Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Exposure to outdoor air pollution and its human health outcomes: A scoping review

Contributed equally to this work with: Zhuanlan Sun, Demi Zhu

Roles Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Management Science and Engineering, School of Economics and Management, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Roles Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Comparative Politics, School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China

- Zhuanlan Sun,

- Published: May 16, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550

- Reader Comments

Despite considerable air pollution prevention and control measures that have been put into practice in recent years, outdoor air pollution remains one of the most important risk factors for health outcomes. To identify the potential research gaps, we conducted a scoping review focused on health outcomes affected by outdoor air pollution across the broad research area. Of the 5759 potentially relevant studies, 799 were included in the final analysis. The included studies showed an increasing publication trend from 1992 to 2008, and most of the studies were conducted in Asia, Europe, and North America. Among the eight categorized health outcomes, asthma (category: respiratory diseases) and mortality (category: health records) were the most common ones. Adverse health outcomes involving respiratory diseases among children accounted for the largest group. Out of the total included studies, 95.2% reported at least one statistically positive result, and only 0.4% showed ambiguous results. Based on our study, we suggest that the time frame of the included studies, their disease definitions, and the measurement of personal exposure to outdoor air pollution should be taken into consideration in any future research. The main limitation of this study is its potential language bias, since only English publications were included. In conclusion, this scoping review provides researchers and policy decision makers with evidence taken from multiple disciplines to show the increasing prevalence of outdoor air pollution and its adverse effects on health outcomes.

Citation: Sun Z, Zhu D (2019) Exposure to outdoor air pollution and its human health outcomes: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216550. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550

Editor: Mathilde Body-Malapel, University of Lille, FRANCE

Received: December 15, 2018; Accepted: April 10, 2019; Published: May 16, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Sun, Zhu. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This work received support from Major projects of the National Social Science Fund of China, Award Number: 13&ZD176, Grant recipient: Demi Zhu.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In recent years, despite considerable improvements in air pollution prevention and control, outdoor air pollution has remained a major environmental health hazard to human beings. In some developing countries, the concentrations of air quality far exceed the upper limit announced in the World Health Organization guidelines [ 1 ]. Moreover, it is widely acknowledged that outdoor air pollution increases the incidence rates of multiple diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, respiratory symptoms, asthma, negatively affected pregnancy, and poor birth outcomes [ 2 – 6 ].

The influence of outdoor air pollution exposure and its mechanisms continue to be hotly debated [ 7 – 11 ]. Some causal inference studies have been conducted to examine these situations [ 12 ]; these have indicated that an increase in outdoor air exposure affects people’s health outcomes both directly and indirectly [ 13 ]. However, few studies in the existing literature have examined the extent, range, and nature of the influence of outdoor air pollution with regard to human health outcomes. Thus, such research gaps need to be identified, and related fields of study need to be mapped.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the most commonly used traditional approach to synthesize knowledge, use quantified data from relevant published studies in order to aggregate findings on a specific topic [ 14 ]; furthermore, they formally assesses the quality of these studies to generate precise conclusions related to the focused research question [ 15 ]. In comparison, scoping review is a more narrative type of knowledge synthesis, and it focuses on a broader area [ 16 ] of the evidence pertaining to a given topic. It is often used to systematically summarize the evidence available (main sources, types, and research characteristics), and it tends to be more comprehensive and helpful to policymakers at all levels.

Scoping reviews have already been used to examine a variety of health related issues [ 17 ]. As an evidence synthesis approach that is still in the midst of development, the methodology framework for scoping reviews faces some controversy with regard to its conceptual clarification and definition [ 18 , 19 ], the necessity of quality assessment [ 20 – 22 ], and the time required for completion [ 19 , 21 , 23 ]. Comparing this approach with other knowledge synthesis methods, such as evidence gap map and rapid review, the scoping review has become increasingly influential for efficient evidence-based decision-making because it offers a very broad topic scope [ 15 ].

To our knowledge, few studies have systematically reviewed the literature in the broad field of outdoor air pollution exposure research, especially with regard to related health outcomes. To fill this gap, we conducted a comprehensive scoping review of the literature with a focus on health outcomes affected by outdoor air pollution. The purposes of this study were as follows: 1) provide a systematic overview of relevant studies; 2) identify the different types of outdoor air pollution and related health outcomes; and 3) summarize the publication characteristics and explore related research gaps.

Materials and methods

The methodology framework used in this study was initially outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [ 23 ] and further advanced by Levac et al. [ 20 ], Daudt et al. [ 21 ], and the Joanna Briggs Institute [ 24 ]. The framework was divided into six stages: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; collating, summarizing and reporting the results; and consulting exercise.

Stage one: Research question identification

As recommended, we combined broader research questions with a clearly articulated scope of inquiry [ 20 ]; this included defining the concept, target population, and outcomes of interest in order to disseminate an effective search strategy. Thus, an adaptation of the “PCC” (participants, concept, context) strategy was used to guide the construction of research questions and inclusion criteria [ 24 ].

Types of participants.

There were no strict restrictions on ages, genders, ethnicity, or regions of participants. Everyone, including newborns, children, adults, pregnant women, and the elderly, suffer from health outcomes related to exposure to outdoor air pollution; hence, all groups were included in the study to ensure that the inquiry was sufficiently comprehensive.

The core concept was clearly articulated in order to guide the scope and breadth of the inquiry [ 24 ]. A list of outdoor air pollution and health outcome related terms were compiled by reviewing potential text words in the titles or abstracts of the most pertinent articles [ 25 – 33 ]; we also read the most cited literature reviews on air pollution related health outcomes. To classify the types of air pollution and health outcomes, we consulted researchers from different air pollution related disciplines. The classified results are shown in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t001

Our scoping review included studies from peer-reviewed journals. There were no restrictions in terms of the research field, time period, and geographical coverage. The intended audiences of our scoping review were researchers, physicians, and public policymakers.

Stage two: Relevant studies identification

We followed Joanna Briggs Institute’s instructions [ 24 ] to launch three-step search strategies to identify all relevant published and unpublished studies (grey literature) across the multi-disciplinary topic in an iterative way. The first step included a limited search of the entire database using keywords relevant to the topic and conducting an abstract and indexing categorizations analysis. The second step was a further search of all included databases based on the newly identified keywords and index terms. The final step was to search the reference list of the identified reports and literatures.

Electronic databases.

We conducted comprehensive literature searches by consulting with an information specialist. We searched the following three electronic databases from their inception until now: PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. The language of the studies included in our sample was restricted to English.

Search terms.

The search terms we used were broad enough to uncover any related literature and prevent chances of relevant information being overlooked. This process was conducted iteratively with different search item combinations to ensure that all relevant literature was captured ( S1 Table ).

The search used combinations of the following terms: 1) outdoor air pollution (ozone, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, PM 2.5 , PM 10 , total suspended particle, suspended particulate matter, toxic air pollutant, volatile organic pollutant, nitrogen oxide) and 2) health outcomes (asthma, lung cancer, respiratory infection, respiratory disorder, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, heart rate variability, heart attack, cardiopulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, blood coagulation, deep vein thrombosis, stroke, morbidity, hospital admission, outpatient visit, emergency room visit, mortality, DNA methylation change, neurobehavioral function, inflammatory disease, skin disease, abortion, Alzheimer’s disease, disability, cognitive function, Parkinson’s disease).

Additional studies search.

Key, important, and top journals were read manually, reference lists and citation tracing were used to collect studies and related materials, and suggestions from specialists were considered to guarantee that the research was as comprehensive as possible.

Bibliographies Management Software (Mendeley) was used to remove duplicated literatures and manage thousands of bibliographic references that needed to be appraised to check whether they should be included in the final study selection.

Our literature retrieval generated a total of 5759 references; the majority of these (3567) were found on the Scopus electronic database, which emphasized the importance of collecting the findings on this broad topic.

Stage three: Studies selection

Our study identification picked up a large number of irrelevant studies; we needed a mechanism to include only the studies that best fit the research question. The study selection stage should be an iterative process of searching the literature, refining the search strategy, and reviewing articles for inclusion. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria were discussed by the team members at the beginning of the process, then two inter-professional researchers applied the criteria to independently review the titles and abstracts of all studies [ 21 ]. If there were any ambiguities, the full article was read to make decision about whether it should be chosen for inclusion. When disagreements on study inclusion occurred, a third specialist reviewer made the final decision. This process should be iterative to guarantee the inclusion of all relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria used in our scoping study ensured that the articles were considered only if they were: 1) long-term and short-term exposure, perspective or prospective studies; 2) epidemiological time series studies; 3) meta-analysis and systematic review articles rather than the primary studies that contained the main parameters we were concerned with; 4) economic research studies using causality inference with observational data; and 5) etiology research studies on respiratory disease, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

Articles were removed if they 1) focused exclusively on indoor air pollution exposure and 2) did not belong to peer-reviewed journals or conference papers (such as policy documents, proposals, and editorials).

Stage four: Data charting

The data extracted from the final articles were entered into a “data charting form” using the database, programmed Excel, so that the following relevant data could be recorded and charted according to the variables of interest ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t002

Stage five: Results collection, summarization, and report

The extracted data were categorized into topics such as people’s health types and regions of diseases caused by outdoor air exposure. Each reported topic should be provided with a clear explanation to enable future research. Finally, the scoping review results were tabulated in order to find research gaps to either enable meaningful research or obtain good pointers for policymaking.

Stage six: Consultation exercise

Our scoping review took into account the consultation phase of sharing preliminary findings with experts, all of whom are members of the Committee on Public Health and Urban Environment Management in China. This enabled us to identify additional emerging issues related to health outcomes.

The original search was conducted in May of 2018; the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases were searched, resulting in a total of 5759 potentially relevant studies. After a de-duplication of 1451 studies and the application of the inclusion criteria, 3027 studies were assessed as being irrelevant and excluded based on readings of the titles and the abstracts. In the end, 1281 studies were assessed for in-depth full-text screening. To prevent overlooking potentially relevant papers, we manually screened the top five impact factor periodicals in the database we were searching. We traced the reference lists and the cited literatures of the included studies, and then we reviewed the newly collected literatures to generate more relevant studies. Further, after preliminary consultation with experts, we included studies on two additional health outcome categories, pregnancy and children and mental disorders. Hence, 214 more potential studies were included during this process. Besides, 379 original studies of the inclusive meta-analysis and systematic review studies were removed for duplication. In total, 1116 studies were included for in-depth full-text screening analysis and 799 eligible studies were included in the end. The detailed articles selection process was shown in Fig 1 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.g001

The included air pollution related health outcome studies increased between 1992 and 2018, as shown in Fig 2 . Most studies were published in the last decade and more than 75% of studies (614/76.9%) were published after 2011.

The included studies increased during this period, more than 75% of studies were published after 2011.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.g002

The general characteristics summary of all included studies are shown in Table 3 . Most studies were carried out in Asia, Europe and North America (280/35.0%, 261/32.7% and 219/27.4%, respectively). According to the category system of journal citation reports (JCR) in the Web of Science, 323/40.4% of all studies on health outcomes came from environmental science, 213/26.7% came from the field of medicine, and 24/3.0% were from economics. The top three research designs of the included studies were cohort studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and time series studies (116/14.5%, 107/13.4% and 76/9.5%, respectively). Almost all included studies were published in journals (794/99.4%). The lengths of the included studies ranged from four pages [ 34 ] to over thirty-nine pages [ 35 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t003

Regions of studies

Table 4 outlines the locations in which health outcomes were affected by outdoor air pollution. The continents of Asia (277/34.7%), Europe (219/27.4%), and North America (168/21.0%) account for most of these studies. As the word cloud in Fig 3 illustrates, most of the included studies had been mainly conducted in the United States and China. About 62.8% of the studies (502) had been especially conducted in developed countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t004

Word cloud representing the country of included studies, the size of each term is in proportion to its frequency.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.g003

Most authors (573/799) evaluated the air pollution health outcomes of their own continent, at a proportion of 71.7%.

Types of air pollution and related health outcomes

We categorized the health outcomes, by consulting with experts, into respiratory diseases, chronic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, health records, cancer, mental disorders, pregnancy and children, and other diseases ( Table 5 ). We also divided the outdoor air pollution into general air pollution gas, fine particulate matter, other hazardous substances, and a mixture of them.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t005

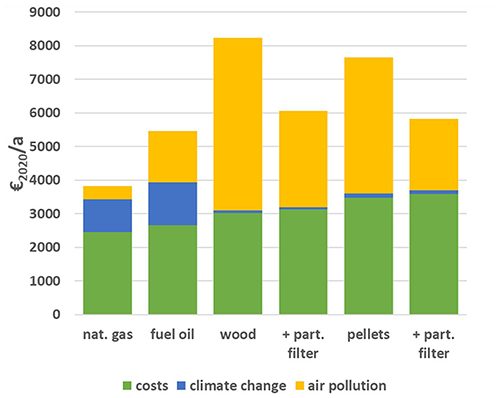

Most of the health records showed that mortality (163/286; 57.0%) was the most common health outcome related to outdoor air pollution, as is visually represented in Fig 4 . Respiratory diseases (e.g., asthma and respiratory symptoms) and cardiovascular diseases (e.g., heart disease) that resulted from exposure to outdoor air pollution were also common (69/199, 63/199 and 23/90; or 34.7%, 31.7% and 25.6%; respectively).

Word cloud representing the health outcomes of included studies, the size of each term is in proportion to its frequency.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.g004

Types of affected groups

The population of included studies was categorized into seven subgroups: birth and infant, children, women and pregnancy, adults, elderly, all ages and not specified ( Table 6 ). The largest air pollution proportion fell under the groups of all ages and children (261/799; 32.7% and 165/799; 20.7%), health outcomes of respiratory diseases in children account for the largest groups (114/199; 57.3%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t006

There were 121 research studies in the “Not Specified” group. As shown in Table 6 , the “Birth & Infant,” “Women & Pregnancy,” “Children,” and “elderly” groups occupied the subject areas of more than half of the total included studies, which means that air pollution affected these population groups more acutely. Moreover, age is a confounding factor for the prevalence of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. However, there were only 2 studies (2/38, 5.3%) on cancer and 14 studies (14/90, 15.6%) on cardiovascular diseases in the elderly group.

Summary of results

Of all included studies, 95.2% reported at least one statistically positive result, 4.4% were convincingly negative, and only 0.4% showed ambiguous results ( Table 7 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.t007

There were 27 primary studies that showed no association between air pollution and disease, including cancer (n = 1), chronic diseases (n = 1), cardiovascular diseases (n = 6), health records (n = 7), pregnancy and children (n = 2), respiratory diseases (n = 6), mental disorders (n = 1), and other diseases (n = 3). Moreover, eight meta-analyses showed no evidence for any association between air pollution and disease prevalence (childhood asthma, chronic bronchitis, asthma, cardio-respiratory mortality, acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury, mental disorder, cardiovascular disease, and daily respiratory death). Three meta-analyses showed ambiguous results for mental health, venous thromboembolism, and hypertension.

Our scoping review provided an overview on the subject of outdoor air pollution and health outcomes. We adhered to the methodology outlined for publishing guidelines and used the six steps outlined by the scoping review protocol. The guiding principle ensured that our methods were transparent and free from potential bias. The strengths of the included studies are that they tend to focus on large sample sizes and broad geographical coverage. This research helped us to identify research gaps and disseminate research findings [ 23 ] to policymakers, practitioners, and consumers for further missing or potentially valuable investigations.

Principal findings

Among the included studies, we identified various health outcomes of outdoor air pollution, including respiratory diseases, chronic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, health records, cancer, mental disorders, pregnancy and children, and other diseases. Among them, asthma in respiratory diseases and mortality in health records were the most common ones. The study designs contained cohort, meta-analysis, time series, crossover, cross-sectional, and other qualitative methods. In addition, we included economically relevant studies [ 12 , 36 , 37 ] to investigate the causal inference of outdoor air pollution on health outcomes. Further, pregnancy and children, mental disorders, and other diseases are health outcomes that might have uncertain or inconsistent effects. For example, Kirrane et al. [ 38 ] reported that PM 2.5 had positive associations with Parkinson’s disease; however, some studies report that there is no statistically significant overall association between PM exposure and such diseases [ 39 ]. Overall, the majority of these studies suggested a potential positive association between outdoor air pollution and health outcomes, although several recent studies revealed no significant correlations [ 40 – 42 ].

Time frame of included studies

The time frame of included studies is one of the most important characteristics of air pollution research. Even in the same country or region, industrialization and modernization caused by air pollution is distinguished between different time periods [ 43 , 44 ]. In addition, the more the public understands environment science, the more people will take preventative measures to protect themselves. This is also influenced by time. Although air pollution should not be seen as an inevitable side effect of economic growth, time period should be considered in future studies. The publication trends with regard to air pollution related health outcome research increased sharply after 2010. In recent times, published studies have begun to pay more attention to controlling confounding factors such as socioeconomic factors and human behavior.

Population and country

More than 50% of the studies on the relationship between air pollution and health outcomes originated from high income countries. There was less research (<25%) from developing countries and poor countries [ 45 – 48 ], which may result from inadequate environmental monitoring systems and public health surveillance systems. Less cohesive policies and inadequate scientific research may be another reason. In this regard, stratified analysis by regional income will be helpful for exploring the real estimates. It is reported that the stroke incidence is largely associated with low and middle income countries rather than with high income countries [ 49 ]. More studies are urgently needed in highly populated regions, such as Eastern Asia and North and Central Africa.

It is worth noting that rural and urban differences in air pollution research have been neglected. There are only eight studies focused on the difference of spatial variability of air pollution [ 50 – 57 ]. Variation is common even across relatively small areas due to geographical, topographical, and meteorological factors. For example, an increase in PM 2.5 in Northern China was predominantly from abundant coal combustion used for heating in the winter months [ 58 ]. These differences should be considered with caution by urbanization and by region. Data analysis adjustment for spatial autocorrelation will provide a more accurate estimate of the differences in air. What’s more, in some countries such as China, migrants are not able to access healthcare within the cities; this has resulted in misleading conclusions about a “healthier” population and null based bias was introduced [ 59 ].

Other studies (including systematic reviews and economic studies) on outdoor air pollution

Our scoping review included a large number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Of the included 107 systematic review and meta-analyses, the most discussed topics were respiratory diseases influenced by mixed outdoor air pollution [ 60 – 62 ]. Little systematic review research focused on chronic diseases, cancer, and mental disorders, which are current research gaps and potential research directions. A large overlap remains between the primary studies included in the systematic reviews. However, some systematic reviews that focused on the same topic have conflicting results, which were mainly caused by different inclusion criteria and subgroup analyses [ 63 , 64 ]. To solve this problem, it is critical that reporting of systematic reviews should retrieve all related published systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

As for the 24 included economic studies, two kinds of health outcomes—morbidity [ 65 ] and economic cost [ 66 ]—were discussed separately using regression approaches. The economic methods were different from those used in the epidemiology; the study focused on causal inference and provided a new perspective for examining the relevant environmental health problems. Furthermore, meta-regression methodology, an economic synthesis approach, proved to be very effective for evaluating the outcomes in a comprehensive way [ 67 ].

Diagnostic criteria for diseases

The diagnostic criteria for diseases forms an important aspect of health-related outcomes. The diagnostic criteria for stroke and mental disorders might be less reliable than those for cancer, mobility, and cardiovascular diseases [ 68 ]. Few studies provided detailed disease diagnostic information on how the disease was measured. Thus, the overall effect estimation of outdoor air pollution might be overestimated. It is recommended that ICD-10 or ICD-11 classification should be adopted as the health outcome classification criterion to ensure consistency among studies in different disciplines considered in future research [ 69 ].

In spite of these broad disease definitions, studies in healthy people or individuals with chronic diseases were not conducted separately. People with chronic diseases were more susceptible to air pollution [ 70 ]. It is obvious that air pollution related population mobility might be underestimated. However, the obvious association of long-term exposure to air pollution with chronic disease related mortality has been reported by prospective cohort studies [ 71 ]. It should be translated to other diverse air pollution related effect research. The population with pre-existing diseases should be analyzed as subgroups.

Except for the overall population, subgroups of people with outdoor occupations and athletes [ 72 , 73 ], sensitive groups such as infants and children, older adults [ 74 , 75 ], and people with respiratory or cardiovascular diseases, should be analyzed separately.

Measurement of personal exposure

The measurement of personal exposure to air pollutants (e.g., measurement of errors associated with the monitoring instruments, heterogeneity in the amount of time spent outdoors, and geographic variation) was lacking in terms of accurate determination. There is a need for clear reporting of these measurements. The key criterion to determine if there is causal relationship between air pollution and negative health outcomes was that at least one aspect of these could be measured in an unbiased manner.

Pollutant dispersion factor

It is well known that the association between air pollution and stroke, and respiratory and cardiovascular disease subtype might be caused by many other factors such as temperature, humidity, season, barometric pressure, and even wind speed and rain [ 76 – 78 ]. These confounding factors related to aspects of energy, transportation, and socioeconomic status, may explain the varying effect size of the association between air pollution and diseases.

While the associations reported in epidemiological studies were significant, proving a causal relationship between the different air pollutants affected by any other factors and adverse effects has been more challenging. To avoid bias, these modifier effects should be compared with previous localized studies. In fact, how the confounding variables account for the heterogeneity should be explored by case-controlled study design or other causal interference research designs.

Study limitations

The following limitations should not be overlooked. First, scoping reviews are based on a knowledge synthesis approach that allows for the mapping of gaps in the existing literature; however, they lack quality assessment for the included studies, which may be an obstacle for precise interpretation. Some improvements have been made by adding a quality assessment [ 15 , 22 , 79 ] to increase the reliability of the findings, and other included studies control for quality by including only peer-reviewed publications [ 80 ]; however, this is not a requirement for scoping reviews. While our paper aimed to comprehensively present a broader range of global-level current published literatures related to outdoor air pollution health outcomes, we did not assess the quality of the analyzed literature. The conclusions of this scoping review were based on the existence of the selected studies rather than their intrinsic qualities.

Second, bias is an inevitable problem from the perspectives of languages, disciplines, and literatures in knowledge synthesis. We included literatures from electronic databases, key journals, and reference lists to avoid “selection bias” and then included unpublished literature to avoid “publication bias”; further, we also conscientiously sampled among the studies to ensure that there was a safeguard against “researcher bias.” We only took English language articles into account because of the cost and time involved in translating the material, which might have led to a potential language bias [ 23 ]. However, in scoping reviews, language restriction does not have the importance that it does in meta-analysis [ 81 ].

Conclusions

In all, the topic of outdoor air pollution exposure related health outcomes is discussed across multiple-disciplines. The various characteristics and contexts of different disciplines suggest different underlying mechanisms worth of the attention of researchers and policymakers. The presentation of the diversity of health outcomes and its relationship to outdoor exposure air pollution is the purpose of this scoping review for new findings in future investigations.

Supporting information

S1 table. literature search strategies..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.s001

S2 Table. PRISMA-ScR checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216550.s002

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miaomiao Liu, an assistant professor in School of the Environment of Nanjing University, for her valuable advice with regard to this article.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 24. The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Joanne Briggs Inst. 2015; 1–24.

Article

- Volume 22, issue 7

- ACP, 22, 4615–4703, 2022

- Peer review

- Related articles

Advances in air quality research – current and emerging challenges

Ranjeet s. sokhi, nicolas moussiopoulos, alexander baklanov, john bartzis, isabelle coll, sandro finardi, rainer friedrich, camilla geels, tiia grönholm, tomas halenka, matthias ketzel, androniki maragkidou, volker matthias, jana moldanova, leonidas ntziachristos, klaus schäfer, peter suppan, george tsegas, greg carmichael, vicente franco, steve hanna, jukka-pekka jalkanen, guus j. m. velders, jaakko kukkonen.

This review provides a community's perspective on air quality research focusing mainly on developments over the past decade. The article provides perspectives on current and future challenges as well as research needs for selected key topics. While this paper is not an exhaustive review of all research areas in the field of air quality, we have selected key topics that we feel are important from air quality research and policy perspectives. After providing a short historical overview, this review focuses on improvements in characterizing sources and emissions of air pollution, new air quality observations and instrumentation, advances in air quality prediction and forecasting, understanding interactions of air quality with meteorology and climate, exposure and health assessment, and air quality management and policy. In conducting the review, specific objectives were (i) to address current developments that push the boundaries of air quality research forward, (ii) to highlight the emerging prominent gaps of knowledge in air quality research, and (iii) to make recommendations to guide the direction for future research within the wider community. This review also identifies areas of particular importance for air quality policy. The original concept of this review was borne at the International Conference on Air Quality 2020 (held online due to the COVID 19 restrictions during 18–26 May 2020), but the article incorporates a wider landscape of research literature within the field of air quality science. On air pollution emissions the review highlights, in particular, the need to reduce uncertainties in emissions from diffuse sources, particulate matter chemical components, shipping emissions, and the importance of considering both indoor and outdoor sources. There is a growing need to have integrated air pollution and related observations from both ground-based and remote sensing instruments, including in particular those on satellites. The research should also capitalize on the growing area of low-cost sensors, while ensuring a quality of the measurements which are regulated by guidelines. Connecting various physical scales in air quality modelling is still a continual issue, with cities being affected by air pollution gradients at local scales and by long-range transport. At the same time, one should allow for the impacts from climate change on a longer timescale. Earth system modelling offers considerable potential by providing a consistent framework for treating scales and processes, especially where there are significant feedbacks, such as those related to aerosols, chemistry, and meteorology. Assessment of exposure to air pollution should consider the impacts of both indoor and outdoor emissions, as well as application of more sophisticated, dynamic modelling approaches to predict concentrations of air pollutants in both environments. With particulate matter being one of the most important pollutants for health, research is indicating the urgent need to understand, in particular, the role of particle number and chemical components in terms of health impact, which in turn requires improved emission inventories and models for predicting high-resolution distributions of these metrics over cities. The review also examines how air pollution management needs to adapt to the above-mentioned new challenges and briefly considers the implications from the COVID-19 pandemic for air quality. Finally, we provide recommendations for air quality research and support for policy.

- Article (PDF, 14780 KB)

- Included in Encyclopedia of Geosciences

- Article (14780 KB)

- Full-text XML

Sokhi, R. S., Moussiopoulos, N., Baklanov, A., Bartzis, J., Coll, I., Finardi, S., Friedrich, R., Geels, C., Grönholm, T., Halenka, T., Ketzel, M., Maragkidou, A., Matthias, V., Moldanova, J., Ntziachristos, L., Schäfer, K., Suppan, P., Tsegas, G., Carmichael, G., Franco, V., Hanna, S., Jalkanen, J.-P., Velders, G. J. M., and Kukkonen, J.: Advances in air quality research – current and emerging challenges, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 4615–4703, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-4615-2022, 2022.

We wish to dedicate this article to the following eminent scientists who made immense contributions to the science of air quality and its impacts: Paul J. Crutzen (1933–2021), atmospheric chemist, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995; Mario Molina (1943–2020), atmospheric chemist, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995; Samohineeveesu Trivikrama Rao (1944–2021), air pollution meteorology and atmospheric modelling; Kirk Smith (1947–2020), global environmental health; Martin Williams (1947–2020), air quality science and policy; Sergej Zilitinkevich (1936–2021), atmospheric turbulence, awarded the IMO Prize 2019.

Air pollution remains one of the greatest environmental risks facing humanity. WHO (2016) estimated that over 90 % of the global population is exposed to air quality that does not meet WHO guidelines, and Shaddick et al. (2020) report that 55 % of the world's population were exposed to PM 2.5 concentrations that were increasing between 2010 and 2016. Shaddick et al. (2020) also highlighted marked inequalities between global regions, with decreasing trends in annual average population-weighted concentrations in North America and Europe but increasing trends in central and southern Asia. WHO (2016) has evaluated that approximately 7 million people died prematurely in 2012 throughout the world as a result of air pollution exposure originating from emissions from outdoor and indoor anthropogenic sources. The recent update from the World Health Organization (WHO) of air quality guidelines (WHO, 2021) has emphasized the need to further curtail air pollution emissions and improve air quality globally.

Over the past decade there have been significant developments in the field of air quality research spanning improvements in characterizing sources and emissions of air pollution, new measurement technologies offering the possibility of low-cost sensors, advances in air quality prediction and forecasting, understanding interactions with meteorology and climate, and exposure assessment and management. However, there has not been a broader and comprehensive review of recent developments that push the boundaries of air quality research forward. This was recognized as a major gap in the literature at the last International Conference on Air Quality – Science and Application held online due to the COVID 19 restrictions during 18–26 May 2020. While the concept of this review originated at the International Conference on Air Quality and was stimulated by the presentations and discussions at the conference, this article has been extended to incorporate a wider landscape of research literature in the field of air quality, spanning in particular the developments occurring over the last decade. It is hoped that such a review will help to pave the path for further research in key areas where significant gaps of knowledge still exist and also to make recommendations to guide the direction for future research within the wider community. Although this paper has been written to be accessible to readers from a wide scientific and policy background, it does not seek to provide an introduction to the topic of air quality science. For readers less familiar with the research area, an introductory lecture with a focus on air quality in megacities has been published by Molina (2021). There are also other recent specific reviews, e.g. Manisalidis et al. (2020) on health impacts and Fowler et al. (2020) on air quality developments. This section begins with a short historical perspective on air quality research, before providing the underlying rationale for the key areas considered in this paper.

1.1 A brief historical perspective

In order to provide context to the topics considered in this review, this section briefly touches upon developments of air quality research since the last century. For a more thorough historical survey of air quality issues, the reader is referred to Fowler et al. (2020). Over the previous century there have been a number of landmark events of elevated air pollution that have brought air quality increasingly to prominence, especially in relation to the adverse health impacts. It has been well-known since the early 1900s that cold weather in winter can lead to increased mortality (e.g. Russell, 1926).

The perception that air pollution can have severe health impacts significantly changed when a high-air-pollution episode occurred from 1–5 December 1930 over an industrial town in the Meuse Valley in Belgium (Firket, 1936). The atmospheric conditions were foggy and stagnant. A large proportion of the population experienced acute respiratory symptoms; in addition, health conditions of people with pre-existing cardiorespiratory problems worsened (e.g. Nemery et al., 2001; Anderson, 2009). A similar event was recorded in Donora, Pennsylvania, USA, during October 1948, reported by Schrenk (1949). Although air pollution was generally treated as a nuisance, this “unusual episode” along with that over the Meuse Valley raised awareness and acceptance of the seriousness of air pollution for human health. Both air pollution events, Meuse Valley and Donora, were associated with air pollution from industrial emissions, which accumulated during cold winter periods exhibiting atmospheric stagnation caused by thermal inversions.

The so-called “Great London Smog” occurred from 5–9 December 1952, when similar stagnant atmospheric conditions were prevalent. However, in this case the cause of the severe air pollution was mainly the burning of low-grade, sulfur-rich coal for home heating (e.g. Anderson, 2009). Estimates of deaths resulting from this smog episode range from 4000 to 12 000 (e.g. Stone, 2002).

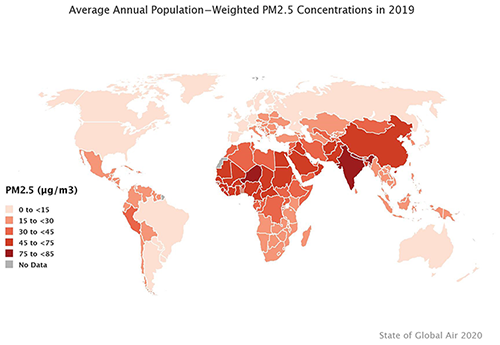

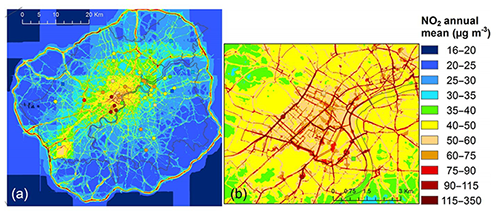

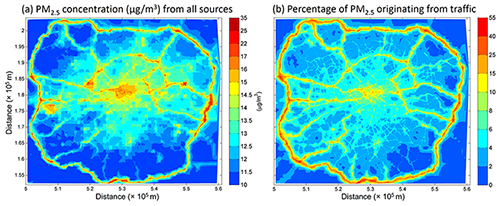

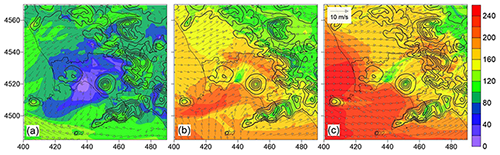

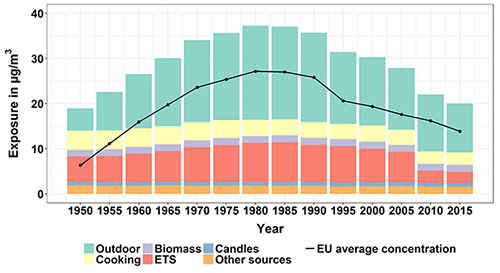

Since these historical events, the prominence of air pollution sources has changed from industrial and heating to road traffic and become a global threat to health. Trends of air pollution emissions over the past decades have been markedly different for different regions of the world, which has led to similar disparities in air quality concentrations (e.g. Sokhi, 2012). These disparities still exist, as shown in Fig. 1. Spatial distributions in this figure are based on recent analysis showing the large variations in population-weighted annual mean PM 2.5 concentrations across the globe. Commonly, now some of the highest concentrations occur in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America as reported by Health Effects Institute (HEI, 2020).

Figure 1 Global distribution of population-weighted annual PM 2.5 concentrations for 2019 (HEI, 2020). Figure produced from https://www.stateofglobalair.org/data/#/air/map (last access: 10 December 2021).

As the recognition of poor air quality has increased, so has the need for the capability to assess levels of key air pollutants not only through monitoring but also through modelling. Historically, although air pollution was obviously poor prior to the first World War (WWI), the primary impetus for development of transport and dispersion (T&D) models during and after WWI was the widespread use of chemical weapons. Fundamental theoretical advances were made by Lewis Fry Richardson, George Keith Batchelor, and many other famous fluid dynamicists. The earliest models were analytical (e.g. Gaussian and K-theory) models used for surface boundary layer releases. With the advent of nuclear weapons in WWII, new emphasis was placed on plume rise and dispersion of large thermal radiological explosions. Thus, the full troposphere and stratosphere had to be modelled.

Later in the 1980s the first investigations came up about the atmospheric consequences of a hypothetical nuclear war initiated by Paul Crutzen (Crutzen and Birks, 1982) and others (Aleksandrov and Stenchikov, 1983; Turco et al., 1983). The concept of a nuclear winter was created. It is one of the first examples that enormous emissions of dust into the atmosphere cause global effects and catastrophic long-term climate change. Also, the nuclear winter scenario was examined in recent years with current model tools for certain nuclear war scenarios (Robock et al., 2007; Toon et al., 2019).

Deposition (wet and dry) was a main concern for many radiological substances, especially for accidental plume dispersion monitoring and modelling of nuclear power plants. In the US, a major change was the introduction of the Clean Air Act in the 1970s. A similar legislation was also issued in other countries. This effort initially focused on T&D models for industrial sources, such as the stacks of fossil power plants. The first applied models were analytical plume rise and Gaussian T&D models. Soon computer codes were written to solve these equations and produce outputs at many spatial locations and for every hour of the year.

1.2 Sources and emissions of air pollutants

From a human health perspective, the key emission sources are those affecting concentration of particulate matter and its size fractions (PM 2.5 and PM 10 ), but also sources affecting other air pollutants, such as ozone and nitrogen dioxide (NO 2 ), especially in highly populated urban areas. Sources in the direct vicinity of urban areas could also be considered especially important, including vehicular traffic and shipping, local industrial sources, various abrasive processes, and residential and commercial heating.

An important component of PM is secondary; regional sources of the precursors of secondary PM are therefore of major importance. These include volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen dioxide (NO 2 ), sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ), and ammonia (NH 3 ), the first two also being precursors of ozone (O 3 ). Important regional precursor sources are biogenic and industrial emissions of VOCs, agriculture (NH 3 ), road traffic (nitrogen oxides, NO x = NO + NO 2 ), shipping ( NO x and SO 2 ) , and industrial and power generation sources, along with biomass burning and forest fires (VOC, NO x , also primary PM). An important source of PM is the resuspension of dust, especially in arid regions and seasonally also in areas with intensive agriculture.

While Europe and many other parts of the world have experienced decreasing anthropogenic emissions since 1990, climate change and its associated impacts can lead to an increase in dust and wildfire emissions, as a result of increased drought and desertification. Climate change is also expected to lead to significantly higher biogenic VOC emissions in different regions, e.g. Arctic and China (Kramshøj et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019), also from urban vegetation (Churkina et al., 2017).

The emission inventory work in Europe is harmonized through the official reporting of EU member states of their emissions to the European Commission through an e-reporting scheme (Implementing Provisions for Reporting, IPR of EU Air Quality Directive, 2008/50/EC). The methodologies applied by the individual member states can, however, differ, which can sometimes bring inconsistencies into the reported national emissions. Within the last decade the EU-funded MACC project and the on-going Copernicus service have been developing consistent European-wide and global gridded emission inventories, which are suitable for air quality modelling. The access to the different inventories and analysis of differences have been facilitated by centralized databases like Emissions of atmospheric Compounds and Compilation of Ancillary Data (ECCAD, https://eccad.aeris-data.fr/ , last access: 7 July 2021).

Developing innovative methods to refine the emission inventories feeding the models and conducting studies to discriminate the role of different sources in local air quality have become essential to reduce uncertainties in predictions of urban air quality and help target effective abatement measures (Borge et al., 2014). The emission compilation that needs to be carried out also requires (i) the involvement of all stakeholders (e.g. citizens, decision-makers, service providers, and industrialists) and (ii) the implementation of dedicated and specific tools for assessing quality of the urban environment. This type of research can be used for quantifying the impacts of different emission control scenarios and supporting incentive policies (Fulton et al., 2015).

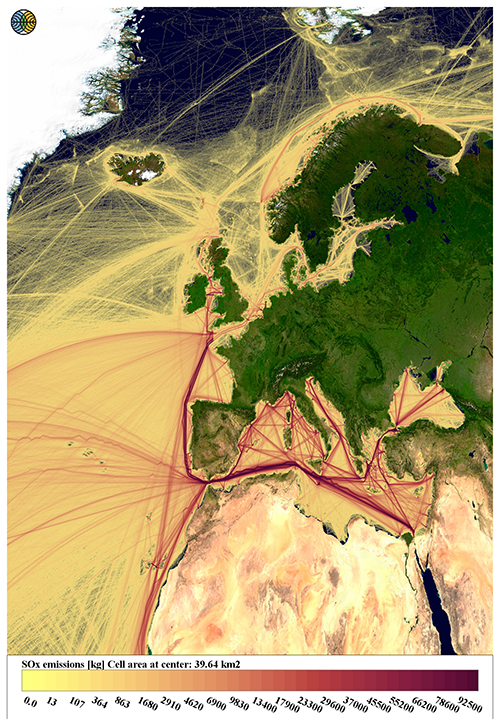

One area that has been receiving increased attention recently is ship emissions, which are an important source of air pollution, especially in coastal areas and harbour cities. Detailed bottom-up emission inventories based on ship position data have been established for SO 2 , NO x , PM, carbon monoxide (CO), and VOCs for various marine regions and also globally (Jalkanen et al., 2009, 2012, 2016; Aulinger et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2017). Despite these advances, the evaluation of the shipping emissions for products of incomplete combustion, such as black carbons (BC), CO, and VOCs, is uncertain, as these may depend on characteristics which are not known accurately, such as the service history of ships. Regional model applications have quantified the contribution of shipping to air pollution to be of the order of up to 30 %, depending on pollutant and region (e.g. Matthias et al., 2010; Jonson et al., 2015; Aulinger et al., 2016; Karl et al., 2019a; Kukkonen et al., 2018, 2020a). More recent studies focus on the harbour and city scale, where relative contributions from ships to NO 2 concentrations may be even higher (Ramacher et al., 2019, 2020). Effects of in-plume chemistry, e.g. regarding the NO x removal and secondary aerosol formation, are not sufficiently well considered in larger-scale dispersion models (e.g. Prank et al., 2016).

1.3 Air quality in cities

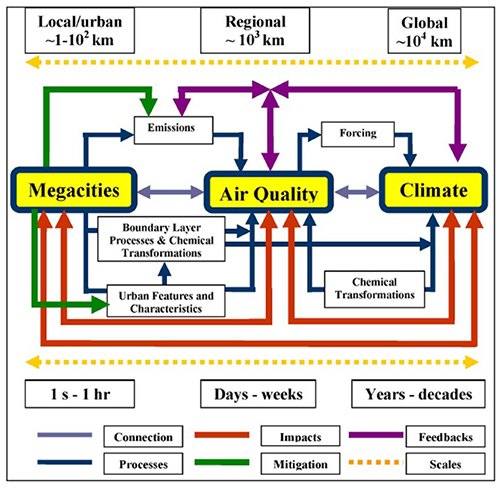

Extensive and growing urban sprawl in different cities of the world is leading to environmental degradation and the depletion of natural resources, including the availability of arable land, thereby resulting in per capita increases of resource use and greenhouse gas emissions as well as air pollution, with significant impacts on health (WHO, 2016). Urban features have a profound influence on air quality in cities due to diurnal changes in urban air temperature; the urban heat island, which develops in particular during heat waves (Halenka et al., 2019); stable stratification and air stagnations; and wind flow and turbulence near and around streets and buildings affecting air pollution hotspots. Climate change will modify urban meteorology patterns which will affect air quality in cities and may even affect atmospheric chemistry reaction rates. The relative role of urban meteorology and climate compared to local emissions and chemistry is complex, non-linear, and subject to continued research, especially with boundary layer feedback (Baklanov et al., 2016).

With air quality standards being regularly exceeded in many urban areas across the globe, air quality issues are today strongly centred on the phenomena of proximity to emitters such as traffic – or certain industrial activities present in urban areas – but they also call for better understanding of contributions from long-range regional, diffuse, or specific local sources (e.g. residential wood combustion and maritime traffic) to the daily exposure of city dwellers (e.g. EEA, 2020b). In particular, the prevalent issue of individual exposure calls for a better understanding of the variability of concentrations at street level and the dispersion of emissions in the built environment. However, the approach implemented should not only be local, since urban air quality management involves a set of scales going beyond the city limits, in terms of the economic, societal, or logistical levers involved, but also include the interplay of pollutant sources and transport extending to regional and even global scales.

Beyond the scales of governance and urban functioning, it becomes essential to take into account the fact that scale interactions also exist in a geophysical context. The urban dweller has become especially exposed and vulnerable to the impacts of natural disasters, weather, and climate extreme events and their environmental consequences. These events often result in domino effects in the densely populated, complex urban environment in which system and services have become interdependent. There has never been a bigger need for user-focused urban weather, climate, water, and related environmental services in support of safe, healthy, and resilient cities (Baklanov et al., 2018b; Grimmond et al., 2020). The 18th World Meteorological Congress (2019) noted the current rapid urbanization and recognized the need for an integrated approach providing weather, climate, water, and related environmental services tailored to the urban needs (WMO, 2019).

1.4 Measuring air pollution

Measurements in the atmosphere are necessary not only for air quality monitoring but also for different purposes in weather forecast and climate change study, energy production, agriculture, traffic, industry, health protection, or tourism (e.g. Foken, 2021). Additional areas of application include the detection of emissions into the atmosphere, disaster monitoring, and the initialization and evaluation of modelling. Depending on the different objectives, in situ measuring, and ground-based, aircraft-based, and space-based remote sensing techniques and integrated measuring techniques are available. Satellite observations are a growing field of development due to increasingly small and thus cost-effective platforms (down to nanosatellites). Another area of growth is the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for air pollution measurements (Gu et al., 2018).

Networks of ground-level measurements with continuous monitoring stations remain a major effort, but the coverage is starkly regionally dependent and with scarce measurements in the continent of Africa (Rees et al., 2019; Bauer et al., 2019).

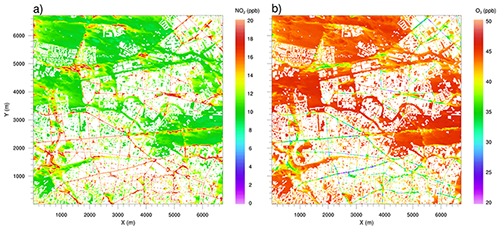

Over the past decade, there has been increasing recognition that measuring air pollution at outdoor locations may not necessarily reflect the health impact on individuals or populations. The research should therefore be directed to the evaluation of both personal exposure and dynamic population exposure (Kousa et al., 2002; Soares et al., 2014). Temporal concentration and location information is needed on air pollution concentrations at all the relevant outdoor and indoor microenvironments. The actual exposure of individuals and populations cannot realistically be represented by selected concentrations at fixed outdoor locations, due to the fine-resolution spatial variability of concentrations in urban areas and the mobility of people (Kukkonen et al., 2016b; Singh et al., 2020b).

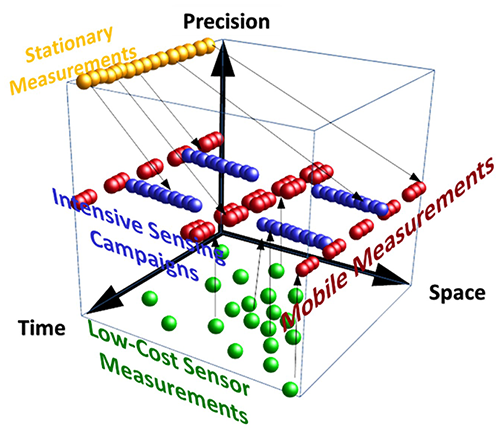

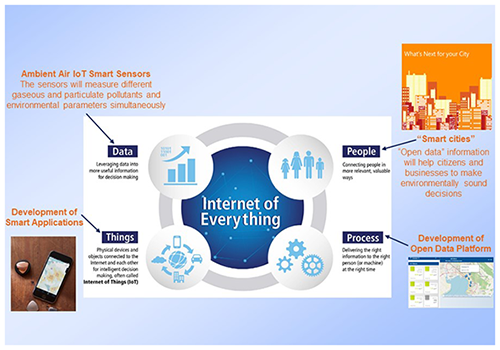

Further development of the installation of a larger number of cheap measurement devices, especially for PM 2.5 , that are operated by people interested in air quality in so-called citizen science projects is ongoing ( https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/assessing-air-quality-through-citizen-science , last access: 21 February 2022). Examples of such projects are the Open Knowledge Foundation Germany; OK Labs ( https://luftdaten.info/ , last access: 21 February 2022), Opensense (open air quality, meteorological, and noise data platform), connected with OK Labs ( https://opensensemap.org/ , last access: 21 February 2022); or AirSensEUR, an open framework for air quality monitoring ( https://airsenseur.org/website/airsenseur-air-quality-monitoring-open-framework/ , last access: 21 February 2022). However, the accuracy of these measurements is still debated (Duvall et al., 2021; Concas et al., 2021), although the development of more accurate but still low-cost devices is ongoing for denser measurement networks, 3D measurements, and new modelling. Measurements are not only required for compliance and for monitoring long-term trends. Observations are used more and more for evaluating models and where measurements might also be used to nudge the model results, for example through data assimilation (see for example Campbell et al., 2015; K. Wang et al., 2015).

1.5 Air quality modelling from local to regional scales

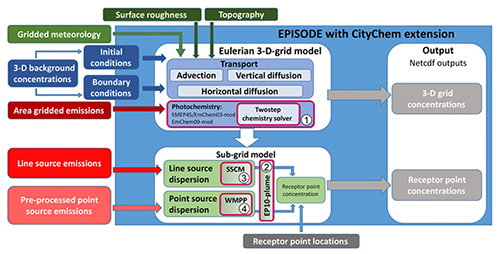

Air pollution models have played and continue to play a pivotal role in furthering scientific understanding and supporting policy. Additionally, for air quality assessments by regulatory methods, it is also important to predict or even forecast peak pollutant concentrations to prevent or reduce health impacts from acute episodes. Both complex and simple models have also been developed for dispersion on urban and local scales. A review has been provided by Thunis et al. (2016) that examines local- and regional-scale models, especially from an air quality policy perspective. Briefly, the spectrum of finer- and urban-scale air quality models applied for urban areas is very broad and includes urbanized chemistry–transport models (CTMs) coupled with high-resolution meso-scale numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) obstacle-resolved models in Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) and large-eddy simulation (LES) formulations (the latest mostly only for research studies), and statistical and land use regression (LUR) models. Developments in local-scale air quality models continue. For example, the dispersion on local or urban scales that also considers obstacle effects has recently been investigated using wind tunnels and CFD models (e.g. Badeke et al., 2021).

During the last decades many countries have established real-time air quality forecasting (AQF) programmes to forecast concentrations of pollutants of special health concerns. The history of AQF can be traced back to the 1960s, when the US Weather Bureau provided the first forecasts of air stagnation or pollution potential using numerical weather prediction (NWP) models to forecast conditions conducive to poor air quality (e.g. Niemeyer, 1960). Accurate AQF can offer tremendous societal and economic benefits by enabling advanced planning for individuals, organizations, and communities in order to avoid exposure and reduce adverse health impacts resulting from air pollution. Forecasts can also assist urban authorities, for example, in changing and managing traffic and hence reduce road emissions in a particular area. Air quality modelling, however, can provide a more holistic assessment of air pollution for policy makers and decision makers to develop strategies that do not compromise benefits in one area while worsening air pollution in another.

Two main approaches can be generally distinguished in AQF: empirical/statistical methods and chemical transport modelling. Until the mid-1990s, AQF was mainly performed using empirical approaches and statistical models trained with or fitted to historical air quality and meteorological data (e.g. Aron, 1980). The empirical/statistical approaches have several common drawbacks for AQF which are reviewed and discussed by Zhang et al. (2012a) and Baklanov and Zhang (2020).

The chemical transport models (CTMs) are more commonly used today for air quality assessment and forecasting. Over the last decade AQF systems based on CTMs have been developed rapidly and are currently in operation in many countries. Progress in CTM development and computing technologies has allowed daily AQFs using simplified or more comprehensive 3D CTMs, such as offline-coupled and online-coupled meteorology–chemistry models. There are several comprehensive review papers, e.g. Kukkonen et al. (2012), Zhang et al. (2012a, b), Baklanov et al. (2014), Bai et al. (2018), and Baklanov and Zhang (2020), which have more thoroughly examined the development and principles of 3D global and regional AQF models and identified areas of improvement in meteorological forecasts, chemical inputs, and model treatments of atmospheric physical, dynamic, and chemical processes.

Interest in regional pollution arose in the 1980s, initially spurred by the acid rain problem (Sokhi, 2012; Fowler et al., 2020). In the past few years, these regional air pollution models have become routinely linked with outputs of NWP models such as WRF and ECMWF. Models such as WRF coupled with CTMs are often run in a nested mode down to an inner domain with a grid size of 1 km. As computer speed and storage continually improve with developments in parameterization, in the future, these nested models may potentially take over most applied T&D analyses on local scales. Another development over the last decade is the increasing use of ensemble techniques which have also progressed and make it possible to cover an increasing range of pollutants and physical parameters, using a multiplicity of observations (e.g. ground, airborne, satellite) that enable the different dimensions of models to be investigated. At the same time that the use of regional Eulerian models has grown (e.g. Rao et al., 2020), the puff, particle, and plume T&D models for small scales and mesoscales have been improved. Several agencies and countries now have Lagrangian particle or puff models that are linked with an NWP model and are applied at all scales (Ngan et al., 2019).

1.6 Interactions of air quality, meteorology, and climate

Meteorological processes are the main driver for atmospheric pollutant dispersion, transformation, and removal. However, as studies have shown (e.g. Baklanov et al., 2016; Pfister et al., 2020), the chemistry dynamics feedbacks exist among the Earth system components, including the atmosphere. Potential impacts of aerosol feedbacks can be broadly explained in terms of four types of effects: direct, semidirect, first indirect, and second indirect (e.g. Kong et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2016). Such feedbacks, forcing mechanisms, and two-way interactions of atmospheric composition and meteorology can be important not only for air pollution modelling but also for NWP and climate change prediction (WMO, 2016).

There is a strong scientific need to increase interfacing or even coupling of prediction capabilities for weather, air quality, and climate. The first driver for improvement is the fact that information from predictions is needed at higher spatial resolutions (and longer lead times) to address societal needs. Secondly, there is the need to estimate the changes in air quality in the future driven by climate change. Thirdly, continued improvements in prediction skill require advances in observing systems, models, and assimilation systems. In addition, there is also growing awareness of the benefits of more closely integrating atmospheric composition, weather, and climate predictions, because of the important feedbacks resulting from the role that aerosols (and atmospheric composition in general) play in these systems. Recently, this trend for further integration has led to greater coupling of atmospheric dynamics and composition models to deliver seamless Earth system modelling (ESM) systems.

1.7 Air quality and health perspectives

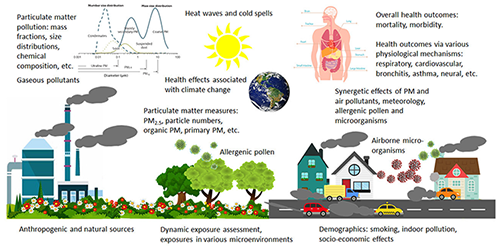

Air pollution has serious impacts on our health by reducing our life span and exacerbating numerous illnesses. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBDS, 2020) summarizes a comprehensive assessment of the impact of a large number of stressors including air pollution. One of the most hazardous air pollutants is particulate matter. Primary particles are directly released into the atmosphere and originate from natural and anthropogenic sources. Secondary particles are formed in the atmosphere by chemical reactions involving, in particular, gas-to-particle conversion. Primary particles tend to be larger than secondary particles. Ultra-fine and fine particles, on the other hand, deposit into the respiratory system; these may reach human lungs and blood circulation and may therefore cause severe adverse health effects (e.g. Maragkidou, 2018; Stone et al., 2017).

When considering numbers of particles, most of these in the atmosphere are smaller than 0.1 µm in diameter (e.g. Jesus et al., 2019). On the other hand, the majority of the particle volume and mass is found in particles larger than 0.1 µm (e.g. Filella, 2012). The particle number concentrations are therefore in most cases dominated by the ultra-fine aerosols, whereas the mass or volume concentrations are dominated by the coarse and accumulation mode aerosols (e.g. Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). Other characteristics of PM have also been shown to be important in relation to health impact. The characteristics of atmospheric particles in addition to the size include mass, surface area, chemical composition, and shape and morphology (Gwaze, 2007).

It has been convincingly shown in previous literature that the exposure to particulate matter (PM) in ambient air can be associated with negative health impacts (e.g. Hime et al., 2018; Thurston et al., 2017). It is also known that PM can cause health effects combined with other environmental stressors, such as heat waves and cold spells, allergenic pollen, or airborne microorganisms. For understanding such associations, reliable methods are needed to evaluate the exposure of human populations to air pollution.

The strong association between the exposure to mass-based concentrations of ambient PM air pollution and severe health effects has been found by numerous epidemiological studies (e.g. Pope et al., 2020). In particular, there is extensive scientific evidence to suggest that exposure to PM air pollution can have acute effects on human health, resulting in respiratory, cardiovascular and lung problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPDs), asthma, oxidative stress, immune response, and even lung cancer (e.g. Chen et al., 2017; Hime et al., 2018; Falcon-Rodriguez et al., 2016; Thurston et al., 2017). For instance, a cohort study conducted across Montreal and Toronto (Canada) on 1.9 million adults during four cycles (1991, 1996, 2001, and 2006) resulted in a possible connection between ambient ultra-fine particles and incident brain tumours in adults (Weichenthal et al., 2020). Recent work has also investigated assessment of the health impacts of particulate matter in terms of its oxidative potential (e.g. Gao et al., 2020; He et al., 2021).

1.8 Air quality management and legislative and policy responses

Air quality management and policy is an important but also complex task for political decision makers. It started in the middle of the last century when concerns about smoke and London smog arose. The national authorities at that time reacted by stipulating efficient dust filters and high stacks for large firings. In the 1980s, forest dieback led to a shift in focus to other important air pollutants, especially SO 2 , NO x , and later ozone, and so also on the ozone precursors including VOCs. In the 1990s studies showed a relation between PM 10 and “chronic” mortality, thus drawing particular attention to the health effects of fine particles (WHO, 2013b). Also, in the 1990s, the European Commission (EC) increasingly took over the responsibility for air pollution control from the authorities of the member states, on the basis that there is free trade of goods in the European Union and also transboundary air pollutants.

The EC launched the first Air Quality Framework Directive 96/62/EC and its daughter directives, which regulated the concentrations for a range of pollutants including ozone, PM 10 , NO 2 , and SO 2 . The first standard for vehicles (Euro 1) was established in 1991. The sulfur content in many oil products was reduced starting in the late 1990s. Some of the problems with air pollution in the EU, e.g. the acidification of lakes, were caused by the transport of air pollutants from eastern Europe to the EU. This problem was discussed in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), as all countries involved were members of this commission. The Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution within the UNECE agreed on eight protocols, which set aims for reducing emissions, starting in 1985 with reducing national SO 2 emissions, with the latest protocol being the revised Protocol to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground-level Ozone (Gothenburg Protocol), which limits national SO 2 , NO x , VOC, NH 3 , and PM 2.5 emissions.

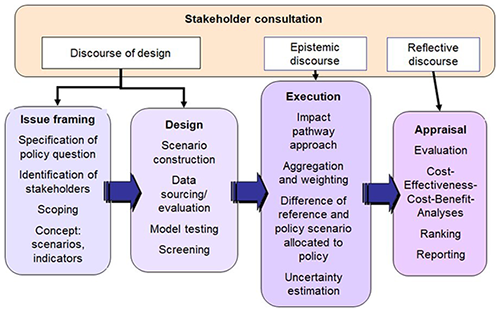

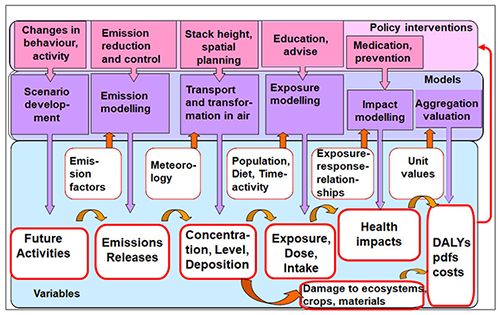

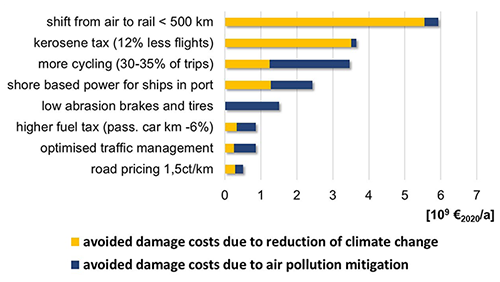

Over time, regulation of air pollution has become more stringent and thus more complex and more costly. To achieve acceptance, it had to be demonstrated that the measures would achieve the environmental and climate protection goals safely and efficiently, i.e. with the lowest possible costs and other disadvantages, and that the advantages of environmental protection outweigh the disadvantages (Friedrich, 2016). It is a scientific task to support this demonstration, mainly by developing and applying integrated assessments of air pollution control strategies, e.g. by carrying out cost–effectiveness and cost–benefit analyses. With a cost–effectiveness analysis (CEA) the net costs (costs minus monetizable benefits) for improving an indicator used in an environmental aim with a certain measure are calculated, e.g. the costs of reducing the emission of 1 t of CO 2,eq . The lower the unit costs, the higher the effectiveness of a policy or measure. The CEA is mostly used for assessing the effects associated with climatically active species, as the effects are global. The situation is different for air pollution, where the avoided damage of emitting 1 t of a pollutant varies widely depending on time and place of the emission.

The more general methodology is cost–benefit analysis (CBA). In a CBA, the benefits, i.e. the avoided damage and risks due to an air pollution control measure or bundle of measures, are quantified and monetized. Then, costs including the monetized negative impacts of the measures are estimated. If the net present value of benefits minus costs is positive, benefits outweigh the costs. Thus the measure is beneficial for society; i.e. it increases welfare. Dividing the benefits minus the nonmonetary costs by the monetary costs will result in the net benefit per euro spent, which can be used for ranking policies and measures.

Of course, for performing mathematical operations like summing or dividing costs and benefits, they have first to be quantified and then converted into a common unit, for which a monetary unit, i.e. euros, is usually chosen.

The term “integrated” in the context of integrated assessment means that – as far as possible – all relevant aspects (disadvantages, benefits) should be considered, i.e. all aspects that might have a non-negligible influence on the result of the assessment. Given the high complexity of answering questions related to managing the impacts of air quality, a scientific approach is required to conduct an integrated assessment, which is defined here as “a multidisciplinary process of synthesizing knowledge across scientific disciplines with the purpose of providing all relevant information to decision makers to help to make decisions” (Friedrich, 2016).

The focus of this review is on research developments that have emerged over approximately the past decade. Where needed, older references are given, but these either provide a historical perspective or support emerging work or where no recent references were available. The following areas of air quality research have been examined in this review:

air pollution sources and emissions;

air quality observations and instrumentation;

air quality modelling from local to regional scales;

interactions between air quality, meteorology, and climate;

air quality exposure and health;

air quality management and policy development.

Each section begins with a brief overview and then examines the current status and challenges before proceeding to highlight emerging challenges and priorities in air quality research. In terms of climate research, the focus is more on the interactions between air quality and meteorology with climate and not on climate change per se.

The section on air quality observations focuses on new technological developments that have led to remote sensing, low-cost sensors, crowdsourcing, and modern methods of data mining rather than attempting to cover the more traditional instrumentations and measurements which are dealt with, e.g. in Foken (2021). After considering these themes of research, the Discussion section pulls together common strands on science and implications for policy makers.

3.1 Brief overview

A fundamental prerequisite of successful abatement strategies for reduction of air pollution is understanding the role of emission sources in ambient concentration levels of different air pollutants. This requires a good knowledge of air pollution sources regarding their strength, chemical characterization, spatial distribution, and temporal variation along with knowledge on their atmospheric transport and processing. In observations of ambient air pollution, typically a complex mixture of contributions from different pollution sources is observed. These source contributions have to be disentangled before efficient reduction strategies targeting specific sources can be set up. Consequently, our discussion below is divided into two main topics: (i) emission inventories and emission pre-processing for model applications and (ii) source apportionment methods and studies.

This paper cannot give a full overview of the status of and the emerging challenges in all emissions sectors. For example, we do not deal with aviation as the impact on air quality in cities is generally rather small or concentrated around the major airports, or with construction machinery or industrial sources which make significant contributions to air pollution in some areas. Instead, we put emphasis on two emission sectors that have experienced important methodology developments in recent years in terms of emission inventories and that are of major concern for health effects: exhaust emissions from road traffic and shipping. We also touch other anthropogenic emissions, e.g. from agriculture and wood burning, As later in this paper we will explain, since individual exposure including the exposure to indoor pollution should gain importance in assessing air pollution, emissions from indoor sources will be addressed in a subchapter. Natural and biogenic emissions encompass VOC emissions from vegetation, NO emissions from soil, primary biological aerosol particles, windblown dust, methane from wetlands and geological seepages, and various pollutants from forest fires and volcanoes; these are described in a series of papers edited by Friedrich (2009). As natural and biogenic emissions depend on meteorological data, which are input data for the atmospheric model, they are usually estimated in a submodule of the atmospheric model. They are not further discussed here.

3.2 Current status and challenges

3.2.1 emissions inventories.

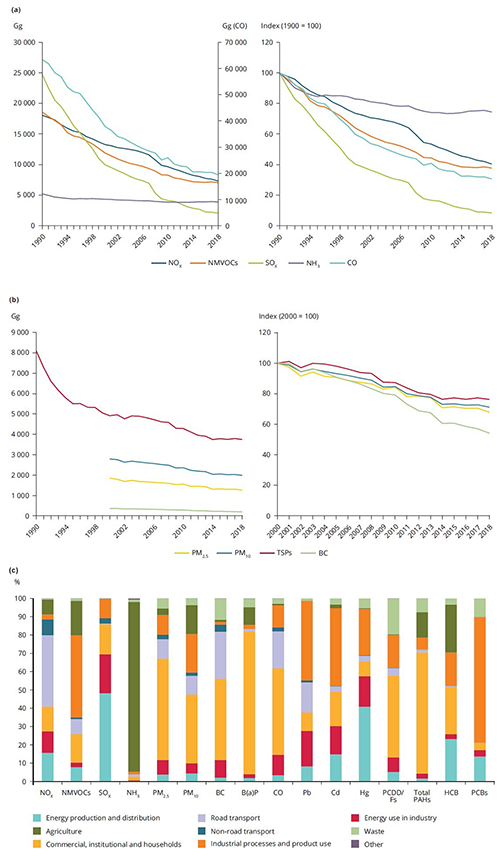

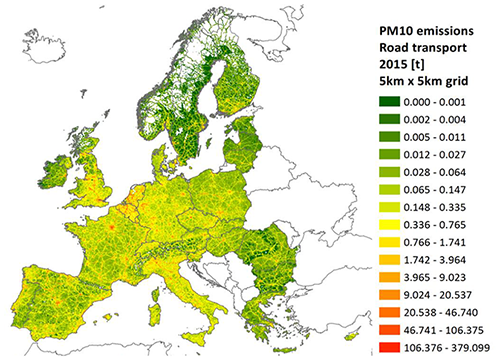

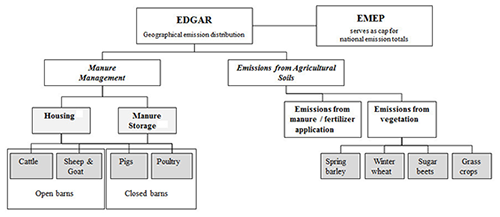

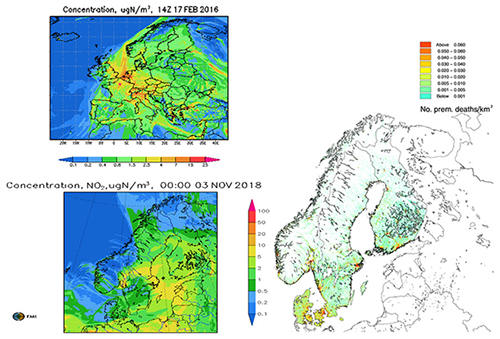

In the European Union, emissions of the most important gaseous air pollutants have decreased during the last 30 years (see Fig. 2). SO 2 and CO show reductions of at least 60 % (CO) or almost 90 % (SO 2 ). Also, NO x and non-methane volatile organic compound (NMVOC) emissions decreased by approx. 50 % while NH 3 shows much lower reductions of 20 % only. Similar to NH 3 , PM emissions also stay at similar levels compared to 2000 (Fig. 2b). Only black carbon shows considerably larger reductions, because of larger efforts to reduce BC, in particular from traffic. While traffic is the most important sector for NO x emissions and an important source for BC, PM emissions stem mainly from numerous small emission units like households and commercial applications (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2 EU-28 emission trends in absolute and relative numbers for (a) the main gaseous air pollutants and (b) particulate matter. Panel (c) shows the share of EU emissions of the main pollutants by sector in 2018 (EEA, 2020b).

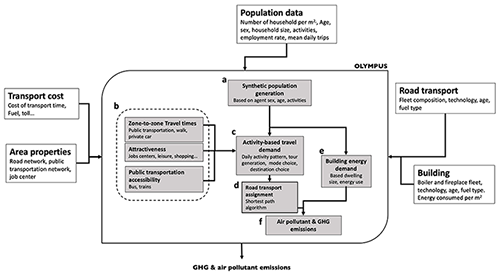

In parallel, research came on the path of accompanying and evaluating local emission control measures in a more comprehensive and systemic approach to urban space. The main technical advances of this research field have consisted in producing a more reliable assessment of the predominant emissions on the scale of an agglomeration/region. This has been done in order to feed the models with activity-based emission data such as population energy-consuming practices or local characteristics of road traffic, with the concern to better include their temporal variability or weather condition dependency. The originality of these approaches has been to develop the emissions inventories and modelling efforts in collaboration with stakeholders, for better data reliability and greater realism in policy support.

Improved and innovative representation of emissions, such as real configuration of residential combustion emission sources (location of domestic households using biomass combustion and surveys regarding the characteristics and use of wood stoves, boilers, and other relevant appliances) allows more realistic diagnoses (e.g. Ots et al., 2018; Grythe et al., 2019; Savolahti et al., 2019; Plejdrup et al., 2016; Kukkonen et al., 2020b). Also, increased use of traffic flow models for the representation of mobile emissions have provided refined traffic and emission estimates in cities and on national levels, as a path for improved scenarios (e.g. Matthias et al., 2020a). Kukkonen et al. (2016a) presented an emission inventory for particulate matter numbers (PNs) in the whole of Europe, and in more detail in five target cities. The accuracy of the modelled PN concentrations (PNCs) was evaluated against experimental data on regional and urban scales. They concluded that it is feasible to model PNCs in major cities within a reasonable accuracy, although major challenges remained in the evaluation of both the emissions and atmospheric transformation of PNCs.