Animal Rights Essay: Topics, Outline, & Writing Tips

- 🐇 Animal Rights Essay: the Basics

- 💡 Animal Rights Essay Topics

- 📑 Outlining Your Essay

- ✍️ Sample Essay (200 Words)

🔗 References

🐇 animal rights essay: what is it about.

Animal rights supporters advocate for the idea that animals should have the same freedom to live as they wish, just as humans do. They should not be exploited or used in meat , fur, and other production. At long last, we should distinguish animals from inanimate objects and resources like coal, timber, or oil.

Interdisciplinary research has shown that animals are emotional and sensitive, just like we are.

Their array of emotions includes joy, happiness, embarrassment, resentment, jealousy, anger, love, compassion, respect, disgust, despair, and even grief.

However, animal rights legislation does not extend human rights to animals. It establishes their right to have their fundamental needs and interests respected while people decide how to treat them. This right changes the status of animals from being property to being legal entities.

The statement may sound strange until we recall that churches , banks, and universities are also legal entities. Their interests are legally protected by law. Then why do we disregard the feelings of animals , which are not inanimate institutions? Several federal laws protect them from human interference.

But the following statements are only some of the rules that could one day protect animal rights in full:

- Animals should not be killed by hunting.

- Animals’ habitats should allow them to live in freedom.

- Animals should not be bred for sale or any other purpose.

- Animals should not be used for food by industries or households.

Most arguments against the adoption of similar laws are linked to money concerns. Animal exploitation has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry. The lives of many private farmers depend on meat production, and most people prefer not to change the comfortable status quo.

Animal Rights Argumentative Essay

An animal rights argumentative essay should tackle a problematic issue that people have widely discussed. While choosing ideas for the assignment, opt for the most debatable topics.

Here is a brief list of argumentative essay prompts on animal rights:

- The pros and cons of animal rights.

- Can humanity exist without meat production?

- Do animals have souls?

- Should society become vegan to protect animal rights?

As you see, these questions could raise controversy between interlocutors. Your purpose is to take a side and give several arguments in its support. Then you’ll have to state a counterargument to your opinion and explain why it is incorrect.

Animal Rights Persuasive Essay

An animal rights persuasive essay should clearly state your opinion on the topic without analyzing different points of view. Still, the purpose of your article is to persuade the reader that your position is not only reasonable but the only correct one. For this purpose, select topics relating to your opinion or formulated in questionary form.

For example:

- What is your idea about wearing fur?

- Do you think people would ever ban animal exploitation ?

- Is having pets a harmful practice?

- Animal factories hinder the development of civilization .

💡 53 Animal Rights Essay Topics

- Animal rights have been suppressed for ages because people disregard their mental abilities .

- Cosmetic and medical animal testing .

- Laws preventing unnecessary suffering of animals mean that there is some necessary suffering.

- Red fluorescent protein transgenic dogs experiment .

- Do you believe animals should have legal rights?

- Genetically modified animals and implications .

- Why is animal welfare important?

- Neutering animals to prevent overpopulation: Pros and cons.

- Animal testing: Arguments for and against .

- What is our impact on marine life ?

- Some animals cannot stay wild .

- Animal testing for medical purposes .

- We are not the ones to choose which species to preserve.

- Pavlov’s dog experiment .

- Keeping dogs chained outdoors is animal neglect.

- The use of animals for research .

- Animal dissection as a learning tool: Alternatives?

- More people beat their pets than we think.

- Duties to non-human animals .

- If we do not control the population of some animals, they will control ours.

- Animals in entertainment: Not entertaining at all.

- Animals in research, education, and teaching.

- Which non-animal production endangers the species?

- Is animal testing really needed?

- Why do some people think that buying a new pet is cheaper than paying for medical treatment of the old one?

- Animal experiments: benefits, ethics, and defenders.

- Can people still be carnivorous if they stop eating animals?

- Animal testing role .

- Marine aquariums and zoos are animal prisons.

- Animal experimentation: justification arguments .

- What would happen if we replace animals in circuses with people, keeping the same living conditions?

- The ethics of animal use in scientific research .

- Animal sports: Relics of the past.

- Animal testing ban: counterargument and rebuttal .

- Denial to purchase animal-tested cosmetics will not change anything.

- Animal research, its ineffectiveness and amorality .

- Animal rights protection based on their intellect level: It tells a lot about humanity.

- Debates of using animals in scientific analysis .

- How can we ban tests on rats and kill them in our homes at the same time?

- Animal testing in experiments .

- What is the level of tissue engineering development in leather and meat production?

- Equal consideration of interests to non-human animals .

- Animals should not have to be our servants .

- Zoos as an example of humans’ immorality .

- We should feed wild animals to help them survive.

- Animal testing in biomedical research .

- Abolitionism: The right not to be owned.

- Do you support the Prima facie rights theory?

- Psychologist perspective on research involving animal and human subjects .

- Ecofeminism: What is the link between animals’ and women’s rights ?

- No philosophy could rationalize cruelty against animals.

- Qualities that humans and animals share .

- Ancient Buddhist societies and vegetarianism: A research paper.

Need more ideas? You are welcome to use our free research topic generator !

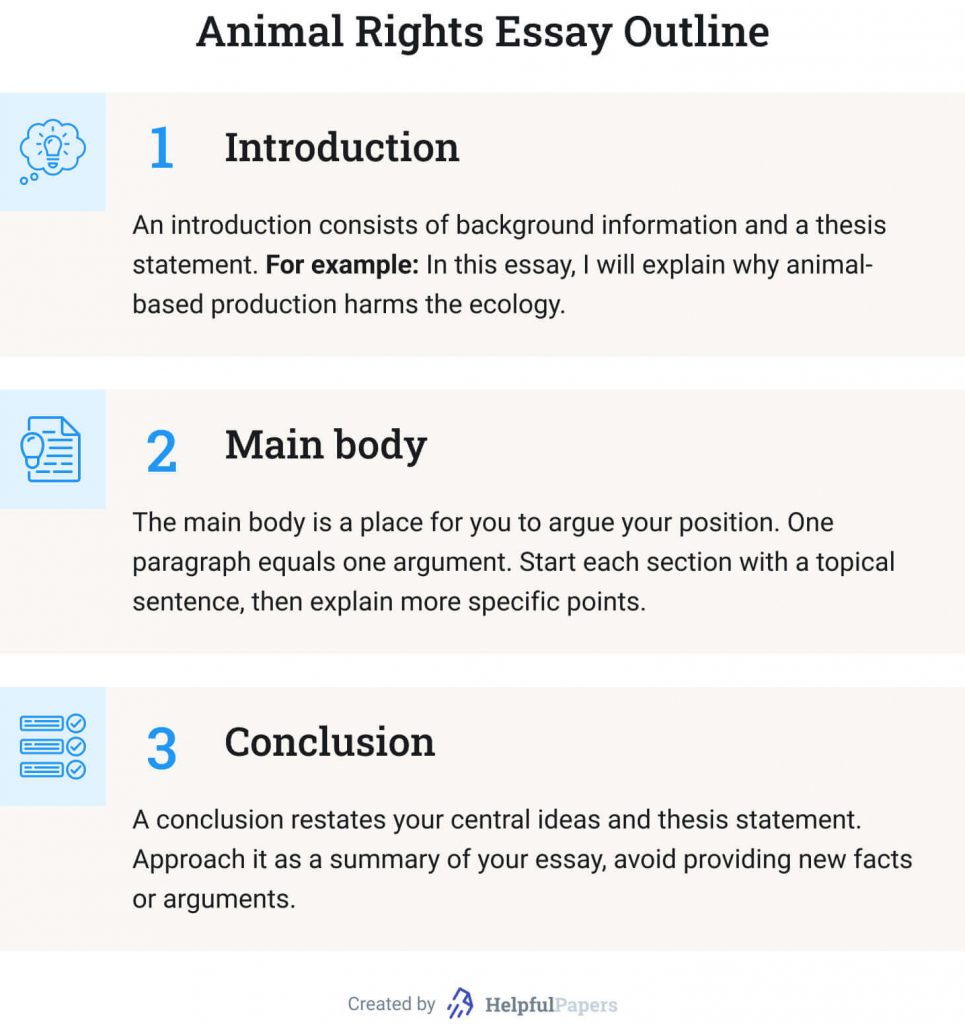

📑 Animal Rights Essay Outline

An animal rights essay should be constructed as a standard 5-paragraph essay (if not required otherwise in the assignment). The three following sections provide a comprehensive outline.

Animal Rights Essay: Introduction

An introduction consists of:

- Background information,

- A thesis statement .

In other words, here you need to explain why you decided to write about the given topic and which position you will take. The background part should comprise a couple of sentences highlighting the topicality of the issue. The thesis statement expresses your plans in the essay.

For example: In this essay, I will explain why animal-based production harms the ecology.

Animal Rights Essay: Main Body

The main body is a place for you to argue your position . One paragraph equals one argument. In informative essays, replace argumentation with facts.

Start each section with a topical sentence consisting of a general truth. Then give some explanation and more specific points. By the way, at the end of this article, you’ll find a bonus! It is a priceless selection of statistics and facts about animal rights.

Animal Rights Essay: Conclusion

A conclusion restates your central ideas and thesis statement. Approach it as a summary of your essay, avoid providing new facts or arguments.

✍️ Animal Rights Essay Example (200 Words)

Why is animal welfare important? The term “animal welfare” evokes the pictures of happy cows from a milk advertisement. But the reality has nothing to do with these bright videos. Humane treatment of animals is a relative concept. This essay explains why animal welfare is important, despite that it does not prevent farms from killing or confining animals.

The best way to approach animal welfare is by thinking of it as a temporary measure. We all agree that the current state of the economy does not allow humanity to abandon animal-based production. Moreover, such quick decisions could make farm animals suffer even more. But ensuring the minimum possible pain is the best solution as of the moment.

The current legislation on animal welfare is far from perfect. The Animal Welfare Act of 1966 prevents cruelty against animals in labs and zoos. Meanwhile, the majority of suffering animals do not fall under its purview. For example, it says nothing about the vivisection of rats and mice for educational and research purposes, although the procedure is extremely painful for the creature. Neither does it protect farm animals.

Unfortunately, the principles of animal welfare leave too much room for interpretation. Animals should be free from fear and stress, but how can we measure that? They should be allowed to engage in natural behaviors, but no confined space would let them do so. Thus, the legislation is imprecise.

The problem of animal welfare is almost unresolvable because it is a temporary measure to prevent any suffering of domesticated animals. It has its drawbacks but allows us to ensure at least some comfort for those we unjustifiably use for food. They have the same right to live on this planet as we do, and animal farming will be stopped one day.

📊 Bonus: Statistics & Facts for Your Animal Rights Essay Introduction

Improve the quality of your essay on animal rights by working in the following statistics and facts about animals.

- According to USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service , about 4.6 billion animals — including hogs, sheep, cattle, chickens, ducks, lambs, and turkey — were killed and used for food in the United States last year (2015).

- People in the U.S. kill over 100 million animals for laboratory experiments every year, according to PETA .

- More than 40 million animals are killed for fur worldwide every year. About 30 million animals are raised and killed on fur farms, and nearly 10 million wild animals are hunted and killed for the same reasons — for their valuable fur.

- According to a report by In Defense of Animals , hunters kill more than 200 million animals in the United States yearly.

- The Humane Society of the United States notes that a huge number of cats and dogs — between 3 and 4 million each year — are killed in the country’s animal shelters. Sadly, this number does not include dogs or cats killed in animal cruelty cases.

- According to the ASPCA , about 7.6 million companion animals enter animal shelters in the United States yearly. Of this number, 3.9 Mil of dogs, and 3.4 Mil of cats.

- About 2.7 million animals are euthanized in shelters every year (1.4 million cats and 1.2 million dogs).

- About 2.7 million shelter animals are adopted every year (1.3 million cats and 1.4 million dogs).

- In total, there are approximately 70-80 million dogs and 74-96 million cats living as pets in the United States.

- It’s impossible to determine the exact number of stray cats and dogs living in the United States, but the number of cats is estimated to be up to 70 million.

- Many stray cats and dogs were once family pets — but they were not kept securely indoors or provided with proper identification.

Each essay on animals rights makes humanity closer to a better and more civilized world. Please share any thoughts and experience in creating such texts in the comments below. And if you would like to hear how your essay would sound in someone’s mind, use our Text-To-Speech tool .

- Why Animal Rights? | PETA

- Animal Rights – Encyclopedia Britannica

- Animal ethics: Animal rights – BBC

- Animal Health and Welfare – National Agricultural Library

- The Top 10 Animal Rights Issues – Treehugger

- Animal welfare – European Commission

Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Film analysis: example, format, and outline + topics & prompts.

Animal Rights: Definition, Issues, and Examples

Animal rights advocates believe that non-human animals should be free to live as they wish, without being used, exploited, or otherwise interfered with by humans.

T he idea of giving rights to animals has long been contentious, but a deeper look into the reasoning behind the philosophy reveals ideas that aren’t all that radical. Animal rights advocates want to distinguish animals from inanimate objects, as they are so often considered by exploitative industries and the law.

The animal rights movement strives to make the public aware of the fact that animals are sensitive, emotional , and intelligent beings who deserve dignity and respect. But first, it’s important to understand what the term "animal rights" really means.

What are animal rights?

Animal rights are moral principles grounded in the belief that non-human animals deserve the ability to live as they wish, without being subjected to the desires of human beings. At the core of animal rights is autonomy, which is another way of saying choice . In many countries, human rights are enshrined to protect certain freedoms, such as the right to expression, freedom from torture, and access to democracy. Of course, these choices are constrained depending on social locations like race, class, and gender, but generally speaking, human rights safeguard the basic tenets of what makes human lives worth living. Animal rights aim to do something similar, only for non-human animals.

Animal rights come into direct opposition with animal exploitation, which includes animals used by humans for a variety of reasons, be it for food , as experimental objects, or even pets. Animal rights can also be violated when it comes to human destruction of animal habitats . This negatively impacts the ability of animals to lead full lives of their choosing.

Do animals have rights?

Very few countries have enshrined animal rights into law. However, the US and the UK do have some basic protections and guidelines for how animals can be treated.

The UK Sentience Bill

In 2021, the United Kingdom's House of Commons introduced the Animal Sentience Bill . If passed, this bill would enshrine into law that animals are, in fact, sentient beings, and they deserve humane treatment at the hands of humans. While this law would not afford animals full autonomy, it would be a watershed in the movement to protect animals—officially recognizing their capacity to feel and to suffer, and distinguishing them from inanimate objects.

The US Animal Welfare Act

In 1966, the United States passed the Animal Welfare Act . While it is the biggest federal legislation addressing the treatment of animals to date, its scope is fairly narrow—the law excludes many species, including farmed animals , from its protections. The law does establish some basic guidelines for the sale, transport, and handling of dogs, cats, rabbits, nonhuman primates, guinea pigs, and hamsters. It also protects the psychological welfare of animals who are used in lab experiments, and prohibits the violent practices of dogfighting and cockfighting. Again, this law does not recognize the rights and autonomy of animals—or even their ability to feel pain and suffer—but it does afford non-human animals some basic welfare protections .

What are some examples of animal rights?

While few laws currently exist in the UK or US that recognize or protect animals' rights to enjoy lives free from human interference, the following is a list of examples of animal rights that could one day be enacted:

- Animals may not be used for food.

- Animals may not be hunted.

- The habitats of animals must be protected to allow them to live according to their choosing.

- Animals may not be bred.

What's the difference between animal welfare and animal rights?

Animal rights philosophy is based on the idea that animals should not be used by people for any reason, and that animal rights should protect their interests the way human rights protect people. Animal welfare , on the other hand, is a set of practices designed to govern the treatment of animals who are being dominated by humans, whether for food, research, or entertainment.

Do animals need rights? Pros and cons

The idea of giving animals rights tends to be contentious, given how embedded animal products are within societies such as the United States. Some people, including animal activists, believe in an all-or-nothing approach, where animal rights must be legally enshrined and animals totally liberated from all exploitation. On the other end of the spectrum are people whose livelihoods depend upon animal-based industries. Below are some arguments both in favor of and opposing animal rights.

Arguments in favor of animal rights

Should the rights of animals be recognized, animal exploitative industries would disappear, as would the host of environmental problems they cause, including water pollution, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and deforestation.

Halting the widespread use of animals would also eliminate the systematic cruelty and denial of choice that animal industries perpetuate. The physical and psychological pain endured by animals in places like factory farms has reached a point many consider to be unacceptable , to say the least. Animals are mutilated by humans in several different ways, including castrations, dehorning, and cutting off various body parts, usually without the use of anesthetic.

“ Many species never see the outdoors except on their way to the slaughterhouse.

As their name suggests, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) pack vast numbers of animals in cramped conditions, often forcing animals to perpetually stand in their own waste. Many species—including chickens, cows, and pigs—never see the outdoors except on their way to the slaughterhouse. Recognizing animal rights would necessitate stopping this mistreatment for good.

Arguments against animal rights

Most arguments against animal rights can be traced back to money, because animal exploitation is big business. Factory farming for animal products is a multi-billion-dollar industry. JBS, the world’s largest meatpacker, posted $9 billion in revenue for the third quarter of 2020 alone.

A lesser-known, yet also massive, industry is that which supplies animals for laboratories. The US market for lab rats (who are far less popular than mice for experiments) was valued at over $412 million in 2016. Big industrial producers of animals and animal products have enough political clout to influence legislation—including passing laws making it illegal to document farm conditions—and to benefit from government subsidies.

Many people depend upon animal exploitation for work. On factory farms, relatively small numbers of people can manage vast herds or flocks of animals, thanks to mechanization and other industrial farming techniques. Unfortunately, jobs in industrial meatpacking facilities are also known to be some of the most dangerous in the US. Smaller farmers coming from multi-generational farming families more directly depend upon using animals to make a living and tend to follow welfare standards more judiciously. However, smaller farms have been decreasing in number, due to the proliferation of factory farms against which they often cannot compete.

Although people may lose money or jobs in the transition to animal alternatives, new jobs can be created in the alternative protein sector and other plant-based industries.

When did the animal rights movement begin in the US?

The modern day animal rights movement in the United States includes thousands of individuals and a multitude of groups who advocate for animals in a variety of ways—from lobbying legislators to support animal rights laws, to rescuing animals from situations of abuse and neglect. While individuals throughout history have believed in and fought for animal rights, we can trace back the modern, US-based animal rights movement to the founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in 1866. The group's founder, Henry Burgh , believed that animals are "entitled to kind and respectful treatment at the hands of humans and must be protected under the law." The organization worked with the New York City government to pass and enforce anti-cruelty laws that prevented the abuse of carthorses and provided care for injured horses. Since then, the ASPCA has expanded its advocacy across different non-human animal species—including farmed animals—and many more animal protection groups have sprung up, both locally and nationwide. Currently, there are over 40,000 non-profit organizations identified as animal groups in the US.

Why are animal rights important?

Animal rights are important because they represent a set of beliefs that counteract inaccurate yet long-held assumptions that animals are nothing more than mindless machines—beliefs popularized by western philosopher Rene Descartes in the 17th century. The perception of animals as being unthinking, unfeeling beings justified using them for human desires, resulting in today’s world where farmed mammals outnumber those in the wild, and the majority of these farmed animals are forced to endure harsh conditions on factory farms.

“ Farmed mammals outnumber those in the wild.

But the science is increasingly clear: The animals we eat ( pigs, chickens, cows ), the animals we use in laboratories ( mice and rats ), the animals who provide us with clothing , and those whose backs we ride upon have all been found to possess more cognitive complexity, emotions, and overall sophistication than has long been believed. This sophistication renders animals more susceptible not only to physical pain but also to the psychological impacts caused by the habitual denial of choice. Awareness of their own subjugation forms sufficient reasoning to rethink the ways animals are treated in western societies.

The consequences of animal rights

Currently, laws in the US and UK are geared toward shielding animals from cruelty, not giving them the same freedom of choice that humans have. (Even these laws are sorely lacking, as they fail to protect livestock and laboratory animals.) However, the animal rights movement can still have real-world consequences. Calls for animal liberation from places like factory farms can raise public awareness of the poor living conditions and welfare violations these facilities perpetuate, sometimes resulting in stronger protections, higher welfare standards , and decreasing consumer demand. Each of these outcomes carries economic consequences for producers, as typically it is more expensive for factory farms to provide better living conditions such as more space, or using fewer growth hormones which can result in lower production yields.

Of course, should the animal rights movement achieve its goals , society would look much different than it does today. If people consume more alternative sources of protein, such as plant-based or lab-grown meat, the global environment would be far less impacted. Clothing would be made without leather or other animal products; alternative sources, such as pineapple leather created from waste products from the pineapple industry, could replace toxic tanneries. The fur industry is being increasingly shunned, with fashion labels rejecting fur in favor of faux materials. Ocean ecosystems would be able to recover, replenishing fish populations and seafloor habitats. Today these are razed by bottom trawling fishing, resulting in the clear-cutting of corals that can be thousands of years old .

How you can advocate for animals

A world in which animals are free from human exploitation still seems far off, but we can make choices that create a kinder world for animals, every day. We can start by leaving animals off our plate in favor of plant-based alternatives—a choice that recognizes animals as the sentient beings that they are, and not products for consumption.

When we come together, we can also fight for better protections for animals in the US and around the world. There's a robust movement to hold corporations accountability and end the cruelty of factory farming—an industry which causes immense amount of suffering for billions of animals. If you want to help end this suffering and spread compassion for animals, join our community of online animal activists and take action .

More like this

What Is Animal Welfare and Why Is It Important?

Though critics argue that advocating for animal welfare only cements animals’ exploitation in laboratories, on farms, and in other industrial situations, strengthening welfare standards makes these animals' lives more bearable.

The Ethical Case for Welfare Reform

Industry welfare commitments are good for animals. Here’s why.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Oxford Journal of Legal Studies

- About University of Oxford Faculty of Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction: the need for legal animal rights theory, 2. can animals have legal rights, 3. do animals have (simple) legal rights, 4. should animals have (fundamental) legal rights, 5. conclusion.

- < Previous

Towards a Theory of Legal Animal Rights: Simple and Fundamental Rights

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Saskia Stucki, Towards a Theory of Legal Animal Rights: Simple and Fundamental Rights, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies , Volume 40, Issue 3, Autumn 2020, Pages 533–560, https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

With legal animal rights on the horizon, there is a need for a more systematic theorisation of animal rights as legal rights. This article addresses conceptual, doctrinal and normative issues relating to the nature and foundations of legal animal rights by examining three key questions: can, do and should animals have legal rights? It will show that animals are conceptually possible candidates for rights ascriptions. Moreover, certain ‘animal welfare rights’ could arguably be extracted from existing animal welfare laws, even though these are currently imperfect and weak legal rights at best. Finally, this article introduces the new conceptual vocabulary of simple and fundamental animal rights, in order to distinguish the weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law from the kind of strong legal rights that animals ought to have as a matter of future law.

Legal animal rights are on the horizon, and there is a need for a legal theory of animal rights—that is, a theory of animal rights as legal rights. While there is a diverse body of moral and political theories of animal rights, 1 the nature and conceptual foundations of legal animal rights remain remarkably underexplored. As yet, only few and fragmented legal analyses of isolated aspects of animal rights exist. 2 Other than that, most legal writing in this field operates with a hazily assumed, rudimentary and undifferentiated conception of animal rights—one largely informed by extralegal notions of moral animal rights—which tends to obscure rather than illuminate the distinctive nature and features of legal animal rights. 3 A more systematic and nuanced theorisation of legal animal rights is, however, necessary and overdue for two reasons: first, a gradual turn to legal rights in animal rights discourse; and, secondly, the incipient emergence of legal animal rights.

First, while animal rights have originally been framed as moral rights, they are increasingly articulated as potential legal rights. That is, animals’ moral rights are asserted in an ‘ought to be legal rights’-sense (or ‘manifesto sense’) 4 that demands legal institutionalisation and refers to the corresponding legal rights which animals should ideally have. 5 A salient reason for transforming moral into legal animal rights is that purely moral rights (which exist prior to and independently of legal validation) do not provide animals with sufficient practical protection, whereas legally recognised rights would be reinforced by the law’s more stringent protection and enforcement mechanisms. 6 With a view to their (potential) juridification, it seems advisable to rethink and reconstruct animal rights as specifically legal rights, rather than simply importing moral animal rights into the legal domain. 7

Secondly, and adding urgency to the need for theorisation, legal animal rights are beginning to emerge from existing law. Recently, a few pioneering courts have embarked on a path of judicial creation of animal rights, arriving at them either through a rights-based interpretation of animal welfare legislation or a dynamic interpretation of constitutional (human) rights. Most notably, the Supreme Court of India has extracted a range of animal rights from the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act and, by reading them in the light of the Constitution, elevated those statutory rights to the status of fundamental rights. 8 Furthermore, courts in Argentina 9 and Colombia 10 have extended the fundamental right of habeas corpus , along with the underlying right to liberty, to captive animals. 11 These (so far isolated) acts of judicial recognition of animal rights may be read as early manifestations of an incipient formation of legal animal rights. Against this backdrop, there is a pressing practical need for legal animal rights theory, in order to explain and guide the as yet still nascent—and somewhat haphazard—evolution of legal animal rights.

This article seeks to take the first steps towards building a more systematic and nuanced theory of legal animal rights. Navigating the existing theoretical patchwork, the article revisits and connects relevant themes that have so far been addressed only in a scattered or cursory manner, and consolidates them into an overarching framework for legal animal rights. Moreover, tackling the well-known problem of ambiguity and obscurity involved in the generally vague, inconsistent and undifferentiated use of the umbrella term ‘animal rights’, this article brings analytical clarity into the debate by disentangling and unveiling different meanings and facets of legal animal rights. 12 To this end, the analysis identifies and separates three relevant sets of issues: (i) conceptual issues concerning the nature and foundations of legal animal rights, and, more generally, whether animals are the kind of beings who can potentially hold legal rights; (ii) doctrinal issues pertaining to existing animal welfare law and whether it confers some legal rights on animals—and, if so, what kind of rights; and (iii) normative issues as to why and what kind of legal rights animals ought ideally to have as a matter of future law. These thematic clusters will be addressed through three simple yet key questions: can , do and should animals have legal rights?

Section 2 will show that it is conceptually possible for animals to hold legal rights, and will clarify the formal structure and normative grounds of legal animal rights. Moreover, as section 3 will demonstrate, unwritten animal rights could arguably be extracted from existing animal welfare laws, even though such ‘animal welfare rights’ are currently imperfect and weak legal rights at best. In order to distinguish between these weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law and the kind of strong legal rights that animals ought to have potentially or ideally, the new conceptual categories of ‘ simple animal rights’ and ‘ fundamental animal rights’ will be introduced. Finally, section 4 will explore a range of functional reasons why animals need such strong, fundamental rights as a matter of future law.

As a preliminary matter, it seems necessary to first address the conceptual issue whether animals potentially can have legal rights, irrespective of doctrinal and normative issues as to whether animals do in fact have, or should have, legal rights. Whether animals are possible or potential right holders—that is, the kind of beings to whom legal rights can be ascribed ‘without conceptual absurdity’ 13 —must be determined based on the general nature of rights, which is typically characterised in terms of the structure (or form) and grounds (or ultimate purpose) of rights. 14 Looking at the idea of animal rights through the lens of general rights theories helps clarify the conceptual foundations of legal animal rights by identifying their possible forms and grounds. The first subsection (A) focusses on two particular forms of conceptually basic rights—claims and liberties—and examines their structural compatibility with animal rights. The second subsection (B) considers the two main competing theories of rights—the will theory and interest theory—and whether, and on what grounds, they can accommodate animals as potential right holders.

A. The Structure of Legal Animal Rights

The formal structure of rights is generally explicated based on the Hohfeldian typology of rights. 15 Hohfeld famously noted that the generic term ‘right’ tends to be used indiscriminately to cover ‘any sort of legal advantage’, and distinguished four different types of conceptually basic rights: claims (rights stricto sensu ), liberties, powers and immunities. 16 In the following, I will show on the basis of first-order rights 17 —claims and liberties—that legal animal rights are structurally possible, and what such legal relations would consist of. 18

(i) Animal claim rights

To have a right in the strictest sense is ‘to have a claim to something and against someone’, the claim right necessarily corresponding with that person’s correlative duty towards the right holder to do or not to do something. 19 This type of right would take the form of animals holding a claim to something against, for example, humans or the state who bear correlative duties to refrain from or perform certain actions. Such legal animal rights could be either negative rights (correlative to negative duties) to non-interference or positive rights (correlative to positive duties) to the provision of some good or service. 20 The structure of claim rights seems especially suitable for animals, because these are passive rights that concern the conduct of others (the duty bearers) and are simply enjoyed rather than exercised by the right holder. 21 Claim rights would therefore assign to animals a purely passive position that is specified by the presence and performance of others’ duties towards animals, and would not require any actions by the animals themselves.

(ii) Animal liberties

Liberties, by contrast, are active rights that concern the right holder’s own conduct. A liberty to engage in or refrain from a certain action is one’s freedom of any contrary duty towards another to eschew or undertake that action, correlative to the no right of another. 22 On the face of it, the structure of liberties appears to lend itself to animal rights. A liberty right would indicate that an animal is free to engage in or avoid certain behaviours, in the sense of being free from a specific duty to do otherwise. Yet, an obvious objection is that animals are generally incapable of having any legal duties. 23 Given that animals are inevitably in a constant state of ‘no duty’ and thus ‘liberty’, 24 this seems to render the notion of liberty rights somewhat pointless and redundant in the case of animals, as it would do nothing more than affirm an already and invariably existing natural condition of dutylessness. However, this sort of ‘natural liberty’ is, in and of itself, only a naked liberty, one wholly unprotected against interferences by others. 25 That is, while animals may have the ‘natural liberty’ of, for example, freedom of movement in the sense of not having (and not being capable of having) a duty not to move around, others do not have a duty vis-à-vis the animals not to interfere with the exercise of this liberty by, for example, capturing and caging them.

The added value of turning the ‘natural liberties’ of animals into liberty rights thus lies in the act of transforming unprotected, naked liberties into protected, vested liberties that are shielded from certain modes of interference. Indeed, it seems sensible to think of ‘natural liberties’ as constituting legal rights only when embedded in a ‘protective perimeter’ of claim rights and correlative duties within which such liberties may meaningfully exist and be exercised. 26 This protective perimeter consists of some general duties (arising not from the liberty right itself, but from other claim rights, such as the right to life and physical integrity) not to engage in ‘at least the cruder forms of interference’, like physical assault or killing, which will preclude most forms of effective interference. 27 Moreover, liberties may be fortified by specific claim rights and correlative duties strictly designed to protect a particular liberty, such as if the state had a (negative) duty not to build highways that cut across wildlife habitat, or a (positive) duty to build wildlife corridors for such highways, in order to facilitate safe and effective freedom of movement for the animals who live in these fragmented habitats.

(iii) Animal rights and duties: correlativity and reciprocity

Lastly, some remarks on the relation between animal rights and duties seem in order. Some commentators hold that animals are unable to possess legal rights based on the influential idea that the capacity for holding rights is inextricably linked with the capacity for bearing duties. 28 Insofar as animals are not capable of bearing legal duties in any meaningful sense, it follows that animals cannot have legal (claim) rights against other animals, given that those other animals would be incapable of holding the correlative duties. But does this disqualify animals from having legal rights altogether, for instance, against legally competent humans or the state?

While duties are a key component of (first-order) rights—with claim rights necessarily implying the presence of a legal duty in others and liberties necessarily implying the absence of a legal duty in the right holder 29 —neither of them logically entails that the right holder bear duties herself . As Kramer aptly puts it:

Except in the very unusual circumstances where someone holds a right against himself, X’s possession of a legal right does not entail X’s bearing of a legal duty; rather, it entails the bearing of a legal duty by somebody else. 30

This underscores an important distinction between the conceptually axiomatic correlativity of rights and duties—the notion that every claim right necessarily implies a duty—and the idea of a reciprocity of rights and duties—the notion that (the capacity for) right holding is conditioned on (the capacity for) duty bearing. While correlativity refers to an existential nexus between a right and a duty held by separate persons within one and the same legal relation , reciprocity posits a normative nexus between the right holding and duty bearing of one and the same person within separate, logically unrelated legal relations.

The claim that the capacity for right holding is somehow contingent on the right holder’s (logically unrelated) capacity for duty bearing is thus, as Kramer puts it, ‘straightforwardly false’ from a Hohfeldian point of view. 31 Nevertheless, there may be other, normative reasons (notably underpinned by social contract theory) for asserting that the class of appropriate right holders should be limited to those entities that, in addition to being structurally possible right holders, are also capable of reciprocating, that is, of being their duty bearers’ duty bearers. 32 However, such a narrow contractarian framing of right holding should be rejected, not least because it misses the current legal reality. 33 With a view to legally incompetent humans (eg infants and the mentally incapacitated), contemporary legal systems have manifestly cut the connection between right holding and the capacity for duty bearing. 34 As Wenar notes, the ‘class of potential right holders has expanded to include duty-less entities’. 35 Similarly, it would be neither conceptually nor legally apposite to infer from the mere fact that animals do not belong to the class of possible duty bearers that they cannot belong to the class of possible right holders. 36

B. The Grounds of Legal Animal Rights

While Hohfeld’s analytical framework is useful to outline the possible forms and composition of legal animal rights, Kelch rightly points out that it remains agnostic as to the normative grounds of potential animal rights. 37 In this respect, the two dominant theories of rights advance vastly differing accounts of the ultimate purpose of rights and who can potentially have them. 38 Whereas the idea of animal rights does not resonate well with the will theory, the interest theory quite readily provides a conceptual home for it.

(i) Will theory

According to the will theory, the ultimate purpose of rights is to promote and protect some aspect of an individual’s autonomy and self-realisation. A legal right is essentially a ‘legally respected choice’, and the right holder a ‘small scale sovereign’ whose exercise of choice is facilitated by giving her discretionary ‘legal powers of control’ over others’ duties. 39 The class of potential right holders thus includes only those entities that possess agency and legal competence, which effectively rules out the possibility of animals as right holders, insofar as they lack the sort or degree of agency necessary for the will-theory conception of rights. 40

However, the fact that animals are not potential right holders under the will theory does not necessarily mean that animals cannot have legal rights altogether. The will theory has attracted abundant criticism for its under-inclusiveness as regards both the class of possible right holders 41 and the types of rights it can plausibly account for, and thus seems to advance too narrow a conception of rights for it to provide a theoretical foundation for all rights. 42 In particular, it may be noted that the kinds of rights typically contemplated as animal rights are precisely of the sort that generally exceed the explanatory power of the will theory, namely inalienable, 43 passive, 44 public-law 45 rights that protect basic aspects of animals’ (partially historically and socially mediated) vulnerable corporeal existence. 46 Such rights, then, are best explained on an interest-theoretical basis.

(ii) Interest theory

Animal rights theories most commonly ground animal rights in animal interests, and thus naturally gravitate to the interest theory of rights. 47 According to the interest theory, the ultimate purpose of rights is the protection and advancement of some aspect(s) of an individual’s well-being and interests. 48 Legal rights are essentially ‘legally-protected interests’ that are of special importance and concern. 49 With its emphasis on well-being rather than on agency, the interest theory seems more open to the possibility of animal rights from the outset. Indeed, as regards the class of possible right holders, the interest theory does little conceptual filtering beyond requiring that right holders be capable of having interests. 50 Given that, depending on the underlying definition of ‘interest’, this may cover all animals, plants and, according to some, even inanimate objects, the fairly modest and potentially over-inclusive conceptual criterion of ‘having interests’ is typically complemented by the additional, more restrictive moral criterion of ‘having moral status’. 51 Pursuant to this limitation, not just any being capable of having interests can have rights, but only those whose well-being is not merely of instrumental, but of intrinsic or ‘ultimate value’. 52

Accordingly, under the interest theory, two conditions must be met for animals to qualify as potential right holders: (i) animals must have interests, (ii) the protection of which is required not merely for ulterior reasons, but for the animals’ own sake, because their well-being is intrinsically valuable. Now, whether animals are capable of having interests in the sense relevant to having rights and whether they have moral status in the sense of inherent or ultimate value is still subject to debate. For example, some have denied that animals possess interests based on an understanding of interests as wants and desires that require complex cognitive abilities such as having beliefs and language. 53 However, most interest theories opt for a broader understanding of interests in the sense of ‘being in someone’s interest’, meaning that an interest holder can be ‘made better or worse off’ and is able to benefit in some way from protective action. 54 Typically, though not invariably, the capacity for having interests in this broad sense is bound up with sentience—the capacity for conscious and subjective experiences of pain, suffering and pleasure. 55 Thus, most interest theorists quite readily accept (sentient) animals as potential right holders, that is, as the kind of beings that are capable of holding legal rights. 56

More importantly yet for legal purposes, the law already firmly rests on the recognition of (some) animals as beings who possess intrinsically valuable interests. Modern animal welfare legislation cannot be intelligibly explained other than as acknowledging that the animals it protects (i) have morally and legally relevant goods and interests, notably in their welfare, life and physical or mental integrity. 57 Moreover, it rests on an (implicit or explicit) recognition of those animals as (ii) having moral status in the sense of having intrinsic value. The underlying rationale of modern, non-anthropocentric, ethically motivated animal protection laws is the protection of animals qua animals, for their own sake, rather than for instrumental reasons. 58 Some laws go even further by directly referencing the ‘dignity’ or ‘intrinsic value’ of animals. 59

It follows that existing animal welfare laws already treat animals as intrinsically valuable holders of some legally relevant interests—and thus as precisely the sorts of beings who possess the qualities that are, under an interest theory of rights, necessary and sufficient for having rights. This, then, prompts the question whether those very laws do not only conceptually allow for potential animal rights, but might also give rise to actual legal rights for animals.

Notwithstanding that animals could have legal rights conceptually, the predominant doctrinal opinion is that, as a matter of positive law, animals do not have any, at least not in the sense of proper, legally recognised and claimable rights. 60 Yet, there is a certain inclination, especially in Anglo-American parlance, to speak—in a rather vague manner—of ‘animal rights’ as if they already exist under current animal welfare legislation. Such talk of existing animal rights is, however, rarely backed up with further substantiations of the underlying claim that animal welfare laws do in fact confer legal rights on animals. In the following, I will examine whether animals’ existing legal protections may be classified as legal rights and, if so, what kind of rights these constitute. The analysis will show (A) that implicit animal rights (hereinafter referred to as ‘animal welfare rights’) 61 can be extracted from animal welfare laws as correlatives of explicit animal welfare duties, but that this reading remains largely theoretical so far, given that such unwritten animal rights are hardly legally recognised in practice. Moreover, (B) the kind of rights derivable from animal welfare laws are currently at best imperfect and weak rights that do not provide animals with the sort of robust normative protection that is generally associated with legal rights, and typically also expected from legal animal rights qua institutionalised moral animal rights. Finally, (C) the new conceptual categories of ‘ simple animal rights’ and ‘ fundamental animal rights’ are introduced in order to distinguish, and account for the qualitative differences, between such current, imperfect, weak animal rights and potential, ideal, strong animal rights.

A. Extracting ‘Animal Welfare Rights’ from Animal Welfare Laws

(i) the simple argument from correlativity.

Existing animal welfare laws are not framed in the language of rights and do not codify any explicit animal rights. They do, however, impose on people legal duties designed to protect animals—duties that demand some behaviour that is beneficial to the welfare of animals. Some commentators contend that correlative (claim) rights are thereby conferred upon animals as the beneficiaries of such duties. 62 This view is consistent with, and, indeed, the logical conclusion of, an interest-theoretical analysis. 63 Recall that rights are essentially legally protected interests of intrinsically valuable individuals, and that a claim right is the ‘position of normative protectedness that consists in being owed a … legal duty’. 64 Under existing animal welfare laws, some goods of animals are legally protected interests in exactly this sense of ultimately valuable interests that are protected through the imposition of duties on others. However, the inference from existing animal welfare duties to the existence of correlative ‘animal welfare rights’ appears to rely on a somewhat simplistic notion of correlativity, along the lines of ‘where there is a duty there is a right’. 65 Two objections in particular may be raised against the view that beneficial duties imposed by animal welfare laws are sufficient for creating corresponding legal rights in animals.

First, not every kind of duty entails a correlative right. 66 While some duties are of an unspecific and general nature, only relational, directed duties which are owed to rather than merely regarding someone are the correlatives of (claim) rights. Closely related, not everyone who stands to benefit from the performance of another’s duty has a correlative right. According to a standard delimiting criterion, beneficial duties generate rights only in the intended beneficiaries of such duties, that is, those who are supposed to benefit from duties designed to protect their interests. 67 Yet, animal welfare duties, in a contemporary reading, are predominantly understood not as indirect duties regarding animals—duties imposed to protect, for example, an owner’s interest in her animal, public sensibilities or the moral character of humans—but as direct duties owed to the protected animals themselves. 68 Moreover, the constitutive purpose of modern animal welfare laws is to protect animals for their own sake. Animals are therefore clearly beneficiaries in a qualified sense, that is, they are not merely accidental or incidental, but the direct and intended primary beneficiaries of animal welfare duties. 69

Secondly, one may object that an analysis of animal rights as originating from intentionally beneficial duties rests on a conception of rights precisely of the sort which has the stigma of redundancy attached to it. Drawing on Hart, this would appear to cast rights as mere ‘alternative formulation of duties’ and thus ‘no more than a redundant translation of duties … into a terminology of rights’. 70 Admittedly, as MacCormick aptly puts it:

[To] rest an account of claim rights solely on the notion that they exist whenever a legal duty is imposed by a law intended to benefit assignable individuals … is to treat rights as being simply the ‘reflex’ of logically prior duties. 71

One way of responding to this redundancy problem is to reverse the logical order of rights and duties. On this account, rights are not simply created by (and thus logically posterior to) beneficial duties, but rather the converse: such duties are derived from and generated by (logically antecedent) rights. For example, according to Raz, ‘Rights are grounds of duties in others’ and thus justificationally prior to duties. 72 However, if rights are understood not just as existentially correlative, but as justificationally prior to duties, identifying intentionally beneficial animal welfare duties as the source of (logically posterior) animal rights will not suffice. In order to accommodate the view that rights are grounds of duties, the aforementioned argument from correlativity needs to be reconsidered and refined.

(ii) A qualified argument from correlativity

A refined, and reversed, argument from correlativity must show that animal rights are not merely reflexes created by animal welfare duties, but rather the grounds for such duties. In other words, positive animal welfare duties must be plausibly explained as some kind of codified reflection, or visible manifestation, of ‘invisible’ background animal rights that give rise to those duties.

This requires further clarification of the notion of a justificational priority of rights over duties. On the face of it, the idea that rights are somehow antecedent to duties appears to be at odds with the Hohfeldian correlativity axiom, which stipulates an existential nexus of mutual entailment between rights and duties—one cannot exist without the other. 73 Viewed in this light, it seems paradoxical to suggest that rights are causal for the very duties that are simultaneously constitutive of those rights—cause and effect seem to be mutually dependent. Gewirth offers a plausible explanation for this seemingly circular understanding of the relation between rights and duties. He illustrates that the ‘priority of claim rights over duties in the order of justifying purpose or final causality is not antithetical to their being correlative to each other’ by means of an analogy:

Parents are prior to their children in the order of efficient causality, yet the (past or present) existence of parents can be inferred from the existence of children, as well as conversely. Hence, the causal priority of parents to children is compatible with the two groups’ being causally as well as conceptually correlative. The case is similar with rights and duties, except that the ordering relation between them is one of final rather than efficient causality, of justifying purpose rather than bringing-into-existence. 74

Upon closer examination, this point may be specified even further. To stay with the analogy of (biological) 75 parents and their children: it is actually the content of ‘parents’—a male and a female (who at some point procreate together)—that exists prior to and independently of possibly ensuing ‘children’, whereas this content turns into ‘parents’ only in conjunction with ‘children’. That is, the concepts of ‘parents’ and ‘children’ are mutually entailing, whilst, strictly speaking, it is not ‘parents’, but rather that which will later be called ‘parents’ only once the ‘child’ comes into existence—the pre-existing content—which is antecedent to and causal for ‘children’.

Applied to the issue of rights and duties, this means that it is actually the content of a ‘right’—an interest—that exists prior to and independently of, and is (justificationally) causal for the creation of, a ‘duty’, which, in turn, is constitutive of a ‘right’. The distinction between ‘right’ and its content—an interest—allows the pinpointing of the latter as the reason for, and the former as the concomitant correlative of, a duty imposed to protect the pre-existing interest. It may thus be restated, more precisely, that it is not rights, but the protected interests which are grounds of duties. Incidentally, this specification is consistent with Raz’s definition of rights, according to which ‘having a right’ means that an aspect of the right holder’s well-being (her interest) ‘is a sufficient reason for holding some other person(s) to be under a duty’. 76 Now, the enactment of modern animal welfare laws is in and of itself evidence of the fact that some aspects of animals’ well-being (their interests) are—both temporally and justificationally—causal and a sufficient reason for imposing duties on others. Put differently: animal interests are grounds of animal welfare duties , and this, in turn, is conceptually constitutive of animal rights .

In conclusion, existing animal welfare laws could indeed be analysed as comprising unwritten ‘animal welfare rights’ as implicit correlatives of the explicit animal welfare duties imposed on others. The essential feature of legal rules conferring rights is that they specifically aim at protecting individual interests or goods—whether they do so expressis verbis or not is irrelevant. 77 Even so, in order for a right to be an actual (rather than a potential or merely postulated) legal right, it should at least be legally recognised (if not claimable and enforceable), 78 which is determined by the applicable legal rules. In the absence of unequivocal wording, whether a legal norm confers unwritten rights on animals becomes a matter of legal interpretation. While theorists can show that a rights-based approach lies within the bounds of a justifiable interpretation of the law, an actual, valid legal right hardly comes to exist by the mere fact that some theorists claim it exists. For that to happen, it seems instrumental that some public authoritative body, notably a court, recognises it as such. That is, while animals’ existing legal protections may already provide for all the ingredients constitutive of rights, it takes a court to actualise this potential , by authoritatively interpreting those legal rules as constituting rights of animals. However, because courts, with a few exceptions, have not done so thus far, it seems fair to say that unwritten animal rights are not (yet) legally recognised in practice and remain a mostly theoretical possibility for now. 79

B. The Weakness of Current ‘Animal Welfare Rights’

Besides the formal issue of legal recognition, there are substantive reasons for questioning whether the kind of rights extractable from animal welfare laws are really rights at all. This is because current ‘animal welfare rights’ are unusually weak rights that do not afford the sort of strong normative protection that is ordinarily associated with legal rights. 80 Classifying animals’ existing legal protections as ‘rights’ may thus conflict with the deeply held view that, because they protect interests of special importance, legal rights carry special normative force . 81 This quality is expressed in metaphors of rights as ‘trumps’, 82 ‘protective fences’, 83 protective shields or ‘No Trespassing’ signs, 84 or ‘suits of armor’. 85 Rights bestow upon individuals and their important interests a particularly robust kind of legal protection against conflicting individual or collective interests, by singling out ‘those interests that are not to be sacrificed to the utilitarian calculus ’ and ‘whose promotion or protection is to be given qualitative precedence over the social calculus of interests generally’. 86 Current ‘animal welfare rights’, by contrast, provide an atypically weak form of legal protection, notably for two reasons: because they protect interests of secondary importance or because they are easily overridden.

In order to illustrate this, consider the kind of rights that can be extracted from current animal welfare laws. Given that these are the correlatives of existing animal welfare duties, the substance of these rights must mirror the content laid down in the respective legal norms. This extraction method produces, first, a rather odd subgroup of ‘animal welfare rights’ that have a narrow substantive scope protecting highly specific, secondary interests, such as a (relative) right to be slaughtered with prior stunning, 87 an (absolute) right that experiments involving ‘serious injuries that may cause severe pain shall not be carried out without anaesthesia’ 88 or a right of chicks to be killed by fast-acting methods, such as homogenisation or gassing, and to not be stacked on top of each other. 89 The weak and subsidiary character of such rights becomes clearer when placed within the permissive institutional context in which they operate, and when taking into account the more basic interests that are left unprotected. 90 While these rights may protect certain secondary, derivative interests (such as the interest in being killed in a painless manner ), they are simultaneously premised on the permissibility of harming the more primary interests at stake (such as the interest in not being killed at all). Juxtaposed with the preponderance of suffering and killing that is legally allowed in the first place, phrasing the residual legal protections that animals do receive as ‘rights’ may strike us as misleading. 91

But then there is a second subgroup of ‘animal welfare rights’, extractable from general animal welfare provisions, that have a broader scope, protecting more basic, primary interests, such as a right to well-being, life, 92 dignity, 93 to not suffer unnecessarily, 94 or against torture and cruel treatment. 95 Although the object of such rights is of a more fundamental nature, the substantive guarantee of these facially fundamental rights is, to a great extent, eroded by a conspicuously low threshold for permissible infringements. 96 That is, these rights suffer from a lack of normative force, which manifests in their characteristically high infringeability (ie their low resistance to being overridden). Certainly, most rights (whether human or animal) are relative prima facie rights that allow for being balanced against conflicting interests and whose infringement constitutes a violation only when it is not justified, notably in terms of necessity and proportionality. 97 Taking rights seriously does, however, require certain safeguards ensuring that rights are only overridden by sufficiently important considerations whose weight is proportionate to the interests at stake. As pointed out by Waldron, the idea of rights is seized on as a way of resisting, or at least restricting, the sorts of trade-offs that would be acceptable in an unqualified utilitarian calculus, where ‘important individual interests may end up being traded off against considerations which are intrinsically less important’. 98 Yet, this is precisely what happens to animals’ prima facie protected interests, any of which—irrespective of how important or fundamental they are—may enter the utilitarian calculus, where they typically end up being outweighed by human interests that are comparatively less important or even trivial, notably dietary and fashion preferences, economic profitability, recreation or virtually any other conceivable human interest. 99

Any ‘animal welfare rights’ that animals may presently be said to have are thus either of the substantively oddly specific, yet rather secondary, kind or, in the case of more fundamental prima facie rights, such that are highly infringeable and ‘evaporate in the face of consequential considerations’. 100 The remaining question is whether these features render animals’ existing legal protections non-rights or just particularly unfit or weak rights , but rights nonetheless. The answer will depend on whether the quality of special strength, weight or force is considered a conceptually constitutive or merely typical but not essential feature of rights. On the first view, a certain normative force would function as a threshold criterion for determining what counts as a right and for disqualifying those legal protections that may structurally resemble rights but do not meet a minimum weight. 101 On the second view, the normative force of rights would serve as a variable that defines the particular weight of different types of rights on a spectrum from weak to strong. 102 To illustrate the intricacies of drawing a clear line between paradigmatically strong rights, weak rights or non-rights based on this criterion, let us return to the analogy with (biological) ‘parents’. In a minimal sense, the concept of ‘parents’ may be essentially defined as ‘biological creators of a child’. Typically, however, a special role as nurturer and caregiver is associated with the concept of ‘parent’. Now, is someone who merely meets the minimal conceptual criterion (by being the biological creator), but not the basic functions attached to the concept (by not giving care), still a ‘parent’? And, if so, to what extent? Are they a full and proper ‘parent’, or merely an imperfect, dysfunctional form of ‘parent’, a bad ‘parent’, but a ‘parent’ nonetheless? Maybe current animal rights are ‘rights’ in a similar sense as an absent, negligent, indifferent biological mother or father who does not assume the role and responsibilities that go along with parenthood is still a ‘parent’. That is, animals’ current legal protections may meet the minimal conceptual criteria for rights, but they do not perform the characteristic normative function of rights. They are, therefore, at best atypically weak and imperfect rights.

C. The Distinction between Simple and Fundamental Animal Rights

In the light of the aforesaid, if one adopts the view that animals’ existing legal protections constitute legal rights—that is, if one concludes that existing animal welfare laws confer legal rights on animals despite a lack of explicit legal enactment or of any coherent judicial recognition of unwritten animal rights, and that the kind of rights extractable from animal welfare law retain their rights character regardless of how weak they are—then an important qualification needs to be made regarding the nature and limits of such ‘animal welfare rights’. In particular, it must be emphasised that this type of legal animal rights falls short of (i) our ordinary understanding of legal rights as particularly robust protections of important interests and (ii) institutionalising the sort of inviolable, basic moral animal rights (along the lines of human rights) that animal rights theorists typically envisage. 103 It thus seems warranted to separate the kind of imperfect and weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law from the kind of ideal, 104 proper, strong fundamental rights that animals potentially ought to have as a matter of future law.

In order to denote and account for the qualitative difference between these two types of legal animal rights, and drawing on similar distinctions as regards the rights of individuals under public and international law, 105 I propose to use the conceptual categories of fundamental animal rights and other, simple animal rights. As to the demarcating criteria, we can distinguish between simple and fundamental animal rights based on a combination of two factors: (i) substance (fundamentality or non-fundamentality of the protected interests) and (ii) normative force (degree of infringeability). Accordingly, simple animal rights can be defined as weak legal rights whose substantive content is of a non-fundamental, ancillary character and/or that lack normative force due to their high infringeability. In contradistinction, fundamental animal rights are strong legal rights along the lines of human rights that are characterised by the cumulative features of substantive fundamentality and normative robustness due to their reduced infringeability.

The ‘animal welfare rights’ derivable from current animal welfare laws are simple animal rights. However, it is worth noting that while the first subtype of substantively non-fundamental ‘animal welfare rights’ belongs to this category irrespective of their infringeability, 106 the second subtype of substantively fundamental ‘animal welfare rights’ presently falls in this category purely in respect of their characteristically high infringeability. Yet, the latter is a dynamic and changeable feature, insofar as these rights could be dealt with, in case of conflict, in a manner whereby they would prove to be more robust. In other words, while the simple animal rights of the second subtype currently lack the normative force of legal rights, they do have the potential to become fundamental animal rights. Why animals need such fundamental rights will be explored in the final section.

Beyond the imperfect, weak, simple rights that animals may be said to have based on existing animal welfare laws, a final normative question remains with a view to the future law: whether animals ought to have strong legal rights proper. I will focus on fundamental animal rights—such as the right to life, bodily integrity, liberty and freedom from torture—as these correspond best with the kind of ‘ought to be legal rights’ typically alluded to in animal rights discourse. Given the general appeal of rights language, it is not surprising that among animal advocates there is an overall presumption in favour of basic human rights-like animal rights. 107 However, it is often simply assumed that, rather than elucidated why, legal rights would benefit animals and how this would strengthen their protection. In order to undergird the normative claim that animals should have strong legal rights, the following subsections will look at functional reasons why animals need such rights. 108 I will do so through a non-exhaustive exploration of the potential legal advantages and political utility of fundamental animal rights over animals’ current legal protections (be they animal welfare laws or ‘animal welfare rights’).

A. Procedural Aspect: Standing and Enforceability

Against the backdrop of today’s well-established ‘enforcement gap’ and ‘standing dilemma’, 109 one of the most practical benefits typically associated with, or expected from, legal animal rights is the facilitation of standing for animals in their own right and, closely related, the availability of more efficient mechanisms for the judicial enforcement of animals’ legal protections. 110 This is because legal rights usually include the procedural element of having standing to sue, the right to seek redress and powers of enforcement—which would enable animals (represented by legal guardians) to institute legal proceedings in their own right and to assert injuries of their own. 111 This would also ‘decentralise’ enforcement, that is, it would not be concentrated in the hands (and at the sole discretion) of public authorities, but supplemented by private standing of animals to demand enforcement. Ultimately, such an expanded enforceability could also facilitate incremental legal change by feeding animal rights questions into courts as fora for public deliberation.

However, while standing and enforceability constitute crucial procedural components of any effective legal protection of animals, for present purposes, it should be noted that fundamental animal rights (or any legal animal rights) are—albeit maybe conducive—neither necessary nor sufficient to this end. On the one hand, not all legal rights (eg some socio-economic human rights) are necessarily enforceable. Merely conferring legal rights on animals will therefore, in itself, not guarantee sufficient legal protection from a procedural point of view. Rather, fundamental animal rights must encompass certain procedural rights, such as the right to access to justice, in order to make them effectively enforceable. On the other hand, animals or designated animal advocates could simply be granted standing auxiliary to today’s animal welfare laws, which would certainly contribute towards narrowing the enforcement gap. 112 Yet, standing as such merely offers the purely procedural benefit of being able to legally assert and effectively enforce any given legal protections that animals may have, but has no bearing on the substantive content of those enforceable protections. Given that the issue is not just one of improving the enforcement of animals’ existing legal protections, but also of substantially improving them, standing alone cannot substitute for strong substantive animal rights. Therefore, animals will ultimately need both strong substantive and enforceable rights, which may be best achieved through an interplay of fundamental rights and accompanying procedural guarantees.

B. Substantive Aspect: Stronger Legal Protection for Important Interests

The aforesaid suggests that the critical function of fundamental animal rights is not procedural in nature; rather, it is to substantively improve and fortify the protection of important animal interests. In particular, fundamental animal rights would strengthen the legal protection of animals on three levels: by establishing an abstract equality of arms, by broadening the scope of protection to include more fundamental substantive guarantees and by raising the burden of justification for infringements.

First of all, fundamental animal rights would create the structural preconditions for a level playing field where human and animal interests are both reinforced by equivalent rights, and can thus collide on equal terms. Generally speaking, not all legally recognised interests count equally when balanced against each other, and rights-empowered interests typically take precedence over or are accorded more weight than unqualified competing interests. 113 At present, the structural makeup of the balancing process governing human–animal conflicts is predisposed towards a prioritisation of human over animal interests. Whereas human interests are buttressed by strong, often fundamental rights (such as economic, religious or property rights), the interests at stake on the animal side, if legally protected at all, enter the utilitarian calculus as unqualified interests that are merely shielded by simple animal welfare laws, or simple rights that evaporate quickly in situations of conflict and do not compare to the sorts of strong rights that reinforce contrary human interests. 114 In order to achieve some form of abstract equality of arms, animals’ interests need to be shielded by strong legal rights that are a match to humans’ rights. Fundamental animal rights would correct this structural imbalance and set the stage for an equal consideration of interests that is not a priori biased in favour of humans’ rights.

Furthermore, as defined above, fundamental animal rights are characterised by both their substantive fundamentality and normative force, and would thus strengthen animals’ legal protection in two crucial respects. On a substantive level , fundamental animal rights are grounded in especially important, fundamental interests. Compared to substantively non-fundamental simple animal rights, which provide for narrow substantive guarantees that protect secondary interests, fundamental animal rights would expand the scope of protection to cover a wider array of basic and primary interests. As a result, harming fundamentally important interests of animals—while readily permissible today insofar as such interests are often not legally protected in the first place 115 —would trigger a justification requirement that initially allows those animal interests to enter into a balancing process. For even with fundamental animal rights in play, conflicts between human and animal interests will inevitably continue to exist—albeit at the elevated and abstractly equal level of conflicts of rights—and therefore require some sort of balancing mechanism. 116

On this justificatory level , fundamental animal rights would then demand a special kind and higher burden of justification for infringements. 117 As demonstrated above, substantively fundamental yet highly infringeable simple animal rights are marked by a conspicuously low threshold for justifiable infringements, and are regularly outweighed by inferior or even trivial human interests. By contrast, the normative force of fundamental animal rights rests on their ability to raise the ‘level of the minimally sufficient justification’. 118 Modelling these more stringent justification requirements on established principles of fundamental (human) rights adjudication, this would, first, limit the sorts of considerations that constitute a ‘legitimate aim’ which can be balanced against fundamental animal rights. Furthermore, the balancing process must encompass a strict proportionality analysis, comprised of the elements of suitability, necessity and proportionality stricto sensu , which would preclude the bulk of the sorts of low-level justifications that are currently sufficient. 119 This heightened threshold for justifiable infringements, in turn, translates into a decreased infringeability of fundamental animal rights and an increased immunisation of animals’ prima facie protected interests against being overridden by conflicting considerations and interests of lesser importance.

Overall, considering this three-layered strengthening of the legal protection of animals’ important interests, fundamental animal rights are likely to set robust limits to the violability and disposability of animals as means to human ends, and to insulate animals from many of the unnecessary and disproportionate inflictions of harm that are presently allowed by law.

C. Fallback Function: The Role of Rights in Non-ideal Societies