- Anxiety Guide

- Help & Advice

Social Anxiety

How anxiety can affect speech patterns.

- Anxiety is overwhelming, and it is not surprising that it affects speech.

- We identify at least 5 different examples of how anxiety affects speech.

- Speech typically requires focus and concentration, two things anxiety affects.

- Some types of anxiety are directly related to anxiety while speaking.

- Some public speaking techniques can also help with anxiety-related speech problems, but addressing anxiety itself will still be most important.

Fact Checked

Micah Abraham, BSc

Last updated March 1, 2021

In many ways, anxiety is an overwhelming condition. It overwhelms your senses, it overwhelms your thoughts, and it overwhelms your body. That's why it should come as little surprise to anyone that is suffering from anxiety that it can affect your speech patterns as well.

Anxiety is often apparent in your voice, which is why people can sometimes tell when you're feeling nervous. In this article, we explore some of the ways that anxiety affects speech patterns and what you can do to stop it.

How Anxiety Affects Speech

Different forms of anxiety seem to affect speech in different ways. You should absolutely make sure that you're addressing your anxiety specifically.

Anxiety causes both physical and mental issues that can affect speech. These include:

- Shaky Voice Perhaps the most well-known speech issue is simply a shaky voice. When you're talking, it feels like your voice box is shaking along with the rest of your body (and it is). That can make it sound like it is cracking or vibrating, both of which are a sign to others that you're nervous.

- Quiet Voice Those with anxiety - especially social phobia - often find that they also have a hard time speaking up in public. This type of quietness is very common, and while not technically a speech pattern, it can make your entire voice and the way you speak sound different to others. Although many will think of this in terms of volume, talking down at your feet will also exacerbate the effect.

- Dry Throat/Loss of Voice Some people find that anxiety seems to dry out their throat, or cause them to feel as though they're losing their voice.. One possible reason is that anxiety can make acid reflux symptoms worse, and those with acid reflux do have a tendency to wake up with sore throat and a loss of voice. Anxiety also increases the activity of your nervous system; when your fight or flight response is activated your mouth will naturally produce less saliva as a natural side effect.

- Trouble Putting Thoughts to Words Not all of the speech pattern symptoms of anxiety are physical either. Some of them are mental. Anxiety can make it much harder to for you to think about the words you're going to say, which can cause you to step over yourself, forget words, replace words with incorrect words, and more. Speaking generally has to be natural to be clear, and when you overthink it's not uncommon to find the opposite effect.

- Stuttering Similarly, anxiety can create stuttering. Stuttering itself is a separate disorder that can be made worse by anxiety. But beyond that, those that are overthinking their own sentences and word choices often find they end up stuttering a considerable amount, which in turn can create this feeling of embarrassment.

These are only a few of the issues that anxiety has with speech and speech patterns. There are even those that are bilingual that find that when they have anxiety they mix up the languages. Anxiety can do some unusual things to the way you talk to others, and that means that your speech patterns are occasionally very different than you expect them to be.

Are There Ways to Overcome This Type of Anxiety Issue?

Changes in speech patterns can be embarrassing and very unusual for the person that is suffering from them. It's extremely important for you to address your anxiety if you want these speech issues to go away. Only by controlling your anxiety can you expect your ability to speak with others to improve.

That said, there are a few things that you can do now:

- Start Strong Those with anxiety have a tendency to start speaking quietly and hope that they find it easier to talk later. That rarely works. Ideally, try to start speaking loudly and confidently (even if you're faking it) from the moment you enter a room. That way you don't find yourself muttering as often or as easily.

- Look at Foreheads Some people find that looking others in the eyes causes further anxiety. Try looking at others in the forehead. To them it tends to look the same, and you won't have to deal with the stress of noticing someone's eye contact and gestures.

- Drink Water Keeping your throat hydrated and clear will reduce any unwanted sounds that may make you self-conscious. It's not necessarily a cure for your anxiety, but it will keep you from adding any extra stress that may contribute to further anxiousness.

These are some of the most basic ways to ensure that your anxiety affects your speech patterns less. But until you cure your anxiety, you're still going to overthink and have to consciously control your voice and confidence.

Summary: Anxiety is a distracting condition, making it hard to speak. During periods of intense anxiety, adrenaline can also cause a shaky voice and panic attacks can take away the brain’s energy to talk – leading to slurs and stutters. Identifying the type of speech problem can help, but ultimately it is an anxiety issue that will need to be addressed with a long-term strategy.

Questions? Comments?

Do you have a specific question that this article didn’t answered? Send us a message and we’ll answer it for you!

Where can I go to learn more about Jacobson’s relaxation technique and other similar methods? – Anonymous patient

You can ask your doctor for a referral to a psychologist or other mental health professional who uses relaxation techniques to help patients. Not all psychologists or other mental health professionals are knowledgeable about these techniques, though. Therapists often add their own “twist” to the technqiues. Training varies by the type of technique that they use. Some people also buy CDs and DVDs on progressive muscle relaxation and allow the audio to guide them through the process. – Timothy J. Legg, PhD, CRNP

Read This Next

Anxiety and the Fear of Going Crazy

Fact Checked by Jenna Jarrold, MS, LAC, NCC Updated on September 6, 2022.

One of the most frightening symptoms of anxiety is one that necessarily casued by anxiety itself. Rather, it is caused...

Is Anxiety an Intellectual Disability?

Written by Emma Loker, BSc Psychology Updated on June 7, 2022.

Anxiety and intellectual disability are two phenomena that often coincide. There does appear to be a link between the two,...

How Anxiety Can Create Hallucinations

Fact Checked by Faiq Shaikh, M.D. Updated on March 1, 2021.

Intense anxiety can cause not only fear, but symptoms that create further fear. In many ways, intense anxiety can cause...

Can Panic Attacks Kill You?

Fact Checked by Faiq Shaikh, M.D. Updated on October 10, 2020.

Panic attacks are immensely frightening events. While the anxiety is horrific, it's the physical symptoms that cause people the most...

How Panic Attacks Cause Dizziness

Fact Checked by Daniel Sher, MA, Clin Psychology Updated on October 10, 2020.

Panic attacks are one of the most severe forms of anxiety. They are intense events with dozens of symptoms all...

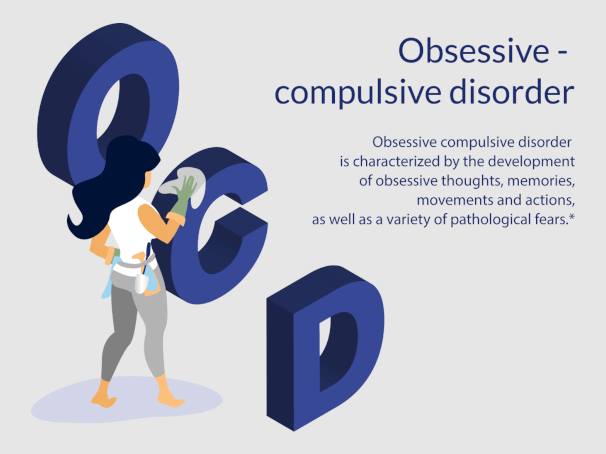

OCD Relationships: What They Are, How to Manage Them

Relationships in which at least one partner has Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) can be difficult, both for the person with...

How to Cure Social Anxiety Outside of Therapy

Fact Checked by Jenna Jarrold, MS, LAC, NCC Updated on October 10, 2020.

Many people experience shyness at some point throughout life. Unfortunately, some people are faced with something much more significant -...

Get advice that’s rooted in medical expertise:

Sign up for our newsletter and get science-backed tips to better manage anxiety and boost your mental health. Nurture yourself with mental health advice that’s rooted in medical expertise.

Your privacy is important to us. Any information you provide to us via this website may be placed by us on servers located in countries outside of the EU. If you do not agree to such placement, do not provide the information.

🍪 Pssst, we have Cookies!

We use Cookies to give you the best online experience. More information can be found here . By continuing you accept the use of Cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

- Anxiety Symptoms

- Make Appointment

- Available Therapists

- Rates and Terms

- Health Insurance?

- Why Therapy?

- Anxiety Therapy

- Jim Folk’s Anxiety Story

- About Anxietycentre.com

- Anxietycentre Recovery Support

- Why Join Recovery Support

- Money Back Guarantee

Difficulty Talking, Speaking, Moving Mouth and Tongue Anxiety Symptoms

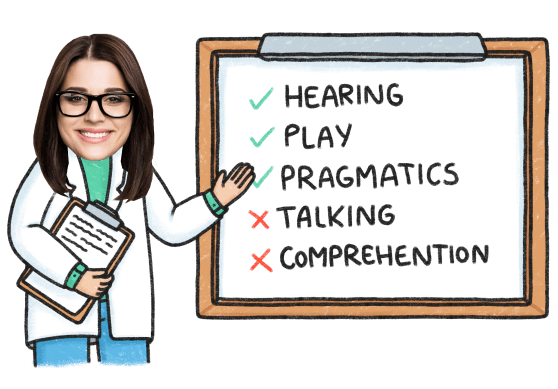

Difficulty speaking and talking, or moving the mouth, tongue, or lips are common symptoms of anxiety disorder , including generalized anxiety disorder , social anxiety disorder , panic disorder , and others.

This article explains the relationship between anxiety and the difficulty talking symptom.

Difficulty speaking, talking, moving mouth, tongue, or lips anxiety symptoms descriptions:

- Having difficulty or unusual awkwardness speaking; pronouncing words, syllables, or vowels.

- Having difficulty moving your mouth, tongue, or lips.

- Suddenly become self-conscious of your problems talking, speaking, moving your mouth, tongue, or lips.

- Uncharacteristically slurring your speech.

- You are uncharacteristically speaking much slower or faster than normal.

- You are uncharacteristically jumbling up words or fumbling over your words when speaking.

- You find that your mouth, tongue, or lips aren’t moving the way they normally would.

- Your mouth, tongue, lips, or facial muscles aren’t responding the way they normally do.

- It can feel as if your face muscles are unusually stiff, which is making talking difficult and forced.

- It can feel as if your face has been anesthetized somewhat, making speaking or moving your mouth, tongue, or lips difficult.

This symptom is often described as “slurred speech.”

This symptom can persistently affect just the mouth, lips, or tongue only, can affect more than one at the same time, can shift from one to another, and can involve all of them over and over again.

Having difficulty speaking can come and go rarely, occur frequently, or persist indefinitely. For example, you might have difficulty speaking once in a while and not that often, have difficulty speaking or moving your mouth, tongue or lips off and on, or have difficulty all the time.

Difficulty speaking can precede, accompany, or follow an escalation of other anxiety sensations and symptoms, or occur by itself. It can also precede, accompany, or follow an episode of nervousness, anxiety, fear, and elevated stress, or occur “out of the blue” and for no apparent reason.

This symptom can range in intensity from slight, to moderate, to severe. It can also come in waves where these mouth and speaking symptoms are strong one moment and ease off the next.

This symptom can change from day to day and from moment to moment.

All of the above combinations and variations are common.

Difficulty speaking or moving your mouth, tongue, or lips can seem more troublesome when in social, professional, or public settings.

To see if anxiety might be playing a role in your anxiety symptoms, rate your level of anxiety using our free one-minute instant results Anxiety Test , Anxiety Disorder Test , or Hyperstimulation Test .

The higher the rating, the more likely it could be contributing to your anxiety symptoms, including having difficulty talking or moving your mouth, tongue, or lips.

---------- Advertisement - Article Continues Below ----------

---------- Advertisement Ends ----------

Why does anxiety cause difficulty speaking, talking, or moving your mouth, tongue, or lips?

Medical Advisory

When this symptom is caused by anxiety, there are many reasons why anxiety can cause this symptom. Here are two of the most common:

1. Stress response

Behaving anxiously activates the stress response , also known as the fight or flight response . The stress response causes body-wide changes that prepare the body for immediate emergency action.[ 1 ][ 2 ] Because of the many changes, stress responses stress the body.

A part of these changes include altering brain function so that our attention is primarily focused on danger detection and reaction, and stimulating the nervous system so that the body is energized and can react quickly.[ 2 ] These changes can affect muscle movements, including the muscles in the mouth, tongue, and lips.

Many people experience difficulty talking and moving their mouth, tongue, or lips when anxious and stressed.

2. Hyperstimulation

Hyperstimulation can keep the stress response changes active even though a stress response hasn’t been activated. Chronic difficulty speaking, talking, and co-ordination problems with the mouth, tongue, and lips are common symptoms of hyperstimulation.

There are many other reasons why anxiety can cause this symptom. We explain these additional reasons under the symptom “Difficulty Speaking” in the Symptoms section (chapter 9) in the Recovery Support area of our website. The Symptoms section lists and explains all of the symptoms associated with anxiety.

How to stop the difficulty talking and moving the mouth, tongue, or lips anxiety symptoms?

When this anxiety symptom is caused by apprehensive behavior and the accompanying stress response changes, calming yourself down will bring an end to the active stress response and its changes. As your body recovers from the active stress response, this anxiety symptom should subside. Keep in mind it can take up to 20 minutes or more for the body to recover from a major stress response. This is normal and shouldn’t be a cause for concern.

When difficulty speaking or moving your mouth, tongue, or lips is caused by chronic stress (hyperstimulation), such as from overly apprehensive behavior, it can take much longer for the body to calm down and recover, and to the point where this anxiety symptom subsides.

Nevertheless, since this symptom is a common symptom of anxiety and stress, it needn't be a cause for concern or worry. This symptom subsides when you’ve eliminated the active stress response or hyperstimulation.

As the body recovers, difficulty speaking and talking, or moving your mouth, tongue, and lips problems disappear and normal functioning returns.

Many of those who struggle with anxiety worry that MS, ALS, a brain tumor, or other neurological condition may be the cause of their symptoms. Checking on the Internet may cause more anxiety, since co-ordination problems are common symptoms of these medical conditions.

But again, these types of symptoms are common for anxiety and stress. Therefore, they needn’t be a cause for concern.

For a more detailed explanation about all anxiety symptoms, why symptoms can persist long after the stress response has ended, common barriers to recovery and symptom elimination, and more recovery strategies and tips, we have many chapters that address this information in the Recovery Support area of our website.

If you are having difficulty containing your worry, you might want to connect with one of our recommended anxiety disorder therapists to help you learn this important skill. Working with an experienced anxiety disorder therapist is the most effective way to overcome what seem like unmanageable worry and problems with anxiety.

Common Anxiety Symptoms

- Heart palpitations

- Dizziness, lightheadedness

- Muscle weakness

- Numbness, tingling

- Weakness, weak limbs

- Asthma and anxiety

- Shooting chest pains

- Trembling, shaking

- Depersonalization

- Chronic pain

- Chronic fatigue

- Muscle tension

- Lump in throat

Additional Resources

- For a comprehensive list of Anxiety Disorders Symptoms Signs, Types, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment.

- Anxiety and panic attacks symptoms can be powerful experiences. Find out what they are and how to stop them.

- How to stop an anxiety attack and panic.

- Anxiety Test

- Anxiety Disorder Test

- Social Anxiety Test

- Generalized Anxiety Test

- Hyperstimulation Test

- Anxiety 101 is a summarized description of anxiety, anxiety disorder, and how to overcome it.

Return to our anxiety disorders signs and symptoms page.

anxietycentre.com: Information, support, and therapy for anxiety disorder and its symptoms, including Difficulty Talking, Speaking, Moving The Mouth Anxiety Symptoms.

1. Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill.

2. Folk, Jim and Folk, Marilyn. “ The Stress Response And Anxiety Symptoms. ” anxietycentre.com, August 2019.

3. Hannibal, Kara E., and Mark D. Bishop. “ Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. ” Advances in Pediatrics., U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2014.

4. Justice, Nicholas J., et al. “ Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Like Induction Elevates β-Amyloid Levels, Which Directly Activates Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Neurons to Exacerbate Stress Responses. ” Journal of Neuroscience, Society for Neuroscience, 11 Feb. 2015.

- All Anxiety Tests

- Panic Attack Test

- Depression Test

- Stress Daily Test

- Stress Test

- Self-Esteem Test

- Passive Test

- Boundaries Test

- Anxiety Personality Test

- Anxiety Symptoms, Causes, Treatment

- Anxiety & Panic Attack Symptoms

- The Stress Response

- Hyperstimulation

- Anxiety Treatment

- Anxiety 101

- Anxiety Recovery 101

- Anxiety FAQ

- Research, News, Stats

- Recovery Stories & Testimonials

- Anxiety Test Quiz

- Daily Stress Test

- Self-Esteem

- Are You Passive Test

- Recovery 101

- Frequent Questions

- Research, News

AnxietyCentre Newsletter

- Name First Last

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Manage Public Speaking Anxiety

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Luis Alvarez / Getty Images

Speech Anxiety and SAD

How to prepare for a speech.

Public speaking anxiety, also known as glossophobia , is one of the most commonly reported social fears.

While some people may feel nervous about giving a speech or presentation if you have social anxiety disorder (SAD) , public speaking anxiety may take over your life.

Public speaking anxiety may also be called speech anxiety or performance anxiety and is a type of social anxiety disorder (SAD). Social anxiety disorder, also sometimes referred to as social phobia, is one of the most common types of mental health conditions.

Public Speaking Anxiety Symptoms

Symptoms of public speaking anxiety are the same as those that occur for social anxiety disorder, but they only happen in the context of speaking in public.

If you live with public speaking anxiety, you may worry weeks or months in advance of a speech or presentation, and you probably have severe physical symptoms of anxiety during a speech, such as:

- Pounding heart

- Quivering voice

- Shortness of breath

- Upset stomach

Causes of Public Speaking Anxiety

These symptoms are a result of the fight or flight response —a rush of adrenaline that prepares you for danger. When there is no real physical threat, it can feel as though you have lost control of your body. This makes it very hard to do well during public speaking and may cause you to avoid situations in which you may have to speak in public.

How Is Public Speaking Anxiety Is Diagnosed

Public speaking anxiety may be diagnosed as SAD if it significantly interferes with your life. This fear of public speaking anxiety can cause problems such as:

- Changing courses at college to avoid a required oral presentation

- Changing jobs or careers

- Turning down promotions because of public speaking obligations

- Failing to give a speech when it would be appropriate (e.g., best man at a wedding)

If you have intense anxiety symptoms while speaking in public and your ability to live your life the way that you would like is affected by it, you may have SAD.

Public Speaking Anxiety Treatment

Fortunately, effective treatments for public speaking anxiety are avaible. Such treatment may involve medication, therapy, or a combination of the two.

Short-term therapy such as systematic desensitization and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be helpful to learn how to manage anxiety symptoms and anxious thoughts that trigger them.

Ask your doctor for a referral to a therapist who can offer this type of therapy; in particular, it will be helpful if the therapist has experience in treating social anxiety and/or public speaking anxiety.

Research has also found that virtual reality (VR) therapy can also be an effective way to treat public speaking anxiety. One analysis found that students treated with VR therapy were able to experience positive benefits in as little as a week with between one and 12 sessions of VR therapy. The research also found that VR sessions were effective while being less invasive than in-person treatment sessions.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

If you live with public speaking anxiety that is causing you significant distress, ask your doctor about medication that can help. Short-term medications known as beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol) can be taken prior to a speech or presentation to block the symptoms of anxiety.

Other medications may also be prescribed for longer-term treatment of SAD, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). When used in conjunction with therapy, you may find the medication helps to reduce your phobia of public speaking.

In addition to traditional treatment, there are several strategies that you can use to cope with speech anxiety and become better at public speaking in general . Public speaking is like any activity—better preparation equals better performance. Being better prepared will boost your confidence and make it easier to concentrate on delivering your message.

Even if you have SAD, with proper treatment and time invested in preparation, you can deliver a successful speech or presentation.

Pre-Performance Planning

Taking some steps to plan before you give a speech can help you better control feelings of anxiety. Before you give a speech or public performance:

- Choose a topic that interests you . If you are able, choose a topic that you are excited about. If you are not able to choose the topic, try using an approach to the topic that you find interesting. For example, you could tell a personal story that relates to the topic as a way to introduce your speech. This will ensure that you are engaged in your topic and motivated to research and prepare. When you present, others will feel your enthusiasm and be interested in what you have to say.

- Become familiar with the venue . Ideally, visit the conference room, classroom, auditorium, or banquet hall where you will be presenting before you give your speech. If possible, try practicing at least once in the environment that you will be speaking in. Being familiar with the venue and knowing where needed audio-visual components are ahead of time will mean one less thing to worry about at the time of your speech.

- Ask for accommodations . Accommodations are changes to your work environment that help you to manage your anxiety. This might mean asking for a podium, having a pitcher of ice water handy, bringing in audiovisual equipment, or even choosing to stay seated if appropriate. If you have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder such as social anxiety disorder (SAD), you may be eligible for these through the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- Don’t script it . Have you ever sat through a speech where someone read from a prepared script word for word? You probably don’t recall much of what was said. Instead, prepare a list of key points on paper or notecards that you can refer to.

- Develop a routine . Put together a routine for managing anxiety on the day of a speech or presentation. This routine should help to put you in the proper frame of mind and allow you to maintain a relaxed state. An example might be exercising or practicing meditation on the morning of a speech.

Practice and Visualization

Even people who are comfortable speaking in public rehearse their speeches many times to get them right. Practicing your speech 10, 20, or even 30 times will give you confidence in your ability to deliver.

If your talk has a time limit, time yourself during practice runs and adjust your content as needed to fit within the time that you have. Lots of practice will help boost your self-confidence .

- Prepare for difficult questions . Before your presentation, try to anticipate hard questions and critical comments that might arise, and prepare responses ahead of time. Deal with a difficult audience member by paying them a compliment or finding something that you can agree on. Say something like, “Thanks for that important question” or “I really appreciate your comment.” Convey that you are open-minded and relaxed. If you don’t know how to answer the question, say you will look into it.

- Get some perspective . During a practice run, speak in front of a mirror or record yourself on a smartphone. Make note of how you appear and identify any nervous habits to avoid. This step is best done after you have received therapy or medication to manage your anxiety.

- Imagine yourself succeeding . Did you know your brain can’t tell the difference between an imagined activity and a real one? That is why elite athletes use visualization to improve athletic performance. As you practice your speech (remember 10, 20, or even 30 times!), imagine yourself wowing the audience with your amazing oratorical skills. Over time, what you imagine will be translated into what you are capable of.

- Learn to accept some anxiety . Even professional performers experience a bit of nervous excitement before a performance—in fact, most believe that a little anxiety actually makes you a better speaker. Learn to accept that you will always be a little anxious about giving a speech, but that it is normal and common to feel this way.

Setting Goals

Instead of trying to just scrape by, make it a personal goal to become an excellent public speaker. With proper treatment and lots of practice, you can become good at speaking in public. You might even end up enjoying it!

Put things into perspective. If you find that public speaking isn’t one of your strengths, remember that it is only one aspect of your life. We all have strengths in different areas. Instead, make it a goal simply to be more comfortable in front of an audience, so that public speaking anxiety doesn’t prevent you from achieving other goals in life.

A Word From Verywell

In the end, preparing well for a speech or presentation gives you confidence that you have done everything possible to succeed. Give yourself the tools and the ability to succeed, and be sure to include strategies for managing anxiety. These public-speaking tips should be used to complement traditional treatment methods for SAD, such as therapy and medication.

Crome E, Baillie A. Mild to severe social fears: Ranking types of feared social situations using item response theory . J Anxiety Disord . 2014;28(5):471-479. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.05.002

Pull CB. Current status of knowledge on public-speaking anxiety . Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(1):32-8. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834e06dc

Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress . Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30(8):1433-40. doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9606-9

Anderson PL, Zimand E, Hodges LF, Rothbaum BO. Cognitive behavioral therapy for public-speaking anxiety using virtual reality for exposure . Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(3):156-8. doi:10.1002/da.20090

Hinojo-Lucena FJ, Aznar-Díaz I, Cáceres-Reche MP, Trujillo-Torres JM, Romero-Rodríguez JM. Virtual reality treatment for public speaking anxiety in students. advancements and results in personalized medicine . J Pers Med . 2020;10(1):14. doi:10.3390/jpm10010014

Steenen SA, van Wijk AJ, van der Heijden GJ, van Westrhenen R, de Lange J, de Jongh A. Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis . J Psychopharmacol (Oxford). 2016;30(2):128-39. doi:10.1177/0269881115612236

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

Understanding and overcoming public speaking anxiety

Most of us might experience what is commonly known as stage fright or speaking anxiety, nervousness and stress experienced around speaking situations in front of audience members. Even for experienced speakers, this can be a normal response to pressurized situations in which we are the focus of attention—such as we might encounter in front of an audience. For some people, though, the fear of public speaking and nervous energy can be much more severe, and can be a sign of an anxiety disorder.

Speaking anxiety is considered by many to be a common but challenging form of social anxiety disorder that can produce serious symptoms, and can possibly impact an individual’s social life, career, and emotional and physical well-being.

In this article, we’ll explore what speaking anxiety is, common symptoms of it, and outline several tips for managing it.

Identifying public speaking anxiety: Definition, causes, and symptoms

According to the American Psychological Association, public speaking anxiety is the “fear of giving a speech or presentation in public because of the expectation of being negatively evaluated or humiliated by others”.

Often associated with a lack of self-confidence, the disorder is generally marked by severe worry and nervousness, in addition to several physical symptoms. The fear can be felt by many, whether they are in the middle of a speech or whether they are planning to speak at a future point. They may also generally fear contact with others in informal settings.

Public speaking anxiety can be a common condition, with an with an estimated prevalence of 15-30% among the general population.

Public speaking anxiety is considered by many to be a form of social anxiety disorder (SAD). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-V) includes a performance specifier that allows a SAD diagnosis to relate specifically to anxiety surrounding public speaking or performing. For some extreme forms of this mental health condition, a medical professional may prescribe medication that can help overcome severe symptoms—although for most people this won’t be necessary.

The symptoms of performance-type social anxiety can include:

- Worry or fear surrounding public speaking opportunities or performing, even in front of friendly faces

- Avoiding situations in which public speaking or performing may be necessary

- Shaky voice, especially when one has to speak in public

- Stomach pain or gastrointestinal discomfort

- Rapid breathing

There are several strategies for addressing the symptoms of this and feeling more confident with your oratory skills, whether you need to use them at work, in formal social settings or simply in front of friends.

The following are several strategies you can employ to address the fear of public speaking and manage your fear when it arises.

While the primary concern for those who experience speaking anxiety might typically be the fear of judgment or embarrassment when speaking publicly, there can be other causes contributing to distress. To figure out how to address this, it can help to understand potential contributing factors—as well as how others may be dealing with it on their own.

First, it can be helpful to determine where the fear came from in the first place. Here are some common sources of public speaking anxiety :

- Negative past experiences with public speaking

- Lack of preparedness

- Low self-esteem (this possible cause can cause feelings of overwhelm if one has to give a speech)

- Inexperience with public speaking

- Unfamiliar subject matter

- Newness of environment

- Fear of rejection (such as from an audience)

Practice deep breathing

Public speaking anxiety might often be accompanied by feelings of stress, and also often affects physical factors such as increased speed of heart rate, tension, and rapid breathing. If you’re dealing with speaking anxiety and want to calm your nerves before a public speaking event, it can be helpful to practice deep breathing exercises. Deep breathing is considered by many to be a widely utilized technique that can help bring your nervous system out of fight-or-flight mode, relax your body, and quiet your mind. Many find it to be one of the most convenient ways to manage symptoms, as many can do it anywhere as needed.

To practice deep breathing prior to speaking, consider using a method called box breathing: breathe in for a four count, hold for a four-count, breathe out for a four count and hold again for a four count. You can repeat this process three to four times, possibly incorporating it with other relaxation techniques. It can also help to be mindful of your breathing as you’re presenting, which can help you steady your voice and calm your nerves.

Practice visualization

When we experience nervousness, we can sometimes focus on negative thoughts and worst-case scenarios, despite the reality of the situation. You can work to avoid this by practicing positive visualization—such as imagining friendly faces in the crowd or you acing the main content of your speech. Positive thinking can be an effective technique for managing performance anxiety.

Visualization is generally regarded as a research-backed method of addressing speaking anxiety that involves imagining the way a successful scenario will progress in detail.

Having a clear idea of how your presentation will go, even in your mind’s eye, can help you gain confidence and make you feel more comfortable with the task at hand.

Understand your subject matter

The fear of speaking in front of others can be related to potential embarrassment that may occur if we make a mistake. To reduce the risk of this possibility, it can help to develop a solid understanding of the material you’ll be presenting or performing and visualize success. For example, if you’re presenting your department’s sales numbers at work, familiarizing yourself with the important points and going over them multiple times can help you better retain the information and feel more comfortable as you give the presentation.

Set yourself up for success

Doing small things to prepare for a speech or performance can make a big difference in helping to alleviate public speaking anxiety. If possible, you may want to familiarize yourself with the location in which you’ll be speaking. It can also help to ensure any technology or other media you’ll be setting up is functional. For example, if you’re using visual aids or a PowerPoint deck, you might make sure it is being projected properly, the computer is charged and that you can easily navigate the slides as you present.

You might even conduct run-throughs of the presentation for your speaking experience. You can practice walking the exact route you’ll take to the podium, setting up any necessary materials, and then presenting the information within the time limit. Knowing how you’ll arrive, what the environment looks like and where exactly you’ll be speaking can set you up for success and help you feel more comfortable in the moment.

Practicing your presentation or performance is thought to be a key factor in reducing your fear of public speaking. You can use your practice time to recognize areas in which you may need improvement and those in which you excel as a speaker.

For example, you might realize that you start rushing through your points instead of taking your time so that your audience can take in the information you’re presenting. Allowing yourself the chance to practice can help you get rid of any filler words that may come out during a presentation and make sure all your points are clear to keep the audience’s interest. Additionally, a practice run can help you to know when it is okay to pause for effect, take some deep breaths, or work effective body language such as points of eye contact into your presentation.

It may also be helpful to practice speaking in smaller social situations, in front of someone you trust, or even a group of several familiar people. Research suggests that practicing in front of an audience of supportive, friendly faces can improve your performance —and that the larger the mock audience is, the better the potential results may be.

To do this, you can go through the process exactly like you would if they were real audience. Once you’re done, you can ask them for feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of your presentation. They may have insights you hadn’t considered and tips you can implement prior to presenting, as well as make you feel confident and relaxed about your material.

Self-care leading up to the moment you’re speaking in public can go a long way in helping you reduce nervousness. Regular physical activity is generally considered to be one proven strategy for reducing social anxiety symptoms . Exercise can help to release stress and boost your mood. If you’re giving a big presentation or speech, it may be helpful to go for a walk or do some mild cardio in the morning.

Additionally, eating a healthy diet and drinking enough water can also help promote a sense of well-being and calm. You may choose to be mindful of your consumption of caffeinated beverages, as caffeine may worsen anxiety.

How online therapy can help

If you experience anxiety when you need to speak in front of other people and want additional support for your communication apprehension, it can help to talk to a licensed mental health professional. According to the American Psychiatric Association, a therapist can work with you to find effective ways to manage public speaking anxiety and feel more confident performing in front of others.

Is Online Therapy Effective?

Studies suggest that online therapy can help individuals who experience anxiety related to presenting or performing in public. In a study of 127 participants with social anxiety disorder, researchers found that online cognitive behavioral therapy was effective in treating the fear of public speaking , with positive outcomes that were sustained for a year post-treatment. The study also noted the increased convenience that can often be experienced by those who use online therapy platforms.

Online therapy is regarded by many as a flexible and comfortable way of connecting with a licensed therapist to work through symptoms of social anxiety disorder or related mental disorders. With online therapy through BetterHelp , you can participate in therapy remotely, which can be helpful if speaking anxiety makes connecting in person less desirable.

BetterHelp works with thousands of mental health professionals—who have a variety of specialties—so you may be able to work with someone who can address your specific concerns about social anxiety.

Therapist reviews

“I had the pleasure of working with Ann for a few months, and she helped me so much with managing my social anxiety. She was always so positive and encouraging and helped me see all the good things about myself, which helped my self-confidence so much. I've been using all the tools and wisdom she gave me and have been able to manage my anxiety better now than ever before. Thank you Ann for helping me feel better!”

Brian has helped me immensely in the 5 months since I joined BetterHelp. I have noticed a change in my attitude, confidence, and communication skills as a result of our sessions. I feel like he is constantly giving me the tools I need to improve my overall well-being and personal contentment.”

If you are experiencing performance-type social anxiety disorder or feel nervous about public speaking, you may consider trying some of the tips detailed above—such as practicing with someone you trust, incorporating deep breathing techniques and visualizing positive thoughts and outcomes.

If you’re considering seeking additional support with social anxiety disorder, online therapy can help. With the right support, you can work through anxiety symptoms, further develop your oratory skills and feel more confidence speaking in a variety of forums.

Studies suggest that online therapy can help individuals who experience nervousness related to presenting or speaking in public. In a study of 127 participants with social anxiety disorder, researchers found that online cognitive behavioral therapy was effective in treating the fear of public speaking , with positive outcomes that were sustained for a year post-treatment. The study also noted the increased convenience that can often be experienced by those who use online therapy platforms.

- How To Manage Travel Anxiety Medically reviewed by Paige Henry , LMSW, J.D.

- The Correlation Between Certain Mental Disorders Medically reviewed by Paige Henry , LMSW, J.D.

- Relationships and Relations

PUBLIC SPEAKING ANXIETY

The fear of public speaking is the most common phobia ahead of death, spiders, or heights. The National Institute of Mental Health reports that public speaking anxiety, or glossophobia, affects about 40%* of the population. The underlying fear is judgment or negative evaluation by others. Public speaking anxiety is considered a social anxiety disorder. * Gallup News Service, Geoffrey Brewer, March 19, 2001.

The fear of public speaking is worse than the fear of death

Evolution psychologists believe there are primordial roots. Our prehistoric ancestors were vulnerable to large animals and harsh elements. Living in a tribe was a basic survival skill. Rejection from the group led to death. Speaking to an audience makes us vulnerable to rejection, much like our ancestors’ fear.

A common fear in public speaking is the brain freeze. The prospect of having an audience’s attention while standing in silence feels like judgment and rejection.

Why the brain freezes

The pre-frontal lobes of our brain sort our memories and is sensitive to anxiety. Dr. Michael DeGeorgia of Case Western University Hospitals, says: “If your brain starts to freeze up, you get more stressed and the stress hormones go even higher. That shuts down the frontal lobe and disconnects it from the rest of the brain. It makes it even harder to retrieve those memories.”

The fight or flight response activates complex bodily changes to protect us. A threat to our safety requires immediate action. We need to respond without debating whether to jump out of the way of on oncoming car while in an intersection. Speaking to a crowd isn’t life threatening. The threat area of the brain can’t distinguish between these threats.

Help for public speaking anxiety

We want our brains to be alert to danger. The worry of having a brain freeze increases our anxiety. Ironically, it increases the likelihood of our mind’s going blank as Dr. DeGeorgia described. We need to recognize that the fear of brain freezing isn’t a life-or-death threat like a car barreling towards us while in a crosswalk.

Change how we think about our mind going blank.

De-catastrophize brain freezes . It might feel horrible if it happens in the moment. The audience will usually forget about it quickly. Most people are focused on themselves. We’ve handled more difficult and challenging situations before. The long-term consequence of this incident is minimal.

Leave it there . Don’t dwell on the negative aspects of the incidents. Focus on what we can learn from it. Worry that it will happen again will become self-fulfilling. Don’t avoid opportunities to create a more positive memory.

Perfectionism won’t help . Setting unachievable standards of delivering an unblemished speech increases anxiety. A perfect speech isn’t possible. We should aim to do our best instead of perfect.

Silence is gold . Get comfortable with silence by practicing it in conversations. What feels like an eternity to us may not feel that way to the audience. Silence is not bad. Let’s practice tolerating the discomfort that comes with elongated pauses.

Avoidance reinforces . Avoiding what frightens us makes it bigger in our mind. We miss out on the opportunity to obtain disconfirming information about the trigger.

Rehearse to increase confidence

Practice but don’t memorize . There’s no disputing that preparation will build confidence. Memorizing speeches will mislead us into thinking there is only one way to deliver an idea. Forgetting a phrase or sentence throw us off and hastens the brain freeze. Memorizing provides a false sense of security.

Practice with written notes. Writing out the speech may help formulate ideas. Practice speaking extemporaneously using bullet points to keep us on track.

Practice the flow of the presentation . Practice focusing on the message that’s delivered instead of the precise words to use. We want to internalize the flow of the speech and remember the key points.

Practice recovering from a brain freeze . Practice recovery strategies by purposely stopping the talk and shifting attention to elsewhere. Then, refer to notes to find where we left off. Look ahead to the next point and decide what we’d like to say next. Finally, we’ll find someone in the audience to start talking to and begin speaking.

Be prepared for the worst . If we know what to do in the worst-case scenario (and practice it), we’ll have confidence in our ability to handle it. We do that by preparing what to say to the audience if our mind goes blank. Visualizing successful recovery of the worst will help us figure out what needs to be done to get back on track.

Learn to relax

Remember to breathe . We can reduce anxiety by breathing differently. Take slow inhalations and even slower exhalations with brief pauses in between. We’ll be more likely to use this technique if practiced in times of low stress.

Speak slowly . It’s natural to speed up our speech when we are anxious. Practice slowing speech while rehearsing. When we talk quickly, our brain sees it is a threat. Speaking slowly and calmly gives the opposite message to our brain.

Make eye contact with the audience . Our nerves might tell us to avoid eye contact. Making deliberate eye contact with a friendly face will build confidence and slow our speaking.

Join a group . Practice builds confident in public speaking. Groups like Toastmasters International provide peer support to hone our public speaking skill. Repeated exposure allows us to develop new beliefs about our fear and ability to speak in public.

The fear of our mind going blank during a speech is common. Job advancement or college degree completion may be hampered by not addressing this fear.

How to Get Help for Social Anxiety

The National Social Anxiety Center (NSAC) is an association of independent Regional Clinics and Associates throughout the United States with certified cognitive-behavioral therapists (CBT) specializing in social anxiety and other anxiety-related problems.

Find an NSAC Regional Clinic or Associate which is licensed to help people in the state where you are located.

Places where nsac regional clinics and associates are based.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Mini review article, speech anxiety in the communication classroom during the covid-19 pandemic: supporting student success.

- The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, United States

A wealth of literature clearly supports the presence of speech anxiety in the communication classroom, especially in those classes with a focus on public speaking and/or presentations. Over the years, much work has been done on intentional approaches to empowering students to effectively manage their speech anxiety in face-to-face, hybrid, and online communication courses. These research-based findings have led to best practices and strong pedagogical approaches that create a supportive classroom culture and foster engaged learning. Then COVID-19 appeared, and things changed. In an effort to keep campuses safe and save the spring semester, everyone jumped online. Many instructors and students were experiencing online education for the first time and, understandably, anxiety exploded. Between the uncertainty of a global pandemic, the unchartered territory of a midterm pivot to fully online education, and the unknown effects of the situation on our educational system, our stress levels grew. Public speaking and presentations took on new meaning with Zoom sessions and webcams and our speech anxiety, undoubtedly, grew, as well. Reflecting upon the scholarship of the past with an appreciation of our present situation and looking toward the future, we will curate a list of best practices to prepare students to effectively manage their speech anxiety with agency, ability, and confidence.

Introduction

It is impossible for Isabella to catch her breath. Her pulse is racing, she is flushed, and her thoughts are a jumbled mess. She is desperately trying to remember her plan, slow her breathing and visualize success but it is impossible to do anything but panic. She is convinced she will embarrass herself and fail her assignment. Why had she postponed taking her public speaking class? Yes, it would have been bad in a “normal” term but now, amidst the coronavirus pandemic, she had to take the class online. Though it seems unimaginable that the class could be more terrifying, add Zoom sessions, internet connection issues, and little engagement with her teacher or classmate and Isabella’s out of control speech anxiety is completely understandable . If you have been in a college classroom, most likely, you have had to deliver a presentation, lead a discussion, or share a poster presentation. If so, you know what speech anxiety is like. Most of us have experienced the racing heart rate, difficulty concentrating and sensory overload characteristic of speech anxiety ( Dwyer, 2012 ). For some of us, like Isabella, the speech anxiety is almost debilitating. Even if you are one of the rare people who does not experience speech anxiety, you probably witnessed your classmates struggle with the stress, worry and insecurity caused by speech anxiety. It was prevalent before the arrival of COVID-19 and now with the stressors associated with the pandemic, virtual learning, and social distancing it will most likely increase. Fortunately, we have the research, resources, and resolve to intentionally craft classroom culture that will support communication success.

Meeting the Challenges of COVID-19

In the early spring of 2020, the coronavirus pandemic arrived in the United States, and required an unprecedented mid-term pivot. Classes rapidly moved from face-to-face instruction to online platforms in days. Teachers who had never taught online were learning while teaching, managing that additional workload while trying to stay connected with students who were worried and often overwhelmed. In addition to the public and personal health concerns of the virus, there were worries about online learning, the economy, and mental health. The bright spot was that in so many classes, the connections had been established before the pivot and so teachers and students were able to engage with familiar people in new ways. It was not an ideal situation but there was a sense that we were all in this together.

The fall of 2020 found many institutions of higher education and their faculty, staff, and students once again engaged in online instruction and it looks like it will be that way for the near future. We were faced with the new challenge of creating supportive and engaging class spaces completely virtual (in many cases) or in hybrid form with some classes combining online coursework with limited in-person instruction. Experience taught us that our students were speech anxious and that we needed to intentionally design safe and engaging spaces to support their success even before the arrival of COVID-19. Our challenge was to adopt a new skillset and look to the online learning community for resources, suggestions, and best practices.

Pandemic Pedagogy

Articles and emerging research on the response to the pandemic at the institutional, classroom, and individual level provide a glimpse into how we can craft virtual classroom spaces that support learning while meeting the needs created by COVID-19. Common themes for solid pandemic pedagogy include a focus on student mental health and well-being ( Gigliotti, 2020 ; Burke, 2021 ), an appreciation of technology challenges and access issues ( Turner et al., 2020 ; Burke, 2021 ; Singh, 2021 ), and a commitment to engaged teaching and learning ( Turner et al., 2020 ; Jenkins, 2021 ; Lederman, 2021 ). The fundamentals of good teaching are the same regardless of the modality and the foundational pedagogical practices are also similar, yet the primary difference is that solid online education has been designed for a virtual modality, not adapted to fit it (Kelly and Westerman, 2016 ). How can we craft safe and supportive online and virtual spaces for students to find, develop, and then actively share? A good place to start is with wayfinding which can “reinforce ways of knowing and problem solving,” ( Petroski and Rogers, 2020 , p. 125). Wayfinding supports efficacy and empowerment while meeting the challenges of pandemic pedagogy and can be incorporated into online communication classes to reduce speech anxiety and build classroom culture.

Speech Anxiety

The fear of public speaking, known as glossophobia, is a common and real form of anxiety ( Sawchuk, 2017 ) affecting as much as 75% of the population ( Black, 2019 ). In the scholarly literature, it is usually referred to as communication anxiety, communication apprehension, or communication avoidance ( Richmond and McCroskey, 1998 ). In more popular sources, such as Harvard Management Communication Letter, it has been called stage fright ( Daly and Engleberg, 1999 ) and speech anxiety ( Getting over speech anxiety, 2001 ). In this work, we will refer to it as speech anxiety as that term most closely targets the experience we are exploring.

Regardless of the label, it is our innate survival mode of flight, fight, or flee in the face of imminent (real or perceived) danger ( Thomas, 1997 ; Dwyer, 1998 ). Our mind feels a threat from a public speaking situation and our body responds accordingly. Common symptoms can include increased heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing; excessive perspiration, skin flush or blush; shaky voice; trembling hands and feet; or dry mouth and nausea ( Thomas, 1997 ; Dwyer, 1998 ; Black, 2019 ).

There are many tips and techniques that can help those with speech anxiety manage their symptoms and communicate effectively across a variety of modalities. Some common strategies include relaxation, visualization, cognitive restructuring, and skills training ( Motley, 1997 ; Thomas, 1997 ; Richmond and McCroskey, 1998 ; Dwyer, 2012 ).

(1) Typical relaxation tips can include mindfulness, deep breathing, yoga, listening to music, and taking long walks,

(2) Visualization involves inviting the speaker to imagine positive outcomes like connecting with their audience, making an impact, and sharing their presentation effectively ( Thomas, 1997 ; Dwyer, 1998 ). It replaces much of the negative self-talk that tends to occur before a speech opportunity and increases our anxiety.

(3) Cognitive restructuring is a more advanced technique with the goal “to help you modify or change your thinking in order to change your nervous feelings,” ( Dwyer, 2012 , p. 93). In essence, it involves replacing negative expectations and anxious feelings about public speaking opportunities with more positive and self-affirming statements and outlooks.

(4) Skills training is what we do in our classrooms and during professional workshops and trainings. It can include exploring speech anxiety and discussing how common it is as well as ways to effectively manage it ( Dwyer, 2012 ). It also involves analysis of the component parts, such as delivery and content ( Motley, 1997 ) practicing and delivering speeches in low stakes assignments, collaborating with classmates, and engaging in active listening ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 ).

Ideally, solid skills training introduces the other techniques and encourages individuals to experiment and discover what works best for them. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to speech anxiety.

Classroom Culture

According to the Point to Point Education website, “Classroom culture involves creating an environment where students feel safe and free to be involved. It’s a space where everyone should feel accepted and included in everything. Students should be comfortable with sharing how they feel, and teachers should be willing to take it in to help improve learning,” ( Point to Point Education, 2018 , paragraph 2). Regardless of subject matter, class size, format, or modality, all college classes need a supportive and engaging climate to succeed ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 ). Yet having a classroom culture that is supportive and conducive to lowering anxiety is especially critical in public speaking courses ( Stewart and Tassie, 2011 ; Hunter et al., 2014 ). Faculty are expected to engage and connect with students and do so in intentional, innovative, and impactful ways. These can be simple practices, like getting to know students quickly and referring to them by their preferred name, such as a middle name or shortened first name ( Dannels, 2015 ), or more elaborate practices like incorporating active learning activities and GIFTS (Great Ideas for Teaching Students) throughout the curriculum ( Seiter et al., 2018 ). We want to create a positive and empowering classroom climate that offers equitable opportunities for all students to succeed. As educators, we can infuse empathy, spontaneity, and equality into our pedagogy while being mindful of different learning styles and committed to supporting diversity and inclusion ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 ; Dannels, 2015 ). Furthermore, our communication classrooms need to be intentional spaces where challenges, such as anxiety disorders, mental health issues, learning disabilities and processing issues, are supported and accommodated ( Simonds and Hooker, 2018 ).

Ideally, we want to cultivate a classroom culture of inquiry, success, and connection. We also want to foster immediacy, the “verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors that enhance physical and psychological closeness,” ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 , p. 32). Multiple studies support that teachers who demonstrate immediate behaviors are regarded as more positive, receptive to students, and friendly ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 ). As teachers and scholars, we want to make a positive impact. Dannels (2015) writes that “teaching is heart work,” (p. 197) and she is right. It demands an investment of our authentic selves to craft a climate of safety and support where comfort zones are expanded, challenges are met, and goals are reached.

Educators need to be mindful of and responsive to the challenges COVID-19 presents to the health and well-being of our students, colleagues, and communities. In May of 2020, the National Communication Association (NCA) devoted an entire issue of its magazine to “Communication and Mental Health on campus 2020,” ( Communication and mental health on campus, 2020 ) highlighting the importance of this issue in our communication education spaces. Suggestions included learning more about mental health issues, engaging in thoughtful conversations, listening intentionally and actively, promoting well-being, and serving as an advocate and ally ( Communication and mental health on campus, 2020 ).

Scholarship about instructional communication, computer mediated communication and online education ( Kelly and Fall, 2011 ) offers valuable insights into effective practices and adaptations as we intentionally craft engaging and supportive spaces, so our students feel empowered to use their voice and share their story, even those with high speech anxiety. Instructional communication scholars focus on the effective communication skills and strategies that promote and support student success and an engaged learning environment ( Simonds and Cooper, 2011 ).

General strategies to teach effectively during the pandemic can be helpful and easily adaptable to our public speaking classrooms. Being flexible with assignments, deadlines and attendance can support student success and well-being as can creativity, engagement activities, and appealing to different learning styles and strengths ( Mahmood, 2020 ; Singh, 2021 ). It seems everyone is presenting virtually now, not just in our communication classrooms and that can take some getting used to. Educators can model and promote effective communication by being conversational and engaging and empathizing with the many challenges everyone is facing ( Gersham, 2020 ; Gigliotti, 2020 ; Jenkins, 2021 ; Singh, 2021 ).

This is also a great opportunity to innovate and cultivate a new classroom climate looking at communication in a new way for a new, digital age. During this time of change we can harness opportunities and encourage our students to develop the skillsets needed to communicate effectively during COVID-19 and after. Preparing them as digital communicators with a focus on transferable and applicable skills would help them in other classes and the job market ( Ward, 2016 ). Innovations to our courses, assessment tools, and learning outcomes can all happen now, too ( Ward, 2016 ). This is the time to innovate our course experiences across all modalities, reinvent what public speaking means in the modern, digital age and intentionally craft learning spaces for all students in which speech anxiety is intentionally addressed and effectively managed.

Best Practices

(1) Be flexible, as a matter of practice not exception. Speech anxiety was experienced by most students to some degree and was debilitating for some pre-pandemic and adds another layer of stress for students who are capable and resilient yet dealing with a lot. Podcasts are a common communication medium and may ease the anxiety of some students while highlighting the importance of word choice, rate, and tone. They also involve less bandwidth and technology and may be easier for many students to create.

(2) Reframe communication as a skill of the many, not just the few. Highly speech anxious students tend to believe they are the only ones who have a fear of presenting and only certain, confident individuals can present well. Neither of these are true. If we reframe presentations as conversations, demystify speech anxiety by discussing how common it is, and empower our students with the knowledge that they can effectively communicate, we can reduce anxiety, build confidence, and develop important skills that transcend disciplines and promote self-efficacy.

(3) Build a community of support and success. When we see our students as individuals, celebrate connection and collaboration, and actively engage to learn and grow, we co-create an impactful and empowering space that supports success not by being rigid and demanding but by being innovative, intentional, and inspiring.

Author Contributions

I am thrilled to contribute to this project and explore ways we can empower our students to effectively manage their speech anxiety and share their stories.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Black, R. (2019). Glossophobia (Fear of public speaking): are you glossophobic? Psycom. Available at: https://www.psycom.net/glossophobia-fear-of-public-speaking (Accessed December 14, 2020).

Google Scholar

Burke, L. (2021). Inside higher . Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/01/22/survey-outlines-student-concerns-10-months-pandemic (Accessed January 22, 2021).

Communication and mental health on campus [Special focus] (2020). Spectra. NCA 56 (2), 6–27.

Daly, J., and Engleberg, I. (1999). Coping with stagefright . 2nd Edn. Canada, United States: Harvard Management Communication .

Dannels, D. P. (2015). 8 Essential questions teachers ask: a guidebook for communication with students .New York, NY: Oxford University Press .

Dwyer, K. K. (1998). Conquer your speechfright . San Diego, United States: Harcourt, Brace .

Dwyer, K. K. (2012). iConquer speech anxiety . Omaha, NE: KLD publications .

Gersham, S. (2020). Yes, virtual presenting is weird. Harvard Business Review . Available at: https://hbr.org/2020/11/yes-virtual-presenting-is-weird?utm_medium=em (Accessed November 4, 2020).

Getting over speech anxiety (2001). Harvard Management Communication Letter , 14 (2), 1–4.

Gigliotti, R. A. (2020). Sudden shifts to fully online: perceptions of campus preparedness and Implications for leading through disruption. J. Literacy Technology 21 (2), 18–36.

Hunter, K. M., Westwick, J. N., and Haleta, L. L. (2014). Assessing success: the impacts of a Fundamentals of speech course on decreasing public speaking anxiety. Commun. Educ. 63 (2), 124–135. doi:10.1080/03634523.2013.875213

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jenkins, R. (2021). What I learned in the pandemic. The Chronicle of Higher Education . Available at: https://www-chronicle-com.article/what-i-learned-in-the-pandemic .

Kelly, S., and Fall, L. T. (2011). An investigation of computer-mediated instructional immediacy. In online education: a comparison of graduate and undergraduate students’ motivation to learn. J. Advertising Education 15, 44–51. doi:10.1177/109804821101500107

Kelly, S., and Westerman, D. K. (2016). New technologies and distributed learning systems. Commun. Learn. 16, 455. doi:10.1515/9781501502446-019

Lederman, D. (2021). Professors assess fall instruction and the impact on students . Insider Higher Ed . Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2021/01/26/survey-finds-professors-worried-about-dropouts-particularly .

Mahmood, S. (2020). Instructional strategies for online teaching in COVID‐19 pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerging Tech. 3, 199–203. doi:10.1002/hbe2.218

Motley, M. T. (1997). Overcoming your fear of public speaking: a proven method . Boston,United States: Houghton Mifflin , 140.

Petroski, D. J., and Rogers, D. (2020.). An examination of student responses to a suddenly online Learning environment: what we can learn from gameful instructional approaches. J. Literacy Technology 21 (2), 102–129.

Point to Point Education (2018). Positive classroom culture strategies . Available at: https://www.pointtopointeducation.com/blog/positive-classroom-culture-strategies/ (Accessed January 21, 2021).

Richmond, V. R., and McCroskey, J. C. (1998). Communication apprehension, avoidance, and effectiveness . 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon .

Sawchuk, C. N. (2017). Fear of public speaking: how can I overcome it? Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/specific-phobias/expert-answers/fear-of- public-speaking/faq-20058416 (Accessed May 17, 2017).

Seiter, J. S., Peeples, J., and Sanders, M. L. (2018). Communication in the classroom: a collection of G.I.F.T.S. Bedford/St. Martin’s .

Simonds, C. J., and Cooper, P. J. (2011). Communication for the classroom teacher 9th ed. Boston, MA, United States: Allyn & Bacon .

Simonds, C. J., and Hooker, J. F. (2018). Creating a culture of accommodation in the publicspeaking course. Commun. Education , 67 (3), 393–399. doi:10.1080/03634523.2018.1465190

Singh, C. (2021). Why flipped classes often flop. Inside Higher . Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/01/20/lessons-learned-during-pandemic-about-how-teach-flipped-classes-most-effectively (Accessed January 20, 2021).

Stewart, F., and Tassie, K. E. (2011). Changing the atmos’ fear’in the public speaking classroom. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1 (7), 9–13.

Thomas, L. T. (1997). Public speaking anxiety: how to face the fear . Ohio, United States: Wadsworth .

Turner, J. W., Wange, F., and Reinsch, N. L. (2020). How to be socially present when the class Becomes “suddenly distant. J. Literacy Technology 21 (2), 76–101.

Ward, S. (2016). It’s not the same thing: considering a path forward for teaching public Speaking online. Rev. Commun. 16 (2–3), 222–235. doi:10.1080/15358593.2016.1187458/2016

Keywords: speech anxiety, public speaking anxiety, instructional communication, communication pedagogy, Best Practices

Citation: Prentiss S (2021) Speech Anxiety in the Communication Classroom During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Supporting Student Success. Front. Commun. 6:642109. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.642109

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 08 February 2021; Published: 12 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Prentiss. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suzy Prentiss, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Cultural Changes in Instructional Practices Due to Covid-19

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Fear of public speaking: how can i overcome it, how can i overcome my fear of public speaking.

Fear of public speaking is a common form of anxiety. It can range from slight nervousness to paralyzing fear and panic. Many people with this fear avoid public speaking situations altogether, or they suffer through them with shaking hands and a quavering voice. But with preparation and persistence, you can overcome your fear.

These steps may help:

- Know your topic. The better you understand what you're talking about — and the more you care about the topic — the less likely you'll make a mistake or get off track. And if you do get lost, you'll be able to recover quickly. Take some time to consider what questions the audience may ask and have your responses ready.

- Get organized. Ahead of time, carefully plan out the information you want to present, including any props, audio or visual aids. The more organized you are, the less nervous you'll be. Use an outline on a small card to stay on track. If possible, visit the place where you'll be speaking and review available equipment before your presentation.

- Practice, and then practice some more. Practice your complete presentation several times. Do it for some people you're comfortable with and ask for feedback. It may also be helpful to practice with a few people with whom you're less familiar. Consider making a video of your presentation so you can watch it and see opportunities for improvement.

- Challenge specific worries. When you're afraid of something, you may overestimate the likelihood of bad things happening. List your specific worries. Then directly challenge them by identifying probable and alternative outcomes and any objective evidence that supports each worry or the likelihood that your feared outcomes will happen.

- Visualize your success. Imagine that your presentation will go well. Positive thoughts can help decrease some of your negativity about your social performance and relieve some anxiety.

- Do some deep breathing. This can be very calming. Take two or more deep, slow breaths before you get up to the podium and during your speech.

- Focus on your material, not on your audience. People mainly pay attention to new information — not how it's presented. They may not notice your nervousness. If audience members do notice that you're nervous, they may root for you and want your presentation to be a success.

- Don't fear a moment of silence. If you lose track of what you're saying or start to feel nervous and your mind goes blank, it may seem like you've been silent for an eternity. In reality, it's probably only a few seconds. Even if it's longer, it's likely your audience won't mind a pause to consider what you've been saying. Just take a few slow, deep breaths.

- Recognize your success. After your speech or presentation, give yourself a pat on the back. It may not have been perfect, but chances are you're far more critical of yourself than your audience is. See if any of your specific worries actually occurred. Everyone makes mistakes. Look at any mistakes you made as an opportunity to improve your skills.

- Get support. Join a group that offers support for people who have difficulty with public speaking. One effective resource is Toastmasters, a nonprofit organization with local chapters that focuses on training people in speaking and leadership skills.

If you can't overcome your fear with practice alone, consider seeking professional help. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a skills-based approach that can be a successful treatment for reducing fear of public speaking.

As another option, your doctor may prescribe a calming medication that you take before public speaking. If your doctor prescribes a medication, try it before your speaking engagement to see how it affects you.

Nervousness or anxiety in certain situations is normal, and public speaking is no exception. Known as performance anxiety, other examples include stage fright, test anxiety and writer's block. But people with severe performance anxiety that includes significant anxiety in other social situations may have social anxiety disorder (also called social phobia). Social anxiety disorder may require cognitive behavioral therapy, medications or a combination of the two.

Craig N. Sawchuk, Ph.D., L.P.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Social anxiety disorder (social phobia). In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- 90 tips from Toastmasters. Toastmasters International. https://www.toastmasters.org/About/90th-Anniversary/90-Tips. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Stein MB, et al. Approach to treating social anxiety disorder in adults. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- How to keep fear of public speaking at bay. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/monitor/2017/02/tips-sidebar.aspx. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Jackson B, et al. Re-thinking anxiety: Using inoculation messages to reduce and reinterpret public speaking fears. PLOS One. 2017;12:e0169972.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. April 24, 2017.

Products and Services