Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Remote Teaching: A Student's Perspective

By a purdue student.

As many teachers are well aware, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 required sudden, drastic changes to course curricula. What they may not be aware of are all of the many ways in which this has affected and complicated students’ learning and their academic experiences. This essay, which is written by a student enrolled in several Spring and Summer 2020 remote courses at Purdue University, describes the firsthand experiences (and those of interviewed peers) of participating in remote courses. The aim of this essay is to make teachers aware of the unexpected challenges that remote learning can pose for students.

Emergency remote teaching differs from well-planned online learning

During the past semester, many students and faculty colloquially referred to their courses as “online classes.” While these courses were being taught online, it is nonetheless helpful to distinguish classes that were deliberately designed to be administered online from courses that suddenly shifted online due to an emergency. Perhaps the most significant difference is that students knowingly register for online courses, whereas the switch to remote teaching in spring 2020 was involuntary (though unavoidable). Additionally, online courses are designed in accordance with theoretical and practical standards for teaching in virtual contexts. By contrast, the short transition timeline for implementing online instruction in spring 2020 made applying these standards and preparing instructors next to impossible. As a result, logistical and technical problems were inevitable. I've listed a few of these below.

"...students knowingly register for online courses, whereas the switch to remote teaching in spring 2020 was involuntary..."

Observed Challenges

When teachers are forced to adjust on short notice, some course components may need to be sacrificed..

Two characteristics of high-quality online classes are that their learning outcomes mirror those of in-person classes and that significant time is devoted to course design prior to the beginning of the course. These characteristics ensure the quality of the student learning experience. However, as both students and faculty were given little chance to prepare for the move to remote teaching in spring 2020, adjustments to their learning outcomes were all but unavoidable. Instructors were required to move their courses to a remote teaching format in the span of little over a week during a time when they, like their students, would normally be on break. It was a monumental challenge and one that university faculty rose to meet spectacularly well. However, many components of courses that were originally designed to be taught in person could not be replicated in a remote learning context. Time for the development of contingency plans was limited, which posed additional challenges for the remainder of the semester.

Students' internet connections play a big role in their ability to participate.

At the start of the remote move, many instructors hoped to continue instruction synchronously, but this quickly became infeasible due to technological and logistical issues (e.g., internet bandwidth, student internet access, and time differences). A large number of my fellow students shared internet with other household members, who were also working remotely and were also reliant on conferencing software for meetings. The full-time job of a parent or sibling may be prioritized over a student’s lecture in limited-bandwidth situations. Worse, students in rural areas may simply not have a strong enough connection to participate in synchronous activities at all. These common realities suggest that less technologically reliant contingency plans are necessary and that course material should be made accessible in multiple formats. For example, in addition to offering a video recorded lecture, instructors could also consider providing notes for their lecture.

"These common realities suggest that less technologically reliant contingency plans are necessary and that course material should be made accessible in multiple formats."

It’s also important to design assignments carefully in online courses. For example, group projects, which can pose challenges even when courses are held in person (e.g., in terms of communication, coordination of responsibilities, and access to needed materials), can nevertheless offer students valuable opportunities for personal growth. However, these challenges only become more significant when group projects must be completed remotely. In these cases, access to secure internet and needed materials becomes critical to student success. Partnered students may be in different time zones or may even have been affected by COVID-19 in a way that hampers their ability to contribute to the project. Therefore, teachers may find it advisable to provide students with the option to complete work that would normally constitute group projects as individual assignments.

Teachers underestimate how much harder it is to focus in online courses.

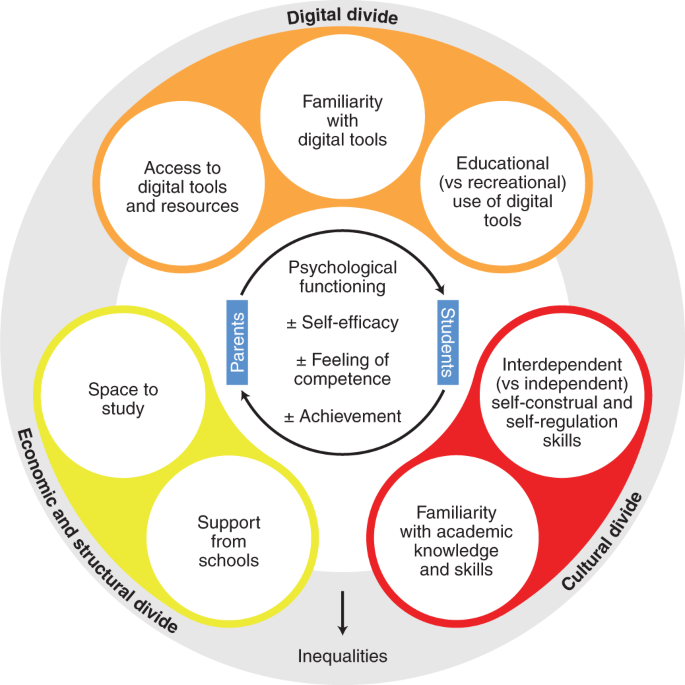

When students no longer share a single learning environment, environmental diffferences can cause significant differences in their engagement. Students forced to use their home as a mixed work/academic space may encounter distractions that wouldn't be a factor in a traditional classroom. These distractions challenge students’ abilities to focus and self-regulate. The shift to remote leadning may also disrupt students’ academic routines. Experts in educational psychology and learning design and technology I spoke to for this piece argued that students’ abilities to handle this transition is partly age-dependent. Older students may not only have more familiarity with online classes, but also with the sort of self-regulation and planning that is required for academic success in the university. Thus, age and course level should be taken into consideration when devising ways to engage, challenge, and support students in remote learning contexts.

"...age and course level should be taken into consideration when devising ways to engage, challenge, and support students in remote learning contexts."

When students are new to taking classes online, explicit prompting from the instructor can be needed to replicate the missing human interactions that normally spur enagagement in the classroom. Thus, it is especially important that instructors closely monitor online learning spaces like discussion boards, looking for appropriate opportunities to chime in. An expert in learning design and technology I spoke to said that instructors should ideally be in touch with their students twice per week. They should frequently outline course expectations and maintain some availability to answer questions. This is especially true in instances where course expectations change due to the shift to online learning. This expert also noted that it is important that instructors provide timely feedback on assignments and assessments. This communicates to students where they stand in their courses and helps students adjust their study strategies as needed.

Students need opportunities to connect and collaborate.

One of the most special parts about being a student at Purdue University is being part of a single large learning community made up of a spectrum of smaller learning communities. At Purdue, students can form bonds with classmates, neighbors, and roommates with a diverse range of skills and interests. Through these friendships and connections, social networks develop, providing emotional and academic support for the many challenges that our rigorous coursework poses.

The closure of the university's physical classrooms created a barrier to the utilization and maintenance of these networks, and it is important that students still have access to one another even when at a distance. One way in which instructors can support their students in remote learning contexts is to create a student-only discussion board on their course page where students can get to know one another and connect. Students may also have questions related to course content that they may feel uncomfortable asking an instructor but that can be easily answered by a classmate.

Many students are dealing with a time change/difference.

For personal reasons, I finished the spring 2020 semester in Europe. Navigating the time difference while juggling the responsibilities of my job, which required synchronous work, and my coursework was challenging (to say the least). One of my courses had a large group project, which was a significant source of stress this past semester. My partner, like many of my instructors, did not seem to understand the significance of this time difference, which often required me to keep a schedule that made daily life in my time zone difficult. When having to make conference calls at 10:00 p.m. and respond to time-sensitive emails well after midnight, work-life balance is much more difficult to achieve. This was abundently clear to me after dealing with time difference of merely six hours. Keep in mind that some students may be dealing with even greater time differences. Thus, try to provide opportunities for asynchronous participation whenever you can.

"Navigating the time difference while juggling the responsibilities of my job, which required synchronous work, and my coursework was challenging (to say the least)"

While flexibility is necessary, academic integrity is still important.

Both teachers and students in my courses expressed discomfort and concern over issues relating to academic integrity. Some students questioned why lockdown browsers (i.e., special browsers used to prevent students from cheating during exams) were not used. According to a learning design and technology expert I spoke to, the short timeline for the transition to remote teaching and learning made the incorporation of such software infeasible. In addition this software can be incredibly expensive, and many professors do not even know that it exists (much less how to use it effectively).

However, several students I spoke with reported that, in their efforts to maintain academic integrity via exam monitoring, some of their professors mandated that students take exams synchronously. This decision disregarded the potential for technical issues and ignored the time differences many students faced, placing unfair stress on students in faraway countries and those with poor connections. Other faculty took an opposite approach by extending the window of time in which students could take exams. Receiving changing and often unclear instructions led to confusion about what students' instructors expected of them. Incorporating this software more consistently in online or remote courses may be a good way to ensure both students and teachers are familiar with it in the future.

The most difficult part of this pandemic has not been the coursework, nor the transition the remote learning, but instead the many unknowns that have faced students and teachers alike. We at Purdue are lucky that our education has been able to continue relatively unabated, and we can be grateful for that fact that most of our instructors have done their best to support us. This coming fall, nearly 500 courses will be offered as online courses, and many others will be presented in hybrid formats. With more time to prepare, courses this fall can be expected to be of higher quality and to have more student-centered contingency plans. As long as it strives for flexibility and gives consideration to students’ evolving needs, the Purdue educational experience will continue to earn its high-quality reputation.

Thank you. Boiler up!

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of remote learning methods: from the covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future.

- 1 Minerva Schools at Keck Graduate Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 2 Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship, Montclair, NJ, United States

- 3 Department of Physics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

This spring, students across the globe transitioned from in-person classes to remote learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented change to undergraduate education saw institutions adopting multiple online teaching modalities and instructional platforms. We sought to understand students’ experiences with and perspectives on those methods of remote instruction in order to inform pedagogical decisions during the current pandemic and in future development of online courses and virtual learning experiences. Our survey gathered quantitative and qualitative data regarding students’ experiences with synchronous and asynchronous methods of remote learning and specific pedagogical techniques associated with each. A total of 4,789 undergraduate participants representing institutions across 95 countries were recruited via Instagram. We find that most students prefer synchronous online classes, and students whose primary mode of remote instruction has been synchronous report being more engaged and motivated. Our qualitative data show that students miss the social aspects of learning on campus, and it is possible that synchronous learning helps to mitigate some feelings of isolation. Students whose synchronous classes include active-learning techniques (which are inherently more social) report significantly higher levels of engagement, motivation, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction. Respondents’ recommendations for changes emphasize increased engagement, interaction, and student participation. We conclude that active-learning methods, which are known to increase motivation, engagement, and learning in traditional classrooms, also have a positive impact in the remote-learning environment. Integrating these elements into online courses will improve the student experience.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the demographics of online students. Previously, almost all students engaged in online learning elected the online format, starting with individual online courses in the mid-1990s through today’s robust online degree and certificate programs. These students prioritize convenience, flexibility and ability to work while studying and are older than traditional college age students ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). These students also find asynchronous elements of a course are more useful than synchronous elements ( Gillingham and Molinari, 2012 ). In contrast, students who chose to take courses in-person prioritize face-to-face instruction and connection with others and skew considerably younger ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ). This leaves open the question of whether students who prefer to learn in-person but are forced to learn remotely will prefer synchronous or asynchronous methods. One study of student preferences following a switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that students enjoy synchronous over asynchronous course elements and find them more effective ( Gillis and Krull, 2020 ). Now that millions of traditional in-person courses have transitioned online, our survey expands the data on student preferences and explores if those preferences align with pedagogical best practices.

An extensive body of research has explored what instructional methods improve student learning outcomes (Fink. 2013). Considerable evidence indicates that active-learning or student-centered approaches result in better learning outcomes than passive-learning or instructor-centered approaches, both in-person and online ( Freeman et al., 2014 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Active-learning approaches include student activities or discussion in class, whereas passive-learning approaches emphasize extensive exposition by the instructor ( Freeman et al., 2014 ). Constructivist learning theories argue that students must be active participants in creating their own learning, and that listening to expert explanations is seldom sufficient to trigger the neurological changes necessary for learning ( Bostock, 1998 ; Zull, 2002 ). Some studies conclude that, while students learn more via active learning, they may report greater perceptions of their learning and greater enjoyment when passive approaches are used ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). We examine student perceptions of remote learning experiences in light of these previous findings.

In this study, we administered a survey focused on student perceptions of remote learning in late May 2020 through the social media account of @unjadedjade to a global population of English speaking undergraduate students representing institutions across 95 countries. We aim to explore how students were being taught, the relationship between pedagogical methods and student perceptions of their experience, and the reasons behind those perceptions. Here we present an initial analysis of the results and share our data set for further inquiry. We find that positive student perceptions correlate with synchronous courses that employ a variety of interactive pedagogical techniques, and that students overwhelmingly suggest behavioral and pedagogical changes that increase social engagement and interaction. We argue that these results support the importance of active learning in an online environment.

Materials and Methods

Participant pool.

Students were recruited through the Instagram account @unjadedjade. This social media platform, run by influencer Jade Bowler, focuses on education, effective study tips, ethical lifestyle, and promotes a positive mindset. For this reason, the audience is presumably academically inclined, and interested in self-improvement. The survey was posted to her account and received 10,563 responses within the first 36 h. Here we analyze the 4,789 of those responses that came from undergraduates. While we did not collect demographic or identifying information, we suspect that women are overrepresented in these data as followers of @unjadedjade are 80% women. A large minority of respondents were from the United Kingdom as Jade Bowler is a British influencer. Specifically, 43.3% of participants attend United Kingdom institutions, followed by 6.7% attending university in the Netherlands, 6.1% in Germany, 5.8% in the United States and 4.2% in Australia. Ninety additional countries are represented in these data (see Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Survey Design

The purpose of this survey is to learn about students’ instructional experiences following the transition to remote learning in the spring of 2020.

This survey was initially created for a student assignment for the undergraduate course Empirical Analysis at Minerva Schools at KGI. That version served as a robust pre-test and allowed for identification of the primary online platforms used, and the four primary modes of learning: synchronous (live) classes, recorded lectures and videos, uploaded or emailed materials, and chat-based communication. We did not adapt any open-ended questions based on the pre-test survey to avoid biasing the results and only corrected language in questions for clarity. We used these data along with an analysis of common practices in online learning to revise the survey. Our revised survey asked students to identify the synchronous and asynchronous pedagogical methods and platforms that they were using for remote learning. Pedagogical methods were drawn from literature assessing active and passive teaching strategies in North American institutions ( Fink, 2013 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Open-ended questions asked students to describe why they preferred certain modes of learning and how they could improve their learning experience. Students also reported on their affective response to learning and participation using a Likert scale.

The revised survey also asked whether students had responded to the earlier survey. No significant differences were found between responses of those answering for the first and second times (data not shown). See Supplementary Appendix 1 for survey questions. Survey data was collected from 5/21/20 to 5/23/20.

Qualitative Coding

We applied a qualitative coding framework adapted from Gale et al. (2013) to analyze student responses to open-ended questions. Four researchers read several hundred responses and noted themes that surfaced. We then developed a list of themes inductively from the survey data and deductively from the literature on pedagogical practice ( Garrison et al., 1999 ; Zull, 2002 ; Fink, 2013 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). The initial codebook was revised collaboratively based on feedback from researchers after coding 20–80 qualitative comments each. Before coding their assigned questions, alignment was examined through coding of 20 additional responses. Researchers aligned in identifying the same major themes. Discrepancies in terms identified were resolved through discussion. Researchers continued to meet weekly to discuss progress and alignment. The majority of responses were coded by a single researcher using the final codebook ( Supplementary Table 1 ). All responses to questions 3 (4,318 responses) and 8 (4,704 responses), and 2,512 of 4,776 responses to question 12 were analyzed. Valence was also indicated where necessary (i.e., positive or negative discussion of terms). This paper focuses on the most prevalent themes from our initial analysis of the qualitative responses. The corresponding author reviewed codes to ensure consistency and accuracy of reported data.

Statistical Analysis

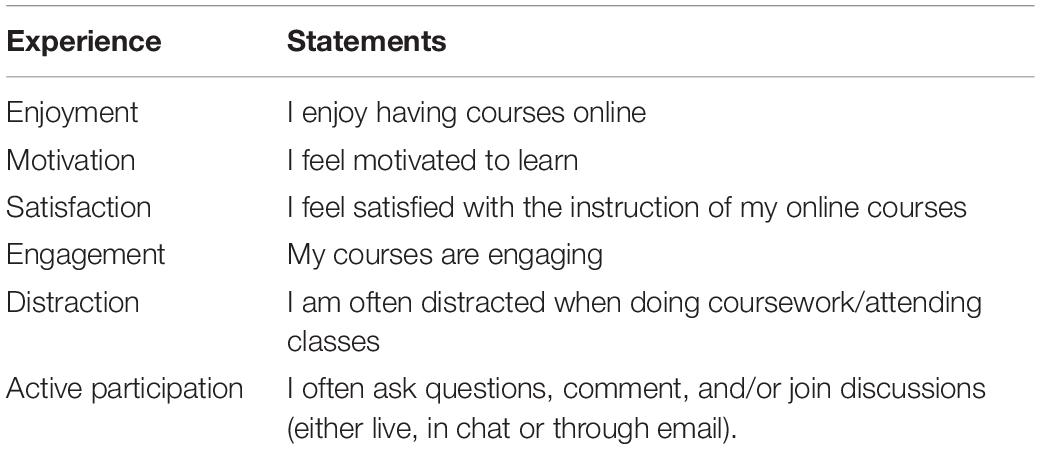

The survey included two sets of Likert-scale questions, one consisting of a set of six statements about students’ perceptions of their experiences following the transition to remote learning ( Table 1 ). For each statement, students indicated their level of agreement with the statement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). The second set asked the students to respond to the same set of statements, but about their retroactive perceptions of their experiences with in-person instruction before the transition to remote learning. This set was not the subject of our analysis but is present in the published survey results. To explore correlations among student responses, we used CrossCat analysis to calculate the probability of dependence between Likert-scale responses ( Mansinghka et al., 2016 ).

Table 1. Likert-scale questions.

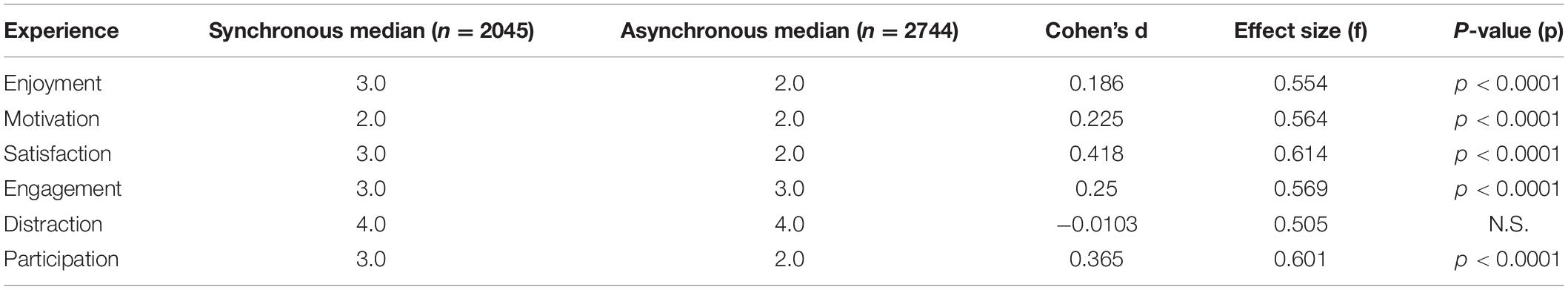

Mean values are calculated based on the numerical scores associated with each response. Measures of statistical significance for comparisons between different subgroups of respondents were calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U -test, and p -values reported here are based on this test statistic. We report effect sizes in pairwise comparisons using the common-language effect size, f , which is the probability that the response from a random sample from subgroup 1 is greater than the response from a random sample from subgroup 2. We also examined the effects of different modes of remote learning and technological platforms using ordinal logistic regression. With the exception of the mean values, all of these analyses treat Likert-scale responses as ordinal-scale, rather than interval-scale data.

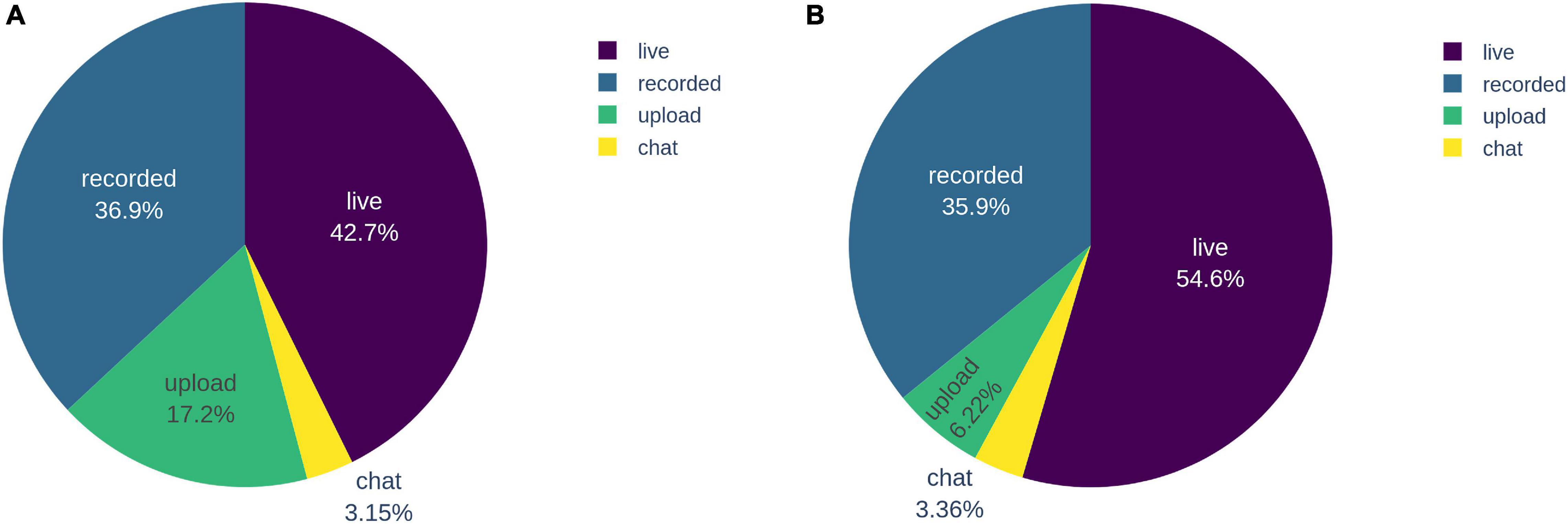

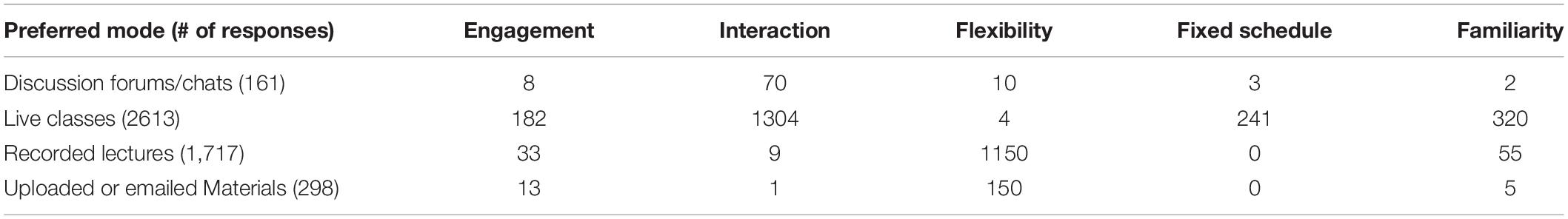

Students Prefer Synchronous Class Sessions

Students were asked to identify their primary mode of learning given four categories of remote course design that emerged from the pilot survey and across literature on online teaching: live (synchronous) classes, recorded lectures and videos, emailed or uploaded materials, and chats and discussion forums. While 42.7% ( n = 2,045) students identified live classes as their primary mode of learning, 54.6% ( n = 2613) students preferred this mode ( Figure 1 ). Both recorded lectures and live classes were preferred over uploaded materials (6.22%, n = 298) and chat (3.36%, n = 161).

Figure 1. Actual (A) and preferred (B) primary modes of learning.

In addition to a preference for live classes, students whose primary mode was synchronous were more likely to enjoy the class, feel motivated and engaged, be satisfied with instruction and report higher levels of participation ( Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 ). Regardless of primary mode, over two-thirds of students reported they are often distracted during remote courses.

Table 2. The effect of synchronous vs. asynchronous primary modes of learning on student perceptions.

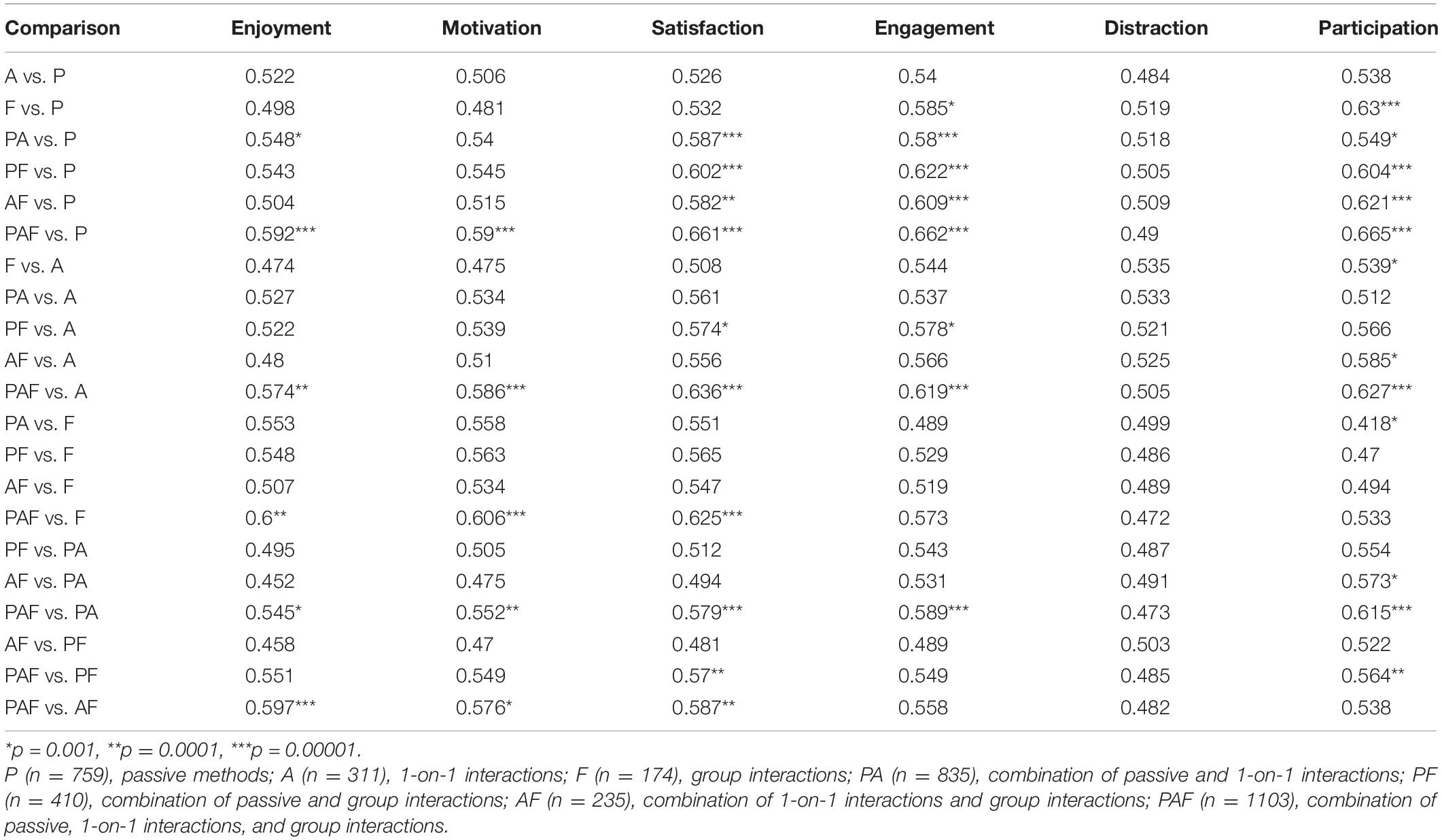

Variation in Pedagogical Techniques for Synchronous Classes Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

To survey the use of passive vs. active instructional methods, students reported the pedagogical techniques used in their live classes. Among the synchronous methods, we identify three different categories ( National Research Council, 2000 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). Passive methods (P) include lectures, presentations, and explanation using diagrams, white boards and/or other media. These methods all rely on instructor delivery rather than student participation. Our next category represents active learning through primarily one-on-one interactions (A). The methods in this group are in-class assessment, question-and-answer (Q&A), and classroom chat. Group interactions (F) included classroom discussions and small-group activities. Given these categories, Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons between the 7 possible combinations and Likert scale responses about student experience showed that the use of a variety of methods resulted in higher ratings of experience vs. the use of a single method whether or not that single method was active or passive ( Table 3 ). Indeed, students whose classes used methods from each category (PAF) had higher ratings of enjoyment, motivation, and satisfaction with instruction than those who only chose any single method ( p < 0.0001) and also rated higher rates of participation and engagement compared to students whose only method was passive (P) or active through one-on-one interactions (A) ( p < 0.00001). Student ratings of distraction were not significantly different for any comparison. Given that sets of Likert responses often appeared significant together in these comparisons, we ran a CrossCat analysis to look at the probability of dependence across Likert responses. Responses have a high probability of dependence on each other, limiting what we can claim about any discrete response ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

Table 3. Comparison of combinations of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

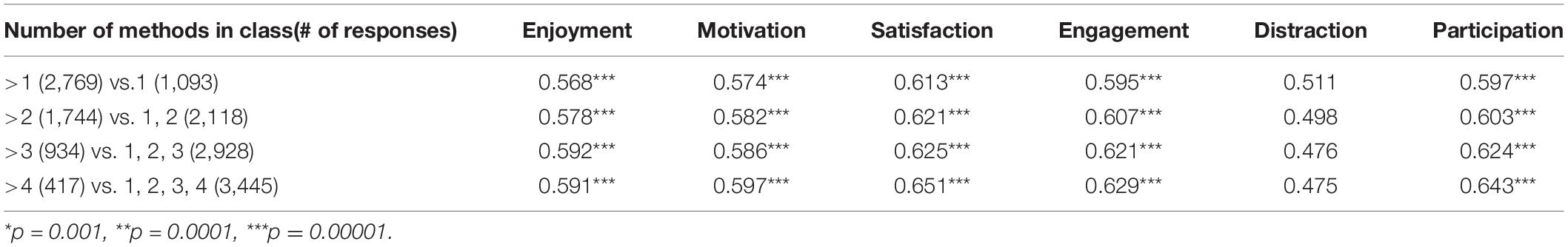

Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons were also used to check if improvement in student experience was associated with the number of methods used vs. the variety of types of methods. For every comparison, we found that more methods resulted in higher scores on all Likert measures except distraction ( Table 4 ). Even comparison between four or fewer methods and greater than four methods resulted in a 59% chance that the latter enjoyed the courses more ( p < 0.00001) and 60% chance that they felt more motivated to learn ( p < 0.00001). Students who selected more than four methods ( n = 417) were also 65.1% ( p < 0.00001), 62.9% ( p < 0.00001) and 64.3% ( p < 0.00001) more satisfied with instruction, engaged, and actively participating, respectfully. Therefore, there was an overlap between how the number and variety of methods influenced students’ experiences. Since the number of techniques per category is 2–3, we cannot fully disentangle the effect of number vs. variety. Pairwise comparisons to look at subsets of data with 2–3 methods from a single group vs. 2–3 methods across groups controlled for this but had low sample numbers in most groups and resulted in no significant findings (data not shown). Therefore, from the data we have in our survey, there seems to be an interdependence between number and variety of methods on students’ learning experiences.

Table 4. Comparison of the number of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

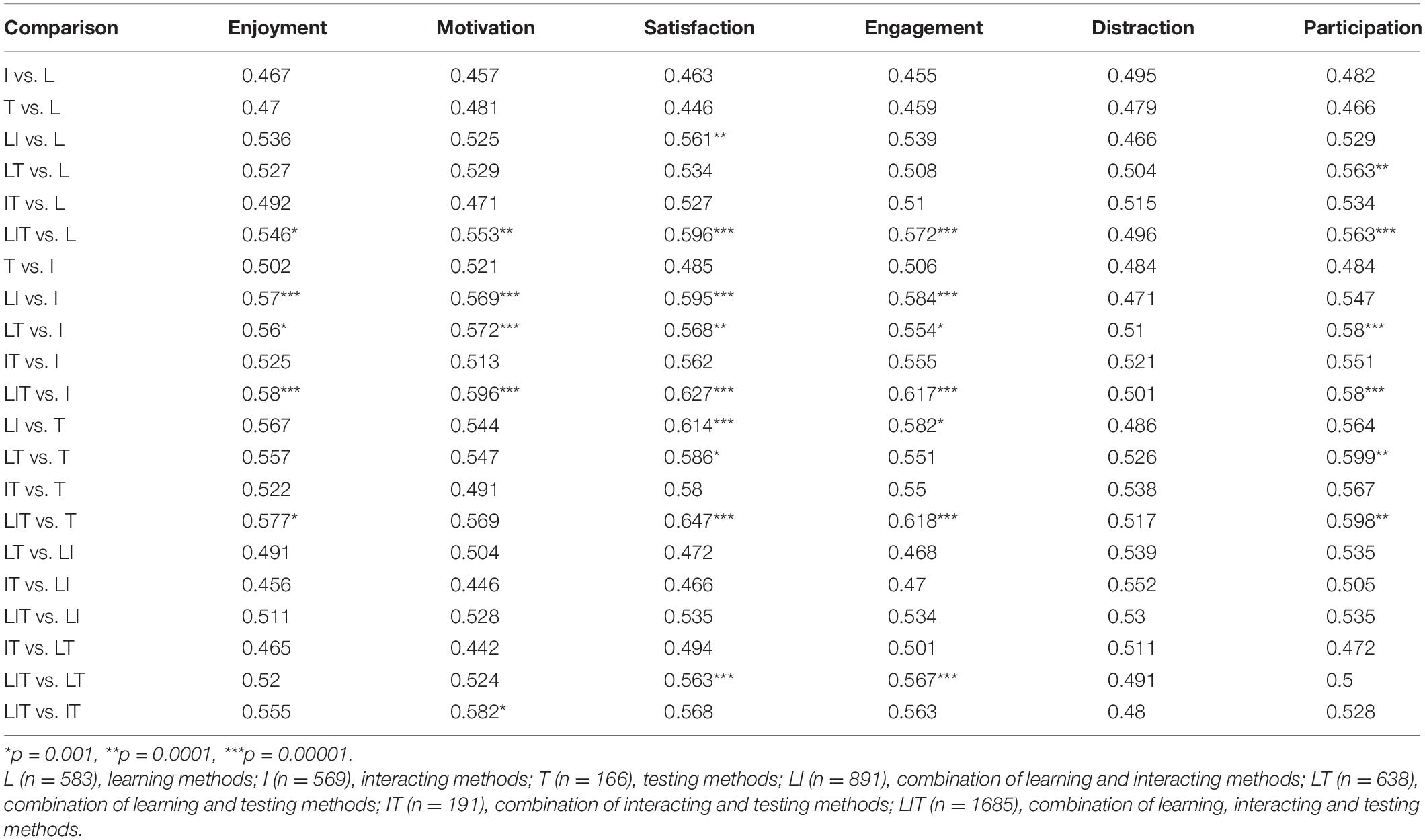

Variation in Asynchronous Pedagogical Techniques Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

Along with synchronous pedagogical methods, students reported the asynchronous methods that were used for their classes. We divided these methods into three main categories and conducted pairwise comparisons. Learning methods include video lectures, video content, and posted study materials. Interacting methods include discussion/chat forums, live office hours, and email Q&A with professors. Testing methods include assignments and exams. Our results again show the importance of variety in students’ perceptions ( Table 5 ). For example, compared to providing learning materials only, providing learning materials, interaction, and testing improved enjoyment ( f = 0.546, p < 0.001), motivation ( f = 0.553, p < 0.0001), satisfaction with instruction ( f = 0.596, p < 0.00001), engagement ( f = 0.572, p < 0.00001) and active participation ( f = 0.563, p < 0.00001) (row 6). Similarly, compared to just being interactive with conversations, the combination of all three methods improved five out of six indicators, except for distraction in class (row 11).

Table 5. Comparison of combinations of asynchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood that the platforms students used predicted student perceptions ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Platform choices were based on the answers to open-ended questions in the pre-test survey. The synchronous and asynchronous methods used were consistently more predictive of Likert responses than the specific platforms. Likewise, distraction continued to be our outlier with no differences across methods or platforms.

Students Prefer In-Person and Synchronous Online Learning Largely Due to Social-Emotional Reasoning

As expected, 86.1% (4,123) of survey participants report a preference for in-person courses, while 13.9% (666) prefer online courses. When asked to explain the reasons for their preference, students who prefer in-person courses most often mention the importance of social interaction (693 mentions), engagement (639 mentions), and motivation (440 mentions). These students are also more likely to mention a preference for a fixed schedule (185 mentions) vs. a flexible schedule (2 mentions).

In addition to identifying social reasons for their preference for in-person learning, students’ suggestions for improvements in online learning focus primarily on increasing interaction and engagement, with 845 mentions of live classes, 685 mentions of interaction, 126 calls for increased participation and calls for changes related to these topics such as, “Smaller teaching groups for live sessions so that everyone is encouraged to talk as some people don’t say anything and don’t participate in group work,” and “Make it less of the professor reading the pdf that was given to us and more interaction.”

Students who prefer online learning primarily identify independence and flexibility (214 mentions) and reasons related to anxiety and discomfort in in-person settings (41 mentions). Anxiety was only mentioned 12 times in the much larger group that prefers in-person learning.

The preference for synchronous vs. asynchronous modes of learning follows similar trends ( Table 6 ). Students who prefer live classes mention engagement and interaction most often while those who prefer recorded lectures mention flexibility.

Table 6. Most prevalent themes for students based on their preferred mode of remote learning.

Student Perceptions Align With Research on Active Learning

The first, and most robust, conclusion is that incorporation of active-learning methods correlates with more positive student perceptions of affect and engagement. We can see this clearly in the substantial differences on a number of measures, where students whose classes used only passive-learning techniques reported lower levels of engagement, satisfaction, participation, and motivation when compared with students whose classes incorporated at least some active-learning elements. This result is consistent with prior research on the value of active learning ( Freeman et al., 2014 ).

Though research shows that student learning improves in active learning classes, on campus, student perceptions of their learning, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction are often lower in active-learning courses ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). Our finding that students rate enjoyment and satisfaction with instruction higher for active learning online suggests that the preference for passive lectures on campus relies on elements outside of the lecture itself. That might include the lecture hall environment, the social physical presence of peers, or normalization of passive lectures as the expected mode for on-campus classes. This implies that there may be more buy-in for active learning online vs. in-person.

A second result from our survey is that student perceptions of affect and engagement are associated with students experiencing a greater diversity of learning modalities. We see this in two different results. First, in addition to the fact that classes that include active learning outperform classes that rely solely on passive methods, we find that on all measures besides distraction, the highest student ratings are associated with a combination of active and passive methods. Second, we find that these higher scores are associated with classes that make use of a larger number of different methods.

This second result suggests that students benefit from classes that make use of multiple different techniques, possibly invoking a combination of passive and active methods. However, it is unclear from our data whether this effect is associated specifically with combining active and passive methods, or if it is associated simply with the use of multiple different methods, irrespective of whether those methods are active, passive, or some combination. The problem is that the number of methods used is confounded with the diversity of methods (e.g., it is impossible for a classroom using only one method to use both active and passive methods). In an attempt to address this question, we looked separately at the effect of number and diversity of methods while holding the other constant. Across a large number of such comparisons, we found few statistically significant differences, which may be a consequence of the fact that each comparison focused on a small subset of the data.

Thus, our data suggests that using a greater diversity of learning methods in the classroom may lead to better student outcomes. This is supported by research on student attention span which suggests varying delivery after 10–15 min to retain student’s attention ( Bradbury, 2016 ). It is likely that this is more relevant for online learning where students report high levels of distraction across methods, modalities, and platforms. Given that number and variety are key, and there are few passive learning methods, we can assume that some combination of methods that includes active learning improves student experience. However, it is not clear whether we should predict that this benefit would come simply from increasing the number of different methods used, or if there are benefits specific to combining particular methods. Disentangling these effects would be an interesting avenue for future research.

Students Value Social Presence in Remote Learning

Student responses across our open-ended survey questions show a striking difference in reasons for their preferences compared with traditional online learners who prefer flexibility ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). Students reasons for preferring in-person classes and synchronous remote classes emphasize the desire for social interaction and echo the research on the importance of social presence for learning in online courses.

Short et al. (1976) outlined Social Presence Theory in depicting students’ perceptions of each other as real in different means of telecommunications. These ideas translate directly to questions surrounding online education and pedagogy in regards to educational design in networked learning where connection across learners and instructors improves learning outcomes especially with “Human-Human interaction” ( Goodyear, 2002 , 2005 ; Tu, 2002 ). These ideas play heavily into asynchronous vs. synchronous learning, where Tu reports students having positive responses to both synchronous “real-time discussion in pleasantness, responsiveness and comfort with familiar topics” and real-time discussions edging out asynchronous computer-mediated communications in immediate replies and responsiveness. Tu’s research indicates that students perceive more interaction with synchronous mediums such as discussions because of immediacy which enhances social presence and support the use of active learning techniques ( Gunawardena, 1995 ; Tu, 2002 ). Thus, verbal immediacy and communities with face-to-face interactions, such as those in synchronous learning classrooms, lessen the psychological distance of communicators online and can simultaneously improve instructional satisfaction and reported learning ( Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997 ; Richardson and Swan, 2019 ; Shea et al., 2019 ). While synchronous learning may not be ideal for traditional online students and a subset of our participants, this research suggests that non-traditional online learners are more likely to appreciate the value of social presence.

Social presence also connects to the importance of social connections in learning. Too often, current systems of education emphasize course content in narrow ways that fail to embrace the full humanity of students and instructors ( Gay, 2000 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic leading to further social isolation for many students, the importance of social presence in courses, including live interactions that build social connections with classmates and with instructors, may be increased.

Limitations of These Data

Our undergraduate data consisted of 4,789 responses from 95 different countries, an unprecedented global scale for research on online learning. However, since respondents were followers of @unjadedjade who focuses on learning and wellness, these respondents may not represent the average student. Biases in survey responses are often limited by their recruitment techniques and our bias likely resulted in more robust and thoughtful responses to free-response questions and may have influenced the preference for synchronous classes. It is unlikely that it changed students reporting on remote learning pedagogical methods since those are out of student control.

Though we surveyed a global population, our design was rooted in literature assessing pedagogy in North American institutions. Therefore, our survey may not represent a global array of teaching practices.

This survey was sent out during the initial phase of emergency remote learning for most countries. This has two important implications. First, perceptions of remote learning may be clouded by complications of the pandemic which has increased social, mental, and financial stresses globally. Future research could disaggregate the impact of the pandemic from students’ learning experiences with a more detailed and holistic analysis of the impact of the pandemic on students.

Second, instructors, students and institutions were not able to fully prepare for effective remote education in terms of infrastructure, mentality, curriculum building, and pedagogy. Therefore, student experiences reflect this emergency transition. Single-modality courses may correlate with instructors who lacked the resources or time to learn or integrate more than one modality. Regardless, the main insights of this research align well with the science of teaching and learning and can be used to inform both education during future emergencies and course development for online programs that wish to attract traditional college students.

Global Student Voices Improve Our Understanding of the Experience of Emergency Remote Learning

Our survey shows that global student perspectives on remote learning agree with pedagogical best practices, breaking with the often-found negative reactions of students to these practices in traditional classrooms ( Shekhar et al., 2020 ). Our analysis of open-ended questions and preferences show that a majority of students prefer pedagogical approaches that promote both active learning and social interaction. These results can serve as a guide to instructors as they design online classes, especially for students whose first choice may be in-person learning. Indeed, with the near ubiquitous adoption of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote learning may be the default for colleges during temporary emergencies. This has already been used at the K-12 level as snow days become virtual learning days ( Aspergren, 2020 ).

In addition to informing pedagogical decisions, the results of this survey can be used to inform future research. Although we survey a global population, our recruitment method selected for students who are English speakers, likely majority female, and have an interest in self-improvement. Repeating this study with a more diverse and representative sample of university students could improve the generalizability of our findings. While the use of a variety of pedagogical methods is better than a single method, more research is needed to determine what the optimal combinations and implementations are for courses in different disciplines. Though we identified social presence as the major trend in student responses, the over 12,000 open-ended responses from students could be analyzed in greater detail to gain a more nuanced understanding of student preferences and suggestions for improvement. Likewise, outliers could shed light on the diversity of student perspectives that we may encounter in our own classrooms. Beyond this, our findings can inform research that collects demographic data and/or measures learning outcomes to understand the impact of remote learning on different populations.

Importantly, this paper focuses on a subset of responses from the full data set which includes 10,563 students from secondary school, undergraduate, graduate, or professional school and additional questions about in-person learning. Our full data set is available here for anyone to download for continued exploration: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId= doi: 10.7910/DVN/2TGOPH .

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GS: project lead, survey design, qualitative coding, writing, review, and editing. TN: data analysis, writing, review, and editing. CN and PB: qualitative coding. JW: data analysis, writing, and editing. CS: writing, review, and editing. EV and KL: original survey design and qualitative coding. PP: data analysis. JB: original survey design and survey distribution. HH: data analysis. MP: writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Minerva Schools at KGI for providing funding for summer undergraduate research internships. We also want to thank Josh Fost and Christopher V. H.-H. Chen for discussion that helped shape this project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full#supplementary-material

Aspergren, E. (2020). Snow Days Canceled Because of COVID-19 Online School? Not in These School Districts.sec. Education. USA Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/12/15/covid-school-canceled-snow-day-online-learning/3905780001/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Google Scholar

Bostock, S. J. (1998). Constructivism in mass higher education: a case study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 29, 225–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00066

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bradbury, N. A. (2016). Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 509–513. doi: 10.1152/advan.00109.2016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, B., Bastedo, K., and Howard, W. (2018). Exploring best practices for online STEM courses: active learning, interaction & assessment design. Online Learn. 22, 59–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i2.1369

Davis, D., Chen, G., Hauff, C., and Houben, G.-J. (2018). Activating learning at scale: a review of innovations in online learning strategies. Comput. Educ. 125, 327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.019

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Multicultural Education Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillingham, and Molinari, C. (2012). Online courses: student preferences survey. Internet Learn. 1, 36–45. doi: 10.18278/il.1.1.4

Gillis, A., and Krull, L. M. (2020). COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teach. Sociol. 48, 283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263

Goodyear, P. (2002). “Psychological foundations for networked learning,” in Networked Learning: Perspectives and Issues. Computer Supported Cooperative Work , eds C. Steeples and C. Jones (London: Springer), 49–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0181-9_4

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 21, 82–101. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1344

Gunawardena, C. N. (1995). Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int. J. Educ. Telecommun. 1, 147–166.

Gunawardena, C. N., and Zittle, F. J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. Am. J. Distance Educ. 11, 8–26. doi: 10.1080/08923649709526970

Harris, H. S., and Martin, E. (2012). Student motivations for choosing online classes. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060211

Levitz, R. N. (2016). 2015-16 National Online Learners Satisfaction and Priorities Report. Cedar Rapids: Ruffalo Noel Levitz, 12.

Mansinghka, V., Shafto, P., Jonas, E., Petschulat, C., Gasner, M., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2016). CrossCat: a fully Bayesian nonparametric method for analyzing heterogeneous, high dimensional data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–49. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69765-9_7

National Research Council (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, doi: 10.17226/9853

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2019). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Online Learn. 7, 68–88. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

Shea, P., Pickett, A. M., and Pelz, W. E. (2019). A Follow-up investigation of ‘teaching presence’ in the suny learning network. Online Learn. 7, 73–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i2.1856

Shekhar, P., Borrego, M., DeMonbrun, M., Finelli, C., Crockett, C., and Nguyen, K. (2020). Negative student response to active learning in STEM classrooms: a systematic review of underlying reasons. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 49, 45–54.

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Tu, C.-H. (2002). The measurement of social presence in an online learning environment. Int. J. E Learn. 1, 34–45. doi: 10.17471/2499-4324/421

Zull, J. E. (2002). The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning , 1st Edn. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Keywords : online learning, COVID-19, active learning, higher education, pedagogy, survey, international

Citation: Nguyen T, Netto CLM, Wilkins JF, Bröker P, Vargas EE, Sealfon CD, Puthipiroj P, Li KS, Bowler JE, Hinson HR, Pujar M and Stein GM (2021) Insights Into Students’ Experiences and Perceptions of Remote Learning Methods: From the COVID-19 Pandemic to Best Practice for the Future. Front. Educ. 6:647986. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.647986

Received: 30 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021; Published: 09 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Nguyen, Netto, Wilkins, Bröker, Vargas, Sealfon, Puthipiroj, Li, Bowler, Hinson, Pujar and Stein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geneva M. Stein, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Covid-19 and Beyond: From (Forced) Remote Teaching and Learning to ‘The New Normal’ in Higher Education

What the Covid-19 Pandemic Revealed About Remote School

The unplanned experiment provided clear lessons on the value—and limitations—of online learning. Are educators listening?

Katherine Reynolds Lewis, Undark Magazine

:focal(512x344:513x345)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/d6/03d60640-f6dd-4840-984d-22d3f18f1d73/gettyimages-1282746597.jpg)

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. While there were some bright spots across the country, the transition was messy and uneven — countless teachers had neither the materials nor training they needed to effectively connect with students remotely, while many of those students were bored , isolated, and lacked the resources they needed to learn. The results were abysmal: low test scores, fewer children learning at grade level, increased inequity, and teacher burnout. With the public health crisis on top of deaths and job losses in many families, students experienced increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Yet society very well may face new widespread calamities in the near future, from another pandemic to extreme weather, that will require a similarly quick shift to remote school. Success will hinge on big changes, from infrastructure to teacher training, several experts told Undark. “We absolutely need to invest in ways for schools to run continuously, to pick up where they left off. But man, it’s a tall order,” said Heather L. Schwartz, a senior policy researcher at RAND. “It’s not good enough for teachers to simply refer students to disconnected, stand-alone videos on, say, YouTube. Students need lessons that connect directly to what they were learning before school closed.”

More than three years after U.S. schools shifted to remote instruction on an emergency basis, the education sector is still largely unprepared for another long-term interruption of in-person school. The stakes are highest for those who need it most: low-income children and students of color, who are also most likely to be harmed in a future pandemic or live in communities most affected by climate change. But, given the abundance of research on what didn’t work during the pandemic, school leaders may have the opportunity to do things differently next time. Being ready would require strategic planning, rethinking the role of the teacher, and using new technology wisely, experts told Undark. And many problems with remote learning actually trace back not to technology, but to basic instructional quality. Effective remote learning won’t happen if schools aren’t already employing best practices in the physical classroom, such as creating a culture of learning from mistakes, empowering teachers to meet individual student needs, establishing high expectations, and setting clear goals supported by frequent feedback. While it’s ambitious to envision that every school district will create seamless virtual learning platforms — and, for that matter, overcome challenges in education more broadly — the lessons of the pandemic are there to be followed or ignored.

“We haven’t done anywhere near the amount of planning or the development of the instructional infrastructure needed to allow for a smooth transition next time schools need to close for prolonged periods of time,” Schwartz said. “Until we can reach that goal, I don’t have high confidence that the next prolonged school closure will be substantially more successful.”

Before the pandemic, only 3 percent of U.S. school districts offered virtual school, mostly for students with unique circumstances, such as a disability or those intensely pursuing a sport or the performing arts, according to a RAND survey Schwartz co-authored. For the most part, the educational technology companies and developers creating software for these schools promised to give students a personalized experience. But the research on these programs, which focused on virtual charter schools that only existed online, showed poor outcomes . Their students were a year behind in math and nearly a half-year behind in reading, and courses offered less direct time with a teacher each week than regular schools have in a day.

The pandemic sparked growth in stand-alone virtual academies, in addition to the emergency remote learning that districts had to adopt in March 2020. Educators’ interest in online instructional materials exploded, too, according to Schwartz, “and it really put the foot on the gas to ramp them up, expand them, and in theory, improve them.” By June 2021, the number of school districts with a stand-alone virtual school rose to 26 percent. Of the remaining districts, another 23 percent were interested in offering an online school, the report found.

But the sheer magnitude of options for online learning didn’t necessarily mean it worked well, Schwartz said: “It’s the quality part that has to come up in order for this to be a really good, viable alternative to in person instruction.” And individualized, self-directed online learning proved to be a pipe dream — especially for younger children who needed support from a parent or other family member even to get online, much less stay focused.

“The notion that students would have personalized playlists and could curate their own education was proven to be problematic on a couple levels, especially for younger and less affluent students,” said Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “The social and emotional toll that isolation and those traumas took on students suggest that the social dimension of schooling is hugely important and was greatly undervalued, especially by proponents for an increased role of technology.”

Students also often didn’t have the materials they needed for online school, some lacking computers or internet access at home. Teachers didn’t have the right training for online instruction , which has a unique pedagogy and best practices. As a result, many virtual classrooms attempted to replicate the same lessons over video that would’ve been delivered at school. The results were overwhelmingly bad, research shows. For example, a 2022 study found six consistent themes about how the pandemic affected learning, including a lack of interaction between students and with teachers, and disproportionate harm to low-income students. Numb from isolation and too many hours in front of a screen, students failed to engage in coursework and suffered emotionally .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/e1/05e16ea9-bd7f-4fbf-846e-177f05272f72/gettyimages-1229757662.jpg)

After some districts resumed in-person or hybrid instruction in the 2020 fall semester, it became clear that the longer students were remote, the worse their learning delays . For example, national standardized test scores for the 2020-2021 school year showed that passing rates for math declined about 14 percentage points on average, more than three times the drop seen in districts that returned to in-person instruction the earliest, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study . Even after most U.S. districts resumed in-person instruction, students who had been online the longest continued to lag behind their peers. The pandemic hit cities hardest and the effects disproportionately harmed low-income children and students of color in urban areas.

“What we did during the pandemic is not the optimal use of online learning in education for the future,” said Ashley Jochim, a researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “Online learning is not a full stop substitute for what kids need to thrive and be supported at school.”

Children also largely prefer in-person school. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey suggested that 65 percent of students would rather be in a classroom, 9 percent would opt for online only, and the rest are unsure or prefer a hybrid model. “For most families and kids, full-time online school is actually not the educational solution they want,” Jochim said.

Virtual school felt meaningless to Abner Magdaleno, a 12th grader in Los Angeles. “I couldn’t really connect with it, because I’m more of, like, a social person. And that was stripped away from me when we went online,” recalled Magdaleno. Mackenzie Sheehy, 19, of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, found there were too many distractions at home to learn. Her grades suffered, and she missed the one-on-one time with teachers. (Sheehy graduated from high school in 2022.)

Many teachers feel the same way. “Nothing replaces physical proximity, whatever the age,” said Ana Silva, a New York City English teacher. She enjoyed experimenting with interactive technology during online school, but is grateful to be back in person. “I like the casual way kids can come to my desk and see me. I like the dynamism — seeing kids in the cafeteria. Those interactions are really positive, and they were entirely missing during the online learning.”

During the 2022-2023 school year, many districts initially planned to continue online courses for snow days and other building closures. But they found that the teacher instruction, student experience, and demands on families were simply too different for in-person versus remote school, said Liz Kolb, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. “Schools are moving away from that because it’s too difficult to quickly transition and blend back and forth among the two without having strong structures in place,” Kolb said. “Most schools don’t have those strong structures.”

In addition, both families and educators grew sick of their screens. “They’re trying to avoid technology a little bit. There’s this fatigue coming out of remote learning and the pandemic,” said Mingyu Feng, a research director at WestEd, a nonprofit research agency. “If the students are on Zoom every day for like, six hours, that seems to be not quite right.”

Despite the bumpy pandemic rollout, online school can serve an important role in the U.S. education system. For one, online learning is a better alternative for some students. Garvey Mortley, 15, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her two sisters all switched to their district’s virtual academy during the pandemic to protect their own health and their grandmother’s. This year, Mortley’s sisters went back to in-person school, but she chose to stay online. “I love the flexibility about it,” she said, noting that some of her classmates prefer it because they have a disability or have demanding schedules. “I love how I can just roll out of bed in the morning, and I can sit down and do school.” Some educators also prefer teaching online, according to reports of virtual schools that were inundated with applications from teachers because they wanted to keep working from home . Silva, the New York high school English teacher, enjoys online tutoring and academic coaching, because it facilitates one-on-one interaction.

And in rural districts and those with low enrollment, some access to online learning ensures students can take courses that could otherwise be inaccessible. “Because of the economies of scale in small rural districts, they needed to tap into online and shared service delivery arrangements in order to provide a full complement of coursework at the high school level,” said Jochim. Innovation in these districts, she added, will accelerate: “We’ll continue to see growth, scalability, and improvement in quality.”

There were also some schools that were largely successful at switching to online at the start of the pandemic, such as Vista Unified School District in California, which pooled and shared innovative ideas for adapting in March 2020; the school quickly put together an online portal so that principals and teachers could share ideas and the district could allot the necessary resources. Digging into examples like this could point the way to the future of online learning, said Chelsea Waite, a senior researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who was part of a collaborative project studying 70 schools and districts that pivoted successfully to online learning. The project found three factors that made the transition work: a focus on resilience, collaboration, and autonomy for both students and educators; a healthy culture that prioritized relationships; and strong yet flexible systems that were accustomed to adaptation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/64/606453dd-d157-45da-a865-5161f95b6f08/gettyimages-1228656332.jpg)

“We investigated schools that did seem to be more prepared for the Covid disruption, not just with having devices in students’ hands or having an online curriculum already, but with a learning culture in the school that really prioritized agency and problem solving as skills for students and adults,” Waite said. “In these schools, kids are learning from a very young age to be a little bit more self-directed, to set goals, and pursue them and pivot when they need to.”

Similarly, many of the takeaways from the pandemic trace back to the basics of effective education, not technological innovation. A landmark report by the National Academies of Sciences called “How People Learn,” most recently updated in 2018, synthesized the body of educational research and identified four key features in the most successful learning environments. First, these schools are designed for, and adapt to, the specific students, building on what they bring to the classroom, such as skills and beliefs. Second, successful schools give their students clear goals, showing them what they need to learn and how they can get there. Third, they provide in-the-moment feedback that emphasizes understanding, not memorization. And finally, the most successful schools are community-centered, with a culture of collaboration and acceptance of mistakes.

“We as humans are social learners, yet some of the tech talk is driven by people who are strong individual learners,” said Jeremy Roschelle, executive director of Learning Sciences Research at Digital Promise, a global education nonprofit. “They’re not necessarily thinking about how most people learn, which is very social.”

Another powerful insight from pandemic-era remote schooling involves the evolving role of teachers, said Kim Kelly, a middle school math teacher at Northbridge Middle School in Massachusetts and a K-8 curriculum coach. Historically, a teacher’s role is the keeper of knowledge who delivers instruction. But in recent years, there has been a shift in approach, where teachers think of themselves as coaches who can intervene based on a student’s individual learning progress. Technology that assists with a coach-like role can be effective — but requires educators to be trained and comfortable interpreting data on student needs.

For example, with a digital learning platform called ASSISTments, teachers can assign math problems, students complete them — potentially receiving in-the-moment feedback on steps they’re getting wrong — and then the teachers can use data from individual students and the entire class to plan instruction and see where additional support is needed.

“A big advantage of these computer-driven products is they really try to diagnose where students are, and try to address their needs. It’s very personalized, individualized,” said WestEd’s Feng, who has evaluated ASSISTments and other educational technologies. She noted that some teachers feel frustrated “when you expect them to read the data and try to figure out what the students’ needs are.”

Teacher’s colleges don’t typically prepare educators to interpret data and change their practices, said Kelly, whose dissertation focused on self-regulated online learning. But professional development has helped her learn to harness technology to improve teaching and learning. “Schools are in data overload; we are oozing data from every direction, yet none of it is very actionable,” she said. Some technology, she added, provided student data that she could use regularly, which changed how she taught and assigned homework.

When students get feedback from the computer program during a homework session, the whole class doesn’t have to review the homework together, which can save time. Educators can move forward on instruction — or if they see areas of confusion, focus more on those topics. The ability of the programs to detect how well students are learning “is unreal,” said Kelly, “but it really does require teachers to be monitoring that data and interpreting.” She learned to accept that some students could drive their own learning and act on the feedback from homework, while others simply needed more teacher intervention. She now does more assessment at the beginning of a course to better support all students.

At the district or even national level, letting teachers play to their strengths can also help improve how their students learn, Toch, of FutureEd, said. For example, if a teacher is better at delivering instruction, they could give a lesson to a larger group of students online, while another teacher who is more comfortable in the coach role could work in smaller groups or one-on-one.

“One thing we saw during the pandemic are smart strategies for using technology to get outstanding teachers in front of more students,” Toch said, describing one effort that recruited exceptional teachers nationally and built a strong curriculum to be delivered online. “The local educators were providing support for their students in their classrooms.”

Remote schooling requires new technology, and already, educators are swamped with competing platforms and software choices — most of which have insufficient evidence of efficacy . Traditional independent research on specific technologies is sparse, Roschelle said. Post-pandemic, the field is so diverse and there are so many technologies in use, it’s almost impossible to find a control group to design a randomized control trial, he added. However, there is qualitative research and evidence that give hints about the quality of technology and online learning, such as case studies and school recommendations.

Educational leaders should ask three key questions about technology before investing, recommended Ryan Baker, a professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania: Is there evidence it works to improve learning outcomes? Does the vendor provide support and training, or are teachers on their own? And does it work with the same types of students as are in their school or district? In other words, educators must look at a technology’s track record in the context of their own school’s demographics, geography, culture, and challenges. These decisions are complicated by the small universe of researchers and evaluators, who have many overlapping relationships. (Over his career, for example, Baker has worked with or consulted for many of the education technology firms that create the software he studies.)

It may help to broaden the definition of evidence. The Center on Reinventing Public Education launched the Canopy project to collect examples of effective educational innovation around the U.S.

“What we wanted to do is build much better and more open and collective knowledge about where schools are challenging old assumptions and redesigning what school is and should be,” she added, noting that these educational leaders are reconceptualizing the skills they want students to attain. “They’re often trying to measure or communicate concepts that we don’t have great measurement tools for yet. So they end up relying on a lot of testimonials and evidence of student work.”

The moment is ripe for innovation in online and in-person education, said Julia Fallon, executive director of the State Educational Technology Directors Association, since the pandemic accelerated the rollout of devices and needed infrastructure. There’s an opportunity and need for technology that empowers teachers to improve learning outcomes and work more efficiently, said Roschelle. Online and hybrid learning are clearly here to stay — and likely will be called upon again during future temporary school closures.

Still, poorly-executed remote learning risks tainting the whole model; parents and students may be unlikely to give it a second chance. The pandemic showed the hard and fast limits on the potential for fully remote learning to be adopted broadly, for one, because in many communities, schools serve more than an educational function — they support children’s mental health, social needs, and nutrition and other physical health needs. The pandemic also highlighted the real challenge in training the entire U.S. teaching corps to be proficient in technology and data analysis. And the lack of a nimble shift to remote learning in an emergency will disproportionately harm low-income children and students of color. So the stakes are high for getting it right, experts told Undark, and summoning the political will.

“There are these benefits in online education, but there are also these real weaknesses we know from prior research and experience,” Jochim said. “So how do we build a system that has online learning as a complement to this other set of supports and experiences that kids benefit from?”

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning journalist covering children, race, gender, disability, mental health, social justice, and science.

This article was originally published on Undark . Read the original article .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Why Are We Turning Our Backs on Remote Learning?

- Share article

Remote learning has moved to the top of the school agenda with a vengeance since March of last year. Without it, tens of millions of American students would have been without formal instruction during the pandemic. It’s a big topic moving forward as we think about what schools will look like come September.

A few policymakers are big fans. Take, for example, Eric Adams, one of the front-runners in the race to become New York City’s newest mayor. This February, the former policeman opined at a meeting of the Citizens Budget Commission, “If you do a full-year school year by using the new technology of remote learning, you don’t need children to be in a school building with a number of teachers. It’s just the opposite. You could have one great teacher that’s in one of our specialized high schools to teach three to 400 students.”

But Adams and those who share his view are pushing upstream against a growing consensus that remote learning contributes to “learning loss” and to teacher burnout, while being detrimental to student learning. Increasingly, school districts, as well as state leaders and elected officials, lean toward eliminating remote learning as an educational option for students come September—the current New York City mayor, Bill de Blasio, among them.

Extreme pro- and anti-positions are misbegotten. Advocates need to take care. Ham-fisted mandates banning or requiring remote learning are likely to throw the baby out with the bath water.

This entire discussion lacks the proper consideration of the overall benefits and drawbacks of remote learning.

Remote learning has been used in educational settings for many years. There are traditional and virtual schools across the country that do amazing work with their students in fully virtual and hybrid settings. There are also, to be clear, fly-by-night e-operators consuming public dollars with very little public benefit to show for it.

But why are people so interested in removing or banning remote learning from the options we can offer students? Like so many things these days, remote learning feels like a politically charged topic. That’s an unfortunate reality given the benefits that some students find in remote settings.

Without remote learning this past year, schooling options for students in Joliet Public Schools District 86—which I lead—would have been embarrassingly threadbare. We were largely fully remote for most of the year. We were not fully one-to-one with our devices when the pandemic first shut down schools in March 2020. However, by the middle of May that same year, nearly every student had a device for instruction. The remaining students were provided a device in time to start the 2020-21 school year in August.

We remained fully remote at the beginning of the school year based on our local COVID-19 realities. As we monitored the data, it was necessary for us to remain fully remote until February. We invited small groups of special education students to return to their school buildings one or two days each week. However, many parents declined this opportunity. We invited groups of general education students to return to their school buildings one or two days each week in March. Only about 15 percent of our total student population participated in person, while the remainder continued fully remote. By the end of the year, we had increased our percentage of in-person students to approximately 25 percent.

Mandated in-person state assessments also added to the dilemma of planning for instruction in the spring. Thirty-five percent of our English-language learners participated in their mandated assessment, and approximately 42 percent of students in grades 3-8 participated in the state-mandated assessments. Unfortunately, the time spent ensuring mandated assessments were managed and monitored appropriately took time away from instruction—for students attending in-person and those still fully remote.

Was everyone successful in our fully virtual learning environment? No. Some students thrived while others struggled. As an educator, I realize that not every instructional model or strategy works for every student. Therefore, I want options in my toolbox so that I can assist students to be successful.

As a district superintendent, it is essential that I have options to offer families that help place their children in the best learning environments for them. Allowing parents a choice among fully online, hybrid, and in-person learning is the right thing to do as we move into a postpandemic world. Why would we go backward when we can augment our options for students to better ensure their success?

We’ve doubtless made mistakes, but using these experiences as a lever for change offers a strategic way forward.

There have been several lessons learned during the past terrible 16 months. The public’s eyes have been opened about how difficult it is to provide a quality education to diverse student populations. We’ve gained some hard-won insights into the challenges and benefits associated with different approaches to helping students succeed. We’ve doubtless made mistakes, but using these experiences as a lever for change offers a strategic way forward.

Let’s be honest. As Gloria Ladson-Billings, a retired tenured faculty member at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a former president of the American Educational Research Association, likes to point out, we don’t really want to return to normal because “normal is the place where the problems were.” We need a new vision that offers parents and students new options. Returning to traditional school settings that look exactly the way they were before would be a waste of everything we’ve learned since COVID-19 shut our school buildings down.

It is time for school leaders to stand up and insist that we cannot let the system revert to the status quo ante. It is time for us to stand up for our students and their families by providing them with as many options as we can so that they can be as successful as they want to be and we want them to be. It is time, too, that we stand up for our staff by providing them with all the resources needed to meet the needs of their students.