The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

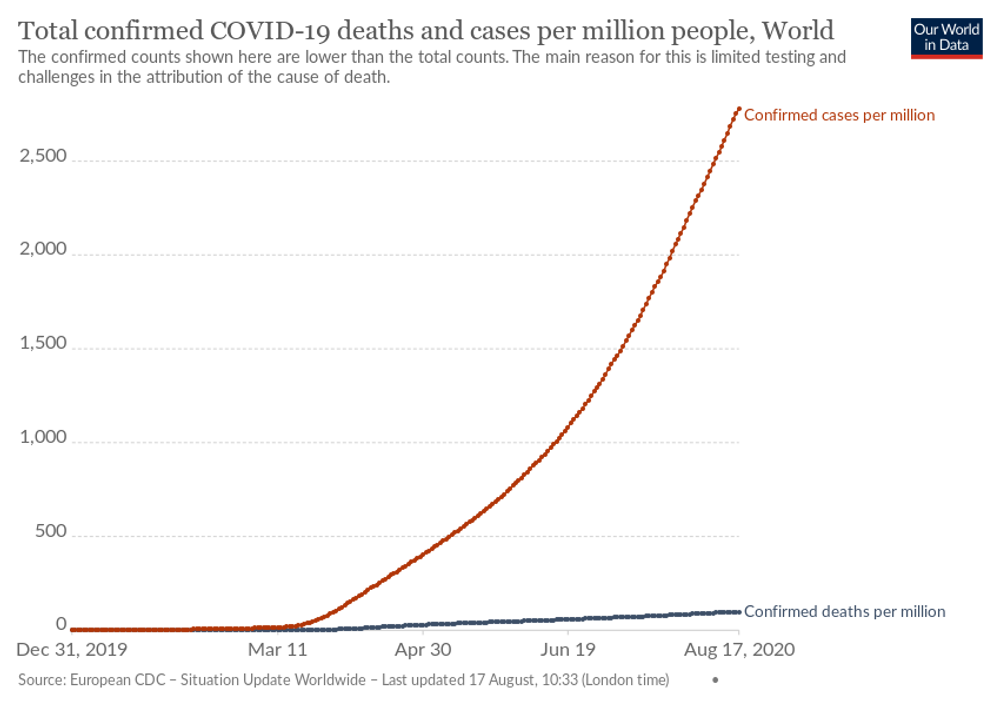

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

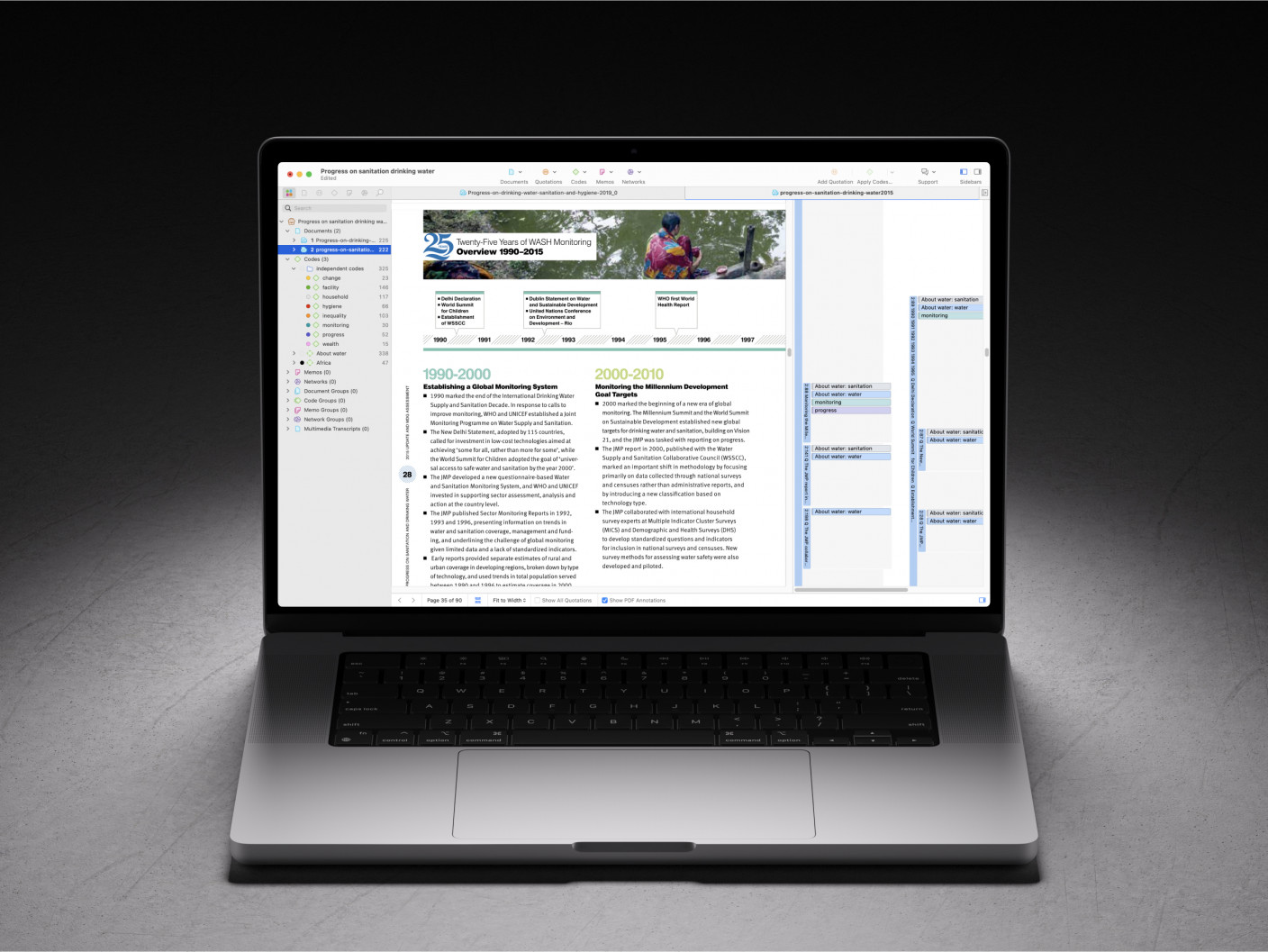

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

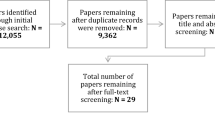

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Designing and Conducting Case Studies

This guide examines case studies, a form of qualitative descriptive research that is used to look at individuals, a small group of participants, or a group as a whole. Researchers collect data about participants using participant and direct observations, interviews, protocols, tests, examinations of records, and collections of writing samples. Starting with a definition of the case study, the guide moves to a brief history of this research method. Using several well documented case studies, the guide then looks at applications and methods including data collection and analysis. A discussion of ways to handle validity, reliability, and generalizability follows, with special attention to case studies as they are applied to composition studies. Finally, this guide examines the strengths and weaknesses of case studies.

Definition and Overview

Case study refers to the collection and presentation of detailed information about a particular participant or small group, frequently including the accounts of subjects themselves. A form of qualitative descriptive research, the case study looks intensely at an individual or small participant pool, drawing conclusions only about that participant or group and only in that specific context. Researchers do not focus on the discovery of a universal, generalizable truth, nor do they typically look for cause-effect relationships; instead, emphasis is placed on exploration and description.

Case studies typically examine the interplay of all variables in order to provide as complete an understanding of an event or situation as possible. This type of comprehensive understanding is arrived at through a process known as thick description, which involves an in-depth description of the entity being evaluated, the circumstances under which it is used, the characteristics of the people involved in it, and the nature of the community in which it is located. Thick description also involves interpreting the meaning of demographic and descriptive data such as cultural norms and mores, community values, ingrained attitudes, and motives.

Unlike quantitative methods of research, like the survey, which focus on the questions of who, what, where, how much, and how many, and archival analysis, which often situates the participant in some form of historical context, case studies are the preferred strategy when how or why questions are asked. Likewise, they are the preferred method when the researcher has little control over the events, and when there is a contemporary focus within a real life context. In addition, unlike more specifically directed experiments, case studies require a problem that seeks a holistic understanding of the event or situation in question using inductive logic--reasoning from specific to more general terms.

In scholarly circles, case studies are frequently discussed within the context of qualitative research and naturalistic inquiry. Case studies are often referred to interchangeably with ethnography, field study, and participant observation. The underlying philosophical assumptions in the case are similar to these types of qualitative research because each takes place in a natural setting (such as a classroom, neighborhood, or private home), and strives for a more holistic interpretation of the event or situation under study.

Unlike more statistically-based studies which search for quantifiable data, the goal of a case study is to offer new variables and questions for further research. F.H. Giddings, a sociologist in the early part of the century, compares statistical methods to the case study on the basis that the former are concerned with the distribution of a particular trait, or a small number of traits, in a population, whereas the case study is concerned with the whole variety of traits to be found in a particular instance" (Hammersley 95).

Case studies are not a new form of research; naturalistic inquiry was the primary research tool until the development of the scientific method. The fields of sociology and anthropology are credited with the primary shaping of the concept as we know it today. However, case study research has drawn from a number of other areas as well: the clinical methods of doctors; the casework technique being developed by social workers; the methods of historians and anthropologists, plus the qualitative descriptions provided by quantitative researchers like LePlay; and, in the case of Robert Park, the techniques of newspaper reporters and novelists.

Park was an ex-newspaper reporter and editor who became very influential in developing sociological case studies at the University of Chicago in the 1920s. As a newspaper professional he coined the term "scientific" or "depth" reporting: the description of local events in a way that pointed to major social trends. Park viewed the sociologist as "merely a more accurate, responsible, and scientific reporter." Park stressed the variety and value of human experience. He believed that sociology sought to arrive at natural, but fluid, laws and generalizations in regard to human nature and society. These laws weren't static laws of the kind sought by many positivists and natural law theorists, but rather, they were laws of becoming--with a constant possibility of change. Park encouraged students to get out of the library, to quit looking at papers and books, and to view the constant experiment of human experience. He writes, "Go and sit in the lounges of the luxury hotels and on the doorsteps of the flophouses; sit on the Gold Coast settees and on the slum shakedowns; sit in the Orchestra Hall and in the Star and Garter Burlesque. In short, gentlemen [sic], go get the seats of your pants dirty in real research."

But over the years, case studies have drawn their share of criticism. In fact, the method had its detractors from the start. In the 1920s, the debate between pro-qualitative and pro-quantitative became quite heated. Case studies, when compared to statistics, were considered by many to be unscientific. From the 1930's on, the rise of positivism had a growing influence on quantitative methods in sociology. People wanted static, generalizable laws in science. The sociological positivists were looking for stable laws of social phenomena. They criticized case study research because it failed to provide evidence of inter subjective agreement. Also, they condemned it because of the few number of cases studied and that the under-standardized character of their descriptions made generalization impossible. By the 1950s, quantitative methods, in the form of survey research, had become the dominant sociological approach and case study had become a minority practice.

Educational Applications

The 1950's marked the dawning of a new era in case study research, namely that of the utilization of the case study as a teaching method. "Instituted at Harvard Business School in the 1950s as a primary method of teaching, cases have since been used in classrooms and lecture halls alike, either as part of a course of study or as the main focus of the course to which other teaching material is added" (Armisted 1984). The basic purpose of instituting the case method as a teaching strategy was "to transfer much of the responsibility for learning from the teacher on to the student, whose role, as a result, shifts away from passive absorption toward active construction" (Boehrer 1990). Through careful examination and discussion of various cases, "students learn to identify actual problems, to recognize key players and their agendas, and to become aware of those aspects of the situation that contribute to the problem" (Merseth 1991). In addition, students are encouraged to "generate their own analysis of the problems under consideration, to develop their own solutions, and to practically apply their own knowledge of theory to these problems" (Boyce 1993). Along the way, students also develop "the power to analyze and to master a tangled circumstance by identifying and delineating important factors; the ability to utilize ideas, to test them against facts, and to throw them into fresh combinations" (Merseth 1991).

In addition to the practical application and testing of scholarly knowledge, case discussions can also help students prepare for real-world problems, situations and crises by providing an approximation of various professional environments (i.e. classroom, board room, courtroom, or hospital). Thus, through the examination of specific cases, students are given the opportunity to work out their own professional issues through the trials, tribulations, experiences, and research findings of others. An obvious advantage to this mode of instruction is that it allows students the exposure to settings and contexts that they might not otherwise experience. For example, a student interested in studying the effects of poverty on minority secondary student's grade point averages and S.A.T. scores could access and analyze information from schools as geographically diverse as Los Angeles, New York City, Miami, and New Mexico without ever having to leave the classroom.

The case study method also incorporates the idea that students can learn from one another "by engaging with each other and with each other's ideas, by asserting something and then having it questioned, challenged and thrown back at them so that they can reflect on what they hear, and then refine what they say" (Boehrer 1990). In summary, students can direct their own learning by formulating questions and taking responsibility for the study.

Types and Design Concerns

Researchers use multiple methods and approaches to conduct case studies.

Types of Case Studies

Under the more generalized category of case study exist several subdivisions, each of which is custom selected for use depending upon the goals and/or objectives of the investigator. These types of case study include the following:

Illustrative Case Studies These are primarily descriptive studies. They typically utilize one or two instances of an event to show what a situation is like. Illustrative case studies serve primarily to make the unfamiliar familiar and to give readers a common language about the topic in question.

Exploratory (or pilot) Case Studies These are condensed case studies performed before implementing a large scale investigation. Their basic function is to help identify questions and select types of measurement prior to the main investigation. The primary pitfall of this type of study is that initial findings may seem convincing enough to be released prematurely as conclusions.

Cumulative Case Studies These serve to aggregate information from several sites collected at different times. The idea behind these studies is the collection of past studies will allow for greater generalization without additional cost or time being expended on new, possibly repetitive studies.

Critical Instance Case Studies These examine one or more sites for either the purpose of examining a situation of unique interest with little to no interest in generalizability, or to call into question or challenge a highly generalized or universal assertion. This method is useful for answering cause and effect questions.

Identifying a Theoretical Perspective

Much of the case study's design is inherently determined for researchers, depending on the field from which they are working. In composition studies, researchers are typically working from a qualitative, descriptive standpoint. In contrast, physicists will approach their research from a more quantitative perspective. Still, in designing the study, researchers need to make explicit the questions to be explored and the theoretical perspective from which they will approach the case. The three most commonly adopted theories are listed below:

Individual Theories These focus primarily on the individual development, cognitive behavior, personality, learning and disability, and interpersonal interactions of a particular subject.

Organizational Theories These focus on bureaucracies, institutions, organizational structure and functions, or excellence in organizational performance.

Social Theories These focus on urban development, group behavior, cultural institutions, or marketplace functions.

Two examples of case studies are used consistently throughout this chapter. The first, a study produced by Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988), looks at a first year graduate student's initiation into an academic writing program. The study uses participant-observer and linguistic data collecting techniques to assess the student's knowledge of appropriate discourse conventions. Using the pseudonym Nate to refer to the subject, the study sought to illuminate the particular experience rather than to generalize about the experience of fledgling academic writers collectively.

For example, in Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman's (1988) study we are told that the researchers are interested in disciplinary communities. In the first paragraph, they ask what constitutes membership in a disciplinary community and how achieving membership might affect a writer's understanding and production of texts. In the third paragraph they state that researchers must negotiate their claims "within the context of his sub specialty's accepted knowledge and methodology." In the next paragraph they ask, "How is literacy acquired? What is the process through which novices gain community membership? And what factors either aid or hinder students learning the requisite linguistic behaviors?" This introductory section ends with a paragraph in which the study's authors claim that during the course of the study, the subject, Nate, successfully makes the transition from "skilled novice" to become an initiated member of the academic discourse community and that his texts exhibit linguistic changes which indicate this transition. In the next section the authors make explicit the sociolinguistic theoretical and methodological assumptions on which the study is based (1988). Thus the reader has a good understanding of the authors' theoretical background and purpose in conducting the study even before it is explicitly stated on the fourth page of the study. "Our purpose was to examine the effects of the educational context on one graduate student's production of texts as he wrote in different courses and for different faculty members over the academic year 1984-85." The goal of the study then, was to explore the idea that writers must be initiated into a writing community, and that this initiation will change the way one writes.

The second example is Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of a group of twelfth graders. In this study, Emig seeks to answer the question of what happens to the self as a result educational stimuli in terms of academic writing. The case study used methods such as protocol analysis, tape-recorded interviews, and discourse analysis.

In the case of Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of eight twelfth graders, four specific hypotheses were made:

- Twelfth grade writers engage in two modes of composing: reflexive and extensive.

- These differences can be ascertained and characterized through having the writers compose aloud their composition process.

- A set of implied stylistic principles governs the writing process.

- For twelfth grade writers, extensive writing occurs chiefly as a school-sponsored activity, or reflexive, as a self-sponsored activity.

In this study, the chief distinction is between the two dominant modes of composing among older, secondary school students. The distinctions are:

- The reflexive mode, which focuses on the writer's thoughts and feelings.

- The extensive mode, which focuses on conveying a message.

Emig also outlines the specific questions which guided the research in the opening pages of her Review of Literature , preceding the report.

Designing a Case Study

After considering the different sub categories of case study and identifying a theoretical perspective, researchers can begin to design their study. Research design is the string of logic that ultimately links the data to be collected and the conclusions to be drawn to the initial questions of the study. Typically, research designs deal with at least four problems:

- What questions to study

- What data are relevant

- What data to collect

- How to analyze that data

In other words, a research design is basically a blueprint for getting from the beginning to the end of a study. The beginning is an initial set of questions to be answered, and the end is some set of conclusions about those questions.

Because case studies are conducted on topics as diverse as Anglo-Saxon Literature (Thrane 1986) and AIDS prevention (Van Vugt 1994), it is virtually impossible to outline any strict or universal method or design for conducting the case study. However, Robert K. Yin (1993) does offer five basic components of a research design:

- A study's questions.

- A study's propositions (if any).

- A study's units of analysis.

- The logic that links the data to the propositions.

- The criteria for interpreting the findings.

In addition to these five basic components, Yin also stresses the importance of clearly articulating one's theoretical perspective, determining the goals of the study, selecting one's subject(s), selecting the appropriate method(s) of collecting data, and providing some considerations to the composition of the final report.

Conducting Case Studies

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of approaches and methods. These approaches, methods, and related issues are discussed in depth in this section.

Method: Single or Multi-modal?

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of methods. Some common methods include interviews , protocol analyses, field studies, and participant-observations. Emig (1971) chose to use several methods of data collection. Her sources included conversations with the students, protocol analysis, discrete observations of actual composition, writing samples from each student, and school records (Lauer and Asher 1988).

Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) collected data by observing classrooms, conducting faculty and student interviews, collecting self reports from the subject, and by looking at the subject's written work.

A study that was criticized for using a single method model was done by Flower and Hayes (1984). In this study that explores the ways in which writers use different forms of knowing to create space, the authors used only protocol analysis to gather data. The study came under heavy fire because of their decision to use only one method.

Participant Selection

Case studies can use one participant, or a small group of participants. However, it is important that the participant pool remain relatively small. The participants can represent a diverse cross section of society, but this isn't necessary.

For example, the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study looked at just one participant, Nate. By contrast, in Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composition process of twelfth graders, eight participants were selected representing a diverse cross section of the community, with volunteers from an all-white upper-middle-class suburban school, an all-black inner-city school, a racially mixed lower-middle-class school, an economically and racially mixed school, and a university school.

Often, a brief "case history" is done on the participants of the study in order to provide researchers with a clearer understanding of their participants, as well as some insight as to how their own personal histories might affect the outcome of the study. For instance, in Emig's study, the investigator had access to the school records of five of the participants, and to standardized test scores for the remaining three. Also made available to the researcher was the information that three of the eight students were selected as NCTE Achievement Award winners. These personal histories can be useful in later stages of the study when data are being analyzed and conclusions drawn.

Data Collection

There are six types of data collected in case studies:

- Archival records.

- Interviews.

- Direct observation.

- Participant observation.

In the field of composition research, these six sources might be:

- A writer's drafts.

- School records of student writers.

- Transcripts of interviews with a writer.

- Transcripts of conversations between writers (and protocols).

- Videotapes and notes from direct field observations.

- Hard copies of a writer's work on computer.

Depending on whether researchers have chosen to use a single or multi-modal approach for the case study, they may choose to collect data from one or any combination of these sources.

Protocols, that is, transcriptions of participants talking aloud about what they are doing as they do it, have been particularly common in composition case studies. For example, in Emig's (1971) study, the students were asked, in four different sessions, to give oral autobiographies of their writing experiences and to compose aloud three themes in the presence of a tape recorder and the investigator.

In some studies, only one method of data collection is conducted. For example, the Flower and Hayes (1981) report on the cognitive process theory of writing depends on protocol analysis alone. However, using multiple sources of evidence to increase the reliability and validity of the data can be advantageous.

Case studies are likely to be much more convincing and accurate if they are based on several different sources of information, following a corroborating mode. This conclusion is echoed among many composition researchers. For example, in her study of predrafting processes of high and low-apprehensive writers, Cynthia Selfe (1985) argues that because "methods of indirect observation provide only an incomplete reflection of the complex set of processes involved in composing, a combination of several such methods should be used to gather data in any one study." Thus, in this study, Selfe collected her data from protocols, observations of students role playing their writing processes, audio taped interviews with the students, and videotaped observations of the students in the process of composing.

It can be said then, that cross checking data from multiple sources can help provide a multidimensional profile of composing activities in a particular setting. Sharan Merriam (1985) suggests "checking, verifying, testing, probing, and confirming collected data as you go, arguing that this process will follow in a funnel-like design resulting in less data gathering in later phases of the study along with a congruent increase in analysis checking, verifying, and confirming."

It is important to note that in case studies, as in any qualitative descriptive research, while researchers begin their studies with one or several questions driving the inquiry (which influence the key factors the researcher will be looking for during data collection), a researcher may find new key factors emerging during data collection. These might be unexpected patterns or linguistic features which become evident only during the course of the research. While not bearing directly on the researcher's guiding questions, these variables may become the basis for new questions asked at the end of the report, thus linking to the possibility of further research.

Data Analysis

As the information is collected, researchers strive to make sense of their data. Generally, researchers interpret their data in one of two ways: holistically or through coding. Holistic analysis does not attempt to break the evidence into parts, but rather to draw conclusions based on the text as a whole. Flower and Hayes (1981), for example, make inferences from entire sections of their students' protocols, rather than searching through the transcripts to look for isolatable characteristics.

However, composition researchers commonly interpret their data by coding, that is by systematically searching data to identify and/or categorize specific observable actions or characteristics. These observable actions then become the key variables in the study. Sharan Merriam (1988) suggests seven analytic frameworks for the organization and presentation of data:

- The role of participants.

- The network analysis of formal and informal exchanges among groups.

- Historical.

- Thematical.

- Ritual and symbolism.

- Critical incidents that challenge or reinforce fundamental beliefs, practices, and values.

There are two purposes of these frameworks: to look for patterns among the data and to look for patterns that give meaning to the case study.

As stated above, while most researchers begin their case studies expecting to look for particular observable characteristics, it is not unusual for key variables to emerge during data collection. Typical variables coded in case studies of writers include pauses writers make in the production of a text, the use of specific linguistic units (such as nouns or verbs), and writing processes (planning, drafting, revising, and editing). In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, researchers coded the participant's texts for use of connectives, discourse demonstratives, average sentence length, off-register words, use of the first person pronoun, and the ratio of definite articles to indefinite articles.

Since coding is inherently subjective, more than one coder is usually employed. In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, three rhetoricians were employed to code the participant's texts for off-register phrases. The researchers established the agreement among the coders before concluding that the participant used fewer off-register words as the graduate program progressed.

Composing the Case Study Report

In the many forms it can take, "a case study is generically a story; it presents the concrete narrative detail of actual, or at least realistic events, it has a plot, exposition, characters, and sometimes even dialogue" (Boehrer 1990). Generally, case study reports are extensively descriptive, with "the most problematic issue often referred to as being the determination of the right combination of description and analysis" (1990). Typically, authors address each step of the research process, and attempt to give the reader as much context as possible for the decisions made in the research design and for the conclusions drawn.

This contextualization usually includes a detailed explanation of the researchers' theoretical positions, of how those theories drove the inquiry or led to the guiding research questions, of the participants' backgrounds, of the processes of data collection, of the training and limitations of the coders, along with a strong attempt to make connections between the data and the conclusions evident.

Although the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study does not, case study reports often include the reactions of the participants to the study or to the researchers' conclusions. Because case studies tend to be exploratory, most end with implications for further study. Here researchers may identify significant variables that emerged during the research and suggest studies related to these, or the authors may suggest further general questions that their case study generated.

For example, Emig's (1971) study concludes with a section dedicated solely to the topic of implications for further research, in which she suggests several means by which this particular study could have been improved, as well as questions and ideas raised by this study which other researchers might like to address, such as: is there a correlation between a certain personality and a certain composing process profile (e.g. is there a positive correlation between ego strength and persistence in revising)?

Also included in Emig's study is a section dedicated to implications for teaching, which outlines the pedagogical ramifications of the study's findings for teachers currently involved in high school writing programs.

Sharan Merriam (1985) also offers several suggestions for alternative presentations of data:

- Prepare specialized condensations for appropriate groups.

- Replace narrative sections with a series of answers to open-ended questions.

- Present "skimmer's" summaries at beginning of each section.

- Incorporate headlines that encapsulate information from text.

- Prepare analytic summaries with supporting data appendixes.

- Present data in colorful and/or unique graphic representations.

Issues of Validity and Reliability

Once key variables have been identified, they can be analyzed. Reliability becomes a key concern at this stage, and many case study researchers go to great lengths to ensure that their interpretations of the data will be both reliable and valid. Because issues of validity and reliability are an important part of any study in the social sciences, it is important to identify some ways of dealing with results.

Multi-modal case study researchers often balance the results of their coding with data from interviews or writer's reflections upon their own work. Consequently, the researchers' conclusions become highly contextualized. For example, in a case study which looked at the time spent in different stages of the writing process, Berkenkotter concluded that her participant, Donald Murray, spent more time planning his essays than in other writing stages. The report of this case study is followed by Murray's reply, wherein he agrees with some of Berkenkotter's conclusions and disagrees with others.

As is the case with other research methodologies, issues of external validity, construct validity, and reliability need to be carefully considered.

Commentary on Case Studies

Researchers often debate the relative merits of particular methods, among them case study. In this section, we comment on two key issues. To read the commentaries, choose any of the items below:

Strengths and Weaknesses of Case Studies

Most case study advocates point out that case studies produce much more detailed information than what is available through a statistical analysis. Advocates will also hold that while statistical methods might be able to deal with situations where behavior is homogeneous and routine, case studies are needed to deal with creativity, innovation, and context. Detractors argue that case studies are difficult to generalize because of inherent subjectivity and because they are based on qualitative subjective data, generalizable only to a particular context.

Flexibility

The case study approach is a comparatively flexible method of scientific research. Because its project designs seem to emphasize exploration rather than prescription or prediction, researchers are comparatively freer to discover and address issues as they arise in their experiments. In addition, the looser format of case studies allows researchers to begin with broad questions and narrow their focus as their experiment progresses rather than attempt to predict every possible outcome before the experiment is conducted.

Emphasis on Context

By seeking to understand as much as possible about a single subject or small group of subjects, case studies specialize in "deep data," or "thick description"--information based on particular contexts that can give research results a more human face. This emphasis can help bridge the gap between abstract research and concrete practice by allowing researchers to compare their firsthand observations with the quantitative results obtained through other methods of research.

Inherent Subjectivity

"The case study has long been stereotyped as the weak sibling among social science methods," and is often criticized as being too subjective and even pseudo-scientific. Likewise, "investigators who do case studies are often regarded as having deviated from their academic disciplines, and their investigations as having insufficient precision (that is, quantification), objectivity and rigor" (Yin 1989). Opponents cite opportunities for subjectivity in the implementation, presentation, and evaluation of case study research. The approach relies on personal interpretation of data and inferences. Results may not be generalizable, are difficult to test for validity, and rarely offer a problem-solving prescription. Simply put, relying on one or a few subjects as a basis for cognitive extrapolations runs the risk of inferring too much from what might be circumstance.

High Investment

Case studies can involve learning more about the subjects being tested than most researchers would care to know--their educational background, emotional background, perceptions of themselves and their surroundings, their likes, dislikes, and so on. Because of its emphasis on "deep data," the case study is out of reach for many large-scale research projects which look at a subject pool in the tens of thousands. A budget request of $10,000 to examine 200 subjects sounds more efficient than a similar request to examine four subjects.

Ethical Considerations

Researchers conducting case studies should consider certain ethical issues. For example, many educational case studies are often financed by people who have, either directly or indirectly, power over both those being studied and those conducting the investigation (1985). This conflict of interests can hinder the credibility of the study.

The personal integrity, sensitivity, and possible prejudices and/or biases of the investigators need to be taken into consideration as well. Personal biases can creep into how the research is conducted, alternative research methods used, and the preparation of surveys and questionnaires.

A common complaint in case study research is that investigators change direction during the course of the study unaware that their original research design was inadequate for the revised investigation. Thus, the researchers leave unknown gaps and biases in the study. To avoid this, researchers should report preliminary findings so that the likelihood of bias will be reduced.

Concerns about Reliability, Validity, and Generalizability

Merriam (1985) offers several suggestions for how case study researchers might actively combat the popular attacks on the validity, reliability, and generalizability of case studies:

- Prolong the Processes of Data Gathering on Site: This will help to insure the accuracy of the findings by providing the researcher with more concrete information upon which to formulate interpretations.

- Employ the Process of "Triangulation": Use a variety of data sources as opposed to relying solely upon one avenue of observation. One example of such a data check would be what McClintock, Brannon, and Maynard (1985) refer to as a "case cluster method," that is, when a single unit within a larger case is randomly sampled, and that data treated quantitatively." For instance, in Emig's (1971) study, the case cluster method was employed, singling out the productivity of a single student named Lynn. This cluster profile included an advanced case history of the subject, specific examination and analysis of individual compositions and protocols, and extensive interview sessions. The seven remaining students were then compared with the case of Lynn, to ascertain if there are any shared, or unique dimensions to the composing process engaged in by these eight students.

- Conduct Member Checks: Initiate and maintain an active corroboration on the interpretation of data between the researcher and those who provided the data. In other words, talk to your subjects.

- Collect Referential Materials: Complement the file of materials from the actual site with additional document support. For example, Emig (1971) supports her initial propositions with historical accounts by writers such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and D.H. Lawrence. Emig also cites examples of theoretical research done with regards to the creative process, as well as examples of empirical research dealing with the writing of adolescents. Specific attention is then given to the four stages description of the composing process delineated by Helmoltz, Wallas, and Cowley, as it serves as the focal point in this study.

- Engage in Peer Consultation: Prior to composing the final draft of the report, researchers should consult with colleagues in order to establish validity through pooled judgment.

Although little can be done to combat challenges concerning the generalizability of case studies, "most writers suggest that qualitative research should be judged as credible and confirmable as opposed to valid and reliable" (Merriam 1985). Likewise, it has been argued that "rather than transplanting statistical, quantitative notions of generalizability and thus finding qualitative research inadequate, it makes more sense to develop an understanding of generalization that is congruent with the basic characteristics of qualitative inquiry" (1985). After all, criticizing the case study method for being ungeneralizable is comparable to criticizing a washing machine for not being able to tell the correct time. In other words, it is unjust to criticize a method for not being able to do something which it was never originally designed to do in the first place.

Annotated Bibliography

Armisted, C. (1984). How Useful are Case Studies. Training and Development Journal, 38 (2), 75-77.

This article looks at eight types of case studies, offers pros and cons of using case studies in the classroom, and gives suggestions for successfully writing and using case studies.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1997). Beyond Methods: Components of Second Language Teacher Education . New York: McGraw-Hill.

A compilation of various research essays which address issues of language teacher education. Essays included are: "Non-native reading research and theory" by Lee, "The case for Psycholinguistics" by VanPatten, and "Assessment and Second Language Teaching" by Gradman and Reed.

Bartlett, L. (1989). A Question of Good Judgment; Interpretation Theory and Qualitative Enquiry Address. 70th Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco.

Bartlett selected "quasi-historical" methodology, which focuses on the "truth" found in case records, as one that will provide "good judgments" in educational inquiry. He argues that although the method is not comprehensive, it can try to connect theory with practice.

Baydere, S. et. al. (1993). Multimedia conferencing as a tool for collaborative writing: a case study in Computer Supported Collaborative Writing. New York: Springer-Verlag.

The case study by Baydere et. al. is just one of the many essays in this book found in the series "Computer Supported Cooperative Work." Denley, Witefield and May explore similar issues in their essay, "A case study in task analysis for the design of a collaborative document production system."

Berkenkotter, C., Huckin, T., N., & Ackerman J. (1988). Conventions, Conversations, and the Writer: Case Study of a Student in a Rhetoric Ph.D. Program. Research in the Teaching of English, 22, 9-44.

The authors focused on how the writing of their subject, Nate or Ackerman, changed as he became more acquainted or familiar with his field's discourse community.

Berninger, V., W., and Gans, B., M. (1986). Language Profiles in Nonspeaking Individuals of Normal Intelligence with Severe Cerebral Palsy. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2, 45-50.

Argues that generalizations about language abilities in patients with severe cerebral palsy (CP) should be avoided. Standardized tests of different levels of processing oral language, of processing written language, and of producing written language were administered to 3 male participants (aged 9, 16, and 40 yrs).

Bockman, J., R., and Couture, B. (1984). The Case Method in Technical Communication: Theory and Models. Texas: Association of Teachers of Technical Writing.

Examines the study and teaching of technical writing, communication of technical information, and the case method in terms of those applications.

Boehrer, J. (1990). Teaching With Cases: Learning to Question. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 42 41-57.

This article discusses the origins of the case method, looks at the question of what is a case, gives ideas about learning in case teaching, the purposes it can serve in the classroom, the ground rules for the case discussion, including the role of the question, and new directions for case teaching.

Bowman, W. R. (1993). Evaluating JTPA Programs for Economically Disadvantaged Adults: A Case Study of Utah and General Findings . Washington: National Commission for Employment Policy.

"To encourage state-level evaluations of JTPA, the Commission and the State of Utah co-sponsored this report on the effectiveness of JTPA Title II programs for adults in Utah. The technique used is non-experimental and the comparison group was selected from registrants with Utah's Employment Security. In a step-by-step approach, the report documents how non-experimental techniques can be applied and several specific technical issues can be addressed."

Boyce, A. (1993) The Case Study Approach for Pedagogists. Annual Meeting of the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. (Address). Washington DC.

This paper addresses how case studies 1) bridge the gap between teaching theory and application, 2) enable students to analyze problems and develop solutions for situations that will be encountered in the real world of teaching, and 3) helps students to evaluate the feasibility of alternatives and to understand the ramifications of a particular course of action.

Carson, J. (1993) The Case Study: Ideal Home of WAC Quantitative and Qualitative Data. Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication. (Address). San Diego.

"Increasingly, one of the most pressing questions for WAC advocates is how to keep [WAC] programs going in the face of numerous difficulties. Case histories offer the best chance for fashioning rhetorical arguments to keep WAC programs going because they offer the opportunity to provide a coherent narrative that contextualizes all documents and data, including what is generally considered scientific data. A case study of the WAC program, . . . at Robert Morris College in Pittsburgh demonstrates the advantages of this research method. Such studies are ideal homes for both naturalistic and positivistic data as well as both quantitative and qualitative information."

---. (1991). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. College Composition and Communication. 32. 365-87.

No abstract available.

Cromer, R. (1994) A Case Study of Dissociations Between Language and Cognition. Constraints on Language Acquisition: Studies of Atypical Children . Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 141-153.

Crossley, M. (1983) Case Study in Comparative and International Education: An Approach to Bridging the Theory-Practice Gap. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference of the Australian Comparative and International Education Society. Hamilton, NZ.

Case study research, as presented here, helps bridge the theory-practice gap in comparative and international research studies of education because it focuses on the practical, day-to-day context rather than on the national arena. The paper asserts that the case study method can be valuable at all levels of research, formation, and verification of theories in education.

Daillak, R., H., and Alkin, M., C. (1982). Qualitative Studies in Context: Reflections on the CSE Studies of Evaluation Use . California: EDRS

The report shows how the Center of the Study of Evaluation (CSE) applied qualitative techniques to a study of evaluation information use in local, Los Angeles schools. It critiques the effectiveness and the limitations of using case study, evaluation, field study, and user interview survey methodologies.

Davey, L. (1991). The Application of Case Study Evaluations. ERIC/TM Digest.

This article examines six types of case studies, the type of evaluation questions that can be answered, the functions served, some design features, and some pitfalls of the method.

Deutch, C. E. (1996). A course in research ethics for graduate students. College Teaching, 44, 2, 56-60.

This article describes a one-credit discussion course in research ethics for graduate students in biology. Case studies are focused on within the four parts of the course: 1) major issues, 2 )practical issues in scholarly work, 3) ownership of research results, and 4) training and personal decisions.

DeVoss, G. (1981). Ethics in Fieldwork Research. RIE 27p. (ERIC)

This article examines four of the ethical problems that can happen when conducting case study research: acquiring permission to do research, knowing when to stop digging, the pitfalls of doing collaborative research, and preserving the integrity of the participants.

Driscoll, A. (1985). Case Study of a Research Intervention: the University of Utah’s Collaborative Approach . San Francisco: Far West Library for Educational Research Development.

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, Denver, CO, March 1985. Offers information of in-service training, specifically case studies application.

Ellram, L. M. (1996). The Use of the Case Study Method in Logistics Research. Journal of Business Logistics, 17, 2, 93.

This article discusses the increased use of case study in business research, and the lack of understanding of when and how to use case study methodology in business.

Emig, J. (1971) The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders . Urbana: NTCE.

This case study uses observation, tape recordings, writing samples, and school records to show that writing in reflexive and extensive situations caused different lengths of discourse and different clusterings of the components of the writing process.

Feagin, J. R. (1991). A Case For the Case Study . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

This book discusses the nature, characteristics, and basic methodological issues of the case study as a research method.

Feldman, H., Holland, A., & Keefe, K. (1989) Language Abilities after Left Hemisphere Brain Injury: A Case Study of Twins. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 9, 32-47.

"Describes the language abilities of 2 twin pairs in which 1 twin (the experimental) suffered brain injury to the left cerebral hemisphere around the time of birth and1 twin (the control) did not. One pair of twins was initially assessed at age 23 mo. and the other at about 30 mo.; they were subsequently evaluated in their homes 3 times at about 6-mo intervals."

Fidel, R. (1984). The Case Study Method: A Case Study. Library and Information Science Research, 6.

The article describes the use of case study methodology to systematically develop a model of online searching behavior in which study design is flexible, subject manner determines data gathering and analyses, and procedures adapt to the study's progressive change.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1984). Images, Plans and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing. Written Communication, 1, 120-160.

Explores the ways in which writers actually use different forms of knowing to create prose.

Frey, L. R. (1992). Interpreting Communication Research: A Case Study Approach Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

The book discusses research methodologies in the Communication field. It focuses on how case studies bridge the gap between communication research, theory, and practice.

Gilbert, V. K. (1981). The Case Study as a Research Methodology: Difficulties and Advantages of Integrating the Positivistic, Phenomenological and Grounded Theory Approaches . The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association for the Study of Educational Administration. (Address) Halifax, NS, Can.

This study on an innovative secondary school in England shows how a "low-profile" participant-observer case study was crucial to the initial observation, the testing of hypotheses, the interpretive approach, and the grounded theory.

Gilgun, J. F. (1994). A Case for Case Studies in Social Work Research. Social Work, 39, 4, 371-381.

This article defines case study research, presents guidelines for evaluation of case studies, and shows the relevance of case studies to social work research. It also looks at issues such as evaluation and interpretations of case studies.

Glennan, S. L., Sharp-Bittner, M. A. & Tullos, D. C. (1991). Augmentative and Alternative Communication Training with a Nonspeaking Adult: Lessons from MH. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 7, 240-7.

"A response-guided case study documented changes in a nonspeaking 36-yr-old man's ability to communicate using 3 trained augmentative communication modes. . . . Data were collected in videotaped interaction sessions between the nonspeaking adult and a series of adult speaking."

Graves, D. (1981). An Examination of the Writing Processes of Seven Year Old Children. Research in the Teaching of English, 15, 113-134.

Hamel, J. (1993). Case Study Methods . Newbury Park: Sage. .

"In a most economical fashion, Hamel provides a practical guide for producing theoretically sharp and empirically sound sociological case studies. A central idea put forth by Hamel is that case studies must "locate the global in the local" thus making the careful selection of the research site the most critical decision in the analytic process."

Karthigesu, R. (1986, July). Television as a Tool for Nation-Building in the Third World: A Post-Colonial Pattern, Using Malaysia as a Case-Study. International Television Studies Conference. (Address). London, 10-12.

"The extent to which Television Malaysia, as a national mass media organization, has been able to play a role in nation building in the post-colonial period is . . . studied in two parts: how the choice of a model of nation building determines the character of the organization; and how the character of the organization influences the output of the organization."

Kenny, R. (1984). Making the Case for the Case Study. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 16, (1), 37-51.

The article looks at how and why the case study is justified as a viable and valuable approach to educational research and program evaluation.

Knirk, F. (1991). Case Materials: Research and Practice. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 4 (1 ), 73-81.

The article addresses the effectiveness of case studies, subject areas where case studies are commonly used, recent examples of their use, and case study design considerations.

Klos, D. (1976). Students as Case Writers. Teaching of Psychology, 3.2, 63-66.

This article reviews a course in which students gather data for an original case study of another person. The task requires the students to design the study, collect the data, write the narrative, and interpret the findings.

Leftwich, A. (1981). The Politics of Case Study: Problems of Innovation in University Education. Higher Education Review, 13.2, 38-64.

The article discusses the use of case studies as a teaching method. Emphasis is on the instructional materials, interdisciplinarity, and the complex relationships within the university that help or hinder the method.

Mabrito, M. (1991, Oct.). Electronic Mail as a Vehicle for Peer Response: Conversations of High and Low Apprehensive Writers. Written Communication, 509-32.

McCarthy, S., J. (1955). The Influence of Classroom Discourse on Student Texts: The Case of Ella . East Lansing: Institute for Research on Teaching.

A look at how students of color become marginalized within traditional classroom discourse. The essay follows the struggles of one black student: Ella.

Matsuhashi, A., ed. (1987). Writing in Real Time: Modeling Production Processes Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Investigates how writers plan to produce discourse for different purposes to report, to generalize, and to persuade, as well as how writers plan for sentence level units of language. To learn about planning, an observational measure of pause time was used" (ERIC).

Merriam, S. B. (1985). The Case Study in Educational Research: A Review of Selected Literature. Journal of Educational Thought, 19.3, 204-17.

The article examines the characteristics of, philosophical assumptions underlying the case study, the mechanics of conducting a case study, and the concerns about the reliability, validity, and generalizability of the method.

---. (1988). Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Merry, S. E., & Milner, N. eds. (1993). The Possibility of Popular Justice: A Case Study of Community Mediation in the United States . Ann Arbor: U of Michigan.

". . . this volume presents a case study of one experiment in popular justice, the San Francisco Community Boards. This program has made an explicit claim to create an alternative justice, or new justice, in the midst of a society ordered by state law. The contributors to this volume explore the history and experience of the program and compare it to other versions of popular justice in the United States, Europe, and the Third World."

Merseth, K. K. (1991). The Case for Cases in Teacher Education. RIE. 42p. (ERIC).

This monograph argues that the case method of instruction offers unique potential for revitalizing the field of teacher education.

Michaels, S. (1987). Text and Context: A New Approach to the Study of Classroom Writing. Discourse Processes, 10, 321-346.

"This paper argues for and illustrates an approach to the study of writing that integrates ethnographic analysis of classroom interaction with linguistic analysis of written texts and teacher/student conversational exchanges. The approach is illustrated through a case study of writing in a single sixth grade classroom during a single writing assignment."