Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Students Share Their Best School Experiences and What We Can Learn From Them

- Share article

Today, five students from my classes contribute short pieces about their favorite moments, and what others might be able to learn from them.

You might also be interested in these two other posts:

- Students Describe Their Favorite Teachers

- ‘He Was a Very Good Listener’ - Students Write About Their Most Memorable Teachers

Response From Leslie Servin

During my time in high school I had it really good moments, but my best moments that I’ve experienced are in a particular class during my senior year, in Sacramento, Calif. So I was basically a new student in these kind of classes and also I’m English learner. I remember my first presentation in this class. I didn’t want to do it, but finally I did it and that one was my best moment. When I went to present I felt afraid, and then when I presented I felt so good for the effort I applied on. Now I feel so much better than my first day of presentations because I now know that I can do whatever I want to do. The learnings that I acquire made it so good this moment because I know that I have to trust on me. Something teachers or students can learn from my experience is that we have to overcome our fears and not let them control ourselves because we can’t know our capabilities if we are afraid.

Response From Jesneel Singh

The best moment in class was when I was in 9th grade in sixth period. That was when I got into poetry and spoken word. Having that “character and scene” class made my life even greater. Not knowing anything about poetry, hating on poems about reading and writing it in the past. That class was fun in many ways. For example; there was this one time where we had to write our own plays and poems and perform them in front of the class. I felt alive, and the creative side of me came out. When I wrote my first poem in freshman year. I realized that it was fun and unique. I felt like I wanted to write more and more. When I performed my first poem to that class I found my passion. Since that day and today I have written over 400 poems and made two books. I have performed on many stages in small audience and in school. That was a good day for me because I can write my thoughts down and write the truth about the world. Teachers and students can learn from this experience that, you can find what best fits you.

Response From Nancy Ramirez

I would say my best class moment would be from my sophomore year in high school. For my Spanish class, our teacher decided we would do a class circle (Editor’s note: see “How To Practice Restorative Justice in Schools” for more information on class circles) for the day. She asked us a sequence of questions which required us to give a more in depth and heartfelt answer each time, starting with something along the lines of “How are you feeling?” and ending with “Why do you think that is?” A class circle which only should have lasted one day extended to three, with each and every single one of us having to share our deepest and darkest fears and insecurities. By then it felt more than just a class and opened my eyes to very different ways of teaching styles. I believe there is much to learn from this experience, both then and now. I have come to deeply appreciate not only the class but the teacher as well. This experience showed me the extent a relationship with your classmates and your teacher can go....

Response From Oscar Salazar

The best moment I’ve ever experienced in school was last year when I was a sophomore. I took biology last year and towards the end of the year we got to dissect a fetal pig. I know that it sounds gross but it’s really not. That’s what I thought at first too. I did lots of fun experiments in that class that were new to me, such as making a small ecosystem in a bottle and dissecting owl pellets to find mouse skeletons. I think that these experiences were really fun and interesting. I’ve never done anything like that in a class before.

I think that when teachers introduce students to hands-on activities and projects the students enjoy it more. Since we have more energy it’s a good use of it. We learn better when we’re allowed to move around and be creative. Our lives aren’t going to be pen on paper or books forever. It’s best to get us students to explore the world using our skills that we learn and strengthen our understanding of daily life that is sometimes hidden from us and exposed to us abruptly once we turn into adults.

Response From Kayla Guzman

What has been my best moment in a class? I’ve had many great moments but perhaps the most best moment took place in my English class about a month ago. I had a 10-15 minute presentation and I felt pretty confident. 30 minutes before my presentation I decided to incorporate an actor for visual appeal, to correspond with my presentation. I felt even more confident, assure that I would captivate the audience’s attention and keep them engaged. When my presentation started, I gave a signal to my actor which led me to drop my 8 notecards all over the floor. I was aware that the time was ticking, so I quickly grabbed all the notecards off the floor. I became overwhelmed with embarrassment, listening to the echoing laughter of the audience as I tried to rearrange the cards. The cards in my hand then became extremely restraining. My anxiety levels rose, and the disorganized cards just added stress to my emotions. I placed the cards down, and felt a great sense of relieve. My words, my explanations, my connections all flowed out my mouth with harmony, and I felt more natural and free as I presented my topic.

My presentation was a diagnosis of a character with schizophrenia, explaining the symptoms and the reasoning behind my diagnosis. The movement of my hands and my exaggeration presented by a drive of passion, along with my visual representative, kept the audience captive. I felt like a completely different person. By the end of the presentation I was sweaty, not by nervousness but because I left it all on the floor. I realized that the key to presenting with people is not getting their attention just by visual appeal. You need to let your heart pour out so that you can captivate their hearts, reach their souls. You can’t just be the center of attention, you need to give the audience attention, you need to talk to them. First and foremost, you can’t present without emotions. Anything you present should be built off of passion. As long as you can find a connection between yourself and the topic and exude your passion, you will keep the audience engaged.

Thanks to Nancy, Jesneel, Kayla, Leslie, and Oscar for their contributions!

(This is the last post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here and Part Two here .)

The new “question-of-the-week” is:

What was the best moment you ever had in the classroom?

In Part One , Jen Schwanke, Amy Sandvold, Anne Jenks, and Sarah Thomas shared their top moments. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with them on my BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here. In Part Two , Meghan Everette, Jeryl-Ann Asaro, Jeffery Galle, and Kara Vandas shared their memories. I also included comments from readers.

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Anyone whose question is selected for this weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

If you missed any of the highlights from the first six years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. They don’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Classroom Management Advice

Race & Gender Challenges

Implementing The Common Core

Best Ways To Begin The School Year

Best Ways To End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social Emotional Learning

Teaching Social Studies

Project-Based Learning

Using Tech In The Classroom

Parent Engagement In Schools

Teaching English Language Learners

Student Assessment

Brain-Based Learning

Reading Instruction

Writing Instruction

Education Policy Issues

Differentiating Instruction

Math Instruction

Science Instruction

Advice For New Teachers

Author Interviews

Entering The Teaching Profession

Administrator Leadership

Teacher Leadership

Relationships In Schools

Professional Development

Instructional Strategies

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

Look for the next “question-of-the-week” in a few days.

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Educational Experiences Become Experiential When the Learner is Fully Present There is more to experiential learning than just "having" the experience.

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

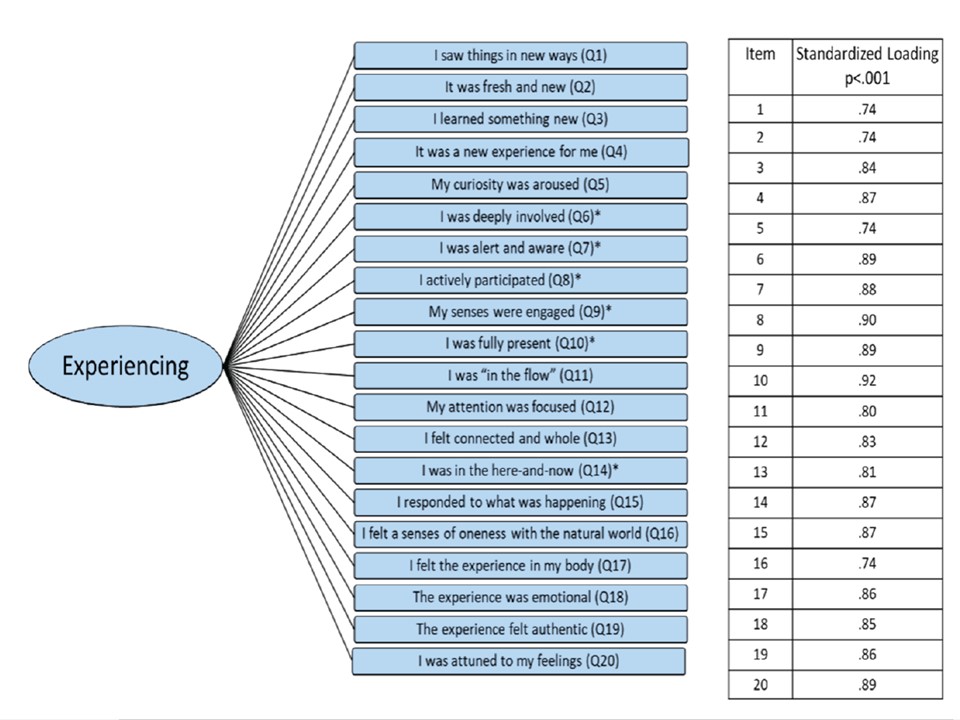

The 21st century has seen a dramatic rise in experiential learning research and practice. After the previous century, where research on subjective experience was for the most part excluded from academic journals, there is today a resurgence of scholarly research on experience and experiential learning. Yet, how do we know when a given educational experience is experiential? We argue that there is something more to experiential learning than just having an experience. That “something more” is a process of experiencing, a process whereby the learner deeply engages with an experience and is fully present. Through research conducted from an international sample of learners who based response to their lived experience outside of the classroom, we extend findings from Stock & Kolb (2021) and introduce a revised version of the Experiencing Scale based on the discovery of the overarching importance of the role of presence and its ramifications for the experiencing process. Our analysis here suggests that when learning is experiential, it is characterized by active participation, sensory engagement, deep involvement, alert/ aware attention and being fully present in the here-and-now.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

How technology is reinventing education

Stanford Graduate School of Education Dean Dan Schwartz and other education scholars weigh in on what's next for some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

Why learning from experience is the educational wave of the future

Dean of Engineering and Professor, McMaster University

Disclosure statement

Ishwar K. Puri receives funding from National Science and Engineering Research Council. He is chair of the National Council of Deans of Engineering and Applied Science and Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Engineering.

McMaster University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

McMaster University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

The university experience has changed .

It used to be enough for students to spend four years working hard on assignments, labs and exams to earn a useful undergraduate degree that signalled competence and was redeemable for a good job.

Employers would spend weeks or months training their newly hired graduates , sometimes in cohorts, shaping their broad knowledge so it could be applied to the specific needs of the company or government agency.

Today, in contrast, employers want fresh graduates who they don’t have to train .

That means students must learn and apply their knowledge at the same time, inside and outside the classroom, all without adding extra months or years to their studies . After completing their degrees, they are expected to be ready to compete for jobs and jump into working life immediately, without further training.

In the ongoing global drive for efficiency and competitiveness, education and training are now seen as the responsibility of the post-secondary sector, where students face a wider set of expectations not only to learn and synthesize subject matter, but to adapt it and put it to use almost immediately.

Learning by doing

This idea of learning by doing is what is now called “experiential learning,” and though it’s demanding, it is also very effective. It is vital to the mission of all advanced institutions of higher learning, including the one where I am dean of engineering, McMaster University in Hamilton.

In class, this method of learning means replacing chalk-and-talk pedagogy of the past with inquiry, problem-based and project-based learning, sometimes using the tools of what we call a maker space — an open, studio-like creative workshop.

These methods recognize that lectures on complex, abstract subjects are difficult to comprehend, and that hands-on, minds-on learning by experience not only makes it easier to absorb complex material, it also makes it easier to remember .

Outside class, experiential learning takes the form of clubs, activities and competitions for fun, such as the international EcoCAR competition, converting muscle cars from gas to electric power , or hackathons that see students compete to solve complex technical and social problems .

This year at McMaster, experiential learning has been both the competition and the prize as six winners of an extracurricular Big Ideas competition flew off to tour Silicon Valley facilities where they hope one day to work or learn how to start up their own ventures.

Experiential learning also means engaging undergraduates directly in high-level research that was once the exclusive domain of graduate students and professors, exposing them to scholarship at the highest level from early in their academic careers.

In the community, experiential learning is learning through service , both within and beyond one’s area of study — rebuilding hurricane-damaged communities, for example, or helping at local soup kitchens. We are teaching students not only to be workers who drive the modern economy, but also to be engaged citizens .

Work-integrated learning sees students stepping into the actual workplace to get a flavour of what working life is like in their fields , including managing time, working independently, multi-tasking, and adapting to the particular culture and expectations of a specific workplace, all as part of their formal education.

We want students to understand and approach the grand challenges and wicked problems facing our world, such as climate change and opioid addiction, which are not solely issues of science or technology, sociology or economics, but complex, layered issues that demand broad thinking and collaboration.

Canada needs innovators

We want our students to be innovators. If life in Canada is to improve, especially in the context of challenging trade relationships such as NAFTA, we need a workforce that can address global problems with innovation that is relevant —technologically, socially, economically, with respect for all cultures and genders.

All of this learning drives students to begin thinking and acting with their careers in mind from their very first year of study.

Is that fair?

It is important to remember that high school has changed too. Students are better prepared than they were a generation ago. By the time they enter university, they are more aware of the new demands on their time and achievements.

Much more information is also available about employment and specific employers from portals like Glassdoor , allowing students to make more informed choices about their co-op placements or the permanent employers they will target or reject, based on reputation and organizational climate.

We cannot change the fact that the world is more competitive, nor that it takes more to succeed than it used to.

What we can do is make sure that the extra work that goes into creating and completing a fully realized university experience is as valuable as it can possibly be.

- Universities

- Engineering

- Competitiveness

- Post-secondary education

- Experiential learning

Program Manager, Teaching & Learning Initiatives

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of remote learning methods: from the covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future.

- 1 Minerva Schools at Keck Graduate Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 2 Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship, Montclair, NJ, United States

- 3 Department of Physics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

This spring, students across the globe transitioned from in-person classes to remote learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented change to undergraduate education saw institutions adopting multiple online teaching modalities and instructional platforms. We sought to understand students’ experiences with and perspectives on those methods of remote instruction in order to inform pedagogical decisions during the current pandemic and in future development of online courses and virtual learning experiences. Our survey gathered quantitative and qualitative data regarding students’ experiences with synchronous and asynchronous methods of remote learning and specific pedagogical techniques associated with each. A total of 4,789 undergraduate participants representing institutions across 95 countries were recruited via Instagram. We find that most students prefer synchronous online classes, and students whose primary mode of remote instruction has been synchronous report being more engaged and motivated. Our qualitative data show that students miss the social aspects of learning on campus, and it is possible that synchronous learning helps to mitigate some feelings of isolation. Students whose synchronous classes include active-learning techniques (which are inherently more social) report significantly higher levels of engagement, motivation, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction. Respondents’ recommendations for changes emphasize increased engagement, interaction, and student participation. We conclude that active-learning methods, which are known to increase motivation, engagement, and learning in traditional classrooms, also have a positive impact in the remote-learning environment. Integrating these elements into online courses will improve the student experience.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the demographics of online students. Previously, almost all students engaged in online learning elected the online format, starting with individual online courses in the mid-1990s through today’s robust online degree and certificate programs. These students prioritize convenience, flexibility and ability to work while studying and are older than traditional college age students ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). These students also find asynchronous elements of a course are more useful than synchronous elements ( Gillingham and Molinari, 2012 ). In contrast, students who chose to take courses in-person prioritize face-to-face instruction and connection with others and skew considerably younger ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ). This leaves open the question of whether students who prefer to learn in-person but are forced to learn remotely will prefer synchronous or asynchronous methods. One study of student preferences following a switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that students enjoy synchronous over asynchronous course elements and find them more effective ( Gillis and Krull, 2020 ). Now that millions of traditional in-person courses have transitioned online, our survey expands the data on student preferences and explores if those preferences align with pedagogical best practices.

An extensive body of research has explored what instructional methods improve student learning outcomes (Fink. 2013). Considerable evidence indicates that active-learning or student-centered approaches result in better learning outcomes than passive-learning or instructor-centered approaches, both in-person and online ( Freeman et al., 2014 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Active-learning approaches include student activities or discussion in class, whereas passive-learning approaches emphasize extensive exposition by the instructor ( Freeman et al., 2014 ). Constructivist learning theories argue that students must be active participants in creating their own learning, and that listening to expert explanations is seldom sufficient to trigger the neurological changes necessary for learning ( Bostock, 1998 ; Zull, 2002 ). Some studies conclude that, while students learn more via active learning, they may report greater perceptions of their learning and greater enjoyment when passive approaches are used ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). We examine student perceptions of remote learning experiences in light of these previous findings.

In this study, we administered a survey focused on student perceptions of remote learning in late May 2020 through the social media account of @unjadedjade to a global population of English speaking undergraduate students representing institutions across 95 countries. We aim to explore how students were being taught, the relationship between pedagogical methods and student perceptions of their experience, and the reasons behind those perceptions. Here we present an initial analysis of the results and share our data set for further inquiry. We find that positive student perceptions correlate with synchronous courses that employ a variety of interactive pedagogical techniques, and that students overwhelmingly suggest behavioral and pedagogical changes that increase social engagement and interaction. We argue that these results support the importance of active learning in an online environment.

Materials and Methods

Participant pool.

Students were recruited through the Instagram account @unjadedjade. This social media platform, run by influencer Jade Bowler, focuses on education, effective study tips, ethical lifestyle, and promotes a positive mindset. For this reason, the audience is presumably academically inclined, and interested in self-improvement. The survey was posted to her account and received 10,563 responses within the first 36 h. Here we analyze the 4,789 of those responses that came from undergraduates. While we did not collect demographic or identifying information, we suspect that women are overrepresented in these data as followers of @unjadedjade are 80% women. A large minority of respondents were from the United Kingdom as Jade Bowler is a British influencer. Specifically, 43.3% of participants attend United Kingdom institutions, followed by 6.7% attending university in the Netherlands, 6.1% in Germany, 5.8% in the United States and 4.2% in Australia. Ninety additional countries are represented in these data (see Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Survey Design

The purpose of this survey is to learn about students’ instructional experiences following the transition to remote learning in the spring of 2020.

This survey was initially created for a student assignment for the undergraduate course Empirical Analysis at Minerva Schools at KGI. That version served as a robust pre-test and allowed for identification of the primary online platforms used, and the four primary modes of learning: synchronous (live) classes, recorded lectures and videos, uploaded or emailed materials, and chat-based communication. We did not adapt any open-ended questions based on the pre-test survey to avoid biasing the results and only corrected language in questions for clarity. We used these data along with an analysis of common practices in online learning to revise the survey. Our revised survey asked students to identify the synchronous and asynchronous pedagogical methods and platforms that they were using for remote learning. Pedagogical methods were drawn from literature assessing active and passive teaching strategies in North American institutions ( Fink, 2013 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Open-ended questions asked students to describe why they preferred certain modes of learning and how they could improve their learning experience. Students also reported on their affective response to learning and participation using a Likert scale.

The revised survey also asked whether students had responded to the earlier survey. No significant differences were found between responses of those answering for the first and second times (data not shown). See Supplementary Appendix 1 for survey questions. Survey data was collected from 5/21/20 to 5/23/20.

Qualitative Coding

We applied a qualitative coding framework adapted from Gale et al. (2013) to analyze student responses to open-ended questions. Four researchers read several hundred responses and noted themes that surfaced. We then developed a list of themes inductively from the survey data and deductively from the literature on pedagogical practice ( Garrison et al., 1999 ; Zull, 2002 ; Fink, 2013 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). The initial codebook was revised collaboratively based on feedback from researchers after coding 20–80 qualitative comments each. Before coding their assigned questions, alignment was examined through coding of 20 additional responses. Researchers aligned in identifying the same major themes. Discrepancies in terms identified were resolved through discussion. Researchers continued to meet weekly to discuss progress and alignment. The majority of responses were coded by a single researcher using the final codebook ( Supplementary Table 1 ). All responses to questions 3 (4,318 responses) and 8 (4,704 responses), and 2,512 of 4,776 responses to question 12 were analyzed. Valence was also indicated where necessary (i.e., positive or negative discussion of terms). This paper focuses on the most prevalent themes from our initial analysis of the qualitative responses. The corresponding author reviewed codes to ensure consistency and accuracy of reported data.

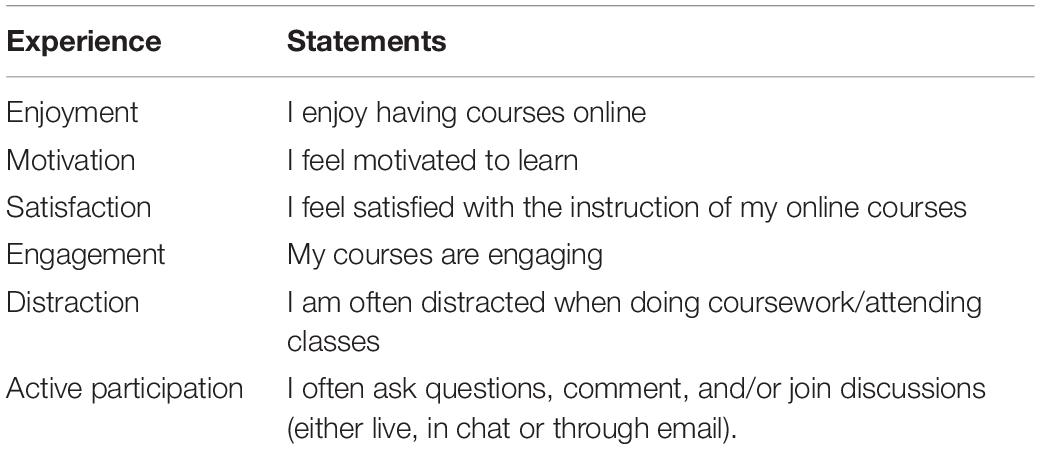

Statistical Analysis

The survey included two sets of Likert-scale questions, one consisting of a set of six statements about students’ perceptions of their experiences following the transition to remote learning ( Table 1 ). For each statement, students indicated their level of agreement with the statement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). The second set asked the students to respond to the same set of statements, but about their retroactive perceptions of their experiences with in-person instruction before the transition to remote learning. This set was not the subject of our analysis but is present in the published survey results. To explore correlations among student responses, we used CrossCat analysis to calculate the probability of dependence between Likert-scale responses ( Mansinghka et al., 2016 ).

Table 1. Likert-scale questions.

Mean values are calculated based on the numerical scores associated with each response. Measures of statistical significance for comparisons between different subgroups of respondents were calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U -test, and p -values reported here are based on this test statistic. We report effect sizes in pairwise comparisons using the common-language effect size, f , which is the probability that the response from a random sample from subgroup 1 is greater than the response from a random sample from subgroup 2. We also examined the effects of different modes of remote learning and technological platforms using ordinal logistic regression. With the exception of the mean values, all of these analyses treat Likert-scale responses as ordinal-scale, rather than interval-scale data.

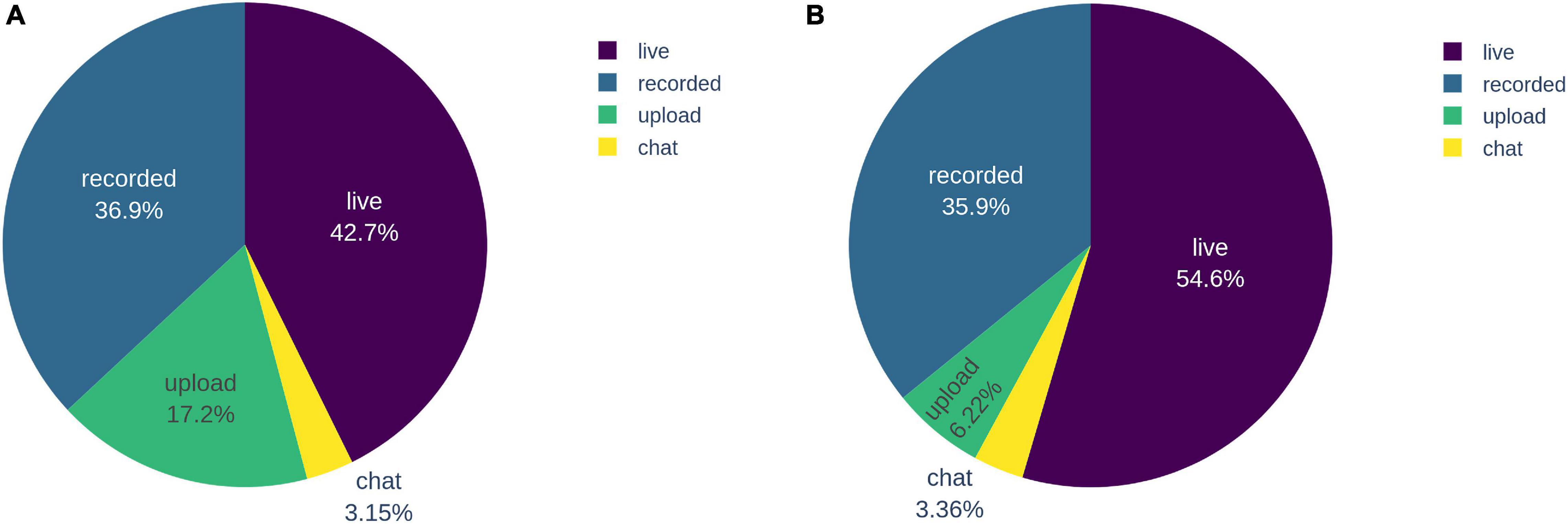

Students Prefer Synchronous Class Sessions

Students were asked to identify their primary mode of learning given four categories of remote course design that emerged from the pilot survey and across literature on online teaching: live (synchronous) classes, recorded lectures and videos, emailed or uploaded materials, and chats and discussion forums. While 42.7% ( n = 2,045) students identified live classes as their primary mode of learning, 54.6% ( n = 2613) students preferred this mode ( Figure 1 ). Both recorded lectures and live classes were preferred over uploaded materials (6.22%, n = 298) and chat (3.36%, n = 161).

Figure 1. Actual (A) and preferred (B) primary modes of learning.

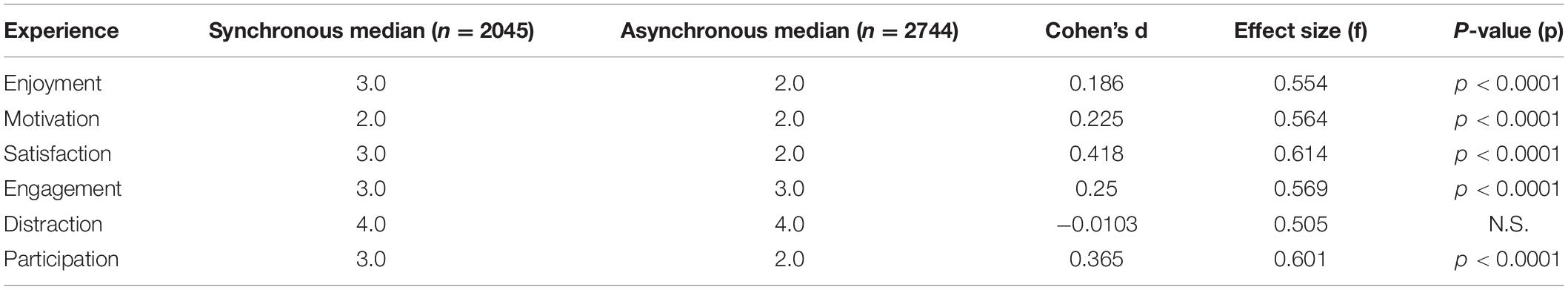

In addition to a preference for live classes, students whose primary mode was synchronous were more likely to enjoy the class, feel motivated and engaged, be satisfied with instruction and report higher levels of participation ( Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 ). Regardless of primary mode, over two-thirds of students reported they are often distracted during remote courses.

Table 2. The effect of synchronous vs. asynchronous primary modes of learning on student perceptions.

Variation in Pedagogical Techniques for Synchronous Classes Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

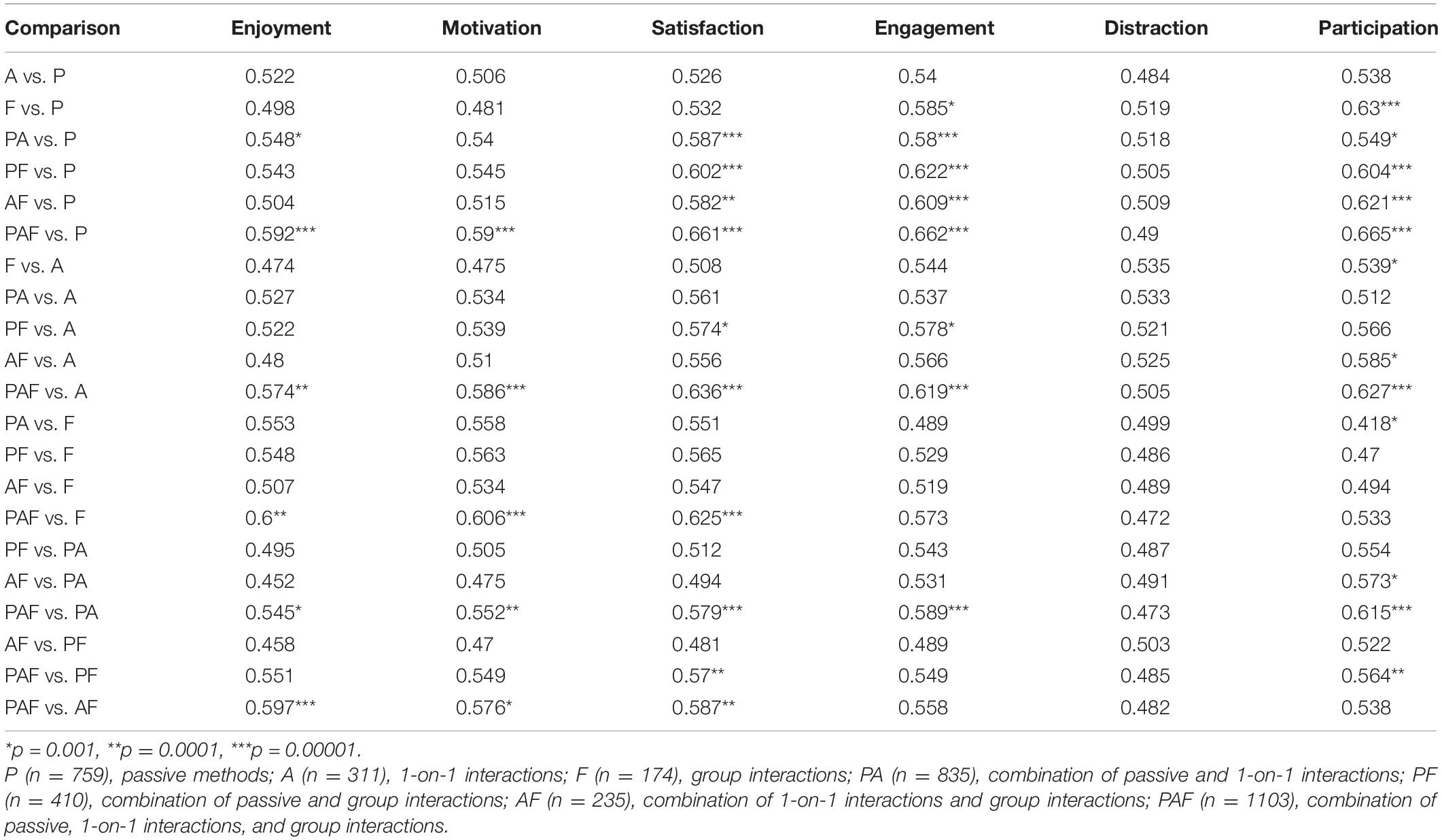

To survey the use of passive vs. active instructional methods, students reported the pedagogical techniques used in their live classes. Among the synchronous methods, we identify three different categories ( National Research Council, 2000 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). Passive methods (P) include lectures, presentations, and explanation using diagrams, white boards and/or other media. These methods all rely on instructor delivery rather than student participation. Our next category represents active learning through primarily one-on-one interactions (A). The methods in this group are in-class assessment, question-and-answer (Q&A), and classroom chat. Group interactions (F) included classroom discussions and small-group activities. Given these categories, Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons between the 7 possible combinations and Likert scale responses about student experience showed that the use of a variety of methods resulted in higher ratings of experience vs. the use of a single method whether or not that single method was active or passive ( Table 3 ). Indeed, students whose classes used methods from each category (PAF) had higher ratings of enjoyment, motivation, and satisfaction with instruction than those who only chose any single method ( p < 0.0001) and also rated higher rates of participation and engagement compared to students whose only method was passive (P) or active through one-on-one interactions (A) ( p < 0.00001). Student ratings of distraction were not significantly different for any comparison. Given that sets of Likert responses often appeared significant together in these comparisons, we ran a CrossCat analysis to look at the probability of dependence across Likert responses. Responses have a high probability of dependence on each other, limiting what we can claim about any discrete response ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

Table 3. Comparison of combinations of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

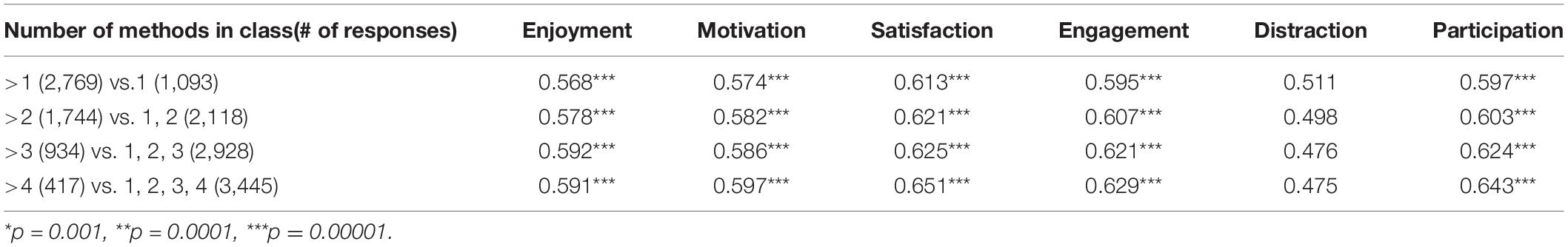

Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons were also used to check if improvement in student experience was associated with the number of methods used vs. the variety of types of methods. For every comparison, we found that more methods resulted in higher scores on all Likert measures except distraction ( Table 4 ). Even comparison between four or fewer methods and greater than four methods resulted in a 59% chance that the latter enjoyed the courses more ( p < 0.00001) and 60% chance that they felt more motivated to learn ( p < 0.00001). Students who selected more than four methods ( n = 417) were also 65.1% ( p < 0.00001), 62.9% ( p < 0.00001) and 64.3% ( p < 0.00001) more satisfied with instruction, engaged, and actively participating, respectfully. Therefore, there was an overlap between how the number and variety of methods influenced students’ experiences. Since the number of techniques per category is 2–3, we cannot fully disentangle the effect of number vs. variety. Pairwise comparisons to look at subsets of data with 2–3 methods from a single group vs. 2–3 methods across groups controlled for this but had low sample numbers in most groups and resulted in no significant findings (data not shown). Therefore, from the data we have in our survey, there seems to be an interdependence between number and variety of methods on students’ learning experiences.

Table 4. Comparison of the number of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Variation in Asynchronous Pedagogical Techniques Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

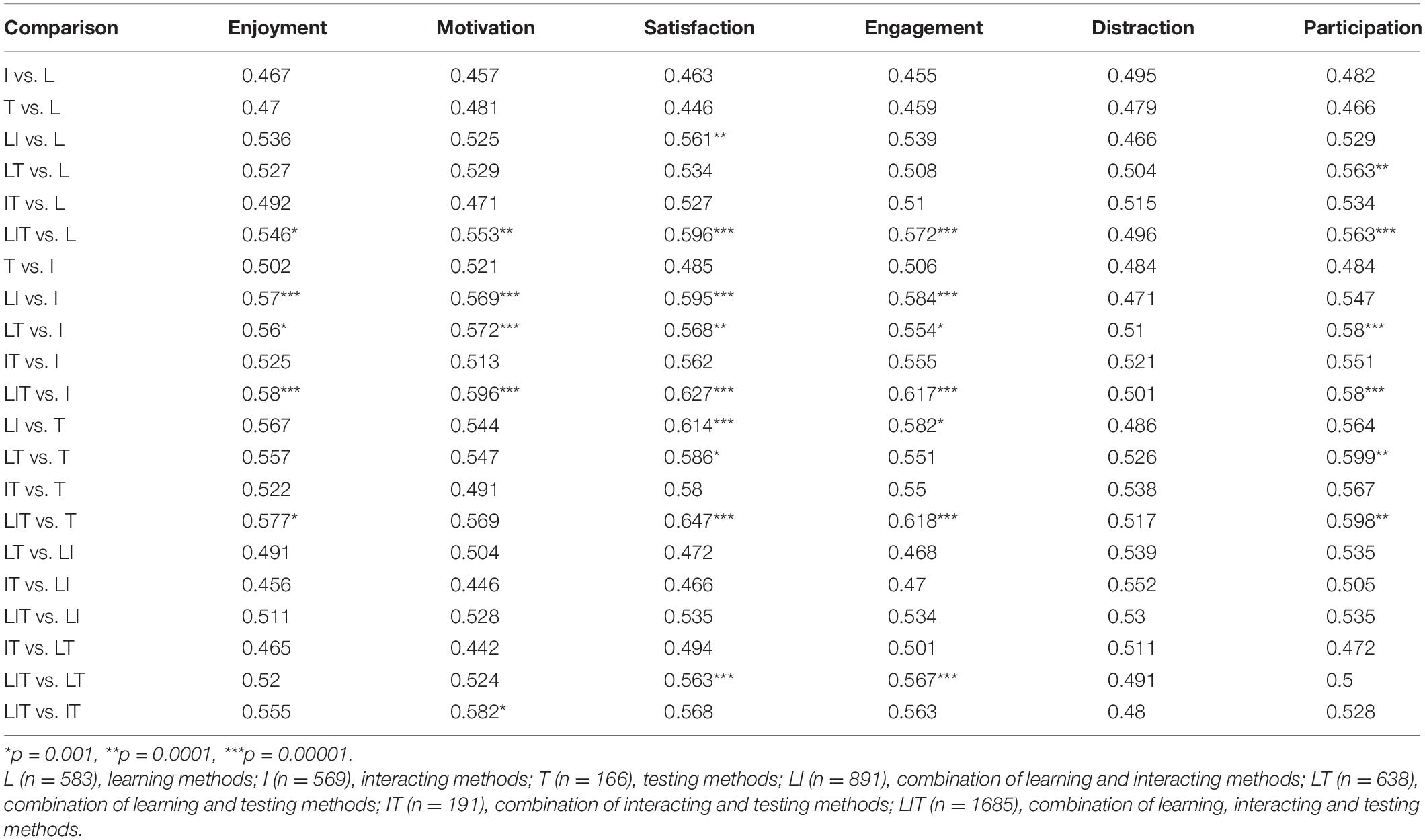

Along with synchronous pedagogical methods, students reported the asynchronous methods that were used for their classes. We divided these methods into three main categories and conducted pairwise comparisons. Learning methods include video lectures, video content, and posted study materials. Interacting methods include discussion/chat forums, live office hours, and email Q&A with professors. Testing methods include assignments and exams. Our results again show the importance of variety in students’ perceptions ( Table 5 ). For example, compared to providing learning materials only, providing learning materials, interaction, and testing improved enjoyment ( f = 0.546, p < 0.001), motivation ( f = 0.553, p < 0.0001), satisfaction with instruction ( f = 0.596, p < 0.00001), engagement ( f = 0.572, p < 0.00001) and active participation ( f = 0.563, p < 0.00001) (row 6). Similarly, compared to just being interactive with conversations, the combination of all three methods improved five out of six indicators, except for distraction in class (row 11).

Table 5. Comparison of combinations of asynchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood that the platforms students used predicted student perceptions ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Platform choices were based on the answers to open-ended questions in the pre-test survey. The synchronous and asynchronous methods used were consistently more predictive of Likert responses than the specific platforms. Likewise, distraction continued to be our outlier with no differences across methods or platforms.

Students Prefer In-Person and Synchronous Online Learning Largely Due to Social-Emotional Reasoning

As expected, 86.1% (4,123) of survey participants report a preference for in-person courses, while 13.9% (666) prefer online courses. When asked to explain the reasons for their preference, students who prefer in-person courses most often mention the importance of social interaction (693 mentions), engagement (639 mentions), and motivation (440 mentions). These students are also more likely to mention a preference for a fixed schedule (185 mentions) vs. a flexible schedule (2 mentions).

In addition to identifying social reasons for their preference for in-person learning, students’ suggestions for improvements in online learning focus primarily on increasing interaction and engagement, with 845 mentions of live classes, 685 mentions of interaction, 126 calls for increased participation and calls for changes related to these topics such as, “Smaller teaching groups for live sessions so that everyone is encouraged to talk as some people don’t say anything and don’t participate in group work,” and “Make it less of the professor reading the pdf that was given to us and more interaction.”

Students who prefer online learning primarily identify independence and flexibility (214 mentions) and reasons related to anxiety and discomfort in in-person settings (41 mentions). Anxiety was only mentioned 12 times in the much larger group that prefers in-person learning.

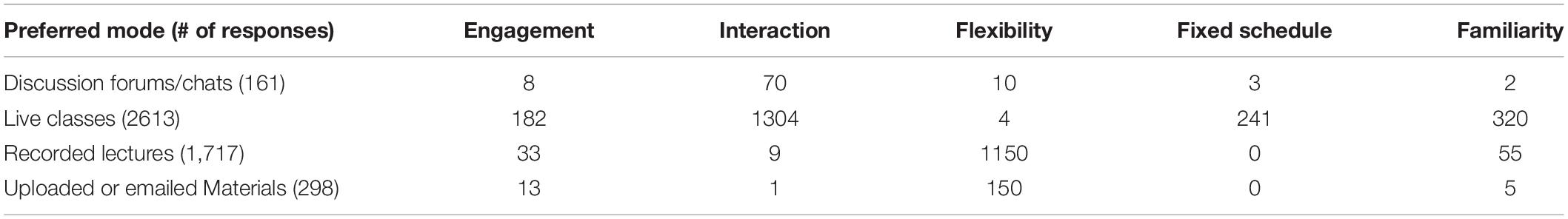

The preference for synchronous vs. asynchronous modes of learning follows similar trends ( Table 6 ). Students who prefer live classes mention engagement and interaction most often while those who prefer recorded lectures mention flexibility.

Table 6. Most prevalent themes for students based on their preferred mode of remote learning.

Student Perceptions Align With Research on Active Learning

The first, and most robust, conclusion is that incorporation of active-learning methods correlates with more positive student perceptions of affect and engagement. We can see this clearly in the substantial differences on a number of measures, where students whose classes used only passive-learning techniques reported lower levels of engagement, satisfaction, participation, and motivation when compared with students whose classes incorporated at least some active-learning elements. This result is consistent with prior research on the value of active learning ( Freeman et al., 2014 ).

Though research shows that student learning improves in active learning classes, on campus, student perceptions of their learning, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction are often lower in active-learning courses ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). Our finding that students rate enjoyment and satisfaction with instruction higher for active learning online suggests that the preference for passive lectures on campus relies on elements outside of the lecture itself. That might include the lecture hall environment, the social physical presence of peers, or normalization of passive lectures as the expected mode for on-campus classes. This implies that there may be more buy-in for active learning online vs. in-person.

A second result from our survey is that student perceptions of affect and engagement are associated with students experiencing a greater diversity of learning modalities. We see this in two different results. First, in addition to the fact that classes that include active learning outperform classes that rely solely on passive methods, we find that on all measures besides distraction, the highest student ratings are associated with a combination of active and passive methods. Second, we find that these higher scores are associated with classes that make use of a larger number of different methods.

This second result suggests that students benefit from classes that make use of multiple different techniques, possibly invoking a combination of passive and active methods. However, it is unclear from our data whether this effect is associated specifically with combining active and passive methods, or if it is associated simply with the use of multiple different methods, irrespective of whether those methods are active, passive, or some combination. The problem is that the number of methods used is confounded with the diversity of methods (e.g., it is impossible for a classroom using only one method to use both active and passive methods). In an attempt to address this question, we looked separately at the effect of number and diversity of methods while holding the other constant. Across a large number of such comparisons, we found few statistically significant differences, which may be a consequence of the fact that each comparison focused on a small subset of the data.

Thus, our data suggests that using a greater diversity of learning methods in the classroom may lead to better student outcomes. This is supported by research on student attention span which suggests varying delivery after 10–15 min to retain student’s attention ( Bradbury, 2016 ). It is likely that this is more relevant for online learning where students report high levels of distraction across methods, modalities, and platforms. Given that number and variety are key, and there are few passive learning methods, we can assume that some combination of methods that includes active learning improves student experience. However, it is not clear whether we should predict that this benefit would come simply from increasing the number of different methods used, or if there are benefits specific to combining particular methods. Disentangling these effects would be an interesting avenue for future research.

Students Value Social Presence in Remote Learning

Student responses across our open-ended survey questions show a striking difference in reasons for their preferences compared with traditional online learners who prefer flexibility ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). Students reasons for preferring in-person classes and synchronous remote classes emphasize the desire for social interaction and echo the research on the importance of social presence for learning in online courses.

Short et al. (1976) outlined Social Presence Theory in depicting students’ perceptions of each other as real in different means of telecommunications. These ideas translate directly to questions surrounding online education and pedagogy in regards to educational design in networked learning where connection across learners and instructors improves learning outcomes especially with “Human-Human interaction” ( Goodyear, 2002 , 2005 ; Tu, 2002 ). These ideas play heavily into asynchronous vs. synchronous learning, where Tu reports students having positive responses to both synchronous “real-time discussion in pleasantness, responsiveness and comfort with familiar topics” and real-time discussions edging out asynchronous computer-mediated communications in immediate replies and responsiveness. Tu’s research indicates that students perceive more interaction with synchronous mediums such as discussions because of immediacy which enhances social presence and support the use of active learning techniques ( Gunawardena, 1995 ; Tu, 2002 ). Thus, verbal immediacy and communities with face-to-face interactions, such as those in synchronous learning classrooms, lessen the psychological distance of communicators online and can simultaneously improve instructional satisfaction and reported learning ( Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997 ; Richardson and Swan, 2019 ; Shea et al., 2019 ). While synchronous learning may not be ideal for traditional online students and a subset of our participants, this research suggests that non-traditional online learners are more likely to appreciate the value of social presence.

Social presence also connects to the importance of social connections in learning. Too often, current systems of education emphasize course content in narrow ways that fail to embrace the full humanity of students and instructors ( Gay, 2000 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic leading to further social isolation for many students, the importance of social presence in courses, including live interactions that build social connections with classmates and with instructors, may be increased.

Limitations of These Data

Our undergraduate data consisted of 4,789 responses from 95 different countries, an unprecedented global scale for research on online learning. However, since respondents were followers of @unjadedjade who focuses on learning and wellness, these respondents may not represent the average student. Biases in survey responses are often limited by their recruitment techniques and our bias likely resulted in more robust and thoughtful responses to free-response questions and may have influenced the preference for synchronous classes. It is unlikely that it changed students reporting on remote learning pedagogical methods since those are out of student control.

Though we surveyed a global population, our design was rooted in literature assessing pedagogy in North American institutions. Therefore, our survey may not represent a global array of teaching practices.

This survey was sent out during the initial phase of emergency remote learning for most countries. This has two important implications. First, perceptions of remote learning may be clouded by complications of the pandemic which has increased social, mental, and financial stresses globally. Future research could disaggregate the impact of the pandemic from students’ learning experiences with a more detailed and holistic analysis of the impact of the pandemic on students.

Second, instructors, students and institutions were not able to fully prepare for effective remote education in terms of infrastructure, mentality, curriculum building, and pedagogy. Therefore, student experiences reflect this emergency transition. Single-modality courses may correlate with instructors who lacked the resources or time to learn or integrate more than one modality. Regardless, the main insights of this research align well with the science of teaching and learning and can be used to inform both education during future emergencies and course development for online programs that wish to attract traditional college students.

Global Student Voices Improve Our Understanding of the Experience of Emergency Remote Learning

Our survey shows that global student perspectives on remote learning agree with pedagogical best practices, breaking with the often-found negative reactions of students to these practices in traditional classrooms ( Shekhar et al., 2020 ). Our analysis of open-ended questions and preferences show that a majority of students prefer pedagogical approaches that promote both active learning and social interaction. These results can serve as a guide to instructors as they design online classes, especially for students whose first choice may be in-person learning. Indeed, with the near ubiquitous adoption of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote learning may be the default for colleges during temporary emergencies. This has already been used at the K-12 level as snow days become virtual learning days ( Aspergren, 2020 ).

In addition to informing pedagogical decisions, the results of this survey can be used to inform future research. Although we survey a global population, our recruitment method selected for students who are English speakers, likely majority female, and have an interest in self-improvement. Repeating this study with a more diverse and representative sample of university students could improve the generalizability of our findings. While the use of a variety of pedagogical methods is better than a single method, more research is needed to determine what the optimal combinations and implementations are for courses in different disciplines. Though we identified social presence as the major trend in student responses, the over 12,000 open-ended responses from students could be analyzed in greater detail to gain a more nuanced understanding of student preferences and suggestions for improvement. Likewise, outliers could shed light on the diversity of student perspectives that we may encounter in our own classrooms. Beyond this, our findings can inform research that collects demographic data and/or measures learning outcomes to understand the impact of remote learning on different populations.

Importantly, this paper focuses on a subset of responses from the full data set which includes 10,563 students from secondary school, undergraduate, graduate, or professional school and additional questions about in-person learning. Our full data set is available here for anyone to download for continued exploration: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId= doi: 10.7910/DVN/2TGOPH .

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GS: project lead, survey design, qualitative coding, writing, review, and editing. TN: data analysis, writing, review, and editing. CN and PB: qualitative coding. JW: data analysis, writing, and editing. CS: writing, review, and editing. EV and KL: original survey design and qualitative coding. PP: data analysis. JB: original survey design and survey distribution. HH: data analysis. MP: writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Minerva Schools at KGI for providing funding for summer undergraduate research internships. We also want to thank Josh Fost and Christopher V. H.-H. Chen for discussion that helped shape this project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full#supplementary-material

Aspergren, E. (2020). Snow Days Canceled Because of COVID-19 Online School? Not in These School Districts.sec. Education. USA Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/12/15/covid-school-canceled-snow-day-online-learning/3905780001/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Google Scholar

Bostock, S. J. (1998). Constructivism in mass higher education: a case study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 29, 225–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00066

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bradbury, N. A. (2016). Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 509–513. doi: 10.1152/advan.00109.2016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, B., Bastedo, K., and Howard, W. (2018). Exploring best practices for online STEM courses: active learning, interaction & assessment design. Online Learn. 22, 59–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i2.1369

Davis, D., Chen, G., Hauff, C., and Houben, G.-J. (2018). Activating learning at scale: a review of innovations in online learning strategies. Comput. Educ. 125, 327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.019

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Multicultural Education Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillingham, and Molinari, C. (2012). Online courses: student preferences survey. Internet Learn. 1, 36–45. doi: 10.18278/il.1.1.4

Gillis, A., and Krull, L. M. (2020). COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teach. Sociol. 48, 283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263

Goodyear, P. (2002). “Psychological foundations for networked learning,” in Networked Learning: Perspectives and Issues. Computer Supported Cooperative Work , eds C. Steeples and C. Jones (London: Springer), 49–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0181-9_4

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 21, 82–101. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1344

Gunawardena, C. N. (1995). Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int. J. Educ. Telecommun. 1, 147–166.

Gunawardena, C. N., and Zittle, F. J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. Am. J. Distance Educ. 11, 8–26. doi: 10.1080/08923649709526970

Harris, H. S., and Martin, E. (2012). Student motivations for choosing online classes. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060211

Levitz, R. N. (2016). 2015-16 National Online Learners Satisfaction and Priorities Report. Cedar Rapids: Ruffalo Noel Levitz, 12.

Mansinghka, V., Shafto, P., Jonas, E., Petschulat, C., Gasner, M., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2016). CrossCat: a fully Bayesian nonparametric method for analyzing heterogeneous, high dimensional data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–49. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69765-9_7

National Research Council (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, doi: 10.17226/9853

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2019). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Online Learn. 7, 68–88. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

Shea, P., Pickett, A. M., and Pelz, W. E. (2019). A Follow-up investigation of ‘teaching presence’ in the suny learning network. Online Learn. 7, 73–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i2.1856

Shekhar, P., Borrego, M., DeMonbrun, M., Finelli, C., Crockett, C., and Nguyen, K. (2020). Negative student response to active learning in STEM classrooms: a systematic review of underlying reasons. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 49, 45–54.

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Tu, C.-H. (2002). The measurement of social presence in an online learning environment. Int. J. E Learn. 1, 34–45. doi: 10.17471/2499-4324/421

Zull, J. E. (2002). The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning , 1st Edn. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Keywords : online learning, COVID-19, active learning, higher education, pedagogy, survey, international

Citation: Nguyen T, Netto CLM, Wilkins JF, Bröker P, Vargas EE, Sealfon CD, Puthipiroj P, Li KS, Bowler JE, Hinson HR, Pujar M and Stein GM (2021) Insights Into Students’ Experiences and Perceptions of Remote Learning Methods: From the COVID-19 Pandemic to Best Practice for the Future. Front. Educ. 6:647986. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.647986

Received: 30 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021; Published: 09 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Nguyen, Netto, Wilkins, Bröker, Vargas, Sealfon, Puthipiroj, Li, Bowler, Hinson, Pujar and Stein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geneva M. Stein, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Covid-19 and Beyond: From (Forced) Remote Teaching and Learning to ‘The New Normal’ in Higher Education

Advertisement

The Value of School: Educational Experiences and Maturational Growth Among Delinquent Youth

- Original Article

- Published: 16 July 2021

- Volume 7 , pages 385–419, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- David Abeling-Judge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9812-5199 1

438 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

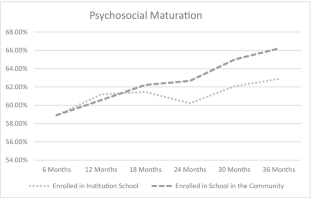

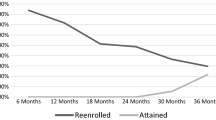

Maturational growth through psychosocial, adult role, identity, civic, and cognitive change has proven an insightful explanation of behavioral change among offender populations. It has evolved to address both endogenous growth, such as advancing age, and exogenous influences, such as family. The relevance of family bonding processes to maturation is well documented, in both psychological and criminological work, but an unexplored social process of relevance may be education. The current study uses the longitudinal Pathways to Desistance Study to explore the influence of school orientation variables and teacher bonding connections on specific domains of maturational growth as articulated by the integrated maturation theory. Analyses address the distinct influences of schools attended in the general community and schools attended while under placement in a secure juvenile detention facility. The current study identifies significant within-individual variation in various domains of maturity influenced by community school bonds, with corresponding patterns emerging for institutional school bonding experiences. Relationships with teachers produce some positive change, but the results are not consistent. Educational processes play a significant role in facilitating maturational growth, independent of family influences. This pattern emerges across different contexts, expands theoretical insight, and suggests focused policy interventions to promote desistance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Facilitating Maturation Through Social Bonds Among Delinquent Youth in the Transition to Adulthood

Can universal sel programs benefit universally effects of the positive action program on multiple trajectories of social-emotional and misconduct behaviors.

Routing back: social, psychological, and criminological influences on educational reengagement among youth offenders who drop out

Abeling-Judge, D. (2019). Stopping out and going back: The impact of educational attainment on criminal desistance among stopped-out offenders. Crime & Delinquency, 65 , 527–554.

Article Google Scholar

Abeling-Judge, D. (2020). Facilitating maturation through social bonds among delinquent youth in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 6 , 448–476.

Abeling-Judge, D. (2021). Social bonding experiences facilitating desistance in adolescence. Crime & Delinquency, 67 , 287–315.

Abrams, D. E. (2005). Reforming juvenile delinquency treatment to enhance rehabilitation, personal accountability, and public safety. Oregon Law Review, 84 , 1001–1094.

Google Scholar

Ahmed, W., Minnaert, A., van der Werf, G., & Kuyper, H. (2010). Perceived social support and early adolescents’ achievement: The mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39 , 36–46.

Bandura, A., Barbarnelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7 , 364–374.

Baumrind, D., & Moselle, K. A. (1985). A developmental perspective on adolescent drug abuse. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse, 4 , 41–67.

Benson, J. E., & Elder, G. H. (2011). Young adult identities and their pathways: A developmental and life course model. Developmental Psychology, 47 , 1646–1657.

Benson, J. E., Johnson, M. K., & Elder, G. H. (2012). The implications of adult identity for educational and work attainment in young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 48 , 1752–1758.

Bersani, B., & Doherty, E. E. (2018). Desistance from offending in the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Criminology, 1 , 311–334.

Bryan, J., Moore-Thomas, C., Gaenzle, S., Kim, J., Lin, C., & Na, G. (2012). The effects of school bonding on high school seniors’ academic achievement. Journal of Counseling and Development, 90 , 467–480.

Cate, H. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, motivation goals, and burnout in juvenile corrections and residential educational settings doctoral dissertation . Capella University.

Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: Why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18 , 741–760.

Cavanagh, C., & Cauffman, E. (2015). Viewing law and order: Mothers’ and sons’ justice system legitimacy attitudes and juvenile recidivism. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21 , 432–441.

Cernkovich, S., & Giordano, P. (1992). School bonding, race and delinquency. Criminology, 30 , 261–291.

Chassin, L., Dmitrieva, J., Modecki, K., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., Knight, G. P., & Losoya, S. H. (2010). Does adolescent alcohol and marijuana use predict suppressed growth in psychosocial maturity among male juvenile offenders? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24 , 48–60.

Chung, H., Little, M., & Steinberg, L. (2005). The transition to adulthood for adolescents in the juvenile justice system: A developmental perspective. In W. Osgood, M. Foster, C. Flanagan, & G. Ruth (Eds.), On your own without a net: The transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations (pp. 68–91). University of Chicago Press.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1999). The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 34 , 315–346.

Coker, D. C. (2020). Multiple regression analysis of noncognitive factors affecting academic achievement of juvenile delinquents Doctoral dissertation . American College of Education.

Conger, R., Ge, X., Elder, G., Jr., Lorenz, F., & Simons, R. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65 , 541–561.

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., Vespa, J., & Mosher, W. D. (2012). First marriages in the United States: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth . National Center for Health Statistics.

Cox, C., Visker, J., & Hartman, A. (2011). Educational faculty perceptions of the learning climate in a juvenile justice residential facility. Current Issues in Education, 14 , 1–16.

Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M. K., & Elder, G., Jr. (2004). Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioral and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationships. Sociology of Education, 77 , 60–81.

Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116 , 387–411.

Davis, J., & Sorensen, J. R. (2010). Disproportionate minority confinement of juveniles: A national examination of Black-White disparity in placements, 1997–2006. Crime & Delinquency, 59 , 115–139.

Day J.,C., Newburger E.,C. (2002). The big payoff: Educational attainment and synthetic estimates of work-life earnings. Congress. Current Population Reports

Dmitrieva, J., Monahan, K. C., Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (2012). Arrested development: The effects of incarceration on the development of psychosocial maturity. Development and Psychopathology, 24 , 1073–1090.

Dumais, S. A. (2009). Cohort and gender differences in extracurricular participation: The relationship between activities, math achievement, and college expectations. Sociological Spectrum, 29 , 72–100.

Ellison, J. M., Owings, W., & Kaplan, L. S. (2017). State fiscal effort and juvenile incarceration rates: Are we misdirecting our investment in human capital? Journal of Education Finance, 43 , 45–64.

Enders, C. K., Du, H., & Keller, B. T. (2019). A model-based imputation procedure for multilevel regression models with random coefficients, interaction effects, and nonlinear terms. Psychological Methods, 25 , 88–112.

Enders, C. K., Keller, B. T., & Levy, R. (2018). A fully conditional specification approach to multilevel imputation of categorical and continuous variables. Psychological Methods, 23 , 298–317.

Engstrom, R. S., & Scott, D. (2020). Juvenile institutional misconduct: Examining the role of educational attainment and academic achievement. Crime & Delinquency, 66 , 663–686.

Feldman, S. S., & Weinberger, D. A. (1994). Self-restraint as a mediator of family influences on boys’ delinquent behavior: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 65 , 195–211.

Fine, A., Wolff, K. T., Baglivio, M. T., Piquero, A. R., Frick, P. J., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2018). Does the effect of justice system attitudes on adolescent crime vary based on psychosocial maturity? Child Development, 89 , 468–479.

Ford, J., Kerig, P., Desai, N., & Feierman, J. (2016). Psychosocial interventions for traumatized youth in the juvenile justice system: Research, evidence base, and clinical/legal challenges. OJJDP Journal of Juvenile Justice, 5 , 31–49.

Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, S. A., & Rudolph, J. L. (2002). Gender, crime, and desistance: Toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 107 , 990–1064.

Gorman-Smith, D., & Tolan, P. (1998). The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner city youth. Development and Psychopathology, 10 , 101–116.

Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime . Stanford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Greenberger, E., Bond, L. (1976). Technical manual for the psychosocial maturity inventory. Unpublished manuscript, Program in Social Ecology, University of California

Greenberger, E., Josselson, R., Knerr, C., & Knerr, B. (1974). The measurement and structure of psychosocial maturity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 4 , 127–143.

Groot, W., & van den Brink, H. M. (2010). The effects of education on crime. Applied Economics, 42 , 279–289.

Hansen, K. (2003). Education and the crime-age profile. British Journal of Criminology, 43 , 141–168.

Hawkins, J. D., Guo, J., Hill, K. G., Battin-Pearson, S., & Abbott, R. (2001). Long-term effects of the Seattle social development intervention on school bonding trajectories. Applied Developmental Science, 5 , 225–236.

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29 , 319–335.

Hipwell, A. E., Beeney, J., Ye, F., Gebreselassie, S. H., Stalter, M. R., Ganesh, D., Keenan, K., & Stepp, S. D. (2018). Police contacts, arrests and decreasing self-control and personal responsibility among female adolescents. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59 , 1252–1260.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency . University of California Press.

Hockenberry, S., sSladky, A. (2020). Juvenile residential facility census 2018: Selected findings. Juvenile Justice Statistics – National Report Series Bulletin. U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Houchins, D. E., Puckett-Patterson, D., Crosby, S., Shippen, M. E., & Jolivette, K. (2009). Barriers and facilitators to providing incarcerated youth with a quality education. Preventing School Failure, 53 , 159–166.

Hyde, L. W., Shaw, D. S., & Moilanen, K. L. (2010). Developmental precursors of moral disengagement and the role of moral disengagement in the development of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38 , 197–209.

Jaggi, L., & Kliewer, W. (2020). Reentry of incarcerated juveniles: Correctional education as a turning point across juvenile and adult facilities. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47 , 1348–1370.

Kelly, J. B. (2000). Children’s adjustment in conflicted marriage and divorce: A decade of review of research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39 , 963–973.

Kim-Spoon, J., Maciejewski, D., Lee, J., Deater-Deckard, K., & King-Cases, B. (2017). Longitudinal associations among family environment, neural cognitive control, and social competence among adolescents. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 26 , 69–76.

Kiriakidis, S. P. (2008). Moral disengagement: Relation to delinquency and independence from indices of social dysfunction. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52 , 571–583.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (1993). Turning points in the life course: Why change matters to the study of crime. Criminology, 31 , 301–325.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70 . Harvard University Press.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. The Journal of School Health, 74 , 274–283.

Lochner, L. (2004). Education, work, and crime: A human capital approach. International Economic Review, 45 , 811–843.

Luna, B., & Sweeney, J. A. (2001). Studies of brain and cognitive maturation through childhood and adolescence: A strategy for testing neurodevelopmental hypotheses. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27 , 443–455.

Machin, S., Marie, O., & Vujic, S. (2011). The crime reducing effect of education. The Economic Journal, 121 , 463–484.

Macoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1980). Sex differences in aggression: A rejoinder and reprise. Child Development, 51 , 964–980.

Mallett, C. A. (2014). Youthful offending and delinquency: The comorbid impact of maltreatment, mental health problems, and learning disabilities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31 , 369–392.

Margolin, G., & Gordis, E. B. (2000). The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology, 51 , 445–479.

McCord, E., Widom, C. S., & Crowell, N. A. (2001). Juvenile Crime, Juvenile Justice . The National Academies Press.

McCuish, E., Lussier, P., & Rocque, M. (2020). Maturation beyond age: Interrelationships among psychosocial, adult role, and identity maturation and their implications for desistance from crime. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49 , 479–493.