- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review

- Nina Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Jia Chen 3 ,

- Wenjun Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5398-8508 4 , 5 ,

- Zhengkun Shi 1 ,

- Huaping Yang 1 ,

- Peng Liu 6 ,

- Xiao Wei 7 ,

- Xiangling Dong 6 ,

- Chen Wang 3 ,

- Ling Mao 8 &

- Xianhong Li 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 1247 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2277 Accesses

18 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Case management (CM) is widely utilized to improve health outcomes of cancer patients, enhance their experience of health care, and reduce the cost of care. While numbers of systematic reviews are available on the effectiveness of CM for cancer patients, they often arrive at discordant conclusions that may confuse or mislead the future case management development for cancer patients and relevant policy making. We aimed to summarize the existing systematic reviews on the effectiveness of CM in health-related outcomes and health care utilization outcomes for cancer patient care, and highlight the consistent and contradictory findings.

An umbrella review was conducted followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review methodology. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus for reviews published up to July 8th, 2022. Quality of each review was appraised with the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. A narrative synthesis was performed, the corrected covered area was calculated as a measure of overlap for the primary studies in each review. The results were reported followed the Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews checklist.

Eight systematic reviews were included. Average quality of the reviews was high. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (corrected covered area = 4.5%). No universal tools were used to measure the effect of CM on each outcome. Summarized results revealed that CM were more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ quality of life, self-efficacy, survivor status, and satisfaction. Rare significant effect was reported on cost and length of stay.

Conclusions

CM showed mixed effects in cancer patient care. Future research should use standard guidelines to clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation. More primary studies are needed using high-quality well-powered designs to provide solid evidence on the effectiveness of CM. Case managers should consider applying validated and reliable tools to evaluate effect of CM in multifaced outcomes of cancer patient care.

Peer Review reports

Cancer ranks as one of the leading causes of premature death among population around 30–69 years old across 134 countries [ 1 ], and the global incidence of cancer is about to reach 30.2 million new cases and 25.7 million deaths by 2040 [ 2 ]. Earlier detection and diagnosis, and development of diverse cancer treatments have increased the survival rate of cancer patients. According to Quaresma et al. [ 3 ], the cancer survival in the UK has doubled over the last 40 years alongside the advancement in cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, number of challenges exist in the current cancer care all over the world. Many cancer patients oftentimes receive a series of long-running and exhausting multi-modal treatments and experience descent in psychological, physical and social functioning, which have a significant negative impact on their quality of life (QoL) [ 4 , 5 ]. In addition, the significant healthcare spending and productivity losses of cancer patients lead to a heavy patient economic burden, which is another substantial issue with cancer care [ 6 ]. A systematic approach is needed to mobilize and deliver appropriate resources, provide accessible, safe, and well-coordinated care for cancer patients received stressful treatments and shouldered heavy economic burden [ 7 ].

Case management (CM) is defined by the Case Management Society of America (CMSA) as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” (P. 11) [ 8 ]. According to the definition, CM is designed to use resources effectively to improve the quality of treatments, patient care services, and QoL of patients while reducing the relevant healthcare costs.

With the worldwide utilization of CM in cancer patient care, studies examining the effect of CM in improving patient-related outcomes or healthcare service use outcomes have been skyrocketing. Numbers of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published to synthesis the effectiveness of CM in recent years and often arrive at discordant conclusions. For example, Joo et al. [ 9 ] retrieved and synthesised results from nine experimental studies and found that CM effectively improved patients’ QoL and symptom management. While Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported equivocal effect on both QoL and symptom management. Chan et al. [ 11 ] reported that four of the five randomized controlled trials showed insignificant impact of CM on patients’ QoL. The inconsistent evidence on the impact of CM may confuse or mislead the future case management development and relevant policy making. Considering the exist of several systematic reviews and research synthesis available to inform the application of case management for cancer patient care improvement, umbrella review could now be undertaken to compare and contrast published reviews and to highlight the consistent or contradictory findings around the effect of CM on manifold aspects of cancer patient care [ 12 ]. Thus, the current review was conducted to 1) synthesis systematic reviews that assess the effects of CM on cancer patient outcomes (e.g., QoL, functioning status, symptom management, satisfaction, etc.) and health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay, treatment received compliance, etc.), 2) summarize measurement used in evaluating patient outcomes and health care utilization outcomes.

This umbrella review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review (UR) methodology [ 12 ] and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of systematic reviews (PRIO) checklist (see Additional file 1 ) [ 13 ]. This review has been registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7YQAP ).

Study searching methods

We performed literature search in five databases including MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus from inception to July 2022. Ethical approval and patient consent were not necessary since all analyses were based on previously published articles. The searching strategies in all five databases were developed with the help of a health science librarian. See Additional file 2 for the searching strategy and results in MEDLINE (Ovid). The studies were selected using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals diagnosed with any type of cancer at any cancer stages (early to advanced). Reviews targeted on people with no specified cancer diagnose were excluded.

Intervention

Case management interventions targeted on cancer patients. Case management is defined as a “collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” [ 8 ]. Only reviews in which the effectiveness of CM as defined above was analyzed separately from other interventions were considered.

Individuals in comparison groups received “treatment as usual” (TAU). TAU may include various interventions called “standard of care,” “usual care,” or “standard treatment,” but generally refers to treatment as it is commonly provided. Only studies that compared case management with “TAU” were selected.

Patient outcomes (e.g., quality of life, symptom management, functioning status), health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay), etc.

Acute care hospitals and primary care settings (e.g., long-term care, nursing homes, community care services). Hospital was defined as any department of internal medicine or surgery as well as unspecified hospital settings.

Study design

Systematic review/meta-analysis that only included quantitative studies. We excluded studies full-texts unavailable online.

Study selection

All retrieved studies were imported into Covidence systematic review software [ 14 ] and the duplicates were removed. Then, titles and abstracts were independently assessed by two researchers (XW and XD) according to the inclusion criteria. After that, the full texts of the selected abstracts were obtained and reviewed by the same two researchers (XW and XD) independently. The reference list of included studies was reviewed and searched for additional studies. Any disagreement between the two researchers were resolved through consultation with a senior researcher (PL).

Quality appraisal for included reviews

Two reviewers (NW and LM) independently assessed the methodological quality of the individual studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [ 15 ]. The tool aims to determine the extent to which the review has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis [ 15 ]. It consists of 11 criteria scored as yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. We adopted a scoring system used in previously published systematic reviews [ 16 , 17 ]. For each article, a rating score was derived by taking the number obtained in the quality rating and dividing it by the total number of possible points allowed, giving each manuscript a total quality rating between 0 and 1. Studies were then classified as low (0–0.25), low-moderate (0.26–0.50), moderate (0.51–0.75), or high (0.76–1.0).

Data extraction

We developed the data extraction form based on the research questions, and extracted following information: characteristics of included reviews such as publication year range, whether conducted meta-analysis or not, type of cancer patients, age of population, type and number of primary studies included; intervention names, components, and duration; outcomes and evaluation tools used; author’s conclusions and interpretations. Two researchers (NW and LM) extracted data independently from all included articles into an Excel spreadsheet and another researcher (XL) verified it for accuracy.

Data synthesis

We were unable to statistically pool outcomes due to the heterogeneity of outcomes of the included reviews. Therefore, we conducted a narrative synthesis [ 18 ] of the numerical data of individual studies outcomes. The studies were summarized and synthesised by two reviewers (NW and ZS) independently and double checked by a third author (HY). Following the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we used a summary table to present clear, specific, and structured results from the selected reviews, and then synthesised these results to identify broad conclusions. To summarized information about the interventions we coded data into features, components and delivery strategies, and inductively developed themes within each domain as they emerged from the studies. As suggested by Li and colleagues [ 19 ], we grouped outcomes into: global QoL of patients, functional status (i.e. physical, cognitive, emotional, role, social), symptom management, cost, hospital (re)admission, length of stay, treatment received compliance, provision of timely treatment.

For clarity the term ‘primary studies’ refers to the articles found within the included reviews. As several primary studies are included in more than one review, the overall results and conclusions of an overview can be biased. To assess this bias, the degree of overlap between reviews was calculated with the Corrected Covered Area (CCA) method. The details of the CCA calculation have been described by Pieper and colleagues [ 20 ] elsewhere. A CCA score of less than 5% is regarded as a slight overlap, 5–9.9% as moderate overlap, 10–14.9% as high overlap and over 15% as a very high level of overlap. This measure has been validated in which the number of overlapped primary publications has a strong correlation with the CCA [ 21 ].

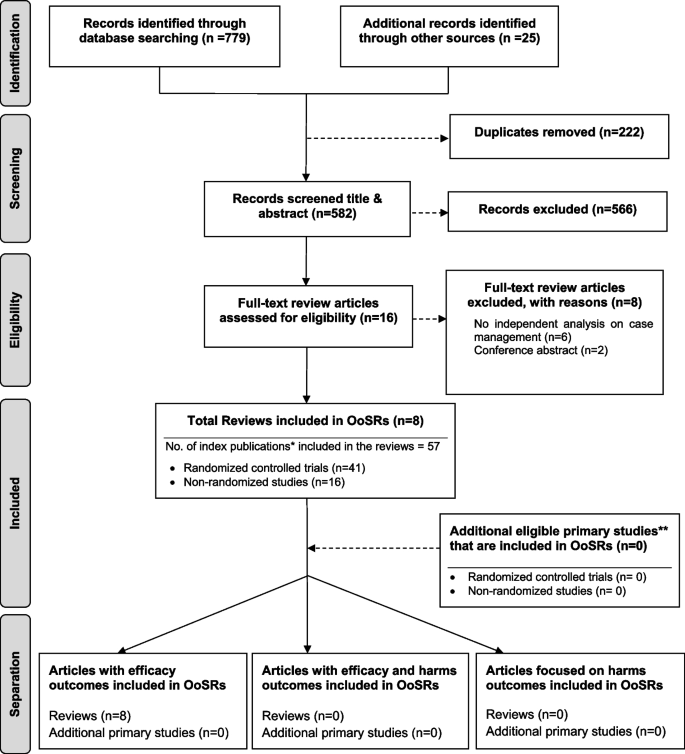

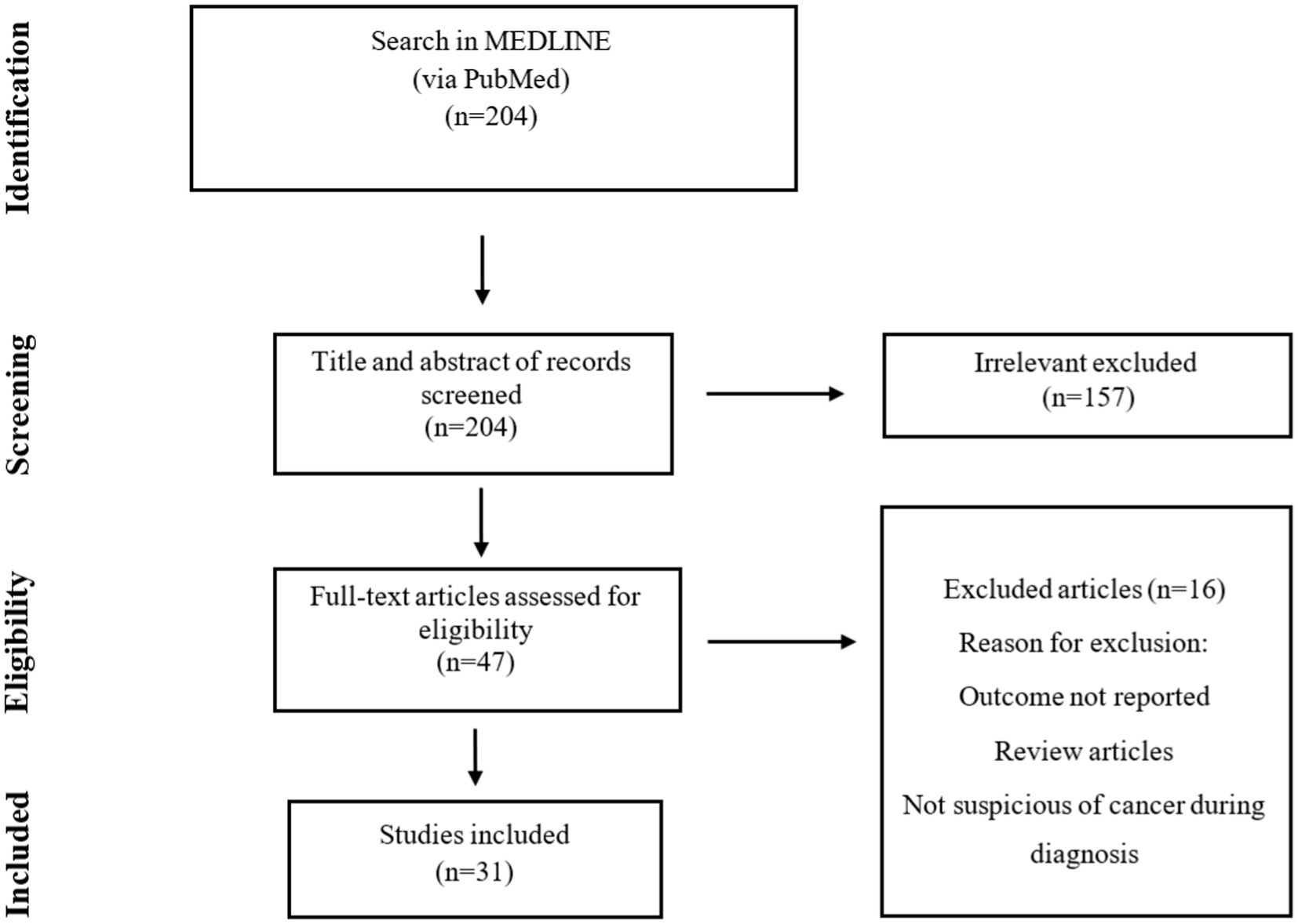

Search outcome

As shown in Fig. 1 , our search strategy generated 804 potentially relevant records. Upon removing the duplicates, 582 studies screened by title and abstract, 16 were identified for full text screening. We excluded eight of the 16 studies for the following reasons: no independent analysis on the effect of case management ( n = 6), or conference abstract ( n = 2). The eight remaining systematic reviews were selected and assessed for methodological quality. In total, all the eight reviews included 57 primary studies, among which 12 were duplicated included in two or three reviews. Forty-one of the 57 primary studies were randomized controlled trials (see Additional file 3 for included primary studies).

Flow chart for umbrella review. *Index publication is the first occurrence of a primary publication in the included reviews. **Additional eligible primary studies that had not been initially indentified by the search of the relevant reviews or obtained by updating the search of the included reviews

Methodological quality assessment

The quality assessment scores are presented in Table 1 . Only one review was rated as moderate because not clarify whether two or more reviewers independently assessed the quality of included primary studies, and did not report the methods to minimize errors in data extraction or publication bias. The other seven reviews were rated as high quality. Despite rated as strong, the seven reviews still companied with one or two issues on the assessment of heterogeneity, search strategy, and recommendations for policy and/or practice.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 presents a descriptive summary of characteristics of the eight systematic reviews [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The eight reviews aimed to identify evidence of the effectiveness of CM on cancer patients. Three of the studies were a systematic review with meta-analysis [ 10 , 25 , 26 ]. Five of the eight reviews adhered to the PRISMA statement [ 11 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], two adopted Cochrane systematic review methodology [ 9 , 10 ].

The eight reviews were published between 2008 and 2021, the primary studies in the reviews were published between 1983 and 2018. The number of primary studies regarding to CM included in each review ranged from three to 20. Five of the eight reviews included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the remaining reviews included a combination of study designs that involved RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental studies (e.g., cohort study). The age of review participants ranged from 7 to 97 years and mean ages range from 48.63 to 66.31 years, which covers populations from children to elders. The total number of participants in each review ranged from 327 to 9601. Seven of the eight reviews included primary studies targeted on multiple types of cancer including breast, lung, colorectal, cervical, ovarian, prostate, gastric, hepatocellular, etc. Most of the primary studies included in the eight reviews were conducted in the United States, and there were also studies conducted in Canada, Australia, Europe (i.e., Germany, UK, Turkey, Switzerland, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Netherlands) and East Asia (i.e., Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia).

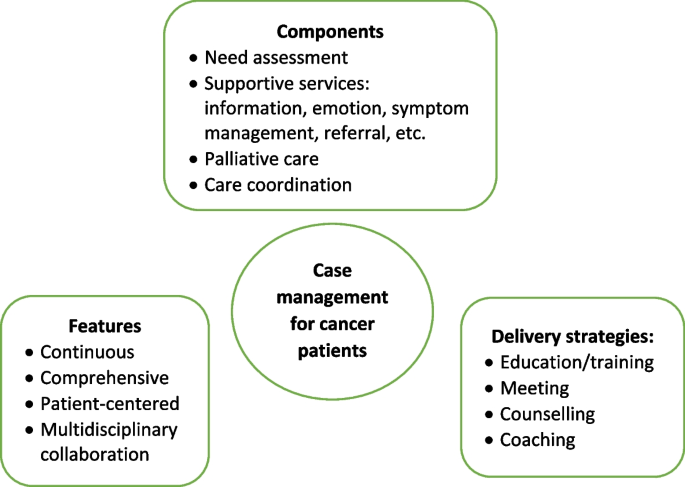

CM interventions

As shown in Table 2 , three studies reviewed trials of nurse-led CM interventions [ 9 , 25 , 26 ], two reviewed CM-like interventions that not termed as ‘CM’ while meet the CM definition by the CMSA [ 8 , 23 , 24 ]. Only one study reviewed CM focus solely on skill-training or symptom management [ 19 ]. All studies reviewed trials that facilitated the CM in a multidisciplinary collaboration approach. The duration of CM ranged from 4 days to 5 years. We presented the feature, components and delivery strategies of CM interventions for cancer patients in Fig. 2 by summarizing descriptions in each review. Congruent with the components defined by CMSA [ 8 ], all CM interventions included patient assessment, supportive services such as information and emotion support, care coordination by conducting education, consultation, and in-person, telephone or online coaching for regular follow-up. One critical component of CM interventions for cancer patients is the provision of palliative care. Control groups (CGs) of all studies reviewed in the reviews received usual treatment of care.

Features, components, and delivery strategies of case management for cancer patient care

Corrected Covered Area (CCA)

Table 3 presents the CCA for each outcome and as a whole. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (CCA = 4.5%). In addition, no overlapping of primary studies was found for six of the 16 outcomes, including self-efficacy, psychological function, hospital (re)admissions, length of stay, and provision of timely treatment. Only one outcome (i.e., symptom management) showed slight overlap (0.7%). The CCA for other five outcomes (i.e., global QoL, physical function, role function, patient satisfaction, cost) evaluated by more than 2 reviews were between 5 to 9.9%, indicated a moderate overlap. The CCA for survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance were over 10%.

Measurement used

Table 4 presents the quantitative measurement used in primary studies. As shown in Table 4 , studies investigated global QoL using different QoL-related scales, among which Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) (used in 15 primary studies) were most frequently applied, followed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) (used in 11 primary studies), and short form health survey (i.e., SF-8, SF-12, SF-36) (used in 10 primary studies). Different types of FACT tool were used according to the cancer types. For example, FACT-G was used for general cancer patients assessment, and FACT-B was used to evaluate breast cancer-related QoL. For the assessment of overall symptom management, SF-36 and Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) were used most frequently (used in four primary studies each). Different dimensions of SF-36 were also applied to evaluate other outcomes such as physical, emotional, and social function. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was the top employed tool in measuring the psychological function of patients. Patients’ sick leave days and the number of patients return to work were top employed metrics to evaluate the role function of patients. No unified tools were utilized to assess patient satisfaction towards the CM and majority of the primary studies used self-developed questionnaires.

Effect of CM on patient and health care utilization outcomes

The main outcomes from the seven systematic reviews are presented and summarized in Table 5 . Seven of the eight reviews reported the effects of case management on patients’ global QoL and showed mixed findings. Around half (49%, 19/39) of the primary studies included in the seven reviews reported significant positive impact of CM on global QoL. As for the functional status, there was a strong concordance among primary studies regarding the effectiveness of CM in improving cognitive function (e.g., uncertainty, health perceptions) (89%, 8/9); Equivocal effects were reported on psychological (e.g., patient anxiety, depression), physical (e.g., arm function), role function (e.g., sick leave days, patients returning to work), emotional (e.g., mood) and social function (e.g., social support) [ 9 , 11 , 26 ]. The findings regard to symptom management were more positive, with 75% (18/24) primary studies included in seven reviews revealed significant positive impact of CM on symptom severity and symptom distress decrease of pain, nausea, fatigue, discomfort, etc. Three of the four primary studies in two reviews [ 9 , 11 ] showed no significant influence of CM on patients’ self-efficacy. Wulff et al. [ 23 ] and Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported mixed findings on the impact of CM on survivor status, with four of the six primary studies reported significant positive impact. The effect of CM on patient satisfaction was reported in five reviews and showed mixed results.

Of the eleven primary studies reported cost, only one controlled before-and-after study in Joo et al.’s [ 9 ] review reported significant impact on monthly cancer-related medical costs. The evidence concerning patients’ length of stay yielded no significant findings. Overall significant positive effect was reported on hospital (re)admission (e.g., inpatient and ICU admission rate), treatment received compliance (e.g., therapy acceptance or completion rate), and provision of timely treatment.

This umbrella review is the first to summarize the results of systematic reviews that synthesised the evidence on the effectiveness of CM on cancer patient outcomes and relevant health care utilization. Most reviews (7/8) showed a high methodological quality. Different tools were used to measure the effect of CM on the same outcome. The evidence regards to the effectiveness of CM is mixed. The summarized results revealed that CM was more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ global QoL, psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function, self-efficacy, survivor status, and patient satisfaction.

No universal tools were used to measure improvement of each outcome in the CM group compared with the control group, making it challenging to conduct a meta-analysis of studies results [ 22 , 27 ]. This is a common issue faced the included reviews. Five of the eight reviews failed to conduct meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity [ 9 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 ]. Joo and Huber [ 22 ] conducted a review of reviews on the effect of CM on health care utilization outcome of chronic illness patients, they recognized the same problem and suggested using valid and standardized tools to minimize the differences in measurements. Despite various tools used, our review showed that FACT, EORTC QLQ-C30, and short form health survey (i.e., SF 36, SF 12, and SF 8) were most frequently applied to measure the effect of CM on the global QoL of cancer patients. These tools were also used in evaluating specific dimensions of QoL such as psychological, physical, emotional, and social function. This aligned with previous reviews [ 28 , 29 ] that found FACT and EORTC QLQ-C30 were the most common and well developed QoL instruments in cancer patients. FACT-G is considered appropriate for use with any types of cancer patients [ 30 ]. It is a 27-item tool that includes four primary QoL domains: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being [ 31 ]. Other versions of FACT (FACT-B [ 32 ], FACT-L [ 33 ] and FACT-E [ 34 ]) for specific type of cancer patients were developed by incorporating the four dimensions of FACT-G with additional cancer type-specific questions. EORTC QLQ-C30 was another type of QoL assessment tools for cancer patients specifically. It was developed by Aaronson et al. [ 35 ] and contains four domains: physical, emotional, cognitive and social functions, and a higher score indicates better QoL. The Short Form Health Survey is the most commonly used measure in evaluating QoL domains of patients suffering from a wide range of medical conditions [ 36 ]. Research found it provides reliable and valid indication of general health among cancer patients [ 37 , 38 ].

QoL is the most frequently evaluated outcome in our review with 39 primary studies in seven reviews reported the global QoL of cancer patients. Joo et al. [ 9 ] found that CM interventions improved QoL of cancer patients. Yin and colleagues [ 24 ] revealed that cancer patients achieved better physical and psychological condition through symptom management, needs assessment, direct referrals, and other services in CM. However, summarized results in our review show that the CM had equivocal effect on cancer patients’ global QoL and dimensions including psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function. Cognitive function is the only dimension showed positive change. Despite CM interventions share similar definitions and principles [ 8 ]. It is hard to foresee which aspect(s) of CM interventions contribute to certain effects due to their comprehensiveness [ 24 ]. Yin et al. [ 24 ] argued that the control group may receive a higher quality treatment than planned usual care since all the participants were not blinded and they have been informed about the aim of the study. Indicating a more rigorous design and evaluation is needed to avoid this information bias.

In the meantime, included reviews claimed that few primary studies reported enough details about CM interventions, including model used [ 10 , 11 ], dose and intensity [ 9 , 19 , 24 ], interventionist qualifications [ 11 ], protocol or manual used [ 9 , 23 ], and fidelity [ 23 ]. Particularly, the COVID-19 pandemic has considerable influence on the care delivery for cancer patients. For example, the more frequently utilization of remote patient monitoring technologies that incorporate community resources, primary care and allied health disciplines, as well as clinics to keep cancer patients away from acute care hospitals as much as possible [ 39 ]. Many of these changes have been integrated within routine case management for cancer care during the pandemic [ 39 ]. It is well-needed to report how those CM intervention were conducted follow standard reporting guidelines, in order to provide recommendation for future research.

Our review showed that CM is likely to improve the symptom management. Eighteen of the 24 included primary studies reported positive effect of CM on symptom management, including decrease symptom distress or severity of fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting. The same positive effect on symptom management was also revealed in other types of patients. Joo and colleagues [ 40 ] found that CM reduced substance use and significantly influenced abstinence rates among populations experienced substance disorders. Reviews by Stokes et al. [ 27 ] and Welch et al. [ 41 ] revealed positive effect on symptom release among people with long-term conditions and diabetes patients, respectively. The multidisciplinary collaboration approach adopted [ 10 ], and availability of professional support post-hospitalization [ 9 , 41 ] in CM might contribute to the improvement of symptom management. Specifically, multidisciplinary team involves physicians, nurses, and aligned healthcare professionals provides throughout and multifaced symptom assessment and management [ 10 ]. In addition, CM programs continuously follow up and advocate for patients’ concerns [ 8 ]. Specifically, case managers are available to patients 24 hours a day by phone call even after discharged, providing opportunity for immediate professional guidance on symptom management [ 9 ].

As for other patient outcomes, there is insufficient evidence of effect on self-efficacy and survivor status of cancer patients. Only three and four primary studies in total reported these two outcomes, respectively. Eleven primary studies in five reviews reported patient satisfaction and showed mixed results. Inconsistent results were found in a review of reviews by Buja et al. [ 7 ] which concluded strong evidence of CM improving satisfaction of patients with long term condition. In agreement with Joo and Huber’s [ 25 ] review, we found that CM favorably affect healthcare utilization outcomes such as treatment received compliance, hospital (re)admission, and provision of timely treatment. While the strength of the evidence was limited either by the high level of primary studies overlapping (CCA) (i.e., treatment received compliance, CCA = 13.3%) or the small number of studies reported certain outcomes (i.e., hospital admission, provision of timely treatment). Notably, the summarized results from included reviews conclude that despite theoretical benefits [ 8 ], in practice there is only slight evidence of benefits on reduction in the cost of care for cancer patients participated in CM interventions.

We provide some recommendations for future research based on the summarized results: 1) Future research should clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation, including theoretical underpinnings, dose and intensity, interventionist qualifications, protocol or manual used, fidelity, etc. In that way these details can be included in future systematic reviews, and effectiveness of individual elements of the intervention can be examined [ 27 ]. We recommend use standard guidelines to help organize the CM intervention reporting. For example, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDeiR) is one of the most popular guidelines that could be used to report the full breadth of CM interventions: from intervention rationale to assessments of treatment adherence and fidelity [ 42 ]. 2) More rigorous trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of CM. 3) Studies should also explore the barriers to and facilitators of CM implementation across various types of cancer patients at different stages, providing evidence for conducting successful CM implementation in the future.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted an umbrella review instead of a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of review outcomes. Although an umbrella review can only show the tendency or direction of the effect of CM rather than providing the magnitude or significance level of influence [ 12 ], the current evidence on the effect of CM in cancer patients was comprehensively summarized. There were some challenges when conducting the review. First, the quality of the umbrella reviews was greatly affected by the quality of the original reviews [ 12 ]. In this study, we confirmed that the quality of the original reviews were mostly high as assessed by the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [ 15 ]. Second, if the primary studies were included in several reviews, they may produce bias related to overlapping effects [ 20 ]. By calculating the CCA, we showed that 75% (12/16) of the individual outcomes had no to moderate overlapping of primary studies between included reviews, revealing that these results from each review were relatively independent. Cautious are needed on the summarized evidence regards to the effect of CM on survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance because of the high overlapping (CCA > 10) between the reviews reported those outcomes.

There are limitations in our review. The first limitation concerns that the searching was limited to English-language articles and did not access unpublished papers. Second, as suggested by the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we did not assess the quality of evidence from included reviews, it increased the uncertainty of the review findings.

Effective CM aims to influence the health care delivery system in improving the health outcomes of cancer patients, enhancing their experience of health care, and reducing the cost of care. Our review found mixed effects of CM reported in cancer patient care. The summarized results revealed that CM was likely to improve symptom management for cancer patients. We also found CM has the tendency to enhance cancer patients’ experience of health care such as reducing hospital (re)admission rates, improving treatment received compliance and provision of timely treatment. Only slight evidence of benefits was reported on reducing the cost of care for cancer patients. Overall, more rigorous designed primary studies are needed to demonstrate the effects of CM on cancer patients and explore the elements of effective CM interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

Corrected Covered Area

Control groups

- Case management

Case Management Society of America

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Breast Cancer

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Esophagus

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- General

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-Lung

- Quality of life

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Joanna Briggs Institute

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Randomized controlled trials

Symptom Distress Scale

Medical Outcomes Study 8-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 12-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey

Treatment as usual

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global cancer observatory: Cancer today: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today .

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global Cancer observatory: Cancer tomorrow: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow .

Quaresma M, Coleman MP, Rachet B. 40-year trends in an index of survival for all cancers combined and survival adjusted for age and sex for each cancer in England and Wales, 1971-2011: a population-based study. Lancet. 2015;385:1206–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61396-9 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–67. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468 .

Yan AF, Stevens P, Holt C, Walker A, Ng A, McManus P, et al. Culture, identity, strength and spirituality: a qualitative study to understand experiences of African American women breast cancer survivors and recommendations for intervention development. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28:e13013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13013 .

Article Google Scholar

Yabroff K, Mariotto A, Tangka F. Annual report to the nation on the status of Cancer, part II: patient economic burden associated with Cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1670–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab192 .

Buja A, Francesconi P, Bellini I, Barletta V, Girardi G, Braga M, et al. Health and health service usage outcomes of case management for patients with long-term conditions: a review of reviews. Prim Heal Care Res Dev. 2020;21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000080 .

Case Management Society of America. CMSA’s standards of practice for case management, Revised 2016. 2016. http://www.naylornetwork.com/cmsatoday/articles/index-v3.asp?aid=400028&issueID=53653 .

Google Scholar

Joo JY, Liu MF. Effectiveness of nurse-led case Management in Cancer Care: systematic review. Clin Nurs Res. 2019;28:968–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818773285 .

Aubin M, Giguère A, Martin M, Verreault R, Fitch MI, Kazanjian A, et al. Interventions to improve continuity of care in the follow-up of patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:1–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007672.pub2 .

Chan RJ, Teleni L, McDonald S, Kelly J, Mahony J, Ernst K, et al. Breast cancer nursing interventions and clinical effectiveness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:276–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002120 .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-11 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, Ntzani E, Haidich AB. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.002 .

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review sofware. Covidence. 2016. https://get.covidence.org/systematic-review-software?campaignid=15030045989&adgroupid=130408703002&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvc7KuJDO-QIVh97ICh1BeQKnEAAYASAAEgI4APD_BwE .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Heal. 2015;13:132–40 http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html .

Gifford W, Rowan M, Dick P, Modanloo S, Benoit M, Al AZ, et al. Interventions to improve cancer survivorship among indigenous peoples and communities : a systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:7029–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06216-7 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gifford W, Squires J, Angus D, Ashley L, Brosseau L, Craik J, et al. Managerial leadership for research use in nursing and allied health care professions : a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0817-7 .

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods Programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf .

Li Q, Lin Y, Liu X, Xu Y. A systematic review on patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors of randomised clinical trials: direction for future research. Psychooncology. 2014;23:721–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3504 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007 .

Choi J, Lee M, Lee JK, Kang D, Choi JY. Correlates associated with participation in physical activity among adults: a systematic review of reviews and update. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4255-2 .

Joo JY, Huber DL. Case management effectiveness on health care utilization outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41:111–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918762135 .

Wulff CN, Thygesen M, Søndergaard J, Vedsted P. Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–7 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/8/227 .

Yin YN, Wang Y, Jiang NJ, Long DR. Can case management improve cancer patients quality of life?: a systematic review following PRISMA. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022448 .

Wu YL, Padmalatha KMS, Yu T, Lin YH, Ku HC, Tsai YT, et al. Is nurse-led case management effective in improving treatment outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;00:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14874 .

McQueen J, McFeely G. Case management for return to work for individuals living with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24:203–10. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.5.203 .

Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, Checkland K, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Effectiveness of case management for “at risk” patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132340 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, Lauzier S, Théberge V. Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: an updated systematic review (2001-2009). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:178–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq508 .

Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:1–31 https://jeccr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-9966-27-32 .

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 .

Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The F unctional a ssessment of C hronic I llness T herapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 .

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy- breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–86. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.3.974 .

Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-F .

Darling G, Eton DT, Sulman J, Casson AG, Cella D. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22055 .

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 .

Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to score version two of the SF-36® health survey. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000.

Treanor C, Donnelly M. A methodological review of the short form health survey 36 (SF-36) and its derivatives among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:339–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0785-6 .

Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312116671725 .

Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Joseph R, Hart NH, Milley K, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2021:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01128-1 .

Joo J, Huber D. Community-based case management effectiveness in populations that abuse substances. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:536–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12201 .

Welch G, Garb J, Zagarins S, Lendel I, Gabbay RA. Nurse diabetes case management interventions and blood glucose control: results of a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.026 .

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Dual (co-)authorship

We declared that no author has authored one or more of the included systematic reviews.

This study was supported by 1) Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Nursing (2017TP1004, PI: Jia Chen), Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department, 2) Changsha Natural Science Foundation (kq2202365, PI: Nina Wang) Changsha Science and Technology Department, and 3) Management research foundation of Xiangya Hospital (2021GL12, PI: Nina Wang).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Nina Wang, Zhengkun Shi & Huaping Yang

National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, Xiangya Hospital, Changsha, China

Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

Jia Chen, Chen Wang & Xianhong Li

School of Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Wenjun Chen

Center for Research on Health and Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Intensive Care Unit of Cardiovascular Surgery Department, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Peng Liu & Xiangling Dong

The 956th Army Hospital, Linzhi, China

School of Nursing, Changsha Medical University, Changsha, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the production of this review. NW and WC conceptualized and designed the study and are the guarantor of the paper. JC and ZS conducted the literature search. PL, XW and XD were involved in the study screening. NW, LM and XL participated in the quality appraisal and data extraction. NW, ZS and HY conducted the data analysis. NW drafted the manuscript. WC and XL revised the manuscript. All authors participated in the review of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wenjun Chen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2..

Searching strategies.

Additional file 3.

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, N., Chen, J., Chen, W. et al. The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res 22 , 1247 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Download citation

Received : 04 April 2022

Accepted : 21 September 2022

Published : 14 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cancer patients

- Umbrella review

- Health care

- Outcome assessment

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Biomarker-Driven Lung Cancer

- HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Renal Cell Carcinoma

- CONFERENCES

- PUBLICATIONS

Case Presentation: A 72-Year-Old Woman With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Kanwal Raghav, MBBS, MD, presents the case of a 72-year-old woman with metastatic colorectal cancer and describes the first-line therapy options.

EP: 1 . Case Presentation: A 72-Year-Old Woman With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Ep: 2 . maintenance therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer, ep: 3 . metastatic colorectal cancer: regorafenib, ep: 4 . treatment sequencing in metastatic colorectal cancer.

Kanwal Raghav, MBBS, MD: Today we’ll be discussing a case of a 72-year-old woman with metastatic colorectal cancer. This patient presented with a 2-month history of bloating and abdominal discomfort. Her last colonoscopy was about 2 years ago and was negative, and she also had some unintentional weight loss. With regard to her past medical history, it’s significant only because of a hysterectomy done about 12 years ago and high blood pressure, which is controlled with lisinopril.

During the clinic work-up, the patient was found to be anemic with an elevated CEA [carcinoembryonic antigen] of 6 ng/mL. The colonoscopy revealed a 9-cm mass in the ascending colon; biopsy of this showed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The molecular profiling showed a microsatellite stable tumor, which was KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF wild type. CT scan showed widespread lesions spread across the liver. The patient was diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer, and the ECOG PS [performance status] of the patient was 1.

At that time, the patient was started on treatment with bevacizumab and FOLFOX [5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin]. The patient received about 4 months of this treatment with scans at 2- and 4-months showing response. This was followed by maintenance chemotherapy between May 2018 and June 2019. In June 2019, the patient had increasing symptoms of shortness of breath and fatigue, and scans showed disease progression in both the lungs and the liver. Patient was then switched to FOLFIRI [5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan] and cetuximab and received this treatment until August 2020 with stable disease as the best response. In August 2020, the patient had progressive disease and was given regorafenib.

Interestingly, it’s strange that the patient developed this disease in a rather short interval from the last colonoscopy, which was completely negative. We also want to notice that certain comorbidities can affect our treatment decisions in metastatic colorectal cancer, like high blood pressure, especially whether it’s controlled. In this case it was controlled. With regard to molecular profiling, this patient has had some focused testing around RAS and BRAF, but I would have done either a next-generation-sequencing panel or at least have status for HER2 amplification on expression, and also NTRK fusions, which are also targeted with subsets. It’s very clear that the patient has an unresectable disease, and therefore surgery is definitely not an option. That’s what we’re dealing with. Furthermore, the PS of the patient is 1, which has implications in how aggressive you can be with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Those are a couple of points that are noteworthy. It should also be remembered that the patient has a right-sided colon cancer because they have a 9-cm ascending mass lesion.

The first-line therapy options are usually a combination of cytotoxic chemotherapy with a biologic attached to them. In some cases, the first-line cytotoxic option is a triplet cytotoxic which is 5-FU [5-fluorouracil], oxaliplatin, and irinotecan or FOLFOXIRI [5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, irinotecan] with bevacizumab. This patient would not qualify for that. The TRIBE2 study that established the survival benefit of FOLFOXIRI [5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, irinotecan], which is triplet cytotoxic over doublets, allowed only patients with ECOG PS 0, especially if they were beyond ages of 70—so 71 to 75 patients, and all of them had to have ECOG PS0. Anything less than that, we could have a lower ECOG PS.

As far as this patient is concerned, a doublet cytotoxic is very reasonable. This was combined with a biologic that is anti-VEGF attached to bevacizumab, which is a common biologic. In some patients who are RAS, BRAF wild-type, HER2-negative, and left-sided colon cancer, there is also a possibility of using an anti-EGFR agent, such as cetuximab or panitumumab, up front because those are the patients that benefit most from this. Because this patient has a right-sided tumor, the choice of bevacizumab with FOLFOX [5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin] was a reasonable choice.

Transcript edited for clarity.

Case Overview: A 72-Year-Old Woman With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Initial presentation

A 72-year-old woman reported a 2-month history of bloating and abdominal cramping, and an 8-pound unintentional weight loss

Her last screening colonoscopy when she was 70 years of age was negative

PMH: hysterectomy at age 60, high blood pressure well controlled with lisinopril

Clinical workup

Labs: Hg 8.4 g/dL, CEA 6 ng/mL

Colonoscopy revealed a 9-cm mass in ascending colon

Pathology: invasive, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

Molecular testing: KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF wildtype; microsatellite stable

CT scan revealed widespread lesions in the liver

Diagnosis: Stage 4 colorectal cancer

ECOG PS is 1

The patient received systemic therapy with FOLFOX + bevacizumab for 6 cycles, which was well tolerated

Follow-up imaging at 2 months and 4 months showed response in liver lesions

The patient continued on bevacizumab maintenance

- The patient presents with shortness of breath and fatigue

- CT CAP shows two new lung lesions and growth of liver lesions

- The patient is switched to FOLFIRI and cetuximab

- Follow-up imaging showed stable disease in liver and lungs

August 2020

- The patient reports severe fatigue

- CT CAP shows progression in the lungs and new bony lesions

- The patient is given regorafenib alone

Colorectal Cancer: Leveraging Awareness and Early Detection

For Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, Jedrzej Wykretowicz, MD, PhD, discussed the importance of early detection and taking steps towards the prevention of colorectal cancer.

Behind the FDA Approval of Fruquintinib for Previously Treated mCRC

In season 4, episode 18 of Targeted Talks, Arvind Dasari, MD, MS, dives into the recent approval of fruquintinib for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Study Finds Susceptibility Gene Variations by Race/Ethnicity in Early-Onset CRC

In an interview with Targeted Oncology, Andreana N. Holowatyj, PhD, MSCI, discussed data from a study which found racial and ethnic differences in susceptibility genes for early-onset colorectal cancer, suggesting current multigene panel tests may not be accurate for diverse populations.

Special Episode: Insight on Targeting Rare Genomic Alterations in Colorectal Cancers

In season 2, episode 6 of Targeted Talks, Dr. Michael J. Overman, joins Targeted Oncology for a special discussion around rare genomic alterations in colorectal cancer

Translating Outcomes in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC)

In this companion article, Dr Tanios Bekaii-Saab provides insights into effective management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

CheckMate-8HW Meets Primary End Points With Nivolumab/Ipilimumab in mCRC

A dual primary end point of progression-free survival in the phase 3 CheckMate-8HW trial evaluating nivolumab and ipilimumab in metastatic colorectal cancer has been met.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS FEATURE

- 13 March 2024

Why are so many young people getting cancer? What the data say

- Heidi Ledford

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Illustration by Acapulco Studio

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Of the many young people whom Cathy Eng has treated for cancer, the person who stood out the most was a young woman with a 65-year-old’s disease. The 16-year-old had flown from China to Texas to receive treatment for a gastrointestinal cancer that typically occurs in older adults. Her parents had sold their house to fund her care, but it was already too late. “She had such advanced disease, there was not much that I could do,” says Eng, now an oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Eng specializes in adult cancers. And although the teenager, who she saw about a decade ago, was Eng’s youngest patient, she was hardly the only one to seem too young and healthy for the kind of cancer that she had.

Thousands of miles away, in Mumbai, India, surgeon George Barreto had been noticing the same thing. The observations quickly became personal, he says. Friends and family members were also developing improbable forms of cancer . “And then I made a mistake people should never do,” says Barreto, now at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. “I promised them I would get to the bottom of this.”

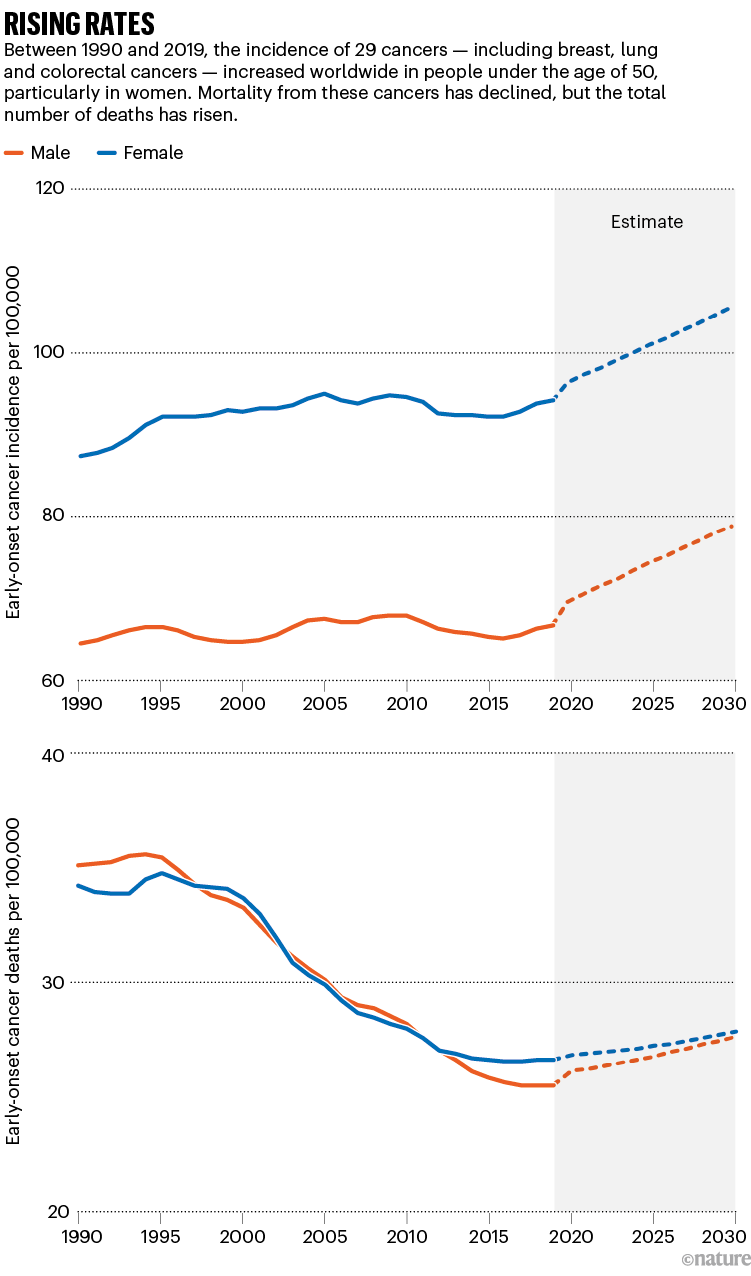

Almost half of cancer deaths are preventable

It took years to make headway on that promise, as oncologists such as Barreto and Eng gathered hard data. Statistics from around the world are now clear: the rates of more than a dozen cancers are increasing among adults under the age of 50. This rise varies from country to country and cancer to cancer , but models based on global data predict that the number of early-onset cancer cases will increase by around 30% between 2019 and 2030 1 . In the United States, colorectal cancer — which typically strikes men in their mid-60s or older — has become the leading cause of cancer death among men under 50 2 . In young women, it has become the second leading cause of cancer death.

As calls mount for better screening, awareness and treatments , investigators are scrambling to explain why rates are increasing. The most likely contributors — such as rising rates of obesity and early-cancer screening — do not fully account for the increase. Some are searching for answers in the gut microbiome or in the genomes of tumours themselves. But many think that the answers are still buried in studies that have tracked the lives and health of children born half a century ago. “If it had been a single smoking gun, our studies would have at least pointed to one factor,” says Sonia Kupfer, a gastroenterologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. “But it doesn’t seem to be that — it seems to be a combination of many different factors.”

On the increase

In some countries, including the United States, deaths owing to cancer are declining thanks to increased screening, decreasing rates of smoking and new treatment options. Globally, however, cancer is on the rise (see ‘Rising rates’). Early-onset cancers — often defined as those that occur in adults under the age of 50 — still account for only a fraction of the total cases, but the incidence rate has been growing. This rise, coupled with an increase in global population, means that the number of deaths from early-onset cancers has risen by nearly 28% between 1990 and 2019 worldwide. Models also suggest that mortality could climb 1 .

Source: Ref. 1

Often, these early-onset cancers affect the digestive system, with some of the sharpest increases in rates of colorectal, pancreatic and stomach cancer. Globally, colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers and tends to draw the most attention. But others — including breast and prostate cancers — are also on the rise.

In the United States, where data on cancer incidence is particularly rigorous, uterine cancer has increased by 2% each year since the mid-1990s among adults younger than 50 2 . Early-onset breast cancer increased by 3.8% per year between 2016 and 2019 3 .

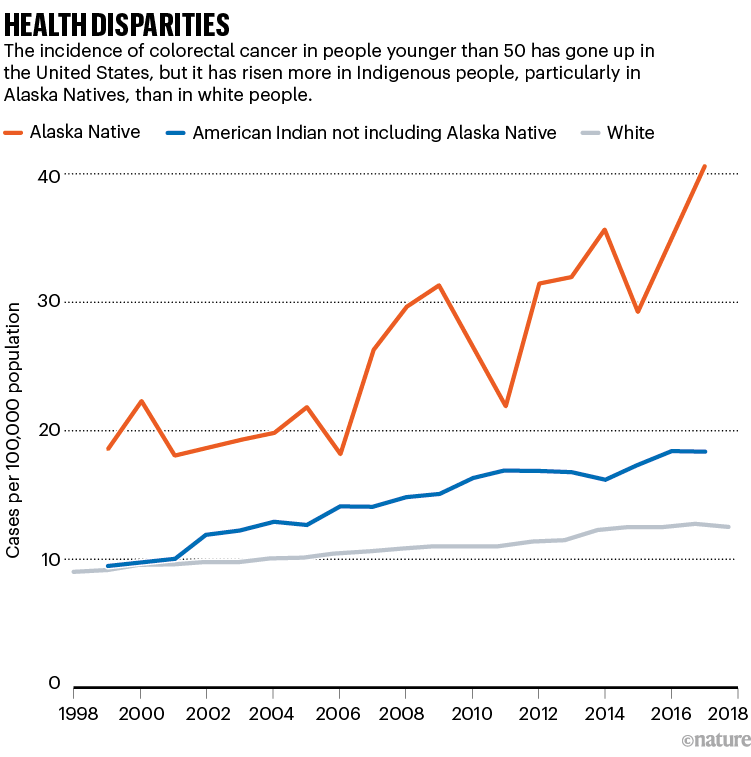

The rate of cancer among young adults in the United States has increased faster in women than in men, and in Hispanic people faster than in non-Hispanic white people. Colorectal cancer rates in young people are rising faster in American Indian and Alaska Native people than they are in white people (see ‘Health disparities’). And Black people with early onset colorectal cancer are more likely to be diagnosed younger and at a more advanced stage than are white people. “It is likely that social determinants of health are playing a role in early-onset cancer disparities,” says Kupfer. Such determinants include access to healthy foods, lifestyle factors and systemic racism .

Source: Ref. 4

Cancer’s shift to younger demographics has driven a push for earlier screening. Advocates have been promoting events targeted at the under 50s. And high-profile cases — such as the 2020 death of actor Chadwick Boseman from colon cancer at the age of 43 — have helped to raise awareness. In 2018, the American Cancer Society urged people to be screened for colorectal cancer starting at age 45, rather than the previous recommendation of 50.

In Alaska, health leaders serving Alaska Native people have been recommending even earlier screening — at age 40 — since 2013. But the barriers to screening are high; many communities are inaccessible by road, and some people have to charter a plane to reach a facility in which they can have a colonoscopy. “If the weather’s bad, you could be there a week,” says Diana Redwood, an epidemiologist at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium in Anchorage.

These efforts have paid off to some extent: screening rates in the community have more than doubled over the past three decades, and now exceed those of state residents who are not Alaska Natives. But mortality from colorectal cancer has not budged, says Redwood. Although colorectal cancer rates are falling in people over 50 years old, the age group that is still most likely to be screened, the rates in younger Alaska Native people are climbing by 5.2% each year 4 .

Genetic clues

The prominence of gastrointestinal cancers and the coincidence with dietary changes in many countries point to the rising rates of obesity and diets rich in processed foods as likely culprits in contributing to rising case rates. But statistical analyses suggest that these factors are not enough to explain the full picture, says Daniel Huang, a hepatologist at the National University of Singapore. “Many have hypothesized that things like obesity and alcohol consumption might explain some of our findings,” he says. “But it looks like you need a deeper dive into the data.”

Those analyses match the anecdotal experiences that clinicians described to Nature : often, the young people they treat were fit and seemingly healthy, with few cancer risk factors. One 32-year-old woman that Eng treated was preparing for a marathon. Previous physicians had dismissed the blood in her stool as irritable bowel syndrome caused by intense training. “She was healthy as can be,” says Eng. “If you looked at her, you would have no idea that more than half of her liver was tumour.”

US cancer deaths are falling — but not fast enough

Prominent cancer-research funders, including the US National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK, have supported programmes to find other contributors to early-onset cancer. One approach has been to look for genetic clues in early-onset tumours that might set them apart from tumours in older adults. Pathologist Shuji Ogino at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues have found some possible characteristics of aggressive tumours in early-onset cancers. For example, aggressive tumours are sometimes particularly adept at suppressing the body’s immune responses to cancer, and Ogino’s team has found signs of a muted immune response to some early-onset tumours 5 .

But these differences are subtle, he says, and researchers have yet to find a clear demarcation between early-onset and later-onset cancers. “It’s not dichotomous, but more like a continuum,” he says.

Researchers have also looked at the microorganisms that reside in the human body. Disruptions in microbiome composition, such as those caused by dietary changes or antibiotics, have been linked to inflammation and increased risk of several diseases, including some forms of cancer. Whether there is a link between the microbiome and early-onset cancers is still in question: results so far are still preliminary and it’s difficult to gather long-term data, says Christopher Lieu, an oncologist at the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora. “The list of things that impact the microbiome is so extensive,” he says. “You’re asking people to recall what they ate as kids, and I can barely remember what I ate for breakfast.”

Looking to the past

But increasing the size of studies could help. Eng is developing a project to look at possible correlations between microbiome composition and the onset of cancer at a young age, and she plans to combine her data with those from collaborators in Africa, Europe and South America. Because the number of early-onset cancer cases is still relatively small at any one centre, this kind of international coordination is important to give statistical analyses more power, says Kimmie Ng, founding director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Another approach is to scrutinize the differences between countries. For example, Japan and South Korea are located near one another and are similar economically. But early-onset colorectal cancer is increasing at a faster rate in South Korea than it is in Japan, says Tomotaka Ugai, a cancer epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School. Ugai and his collaborators hope to determine why.

How gut microbes are joining the fight against cancer

But data are scarce in some countries. In South Africa, cancer data are collected only from the 16% of the population that has medical insurance, says Boitumelo Ramasodi, regional director for Southern Africa at the Global Colon Cancer Association, a non-profit organization in Washington DC. Those who do not have insurance are not counted. And families rarely keep records of who has died of cancer, she says. For many Black people in the country, cancer is considered a white person’s disease; Ramasodi initially struggled to make sense of her own diagnosis of colorectal cancer at the age of 44. “Black people don’t get cancer,” she thought at the time. “I’m young, I’m Black, why do I have cancer?”

Ultimately, researchers will also have to look back in time for clues to understand rising early-onset cancers, says epidemiologist Barbara Cohn at the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California. Research has shown that cancers can arise many years after an exposure to a carcinogen, such as asbestos or cigarette smoke. “If the latent period is decades, then where do you look?” she says. “We believe that you need to look as early as possible in life to understand this.”

To do that, researchers will need 40–60 years of data, collected from thousands of people — enough to capture a sufficient number of early-onset cancers. Cohn directs an unusual repository of data and blood samples that have been collected from about 20,000 expectant mothers during pregnancy since 1959. Researchers have followed many of the original participants, and their children, since then.

Cohn and Caitlin Murphy, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, have already tried combing through the data to look for ties to early-onset cancers, and have found a possible association between early colorectal cancer and prenatal exposure to a particular synthetic form of progesterone, sometimes taken to prevent premature labour 6 . But the study must be repeated in other cohorts for investigators to be sure.

More informed

Finding studies that follow cohorts from the prenatal stage to adulthood is a challenge. The ideal study would enrol thousands of expectant mothers in several countries, collect data and samples of blood, saliva and urine, and then track them for decades, says Ogino. A team funded by Cancer Research UK, the US National Cancer Institute and others will analyse data from the United States, Mexico and several European countries, to look for environmental exposures and other possible influences on early-onset cancer risk. Murphy and Cohn also hope to incorporate data collected from fathers and are working with collaborators to analyse blood samples in search of more chemicals that offspring might have encountered in the womb.

Murphy expects the results to be complicated. “At first, I really believed that there was something unique about early-onset colorectal cancers compared to older adults, and a risk factor out there that explains everything,” she says. “The more time I’ve spent, the more it seems clear that there’s not just one particular thing, it’s a bunch of risk factors.”

Cruel fusion: What a young man’s death means for childhood cancer

For now, it’s important for physicians to share their data on early-onset cancers and to follow their patients even after they complete their therapy, to learn more about how best to treat them, says Irit Ben-Aharon, an oncologist at the Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, Israel. Cancer treatment in young people can be fraught: some cancer drugs can cause cardiovascular problems or even secondary cancers years after treatment — a risk that becomes more concerning in a young person, she says.

Young adults might also be pregnant at the time of diagnosis, or more concerned about the impact of cancer drugs on their fertility than are people who are past their reproductive years. And they are less likely to be retired, and more likely to be concerned about whether their cancer treatment will cause long-term cognitive damage that could hinder their ability to work.

When Candace Henley was diagnosed with colorectal cancer at the age of 35, she was a single mother raising five children. The aggressive surgery she received rendered her unable to continue in her job as a bus driver, and the family was soon homeless. “I didn’t know what questions to ask and so the decisions around treatment were made for me,” says Henley, who went on to found The Blue Hat Foundation for Colorectal Cancer Awareness in Chicago, Illinois. “No one unfortunately considered what my needs were at home.”

In the years since Eng first noticed how young her patients were, certain things have changed. Some advocacy groups have begun targeting their information campaigns at younger audiences. People with early-onset cancers are more informed now and seek out second opinions when physicians dismiss their symptoms, Eng says. This could mean that physicians will more often catch early-onset cancers before they have spread and become more difficult to treat.

But Barreto still doesn’t have all the answers he promised. He wants to study the impact of prenatal stresses, such as exposure to alcohol and cigarette smoke or malnourishment, on early-cancer risk. He’s contacted scientists around the world, but no biobanking projects contain the data and samples that he requires.

If all of the data he and others need aren’t available now, it’s understandable, he says. “We never saw this coming. But in 20 years if we don’t have databases to record this, it’s our failure. It’s negligence.”

Nature 627 , 258-260 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00720-6

Zhao, J. et al. BMJ Oncol. 2 , e000049 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Siegel, R. L, Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 , 12–49 (2024).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Xu, S. et al. JAMA Netw. Open 7 , e2353331 (2024).

Kratzer, T. B. et al. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73 , 120–146 (2023).

Ugai, T. et al. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 71 , 933–942 (2022).

Murphy, C. C., Cirillo, P. M., Krigbaum, N. Y. & Cohn, B. J . Endocr. Soc. 5 , A496–A497 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Epidemiology

- Medical research

Cutting-edge CAR-T cancer therapy is now made in India — at one-tenth the cost

News 21 MAR 24

‘Woah, this is affecting me’: why I’m fighting racial inequality in prostate-cancer research

Career Q&A 20 MAR 24

Whittling down the bacterial subspecies that might drive colon cancer

News & Views 20 MAR 24

Fungal diseases are spreading undetected

Outlook 14 MAR 24

Massive public-health experiment sends vaccination rates soaring

News 13 MAR 24

Meningitis could be behind ‘mystery illness’ reports in Nigeria

News 05 MAR 24

Pregnancy advances your ‘biological’ age — but giving birth turns it back

News 22 MAR 24

First pig kidney transplant in a person: what it means for the future

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Warmly Welcomes Talents Abroad

“Qiushi” Distinguished Scholar, Zhejiang University, including Professor and Physician

No. 3, Qingchun East Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate

Our laboratory at the Washington University in St. Louis is seeking a postdoctoral experimental biologist to study urogenital diseases and cancer.

Saint Louis, Missouri

Washington University School of Medicine Department of Medicine

Recruitment of Global Talent at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

The Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is seeking global talents around the world.

Beijing, China

Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

Postdoctoral Fellow-Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry

Location: Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA Department: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Tulane University School of Med...

New Orleans, Louisiana

Tulane University School of Medicine (SOM)

Open Faculty Position in Mathematical and Information Security

We are now seeking outstanding candidates in all areas of mathematics and information security.

Dongguan, Guangdong, China

GREAT BAY INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY: Institute of Mathematical and Information Security

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, an overview of case reports and case series of pulmonary actinomycosis mimicking lung cancer: a scoping review.

- Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Pulmonary actinomycosis (PA) is a rare type of Actinomyces infection that can be challenging to diagnose since it often mimics lung cancer.

Methods: Published case reports and case series of PA in patients with suspicion of lung cancer were considered, and data were extracted by a structured search through PubMed/Medline.

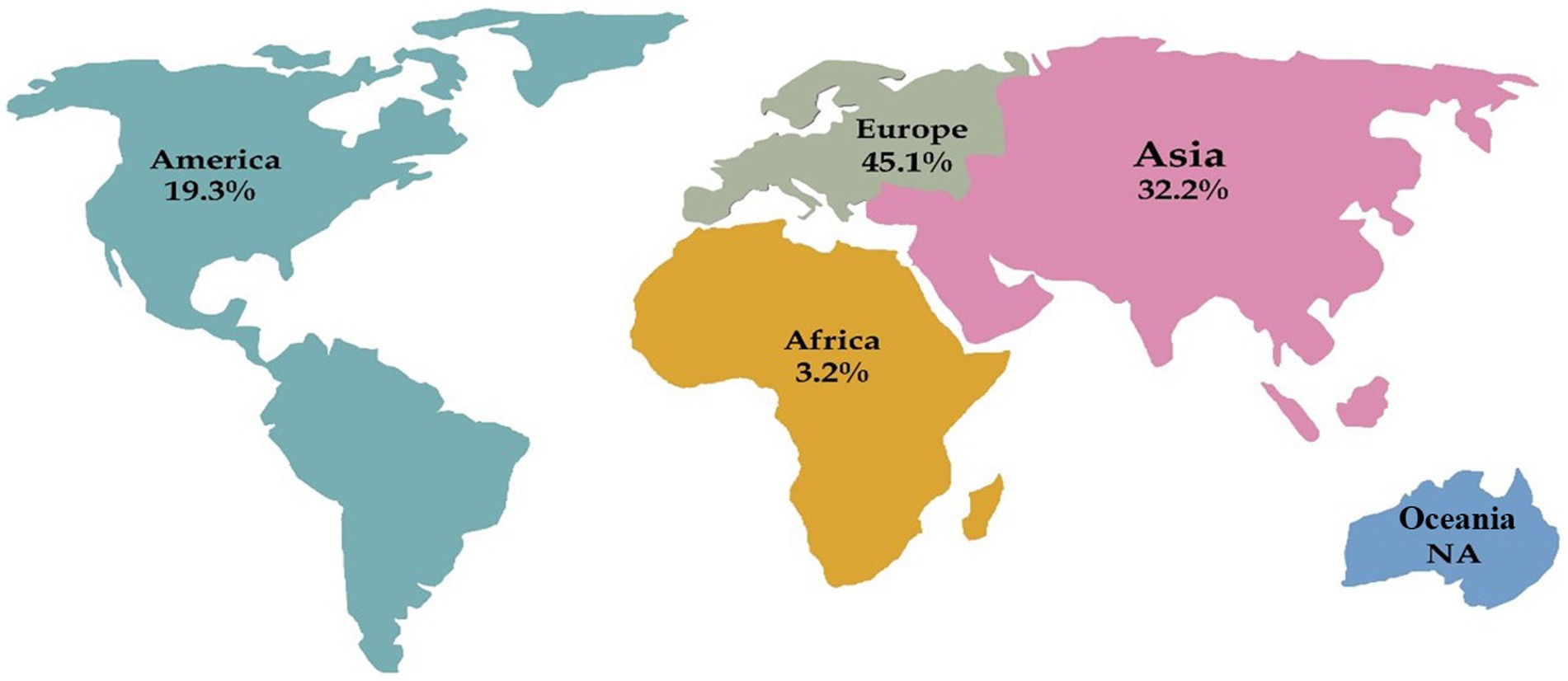

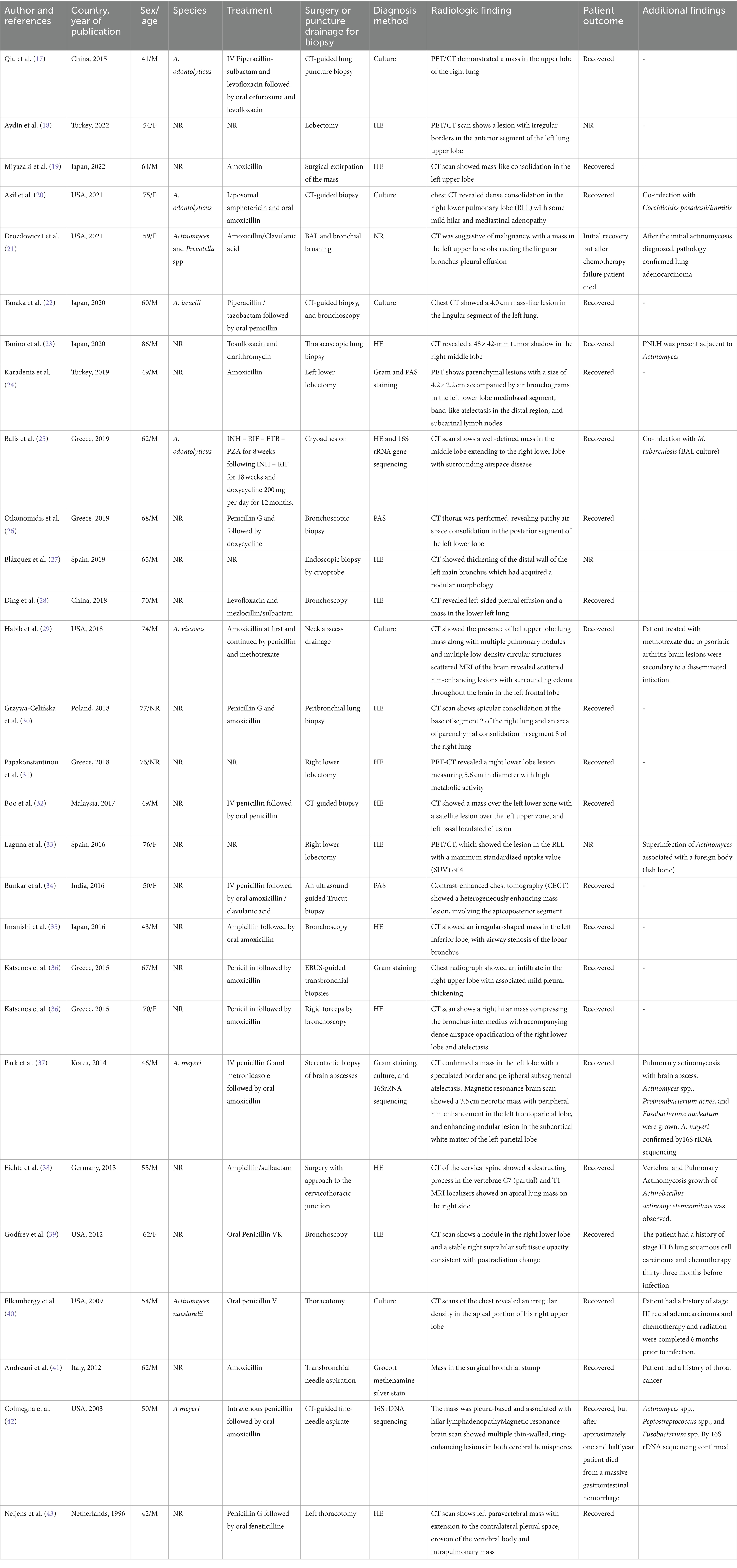

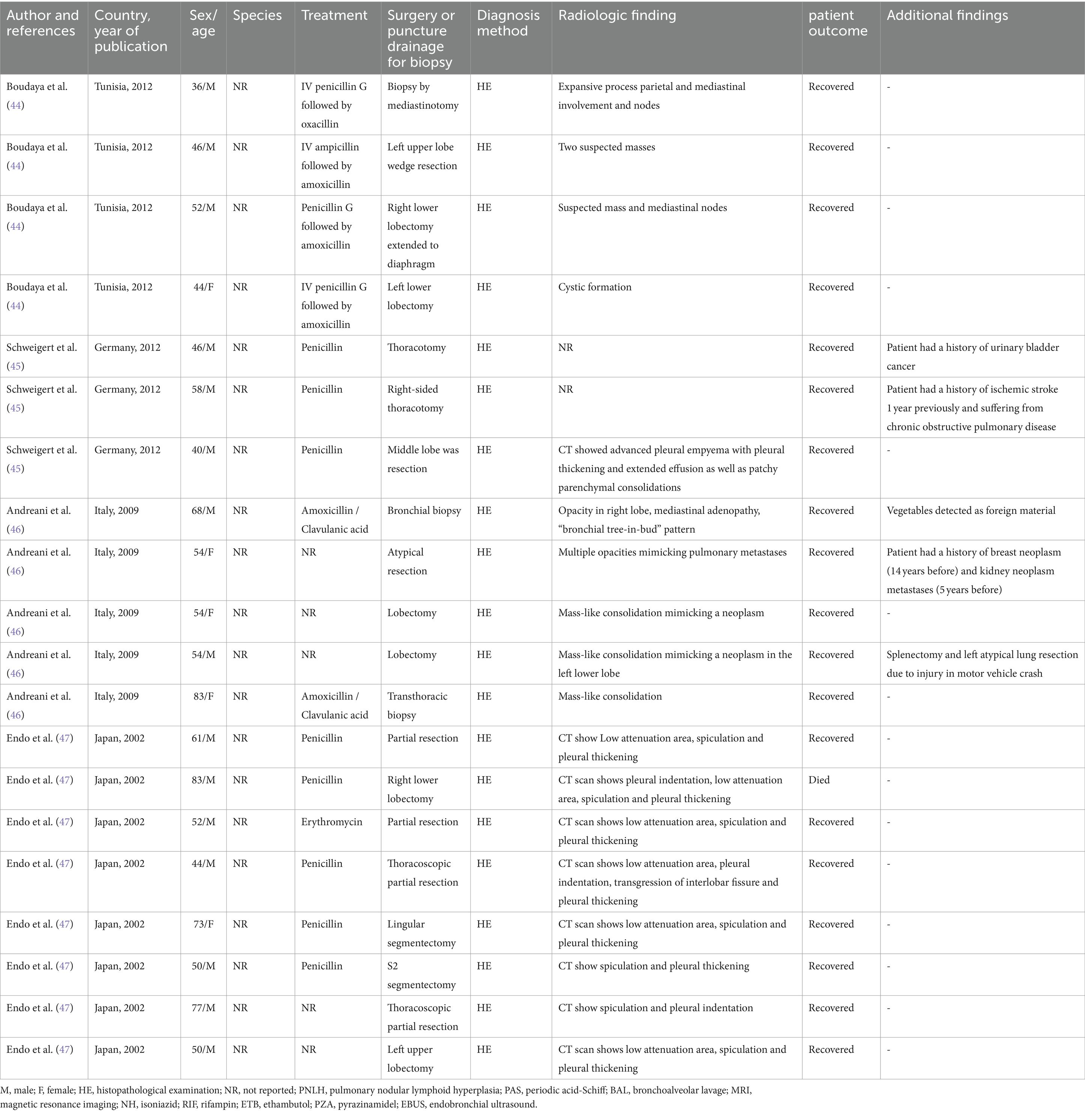

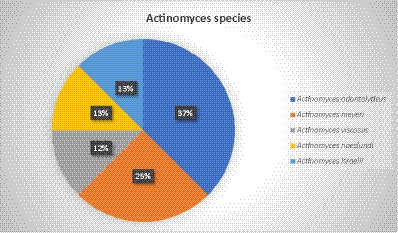

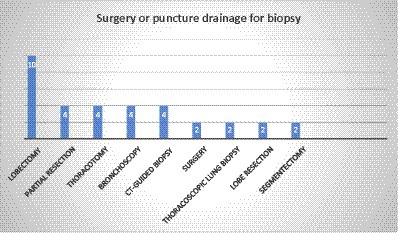

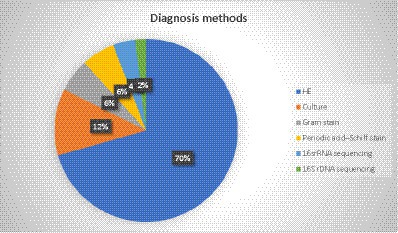

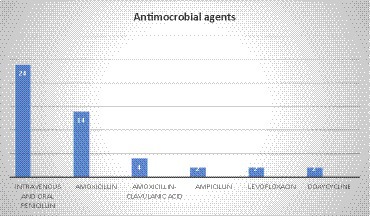

Results: After analyzing Medline, 31 studies were reviewed, from which 48 cases were extracted. Europe had the highest prevalence of reported cases with 45.1%, followed by Asia (32.2%), America (19.3%), and Africa (3.2%). The average age of patients was 58.9 years, and 75% of all patients were above 50 years old. Male patients (70%) were predominantly affected by PA. The overall mortality rate was 6.25%. In only eight cases, the causative agent was reported, and Actinomyces odontolyticus was the most common isolated pathogen with three cases. Based on histopathological examination, 75% of the cases were diagnosed, and the lobectomy was performed in 10 cases, the most common surgical intervention. In 50% of the cases, the selective antibiotics were intravenous and oral penicillin, followed by amoxicillin (29.1%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin, levofloxacin, and doxycycline.

Conclusion: The non-specific symptoms resemble lung cancer, leading to confusion between PA and cancer in imaging scans. Radiological techniques are helpful but have limitations that can lead to unnecessary surgeries when confusing PA with lung cancer. Therefore, it is important to raise awareness about the signs and symptoms of PA and lung cancer to prevent undesirable complications and ensure appropriate treatment measures are taken.

Introduction