Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 May 2023

The transforming landscape of dementia research

Nature Aging volume 3 , page 459 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3456 Accesses

1 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Rapid progress in the development of novel biomarkers and lifestyle interventions and the emergence of the first disease-modifying therapy have revolutionized our approach to dementia diagnosis, prevention and therapy. In this Focus issue, Nature Aging presents a collection of reviews and opinion pieces on recent advances in dementia research.

Dementia is a major public health challenge that is caused by a range of neurodegenerative disorders and that has debilitating effects on the cognitive function and daily lives of affected individuals. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, and accounts for over 60% of cases. Aging is the biggest risk factor for dementia. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) , over 55 million people worldwide live with dementia, and this is forecast to rise to 78 million by 2030 owing to the growing older adult population, which will have marked social and economic effects. The current lack of a cure for dementia and the burden it places on individuals, caregivers and healthcare systems worldwide underscores the urgent need for a timely diagnosis, prevention and therapy strategies. In this issue, Nature Aging introduces a collection of Reviews, Perspectives and Comments that cover the most recent advances in dementia research.

Targeting a disease requires an understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Animal models of AD have been instrumental in our understanding of the disease mechanisms and exploration of therapeutic targets. However, they have been often criticized for a lack of translational success owing to a long history of drug failures. In a Perspective in this issue, Padmanabhan and Götz provide a defense for using animal model systems to study AD, and advocate for incorporating aging into experimental design to enhance the translational value of animal models.

Molecular imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography, that have been used for decades to establish the presence of brain pathology and track disease progression have recently been complemented by analyses of fluid biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid or blood, which are becoming increasingly accurate for prognosis and diagnosis. With the recent approval of two disease-modifying treatments that target amyloid pathology (aducanumab and lecanemab), the need for accurate AD biomarker testing in clinical practice is going to increase. In a Comment , Schindler and Atri highlight the accuracy and robustness of the use of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in AD research, clinical trials and diagnosis, and their utility as a benchmark for the development of novel blood-based biomarkers (BBBMs). In recent years, BBBMs have been shown to display high diagnostic accuracy and distinguish AD from other neurodegenerative diseases. In their Review , Hansson and colleagues provide a comprehensive update on the development of BBBMs, discussing their path to implementation in clinical practice; how they can facilitate the identification of individuals with pre-symptomatic AD for clinical trials; and how they can improve detection of disease-modifying effects of novel drugs or lifestyle interventions.

Given the long prodromal phase of the disease, identifying individuals who are at risk of AD before the clinical presentation of the symptoms offers an opportunity to treat patients before substantial damage has occurred and may help to prevent or delay the onset of dementia. In their Perspective , van der Flier and colleagues propose a strategy for a future with personalized medicine for AD that includes effective and patient-orchestrated diagnosis, prediction and prevention, arguing that empowering the public and patients with dementia to be more actively engaged in managing their health can help to prevent or delay disease onset. In a Review , Rafii and Aisen discuss the recent results of anti-amyloid immunotherapy trials in patients with symptomatic AD and how this therapeutic strategy is being tested in asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing AD, in phase 3 trials.

In parallel to the development of pharmacological treatments, there is growing awareness about the importance of the environment, social factors and behavior for the risk of dementia. Lifetime social participation can reduce the risk of dementia by increasing cognitive reserve, reducing stress and depression, and promoting healthy lifestyles. In their Review , Sommerlad and colleagues highlight that greater social participation in mid-life and late life is associated with a 30–50% lower risk of subsequent dementia, and point to the need for future research, prevention efforts and policy focus on the potential of social participation to mitigate the effects of neuropathology for brain health. Mielke and colleagues discuss in a Comment the contributions of sex, gender, race and ethnicity in dementia risk globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and the need for future research to take these factors into account for diagnostic and intervention purposes. In their Comment , Lock and colleagues highlight the societal barriers to a healthy brain and present recommendations from the Global Council on Brain Health for achieving greater brain health equity. Dua and colleagues, in another Comment , provide an insight into the WHO’s blueprint for dementia research, which advocates for global prioritization of dementia research through coordinated efforts in standardized, timely and high-quality evidence generation, empowering people with lived experience, addressing inequity and diversity, and sustainable funding.

In conclusion, effective diagnosis, prevention and therapy strategies are essential in addressing the global burden of dementia. A comprehensive approach that combines advances in diagnostic techniques, lifestyle interventions and personalized therapeutic interventions is emerging and will transform how we approach dementia care, and facilitate early detection, prevention and better management of dementia. The growing prevalence of dementia emphasizes the need for continued research, collaboration and investment in this field to improve the quality of life of those living with dementia and their caregivers.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

The transforming landscape of dementia research. Nat Aging 3 , 459 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00433-x

Download citation

Published : 18 May 2023

Issue Date : May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00433-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A delphi consensus to identify the key screening tests/questions for a digital neurological examination for epidemiological research.

- Vasco Ribeiro Ferreira

- Carol Brayne

- Valentina Gallo

Journal of Neurology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

- Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

As the largest nonprofit funder of Alzheimer's research, the Association is committed to accelerating the global progress of new treatments, preventions and, ultimately, a cure.

Information for Researchers

Research we fund, apply for a grant, find a clinical trial, efforts we lead, the first survivor of alzheimer's is out there, but we won't get there without you., learn how alzheimer’s disease affects the brain..

Take the Brain Tour

Don't just hope for a cure. Help us find one.

Keep up with alzheimer’s news and events.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2021

The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research: findings of a systematic qualitative review

- Tim G. Götzelmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6998-0850 1 na1 ,

- Daniel Strech 2 &

- Hannes Kahrass 1 na1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 32 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

14 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

When including participants with dementia in research, various ethical issues arise. At present, there are only a few existing dementia-specific research guidelines (Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in Clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment Alzheimer’s disease (Internet). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease ; Food and Drug Administration, Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry [Internet]. http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/alzheimers-disease-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industy ), necessitating a more systematic and comprehensive approach to this topic to help researchers and stakeholders address dementia-specific ethical issues in research. A systematic literature review provides information on the ethical issues in dementia-related research and might therefore serve as a basis to improve the ethical conduct of this research. This systematic review aims to provide a broad and unbiased overview of ethical issues in dementia research by reviewing, analysing, and coding the latest literature on the topic.

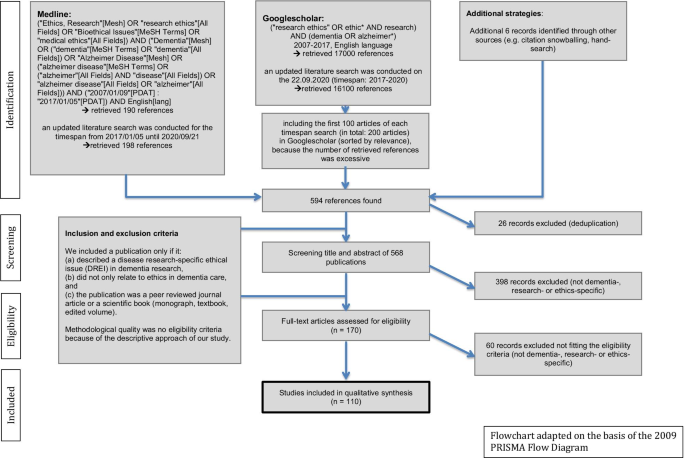

We conducted a systematic review in PubMed and Google Scholar (publications in English between 2007 and 2020, no restrictions on the type of publication) of literature on research ethics in dementia research. Ethical issues in research were identified by qualitative text analysis and normative analysis.

The literature review retrieved 110 references that together mentioned 105 ethical issues in dementia research. This set of ethical issues was structured into a matrix based on the eight major principles from a pre-existing framework on biomedical ethics (Emanuel et al. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. in The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008). Consequently, subcategories were created and further categorized into dementia stages and study phases.

Conclusions

The systematically derived matrix helps raise awareness and understanding of the complex topic of ethical issues in dementia research. The matrix can be used as a basis for researchers, policy makers and other stakeholders when planning, conducting and monitoring research, making decisions on the legal background of the topic, and creating research practice guidelines.

Peer Review reports

Dementia prevalence rates are estimated to quadruple by 2050 [ 1 , 2 ]. Though such forecasts must be interpreted carefully, the global community is likely to face several challenges concerning the individual and familial burdens, societal and political consequences, and economic impact of dementia. With the growing size of the population with dementia, the costs of care are expected to increase in the near future [ 1 ].

The need for research on risk factors [ 2 ], palliative care, and reducing individual psychological burden is therefore of global importance. Research conducted with participants living with dementia raises important ethical questions, such as how to protect cognitively impaired persons against exploitation, how to design informed consent (IC) procedures with proxies, how to disclose risk-factors for dementia given the lack of evidence for their reliability, and how to apply risk–benefit considerations in such cases [ 3 ].

Out of fear of not being able to fulfil the ethical obligations required when conducting research with incapacitated persons, some might suggest the overall exclusion of cognitively impaired persons, or even of all individuals affected by dementia, from research. This caution may lead to the abandonment of meaningful research on dementia and would exclude dementia research from medical progress, leaving affected persons and their relatives orphaned.

Several guidelines [ 4 , 5 ] provide some orientation as to what should be considered to ensure that research on humans is ethical. These guidelines cover the entire research process from planning, conducting, and monitoring the trial to post-trial. Furthermore, they claim specific protection for vulnerable groups and individuals but are not meant to provide details on what that means for dementia research or other patient groups. Many authors have discussed the ethical challenges of dementia research [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. These publications are characterized by a rather narrow focus on certain issues, e.g., on alternatives for obtaining IC [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] or genetic testing [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Some even use a combination of a systematic and a narrative review approach, with the emphasis on identifying differences in the ways ethical issues are addressed [ 21 ]; however, a review of the full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research is still missing in the current literature.

In our systematic review, we therefore aimed to identify the full and unbiased spectrum of research on ethical issues in dementia as discussed in the literature.

Literature search and selection

Three strategies were applied to the literature search: PubMed (database), Google scholar and hand searching methods. We included a publication only if it: (a) described a disease research-specific ethical issue (DREI) in dementia research, (b) did not only relate to ethics in dementia care, and (c) the publication was a peer reviewed journal article or a scientific book (monograph, textbook, edited volume). Methodological quality was no eligibility criteria because of the descriptive approach of our study.

The Flowchart (Fig. 1 ) presents further details on the search algorithm and the eligibility criteria. This approach has already been applied before and can be read in detail elsewhere [ 22 ]. For reference management, we used the programme “Zotero”.

Literature search algorithm adapted on the basis of the 2009 “PRISMA Flow Diagram”

Definition and typology of dementia research-specific ethical issues (DREIs)

For the definition of DREI, we referred to the ethical theory of principlism. Emanuel et al. suggest eight principles that make clinical research ethical: respect for participants, independent review, fair participant selection/recruiting, favourable risk–benefit ratio, social value, scientific validity, collaborative partnership and IC [ 4 ]. These principles represent guiding norms that must be followed in a particular case unless there is a conflict with another obligation that is of equal or greater weight, e.g., alternatives to obtaining IC in special groups or situations. These principles provide only general ethical orientations that require further detail to give guidance in concrete cases. Thus, when applied, the principles must be specified and—if they conflict—balanced against one another.

There are two types of ethical issues that could arise: (a) inadequate consideration of one or more principles (e.g., “risk of insufficiently informing IRBs [institutional review boards] about adequate steps taken to fulfil the ethical obligations of dementia research”) or (b) conflicts between two or more principles (e.g., “challenge of balancing divergent statements in ARD [advance research directive] against current dementia patient wishes or proxy decisions (now vs. then)”). The terms "risk" (a) and "challenge" (b) used in the following refer to this conceptual consideration.

Analysis and synthesis of DREIs

For analysis, we used thematic content analysis [ 23 ] for all 110 included references. To identify and clarify potential ambiguities during content analysis as early as possible a first purposively sampled cluster of references (n = 10) was coded by two reviewers (TG, HK) independently. Another sample of detailed references (n = 9) was coded by one reviewer (TG) only. To capture as many ethical issues as possible this first cluster purposively included more detailed and comprehensive publications. The identified issues were then compared and grouped into the eight principles framework [ 4 ] in a consensus process using a programme for qualitative data analysis (“MAXQDA”). Because the consensus process revealed sufficient clarity for how to deal with ambiguous codings the remaining references (n = 45) were randomly split in half and analysed by one author (HK or TG) only. We updated the search in September 2020 and included another sample of 46 studies. These studies were coded by one author (TG). If further ambiguities during coding occurred they were discussed and clarified in the team.

For synthesis, we used a mixed deductive-inductive approach that takes into account the eight principles and the descriptions from the primary literature. We introduced subcategories if we found it reasonable to do so (for example if the number of DREIs was high). Finally, we used dementia stage and study phase to further categorize the identified issues (see Table 1 ). While we started with the established eight principles for clinical research ethics as a coding framework, our coding procedure was open for DREIs which could not be grouped under one of the eight principles.

References and journals

The literature search in PubMed and Google Scholar revealed a total set of 594 references, 110 of which were ultimately included in the analysis, published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals. For more details, see the flowchart (Fig. 1 ).

Spectrum of dementia research ethical issues (DREIs)

The analysis of the 110 references revealed 105 DREIs. All identified issues could be grouped under one of the eight principles for ethical research, some having far more DREIs than others. In detail, “respect for participants” (n = 11 DREIs), “independent review” (n = 3), “fair participant selection/recruiting” (n = 5), “favourable risk–benefit ratio” (n = 16, 3 subcategories), “social value” (n = 2), “scientific validity” (n = 20, 5 subcategories), “collaborative partnership” (n = 5) and “informed consent (IC)” (n = 43, 12 subcategories). In the course of data analysis, we subsequently found fewer new codes, and the last 10 analysed papers raised no new issues. Thus, we appear to have achieved thematic saturation for the spectrum at least for the level of major groups and first-level subgroups. We updated the search in September 2020 which lead to the analysis of 46 references from the years 2017 until 2020. During the process of literature analysis, only one new subcategory was found in a paper from 2018 [ 24 ], hereafter no new sub-categories have been identified (for the years of 2019 and 2020).

All identified DREIs and subcategories are presented in Table 1 . This table also contains the categorization according to the dementia stage (based on the NIA-AA-2018-Framework) [ 25 ] and the phase of the research for each issue, symbolized by superscript numbers or characters. Additionally, the 105 DREIs are presented in separate tables for each category of dementia stage (Additional file 1 ) and the phase of the research (Additional file 2 ). A full list of the found issues together with the accompanying original text examples as well as the list of all references that were analysed during our systematic review are available in Additional file 3 : Table S3. The above listed tables are available at the supplemental data.

We used the nomenclature of the NIA-AA-2018-framework (“cognitively impaired”, “mild cognitive impairment (MCI)” and “dementia”) [ 25 ] for the first three categories in our dementia stages categorization. Most DREIs were related to more than one dementia stage (category IV, n = 60, Table 1 ). DREIs related to “cognitively unimpaired” (category I, n = 7) centre around the principle of favourable risk–benefit ratio, especially dealing with the sub-categories “determining risk adequately” and “considering risk adequately”, and the principle of respect for participants. No issues were found to fit “mild cognitive impairment” exclusively (category II), where people with dementia are not yet incapacitated. In category III = dementia (n = 11), issues mostly referred to “IC”, especially addressing the sub-category “proxy consent”. Finally, 27 DREIs could not be classified in that split spectrum.

Concerning the categorization due to study phase , we used a timeline approach in naming the different study phases (I = recruiting/pre-trial, II = conduction phase, III = post-trial, IV = general). For DREIs related to specific study phases, again, most DREIs were found to be of overarching relevance (category D, n = 45). In the recruiting/pre-trial phase, DREIs arise within “independent review”, “fair participant selection/recruiting”, “scientific validity”, and “informed consent” (category A, n = 32). While conducting the study (category B, n = 9), DREIs are related to “drop-outs” that endanger scientific validity and the “ongoing assessment” within the principle of informed consent. The post-trial phase is mostly concerned with the principle of respect for participants, communicating the results to the participants and the scientific community (“poor reporting quality”) and adequate follow-up of the volunteers (category C, n = 6). Thirteen issues could not be classified under the topic of study phase .

Specification of general principles for ethical dementia research

All principles for ethical research [ 4 ] were specified in the analysed literature. The references to general principles, such as “IC”, are rather implicit; however, authors elaborate on how the characteristics of dementia lead to specific ethical challenges, e.g., “However, a special ethical issue with regard to longitudinal studies that end in participants’ death is that participants are competent when first recruited, but have a significant likelihood of becoming incompetent while they are study subjects. […] [T]he gradual loss of the capacity to consent […] creates challenges for informed consent, the ethical bedrock of research with human subjects. […][Here], it may make sense to re-evaluate consent capacity […] at several intervals during the study" [ 6 ].

From this statement, the following DREI was paraphrased: “Risk that IC at the beginning of a dementia study alone is insufficient because of cognitive decline of participants”. This DREI is of general relevance for all dementia stages but has particular relevance to the study phase “recruiting/pre-trial”. The full spectrum of issues, including original text examples and all references, is presented in the online supplement (see Additional file 3 ).

Issues which were mentioned the most, are, for example, “Risk of excluding relevant subgroups, e.g. inhabitants of nursing homes, those lacking a proxy/spouse or patients with other psychiatric diseases, from dementia research” (n = 25 papers) and “Risk of excluding participants from research due to lack of capacity to consent” (n = 23). Examples of rarely mentioned DREI are “Risk that dementia patients experiencing stigmatization will lead to low follow-up rates or study withdrawal” (n = 1), “Risk of therapeutic misconception being higher in participants with MCI or mild dementia” (n = 1) and “Risk of RECs [research ethics committees] weighing opinions of physicians (protecting the participant) over patients’ willingness to participate and over nurse counsellors’ opinions” (n = 1).

Several DREIs were only addressed in an implicit manner; for example, “Risk that varying international regulations are a burden for international dementia research” is based on the following quotation: “However, only in Germany and Italy is the system of proxy determined by the courts—a procedure which is not necessarily required for the recognition of a proxy in other member states” [ 26 ].

This systematic literature review identified and synthesized the full spectrum of 105 ethical issues in dementia research (DREIs) based on 110 references published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals.

Many ethical issues involved “IC” (n = 11) in incapacitated participants and “risk-information disclosure” (n = 8). However, this review shows that there are many more DREIs to consider when planning, reviewing, conducting, or monitoring research with this vulnerable group. We assume that the results will be of interest to different groups—clinical experts, researchers, policy makers, REC-members, lawyers, patient-organization representatives or even affected persons themselves—and that the different stakeholders will read and use the results differently.

Our review lists several ethical issues grouped under eight broadly established ethical principles for clinical research. These principles and the principlism approach in general are correlative to basic human rights [ 26 ]. The eight principles are not focused on capacity-based approaches but include approaches to express the right to participate in research via, for examples, advance directives. We would therefore argue, in line with many other ethical analyses based on a principlism approach, that human rights related ethical issues in dementia research are captured directly and indirectly by the many ethical issues addressed in our list of issues. The same applies to other overarching normative concepts such as “avoiding exploitation”. No specified ethical issue in our list mentions the risk of exploitation directly but more or less all specific ethical issues address this risk indirectly. Likewise, the wording “human rights” did not appear explicitly in the literature we analyzed.

Those looking for support or guidance on how to seek ethically appropriate dementia research might prefer detailed descriptions of very specific challenges. Articles such as “Seeking Assent and Respecting Dissent in Dementia Research” by Black et al. [ 9 ] serve this purpose. However, these publications often focus on particular aspects and do not aim to provide a detailed and systematic overview. Further, one also has to do thorough searching and read a large volume of material (we screened n = 594 and finally included n = 110 references) to be familiar with all the aspects discussed in the literature. In contrast to literature addressing very specific DREIs, there are also broad, theoretical frameworks for research ethics, such as that of Emanuel et al. [ 4 ]. However, if capacity building for ethics in dementia research is primarily informed by such general frameworks, it might overlook issues that only become apparent when specifying practice-related tasks. Our review is intended to bridge detailed specifications with a comprehensive and structured presentation of the DREIs at stake.

We illustrate the bridging character of our study by comparing one benchmark for the IC principle originating from Emanuel et al.’s framework [ 4 ] with one issue on our spectrum grouped under “IC” in the subcategory “proxy consent”. The benchmark is “Are there appropriate plans in place for obtaining permission from legally authorized representatives for individuals unable to consent for themselves?” [ 4 ]. A researcher with a specific trial in mind would, in order to conduct morally sound research, perhaps refer to that benchmark in a case where they plans to start a trial on incapacitated patients suffering from dementia. This person would then fulfil that benchmark by making it possible for legal representatives of the patients to fill out the IC document in place of the incapacitated participant. Thus, they would fulfil the benchmark and might not think about more specific ethical problems that might arise when one looks into the literature describing DREI. One such example is this quote stemming from an article on dementia research ethics: “Proxy consent, already an issue of debate in traditional research, was considered more problematic in genetic research, where children share the same genetic traits as their parents. On the one hand, this might be a motivation for the affected parent to participate in a research study to help their children. On the other hand, it was questioned that to what extent children still are able to make a decision in the best interest of their parents because they have an interest themselves. The more genetic research will be carried out, the higher the chance on a disease modifying or preventive therapy for them and their children” [ 14 ].

In that case, and if the researcher had a plan to conduct research in this field of genetic dementia research, the simple fulfilment of the abovementioned benchmark would be insufficient for the goal of morally acceptable research. The mentioned quotation informed the creation of the DREI “Risk of not considering that proxies have major self interest in dementia research, e.g., because they have same genetic traits, which could influence their proxy decision, and their manipulative behaviour may be difficult to detect”.

As we compared topics between both rounds of the literature analysing process, we noticed, that some topics were newly introduced in the scientific literature, in particular “deep brain stimulation” issues in dementia research. Other categories or sub-categories like “social value”, “qualified personnel” and “informed consent document” were not further discussed in scientific literature.

In addition, we found more and more text examples for issues which before the year of 2017 were only mentioned once, e.g. “Risk of over diagnosis in asymptomatic persons, if the diagnosis is derived from the risk marker status, since their corresponding validity regarding the occurrence and course of a disease is (still) limited”, which now was mentioned in six papers.

Also, in the course of the analysis of the studies between 2017 and 2020 we found 22 new issues, among them 17 issues which were only mentioned by one paper showing the rapid emergence of new issues in the dementia research ethics field.

Capturing this full spectrum of DREIs can serve multiple purposes. First, it can raise awareness of the ethical issues arising in the context of dementia research, highlighting issues that may be underrepresented in the published literature through the side-by-side presentation in our matrix. Second, it can serve as the basis for information or training materials for researchers and caregivers. Third, it can form the basis for discussions on the importance and/or relevance of the different ethical issues. Fourth, because our spectrum does not rank the difficult DREIs in order of importance, third parties can use it as a basis for exactly that purpose. Fifth, developers of specific research guidelines or policy papers may use this spectrum as an entry point to that topic.

At this point, it is important to state that our spectrum remains strictly descriptive. The qualitative and normative interpretation is therefore left to others, e.g., researchers, policy-makers, patient organizations, funding partners and the community as a whole. Those interpretations could further help in developing stakeholder-oriented guidelines for conducting ethically sound research in dementia. The list of ethical issues as presented in this paper, however, cannot directly serve as a checklist for review purposes. More conceptual work is needed to translate the in-depth results of this systematic review into effective and efficient normative or procedural guidance. Finally, existing guidelines, policy papers or new research articles on the topic of DREIs can be screened for completeness [ 27 ].

To make the results of the review more concise and accessible, we prepared overviews sorted by stage and phase (available as an online supplement). This is particularly suitable for readers who have a certain focus, e.g., because they are currently planning a study with people in an early stage of dementia (see Additional file 1 ) or are looking for an overview of DREIs in the phase of conducting the study (see Additional file 2 ). These tables show that ethical issues are situation-sensitive, e.g., certain questions on informed consent only arise at a later stage of the disease, while questions of reporting the status of risk factors are only relevant in early stage (pre-symptomatic) patients.

One limitation of this systematic review is that the search was limited to PubMed and Google Scholar. We do not consider this an overly disadvantageous factor and consider the approach to be appropriate for the following reasons: First, our search resulted in the identification of literature from different fields, not only from the bioethics and medicine field but also spanning nursing research [ 28 , 29 ], nursing ethics [ 30 , 31 ], a narrative review [ 3 ] and even one systematic review [ 21 ]. This systematic review by West et al. covered mostly literature concerning IC, advance directives and the role of proxies or surrogates. Second, thematic saturation for the first-level categories was achieved after analysing 54 of the 64 papers that were included after the first literature search in these two data sources. For the updated literature search, which only found one new first-level category, thematic saturation was achieved after analysing 25 of the 46 papers. Third, former systematic reviews [ 32 , 33 ] in the bioethics field, which based their research on additional databanks such as EMBASE, CINAHL or Euroethics, found few additional references. Another limitation is that we only reviewed the literature from the last 14 years. However, we included two (systematic) reviews, which included literature dating back to 1982 [ 3 ] and back to 1995 [ 21 ]. We further assume that an important ethical issue that was mentioned 15 years ago and that is still relevant nowadays would be addressed in some more recent references again.

Further, we only included references in the English language. Some culturally sensitive DREI might be preferably discussed in the respective language, and our review might have missed those discussions. Last but not least, we only included peer-reviewed literature and thus did not consider grey literature such as guidelines from advocacy organizations involved with dementia research [ 34 , 35 ]. As a future project, we aim to employ the results of our review to analyse whether and how guidelines for dementia research mention the identified issues. For a similar approach see the results of a systematic review of ethical issues in dementia care [ 22 ] that was followed-up by a content analysis of clinical practice guidelines for dementia care [ 27 ].

The authors of this review have different scientific backgrounds: medicine/psychiatry, physiotherapy, public health, ethics and philosophy. However, all authors are currently involved neither in clinical research nor in health care for people with dementia. However, we do not consider this to be a weakness of the review, as we have included these perspectives in the literature considered, e.g., expert opinions [ 9 , 10 , 14 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], views of patients, caregivers and proxies [ 11 , 28 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ], papers focusing on legal and ethical guidelines [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 ], and the point of view of lay persons [ 13 ]. Our review found no papers on the opinions and views of relatives of people living with dementia. This might indicate the need for further research in that field.

This study has successfully shown that a systematic literature review leads to a wider spectrum of DREIs (n = 105) than other papers on the subject. The identified issues are specifications of eight general ethical principles for clinical research and could be categorized according to the dementia stage and study phase. Therefore, the spectrum can be used to raise awareness about the complexity of ethics in this field and can support different stakeholders in the implementation of ethically appropriate dementia research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Dementia research-specific ethical issue(s)

Informed consent

Institutional review board(s)

Advanced research directives

Tim Götzelmann

Hannes Kahrass

Mild cognitive impairment

Research ethics committee(s)

Daniel Strech

Randomized controlled trial(s)

European union

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

Mini-Mental State Examination

Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, Prince M, Winblad B, International AD. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1–11.

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75.

Article Google Scholar

Johnson RA, Karlawish J. A review of ethical issues in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(10):1635–47.

Emanuel EJ, Grady CC, Crouch RA, Lie RK, Miller FG, Wendler DD. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. In: The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics. Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 123–35.

WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ .

Davis DS. Ethical issues in Alzheimer’s disease research involving human subjects. J Med Ethics. 2017; medethics—2016.

Sherratt C, Soteriou T, Evans S. Ethical issues in social research involving people with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6(4):463–79.

van der Vorm A, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Kehoe PG, Rikkert MGMO, van Leeuwen E, Dekkers WJM. Ethical aspects of research into Alzheimer disease. A European Delphi Study focused on genetic and non-genetic research. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(2):140–4.

Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J, Karlawish JH. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):77–85.

Dubois M-F, Bravo G, Graham J, Wildeman S, Cohen C, Painter K, et al. Comfort with proxy consent to research involving decisionally impaired older adults: do type of proxy and risk–benefit profile matter? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(09):1479–88.

Karlawish J, Kim SYH, Knopman D, van Dyck CH, James BD, Marson D. The views of alzheimer disease patients and their study partners on proxy consent for clinical trial enrollment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):240–7.

Kim SYH. The ethics of informed consent in Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(7):410–4.

Kim SYH, Kim HM, Knopman DS, De Vries R, Damschroder L, Appelbaum PS. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward surrogate consent for dementia research.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/77/24/2097.short .

Olde Rikkert MG, van der Vorm A, Burns A, Dekkers W, Robert P, Sartorius N, et al. Consensus statement on genetic research in dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(3):262–6.

SYH Kim, J Karlawish, BE Berkman. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/84/14/1488.short .

Arribas-Ayllon M. The ethics of disclosing genetic diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: do we need a new paradigm? Br Med Bull. 2011;100(1):7–21.

Chao S, Roberts JS, Marteau TM, Silliman R, Cupples LA, Green RC. Health behavior changes after genetic risk assessment for Alzheimer disease: the REVEAL study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):94–7.

Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Uhlmann WR, Green RC. Changes to perceptions of the pros and cons of genetic susceptibility testing after APOE genotyping for Alzheimer disease risk. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):409–14.

Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Brown T, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):245–54.

Salmon D, Lineweaver T, Bondi M, Galasko D. Knowledge of APOE genotype affects subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2012;8(4):P123–4.

West E, Stuckelberger A, Pautex S, Staaks J, Gysels M. Operationalising ethical challenges in dementia research—a systematic review of current evidence. Age Ageing. 2017;1–10.

Strech D, Mertz M, Knuppel H, Neitzke G, Schmidhuber M. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: systematic qualitative review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(6):400–6.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Companion Qual Res. 2004;1:159–76.

Google Scholar

Thorogood A, Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen A, Brodaty H, Dalpé G, Gastmans C, Gauthier S, et al. Consent recommendations for research and international data sharing involving persons with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(10):1334–43.

Jack Cr, Da B, K B, Mc C, B D, Sb H, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 24]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29653606/ .

Gainotti S, Imperatori SF, Spila-Alegiani S, Maggiore L, Galeotti F, Vanacore N, et al. How are the interests of incapacitated research participants protected through legislation? An Italian study on legal agency for dementia patients. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11150.

Knüppel H, Mertz M, Schmidhuber M, Neitzke G, Strech D. Inclusion of ethical issues in dementia guidelines: a thematic text analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001498.

Hanson LC, Gilliam R, Lee TJ. Successful clinical trial research in nursing homes: the improving decision-making study. Clin Trials Lond Engl. 2010;7(6):735–43.

Garand L, Lingler JH, Conner KO, Dew MA. Diagnostic labels, stigma, and participation in research related to dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(2):112–21.

Heggestad AKT, Nortvedt P, Slettebø Ashild. The importance of moral sensitivity when including persons with dementia in qualitative research. Nurs Ethics. 2012;0969733012455564.

Slaughter S, Cole D, Jennings E, Reimer MA. Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(1):27–40.

Sofaer N, Strech D. Reasons why post-trial access to trial drugs should, or need not be ensured to research participants: a systematic review. Public Health Ethics. 2011;4(2):160–84.

Strech D, Persad G, Marckmann G, Danis M. Are physicians willing to ration health care? Conflicting findings in a systematic review of survey research. Health Policy. 2009;90(2):113–24.

Europe A. Overcoming ethical challenges affecting the involvement of people with dementia in research: recognising diversity and promoting inclusive research. Luxemb Alzheimer Eur. 2019.

Alzheimer E. Alzheimer Europe Report: The ethics of dementia research: Alzheimer Europe; 2011. 2011.

Schicktanz S, Schweda M, Ballenger JF, Fox PJ, Halpern J, Kramer JH, et al. Before it is too late: professional responsibilities in late-onset Alzheimer’s research and pre-symptomatic prediction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:921.

Molinuevo JL, Cami J, Carné X, Carrillo MC, Georges J, Isaac MB, et al. Ethical challenges in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease observational studies and trials: Results of the Barcelona summit. Alzheimers Dement [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2016 Apr 21]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1552526016000765 .

Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, et al. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimers Res Ther [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2017 Jan 6];7(1). Available from: http://alzres.com/content/7/1/26 .

Werner P, S S. Practical and Ethical Aspects of Advance Research Directives for Research on Healthy Aging: German and Israeli Professionals’ Perspectives [Internet]. Frontiers in medicine. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29675415/ .

Cary MS, Rubright JD, Grill JD, Karlawish J. Why are spousal caregivers more prevalent than nonspousal caregivers as study partners in AD dementia clinical trials? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(1):70–4.

Hellström I, Nolan M, Nordenfelt L, Lundh U. Ethical and Methodological Issues in Interviewing Persons With Dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(5):608–19.

Overton E, Appelbaum PS, Fisher SR, Dohan D, Roberts LW, Dunn LB. Alternative decision-makers’ perspectives on assent and dissent for dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):346–54.

Grill Jd, Cg C, K H, J K. Reactions to learning a “not elevated” amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial [Internet]. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30579361/ .

Hosie A, S K, N R, I G, D P, C S, et al. Older Persons’ and Their Caregivers’ Perspectives and Experiences of Research Participation With Impaired Decision-Making Capacity: A Scoping Review [Internet]. The Gerontologist. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32866239/ .

Jongsma K, J P, S S, K R. Motivations for people with cognitive impairment to complete an advance research directive—a qualitative interview study [Internet]. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32641010/ .

Mann J, Hung L. Co-research with people living with dementia for change. Action Res. 2019;17(4):573–90.

Morbey H, Harding AJ, Swarbrick C, Ahmed F, Elvish R, Keady J, et al. Involving people living with dementia in research: an accessible modified Delphi survey for core outcome set development. Trials. 2019;20(1):1–10.

Ries N, E M, R S-F. Planning Ahead for Dementia Research Participation: Insights from a Survey of Older Australians and Implications for Ethics, Law and Practice [Internet]. Journal of bioethical inquiry. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31297689/ .

Robillard JM, Feng TL. When patient engagement and research ethics collide: lessons from a dementia forum. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(1):1–10.

Jongsma K, Bos W, van de Vathorst S. Morally relevant similarities and differences between children and dementia patients as research subjects: representation in legal documents and ethical guidelines: children and dementia patients as research subjects. Bioethics. 2015;29(9):662–70.

Alpinar-Sencan Z, S S. Addressing ethical challenges of disclosure in dementia prediction: limitations of current guidelines and suggestions to proceed [Internet]. BMC Medical Ethics. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32393330/ .

Fletcher JR, Lee K, Snowden S. Uncertainties when applying the mental capacity act in dementia research: a call for researcher experiences. Ethics Soc Welf. 2019;13(2):183–97.

Gove D, Diaz-Ponce A, Georges J, Moniz-Cook E, Mountain G, Chattat R, et al. Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):723–9.

Ries NM, Thompson KA, Lowe M. Including people with dementia in research: an analysis of Australian ethical and legal rules and recommendations for reform. J Bioethical Inq. 2017;14(3):359–74.

Thorogood A, Dalpe G, McLauchlan D, Knoppers B. Canadian consent and capacity regulation: undermining dementia research and human rights. McGill J Law Health. 2018;12:67.

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease .

Food and Drug Administration. Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industy [Internet]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/alzheimers-disease-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industy .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special gratitude to Marcel Mertz for his critical review of the categorization and paraphrasing of the issues. His expertise was used to confirm the validity of the final spectrum.

Not applicable.

Author information

Tim G. Götzelmann and Hannes Kahrass have contributed equally to this work

Authors and Affiliations

Institute for History, Ethics and Philosophy in Medicine, OE 5450, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625, Hannover, Germany

Tim G. Götzelmann & Hannes Kahrass

QUEST Center, Berlin Institute of Health, Anna-Louisa-Karsch-Straße 2, 10178, Berlin, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TG had a major role in the acquisition of data, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. DS had a major role in the design and conceptualization of the study and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. HK analysed the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tim G. Götzelmann .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. table s1.

: An overview of the 105 DREIs assigned to dementia stages.

Additional file 2. Table S2

: An overview of the 105 DREIs assigned to study phases.

Additional file 3. Table S3

: All principles, issues and text examples in one table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Götzelmann, T.G., Strech, D. & Kahrass, H. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research: findings of a systematic qualitative review. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 32 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00572-5

Download citation

Received : 20 May 2020

Accepted : 21 December 2020

Published : 26 March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00572-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical ethics

- Research ethics

- Dementia research

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Dementia: Your Questions Answered

November 25, 2019

We rely on memory to get and keep meaning from life. That may be why even small lapses, like misplacing car keys or forgetting a doctor’s appointment, can lead to anxiety about our brain health. In fact, about half of U.S. adults between ages 50 to 64 worry they will develop dementia, along with the severe memory loss and cognitive confusion that come with it, according to a recent national poll.

For now, though, the fear of developing dementia outpaces the number of diagnoses. Overall, about 14% of U.S. men and women older than 71 have some form of dementia. But those numbers will likely increase as the baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) grow older.

Dementia is not part of the normal aging process; instead, it’s a symptom of an underlying brain disease. Alzheimer’s disease causes between 60 and 80% of all dementia cases in this country, meaning that about one in 10 Americans ages 65 or older currently lives with it. The remaining cases could be caused by more than a dozen other neurological conditions, including four common types of dementia: vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, and mixed.

“Alzheimer’s is a heart-breaking disease,” says Yale Medicine’s Christopher van Dyck, MD , a geriatric psychiatrist who conducts research in the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Unit and provides clinical care in the Dorothy Adler Geriatric Assessment Center.

Those with Alzheimer’s disease and other memory disorders may show frustration at being unable to express a deep, inner confusion of jumbled thoughts. They may not know how they arrived somewhere, or how to get back home. As the disease progresses, their loved ones might turn into unrecognizable strangers. A person will reach a point where he or she is incapable of communicating coherently.

Dr. van Dyck witnessed both of his maternal grandparents suffer through Alzheimer’s disease during visits home as a medical school student. That experience, combined with an interest in neuroscience, led him to study the disease and specialize in treating patients with it. Dr. van Dyck provided answers to some frequently asked questions about dementia. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is dementia?

Dementia is a decline in cognitive function that impairs daily living, to a point where a person is no longer independent. But it’s important to note that dementia is a syndrome, or a group of symptoms. Alzheimer’s is a disease and the leading cause of dementia. It’s similar to asking what knee pain is. Knee pain is a symptom that can be caused by different things, like osteoarthritis .

Other leading types of dementia are frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and vascular dementia, and there are many others that are much less common. Doctors are able to tell with general probability what is causing the dementia, but a definitive answer is possible only with a brain autopsy.

Why does dementia occur?

Alzheimer’s is far and away the leading cause—it accounts for about two-thirds of all late-onset dementia [which generally affects people after the age of 65]. Other disorders and diseases account for the rest. And why Alzheimer’s disease occurs is an unending and, perhaps, philosophical question. For example, you could ask, “What are the changes in the brain that precede and are associated with the onset of symptoms?” But then you would also have to ask why those occur. And so on. You could also ask: "What predisposes certain people to get Alzheimer’s disease?" The greatest risk factor is age. Among U.S. men and women ages 65 to 75, about 3% have Alzheimer’s; for ages 75 to 85, between 10 to 15% live with the disease; and for those older than 85, approximately 35% have it.

So, why is age a risk factor? We don’t fully know—and that’s a big area of current research. The second most important risk factor is family history and genetics: The major genetic risk factor is called apolipoprotein E4 [APOE4], which might account for up to 40% of the risk. But why is APOE4 a risk factor? Again, we don’t fully know. A nonhereditary risk factor is previous head injuries. And, of course, there is much ongoing research about lifestyle, including diet and exercise. So, there’s not a clear-cut answer on why dementia occurs.

How does dementia affect the brain?

It depends on the cause of dementia. With Alzheimer’s, it affects the brain by causing neurodegeneration—or damage and death to specific brain cells in specific parts of the brain—that then spreads over time. We also see a loss of synapses [or connections] in the brain that occurs out of proportion to the death of those brain cells. The leading view of Alzheimer’s is that it’s related to the formation of amyloid protein in the brain, but that is disputed. There are other changes happening, such as tau protein deposits, called tau tangles. Even if you believe the amyloid protein hypothesis, then you can ask why do the protein buildups occur [in the first place]? We don’t fully know.

How is dementia diagnosed?

Dementia—as the syndrome—is diagnosed by a clinical assessment of the person to see if he or she has a decline in cognitive ability and activities of daily living, sufficient to have a loss of independence. This is done through cognitive testing and interviews with the family. They might ask how the person manages with driving a car or getting dressed. Once you establish that a person has dementia or a lower-level cognitive disorder, then you try to determine the cause through a medical evaluation, and that includes physical and neurological examinations, as well as blood tests and brain imaging, which would be MRI or PET scans.

Those tests largely rule out other medical causes of dementia. However, for “ruling in” Alzheimer’s disease, we look at specialized biomarker studies, such as an amyloid PET scan (to look for amyloid deposits in the brain) or a lumbar puncture (to look for alterations in levels of such fluid proteins as amyloid and tau. Amyloid PET scans are not reimbursed by insurance and probably won’t be until we have a specific and significant treatment to offer based on the results. Blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease are making great progress, though, and may be available—at least as screening tests—in a few years.

What kind of doctor treats dementia?

In general, dementia and Alzheimer’s could be initially diagnosed by a primary care doctor, who is able to take the time for a full evaluation. There are specialists, such as neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, or geriatric internists, who can provide more definitive diagnoses and develop detailed treatment plans for patients. For the diagnosis of dementia, neuropsychologists also play a key role, though they are not usually involved in the actual treatment of the disease. If a patient has a confusing presentation of symptoms, a neuropsychologist can be very useful in establishing that a cognitive abnormality exists and in distinguishing between the different types of disease.

How should one approach care for a dementia patient?

That’s a very broad question that really depends on the cause of the dementia, the stage of dementia, and the individual circumstances of the person and his or her family. Not everyone is the same. In Alzheimer’s disease, once a diagnosis is made, the early care is usually focused on starting medications (cholinesterase inhibitors, like donepezil) to address symptoms, plus antidepressants for depression, if necessary. The early care is also focused on helping the family set expectations for the future so they can address any legal and financial planning concerns. Driving safety may also need to be formally evaluated.

As the disease progresses, the care may involve more assistance with activities of daily living, such as eating and dressing. Home care, which has the added benefit of alleviating burden on the spouse and other family members, can be helpful at this stage. We may consider other medications such as memantine [that may help with memory and learning], which may be appropriate in the moderate stages of disease, or other psychotropic medications for specific behaviors, such as agitation. In the later stages of the disease, all of the above continues, but the care may also be focused on considering alternative living arrangements, such as assisted living, a memory care unit, nursing home placement, or hospice care. But, with appropriate services in place, many people with Alzheimer’s disease are able to live at home to the very end.

Can dementia lead to death?

This is a bit of a semantic question. Dementia doesn’t cause death. But the life expectancy of a person with Alzheimer’s is about 10 years on average, from the very earliest symptoms to death, and it does vary. So, it shortens life expectancy, but the immediate causes are likely to be things like pneumonia, dehydration, or falls. Neurodegenerative causes of dementia—like Alzheimer’s disease—shorten life expectancy more than vascular diseases that cause dementia—individuals with vascular dementia can be fairly stable over time.

Can dementia be prevented?

Again, it depends on the cause. If we are talking about Alzheimer’s disease, we don’t currently have a program or intervention for preventing it. You can prevent head injuries, and maybe reduce some risk. But you cannot prevent the biggest risk factor—aging. You cannot alter family history and genetics—at least, not yet. One of the big areas of research interest is lifestyle choices, like eating well and exercising. Aerobic exercise and Mediterranean diets, with an emphasis on fruits and vegetables and limited carbohydrates, are associated with a lower risk. But we don’t have studies that prove this. However, we are currently conducting randomized controlled trials on the effects of both aerobic exercise ( EXERT study ) and specialized diets. I don’t think we expect these things to prevent dementia, but they could help to lower the risk. There are also ongoing therapeutic trials that attempt to lower the risk of Alzheimer’s by, for example, lowering brain amyloid levels. So far, nothing has been proven to work, but this is an area of intense research, and I remain very hopeful.

To learn more about the Dorothy Adler Geriatric Assessment Center, click here.

More news from Yale Medicine

- Our work Strategic Plan 2024 Work Plan Current work Past work Partners Anti-Stigma Award Anti-Stigma initiatives Publications

- Dementia Alzheimer's dementia Other dementias Prevalence of dementia

- Research Understanding research Public involvement Clinical trials Research projects

- Policy Our campaigns EU action National dementia strategies Global action European Alzheimer’s Alliance Past supporters Members Policy positions

- Resources Reports & Publications Intercultural support Ukraine resources

- Conferences 2024 Geneva Past conferences Other events

- About us Who we are Members Board Staff Expert Advisory Panel European Working Group of People with Dementia Members Membership Past members European Dementia Carers Working Group Members Membership Governance Statutes Rules and Regulations Finances Operating policies Alzheimer Europe Foundation Board of Directors Statutes Activities and finances

Questions to ask about research

The kind of study and the goals of the researchers will determine to a large extent what is expected of participants. However, irrespective of the precise nature of the study, the researchers will have a clear plan of what they want to do, how, when and for how long. This is called the research protocol. These issues should have been discussed with participants and informed consent obtained prior to the start of the study. However, in order to give informed consent, participants must have received and understood all the relevant information linked to the proposed study. It is the researchers’ responsibility to provide such information and to ensure that participants have understood it. Participants are free to ask for further clarification and information, and should be encouraged to do so. The following box contains examples of questions that people might want to consider asking before consenting to take part in research.

Purpose of the research

- Why is this study/trial being conducted?

- What do the researchers hope to discover?

- What is involved (e.g. hospital stays, visits to the doctor, injections, blood tests and scans etc.)?

- Is any of this likely to be stressful, uncomfortable, burdensome or painful?

- What is the likelihood that I will receive the experimental drug (in the case of clinical trials)?

- How long will the study/trial last?

- Where will I have to go and how often?

Benefits and risks

- Are there any benefits or risks involved in this study?

- Am I likely to benefit personally from participating in this study?

- Will I be provided with support if I have difficulty understanding all the information provided?

- Will I still be able to participate in research if I am considered unable to provide informed consent?

- What are my treatment or care options if I decide not to participate in this study?

- Can I withdraw at any time?

- Will my wish to withdraw be respected even if I am considered as lacking decision-making capacity at the time?

Continuing care

- How will participation in this study/trial affect my current care?

- How will participation in this study/trial affect my future care?

- What are the likely side effects, if any?

- What will happen if I experience side effects?

- What will happen if the researchers notice something abnormal in the information they collect about me that is not directly linked to their study but relevant to my health?

- If anything goes wrong, would I be covered by some kind of insurance?

- Who is responsible for the safety and wellbeing of participants?

- Whom can I contact in case of emergency or if I wish to complain?

Confidentiality

- Who will be informed that I am participating in this study?

- Who will know whether I am receiving an experimental drug?

- Will personal information about me be kept on a computer or in a report?

- Will I have access to information that is collected about me?

- If so, will my anonymity be respected?

- Would I be bound to secrecy in any way?

- How will the results of the study be presented and used?

- Will anyone see my name and information about me in the reports of the research findings or will it all be anonymous?

- Will I be informed of the results of the study afterwards?

- Is there any payment to compensate participants for their time and effort?

- Are travel costs and other related expenses covered?

- Does anyone receive compensation of any kind for my participation in the study?

Restrictions

- Is there anything I should or shouldn’t do during the study?

- Can I also take authorised drugs for dementia during the study?

- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan