- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

The real 'hamnet' died centuries ago, but this novel is timeless.

Heller McAlpin

In the 20 years since the publication of her first novel, After You'd Gone, Irish-born Maggie O'Farrell has wooed readers with intricately plotted, lushly imagined fiction featuring nonconformist women buffeted by the essential unpredictability of life, which can turn on a dime. O'Farrell's last book, I Am, I Am, I Am (2018), was a nonfiction account of her own unpredictable life, filtered through 17 dramatic, near-death experiences, from her hair-raising childhood through her middle child's harrowing, periodic anaphylactic attacks brought on by a life-threatening immunological disorder.

With her eighth novel, O'Farrell brilliantly turns to historical fiction to confront a parent's worst nightmare: the death of a child. Set in Stratford, England, in the late 16th century, Hamnet imagines the emotional, domestic, and artistic repercussions after the world's most famous (though never named) playwright and his wife lose their only son, 11-year-old Hamnet, to the bubonic plague in 1596. Four years later, the boy's father transposes his grief into his masterpiece — titled with a common variant of his son's name — in which the father dies and the son lives to avenge him.

O'Farrell's narratives are rarely straightforwardly chronological. In Hamnet, she toggles between two timelines, one beginning on the day the plague first afflicts Hamnet's twin sister Judith, the other circling back to the beginning of their parents' passionate relationship some 15 years earlier.

Movie Reviews

'all is true' finds melancholy and magic in shakespeare's final years.

Author Interviews

Bloody-scepter'd 'tyrant' explores shakespeare's take on politics.

In this telling, the woman we know as Anne Hathaway is called Agnes, pronounced Ann-yis, which O'Farrell explains is how her name appeared in her father's will. She's a wonderful character, a free spirit and healer who, like her late mother, is most at home in the woods. But she's also a Cinderella in her nasty stepmother's household, in which the future playwright — still in his teens with an uncertain future — is indentured as a Latin tutor to help settle a debt incurred by his errant father.

The two abused misfits recognize something special in each other, and the chemistry between them is palpable. A first kiss, later followed by sex that literally rocks and upends the apples in the storage shed, would be heavy-handed in its biblical overtones were it not so beautifully written. Hamnet is, among other things, a love story about a sorely tested marriage.

But before we meet his parents, we meet Hamnet, a smart but easily distractible boy, as he desperately seeks help for his twin sister, who has suddenly taken ill. With rising panic, he checks upstairs and down in his family's small apartment and his grandparents' adjacent house, and is anguished to discover that his mother, grandmother, aunt, and older sister are nowhere to be found. His father is off in London staging his plays. The only one home, drinking ale in the off-bounds parlour, is his irascible grandfather, from whom Hamnet has been warned to keep his distance.

As in her earlier novels, O'Farrell seeds her tale with dark forebodings. Agnes, off tending her bees during Hamnet's frantic search, will come to rue her absence that day:

Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicentre, from which everything flows out, to which everything returns. This moment is the absent mother's: the boy, the empty house, the deserted yard, the unheard cry ... It will lie at her very core, for the rest of her life.

Hamnet vividly captures the life-changing intensity of maternity in its myriad stages — from the pain of childbirth to the unassuagable grief of loss. Fierce emotions and lyrical prose are what we've come to expect of O'Farrell. But with this historical novel she has expanded her repertoire, enriching her narrative with atmospheric details of the sights, smells, and relentless daily toil involved in running a household in Elizabethan England — a domestic arena in which a few missing menstrual rags on washday is enough to alarm a mother of girls.

About halfway through this tour de force, there's a remarkable 10-page passage in which O'Farrell traces how the plague reached Agnes' children. It's a sequence that would stand out even in more salubrious times, but which holds particular resonance in light of the current global Covid-19 pandemic.

"For the pestilence to reach Warwicksire, England, in the summer of 1596," O'Farrell writes, "two events need to occur in the lives of two separate people, and then these people need to meet." The unwitting conduits are a master glassmaker in Murano, who in a moment of inattention burns his hands while blowing glass beads, and a cabin boy on a merchant ship, who becomes enchanted with an African monkey in Alexandria and picks up a stowaway infected flea in his red neckerchief. With the tenaciousness of a forensic viral chaser, O'Farrell charts the flea and its progeny's deadly path, through cats, rats, midshipmen, officers, glassmaker, and into the boxes of glass beads, one of which Hamnet's sister Judith excitedly unpacks when it is delivered to a Stratford seamstress who has been eagerly awaiting them for a client's fancy gown.

Unaware of the source of her children's illness, poor Agnes is left to suffer the consequences. O'Farrell writes, "There is a part of her that would like to wind up time, to gather it in like yarn. She would like to spin the wheel backwards, unmake the skein of Hamnet's death." But of course she realizes, "There will be no going back. No undoing what was laid out for them. The boy has gone and the husband will leave and she will stay and the pigs will need to be fed every day and time runs only one way."

Although more than 400 years have unspooled since Hamnet Shakespeare's death, the story O'Farrell weaves in this moving novel is timeless and ever-relevant.

Maggie O'Farrell

372 pages, Hardcover

First published March 31, 2020

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

“Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicentre, from which everything flows out, to which everything returns.”

“The moment she has feared most, the event she has thought about, mulled over, turned this way and that, rehearsed and re-rehearsed in her mind, during the dark of sleepless nights, at moments of idleness, when she is alone.”

“She grows up with a hidden, private flame inside her: it licks at her, warms her, warns her.”

*(No offense meant to my vegetarian brethren. I blame the metaphor.)

“They beg her to stop, not to touch people’s hands, to hide this odd gift. No good will come of it, her father says, standing over Agnes as she crouches by the fire, no good at all. When she reaches up to take his hand, he snatches it away. She grows up feeling wrong, out of place, too dark, too tall, too unruly, too opinionated, too silent, too strange. She grows up with the awareness that she is merely tolerated, an irritant, useless, that she does not deserve love, that she will need to change herself substantially, crush herself down if she is to be married. She grows up, too, with the memory of what it meant to be properly loved, for what you are, not what you ought to be.”

“She is rarely wrong. About anything. It's a gift or a curse, depending on who you ask.'

* Almost every page is like this: “Several streets away, the owl leaves its perch, surrendering itself to a cool draught, its wings silently breasting the air, its eyes alert. To it, the town appears as a series of rooftops, with gullies of streets in between, a place to be navigated. The massed leaves of trees present themselves as it flies, the stray wisps of smoke from idle fires. It sees the progress of the fox, a man, sleeping in the doorway of a tavern, scratching at a fleabite on his shin; it sees coneys in a cage at the back of someone’s house; horses standing in a paddock near the inn; and it sees Judith, stepping into the street.”

‘Someone who knows everything about you, before you even know it yourself. Someone who can just look at you and divine your deepest secrets, just with a glance. Someone who can tell what you are about to say – and what you might not – before you say it. It is,’ he says, ‘both a joy and a curse.’

“He has, Agnes sees, done what any father would wish to do, to exchange his child’s suffering for his own, to take his place, to offer himself up in his child’s stead so that the boy might live. She will say all this to her husband, later, after the play has ended, after the final silence has fallen, after the dead have sprung up to take their places in the line of players at the edge of the stage.”

It is to him she speaks in her disordered mind, not the trees, not the magic cross, not the patterns and markings of lichen, not even to her mother, who died while trying to give birth to a child. Please, she says to him, inside the chamber of her skull, please come back. I need you. Please. I should never have schemed to send you away. Make sure this child has safe passage; make sure it lives; make sure I survive to care for it. Let us both come through this. Please. Let me not die. Let me not end up cold and stiff in a bloodied bed.

Grief fills the room up of my absent child, Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me, Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words, Remembers me of all his gracious parts, Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form Then, have I reason to be fond of grief?

[She] refuses to give up her bed, saying it was the bed she was married in and she will not have another, so the new, grander bed is put in the room for guests.

For the pestilence to reach Warwickshire, England, in the summer of 1596, two events need to occur in the lives of two separate people, and then these people need to meet. The first is a glassmaker on the island of Murano in the principality of Venice; the second is a cabin boy on a merchant ship sailing for Alexandria on an unseasonably warm morning with an easterly wind.

It’s like a mirror, he had said. Or that they are one person split down the middle. Their two He feels again the sensation he has had all his life: that she is the other side to him, that they fit together, him and her, like two halves of a walnut. That without her he is incomplete, lost. He will carry an open wound, down his side, for the rest of his life, where she had been ripped from him. How can he live without her? He cannot. It is like asking the heart to live without the lungs, like tearing the moon out of the sky and asking the stars to do its work, like expecting the barley to grow without rain. Tears are appearing on her cheeks now, like silver seeds, as if by magic. He knows they are his, falling from his eyes on to her face, but they could just as easily be hers. They are one and the same. ‘You shall be well,’ she murmurs. He grips her fingers in anger. ‘I shall not.’ He passes his tongue over his lips, tasting salt. ‘I’ll come with you. We’ll go together.’

Then the idea strikes him. He doesn’t know why he hadn’t thought of it before. It occurs to Hamnet, as he crouches there, next to her, that it might be possible to hoodwink Death, to pull off the trick he and Judith have been playing on people since they were young: to exchange places and clothes, leading people to believe that each was the other.

The fleas that leapt from the dying rats into their striped fur crawl down into these boxes and take up residence in the rags padding the hundreds of tiny, multi-coloured millefiori beads (the same rags put there by the fellow worker of the master glassmaker; the same glassmaker who is now in Murano, where the glassworks is at a standstill, because so many of the workers are falling ill with a mysterious and virulent fever).

It is tall, cloaked in black, and in the place of a face is a hideous, featureless mask, pointed like the beak of a gigantic bird. ‘No,’ Hamnet cries, ‘get away.’ .. Then his grandmother is there, pushing him aside, apologising to the spectre, as if there is nothing out of the ordinary about it, inviting it to step into the house, to examine the patient. Hamnet takes a step backwards and another. He collides with his mother, ‘Don’t be afraid,’ she whispers. ‘It is only the physician.’ ‘The . . .?’ Hamnet stares at him, still there on the doorstep, talking with his grandmother. ‘But why is he . . .?’ Hamnet gestures to his face, his nose. ‘He wears that mask because he thinks it will protect him,’ she says. ‘From the pestilence?’ His mother nods. ‘And will it?’ His mother purses her lips, then shakes her head. ‘I don’t think so.’

The spectre is speaking without a mouth, saying he will not come in, he cannot, and they, the inhabitants, are hereby ordered not to go out, not to take to the streets, but to remain indoors until the pestilence is past.

If the plague comes to London, he can be back with them for months. The playhouses are all shut, by order of the Queen, and no one is allowed to gather in public. It is wrong to wish for plague, her mother has said, but Susanna has done this a few times under her breath, at night, after she has said her prayers. She always crosses herself afterwards. But still she wishes it. Her father home, for months, with them. She sometimes wonders if her mother secretly wishes it too.

‘Madam,’ the physician says, and again his beak swings towards them, ‘you may trust that I know much more about these matters than you do. A dried toad, applied to the abdomen for several days, has proven to have great efficacy in cases such as these.

She thinks of her garden, of her shelves of powders, potions, leaves, liquids, with incredulity, with rage. What good has any of that been? What point was there to any of it? All those years and years of tending and weeding and pruning and gathering. She would like to go outside and rip up those plants by their roots and fling them into the fire. She is a fool, an ineffectual, prideful fool. How could she ever have thought that her plants might be a match for this?

What is given may be taken away, at any time. Cruelty and devastation wait for you around corners, inside coffers, behind doors: they can leap out at you at any moment, like a thief or brigand. The trick is never to let down your guard. Never think you are safe. Never take for granted that your children’s hearts beat, that they sup milk, that they draw breath, that they walk and speak and smile and argue and play. Never for a moment forget they may be gone, snatched from you, in the blink of an eye, borne away from you like thistledown.

It is even more difficult, Agnes finds, to leave the graveyard, than it was to enter it. So many graves to walk past, so many sad and angry ghosts tugging at her skirts, touching her with their cold fingers, pulling at her, naggingly, piteously, saying, Don’t go, wait for us, don’t leave us here.

And Agnes finds she can bear anything except her child’s pain. She can bear separation, sickness, blows, birth, deprivation, hunger, unfairness, seclusion, but not this: her child, looking down at her dead twin. Her child, sobbing for her lost brother. Her child, racked with grief.

‘the place in your head. I saw it once, a long time ago, a whole country in there, a landscape. You have gone to that place and it is now more real to you than anywhere else. Nothing can keep you from it. Not even the death of your own child. I see this,’

It is also plague season again in London and the playhouses are shut. This is never said aloud. Judith notes the absence of this word during his visits.

What is the word, Judith asks her mother, for someone who was a twin but is no longer a twin?

Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can. As the ghost talks, she sees that her husband, in writing this, in taking the role of the ghost, has changed places with his son. He has taken his son’s death and made it his own; he has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place. ‘O horrible! O horrible! Most horrible!’ murmurs her husband’s ghoulish voice, recalling the agony of his death. He has, Agnes sees, done what any father would wish to do, to exchange his child’s suffering for his own, to take his place, to offer himself up in his child’s stead so that the boy might live.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

June 6, 2024

Current Issue

A Wisewoman in Stratford

January 14, 2021 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Illustration by Joanna Neborsky

Maggie O’Farrell’s moving historical novel Hamnet is a story of deep loss—the death of a child, struck down by an incomprehensibly virulent epidemic—and its impact upon a marriage that was already buckling under almost intolerable strain. The story’s surprise turn is that, though the grief-stricken wife succumbs for years to crippling depression and though the husband absconds and disappears into his work, the marriage miraculously survives, recovers, and becomes stronger. The wife and husband in question are Anne Hathaway (or Agnes, as she was named in her father’s will and as O’Farrell calls her) and William Shakespeare.

The novel begins in the provincial market town Stratford-upon-Avon, where the eleven-year-old Hamnet, the Shakespeares’ only son, is alarmed by the sudden eruption of strange symptoms on the body of his twin sister, Judith: “He stares at them. A pair of quail’s eggs, under Judith’s skin. Pale, ovoid, nestled there, as if waiting to hatch. One at her neck, one at her shoulder.” The swollen lymph nodes, or buboes—the dread signs of bubonic plague—seem to have come from nowhere, but in a tour de force of contact-tracing O’Farrell reconstructs the chain of random events and haphazard encounters that could have led the fatal bacterium Yersinia pestis to the Shakespeare house on Henley Street:

The flea that came from the Alexandrian monkey—which has, for the last week or so, been living on a rat, and before that the cook, who died near Aleppo—leaps from the boy [in Murano] to the sleeve of the master glassmaker, whereupon it makes its way up to his left ear, and it bites him there, behind the lobe.

And so it goes, on and on along trade routes by land and by sea, until it reaches Warwickshire in 1596.

To readers living in the shadow of a virus that made its way from a wet market in Hubei province to the nursing home around the corner, the story has a ghastly timeliness, though it is some consolation to note that the bubonic plague that struck Europe repeatedly from the fourteenth century onward was far more lethal than what we have been experiencing, and that, unlike Covid-19, it attacked the young and the old with equal ferocity.

O’Farrell brilliantly conveys the horror and devastation the plague brought to individual households—such as Shakespeare’s, as she imagines it—and to entire communities. There is no evidence of what actually killed Shakespeare’s son in 1596, but plague is a reasonable hypothesis. An outbreak in Stratford in 1564, the year of Shakespeare’s birth, took the lives of around a fifth of the population, and the disease recurred throughout the century with nightmarish frequency.

The surviving records of Shakespeare’s life are scanty; those of his wife still scantier. At the age of eighteen he married a woman eight years older than he, and by the time he reached twenty-one, he had fathered three children. This much is clear. And then he evidently abandoned them, leaving them in Stratford, where he was born, and heading off to the capital to write or to act or to do whatever it was that he imagined he was going to do. True, as the years passed, he returned from London from time to time, presumably to visit his wife; his eldest daughter, Susanna; the twins Judith and Hamnet; and his aging parents. And, as his wealth increased, he sent money back to Stratford, resettled his family in a very large brick-and-timber house, and made a succession of local real estate and commodity investments.

To that extent he remained connected. But it is telling that there were no more children born to Agnes and Will, and there is no evidence that the busy playwright shared his rich inner world with his wife or that he involved himself in the daily lives of his offspring.

Archival records suggest that actors who came from the provinces more typically brought their families to London and settled them there. And if the sonnets have any autobiographical truth to them, his most intense emotional and sexual interests lay outside the bounds of his marriage. Between the family in the house on Henley Street in Stratford and the poet in his rented rooms on Silver Street in London, there seems to have been an almost unbridgeable distance.

Biographers presume that Shakespeare must have rushed home in 1596 when his eleven-year-old son Hamnet fell gravely ill from unknown causes, but even that is by no means certain. The boy died in August and Stratford was a two-day ride from London, so it is possible that when word reached the playwright it was already too late. Had there been any warning signs? Did he get the news by letter? Or did someone speak some such words as are heard in a brief exchange in The Winter’s Tale : “Your son…is gone.” “How, ‘gone’?” “Is dead.”

If these words from a late play are somehow linked to what Shakespeare actually experienced in 1596, they are displaced from autobiography and absorbed into someone else’s story; this is how the terrible news reaches a character named Leontes. There was no general inhibition in this period from writing directly from personal experience; quite the contrary. When an outbreak of bubonic plague took his seven-year-old son Benjamin, Shakespeare’s friend and rival Ben Jonson gave voice in an exquisite twelve-line poem to his bitterly painful leave-taking:

Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy; My sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy. Seven years thou wert lent to me, and I thee pay, Exacted by thy fate, on the just day. O, could I lose all father now! For why Will man lament the state he should envy? To have so soon ’scaped world’s and flesh’s rage, And if no other misery, yet age? Rest in soft peace, and, asked, say, “Here doth lie Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.” For whose sake henceforth all his vows be such, As what he loves may never like too much.

It is striking that Shakespeare, as far as we know, left nothing comparable to so direct an expression of parental grief. Though this is the same author who wrote startlingly intimate poems to the young man and the dark lady and, in the words of a contemporary, circulated these “sugared sonnets among his private friends,” Shakespeare seems to have drawn an impenetrable curtain around his feelings, whatever they were, for his family.

In 1616, as he lay dying at the age of fifty-two, Shakespeare signed, in a shaky hand, a will that made many bequests, sentimental and otherwise. To his younger sister Joan he bequeathed £20 “and all my wearing apparrell,” along with the right to live in part of the house on Henley Street—the house in which she and her brother had grown up—for a nominal rent. To John Heminges, Henry Condell, and Richard Burbage, fellow actors and shareholders in the Globe Theater, he bequeathed twenty-six shillings and eightpence each to buy mourning rings, and he gave the same sum to his lifelong friend Hamnet Sadler “to buy him a ringe.” To Thomas Combe, the twenty-seven-year-old relative of a business associate, he left the sword that likely would have gone to his son Hamnet, had he lived.

These provisions—including the sum of £10 to “the poore of Stratford”—are the record of a thoughtful man who has accumulated a great deal of property to dispose of, from the “broad silver gilt” bowl in his grand house to the “barnes, stables, orchardes, gardens, landes, tenementes” that he owned throughout Stratford-upon-Avon and its surrounding villages. He was explicitly concerned to keep Thomas Quiney, the husband of his daughter Judith, from getting his hands on the money she would inherit. And he was equally explicitly concerned to settle most of his substantial estate on his elder daughter, Susanna, married to Dr. John Hall, and on her male heirs.

What is famously notable is the apparent absence of any significant bequest to his wife of thirty-four years. Various explanations have been offered, most plausibly that by custom and perhaps by law she would, as his widow, have been entitled during her lifetime to enjoy a portion of his estate. Still, a glance at comparable wills drawn up by people in Shakespeare’s milieu calls attention to what seems to be missing. From the will of his friend Henry Condell: “I give devise and bequeath all & singuler my freehold Messuages landes Tenementes and hereditamentes whatsoever…unto Elizabeth my welbeloved wife.” From the great actor Richard Burbage: “He the said Richard, did nominate and appoint his welbeloved wife Winifride Burbage, to be his sole Executrix of all his goodes and Chattelles whatsoever.” Likewise the theatrical entrepreneur Philip Henslowe: “I give and bequeath unto Agnes Henslow my loving wife, all and singuler my Landes, Tenementes, hereditamentes and Leases whatsoever.” William Bird, the lead actor in the Earl of Pembroke’s Men: “All other of my goods and chattells whatsoever…I give and bequeath unto my dearly beloved wiefe Marie Bird.” And the actor Thomas Downton, also of Pembroke’s Men: “I do make & Constitvte Iayne my welbeloved & Constant wife my sole Exectatrixe of all my personall Estate.” The list could go on.

The sense of something missing is heightened rather than relieved by a single line evidently inserted, after the document was already drawn up, into Shakespeare’s will: “I gyve unto my wief my second best bed with the furniture.” That’s it. No “loving,” no “dearly beloved,” no “well-beloved and constant,” let alone any hint of the sentiment that led his friend John Heminges to direct that he be buried as near as possible “to my loueinge wife Rebecca.” When Shakespeare contemplated his final resting place, he wanted only to lie undisturbed: “Blessed be the man that spares these stones, And cursed be he that moves my bones.”

Maggie O’Farrell constructs a very different story from the unhappy marriage suggested, to me at least, by these scattered archival traces. To be sure, in her telling, the absent father does not return to Stratford in time to witness the terminal illness of Hamnet. He arrives in time only for the laying out of the corpse and the bleak funeral. Then, to the intense distress of his wife and muttering something inadequate about his theater company, his season, and his preparation, he soon leaves again for London. But that apparent abandonment is folded into what O’Farrell imagines as a story of deep, enduring love.

Though she is in a distinct minority, O’Farrell is not the first to imagine it so. Already in the nineteenth century some biographers suggested that the best bed would have been reserved for visitors and that the second-best bed must have had sentimental value. Hence, in Hamnet , Susanna takes over some of the household tasks from her grieving mother and, at her father’s bidding, buys new furniture for the house, but Agnes “refuses to give up her bed, saying it was the bed she was married in and she will not have another, so the new, grander bed is put in the room for guests.”

As for the absence from the will of terms of endearment, these are mere conventions, and the most eloquent writer the world has ever known would hardly have needed or welcomed recourse to such trite phrases. The deepest emotional bonds may be precisely those that are literally inexpressible. Within his own family O’Farrell’s Shakespeare—who is never referred to in the novel by name but only as “he” or “her husband” or “the father” and the like—is a man of conspicuously few words. Even his courtship of Agnes, as O’Farrell depicts it, is a string of monosyllables and silences: “‘I…’ he begins, without any idea where that sentence will go, what he wants to say. ‘Do you…’”

As O’Farrell acknowledges, her vision of the Shakespeare marriage is indebted to a 2007 book by Germaine Greer, Shakespeare’s Wife. In Greer’s account Agnes Hathaway Shakespeare was an impressive person who has been dismissed, belittled, and slandered by centuries of misogynistic male historians and critics. “The Shakespeare wallahs”—among whom, I regret to say, I prominently figure for Greer—

have succeeded in creating a Bard in their own likeness, that is to say, incapable of relating to women, and have then vilified the one woman who remained true to him all his life, in order to exonerate him.

Speaking for myself, I never thought that Shakespeare was “incapable of relating to women,” only that he seems to have been incapable of relating to his wife. And I have never been inclined to vilify Agnes or to blame her in any way for her husband’s neglect or aversion.

With considerable energy and resourcefulness, Greer combs the surviving records for signs that Agnes was an accomplished and steadfastly loyal wife. Shakespeare scholars have not, so far as I know, embraced her suggestion that Agnes was responsible for the creation of the First Folio or that she may have written a still-undiscovered will leaving money “in trust to be spent on further publishing of her husband’s work,” but O’Farrell, for one, has been inspired by Greer’s effort to imagine a wife more substantial than the one James Joyce described as a “boldfaced Stratford wench who tumbles in a cornfield a lover younger than herself.” And the result is a satisfying and engaging novel that conjures up the life of a strong, vulnerable, lonely, and fiercely independent woman.

O’Farrell does Greer one better by depicting Agnes as what the Renaissance would have called a “wisewoman,” that is, a healer with special powers. Those powers derive for the most part from a deep understanding of the medicinal properties of plants, but there is something uncanny about what she can do. The first time Agnes and Shakespeare meet—at the country farm where the teenage Shakespeare is tutoring her stepbrothers in Latin—Agnes takes his hand and, gripping the flesh between his thumb and forefinger, mysteriously divines his inner nature. She discovers

something she would never have expected to find in the hand of a clean-booted grammar-school boy from town…. It had layers and strata, like a landscape. There were spaces and vacancies, dense patches, underground caves, rises and descents…. She knew there was more of it than she could grasp, that it was bigger than both of them.

It is easy to forgive O’Farrell the shopworn phrase “bigger than both of them” since it gestures toward what must have seemed, to anyone capable of perceiving it, indescribably strange about Shakespeare’s inner landscape.

The magnitude of that landscape, in O’Farrell’s account, is what drew Shakespeare to Agnes but what also drove him to leave her and their three children and the rest of his family, including his parents, and head off on his own to London. As the novel depicts them, Shakespeare’s mother was narrowly conventional and his father, a glover, was a drunken, irascible brute. To escape from them was a necessity. But the budding playwright wanted his beloved Agnes to join him. It was she, in O’Farrell’s reckoning, who always found a reason to delay: “Until spring comes. Until the heat of summer is over. When the winds of autumn are past. When the snow has melted.” Her motive was to preserve the lives of their precious children, to guard them from the hazards of the disease-ridden city. To this end she was willing to subordinate her deep love for her husband. And it is here, in her predominating maternal solicitude, that the novel finds its real life.

For disease and death haunted not only the crowded cities of Tudor England but also its country towns and leafy rural settlements. Given the general state of Renaissance medical knowledge, a sick person stood a better chance with the plant-based cures of a wisewoman such as O’Farrell’s Agnes than with the hideous cuppings and purges of the best Padua-trained physician. Little Hamnet, frightened by the sudden illness of his twin sister, is right to be desperately seeking his mother. But she is out in the fields, more than a mile away, collecting herbs for her healing practice. By the time she returns home, the symptoms on the little girl’s body of bubonic plague are unmistakable, and with every passing moment they are getting worse.

Narrating severe illness is for O’Farrell a personal specialty. In her 2017 memoir I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death , she describes a childhood illness that left her bedridden for a year and from which she was not expected to recover, and, still more harrowing, she depicts in excruciating, searing detail her infant daughter’s immune-system disorder:

Her skin is bubbling and blistering, each breath a struggling symphony of whistles and wheezes. Her face, under the scarlet hives, under the grotesque swelling, is ghastly white.

I think: she cannot die, not now, not here. I think: how could I have let this happen?

O’Farrell brings this direct personal experience to bear as she imagines all of Agnes’s frantic efforts to save her daughter and her irrational but unbearable feelings of responsibility. Ultimately, as we know, it was not Judith who died but her twin brother. (Judith in historical fact lived to the age of seventy-seven, dying in 1662.) Here the novel has recourse to the occult forces that had earlier accounted for Agnes’s prescient reading of her young suitor’s hand. Hamnet silently and mysteriously wills himself to take his sister’s place in the clutches of death, leaving Judith to recover as if her mother’s herbal remedies had saved her.

The recovery only intensifies Agnes’s tormenting guilt, for she feels that she somehow failed to focus her attention adequately upon the boy, and she plunges into a grief that is not unmixed with anger at her husband for not being there when she most needed him. Her anger intensifies when, having laid his son in the ground, Shakespeare announces his intention to return to London. But even in the midst of her anger, Agnes, as O’Farrell suggests, must have understood what was impelling him to leave. “You are caught by that place, like a hooked fish,” she tells him:

“What place? You mean London?”

“No, the place in your head. I saw it once, a long time ago, a whole country in there, a landscape. You have gone to that place and it is now more real to you than anywhere else. Nothing can keep you from it. Not even the death of your own child.”

After her husband leaves, Agnes succumbs to what we would now call clinical depression. And lest we think that such depression is a novelist’s historical anachronism—that parents in the early modern period must have been hardened to the death of children, since it was so terribly common—we might consider the diary of Richard Napier, a seventeenth-century Buckinghamshire astrological physician. The historian Michael MacDonald, who deciphered Napier’s voluminous notes and analyzed them in a remarkable 1981 book called Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety, and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England , found that the physician treated numerous parents, and especially mothers, who were “ever leaden with grief” after a child’s death. As William Paulet, the Marquis of Winchester, had written in 1586, “The love of the mother is so strong, though the child be dead and laid in the grave, yet always she hath him quick in her heart.”

Such is the burden, brilliantly depicted, of O’Farrell’s Agnes. Her depression lasts for years, and, though it feels as if it could never get worse, it is intensified when she learns, to her horror, that her husband has written a play that bears her son’s name. (The names Hamnet and Hamlet in this period were interchangeable.) How, she asks herself, could he have been so callous as to exploit for mass entertainment his family’s intimate tragedy?

In the novel’s climactic scene, Agnes travels to London to confront her husband. There, in the midst of the general urban filth and confusion, she has two revelations. Her first comes when she rushes to his rooms. She does not find him there, but, crucially, she finds no sign that anyone besides the playwright has been there. This is the room of a solitary writer—no trace of a lover, male or female. On his desk there is a letter to her that he has begun but left unfinished. The second and still greater revelation comes when she pays her penny, thrusts herself amid the heaving crowd, and enters the wooden O of the Globe. There on the raised stage she sees her husband, his face made up in ghastly white, playing the part of a ghost, the ghost, as the characters around him say and the crowd repeats, of Hamlet:

To hear that name, out of the mouths of people she has never known and will never know, and used for an old dead king: Agnes cannot understand this. Why would her husband have done it?

Thoroughly disgusted, she is readying herself to leave when she is transfixed by the appearance on stage of another character, a boy, or rather a young man, with the precise mannerisms of the dead Hamnet—“walking with her son’s gait, talking in her son’s voice”—and at just the age he would have been, had he lived. For a moment she is utterly baffled, and then the meaning of it all comes over her: “Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can.”

To perform this extraordinary feat, she suddenly understands, her husband, in taking on the role of the ghost, has taken his child’s death and made it his own: “He has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place.” The reader of the novel also knows, as Agnes cannot, that in offering himself in place of the other, Shakespeare has in effect done for his son what his son did for his gravely ill sister. What Agnes can and does know is that through the power of art her husband has redeemed himself and saved whatever he could of his lost son.

Did it actually happen this way? Almost certainly not. Was the moribund marriage saved? I doubt it. But I too am convinced that Shakespeare drew upon his grief and mourning to write the astonishing, transformative play that bears his son’s name. With her touching fiction O’Farrell has not only painted a vivid portrait of the shadowy Agnes Hathaway Shakespeare but also found a way to suggest that Hamnet was William Shakespeare’s best piece of poetry.

January 14, 2021

The Poet and the Reader: Nobel Lecture 2020

The Prophet of Maximum Productivity

The Imperial Gardener

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Stephen Greenblatt

An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art displays the extravagant Tudor taste for jewels, artworks, tapestries, and other finery.

December 22, 2022 issue

April 8, 2021 issue

June 11, 2020 issue

Pestilence & the Bard

April 8, 2021

Stephen Greenblatt is the Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard. His books include Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare and Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics . (December 2022)

V. S. Pritchett, 1900–1997

April 24, 1997 issue

‘Animal Farm’: What Orwell Really Meant

July 11, 2013 issue

The Disease of All Diseases

December 1, 1994 issue

February 1, 1963 issue

Short Reviews

June 24, 1976 issue

November 19, 2020 issue

February 11, 2021 issue

November 5, 2020 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

A Fictional Book About Shakespeare's Son Helped Me Grieve the Loss of Mine

How one writer overcame the grief of losing his son while reading Maggie O'Farrell's Hamnet.

Our editors handpick the products that we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page.

Books have seen me through the pandemic. It’s almost a cliché among bibliophiles, but each week I run across this sentiment on Twitter and Facebook, in long-distance phone chats, over brie and bottles of chardonnay in nearby Prospect Park. And then there’s the novel that sees you, almost literally, in this unprecedented year, plots mirroring the trajectory of your life, reversals of fortune identical to your own. Characters who glide off the page and sit on the edge of the bed, soothing your anxiety with whispered confidences―they complete your sentences, complete you.

Imagine my surprise when an Elizabethan odyssey became a roadmap through a year like no other.

In January I lost my 18 year old son, Owen, to sepsis; the infection swept in like a wildfire, ravaging his body and snuffing him out in under forty-eight hours. The previous week Covid-19 cases had peaked in the U.S. while violent insurrectionists had flooded into the nation’s capital. Grief–my grief–felt like a footnote to a vast malevolence, a ripple in a hurricane. The best way to mourn, I vowed, was to go off grid. I hunkered down in my Brooklyn apartment, throwing myself into a skeleton list of tasks: indulging my wife and two other teenagers with Indian take-out, double-masking at the gym, grooming the cats, hauling out garbage and recycling bins. And I read books—not only for work, but also for nourishment I craved but couldn’t quite understand. The less my mind rested, I figured, the less restlessness would surge through me, like a virus.

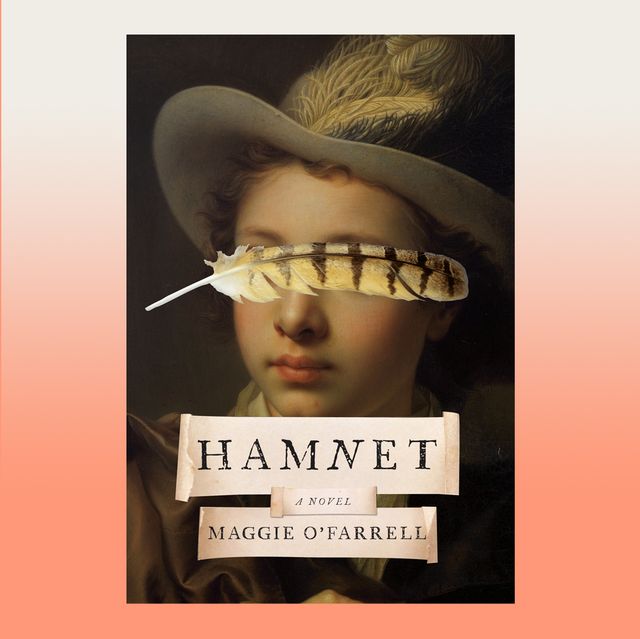

Which led me to Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet , published last year to universal acclaim and named one of 2020’s five best works of fiction by the New York Times Book Review. I was late to this stunning beauty, but in this case tardiness was a virtue: I picked up Hamnet at the moment I needed it most.

Knopf Hamnet

In precise, lavish detail, O’Farrell recreates the story of Shakespeare’s only son (also known as Hamlet), who succumbed to bubonic plague in 1596 at the age of eleven. She shifts between decades flawlessly, braiding the foreground narrative with the personal history of the enigmatic Agnes Hathaway, the Bard’s wife and mother of his three children. The abrupt subtraction of one. In O’Farrell’s telling the boy slips away fast. His father is summoned from the London stage and dashes back to the homestead in Stratford-upon-Avon but is too late. Agnes leans into her final maternal duty: she stitches Hamnet’s shroud, washes and dresses his body for burial.

“She begins at the face, at the top of him. He has a wide forehead . . . She dips the cloth, she washes, she dips again . . . The third finger of his right hand is calloused from gripping a quill. There are small pits in the skin of his stomach from when he had a spotted pox as a small child . . . Agnes looks at her son. The birdcage ribs, the interlaced fingers, the round bones of his knees, the still face, the corn-coloured hair, which has dried now, standing up from his brow, as it always does. His physical presence has always been so strong, so definite.”

I lacked Agnes’ resolve. After Owen passed away that bright cold January morning–measured in minutes, the stutter of alarms, ICU doctors yelling across a carousel of CPR–I came to his bedside. The tumult had ebbed away; there was a hush in the room. The physicians disconnected his ventilator and dimmed the monitors. His breathing tube stubbed out a few inches like a lopped umbilical cord, a smear of blood and gauze around the stoma. I touched his curls. He seemed himself, just asleep. Pink-cheeked, slack-jawed, lips a rosebud. Later his complexion would ashen, his tongue loll, slug-like, from his mouth.

Two nurses nudged me aside and asked whether they could clean him up before my wife arrived at the hospital. Fresh linens, a starched gown. I said yes, but that I wanted to wait out in the lobby, where for an hour I huddled over my cell, scrolling through contacts, veering from call to call. I must have spoken, in nervous fragments, to at least a dozen family members and friends, but I can’t say for sure. In Agnes O’Farrell captures that sense of light-headed disbelief, an instinct to connect what just happened with a larger story: there’s a global pandemic on and my son just died.

After Hamnet’s funeral, a torturous affair–Agnes is “hollowed out, her edges blurred and insubstantial”—her husband once again heeds the siren call of the theater. He can only mourn by going on with the show; he’s already mulling a new piece, a ghost haunting a disaffected Danish prince. The Bard’s daughters act out: Susanna tantrums while Judith, Hamnet’s twin, weeps in silence. Agnes hobbles around in a daze, immersed in country life, tending gardens, keeping bees in a skep. Only in the novel’s last pages when, years later, Agnes journeys to the Globe Theater to watch a performance of Hamlet , can she reconcile her tragedy with an art that transcends and sustains. The play’s the thing, with many allusions to her son. “The knowledge settles on her like a fine covering of rain,” O’Farrell writes. “Her husband has pulled off a manner of alchemy.”

We seek that alchemy from our masters, Shakespeare to O’Farrell and beyond. We seek to be seen in our most private, stripped-down moments. Recently I was having drinks with an acquaintance, a writer, in a garden tucked behind a trattoria in Greenwich Village, when he asked how many children I had, boys, girls? I fumbled the tense— I have . . .uh . . . had three boys, but now only two —before segueing into a précis of my loss. He sat across a rickety table, eyes glistening with tears, but the moment wasn’t heavy, far from it—I’d learned a thing or two about subtraction from O’Farrell. Just now I’m holding the novel in my hand, flipping it open, and finding my reflection there.

A former book editor and the author of a memoir, This Boy's Faith, Hamilton Cain is Contributing Books Editor at Oprah Daily. As a freelance journalist, he has written for O, The Oprah Magazine, Men’s Health, The Good Men Project, and The List (Edinburgh, U.K.) and was a finalist for a National Magazine Award. He is currently a member of the National Book Critics Circle and lives with his family in Brooklyn.

What Loving Feels Like to a Man

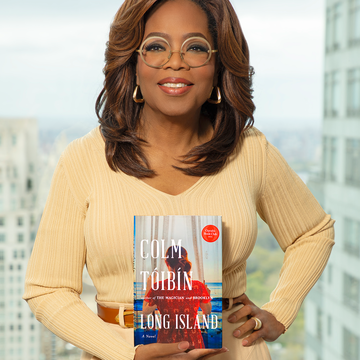

Read the First Scene of Long Island

Mother’s Day Without My Mother

Your Daughter Is Now a Mother—Who’s in Charge?

Why Every Kid Needs a Kooky Grandma

Everything You Need to Know About Colm Tóibín

All 105 Books in Oprah’s Book Club

Oprah Announces Her 105th Book Club Pick

The Award-Winning Books You’ll Actually Love

How This Styrofoam Cup Held Together a Family

How to Feel Powerful in Every Setting

clock This article was published more than 3 years ago

Maggie O’Farrell’s ‘Hamnet’ reimagines the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son

On Aug. 11, 1596, William Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet, was buried. He was 11 years old.

Almost nothing more is known about the boy’s brief life. Four centuries later, his death is a crater on the dark side of the moon. How it impacted his twin sister and his parents is impossible to gauge. No letters or diaries — if there were any — survive. The world’s greatest poet did not immortalize his lost child in verse.

Instead, we have only a few tantalizing references in Shakespeare’s plays: the laments of grieving fathers, the recurrence of twins and, of course, a tragedy called “Hamlet.” But aside from the name — a variant of Hamnet — attempts to draw comparisons between that masterpiece and the author’s son are odorous. We’re stuck, as we usually are, projecting our own sympathetic sorrow on the calamities of others.

To this unfathomable well of grief now comes the brilliant Irish writer Maggie O’Farrell with a novel called “Hamnet” told with the urgency of a whispered prayer — or curse.

Unintimidated by the presence of the Bard’s canon or the paucity of the historical record, O’Farrell creates Shakespeare before the radiance of veneration obscured everyone around him. In this book, William is simply a clever young man — not even the central character — and O’Farrell makes no effort to lard her pages with intimations of his genius or cute allusions to his plays. Instead, through the alchemy of her own vision, she has created a moving story about the way loss viciously recalibrates a marriage.

Sign up for the Book Club newsletter

The novel opens in silence that foretells doom. “Where is everyone?” little Hamnet wonders. He wanders like a ghost through the empty house and the deserted yard, calling for his grandparents, his uncles, his aunt. “He has a tendency,” O’Farrell writes, “to slip the bounds of the real, tangible world around him and enter another place.” But he’s no spectral presence yet. His twin sister, Judith, has suddenly fallen ill, and Hamnet needs to find their mother. She’ll know what to do. She’s an herbal healer, equally revered and feared in the village. “Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicenter, from which everything flows out, to which everything returns. This moment is the absent mother’s,” O’Farrell writes. “It will lie at her very core, for the rest of her life.”

Between the hours of this fateful day, the story jumps back years. We see William’s unhappy adolescence as the son of a cruel and disreputable glover. One day, while teaching Latin to bored children in a country schoolhouse, he spots a young woman gathering plants along the edge of the woods. History knows her as Anne Hathaway, but O’Farrell uses the name her father gave her in his will: Agnes. Neighbors whisper that she’s “the daughter of a dead forest witch . . . too wild for any man.”

That’s your cue, William!

Soon, he and Agnes are acting out “hot blood, hot thoughts, and hot deeds” — including the hottest sex scene ever set in an apple storeroom.

This is a richly drawn and intimate portrait of 16th-century English life set against the arrival of one devastating death. O’Farrell, always a master of timing and rhythm, uses these flashbacks of young love and early marriage to heighten the sense of dread that accumulates as Hamnet waits for his mother. None of the villagers know it yet, but bubonic plague has arrived in Warwickshire and is ravaging the Shakespeare twins, overwhelming their little bodies with bacteria. That lit fuse races through the novel toward a disaster that history has already recorded but O’Farrell renders unbearably suspenseful.

Dead center in the novel, the author momentarily arrests the story of the Shakespeare family and transports us to the Mediterranean Sea. Here, in a chapter just a dozen pages long, we get a gripping lesson in 16th-century epidemiology. Then as now, commerce and travel are the engines of disease. A glassmaker in Venice, a monkey in Alexandria, a cabin boy from the Isle of Man — they all play small but consequential roles in the intricate chain of transmission as infected fleas jump from body to body, sowing illness across Europe. It’s a fascinating and horrific demonstration of the same forces now driving a different pandemic more than 400 years later. We may have better medical technology, but our frantic missteps sound like echoes of the Renaissance. They had their physicians prescribing onion and dried toad; we have our president nattering on about light and bleach.

But O’Farrell isn’t merely delaying the inevitable tragedy at the heart of her story; she’s creating the context to help us feel its full impact on Hamnet’s parents. Agnes is a skillful woman married to a restless man whose talents are more imaginative than practical. Constrained by the demands of motherhood and the limited opportunities of the time, she must exercise her influence indirectly and stealthily. The moves she makes to keep her children healthy and her spouse happy represent the hidden sacrifices that countless women have made, without thanks or credit, to support their husbands’ ambitions.

A marriage based on secrecy is threatened in Maggie O’Farrell’s ‘This Must Be the Place’

That delicate negotiation grows far more perilous when the couple endures the death of a child. No two spouses respond to such a loss in harmony, and O’Farrell is at her most sensitive here, detailing the unspeakable anguish that strips Agnes of her confidence and propels William into the imaginary world of his comedies and tragedies.

The dark months and years of mourning that fall over the Shakespeare family would seem a slough of despair after the frantic efforts to save Hamnet’s life, but in O’Farrell’s telling, grieving is a harrowing journey all its own. The novel’s final scene offers a miraculous transformation — no, not a “Winter’s Tale” resurrection — but the revelation that love can sometimes spark.

Ron Charles writes about books for The Washington Post and hosts TotallyHipVideoBookReview.com .

By Maggie O’Farrell

Knopf. 305 pp. $26.95

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2020

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

National Book Critics Circle Winner

by Maggie O'Farrell ‧ RELEASE DATE: July 21, 2020

A gripping drama of the conflict between love and destiny.

Imagining the life of the family Shakespeare left behind in Stratford makes an intriguing change of pace for a veteran storyteller.

While O’Farrell eschews the sort of buried-secrets plots that drive the propulsive narratives of such previous novels as Instructions for a Heatwave (2013), her gifts for full-bodied characterization and sensitive rendering of intricate family bonds are on full display. She opens with 11-year-old Hamnet anxiously hovering over his twin sister, Judith, who has a mysterious fever and ominous swellings. When Hamnet asks his grandfather where his mother is, the old man strikes him, and as the novel moves through the characters’ memories, we see the role John Shakespeare’s brutality played in son Will’s departure for London. The central figure in this drama is Shakespeare’s wife, Agnes, better known to history as Anne, recipient of the infamous second-best-bed bequest in his will. O’Farrell chooses an alternate name—spelling was not uniform in Elizabethan times—and depicts Agnes as a woman whose profound engagement with the natural world drew young Will to her from their first meeting. The daughter of a reputed sorceress, Agnes has a mysterious gift: She can read people’s natures and foresee their futures with a single touch. She sees the abilities within Will that are being smothered as a reluctant Latin tutor and inept participant in his father’s glove trade, and it is Agnes who deftly maneuvers John into sending him away. She believes she will join Will soon, but Judith’s frailty forestalls this. O’Farrell draws us into Agnes’ mixed emotions as the years go by and she sees Will on his increasingly infrequent visits “inhabiting it—that life he was meant to live, that work he was intended to do.” Hamnet’s death—bitterly ironic, as he was always the stronger twin—drives the couple farther apart, and news of a new play called Hamlet sends Agnes to London in a rage. O’Farrell’s complex, moving finale shows her watching the performance and honoring her husband’s ability to turn their grief into art.

Pub Date: July 21, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-525-65760-6

Page Count: 320

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: June 15, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: July 1, 2020

LITERARY FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

Share your opinion of this book

More by Maggie O'Farrell

BOOK REVIEW

by Maggie O'Farrell

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

BOOK TO SCREEN

LONG ISLAND

by Colm Tóibín ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 7, 2024

A moving portrait of rueful middle age and the failure to connect.

An acclaimed novelist revisits the central characters of his best-known work.

At the end of Brooklyn (2009), Eilis Lacey departed Ireland for the second and final time—headed back to New York and the Italian American husband she had secretly married after first traveling there for work. In her hometown of Enniscorthy, she left behind Jim Farrell, a young man she’d fallen in love with during her visit, and the inevitable gossip about her conduct. Tóibín’s 11th novel introduces readers to Eilis 20 years later, in 1976, still married to Tony Fiorello and living in the titular suburbia with their two teenage children. But Eilis’ seemingly placid existence is disturbed when a stranger confronts her, accusing Tony of having an affair with his wife—now pregnant—and threatening to leave the baby on their doorstep. “She’d known men like this in Ireland,” Tóibín writes. “Should one of them discover that their wife had been unfaithful and was pregnant as a result, they would not have the baby in the house.” This shock sends Eilis back to Enniscorthy for a visit—or perhaps a longer stay. (Eilis’ motives are as inscrutable as ever, even to herself.) She finds the never-married Jim managing his late father’s pub; unbeknownst to Eilis (and the town), he’s become involved with her widowed friend Nancy, who struggles to maintain the family chip shop. Eilis herself appears different to her old friends: “Something had happened to her in America,” Nancy concludes. Although the novel begins with a soap-operatic confrontation—and ends with a dramatic denouement, as Eilis’ fate is determined in a plot twist worthy of Edith Wharton—the author is a master of quiet, restrained prose, calmly observing the mores and mindsets of provincial Ireland, not much changed from the 1950s.

Pub Date: May 7, 2024

ISBN: 9781476785110

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Scribner

Review Posted Online: Feb. 3, 2024

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2024

LITERARY FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION

More by Colm Tóibín

by Colm Tóibín

edited by Colm Tóibín

SEEN & HEARD

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, ft professional, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

- Make and share highlights

- FT Workspace

- Markets data widget

- Subscription Manager

- Workflow integrations

- Occasional readers go free

- Volume discount

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Missing Thread; Table for Two; Cinema Speculation – reviews

A female-focused history of the classical world by ‘the next Mary Beard’; Amor Towles’s elegant collection of short stories; and Quentin Tarantino’s provocative film criticism

The Missing Thread

Daisy Dunn W&N, £25 , pp435

The title of “the next Mary Beard” is one bandied around with wearying predictability, but judging by this terrifically readable and deeply researched new book, Daisy Dunn is in prime position to take up such a mantle. She tells the story of how the classical world, so long discussed through the prism of the men who lived in it, should be reassessed through its influential and fascinating female inhabitants instead. By turns authoritative, witty and revelatory, The Missing Thread feels like a book for our times and for all time.

Table for Two

Amor Towles Hutchinson Heinemann, £18.99, pp480

Aficionados of Amor Towles ’s carefully crafted fiction will be thrilled by this latest collection of elegantly presented short stories along with a novella. The tales focus on vignettes of turn-of-millennium New York life, while the longer Eve in Hollywood sees the reappearance of Rules of Civility ’s inimitable Evelyn Ross in 1930s Los Angeles. The recent adaptation of A Gentleman in Moscow has raised the author’s profile to new heights, and long-standing admirers and new readers alike will take great delight in this entertaining collection. A new novel soon please, Mr Towles.

Cinema Speculation

Quentin Tarantino W&N, £10.99, pp400 (paperback)

Quentin Tarantino has taken delight in polarising opinion throughout his career. For this mash-up of memoir, film criticism and something uncategorisable but unmistakably Tarantinoesque, he brings together his cinematic bugbears and enthusiasms. Discussing everything from the structural flaws of Taxi Driver to his fascination with Deliverance , this is unashamedly opinionated, provocative, often exasperating but never less than diverting writing. Should he really give up directing after his next picture, a career in film journalism surely awaits.

To order The Missing Thread , Table for Two or Cinema Speculation go to guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

- The Observer

- History books

- Short stories

- Quentin Tarantino

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Tits Up’ Aims to Show Breasts a Respect Long Overdue

The sociologist Sarah Thornton visits strip clubs, milk banks and cosmetic surgeons with the goal of shoring up appreciation for women’s breasts.

- Share full article

By Lucinda Rosenfeld

Lucinda Rosenfeld, a novelist and essayist, is the author of five books, including “Class.”

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

TITS UP: What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us About Breasts, by Sarah Thornton

It’s a testament to the sociologist Sarah Thornton’s central thesis — women’s breasts are unjustly sexualized, trivialized and condescended to — that I expected her new book, “Tits Up,” to be a light read. In fact, her impassioned polemic makes a convincing case that the derogatory way Western culture views tits (Thornton contrasts her chosen slang with the relatively “silly” and “foolish” boobs ) helps perpetuate the patriarchy.

Breasts have been seen as “visible obstacles to equality, associated with nature and nurture rather than reason and power,” Thornton announces upfront. Over five, sometimes fascinating, sometimes frustrating chapters, each examining mammaries in a different context, “Tits Up” asks readers to reimagine the bosom, no matter its size and shape, as a site of empowerment and even divinity.

The author of a similarly discursive survey of the early 2000s art world , Thornton arrived at her new topic not entirely by choice. In 2018, after one too many stressful biopsies, she underwent a double mastectomy. But neither a fraught origin story nor Thornton’s argument that women are unfairly restrained by their mammalian status prevents “Tits Up” from being funny, too. Keen to make peace with her larger than expected implants — Thornton had requested more modest “lesbian yoga boobs” — she names her new pair Ernie and Bert.

The three of them soon hit the research road.

First stop: the Condor, a historic strip club in San Francisco, where Thornton interviews a racially and size-diverse group of strippers, who paint a relatively sunny portrait of a notoriously sleazy industry. Additional interviews with feminist sex activists and performance artists such as Annie Sprinkle — if you’re in need of a good laugh, Google “ Bosom Ballet ” — lead Thornton to conclude that, even when breasts are targets of overt objectification (after all, most patrons of topless bars are male), they might be thought of less as “sex toys” than as “salaried assistants.”

Feminists have been fighting about what’s now known as “sex work” for as long as feminism has been around. Thornton comes down squarely on the side of the workers. But she goes further than that. “I think the most fundamental issue inhibiting women’s autonomy — our right to choose what we do with our bodies — is the state’s policing of sex work,” she writes. “If some women can’t sell their bodies, then none of us actually own our bodies.” Reading these lines, I admit my first thought was, Huh? Should women’s ability to prostitute themselves really be the measure of our liberation?

But the chapter that follows, a cri de coeur on behalf of breastfeeding and the legacy of communal “allomothers” — women who nurse children who are not their own — seems to make a counterargument in favor of configuring breasts outside both capitalism and sexuality. After interviewing the women who run, provide and reap the benefits of a San Jose-based nonprofit milk “reservoir” (Thornton prefers the term to “bank”), she writes, “In a capitalist society where women’s breasts are commodified like no other body part, here their jugs are the key players in an economy that is not about money.”

It’s to Thornton’s credit that, her polemical tone notwithstanding, she is open-minded enough to entertain paradoxes. (And entertain she does.) While she despairs at the discouraging lingo that surrounds nursing — “milk letdown” comes in for particular condemnation — she admits to having felt conflicted while breastfeeding her own, now grown, children, insofar as the practice evoked for her the enervating specter of the selfless mother.

Semantics are at the heart of “Tits Up,” as Thornton rightly notes that the words we use inform the ideologies we subscribe to. But, again, the contradictions mount. Even as Thornton employs trans-activist-approved jargon such as “AMAB,” for assigned male at birth, and insists that both men and women have breasts, she draws the line at the term “chest feeding,” pointing out that “the expression obfuscates the highly gendered history of this maternal labor.”

Is it highly gendered or highly sexed? Either women’s lives are too much hampered by the fetishization and fear of their anatomy, or — paging Judith Butler — sexual difference is socially constructed and therefore, at least in theory, susceptible to change. I don’t quite see how these arguments can coexist.

Another research trip lands Thornton in the studio of a mass-market bra designer, where she decides that, although the brassiere is an impressive feat of engineering designed to make women feel safe, it’s past time we stopped hiding our nipples. In the operating room of a high-end plastic surgeon who performs augmentations, lifts and reductions, she concludes that breast alterations are not simply capitulations to normative beauty standards. Instead, such procedures might be understood in terms of female agency — as gestures that exist outside the logic of resistance or submission. Finally, she attends a neo-pagan retreat for women in the California redwoods, where she reflects on how alternative spiritual practices provide more space for aging female bodies — the kind of woman once referred to as a “crone” — and fantasizes half in jest about a world where saggy breasts are regarded as “sagacious.”

Drawing on her art history background, Thornton also leads us on an enlightening tour of female deities and their bosoms, including the Greek goddess of the hunt, Artemis (frequently depicted with multiple breasts); a Buddhist goddess of compassion, Guanyin (always portrayed as pancake flat); and the Virgin Mary, who, in portraits of her nursing baby Jesus, often appears to have only one boob. (Go figure.)

What does it all add up to? “Women have no federal right to breastfeed or to obtain an abortion, but we have the right to fake tits,” Thornton writes, noting that since 1998 health insurance companies have been required to pay for breast implants following medically necessary mastectomies. But what would a “federal right to breastfeed” look like, anyway? This declaration is among countless thought-provoking ones in this deceptively trenchant if inconsistently argued treatise. In any event, I eagerly await the sequel: “Asses Down”?

TITS UP : What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us About Breasts | By Sarah Thornton | Norton | 307 pp. | $28.99

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

An assault led to Chanel Miller’s best seller, “Know My Name,” but she had wanted to write children’s books since the second grade. She’s done that now with “Magnolia Wu Unfolds It All.”

When Reese Witherspoon is making selections for her book club , she wants books by women, with women at the center of the action who save themselves.

The Nobel Prize-winning author Alice Munro, who died on May 14 , specialized in exacting short stories that were novelistic in scope , spanning decades with intimacy and precision.

“The Light Eaters,” a new book by Zoë Schlanger, looks at how plants sense the world and the agency they have in their own lives.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

I n 1596, William Shakespeare's 11-year-old son Hamnet died in Stratford-upon-Avon. Four or so years later, Shakespeare wrote the play considered by many to be his greatest work, giving its ...

In 1596, Hamnet, just 11 years old, died. (The cause of death is unknown; O'Farrell imagines, plausibly, that it was plague.) By then William Shakespeare was an established playwright, living in ...

O'Farrell's last book, I Am, I Am, I Am (2018), was a nonfiction account of her own unpredictable life, filtered through 17 dramatic, near-death experiences, from her hair-raising childhood ...

Nominee for Best Historical Fiction (2020) Drawing on Maggie O'Farrell's long-term fascination with the little-known story behind Shakespeare's most enigmatic play, Hamnet is a luminous portrait of a marriage, at its heart the loss of a beloved child. Warwickshire in the 1580s. Agnes is a woman as feared as she is sought after for her unusual ...

The novel begins in 1596, with Hamnet discovering his beloved twin sister Judith has taken sick and searching for someone to help her, not realising it is his own illness that will be beyond cure.

A Wisewoman in Stratford. Hamnet imagines a literary legacy for Shakespeare's wife and son. An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art displays the extravagant Tudor taste for jewels, artworks, tapestries, and other finery. An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art displays the extravagant Tudor taste for jewels, artworks ...

Maggie O'Farrell's "Hamnet," one of last year's most widely acclaimed novels, imagines the life of William Shakespeare, his wife, Anne (or Agnes) Hathaway, and the couple's son Hamnet ...

Which led me to Maggie O'Farrell's Hamnet, published last year to universal acclaim and named one of 2020's five best works of fiction by the New York Times Book Review. I was late to this stunning beauty, but in this case tardiness was a virtue: I picked up Hamnet at the moment I needed it most. Knopf Hamnet.

Named one of the 10 best books of 2020 by The New York Times Book Review, "Hamnet" is incredibly engrossing and sometimes playful, even though it is about the death of a child. It reduces many ...

Review by Ron Charles. July 21, 2020 at 8:00 a.m. EDT. On Aug. 11, 1596, William Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet, was buried. He was 11 years old. Almost nothing more is known about the boy's ...

National Book Critics Circle Winner. Imagining the life of the family Shakespeare left behind in Stratford makes an intriguing change of pace for a veteran storyteller. While O'Farrell eschews the sort of buried-secrets plots that drive the propulsive narratives of such previous novels as Instructions for a Heatwave (2013), her gifts for full ...

The plot follows the history as it must: Hamnet dies tragically to be curiously reborn in Hamlet; the scene shifts to the Globe theatre, Cabey steps out as the Prince and thrilling use is made of ...

Book review: Hamnet, by Maggie O'Farrell. Maggie O'Farrell's bravura new novel opens with a terse "Historical Note", which, given that it is set in the Elizabethan period, probably ...

Hamnet doesn't feature fully until after the interval. But there are riches too in translating the story to stage. Chakrabarti's play is in constant conversation with Shakespeare's dramas.

HAMNET: A Novel of the Plague, by Maggie O'Farrell.(Vintage, 320 pp., $16.95.) At the center of this National Book Critics Circle Award winner — one of the Book Review's 10 Best Books of ...