Advertisement

Unintentional Child Neglect: Literature Review and Observational Study

- Original Paper

- Published: 15 November 2014

- Volume 86 , pages 253–259, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Emily Friedman 1 &

- Stephen B. Billick 2

4959 Accesses

25 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Child abuse is a problem that affects over six million children in the United States each year. Child neglect accounts for 78 % of those cases. Despite this, the issue of child neglect is still not well understood, partially because child neglect does not have a consistent, universally accepted definition. Some researchers consider child neglect and child abuse to be one in the same, while other researchers consider them to be conceptually different. Factors that make child neglect difficult to define include: (1) Cultural differences; motives must be taken into account because parents may believe they are acting in the child’s best interests based on cultural beliefs (2) the fact that the effect of child abuse is not always immediately visible; the effects of emotional neglect specifically may not be apparent until later in the child’s development, and (3) the large spectrum of actions that fall under the category of child abuse. Some of the risk factors for increased child neglect and maltreatment have been identified. These risk factors include socioeconomic status, education level, family composition, and the presence of dysfunction family characteristics. Studies have found that children from poorer families and children of less educated parents are more likely to sustain fatal unintentional injuries than children of wealthier, better educated parents. Studies have also found that children living with adults unrelated to them are at increased risk for unintentional injuries and maltreatment. Dysfunctional family characteristics may even be more indicative of child neglect. Parental alcohol or drug abuse, parental personal history of neglect, and parental stress greatly increase the odds of neglect. Parental depression doubles the odds of child neglect. However, more research needs to be done to better understand these risk factors and to identify others. Having a clearer understanding of the risk factors could lead to prevention and treatment, as it would allow for health care personnel to screen for high-risk children and intervene before it is too late. Screening could also be done in the schools and organized after school activities. Parenting classes have been shown to be an effective intervention strategy by decreasing parental stress and potential for abuse, but there has been limited research done on this approach. Parenting classes can be part of the corrective actions for parents found to be neglectful or abusive, but parenting classes may also be useful as a preventative measure, being taught in schools or readily available in higher-risk communities. More research has to be done to better define child abuse and neglect so that it can be effectively addressed and treated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Heed Neglect, Disrupt Child Maltreatment: a Call to Action for Researchers

Health implications of maltreated children exposed to domestic violence

Child Neglect

Beiki O, Karimi N, Mohammadi R: Parental education level and injury incidence and mortality among foreign-born children: A cohort study with 46 years follow-up. Journal of Injury and Violence Research 6(1):37–43, 2014.

PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Child Abuse in America. National Child Abuse Statistics. Retrieved 6 May 2014. From http://www.childhelp.org/pages/statistics .

Erickson MF, Egeland B: Child Neglect. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Jenny C, Reid TA (Eds) APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment, 2nd edn., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc, 2002.

Google Scholar

Gorzka PA. Homeless parents: Parenting education to prevent abusive behaviors. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric nursing 12(3):101–109, 1999.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Heimpel D: 2013 New Study points to Danger of Child Neglect. The Chronicle of Social Change. Retrived 6 May 2014. From https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/news/new-study-points-to-danger-of-child-neglect/3934 .

Karageorge K, Kendall R: The role of professional child care providers in preventing and responding to child abuse and neglect. Child abuse and neglect user manual series. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children’s Bureau, 2008.

Lee SJ: Paternal and household characteristics associated with child neglect and child protective services involvement. Journal of Social Services Research 39(2):171–187, 2013.

Article Google Scholar

Mooney H: Less advantaged children are 17 times more at risk of unintentional or violent death than more advantaged peers. British Medical Journal 2101 341:c6795, 2010.

Putnam-Hornstein E, Cleves MA, Licht R, Needell B: Risk of fatal injury in children following abuse allegations: Evidence from a prospective, population based study. American Journal of Public Health 103(10):e39–e44, 2013.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Schnitzer PG, Covington TM, Kruse RL: Assessment of caregiver responsibility in unintentional child injury deaths: Challenges for injury prevention. British Medical Journal 17(Suppl 1):i45–i54, 2011.

Schnitzer PG, Ewigman BG: Household composition and fatal unintentional injuries related to child maltreatment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 40(1):91–97, 2008.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tardy C: 2012. The effects of unintentional child abuse (Neglect). Single parent advocate: Coping (Self-Care)—Parents, Parenting. Retrieved 6 May 2014. From http://singleparentadvocate.org/get-advice/item/the-effects-of-unintentional-child-abuse .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, 19107, USA

Emily Friedman

NYU School of Medicine, 901 5th Avenue, New York, NY, 10021, USA

Stephen B. Billick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emily Friedman .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Friedman, E., Billick, S.B. Unintentional Child Neglect: Literature Review and Observational Study. Psychiatr Q 86 , 253–259 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9328-0

Download citation

Published : 15 November 2014

Issue Date : June 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9328-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child neglect

- Unintentional injuries

- Child abuse

- Maltreatment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Screening Children for Abuse and Neglect: A Review of the Literature

Affiliation.

- 1 Author Affiliations: College of Nursing, East Tennessee State University.

- PMID: 28212197

- DOI: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000136

Child abuse and neglect occur in epidemic numbers in the United States and around the world, resulting in major physical and mental health consequences for abused children in the present and future. A vast amount of information is available on the signs and symptoms and short- and long-term consequences of abuse. A limited number of instruments have been empirically developed to screen for child abuse, with most focused on physical abuse in the context of the emergency department, which have been found to be minimally effective and lacking rigor. This literature review focuses on physical, sexual, and psychological abuse and neglect, occurring in one or multiple forms (polyabuse). A systematic, in-depth analysis of the literature was conducted. This literature review provides information for identifying children who have been abused and neglected but exposes the need for a comprehensive screening instrument or protocol that will capture all forms of child abuse and neglect. Screening needs to be succinct, user-friendly, and amenable for use with children at every point of care in the healthcare system.

Publication types

- Child Abuse / diagnosis*

- Mass Screening / instrumentation*

- Mass Screening / methods*

- Physical Examination

Preventing Child Abuse

A website that aims for stopping Child Abuse around the world

Literature Review

Impact Of Child Abuse On Young Adults Mohamed Kharma, Edwar Amean, Nusaibh Talabah, Haifa Ali ENGL 21003 Instructor: Pamela Stemberg The City College of New York

Child abuse is a significant global problem that happens in all cultural, ethnic, and income groups. Child abuse can be in the form of physical, sexual, emotional or just neglect in providing the needs of the child. These factors can leave the child with severe long – lasting psychological damage. Abuse may also cause serious injury to the child and may even result in death. This resource guide examines the available data of child abuse and neglect. We will describe exactly what child abuse is in a broad sense, as well as specific types of abuse and neglect. The research aims to show which population of children are most likely to be abused and neglected as well as which adults are likely to be abusers when they become parents. Also, the goal of this research is to explain what are the reasons that lead for the abuse by exploring and going over each and all the types of child abuse.

Introduction

Child abuse is a major topic in the world. Child abuse is one of the most prevalent things in our society, but not for everyone. Child abuse is divided into four types of abuse.The four kinds of child abuse; physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect; however, all of them are different from each other. There are many causes of child abuse. The effect it has on a child can be permanent, but other times child abuse may have life lasting consequences. These abuses have different forms that both of the child and the adult show signs and symptoms of. The acts of the abusers play a significant role in the long-term implications for the abused children. Therefore, parents have a significant responsibility towards their children. According to Child Welfare, households that suffer from alcoholism, drug abuse and anger issues have higher child abuse incidents compared to other households. Child abuse can lead to injury on both the short and long term or even death. Some kids may be simply be unaware of being victims of child abuse just because they got used to it. Physical abuse involves a child’s unintentional harm, such as burning, beating, or breaking bones. Verbal abuse involves harming a child by threatening physical or sexual acts or belittling them.

Childhood abuse, physical abuse, emotional maltreatment, neglect, sexual abuse, violence, emotional abuse, mental disorders

Methodology

For the literature review on the impact of child abuse on young adults each group member began their research for four articles on their subtopic. It was not difficult for each group member to find the articles for their subtopics, however when we limited the time frame, many of the articles had to be replaced. The publication date played a major role in the findings of the articles, because we would either find very old articles or a review of a prior literature review. As a group, we discussed what is child abuse and we divided the topics. Eventually we came to an agreement to use keywords such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. While researching articles we targeted young adults and adolescence as our age group to speak about, due to the implications they will face after experiencing abuse as a child. As a group, we came to an agreement to separately conduct our research on our sub-topics with the limitation of articles before 2014. After selecting our articles and verifying the time frame it was published in, and if it was truly a scholarly article, we sought the approval of our professor to see if our articles fit the description of the assignment. Professor Stemberg soon verified our articles and rejected others due to the limitation of the publication date. While collecting articles for our assignment we came together with a total of sixteen articles, four from each group member from multiple sources. Firstly, we searched within the CCNY library to find our articles, however there was not many so we were forced to seek our articles from google scholar. The articles in which were searched with the key word “Neglect”, focused on parents who neglected their children whether it was with the way they dressed, or the food they eat and the impacts it had on these children growing up. Secondly, the articles in which focused on physical abuse informed us the readers on children whom were beaten and intentionally harmed physically and the impacts it had on these children growing up. Thirdly we searched for articles that informed us of emotional abuse, and those articles discussed children whom were bullied from parents or caregivers, in these articles they focused on verbal aggression, manipulation, humiliation and intimidation. These articles focused on how emotional abuse can impact a child’s life as he/she grows older. Lastly, the articles in which was focusing on sexual abuse, informed us of the types of sexual abuse being contact and non-contact and, the implications a child who faced sexual abuse experiences. Surely after a considerable amount of reading and analyzation of these articles we began our literature review. Although we directly resorted to CCNY library via psycinfo and Academic search complete, there were many limitations such as the inability to view the full text and the publication date being earlier than 2014. Therefore we also used google scholars and narrowed our search extensively. While using google scholar it was much easier, because we were able to set the limitation to the publication date. While researching using google scholar it was much easier because, we were able to find exactly what we needed. Nonetheless we collected all of our articles and began our literature review.

Sexual Abuse

There are many forms of child abuse that an individual can face, such as neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse. Child abuse is most commonly known to occur from a parent, or caregiver, however, it can also come from individuals whom the child is not familiar with. Child abuse is when pain or harm is inflicted upon a child intentionally. Throughout this section, you will be informed of the psychological and interpersonal impacts of child sexual abuse on young adults.

According to the National Society for the prevention of child sexual abuse of cruelty to children, there are two different types of child sexual abuse which are called contact abuse and non-contact abuse. Contact abuse involves any activities where the predator forces physical contact upon the child, which includes touching the child’s body or making a child take off their clothes and touch another individual’s gentiles. It also includes rape or penetration. Nonetheless non-contact abuse involves activities in which the abuser persuades the child to perform sexual acts over the internet (NSPCC,2009, P.2) Child sexual abuse increases the risk for several mental illnesses, such as psychosis, anxiety, substance abuse, and personality disorders. However, the most common symptom in a victim of child sexual abuse is post-traumatic stress disorder (Ronser et al, Trials 2014, 15:195). Furthermore it was indicates that comorbidity is secondary to PTSD which often develops in adolescence and early adulthood. The victim plays a major role in the trauma-related outcomes, it depends on how the child and/or victim fights the trauma. A victim of child abuse should seek help, or be treated at an earlier stage because victims tend to develop a suicidal or self-injurious coping mechanism (Ronser et al, Trials 2014, 15:195). Survivors of child sexual abuse often experience difficulties in emotion regulation, behavior and emotion management techniques (Ronser et al, Trials 2014, 15:195). In this study, the participants that were tested on and targeted were adolescents and young adults who are diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder after experiences abuse after the age of three. Participants who were in the study must be on stable medication, moreover living in a safe and stable home, and informed consent (Ronser et al, Trials 2014, 15:195). Participants had a set of rules that must be complied with, such as the participants were needed to attend five sessions within four weeks, also participants were required to learn how to tolerate and control intensive trauma-related emotions without acting out, participants also had to attend fifteen sessions of cognitive processing therapy, and lastly teach the victims how to minimize future victimization and prevent the choice of abusive partners (Ronser et al, Trials 2014, 15:195). Although the article failed to publish their results after their trials it is known that victims of CSA suffer from psychological illnesses due to the trauma they have been through.

There are many victims of child sexual abuse whom may never speak their story, and there are victims who speak their story in which it could be formally and informally, however many victims delay telling their stories until about five years after the abuse has happened. This could make it difficult for researchers to understand exactly what happened, and how the victim is coping with the trauma they have faced. According to the article individuals who disclose childhood sexual abuse decide to disclose or not to in their adulthood. It is believed that the transition into adulthood opens up the door for new obstacles, and victims of abuse are exposed to new people and a new environment who are not aware of the trauma they have experienced (Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014). Many individuals fear if they speak their story it will taint the new environment they were exposed to. Victims fear if they speak about the abuse the endured, they will have to face negative responses from the community which they are in. There are adult survivors who are fully aware of past abuse, however they choose to not disclose it, theses adults refer to shame, guilt, self-blame, and anxiety as their barriers as to why they refuse to disclose the abuse they have faced (Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014)). When speaking of CSA many survivors indicated they are fearful of other reactions to their story. Victims are often

fearful of not being believed or being emotionally hurt after disclosing their abuse. Other survivors indicated that if they speak about what has happened to them, it may ruin their present lives, and what they have achieved in their life including their partners, and children (Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014)). Things could be worse for individuals who were abused by family members because they are unable to separate themselves from these individuals, and if they disclose about their abuse they may jeopardize their relationship with other members of the family and are fearful that they will be targeted as a liar. Victims of child abuse who were abused by a family member fear they will have to face abandonment by people they cherish due to the members of the family siding with the perpetrator (Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014)). One may find that victims often only speak out once due to the reaction they received, negative responses causes the victim to further disclose their story, and to isolate themselves, and find it difficult to trust people. However, if the victim received their negative response from a professional, they tend to seek out other professionals until they receive a positive response (Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014)). Child sexual abuse is linked to many long-term consequences, including depression, suicidal ideations, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as physical health problems and at-risk sexual behaviors (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014). Post-traumatic stress disorder appears to be one of the most frequent symptoms in a victim who has experienced sexual abuse. It was discovered that post-traumatic stress disorder is diagnosed in 57 % of teenagers who experienced sexual trauma (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014). However, many factors are measured when speaking of the severity of PTSD in a victim of sexual abuse, such as the duration of the traumatic event, and the severity/ relationship to the perpetrator. One of the few things that can help the severity of the trauma the victim has faced is their parents. Non-offending parents serve as a potential factor, support from the parents may serve as a buffer against outcomes following disclosure (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014). A non-offending parent may play a crucial role in how the victim copes with the trauma they have experienced. A parent can help their child mentally and emotionally by simply believing their child, and taking action to protect their child so that the abuse may never occur again. Peers are often a considerable support system, for many victims, often confined in their peers. It was also found that the most common recipient of disclosure was a friend and nearly 40% had only disclosed to the same age peer (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014).

In this study, there was a sample size of 6540, in which participants had to fill out a questionnaire which took forty minutes to complete. Participants completed a series of self-report measures related to sexual abuse, PTSD symptoms and protective factors. According to the results of (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014) 14.9% of sexually abused boys and 27.8% sexually abused girls achieved a clinical score of PTSD symptoms. Their results revealed that the gravity of the abuse was significantly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Results in the study of (Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014) confirmed that there is a significant difference in the portion of boys being sexually abused (4%) and girls which are (15%), they also found that the prevalence rate for PTSD among girls between 12 and 17 years is 6.2% meanwhile boys is 3.7%. When dealing with a victim of child sexual abuse, there have to be certain precautions, because victims of abuse are more sensitive to questions being asked than to individuals who were never sexually abused. There was a study conducted in which it included 106 female adolescence, in which all participants were victims of child sexual abuse, 63.3% were sexually abused without penetration and 37.7% with penetration. Nonetheless 67.9% had been abused by a family member, meanwhile, 27.4% were abused by a person who is outside of the family however the perpetrator was known to the victim (Guerra, C., Farkas, C., & Moncada, L. (2018). In this study that was conducted, none of the participants were taking medication to control their symptoms. There was no relationship observed between the symptoms of mental illness in CSA victims and the severity of the abuse, frequency or violence of the abuse (Guerra, C., Farkas, C., & Moncada, L. (2018). This study indicated that throughout their research, the only significance that was proven was the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and the relationship with the perpetrator. However, there were limitations to this study in which it was the use of a single questionnaire.

Many victims of traumatic childhood avoid traumatic or distressing memories so that they could prevent further psychological discomfort (L. S. Harris Et Al). A victim of any abuse will try to cope with the trauma they have faced in many different ways, however, they are usually strategic coping methods in which they are problem-focused and approach-oriented. You may find that avoidance has been one of the poorer outcomes in dealing with traumatic events. Often children who faced traumatic events grow up with a specific memory called RAMS, which means this individual is unable to recall detailed memories or specific actions. It was indicated that retrieving memories of sexual abuse is psychologically painful than retrieving memories of neglect, so it is possible that victims of child sexual abuse may develop rAMS given those feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame are involved (L. S. Harris Et Al). However, (L. S. Harris Et Al) also stated that often individuals who faced CSA develop depression and PTSD, which in its way forces the individual to develop autobiographical memory. This study focused directly on how victims of abuse cope, and recall the abuse. Therefore the conducted study included 48 individuals with the history of child sexual abuse and 45 individuals who were never sexually abused. The study examined the relationship between coping styles, trauma-related psychopathology, and autobiographical memory specifically in adolescence who faced CSA (L. S. Harris Et Al). The minimum age of the participants in this study was 14 years old. The study required the participants to go through multiple testing, such as the dissociation measure, in which the participants were required to complete a self-report questionnaire that included 28 questions designed to measure pathological dissociative experiences. Nonetheless, throughout the study, the participants were tested through a self-report measure of PTSD that diagnoses them according to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Also, they were required to complete a study in which their trauma symptoms and trauma exposure was evaluated. Once they were done with their examination, they analyzed their results and discovered that there was a strong correlation between age and autobiographical memory, however, adults showed they were able to recall more clearly than adolescence. However, it was also discovered that their hypothesis was correct in which distancing coping is associated with rAMS. Furthermore, the study associated trauma-related psychopathology with rAMS, however, they were wrong in the sense that trauma-related psychopathology is associated with autobiographical memory (L. S. Harris Et Al). Memory plays a significant role when associated with child sexual abuse, a child has to grow up recalling the incidents that have taken place. However, certain individuals choose to repress what they remember and to bury it as if it never happened deep within them, those are very few. The majority of CSA victims tend to seek medical attention for depression and PTSD, causing them to vividly recall the events that have taken place. Victims of child sexual abuse grow up unable to trust anyone properly and have troubles in their relationships, victims often tend to choose abusers as their partners. Furthermore, many studies have shown that victims tend to hide their stories for fear of being targeted in the new surroundings that they have built for themselves. Victims of child abuse face many psychological disorders, and if they were to be treated at an earlier stage in their life, or if they had a healthy coping mechanism they would have a sense of ease transitioning from one stage of their life to the next.

Physical Abuse

Child physical abuse is the most noticeable from all child abuse. Physical abuse is the most effective one because it occurs when one person uses physical pain or threat of physical force to intimidate another person. Physical abuse is defined as a physical injury that results in substantial harm from physical injury to the child. Physical abuse includes numerous things, for instance, an all-out physical beating total with punching, kicking, hair pulling, scratching, and genuine physical harm adequate at times to require hospitalization. According to National Statistics on Child Abuse, 44.2% of the children die from physical abuse. This means two in every four death is due to physical abuse. This makes it the number one cause of death in the United States; also one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Even though adults are the cause of the physical abuse to children, youth are the victims. That is the time to step up to prevent it before it is too late.

There are so many articles, which discuss the issue of child physical abuse and how it is so dangerous. Also, in those articles, the writers discuss what is child physical abuse is and what it does to the child when they grow up. In the article Neighborhood effects on physical child abuse, and outcomes of mental illness and delinquency analysis, the authors say that family violence is the most common form of physical child abuse. They did a study showing family violence by trying to examine physical child abuse in the neighborhood. Moreover, they did a project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN). They brought 2,000 children to examine the effect of physical child abuse within the models. The first model was to to study effects on the neighborhood with physical child abuse. The second models were used to show mental illness measures of the effect of neighborhoods. The last models were delinquency measures. The results for the physical child abuse were effective both in externalizing mental illness outcomes and internalizing them. Therefore, this study provides further information about the connection between family violence and mental illness.

Child abuse includes physical mistreatment and neglect and happens everywhere throughout the world. These poor little kids are being hit, kicked, poisoned, burned, slapped, or having objects thrown at them. At the point when a child encounters physical child abuse, the wounds run genuinely deep. In the article Breaking the mold: Socio-ecological factors to influence the development of non-harsh parenting strategies to reduce the risk for child physical abuse, the authors say physical punishment keeps on being a typical type of control in the U. S regardless of signs of its long-term damage to youngsters, including solid hazard for kid physical maltreatment. The study shows that the analyzing of child-rearing practices significant to anticipating child physical abuse, Positive Deviance identifies with those parents who pick

compelling, positive child rearing procedures to teach their kids, notwithstanding being presented to physical punishment and physical abuse in youth. After doing the study, the authors discovered that the short term effects of physical abuse are typically obvious and treatable by an emergency room physician or another healthcare provider. They can range from cuts, bruises, broken bones, and other physical maltreatment. Also, the article showed the long term physical abuse effects from these injuries as well.

It has been found that most people who struggle with drug addiction began from their experience since they were a child. Teenage drug abuse is one of the biggest issues in society today and the problem grows and is larger every year. Drugs are an inescapable power in our way of life today. In the article Occult drug exposure in young children evaluated for physical abuse: An opportunity for intervention, the authors discussed that “drug exposure is an important consideration in the evaluation of suspected child maltreatment.” This shows that constrained information is accessible on the recurrence of drug introduction in children with suspected physical abuse. They did a study to examine occult drug to show the pharmaceutical effect in young children with suspected physical abuse. They brought in children of ages 2 weeks –59 months evaluated for physical abuse by a tertiary referral center Child Protection Team. “Results Occult drug exposures were found in 5.1% (CI 3.6–7.8) of 453 children tested: 6.0% (CI 3.6–10.0) of 232 children with high concern for physical abuse, 5.0% (CI 2.7–9.3) of 179 children with intermediate concern, and 0% of 42 children with low concern”, this shows that Up to 7.9% of young children suspected of being physically abused also had an occult drug Exposure. Given the adverse health consequences associated with exposure to a drug-endangered environment, screening for occult drug exposure should be considered in the evaluation of young children with intermediate or high concern for physical abuse. Also, the emotional effects of physical abuse can last a long time after physical wounds heal. Massive studies have revealed that many psychological problems develop as a result of physical abuse of the child. These children experience more problems at home, at school, and in dealing with peers.

After further research, researchers found out that many children die from physical abuse, and we still are not trying to fix it. In the article Negative/unrealistic parent descriptors of infant attributes associated with physical abuse?, the authors show that in the United States, about 7% of children suffer from physical abuse by their parent, and many children under the age of 15 die of physical abuse. They did a study of an infants 12 months of age who were described with negative development or have been physically abused. They asked the parents to describe their child’s personality and list at least three words to describe their child. The article states, “Of 185 children enrolled, 147 cases (79%) were categorized as accident and 38 (21%) as abuse. Parents used at least one negative/unrealistic descriptor in 35/185 cases (19%), while the remaining 150 cases (81%) included only positive or neutral descriptors. Of the infants described with negative/unrealistic words, 60% were abused, compared to 11% of those described with positive or neutral words.” This shows that the study informs future work to create a screening tool utilizing negative/unrealistic descriptors in combination with other predictive factors to identify infants at high risk for physical child abuse.

The United States has been fighting against child abuse but still many families think beating children is a way of the teaching them the right way. Many people are wrong in thinking of this abuse. In the article The relation of abuse to physical and psychological health in adults with developmental disabilities, the authors say that child physical abuse is considered as a global public health problem. Individuals with developmental disabilities are at excessively high danger of maltreatment. Most developmental disabilities occur from physical child abuse. According to the article, “Abuse experience was reflected by five-factor scores consisting of three child abuse factors (childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, childhood disability-related abuse) and two adult abuse factors (adult sexual abuse, adult mixed abuse)”, this demonstrates youth disability-related maltreatment and grown-up blended maltreatment altogether anticipated lower dimensions of mental and physical wellbeing in an example of grown-ups with formative inabilities and how people discoveries feature the significance of tending to mishandle and its sequelae in the developmental disabilities community. Many children these days have mental problems from their environment or their parents. When parents treat the child very bad when he is young the kid begins to be on his own and not trusting anyone or loving anyone, and these conditions create disability. Many families rely on beatings to raise their children, believing that they are advising them and teaching them the difference between right and wrong. From these studies that we read about the educational studies have shown that children do not know or understand why their parents beat them. They did not have the necessary growth to realize that beatings were caused by punishment for the wrong behavior they had done. The beatings reinforce the child’s violent behavior, and he may think if his parents have the right to hit him, he has the right to hit them back and that your child may be used to beating you every time he behaves badly. Also, the beating of children in schools is legally prohibited in many countries and it is not right to hit the children. The beating may lead to the isolation of the student from the others. The student is afraid to go to school and to integrate with his peers because of embarrassment because of teacher beating him in front of his friends. The child may be an outstanding student, but his level of study takes a decline due to the negative impact on his personality.

Finally, it may be concluded that child physical abuse is the most common abuse in our lives, and the effects of physical abuse on the child may last a lifetime and may include brain damage, loss of vision and hearing leading to disability, even minor injuries may cause the child who has been abused to have delayed learning, behavior, and emotions. Knowledge and great emotional problems affect his development in life. Some of the effects of physical abuse on children may lead to significant behavioral problems. Children who are suffering from anxiety and depression as a result of the abuse they have been exposed to often tend to smoke, drink alcohol, and other dangerous and unhealthy behaviors have to do with adapting to emotional and behavioral problems. Emotional abuse

A therapist from Psychology Today states that emotional abuse, also known as psychological abuse, characterizes an individual exposing another individual to behavior that may result in many effects to a person’s future (LPC, Matthews). A person who experiences emotional abuse at a young age can have a destructive effect on their self-esteem and relationship with others. Emotional abuse turns an individual against themselves due to the fact that they are being manipulated through harsh words. For example, if someone is utilizing derogatory terms repetitively, the victim is bound to believe it. Having this scenario constantly occurring can lead to self-harm and self-hatred. Other behaviors that define emotional abuse is when an adult reject, isolates, corrupts, ignores, terrorizes, overpressures, and verbally assaults a kid to make them feel less worthy of their selves. Emotional abuse may damage children of all ages but may be dangerous with infants and toddlers leaving them with permanent developmental deficits.

Childhood abuse is generally known as a major public health problem with many effects on adult mental health, such as suicidal behaviors and mood and anxiety disorders (Christ, 2019). Studies have shown that childhood abuse has been constantly linked to depressive disorders in adulthood. According to a research article from PLOS, childhood emotional abuse has been linked to depressive symptoms (Christ, 2019). While every type of childhood abuse is linked to depressive symptoms, most studies have shown that emotional abuse is more strongly related to depression. In the article “Linking childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms: The role of emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems” it states “CEA refers to an aggressive attitude towards a child, which is not physical in nature, and may include verbal assaults on one’s sense of worth or wellbeing, or any humiliating or demeaning behavior” (Christ, 2019). The article also explains that CEA can lead to an increase risk of adult depression. Therefore, the main focus of this study is to determine the psychological processes that may act like a negotiator in this relationship. Also another main focus of this study is two see whether emotional dysregulation and interpersonal problems associated with childhood abuse and depression. The aim of this study was three things. First, we inspected the impact of childhood emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical abuse on depressive symptoms in a European sample of female colleges students. Based on this, we hypothesized that only on emotional abuse would be independently associated with depressive symptoms. Second, if evidence for the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depression were evident, we hypothesized to examine whether this relationship would it be mediated by of emotional dysregulation and interpersonal problems. Finally, we aimed to identify whether specific interpersonal problems could be identified as particularly important explaining the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms.

For this study the participant that were used were females that are currently studying in the Netherlands. The study sample consisted of 276 female college students with the mean age of 21.7 years. The participants were born in the Netherlands, many were single, living with their parents or with roommates, and studying psychology. The age, country of birth, country of birth of parent, relationship status, living situation were also collected.

The results were as shown and the tables and charts provided of the research study. The highest relation was found between childhood emotional abuse and childhood physical abuse whereas the lower correlation was found between childhood emotional abuse and childhood sexual abuse. 59.8% of the participants were reported with no depressive symptoms, however, 30.1% were reported with some mild depressive symptoms, 8% were reported moderate depressive symptoms and 2.1% was reported with severe depressive symptoms. The first aim of the study was to examine which childhood abuse was associated with depressive symptoms, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in female college students. And as hypothesized childhood emotional abuse was independently associated with depressive symptoms and emotional dysregulation, whereas the other kind of childhood abuses were not. These results proved that childhood emotional abuse was a more strongly related to depression then childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse. The reasoning behind this could possibly be because of the children’s development of emotion regulation skills, which is highly influenced by the interactions with the primary caregiver and the family emotional feelings.

This study had many strengths and limitations. Some strengths were that this was the first study to explore the mediating role of interpersonal problems between childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms. It was also the first to confirm previous research in identifying whether emotional dysregulation was the mediator between childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms in college students. Some limitations where that the results had to be taken with caution due to the fact that it was a cross-sectional study. Also the study relied a lot on self-report measures, however all measures have a good psychometric properties and are widely used. Lastly the prevalence of some a B childhood abuses were relatively low, which limited to statistical power to detect possible week associations between other types of uses.

Child maltreatment is a major public health concern. Many studies have compared it to all types of childhood abuse, however it has been proved that the long-term impact of emotional maltreatment under mental health is more related to emotional abuse. In the study “Childhood emotional maltreatment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative adult sample from the United States” the purpose of the research was to examine the relationship of emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and both with other types of child maltreatment (Taillieu, 2014). The data was from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The measures of this study were taken from emotional maltreatment, other childhood maltreatment, family history of dysfunction, and mental disorders.

The data collected from the NESARC were taken from the general US population and the results are as follows (Taillieu 2014). Childhood emotional maltreatment was 14.1%; the most widespread form was emotional neglect be 6.2%, followed by emotional abuse being 4.8%. The least common pattern of childhood emotional maltreatment was experiencing both emotional neglect and emotional abuse at 3.1%. Experiencing both emotional neglect and emotional abuse was more prevalent among females compared to males being a 4% versus 2%, and the categories of all emotional maltreatment were more dominant among divorced, separated, and widowed individuals (Taillieu, 2016). Participants with a higher household income and a higher level of education were less likely to report childhood emotional maltreatment then participants with a low household income and a lower level of education.

The effects of emotional abuse can be both devastating and extensive from childhood into adolescence and adulthood. Children who experience emotional abuse develop many chronic health problems when they become adults. Some of these problems are heart diseases, obesity, mental health issues, eating disorders, headaches, etc. If left untreated, these health problems can develop into more serious conditions in the future leaving you susceptible to more harm. Not only can it lead to health problems, but it can also cause damage to a child’s brain development. This can lead to problematic behaviors, increased occurrences of physical and mental health issue, and long-term learning difficulties. Kids won’t be able to focus in school and be on the same track as their other classmates. They will have a slower pace in learning which will lead them to being behind in school. Thinking that it is okay for a child to be treated this way, the child may start to participate in bad behavior towards other kids. Many children have been at risk of harm from emotional abuse. Statistics show that 1 in 14 children have experienced emotional abuse by a parent or guardian. In 2017, over 19,000 children were identified as needing protection from emotional abuse. Report shows that girls show a higher percentage of maltreatment among boys. When it comes to racial and ethnic groups, black children are the highest percentage of maltreated kids, with 1 in 5 children. In today’s society, people don’t acknowledge that they are emotionally abusing a child and how it can affect them in the long run. Therefore, this leads to children continuously getting abused. Today’s society tend to not look at what’s being done to their kids rather just focusing on themselves more than their kids. All children have particular needs that must be met. That is receiving love and attention, being protected from harm, to have their needs heard, etc. On top of all that, kids also struggle with challenges such as sensitivity and emotional regulation. Child Neglect

A really common type of child abuse is child neglect. According to Child Welfare Information Gateway (2018), there is a higher number of children who suffer from neglect abuse than there are for physical and sexual abuse combined. Yet, victims are not often identified, for the most part, it is because neglect is a type of child abuse that is an act of others not doing something. There might be some overlap between emotional abuse and emotional neglect definitions. But neglect is a pattern of failure to deliver the basic needs of a child. A particular act of neglect may not be regarded as child abuse, but a constantly repeated action is definitely child abuse. There are three fundamental types of neglect; physical neglect, neglect of education, and neglect of emotion (Tudoran, 2015). To begin with, physical neglect is the failure to provide food, clothing appropriate for the weather, supervision, a home that is secured and safe, and/or medical care, as needed for the child. Tudoran (2015) stated that “Physical neglect and the safety of the child by Insufficient care which leads to underdevelopment of the children (not motivated by organic causes), malnutrition and mental underdevelopment.’’ This demonstrates that physical neglect means not having a secure place to sleep, starvation and no medical support for a child or teenager. It is also essential for human (for young children) growth and development to have a safe, supervised environment to grow up and live in. This neglects affects child physical appearances and health throughout his life. Once children are in school, school staff often notice child neglect markers such as poor hygiene, poor weight gain, poor medical care, or frequent school absences. Many excuses can be heard for parental neglect, such as “They lost their jobs and have no money,” “They’re young and they didn’t know,” and “They couldn’t find a babysitter, and they had to go to work, or they would have lost the job.” As illustrated by these examples, neglect is still regarded as a less harmful form of child abuse, but according to Bagley, “neglect is not only the most frequent type of abuse; it can be just as lethal as physical abuse.” Neglect may be physical, educational, or emotional as well. Then, educational neglect. is the failure to enroll a school-age child in school or to provide necessary special education. This includes allowing excessive absences from school. In most cases, this refers to younger children who still demand as dependents of the parent because of that one of their rights as children (Angela, 2015). Although, parents are primarily responsible for meeting their children’s needs; however, we can’t blame the parents for every failure. There is many cases, such as schools that fail to meet the educational needs of a child, is beyond parental control. Educational neglect may cause the child to fail to develop basic life skills, drop out of school, or display disruptive behavior. It may pose a significant threat to the child’s emotional well-being, physical health, or normal psychological growth and development, especially if the child has unmet special educational needs (Dubowitz, 2013). Also, Child Protection Services (CPS) who protects children from caregivers that may be harm them are typically only involved in parental inaction that is considered to be the major contributor to the need of the child (Dubowitz, 2013).

Lastly, emotional neglect is the falling to provide emotional support, love, and affection. This includes neglecting the emotional needs of the child and then failing to provide psychological treatment as needed. When someone does not provide emotional support, especially when the kid need it, or when they are supposed to be provided, it means that the child is still emotionally neglected (Angela, 2015). The most common cause of emotional neglect is an overworked and/or overly-ambitious parent who places the needs and desires of their own ambition, and their company’s demands ahead of those of their family. In most of those instances, it is the children who suffer from having none of their emotional needs met. In this case, they are being neglected emotionally. Parental behaviors that are considered emotional child abuse when they ignore the child consistently by declining to respond to the child’s need for stimulation, nursing, encouragement, and protection or failure to recognize the presence of the child (M. Sperry, 2013). As of now, child neglect is considered as the largest part of child abuse in the United States, and nearly two-thirds of all reported cases in child protection is about neglect abuse (Dubowitz, 2015). Statistically speaking, according to the United States. Children’s Bureau, “Neglect is the most common form of maltreatment. Of the children who experienced maltreatment or abuse, three-quarters suffered neglect.” While physical abuse might be the most visible, other types of abuse such as emotional abuse and neglect, also leave deep, lasting scars on the children (Smith, M.A, Segal). Child neglect has become a major social issue and a primary cause for many people that are suffering and having personal problems. According to M. Sperry, Widom, studies have shown that “Adjusting for age, sex, and race, individuals with documented histories of child abuse and neglect reported significantly lower levels of social support in adulthood [total (p < .001), appraisal (p < .001), belonging (p < .001), tangible (p < .001), and self-esteem support (p < .01)] than controls.” With the adjusting for age, sex, race, and previous psychiatric diagnosis, social support proved the strong connection in the relationship between child abuse and neglect and anxiety and depression in adulthood.

Neglect is not a little thing. It can be extreme, as in failing to provide adequate food, shelter, and clothing for the most basic needs of a child. Or it might be less apparent but still quite traumatic. It can leave kids traumatized, living on the verge of terror (which becomes integrated into normal everyday life and the child really doesn’t feel the fear anymore but stuffs it back behind walls of denial). Later, when it is safe the fear surfaces as panic attacks, anxiety disorders, nightmares, fear of rejection. Long-term neglect leaves children with horrendous problems of abandonment, depending on your age and how long it lasted and whether someone else was in charge of you; and if you had at least one person to trust or show you love (like a grandparent cousin or aunt). Perhaps a teacher? You may have less severe consequences and difficulties if there was someone to help, and you may recover quickly. As a matter of fact, religions and culture play a role in infusing the parent-child relationship and allow for neglect to show up. It is important to understand and recognize that neglect often involves continuous intervention with support and monitoring. Humility is essential with regard to different cultural and religious traditions. We should prevent the ethnocentric attitude (i.e., thinking that “my way is the correct way”). Alternatively, while respecting different cultural practices, those traditions that clearly harm the children should not be accepted. Parents and religious and cultural leaders have to work together in order to find a satisfactory compromise; however, an agreement cannot be reached if the child is either harmed or in danger. Regarding that neglect is a deliberate act to harm a child. Most children are not neglected even if their “parents” ignore them or forget them. A lot of parents are negligent in an innocent way because not all the parents are taught the good skills to raise children or have the experience to deal with kids. So, this lack of resources and information lead to how the parent’s behavior with their children. It might be because that’s what the parents are capable of at that time. For instance, the parent job or professional play a role in the way they treat their children while growing up which ultimately contribute to neglect because poor communication with parents may lead to a lack to of understanding of the treatment plan (Dubowitz, 2013) However, parents have a duty and they are primarily responsible to meet their children’s basic needs, and the show of neglect toward their kids means that they had failed in their duty to take care of them.

Neglect may have long lasting consequences. Based on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nearly two-thirds of all child abuse – related deaths involve neglect. So, some of the consequences a neglected child may experience are problems with health and development, emotions, behavior toward other and even death. These consequences are most likely to occur with young children. Also, most often neglect fatalities are caused by lack of supervision, chronic physical neglect, or medical neglect. Malnutrition can affect brain development. A lack of adequate immunizations and medical issues could result in a variety of health conditions. The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well – Being (NSCAW) found that 3 years after being removed from a negligent situation, 28 percent of children suffered from chronic health conditions. Neglect can cause problems of attachment, self – esteem, and difficulty of trusting others. Neglected children may struggle to develop healthy relationships and may experience behavior disorders or disorder social involvement disorder. NSCAW data showed that over half of those mistreated in younger age were at risk of substance abuse, delinquency, truancy, or pregnancy.

When the teenager has been abused or neglected as a child, it can leave him feeling wounded, deprived, and wronged by those who he loves and trust. The hurt can be particularly profound if our own parents were the ones that caused the pain to us. These hurts will continue to affect us and our subsequent relationships if they are not resolved. The child will need psychiatric and psychological care (Viswalingam, 2018). Medicine can help when the severe symptoms show up when the child gets in touch with their feelings and emotions again. Recovery takes time and is a slow process. Expect some setbacks and tough times (Sathiadas, 2018). The first step in a neglected child’s treatment is to ensure his safety. By providing resources and education to the family, providers maybe able to reduce the neglect. On the other hand, some psychiatrists may fail to follow recommended approaches and to identify the medical or psychological social needs, which can be responsible for the continues of the neglect.

Finally, neglecting children can have devastating effects on children’s intellectual, physical, social, and psychological development. Neglected and abused infants and toddlers fail to develop a secure connection with their neglecting and/or abusive carrier provide. They develop anxious, insecure, or disorganized/disoriented connection with that carrier provide. Neglected children appear to be more generally passive and socially withdrawn in their interactions with others. Neglect comes in all forms and levels of severity, but it is a hard concept to nail down. It remains important to point out to the public that child abuse and neglect are serious threats to the healthy growth of the child and that opening violence against children and persistent lack of care and supervision are unacceptable. People have the capacity to take personal responsibility for reducing child abuse and neglect by providing mutual support and protecting to all the children within their family and community. Prevention is better than healing. Child abuse leads to numerous bathing effects not only for abused children, but also for the abuser. We should avoid it getting worse because today’s kids will be tomorrow’s leader.

It may be concluded that the child abuse is the most dangerous thing in our society because children are the future of our world. If we abuse the children by one of these things child abuse; physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, There will be no future in our life. Children are the ones who makes our life smile, they are the happiness in this world and many people called them angels but if we human been change the way they think and they the way see the world in their eyes, there will be no longer angels. Throughout this literature review, we have also mentioned Child abuse cases developmental disabilities and many children die from it. In most cases, these children that their family abuses them or the environment abuse them such with child abuse; physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect which were discussed. Some of these disorders people still don’t think that they are the cause of negative things in our society. However, these abuses do have their own effects on the child. As well, these abuses can lead to there being physical health problems. Especially when children get abused by their environment and they do not have anyone to reach out. By bringing awareness to this child abuse we can reduce the possibilities of children getting child abuse.

1. Christ C, de Waal MM, Dekker JJM, van Kuijk I, van Schaik DJF, Kikkert MJ, et al. (2019) Linking childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms: The role of emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0211882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0211882

2. Dubowitz, Howard. “Neglect in Children.” Pediatric Annals, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4288037/.

3. Gateway, Child Welfare Information. “Acts of Omission: An Overview of Child Neglect.” Acts of Omission: An Overview of Child Neglect -Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2018, www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/focus/acts/.

4. Guerra, C., & Pereda, N. (2015). Research With Adolescent Victims of Child Sexual Abuse: Evaluation of Emotional Impact on Participants. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse,24(8), 943-958. doi:10.1080/10538712.2015.1092006

5. Guerra, C., Farkas, C., & Moncada, L. (2018). Depression, anxiety, and PTSD in sexually abused adolescents: Association with self-efficacy, coping and family support. Child Abuse & Neglect,76, 310-320. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.013

6. Harris, L. S., Block, S. D., Ogle, C. M., Goodman, G. S., Augusti, E., Larson, R. P., . . . Urquiza, A. (2015). Coping style and memory specificity in adolescents and adults with histories of child sexual abuse. Memory,24(8), 1078-1090. doi:10.1080/09658211.2015.1068812

7. Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014). Post Traumatic Stress Disorder/PTSD in adolescent victims of sexual abuse: Resilience and social support as protection factors.

Ciência & Saúde Coletiva,19(3), 685-694. doi:10.1590/1413-81232014193.15972013 8. Hughes, R. B., Robinson-Whelen, S., Raymaker, D., Lund, E. M., Oschwald, M., Katz, M., … Nicolaidis, C. (2019). The relation of abuse to physical and psychological health in adults with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal.

9. Petska, H. W., Porada, K., Nugent, M., Simpson, P., & Sheets, L. K. (2019). Occult drug exposure in young children evaluated for physical abuse: An opportunity for intervention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 412–419.https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.015

10. Rosner, R., König, H.-H., Neuner, F., Schmidt, U., & Steil, R. (2014). Developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy for adolescents and young adults with PTSD symptoms after physical and sexual abuse: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 15(1), 1–18.https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1186/1745-6215-15-195

11. Santos KL. Neighborhood effects on physical child abuse, and outcomes of mental illness and delinquency: An HLM analysis. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 2019;80(3-A(E)).

12. Sathiadas, M G, et al. “Child Abuse and Neglect in the Jaffna District of Sri Lanka – a Study on Knowledge Attitude Practices and Behavior of Health Care Professionals.” BMC Pediatrics, BioMed Central, 5 May 2018,www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5935930/.

14. Taillieu, T., Afifi, T., Brownridge, D., & Sareen, J. (2014). Examining the Relationship Between Childhood Emotional Abuse and Neglect and Mental Disorders: Results from a Nationally Representative Adult Sample from the United States. PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e529382014-057

15. Tener, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2014). Adult Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,16(4), 391-400. doi:10.1177/152483801453790

16. Tudoran, D., & Boglut, A. (2015). Child Neglect. Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 47(1), 224–233. Retrieved fromhttp://ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&db=a9h&AN=110261513&site=ehost-live

17. The National Children’s Alliance. “National Statistics on Child Abuse.” National Childrens Alliance, 2014,

www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/media-room/nca-digital-media-kit/national-statistics-on-child-abuse/. 18. http://ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-65232-264&site=ehost-live. Accessed

March 5, 2019. 19. Yoon, S., Barnhart, S., & Cage, J. (2018). The effects of recurrent physical abuse on the co-development of behavior problems and posttraumatic stress symptoms among child welfare-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 29–38.https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.01

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

- Terms of Service

- Accessibility

- Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2024

Early identification and awareness of child abuse and neglect among physicians and teachers

- M. Roeders 1 , 2 ,

- J. Pauschek 2 ,

- R. Lehbrink 2 , 3 ,

- L. Schlicht 2 ,

- S. Jeschke ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-1479-1367 1 , 2 ,

- M.P. Neininger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5208-0888 4 &

- A. Bertsche ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2832-0156 1 , 2

BMC Pediatrics volume 24 , Article number: 302 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

176 Accesses

Metrics details

Child abuse and neglect (CAN) causes enormous suffering for those affected.

The study investigated the current state of knowledge concerning the recognition of CAN and protocols for suspected cases amongst physicians and teachers.

In a pilot study conducted in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania from May 2020 to June 2021, we invited teachers and physicians working with children to complete an online questionnaire containing mainly multiple-choice-questions.

In total, 45 physicians and 57 teachers responded. Altogether, 84% of physicians and 44% of teachers were aware of cases in which CAN had occurred in the context of their professional activity. Further, 31% of physicians and 23% of teachers stated that specific instructions on CAN did not exist in their professional institution or that they were not aware of them. All physicians and 98% of teachers were in favor of mandatory training on CAN for pediatric residents and trainee teachers. Although 13% of physicians and 49% of teachers considered a discussion of a suspected case of CAN to constitute a breach of confidentiality, 87% of physicians and 60% of teachers stated that they would discuss a suspected case with colleagues.

Despite the fact that a large proportion of respondents had already been confronted with suspected cases of CAN, further guidelines for reporting procedures and training seem necessary. There is still uncertainty in both professions on dealing with cases of suspected CAN.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Child abuse and neglect (CAN) is a global problem [ 1 ]. It is estimated that incidents of different types of sexual abuse vary from 8 to 31% for girls and from 3 to 17% for boys throughout the world [ 2 ]. In Germany, more than 59,900 children and adolescents were identified as being at risk of neglect, and psychological, physical, or sexual violence in the year 2021 [ 3 ]. Child abuse and neglect are a widespread problem. The number of unreported cases is estimated to be high. The officially reported cases of CAN are below the 1% limit. However, retrospective surveys of young people and adults indicate a lifetime prevalence of more than 10% [ 4 ].

CAN is a problem on several levels. It is well known that the long-term consequences of CAN are severe and often persistent [ 5 ]. For example, affected children have a higher risk for developing an internalizing and externalizing mental disorder, drug abuse, suicide attempts, sexually transmitted infections, and risky sexual behavior, or, once they are adults, to abuse their own children [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ].

In addition to the enormous burden for the individual, there are economic consequences for society. The annual costs of CAN are estimated to range from 11.1 to 29.8 billion Euros in Germany per year [ 10 ] and up to 124 billion US Dollars in the US [ 11 ]. Studies suggest that a 10 per cent decrease of CAN prevalence in America and Europe could lead to annual savings of 105 billion dollars [ 12 ]. Thus, CAN carries burdens both for the affected individual and society.

Despite the high prevalence and resulting consequences, studies regarding early identification and action procedures are rare [ 13 ]. In addition, some issues have not been adequately addressed in professional groups such as teachers and physicians. Members of these professions are usually the adults outside the family who are in closest and most frequent contact with children. They therefore have the potential to play an essential part in the identification of CAN [ 14 ] and should be adequately trained [ 15 ]. Nevertheless, even for those professionals the detection of CAN often remains difficult [ 16 ]. As both physicians and teachers play an important role in child protection, it is essential to investigate their current level of understanding of CAN and their strategies for dealing with suspected cases. In this way, an accurate baseline for training can be established, in order that these professions be adequately qualified to intervene early in cases of CAN. We therefore performed a pilot study in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania surveying teachers and physicians about their current knowledge of CAN, actions taken in case of a CAN, existing protocols in their institutions, training on the topic in the past and their individual need for further training. We aimed to compare the knowledge and information needs of those two professional groups, which both can act as key players in the detection of CAN. In the long term, those insights will enable the development of new training programs, or the improvement of those that already exist.

Materials and methods

Setting and participants.

After approval of the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Rostock University and the Rostock school authority, we conducted this pilot study with physicians and teachers from May 2020 to June 2021. In total, three hospitals as well as eight schools in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania agreed to participate in the pilot survey. Two university hospitals and one primary care hospital were included in the study. In total, these hospitals reflect around 30% of the bed capacity for pediatric and adolescent medicine in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. It can be assumed that the number of physicians in the departments contacted was around 70, resulting in a response rate of around 65%. Clinic directors and principals of schools received an e-mail containing an information sheet and a link to access the questionnaire and were asked to spread the e-mail in their teams.

The survey was accessible without registration or a password. The link provided in the invitation e-mails led directly to the questionnaire. For data collection we used EvaSys, a software for conducting surveys [evasys V9.0 (2404), EvaSy GmbH]. Participants were informed about the study objectives, voluntary participation, and anonymization in the questionnaire introduction. The participants were informed that by filling in the questionnaire they agreed to participate in the study.

Questionnaire

A study team consisting of pediatricians and medical students interested in the topic of CAN designed the questionnaire. Current literature was researched during the development of the questionnaire. To improve comprehensibility, clarity, and readability, the questionnaire was pre-tested with 10 physicians and 10 teachers. After the pre-test, the physicians and teachers were interviewed about the questionnaire. This was followed by further adjustments to optimize the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted of single-choice, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale answering options. After a short introduction, the participants were asked questions on the following topics (Supplement 1 ):

Personal experiences of physicians and teachers regarding the topic of CAN.

Knowledge about the topic of CAN, including bruising patterns.

Actions taken in case of a CAN and existing protocols in their institutions in cases of suspected CAN.

Confidentiality and associated difficulties in reporting procedures.

Training on the topic of CAN.

Additionally, sociodemographic data were collected at the end of the questionnaire.

With regard to the question of bruising patterns, the body parts were adapted to the TEN-4-FACESp Bruising Rule [ 17 ].

Calculations were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 26, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Frequencies are reported as numbers and percentages. For further statistical analysis, we applied Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests and Mann-Whitney-U-tests as appropriate. A p -value ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Participants

In total, 45 physicians and 57 teachers took part in the survey. Sociodemographic data summarized in Table 1 .

Of teachers, 13/57 (23%) reported working at an elementary school, 10/57 (18%) at a school for children with special needs, 24/57 (42%) at a grammar school, and 10/57 (18%) at an other secondary school.

Personal experiences of physicians and teachers regarding child abuse and neglect

Of the participants, 38/45 (84%) physicians and 25/57 (44%) teachers reported that they had been confronted with cases of CAN in the past. None of the physicians, and 10/57 (18%) of teachers stated that they were unsure about whether they had witnessed a case of CAN before. Of physicians, 7/45 (14%) and of teachers, 22/57 (38%) reported that they had not been involved in any cases of CAN so far.

Physicians (32/45; 71%) reported more frequently having already encountered a case of physical abuse compared to teachers (15/57; 26%, p < 0.001). Also, experiences with cases of physical neglect were reported more frequently by physicians (32/45; 71%) than by teachers (13/57; 23%; p < 0.001). More details are shown in Table 2 .

Knowledge about child abuse and neglect

Knowledge of typical signs and behavior patterns.

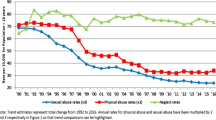

Of the participants, 40/45 (89%) physicians and 51/57 teachers (89%; n.s.) correctly assumed that the back and bottom are very likely body sites for signs of CAN. In addition, 35/45 (78%) physicians and 24/57 (42%; p < 0.001) teachers correctly indicated that injuries to the chin and nose were unlikely indicators of possible CAN. Further information is presented in Fig. 1 .

Legend to Fig. 1 : Respondents’ answers on the probability of child abuse if the respective body parts were affected. Respondents could indicate probabilities on a Likert scale ranging from very probable to very unlikely

Correct answers are marked with *. Total respondents: Physicians n = 45, Teachers n = 57

Asked for their opinions on what emotional abnormalities could occur in the context of CAN, 41/45 (91%) physicians and 43/57 (75%; p = 0.039) teachers indicated that verbal and socioemotional developmental delays might occur. More details are shown in Table 3 .

When asked which parental behavior could most likely indicate CAN, 41/45 (91%) physicians and 44/57 (77%; n.s.) teachers responded slight irritability and overwhelming demands. Further, 40/45 (89%) physicians and 31/57 (54%; p < 0.001) teachers reported inappropriate reactions (exaggerated or underexaggerated) as indicators for CAN (Table 4 ).

Estimated long-term effects

Of physicians, 37/45 (82%) and 42/57 (74%; n.s.) teachers assumed that children who have had experiences of abuse and/or neglect might behave similarly towards their own children in the future.

42/45 (93%) physicians and 52/57 (91%; n.s.) teachers anticipated long-term consequences for affected children due to a failure to report CAN.

Actions and instruction procedures in cases of suspected child abuse and neglect

Where CAN was suspected, physicians (39/45; 87%) would discuss the case with colleagues more frequently than teachers (34/57, 60%; p = 0.003). More details on actions physicians and teachers would consider are shown in Table 5 .

To the question whether specific instructions regarding responses to suspected CAN were in place, 31/45 (67%) physicians and 44/57 (77%) teachers answered, “yes, there are specific instructions in my institution”; 5/45 (11%) physicians and 1/57 (2%) teachers answered, “no, there are no specific instructions in my institution”; and 9/45 (20%) physicians and 12/57 (21%) teachers answered, “I am not aware of specific instructions in my institution”. 42/45 (93%) of physicians and 48/57 (84%; n.s.) of teachers said that a generally applicable guideline for dealing with suspected cases of CAN could have a positive effect.

Impact of confidentially

When asked whether the duty of confidentiality influenced the respondents in their actions, 14/45 (31%) physicians and 23/57 (40%; n.s.) teachers agreed.

When asked in which scenarios a breach of confidentiality occurs according to the participants, 6/45 (13%) physicians and 28/57 (49%; p < 0.001) teachers assumed that sharing information with colleagues constituted a breach. 17/45 (38%) of physicians, and 7/57 (12%; p = 0.003) of teachers, assumed that passing on information to the police would be a breach of confidentiality. Multiple answers were possible. Further results are displayed in Table 6 .

Training on the topic of child abuse and neglect

2/45 (4%) of physicians reported that they felt that CAN was a taboo subject in the professional setting, compared to 10/57 (18%; p = 0.041) of teachers. However, both professional groups (physicians: 34/45, 76%; teachers: 46/57, 81%; n.s.) supported the importance of increasing public awareness of the issue.

In terms of training, 43/45 (96%) of physicians and 40/57 (70%; p = 0.001) of teachers reported that they had already attended training on CAN during or after their studies (multiple answers were possible). 43/45 (96%) of physicians, and 53/57 (93%; n.s.) of teachers, confirmed the importance of continuous education to deepen knowledge, including after the completion of their studies.

The idea that the topic of CAN should be a mandatory part of the training for pediatricians and teachers was supported by 45/45 (100%) of physicians and 56/57 (98%; n.s.) of teachers.

Among physicians, 32/45 (71%) reported feeling adequately informed about the topic compared to 21/57 (37%; p < 0.001) of teachers. 34/45 (76%) of physicians, and 22/57 (39%; p < 0.001) of teachers, still required more information regarding CAN.