow the order and schedules defined by the professional doctors.

In general, it is expected that Bill can survive the accident and forget about the details that bother him days and nights. All the strategies, goals, and activities described in this paper should be properly used to provide Bill with a chance to live a normal life enjoying the possibilities he still has. An optimal use of drugs and communication with the best friends and fellows should also help. The only thing to be done by nurses is the explanation that this life is still worth living, and Bill should not forget about the positive aspects of his own life. Though his wife is not with him, he has a number of friends to spend some time with. It is always possible to find some new activities to get involved in and be happy with any possible results achieved.

Burton, M.A. & Ludwig, L.J.M. (2014). Fundamentals of nursing care: Concepts, connections & skills. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Huber, D. (2014). Leadership and nursing care management. St. Louis, MI: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Levett-Jones, T. (2013). Clinical Reasoning: Learning to think like a nurse. French Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia.

McDowell, I. (2006). Measuring health: A guide to rating scales, and questionnaires . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Moos, R. & Schaefer, J. (2013). Life transitions and crises: A conceptual overview. In R. Moos (Eds.), Coping with life Crises: An integrated approach . New York, NY: Springer.

Morrissey, J. & Callaghan, P. (2011). Communication skills for mental health nurses: An introduction. Berkshire, England: McGraw-Hill Education.

Potter, P. A, Perry, A., G., Stockert, P., & Hall, A. (2013). Fundamentals of nursing . St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Salminen, H., Zary, N., & Leanderson, C. (2014). Virtual patients in primary care: Developing a reusable model that fosters reflective practice and clinical reasoning.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16 (1), 29-39.

Smith, M. C., Turkel, M. C., & Wolf, Z. R. (2012). Caring in nursing classics: An essential resource. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Welcome to Your Nightmares: The Weird Appeal of Horror Movies

- Chicken Run and The Nightmare Before Christmas

- Fuseli's The Nightmare vs. Da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks Paintings

- Nursing: Health Promotion Overview

- Nursing Health Interventions for Health Promotion

- Caring for Community Nursing

- The Nursing Sector: The Different Aspects of Dxplain as a Dss

- Mandatory Overtime in Nursing

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 16). The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-clinical-reasoning-cycle-and-nursing/

"The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing." IvyPanda , 16 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-clinical-reasoning-cycle-and-nursing/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing'. 16 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing." April 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-clinical-reasoning-cycle-and-nursing/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing." April 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-clinical-reasoning-cycle-and-nursing/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Clinical Reasoning Cycle and Nursing." April 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-clinical-reasoning-cycle-and-nursing/.

8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

Last updated on August 19th, 2023

In this article, we will be exploring the clinical reasoning process and its importance in healthcare.

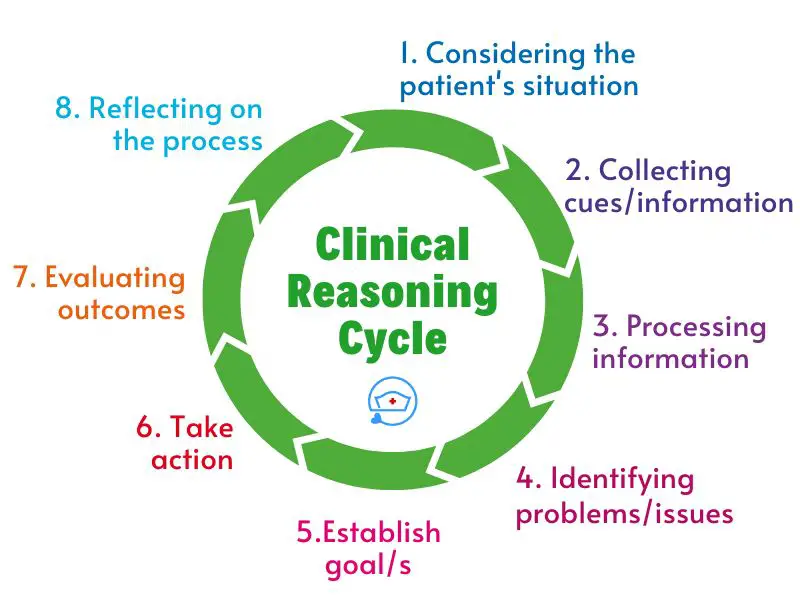

The clinical reasoning cycle, developed by Tracy-Levett Jones, breaks down this process into eight phases that healthcare professionals can follow to make informed decisions for their patients.

These phases include considering facts, collecting information, processing gathered information, identifying the problem, establishing goals, taking action, evaluating the effectiveness of the action, and reflecting on the experience.

By following this cycle, healthcare professionals can enhance their problem-solving and decision-making skills, leading to better patient care.

Related: Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

8 Stages of the Clinical Reasoning Cycle

The eight stages of the Clinical Reasoning Cycle are the following.

- considering the patient’s situation,

- collecting cues/information,

- processing information,

- identifying problems/issues,

- establishing goals,

- taking action,

- evaluating outcomes, and

- reflecting on the process.

These eight phases guide healthcare professionals in providing optimal care to patients.

Each stage is interconnected and builds upon the previous one, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s needs and effective decision-making.

1. Consider the patient’s situation

The first phase of the Clinical Reasoning Cycle involves considering the facts presented by the patient or situation. This is where healthcare professionals receive the initial information and medical status of the patient.

For example , they may be given details about a newborn admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) due to neonatal jaundice.

By carefully considering these facts, healthcare professionals can start to develop an understanding of the patient’s condition and determine the appropriate course of action.

2. Collect cues/ information

In the second phase, healthcare professionals gather additional information to gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s medical history, complaints, treatment plan, and current vital signs.

They may also review the results of any investigations or tests conducted. This information is then analyzed using the healthcare professional’s knowledge of physiology, pharmacology, pathology, culture, and ethics to establish cues and draw conclusions.

The collection of information is a crucial step in the clinical reasoning process, as it helps healthcare professionals to identify any underlying issues or potential challenges.

3. Process information

The third phase involves the processing of the information gathered in the previous step.

It is here that healthcare professionals critically analyze the data on the patient’s current health status in relation to pathophysiological and pharmacological patterns.

They determine which details are relevant and consider potential outcomes for the decisions they may make.

This phase requires healthcare professionals to use their expertise and judgment to identify the key issues that need to be addressed.

4. Identify problems/issues

Based on the processed information, healthcare professionals can identify any problems or issues that the patient may be facing.

This involves recognizing signs and symptoms, understanding the underlying causes, and determining the potential impact on the patient’s health.

5. Establish goals