- 0 Shopping Cart

Counter-urbanisation

Counter-urbanisation is the movement of people out of cities, to the surrounding areas. Since 1950 this process has been occurring in HICs (high-income countries). There are four main reasons for counter-urbanisation :

1. The increase in car ownership over the last 40 years means people are more mobile. This has led to an increase in commuting. Also, the growth in information technology (E-mail and video conferencing) means more people can work from home.

2. Urban areas are becoming an increasingly unpleasant place to live. This is the result of pollution, crime and traffic congestion .

3. More people tend to move when they retire.

4. New business parks on the edge of cities (on greenfield sites) mean people no longer have to travel to the city centre. People now prefer to live on the outskirts of the city to be near where they work.

Latest Blog Entries

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

Previous Topic Page

Topic home, next topic page, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Please Support Internet Geography

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Did the pandemic bring new features to counter-urbanisation? Evidence from Estonia

Tiit tammaru.

a University of Tartu, Department of Geography, Estonia

c Estonian Academy of Sciences, Estonia

Jaak Kliimask

b Estonian University of Life Sciences, Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonia

Jānis Zālīte

Associated data.

The authors do not have permission to share data.

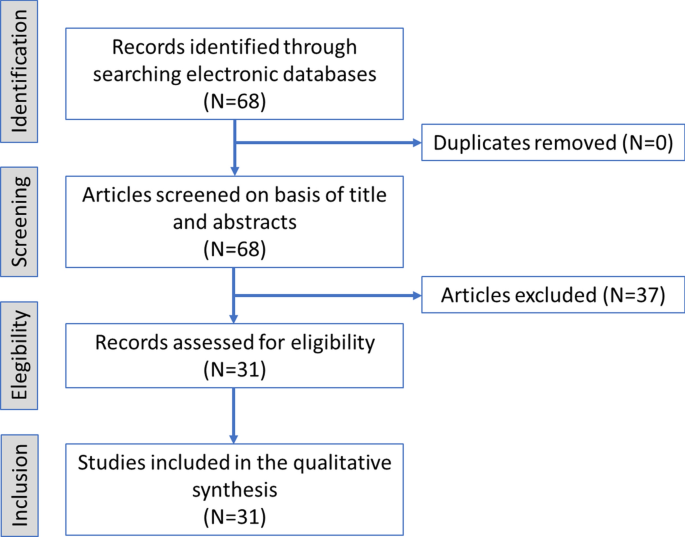

This paper aims to shed new light on changes in counter-urbanisation over the past three decades. A specific focus will be placed on new features of domestic migration to non-metropolitan rural areas which have become apparent during the global coronavirus pandemic. We focus on the intensity, origins, and destinations of counter-urban moves, and on the individual characteristics of counter-urban movers. Based on a case study of Estonia, our main findings show, firstly, that urbanisation has been the predominant migration trend across the past thirty years, with the main destination of domestic migrants being the capital city and its urban region. Secondly, we find that counter-urban moves have gained importance over time and especially during the periods of economic bust. The most important new features of counter-urbanisation during the pandemic relate to the increased migration of families with children and people who have high-income occupations to non-metropolitan rural areas. These new features of domestic migration could serve to slow down or even reverse the long-term problem of population aging in the countryside and the loss of educated people there.

1. Introduction

The global coronavirus pandemic has generated renewed interest in counter-urbanisation ( Klocker et al., 2021 ; McManus, 2022 ). An urban exodus has been detected during the periods of pandemic-induced lockdowns, as people temporarily move out to the countryside to reduce their risk of becoming infected ( Willberg et al., 2021 ). However, it is less clear what changes in domestic migration patterns will emerge in the longer run. Would the urban exodus remain a temporary phenomenon? Would the pandemic bring with it an increased level of attraction when it comes to having second homes in rural areas, along with the related spread of the multi-local life-style amongst urban residents ( Greinke and Lange, 2022 ), or a strengthening of counter-urban migration as more people seek a home in the countryside ( McManus, 2022 )? A parallel discussion revolves around changes in the geography of working life as the opportunities to work from home have improved, potentially reducing the need to live in cities among some occupational groups.

The aim of this paper is to shed new light on counter-urbanisation during the pandemic, and whether we can uncover any new features of demographic and socio-economic change in the countryside. In order to better capture changes in domestic migration, we will compare pandemic-period migration against long-term trends of urbanisation and counter-urbanisation over the thirty-year period that includes different periods of economic boom and bust. We define counter-urban migration as any move from higher levels of the settlement system to lower levels of the settlement system. We are particularly interested in moves to non-metropolitan rural areas (cf. Berry, 1976 ; Fielding, 1989 ; Mitchell, 2004 ; McManus, 2022 ). The most common explanations for counter-urbanisation refer to economic hardships in the cities ( Berry, 1976 ) and increased preference for a rural lifestyle ( Halfacree, 2008 ). The e-lifestyle of the digital era could further contribute to lifestyle-based migration to the countryside ( McManus, 2022 ). These drivers reveal a certain tension between necessity-driven motives and motives which can be related to a desire for a more pleasant living environment. Qualitative studies aim to shed light on such motives by carrying out in-depth interviews with counter-urban movers using a case study approach ( Gkartzios, 2013 ). Quantitative studies focus on the individual characteristics and destinations of the counter-urban movers, based on census and register data, in order to trace any new features in domestic migration ( McManus, 2022 ). This study takes a quantitative approach when it comes to tracing potential changes in domestic migration during the past three decades, with the goal being to discover new features in counter-urbanisation during the pandemic. More specifically, we seek answers to the following research questions:

- (a) What changes have there been in the intensity of migration within the settlement system during the past three decades that includes different periods of economic boom and bust?

- (b) How has the balance changed between urban and counter-urban migration during the various periods of economic boom and bust over the past three decades?

- (c) What new features have become apparent in migration to non-metropolitan rural areas during the pandemic when compared to earlier periods of economic boom and bust?

Data for the study comes from Estonia, a country which has undergone major social transformation in the past three decades. Our study is based on individual-level census and registration data, with people being linked across censuses. Such individual-level linked database makes it possible for us to provide in-depth insights into the long-term changes in domestic migration, and how the counter-urbanisation has changed with time and between the population groups. In the empirical sections of the paper we will analyse migration intensity in the settlement system, and will calculate the migration concentration index and net migration rates, both for the different levels of the settlement system as well as for the smallest spatial planning units. In addition to analysing migration levels in the total population, we will also calculate all of the measures by selected population groups in terms of age, gender, mother tongue, level of education, and occupation. Our main interest relates to the changes in the domestic migration of families and occupational groups in order to uncover new features of counter-urbanisation and how such new features may relate to demographic and socio-economic changes in non-metropolitan rural areas. The paper ends with a summary and discussion of the main findings.

1.1. Literature review: changing patterns and explanations for counter-urbanisation

Counter-urbanisation as a form of migration within the settlement system serves to characterise moves down the urban hierarchy ( Klocker et al., 2021 ; McManus, 2022 ). A rich body of research has emerged on counter-urbanisation that deals with origins, destination and individual characteristics of counter-urban movers ( Mitchell 2004 , 2019 ). Counter-urbanisation may be triggered both by domestic migration as well as by people arriving from abroad (see, for example, Eimermann et al., 2012 ; Hedberg and Haandrikman, 2014 ). The term micropolitan centres has been introduced in order to refer to the diversity of settlements of different sizes and locations in the counter-urbanisation process, as counter-urban movers seek out a level of balance between urban and rural amenities ( Bjarnason et al., 2021 ; Vias, 2012 ).

In this paper, we focus on counter-urban moves as related to domestic migration from higher levels of the settlement system to lower levels of the settlement system, with a particular focus on migration into non-metropolitan rural areas. We also use the terms ‘rural areas’ and ‘countryside’ in order to refer to non-metropolitan rural areas to diversify language use within this paper. Five key drivers have been identified in moves to non-metropolitan rural areas: a) aspiration towards a rural lifestyle; b) environmental considerations; c) housing-related motives; d) economic considerations; and most recently e) health-triggered motives within the context of the global spread of COVID-19 in recent years ( Halfacree, 2008 ; McManus, 2022 ; Mitchell, 2004 , 2019 ). Geyer and Kontuly (1993) argue that preferences towards a rural lifestyle, along with environmental and housing-related motives, form a group of environmental motives which are mainly responsible for counter-urban migration. Halfacree (2008) further argues that people searching for a rural lifestyle or the ‘rural idyll’ are the most typical counter-urban movers. The desire towards a less stressful rural lifestyle tends to increase alongside the progression of the life course ( Jauhiainen, 2009 ). It has been found, for example, that the pre-elderly and elderly population in England share retirement-related quality of life considerations as an impetus for counter-urban migration ( Stockdale, 2006 ). In the Nofsinger (2012) have detected pleasant physical environment as playing the most significant role in choosing to move to the countryside. Similarly, Šimon (2014) claims that a pleasant rural environment and lifestyle-orientated motives predominate over economic reasons when it comes to the counter-urbanisation within the Czech Republic.

While environmental reasons are often found to be the main trigger for counter-urban migration, Berry (1976) introduced the term ‘counter-urbanisation’ by noting that the global oil crises of the early 1970s, which hit the cities particularly hard, was crucial in reversing the long-term trend towards urbanisation in developed countries. Similarly ( Tammaru, 2003 ), found that counter-urbanisation took the form of a survival strategy for urban households where jobs had been lost or where householders had suffered from a lowering of their income during the large-scale social transformations of the 1990s in Estonia, as the country transformed from a central planning economy to a market economy. The study by Gkartzios (2013) reveals that the main narrative in Greece relates to ‘crisis counter-urbanisation’ which has largely been triggered by the high levels of unemployment in cities rather than by pro-rural motivations and idyllic constructions of rural life. Hence, economic cycles in general and the economic hardship being experienced in urban households in particular may affect the intensity of urbanisation and counter-urbanisation; a dynamic labour and housing market during economic booms tend to attract people to move into the cities, while the push factors which encourage people to move away from those cities may tend to gain a level of importance at times of economic bust.

A tightly related discussion revolves around the social, occupational, or income groups which contribute to counter-urbanisation ( Šimon, 2014 ; Sandow and Lundholm, 2020 ). Necessity-driven counter-urban moves tend to be related to more vulnerable population groups. For example, house price growth in cities makes housing less affordable for low-income families and medium-income households, pushing families which may be in need of more spacious homes out from urban housing markets ( Hochstenbach and Musterd, 2018 ; Karsten, 2020 ). Likewise, jobs which are suitable for lower-skilled workers are also being relocated away from city centres towards more affordable suburban locations ( Delmelle et al., 2021 ). These suburban jobs can be reached not only by local inhabitants but also by travelling from more distant locations which are outside metropolitan areas, especially when these jobs are located close to easily-accessible transportation junctions, thereby reducing the need for urban living.

People from higher-income households may be more likely to be amenity-seekers in the countryside. However, while the gentrification of the creative class is well documented in cities around the globe ( Atkinson and Bridge, 2005 ; Van Ham et al., 2021 ), what is less clear is how big of a role is being played by higher income households and rural gentrification within the process of counter-urbanisation ( Phillips, 1993 ; 2004 ; Phillips et al., 2022 ). For example, the study by Herslund (2012) in Denmark documented the migration of well-educated urban dwellers to less stressful rural environs so that they could start their own business there. A recent study in Sweden also provides evidence that people who are working in the public sector and in creative industries within the knowledge economy do tend to move to non-metropolitan rural areas ( Sandow and Lundholm 2020 ). Phillips et al. (2022) find that diverse groups of gentrifiers are moving to rural England, including creative, technical, and welfare professionals. However, the study by Kozina and Clifton (2019) within the Slovenian context reveals that members of the creative class are clearly under-represented in the more peripheral non-metropolitan areas, while being over-represented in the cities. Sandow and Lundholm (2020) further detect that working in the knowledge economy does not significantly increase the chances of becoming a counter-urban mover, with such movers more likely being lower-income families. Similar evidence can be found in other contexts. In Australia, counter-urbanisation is more common amongst lower-income socio-economic groups ( Hugo and Bell, 1998 ; Argent and Plummer, 2022 ). In the Czech Republic it has been found that experience of salary decline tends to elevate the probability that those who are suffering such a decline will undertake a counter-urban move ( Šimon, 2014 ). In other words, while some well-educated and higher-income families, and members of the creative class do opt for rural living, they are not necessarily over-represented amongst those occupational groups which contribute to counter-urban migration.

The effects of the coronavirus pandemic upon counter-urbanisation are less clear in the existing body of research which is only just about beginning to emerge. The most important lasting effects of the pandemic in terms of migration to non-metropolitan areas may stem from improved opportunities of working from home ( Phillipson et al., 2020 ). Since opportunities to switch to telecommuting differ between occupational groups, there is a further expectation that white-collar office workers have more flexibility in residential choice and distant working when compared to blue-collar workers. Based on data from the United States, Dingel and Neiman (2020) have found that more than one third of jobs can be carried out entirely from home. These jobs mainly include higher-paying jobs such as those at a managerial level, as well as people who are working in the IT or financial sectors. However, teleworking also requires high-quality internet connections, both in terms of the speed of such connections (including upload speeds) and in terms of connection stability ( Budnitz and Tranos, 2021 ). Internet quality levels in rural areas tends to lag behind quality levels in major cities, thereby limiting opportunities for telecommuting outside of metropolitan areas, despite the improvement of software solutions and skills. The daily logistics of families with school-age children may be also challenging in the countryside, where public and sustainable transportation options are less readily available when compared to those of metropolitan areas ( Tao et al., 2019 ).

To conclude, previous research provides diverse and sometimes contrasting views on counter-urban migration, both when it comes to the temporal dynamics during times of economic growth and decline, and in relation to the population groups which are involved in such processes (see also Rowe et al., 2019 ). An important debate revolves around occupational differences when it comes to the characteristics of counter-urbanisers. Working from home allows for preference-based moves to non-metropolitan areas by high-income households, while high house prices in cities could push lower-income families to seek affordable housing outside the metropolitan areas. It may also be the case that, even if differences in counter-urbanisation do not vary between population groups, their destinations may differ due to the fact that high-income households look for rural amenities, while low-income households look for areas with more affordable housing. Based on the case study of Estonia, we will seek to shed more light on the potential new features of counter-urbanisation.

1.2. Material and methods

1.2.1. estonian context.

Information for the current study originates in Estonia. This country was part of the Soviet Union between 1944 and 1991, regaining its independence in 1991 and joining the European Union in 2004. With its 1.3 million inhabitants and a population density of 29.4 people per square kilometre, Estonia is both one of the smallest and the most sparsely-populated member state of the European Union. In administrative terms, the country is divided into seventy nine municipalities and fifteen counties ( Fig. 1 ). County seats and their surrounding municipalities form the urban regions of Estonia. Tallinn, Jõhvi, Tartu and Pärnu act as regional centres for north-west, north-east, south-east and south-west Estonia. The capital city of Tallinn with its 450,000 inhabitants is by far the biggest of these four cities and, therefore, the Estonian settlement system could be considered to be monocentric ( Sooväli-Sepping and Roose, 2020 ). Saaremaa, Hiiumaa, Läänemaa, south-eastern Pärnumaa, and northern Lääne-Virumaa are Estonia's most attractive coastal regions. The coastline was densely populated by Soviet military forces between 1944 and 1991, but has become increasingly residential over the past three decades. Raplamaa, north-eastern Pärnumaa, Viljandimaa, Järvamaa, Jõgevamaa, and southern Lääne-Virumaa are mainly flat agricultural areas which lie in central Estonia. Ida-Virumaa is a traditional oil-shale mining-based industrial county which borders Russia. The county has become attractive for tourism during the past three decades. The county centre of Tartumaa is Tartu, which is the country's second-largest city and the main university town, hosting University of Tartu. Põlvamaa, Valgamaa, and Võrumaa form a hilly cluster of counties in south-eastern Estonia with many tourist attractions.

Estonia's main geographical units.

The country's domestic migration flows can be better understood by comparing them with migration flows in the centrally-planned past, or when Estonia was part of the Soviet Union ( Palang, 2010 ). Only a third of the country's population lived in cities prior to 1944. The urban population grew rapidly during the Soviet period, and the share of people living in the cities reached seventy-one percent of the total population by the time of the 1989 census. However, this urban expansion occurred mainly due to the inwards-migration of Russian-speaking industrial workers from Russia or the other then Soviet republics ( Tammaru et al., 2004 ). Migrants settled mostly Tallinn and in the industrial cities of Ida-Virumaa. Due to the inefficiency of the centrally-planned economy, a large part of the labour force had to work in agriculture and, therefore rural-to-urban migration was modest in Estonia like in most of Europe's centrally-planned countries (cf. Kornai, 1992 ). Moreover, urban-to-rural migration turnaround took place in Estonia in the 1980s. As food shortages grew in the former Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s, agriculture became increasingly important. Large agricultural production units (called kolhoos and sovhoos ) received greater degrees of resources from the central planners, which allowed them to attract young families to live in the countryside with high wages and opportunities to get a house for free ( Marksoo, 1995 ). The most important areas of agricultural production were in the central parts of Estonia with its flat landscapes and fertile soils.

Estonia regained independence in 1991, and the rural social and economic transformations which followed that in the 1990s completely changed the rural way of life, eroding its Soviet-era agricultural base. The large and inefficient agricultural productions units collapsed, leading to high levels of unemployment, loss of solidarity, and also the loss of hope in a bright future in the countryside ( Annist, 2017 ). New, more attractive jobs emerged in the urban service sector, especially in the capital city of Tallinn, which triggered a rural exodus of young people ( Tammaru et al., 2004 ). Likewise, the attraction of different geographic areas changed within the countryside. The central Estonian counties suffered most from the collapse of the big agricultural production units. The departure of Soviet troops from the islands and the coastal regions brought along post-productionist changes in rural areas, attracting urbanites who were looking for the combination of rural idyll and an urban way of life (cf. Argent et al., 2007 ; Phillips et al., 2022 ).

1.2.2. Data, definitions, and units of analysis

This paper takes a long view to domestic migration in order to better understand the new features of counter-urbanisation during the global coronavirus pandemic. We will focus on the intensity, destinations and individual characteristics of counter-urban movers. Following the classic ( Fielding, 1989 ; Champion, 1999 ; Geyer and Kontuly, 1993 ) as well as the more recent ( Bjarnason et al., 2021 ; Vias, 2012 ) studies, we define counter-urbanisation as moves from higher levels of a settlement system to the lower levels of a settlement system. We distinguish between five levels of the settlement system: the Tallinn capital city urban region; regional-centre urban regions; country-seat urban regions; small towns outside urban regions; and rural areas outside urban regions. Our main focus is on moves which take place towards non-metropolitan rural areas.

Our study covers the period between 1989 and 2021. Estonia was modestly urbanised in 1989, but since then it has undergone a rapid population concentration to higher levels of the settlement system, with the mainstream flow of domestic migrants targeting the capital city's urban region ( Kontuly and Tammaru, 2006 ). However, counter-urbanisation has also been important. In this paper we will focus on changes in domestic migration over four time-intervals. These intervals include the 1989–2000 and 2000–2011 inter-census periods, as well as periods between 2011 and 2014, 2015–2019, and 2020. The year 2020 represents the first year of the global coronavirus pandemic. We are interested in whether it is possible to identify any changes in domestic migration in 2020 compared to earlier time intervals, and especially compared to earlier periods of economic bust (1989–2000 and 2011–2014).

Our study is based on individual-level census data (for the years 1989, 2000, and 2011), and on individual level register data (for 2015 and 2020). More specifically, we use the harmonised data of the Estonian Infotechnological Observatory (2022) , which was developed by the three main Estonian universities together with Statistics Estonia. We link people who were living in Estonia in two consecutive census years in order to be able to study domestic migration in each inter-census period through individual identification codes. For example, when studying migration flows during the 1989–2000 inter-census period, we connect people who lived in Estonia during both of these census dates, and we compare any change in the place of residence for each person in the 2000 census relative to the 1989 census. A person who relocated to another municipality between the census years is defined as a domestic migrant. Our study has some limitations though. Although we are able to capture the residential changes of all of those people who are present at both census dates, our approach still misses some migratory movement. Firstly, we miss any moves by those who were either born or who died during the inter-census period. Secondly, we miss people who either emigrated from or immigrated into Estonia during the inter-census period. Thirdly, we miss out on multiple residential relocations by the same person during the inter-census period.

Any study which aims to uncover patterns of domestic migration over time has to deal with changes in administrative borders; there have been extensive changes between 1989 and 2021 in terms of Estonian municipality borders. In order to be able to achieve comparability over time, our data preparation included an extensive multi-year geocoding exercise (at the level of individual house addresses), which makes it possible for us to flexibly aggregate data into desired spatial units. The main spatial unit of analysis is the municipality, based on 2011 municipality borders which best reflect the nature of the Estonian settlement system. The main feature of administrative changes in Estonia has been the aggregating of municipalities into bigger units. We apply the 2011 administrative division to each census date, since the pre-2011 administrative divisions were characterised with very small municipalities, while post-2011 municipalities are too big to make it possible to effectively distinguish between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas.

We aggregate municipalities into urban regions based on daily commuting. Urban regions consist of county seats together with surrounding municipalities that send at least thirty percent of their workers to work in this county seat (see Fig. 1 ). Non-metropolitan small towns are small but compact settlements outside urban regions, and non-metropolitan rural areas include sparsely populated regions outside urban regions. We will also undertake a more detailed study of the geography of counter-urban moves. For this purpose, we aggregate the geocoded census data into the smallest Estonian planning units, or kants or localities (cf. Drudy, 1978 ). We overlay locality maps with the borders of fifteen Estonian counties and four regional centres (Tallinn, Tartu, Pärnu, and Jõhvi) in order to provide points of reference when discussing the geographic diversity of the destinations of counter-urban movers.

1.2.3. Study methods

We start our analysis by calculating ‘Migration Intensity’ (MI) in the settlement system to be able to understand temporal changes in domestic migration. Migration intensity shows the number of moves which occurred for each thousand inhabitants between the five levels of the settlement system. We proceed with the ‘Migration Concentration Index’ (MCI) analysis which was developed by Kontuly and Tammaru (2006) . MCI measures the balance between upwards and downwards moves within the settlement system between pairs of system levels. In our five-level settlement system, four moves can be made upwards and four moves can be made downwards within the system. The four upwards moves include moves from: a) non-metropolitan rural areas to non-metropolitan small towns; b) from non-metropolitan small towns to county seat metropolitan areas; c) from county seat metropolitan areas to regional city metropolitan areas; and d) from regional city metropolitan areas to capital city metropolitan areas. Downwards moves within the settlement system are the opposites to upwards moves. The MCI values are expressed in terms of percentages, varying from zero to a hundred. A value of zero implies that all moves take place from lower-to-higher levels of the settlement system. A value of a hundred implies that all moves take place from higher-to-lower levels of the settlement system. If the MCI values are higher than fifty this will imply that more than half of moves are upwards within the settlement system, and urbanisation is taking place. If the MCI values are less than fifty then this would imply that less than half of moves are downwards within the settlement system, and counter-urbanisation is taking place. Finally, we will calculate the ‘Net Migration Rate’ (NMR) within the settlement system which expresses the number of moves between the levels of the settlement system for each thousand inhabitants. We also calculate the NMR for localities, and visualise them in a series of maps. The three indices are calculated by using the following formulas:

where IM refers to in-migration, OM to out-migration, UM to upward moves, DM to downward moves and P to population size.

The time periods available for this study depend on the years in which the censuses were taken and therefore vary in length (1989–2000, 2000–2011, 2011–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2021). In order to enhance comparability over time, we standardised the values of all three indices by taking into account the length of each period in terms of years. The indices for the periods 1989–2000 and 2000–2011 are therefore divided by eleven in order to reflect the length of the inter-census periods in terms of years. The indices for the 2011–2014 period are divided by three, for the 2015–2019 period by four, and for the 2020–2021 period by one. In other words, we communicate per annum values of all indices in each time period within the empirical part of the paper. All three indices are calculated for the total population of Estonia as well as for selected population groups by gender, age, mother tongue, education, and occupation. We use the three main categories for measuring the level of education: primary, secondary, and tertiary. We also distinguish between three occupational groups which are aggregated from the nine main ISCO-89 categories. Highly-skilled occupations include managers and professionals, while low-skilled occupations include unskilled workers, and all other occupations are defined as being medium-skilled. Both level of education and occupation, as well as age, are time-varying personal characteristics, and we measure all of those characteristics at the beginning of each inter-census period or prior to an individual making their move.

We also present the NMR maps for highly-skilled occupations and low-skilled occupations by localities in order to detect differences in destinations for counter-urban movers. The islands and coastal areas form the most attractive rural destinations, while the agricultural areas in central Estonia provide less desirable rural destinations. The limitation in our study relates to a lack of knowledge in terms of migration-related motives. We interpret moves to islands and coastal areas as being driven mainly by amenity-related motives, and moves to central areas of Estonia as being driven mainly by necessity-related motives. Hence, we also expect to find that high-income households are attracted more by islands and coastal areas, and low-income households by the country's central areas.

1.3. Changing patterns of urbanisation and counter-urbanisation in Estonia

1.3.1. migration intensity within the settlement system.

We start by analysing changes in migration intensity or the number of moves between the levels of the settlement system for each thousand inhabitants each year, and how this varies over time and between population groups. We find that migration intensity for Estonia's total population was at 12‰ per annum, both during the 1989–2000 and the 2000–2011 inter-census periods ( Table 1 , first row). This means that in each year an average of twelve people out of every thousand relocated between the five levels of the Estonian settlement system. A significant drop in residential relocation within the settlement system took place in the 2011–2014 period of economic bust, when migration intensity fell to 7‰ per annum. However, recovery from the economic crises was rapid in Estonia, with the result that the intensity of domestic migration increased to 17‰ per annum in 2015–2019. Interestingly, we are not able to detect any drop in migration intensity at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, meaning that the first corona year did not bring with it any major shifts in the number of moves within the settlement system for each thousand people.

Annual number of moves per 1000 inhabitants in the settlement system for the total population and for selected population groups (‰), 1989–2021.

However, migration intensity varies significantly between population groups. Ethnicity-wise, the migration intensity was 16‰ for Estonians and 5‰ for the mainly Russian-speaking ethnic minorities during the 1989–2000 inter-census period ( Table 1 ). Migration intensity for Estonians is systematically higher throughout the overall thirty-year period. This implies that the migration of native Estonians has a bigger impact on domestic migration within the settlement system when compared to migration activities for ethnic minorities. This is not surprising since members of the ethnic minority population were already highly clustered in higher levels of the settlement system in the end of the Soviet period, reducing the need to move for new economic opportunities in the cities that opened up in the 1990s. Age-wise, young adults aged between 30 and 49 have a much higher migration intensity when compared to other age groups, something which can be expected. What is more interesting is that migration intensity for young adults has been significantly higher (37‰) since 2015 when compared to earlier periods. For example, during the 2000–2011 inter-census period, when the Estonian economy was experiencing a boom, migration intensity was 19‰ per annum for young adults. There are no major differences in migration intensity between men and women over the entire thirty-year period.

The last two individual characteristics in Table 1 include education and occupation. These individuals characteristics include people fifteen years of age or older (in the case of education), and people who have a job (in the case of occupation). Education-wise, we find that the higher the level of education, the lower is migration intensity throughout the entire thirty-year period. Migration intensity increased significantly across all occupational groups in 2015–2019 when compared to earlier periods, and particularly amongst highly-skilled and medium-skilled individuals who seem to have had more opportunities on the labour market during this period of economic boom. For example, migration intensity for highly-skilled people increased to 25‰ per annum in 2015–2019 when compared to a figure of 7‰ per annum during earlier periods. As the pandemic took hold in 2020, the mobility of highly-skilled and medium-skilled people dropped, but this was not the case for low-skilled workers, with the overall consequence being that there were no differences in migration intensity between occupational groups in 2020, varying within the range of 19–20‰ per annum.

1.3.2. Migration up and down in the settlement system

We find less temporal variations in migration flows, either upwards or downwards, between the five levels of the settlement system when compared to temporal changes in migration intensity. ‘Migration Concentration Index’ (MCI) values are over fifty in all periods, implying that the number of upwards moves in the settlement system (urbanisation) outnumber downwards moves in the settlement system (counter-urbanisation). The MCI value for the total population was at fifty-nine during the 1989–2000 inter-census period ( Table 2 , first row). This implies that fifty-nine percent of moves were from lower-to-higher levels in the Estonian settlement system. The trend towards urbanisation strengthened during the 2000–2011 inter-census period, with the MCI value increasing to sixty-eight. This was an economic boom period in Estonia. During the subsequent economic bust in 2011–2014, the MCI figure dropped to sixty, while it increased to sixty-three during the next period of economic boom in 2015–2019, and again dropped, to fifty-six, during the first year of the pandemic. We therefore find clear evidence of an increase in urbanisation during periods of economic boom, and an opposing increase in the importance of counter-urbanisation during periods of economic bust. The MCI value of fifty-six for the first year of the pandemic is very close to the break-even value of fifty, meaning that upwards and downwards moves within the settlement system were almost equal in size.

Migration Concentration Index (MCI), total population and selected population groups, 1989–2021.

Some important differences in MCI values can be detected between population groups. The MCI value was higher for Estonians (60) than it was for Russian-speaking minorities (53), but only during the 1989–2000 inter-census period ( Table 2 , second row). Since then, MCI values have become bigger for ethnic minorities. In addition, during the first year of the pandemic, the MCI value for ethnic minorities is significantly higher (65) when compared to Estonians (54). This implies that the growth of counter-urban moves during the pandemic is due mainly to changes in migration of Estonians. Age-wise, only young adults aged between 15 and 29 have clearly contributed to urbanisation during the entire thirty-year period. This also applies to the first year of the pandemic, when the MCI value for young adults was at sixty-eight. MCI values vary more for other age groups. It is interesting to single out the MCI values for children aged up to fourteen years of age, which have changed more than any other age group during the thirty-year period. As under-aged children move together with their parents, this serves to indicate changing migration patterns for entire families. During the 1989–2000 and 2000–2011 inter-census periods, the MCI value for children aged up to fourteen years of age was over seventy, indicating strong urbanisation. The MCI value for children (and therefore entire families) dropped to fifty-four during the economic downturn in 2011–2014, and to forty-seven during the first year of the pandemic, referring to the dominance of counter-urbanisation. Counter-urbanisation has also become more common amongst people within the older working age and retired people.

There are no major gender-differences in migration within the settlement system, although men have contributed slightly more to counter-urban migration than have women during the overall thirty-year period. The gender gap in counter-urbanisation was especially big during the 2011–2014 economic bust, but it narrowed down during the pandemic, with MCI values being at fifty-six and fifty-seven, respectively, for men and women. This implies that the intensity of urbanisation has also slowed down for women. Education-wise, people with a primary education contributed most to urbanisation until the mid-2000s, with MCI values being greater than sixty, probably reflecting intense education-related migration amongst them. People with a tertiary education contributed least to urbanisation, with MCI values being lower than sixty, reflecting the fact they are already residing in cities while they obtain their university degrees. Since 2015, educational differences have decreased in terms of moving up and down the settlement hierarchy, with MCI values dropping below sixty for all educational groups in the first year of the pandemic. Occupation-wise, migration flows for highly-skilled and medium-skilled individuals up and down the settlement system are more responsive to periods of economic boom and bust when compared to the figures for low-skilled individuals. Migration of low-skilled people is characterised mainly by urbanisation, both in times of economic boom and bust. Highly-skilled and medium-skilled people urbanise more rapidly during times of economic boom, while counter-urbanisation becomes more important for the same groups during economic bust. To illustrate this fact, the MCI value for highly-skilled individuals was seventy-one, the highest figure out of the three occupational groups during the economic boom period in 2015–2019. Both during the 2011–2014 economic bust and during the first year of the pandemic, the MCI values for highly-skilled individuals came closest to the break-even value of fifty out of the three occupational groups, or fifty-one and fifty-seven respectively.

1.3.3. Origins and destinations in the settlement system

More than half of moves within the settlement system relate to the capital city's urban region and non-metropolitan rural areas. For example, twenty-nine percent of all moves were related to non-metropolitan rural areas during the 1989–2000 inter-census period ( Table 3 ), and twenty-four percent were linked to the Tallinn urban region. In the 2000–2011 inter-census period, the biggest share of moves between the levels of the settlement system were related to Tallinn urban region (28%), followed by non-metropolitan rural areas (25%). Let us now turn to the analyses in the changes in the annualised net migration rate. We find that the net migration gain was 3‰ per annum in the Tallinn urban region in the 1989–2000 inter-census period ( Fig. 2 ). The net migration loss was −4‰ per annum in rural areas, which implies that non-metropolitan rural communities lost an average of four people out of every thousand each year during the 1990s as a result of domestic migration. Since then, urbanisation and counter-urbanisation processes have fluctuate according to the cycle of economic boom and bust. The decade of major societal transformations which took place in the 1990s was followed by rapid economic growth in the 2000s, which then strengthened the trend towards urbanisation. The negative net migration rate was −9‰ per annum in non-metropolitan rural areas during the 2000–2011 inter-census period, while the positive net migration rate was 7‰ per annum in the capital city's urban region.

Migration origins and destinations within the settlement system, 1989–2020.

Net migration rate in non-metropolitan rural areas and in the Tallinn urban region (‰), 1989–2021.

Source: Estonian Infotechnological Mobility Observatory, own calculations.

The global economic recession of 2009 had a significant impact on the Estonian labour and housing markets. This period of economic bust weakened urbanisation and strengthened counter-urbanisation in 2011–2015. Tallinn's urban region still remained the main net gainer of domestic migrants at the expense of other urban regions, but the net positive migration rate dropped significantly when compared to figures for the previous decade, or to 3‰ per annum, while the net migration rate for non-metropolitan rural areas was close to zero ( Fig. 2 ). Recovery from the global economic recession was rapid in Estonia that brought along a strengthening of urbanisation trend. In 2015–2019, non-metropolitan rural areas experienced high migration losses (−7‰ per annum) and the Tallinn metropolitan area experienced high migration gains (9‰ per annum). The first year of the global pandemic in 2020 again reversed this pattern, with net migration for non-metropolitan rural areas being close to zero, and migration gains in Tallinn urban region decreasing to 3‰. It follows that counter-urbanisation has gained more importance in all periods of economic bust, including the one which was driven by the global pandemic.

1.3.4. The geography of counter-urbanisation

These shifts between periods of intense urbanisation and the increased importance of counter-urbanisation is also reflected in changes in the net migration rate for Estonian localities ( Fig. 3 ). Most localities suffered from intense out-migration during the 2000–2011 inter-census period, especially those that are located in central and south-eastern parts of Estonia. These were areas of intense agricultural production during the Soviet period, but they lost their economic importance after Estonia regained its independence in 1991. Many localities on the islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa also lost people in the 2000s. Only the suburban areas around the three regional centres of Tallinn, Tartu, and Jõhvi gained migrants.

Net migration rate by localities (‰), 2000–2021.

This extensive rural exodus ended during the economic bust in the first half of the 2010s when migration to non-metropolitan rural areas became widespread. About half of non-metropolitan rural localities enjoyed positive net migration during the 2011–2015 period, while the rest suffered only from modest outwards-migration at that time. The economic boom within the 2015–2019 period brought along again migration losses non-metropolitan rural localities, but we can detect also important variations between them. Firstly, migration losses were concentrated mainly in the main agricultural areas in central Estonia. Secondly, many localities still gained migrants. In addition to positive net migration in the suburban areas around Tallinn and Tartu, the same positive net migration could also be found in western parts of Estonia, most notably on the two main islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, as well as in rural areas along the western coast between Pärnu and Tallinn. As with the economic bust in 2011–2014, the first year of the pandemic reveals widespread change which favours rural-ward migration; about half of non-metropolitan rural localities enjoyed positive net migration, and pockets of localities with positive net migration can be found everywhere in the countryside. In short, counter-urbanisation has not been a dominant migration trend in Estonia during the last thirty years, but non-metropolitan rural areas in general―and the islands and coastal regions in particular―have certainly become more attractive residential destinations to domestic migrants.

The MCI values revealed that the migration of highly-skilled individuals has been more responsive to cycles of economic boom and bust. The maps which are provided in Fig. 4 add more geographic detail in regards to migration for high-skilled and low-skilled individuals. We find that positive net migration rates of both high-skilled and low-skilled people are clustered around the four regional centres, while differences between the two occupational groups exist in non-metropolitan areas. We detect a more intense out out-migration of high-skilled people in central parts of Estonia, and more intense in-migration of low-skilled people in south-east Estonia. The period of economic bust in 2011–2014 brought along a more intense migration of highly-skilled people to non-metropolitan rural areas. The highest net migration values could be found on the islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and in the coastal areas between Pärnu and Tallinn. These are the most attractive non-metropolitan rural destinations in Estonia. Interestingly, the new period of economic growth in the 2015–2019 period again brought with it a major exodus of high-income households from almost all non-metropolitan rural localities, with the most notable exceptions being the islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa. A geographically similar but weaker pattern characterised the migration of low-skilled people at the same time. Finally, negative net migration rates either decreased or became positive across most non-metropolitan rural localities during the first year of the global pandemic with no major differences between high-skilled and low-skilled people. Overall, we can conclude the net migration rate of both high-skilled and low-skilled people tends to become negative during economic boom in most non-metropolitan rural municipalities, and positive during periods of economic bust. What is different is the magnitude of change as the migration of high-skilled people tends to be more responsive to periods of economic boom and bust compared to the migration of low-skilled people.

Net migration rate of low-skilled and high-skilled people by locality (‰), 2000–2021.

1.4. Summary and discussion

The aim of this paper was to shed new light upon the process of counter-urbanisation during the pandemic, in comparison with long-term changes in domestic migration during various periods of economic boom and bust. We defined counter-urbanisation as a process of moving from higher levels of a settlement system to lower levels of that same settlement system, and we were particularly interested in moves to non-metropolitan rural areas during the global coronavirus pandemic. As the pandemic brought about a slow-down in economic growth, our first research questions investigated potential changes in the intensity of migration within the settlement system during the past three decades, and how such migration tends to differ during periods of economic boom and bust, including at a time of a pandemic. We found that migration intensity has been generally responsive to the periods of economic boom and bust but not at times of pandemic. The number of moves per each thousand people was did not decrease in 2020 compared to the earlier period of quick economic growth. As could be expected, young adults aged up to thirty were the most mobile group throughout the length of the thirty-year study period but, more importantly, the mobility of young adults increased to a significantly greater degree than it did for other age groups in the second half of the 2010s, again with no change being registered during the first year of pandemic. Other groups with higher-than-average migration intensity levels during the entire thirty-year study period include members of the ethnic majority population and people with a primary education. Some interesting changes relate to moves being made in terms of occupation groups over time, as mobility increased significantly amongst highly-skilled and medium-skilled people during the economic boom in the 2015–2019 period, but it dropped again during the pandemic, with the overall result being that all occupational groups were equally mobile during the first year of the pandemic.

Our second research question investigated how the balance has changed between urban and counter-urban moves during the last three decades. We found that ‘Migration Concentration Index’ (MCI) values exceed fifty for the entire study period, implying that upward moves within the settlement system (urbanisation) outnumber downward moves within the settlement system (counter-urbanisation). The intensity of urbanisation and counter-urbanisation processes also fluctuates along with periods of economic boom and bust. At a time of economic boom, urbanisation prevails. At times of economic bust, including the first year of pandemic, counter-urbanisation becomes more important, and the migration gains in non-metropolitan rural areas are widespread. The migration of the high-skilled people is somewhat more responsive to periods of economic boom and bust compared to low-skilled people.

Our third research question seeked to find out what are the potential new features in the population composition and geography of moves into non-metropolitan rural areas during the pandemic when compared to earlier periods of economic boom and bust. The results show that the migration intensity of young adults increased, with this being the only age group to contribute to urbanisation. Age-wise, the most notable new feature that emerged during the pandemic was the counter-urbanisation of children under the age of fourteen, indicating that entire families were seeking homes in the countryside more often than they were seeking homes in metropolitan areas. Likewise, the first year of the pandemic reveals an increase in counter-urban migration amongst Estonians. Estonians living in cities have more connections to rural areas compared to ethnic minorities as their parents or grandparents may live in the countryside, or they may have inherited properties or second homes in rural areas (cf. Sandow and Lundholm, 2020 ). Finally, we did not detect any differences in counter-urbanisation between people with different levels of education and occupation during pandemic. However, high-skilled people move more often to attractive destinations in the countryside that include islands and coastal areas.

What could be possible explanations for such changes in domestic migration? A shift from a productionist to a post-production lifestyle (cf. Phillips et al., 2022 ), something which began in Estonia in the 1990s, has had two long-term impacts on rural migration, impacts which intensified during the pandemic. On the one hand, the increase in the share of young adults in each consecutive generation which has been seeking out a better education or working life in the cities has contributed to the rural exodus, as can also be found in other countries such as Sweden ( Bjerke and Mellander, 2017 ), the Czech Republic ( Vaishar and Pavlů, 2018 ), or Spain ( Llorent-Bedmar et al., 2021 ). On the other hand, both families with children and also retired people are now contributing to migration into non-metropolitan rural areas, especially since the start of the pandemic. Therefore, as has been found in Canada ( Mitchell, 2019 ), our analysis also reveals that while mainstream migration tends towards urbanisation, counter-urban migration has become more important as a substream movement at the national scale, and as a mainstream flow in many parts of the countryside.

The spread of counter-urbanisation among people in the family ages may be due to two reasons. Housing affordability in Estonian cities has significantly declined in the capital city urban region (cf. Hess et al., 2022 ). The housing affordability issue has become pressing also in many cities around the globe (van Ham et al., 2021), and seems to have an especially strong effect on families with children. By way of a comparison, a study university graduates in Sweden shows that having children is the single strongest predictor of leaving the cities ( Bjerke and Mellander, 2017 ). Our findings are very similar. Counter-urbanisation is more common amongst children aged up to fourteen years when compared to people who fall within the family bracket of 30–49. Since underaged children move with their parents rather than on their own, this implies that families with children are increasingly seeking homes outside the major metropolitan areas.

However, motives of counter-urbanisation may be very diverse for families. For example, while Elshof et al. (2017) find that families in the Netherlands are attracted by the rural idyll, Bjerke and Mellander (2017) argue that role of rural amenities are modest in Sweden in shaping the migration of families. Instead, they relate counter-urban moves of families to high local levels of welfare, such as the availability of good schools. The importance of well-being for families with children when moving to rural areas has been also found in Norway ( Berg, 2020 ). Karsten (2020) takes a longer view to explain that the scarcity of affordable housing in Amsterdam first led to urbanisation by families and, more recently, to counter-urbanisation.

Her results also show a diversity of mover types among families leaving the cities, including pragmatic movers, displaced families and happy movers ( Karsten, 2020 ). The intensification of moves of families into rural areas due to a wide range of reasons during the pandemic has also been found in Bulgaria ( Pileva and Markov, 2021 ). In short, there is growing evidence that families with children―both return migrants and newcomers―are seeking homes in non-metropolitan rural areas, which may potentially also help to mitigate the long-term problem of aging in the countryside (cf. Bjerke and Mellander, 2017 ). However, inner differences within rural areas are still a concern ( Vaishar et al., 2020 ) as our study also reveals that not all rural localities do gain from counter-urbanisation. What seems to be common across different countries, though, is the modest role of employment-related considerations as a defining feature of migration in post-productionist societies even for people who are of family and working ages: counter-urbanisers move due to the countryside various reasons and more often settle in post-productivist settlement types in the countryside (cf. Mitchell, 2019 ). Estonian case reveals that those rural areas with stronger agricultural base suffer from out-migration while coastal areas and islands gain migrants.

In addition to demographic change, there is also some evidence of socio-economic change taking place in rural areas. The combination of our findings that high-skilled people are more likely to counter-urbanise but their migration is more responsive to economic cycles in a way that moves to non-metropolitan areas intensify at periods of economic bust leads us to mixed interpretations. Firstly, the counter-urbanisation of better-off people does not necessarily reflect a solely preference-driven migration. As the economy slows down, access to long-term mortgages becomes more difficult and people tend to become more cautious in buying expensive homes in cities (cf. Nofsinger, 2012 ). Periods of economic bust could rather make families earning decent incomes to broaden the geographic reach of desired housing. In Estonia, these families seek homes that are located close to the waterfront, which is no different from gentrification processes in Tallinn that is also taking place at the waterfront. Parents earning higher incomes and relocating to rural areas can adapt their work and family life by switching partially to working from home and helping their kids to commute to school ( Pileva and Markov, 2021 ). As a consequence, the importance of rural areas as sites of employment continue to decrease, and the pandemic has reinforced this trend.

To conclude, the global pandemic has increased the attraction of rural living, just as earlier periods of economic bust had done. Pandemic did not only increase temporary moves out of the city ( Willberg et al., 2021 ) or purchases of second homes ( Greinke and Lange, 2022 ), but it also brought along an increase of residential relocations to non-metropolitan rural areas as shown by this study. Counter-urban migration during the pandemic became widespread amongst families, and the better-educated and highly-skilled people are also seeking homes in rural areas. These new features may serve to slow down or even reverse the long-term problems of an aging population loss of educated people in the countryside.

This project has received fuding from Estonian Research Council (PRG306, Infotechnological Mobility Laboratory) and from Estonian Academy of Sciences (research-professorship of Tiit Tammaru).

Author statement

Hereby we state that this paper is our original work and has not been submitted or will be submitted elsewhere for considering of publication.

Declaratin of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

- Annist A. In: Estonian Human Development Report. Tammaru T., Eamets R., Kallas K., editors. Eesti Koostöö Kogu; Tallinn: 2017. Emigration and the changing meaning of Estonian rural life. [ Google Scholar ]

- Argent N., Plummer P. Counter-urbanisation in pre-pandemic times. disentangling the influ. 2022 [ Google Scholar ]

- Argent N., Smailes P., Griffin T. The amenity complex: towards a framework for analysing and predicting the emergence of a multifunctional countryside in Australia. Cartographical Res. 2007; 45 :217–232. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atkinson R., Bridge G. Routledge; New York: 2005. Gentrification in a Global Context. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berg N.G. Geographies of wellbeing and place attachment: revisiting urban–rural migrants. J. Rural Stud. 2020; 78 :438–446. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry B. The counterurbanisation process: urban America since 1970. Urban Affairs Annual Rev. 1976; 11 :17–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bjarnason T., Stockdale A., Shuttleworth I., Eimermann M., Shucksmith M. At the intersection of urbanisation and counterurbanisation in rural space: microurbanisation in Northern Iceland. J. Rural Stud. 2021; 87 :404–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bjerke L., Mellander C. Moving home again? Never! The locational choices of graduates in Sweden. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2017; 59 :707–729. [ Google Scholar ]

- Budnitz B., Tranos E. Annals of the American Association of Geographers; 2021. Working from Home and Digital Divides: Resilience during the Pandemic. Published online 22 September 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Champion T. In: M Pacione), Applied Geography: Principles and Practic e . Pacione M., editor. Routledge; London: 1999. Urbanisation and counter-urbanisation; pp. 347–357. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delmelle E., Nilsson I., Adu P. Poverty suburbanisation, job accessibility, and employment outcomes. Soc. Incl. 2021; 9 (2):166–178. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dingel J.I., Neiman B. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2020. How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home? Working Paper 26948. http://www.nber.org/papers/w26948 Electroncially available at: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drudy P.J. Depopulation in a prosperous agricultural sub-region. Reg. Stud. 1978; 12 (1):49–60. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eimermann M., Lundmark M., Müller D.K. Exploring Dutch migration to rural Sweden: international counter-urbanisation in the EU. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2012; 103 :330–346. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elshof H., Haartsen T., van Wissen L.J.G., Mulder C.H. The influence of village attractiveness on flows of movers in a declining rural region. J. Rural Stud. 2017; 56 :39–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Estonian Infotechnological Observatory 2022. https://imo.ut.ee/en/ Electroncially available at:

- Fielding A. Migration and urbanisation in western Europe since 1950. Geogr. J. 1989; 155 :60–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Geyer H., Kontuly T. A theoretical foundation for the concept of differential urbanisation. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 1993; 17 :157–177. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gkartzios M. ‘Leaving Athens’: narratives of counterurbanisation in times of crisis. J. Rural Stud. 2013; 32 :158–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greinke L., Lange L. Multi-locality in rural areas – an underestimated phenomenon. Reg Stu, Regional Sci. 2022; 9 :67–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Halfacree K. To revitalise counter-urbanisation research? Recognising an international and fuller picture. Popul. Space Place. 2008; 14 (6):479–495. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hedberg C., Haandrikman K. Repopulation of the Swedish countryside: globalisation by international migration. J. Rural Stud. 2014; 34 :128–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Herslund L. The rural creative class: counter-urbanisation and entrepreneurship in the Danish countryside. Sociol. Rural. 2012; 52 (2):235–255. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess D.B., Tammaru T., Väiko A. Published Online; Town Planning Review: 2022. Effects of New Construction and Renovation on Ethnic and Social Mixing in Apartment Buildings in Estonia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hochstenbach C., Musterd S. Gentrification and the suburbanisation of poverty: changing urban geographies through boom and bust periods. Urban Geogr. 2018; 39 (1):26–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hugo G., Bell M. In: Migration into Rural Areas: Theories and Issues. Boyle P., Halfacree K., editors. Wiley; London: 1998. Hypothesis of welfare-led migration to rural areas: the Australian case; pp. 107–133. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jauhiainen J.S. Will the retiring baby boomers return to rural periphery? J. Rural Stud. 2009; 25 (1):25–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karsten L. Counter-urbanisation: why settled families move out of the city again. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020; 35 :29–442. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kontuly T., Tammaru T. Population subgroups responsible for new urbanization and suburbanization in Estonia. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2006; 13 (4):319–336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kornai J. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1992. The Socialist System: the Political Economy of Communism. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kozina J., Clifton N. City-region or urban-rural framework: what matters more in understanding the residential location of the creative class? Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019; 59 (1):141–157. [ Google Scholar ]

- Klocker N., Hodge P., Dun O., Crosbie E., Dufty-Jones R., McMichael C., Block K. Spaces of well-being and regional settlement: international migrants and the rural idyll. Popul. Space Place. 2021; 27 :e2443. [ Google Scholar ]

- Llorent-Bedmar V., Cobano-Delgado Palma V.C., Navarro-Granados M. The rural exodus of young people from empty Spain. Socio-educational aspects. J. Rural Stud. 2021; 82 :303–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marksoo A. In: Estonian Urban System in Transition. Palomäki M., Karunaratne J.A., Urban Development Editoes, Urban Life, editors. University of Vaasa; Vaasa: 1995. pp. 179–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- McManus P. Australian Geographer, Published online; 2022. Counterurbanisation, Demographic Change and Discourses of Rural Revival in Australia during COVID-19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitchell C.J.A. Making sense of counterurbanisation. J. Rural Stud. 2004; 20 :15–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitchell C.J.A. The patterns and places of counterurbanisation: a ‘macro’ perspective from Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. J. Rural Stud. 2019; 70 :104–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nofsinger J.R. Household behavior and boom/bust cycles. J. Financ. Stabil. 2012; 8 (3):161–173. [ Google Scholar ]

- Palang H. vol. 3. European Countryside; 2010. pp. 169–181. (Time Boundaries and Landscape Change: Collective Farms 1947-1994). [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips M. Rural gentrification and the processes of class colonisation. J. Rural Stud. 1993; 9 (2):123–140. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips M. Other geographies of gentrification. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004; 28 (1):5–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips M., Smith D., Brooking H., Duer M. The gentrification of a post-industrial English rural village: querying urban planetary perspectives. J. Rural Stud. 2022; 91 :108–125. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillipson J., Gorton M., Turner R., Shucksmith M., Aitken-McDermott K., Areal F., Cowie P., Hubbard C., Maioli S., McAreavey R., Souza-Monteiro D., Newbery R., Panzone L., Rowe F., Shortall S. The COVID-19 pandemic and its implications for rural economies. Sustainability. 2020; 12 :3973. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pileva D., Markov Counter-urbanisation and “return” to rurality? Implications of COVID-19 pandemic in Bulgaria. Glasnik Etnografskog SANU. 2021; 69 (3):543–560. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowe F., Bell M., Bernard A., Charles-Edwards E., Ueffing P. Impact of internal migration on population redistribution in Europe: urbanisation, counter-urbanisation or spatial equilibrium? Comparative Popul Stud. 2019; 44 :201–234. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandow E., Lundholm E. Which families move out from metropolitan areas? Counterurban migration and professions in Sweden. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2020; 27 (3):276–289. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sooväli-Sepping H., Roose A. Introduction on Estonian spatial development. Eesti Human Development Report 2019/2020: Spatial Choices for an Urbanising Society. Eesti Koostöö kogu; Tallinn: 2020. pp. 8–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stockdale A. The role of a ‘retirement transition’ in the repopulation of rural areas. Popul. Space Place. 2006; 12 (1):1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Šimon M. Exploring counter-urbanisation in a post-socialist context: case of the Czech Republic. Sociol. Rural. 2014; 54 (2):117–142. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tao X., Fu Z., Comber A.J. An analysis of modes of commuting in urban and rural areas. Applied Spatial Analysis. 2019; 12 :831–845. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tammaru T. Urban and rural population change in Estonia: patterns of differentiated and undifferentiated urbanisation. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2003; 94 :112–123. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tammaru T., Kulu H., Kask I. Urbanisation, suburbanisation, and counterurbanisation in Estonia. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2004; 45 (3):212–229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaishar A., Pavlů A. Outmigration intentions of secondary school students from a rural micro-region in the Czech periphery: a case study of the Bystrice nad Pernstejnem area in the Vysocina region. AUC Geogr. 2018; 53 (1):49–57. 53(1. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaishar A., Šastná M., Zapletalová J., Nováková E. Is the European countryside depopulating? Case study Moravia. J. Rural Stud. 2020; 80 :567–577. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Ham M., Tammaru T., Ubarevičienė R., Janssen H. Urban socio-economic segregation and income inequality: A global perspective. Springer; Dordrecht: 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vias A.C. 2012. Micropolitan Areas and Urbanisation Processes in the US. Cities 29; pp. S24–S28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Willberg E., Järv O., Väisänen T., Toivonen T. Escaping from cities during the COVID-19 crisis: using mobile phone data to trace mobility in Finland. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021; 10 (2):103. [ Google Scholar ]

Counter Urbanisation as Refuge During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study from Turkey

- Levent Memiş Giresun University, Turkey

- Sönmez Düzgün Giresun University, Turkey

- Semih Köseoglu Giresun University, Turkey

Migration is one of the most fundamental features of human history. Migration still plays an important role today and can occur between countries and settlements for different reasons. Migration activities bring various problems and needs regarding the everyday components of life. In this context, one of the types of migration is counter-urbanisation. Counter-urbanisation refers to moving from the city to the countryside or small settlements with predominantly rural characteristics. Urban areas maintain their attractiveness for individuals and organisations. However, living conditions and the city's structure bring ruralisation to the agenda. This study focuses on counter-urbanisation, a phenomenon that has been reshaped with the COVID-19 pandemic. It examines the impact of this counter-urbanisation on transforming the countryside's communal needs and physical structure. In this context, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 84 people in 17 villages of three districts in Giresun province located in the Black Sea Region of Turkey, and the observation method was utilised. According to the research findings, retirees carry out counter-urbanisation. However, the tendencies of these people covering the pandemic bring on the concept of counter-urbanisation as a refuge. Counter-urbanisation renders the existing organisational structures inadequate regarding communal services and brings new needs to the agenda. On the other hand, efforts to improve existing housing and create new housing bring new situations to the agenda for villages. With policies that will overcome the limitations of these new situations, it will be possible to support the elderly policies carried out by the country and contribute to sustainable development goals by supporting the production in rural areas. This potential calls for regulations and holistic policies that consider life and production functions in rural areas.

- Memiş et al.

ISSN (Online) 1849-2150

ISSN (Print) 1848-0357

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31297/hkju

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

COUNTER-URBANISATION EXPERIENCE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: THE CASE OF ISTANBUL METROPOLITAN AREA

2022, VII. INTERNATIONAL CITY PLANNING AND URBAN DESIGN CONFERENCE CPUD '22 CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS

Urbanization is the popular phenomenon in the 1950s that was replaced with counter-urbanization in the 1970s, which defines the population movement from metropolitan areas to rural settlements. The counterurbanization mobility that is directly shaped by economic development, legal regulations, technological developments, causes the socio-economic and spatial transformation of rural settlements. although there are exceptions, the counter-urbanization process is generally associated with economic development. The research aims to reveal the differences of the counter-urbanization movement in developed and developing countries in terms of process, causes, and effects, and how Turkey's counter-urbanization experience differs from the world examples. With this aim, the method of the research is to examine the counter-urbanization literature in-depth, to put forward the counter-urbanization conceptually. While rural development, gentrification, and sustainability are the focus of rural research in Turkey, the counter-urbanization which has a direct impact on rural areas, has not been sufficiently researched yet. In this way, this research contributes to the counterurbanization literature. However, rural areas are ignored by the legal regulations, rural settlements which are the basis of the country's socio-economic and spatial sustainability are transformed from production centers to consumption centers with the effects of counter-urbanization. The differentiation of the counter-urbanization process according to country, region, and metropolitan scale and blurring of rural-urban borders in metropolitan cities make it difficult to define the counter-urbanization movement. In this context, the definition of the counter-urbanization process within the borders of the metropolitan area, the driving forces causing counterurbanization, and its socio-economic and spatial effects on rural settlements were examined through the example of Istanbul, one of the most important metropolises of Turkey. As seen in the example of Istanbul, the transformation process of the rural life model and the rural economy, the social relations in rural areas, and the counter-urbanized social group differ from the world examples. While the counter-urbanization process emerged with the individual preferences of the households who are ready to adopt the rural life model, in developing countries such as Turkey is managed by mega-scale public and private investments, plan decisions, transformation in legal and administrative structure, and rent. While the rural life form is preserved in developed countries, the urban and rural population acts with a collective consciousness and social integration is ensured. For example, while the rural population transfers the place-specific knowledge to the urban population, the urban population supports rural production models with the integration of information technologies and contributes positively to the socio-economic development of the rural areas. In Turkey, legal regulations, directing public and private investments to rural areas by planning tools resulted in urban sprawl and rural areas and population urbanized with real-estate and construction-oriented development model. Moreover, counterurbanized groups in Turkey even if the movement reason is natural and rural idly, they prefer to isolate themselves from the rural population socio-spatially and deepen the social segregation. Although the counterurbanization process in Turkey started at the local level in the 2000s, factors such as the socio-economic problems experienced in the recent period, the increase in density in the cities and urban problems, the change in the urban demographic structure, and the pandemic trigger the desire for life in the rural areas, and it is observed that the counter-urbanization trend will continue. In this context, to define the counter-urbanization concept clearly and examine the counter-urbanization process in the world is so important to guide the counterurbanization process in Turkey.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

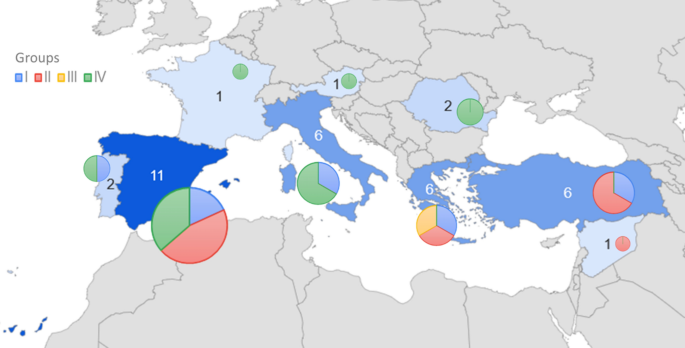

Effects of counter-urbanization on Mediterranean rural landscapes

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 29 August 2023

- Volume 38 , pages 3695–3711, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- C. Herrero-Jáuregui 1 &

- E. D. Concepción 2

1887 Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Counter-urbanization, or the reverse migration from the city to the countryside, is a well-known demographic trend associated with rural restructuring since the 1980s. Counter-urbanization is particularly relevant in social-ecological systems with a long history of human land use, such as the Mediterranean ones. However, the extent and impacts of this phenomenon are largely unknown, particularly in this region.

We aim to review the state of the issue of counter-urbanization in the Mediterranean region. We focus on the particular determinants and outcomes of this phenomenon in Mediterranean landscapes.