Don't make ads, make TikTok’s: media and brand engagement through Gen Z's use of TikTok and its significance in purchase intent

- Original Article

- Published: 18 May 2023

- Volume 30 , pages 535–549, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Jose A. Flecha Ortiz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9626-5967 1 ,

- María De Los M. Santos Corrada 2 , 3 ,

- Evelyn Lopez 1 ,

- Virgin Dones 1 &

- Vivian Feliberty Lugo 1

3107 Accesses

Explore all metrics

New social media platforms, such as TikTok, are characterized by dynamic content that provides Generation Z users with a sense of connection and higher engagement rates than other social media platforms. The particularities of Generation Z as consumers have changed the way brands look for ways to drive engagement and forms of interaction on social networks (SNS). This article proposes a model to analyze the passive use of TikTok, and how it impacts the media engagement in users of Generation Z. In addition, it analyzes how media engagement impacts brand engagement through affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Finally, we present how these variables affect purchase intention. The results reflect that the motivations for interactivity and the drivers of those motivations significantly impact consumer engagement and that perceptual psychology plays a determining role in achieving engagement with the medium. The study identified that once engagement with the brand occurs, interactivity plays an active role in decision-making. This study makes significant contributions to the literature on consumer engagement and marketing management.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An Investigation into the Driving Mechanisms of Consumer Engagement

Social Media Engagement Through Video Advertising: Informativeness and Self Brand Connection as Predictors

Consumer Behavior on Social Media: A Thematic Exploration and an Agenda for Future Inquiry

Achterberg, W., A.M. Pot, A. Kerkstra, M. Ooms, M. Muller, and M. Ribbe. 2003. The effect of depression on social engagement in newly admitted Dutch nursing home residents. The Gerontologist 43(2): 213–218.

Article Google Scholar

Adcock, R. 2001. Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American Political Science Review 95(03): 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055401003100 .

Alalwan, A.A. 2018. Investigating the impact of social media advertising features on customer purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management 42(42): 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.06.001 .

Algesheimer, R., U.M. Dholakia, and A. Herrmann. 2005. “The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing 69(3): 19–34.

Aluri, A., L. Slevitch, and R. Larzelere. 2015. The Influence of Embedded Social Media Channels on Travelers’ Gratifications, Satisfaction, and Purchase Intentions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 57(3): 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515615685 .

Andreassen, C.S., S. Pallesen, and M.D. Griffiths. 2017. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors 64(64): 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006 .

Arghashi, V., and C. Arsun Yuksel. 2022. Customer brand engagement behaviors: The role of cognitive values, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and self-brand connection. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice . https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2021.2018936 .

Bailey, A.A., C.M. Bonifield, and J.D. Elhai. 2021. Modeling consumer engagement on social networking sites: Roles of attitudinal and motivational factors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102348 .

Barger, V., J.W. Peltier, and D.E. Schultz. 2016. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 10(4): 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-06-2016-0065 .

Bazi, S., R. Filieri, and M. Gorton. 2020. Customers’ motivation to engage with luxury brands on social media. Journal of Business Research 112: 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.032 .

Bilro, R.G., and S.M.C. Loureiro. 2020. A consumer engagement systematic review: Synthesis and research agenda. Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC 24(3): 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/sjme-01-2020-0021 .

Boyd, D. 2010. Streams of Content, Limited Attention: The Flow of Information through Social Media. EDUCAUSE Review 45(5): 26–28.

Google Scholar

Brodie, R.J., A. Ilic, B. Juric, and L. Hollebeek. 2013. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research 66(1): 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.029 .

Bucknell Bossen, C., and R. Kottasz. 2020. Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consumers . https://doi.org/10.1108/yc-07-2020-1186 .

Calder, B. J., & Malthhouse, E. C. (2018). Media engagement and advertising effectiveness. In K. Johnston & M. Taylor (Eds.), In B. J. Calder (Ed.), Kellogg on advertising & media (pp. 1–36). Wiley.

Calder, B.J., and E.C. Malthouse. 2004. Qualitative media measures: Newspaper experiences. International Journal on Media Management 6(1–2): 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2004.9669388 .

Castillo, A., J. Benitez, J. Llorens, X. Luo, and (Robert). 2021. Social media-driven customer engagement and movie performance: Theory and empirical evidence. Decision Support Systems . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2021.113516 .

Chahal, H., J. Wirtz, and A. Verma. 2020. Social media brand engagement: dimensions, drivers and consequences. Journal of Consumer Marketing . https://doi.org/10.1108/jcm-11-2018-2937 .

Chi, H.-H. 2011. Interactive digital advertising vs. virtual brand community. Journal of Interactive Advertising 12(1): 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2011.10722190 .

Cho, M., M. Bonn, and S. Han. 2018. Generation Z’s sustainable volunteering: Motivations. Attitudes and Job Performance. Sustainability 10(5): 1400–1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051400 .

Chua, T.H.H.H., and L. Chang. 2016. Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior 55(8): 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011 .

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1997. Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life . Basic Books.

De Vries, N., and J. Carlson. 2014. Examining the drivers and brand performance implications of customer engagement with brands in the social media environment. Journal Brand Managment 21: 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.18 .

Di Gangi, P.M., and M.M. Wasko. 2016. Social media engagement theory: Exploring the influence of user engagement on social media usage. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing 28(2): 53–73. https://doi.org/10.4018/joeuc.2016040104 .

Dienlin, T. 2020. The impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 22(2): 135–142.

Djafarova, E., and T. Bowes. 2021. “Instagram made Me buy it”: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345 .

Erz, A., B. Marder, and E. Osadchaya. 2018. Hashtags: Motivational drivers, their use, and differences between influencers and followers. Computers in Human Behavior 89: 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.030 .

Evans, D., M. Jake, and B. Susan. 2010. Social media marketing: The next generation of business engagement . Wiley.

Feng, Y.-L., C.-C. Chen, and S.-M. Wu. 2019. Evaluation of charm factors of short video user experience using FAHP-a case study of Tik Tok APP. IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering 688(5): 055068. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/688/5/055068 .

Florenthal, B. 2019. Young consumers’ motivational drivers of brand engagement behavior on social media sites. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 13(3): 351–391. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-05-2018-0064 .

Fournier, S. 1998. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research 24(4): 343–353.

France, C., B. Merrilees, and D. Miller. 2016. An integrated model of customer-brand engagement: Drivers and consequences. Journal Brand Managment 23: 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2016.4 .

Gentina, E., and F. Rowe. 2020. Effects of materialism on problematic smartphone dependency among adolescents: The role of gender and gratifications. International Journal of Information Management . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102134 .

Gerson, J., A.C. Plagnol, and P.J. Corr. 2017. Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the reinforcement sensitivity theory. Personality and Individual Differences 117: 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.034 .

Gibson, J.G. 1986. The ecological approach to visual perception . Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gibson, J.J. 2015. The ecological approach to visual perception . Psychology Press.

Goldfarb, A., R.C. McDevitt, S. Samila, and B.S. Silverman. 2015. The effect of social interaction on economic transactions: Evidence from changes in two retail formats. Management Science 61(12): 2963–2981. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2030 .

Hair, J.F., M.C. Howard, and C. Nitzl. 2020. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research 109: 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069 .

Hair, J.F., T. Hult, C. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2021. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) , 3rd ed. New York.

Book Google Scholar

Hair, J.F., M. Sarstedt, C. Ringle, and S. Gudergan. 2018. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling . Sage.

Harmeling, C.M., J.W. Moffett, M.J. Arnold, and B.D. Carlson. 2016. Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45(3): 312–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0509-2 .

Harrigan, P., T.M. Daly, K. Coussement, J.A. Lee, G.N. Soutar, and U. Evers. 2021. Identifying influencers on social media. International Journal of Information Management . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102246 .

Heckathorn, D. 1997. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems 44(2): 174–199. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1997.44.2.03x0221m .

Henseler, J., C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1): 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 .

Henseler, J., C.M. Ringle, and R.R. Sinkovics. 2009. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing 20: 277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1474-7979(2009)0000020014 .

Henzel, V., and A. Håkansson. 2021. Hooked on virtual social life. Problematic social media use and associations with mental distress and addictive disorders. PLOS ONE 16(4): e0248406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248406 .

Hollebeek, L.D. 2011. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. Journal of Marketing Management 27(7–8): 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2010.500132 .

Hollebeek, L.D., and K. Macky. 2019. Digital content marketing’s role in fostering consumer engagement, trust, and value: Framework, fundamental propositions, and implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing 45(1): 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.07.003 .

Hollebeek, L.D., M.S. Glynn, and R.J. Brodie. 2014. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 28(2): 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.12.002 .

IDEPR (2021) Censo PR . Retrived https://censo.estadisticas.pr/EstimadosPoblacionales

Iqbal, M. (2021). TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2021) . Business of Apps. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/

Ismail, A.R., B. Nguyen, J. Chen, T.C. Melewar, and B. Mohamad. 2020. Brand engagement in self-concept (BESC), value consciousness and brand loyalty: A study of generation Z consumers in Malaysia. Young Consumers . https://doi.org/10.1108/yc-07-2019-1017 .

Jaakkola, E., and M. Alexander. 2014. The role of customer engagement behavior in value co-creation: A service system perspective. Journal of Service Research 17(3): 247–261.

Jones, A.R., S.-E. Lee, and (Joy). 2021. Factors influencing engagement in fashion Brands’ instagram posts. Fashion Practice 14(1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2021.1938820 .

Kartajaya, H., I. Setiawan, and P. Kotler. 2021. Marketing 5.0: Technology for humanity . Wiley.

Kearsley, G., and B. Shneiderman. 1998. Engagement theory: A framework for technology-based teaching and learning. Educational Technology 38(5): 20–23.

Kettinger, W.J., and C.C. Lee. 1994. Perceived service quality and user satisfaction with the information services function. Decision Sciences 25(5–6): 737–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1994.tb01868.x .

Khan, I., L.D. Hollebeek, M. Fatma, J.U. Islam, and Z. Rahman. 2020. Brand engagement and experience in online services. Journal of Services Marketing 34(2): 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsm-03-2019-0106 .

Khan, M.L. 2017. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Computers in Human Behavior 66: 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024 .

Klein, A., and V.M. Sharma. 2022. Consumer decision-making styles, involvement, and the intention to participate in online group buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 64: 102808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102808 .

Kumar, V., L. Aksoy, B. Donkers, R. Venkatesan, T. Wiesel, and S. Tillmanns. 2010a. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research 13(3): 297–310.

Kumar, V., L. Aksoy, B. Donkers, R. Venkatesan, T. Wiesel, and S. Tillmanns. 2010. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research 13(3): 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375602 .

Kumar, V., I. Khan, M. Fatma, and A. Singh. 2022. Engaging luxury brand consumers on social media. Journal of Consumer Marketing 39(1): 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcm-10-2020-4175 .

Lee, C.-H., and J.J. Wu. 2017. Consumer online flow experience. Industrial Management & Data Systems 117(10): 2452–2467. https://doi.org/10.1108/imds-11-2016-0500 .

Leftheriotis, I., and M.N. Giannakos. 2014. Using social media for work: Losing your time or improving your work? Computers in Human Behavior 31: 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.016 .

Lontoh, C.N., F.A. Suyuthi, and J.N.I.C. Sagala. 2022. Engagement behavior generation Z on TikTok case study: Cosmetic brands. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute (BIRCI-Journal) Humanities and Social Sciences 5(2): 10092–10101.

Magnani, R., K. Sabin, T. Saidel, and D. Heckathorn. 2005. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS 19: S67–S72.

Malhotra, N.K. 2020. Marketing research: An applied orientation . England Pearson.

Mangold, W.G., and D.J. Faulds. 2009. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business Horizons 52(4): 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002 .

Marwick, A., and D. Boyd. 2011. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience-Alice E. Marwick, Danah Boyd, 2011. New Media & Society 13(1): 4458.

Medium (2020). How TikTok Is Addictive . Medium. https://medium.com/dataseries/how-tiktok-is-addictive-1e53dec10867

Molina-Prados, A., F. Muñoz-Leiva, and M.B. Prados-Peña. 2021. The role of customer brand engagement in the use of Instagram as a “shop window” for fashion-industry social commerce. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 26(3): 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfmm-12-2020-0275 .

Msallati, A. 2021. Investigating the nexus between the types of advertising messages and customer engagement: Do customer involvement and generations matter? Journal of Innovations in Digital Marketing 2(1): 1–13.

Naeem, M., and W. Ozuem. 2021. (2021) Understanding the social consumer fashion brand engagement journey: Insights about reputed fashion brands. Journal Brand Managment 28: 510–525. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00239-5 .

Oh, C., Y. Roumani, J.K. Nwankpa, and H.-F. Hu. 2017. Beyond likes and tweets: Consumer engagement behavior and movie box office in social media. Information & Management 54(1): 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.03.004 .

Omar, B., and W. Dequan. 2020. Watch, share or create: The influence of personality traits and user motivation on TikTok mobile video usage. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (IJIM) 14(04): 121–137. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i04.12429 .

Pagani, M., and A. Mirabello. 2011. The influence of personal and social-interactive engagement in social TV Web sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 16(2): 41–68. https://doi.org/10.2753/jec1086-4415160203 .

Paine, K. 2011. Measure what matters: Online tools for understanding customers, social media, engagement, and key relationships . Wiley.

Palmatier, R.W., R.P. Dant, D. Grewal, and K.R. Evans. 2006. “Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing 70(4): 136–153.

Prahalad, C. K., & V. Ramaswamy. 2004. The future of competition: co-creating unique value with customers. In Choice Reviews Online (Vol. 41, Issue 11). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.41-6635

Qiyang, Z., & Jung. 2019. Learning and Sharing Creative Skills with Short Videos: A Case Study of User Behavior in TikTok and Bilibili. International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference 2019 , 2–9. https://iasdr2019.org/uploads/files/Proceedings/le-f-1209-Zho-Q.pdf . https://iasdr2019.org/uploads/files/Proceedings/le-f-1209-Zho-Q.pdf .

Rangaswamy, A., N. Moch, C. Felten, G. van Bruggen, J.E. Wieringa, and J. Wirtz. 2020. The role of marketing in digital business platforms. Journal of Interactive Marketing 51: 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.04.006 .

Razmus, W., M. Jaroszyńska, and M. Palęga. 2017. Personal aspirations and brand engagement in self-concept. Personality and Individual Differences 105: 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.018 .

Ringle, Sarstedt, and Straub,. 2012. Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly.” MIS Quarterly 36(1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410402 .

Ruano, L.E., and J.A. Maca. 2017. Motivation in the use of virtual social networks. CIAIQ 3: 1982–1991.

Ruiz, J. 2021. Frequency of Engagement Rate per minute. In Tik Tok for Business (p. 1). Head of Marketing Science, TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/business/library/TikTokDrivesGreaterAudienceEngagement.pdf

Schivinski, B., G. Christodoulides, and D. Dabrowski. 2016. Measuring consumers’ engagement with brand-related social-media content. Journal of Advertising Research 56(1): 64–80. https://doi.org/10.2501/jar-2016-004 .

Sepp, M., V. Liljander, and J. Gummerus. 2011. Private bloggers’ motivations to produce content-a gratifications theory perspective. Journal of Marketing Management 27(13–14): 1479–1503. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2011.624532 .

Shane-Simpson, C., A. Manago, N. Gaggi, and K. Gillespie-Lynch. 2018. Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital. Computers in Human Behavior 86: 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.041 .

Shao, G. 2009. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Research 19(1): 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240910927795 .

Singh, A.P., and J. Dangmei. 2016. Understanding the generation Z: The future workforce. South-Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 3(3): 1–5.

Song, S., and M. Yoo. 2016. The role of social media during the pre-purchasing stage. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 7(1): 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhtt-11-2014-0067 .

Southgate, D. 2017. The emergence of Generation Z and its impact in advertising: Long-term implications for media planning and creative development. JOurnal of Advertising Research 57(2): 227–235.

Statista 2021. Topic: TikTok marketing . Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/8309/tiktok-marketing/#dossierKeyfigures .

Sundar, S.S. 2000. Multimedia effects on processing and perception of online news: A study of picture, audio, and video downloads. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77(3): 480–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700302 .

Sundar, S.S., and A.M. Limperos. 2013. Uses and grats 2.0: New gratifications for new media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 57(4): 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827 .

Tang, D. 2019. The New Situation of Marketing in the Self-Media Era-Taking Tik Tok as an Example. 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences , 1557–1560. https://doi.org/10.25236/iwass.2019.281 .

Tik Tok for Business 2021. TikTok For Business: marketing on TikTok . Www.tiktok.com. https://www.tiktok.com/business/es .

Tik Tok for Business 2022. Supercharge your TikTok strategy with an Always Engaged approach . TikTok for Business. https://www.tiktok.com/business/es/blog/supercharge-your-tiktok-strategy-with-an-always-engaged-approach .

Toni, M., & G. Mattia. 1043. Tik Tok hashtag challenge: a new digital strategy for Consumer Brand Engagement (CBE). Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy , 2–9. http://proceedings.emac-online.org/pdfs/R2021-104352.pdf . http://proceedings.emac-online.org/pdfs/R2021-104352.pdf .

Turner, A. 2015. Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest. The Journal of Individual Psychology 71(2): 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2015.0021 .

Unnava, V., and A. Aravindakshan. 2021. How does consumer engagement evolve when brands post across multiple social media? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 49(5): 864–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00785-z .

van Doorn, J., K.N. Lemon, V. Mittal, S. Nass, D. Pick, P. Pirner, and P.C. Verhoef. 2010. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research 13(3): 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599 .

Verduyn, P., N. Gugushvili, and E. Kross. 2021. Do social networking sites influence well-being? The extended active-passive model. Current Directions in Psychological Science 31(1): 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211053637 .

Verduyn, P., N. Gugushvili, K. Massar, K. Täht, and E. Kross. 2020. Social comparison on social networking sites. Current Opinion in Psychology 36: 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002 .

Verduyn, P., O. Ybarra, M. Résibois, J. Jonides, and E. Kross. 2017. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review 11(1): 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033 .

Vivek, S.D., S.E. Beatty, V. Dalela, and R.M. Morgan. 2014. A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 22(4): 401–420. https://doi.org/10.2753/mtp1069-6679220404 .

Voorveld, H.A.M., G. van Noort, D.G. Muntinga, and F. Bronner. 2018. Engagement with social media and social media advertising: The differentiating role of platform type. Journal of Advertising 47(1): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754 .

Wang, Y.-H., T.-J. Gu, and S.-Y. Wang. 2019. Causes and characteristics of short video platform internet community taking the TikTok short video application as an example. IEEE Xplore . https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCE-TW46550.2019.8992021 .

Whiting, A., and D. Williams. 2013. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 16(4): 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/qmr-06-2013-0041 .

Willis, M. 2007. An emotionally intelligent user interface: modelling emotion for user engagement. In Proceedings of the 19th Australasian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction: Entertaining User Interfaces (pp. 187–190).

Xiao, Y., L., Wang, & P., Wang. 2019. Research on the influence of content features of short video marketing on consumer purchase intentions. Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology and Social Science (MMETSS 2019) , 351 , 415–422. https://doi.org/10.2991/mmetss-19.2019.82 .

Xu, L., X. Yan, and Z. Zhang. 2019. Research on the causes of the “Tik Tok” app becoming popular and the existing problems. Journal of Advanced Management Science 7(2): 59–63.

Yang, H.C., and Y. Wang. 2015. Social sharing of online videos: Examining american consumers’ video sharing attitudes, intent, and behavior. Psychology & Marketing 32(9): 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20826 .

Yang, S., Y. Zhao, and Ma, and Y. 2019. Analysis of the reasons and development of short video application-taking Tik Tok as an example. Webofproceedings 5: 340–343.

Yue, Z., R. Zhang, and J. Xiao. 2021. Passive social media use and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social comparison and emotion regulation. Computers in Human Behavior 127: 107050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107050 .

Zuo, H., and T. Wang. 2019. Analysis of Tik Tok user behavior from the perspective of popular culture. Frontiers in Art Research 1(3): 1–5.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Business, Tourism and Entrepreneurship, Universidad Ana G. Mendez-Gurabo Campus, PO Box 3030, Gurabo, PR, 00778-3030, USA

Jose A. Flecha Ortiz, Evelyn Lopez, Virgin Dones & Vivian Feliberty Lugo

San Juan, Puerto Rico

María De Los M. Santos Corrada

School Graduate in Bussiness Administration, Universidad de Puerto Rico-Recinto de Rio Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jose A. Flecha Ortiz .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author confirms that all authors have participated in (a) conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of the data; (b) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (c) approval of the final version. This manuscript has not been submitted to, nor is under review at, another journal or other publishing venue. The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Human and/or animals participants

The authors declare that this research study complies with the standards of ethics in human subject’s research. And the conduct of the study was approved by the IRB committee under the Universidad Ana G. Mendez with approved protocol number 1414048–1.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ortiz, J.A.F., De Los M. Santos Corrada, M., Lopez, E. et al. Don't make ads, make TikTok’s: media and brand engagement through Gen Z's use of TikTok and its significance in purchase intent. J Brand Manag 30 , 535–549 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-023-00330-z

Download citation

Revised : 20 March 2023

Accepted : 27 April 2023

Published : 18 May 2023

Issue Date : November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-023-00330-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Consumer engagement

- Media engagement

- Brand engagement

- Purchase intention

- Passive usage

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology , 2020, 2(11); doi: 10.25236/FSST.2020.021113 .

Advertisement on Tik Tok as a Pioneer in New Advertising Era: Exploring Its Persuasive Elements in the Development of Positive Attitudes in Consumers

Corporate and Organizational Communication, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Ave, Boston, U.S.

*Correspondence Email: [email protected]

- Full-Text HTML

- Full-Text XML

- Full-Text Epub

- Download PDF

- Download: 978

Tik Tok is the most prosperous short video platform with a great power of advertising in China. This study aims to develop provide insight into the scale items of consumers’ attitudes toward the advertisements on Tik Tok and to theorize the consumers’ attitudinal behavior. To undertake this study, the researcher interviewed 900 people about their preference to platforms’ advertisements and summarize the reasons that they embrace the ads on Tik Tok. Then the researcher conducted an empirical study among the members identified in the quantitative study that holds positive attitudes towards ads on Tik Tok. A total of 396 questionnaires were distributed to them and 339 valid responses were collected. By validating the scale items and their underlying constructs, it could be concluded that the positive attitudes in consumers are persuaded by entertainment motivation (EM), User-Friendly (UF), Customer-Build (CB), Reliability and Authenticity (RA), and User Interaction (UI).

Advertisement, Tik tok, Consumer attitude, Behavioral attitude, Persuasive

Cite This Paper

Yu Han. Advertisement on Tik Tok as a Pioneer in New Advertising Era: Exploring Its Persuasive Elements in the Development of Positive Attitudes in Consumers. The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology (2020) Vol. 2 Issue 11: 81-92. https://doi.org/10.25236/FSST.2020.021113.

[1] Ahmad, I (2019). Global Ad Blocking Behavior 2019 [Infographic]. Retrieved from https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/global-ad-blocking-behavior-2019-infographic/551716/

[2] Gorman, L., & McLean, D (2009). Media and society into the 21st century: a historical introduction. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

[3] Greenwald, A. G (1968). Cognitive Learning, Cognitive Response to Persuasion, and Attitude Change. Psychological Foundations of Attitudes, pp.147-170.

[4] Nicosia, F. M (1966). Consumer decision processes: marketing and advertising implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

[5] Lee, J., Ham, C.-D., Kim, M (2013). Why People Pass Along Online Video Advertising: From the Perspectives of the Interpersonal Communication Motives Scale and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Journal of Interactive Advertising, vol.13, no.1, pp.1-13.

[6] Rubin, R. B., Perse, E. M., Barbato, C. A (1988). Conceptualization and Measurement of Interpersonal Communication Motives. Human Communication Research, vol.14, no.4, pp.602-628.

[7] Fishbein, M., Middlestadt, S. E. (1987). Using the theory of reasoned action to develop educational interventions: applications to illicit drug use. Health Education Research, vol.2, no.4, pp.361-371.

[8] Mir, I. A (2017). Impact of Entertainment Motivational Drivers on User Acceptance of Online Social Network Banner Advertising: A Gratification Perspective. Zagreb International Review of Economics and Business, vol.20, no.1, pp.19-47.

[9] Stein, M. K (2013). Implementing standards-based mathematics instruction: a casebook for professional development. New York: Teachers College Press.

[10] Bang, H., Wojdynski, B. W (2016). Tracking users visual attention and responses to personalized advertising based on task cognitive demand. Computers in Human Behavior, no.55, pp.867-876.

[11] Homer, P. M (1990). The Mediating Role of Attitude toward the Ad: Some Additional Evidence. Journal of Marketing Research, vol.27, no.1, pp.78-79.

[12] Huang, C.-Y., Chou, C.-J., Lin, P.-C (2010). Involvement theory in constructing bloggers intention to purchase travel products. Tourism Management, vol.31, no.4, pp.513-526.

[13] Shareef, M. A., Mukerji, B., Alryalat, M. A. A., et al (2018). Advertisements on Facebook: Identifying the persuasive elements in the development of positive attitudes in consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, no.43, pp.258-268.

[14] Cronbach, L. J (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, vol.16, no.3, pp. 297-334.

[15] Kaiser, H. F., Rice, J (1974). Little jiffy, mark IV. Educational and psychological measurement, vol.34, no.1, pp.111-117.

[16] Kaiser, H. F (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, vol.39, no.1, pp.31-36.

[17] Churchill, G. A (1978). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Madison: Graduate School of Business, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

[18] Segars, A. H., Grover, V (1993). Re-Examining Perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. MIS Quarterly, vol.17, no.4, pp.517-518.

[19] Chau, P. Y (1997). Reexamining a Model for Evaluating Information Center Success Using a Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Decision Sciences, vol.28, no.2, pp.309-334.

[20] Kline, R. B (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

[21] Trochim, W. M. K. (n.d.). Construct Validity. Retrieved from https://socialresearchmethods.net/kb/construct-validity/

[22] Jackson, D. N (1968). Multimethod factor analysis in the evaluation of convergent and discriminant validity. London, Ont.: Dept. of Psychology, University of Western Ontario.

[23] Fornell, C., Larcker, D. F (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, vol.18, no.1, pp.39-40.

[24] Espinoza, M. M (1999). Assessing the cross‐cultural applicability of a service quality measure A comparative study between Quebec and Peru. International Journal of Service Industry Management, vol.10, no.5, pp.449-468.

[25] Larose, R., Eastin, M. S (2004). A Social Cognitive Theory of Internet Uses and Gratifications: Toward a New Model of Media Attendance. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol.48, no.3, pp.358-377.

- Do Not Sell My Personal Info

- ⋅

Research Reveals TikTok’s Impact On Consumers’ Purchase Journeys

Whether you want to build brand awareness, generate qualified leads, boost traffic, or improve conversions, TikTok can help. Here's why.

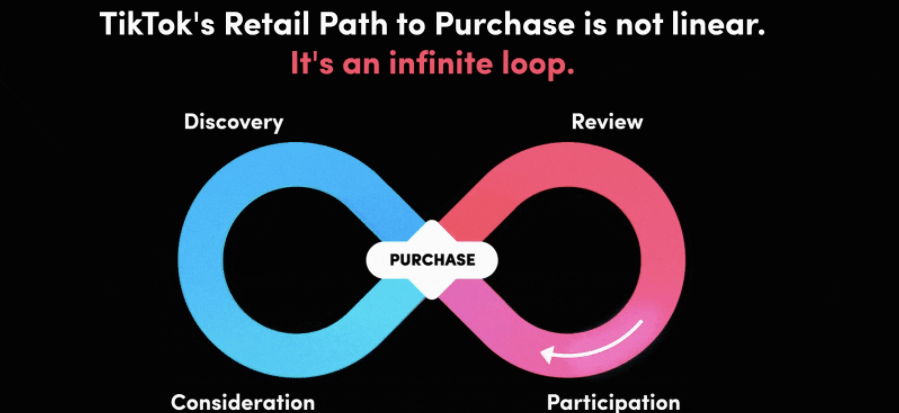

TikTok has shared the second installment of its Path-to-Purchase Report, a study that shows TikTok’s impact on consumers’ purchase journeys – from discovery to consideration to post-purchase evangelism.

The latest research gives brands several interesting insights into how they can harness the platform not only to drive culturally relevant conversations but also to supercharge their sales.

In addition, the report demonstrates how TikTok’s platform and community can drive impact beyond spur-of-the-moment impulse buys.

Consumers tend to share joyful content about big-ticket purchase items such as vacations and new cars, which in turn drives action among other consumers who are eager to participate in the conversation both on and off the platform.

Key highlights of the latest research include reveal that TikTok has a powerful and positive impact throughout the purchase journey. TikTok turns out to be a word-of-mouth marketplace that’s driven by post-purchase actions as users turn to brands, creators, and trending topics to discover new products.

- 50% of users report that they are more likely to feel joyful, excited, or happy about the products they’ve purchased.

- 58% of TikTok users discover new brands and products on the platform.

- 44% discovered something they immediately went out to buy.

- Discovery happens on TikTok 1.1x more than on other platforms.

It’s also worth noting that what happens on TikTok doesn’t stay on TikTok.

TikTok users are 56% more likely to research new brands or products on the platform than on other platforms, even for bigger-ticket purchases like automotive and travel.

However, these TikTok-inclusive journeys also see:

- 65% of users conducting more online research.

- 57% of users seeking more details on where to buy products.

- 54% of users also conducting in-person research.

TikTok’s unique discovery patterns and strong engagement behavior in the research process also mean that satisfied customers amplify brands and products post-purchase, as evidenced by the following:

- 58% of TikTok users convinced another person to use a product

- 49% of TikTok users recommend products to those who are shopping for them.

- 47% of TikTok users convince others to buy products that they saw on the platform,

Matt Southern, Search Engine Journal’s Senior News Writer, covered the first part of TikTok’s global research study back in February in an article entitled, “ TikTok a Key Part of Consumers’ Path to Purchase .”

That research found that the path to purchase on TikTok looked more like an “infinite loop” than the traditional path to purchase.

And in an article that I wrote in December 2020, “ The Future of SEO Lies in the “Messy Middle” of the Purchase Journey ,” research by Google’s consumer insights team in the UK also found that consumers loop between exploring and evaluating the options available to them until they are ready to purchase.

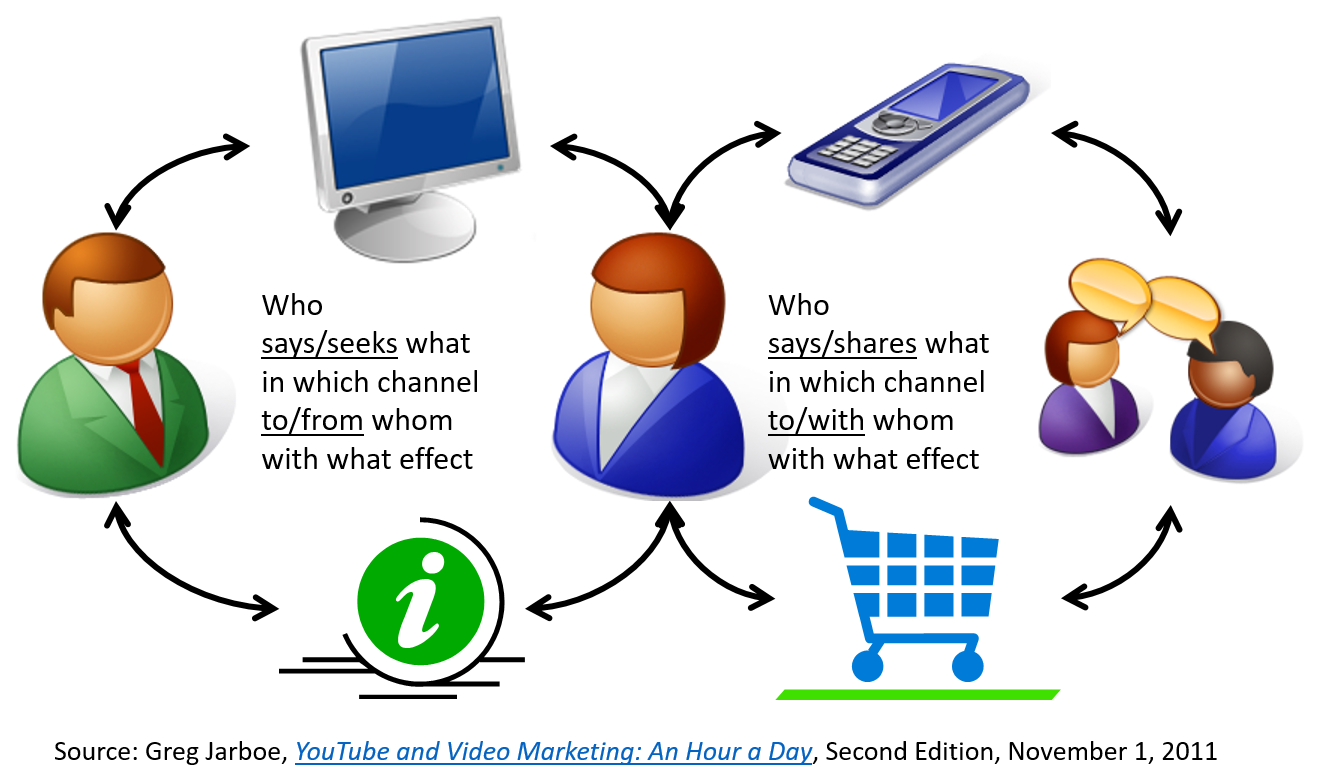

I outlined a similar looping process for discovering new videos and sharing compelling content in my book, YouTube and Video Marketing , which was published back in November 2011.

And I’d been inspired to create this model of video search and sharing by reading about research that was conducted before I was born.

In 1948, Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet published The People’s Choice , a study of the 1940 U.S. Presidential election.

They found a two-step flow of communication. The first step, from media sources to opinion leaders, was a transfer of information, but the second step, from opinion leaders to their followers, also involved interpersonal influence.

More than a decade ago, I used the two-step flow model to explain how YouTube worked.

Harnessing this insight enabled creators and marketers to leverage YouTube’s unique power as the world’s largest video search engine as well as the world’s largest video sharing site.

So, TikTok’s latest research is supported by a series of similar findings over 80 years.

That means that whether you want to build brand awareness, generate qualified leads, boost traffic, or improve conversions, social video works much more like word-of-mouth marketing and a lot less like mass media marketing.

And recognizing this is the key to creating digital marketing strategies that can harness TikTok’s impact on consumers’ purchase journeys – from discovery to consideration to post-purchase evangelism.

Featured Image: Luiza Kamalova/Shutterstock

Greg Jarboe is president of SEO-PR, which he co-founded with Jamie O’Donnell in 2003. Their digital marketing agency has won ...

Subscribe To Our Newsletter.

Conquer your day with daily search marketing news.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 09 May 2024

US TikTok ban: how the looming restriction is affecting scientists on the app

- Ariana Remmel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Neuroscientist Michael Rhodes (from left), the organic chemist known as Chem Thug and neuroscientist Morgan Johnston all use the social-media app TikTok to communicate science. Credits L-R: Michael Rhodes/rhodeslovesneuroscience/TikTok; Chem Thug; AskANeuroscientist/TikTok

US President Joe Biden signed legislation last month that could trigger a nationwide ban of the popular social-media app TikTok within a year. Researchers who use the app to communicate science to curious followers, study social trends and earn money to support themselves are dismayed and frustrated.

Creating YouTube and TikTok videos is improving my lab leadership

TikTok is owned by ByteDance, a firm based in Beijing, China — which, amid growing US–China tensions, has raised national-security concerns among US officials, related to the Chinese government’s access to user data. On 7 May, TikTok filed a lawsuit calling the legislation, which gives ByteDance nine months to a year to find a US-based buyer for the app, an “extraordinary intrusion on free speech rights”. If the ban goes into effect, users in the United States will no longer be able to add the app to their devices or install updated versions.

Morgan Johnston, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at San Antonio, worries that young people who use TikTok will lose an outlet to learn about science and find community. Sixty-three per cent of US teenagers aged 13 to 17 and 33% of US adults use the app, according to several surveys conducted last year by the Pew Research Center in Washington DC and market-research firm Ipsos in New York City. Although dance routines and pop-culture discussions are often trending on the app, many people use it to learn about science, says Johnston, who runs the account @askaneuroscientist . She posts videos about her research on the impact of stress on learning and answers questions from her 37,600 followers. “I love the interaction part of it,” she says.

Nature spoke to five scientists and communicators in the United States about what they will do if the ban goes into effect. Most of them acknowledge the data-security concerns, but say that the legislation would cut off a thriving platform for science education and outreach, especially among young people who are seeking information from trusted sources.

“We need stricter laws on what data can be collected and sold, but this legislation doesn’t do that,” says Johnston, who uses her channel to talk about her mental-health journey as she navigates graduate school as a first-generation PhD student from a rural area. “My following is young adults who are in the process of making their career decisions — and they’re really curious.”

Engaged audiences

The seismic growth of the app during lockdowns initiated because of the COVID-19 pandemic helped to make TikTok a “massive platform for outreach”, says Jamie Zaccaria, a media and outreach specialist at the Ocean Exploration Trust, a research-focused non-profit organization in New London, Connecticut. In 2022, the trust launched its TikTok account, @nautiluslive , which streams footage of deep-sea expeditions narrated in real time by excited researchers discovering striking marine creatures. The account has more than half a million followers, and some ask for educational resources or advice on how to pursue a career in ocean science.

Researchers with the Ocean Exploration Trust marvel at a mysterious deep-sea jellyfish in this video (shown here on YouTube, but also available on TikTok).

The Ocean Exploration Trust declined to comment on the legislation, but it has several successful social-media accounts, including on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram, to which it could shift its focus if the ban goes into effect.

Some content creators with smaller online followings might not have that option. Michael Rhodes, a neuroscientist at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, started posting on his TikTok account, @rhodeslovesneuroscience , in 2020 to boost morale among undergraduate students in his classes. With their help and with help from researchers in his lab, Rhodes posts educational videos about anatomy, physiology and pharmacology, including dance routines that demonstrate the actions performed by specific muscle groups and skits that explain how drugs work. “I’ve become a better professor because it makes me take a step back and look at information differently,” he says.

Rhodes says that most of his roughly 189,000 followers are students or early-career health-care professionals. But with all his academic responsibilities, he isn’t sure that he will be able to pivot to a new platform if TikTok disappears in the United States. “If a third of the country is using TikTok, that should tell you something about its popularity,” he adds.

Secret sauce

One thing that makes TikTok different from other social-networking apps is how its algorithm curates content from across the platform — not just the accounts a user follows — to appeal to the specific interests of each user, says Matt Motta, a health-communications researcher at Boston University’s School of Public Health. “That becomes a way for scientists to have their messages transmitted to audiences that may not self-select into them,” he says.

TikTok’s critics say that this proprietary algorithm imbues the app with addictive properties that can drive the spread of misinformation and contribute to the US mental-health crisis. But, recognizing its reach, Motta and his colleagues are studying how TikTok could be harnessed for good by training mental-health content creators on the app to disseminate evidence-based information among their followers 1 .

“It’s important to remember that some scientists are working with TikTok to study social phenomena. And if TikTok were to go away, our ability to do that would be significantly hindered,” Motta says. At the same time, Motta and others acknowledge concerns about data security related to the use of social-media apps such as TikTok.

The TikTok creator and organic chemist known as Chem Thug explains why batteries bounce when they run out of juice (shown here on YouTube, also available on TikTok).

Digital privacy is part of the reason that the organic-chemistry PhD student behind the viral @chem.thug TikTok account does not share his real identity or the university that he attends. His conversational explainer videos put scientific concepts in a real-world context for more than 284,300 followers on TikTok and around 10,000 on YouTube. For example, in one of his popular clips about household chemicals, Chem Thug explains why zinc-based batteries become “bouncy” as they lose charge. “I think everybody’s life is enriched by a better, deeper understanding of chemistry,” he says. Like Johnston, Chem Thug has monetized his account as a supplemental line of income to support himself during graduate school.

Chem Thug is cautious about putting his personal information on the Internet, but says that he doesn’t “see Bytedance as being any more nefarious than any other large corporation with interest in making as much money as possible”.

Few sources who spoke to Nature anticipate that a ban will go into effect on the proposed timeline, especially considering that the lawsuit filed by TikTok will undoubtedly tie up the legislation in courts. But the spectre of the ban is sparking serious conversations among TikTok scientists, especially those who sought refuge on the app after billionaire Elon Musk bought the social-media platform Twitter (now X) and made many unpopular changes . “Where are we going to recreate this community?” Johnston asks. “There’s not really a consensus.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01388-8

Motta, M. et al. Sci. Rep. 14 , 5864 (2024).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Scientific community

- Communication

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Dozens of Brazilian universities hit by strikes over academic wages

News 08 MAY 24

‘Shrugging off failure is hard’: the $400-million grant setback that shaped the Smithsonian lead scientist’s career

Career Q&A 15 APR 24

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

Tweeting your research paper boosts engagement but not citations

News 27 MAR 24

Judge dismisses superconductivity physicist’s lawsuit against university

News 25 APR 24

European ruling linking climate change to human rights could be a game changer — here’s how

World View 23 APR 24

Do climate lawsuits lead to action? Researchers assess their impact

News Explainer 16 APR 24

Southeast University Future Technology Institute Recruitment Notice

Professor openings in mechanical engineering, control science and engineering, and integrating emerging interdisciplinary majors

Nanjing, Jiangsu (CN)

Southeast University

Staff Scientist

A Staff Scientist position is available in the laboratory of Drs. Elliot and Glassberg to study translational aspects of lung injury, repair and fibro

Maywood, Illinois

Loyola University Chicago - Department of Medicine

W3-Professorship (with tenure) in Inorganic Chemistry

The Institute of Inorganic Chemistry in the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences at the University of Bonn invites applications for a W3-Pro...

53113, Zentrum (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Principal Investigator Positions at the Chinese Institutes for Medical Research, Beijing

Studies of mechanisms of human diseases, drug discovery, biomedical engineering, public health and relevant interdisciplinary fields.

Beijing, China

The Chinese Institutes for Medical Research (CIMR), Beijing

Research Associate - Neural Development Disorders

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

Read TikTok’s legal challenge

- Share full article

A PDF version of this document with embedded text is available at the link below:

Download the original document (pdf)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 1 of 70 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT TIKTOK INC., and BYTEDANCE LTD., V. ) Petitioners, No. 24-1113 MERRICK B. GARLAND, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States, (Page 1 of Total) Respondent. PETITION FOR REVIEW OF CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE PROTECTING AMERICANS FROM FOREIGN ADVERSARY CONTROLLED APPLICATIONS ACT

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 2 of 70 2. That law 1. Congress has taken the unprecedented step of expressly singling out and banning TikTok: a vibrant online forum for protected speech and expression used by 170 million Americans to create, share, and view videos over the Internet. For the first time in history, Congress has enacted a law that subjects a single, named speech platform to a permanent, nationwide ban, and bars every American from participating in a unique online community with more than 1 billion people worldwide. the Protecting Americans From Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (the "Act") is unconstitutional. Banning Tik Tok is so obviously unconstitutional, in fact, that even the Act's sponsors recognized that reality, and therefore have tried mightily to depict the law not as a ban at all, but merely a regulation of TikTok's ownership. According to its sponsors, the Act responds to TikTok's ultimate ownership by ByteDance Ltd., a company with Chinese subsidiaries whose employees support various Byte Dance businesses, including TikTok. They claim that the Act is not a ban because it offers Byte Dance a choice: divest TikTok's U.S. business or be shut down.1 ― - 1 References to "TikTok Inc." are to the specific U.S. corporate entity that is a Petitioner in this lawsuit and publishes the TikTok platform in the 1 (Page 2 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 3 of 70 3. But in reality, there is no choice. The "qualified divestiture" demanded by the Act to allow TikTok to continue operating in the United States is simply not possible: not commercially, not technologically, not legally. And certainly not on the 270-day timeline required by the Act. Petitioners have repeatedly explained this to the U.S. government, and sponsors of the Act were aware that divestment is not possible. There is no question: the Act will force a shutdown of TikTok by January 19, 2025, silencing the 170 million Americans who use the platform to communicate in ways that cannot be replicated elsewhere. 4. Of course, even if a "qualified divestiture" were feasible, the Act would still be an extraordinary and unconstitutional assertion of power. If upheld, it would allow the government to decide that a company may no longer own and publish the innovative and unique speech United States. References to "TikTok" are to the online platform, which includes both the Tik Tok mobile application and web browser experience. References to “ByteDance Ltd." are to the specific Cayman Islands- incorporated holding company that is identified in the Act and is a Petitioner in this lawsuit. References to "ByteDance" are to the ByteDance group, inclusive of ByteDance Ltd. and relevant operating subsidiaries. TikTok Inc. and ByteDance. Ltd. are together referred to as "Petitioners." (Page 3 of Total) 21

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 4 of 70 platform it created. If Congress can do this, it can circumvent the First. Amendment by invoking national security and ordering the publisher of any individual newspaper or website to sell to avoid being shut down. And for Tik Tok, any such divestiture would disconnect Americans from the rest of the global community on a platform devoted to shared content an outcome fundamentally at odds with the Constitution's commitment to both free speech and individual liberty. 5. There are good reasons why Congress has never before enacted a law like this. Consistent with the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of expression, the United States has long championed a free and open Internet - and the Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that speech "conveyed over the Internet” fully qualifies for “the First Amendment's protections." 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, 600 U.S. 570, 587 (2023). And consistent with the fundamental principles of fairness and equal treatment rooted in the Bill of Attainder Clause and the Fifth Amendment, Congress has never before crafted a two-tiered speech regime with one set of rules for one named platform, and another set of rules for everyone else. (Page 4 of Total) 3

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 5 of 70 6. In dramatic contrast with past enactments that sought to regulate constitutionally protected activity, Congress enacted these extreme measures without a single legislative finding. The Act does not articulate any threat posed by Tik Tok nor explain why TikTok should be excluded from evaluation under the standards Congress concurrently imposed on every other platform. Even the statements by individual Members of Congress and a congressional committee report merely indicate concern about the hypothetical possibility that TikTok could be misused in the future, without citing specific evidence - even though the platform has operated prominently in the United States since it was first launched in 2017. Those speculative concerns fall far short of what is required when First Amendment rights are at stake. 7. Nor is there any indication that Congress considered any number of less restrictive alternatives, such as those that Petitioners developed with the Executive Branch after government agencies began evaluating the security of U.S. user data and the risk of foreign government influence over the platform's content as far back as 2019. While such concerns were never substantiated, Petitioners nevertheless (Page 5 of Total) 4

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 6 of 70 worked with the government for four years on a voluntary basis to develop a framework to address the government's concerns. 8. As part of this engagement, Petitioners have voluntarily invested more than $2 billion to build a system of technological and governance protections sometimes referred to as "Project Texas" - to help safeguard U.S. user data and the integrity of the U.S. TikTok platform against foreign government influence. Petitioners have also made extraordinary, additional commitments in a 90-page draft National Security Agreement developed through negotiations with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States ("CFIUS”), including agreeing to a “shut-down option” that would give the government the authority to suspend TikTok in the United States if Petitioners violate certain obligations under the agreement. 9. Congress tossed this tailored agreement aside, in favor of the politically expedient and punitive approach of targeting for disfavor one publisher and speaker (TikTok Inc.), one speech forum (TikTok), and that forum's ultimate owner (ByteDance Ltd.). Through the Act's two-tiered. structure, Congress consciously eschewed responsible industry-wide. regulation and betrayed its punitive and discriminatory purpose. 5 (Page 6 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 7 of 70 Congress provided every other company however serious a threat to - national security it might pose - paths to avoiding a ban, excluding only Tik Tok Inc. and ByteDance Ltd. Indeed, for any other company's application to be banned, Congress mandated notice and a "public report" describing "the specific national security" concern, accompanied by supporting classified evidence. For Petitioners only, however, there is no statement of reasons and no supporting evidence, with any discussion of the justifications for a ban occurring only behind closed doors. 10. Congress must abide by the dictates of the Constitution even when it claims to be protecting against national security risks: “against [those] dangers ... as against others, the principle of the right to free speech is always the same." Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 628 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting). Congress failed to do so here, and the Act should be enjoined. 11. Jurisdictional Statement Pursuant to Sections 3(a) and 3(b) of the Act, H.R. 815, div. H, 118th Cong., Pub. L. No. 118-50 (April 24, 2024), this Court has original (Page 7 of Total) 6

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 8 of 70 and exclusive jurisdiction over this challenge to the constitutionality of the Act. 2 A. 12. Background and Nature of Proceedings TikTok Is a Speech Platform Used by 170 Million Americans. Tik Tok is an online video entertainment platform designed to provide a creative and entertaining forum for users to express themselves and make connections with others over the Internet. More than 170 million Americans use TikTok every month, to learn about and share information on a range of topics from entertainment, to religion, to - politics. Content creators use the TikTok platform to express their opinions, discuss their political views, support their preferred political candidates, and speak out on today's many pressing issues, all to a global audience of more than 1 billion users. Many creators also use the 2 A copy of the Act is attached to this Petition as Exhibit A. Because this Petition does not involve a challenge to any agency action, it is not governed by Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 15(a). Petitioners intend to file a separate motion regarding the procedures governing this original proceeding. Petitioners summarize the pertinent facts and claims below to facilitate this Court's review consistent with the practice of a case-initiating pleading in a court of original jurisdiction, but reserve their rights to present additional facts and arguments in due course. 7 (Page 8 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 9 of 70 platform to post product reviews, business reviews, and travel information and reviews. 13. In the United States, the TikTok platform is provided by Tik Tok Inc., a California-incorporated company that has its principal place of business in Culver City, California and offices in New York, San Jose, Chicago, and Miami, among other locations. TikTok Inc. has thousands of employees in the United States. Like many platforms owned by companies that operate globally, the global TikTok platform is supported not only by those employees, but also by employees of other ByteDance subsidiaries around the globe, including in Singapore, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Germany, South Africa, Australia, and China. Many of the global TikTok platform's functions are spread across different corporate entities and countries, and the global TikTok business is led by a leadership team based in Singapore and the United States. Like other U.S. companies, TikTok Inc. is governed by U.S. law. 14. Tik Tok Inc.'s ultimate parent company is ByteDance Ltd., a Cayman Islands-incorporated equity holding company. Byte Dance was founded in 2012 by Chinese entrepreneurs. Over time, the company sought funding to fuel growth, as is common in the technology sector, 8 (Page 9 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 10 of 70 which resulted in the issuance of additional equity and the dilution of existing shares. Today, approximately 58 percent of ByteDance Ltd. is owned by global institutional investors (such as BlackRock, General Atlantic, and Susquehanna International Group), 21 percent is owned by the company's founder (a Chinese national who lives in Singapore), and 21 percent is owned by employees including approximately 7,000 Americans. 15. ByteDance launched TikTok in May 2017 in over 150 countries, including the United States.³ Since its launch, TikTok has become one of the world's most popular applications, with over 1 billion users worldwide. As of January 2024, more than 170 million Americans use TikTok on a monthly basis. 16. Users primarily view content on TikTok through its "For You" page, which presents a collection of videos curated by TikTok's proprietary recommendation engine. The recommendation engine customizes each user's content feed based on how the user interacts with 3 Tik Tok was later relaunched in August 2018 following a transaction involving the company Musical.ly. See generally Petition for Review, Tik Tok Inc. v. CFIUS, No. 20-1444 (D.C. Cir. Nov. 10, 2020). 9 (Page 10 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 11 of 70 the content that the user watches. TikTok's popularity is based in large part on the effectiveness of the recommendation engine. The source code for TikTok's recommendation engine was originally developed by ByteDance engineers based in China, and the engine is customized for operations in TikTok's various global markets, including in the United States. TikTok is not offered in mainland China. 17. Aside from TikTok, ByteDance has developed and operates more than a dozen other online platforms and software applications for use in U.S. and international markets, including for content-sharing, video and music editing, e-commerce, gaming, and enterprise productivity. B. 18. The Government Previously Made Unlawful Attempts to Ban TikTok. Petitioners' efforts to address the U.S. government's asserted concerns regarding the TikTok platform date back to 2019. At that time, Petitioners began engaging with CFIUS, which had initiated a review of ByteDance Ltd.'s 2017 acquisition of Musical.ly, another Internet-based video-sharing platform. (Page 11 of Total) 10

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 12 of 70 19. Petitioners were in the early stages of engaging with CFIUS on a voluntary basis to address the government's concerns, when on August 6, 2020, President Trump abruptly issued an executive order purporting to ban TikTok under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA”), 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701-08. See 85 Fed. Reg. 48,637 (the "Ban Order"). Two separate district courts preliminarily enjoined the Ban Order, concluding (among other things) that it exceeded the President's IEEPA authority. TikTok Inc. v. Trump, 490 F. Supp. 3d 73, 83 (D.D.C. 2020); TikTok Inc. v. Trump, 507 F. Supp. 3d 92, 112 (D.D.C. 2020); Marland v. Trump, 498 F. Supp. 3d 624, 641 (E.D. Pa. 2020). 20. Specifically, as these courts correctly recognized, the President's IEEPA authority "to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat" to the nation “does not include the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly ... [any] personal communication” or the importation or exportation “of any information or informational materials.” 50 U.S.C. § 1702(b)(1), (3). These restrictions on the President's IEEPA authority-which Congress expanded through multiple amendments to the statute were designed “to prevent the statute from running afoul of the First Amendment.” United States v. 11 (Page 12 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 13 of 70 Amirnazmi, 645 F.3d 564, 585 (3d Cir. 2011) (quotation marks omitted); see also Kalantari v. NITV, Inc., 352 F.3d 1202, 1205 (9th Cir. 2003) (IEEPA's limitations necessary “to prevent the executive branch from restricting the international flow of materials protected by the First. Amendment"); Marland, 498 F. Supp. 3d at 629 (same). 21. Looking to the foundational First Amendment principles codified in IEEPA's text and legislative history, these courts concluded that President Trump's efforts to ban TikTok violated the statute and raised "serious" constitutional questions (which were unnecessary to decide under the doctrine of constitutional avoidance). Tik Tok Inc., 507 F. Supp. 3d at 112 n.6; TikTok Inc., 490 F. Supp. 3d at 83 n.3. The courts granted the government's motions to voluntarily dismiss its appeals after President Biden withdrew the Ban Order. See Tik Tok Inc. v. Biden, No. 20-5302, 2021 WL 3713550 (D.C. Cir. July 20, 2021); Tik Tok Inc. v. Biden, No. 20-5381, 2021 WL 3082803 (D.C. Cir. July 14, 2021); Marland v. Trump, No. 20-3322, 2021 WL 5346749 (3d Cir. July 14, 2021). 22. Separately, acting on a CFIUS referral, President Trump on August 14, 2020 issued an order under Section 721 of the Defense Production Act, 50 U.S.C. § 4565, purporting to direct ByteDance to 12 (Page 13 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 14 of 70 divest from TikTok's U.S. business and U.S. user data. 85 Fed. Reg. 51,297 (the "Divestment Order"). On November 10, 2020, Petitioners petitioned this Court for review of the Divestment Order and underlying CFIUS actions, arguing, among other things, that the government lacked jurisdiction under the statute. See Petition for Review, TikTok Inc. v. CFIUS, No. 20-1444 (D.C. Cir. Nov. 10, 2020). That petition was held in abeyance in February 2021 on the parties' joint motion to allow the parties to negotiate a resolution. The government has filed status reports every 60 days since then, most recently on April 22, 2024. Those status reports have consistently reported that “[t]he parties continue to be involved in ongoing negotiations” and “[a] beyance continues to be appropriate.” See, e.g., Status Report, Tik Tok Inc. v. CFIUS, No. 20-1444 (D.C. Cir. Apr. 22, 2024). 23. Between January 2021 and August 2022, Petitioners and CFIUS engaged in an intensive, fact-based process to develop a National Security Agreement that would resolve the U.S. government's concerns about whether Chinese authorities might be able to access U.S. user data or manipulate content on TikTok, as well as resolve the pending CFIUS During that time, Petitioners and government officials dispute. 13 (Page 14 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 15 of 70 communicated regularly, often several times a week - including several - in-person meetings about the government's concerns and potential solutions. The result was an approximately 90-page draft National Security Agreement with detailed annexes embodying a comprehensive solution addressing the government's national security concerns. Notably, the draft National Security Agreement provided that all protected U.S. user data (as defined in the agreement) would be stored in the cloud environment of a U.S.-government-approved partner, Oracle Corporation, which would also review and vet the TikTok source code. 24. From Petitioners' perspective, all indications were that they were nearing a final agreement. After August 2022, however, CFIUS without explanation stopped engaging with Petitioners in meaningful discussions about the National Security Agreement. Petitioners repeatedly asked why discussions had ended and how they might be restarted, but they did not receive a substantive response. In March 2023, without providing any justification for why the draft National Security Agreement was inadequate, CFIUS insisted that Byte Dance would be required to divest the U.S. TikTok business. (Page 15 of Total) 14

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 16 of 70 25. Since March 2023, Petitioners have explained to CFIUS, in multiple written communications and in-person meetings, that a divestiture of the U.S. TikTok business from the rest of the integrated global Tik Tok platform and business of the sort now required by the Act is not feasible. CFIUS has never articulated any basis for disagreeing with that assessment, offering instead only a conclusory assertion that the reason ByteDance was not divesting was because it was simply unwilling to do so. The Act nonetheless incorporates precisely such an infeasible divestiture standard. C. 26. A Divestiture that Severs TikTok's U.S. Operations From the Rest of the Globally Integrated TikTok Business Is Not Commercially, Technologically, or Legally Feasible. The Act purports to allow Petitioners to avoid a ban by executing a "qualified divestiture." Sec. 2(c). But that alternative is illusory because, as Petitioners have repeatedly explained to CFIUS, the divestiture of the TikTok U.S. business and its severance from the globally integrated platform of which it is an integral part is not commercially, technologically, or legally feasible. (Page 16 of Total) 15

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 17 of 70 - 27. First, a standalone U.S. TikTok platform would not be commercially viable. TikTok and its competitors are globally integrated platforms where content created in one country is available to users in other countries. Indeed, a substantial part of TikTok's appeal is the richness of the international content available on the platform from global sporting events like the Olympics to international K-pop stars from South Korea, as well as videos created by U.S. creators and enjoyed by audiences worldwide. A divestment of the U.S. TikTok platform, without any operational relationship with the remainder of the global platform, would preclude the interoperability necessary to make international content seamlessly available in the U.S. market and vice versa. As a result, the U.S. TikTok platform would become an “island” where Americans would have an experience detached from the rest of the global platform and its over 1 billion users. Such a limited pool of content, in turn, would dramatically undermine the value and viability of the U.S. TikTok business.4 4 The contemplated qualified divestiture would also undercut the important role currently played by American voices in the global conversation ongoing on TikTok. 16 (Page 17 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 18 of 70 28. Second, precipitously moving all TikTok source code development from ByteDance to a new Tik Tok owner would be impossible as a technological matter. The platform consists of millions of lines of software code that have been painstakingly developed by thousands of engineers over multiple years. Although much of this code is basic infrastructure for running the global TikTok platform and has nothing at all to do with TikTok's recommendation algorithm, the statute requires that all of this code be wrested from Petitioners, so that there is no “operational relationship" between ByteDance and the new U.S. platform. Specifically, to comply with the law's divestiture requirement, that code base would have to be moved to a large, alternative team of engineers a team that does not exist and would have no understanding of the complex code necessary to run the platform. It would take years for an entirely new set of engineers to gain sufficient familiarity with the source code to perform the ongoing, necessary maintenance and development activities for the platform. Moreover, to keep the platform functioning, these engineers would need access to ByteDance software tools, which the Act prohibits. Such a fundamental rearchitecting is not - (Page 18 of Total) 17

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 19 of 70 remotely feasible on anything approaching the 270-day timeframe contemplated by the Act. 29. Third, the Chinese government has made clear that it would not permit a divestment of the recommendation engine that is a key to the success of TikTok in the United States. Like the United States,5 China regulates the export of certain technologies originating there. China's export control rules cover “information processing technologies” such as "personal interactive data algorithms.”6 China's official news agency has reported that under these rules, any sale of recommendation algorithms developed by engineers employed by ByteDance subsidiaries in China, including for TikTok, would require a government license. 5 For example, the U.S. Department of Commerce has issued restrictions on the export to China of advanced chips that can be used to train artificial intelligence models. E.g., Implementation of Additional Export Controls: Certain Advanced Computing Items; Supercomputer and Semiconductor End Use; Updates and Corrections, 88 Fed. Reg. 73458 (Oct. 25, 2023) (to be codified at 15 C.F.R. § 732.2 et seq.). 6 See Karen M. Sutter, Cong. Rsch. Serv., IN11524, China Issues New Export Control Law and Related Policies 2 (2020). 7 Paul Mozur, Raymond Zhong & David McCabe, Tik Tok Deal Is Complicated by New Rules From China Over Tech Exports, N.Y. Times (Aug. 29, 2020), https://perma.cc/L6RB-CTT9. 18 (Page 19 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 20 of 70 China also enacted an additional export control law that "gives the Chinese government new policy tools and justifications to deny and impose terms on foreign commercial transactions."8 China adopted these enhanced export control restrictions between August and October 2020, shortly after President Trump's August 6, 2020 and August 14, 2020 executive orders targeting TikTok. By doing so, the Chinese government clearly signaled that it would assert its export control powers with respect to any attempt to sever TikTok's operations from ByteDance, and that any severance would leave TikTok without access to the recommendation engine that has created a unique style and community that cannot be replicated on any other platform today. D. 30. The Act Bans TikTok and Other Byte Dance Applications. On April 24, 2024, the President signed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act. 31. The Act prohibits, on pain of draconian penalties, “online mobile application store[s]" and "internet hosting services" from servicing "foreign adversary controlled application[s]" within the United States. 8 Sutter, supra n.6. 19 (Page 20 of Total)

USCA Case #24-1113 Document #2053212 Filed: 05/07/2024 Page 21 of 70 See Sec. 2(a), 2(d)(1)(A). This includes the "distribution, maintenance, or updating" of a covered application through an online marketplace. Sec. 2(a)(1). 32. Section 2(g) (3) creates two classes of "foreign adversary controlled applications" covered by the Act. 33. The first class singles out only one corporate group: "Byte Dance[] Ltd.,” “TikTok,” their “subsidiar[ies] or successor[s]" that are "controlled by a foreign adversary," or any entity "owned or controlled" by the aforementioned.9 The Act deems any application. operated by these entities a “foreign adversary controlled application," without any finding about why any particular application much less - - every application operated by these entities should be so designated. See Sec. 2(g)(3)(A). 9 “TikTok” is a platform, not a legal entity. Petitioners assume that Congress intended this provision to be a reference to TikTok Inc., and further reserve their rights to amend this Petition to include additional Tik Tok entities to the extent the government takes the position that other entities are covered by this reference. In any event, TikTok Inc. is covered as an entity “owned or controlled" by ByteDance Ltd. 20 (Page 21 of Total)