- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Global migration: causes and consequences.

- Benjamin Helms Benjamin Helms Department of Politics, University of Virginia

- and David Leblang David Leblang Department of Politics, Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, University of Virginia

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.631

- Published online: 25 February 2019

International migration is a multifaceted process with distinct stages and decision points. An initial decision to leave one’s country of birth may be made by the individual or the family unit, and this decision may reflect a desire to reconnect with friends and family who have already moved abroad, a need to diversify the family’s access to financial capital, a demand to increase wages, or a belief that conditions abroad will provide social and/or political benefits not available in the homeland. Once the individual has decided to move abroad, the next decision is the choice of destination. Standard explanations of destination choice have focused on the physical costs associated with moving—moving shorter distances is often less expensive than moving to a destination farther away; these explanations have recently been modified to include other social, political, familial, and cultural dimensions as part of the transaction cost associated with migrating. Arrival in a host country does not mean that an émigré’s relationship with their homeland is over. Migrant networks are an engine of global economic integration—expatriates help expand trade and investment flows, they transmit skills and knowledge back to their homelands, and they remit financial and human capital. Aware of the value of their external populations, home countries have developed a range of policies that enable them to “harness” their diasporas.

- immigration

- international political economy

- factor flows

- gravity models

Introduction

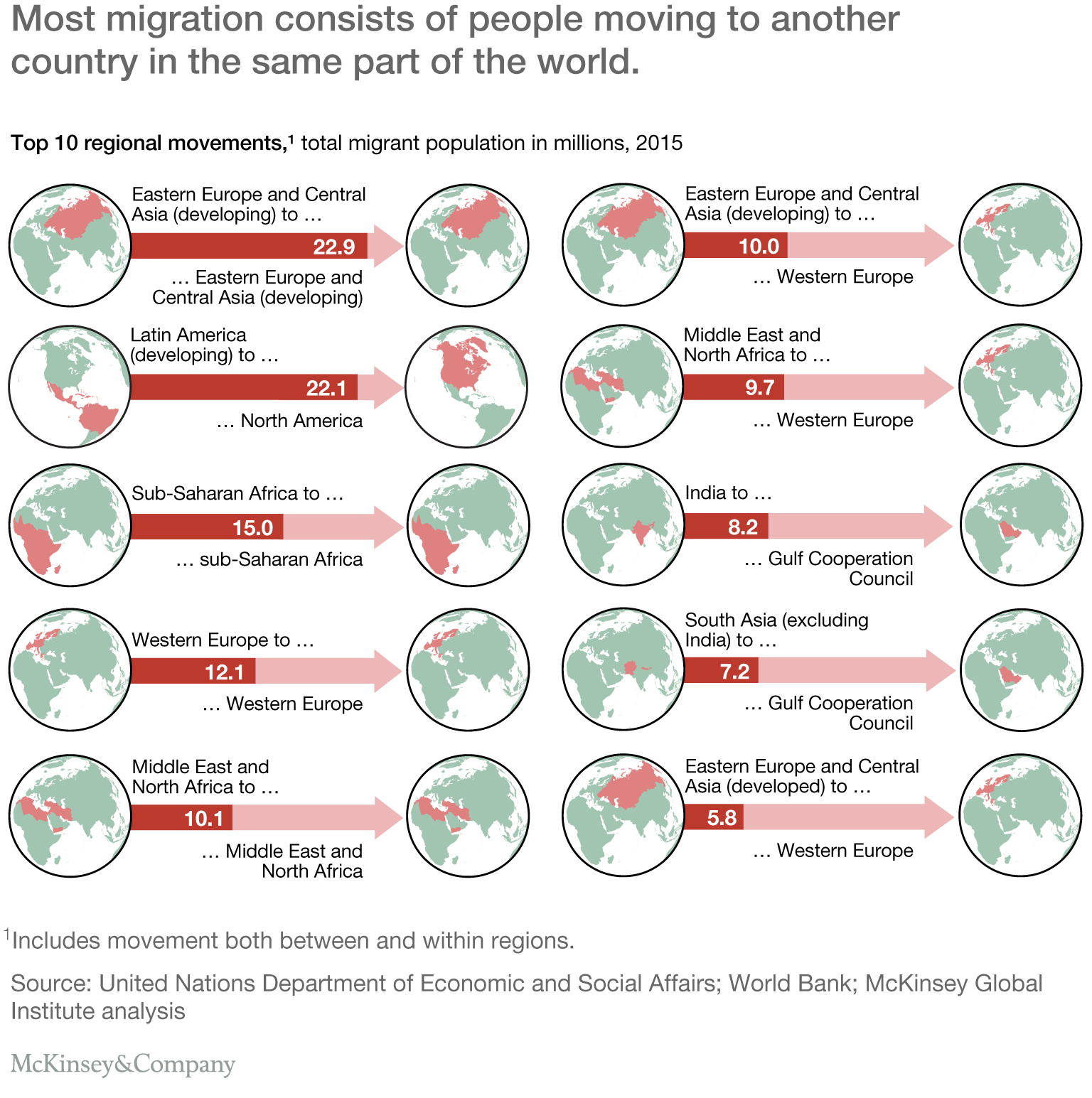

The steady growth of international labor migration is an important, yet underappreciated, aspect of globalization. 1 In 1970 , just 78 million people, or about 2.1% of the global population, lived outside their country of birth. By 1990 , that number had nearly doubled to more than 150 million people, or about 2.8% of the global population (United Nations Population Division, 2012 ). Despite the growth of populist political parties and restrictionist movements in key destination countries, the growth in global migration shows no signs of slowing down, with nearly 250 million people living outside their country of birth as of 2015 . While 34% of all global migrants live in industrialized countries (with the United States and Germany leading the way), 38% of all global migration occurs between developing countries (World Bank, 2016 ).

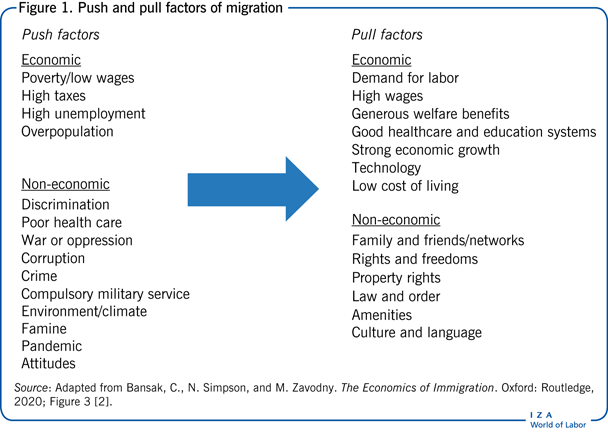

Identifying the causes and consequences of international labor migration is essential to our broader understanding of globalization. Scholars across diverse academic fields, including economics, political science, sociology, law, and demography, have attempted to explain why individuals voluntarily leave their homelands. The dominant thread in the labor migration literature is influenced by microeconomics, which posits that individuals contemplating migration are rational, utility-maximizing actors who carefully weigh the potential costs and benefits of leaving their country of origin (e.g., Borjas, 1989 ; Portes & Böröcz, 1989 ; Grogger & Hanson, 2011 ). The act of migration, from this perspective, is typically conceptualized as an investment from which a migrant expects to receive some benefit, whether it be in the form of increased income, political freedom, or enhanced social ties (Schultz, 1961 ; Sjaastad, 1962 ; Collier & Hoeffler, 2014 ).

In this article we go beyond the treatment of migration as a single decision and conceive of it as a multifaceted process with distinct stages and decision points. We identify factors that are relevant at different stages in the migration process and highlight how and when certain factors interact with others during the migration process. Economic factors such as the wage differential between origin and destination countries, for example, may be the driving factor behind someone’s initial decision to migrate (Borjas, 1989 ). But when choosing a specific destination, economic factors may be conditioned by political or social conditions in that destination (Fitzgerald, Leblang, & Teets, 2014 ). Each stage or decision point has distinguishing features that are important in determining how (potential) migrants respond to the driving forces identified by scholars.

This is certainly not a theoretical innovation; migration has long been conceived of as a multi-step process, and scholars often identify the stage or decision point to which their argument best applies. However, most interdisciplinary syntheses of the literature on international labor migration do not provide a systematic treatment of this defining feature, instead organizing theoretical and empirical contributions by field of study, unit or level of analysis, or theoretical tradition (e.g., Portes & Böröcz, 1989 ; Massey et al., 1993 ; European Asylum Support Office, 2016 ). Such approaches are undoubtedly valuable in their own right. Our decision to organize this discussion by stage allows us to understand this as a process, rather than as a set of discrete events. As a result, we conceptualize international labor migration as three stages or decision points: (a) the decision to migrate or to remain at home, (b) the choice of destination, and (c) the manner by which expatriates re-engage—or choose not to re-engage—with their country of origin once abroad. We also use these decision points to highlight a number of potential new directions for future research in this still-evolving field.

Figure 1. Global migration intentions by educational attainment, 2008–2017.

Should I Stay or Should I Go, Now?

The massive growth in international labor migration in the age of globalization is remarkable, but the fact remains that over 95% of the world’s population never leave their country of origin (United Nations Population Division, 2012 ). Figure 1 shows the percentage of people who expressed an intention to move abroad between 2008 and 2017 by educational attainment, according to data from the Gallup World Poll. Over this time period, it appears that those who were highly educated expressed intent to migrate in greater numbers than those who had less than a college education, although these two groups have converged in recent years. What is most striking, however, is that a vast majority of people, regardless of educational attainment, expressed no desire to move abroad. Even though absolute flows of migrants have grown at a near-exponential rate, relative to their non-migrating counterparts, they remain a small minority. What factors are important in determining who decides to migrate and who decides to remain at home? 2

From Neoclassical Economics to the Mobility Transition

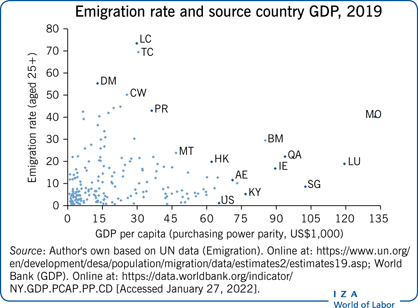

Neoclassical economic models posit that the primary driving factor behind migration is the expected difference in wages (discounted future income streams) between origin and destination countries (Sjaastad, 1962 ; Borjas, 1989 ; Clark, Hatton, & Williamson, 2007 ). All else equal, when the wage gap, minus the costs associated with moving between origin and destination, is high, these models predict large flows of labor migrants. In equilibrium, as more individuals move from origin to destination countries, the wage differential narrows, which in turn leads to zero net migration (Lewis, 1954 ; Harris & Todaro, 1970 ). Traditional models predict a negative monotonic relationship between the wage gap and the number of migrants (e.g., Sjaastad, 1962 ). However, the predictions of neoclassical models are not well supported by the empirical record. Empirical evidence shows that, at least in a cross-section, the relationship between economic development and migration is more akin to an inverted U. For countries with low levels of per capita income, we observe little migration due to a liquidity constraint: at this end of the income distribution, individuals do not have sufficient resources to cover even minor costs associated with moving abroad. Increasing income helps to decrease this constraint, and consequently we observe increased levels of emigration as incomes rise (de Haas, 2007 ). This effect, however, is not monotonic: as countries reach middle-income status, declining wage differentials lead to flattening rates of emigration, and then decreasing rates as countries enter later stages of economic development. 3

Some research explains this curvilinear relationship by focusing on the interaction between emigration incentives and constraints : for example, increased income initially makes migration more affordable (reduces constraints), but also simultaneously reduces the relative economic benefits of migrating as the wage differential narrows (as potential migrants now have the financial capacity to enhance local amenities) (Dao, Docquier, Parsons, & Peri, 2016 ). The theoretical underpinnings of this interaction, however, are not without controversy. Clemens identifies several classes of theory that attempt to explain this curvilinear relationship—a relationship that has been referred to in the literature as the mobility transition (Clemens, 2014 ). These theories include: demographic changes resulting from development that also favor emigration up to a point (Easterlin, 1961 ; Tomaske, 1971 ), the loosening of credit restraints on would-be migrants (Vanderkamp, 1971 ; Hatton & Williamson, 1994 ), a breakdown of information barriers via the building of transnational social networks (Epstein, 2008 ), structural economic changes in the development process that result in worker dislocation (Zelinsky, 1971 ; Massey, 1988 ), the dynamics of economic inequality and relative deprivation (Stark, 1984 ; Stark & Yitzhaki, 1988 ; Stark & Taylor, 1991 ), and changing immigration policies in destination countries toward increasingly wealthy countries (Clemens, 2014 ). While each of these play some role in the mobility transition curve, Dao et al. ( 2016 ) run an empirical horse race between numerous explanations and find that changing skill composition resulting from economic development is the most substantively important driver. Economic development is correlated with an increase in a country’s level of education; an increase in the level of education, in turn, is correlated with increased emigration. However, traditional explanations involving microeconomic drivers such as income, credit constraints, and economic inequality remain important factors (Dao et al., 2016 ). The diversity of explanations offered for the mobility transition curve indicates that while most research agrees the inverted-U relationship is an accurate empirical portrayal of the relationship between development and migration, little theoretical agreement exists on what drives this relationship. Complicating this disagreement is the difficulty of empirically disentangling highly correlated factors such as income, skill composition, and demographic trends in order to identify robust causal relationships.

Political Conditions at the Origin

While there is a scholarly consensus around the mobility transition and the role of economic conditions, emerging research suggests that the political environment in the origin country may also be salient. We do not refer here to forced migration, such as in the case of those who leave because they are fleeing political persecution or violent conflict. Rather, we focus on political conditions in the homeland that influence a potential migrant’s decision to emigrate voluntarily. Interpretations of how, and the extent to which, political conditions in origin countries (independent of economic conditions) influence the decision to migrate have been heavily influenced by Hirschman’s “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty” framework (Hirschman, 1970 , 1978 ). Hirschman argues that the opportunity to exit—to exit a firm, an organization, or a country—places pressure on the local authorities; voting with one’s feet forces organizations to reassess their operations.

When applied to the politics of emigration, Hirschman’s framework generates two different hypotheses. On the one hand, politicians may allow, encourage, or force the emigration of groups that oppose the regime as a political safety valve of sorts. This provides the government with a mechanism with which to manage potential political challengers by encouraging their exit. On the other hand, politicians—especially those in autocracies—may actively work to prevent exit because they fear the emigration of economic elites, the highly skilled, and others who have resources vital to the survival of the regime. 4

A small number of studies investigate how local-level, rather than national, political circumstances affect a potential migrant’s calculus. The limited empirical evidence currently available suggests that local conditions are substantively important determinants of the emigration decision. When individuals are highly satisfied with local amenities such as their own standard of living, quality of public services, and overall sense of physical security, they express far less intention to migrate compared with highly dissatisfied individuals (Dustmann & Okatenko, 2014 ). Furthermore, availability of public transport and access to better education facilities decreases the propensity to express an intention to emigrate (Cazzuffi & Modrego, 2018 ). This relationship holds across all levels of wealth and economic development, and there is some evidence that satisfaction with local amenities matters as much as, or even more than, income or wealth (Dustmann & Okatenko, 2014 ).

Political corruption, on both national and local levels, also has substantively important effects on potential migrants, especially those who are highly skilled. Broadly defined as the use of public office for political gain, political corruption operates as both a direct and an indirect factor promoting emigration. 5 Firstly, corruption may have a direct effect on the desire to emigrate in that it can decrease the political and economic power of an individual, leading to a lower standard of living and poorer quality of life in origin countries. If the reduction in life satisfaction resulting from corruption is sufficiently high—either by itself or in combination with other “push” factors—then the exit option becomes more attractive (Cooray & Schneider, 2016 ). Secondly, corruption also operates through indirect channels that influence other push factors. Given the large literature on how political corruption influences a number of development outcomes, it is conceivable that corruption affects the decision-making process of a potential migrant through its negative effect on social spending, education, and public health (Mo, 2001 ; Mauro, 1998 ; Gupta, Davoodi, & Thigonson, 2001 ).

The combination of its direct and indirect impacts means that corruption could be a significant part of a migrant’s decision-making process. At present there is limited work exploring this question, and the research does not yield a consensus. Some scholars argue that political corruption has no substantive effect on total bilateral migration, but that it does encourage migration among the highly skilled (Dimant, Krieger, & Meierrieks, 2013 ). This is the case, the argument goes, because corruption causes the greatest relative harm to the utility of those who have invested in human capital, who migrate to escape the negative effect on their fixed investment. In contrast, others find that a high level of corruption does increase emigration at the aggregate level (Poprawe, 2015 ). More nuanced arguments take into account the intensity of corruption: low to moderate levels of corruption lead to increased emigration of all groups, and especially of the highly skilled. But at high levels of corruption, emigration begins to decrease, indicating that intense corruption can act as a mobility constraint (Cooray & Schneider, 2016 ). All of these existing accounts, however, employ state-level measures of corruption by non-governmental organizations, such as those produced by Transparency International. Scholars have yet to harness micro-level survey data to explore the influence of personal corruption perception on the individual’s decision-making process.

The Land of Hopes and Dreams

Given that an individual has decided to emigrate, the next decision point is to choose a destination country. Advanced industrial democracies, such as those in the OECD, are major migrant-receiving countries, but so are Russia and several Gulf countries including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (World Bank, 2016 ). A country’s constellation of political, economic, and social attributes is crucial to understanding an emigrant’s choice of destination. Potential migrants weigh all of these factors simultaneously when choosing a destination: will the destination allow political rights for the migrant and their children, is access to the labor market possible, and does the destination provide an opportunity for reunification with friends and family? In this section we focus on the non-economic factors that draw migrants to certain countries over others. In addition, we emphasize how skill level adds layers of complexity to a migrant’s calculus.

Political Environment, Both Formal and Informal

As noted earlier, traditional neoclassical models and their extensions place wage differentials and associated economic variables at the heart of a migrant’s choice. Gravity models posit that migrants choose a destination country based on their expected income—which itself is a function of the wage rate and the probability of finding employment in the destination—less the costs associated with moving (Ravenstein, 1885 ; Todaro, 1969 ; Borjas, 1989 ). A rigid focus on economic factors, however, blinds us to the empirical reality that a destination country’s political environment influences what destination a migrant chooses (Borjas, 1989 ). A country’s legal and political rights structure for migrants, as well as its level of tolerance for newcomers, is critical to migrants discriminating between an array of potential destinations. Fitzgerald, Leblang, and Teets ( 2014 ) argue, for example, that states with restrictive citizenship policies and strong radical right anti-immigrant parties will receive fewer migrants, while states with relatively liberal citizenship requirements and weak radical right political movements will receive more migrants. In the rational actor framework, migrants seek countries with hospitable political environments to maximize both their political representation in government and their access to labor market opportunities as a result of citizenship rights and social acceptance (Fitzgerald et al., 2014 ).

Using a broad sample of origin countries and 18 destination countries, they find that relative restrictiveness of citizenship policies and level of domestic support for the radical right are substantively important determinants of global migratory flows. Further, they find that these political variables condition a migrant’s choice of destination: the relative importance of economic factors such as the unemployment rate or the wage differential diminishes as a destination country’s political environment becomes more open for migrants. In other words, when migrants are choosing a destination country, political considerations may trump economic ones—a finding that is an important amendment to the primarily economics-focused calculus of the initial stage of the immigration decision.

However, prior to choosing and entering a destination country, a migrant must also navigate a country’s immigration policy—the regulation of both migrant entry and the rights and status of current migrants. While it is often assumed that a relatively more restrictive immigration policy deters entry, and vice versa, a lack of quantitative data has limited the ability of scholars to confirm this intuition cross-nationally. Money ( 1999 ) emphasizes that the policy output of immigration politics does not necessarily correlate with the outcome of international migrant flows. There are a number of unanswered questions in this field, including: is immigration policy a meaningful determinant of global flows of migration? Do certain kinds of immigration policies matter more than others? How does immigration policy interact with other political and economic factors, such as unemployment and social networks?

Only a handful of studies analyze whether or not immigration policy is a significant determinant of the size and character of migratory flows. Perhaps the most prominent answer to this question is the “gap hypothesis,” which posits that immigration rates continue to increase despite increasingly restrictive immigration policies in advanced countries (Cornelius & Tsuda, 2004 ). Some subsequent work seems to grant support to the gap hypothesis, indicating that immigration policy may not be a relevant factor and that national sovereignty as it relates to dictating migrant inflows has eroded significantly (Sassen, 1996 ; Castles, 2004 ). The gap hypothesis is not without its critics, with other scholars arguing that the existing empirical evidence actually lends it little or no support (Messina, 2007 ).

A more recent body of literature does indicate that immigration policy matters. Brücker and Schröder ( 2011 ), for example, find that immigration policies built to attract highly skilled migrants lead to higher admittance rates. They also show that diffusion processes cause neighboring countries to implement similar policy measures. Ortega and Peri ( 2013 ), in contrast to the gap hypothesis literature, find that restrictive immigration policy indeed reduces migrant inflows. But immigration policy can also have unintended effects on international migration: when entry requirements increase, migrant inflows decrease, but migrant outflows also decrease (Czaika & de Haas, 2016 ). This indicates that restrictive immigration policy may also lead to reduced circular migrant flows and encourage long-term settlement in destination countries.

Disaggregating immigration policy into its different components provides a clearer picture of how immigration policy may matter, and whether certain components matter more than others. Immigration policy is composed of both external and internal regulations. External regulations refer to policies that control migrant entry, such as eligibility requirements for migrants and additional conditions of entry. Internal regulations refer to policies that apply to migrants who have already gained status in the country, such as the security of a migrant’s legal status and the rights they are afforded. Helbling and Leblang ( 2017 ), using a comprehensive data set of bilateral migrant flows and the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) data set, find that, in general, external regulations prove slightly more important in understanding migrant inflows (Helbling, Bjerre, Römer, & Zobel, 2017 ). This indicates that potential migrants focus more on how to cross borders, and less on the security of their status and rights once they settle. They do find, however, that both external and internal components of immigration are substantively important to international migrant flows.

The effects of policy, however, cannot be understood in isolation from other drivers of migration. Firstly, poor economic conditions and restrictive immigration policy are mutually reinforcing: when the unemployment rate is elevated, restrictive policies are more effective in deterring migrant flows. An increase in policy effectiveness in poor economic conditions suggests that states care more about deterring immigration when the economy is performing poorly. Secondly, a destination country’s restrictive immigration policy is more effective when migrants come from origin countries that have a common colonial heritage. This suggests that cultural similarities and migrant networks help to spread information about the immigration policy environment in the destination country. Social networks prove to be crucial in determining how much migrants know about the immigration policies of destination countries, regardless of other cultural factors such as colonial heritage or common language (Helbling & Leblang, 2017 ). In summary, more recent work supports the idea that immigration policy of destination countries exerts a significant influence on both the size and character of international migration flows. Much work remains to be done in terms of understanding the nuances of specific immigration policy components, the effect of policy change over time, and through what mechanisms immigration policy operates.

Transnational Social Networks

None of this should be taken to suggest that only political and economic considerations matter when a potential migrant contemplates a potential destination; perhaps one of the biggest contributions to the study of bilateral migration is the role played by transnational social networks. Migrating is a risky undertaking, and to minimize that risk, migrants are more likely to move to destinations where they can “readily tap into networks of co-ethnics” (Fitzgerald et al., 2014 , p. 410). Dense networks of co-ethnics not only help provide information about economic opportunities, but also serve as a social safety net which, in turn, helps decrease the risks associated with migration, including, but not limited to, finding housing and integrating into a new community (Massey, 1988 ; Portes & Böröcz, 1989 ; Portes, 1995 ; Massey et al., 1993 ; Faist, 2000 ; Sassen, 1995 ; Light, Bernard, & Kim, 1999 ). Having a transnational network of family members is quite important to destination choice; if a destination country has an immigration policy that emphasizes family reunification, migrants can use their familial connections to gain economically valuable permanent resident or citizenship status more easily than in other countries (Massey et al., 1993 , p. 450; Helbing & Leblang, 2017 ). When the migrant is comparing potential destinations, countries in which that migrant has a strong social network will be heavily favored in a cost–benefit analysis.

Note, however, that even outside of a strict rational actor framework with perfect information, transnational social networks still may be quite salient to destination choice. An interesting alternative hypothesis for the patterns we observe draws on theories from financial market behavior which focus on herding. Migrants choosing a destination observe the decisions of their co-ethnics who previously migrated and assume that those decisions were based on a relevant set of information, such as job opportunities or social tolerance of migrants. New migrants then choose the same destination as their co-ethnics not based on actual exchanges of valuable information, but based solely on the assumption that previous migration decisions were based on rational calculation (Epstein & Gang, 2006 ; Epstein, 2008 ). This is a classic example of herding, and the existing empirical evidence on the importance of transnational social networks cannot invalidate this alternative hypothesis. One could also explain social network effects through the lens of cumulative causation or feedback loops: the initial existence of connections in destination countries makes the act of migration less risky and attracts additional co-ethnics. This further expands migrant networks in a destination, further decreasing risk for future waves of migrants, and so on (Massey, 1990 ; Fussel & Massey, 2004 ; Fussel, 2010 ).

No matter the pathway by which social networks operate, the empirical evidence indicates that they are one of the most important determinants of destination choice. Potential migrants from Mexico, for example, who are able to tap into existing networks in the United States face lower direct, opportunity, and psychological costs of international migration (Massey & Garcia España, 1987 ). This same relationship holds in the European context; a study of Bulgarian and Italian migrants indicates that those with “social capital” in a destination community are more likely to migrate and to choose that particular destination (Haug, 2008 ). Studies that are more broadly cross-national in nature also confirm the social network hypothesis across a range of contexts and time periods (e.g., Clark et al., 2007 ; Hatton & Williamson, 2011 ; Fitzgerald et al., 2014 ).

Despite the importance of social networks, it is, again, important to qualify their role in framing the choice of destinations. It seems that the existence of co-ethnics in destination countries most strongly influences emigration when they are relatively few in number. Clark et al. ( 2007 ), in their study of migration to the United States, find that the “friends and relatives effect” falls to zero once the migrant stock in the United States reaches 8.3% of the source-country population. In addition, social networks alone cannot explain destination choice because their explanatory power is context-dependent. For instance, restrictive immigration policies limiting legal migration channels and family reunification may dampen the effectiveness of networks (Böcker, 1994 ; Collyer, 2006 ). Social networks are not an independent force, but also interact with economic and political realities to produce the global migration patterns we observe.

The Lens of Skill

For ease of presentation, we have up to now treated migrants as a relatively homogeneous group that faces similar push and pull factors throughout the decision-making process. Of course, not all migrants experience the same economic, political, and social incentives in the same way at each stage of the decision-making process. Perhaps the most salient differentiating feature of migrants is skill or education level. Generally, one can discuss a spectrum of skill and education level for current migrants, from relatively less educated (having attained a high school degree or less) to relatively more educated (having attained a college or post-graduate degree). The factors presented here that influence destination choice interact with a migrant’s skill level to produce differing destination choice patterns.

A migrant’s level of education, or human capital, often serves as a filter for the political treatment he or she anticipates in a particular destination country. For instance, the American public has a favorable view of highly educated migrants who hold higher-status jobs, while simultaneously having an opposite view of migrants who have less job training and do not hold a college degree (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2010 ; Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2015 ). Indeed, the political discourse surrounding migration often emphasizes skill level and education as markers of migrants who “should be” admitted, across both countries and the ideological spectrum. 6 While political tolerance may be a condition of entry for migrants in the aggregate, the relatively privileged status of highly educated and skilled migrants in most destination countries may mean that this condition is not as salient.

While it is still an open question to what extent immigration policy influences international migration, it is clear that not all migrants face evenly applied migration restrictions. Most attractive destination countries have policies that explicitly favor highly skilled migrants, since these individuals often fill labor shortages in advanced industries such as high technology and applied science. Countries such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand all employ so-called “points-based” immigration systems in which those with advanced degrees and needed skills are institutionally favored for legal entry (Papademetriou & Sumption, 2011 ). Meanwhile, the United States maintains the H-1B visa program, which is restricted by educational attainment and can only be used to fill jobs in which no native talent is available (USCIS). Even if destination countries decide to adopt more restrictive immigration policies, the move toward restriction has typically been focused on low-skilled migrants (Peters, 2017 ). In other words, even if immigration policy worldwide becomes more restrictive, this will almost certainly not occur at the expense of highly skilled migrants and will not prevent them choosing their most preferred destination.

Bring It on Home to Me

This article began by asserting that international labor migration is an important piece of globalization, as significant as cross-border flows of capital, goods, and services. This section argues that migrant flows enhance flows of capital and commodities. Uniquely modern conditions such as advanced telecommunications, affordable and efficient international travel, and the liberalization of financial flows mean that diasporas—populations of migrants living outside their countries of origin—and home countries often re-engage with each other (Vertovec, 2004 ; Waldinger, 2008 ). This section reviews some of the newest and most thought-provoking research on international labor migration, research that explores diaspora re-engagement and how that re-engagement alters international flows of income, portfolio and foreign direct investment (FDI), trade, and migratory flows themselves.

Remittances

As previously argued, migration is often driven by the prospect of higher wages. Rational, utility-maximizing migrants incur the cost of migration in order to earn increased income that they could not earn at home. But when migrants obtain higher wages, this additional increment to income is not always designated for individual consumption. Often, migrants use their new income to send remittances, direct transfers of money from one individual to another across national borders. Once a marginal financial flow, in 2015 remittances totaled $431 billion, far outpacing foreign aid ($135 billion) and nearly passing private debt and portfolio equity ($443 billion). More than 70% of total global remittances flow into developing countries (World Bank, 2016 ). In comparison with other financial flows such as portfolio investment and FDI, remittances are more impervious to economic crises, suggesting that they may be a countercyclical force to global downturns (Leblang, 2017 ).

Remittances represent one of the most common ways in which migrants re-engage with their homeland and alter both global income flows and distribution. Why do migrants surrender large portions of their new income, supposedly the very reason they migrated in the first place, to their families back home? New economics of labor migration (NELM) theory argues that immigration itself is motivated by a family’s need or demand for remittances—that remittances are an integral part of a family’s strategy for diversifying household financial risk (Stark & Bloom, 1985 ). Remittances “are a manifestation of informal contractual agreements between migrants and the households from which they move,” indicating that remitting is not an individual-level or purely altruistic action but rather occurs in a larger social context, that of one’s immediate or extended family (European Asylum Support Office, 2016 , p. 15).

The impact of migrant remittances on countries of origin is multifaceted yet somewhat ambiguous. Most scholarly work focuses on whether remittances positively or negatively influence existing economic conditions. A number of studies find that remittances modestly reduce poverty levels in developing countries (Adams & Page, 2005 ; Yang & Martinez, 2006 ; Acosta, Calderon, Fajnzybler, & Lopez, 2008 ; Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, & Glinskaya, 2010 ). On other measures of economic well-being, such as growth, inequality, and health, the literature is quite mixed and no definitive conclusions can be drawn. For instance, some studies find that remittances encourage investment in human capital (Yang, 2008 ; Adams & Cuecuecha, 2010 ), while others find no such effect and suggest that families typically spend remittances on non-productive consumption goods (Chami, Fullenkamp, & Jahjah, 2003 ). Here we can only scratch the surface of the empirical work on remittances and economic outcomes. 7

Some of the most recent research in the field argues that remittances have a distinct political dimension, affecting regime support in developing countries and altering the conditions in which elections are held. Ahmed ( 2012 ), grouping remittances with foreign aid, argues that increased remittances allow autocratic governments to extend their tenure in office. These governments can strategically channel unearned government and household income to finance political patronage networks, which leads to a reduced likelihood of autocratic turnover, regime collapse, and mass protests against the regime. More recent research posits nearly the exact opposite: remittances are linked to a greater likelihood of democratization under autocratic regimes. Escriba-Folch, Meseguer, and Wright ( 2015 ) argue that since remittances directly increase household incomes, they reduce voter reliance on political patronage networks, undermining a key tool of autocratic stability.

Remittances may also play an important role in countries with democratic institutions, yet more research is needed to fully understand the conditions under which they matter and their substantive impact. Particularly, remittances may alter the dynamics of an election as an additional and external financial flow. There is evidence of political remittance cycles : the value of remittances spikes in the run-up to elections in developing countries. The total value of remittances to the average developing country increases by 6.6% during election years, and by 12% in elections in which no incumbent or named successor is running (O’Mahony, 2012 ). The effect is even larger in the poorest of developing countries. Finer-grained tests of this hypothesis provide additional support: using monthly and quarterly data confirms the existence of political remittance cycles, as well as using subnational rather than cross-national data (Nyblade & O’Mahony, 2014 ). However, these studies do not reveal why remittances spike, or what the effects of that spike are on electoral outcomes such as vote share, campaign financing, and political strategy.

Remittances represent a massive international financial flow that warrants more scholarly attention. While there are numerous studies on the relationship between remittances and key economic indicators, there remains much room for further work on their relationship to political outcomes in developing countries. Do remittances hasten the downfall of autocratic regimes, or do they contribute to autocratic stability? In democratic contexts, do remittances substantively influence electoral outcomes, and if so, which outcomes and how? Finally, do remittances prevent even more migration because they allow one “breadwinner from abroad” to provide for the household that remains in the homeland? While data limitations are formidable, these questions are important to the study of both international and comparative political economy.

Bilateral Trade

The argument that migrant or co-ethnic networks play an important role in international economic exchange is not novel. Greif ( 1989 , 1993 ) illustrates the role that the Maghrebi traders of the 11th century played in providing informal institutional guarantees that facilitated trade. This is but a single example. Cowen’s historical survey identifies not only the Phoenicians but also the “Spanish Jews [who] were indispensable for international commerce in the Middle Ages. The Armenians controlled the overland route between the Orient and Europe as late as the nineteenth century . Lebanese Christians developed trade between the various parts of the Ottoman empire” (Cowen, 1997 , p. 170). Rauch and Trindade ( 2002 ) provide robust empirical evidence linking the Chinese diaspora to patterns of imports and exports with their home country.

A variety of case studies document the importance of migrant networks in helping overcome problems of information asymmetries. In his study of Indian expatriates residing in the United States, Kapur ( 2014 ) documents how that community provides U.S. investors with a signal of the work ethic, labor quality, and business culture that exists in India. Likewise, Weidenbaum and Hughes ( 1996 ) chronicle the Bamboo Network—the linkages between ethnic Chinese living outside mainland China and their homeland—and how these linkages provide superior access to information and opportunities for investment.

Connections between migrant communities across countries affect cross-national investment even when these connections do not provide information about investment opportunities. In his work on the Maghrebi traders of the 11th century , Greif argues that this trading network was effective because it was able to credibly threaten collective punishment by all merchants if even one of them defected (Greif, 1989 , 1993 ). Grief shows that this co-ethnic network was able to share information regarding the past actions of actors (they could communicate a reputation)—something that was essential for the efficient functioning of markets in the absence of formal legal rules. Weidenbaum and Hughes reach a similar conclusion about the effectiveness of the Bamboo Network, remarking that “if a business owner violates an agreement, he is blacklisted. This is far worse than being sued, because the entire Chinese networks will refrain from doing business with the guilty party” (Hughes, 1996 , p. 51).

Migrants not only alter the flow of income by remitting to their countries of origin, but also influence patterns of international portfolio investment and FDI. Most existing literature on international capital allocation emphasizes monadic factors such as the importance of credible commitments and state institutional quality, failing to address explicitly dyadic phenomena that may also drive investment. Diaspora networks, in particular, facilitate cross-border investment in a number of ways. They foster a higher degree of familiarity between home and host countries, leading to a greater preference for investment in specific countries. Diaspora networks can also decrease information asymmetries in highly uncertain international capital markets in two ways. Firstly, they can provide investors with salient information about their homeland, such as consumer tastes, that can influence investment decision-making. Secondly, they can share knowledge about investment opportunities, regulation and procedures, and customs that decrease transaction costs associated with cross-border investment (Leblang, 2010 ). This place of importance for migrants suggests to the broader international political economy literature the importance of non-institutional mechanisms for channeling economic activity.

Although the hypothesized link between migrants and international investment has only recently been identified, the quantitative evidence available supports that hypothesis. Leblang ( 2010 ), using dyadic cross-sectional data, finds that diaspora networks “have both a substantively significant effect and a statistically significant effect on cross-border investment,” including international portfolio investment and FDI (p. 584). The effect of bilateral migratory flows correlates positively with the degree of information asymmetry: when informational imperfections are more pervasive in a dyad, migrants (especially the highly skilled) play a disproportionately large role in international capital allocation (Kugler, Levinthal, & Rapoport, 2017 ). Other quantitative studies find substantively similar results for FDI alone (e.g., Javorcik, Özden, Spatareanu, & Neagu, 2011 ; Aubry, Rapoport, & Reshef, 2016 ).

Many questions still remain unanswered. Firstly, does the effect of migrants on investment follow the waves of the global economy, or is it countercyclical as remittances have been shown to be? Secondly, how does this additional investment, facilitated by migrants, affect socioeconomic outcomes such as inequality, poverty, and economic development (Leblang, 2010 )? Does the participation of migrants lead to more successful FDI projects in developing countries because of their ability to break down information barriers? Within portfolio investment, do migrants lead to a preference for certain asset classes over others, and if so, what are the effects on bilateral and international capital markets? These are just a few directions in an area ripe for additional research.

Return Migration and Dual Citizenship

Besides financial flows, migrants themselves directly contribute to global flows of capital by returning to their countries of origin in large numbers. This phenomenon of return migration—or circular migration—can come in a few temporal forms, including long-term migration followed by a permanent return to a country of origin, or repeat migration in which a migrant regularly moves between destination and origin countries (Dumont & Spielvogel, 2008 ). While comparable data on return migration is scarce, some reports suggest that 20% to 50% of all immigrants leave their destination country within five years after their arrival (e.g., Borjas & Bratsberg, 1996 ; Aydemir & Robinson, 2008 ; Bratsberg, Raaum, & Sørlie, 2007 ; Dustmann & Weiss, 2007 ). An independent theoretical and empirical account of return migration does not yet exist in the literature and is beyond the scope of this paper. But in the rational actor framework, motivations to return home include a failure to realize the expected benefits of migration, changing preferences toward a migrant’s home country, achievement of a savings or other economic goal, or the opening of additional employment opportunities back home due to newly acquired experience or greater levels of economic development (Dumont & Spielvogel, 2008 ).

While most migration literature treats the country of origin as a passive actor that only provides the conditions for migration, new literature on return migration gives home country policies pride of place. Origin countries can craft policies that encourage diaspora re-engagement, incentivizing individuals to return home. Dual citizenship, for example, is an extension of extraterritorial rights, allowing migrants to retain full legal status in their home country. Dual citizenship “decreases the transaction costs associated with entering a host country’s labor market and makes it easier for migrants to return home” (Leblang, 2017 , p. 77). This leads migrants to invest their financial resources in the form of remittances back home as well as their valuable human capital. When states provide such extraterritorial rights, expatriates are 10% more likely to remit and 3% more likely to return home. Dual citizenship is also associated with a doubling of the dollar amount of remittances received by a home country (Leblang, 2017 ). These striking results suggest that in addition to the power of migrants to affect cross-border flows of money and people, countries of origin can also play a significant role.

Conclusion and Future Directions

This brief article has attempted to synthesize a broad range of literature from political science, economics, sociology, migration studies, and more to construct an account of international labor migration. To do so, the migratory process was broken down into distinct stages and decision points, focusing particularly on the decision to migrate, destination choice, and the re-engagement of migrants with their homeland. In doing so, the article also discussed the interlinkages of international migration with other fields of study in international political economy, including cross-border financial flows, trade, and investment. Through a multiplicity of approaches, we have gained a greater understanding of why people decide to move, why they decide to move to one country over another, and how and why they engage with the global economy and their homeland. Despite this intellectual progress, there remain many paths for future research at each stage of the migratory process; we highlight just a few of them here.

We know that income differentials, social ties, and local political conditions are important variables influencing the migration process. Yet the question remains: why do a small but growing number of people choose to leave while the overwhelming majority of people remain in their country of birth? Here, individual- or family-level subjective characteristics may be significant. There are a handful of observational studies that explore the relationship between subjective well-being or life satisfaction and the intention to migrate, with the nascent consensus being that life dissatisfaction increases the intention to migrate (Cai, Esipova, Oppenheimer, & Feng, 2014 ; Otrachshenko & Popova, 2014 ; Nikolova & Graham, 2015 ). But more research on intrinsic or subjective measures is needed to understand (a) their independent importance more fully and (b) how they interact with objective economic, political, and social factors. For instance, do those who are more optimistic migrate in larger numbers? Do minority individuals who feel they live in an environment in which diversity is not accepted feel a greater urge to leave home? Synthesizing these types of subjective variables and perceptions with the more prominent gravity-style models could result in a more complete picture of the international migration process.

For the “typical” migrant, one who is relatively less educated than the population in the chosen destination and does not have specialized skills, social networks are key to minimizing the risk of migrating and quickly tapping into economic opportunities in destination countries. Does this remain true for those who are highly educated? Although little empirical research exists on the topic, greater human capital and often-accompanying financial resources may operate as a substitute for the advantages offered by social networks, such as housing, overcoming linguistic barriers, and finding gainful employment. This would indicate that the “friends and family effect” is not as influential for this subset of migrants. Economic considerations, such as which destination offers the largest relative wage differential, or political considerations, such as the ease of quickly acquiring full citizenship rights, may matter more for the highly skilled. Neoclassical economic models of migration may best capture the behavior of migrants who hold human capital and who have the financial resources to independently migrate in a way that maximizes income or utility more broadly.

Since we have focused on international migration as a series of discrete decision points in this article, we have perhaps underemphasized the complexity of the physical migration process. In reality, migrants often do not pick a country and travel directly there, but travel through (perhaps several) countries of transit such as Mexico, Morocco, or Turkey along the way (Angel Castillo, 2006 ; Natter, 2013 ; Icduygu, 2005 ). There is little existing theoretical work to understand the role of transit countries in the migratory process, with much of it focusing on the potential for cooperation between destination and transit countries in managing primarily illegal immigration (Kahana & Lecker, 2005 ; Djajic & Michael, 2014 ; Djajic & Michael, 2016 ). Another related strand of the literature focuses on how wealthy destination countries are “externalizing” their immigration policy, encompassing a broader part of the migratory process than simply crossing a physically demarcated border (Duvell, 2012 ; Menjivar, 2014 ). But many questions remain, such as the following: how do we understand those who desire to enter, say, the United States, but instead relocate permanently to Mexico along the way? How do countries of transit handle the pressure of transit migrants, and how does this affect economic and political outcomes in these countries?

Finally, the focus of nearly all literature on international migration (and this article as a byproduct) implicitly views advanced economies as the only prominent destinations. However, this belies the fact that 38% of all migration stays within the “Global South” (World Bank, 2016 ). While there is certainly some literature on this phenomenon (see Ratha & Shaw, 2007 ; Gindling, 2009 ; Hujo & Piper, 2007 ), international political economy scholars have yet to sufficiently tackle this topic. The overarching research question here is: do the same push and pull factors that influence the decision to migrate and destination choice apply to those who migrate within the Global South? Do we need to construct new theories of international migration with less emphasis on factors such as wage differentials and political tolerance, or are these sufficient to understand this facet of the phenomenon? If we fail to answer these questions, we may miss explaining a significant proportion of international migration with its own consequences and policy implications.

- Abreu, A. (2012). The New Economics of Labor Migration: Beware of Neoclassicals Bearing Gifts. Forum for Social Economics , 41 (1), 46–67.

- Acosta, P. , Calderon, C. , Fajnzybler, P. , & Lopez, H. (2008). What Is the Impact of International Remittances on Poverty and Inequality in Latin America? World Development , 36 (1), 89–114.

- Adams, R., Jr. (2011). Evaluating the Economic Impact of International Remittances on Developing Countries Using Household Surveys: A Literature Review. Journal of Development Studies , 47 (6), 809–828.

- Adams, R., Jr. , & Cuecuecha, A. (2010). Remittances, Household Expenditure and Investment in Guatemala. World Development , 38 (11), 1626–1641.

- Adams, R., Jr. , & Page, J. (2005). Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Development , 33 (10), 1645–1669.

- Ahmed, F. Z. (2012). The Perils of Unearned Foreign Income: Aid, Remittances, and Government Survival. American Political Science Review , 106 (1), 146–165.

- Akerman, S. (1976). Theories and Methods of Migration Research. In H. Runblom & H. Norman (Eds.), From Sweden to America: A History of the Migration . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Angel Castillo, M. (2006). Mexico: Caught Between the United States and Central America . Migration Policy Institute.

- Aubry, A. , Rapoport, H. , & Reshef, A. (2016). Migration, FDI, and the Margins of Trade. Mimeo . Paris School of Economics.

- Aydemir, A. , & Robinson, C. (2008). Global Labour Markets, Return, and Onward Migration. Canadian Journal of Economics , 41 (4), 1285–1311.

- Böcker, A. (1994). Chain Migration over Legally Closed Borders: Settled Immigrants as Bridgeheads and Gatekeepers. Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences , 30 (2), 87–106.

- Borjas, G. J. (1989). Economic Theory and International Migration. International Migration Review , 23 (3), 457–485.

- Borjas, G. J. , & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who Leaves? The Outmigration of the Foreign-Born. Review of Economics and Statistics , 41 (4), 610–621.

- Bratsberg, B. , Raaum, O. , & Sørlie, K. (2007). Foreign-Born Migration to and from Norway. In Ç. Özden & M. Schiff (Eds.), International Migration, Economic Development and Policy . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brücker, H. , & Schröder, P. J. H. (2011). Migration regulation contagion. European Union Politics , 12 (3), 315–335.

- Cai, R. , Esipova, N. , Oppenheimer, M. , & Feng, S. (2014). International Migration Desires Related to Subjective Well-Being. IZA Journal of Migration , 3 (8), 1–20.

- Castles, S. (2004). Why Migration Policies Fail. Ethnic and Racial Studies , 27 (2), 205–227.

- Cazzuffi, C. , & Modrego, F. (2018). Place of Origin and Internal Migration Decisions in Mexico. Spatial Economic Analysis , 13 (1), 1–19.

- Chami, R. , Fullenkamp, C. , & Jahjah, S. (2003). Are Immigrant Remittance Flows a Source of Capital for Development ? IMF Working Paper 03/189.

- Clark, X. , Hatton, T. J. , & Williamson, J. G. (2007). Explaining US Immigration, 1971–1998. Review of Economics and Statistics , 89 (2), 359–373.

- Clemens, M. A. (2014). Does Development Reduce Migration ? IZA Discussion Paper No. 8592.

- Collier, P. , & Hoeffler, A. (2014). Migration, Diasporas and Culture: An Empirical Investigation . Unpublished manuscript.

- Collyer, M. (2006). When Do Social Networks Fail to Explain Migration? Accounting for the Movement of Algerian Asylum-Seekers to the UK. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 31 (4), 699–718.

- Constant, A. , & Massey, D. S. (2002). Return Migration by German Guestworkers: Neoclassical versus New Economic Theories. International Migration , 4 0(4), 5–38.

- Cooray, A. , & Schneider, F. (2016). Does Corruption Promote Emigration? An Empirical Examination. Journal of Population Economics , 29 , 293–310.

- Cornelius, W. A. , & Tsuda, T. (2004). Controlling Immigration: The Limits of Government Intervention . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cowen, R. (1997). Global Diasporas: An Introduction . London: Routledge.

- Czaika, M. , & de Haas, H. (2016). The Effect of Visas on Migration Processes. International Migration Review , 51 (4), 893–926.

- Dao, T. H. , Docquier, F. , Parsons, C. , & Peri, G. (2018). Migration and Development: Dissecting the Anatomy of the Mobility Transition. Journal of Development Economics , 132 , 88–101.

- Dao, T. H. , Docquier, F. , Parsons, C. , & Peri, G. (2016). Migration and Development: Dissecting the Anatomy of the Mobility Transition . IZA Discussion Paper No. 10272.

- De Haas, H. (2007). Turning the Tide? Why Development Will Not Stop Migration. Development and Change , 38 , 819–841.

- Dimant, E. , Krieger, T. , & Meierrieks, D. (2013). The Effect of Corruption on Migration, 1985–2000. Applied Economics Letters , 20 (13), 1270–1274.

- Djajic, S. , & Michael, M. S. (2014). Controlling Illegal Immigration: On the Scope for Cooperation with a Transit Country. Review of International Economics , 22 (4), 808–824.

- Djajic, S. , & Michael, M. S. (2016). Illegal Immigration, Foreign Aid, and the Transit Countries. CESifo Economic Studies , 572–593.

- Dumont, J.-C. , & Spielvogel, G. (2008). Return Migration: A New Perspective. International Migration Outlook 2008 . OECD, 166–212.

- Dustmann, C. , & Okatenko, A. (2014). Out-Migration, Wealth Constraints, and the Quality of Local Amenities. Journal of Development Economics , 110 , 52–63.

- Dustmann, C. , & Weiss, Y. (2007). Return Migration: Theory and Empirical Evidence from the UK. British Journal of Industrial Relations , 45 (2), 236–256.

- Duvell, F. (2012). Transit Migration: A Blurred and Politicized Concept. Population, Space and Place , 18 , 415–427.

- Easterlin, R. A. (1961). Influences in European Overseas Emigration Before World War I. Economic Development and Cultural Change , 9 (3), 331–351.

- Epstein, G. (2008). Herd and Network Effects in Migration Decision-Making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 34 (4), 567–583.

- Epstein, G. , & Gang, I. (2006). The Influence of Others on Migration Plans. Review of Development Economics , 10 (4), 652–665.

- Escriba-Folch, A. , Meseguer, C. , & Wright, J. (2015). Remittances and Democratization. International Studies Quarterly , 59 (3), 571–586.

- European Asylum Support Office . (2016). The Push and Pull Factors of Asylum-Related Migration: A Literature Review .

- Faist, T. (2000). The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Space . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fitzgerald, J. , Leblang, D. , & Teets, J. C. (2014). Defying the Law of Gravity: The Political Economy of International Migration. World Politics , 66 (3), 406–445.

- Fussel, E. (2010). The Cumulative Causation of International Migration in Latin America. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 630 , 162–177.

- Fussel, E. , & Massey, D. (2004). The Limits to Cumulative Causation: International Migration from Mexican Urban Areas. Demography , 41 (1), 151–171.

- Gindling, T. H. (2009). South–South Migration: The Impact of Nicaraguan Immigrants on Earnings, Inequality, and Poverty in Costa Rica. World Development , 37 (1), 116–126.

- Gould, J. D. (1979). European Inter-Continental Emigration 1815–1914: Patterns and Causes. Journal of European Economic History , 8 (3), 593–679.

- Greif, A. (1989). Reputation and Coalitions in Medieval Trade: Evidence on the Maghribi Traders. Journal of Economic History , 49 (4), 857–882.

- Greif, A. (1993). Contract Enforceability and Economic Institutions in Early Trade: The Maghribi Traders’ Coalition. American Economic Review , 83 (3), 525–548.

- Grogger, J. , & Hanson, G. H. (2011). Income Maximization and the Selection and Sorting of International Migrants. Journal of Development Economics , 95 , 42–57.

- Gupta, S. , Davoodi, H. , & Tiongson, E. (2001). Corruption and the Provision of Healthcare and Education Services. In A. Jain (Ed.), The Political Economy of Corruption . New York: Routledge.

- Hainmueller, J. , & Hiscox, M. J. (2010). Attitudes toward Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment. American Political Science Review , 104 (1), 61–84.

- Hainmueller, J. , & Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The Hidden Immigration Consensus: A Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes toward Immigrants. American Journal of Political Science , 59 (3), 529–548.

- Harris, J. R. , & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, Unemployment and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis. American Economic Review , 60 (1), 126–142.

- Hatton, T. J. , & Williamson, J. G. (1994). What Drove the Mass Migrations from Europe in the Late Nineteenth Century? Population and Development Review , 20 (3), 533–559.

- Hatton, T. J. , & Williamson, J. G. (2011). Are Third World Emigration Forces Abating? World Development , 39 (1), 20–32.

- Haug, S. (2008). Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 34 (4), 585–605.

- Helbling, M. , Bjerre, L. , Römer, F. , & Zobel, M. (2017). Measuring Immigration Policies: The IMPIC-Database. European Political Science, 16 (1), 79–98.

- Helbling, M. , & Leblang, D. (forthcoming). Controlling Immigration? European Journal of Political Research .

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and Sates . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hirsh, A. O. (1978). “Exit, Voice, and the State.” World Politics , 31 (1), 90–107.

- Hujo, K. , & Piper, N. (2007). South–South Migration: Challenges for Development and Social Policy. Development , 50 (4), 1–7.

- Icduygu, A. (2005). Transit Migration in Turkey: Trends, Patterns, and Issues . Euro-Mediterranean Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration Research Report 2005/04.

- Javorcik, B. , Özden, C. , Spatareanu, M. , & Neagu, C. (2011). Migrant Networks and Foreign Direct Investment. Journal of Development Economics , 94 , 231–241.

- Kahana, N. , & Lecker, T. (2005). Competition as a Track for Preventing Illegal Immigration. Economics of Governance , 6 , 33–39.

- Kapur, D. (2014). Political Effects of International Migration. Annual Review of Political Science , 17 , 479–502.

- Kugler, M. , Levinthal, O. , & Rapoport, H. (2017). Migration and Cross-Border Financial Flows . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8034.

- Leblang, D. (2010). Familiarity Breeds Investment: Diaspora Networks and International Investment. American Political Science Review , 104 (3), 584–600.

- Leblang, D. (2017). Harnessing the Diaspora: Dual Citizenship, Migrant Return, and Remittances. Comparative Political Studies , 50 (1), 75–101.

- Lewis, A. W. (1954). Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor. The Manchester School , 22 (2), 139–191.

- Lichter, D. T. (1983). Socioeconomic Returns to Migration among Married Women. Social Forces , 62 (2), 487–503.

- Light, I. , Bernard, R. B. , & Kim, R. (1999). Immigrant Incorporation in the Garment Industry of Los Angeles. International Migration Review , 33 (1), 5–25.

- Lokshin, M. , Bontch-Osmolovski, M. , & Glinskaya, E. (2010). Work-Related Migration and Poverty Reduction in Nepal. Review of Development Economics , 14 (2), 323–332.

- Massey, D. S. (1988). Economic Development and International Migration in Comparative Perspective. Population and Development Review , 14 (3), 383–413.

- Massey, D. S. (1990). Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration. Population Index , 56 (1), 3–26.

- Massey, D. S. , Arango, J. , Hugo, G. , Kouaouci, A. , Pellegrino, A. , & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review , 19 (3), 431–466.

- Massey, D. S. , & Garcia España, F. (1987). The Social Process of International Migration. Science , 237 (4816), 733–738.

- Mauro, P. (1998). Corruption and the Composition of Government Expenditure. Journal of Public Economics , 69 , 263–279.

- Menjivar, C. (2014). Immigration Law Beyond Borders: Externalizing and Internalizing Border Controls in an Era of Securitization. Annual Review of Law and Social Science , 10 , 353–369.

- Messina, A. M. (2007). The Logics and Politics of Post-WWII Migration to Western Europe . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mincer, J. (1978). Family Migration Decisions. Journal of Political Economy , 86 (51), 749–773.

- Miller, M. K. , & Peters, M. E. (2018). Restraining the Huddled Masses: Migration Policy and Autocratic Survival . British Journal of Political Science .

- Mo, P. H. (2001). Corruption and Economic Growth. Journal of Comparative Economics , 29 , 66–79.

- Money, J. (1999). Fences and Neighbors: The Political Geography of Immigration Control . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Morrison, D. R. , & Lichter, D. T. (1988). Migration and Female Employment. Journal of Marriage and Family , 50 (1), 161–172.

- Natter, K. (2013). The Formation of Morocco’s Policy Towards Irregular Migration (2000–2007): Political Rationale and Policy Processes. International Migration , 52 (5), 15–28.

- Nikolova, M. , & Graham, C. (2015). Well-Being and Emigration Intentions: New Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Unpublished manuscript.

- Nyblade, B. , & O’Mahony, A. (2014). Migrants Remittances and Home Country Elections: Cross-National and Subnational Evidence. Studies in Comparative International Development , 49 (1), 44–66.

- O’Mahony, A. (2012). Political Investment: Remittances and Elections. British Journal of Political Science , 43 (4), 799–820.

- Ortega, F. , & Peri, G. (2013). The Effect of Income and immigration Policies on International Migration. Migration Studies , 1 (1), 47–74.

- Otrachshenko, V. , & Popova, O. (2014). Life (Dis)satisfaction and the Intention to Migrate: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Socio-Economics , 48 , 40–49.

- Papademetriou, D. , & Sumption, M. (2011). Rethinking Points Systems and Employer-Based Selected Immigration . Migration Policy Institute.

- Peters, M. (2017). Trading Barriers: Immigration and the Remaking of Globalization . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Poprawe, M. (2015). On the Relationship between Corruption and Migration: Evidence from a Gravity Model of Migration. Public Choice , 163 , 337–354.

- Portes, A. (Ed.). (1995). The Economic Sociology of Immigration . New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Portes, A. , & Böröcz, J. (1989). Contemporary Immigration: Theoretical Perspectives on its Determinant and Modes of Incorporation. International Migration Review , 23 (3), 606–630.

- Rapoport, H. , & Docquier, F. (2006). The Economics of Migrants’ Remittances. In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook on the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity . New York: Elsevier-North Holland.

- Ratha, D. , & Shaw, W. (2007). South-South Migration and Remittances . World Bank WP 102.

- Rauch, J. E. , & Trindade, V. (2002). Ethnic Chinese Networks in International Trade. Review of Economics and Statistics , 84 (1), 116–130.

- Ravenstein, E. G. (1885). The Laws of Migration. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society of London , 48 (2), 167–235.

- Sassen, S. (1995). Immigration and Local Labour Markets. In A. Portes (Ed.), The Economic Sociology of Immigration . New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Sassen, S. (1996). Losing Control? Sovereignty in the Age of Globalization . New York: Columbia University Press.

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in Human Capital. American Economic Review , 51 (1), 1–17.

- Severin, T. , & Martin, M. (2018). German Parties Edge Closer to Coalition with Migration Deal . Reuters, February 2.

- Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The Costs and Returns of Human Migration. Journal of Political Economy , 70 (5), 80–93.

- Stark, O. (1984). Rural-To-Urban Migration in LDCs: A Relative Deprivation Approach. Economic Development and Cultural Change , 32 (3), 475–486.

- Stark, O. , & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The New Economics of Labor Migration. American Economic Review , 75 (2), 173–178.

- Stark, O. , & Levhari, D. (1982). On Migration and Risk in LDCs. Economic Development and Cultural Change , 31 (1), 191–196.

- Stark, O. , & Taylor, J. E. (1991). Migration Incentives, Migration Types: The Role of Relative Deprivation. The Economic Journal , 101 (408), 1163–1178.

- Stark, O. , & Yitzhaki, S. (1988). Migration as a Response to Relative Deprivation. Journal of Population Economics , 1 (1), 57–70.

- Taylor, J. E. (1999). The New Economics of Labour Migration and the Role of Remittances in the Migration Process. International Migration , 37 (1), 63–88.

- Todaro, M. P. (1969). A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Employment in Less Developed Countries. American Economic Review , 59 (1), 138–148.

- Tomaske, J. A. (1971). The Determinants of Intercountry Differences in European Emigration: 1881–1900. Journal of Economic History , 31 (4), 840–853.

- Transparency International . (2018). What is corruption

- United Kingdom Independence Party . (2015). UKIP Launches Immigration Policy .

- United Nations Population Division . (2012). Trends in Total Migrant Stock .

- United Nations Population Division . (2013). International Migration: Age and Sex Distribution. Population Facts, September.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services . (2018). H-1B Fiscal Year 2018 Cap Season .

- USA Today . (2014) (20 November). Full Text: Obama’s Immigration Speech .

- Vanderkamp, J. (1971). Migration Flows, Their Determinants and the Effects of Return Migration. Journal of Political Economy , 79 (5), 1012–1031.

- Vertovec, S. (2004). Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation. International Migration Review , 38 (3), 970–1001.

- Waldinger, R. (2008). Between “Here” and “There”: Immigrant Cross-Border Activities and Loyalties. International Migration Review , 42 (Spring), 3–29.

- Weidenbaum, M. , & Hughes, S. (1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia . New York: Martin Kessler Books.

- World Bank . (2016). Migration and Remittances Factbook 2016 . 3rd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Yang, D. (2008). International Migration, Remittances, and Household Investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks. The Economic Journal , 118 (528), 591–630.

- Yang, D. , & Martinez, C. (2006). Remittances and Poverty in Migrants Home Areas: Evidence from the Philippines. In C. Ozden & M. Schiff (Eds.), International Migration, Remittances and the Brain Drain . Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Zaiceva, A. , & Zimmerman, K. (2014). Migration and the Demographic Shift. IZA Discussion Paper #8743 .

- Zelinsky, W. (1971). The Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition. Geographical Review , 61 (2), 219–249.

1. Our use of the term international labor migration follows academic and legal conventions; we use the term migration to refer to the voluntary movement of people across national borders, either in a temporary or permanent fashion. This excludes any discussion of refugees, asylum seekers, or any other groups that are forced to migrate.

2. We do not have space in this article to delve into the theoretical and empirical work unpacking the effect of demographic characteristics—age, gender, marital status, household size, and so forth on the migration decision and on subsequent flows of migrants. For comprehensive reviews, see Lichter ( 1983 ), Morrison and Lichter ( 1988 ); United Nations Population Division ( 2013 ); and Zaiceva and Zimmerman ( 2014 ).

3. Zelinsky ( 1971 ) originally identified this relationship and termed it mobility transition curve . A wealth of empirical work supports Zelinsky’s descriptive theory in a number of contexts (see Akerman, 1976 ; Gould, 1979 ; Hatton & Williamson, 1994 ; and Dao et al., 2016 ).

4. For a review of the arguments as well as some empirical tests, see Miller and Peters ( 2018 ) and Docquier, Lodigiani, Rapoport, and Schiff ( 2018 ).

5. Transparency International. “What is corruption?”

6. For example, former United Kingdom Independence Party leader Nigel Farage has called for the United Kingdom to adopt an immigration system that only allows in highly skilled migrants (“UKIP launches immigration policy”). In 2014, US President Barack Obama emphasized that he wanted to attract international students to American universities and that they “create jobs, businesses, and industries right here in America” (USA Today: “Full text: Obama’s immigration speech”). A key issue in Germany’s 2018 government formation was the creation of skill-based migration laws (Severin & Martin, 2018 ).

7. For a more comprehensive review, see Rapoport and Docquier ( 2006 ); and Adams ( 2011 ).

Related Articles

- Space, Mobility, and Legitimacy

- Immigration and Foreign Policy

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 27 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.148.24.167]

- 185.148.24.167

Character limit 500 /500

Global migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the unstoppable force of demography

- Original Paper

- Published: 13 January 2021

- Volume 157 , pages 417–449, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Thu Hien Dao 1 , 2 ,

- Frédéric Docquier 3 ,

- Mathilde Maurel 4 , 5 , 6 &

- Pierre Schaus 7

10k Accesses

17 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

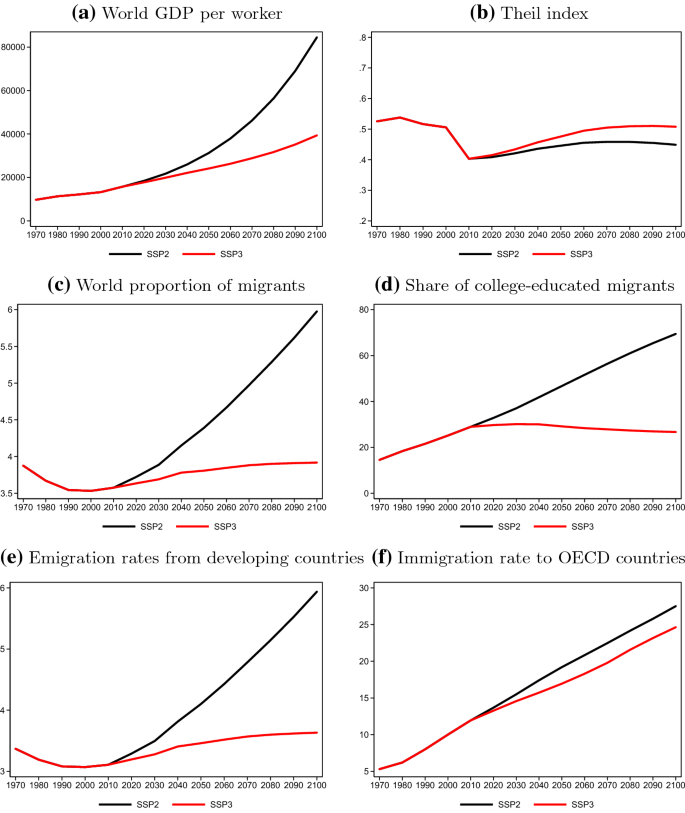

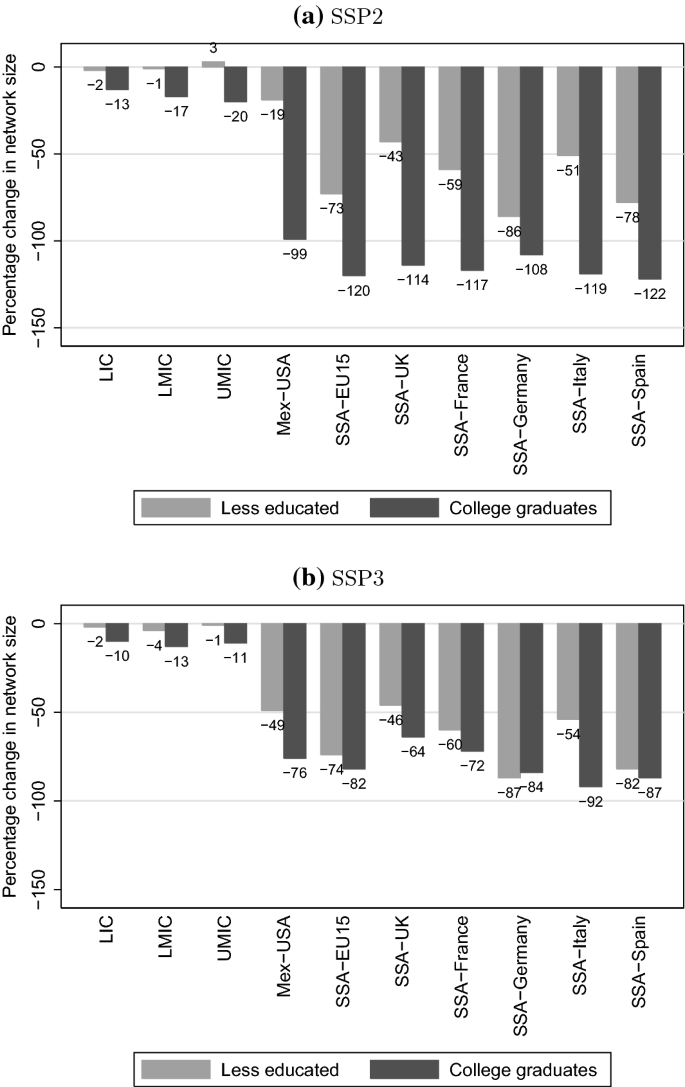

This paper sheds light on the global migration patterns of the past 40 years, and produces migration projections for the 21st century. To do this, we build a simple model of the world economy, and we parameterize it to match the economic and socio-demographic characteristics of the world in the year 2010. We conduct backcasting and nowcasting exercises, which demonstrate that our model fits very well the past and ongoing trends in international migration, and that historical trends were mostly governed by demographic changes. Then, we describe a set of migration projections for the 21st century. In line with the backcasts, our world migration prospects are mainly governed by socio-demographic changes. Using immigration restrictions or development policies to curb these pressures requires sealing borders or triggering unprecedented economic takeoffs in migrants’ countries of origin. Increasing migration is thus a likely phenomenon for the 21st century.

Similar content being viewed by others

What Is Globalisation?

Migration and Immigrants in Europe: A Historical and Demographic Perspective

The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Between 1960 and 2019, the worldwide stock of international migrants increased from 92 to 270 million, almost at the same pace as the world population. The worldwide share of migrants has fluctuated around 3% until 2010 (Ozden et al. 2011 ), with a rise since then until reaching 3.5% in 2019. In contrast, the foreign-born population increased more rapidly than the total population in high-income countries (HIC), boosting the average proportion of foreigners from 4.5 to 12.0% (+7.5 percentage points). A remarkable fact is that this change is mostly explained by the inflow of immigrants from less developed countries (LDC). The underlying root causes of this trend are known (population growth disparities between rich and poor countries, economic inequality, increased globalization, political instability, etc.). However, quantitatively speaking, little is known about their relative importance, and about the changing educational structure of past migration flows. Furthermore, the very same root causes are all projected to exert a strong influence on migration in the coming decades, while little is known about the predictability of future migration flows. This paper sheds light on these issues, addressing key questions such as: How have past income disparities, educational changes and population growth differentials shaped past migration flows? What are the pairs of countries responsible for large variations in low-skilled and high-skilled migration? How many potential migrants can be expected for the 21st century? How will future changes in education and productivity affect migration flows in general, and migration pressures to HIC in particular? Can development or visa policies be implemented to limit these flows?