Socialism vs. Capitalism: What Is the Difference?

Fokusiert / Getty Images

- U.S. Economy

- Supply & Demand

- Archaeology

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Socialism and capitalism are the two main economic systems used in developed countries today. The main difference between capitalism and socialism is the extent to which the government controls the economy.

Key Takeaways: Socialism vs. Capitalism

- Socialism is an economic and political system under which the means of production are publicly owned. Production and consumer prices are controlled by the government to best meet the needs of the people.

- Capitalism is an economic system under which the means of production are privately owned. Production and consumer prices are based on a free-market system of “supply and demand.”

- Socialism is most often criticized for its provision of social services programs requiring high taxes that may decelerate economic growth.

- Capitalism is most often criticized for its tendency to allow income inequality and stratification of socio-economic classes.

Socialist governments strive to eliminate economic inequality by tightly controlling businesses and distributing wealth through programs that benefit the poor, such as free education and healthcare. Capitalism, on the other hand, holds that private enterprise utilizes economic resources more efficiently than the government and that society benefits when the distribution of wealth is determined by a freely-operating market.

The United States is generally considered to be a capitalist country, while many Scandinavian and Western European countries are considered socialist democracies. In reality, however, most developed countries—including the U.S.—employ a mixture of socialist and capitalist programs.

Capitalism Definition

Capitalism is an economic system under which private individuals own and control businesses, property, and capital—the “means of production.” The volume of goods and services produced is based on a system of “ supply and demand ,” which encourages businesses to manufacture quality products as efficiently and inexpensively as possible.

In the purest form of capitalism— free market or laissez-faire capitalism—individuals are unrestrained in participating in the economy. They decide where to invest their money, as well as what to produce and sell at what prices. True laissez-faire capitalism operates without government controls. In reality, however, most capitalist countries employ some degree of government regulation of business and private investment.

Capitalist systems make little or no effort to prevent income inequality . Theoretically, financial inequality encourages competition and innovation, which drive economic growth. Under capitalism, the government does not employ the general workforce. As a result, unemployment can increase during economic downturns . Under capitalism, individuals contribute to the economy based on the needs of the market and are rewarded by the economy based on their personal wealth.

Socialism Definition

Socialism describes a variety of economic systems under which the means of production are owned equally by everyone in society. In some socialist economies, the democratically elected government owns and controls major businesses and industries. In other socialist economies, production is controlled by worker cooperatives. In a few others, individual ownership of enterprise and property is allowed, but with high taxes and government control.

The mantra of socialism is, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his contribution.” This means that each person in society gets a share of the economy’s collective production—goods and wealth—based on how much they have contributed to generating it. Workers are paid their share of production after a percentage has been deducted to help pay for social programs that serve “the common good.”

In contrast to capitalism, the main concern of socialism is the elimination of “rich” and “poor” socio-economic classes by ensuring an equal distribution of wealth among the people. To accomplish this, the socialist government controls the labor market, sometimes to the extent of being the primary employer. This allows the government to ensure full employment even during economic downturns.

The Socialism vs. Capitalism Debate

The key arguments in the socialism vs. capitalism debate focus on socio-economic equality and the extent to which the government controls wealth and production.

Ownership and Income Equality

Capitalists argue that private ownership of property (land, businesses, goods, and wealth) is essential to ensuring the natural right of people to control their own affairs. Capitalists believe that because private-sector enterprise uses resources more efficiently than government, society is better off when the free market decides who profits and who does not. In addition, private ownership of property makes it possible for people to borrow and invest money, thus growing the economy.

Socialists, on the other hand, believe that property should be owned by everyone. They argue that capitalism’s private ownership allows a relatively few wealthy people to acquire most of the property. The resulting income inequality leaves those less well off at the mercy of the rich. Socialists believe that since income inequality hurts the entire society, the government should reduce it through programs that benefit the poor such as free education and healthcare and higher taxes on the wealthy.

Consumer Prices

Under capitalism, consumer prices are determined by free market forces. Socialists argue that this can enable businesses that have become monopolies to exploit their power by charging excessively higher prices than warranted by their production costs.

In socialist economies, consumer prices are usually controlled by the government. Capitalists say this can lead to shortages and surpluses of essential products. Venezuela is often cited as an example. According to Human Rights Watch, “most Venezuelans go to bed hungry.” Hyperinflation and deteriorating health conditions under the socialist economic policies of President Nicolás Maduro have driven an estimated 3 million people to leave the country as food became a political weapon.

Efficiency and Innovation

The profit incentive of capitalism’s private ownership encourages businesses to be more efficient and innovative, enabling them to manufacture better products at lower costs. While businesses often fail under capitalism, these failures give rise to new, more efficient businesses through a process known as “creative destruction.”

Socialists say that state ownership prevents business failures, prevents monopolies, and allows the government to control production to best meet the needs of the people. However, say capitalists, state ownership breeds inefficiency and indifference as labor and management have no personal profit incentive.

Healthcare and Taxation

Socialists argue that governments have a moral responsibility to provide essential social services. They believe that universally needed services like healthcare, as a natural right, should be provided free to everyone by the government. To this end, hospitals and clinics in socialist countries are often owned and controlled by the government.

Capitalists contend that state, rather than private control, leads to inefficiency and lengthy delays in providing healthcare services. In addition, the costs of providing healthcare and other social services force socialist governments to impose high progressive taxes while increasing government spending, both of which have a chilling effect on the economy.

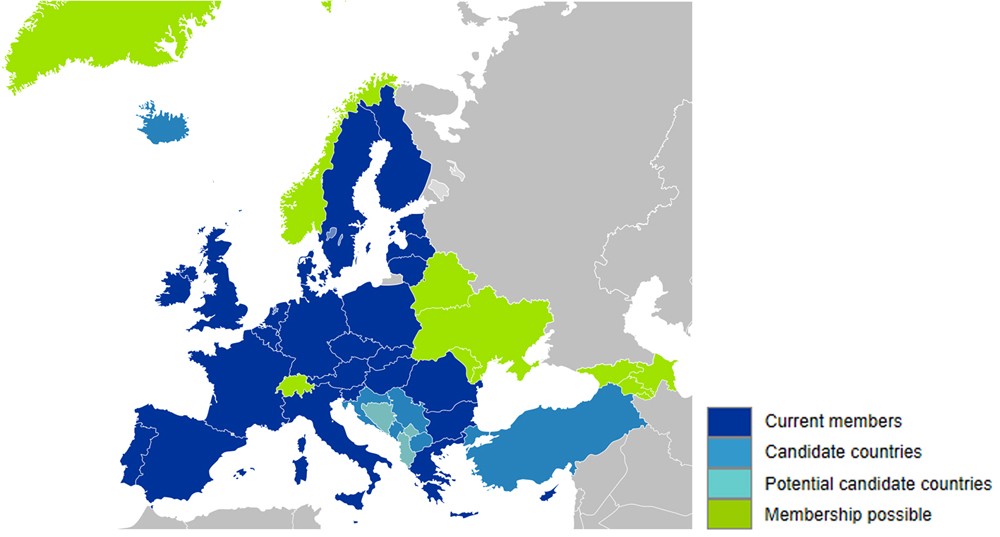

Capitalist and Socialist Countries Today

Today, there are few if any developed countries that are 100% capitalist or socialist. Indeed, the economies of most countries combine elements of socialism and capitalism.

In Norway, Sweden, and Denmark—generally considered socialist—the government provides healthcare, education, and pensions. However, private ownership of property creates a degree of income inequality. An average of 65% of each nation’s wealth is held by only 10% of the people—a characteristic of capitalism.

The economies of Cuba, China, Vietnam, Russia, and North Korea incorporate characteristics of both socialism and communism .

While countries such as Great Britain, France, and Ireland have strong socialist parties, and their governments provide many social support programs, most businesses are privately owned, making them essentially capitalist.

The United States, long considered the prototype of capitalism, isn’t even ranked in the top 10 most capitalist countries, according to the conservative think tank Heritage Foundation. The U.S. drops in the Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom due to its level of government regulation of business and private investment.

Indeed, the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution sets one the nation’s goals to be “promote the general welfare.” In order to accomplish this, the United States employs certain socialist-like social safety net programs , such as Social Security, Medicare, food stamps , and housing assistance.

Contrary to popular belief, socialism did not evolve from Marxism . Societies that were to varying degrees “socialist” have existed or have been imagined since ancient times. Examples of actual socialist societies that predated or were uninfluenced by German philosopher and economic critic Karl Marx were Christian monastic enclaves during and after the Roman Empire and the 19th-century utopian social experiments proposed by Welsh philanthropist Robert Owen. Premodern or non-Marxist literature that envisioned ideal socialist societies include The Republic by Plato , Utopia by Sir Thomas More, and Social Destiny of Man by Charles Fourier.

Socialism vs. Communism

Unlike socialism, communism is both an ideology and a form of government. As an ideology, it predicts the establishment of a dictatorship controlled by the working-class proletariat established through violent revolution and the eventual disappearance of social and economic class and state. As a form of government, communism is equivalent in principle to the dictatorship of the proletariat and in practice to a dictatorship of communists. In contrast, socialism is not tied to any specific ideology. It presupposes the existence of the state and is compatible with democracy and allows for peaceful political change.

Capitalism

While no single person can be said to have invented capitalism, capitalist-like systems existed as far back as ancient times. The ideology of modern capitalism is usually attributed to Scottish political economist Adam Smith in his classic 1776 economic treatise The Wealth of Nations. The origins of capitalism as a functional economic system can be traced to 16th to 18th century England, where the early Industrial Revolution gave rise to mass enterprises, such as the textile industry, iron, and steam power . These industrial advancements led to a system in which accumulated profit was invested to increase productivity—the essence of capitalism.

Despite its modern status as the world’s predominant economic system, capitalism has been criticized for several reasons throughout history. These include the unpredictable and unstable nature of capitalist growth, social harms, such as pollution and abusive treatment of workers, and forms of economic disparity, such as income inequality . Some historians connect profit-driven economic models such as capitalism to the rise of oppressive institutions such as human enslavement , colonialism , and imperialism .

Sources and Further Reference

- “Back to Basics: What is Capitalism?” International Monetary Fund , June 2015, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2015/06/basics.htm.

- Fulcher, James. “Capitalism A Very Short Introduction.” Oxford, 2004, ISBN 978-0-19-280218-7.

- de Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital.” International Monetary Fund , March, 2001, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/03/desoto.htm.

- Busky, Donald F. “Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey.” Praeger, 2000, ISBN 978-0-275-96886-1.

- Nove, Alec. “The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited.” Routledge, 1992, ISBN-10: 0044460155.

- Newport, Frank. “The Meaning of ‘Socialism’ to Americans Today.” Gallup , October 2018), https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/243362/meaning-socialism-americans-today.aspx.

- The Differences Between Communism and Socialism

- A Mixed Economy: The Role of the Market

- What Is Socialism? Definition and Examples

- The Main Points of "The Communist Manifesto"

- The Three Historic Phases of Capitalism and How They Differ

- What Is Capitalism?

- What Is Communism? Definition and Examples

- 5 Things That Make Capitalism "Global"

- The Critical View on Global Capitalism

- A List of Current Communist Countries in the World

- America's Capitalist Economy

- All About Marxist Sociology

- The Globalization of Capitalism

- What Is Neoliberalism? Definition and Examples

- SBA Offers Online 8(a) Program Application

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Scott Atlas

- Thomas Sargent

- Stephen Kotkin

- Michael McConnell

- Morris P. Fiorina

- John F. Cogan

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- National Security, Technology & Law

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press, capitalism vs. socialism.

Over the last century countries have experimented with variations on both capitalism and socialsm. So how do socialism, capitalism, and their many variants compare?

From economic shutdowns to trillions of dollars in new government spending, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic led to a dramatic increase in government action. While much of the increase was temporary, there is now a growing desire to further expand government. We see calls for single-payer health care systems, expanded child-care subsidies, and trillions of dollars in federal infrastructure investments.

Arguments about what government should and should not do are not new. We regularly see them in the debates over the merits of socialism versus free market capitalism. While these debates are often in the abstract, over the last century countries have experimented with variations on both economic systems. The Hoover Institution’s Human Prosperity Project critically examined many of these experiments to see which economic system is best for human flourishing. The video below describes the project’s objectives:

So how do socialism, capitalism, and their many variants compare?

Part 2: How do socialism and capitalism affect income and opportunities?

Delivering broad-based prosperity should be the primary goal of all economic systems, but not all systems deliver the same results. Supporters of capitalism argue that free markets give people—entrepreneurs, investors, and workers—the right incentives to create goods and services that people value. The result is higher standards of living. Those sympathetic to socialism, however, respond that capitalism may produce wealth for some, but without government involvement in the economy many are left behind.

In his Human Prosperity Project essay Socialism, Capitalism, and Income economist Edward Lazear analyzed decades of income trends across 162 countries. He studied how incomes for low and high earners changed as countries shifted from government-controlled economies to more market-oriented economies. His conclusion?

The historical record provides evidence on how countries have fared under the two extreme systems as well as under intermediate cases, where countries adopt primarily private ownership and economic freedom but couple that with a large government sector and transfers. The general evidence suggests that both across countries and over time within a country, providing more economic freedom improves the incomes of all groups, including the lowest group.

Lazear points to several specific examples. First, China: in the 1980s, the Chinese Communist government began to adopt market-based reforms. Lazear finds that the market reforms, as skeptics of capitalism would predict, did increase income inequality. But, more importantly, the market reforms lifted millions of people out of poverty. Lazear notes:

Today, the poorest Chinese earn five times as much as they did just two decades earlier. Throughout the 1980s and before, a large fraction of the Chinese population lived in abject poverty. Today’s poor in China remain poor by developed-country standards, but there is no denying that they are far better off than they were even two decades ago. Indeed, the rapid lifting of so many out of the worst state of poverty is likely the greatest change in human welfare in world history.

As the video below highlights, market reforms led to similar economic miracles in India, Chile, and South Korea:

Part 3: What about mixed economies?

Of course, most modern-day critics of capitalism are not advocating for complete government control over the economy. They don’t want the economic policies of the Soviet Union or early Communist China; instead, they point to nations with mixed economies to emulate, such as those featuring social democracy. So how do these policies affect incomes and opportunities?

Economist Lee Ohanian compares the labor market policies of Europe and the United States in his essay The Effect of Economic Freedom on Labor Market Efficiency and Performance . Compared to the United States, European nations have higher minimum wages, stricter rules that prevent the firing of workers, and high rates of unionization. These rules are intended to protect workers, but Ohanian finds that they discourage employment and result in lower compensation rates. His analysis indicates:

These findings have important implications for economic policy making. They indicate that policies that enhance the free and efficient operation of the labor market significantly expand opportunities and increase prosperity. Moreover, they suggest that economic policy reforms can substantially improve economic performance in countries with heavily regulated labor markets and high tax rates.

The video below highlights some of Ohanian’s key findings:

What about the effects of income redistribution and the taxes that pay for it? Supporters argue that these programs keep people out of poverty. Critics, however, argue that financing these systems comes with high costs both to taxpayers and to recipients.

In their essay Taxation, Individual Actions, and Economic Prosperity: A Review , Joshua Rauh and Gregory Kearney consider the effects of raising tax rates on high-income Americans to finance new government spending. They examine the effects of income and wealth taxes in Europe. They find that wealth taxes and high income tax rates discourage high-income filers from investing in a country, which ultimately reduces economic growth. Thus, calls in the United States to increase income and wealth taxes “come despite a body of evidence showing that the country is already one of the more progressive tax regimes in the world, that wealth confiscation results in worse outcomes for the broader economy.”

The long-term consequences of redistribution don’t fall just on taxpayers. Such transfer systems also create incentives for individuals to leave or stay out of the work force. In their contribution to the Human Prosperity Project , economist John Cogan and Daniel Heil consider the effects of Universal Basic Income (UBI) programs, which would provide a “no-strings-attached” cash benefit to families. They find that modern UBI proposals in the United States would either prove costly—requiring tax rates that would reduce incentives to work and invest—or would require steep phase-out provisions that punish recipients who try to re-enter the workforce. In either case, the result is that UBI programs are likely to reduce employment rates, ultimately depriving recipients of long-term economic opportunities.

Part 4: What about other aspects of human flourishing?

Human flourishing is more than material prosperity. For example, it requires a clean environment and access to good health care.

It might seem that socialist economies—where government controls the means of production—would have better environmental track records. Yet the evidence suggests the opposite. In his essay Environmental Markets vs. Environmental Socialism: Capturing Prosperity and Environmental Quality Economist , Terry Anderson summarizes the literature on economic systems’ effects on the environment. He points to research showing that countries with more economic freedom tend to have better environmental outcomes:

Seth Norton calculated the statistical relationship between various freedom indexes and environmental improvements. His results show that institutions—especially property rights and the rule of law—are key to human well-being and environmental quality. Dividing a sample of countries into groups with low, medium, and high economic freedom and similar categories for the rule of law, Norton showed that in all cases except water pollution, countries with low economic freedom are worse off than those in countries with moderate economic freedom, while in all cases those in countries with high economic freedom are better off than those in countries with medium economic freedom. A similar pattern is evident for the rule-of-law measures.

Anderson explains this surprising result with the adage that “no one washes a rental car.” In free-market societies, property rights give individuals incentive to protect and preserve the resources they own. In countries without these property rights provisions, no one has the right incentives, much like no one has the incentive to wash a rental car (except the rental car companies). The video below further explains why free markets and cleaner environments go hand and hand.

What about health care? Many developed nations that have generally free economies have still opted for government-run health care. The programs vary by country. Even in the United States, the government plays a large role in health care. Large government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid provide health care to low-income families, the disabled, and seniors. Nevertheless, relative to most developed nations, the United States relies far more heavily on the private sector and markets.

In his essay The Costs of Regulation and Centralization in Health Care Dr. Scott Atlas compares health care in the United States with that in other developed nations. The United States consistently ranks high across a variety of quality metrics. The system offers shorter wait times and faster access to life-saving drugs and medical equipment. The result is that the US system tends to deliver better medical outcomes than other developed nations. Watch this video to learn more:

Part 5: Conclusion

We’ve seen that whether we look at income statistics or environmental outcomes, economies with freer markets tend to have better outcomes. Nevertheless, there still may be unseen dimensions of economic systems that these statistics don’t address. Is there another way to determine which system is best for human flourishing?

Perhaps the best method is to observe where people choose to live when offered the choice. In his essay Leaving Socialism Behind: A Lesson from German History , Russell Berman catalogues widespread immigration from East Germany to West Germany during the Cold War. Watch this video to learn its causes:

Citations and Additional Reading

- Why did liberal democracies succeed while communist nations failed in the twentieth century? Hoover Institution senior fellow Peter Berkowitz provides an answer in his essay Capitalism, Socialism, and Freedom .

- In his essay Socialism vs. The American Constitutional Structure: The Advantages of Decentralization and Federalism , John Yoo highlights the constitutional provisions that would make it difficult for the United States to adopt widescale socialist policies.

- Explore the other Human Prosperity Project essays here .

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Socialism is a rich tradition of political thought and practice, the history of which contains a vast number of views and theories, often differing in many of their conceptual, empirical, and normative commitments. In his 1924 Dictionary of Socialism , Angelo Rappoport canvassed no fewer than forty definitions of socialism, telling his readers in the book’s preface that “there are many mansions in the House of Socialism” (Rappoport 1924: v, 34–41). To take even a relatively restricted subset of socialist thought, Leszek Kołakowski could fill over 1,300 pages in his magisterial survey of Main Currents of Marxism (Kołakowski 1978 [2008]). Our aim is of necessity more modest. In what follows, we are concerned to present the main features of socialism, both as a critique of capitalism, and as a proposal for its replacement. Our focus is predominantly on literature written within a philosophical idiom, focusing in particular on philosophical writing on socialism produced during the past forty-or-so years. Furthermore, our discussion concentrates on the normative contrast between socialism and capitalism as economic systems. Both socialism and capitalism grant workers legal control of their labor power, but socialism, unlike capitalism, requires that the bulk of the means of production workers use to yield goods and services be under the effective control of workers themselves, rather than in the hands of the members of a different, capitalist class under whose direction they must toil. As we will explain below, this contrast has been articulated further in different ways, and socialists have not only made distinctive claims regarding economic organization but also regarding the processes of transformation fulfilling them and the principles and ideals orienting their justification (including, as we will see, certain understandings of freedom, equality, solidarity, and democracy). [ 1 ]

1. Socialism and Capitalism

2. three dimensions of socialist views, 3.1 socialist principles, 3.2.1 exploitation, 3.2.2 interference and domination, 3.2.3 alienation, 3.2.4 inefficiency, 3.2.5 liberal egalitarianism and inequality in capitalism, 4.1 central and participatory planning, 4.2 market socialism, 4.3 less comprehensive, piecemeal reforms, 5. socialist transformation (dimension diii), other internet resources, related entries.

Socialism is best defined in contrast with capitalism, as socialism has arisen both as a critical challenge to capitalism, and as a proposal for overcoming and replacing it. In the classical, Marxist definition (G.A. Cohen 2000a: ch.3; Fraser 2014: 57–9), capitalism involves certain relations of production . These comprise certain forms of control over the productive forces —the labor power that workers deploy in production and the means of production such as natural resources, tools, and spaces they employ to yield goods and services—and certain social patterns of economic interaction that typically correlate with that control. Capitalism displays the following constitutive features:

(i) The bulk of the means of production is privately owned and controlled . (ii) People legally own their labor power. (Here capitalism differs from slavery and feudalism, under which systems some individuals are entitled to control, whether completely or partially, the labor power of others). (iii) Markets are the main mechanism allocating inputs and outputs of production and determining how societies’ productive surplus is used, including whether and how it is consumed or invested.

An additional feature that is typically present wherever (i)–(iii) hold, is that:

(iv) There is a class division between capitalists and workers, involving specific relations (e.g., whether of bargaining, conflict, or subordination) between those classes, and shaping the labor market, the firm, and the broader political process.

The existence of wage labor is often seen by socialists as a necessary condition for a society to be counted as capitalist (Schweickart 2002 [2011: 23]). Typically, workers (unlike capitalists) must sell their labor power to make a living. They sell it to capitalists, who (unlike the workers) control the means of production. Capitalists typically subordinate workers in the production process, as capitalists have asymmetric decision-making power over what gets produced and how it gets produced. Capitalists also own the output of production and sell it in the market, and they control the predominant bulk of the flow of investment within the economy. The relation between capitalists and workers can involve cooperation, but also relations of conflict (e.g., regarding wages and working conditions). This more-or-less antagonistic power relationship between capitalists and workers plays out in a number of areas, within production itself, and in the broader political process, as in both the economic and political domains decisions are made about who does what, and who gets what.

There are possible economic systems that would present exceptions, in which (iv) does not hold even if (i), (ii) and (iii) all obtain. Examples here are a society of independent commodity producers or a property-owning democracy (in which individuals or groups of workers own firms). There is debate, however, as to how feasible—accessible and stable—these are in a modern economic environment (O’Neill 2012).

Another feature that is also typically seen as arising where (i)–(iii) hold is this:

(v) Production is primarily oriented to capital accumulation (i.e., economic production is primarily oriented to profit rather than to the satisfaction of human needs). (G.A. Cohen 2000a; Roemer 2017).

In contrast to capitalism, socialism can be defined as a type of society in which, at a minimum, (i) is turned into (i*):

(i*) The bulk of the means of production is under social, democratic control.

Changes with regard to features (ii), (iii), and (v) are hotly debated amongst socialists. Regarding (ii), socialists retain the view that workers should control their labor power, but many do not affirm the kind of absolute, libertarian property rights in labor power that would, e.g., prevent taxation or other forms of mandatory contribution to cater for the basic needs of others (G.A. Cohen 1995). Regarding (iii), there is a recent burgeoning literature on “market socialism”, which we discuss below, where proposals are advanced to create an economy that is socialist but nevertheless features extensive markets. Finally, regarding (v), although most socialists agree that, due to competitive pressures, capitalists are bound to seek profit maximization, some puzzle over whether when they do this, it is “greed and fear” and not the generation of resources to make others besides themselves better-off that is the dominant, more basic drive and hence the degree to which profit-maximization should be seen as a normatively troubling phenomenon. (See Steiner 2014, in contrast with G.A. Cohen 2009, discussing the case of capitalists amassing capital to give it away through charity.) Furthermore, some socialists argue that the search for profits in a market socialist economy is not inherently suspicious (Schweickart 2002 [2011]). Most socialists, however, tend to find the profit motive problematic.

An important point about this definition of socialism is that socialism is not equivalent to, and is arguably in conflict with, statism. (i*) involves expansion of social power—power based on the capacity to mobilize voluntary cooperation and collective action—as distinct from state power—power based on the control of rule-making and rule enforcing over a territory—as well of economic power—power based on the control of material resources (Wright 2010). If a state controls the economy but is not in turn democratically controlled by the individuals engaged in economic life, what we have is some form of statism, not socialism (see also Arnold n.d. in Other Internet Resources (OIR) ; Dardot & Laval 2014).

When characterizing socialist views, it is useful to distinguish between three dimensions of a conception of a social justice (Gilabert 2017a). We identify these three dimensions as:

(DI) the core ideals and principles animating that conception of justice; (DII) the social institutions and practices implementing the ideals specified at DI; (DIII) the processes of transformation leading agents and their society from where they are currently, to the social outcome specified in DII.

The characterization of capitalism and socialism in the previous section focuses on the social institutions and practices constituting each form of society (i.e., on DII). We step back from this institutional dimension in section 3, below, to consider the central normative commitments of socialism (DI) and to survey their deployment in the socialist critique of capitalism. We then, in section 4 , engage in a more detailed discussion of accounts of the institutional shape of socialism (DII), exploring the various proposed implementations of socialist ideals and principles outlined under DI. We turn to accounts of the transition to socialism (DIII) in section 5 .

3. Socialist Critiques of Capitalism and their Grounds (Dimension DI)

Socialists have condemned capitalism by alleging that it typically features exploitation, domination, alienation, and inefficiency. Before surveying these criticisms, it is important to note that they rely on various ideals and principles at DI. We first mention these grounds briefly, and then elaborate on them as we discuss their engagement in socialists’ critical arguments. We set aside the debate, conducted mostly during the 1980s and largely centered on the interpretation of Marx’s writings, as to whether the condemnation of capitalism and the advocacy for socialism relies (or should rely), on moral grounds (Geras 1985; Lukes 1985; Peffer 1990). Whereas some Marxist socialists take the view that criticism of capitalism can be conducted without making use—either explicitly or implicitly—of arguments with a moral foundation, our focus is on arguments that do rely on such grounds.

Socialists have deployed ideals and principles of equality, democracy, individual freedom, self-realization, and community or solidarity. Regarding equality , they have proposed strong versions of the principle of equality of opportunity according to which everyone should have “broadly equal access to the necessary material and social means to live flourishing lives” (Wright 2010: 12; Roemer 1994a: 11–4; Nielsen 1985). Some, but by no means all, socialists construe equality of opportunity in a luck-egalitarian way, as requiring the neutralization of inequalities of access to advantage that result from people’s circumstances rather than their choices (G.A. Cohen 2009: 17–9). Socialists also embrace the ideal of democracy , requiring that people have “broadly equal access to the necessary means to participate meaningfully in decisions” affecting their lives (Wright 2010: 12; Arnold n.d. [OIR] : sect. 4). Many socialists say that democratic participation should be available not only at the level of governmental institutions, but also in various economic arenas (such as within the firm). Third, socialists are committed to the importance of individual freedom . This commitment includes versions of the standard ideas of negative liberty and non-domination (requiring security from inappropriate interference by others). But it also typically includes a more demanding, positive form of self-determination, as the “real freedom” of being able to develop one’s own projects and bring them to fruition (Elster 1985: 205; Gould 1988: ch. 1; Van Parijs 1995: ch. 1; Castoriadis 1979). An ideal of self-realization through autonomously chosen activities featuring people’s development and exercise of their creative and productive capacities in cooperation with others sometimes informs socialists’ positive views of freedom and equality—as in the view that there should be a requirement of access to the conditions of self-realization at work (Elster 1986: ch. 3). Finally, and relatedly, socialists often affirm an idea of community or solidarity , according to which people should organize their economic life so that they treat the freedom and well-being of others as intrinsically significant. People should recognize positive duties to support other people, or, as Einstein (1949) put it, a “sense of responsibility for [their] fellow men”. Or, as Cohen put it, people should “care about, and, where necessary and possible, care for, one another, and, too, care that they care about one another” (G.A. Cohen 2009: 34–5). Community is sometimes presented as a moral ideal which is not itself a demand of justice but can be used to temper problematic results permitted by some demands of justice (such as the inequalities of outcome permitted by a luck-egalitarian principle of equality of opportunity (G.A. Cohen 2009)). However, community is sometimes presented within socialist views as a demand of justice itself (Gilabert 2012). Some socialists also take solidarity as partly shaping a desirable form of “social freedom” in which people are able not only to advance their own good but also to act with and for others (Honneth 2015 [2017: ch. I]).

Given the diversity of fundamental principles to which socialists commonly appeal, it is perhaps unsurprising that few attempts have been made to link these principles under a unified framework. A suggested strategy has been to articulate some aspects of them as requirements flowing from what we might call the Abilities / Needs Principle, following Marx’s famous dictum, in The Critique of the Gotha Program , that a communist society should be organized so as to realize the goals of producing and distributing “From each according to [their] abilities, to each according to [their] needs”. This principle, presented with brevity and in the absence of much elaboration by Marx (Marx 1875 [1978b: 531]) has been interpreted in different ways. One, descriptive interpretation simply takes it to be a prediction of how people will feel motivated to act in a socialist society. Another, straightforwardly normative interpretation construes the Marxian dictum as stating duties to contribute to, and claims to benefit from, the social product—addressing the allocation of both the burdens and benefits of social cooperation. Its fulfillment would, in an egalitarian and solidaristic fashion, empower people to live flourishing lives (Carens 2003, Gilabert 2015). The normative principle itself has also been interpreted as an articulation of the broader, and more basic, idea of human dignity. Aiming at solidaristic empowerment , this idea could be understood as requiring that we support people in the pursuit of a flourishing life by not blocking, and by enabling, the development and exercise of their valuable capacities, which are at the basis of their moral status as agents with dignity (Gilabert 2017b).

3.2 Socialist Charges against Capitalism

The first typical charge leveled by socialists is that capitalism features the exploitation of wage workers by their capitalist employers. Exploitation has been characterized in two ways. First, in the so-called “technical” Marxist characterization, workers are exploited by capitalists when the value embodied in the goods they can purchase with their wages is inferior to the value embodied in the goods they produce—with the capitalists appropriating the difference. To maximize the profit resulting from the sale of what the workers produce, capitalists have an incentive to keep wages low. This descriptive characterization, which focuses on the flow of surplus labor from workers to capitalists, differs from another common, normative characterization of exploitation, according to which exploitation involves taking unfair, wrongful, or unjust advantage of the productive efforts of others. An obvious question is when, if ever, incidents of exploitation in the technical sense involve exploitation in the normative sense. When is the transfer of surplus labor from workers to capitalists such that it involves wrongful advantage taking of the former by the latter? Socialists have provided at least four answers to this question. (For critical surveys see Arnsperger and Van Parijs 2003: ch. III; Vrousalis 2018; Wolff 1999).

The first answer is offered by the unequal exchange account , according to which A exploits B if and only if in their exchange A gets more than B does. This account effectively collapses the normative sense of exploitation into the technical one. But critics have argued that this account fails to provide sufficient conditions for exploitation in the normative sense. Not every unequal exchange is wrongful: it would not be wrong to transfer resources from workers to people who (perhaps through no choice or fault of their own) are unable to work.

A second proposal is to say that A exploits B if and only if A gets surplus labor from B in a way that is coerced or forced. This labor entitlement account (Holmstrom 1977; Reiman 1987) relies on the view that workers are entitled to the product of their labor, and that capitalists wrongly deprive them of it. In a capitalist economy, workers are compelled to transfer surplus labor to capitalists on pain of severe poverty. This is a result of the coercively enforced system of private property rights in the means of production. Since they do not control means of production to secure their own subsistence, workers have no reasonable alternative to selling their labor power to capitalists and to toil on the terms favored by the latter. Critics of this approach have argued that it, like the previous account, fails to provide sufficient conditions for wrongful exploitation because it would (counterintuitively) have to condemn transfers from workers to destitute people unable to work. Furthermore, it has been argued that the account fails to provide necessary conditions for the occurrence of exploitation. Problematic transfers of surplus labor can occur without coercion. For example, A may have sophisticated means of production, not obtained from others through coercion, and hire B to work on them at a perhaps unfairly low wage, which B voluntarily accepts despite having acceptable, although less advantageous, alternatives (Roemer 1994b: ch. 4).

The third, unfair distribution of productive endowments account suggests that the core problem with capitalist exploitation (and with other forms of exploitation in class-divided social systems) is that it proceeds against a background distribution of initial access to productive assets that is inegalitarian. A is an exploiter, and B is exploited, if and only if A gains from B ’s labor and A would be worse off, and B better off, in an alternative hypothetical economic environment in which the initial distribution of assets was equal (with everything else remaining constant) (Roemer 1994b: 110). This account relies on a luck-egalitarian principle of equality of opportunity. (According to luck-egalitarianism, no one should be made worse-off than others due to circumstances beyond their control.) Critics have argued that, because of that, it fails to provide necessary conditions for wrongful exploitation. If A finds B stuck in a pit, it would be wrong for A to offer B rescue only if B signs a sweatshop contract with A —even if B happened to have fallen into the pit after voluntarily taking the risk to go hiking in an area well known to be dotted with such perilous obstacles (Vrousalis 2013, 2018). Other critics worry that this account neglects the centrality of relations of power or dominance between exploiters and exploited (Veneziani 2013).

A fourth approach directly focuses on the fact that exploitation typically arises when there is a significant power asymmetry between the parties involved. The more powerful instrumentalize and take advantage of the vulnerability of the less powerful to benefit from this asymmetry in positions (Goodin 1987). A specific version of this view, the domination for self-enrichment account (Vrousalis 2013, 2018), says that A exploits B if A benefits from a transaction in which A dominates B . (On this account, domination involves a disrespectful use of A ’s power over B .) Capitalist property rights, with the resulting unequal access to the means of production, put propertyless workers at the mercy of capitalists, who use their superior power over them to extract surplus labor. A worry about this approach is that it does not explain when the more powerful party is taking too much from the less powerful party. For example, take a situation where A and B start with equal assets, but A chooses to work hard while B chooses to spend more time at leisure, so that at a later time A controls the means of production, while B has only their own labor power. We imagine that A offers B employment, and then ask, in light of their ex ante equal position, at what level of wage for B and profit for A would the transaction involve wrongful exploitation? To come to a settled view on this question, it might be necessary to combine reliance on a principle of freedom as non-domination with appeal to additional socialist principles addressing just distribution—such as some version of the principles of equality and solidarity mentioned above in section 4.1 .

Capitalism is often defended by saying that it maximally extends people’s freedom, understood as the absence of interference. Socialism would allegedly depress that freedom by prohibiting or limiting capitalist activities such as setting up a private firm, hiring wage workers, and keeping, investing, or spending profits. Socialists generally acknowledge that a socialist economy would severely constrain some such freedoms. But they point out that capitalist property rights also involve interference. They remind us that “private property by one person presupposes non-ownership on the part of other persons” (Marx 1991: 812) and warn that often, although

liberals and libertarians see the freedom which is intrinsic to capitalism, they overlook the unfreedom which necessarily accompanies capitalist freedom. (G.A. Cohen 2011: 150)

Workers could and would be coercively interfered with if they tried to use means of production possessed by capitalists, to walk away with the products of their labor in capitalist firms, or to access consumption goods they do not have enough money to buy. In fact, every economic system opens some zones of non-interference while closing others. Hence the appropriate question is not whether capitalism or socialism involve interference—they both do—but whether either of them involves more net interference, or more troubling forms of interference, than the other. And the answer to that question is far from obvious. It could very well be that most agents in a socialist society face less (troublesome) interference as they pursue their projects of production and consumption than agents in a capitalist society (G.A. Cohen 2011: chs. 7–8).

Capitalist economic relations are often defended by saying that they are the result of free choices by consenting adults. Wage workers are not slaves or serfs—they have the legal right to refuse to work for capitalists. But socialists reply that the relationship between capitalists and workers actually involves domination. Workers are inappropriately subject to the will of capitalists in the shaping of the terms on which they work (both in the spheres of exchange and production, and within the broader political process). Workers’ consent to their exploitation is given in circumstances of deep vulnerability and asymmetry of power. According to Marx, two conditions help explain workers’ apparently free choice to enter into a nevertheless exploitative contract: (1) in capitalism (unlike in feudalism or slave societies) workers own their labor power, but (2) they do not own means of production. Because of their deprivation (2), workers have no reasonable alternative to using their entitlement (1) to sell their labor power to the capitalists—who do own the means of production (Marx 1867 [1990: 272–3]). Through labor-saving technical innovations spurred by competition, capitalism also constantly produces unemployment, which weakens the bargaining power of individual workers further. Thus, Marx says that although workers voluntarily enter into exploitative contracts, they are “compelled [to do so] by social conditions”.

The silent compulsion of economic relations sets the seal on the domination of the capitalist over the worker…. [The worker’s] dependence on capital … springs from the conditions of production themselves, and is guaranteed in perpetuity by them. (Marx 1867 [1990: 382, 899])

Because of the deep background inequality of power resulting from their structural position within a capitalist economy, workers accept a pattern of economic transaction in which they submit to the direction of capitalists during the activities of production, and surrender to those same capitalists a disproportional share of the fruits of their labor. Although some individual workers might be able to escape their vulnerable condition by saving and starting a firm of their own, most would find this extremely difficult, and they could not all do it simultaneously within capitalism (Elster 1985: 208–16; G.A. Cohen 1988: ch. 13).

Socialists sometimes say that capitalism flouts an ideal of non-domination as freedom from being subject to rules one has systematically less power to shape than others (Gourevitch 2013; Arnold 2017; Gilabert 2017b: 566–7—on which this and the previous paragraph draw). Capitalist relations of production involve domination and the dependence of workers on the discretion of capitalists’ choices at three critical junctures. The first, mentioned above, concerns the labor contract. Due to their lack of control of the means of production, workers must largely submit, on pain of starvation or severe poverty, to the terms capitalists offer them. The second concerns interactions in the workplace. Capitalists and their managers rule the activities of workers by unilaterally deciding what and how the latter produce. Although in the sphere of circulation workers and capitalists might look (misleadingly, given the first point) like equally free contractors striking fair deals, once we enter the “hidden abode” of production it is clear to all sides that what exists is relationships of intense subjection of some to the will of others (Marx 1867 [1990: 279–80]). Workers effectively spend many of their waking hours doing what others dictate them to do. Third, and finally, capitalists have a disproportionate impact on the legal and political process shaping the institutional structure of the society in which they exploit workers, with capitalist interests dominating the political processes which in turn set the contours of property and labor law. Even if workers manage to obtain the legal right to vote and create their own trade unions and parties (which labor movements achieved in some countries after much struggle), capitalists exert disproportionate influence via greater access to mass media, the funding of political parties, the threat of disinvestment and capital flight if governments reduce their profit margin, and the past and prospective recruitment of state officials in lucrative jobs in their firms and lobbying agencies (Wright 2010: 81–4). At the spheres of exchange, production, and in the broader political process, workers and capitalist have asymmetric structural power. Consequently, the former are significantly subject to the will of the latter in the shaping of the terms on which they work (see further Wright 2000 [2015]). This inequality of structural power, some socialists claim, is an affront to workers’ dignity as self-determining, self-mastering agents.

The third point about domination mentioned above is also deployed by socialists to say that capitalism conflicts with democracy (Wright 2010: 81–4; Arnold n.d. [OIR] : sect. 4; Bowles and Gintis 1986; Meiksins Wood 1995). Democracy requires that people have roughly equal power to affect the political process that structures their social life—or at least that inequalities do not reflect morally irrelevant features such as race, gender, and class. Socialists have made three points regarding the conflict between capitalism and democracy. The first concerns political democracy of the kind that is familiar today. Even in the presence of multi-party electoral systems, members of the capitalist class—despite being a minority of the population—have significantly more influence than members of the working class. Governments have a tendency to adapt their agendas to the wishes of capitalists because they depend on their investment decisions to raise the taxes to fund public policies, as well as for the variety of other reasons outlined above. Even if socialist parties win elections, as long as they do not change the fundamentals of the economic system, they must be congenial to the wishes of capitalists. Thus, socialists have argued that deep changes in the economic structure of society are needed to make electoral democracy fulfill its promise. Political power cannot be insulated from economic power. They also, secondly, think that such changes may be directly significant. Indeed, as radical democrats, socialists have argued that reducing inequality of decision-making power within the economic sphere itself is not only instrumentally significant (to reduce inequality within the governmental sphere), but also intrinsically significant to increase people’s self-determination in their daily lives as economic agents. Therefore, most democratic socialists call for a solution to the problem of the conflict between democracy and capitalism by extending democratic principles into the economy (Fleurbaey 2006). Exploring the parallel between the political and economic systems, socialists have argued that democratic principles should apply in the economic arena as they do in the political domain, as economic decisions, like political decisions, have dramatic consequences for the freedom and well-being of people. Returning to the issue of the relations between the two arenas, socialists have also argued that fostering workers’ self-determination in the economy (notably in the workplace) enhances democratic participation at the political level (Coutrot 2018: ch. 9; Arnold 2012; see survey on workplace democracy in Frega et al. 2019). A third strand of argument, finally, has explored the importance of socialist reforms for fulfilling the ideal of a deliberative democracy in which people participate as free and equal reasoners seeking to make decisions that actually cater for the common good of all (J. Cohen 1989).

As mentioned above, socialists have included, in their affirmation of individual freedom, a specific concern with real or effective freedom to lead flourishing lives. This freedom is often linked with a positive ideal of self-realization , which in turn motivates a critique of capitalism as generating alienation. This perspective informs Marx’s views on the strong contrast between productive activity under socialism and under capitalism. In socialism, the “realm of necessity” and the correspondingly necessary, but typically unsavory, labor required to secure basic subsistence would be reduced so that people also access a “realm of freedom” in which a desirable form of work involving creativity, cultivation of talents, and meaningful cooperation with others is available. This realm of freedom would unleash “the development of human energy which is an end in itself” (Marx 1991: 957–9). This work, allowing for and facilitating individuals’ self-realization, would enable the “all-round development of the individual”, and would in fact become a “prime want” (Marx 1875 [1978b: 531]). The socialist society would feature “the development of the rich individuality which is all-sided in its production as in its consumption” (Marx 1857–8 [1973: 325]); it would constitute a “higher form of society in which the full and free development of every individual forms the ruling principle” (Marx 1867 [1990: 739]). By contrast, capitalism denies the majority of the population access to self-realization at work. Workers typically toil in tasks which are uninteresting and even stunting. They do not control how production unfolds or what is done with the outputs of production. And their relations with others is not one of fellowship, but rather of domination (under their bosses) and of competition (against their fellow workers). When alienated,

labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his essential being; … in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. … It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. (Marx 1844 [1978a: 74])

Recent scholarship has developed these ideas further. Elster has provided the most detailed discussion and development of the Marxian ideal of self-realization. The idea is defined as “the full and free actualization and externalization of the powers and the abilities of the individual” (Elster 1986: 43; 1989: 131). Self-actualization involves a two-step process in which individuals develop their powers (e.g., learn the principles and techniques of civil engineering) and then actualize those powers (e.g., design and participate in the construction of a bridge). Self-externalization, in turn, features a process in which individuals’ powers become visible to others with the potential beneficial outcome of social recognition and the accompanying boost in self-respect and self-esteem. However, Elster says that this Marxian ideal must be reformulated to make it more realistic. No one can develop all their powers fully, and no feasible economy would enable everyone always to get exactly their first-choice jobs and conduct them only in the ways they would most like. Furthermore, self-realization for and with others (and thus also the combination of self-realization with community) may not always work smoothly, as producers entangled in large and complex societies may not feel strongly moved by the needs of distant others, and significant forms of division of labor will likely persist. Still, Elster thinks the socialist ideal of self-realization remains worth pursuing, for example through the generation of opportunities to produce in worker cooperatives. Others have construed the demand for real options to produce in ways that involve self-realization and solidarity as significant for the implementation of the Abilities / Needs Principle (Gilabert 2015: 207–12), and defended a right to opportunities for meaningful work against the charge that it violates a liberal constraint of neutrality about conceptions of the good (Gilabert 2018b: sect. 3.3). (For more discussion on alienation and self-realization, see Jaeggi 2014: ch. 10.)

Further scholarship explores recent changes in the organization of production. Boltanski and Chiapello argue that since the 1980s capitalism has partly absorbed (what they dub) the “artistic critique” against de-skilled and heteronomous work by generating schemes of economic activity in which workers operate in teams and have significant decision-making powers. However, these new forms of work, although common especially in certain knowledge-intensive sectors, are not available to all workers, and they still operate under the ultimate control of capital owners and their profit maximizing strategies. They also operate in tandem with the elimination of the social security policies typical of the (increasingly eroded) welfare state. Thus, the “artistic” strand in the socialist critique of capitalism as hampering people’s authenticity, creativity, and autonomy has not been fully absorbed and should be renewed. It should also be combined with the other, “social critique” strand which challenges inequality, insecurity, and selfishness (Boltanski and Chiapello 2018: Introduction, sect. 2). Other authors find in these new forms of work the seeds of future forms of economic organization—arguing that they provide evidence that workers can plan and control sophisticated processes of production on their own and that capitalists and their managers are largely redundant (Negri 2008).

The critique of alienation has also been recently developed further by Forst (2017) by exploring the relation between alienation and domination. On this account, the central problem with alienation is that it involves the denial of people’s autonomy—their ability and right to shape their social life on terms they could justify to themselves and to each other as free and equal co-legislators. (See also the general analysis of the concept of alienation in Leopold 2018.)

A traditional criticism of capitalism (especially amongst Marxists) is that it is inefficient. Capitalism is prone to cyclic crises in which wealth and human potential is destroyed and squandered. For example, to cut costs and maximize profits, firms choose work-saving technologies and lay off workers. But at the aggregate level, this erodes the demand for their products, which forces firms to cut costs further (by laying off even more workers or halting production). Socialism would, it has been argued, not be so prone to crises, as the rationale for production would not be profit maximization but need satisfaction. Although important, this line of criticism is less widespread amongst contemporary socialists. Historically, capitalism has proved quite resilient, resurrecting itself after crises and expanding its productivity dramatically over time. In might very well be that capitalism is the best feasible regime if the only standard of assessment were productivity.

Still, socialists point out that capitalism involves some significant inefficiencies. Examples are the underproduction of public goods (such as public transportation and education), the underpricing and overconsumption of natural resources (such as fossil fuels and fishing stocks), negative externalities (such as pollution), the costs of monitoring and enforcing market contracts and private property (given that the exploited may not be so keen to work as hard as their profit-maximizing bosses require, and that the marginalized may be moved by desperation to steal), and certain defects of intellectual property rights (such as blocking the diffusion of innovation, and alienating those who engage in creative activities because of their intrinsic appeal and because of the will to serve the public rather than maximize monetary reward) (Wright 2010: 55–65). Really existing capitalist societies have introduced regulations to counter some of these problems, at least to some extent. Examples are taxes and constraints to limit economic activities with negative externalities, and public funding and subsidies to sustain activities with positive externalities which are not sufficiently supported by the market. But, socialists insist, such mechanisms are external to capitalism, as they limit property rights and the scope for profit maximization as the primary orientation in the organization of the economy. The regulations involve the hybridization of the economic system by introducing some non-capitalist, and even socialist elements.

There is also an important issue of whether efficiency should only be understood in terms of maximizing production of material consumption goods. If the metric, or the utility space, that is taken into account when engaging in maximization assessments includes more than these goods, then capitalism can also be criticized as inefficient on account of its tendency to depress the availability of leisure time (as well as to distribute it quite unequally). This carries limitation of people’s access to the various goods that leisure enables—such as the cultivation of friendships, family, and community or political participation. Technological innovations create the opportunity to choose between retaining the previous level of production while using fewer inputs (such as labor time) or maintaining the level of inputs while producing more. John Maynard Keynes famously held that it would be reasonable to tend towards the prior option, and expected societies to take this path as the technological frontier advanced (Keynes 1930/31 [2010]; Pecchi and Piga 2010). Nevertheless, in large part because of the profit maximization motive, capitalism displays an inherent bias in favor of the second, arguably inferior, option. Capitalism thereby narrows the realistic options of its constituent economic agents—both firms and individuals. Firms would lose their competitive edge and risk bankruptcy if they did not pursue profits ahead of the broader interests of their workers (as their products would likely be more expensive). And it is typically hard for workers to find jobs that pay reasonable salaries for fewer hours of work. Socialists concerned with expanding leisure time—and also with environmental risks—find this bias quite alarming (see, e.g., G.A. Cohen 2000a: ch. XI). If a conflict between further increase in the production of material objects for consumption and the expansion of leisure time (and environmental protection) is unavoidable, then it is not clear, all things considered, that the former should be prioritized, especially when an economy has already reached a high level of material productivity.

Capitalism has also been challenged on liberal egalitarian grounds, and in ways that lend themselves to support for socialism. (Rawls 2001; Barry 2005; Piketty 2014; O’Neill 2008a, 2012, 2017; Ronzoni 2018). While many of John Rawls’s readers long took him to be a proponent of an egalitarian form of a capitalist welfare state, or as one might put it “a slightly imaginary Sweden”, in fact Rawls rejected such institutional arrangements as inadequate to the task of realizing principles of political liberty or equality of opportunity, or of keeping material inequalities within sufficiently tight bounds. His own avowed view of the institutions that would be needed to realize liberal egalitarian principles of justice was officially neutral as between a form of “property-owning democracy”, which would combine private property in the means of production with its egalitarian distribution, and hence the abolition of the separate classes of capitalists and workers; and a form of liberal democratic socialism that would see public ownership of the preponderance of the means of production, with devolved control of particular firms (Rawls 2001: 135–40; O’Neill and Williamson 2012). While Rawls’s version of liberal democratic socialism was insufficiently developed in his own writings, he stands as an interesting case of a theorist whose defense of a form of democratic socialism is based on normative foundations that are not themselves distinctively socialist, but concerned with the core liberal democratic values of justice and equality (see also Edmundson 2017; Ypi 2018).

In a similar vein to Rawls, another instance of a theorist who defends at least partially socialist institutional arrangements on liberal egalitarian grounds was the Nobel Prize winning economist James Meade. Giving a central place to decidedly liberal values of freedom, security and independence, Meade argued that the likely levels of socioeconomic inequality under capitalism were such that a capitalist economy would need to be extensively tempered by socialist elements, such as the development of a citizens’ sovereign wealth fund, if the economic system were to be justifiable to those living under it (Meade 1964; O’Neill 2015 [OIR] , 2017; O’Neill and White 2019). Looking back before Meade, J. S. Mill can also be seen as a theorist who traveled along what we might describe as “the liberal road to socialism”, with Mill in his Autobiography describing his own view as the acceptance of a “qualified socialism” (Mill 1873 [2018]), and arguing for a range of measures to create a more egalitarian economy, including making the case for a steady-state rather than a growth-oriented economy, arguing for workers’ collective ownership and self-management of firms in preference to the hierarchical structures characteristic of most firms under capitalism, and endorsing steep taxation of inheritance and unearned income (Mill 2008; see also Ten 1998; O’Neill 2008b, Pateman 1970). More recently, the argument has been advanced that as capitalist economies tend towards higher levels of inequality, and in particular with the rapid velocity at which the incomes and wealth of the very rich in society is increasing, many of those who had seen their normative commitments as requiring only the mild reform of capitalist economies might need to come to see the need to endorse more radical socialist institutional proposals (Ronzoni 2018).

4. Socialist Institutional Designs (Dimension DII)

The foregoing discussion focused on socialist critiques of capitalism. These critiques make the case that capitalism fails to fulfill principles, or to realize values, to which socialists are committed. But what would an alternative economic system look like which would fulfill those principles, or realize those values—or at least honor them to a larger extent? This brings us to dimension DII of socialism. We will consider several proposed models. We will address here critical concerns about both the feasibility and the desirability of these models. Arguments comparing ideal socialist designs with actual capitalist societies are unsatisfactory; we must compare like with like (Nove 1991; Brennan 2014; Corneo 2017). Thus, we should compare ideal forms of socialism with ideal forms of capitalism, and actual versions of capitalism with actual versions of socialism. Most importantly, we should entertain comparisons between the best feasible incarnations of these systems. This requires formulating feasible forms of socialism. Feasibility assessments can play out in two ways: they may regard the (degree of) workability and stability of a proposed socialist system once introduced, or they may regard its (degree of) accessibility from current conditions when it is not yet in place. We address the former concerns in this section, leaving the latter for section 5 when we turn to dimension DIII of socialism and the questions of socialist transition or transformation.

Would socialism do better than capitalism regarding the ideals of equality, democracy, individual freedom, self-realization, and solidarity? This depends on the availability of workable versions of socialism that fulfill these ideals (or do so at least to a greater extent than workable forms of capitalism). A first set of proposals envision an economic system that does away with both private property in the means of production and with markets. The first version of this model is central planning . This can be understood within a top-down, hierarchical model. A central authority gathers information about the technical potential in the economy and about consumers’ needs and formulates a set of production objectives which seek an optimal match between the former and the latter. These objectives are articulated into a plan that is passed down to intermediate agencies and eventually to local firms, which must produce according to the plan handed down. If it works, this proposal would secure the highest feasible levels of equal access to consumption goods for everyone. However, critics have argued that the model faces serious feasibility hurdles (Corneo 2017: ch. 5: Roemer 1994a: ch. 5). It is very hard for a central authority to gather the relevant information from producers and consumers. Second, even if it could gather enough information, the computation of an optimal plan would require enormously complex calculations which may be beyond the capacity of planners (even with access to the most sophisticated technological assistance). Finally, there may be significant incentive deficits. For example, firms might tend to exaggerate the resources they need to produce and mislead about how much they can produce. Without facing strong sticks and carrots (such as the prospects for either bankruptcy and profit offered by a competitive market), firms might well display low levels of innovation. As a result, a planned economy would likely lag behind surrounding capitalist economies, and their members would tend to lose faith in it. High levels of cooperation (and willingness to innovate) could still exist if sufficiently many individuals in this society possessed a strong sense of duty. But critics find this unlikely to materialize, warning that “a system that only works with exceptional individuals only works in exceptional cases” (Corneo 2017: 127).