Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Characteristics of An Abstract

- One paragraph of text, typically 200-300 words long.

- A summary of the entire poster.

- Organized into four distinct sections that appear in order: Introduction, Materials & Methods, Results, Discussion.

- Each section typically consists of 2-4 sentences.

- No tables and no figures.

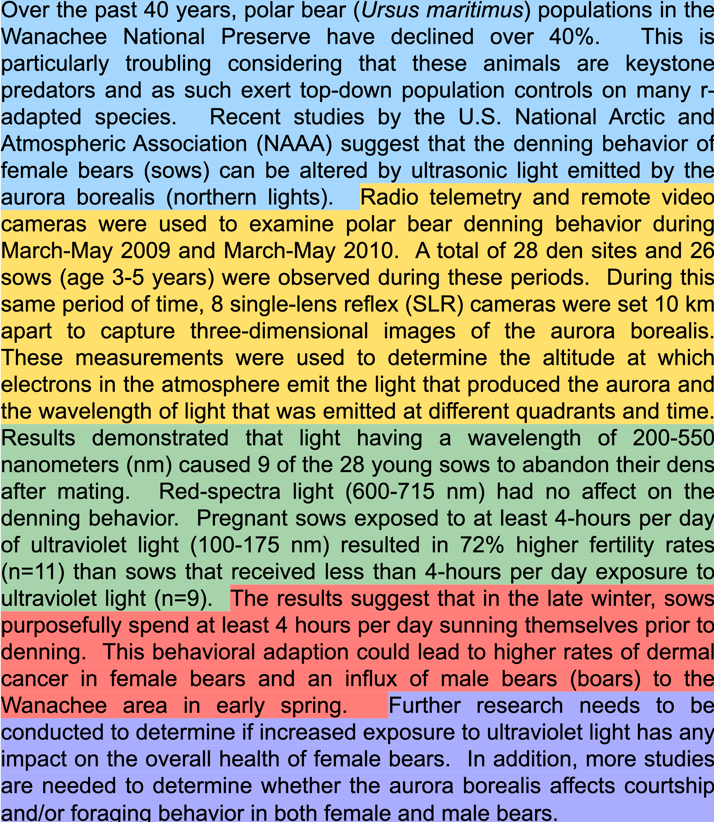

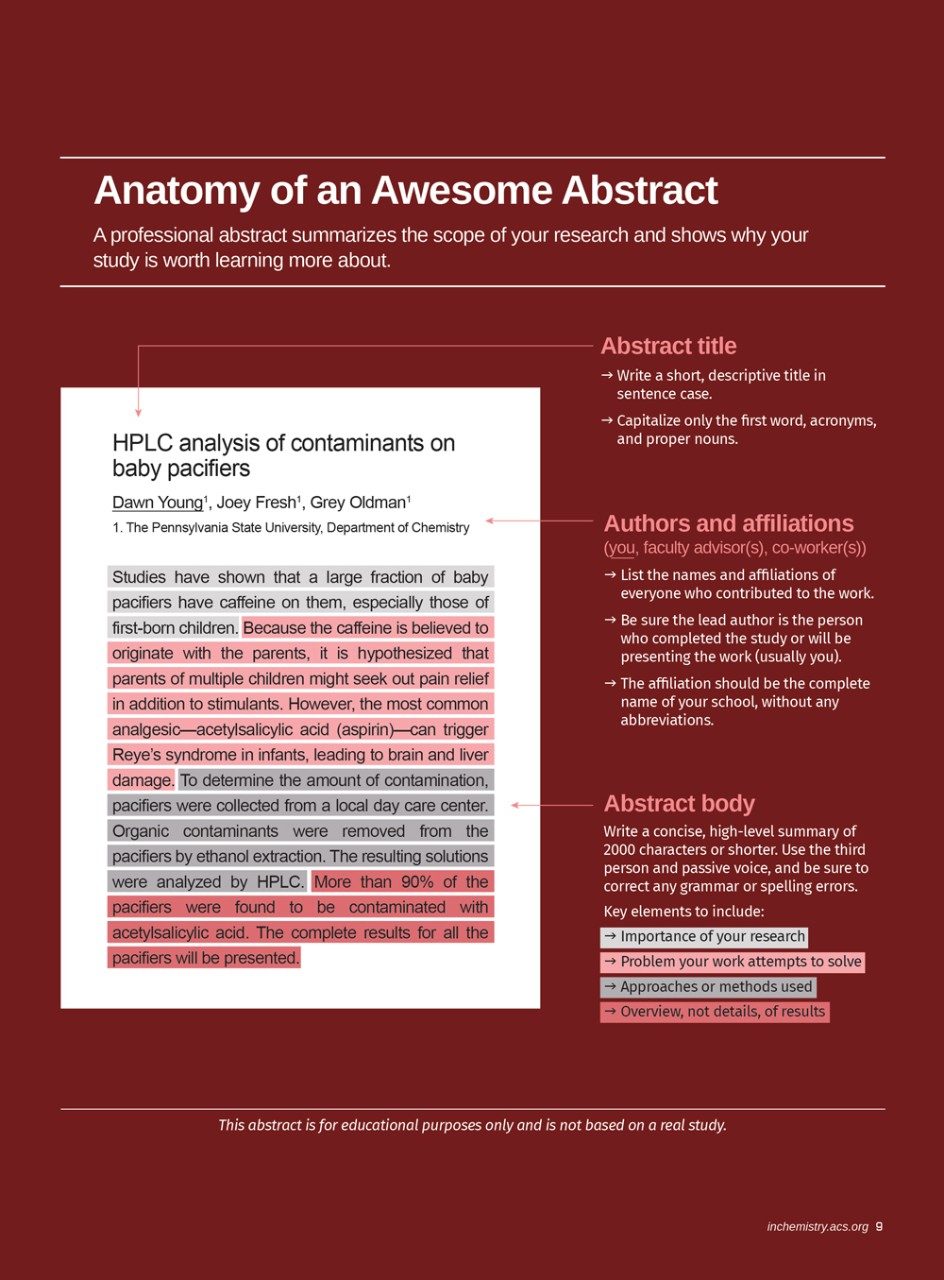

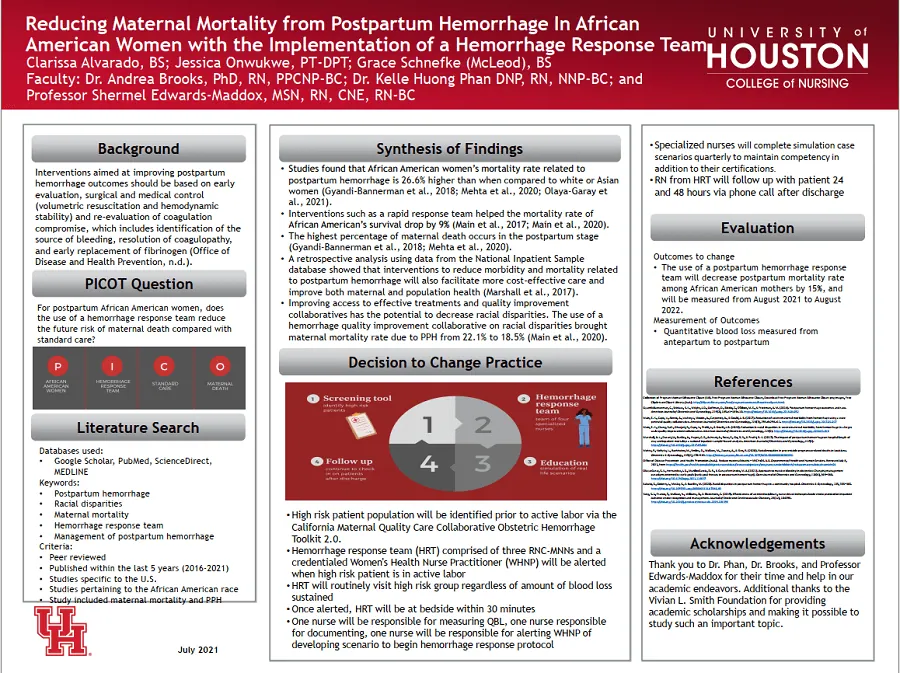

The abstract is a paragraph of text that appears at the top-left side of the poster ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). It is a summary of the entire poster. It should stand alone such that a person can read the abstract and understand all the research described in the poster. An abstract ( Fig. 3 ) contains four parts that should be written in the following order: Introduction, Materials & Methods, Results and Discussion. Each part typically consists of 2-4 sentences and the entire abstract will contain 200-300 words. An abstract consists strictly of text, it contains no figures, no tables, and typically it does not contain citations.

Figure 3. Abstract

Scientific Posters: A Learner's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Ella Weaver; Kylienne A. Shaul; Henry Griffy; and Brian H. Lower is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Event Website Publish a modern and mobile friendly event website.

- Registration & Payments Collect registrations & online payments for your event.

- Abstract Management Collect and manage all your abstract submissions.

- Peer Reviews Easily distribute and manage your peer reviews.

- Conference Program Effortlessly build & publish your event program.

- Virtual Poster Sessions Host engaging virtual poster sessions.

- Customer Success Stories

- Wall of Love ❤️

How to Write an Abstract For a Poster Presentation Application

Published on 15 Aug 2023

Attending a conference is a great achievement for a young researcher. Besides presenting your research to your peers, networking with researchers of other institutions and building future collaborations are other benefits.

Above all, it allows you to question your research and improve it based on the feedback you receive. As Sönke Ahrens wrote in How To Take Smart Notes "an idea kept private is as good as one you never had".

The poster presentation is one way to present your research at a conference. Contrary to some beliefs, poster presenters aren't the ones relegated to oral presentation and poster sessions are far from second zone presentations; Poster presentations favor natural interactions with peers and can lead to very valuable talks.

The application process

The abstract submitted during the application process is not the same as the poster abstract. The abstract submission is usually longer and you have to respect several points when writing it:

- Use the template provided by the conference organization (if applicable);

- Specify the abstract title, list author names, co-authors and the institutions in the banner;

- Use sub-headings to show out the structure of your abstract (if authorized);

- Respect the maximum word count (usually about a 300 word limit) and do not exceed one page;

- Exclude figures or graphs, keep them for your poster;

- Minimize the number of citations/references.

- Respect the submission deadline.

The 3 components of an abstract for a conference application

Most poster abstract submissions follow the classical IMRaD structure, also called the hourglass structure.

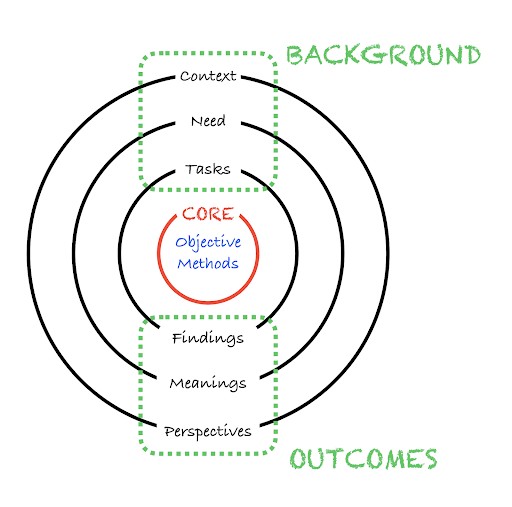

To make your abstract more memorable and impactful, you can try the Russian doll structure. Contrary to IMRaD, which has a more linear progression of ideas, the Russian doll structure emphasizes the WHY and WHAT. It unravels the research narrative layer by layer, capturing the reader’s attention more effectively.

Your abstract should be something the reviewer wants to open in order to discover the different layers of your research down to its core (like opening a Russian doll or peeling an onion). Then, it should be wrapped up elegantly with the outcomes (see figure below) like dressing the same Russian doll.

Hence, to design the best Russian doll, I recommend Jean-Luc Doumont's structure as detailed in his book Trees, Maps and Theorems that I adapted in 3 main components:

1. Background. The first component answers to the WHY and details the motivations of your research at different levels:

- Context : Why now? Describe the big picture, the current situation.

- Need : Why is it relevant to the reader? Describe the research question.

- Tasks : Why do we have to do this way? Review the studies related to your research question and emphasize the gap between the need and what was done.

2. Core . The center component answer to the HOW and consists in describing the objective of your research and its method:

- Objective : How did I focus on the need? Detail the purpose of your study.

- Methods : How did I proceed? Describe briefly the workflow (study population, softwares, tools, process, models, etc.)

3. Outcomes . The final component answers to the WHAT and details the take-aways of your research at different levels:

- Findings : What resulted from my method? Describe the main results (only).

- Meanings : What do the research findings mean to the reader? Discuss your results by linking them to your objective and research question.

- Perspectives : What should be the next steps? Propose further studies that could improve, complement or challenge yours.

It's worth noting that this structure emphasizes the WHY and the WHAT more than the HOW. It is the secret of great scientific storytelling .

The illustration below provides a clearer understanding of the logical flow among the three components and their respective layers. Note that, if authorized, sub-headings can be used for each section mentioned above.

4 tips to help get your abstract qualified

Here are some tips to give yourself the best chance of success for having your poster abstract accepted:

- Start by answering questions . It is very hard for the human brain to create something totally from scratch. Hence, allow the questions detailed above to guide you in creating the first path to explore.

- Write first, then edit . Do not try to do both at the same time. You won't get the final version of your abstract after your first try. Be patient, and "let your text die" before editing it with a fresh new point of view.

- "Kill your darlings'' . Not everything is necessary in the abstract. In Stephen Sondheim's words , West Side Story composer, "you have to throw out good stuff to get the best stuff". You will be amazed at just how surprising and efficient this tip is.

- Steal like an artist . As suggested by Austin Kleon's book title , get inspiration from others by reading other abstracts. It can be very helpful if you struggle finding punchy phrasing or transitions. I'm not referring to plagiarism, only getting good ideas about form (and not content) that can be adapted and used in your abstract.

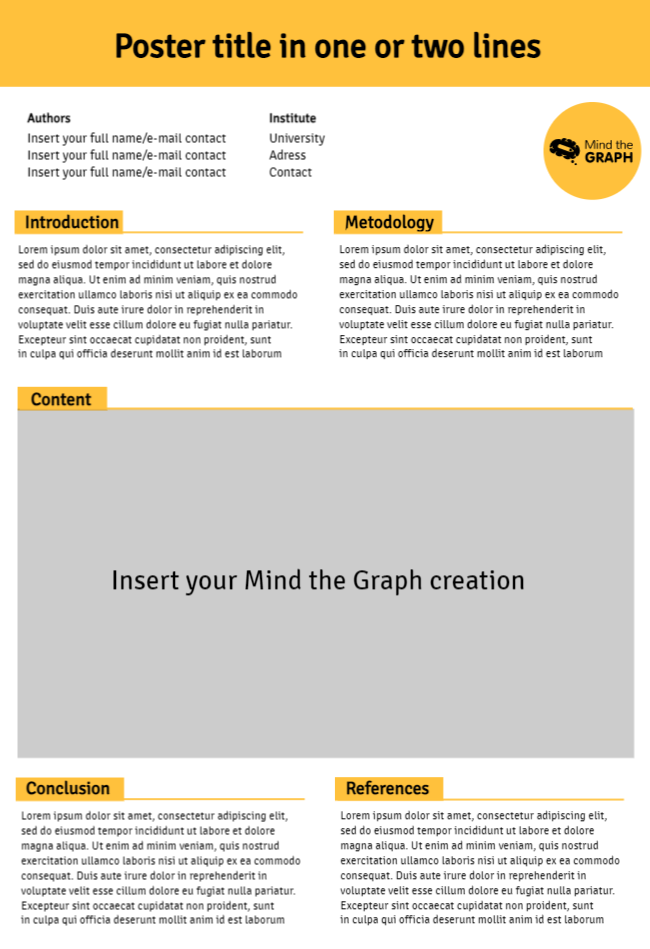

When you get accepted, it's time to design your poster board and prepare your pitch. Pick your favorite graphics software and bring your abstract to life with figures, tables, and colors. We have written an article on how to make a scientific poster , do not hesitate to take a look.

5 Best Event Registration Platforms for Your Next Conference

By having one software to organize registrations and submissions, a pediatric health center runs aro...

5 Essential Conference Apps for Your Event

In today’s digital age, the success of any conference hinges not just on the content and speakers bu...

How to Create an Academic Poster

- Designing Effective Research Posters

- Poster Templates

- Poster Printing Guidelines

How to Write a Poster Abstract or Proposal

- More Research Help

Little Memorial Library Printing Guidelines

How to print a poster:.

- Submit your poster print request here: https://midway.libwizard.com/f/posterprinting

- Submit your poster print request at least one week in advance of when you need it

- Go to the Business Office in LRC and pay for the poster (You may also call them at 859-846-5402 .)

- Wait for an email from The Center@Midway telling you to come pick up your poster

Printing specifications:

- Make your poster 36" x 48".

- Save your poster as a PDF. Only PDF files will be accepted.

- Use at least 300 dpi (but no more than 1200 dpi)

- File size should be no more than 10MB

- Poster must be school/study-related.

- Cost: $20 per poster (you will incur an additional $20 charge every time you want your poster re-printed because of a typo, wanting to change information, etc.).

- Poster Abstracts

What is an abstract/proposal and why should I write one?

If you want to submit your paper/research at a conference, you must first write a proposal. A poster proposal tells the conference committee what your poster is about and, depending on the conference guidelines, might include a poster abstract, your list of contributors, and/or presentation needs.

The poster abstract is the most important part of your proposal. It is a summary of your research poster, and tells the reader what your problem, method, results, and conclusions are. Most abstracts are only 75 -- 250 words long.

- << Previous: Poster Printing Guidelines

- Next: More Research Help >>

- Last Updated: Mar 23, 2021 11:17 AM

- URL: https://midway.libguides.com/AcademicPoster

RESEARCH HELP

- Research Guides

- Databases A-Z

- Journal Search

- Citation Help

LIBRARY SERVICES

- Accessibility

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

INSTRUCTION SUPPORT

- Course Reserves

- Library Instruction

- Little Memorial Library

- 512 East Stephens Street

- 859.846.5316

- [email protected]

How to Create a Research Poster

- Poster Basics

- Design Tips

- Logos & Images

What is a Research Poster?

Posters are widely used in the academic community, and most conferences include poster presentations in their program. Research posters summarize information or research concisely and attractively to help publicize it and generate discussion.

The poster is usually a mixture of a brief text mixed with tables, graphs, pictures, and other presentation formats. At a conference, the researcher stands by the poster display while other participants can come and view the presentation and interact with the author.

What Makes a Good Poster?

- Important information should be readable from about 10 feet away

- Title is short and draws interest

- Word count of about 300 to 800 words

- Text is clear and to the point

- Use of bullets, numbering, and headlines make it easy to read

- Effective use of graphics, color and fonts

- Consistent and clean layout

- Includes acknowledgments, your name and institutional affiliation

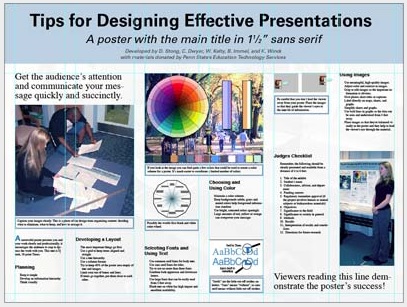

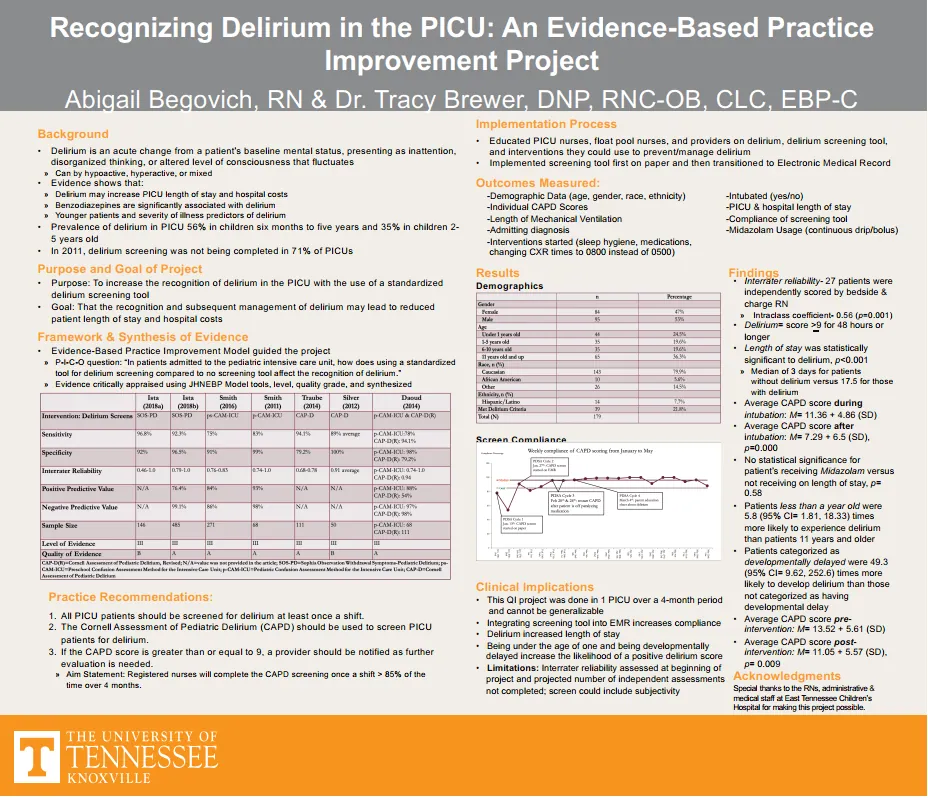

A Sample of a Well Designed Poster

View this poster example in a web browser .

Image credit: Poster Session Tips by [email protected], via Penn State

Where do I begin?

Answer these three questions:.

- What is the most important/interesting/astounding finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, photos, images?

- What kind of information can I convey during my talk that will complement my poster?

What software can I use to make a poster?

A popular, easy-to-use option. It is part of Microsoft Office package and is available on the library computers in rooms LC337 and LC336. ( Advice for creating a poster with PowerPoint ).

Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and InDesign

Feature-rich professional software that is good for posters including lots of high-resolution images, but they are more complex and expensive. NYU Faculty, Staff, and Students can access and download the Adobe Creative Suite .

Open Source Alternatives

- OpenOffice is the free alternative to MS Office (Impress is its PowerPoint alternative).

- Inkscape and Gimp are alternatives to Adobe products.

- For charts and diagrams try Gliffy or Lovely Charts .

- A complete list of free graphics software .

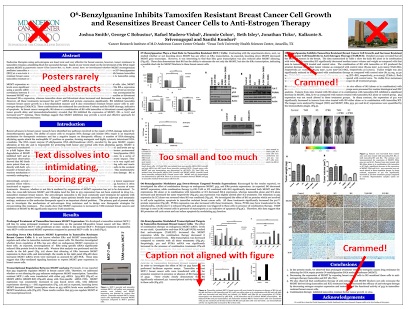

A Sample of a Poorly Designed Poster

View this bad poster example in a browser.

Image Credit: Critique by Better Posters

- Next: Design Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 5:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/posters

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare an...

How to prepare an effective research poster

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 1 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin

- 2 Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- mhiggins{at}nmh.ie

Being asked to give a poster presentation can be exciting, and you need not be daunted by the prospect of working out how to prepare one. As Lucia Hartigan and colleagues explain, many options are available

The long nights are over, the statistics have been run, the abstract has been written, and the email pops into your inbox: “Congratulations! You have been accepted for a poster presentation.”

All that work has been worthwhile. Your consultant congratulates you and your colleagues are envious of your having a legitimate excuse to go away for a couple of days, but now you have to work out how to prepare a poster. Do not despair, for you have many options.

Firstly, take this seriously. A poster is not a consolation prize for not being given an oral presentation. This is your chance to show your work, talk to others in the field, and, if you are lucky, to pick up pointers from experts. Given that just 45% of published abstracts end in a full paper, 1 this may be your only chance to get your work out there, so put some effort into it. If you don’t have access to the services of a graphic designer, then some work will be entailed as it normally takes us a full day to prepare the layout of a poster. If you are lucky enough to have help from a graphic designer, then you will need to check that the data are correct before it is sent to the printer. After all, it will be your name on the poster, not the graphic designer’s.

Secondly, check the details of the requirements. What size poster should you have? If it is too big, it may look arrogant. If it is too small, then it may seem too modest and self effacing. Should it be portrait or landscape? Different meetings have different requirements. Some may stay with traditional paper posters, so you need to factor in printing. Others present them electronically, but may have a deadline by which you need to have uploaded the poster. When planning a meeting the organisers work out how many poster boards there will be and then the numbers, so follow their requirements and read the small print.

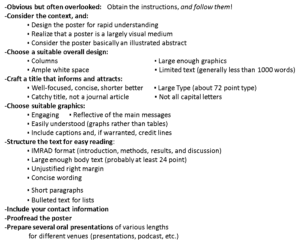

Then make a template. It can be tempting to “borrow” a poster template from someone else, and this may buy you some time, but it is important to check what page set-up and size have been selected for the template. If it’s meant for an A2 size and you wish to print your poster on A0 paper, then the stretching may lead to pixillation, which would not look good.

Next, think about your layout. Use text boxes to cover the following areas: title (with authors, institution, and logo), background, methods, results, and conclusions. Check that the text boxes are aligned by using gridlines, and justify your text. Use different colours for titles, and make sure you can read the title from 3 metres away. Some people will put their abstract in a separate box in the top right hand corner underneath the title, and then expand a little in the other areas. That is fine, so long as you follow the golden rule of writing a poster: do not include too much text. One study showed that less than 5% of conference attendees visit posters at meetings and that few ask useful questions. 2 The same research found that, in addition to the scientific content of a poster, the factors that increase visual appeal include pictures, graphs, and a limited use of words. 2 The ideal number of words seems to be between 300 and 400 per square metre.

Now make it look pretty and eye catching, and use lots of graphics. Outline text boxes or fill them with a different colour. If you can present the data using a graph, image, or figures rather than text, then do so, as this will add visual appeal. If you want to put a picture in the background, and it is appropriate to do so, fade the image so that it does not distract from the content.

Fonts are important. Check whether the meeting has set criteria for fonts; if they have, then follow them. You do not want to stand out for the wrong reason. If there are no specified criteria, then the title should be in point size 72-84, depending on the size of the poster. The authors’ names should be either the same size, but in italics, or else a couple of sizes smaller.

If you are including the hospital logo, don’t take a picture that will not size up properly when enlarged. Instead, obtain a proper copy from the hospital administrators.

References can be in small writing. No one is likely to read them, and you are including them only to remind yourself what you learnt in the literature review. One intriguing possibility is the use of a trigger image to link the poster to online content. 3

Finally, there are also things you should not do. Don’t leave your figures unlabelled, include spelling errors, use abbreviations without an explanation, or go outside the boundaries of the poster. Don’t be ashamed that you “only” have a poster. At a good meeting you may find that the comments from passers by are an amazing peer review. We have presented at meetings where world experts have given feedback, and with that feedback we have written the paper on the flight home.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

- ↵ Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 ; 2 : MR000005 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Goodhand JR, Giles CL, Wahed M, Irving PM, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Poster presentations at medical conferences: an effective way of disseminating research? Clin Med 2011 ; 1 : 138 -41. OpenUrl

- ↵ Atherton S, Javed M, Webster S, Hemington-Gorse S. Use of a mobile device app: a potential new tool for poster presentations and surgical education. J Visual Comm Med 2013 ; 36 (1-2): 6 -10. OpenUrl

Writing the Poster Abstract

Cite this chapter.

- Peter J. Gosling Ph.D. 2

505 Accesses

The poster abstract is the part of the overall presentation that is usually destined for publication in the proceedings or abstract book of the meeting. Specific skills are required to summarize large amounts of scientific text and data into a few sentences that still adequately set the scene and convey the appropriate message. The abstract is not merely a summary of your findings. It must be able to, and indeed will, stand alone. The restriction on the number of words, the format, and the deadline for receipt will be given by the conference organizers. It is common to supply a box outline in which the abstract must be typed or printed in a camera ready format. This is the lasting part of your presentation, and you need to devote a suitable amount of time to ensuring that it maintains the same high quality as the rest of your presentation. For this reason a good quality copy should be sent for publication, avoiding faxing, as the results are often difficult to read. For casual readers this may be the only part of your presentation that is seen. You should therefore avoid the use of phrases such as “evidence will be presented,” and make the abstract as representative of the whole presentation as possible.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Peter Gosling Associates, Staines, UK

Peter J. Gosling Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1999 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Gosling, P.J. (1999). Writing the Poster Abstract. In: Scientist’s Guide to Poster Presentations. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4613-7157-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4615-4761-7

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(1 Pt 1); 2007 Feb

Preparing and Presenting Effective Research Posters

Associated data.

APPENDIX A.2. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Contents.

Posters are a common way to present results of a statistical analysis, program evaluation, or other project at professional conferences. Often, researchers fail to recognize the unique nature of the format, which is a hybrid of a published paper and an oral presentation. This methods note demonstrates how to design research posters to convey study objectives, methods, findings, and implications effectively to varied professional audiences.

A review of existing literature on research communication and poster design is used to identify and demonstrate important considerations for poster content and layout. Guidelines on how to write about statistical methods, results, and statistical significance are illustrated with samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. A comparison of the content and format of papers, speeches, and posters is also provided.

Each component of a research poster about a quantitative analysis should be adapted to the audience and format, with complex statistical results translated into simplified charts, tables, and bulleted text to convey findings as part of a clear, focused story line.

Conclusions

Effective research posters should be designed around two or three key findings with accompanying handouts and narrative description to supply additional technical detail and encourage dialog with poster viewers.

An assortment of posters is a common way to present research results to viewers at a professional conference. Too often, however, researchers treat posters as poor cousins to oral presentations or published papers, failing to recognize the opportunity to convey their findings while interacting with individual viewers. By neglecting to adapt detailed paragraphs and statistical tables into text bullets and charts, they make it harder for their audience to quickly grasp the key points of the poster. By simply posting pages from the paper, they risk having people merely skim their work while standing in the conference hall. By failing to devise narrative descriptions of their poster, they overlook the chance to learn from conversations with their audience.

Even researchers who adapt their paper into a well-designed poster often forget to address the range of substantive and statistical training of their viewers. This step is essential for those presenting to nonresearchers but also pertains when addressing interdisciplinary research audiences. Studies of policymakers ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Sorian and Baugh 2002 ) have demonstrated the importance of making it readily apparent how research findings apply to real-world issues rather than imposing on readers to translate statistical findings themselves.

This methods note is intended to help researchers avoid such pitfalls as they create posters for professional conferences. The first section describes objectives of research posters. The second shows how to describe statistical results to viewers with varied levels of statistical training, and the third provides guidelines on the contents and organization of the poster. Later sections address how to prepare a narrative and handouts to accompany a research poster. Because researchers often present the same results as published research papers, spoken conference presentations, and posters, Appendix A compares similarities and differences in the content, format, and audience interaction of these three modes of presenting research results. Although the focus of this note is on presentation of quantitative research results, many of the guidelines about how to prepare and present posters apply equally well to qualitative studies.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH POSTER?

Preparing a poster involves not only creating pages to be mounted in a conference hall, but also writing an associated narrative and handouts, and anticipating the questions you are likely to encounter during the session. Each of these elements should be adapted to the audience, which may include people with different levels of familiarity with your topic and methods ( Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). For example, the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association draws academics who conduct complex statistical analyses along with practitioners, program planners, policymakers, and journalists who typically do not.

Posters are a hybrid form—more detailed than a speech but less than a paper, more interactive than either ( Appendix A ). In a speech, you (the presenter) determine the focus of the presentation, but in a poster session, the viewers drive that focus. Different people will ask about different facets of your research. Some might do policy work or research on a similar topic or with related data or methods. Others will have ideas about how to apply or extend your work, raising new questions or suggesting different contrasts, ways of classifying data, or presenting results. Beilenson (2004) describes the experience of giving a poster as a dialogue between you and your viewers.

By the end of an active poster session, you may have learned as much from your viewers as they have from you, especially if the topic, methods, or audience are new to you. For instance, at David Snowdon's first poster presentation on educational attainment and longevity using data from The Nun Study, another researcher returned several times to talk with Snowdon, eventually suggesting that he extend his research to focus on Alzheimer's disease, which led to an important new direction in his research ( Snowdon 2001 ). In addition, presenting a poster provides excellent practice in explaining quickly and clearly why your project is important and what your findings mean—a useful skill to apply when revising a speech or paper on the same topic.

WRITING FOR A VARIED PROFESSIONAL AUDIENCE

Audiences at professional conferences vary considerably in their substantive and methodological backgrounds. Some will be experts on your topic but not your methods, some will be experts on your methods but not your topic, and most will fall somewhere in between. In addition, advances in research methods imply that even researchers who received cutting-edge methodological training 10 or 20 years ago might not be conversant with the latest approaches. As you design your poster, provide enough background on both the topic and the methods to convey the purpose, findings, and implications of your research to the expected range of readers.

Telling a Simple, Clear Story

Write so your audience can understand why your work is of interest to them, providing them with a clear take-home message that they can grasp in the few minutes they will spend at your poster. Experts in communications and poster design recommend planning your poster around two to three key points that you want your audience to walk away with, then designing the title, charts, and text to emphasize those points ( Briscoe 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Start by introducing the two or three key questions you have decided will be the focus of your poster, and then provide a brief overview of data and methods before presenting the evidence to answer those questions. Close with a summary of your findings and their implications for research and policy.

A 2001 survey of government policymakers showed that they prefer summaries of research to be written so they can immediately see how the findings relate to issues currently facing their constituencies, without wading through a formal research paper ( Sorian and Baugh 2002 ). Complaints that surfaced about many research reports included that they were “too long, dense, or detailed,” or “too theoretical, technical, or jargony.” On average, respondents said they read only about a quarter of the research material they receive for detail, skim about half of it, and never get to the rest.

To ensure that your poster is one viewers will read, understand, and remember, present your analyses to match the issues and questions of concern to them, rather than making readers translate your statistical results to fit their interests ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). Often, their questions will affect how you code your data, specify your model, or design your intervention and evaluation, so plan ahead by familiarizing yourself with your audience's interests and likely applications of your study findings. In an academic journal article, you might report parameter estimates and standard errors for each independent variable in your regression model. In the poster version, emphasize findings for specific program design features, demographic, or geographic groups, using straightforward means of presenting effect size and statistical significance; see “Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts” and “Presenting Statistical Test Results” below.

The following sections offer guidelines on how to present statistical findings on posters, accompanied by examples of “poor” and “better” descriptions—samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. These ideas are illustrated with results from a multilevel analysis of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP; Phillips et al. 2004 ). I chose that paper to show how to prepare a poster about a sophisticated quantitative analysis of a topic of interest to HSR readers, and because I was a collaborator in that study, which was presented in the three formats compared here—as a paper, a speech, and a poster.

Explaining Statistical Methods

Beilenson (2004) and Briscoe (1996) suggest keeping your description of data and methods brief, providing enough information for viewers to follow the story line and evaluate your approach. Avoid cluttering the poster with too much technical detail or obscuring key findings with excessive jargon. For readers interested in additional methodological information, provide a handout and a citation to the pertinent research paper.

As you write about statistical methods or other technical issues, relate them to the specific concepts you study. Provide synonyms for technical and statistical terminology, remembering that many conferences of interest to policy researchers draw people from a range of disciplines. Even with a quantitatively sophisticated audience, don't assume that people will know the equivalent vocabulary used in other fields. A few years ago, the journal Medical Care published an article whose sole purpose was to compare statistical terminology across various disciplines involved in health services research so that people could understand one another ( Maciejewski et al. 2002 ). After you define the term you plan to use, mention the synonyms from the various fields represented in your audience.

Consider whether acronyms are necessary on your poster. Avoid them if they are not familiar to the field or would be used only once or twice on your poster. If you use acronyms, spell them out at first usage, even those that are common in health services research such as “HEDIS®”(Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set) or “HLM”(hierarchical linear model).

Poor: “We use logistic regression and a discrete-time hazards specification to assess relative hazards of SCHIP disenrollment, with plan level as our key independent variable.” Comment: Terms like “discrete-time hazards specification” may be confusing to readers without training in those methods, which are relatively new on the scene. Also the meaning of “SCHIP” or “plan level” may be unfamiliar to some readers unless defined earlier on the poster.

Better: “Chances of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) vary by amount of time enrolled, so we used hazards models (also known as event history analysis or survival analysis) to correct for those differences when estimating disenrollment patterns for SCHIP plans for different income levels.” Comment: This version clarifies the terms and concepts, naming the statistical method and its synonyms, and providing a sense of why this type of analysis is needed.

To explain a statistical method or assumption, paraphrase technical terms and illustrate how the analytic approach applies to your particular research question and data:

Poor : “The data structure can be formulated as a two-level hierarchical linear model, with families (the level-1 unit of analysis) nested within counties (the level-2 unit of analysis).” Comment: Although this description would be fine for readers used to working with this type of statistical model, those who aren't conversant with those methods may be confused by terminology such as “level-1” and “unit of analysis.”

Better: “The data have a hierarchical (or multilevel) structure, with families clustered within counties.” Comment: By replacing “nested” with the more familiar “clustered,” identifying the specific concepts for the two levels of analysis, and mentioning that “hierarchical” and “multilevel” refer to the same type of analytic structure, this description relates the generic class of statistical model to this particular study.

Presenting Results with Charts

Charts are often the preferred way to convey numeric patterns, quickly revealing the relative sizes of groups, comparative levels of some outcome, or directions of trends ( Briscoe 1996 ; Tufte 2001 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). As Beilenson puts it, “let your figures do the talking,” reducing the need for long text descriptions or complex tables with lots of tiny numbers. For example, create a pie chart to present sample composition, use a simple bar chart to show how the dependent variable varies across subgroups, or use line charts or clustered bar charts to illustrate the net effects of nonlinear specifications or interactions among independent variables ( Miller 2005 ). Charts that include confidence intervals around point estimates are a quick and effective way to present effect size, direction, and statistical significance. For multivariate analyses, consider presenting only the results for the main variables of interest, listing the other variables in the model in a footnote and including complex statistical tables in a handout.

Provide each chart with a title (in large type) that explains the topic of that chart. A rhetorical question or summary of the main finding can be very effective. Accompany each chart with a few annotations that succinctly describe the patterns in that chart. Although each chart page should be self-explanatory, be judicious: Tufte (2001) cautions against encumbering your charts with too much “nondata ink”—excessive labeling or superfluous features such as arrows and labels on individual data points. Strive for a balance between guiding your readers through the findings and maintaining a clean, uncluttered poster. Use chart types that are familiar to your expected audience. Finally, remember that you can flesh out descriptions of charts and tables in your script rather than including all the details on the poster itself; see “Narrative to Accompany a Poster.”

Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts

As you describe patterns or numeric contrasts, whether from simple calculations or complex statistical models, explain both the direction and magnitude of the association. Incorporate the concepts under study and the units of measurement rather than simply reporting coefficients (β's) ( Friedman 1990 ; Miller 2005 ).

Poor: “Number of enrolled children in the family is correlated with disenrollment.” Comment: Neither the direction nor the size of the association is apparent.

Poor [version #2]: “The log-hazard of disenrollment for one-child families was 0.316.” Comment: Most readers find it easier to assess the size and direction from hazards ratios (a form of relative risk) instead of log-hazards (log-relative risks, the β's from a hazards model).

Better: “Families with only one child enrolled in the program were about 1.4 times as likely as larger families to disenroll.” Comment: This version explains the association between number of children and disenrollment without requiring viewers to exponentiate the log-hazard in their heads to assess the size and direction of that association. It also explicitly identifies the group against which one-child families are compared in the model.

Presenting Statistical Test Results

On your poster, use an approach to presenting statistical significance that keeps the focus on your results, not on the arithmetic needed to conduct inferential statistical tests. Replace standard errors or test statistics with confidence intervals, p- values, or symbols, or use formatting such as boldface, italics, or a contrasting color to denote statistically significant findings ( Davis 1997 ; Miller 2005 ). Include the detailed statistical results in handouts for later perusal.

To illustrate these recommendations, Figures 1 and and2 2 demonstrate how to divide results from a complex, multilevel model across several poster pages, using charts and bullets in lieu of the detailed statistical table from the scientific paper ( Table 1 ; Phillips et al. 2004 ). Following experts' advice to focus on one or two key points, these charts emphasize the findings from the final model (Model 5) rather than also discussing each of the fixed- and random-effects specifications from the paper.

Presenting Complex Statistical Results Graphically

Text Summary of Additional Statistical Results

Multilevel Discrete-Time Hazards Models of Disenrollment from SCHIP, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Source : Phillips et al. (2004) .

SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; LRH, log relative-hazard; SE, standard error.

Figure 1 uses a chart (also from the paper) to present the net effects of a complicated set of interactions between two family-level traits (race and SCHIP plan) and a cross-level interaction between race of the family and county physician racial composition. The title is a rhetorical question that identifies the issue addressed in the chart, and the annotations explain the pattern. The chart version substantially reduces the amount of time viewers need to understand the main take-home point, averting the need to mentally sum and exponentiate several coefficients from the table.

Figure 2 uses bulleted text to summarize other key results from the model, translating log-relative hazards into hazards ratios and interpreting them with minimal reliance on jargon. The results for family race, SCHIP plan, and county physician racial composition are not repeated in Figure 2 , averting the common problem of interpreting main effect coefficients and interaction coefficients without reference to one another.

Alternatively, replace the text summary shown in Figure 2 with Table 2 —a simplified version of Table 1 which presents only the results for Model 5, replaces log-relative hazards with hazards ratios, reports associated confidence intervals in lieu of standard errors, and uses boldface to denote statistical significance. (On a color slide, use a contrasting color in lieu of bold.)

Relative Risks of SCHIP Disenrollment for Other * Family and County Characteristics, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

Based on hierarchical linear model controlling for months enrolled, months-squared, race, SCHIP plan, county physician racial composition, and all variables shown here. Scaled deviance =30,895. Random effects estimate for between-county variance =0.005 (standard error =0.006). SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

CONTENTS AND ORGANIZATION OF A POSTER

Research posters are organized like scientific papers, with separate pages devoted to the objectives and background, data and methods, results, and conclusions ( Briscoe 1996 ). Readers view the posters at their own pace and at close range; thus you can include more detail than in slides for a speech (see Appendix A for a detailed comparison of content and format of papers, speeches, and posters). Don't simply post pages from the scientific paper, which are far too text-heavy for a poster. Adapt them, replacing long paragraphs and complex tables with bulleted text, charts, and simple tables ( Briscoe 1996 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Fink (1995) provides useful guidelines for writing text bullets to convey research results. Use presentation software such as PowerPoint to create your pages or adapt them from related slides, facilitating good page layout with generous type size, bullets, and page titles. Such software also makes it easy to create matching handouts (see “Handouts”).

The “W's” (who, what, when, where, why) are an effective way to organize the elements of a poster.

- In the introductory section, describe what you are studying, why it is important, and how your analysis will add to the existing literature in the field.

- In the data and methods section of a statistical analysis, list when, where, who, and how the data were collected, how many cases were involved, and how the data were analyzed. For other types of interventions or program evaluations, list who, when, where, and how many, along with how the project was implemented and assessed.

- In the results section, present what you found.

- In the conclusion, return to what you found and how it can be used to inform programs or policies related to the issue.

Number and Layout of Pages

To determine how many pages you have to work with, find out the dimensions of your assigned space. A 4′ × 8′ bulletin board accommodates the equivalent of about twenty 8.5″ × 11″ pages, but be selective—no poster can capture the full detail of a large series of multivariate models. A trifold presentation board (3′ high by 4′ wide) will hold roughly a dozen pages, organized into three panels ( Appendix B ). Breaking the arrangement into vertical sections allows viewers to read each section standing in one place while following the conventions of reading left-to-right and top-to-bottom ( Briscoe 1996 ).

- At the top of the poster, put an informative title in a large, readable type size. On a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, there should also be room for an institutional logo.

Suggested Layout for a 4′ × 8′ poster.

- In the left-hand panel, set the stage for the research question, conveying why the topic is of policy interest, summarizing major empirical or theoretical work on related topics, and stating your hypotheses or project aims, and explaining how your work fills in gaps in previous analyses.

- In the middle panel, briefly describe your data source, variables, and methods, then present results in tables or charts accompanied by text annotations. Diagrams, maps, and photographs are very effective for conveying issues difficult to capture succinctly in words ( Miller 2005 ), and to help readers envision the context. A schematic diagram of relationships among variables can be useful for illustrating causal order. Likewise, a diagram can be a succinct way to convey timing of different components of a longitudinal study or the nested structure of a multilevel dataset.

- In the right-hand panel, summarize your findings and relate them back to the research question or project aims, discuss strengths and limitations of your approach, identify research, practice, or policy implications, and suggest directions for future research.

Figure 3 (adapted from Beilenson 2004 ) shows a suggested layout for a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, designed to be created using software such as Pagemaker that generates a single-sheet presentation; Appendix C shows a complete poster version of the Phillips et al. (2004) multilevel analysis of SCHIP disenrollment. If hardware or budget constraints preclude making a single-sheet poster, a similar configuration can be created using standard 8.5″ × 11″ pages in place of the individual tables, charts, or blocks of text shown in Figure 3 .

Find out well in advance how the posters are to be mounted so you can bring the appropriate supplies. If the room is set up for table-top presentations, tri-fold poster boards are essential because you won't have anything to attach a flat poster board or pages to. If you have been assigned a bulletin board, bring push-pins or a staple gun.

Regardless of whether you will be mounting your poster at the conference or ahead of time, plan how the pages are to be arranged. Experiment with different page arrangements on a table marked with the dimensions of your overall poster. Once you have a final layout, number the backs of the pages or draw a rough sketch to work from as you arrange the pages on the board. If you must pin pages to a bulletin board at the conference venue, allow ample time to make them level and evenly spaced.

Other Design Considerations

A few other issues to keep in mind as you design your poster. Write a short, specific title that fits in large type size on the title banner of your poster. The title will be potential readers' first glimpse of your poster, so make it inviting and easy to read from a distance—at least 40-point type, ideally larger. Beilenson (2004) advises embedding your key finding in the title so viewers don't have to dig through the abstract or concluding page to understand the purpose and conclusions of your work. A caution: If you report a numeric finding in your title, keep in mind that readers may latch onto it as a “factoid” to summarize your conclusions, so select and phrase it carefully ( McDonough 2000 ).

Use at least 14-point type for the body of the poster text. As Briscoe (1996) points out, “many in your audience have reached the bifocal age” and all of them will read your poster while standing, hence long paragraphs in small type will not be appreciated! Make judicious use of color. Use a clear, white, or pastel for the background, with black or another dark color for most text, and a bright, contrasting shade to emphasize key points or to identify statistically significant results ( Davis 1997 ).

NARRATIVE TO ACCOMPANY A POSTER

Prepare a brief oral synopsis of the purpose, findings, and implications of your work to say to interested parties as they pause to read your poster. Keep it short—a few sentences that highlight what you are studying, a couple of key findings, and why they are important. Design your overview as a “sound byte” that captures your main points in a succinct and compelling fashion ( Beilenson 2004 ). After hearing your introduction, listeners will either nod and move along or comment on some aspect of your work that intrigues them. You can then tailor additional discussion to individual listeners, adjusting the focus and amount of detail to suit their interests. Gesture at the relevant pages as you make each point, stating the purpose of each chart or table and explaining its layout before describing the numeric findings; see Miller (2005) for guidelines on how to explain tables and charts to a live audience. Briscoe (1996) points out that these mini-scripts are opportunities for you to fill in details of your story line, allowing you to keep the pages themselves simple and uncluttered.

Prepare short answers to likely questions about various aspects of your work, such as why it is important from a policy or research perspective, or descriptions of data, methods, and specific results. Think of these as little modules from an overall speech—concise descriptions of particular elements of your study that you can choose among in response to questions that arise. Beilenson (2004) also recommends developing a few questions to ask your viewers, inquiring about their reactions to your findings, ideas for additional questions, or names of others working on the topic.

Practice your poster presentation in front of a test audience acquainted with the interests and statistical proficiency of your expected viewers. Ideally, your critic should not be too familiar with your work: A fresh set of eyes and ears is more likely to identify potential points of confusion than someone who is jaded from working closely with the material while writing the paper or drafting the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ). Ask your reviewer to identify elements that are unclear, flag jargon to be paraphrased or defined, and recommend changes to improve clarity ( Miller 2005 ). Have them critique your oral presentation as well as the contents and layout of the poster.

Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers. These can be produced from slides created in presentation software, printed several to a page along with a cover page containing the abstract and your contact information. Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts. Handouts provide access to the more detailed literature review, data and methods, full set of results, and citations without requiring viewers to read all of that information from the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ; Miller 2005 ). Although you also can bring copies of the complete paper, it is easier on both you and your viewers if you collect business cards or addresses and mail the paper later.

The quality and effectiveness of research posters at professional conferences is often compromised by authors' failure to take into account the unique nature of such presentations. One common error is posting numerous statistical tables and long paragraphs from a research paper—an approach that overwhelms viewers with too much detail for this type of format and presumes familiarity with advanced statistical techniques. Following recommendations from the literature on research communication and poster design, this paper shows how to focus each poster on a few key points, using charts and text bullets to convey results as part of a clear, straightforward story line, and supplementing with handouts and an oral overview.

Another frequent mistake is treating posters as a one-way means of communication. Unlike published papers, poster sessions are live presentations; unlike speeches, they allow for extended conversation with viewers. This note explains how to create an oral synopsis of the project, short modular descriptions of poster elements, and questions to encourage dialog. By following these guidelines, researchers can substantially improve their conference posters as vehicles to disseminate findings to varied research and policy audiences.

CHECKLIST FOR PREPARING AND PRESENTING AN EFFECTIVE RESEARCH POSTERS

- Design poster to focus on two or three key points.

- Adapt materials to suit expected viewers' knowledge of your topic and methods.

- Design questions to meet their interests and expected applications of your work.

- Paraphrase descriptions of complex statistical methods.

- Spell out acronyms if used.

- Replace large detailed tables with charts or small, simplified tables.

- Accompany tables or charts with bulleted annotations of major findings.

- Describe direction and magnitude of associations.

- Use confidence intervals, p -values, symbols, or formatting to denote statistical significance.

Layout and Format

- Organize the poster into background, data and methods, results, and study implications.

- Divide the material into vertical sections on the poster.

- Use at least 14-point type in the body of your poster, at least 40-point for the title.

Narrative Description

- Rehearse a three to four sentence overview of your research objectives and main findings.

- Summary of key studies and gaps in existing literature

- Data and methods

- Each table, chart, or set of bulleted results

- Research, policy, and practice implications

- Solicit their input on your findings

- Develop additional questions for later analysis

- Identify other researchers in the field

- Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers.

- Print slides from presentation software, several to a page.

- Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts.

- Include an abstract and contact information.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ellen Idler, Julie Phillips, Deborah Carr, Diane (Deedee) Davis, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this work.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material for this article is available online:

APPENDIX A.1. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Materials and Audience Interaction.

Suggested Layout for a Tri-Fold Presentation Board.

Example Research Poster of Phillips et al. 2004 Study.

- Beilenson J. Developing Effective Poster Presentations. Gerontology News. 2004; 32 (9):6–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Briscoe MH. Preparing Scientific Illustrations: A Guide to Better Posters, Presentations, and Publications. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M. Scientific Papers and Presentations. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiFranza JR. A Researcher's Guide to Effective Dissemination of Policy-Related Research. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1996. the Staff of the Advocacy Institute, with Assistance from the Center for Strategic Communications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink A. How to Report on Surveys. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman GD. Be Kind to Your Reader. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990; 132 (4):591–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maciejewski ML, Diehr P, Smith MA, Hebert P. Common Methodological Terms in Health Services Research and Their Symptoms. Medical Care. 2002; 40 :477–84. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonough J. Experiencing Politics: A Legislator's Stories of Government and Health Care. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JE. The Chicago Guide to Writing about Multivariate Analysis. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson DE, Brownson RC, Remington PL, Parvanta C, editors. Communicating Public Health Information Effectively: A Guide for Practitioners. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips JA, Miller JE, Cantor JC, Gaboda D. Context or Composition. What Explains Variation in SCHIP Disenrollment? Health Services Research. 2004; 39 (4, part I):865–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snowdon D. Aging with Grace: What the Nun Study Teaches Us about Leading Longer, Healthier, and More Meaningful Lives. New York: Bantam Books; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorian R, Baugh T. Power of Information Closing the Gap between Research and Policy. Health Affairs. 2002; 21 (2):264–73. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Meetings & Events

- ACS Meetings & Expositions

- ACS Fall 2024

How to Write an Undergraduate Abstract

Writing an abstract for the undergraduate research poster session.

By Elzbieta Cook, Louisiana State University

General Rules and Accepted Practices

Successful abstracts exhibit what is generally accepted as good scientific communication. The following guidelines specify all aspects of how a good abstract is written.

The Title is informative; it is neither too long nor too short, and it does not oversell or sensationalize the content of the presentation.

- Make the title descriptive, yet short and sweet.

- Do not start the t itle with “The”, “A”, or “An.”

- Capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the title, the first letter of the first word after a colon, and any proper names, acronyms (e.g., NMR) or chemical formulas (e.g., NaOH).

- Do not put a period at the end of the title.

The body of the abstract briefly frames the researched issue, succinctly describes the performed research, and outlines the findings and general conclusions without going into too many details or numbers.

- Do not write everything you did in your work. Briefly frame the research you will be describing. Your poster will be a better place to elaborate on selected aspects of your research. Instead, make general statements in regards to what was done, what techniques were used, what type of information was gained (without going into details of specific results), and what the potential benefits or significance of the findings are.

- Ensure that the content of the abstract is approved by your research advisor. In addition to getting valuable feedback on how you write, your research advisor will know which results are ready to be shared in your presentation and which belong elsewhere. Additionally, the advisor is responsible for your work and, consequently, your work and results.

- Do not make literature references to other published research in the abstract. A good place for literature references is in the introduction of your poster. Likewise, unless specifically requested by the session organizers, do not include funding information in the abstract. Your research program and funding sources can be mentioned in the acknowledgment part of your poster.

- Do not use “I” and “we” when reporting on you research. It is okay to state, for instance, that “research in our group is focused on…” The passive voice is still the standard in scientific literature, even if it makes your English teacher cringe.

- Exercise restraint when placing figures, schemes, and tables in the abstract. The body of your poster is a much better place for the majority of artwork. Having said that, figures, schemes, and tables are allowed in the abstract, but you need to watch the character count, as these features quickly add hundreds of characters.

- Limit the number of characters for the entire abstract to 2,500 . This includes the title, the body, and the authors, along with their affiliations.

The list of authors, in addition to the presenting undergraduate student(s), always includes the name of the research advisor(s) as well as any other non-presenting author who contributed to the presented work.

- The list of authors must include the presenting author(s) . The presenting author is you and any other undergraduate student who will present the research with you.

- Include the name(s) of your research advisor(s) on the list of poster authors. With few exceptions, undergraduate research is typically funded through a grant applied for and received by a research mentor, and must be properly acknowledged. Your research project is likely the brainchild of your research advisor, even if you contributed to its development. Remember that credit must go where it belongs! Even if you are the only person who performs the experiments, you do so under the supervision of a research advisor or graduate student (who, in turn, is financially supported by the mentor). In addition, the costs of hosting you in the laboratory, including disposables, software licenses, hazardous waste disposal, and even the costs of keeping the lab air-conditioned, the lights on and the elevator functioning, are typically courtesy of the host group (covered from your mentor’s indirect costs). The reviewer of your abstract will check whether the list of authors includes the name of the research advisor. Submissions without this information will not be accepted until the necessary correction is made.

- List the presenting author first. While there is no strict rule about the order of authors, it is common that the presenting author is listed first. If there is more than one presenting author, the order should follow that of their contributions, followed by non-presenting authors, with the research mentor being listed at the end. Some research mentors elect to be the first authors on undergraduate research posters, but care must be taken so that they are not listed as presenting authors. Again, the reviewer of your abstract will check to see whether the research mentor is listed as a presenting author, and if that is the case, the abstract will be returned to the authors for further clarification.

NOTE: Only undergraduate students are allowed to present in the Undergraduate Research Poster session. Any research mentor who wishes to present the results from an undergraduate project must do so in another session.

Affiliations

- Ensure that the name and the address of each college, university, institute, etc., is the same for all authors who come from that school. For instance, MAPS, the ACS’s abstract submission system, will “think” that Penn State and The Pennsylvania State University are two different schools and will assign two different affiliations to authors who were, after all, working in the same lab!

- The order of affiliations should follow the order of authors.

Submitting an Abstract to the Correct Session

It is a common error for students and faculty to submit a poster abstract to an incorrect session. The confusion often comes from the fact that the Chemical Education division of the ACS (DivCHED) accepts two types of poster abstracts: those from faculty about their chemical education research and those from undergraduate students about their research in a particular technical discipline.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session in DivCHED is custom made for undergraduate student research. It is a good place to submit an abstract here, whether it’s your first presentation at a National Meeting or your third or fourth (as long as you’re still an undergrad).

Nevertheless, you should consult with your research advisor to find the right place to submit. If you do plan on submitting to a division other than DivCHED (e.g. Division of Analytical Chemistry), it’s a good idea to check with the division program chair to find the best place to showcase your research.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session is meant only for undergraduate student presenters (i.e., you!). ACS has created several sub-divisions for the various sub-disciplines in chemistry, so you can present in an area that closely relates to your research.

In the Undergraduate Research Poster Session, you’ll want to choose the area of chemistry your research fits best, such as biochemistry, environmental, etc. If your undergraduate research is organic chemistry, for example, select Undergraduate Research Posters: Organic Chemistry-Poster . Only if you have helped to develop a new laboratory experiment or in-class demonstration, or you have analyzed learning outcomes of new learning strategies or a new pedagogy—will you want to submit your abstract to Undergraduate Research Posters: Chemical Education-Poster.

Remember, you, as an undergraduate researcher, must register and attend the meeting to present your work. Please note that if a faculty researcher, a postdoctoral candidate, or a graduate student wishes to present a poster on chemistry education research, they should submit their abstract to the CHED division in the General Poster Session. This article is not meant for such submissions.

Get Support

Talk to our meetings team.

Contacts for registration, hotel, presenter support or any other questions.

Contact Meetings Team

Denver, CO & Hybrid

Colorado Convention Center | August 18 - 22

#ACSFall2024

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Research Posters : Step by step

- Elements of a poster

- Step by step

- Visualizations & images

- Illinois logo

- Archiving - Grad Students

- More Resources

- Oral Presentations

- 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium This link opens in a new window

CREATING YOUR POSTER

You have two choices when creating a research poster:

- You can create your poster from scratch by using PowerPoint, Adobe InDesign, or a similar design program.

- You can use one of the University of Illinois Research Poster Templates .

Sizing your Poster

- If you are presenting for the Undergraduate Research Symposium , resize your slide to width 48 inches by height 36 inches.

- If you are presenting at a professional conference , your instructions should indicate the size limits of your poster. Standard U.S. conference poster size is 48" by 36".

***IMPORTANT: You must change the size of your slide before you start working on your poster. This will ensure that your images and text do not become pixilated when the poster is printed. See below for specific instructions.

How to correctly size your poster in PowerPoint:

- Select the "Design" tab

- Click "Slide Size"

- Select "Page Setup"

- Under the "Slides sized for:" dropdown menu, select "Custom"

- Set the "Width" and "Height" to what is needed for your poster

- Click "OK"

How to correctly size your poster in Adobe InDesign:

When a new document is created in Adobe InDesign, a dialogue box prompts you to enter dimensions:

- Change the dimension metric to inches from the drop down box.

- Margins are intentional space from an object to the edge of the poster, intended not to be trimmed. You can set this to 0 inches on all sides unless you have a specific plan to use margins in your design.

- Bleed shows the printer where to trim white space that occurs when printing color onto white poster paper. If you are printing your poster, include at least a 0.25 inch bleed on each side; remember not to place any content in the bleed as it will be trimmed by the printer.

- Slug is a space for the creator to leave any notes for the printer. You can set this to 0 inches unless you have notes.

If you ever want to change your poster dimensions after starting the poster, you can do so through the Document Setup Menu .

Using multiple font styles can really make your poster stand out and look professional. Consult this graphic to understand different font styles, what fonts work best together, and what fonts to avoid.

COLOR SCHEME CHOICES

Sticking to a color scheme can help your poster look professional. Consistent use of color can help your viewer understand how information is organized on your poster. Not sure where to start with color?

- Pick colors from an image (including a custom one you're planning to use on your poster)

- Use Illinois branding colors

Not sure what to do with the hex code from a brand guide or color palette generator?

- Adobe InDesign

Always check that your text is accessible on background colors using WebAIM's free contrast checker.

If printing your poster, it's a good idea to do a small-scale test print of your poster before getting it printed. Colors often appear brighter and more vibrant on a screen than when printed. There still might be some variation in color depending on the color scale the printer uses, but it will be a closer match on paper than what you see on screen.

WHAT TO INCLUDE IN YOUR POSTER

All posters MUST have:

- Title: Make it catchy and use at least 72 pt. font.

- Your name and contact information.

- Institutional affiliation, see the Illinois logo tab above.

You many also include:

- Research question or hypothesis: Do not copy your abstract if it is included in the program.

- Methodology: What is the research process that you used? Explain how you did your research.

- Your interview questions.

- Observations: What did you see? Why is this important?

- Findings: What did you learn? Summarize your conclusions.

- Themes: Pull out themes in the literature and list in bullet points.

- Consider a brief narrative of what you learned - what was the most interesting/surprising aspect of your project?

- Add interesting quotes from your research.

- Data: Use your data to generate charts or tables.

- Images: Include images (visit the Visualization & Images tab in the guide for more information). Take your own or legally use others.

- Recommendations and/or next steps for future research.

- Citations: Only list 3-5 on your poster. If you have more, put them on your handout.

- Acknowledgements: Don't forget to thank your advisor, department, or funding agency.

More helpful tips

- Read Colin Purrington's suggestions for successful poster design.

- Be creative in your display, think beyond the text of your paper. You can use boxes, formatting, font, and images to break up the sections of your research poster.

- Think carefully about your title. If you would like a longer, more descriptive title, consider a subtitle. Brainstorm several titles and have a peer/colleague/friend/teacher rank them. The title needs to highlight your subject matter, but it does not need to state all your conclusions. Some good titles simply ask questions, others answer them.

- You can section your poster according to the major points about your research you want to convey. For example: title, abstract, methodology, data, results, and conclusion. Consider the flow of your poster--these should be in a logical, easy-to-read order. Remember that most people read from left to right and top to bottom.

- Qualitative data (e.g. quotes from references and/or interviews) can also be shared on your poster. Make sure you include captions, legends, annotations, citations, and footnotes, if necessary.

- Design your poster as if you were designing for a professional publication. Be consistent with your layout, color choices, fonts and sizes.

- All text of your poster should be *at least* 24 font size and an easy-to-read font style (e.g. Arial or Verdana). Anything smaller is too difficult to read.

- Remember the “KISS Principle”: Keep It Simple, Stupid! In succinct, brief, jargon-free terms, your poster must explain: 1) the scientific problem in mind (what’s the question?), 2) its significance (why should we care?), 3) how your particular experiment addresses the problem (what’s your strategy?), 4) the experiments performed (what did you actually do?), 5) the results obtained (what did you actually find?), 6) the conclusions (what do you think it all means?), and, optionally, 7) caveats (any reservations?) and/or 8) future prospects (where do you go from here?).

- What is the number one mistake made in poster presentations? Too much information! Try to keep your poster to the point and and clear. You can always include more information in your handout or on a website.

- << Previous: Examples

- Next: Visualizations & images >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 12:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/poster

NCURA.edu | Contact Us |

- Registration Pricing

- Bulk Registration Packages

- Conference and Pre-Conference Workshop Cancellation Policy

- A Personal Welcome

- About the Conference

- Pre-Conference Workshops

- Certificate Program

- CPE/CEU Information

Guide to Writing A Poster Abstract

- Exhibitor Registration

Poster abstracts submitted to NCURA should serve as the initial report of knowledge, experience, or best practices in the field of research Administration. Submissions are evaluated by a review committee.

A well-written abstract is more likely to be considered as a finalist and, ultimately, for a recognition award. To expedite the review process, to assure effective communication, and to elevate the work toward the recognition award following, the following general suggestions will be helpful in submitting your abstract and description.

General suggestions

- Check for proper spelling and grammar.

- Use a standard typeface, such as Times Roman with a font size of 12.

- It is important to keep nonstandard abbreviations/acronyms to a minimum, to allow for readability and understanding.

- Do not include tables, figures, or graphs in the abstract. Such content is appropriate for the poster.

- Abstract should be 250 words or less and should summarize the overall objectives being presented in the poster. This can be included in bullet point format if preferred.

- The application should include a detailed description of poster make up itself and include the outcomes to be presented. Limit to 500 words (use the less=more concept).

- Try to organize the abstract with the following headings where appropriate, as explained below; purpose, methods, results, conclusions.

The abstract title conveys the content/subject of the poster. The title may be written as a question or the title may be written to suggest the conclusions, if appropriate. A short concise title may more easily catch a reader’s attention. Try to not use abbreviations or acronyms in titles.

The introductory sentence(s) may be stated as a hypothesis, a purpose, an objective, or as current evidence for a finding. Hypothesis is a supposition or conjecture used as a basis for further investigations. Purpose is a statement of the reason for conducting a project or reporting on a program, process or activity. Objective is the result that the author is trying to achieve by conducting a project, program, process or activity.

Briefly describe the methods of the project to define the data or population, outcome variables, and analytic techniques, as well as data collection procedures and frequencies. A description of statistical methods used may be included if appropriate.

The results should be stated succinctly to support only the purpose, objectives, hypothesis, or conclusions.

Conclusions

The conclusion(s) should highlight the impact of the project, and follow the methods and results in a logical fashion. This section should not restate results. Rather, the utility of the results and their potential role in the management of the project should be emphasized. New information or conclusions not supported by data in the results section should be avoided.

Important note

Poster program finalists are determined following evaluation of each actual poster by the review committee. Finalists will be notified by email no later than June 25th.

CONFERENCE PROGRAM

Registration information, workshop information, registration options, frequently asked questions, exhibitor information.

USF St. Petersburg Nelson Poynter Library will be closed on Monday, Dec 12, 2022 for the USF Libraries In-Service Day event. Operations will resume on Tuesday, Dec 13, 2022

Due to severe weather, the USF St. Petersburg Library will remain closed on Thursday, August 31st and reopen on Friday, September 1st.. For information concerning the libraries on the Tampa and Sarasota-Manatee campuses and the Shimberg Health Sciences Library , please visit their webpages. Students and faculty can visit www.usf.edu/news For official USF News regarding the weather and other closures.