- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Present Your Data Like a Pro

- Joel Schwartzberg

Demystify the numbers. Your audience will thank you.

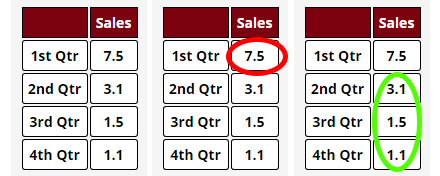

While a good presentation has data, data alone doesn’t guarantee a good presentation. It’s all about how that data is presented. The quickest way to confuse your audience is by sharing too many details at once. The only data points you should share are those that significantly support your point — and ideally, one point per chart. To avoid the debacle of sheepishly translating hard-to-see numbers and labels, rehearse your presentation with colleagues sitting as far away as the actual audience would. While you’ve been working with the same chart for weeks or months, your audience will be exposed to it for mere seconds. Give them the best chance of comprehending your data by using simple, clear, and complete language to identify X and Y axes, pie pieces, bars, and other diagrammatic elements. Try to avoid abbreviations that aren’t obvious, and don’t assume labeled components on one slide will be remembered on subsequent slides. Every valuable chart or pie graph has an “Aha!” zone — a number or range of data that reveals something crucial to your point. Make sure you visually highlight the “Aha!” zone, reinforcing the moment by explaining it to your audience.

With so many ways to spin and distort information these days, a presentation needs to do more than simply share great ideas — it needs to support those ideas with credible data. That’s true whether you’re an executive pitching new business clients, a vendor selling her services, or a CEO making a case for change.

- JS Joel Schwartzberg oversees executive communications for a major national nonprofit, is a professional presentation coach, and is the author of Get to the Point! Sharpen Your Message and Make Your Words Matter and The Language of Leadership: How to Engage and Inspire Your Team . You can find him on LinkedIn and X. TheJoelTruth

Partner Center

Call Us Today! +91 99907 48956 | [email protected]

It is the simplest form of data Presentation often used in schools or universities to provide a clearer picture to students, who are better able to capture the concepts effectively through a pictorial Presentation of simple data.

2. Column chart

It is a simplified version of the pictorial Presentation which involves the management of a larger amount of data being shared during the presentations and providing suitable clarity to the insights of the data.

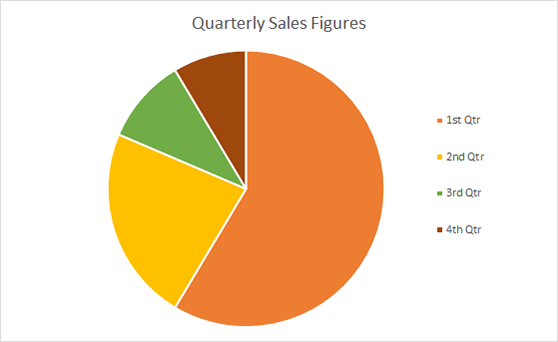

3. Pie Charts

Pie charts provide a very descriptive & a 2D depiction of the data pertaining to comparisons or resemblance of data in two separate fields.

4. Bar charts

A bar chart that shows the accumulation of data with cuboid bars with different dimensions & lengths which are directly proportionate to the values they represent. The bars can be placed either vertically or horizontally depending on the data being represented.

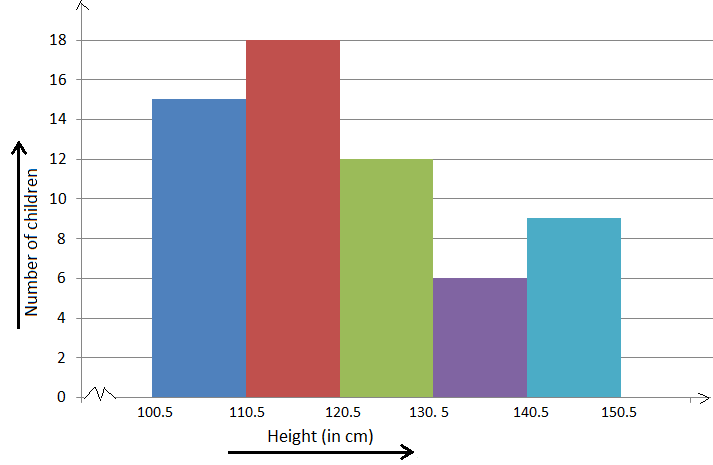

5. Histograms

It is a perfect Presentation of the spread of numerical data. The main differentiation that separates data graphs and histograms are the gaps in the data graphs.

6. Box plots

Box plot or Box-plot is a way of representing groups of numerical data through quartiles. Data Presentation is easier with this style of graph dealing with the extraction of data to the minutes of difference.

Map Data graphs help you with data Presentation over an area to display the areas of concern. Map graphs are useful to make an exact depiction of data over a vast case scenario.

All these visual presentations share a common goal of creating meaningful insights and a platform to understand and manage the data in relation to the growth and expansion of one’s in-depth understanding of data & details to plan or execute future decisions or actions.

Importance of Data Presentation

Data Presentation could be both can be a deal maker or deal breaker based on the delivery of the content in the context of visual depiction.

Data Presentation tools are powerful communication tools that can simplify the data by making it easily understandable & readable at the same time while attracting & keeping the interest of its readers and effectively showcase large amounts of complex data in a simplified manner.

If the user can create an insightful presentation of the data in hand with the same sets of facts and figures, then the results promise to be impressive.

There have been situations where the user has had a great amount of data and vision for expansion but the presentation drowned his/her vision.

To impress the higher management and top brass of a firm, effective presentation of data is needed.

Data Presentation helps the clients or the audience to not spend time grasping the concept and the future alternatives of the business and to convince them to invest in the company & turn it profitable both for the investors & the company.

Although data presentation has a lot to offer, the following are some of the major reason behind the essence of an effective presentation:-

- Many consumers or higher authorities are interested in the interpretation of data, not the raw data itself. Therefore, after the analysis of the data, users should represent the data with a visual aspect for better understanding and knowledge.

- The user should not overwhelm the audience with a number of slides of the presentation and inject an ample amount of texts as pictures that will speak for themselves.

- Data presentation often happens in a nutshell with each department showcasing their achievements towards company growth through a graph or a histogram.

- Providing a brief description would help the user to attain attention in a small amount of time while informing the audience about the context of the presentation

- The inclusion of pictures, charts, graphs and tables in the presentation help for better understanding the potential outcomes.

- An effective presentation would allow the organization to determine the difference with the fellow organization and acknowledge its flaws. Comparison of data would assist them in decision making.

Recommended Courses

Data Visualization

Using powerbi &tableau.

Tableau for Data Analysis

MySQL Certification Program

The PowerBI Masterclass

Need help call our support team 7:00 am to 10:00 pm (ist) at (+91 999-074-8956 | 9650-308-956), keep in touch, email: [email protected].

WhatsApp us

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Presentation of Data

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 577

Learning Objectives

- To learn two ways that data will be presented in the text.

In this book we will use two formats for presenting data sets. The first is a data list, which is an explicit listing of all the individual measurements, either as a display with space between the individual measurements, or in set notation with individual measurements separated by commas.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The data obtained by measuring the age of \(21\) randomly selected students enrolled in freshman courses at a university could be presented as the data list:

\[\begin{array}{cccccccccc}18 & 18 & 19 & 19 & 19 & 18 & 22 & 20 & 18 & 18 & 17 \\ 19 & 18 & 24 & 18 & 20 & 18 & 21 & 20 & 17 & 19 &\end{array} \nonumber \]

or in set notation as:

\[ \{18,18,19,19,19,18,22,20,18,18,17,19,18,24,18,20,18,21,20,17,19\} \nonumber \]

A data set can also be presented by means of a data frequency table, a table in which each distinct value \(x\) is listed in the first row and its frequency \(f\), which is the number of times the value \(x\) appears in the data set, is listed below it in the second row.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The data set of the previous example is represented by the data frequency table

\[\begin{array}{c|cccccc}x & 17 & 18 & 19 & 20 & 21 & 22 & 24 \\ \hline f & 2 & 8 & 5 & 3 & 1 & 1 & 1\end{array} \nonumber \]

The data frequency table is especially convenient when data sets are large and the number of distinct values is not too large.

Key Takeaway

- Data sets can be presented either by listing all the elements or by giving a table of values and frequencies.

Basic Statistics in Criminology and Criminal Justice pp 39–71 Cite as

Representing and Displaying Data

- David Weisburd 5 , 6 ,

- Chester Britt 7 ,

- David B. Wilson 5 &

- Alese Wooditch 8

- First Online: 24 February 2021

1751 Accesses

The graphical display of data is an important tool for presenting statistical results in such a way that the key features or characteristics of an analysis are highlighted. There are many different ways the same data might be displayed. In this chapter, we introduce some common ways of representing data in graphical form, along with suggestions for effectively presenting information in an accurate way. We begin by discussing the most basic way of summarizing—and then graphing—data: frequency distributions, bar charts, and histograms. Bar charts can be used to represent the frequencies, percentages, or proportions of nominal or ordinal variables. Bar charts may also represent the data separately by a grouping variable. Histograms can be used to represent the frequencies, percentages, or proportions of continuous or discrete data (interval or ratio scales). Boxplots graph a frequency distribution by creating a box that represents the middle 50% of the distribution. Finally, time series data may be graphically displayed in a time series plot, a line graph that portrays the values of a variable over some period of time, such as days, weeks, months, or years.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Most statistical software and spreadsheet packages allow for manipulation of many characteristics of a bar chart, including color, shading, patterning, and dimensions (two versus three). While this allows for the construction of unique charts, you should be wary of adding so much detail to a chart that the reader loses the point you are trying to make.

For a good discussion of the benefits and drawbacks of various approaches, see Henry ( 1995 ).

Capital Punishment in the United States , ICPSR Study #6956, available through the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data (NACJD) at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/

The entire GSS database is publicly available and can be accessed at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/00028 .

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States, available at https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s

Throughout the text, we will make use of user-written procedures for Stata. The process will be very much the same every time we execute commands needed to make a procedure available within Stata. If you are working on a computer in a student computer lab setting, you will need to install these kinds of procedures every time you move to a different machine and run Stata.

Henry, G. T. (1995). Graphing data: Techniques for display and analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory Data Analysis . Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Criminology, Law and Society, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA

David Weisburd & David B. Wilson

Institute of Criminology, Faculty of Law, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

David Weisburd

Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA

Chester Britt

Department of Criminal Justice, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Alese Wooditch

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Electronic supplementary material

Datasets_and_syntax_esm (zip 22.1kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Weisburd, D., Britt, C., Wilson, D.B., Wooditch, A. (2020). Representing and Displaying Data. In: Basic Statistics in Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47967-1_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47967-1_3

Published : 24 February 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-47966-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-47967-1

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Data presentation: A comprehensive guide

Learn how to create data presentation effectively and communicate your insights in a way that is clear, concise, and engaging.

Raja Bothra

Building presentations

Hey there, fellow data enthusiast!

Welcome to our comprehensive guide on data presentation.

Whether you're an experienced presenter or just starting, this guide will help you present your data like a pro.

We'll dive deep into what data presentation is, why it's crucial, and how to master it. So, let's embark on this data-driven journey together.

What is data presentation?

Data presentation is the art of transforming raw data into a visual format that's easy to understand and interpret. It's like turning numbers and statistics into a captivating story that your audience can quickly grasp. When done right, data presentation can be a game-changer, enabling you to convey complex information effectively.

Why are data presentations important?

Imagine drowning in a sea of numbers and figures. That's how your audience might feel without proper data presentation. Here's why it's essential:

- Clarity : Data presentations make complex information clear and concise.

- Engagement : Visuals, such as charts and graphs, grab your audience's attention.

- Comprehension : Visual data is easier to understand than long, numerical reports.

- Decision-making : Well-presented data aids informed decision-making.

- Impact : It leaves a lasting impression on your audience.

Types of data presentation

Now, let's delve into the diverse array of data presentation methods, each with its own unique strengths and applications. We have three primary types of data presentation, and within these categories, numerous specific visualization techniques can be employed to effectively convey your data.

1. Textual presentation

Textual presentation harnesses the power of words and sentences to elucidate and contextualize your data. This method is commonly used to provide a narrative framework for the data, offering explanations, insights, and the broader implications of your findings. It serves as a foundation for a deeper understanding of the data's significance.

2. Tabular presentation

Tabular presentation employs tables to arrange and structure your data systematically. These tables are invaluable for comparing various data groups or illustrating how data evolves over time. They present information in a neat and organized format, facilitating straightforward comparisons and reference points.

3. Graphical presentation

Graphical presentation harnesses the visual impact of charts and graphs to breathe life into your data. Charts and graphs are powerful tools for spotlighting trends, patterns, and relationships hidden within the data. Let's explore some common graphical presentation methods:

- Bar charts: They are ideal for comparing different categories of data. In this method, each category is represented by a distinct bar, and the height of the bar corresponds to the value it represents. Bar charts provide a clear and intuitive way to discern differences between categories.

- Pie charts: It excel at illustrating the relative proportions of different data categories. Each category is depicted as a slice of the pie, with the size of each slice corresponding to the percentage of the total value it represents. Pie charts are particularly effective for showcasing the distribution of data.

- Line graphs: They are the go-to choice when showcasing how data evolves over time. Each point on the line represents a specific value at a particular time period. This method enables viewers to track trends and fluctuations effortlessly, making it perfect for visualizing data with temporal dimensions.

- Scatter plots: They are the tool of choice when exploring the relationship between two variables. In this method, each point on the plot represents a pair of values for the two variables in question. Scatter plots help identify correlations, outliers, and patterns within data pairs.

The selection of the most suitable data presentation method hinges on the specific dataset and the presentation's objectives. For instance, when comparing sales figures of different products, a bar chart shines in its simplicity and clarity. On the other hand, if your aim is to display how a product's sales have changed over time, a line graph provides the ideal visual narrative.

Additionally, it's crucial to factor in your audience's level of familiarity with data presentations. For a technical audience, more intricate visualization methods may be appropriate. However, when presenting to a general audience, opting for straightforward and easily understandable visuals is often the wisest choice.

In the world of data presentation, choosing the right method is akin to selecting the perfect brush for a masterpiece. Each tool has its place, and understanding when and how to use them is key to crafting compelling and insightful presentations. So, consider your data carefully, align your purpose, and paint a vivid picture that resonates with your audience.

What to include in data presentation

When creating your data presentation, remember these key components:

- Data points : Clearly state the data points you're presenting.

- Comparison : Highlight comparisons and trends in your data.

- Graphical methods : Choose the right chart or graph for your data.

- Infographics : Use visuals like infographics to make information more digestible.

- Numerical values : Include numerical values to support your visuals.

- Qualitative information : Explain the significance of the data.

- Source citation : Always cite your data sources.

How to structure an effective data presentation

Creating a well-structured data presentation is not just important; it's the backbone of a successful presentation. Here's a step-by-step guide to help you craft a compelling and organized presentation that captivates your audience:

1. Know your audience

Understanding your audience is paramount. Consider their needs, interests, and existing knowledge about your topic. Tailor your presentation to their level of understanding, ensuring that it resonates with them on a personal level. Relevance is the key.

2. Have a clear message

Every effective data presentation should convey a clear and concise message. Determine what you want your audience to learn or take away from your presentation, and make sure your message is the guiding light throughout your presentation. Ensure that all your data points align with and support this central message.

3. Tell a compelling story

Human beings are naturally wired to remember stories. Incorporate storytelling techniques into your presentation to make your data more relatable and memorable. Your data can be the backbone of a captivating narrative, whether it's about a trend, a problem, or a solution. Take your audience on a journey through your data.

4. Leverage visuals

Visuals are a powerful tool in data presentation. They make complex information accessible and engaging. Utilize charts, graphs, and images to illustrate your points and enhance the visual appeal of your presentation. Visuals should not just be an accessory; they should be an integral part of your storytelling.

5. Be clear and concise

Avoid jargon or technical language that your audience may not comprehend. Use plain language and explain your data points clearly. Remember, clarity is king. Each piece of information should be easy for your audience to digest.

6. Practice your delivery

Practice makes perfect. Rehearse your presentation multiple times before the actual delivery. This will help you deliver it smoothly and confidently, reducing the chances of stumbling over your words or losing track of your message.

A basic structure for an effective data presentation

Armed with a comprehensive comprehension of how to construct a compelling data presentation, you can now utilize this fundamental template for guidance:

In the introduction, initiate your presentation by introducing both yourself and the topic at hand. Clearly articulate your main message or the fundamental concept you intend to communicate.

Moving on to the body of your presentation, organize your data in a coherent and easily understandable sequence. Employ visuals generously to elucidate your points and weave a narrative that enhances the overall story. Ensure that the arrangement of your data aligns with and reinforces your central message.

As you approach the conclusion, succinctly recapitulate your key points and emphasize your core message once more. Conclude by leaving your audience with a distinct and memorable takeaway, ensuring that your presentation has a lasting impact.

Additional tips for enhancing your data presentation

To take your data presentation to the next level, consider these additional tips:

- Consistent design : Maintain a uniform design throughout your presentation. This not only enhances visual appeal but also aids in seamless comprehension.

- High-quality visuals : Ensure that your visuals are of high quality, easy to read, and directly relevant to your topic.

- Concise text : Avoid overwhelming your slides with excessive text. Focus on the most critical points, using visuals to support and elaborate.

- Anticipate questions : Think ahead about the questions your audience might pose. Be prepared with well-thought-out answers to foster productive discussions.

By following these guidelines, you can structure an effective data presentation that not only informs but also engages and inspires your audience. Remember, a well-structured presentation is the bridge that connects your data to your audience's understanding and appreciation.

Do’s and don'ts on a data presentation

- Use visuals : Incorporate charts and graphs to enhance understanding.

- Keep it simple : Avoid clutter and complexity.

- Highlight key points : Emphasize crucial data.

- Engage the audience : Encourage questions and discussions.

- Practice : Rehearse your presentation.

Don'ts:

- Overload with data : Less is often more; don't overwhelm your audience.

- Fit Unrelated data : Stay on topic; don't include irrelevant information.

- Neglect the audience : Ensure your presentation suits your audience's level of expertise.

- Read word-for-word : Avoid reading directly from slides.

- Lose focus : Stick to your presentation's purpose.

Summarizing key takeaways

- Definition : Data presentation is the art of visualizing complex data for better understanding.

- Importance : Data presentations enhance clarity, engage the audience, aid decision-making, and leave a lasting impact.

- Types : Textual, Tabular, and Graphical presentations offer various ways to present data.

- Choosing methods : Select the right method based on data, audience, and purpose.

- Components : Include data points, comparisons, visuals, infographics, numerical values, and source citations.

- Structure : Know your audience, have a clear message, tell a compelling story, use visuals, be concise, and practice.

- Do's and don'ts : Do use visuals, keep it simple, highlight key points, engage the audience, and practice. Don't overload with data, include unrelated information, neglect the audience's expertise, read word-for-word, or lose focus.

1. What is data presentation, and why is it important in 2023?

Data presentation is the process of visually representing data sets to convey information effectively to an audience. In an era where the amount of data generated is vast, visually presenting data using methods such as diagrams, graphs, and charts has become crucial. By simplifying complex data sets, presentation of the data may helps your audience quickly grasp much information without drowning in a sea of chart's, analytics, facts and figures.

2. What are some common methods of data presentation?

There are various methods of data presentation, including graphs and charts, histograms, and cumulative frequency polygons. Each method has its strengths and is often used depending on the type of data you're using and the message you want to convey. For instance, if you want to show data over time, try using a line graph. If you're presenting geographical data, consider to use a heat map.

3. How can I ensure that my data presentation is clear and readable?

To ensure that your data presentation is clear and readable, pay attention to the design and labeling of your charts. Don't forget to label the axes appropriately, as they are critical for understanding the values they represent. Don't fit all the information in one slide or in a single paragraph. Presentation software like Prezent and PowerPoint can help you simplify your vertical axis, charts and tables, making them much easier to understand.

4. What are some common mistakes presenters make when presenting data?

One common mistake is trying to fit too much data into a single chart, which can distort the information and confuse the audience. Another mistake is not considering the needs of the audience. Remember that your audience won't have the same level of familiarity with the data as you do, so it's essential to present the data effectively and respond to questions during a Q&A session.

5. How can I use data visualization to present important data effectively on platforms like LinkedIn?

When presenting data on platforms like LinkedIn, consider using eye-catching visuals like bar graphs or charts. Use concise captions and e.g., examples to highlight the single most important information in your data report. Visuals, such as graphs and tables, can help you stand out in the sea of textual content, making your data presentation more engaging and shareable among your LinkedIn connections.

Create your data presentation with prezent

Prezent can be a valuable tool for creating data presentations. Here's how Prezent can help you in this regard:

- Time savings : Prezent saves up to 70% of presentation creation time, allowing you to focus on data analysis and insights.

- On-brand consistency : Ensure 100% brand alignment with Prezent's brand-approved designs for professional-looking data presentations.

- Effortless collaboration : Real-time sharing and collaboration features make it easy for teams to work together on data presentations.

- Data storytelling : Choose from 50+ storylines to effectively communicate data insights and engage your audience.

- Personalization : Create tailored data presentations that resonate with your audience's preferences, enhancing the impact of your data.

In summary, Prezent streamlines the process of creating data presentations by offering time-saving features, ensuring brand consistency, promoting collaboration, and providing tools for effective data storytelling. Whether you need to present data to clients, stakeholders, or within your organization, Prezent can significantly enhance your presentation-making process.

So, go ahead, present your data with confidence, and watch your audience be wowed by your expertise.

Thank you for joining us on this data-driven journey. Stay tuned for more insights, and remember, data presentation is your ticket to making numbers come alive!

Sign up for our free trial or book a demo !

Get the latest from Prezent community

Join thousands of subscribers who receive our best practices on communication, storytelling, presentation design, and more. New tips weekly. (No spam, we promise!)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Presentation of Data

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 19012

Skills to Develop

- To learn two ways that data will be presented in the text.

In this book we will use two formats for presenting data sets. The first is a data list, which is an explicit listing of all the individual measurements, either as a display with space between the individual measurements, or in set notation with individual measurements separated by commas.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The data obtained by measuring the age of \(21\) randomly selected students enrolled in freshman courses at a university could be presented as the data list:

\[\begin{array}{cccccccccc}18 & 18 & 19 & 19 & 19 & 18 & 22 & 20 & 18 & 18 & 17 \\ 19 & 18 & 24 & 18 & 20 & 18 & 21 & 20 & 17 & 19 &\end{array}\]

or in set notation as:

\[ \{18,18,19,19,19,18,22,20,18,18,17,19,18,24,18,20,18,21,20,17,19\} \]

A data set can also be presented by means of a data frequency table, a table in which each distinct value \(x\) is listed in the first row and its frequency \(f\), which is the number of times the value \(x\) appears in the data set, is listed below it in the second row.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The data set of the previous example is represented by the data frequency table

\[\begin{array}{c|cccccc}x & 17 & 18 & 19 & 20 & 21 & 22 & 24 \\ \hline f & 2 & 8 & 5 & 3 & 1 & 1 & 1\end{array}\]

The data frequency table is especially convenient when data sets are large and the number of distinct values is not too large.

Key Takeaway

- Data sets can be presented either by listing all the elements or by giving a table of values and frequencies.

Contributor

- Template:ContribShaferZhang

Home Blog Design Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

In this age of overwhelming information, the skill to effectively convey data has become extremely valuable. Initiating a discussion on data presentation types involves thoughtful consideration of the nature of your data and the message you aim to convey. Different types of visualizations serve distinct purposes. Whether you’re dealing with how to develop a report or simply trying to communicate complex information, how you present data influences how well your audience understands and engages with it. This extensive guide leads you through the different ways of data presentation.

Table of Contents

What is a Data Presentation?

What should a data presentation include, line graphs, treemap chart, scatter plot, how to choose a data presentation type, recommended data presentation templates, common mistakes done in data presentation.

A data presentation is a slide deck that aims to disclose quantitative information to an audience through the use of visual formats and narrative techniques derived from data analysis, making complex data understandable and actionable. This process requires a series of tools, such as charts, graphs, tables, infographics, dashboards, and so on, supported by concise textual explanations to improve understanding and boost retention rate.

Data presentations require us to cull data in a format that allows the presenter to highlight trends, patterns, and insights so that the audience can act upon the shared information. In a few words, the goal of data presentations is to enable viewers to grasp complicated concepts or trends quickly, facilitating informed decision-making or deeper analysis.

Data presentations go beyond the mere usage of graphical elements. Seasoned presenters encompass visuals with the art of storytelling with data, so the speech skillfully connects the points through a narrative that resonates with the audience. Depending on the purpose – inspire, persuade, inform, support decision-making processes, etc. – is the data presentation format that is better suited to help us in this journey.

To nail your upcoming data presentation, ensure to count with the following elements:

- Clear Objectives: Understand the intent of your presentation before selecting the graphical layout and metaphors to make content easier to grasp.

- Engaging introduction: Use a powerful hook from the get-go. For instance, you can ask a big question or present a problem that your data will answer. Take a look at our guide on how to start a presentation for tips & insights.

- Structured Narrative: Your data presentation must tell a coherent story. This means a beginning where you present the context, a middle section in which you present the data, and an ending that uses a call-to-action. Check our guide on presentation structure for further information.

- Visual Elements: These are the charts, graphs, and other elements of visual communication we ought to use to present data. This article will cover one by one the different types of data representation methods we can use, and provide further guidance on choosing between them.

- Insights and Analysis: This is not just showcasing a graph and letting people get an idea about it. A proper data presentation includes the interpretation of that data, the reason why it’s included, and why it matters to your research.

- Conclusion & CTA: Ending your presentation with a call to action is necessary. Whether you intend to wow your audience into acquiring your services, inspire them to change the world, or whatever the purpose of your presentation, there must be a stage in which you convey all that you shared and show the path to staying in touch. Plan ahead whether you want to use a thank-you slide, a video presentation, or which method is apt and tailored to the kind of presentation you deliver.

- Q&A Session: After your speech is concluded, allocate 3-5 minutes for the audience to raise any questions about the information you disclosed. This is an extra chance to establish your authority on the topic. Check our guide on questions and answer sessions in presentations here.

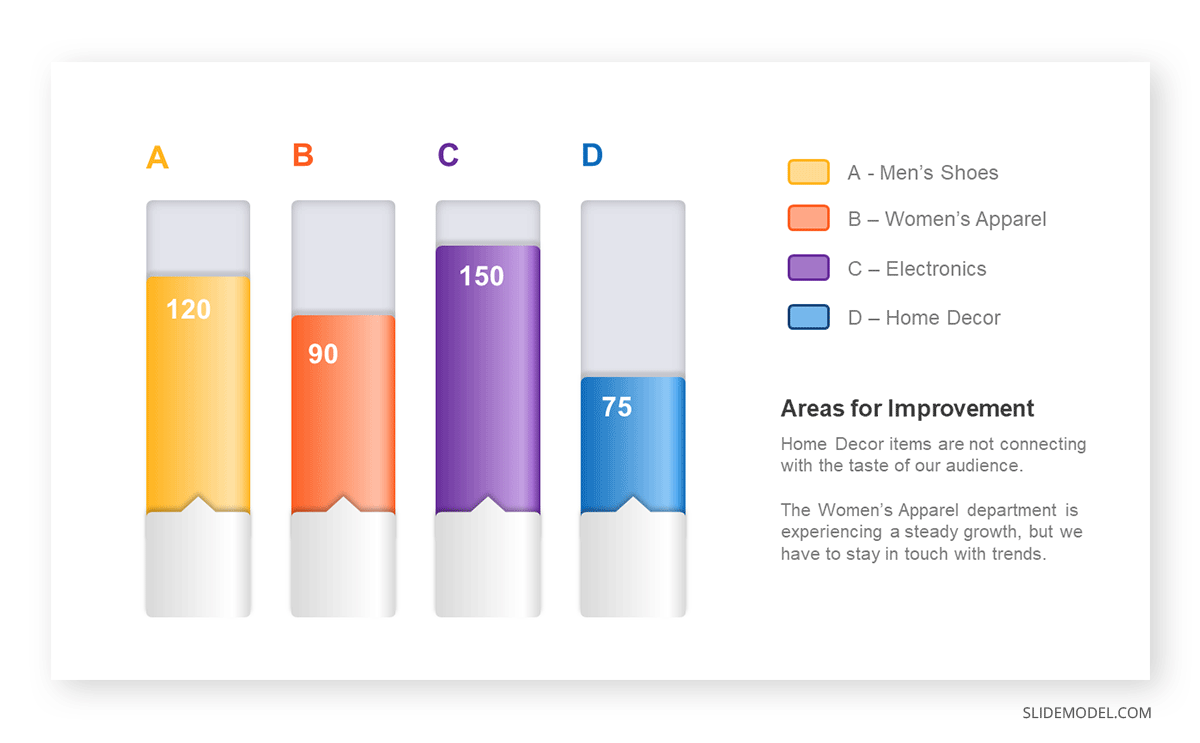

Bar charts are a graphical representation of data using rectangular bars to show quantities or frequencies in an established category. They make it easy for readers to spot patterns or trends. Bar charts can be horizontal or vertical, although the vertical format is commonly known as a column chart. They display categorical, discrete, or continuous variables grouped in class intervals [1] . They include an axis and a set of labeled bars horizontally or vertically. These bars represent the frequencies of variable values or the values themselves. Numbers on the y-axis of a vertical bar chart or the x-axis of a horizontal bar chart are called the scale.

Real-Life Application of Bar Charts

Let’s say a sales manager is presenting sales to their audience. Using a bar chart, he follows these steps.

Step 1: Selecting Data

The first step is to identify the specific data you will present to your audience.

The sales manager has highlighted these products for the presentation.

- Product A: Men’s Shoes

- Product B: Women’s Apparel

- Product C: Electronics

- Product D: Home Decor

Step 2: Choosing Orientation

Opt for a vertical layout for simplicity. Vertical bar charts help compare different categories in case there are not too many categories [1] . They can also help show different trends. A vertical bar chart is used where each bar represents one of the four chosen products. After plotting the data, it is seen that the height of each bar directly represents the sales performance of the respective product.

It is visible that the tallest bar (Electronics – Product C) is showing the highest sales. However, the shorter bars (Women’s Apparel – Product B and Home Decor – Product D) need attention. It indicates areas that require further analysis or strategies for improvement.

Step 3: Colorful Insights

Different colors are used to differentiate each product. It is essential to show a color-coded chart where the audience can distinguish between products.

- Men’s Shoes (Product A): Yellow

- Women’s Apparel (Product B): Orange

- Electronics (Product C): Violet

- Home Decor (Product D): Blue

Bar charts are straightforward and easily understandable for presenting data. They are versatile when comparing products or any categorical data [2] . Bar charts adapt seamlessly to retail scenarios. Despite that, bar charts have a few shortcomings. They cannot illustrate data trends over time. Besides, overloading the chart with numerous products can lead to visual clutter, diminishing its effectiveness.

For more information, check our collection of bar chart templates for PowerPoint .

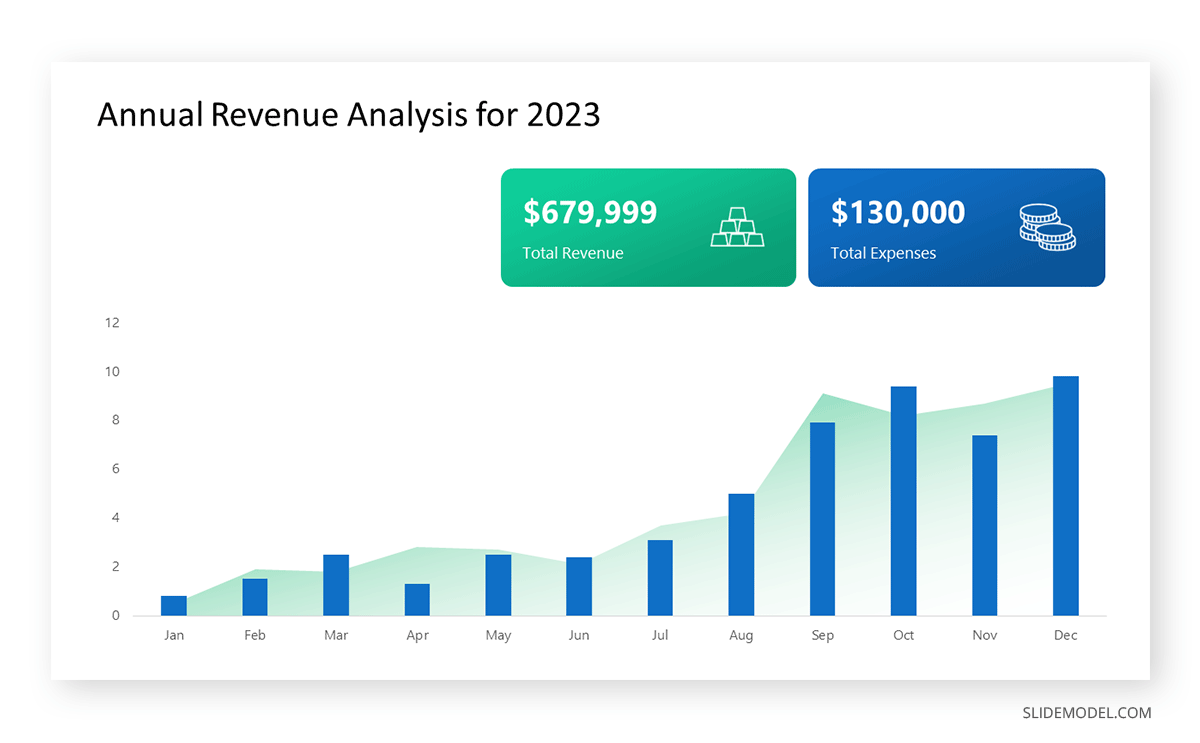

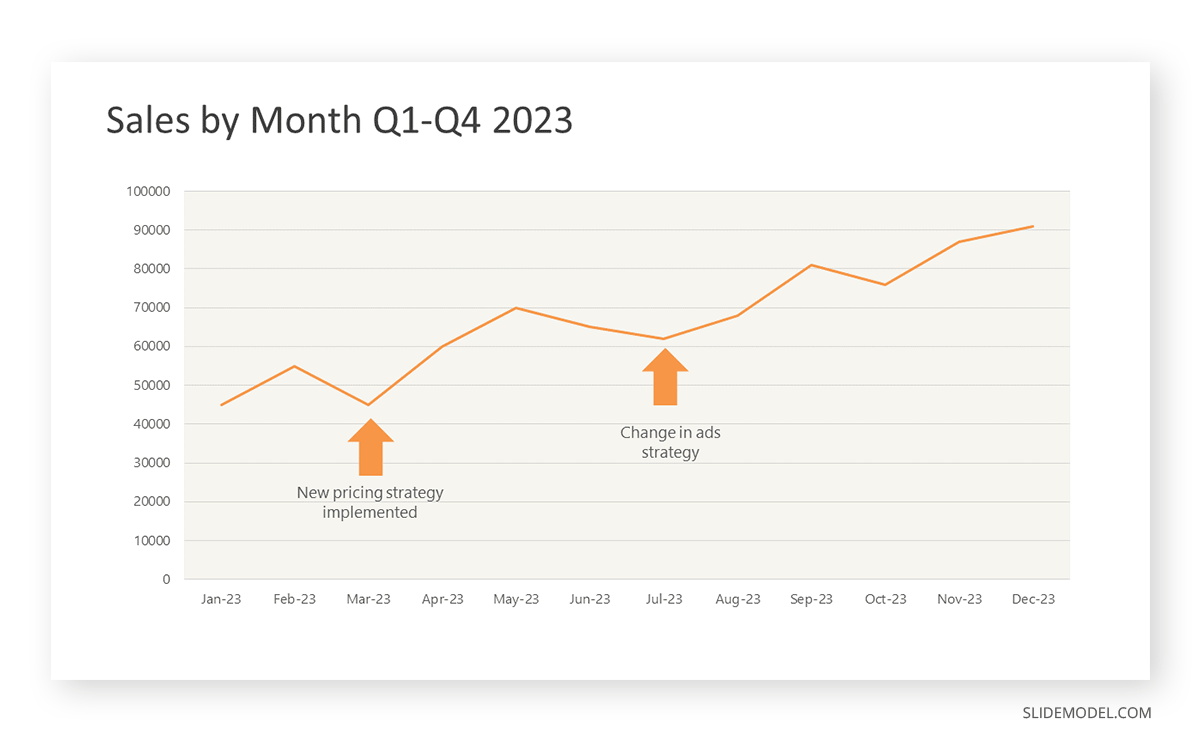

Line graphs help illustrate data trends, progressions, or fluctuations by connecting a series of data points called ‘markers’ with straight line segments. This provides a straightforward representation of how values change [5] . Their versatility makes them invaluable for scenarios requiring a visual understanding of continuous data. In addition, line graphs are also useful for comparing multiple datasets over the same timeline. Using multiple line graphs allows us to compare more than one data set. They simplify complex information so the audience can quickly grasp the ups and downs of values. From tracking stock prices to analyzing experimental results, you can use line graphs to show how data changes over a continuous timeline. They show trends with simplicity and clarity.

Real-life Application of Line Graphs

To understand line graphs thoroughly, we will use a real case. Imagine you’re a financial analyst presenting a tech company’s monthly sales for a licensed product over the past year. Investors want insights into sales behavior by month, how market trends may have influenced sales performance and reception to the new pricing strategy. To present data via a line graph, you will complete these steps.

First, you need to gather the data. In this case, your data will be the sales numbers. For example:

- January: $45,000

- February: $55,000

- March: $45,000

- April: $60,000

- May: $ 70,000

- June: $65,000

- July: $62,000

- August: $68,000

- September: $81,000

- October: $76,000

- November: $87,000

- December: $91,000

After choosing the data, the next step is to select the orientation. Like bar charts, you can use vertical or horizontal line graphs. However, we want to keep this simple, so we will keep the timeline (x-axis) horizontal while the sales numbers (y-axis) vertical.

Step 3: Connecting Trends

After adding the data to your preferred software, you will plot a line graph. In the graph, each month’s sales are represented by data points connected by a line.

Step 4: Adding Clarity with Color

If there are multiple lines, you can also add colors to highlight each one, making it easier to follow.

Line graphs excel at visually presenting trends over time. These presentation aids identify patterns, like upward or downward trends. However, too many data points can clutter the graph, making it harder to interpret. Line graphs work best with continuous data but are not suitable for categories.

For more information, check our collection of line chart templates for PowerPoint and our article about how to make a presentation graph .

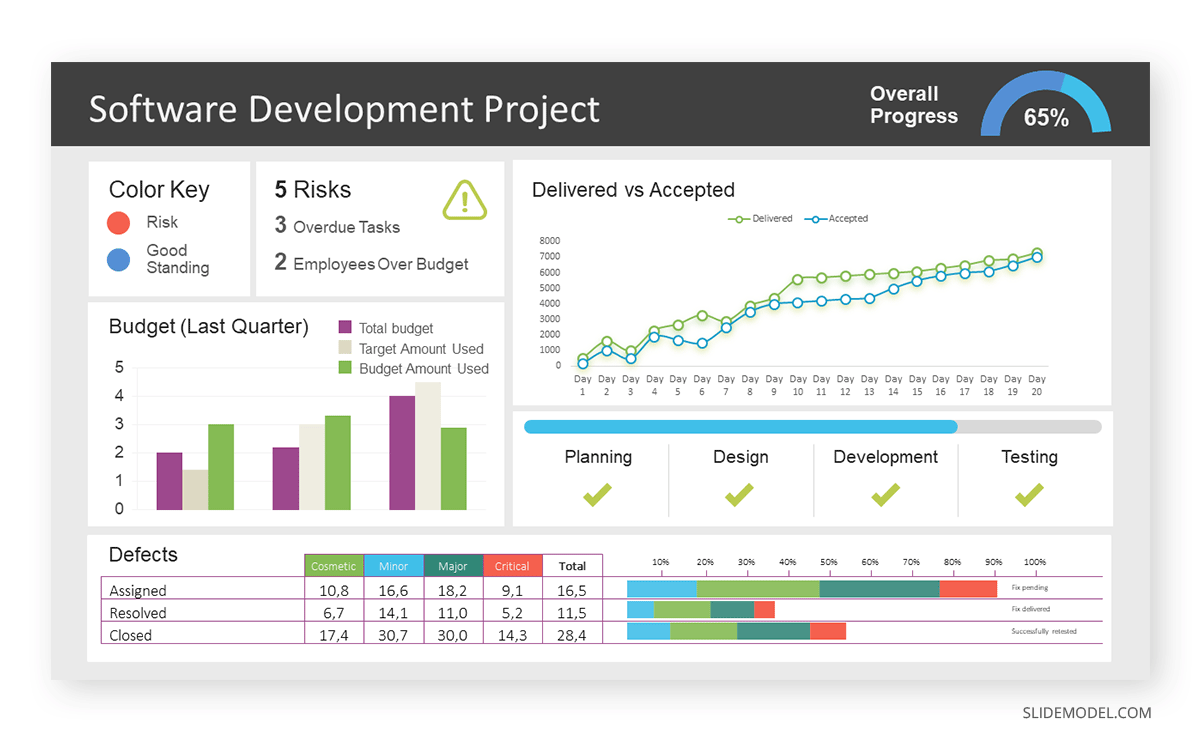

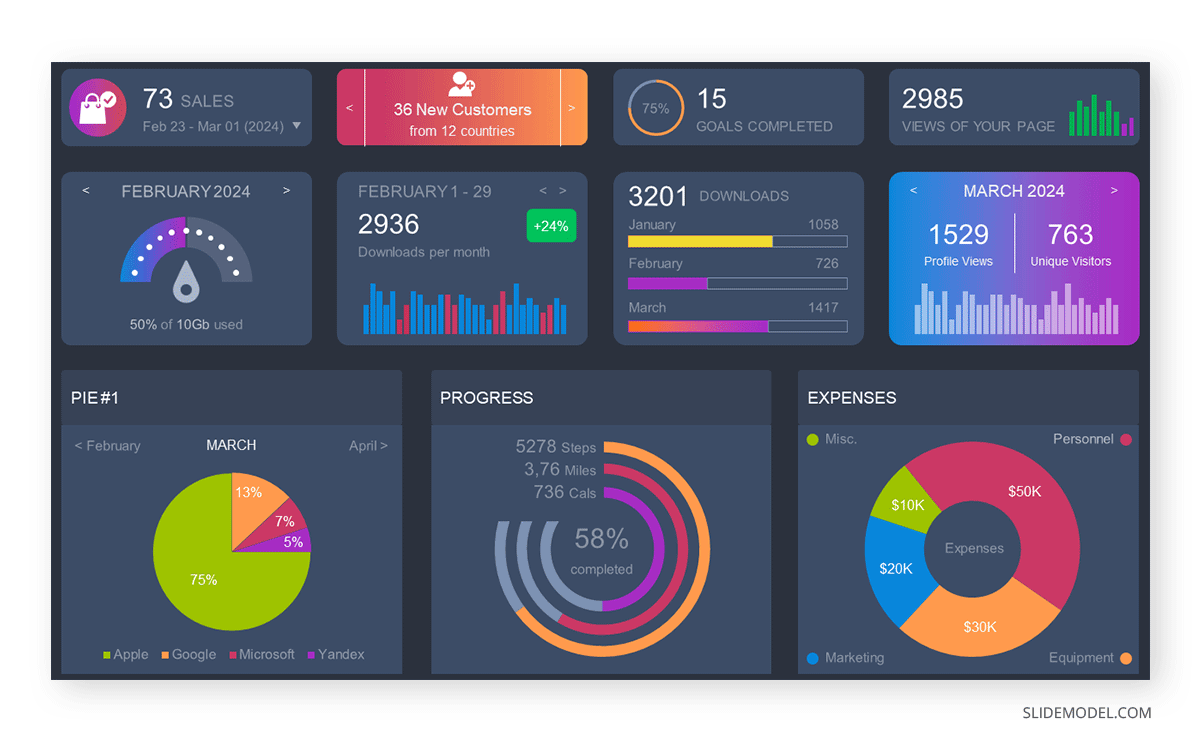

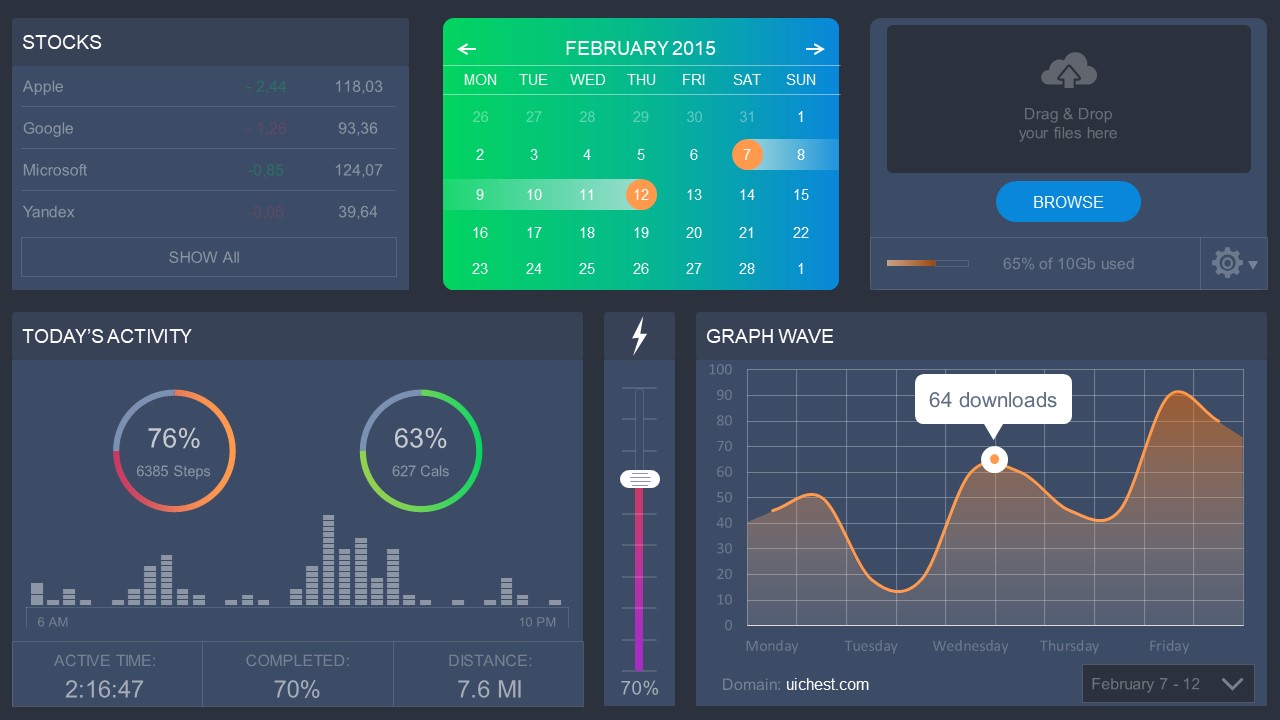

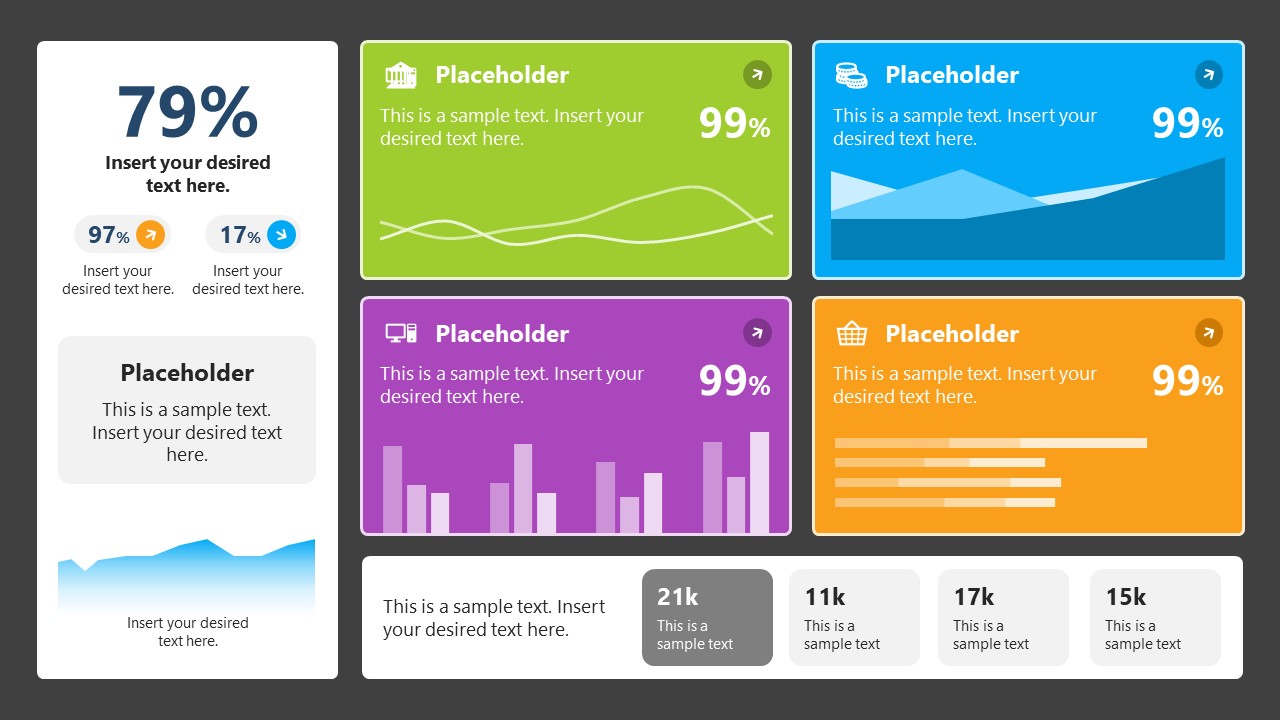

A data dashboard is a visual tool for analyzing information. Different graphs, charts, and tables are consolidated in a layout to showcase the information required to achieve one or more objectives. Dashboards help quickly see Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). You don’t make new visuals in the dashboard; instead, you use it to display visuals you’ve already made in worksheets [3] .

Keeping the number of visuals on a dashboard to three or four is recommended. Adding too many can make it hard to see the main points [4]. Dashboards can be used for business analytics to analyze sales, revenue, and marketing metrics at a time. They are also used in the manufacturing industry, as they allow users to grasp the entire production scenario at the moment while tracking the core KPIs for each line.

Real-Life Application of a Dashboard

Consider a project manager presenting a software development project’s progress to a tech company’s leadership team. He follows the following steps.

Step 1: Defining Key Metrics

To effectively communicate the project’s status, identify key metrics such as completion status, budget, and bug resolution rates. Then, choose measurable metrics aligned with project objectives.

Step 2: Choosing Visualization Widgets

After finalizing the data, presentation aids that align with each metric are selected. For this project, the project manager chooses a progress bar for the completion status and uses bar charts for budget allocation. Likewise, he implements line charts for bug resolution rates.

Step 3: Dashboard Layout

Key metrics are prominently placed in the dashboard for easy visibility, and the manager ensures that it appears clean and organized.

Dashboards provide a comprehensive view of key project metrics. Users can interact with data, customize views, and drill down for detailed analysis. However, creating an effective dashboard requires careful planning to avoid clutter. Besides, dashboards rely on the availability and accuracy of underlying data sources.

For more information, check our article on how to design a dashboard presentation , and discover our collection of dashboard PowerPoint templates .

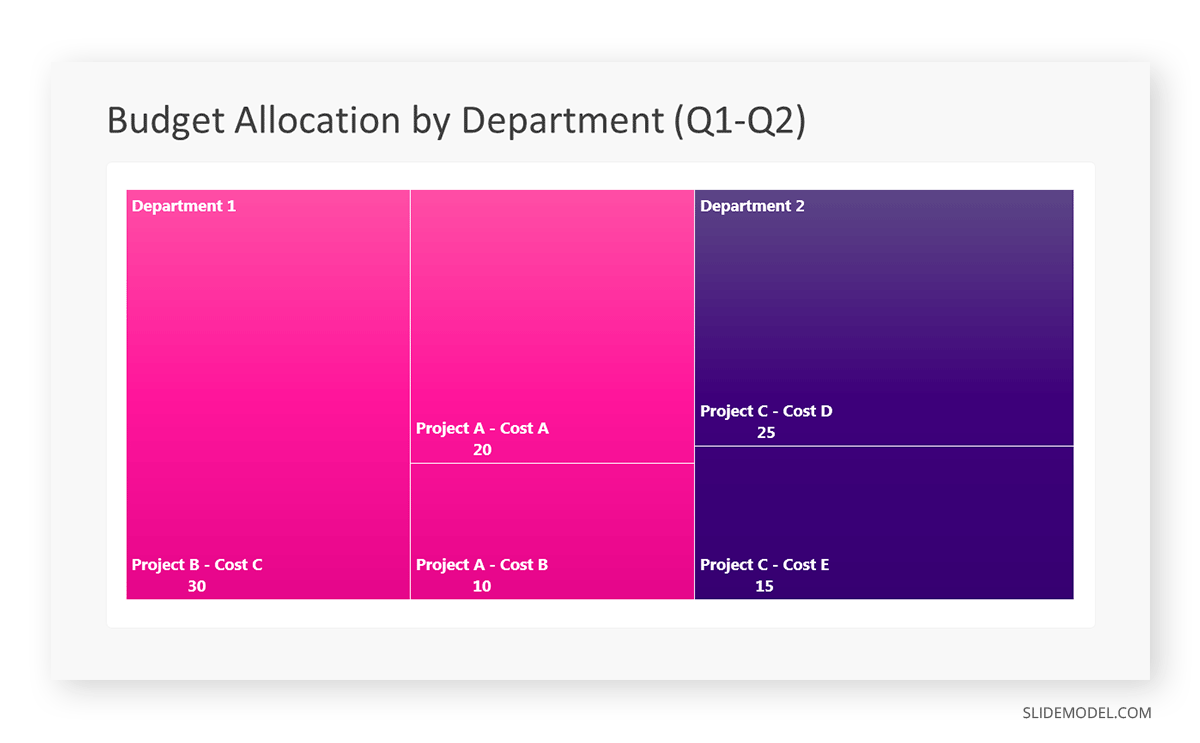

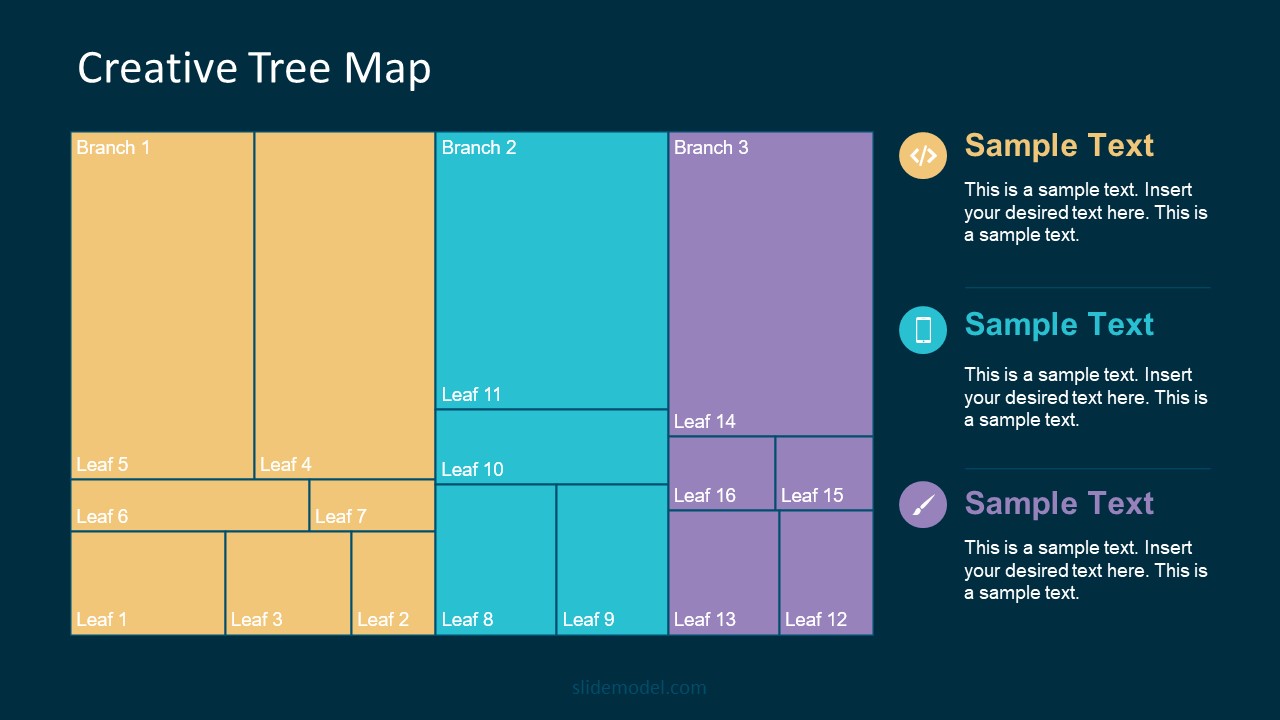

Treemap charts represent hierarchical data structured in a series of nested rectangles [6] . As each branch of the ‘tree’ is given a rectangle, smaller tiles can be seen representing sub-branches, meaning elements on a lower hierarchical level than the parent rectangle. Each one of those rectangular nodes is built by representing an area proportional to the specified data dimension.

Treemaps are useful for visualizing large datasets in compact space. It is easy to identify patterns, such as which categories are dominant. Common applications of the treemap chart are seen in the IT industry, such as resource allocation, disk space management, website analytics, etc. Also, they can be used in multiple industries like healthcare data analysis, market share across different product categories, or even in finance to visualize portfolios.

Real-Life Application of a Treemap Chart

Let’s consider a financial scenario where a financial team wants to represent the budget allocation of a company. There is a hierarchy in the process, so it is helpful to use a treemap chart. In the chart, the top-level rectangle could represent the total budget, and it would be subdivided into smaller rectangles, each denoting a specific department. Further subdivisions within these smaller rectangles might represent individual projects or cost categories.

Step 1: Define Your Data Hierarchy

While presenting data on the budget allocation, start by outlining the hierarchical structure. The sequence will be like the overall budget at the top, followed by departments, projects within each department, and finally, individual cost categories for each project.

- Top-level rectangle: Total Budget

- Second-level rectangles: Departments (Engineering, Marketing, Sales)

- Third-level rectangles: Projects within each department

- Fourth-level rectangles: Cost categories for each project (Personnel, Marketing Expenses, Equipment)

Step 2: Choose a Suitable Tool

It’s time to select a data visualization tool supporting Treemaps. Popular choices include Tableau, Microsoft Power BI, PowerPoint, or even coding with libraries like D3.js. It is vital to ensure that the chosen tool provides customization options for colors, labels, and hierarchical structures.

Here, the team uses PowerPoint for this guide because of its user-friendly interface and robust Treemap capabilities.

Step 3: Make a Treemap Chart with PowerPoint

After opening the PowerPoint presentation, they chose “SmartArt” to form the chart. The SmartArt Graphic window has a “Hierarchy” category on the left. Here, you will see multiple options. You can choose any layout that resembles a Treemap. The “Table Hierarchy” or “Organization Chart” options can be adapted. The team selects the Table Hierarchy as it looks close to a Treemap.

Step 5: Input Your Data

After that, a new window will open with a basic structure. They add the data one by one by clicking on the text boxes. They start with the top-level rectangle, representing the total budget.

Step 6: Customize the Treemap

By clicking on each shape, they customize its color, size, and label. At the same time, they can adjust the font size, style, and color of labels by using the options in the “Format” tab in PowerPoint. Using different colors for each level enhances the visual difference.

Treemaps excel at illustrating hierarchical structures. These charts make it easy to understand relationships and dependencies. They efficiently use space, compactly displaying a large amount of data, reducing the need for excessive scrolling or navigation. Additionally, using colors enhances the understanding of data by representing different variables or categories.

In some cases, treemaps might become complex, especially with deep hierarchies. It becomes challenging for some users to interpret the chart. At the same time, displaying detailed information within each rectangle might be constrained by space. It potentially limits the amount of data that can be shown clearly. Without proper labeling and color coding, there’s a risk of misinterpretation.

A heatmap is a data visualization tool that uses color coding to represent values across a two-dimensional surface. In these, colors replace numbers to indicate the magnitude of each cell. This color-shaded matrix display is valuable for summarizing and understanding data sets with a glance [7] . The intensity of the color corresponds to the value it represents, making it easy to identify patterns, trends, and variations in the data.

As a tool, heatmaps help businesses analyze website interactions, revealing user behavior patterns and preferences to enhance overall user experience. In addition, companies use heatmaps to assess content engagement, identifying popular sections and areas of improvement for more effective communication. They excel at highlighting patterns and trends in large datasets, making it easy to identify areas of interest.

We can implement heatmaps to express multiple data types, such as numerical values, percentages, or even categorical data. Heatmaps help us easily spot areas with lots of activity, making them helpful in figuring out clusters [8] . When making these maps, it is important to pick colors carefully. The colors need to show the differences between groups or levels of something. And it is good to use colors that people with colorblindness can easily see.

Check our detailed guide on how to create a heatmap here. Also discover our collection of heatmap PowerPoint templates .

Pie charts are circular statistical graphics divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportions. Each slice represents a proportionate part of the whole, making it easy to visualize the contribution of each component to the total.

The size of the pie charts is influenced by the value of data points within each pie. The total of all data points in a pie determines its size. The pie with the highest data points appears as the largest, whereas the others are proportionally smaller. However, you can present all pies of the same size if proportional representation is not required [9] . Sometimes, pie charts are difficult to read, or additional information is required. A variation of this tool can be used instead, known as the donut chart , which has the same structure but a blank center, creating a ring shape. Presenters can add extra information, and the ring shape helps to declutter the graph.

Pie charts are used in business to show percentage distribution, compare relative sizes of categories, or present straightforward data sets where visualizing ratios is essential.

Real-Life Application of Pie Charts

Consider a scenario where you want to represent the distribution of the data. Each slice of the pie chart would represent a different category, and the size of each slice would indicate the percentage of the total portion allocated to that category.

Step 1: Define Your Data Structure

Imagine you are presenting the distribution of a project budget among different expense categories.

- Column A: Expense Categories (Personnel, Equipment, Marketing, Miscellaneous)

- Column B: Budget Amounts ($40,000, $30,000, $20,000, $10,000) Column B represents the values of your categories in Column A.

Step 2: Insert a Pie Chart

Using any of the accessible tools, you can create a pie chart. The most convenient tools for forming a pie chart in a presentation are presentation tools such as PowerPoint or Google Slides. You will notice that the pie chart assigns each expense category a percentage of the total budget by dividing it by the total budget.

For instance:

- Personnel: $40,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 40%

- Equipment: $30,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 30%

- Marketing: $20,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 20%

- Miscellaneous: $10,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 10%

You can make a chart out of this or just pull out the pie chart from the data.

3D pie charts and 3D donut charts are quite popular among the audience. They stand out as visual elements in any presentation slide, so let’s take a look at how our pie chart example would look in 3D pie chart format.

Step 03: Results Interpretation

The pie chart visually illustrates the distribution of the project budget among different expense categories. Personnel constitutes the largest portion at 40%, followed by equipment at 30%, marketing at 20%, and miscellaneous at 10%. This breakdown provides a clear overview of where the project funds are allocated, which helps in informed decision-making and resource management. It is evident that personnel are a significant investment, emphasizing their importance in the overall project budget.

Pie charts provide a straightforward way to represent proportions and percentages. They are easy to understand, even for individuals with limited data analysis experience. These charts work well for small datasets with a limited number of categories.

However, a pie chart can become cluttered and less effective in situations with many categories. Accurate interpretation may be challenging, especially when dealing with slight differences in slice sizes. In addition, these charts are static and do not effectively convey trends over time.

For more information, check our collection of pie chart templates for PowerPoint .

Histograms present the distribution of numerical variables. Unlike a bar chart that records each unique response separately, histograms organize numeric responses into bins and show the frequency of reactions within each bin [10] . The x-axis of a histogram shows the range of values for a numeric variable. At the same time, the y-axis indicates the relative frequencies (percentage of the total counts) for that range of values.

Whenever you want to understand the distribution of your data, check which values are more common, or identify outliers, histograms are your go-to. Think of them as a spotlight on the story your data is telling. A histogram can provide a quick and insightful overview if you’re curious about exam scores, sales figures, or any numerical data distribution.

Real-Life Application of a Histogram

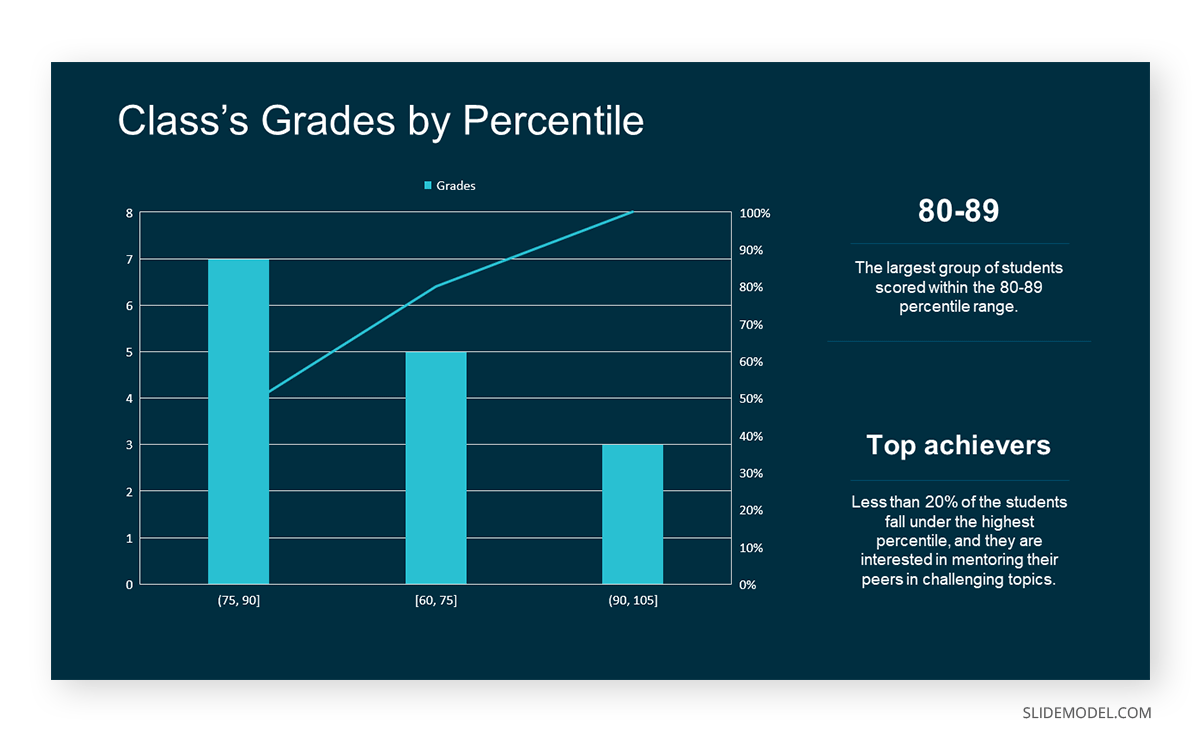

In the histogram data analysis presentation example, imagine an instructor analyzing a class’s grades to identify the most common score range. A histogram could effectively display the distribution. It will show whether most students scored in the average range or if there are significant outliers.

Step 1: Gather Data

He begins by gathering the data. The scores of each student in class are gathered to analyze exam scores.

After arranging the scores in ascending order, bin ranges are set.

Step 2: Define Bins

Bins are like categories that group similar values. Think of them as buckets that organize your data. The presenter decides how wide each bin should be based on the range of the values. For instance, the instructor sets the bin ranges based on score intervals: 60-69, 70-79, 80-89, and 90-100.

Step 3: Count Frequency

Now, he counts how many data points fall into each bin. This step is crucial because it tells you how often specific ranges of values occur. The result is the frequency distribution, showing the occurrences of each group.

Here, the instructor counts the number of students in each category.

- 60-69: 1 student (Kate)

- 70-79: 4 students (David, Emma, Grace, Jack)

- 80-89: 7 students (Alice, Bob, Frank, Isabel, Liam, Mia, Noah)

- 90-100: 3 students (Clara, Henry, Olivia)

Step 4: Create the Histogram

It’s time to turn the data into a visual representation. Draw a bar for each bin on a graph. The width of the bar should correspond to the range of the bin, and the height should correspond to the frequency. To make your histogram understandable, label the X and Y axes.

In this case, the X-axis should represent the bins (e.g., test score ranges), and the Y-axis represents the frequency.

The histogram of the class grades reveals insightful patterns in the distribution. Most students, with seven students, fall within the 80-89 score range. The histogram provides a clear visualization of the class’s performance. It showcases a concentration of grades in the upper-middle range with few outliers at both ends. This analysis helps in understanding the overall academic standing of the class. It also identifies the areas for potential improvement or recognition.

Thus, histograms provide a clear visual representation of data distribution. They are easy to interpret, even for those without a statistical background. They apply to various types of data, including continuous and discrete variables. One weak point is that histograms do not capture detailed patterns in students’ data, with seven compared to other visualization methods.

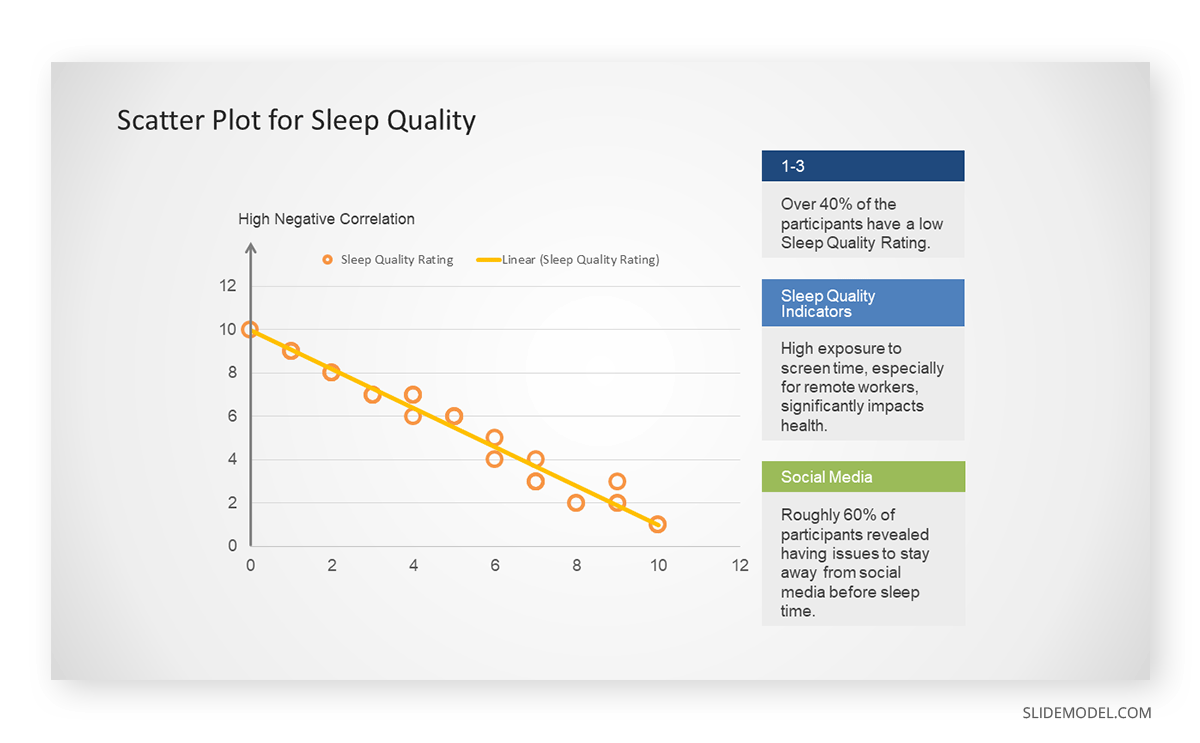

A scatter plot is a graphical representation of the relationship between two variables. It consists of individual data points on a two-dimensional plane. This plane plots one variable on the x-axis and the other on the y-axis. Each point represents a unique observation. It visualizes patterns, trends, or correlations between the two variables.

Scatter plots are also effective in revealing the strength and direction of relationships. They identify outliers and assess the overall distribution of data points. The points’ dispersion and clustering reflect the relationship’s nature, whether it is positive, negative, or lacks a discernible pattern. In business, scatter plots assess relationships between variables such as marketing cost and sales revenue. They help present data correlations and decision-making.

Real-Life Application of Scatter Plot

A group of scientists is conducting a study on the relationship between daily hours of screen time and sleep quality. After reviewing the data, they managed to create this table to help them build a scatter plot graph:

In the provided example, the x-axis represents Daily Hours of Screen Time, and the y-axis represents the Sleep Quality Rating.

The scientists observe a negative correlation between the amount of screen time and the quality of sleep. This is consistent with their hypothesis that blue light, especially before bedtime, has a significant impact on sleep quality and metabolic processes.

There are a few things to remember when using a scatter plot. Even when a scatter diagram indicates a relationship, it doesn’t mean one variable affects the other. A third factor can influence both variables. The more the plot resembles a straight line, the stronger the relationship is perceived [11] . If it suggests no ties, the observed pattern might be due to random fluctuations in data. When the scatter diagram depicts no correlation, whether the data might be stratified is worth considering.

Choosing the appropriate data presentation type is crucial when making a presentation . Understanding the nature of your data and the message you intend to convey will guide this selection process. For instance, when showcasing quantitative relationships, scatter plots become instrumental in revealing correlations between variables. If the focus is on emphasizing parts of a whole, pie charts offer a concise display of proportions. Histograms, on the other hand, prove valuable for illustrating distributions and frequency patterns.

Bar charts provide a clear visual comparison of different categories. Likewise, line charts excel in showcasing trends over time, while tables are ideal for detailed data examination. Starting a presentation on data presentation types involves evaluating the specific information you want to communicate and selecting the format that aligns with your message. This ensures clarity and resonance with your audience from the beginning of your presentation.

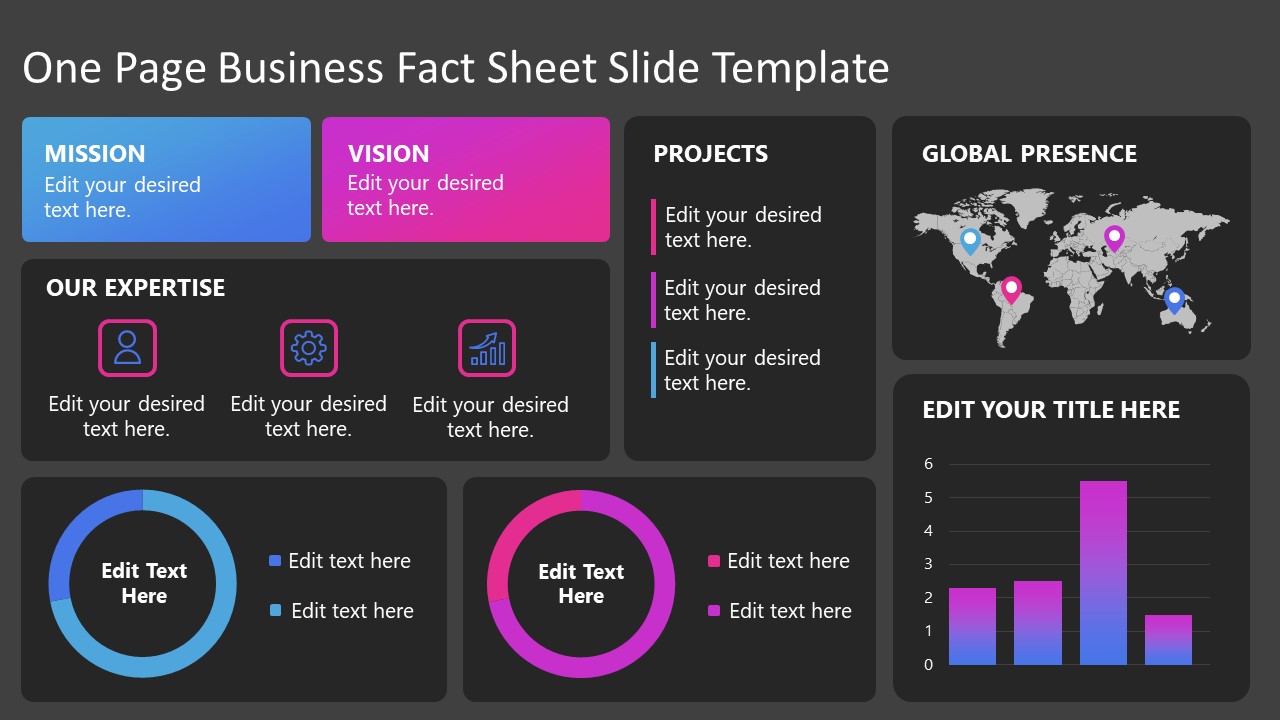

1. Fact Sheet Dashboard for Data Presentation

Convey all the data you need to present in this one-pager format, an ideal solution tailored for users looking for presentation aids. Global maps, donut chats, column graphs, and text neatly arranged in a clean layout presented in light and dark themes.

Use This Template

2. 3D Column Chart Infographic PPT Template

Represent column charts in a highly visual 3D format with this PPT template. A creative way to present data, this template is entirely editable, and we can craft either a one-page infographic or a series of slides explaining what we intend to disclose point by point.

3. Data Circles Infographic PowerPoint Template

An alternative to the pie chart and donut chart diagrams, this template features a series of curved shapes with bubble callouts as ways of presenting data. Expand the information for each arch in the text placeholder areas.

4. Colorful Metrics Dashboard for Data Presentation

This versatile dashboard template helps us in the presentation of the data by offering several graphs and methods to convert numbers into graphics. Implement it for e-commerce projects, financial projections, project development, and more.

5. Animated Data Presentation Tools for PowerPoint & Google Slides

A slide deck filled with most of the tools mentioned in this article, from bar charts, column charts, treemap graphs, pie charts, histogram, etc. Animated effects make each slide look dynamic when sharing data with stakeholders.

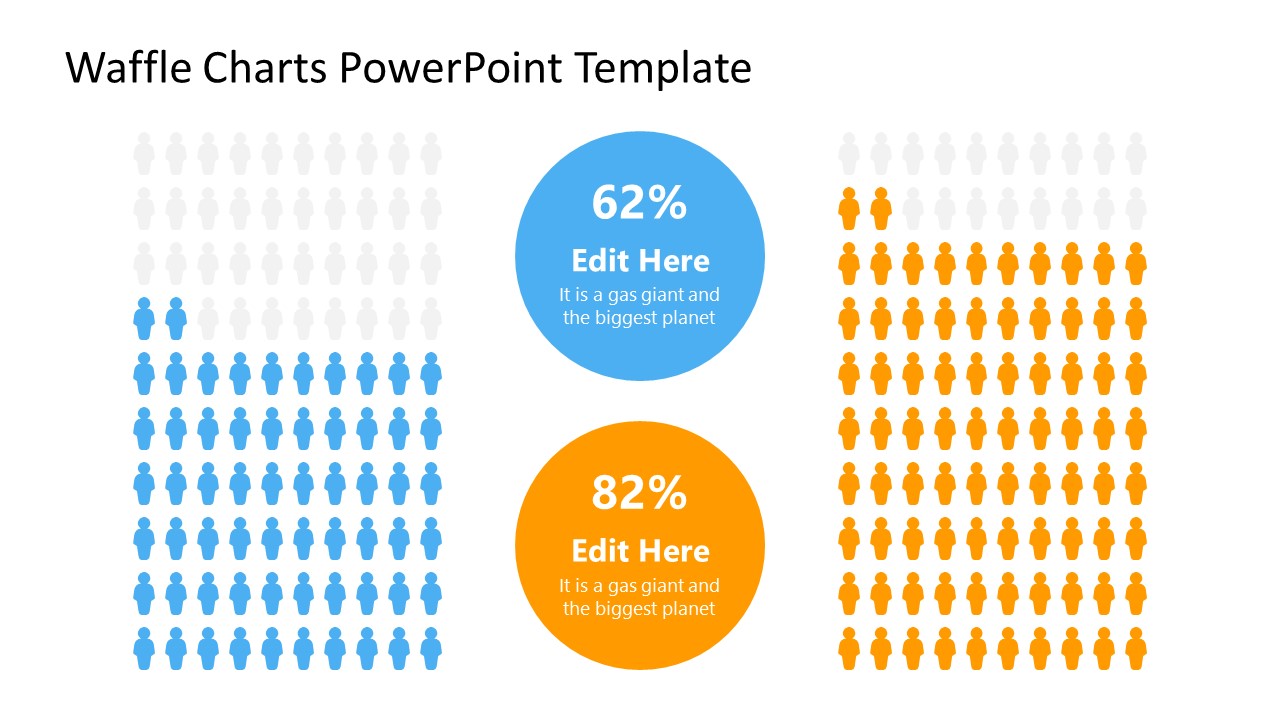

6. Statistics Waffle Charts PPT Template for Data Presentations

This PPT template helps us how to present data beyond the typical pie chart representation. It is widely used for demographics, so it’s a great fit for marketing teams, data science professionals, HR personnel, and more.

7. Data Presentation Dashboard Template for Google Slides

A compendium of tools in dashboard format featuring line graphs, bar charts, column charts, and neatly arranged placeholder text areas.

8. Weather Dashboard for Data Presentation

Share weather data for agricultural presentation topics, environmental studies, or any kind of presentation that requires a highly visual layout for weather forecasting on a single day. Two color themes are available.

9. Social Media Marketing Dashboard Data Presentation Template

Intended for marketing professionals, this dashboard template for data presentation is a tool for presenting data analytics from social media channels. Two slide layouts featuring line graphs and column charts.

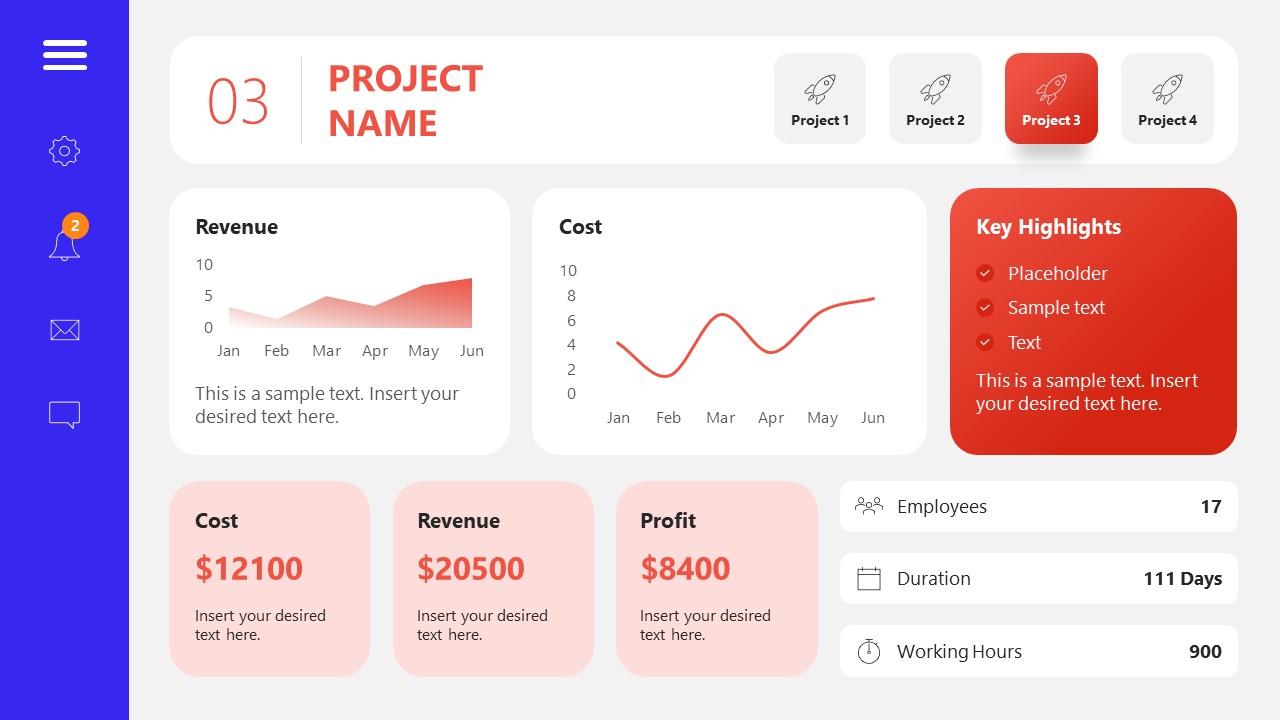

10. Project Management Summary Dashboard Template

A tool crafted for project managers to deliver highly visual reports on a project’s completion, the profits it delivered for the company, and expenses/time required to execute it. 4 different color layouts are available.

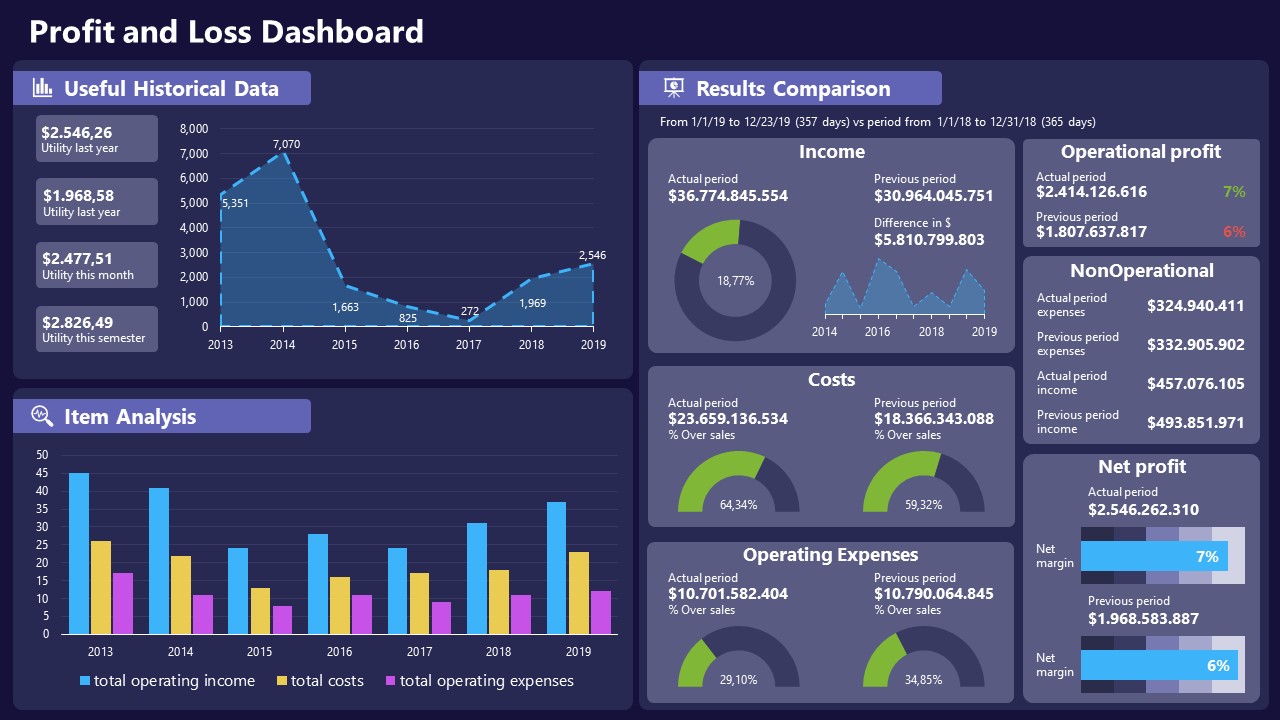

11. Profit & Loss Dashboard for PowerPoint and Google Slides

A must-have for finance professionals. This typical profit & loss dashboard includes progress bars, donut charts, column charts, line graphs, and everything that’s required to deliver a comprehensive report about a company’s financial situation.

Overwhelming visuals

One of the mistakes related to using data-presenting methods is including too much data or using overly complex visualizations. They can confuse the audience and dilute the key message.

Inappropriate chart types

Choosing the wrong type of chart for the data at hand can lead to misinterpretation. For example, using a pie chart for data that doesn’t represent parts of a whole is not right.

Lack of context

Failing to provide context or sufficient labeling can make it challenging for the audience to understand the significance of the presented data.

Inconsistency in design

Using inconsistent design elements and color schemes across different visualizations can create confusion and visual disarray.

Failure to provide details

Simply presenting raw data without offering clear insights or takeaways can leave the audience without a meaningful conclusion.

Lack of focus

Not having a clear focus on the key message or main takeaway can result in a presentation that lacks a central theme.

Visual accessibility issues

Overlooking the visual accessibility of charts and graphs can exclude certain audience members who may have difficulty interpreting visual information.

In order to avoid these mistakes in data presentation, presenters can benefit from using presentation templates . These templates provide a structured framework. They ensure consistency, clarity, and an aesthetically pleasing design, enhancing data communication’s overall impact.

Understanding and choosing data presentation types are pivotal in effective communication. Each method serves a unique purpose, so selecting the appropriate one depends on the nature of the data and the message to be conveyed. The diverse array of presentation types offers versatility in visually representing information, from bar charts showing values to pie charts illustrating proportions.

Using the proper method enhances clarity, engages the audience, and ensures that data sets are not just presented but comprehensively understood. By appreciating the strengths and limitations of different presentation types, communicators can tailor their approach to convey information accurately, developing a deeper connection between data and audience understanding.

[1] Government of Canada, S.C. (2021) 5 Data Visualization 5.2 Bar Chart , 5.2 Bar chart . https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/edu/power-pouvoir/ch9/bargraph-diagrammeabarres/5214818-eng.htm

[2] Kosslyn, S.M., 1989. Understanding charts and graphs. Applied cognitive psychology, 3(3), pp.185-225. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA183409.pdf

[3] Creating a Dashboard . https://it.tufts.edu/book/export/html/1870

[4] https://www.goldenwestcollege.edu/research/data-and-more/data-dashboards/index.html

[5] https://www.mit.edu/course/21/21.guide/grf-line.htm

[6] Jadeja, M. and Shah, K., 2015, January. Tree-Map: A Visualization Tool for Large Data. In GSB@ SIGIR (pp. 9-13). https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1393/gsb15proceedings.pdf#page=15

[7] Heat Maps and Quilt Plots. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/heat-maps-and-quilt-plots

[8] EIU QGIS WORKSHOP. https://www.eiu.edu/qgisworkshop/heatmaps.php

[9] About Pie Charts. https://www.mit.edu/~mbarker/formula1/f1help/11-ch-c8.htm

[10] Histograms. https://sites.utexas.edu/sos/guided/descriptive/numericaldd/descriptiven2/histogram/ [11] https://asq.org/quality-resources/scatter-diagram

Like this article? Please share

Data Analysis, Data Science, Data Visualization Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under Presentation Ideas • January 6th, 2024

All About Using Harvey Balls

Among the many tools in the arsenal of the modern presenter, Harvey Balls have a special place. In this article we will tell you all about using Harvey Balls.

Filed under Business • December 8th, 2023

How to Design a Dashboard Presentation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Take a step further in your professional presentation skills by learning what a dashboard presentation is and how to properly design one in PowerPoint. A detailed step-by-step guide is here!

Leave a Reply

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Surg Infect (Larchmt)

Basic Introduction to Statistics in Medicine, Part 1: Describing Data

Wyatt p. bensken.

1 Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Fredric M. Pieracci

2 Department of Surgery, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Vanessa P. Ho

3 Department of Surgery, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Background: Standardized and concise data presentation forms the base for subsequent analysis and interpretation. This article reviews types of data, data properties and distributions, and both numerical and graphical methods of data presentation.

Methods: For the purposes of illustration, the National Inpatient Sample was queried to categorize patients as having either emergency general surgery or non-emergency general surgery admissions.

Results: Variables are categorized as either categorical or numerical. Within the former, there are ordinal and or nominal subtypes; within the latter, there are ratio and interval subtypes. Categorical data are typically displayed as number (%). Numerical data must be assessed for normality as normally distributed data behave in certain patterns that allow for specific statistical tests to be used. Several properties exist for numerical data, including measurements of central tendency (mean, median, and mode), as well as standard deviation, range, and interquartile range. The best initial assessment of the distribution of numerical data is graphical with both histograms and box plots.

Conclusion: Knowledge of the types, distribution, and properties of data is essential to move forward with hypothesis testing.

Counting and measurement is the basis of all research and accurate representation of numeric data ensures that research is systematic and reproducible. After the design of a research study, the most critical juncture in a project is a complete and accurate description of the data and the methods used to obtain the results. Utilizing a systematic description of the data as a first step not only ensures transparent reporting of results, but helps the investigator identify potential problems in their analytic process or data sources to guide analytic decisions. Examining the distribution and structure of data ensures that the test and analyses chosen are the most appropriate and statistically valid. In addition to aiding the investigator, a clear description of the methods and data will aid in peer review and the study's utility in the broader research enterprise. Specifically, the description helps readers to understand external validity of a particular study, in other words, are findings generalizable to other populations? When drafting a manuscript, the description of data presentation and analysis should be standardized to the point where, after reading it, an independent party could reproduce your results exactly.

There are two cornerstones to an appropriate description of data: (1) a well-developed and presented table that describes your population, often referred to as a demographics table or Table 1 and (2) data visualization with appropriately chosen graphics. In this article, we provide examples of how to describe and visualize data using a nationally representative database, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, to demonstrate a robust and thorough description of the methods and data used, while also highlighting specific pitfalls. We also demonstrate how weighted databases may add an extra layer of complexity to describing your study population. It is our goal that this work provides a road map for investigators seeking to utilize best practices in describing and presenting their data.

Types of Quantitative Data

To demonstrate these data science statistical practices and pitfalls, we used data from the 2017 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is an approximately 20% sample of all-payer hospitalizations that are included as part of HCUP that are then weighted to provide national estimates. This weighting means that each observed hospitalization in the sample represents a specific number of hospitalizations in the population. With this, the sample of 7.1 million hospitalizations represents more than 35.7 million hospitalizations. It includes parameters covering patient demographics (race, gender, age, payer, etc.), admission and discharge status, diagnoses, procedures, length of stay (LOS), and cost. All data are at the discharge-level and the NIS does not provide patient identifiers to be able to link hospitalizations. In this study we identified patients who underwent emergency general surgery (EGS) in 2017. Here, EGS is defined as appendectomy, colectomy and colostomy, laparotomy, laparoscopy, lysis of adhesions, small bowel resection, ulcer repair, and gallbladder procedures, as previously described by Smith et al. [ 1 ]. Specifically, we required that the hospitalization contain both a diagnosis and procedure code for EGS.

Of note, NIS data are structured to be able to perform a weighted adjustment to establish a nationally representative sample. For this article, however, the only weighted analysis we present is for the overall number of EGS procedures. This weighting followed guidelines from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) using the given weights, cluster, and strata. Because of this weighting, the national estimates are presented with standard errors. Data cleaning was done via SAS, version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with visualizations made in R version 3.6.1 using the tidyverse and patchwork packages [ 2 , 3 ]. Sample data available online were also used to build the skewed distributions in Figure 1 [ 4 ].

Example of normal and skewed distributions, using simulated data.

Using these data, we demonstrate how to construct a demographics table or Table 1 while also showing the value of graphical visualization of data to illustrate the distribution of age and LOS. The 2017 NIS contained 7,159,694 admissions that, when weighted, represent a national estimate of 35,798,453 hospitalizations. There was a total of 11,034 (1.6%) hospitalizations for emergency general surgery (EGS), representing an estimated 555,170 ± 5,969 (1.6% ± 0.01) nationally in 2017.

Data Cleaning and Categorization for Analysis

Data collection is typically organized via a data table, spreadsheet, or data frame. These datasets are typically organized such that each row of data represents one observation or unit to be studied (such as a single patient, one admission, or a hospital) and each column of data is a collected parameter (such as age or sex). Broadly, there are two types of variables: categorical (nominal and ordinal) and numeric (interval and ratio) ( Table 1 ). Categorical data represent named groups of observations and are not quantitative. Categorical data can be ordered (ordinal) or not ordered (nominal). In our example below, represented by Table 2 , gender, race, payer, and disposition are examples of categorical nominal variables. In the below example, the age categories (<18 years, 18–34, 35–49, etc.) are examples of ordered categorical variables.

Table of Demographics

Description of the study population, comparing those hospitalization not for EGS and those for EGS. These data come from the 2017 Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Note that two cells are presented as “<” (less than); this is due to data restrictions of displaying cells less than 11.

EGS = emergency general surgery; SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range; LOS = length of stay; SNF = skilled nursing facility; ICF = intermediate care facility.

Numerical data are collected as numbers. Length of stay is an example of numerical data. Length of stay is a continuous variable, meaning that it is a measure of length, represented by the unit “days” and usually rounded to the nearest integer. Length of stay is also an example of “ratio” data, whereby the numbers are meaningfully related and zero is an absolute number. In other words, a person who had a LOS of 6 days was in the hospital twice as long as a person in the hospital for 3 days, and no one has a negative LOS. This differs from interval data. Interval data are characterized by numbers that have equal distances between values but there is no fixed beginning. An example of this is time in a 12-hour clock. These distinctions are important because some numbers should not be added or subtracted, and only ratio data can be interpreted as multiples of each other. Some numeric data should not be treated as continuous, such as injury severity scale (ISS) because an ISS of 20 is not twice as bad as an ISS of 10. Furthermore, other seemingly numeric data do not even represent numbers, such as medical record number or zip code, which should be considered categorical data because the numbers are really only assigned labels.

Numerical data can be converted to categories if the researchers believe this conversion is appropriate. However, it is important to remember that converting data from continuous to categorical necessarily results in loss of information granularity. This may limit future analyses. Age is a continuous numerical variable that consists of ratio data. In Table 2 , age is described multiple ways. As continuous numerical data, age can be represented as a distribution with a mean and standard deviation, or a median and interquartile range. Alternatively, age was also converted into a categorical ordinal variable. We elected to present standard groups, namely, <18, 18–34, 35–49, 40–64, 65–79, 80+. These groups are not even intervals but are socially representative of groups that have similar attributes (child, young adult, etc.); another way to categorize age might be by deciles. Yet another way to group numerical data would be into those either above or below the median value for that parameter. Finally, numerical data may be grouped into categories to replicate findings from previous research, in which certain groupings were found to be meaningful. The researchers can decide which data presentation is most appropriate for their study and study question, and whether “cutting” numeric data into categories is useful or advantageous to demonstrate specific concepts being studied.

Data distribution and properties