- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

A, The size of the circles denotes the contribution of participants in each intervention and the thickness of the lines between circles represents the contribution of studies comparing the two interventions. B, The bar graph shows the probability of the 6 interventions ranking from best to worst based on their effectiveness. IA indicates intra-articular.

eTable 1. Explanation of the Components of the GRADE Tool and How They Were Assessed

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Assessments

eTable 3. Results of Comparisons of Interventions Assessed by Fewer Than 3 Studies and Were Not Pooled Qualitatively or Quantitatively

eTable 4. Results of Grading of the Certainty of Evidence According to the GRADE Tool for Each Comparison of Interventions

eTable 5. Results of Statistical Inconsistency Assessment for Each Pairwise Meta-analysis

eFigure 1. Results of Pairwise Meta-analyses with Respective Mean Differences for Early Short-term Outcomes

eFigure 2. Results of Pairwise Meta-analyses With Respective Mean Differences for Late Short-term Outcomes

eFigure 3. Results of Pairwise Meta-analyses With Respective Mean Differences for Mid-term Outcomes

eFigure 4. Results of Pairwise Meta-analyses With Respective Mean Differences for Function

eFigure 5. TSA Results for IA Corticosteroid vs No Treatment or Placebo for Early Short-term Pain

eFigure 6. TSA Results for IA Corticosteroid vs No Treatment or Placebo for Late Short-term Pain

eFigure 7. Network Forest Plots With Consistency Test for Late Short-term Pain

eFigure 8. Network Forest Plots With Consistency Test for Mid-term Pain

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Challoumas D , Biddle M , McLean M , Millar NL. Comparison of Treatments for Frozen Shoulder : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis . JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029581. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29581

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Comparison of Treatments for Frozen Shoulder : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- 1 Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, College of Medicine, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom

Question Are any treatment modalities for frozen shoulder associated with better outcomes than other treatments?

Findings In this meta-analysis of 65 studies with 4097 participants, intra-articular corticosteroid was associated with increased short-term benefits compared with other nonsurgical treatments, and its superiority appeared to last for as long as 6 months. The addition of a home exercise program and/or electrotherapy or passive mobilizations may be associated with added benefits.

Meaning The results of this study suggest that intra-articular corticosteroid should be offered to patients with frozen shoulder at first contact.

Importance There are a myriad of available treatment options for patients with frozen shoulder, which can be overwhelming to the treating health care professional.

Objective To assess and compare the effectiveness of available treatment options for frozen shoulder to guide musculoskeletal practitioners and inform guidelines.

Data Sources Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, and CINHAL were searched in February 2020.

Study Selection Studies with a randomized design of any type that compared treatment modalities for frozen shoulder with other modalities, placebo, or no treatment were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis Data were independently extracted by 2 individuals. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. Random-effects models were used.

Main Outcomes and Measures Pain and function were the primary outcomes, and external rotation range of movement (ER ROM) was the secondary outcome. Results of pairwise meta-analyses were presented as mean differences (MDs) for pain and ER ROM and standardized mean differences (SMDs) for function. Length of follow-up was divided into short-term (≤12 weeks), mid-term (>12 weeks to ≤12 months), and long-term (>12 months) follow-up.

Results From a total of 65 eligible studies with 4097 participants that were included in the systematic review, 34 studies with 2402 participants were included in pairwise meta-analyses and 39 studies with 2736 participants in network meta-analyses. Despite several statistically significant results in pairwise meta-analyses, only the administration of intra-articular (IA) corticosteroid was associated with statistical and clinical superiority compared with other interventions in the short-term for pain (vs no treatment or placebo: MD, −1.0 visual analog scale [VAS] point; 95% CI, −1.5 to −0.5 VAS points; P < .001; vs physiotherapy: MD, −1.1 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.7 to −0.5 VAS points; P < .001) and function (vs no treatment or placebo: SMD, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.9; P < .001; vs physiotherapy: SMD 0.5; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.7; P < .001). Subgroup analyses and the network meta-analysis demonstrated that the addition of a home exercise program with simple exercises and stretches and physiotherapy (electrotherapy and/or mobilizations) to IA corticosteroid may be associated with added benefits in the mid-term (eg, pain for IA coritocosteriod with home exercise vs no treatment or placebo: MD, −1.4 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.8 to −1.1 VAS points; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance The findings of this study suggest that the early use of IA corticosteroid in patients with frozen shoulder of less than 1-year duration is associated with better outcomes. This treatment should be accompanied by a home exercise program to maximize the chance of recovery.

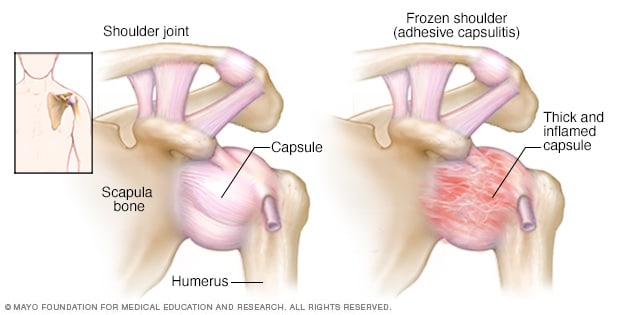

Adhesive capsulitis, also known as frozen shoulder, is a common shoulder concern manifesting in progressive loss of glenohumeral movements coupled with pain. 1 It is a fibroproliferative tissue fibrosis, and although the immunobiological advances in other diseases have helped dissect the pathophysiology of this condition, overall, the molecular mechanisms underpinning it remain poorly understood. 2 - 5

Frozen shoulder manifests clinically as shoulder pain with progressive restricted movement, both active and passive, along with normal radiographic scans of the glenohumeral joint. 6 It classically progresses prognostically through 3 overlapping stages of pain (stage 1, lasting 2-9 months), stiffness (stage 2, lasting 4-12 months), and recovery (stage 3, lasting 5-24 months). 7 However, this is an estimated time frame, and many patients can still experience symptoms at 6 years. 8 A primary care–based observational study estimated its incidence as 2.4 per 100 000 individuals per year, 9 with prevalence varying from less than 1% to 2% of the population. 10

A true evidence-based model for its medical management has not been defined, with a wide spectrum of operative and nonoperative treatments available. From the international to departmental level, management strategies vary widely, reflecting the lack of good-quality evidence. 11 The British Elbow and Shoulder Society/British Orthopaedic Association (BESS/BOA) has published recommendations in a patient care pathway for frozen shoulder, with a step-up approach in terms of invasiveness advised. 12 The UK Frozen Shoulder Trial, a randomized parallel trial comparing the clinical and cost-effectiveness of early structured physiotherapy, manipulation under anesthetic (MUA), and arthroscopic capsular release (ACR) is currently under way. 13 The aim of this systematic review is to present the available evidence relevant to treatment and outcomes for frozen shoulder with the ultimate objective of guiding clinical practice, both in primary and secondary care.

The present systematic review has been conducted and authored according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses ( PRISMA ) reporting guideline. 14 Our patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) was defined as follows: patients, patients with frozen shoulder of any etiology, duration, and severity; intervention, any treatment modality for frozen shoulder; comparison, any other treatment modality, placebo, or no treatment; and outcome, pain and function (primary outcomes) and external rotation range of movement (ER ROM) (secondary outcome) in the short term, midterm, or long term.

Included studies had a randomized design of any type and compared treatment modalities for frozen shoulder with other treatment modalities, placebo, or no treatment. Additionally, at least 1 of our preset outcome measures needed to be included in the study. Studies that compared different types, regimens, dosages, or durations of the same intervention were excluded (eg, different doses of corticosteroid or different exercise types). Those assessing the effectiveness of the same modality applied in different anatomical sites (eg, subacromial vs intra-articular [IA] corticosteroid) were included. Participants had to be older than 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis. No formal diagnostic criteria were used to define frozen shoulder; however, the use of inappropriate or inadequate diagnostic criteria was taken into account in risk-of-bias assessments. Duration of the condition was not a criterion nor were previous treatments and follow-up. Inclusion of patients with specific conditions (eg, diabetes) was not an exclusion criterion, and it was not taken into account in analyses, provided that their proportion in the treatment groups was comparable.

Nonrandomized comparative studies, observational studies, case reports, case series, literature reviews, published conference abstracts, and studies published in languages other than English were excluded. Studies including patients with the general diagnosis of shoulder pain were also excluded even if a proportion of them had frozen shoulder. Studies assessing the effectiveness of different types of physiotherapy-led interventions, exercise, or stretching regimens were also excluded.

A thorough literature search was conducted by 3 of us (D.C., M.B., and M.M.) via Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, and CINAHL in February 2020, with the following Boolean operators in all fields: ( adhesive capsulitis OR frozen shoulder OR shoulder periarthritis ) AND ( treatment OR management OR therapy ) AND randomi* ). Relevant review articles were screened to identify eligible articles that may have been missed at the initial search. Additionally, reference list screening and citation tracking in Google Scholar were performed for each eligible article.

From a total of 73 299 articles that were initially identified, after exclusion of duplicate and noneligible articles, title and abstract screening, and the addition of missed studies identified subsequently, 65 studies were found to fulfil the eligibility criteria. Figure 1 illustrates the article screening process.

The internal validity (freedom from bias) of each included study was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials separately by 2 of us (D.C. and M.B.), and a third independent opinion (M.M.) was sought when disagreements existed. 15 Studies were characterized as having low, high, or unclear overall risk of bias based on the following formula: low overall risk studies had high risk of bias in 2 or fewer domains; high overall risk studies had high risk of bias in more than 2 domains; unclear overall risk studies had unclear risk of bias in more than 2 domains, unless they also had high risk of bias in more than 2 domains, in which case they were labeled as high overall risk. Risk of bias was assessed separately for outcome measures that included patient reporting (pain, function) and those that did not (ROM); all studies with nonmasked participants were labeled as high risk in the masking of outcome measures domain for patient-reported outcomes given that the assessors were the participants themselves.

Certainty of evidence was graded with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) tool (eTable 1 in the Supplement ). 16 The scale starts with high, and depending on how many of the 5 possible limitations used in the GRADE tool were present in each comparison, the study could be downgraded to moderate, low, and very low. Grading of evidence was performed by 2 authors (D.C. and M.B.) independently and any disagreements were resolved by discussion and involvement of a third assessor (M.M.). Each outcome measure within each comparison had its own evidence grade. Our recommendations for clinical practice were based on results of either high or moderate quality evidence with both clinical and statistical significance.

Two of us (D.C. and M.B.) performed data extraction. The key characteristics of each eligible article were extracted and inserted in tables in Microsoft Word version 16.43 (Microsoft Corp) to facilitate analysis and presentation. For missing data, attempts were made to contact the original investigators for included studies published less than 10 years ago.

For the presentation of results, outcomes were divided into short-term (≤12 weeks), mid-term (>2 weeks to ≤12 months), and long-term (>12 months) follow-up. When sufficient data existed, short-term follow-up was subdivided into early short-term (2-6 weeks) and late short-term (8-12 weeks). All short-term follow-up points were converted to weeks, and all mid-term follow-up points to months for consistency and easier analysis.

Comparisons of interventions reported by fewer than 3 studies were included in the supplementary results table and were not analyzed or included in the article. When 3 or more studies contributed data for outcome measures at similar follow up times (ie, 2-6 weeks, 8-12 weeks, and 4-6 months), pairwise meta-analyses were conducted. Raw mean differences (MDs) with their accompanying 95% CIs were calculated and used in the tests for each comparison of pain and ER ROM because the tools used across studies were the same. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used for function because different functional scores were used.

When pain results were reported in different settings (eg, at rest, at night, with activity) in studies, only pain at rest was used in results. When both active and passive ROM were used as outcome measures, passive ROM was used in our results to increase homogeneity given that most studies used passive ROM. Results for the following outcome measures were recorded in tables and combined qualitatively only based on direction of effect to yield an overall effect for each comparison: abduction ROM, flexion ROM, and quality of life. However, these were not included in the results nor was the quality of the relevant evidence graded.

Additionally, comparisons that yielded both clinically and statistically significant results (ie, greater than or equal to the minimal clinically relevant difference and P < .05) underwent trial sequential analysis (TSA) to rule out a type I error and further reinforce our recommendations for clinical practice. TSA is a quantitative method applying sequential monitoring boundaries to cumulative meta-analyses in a similar fashion as the application of group sequential monitoring boundaries in single trials to decide whether they could be terminated early because of a sufficiently small P value. TSA is considered an interim meta-analysis; it helps control for type I and II errors and clarifies whether additional trials are needed by considering required information size. 17 The TSA graph includes 2 horizontal lines, representing the conventional thresholds for statistical significance ( Z = 1.96; P < .05); 1 vertical line, representing required information size; a curved red line, representing the TSA boundaries (ie, thresholds for statistical significance); and a blue line showing the cumulative amount of information as trials are added. A significant result is denoted by a crossing of the curved blue and red lines.

Finally, a network meta-analysis was conducted for treatments used by 3 or more studies for the primary outcome (pain) at late short-term (8-12 weeks) and mid-term (4-6 months) follow-up. Both direct and indirect comparisons were included in the model, and treatment rank probabilities were produced for the 2 follow-up time periods. The certainty of evidence deriving from network meta-analyses was not graded. Subgroup analyses for the effect of home exercise, different physiotherapy interventions, and chronicity of frozen shoulder were conducted when possible.

The term physiotherapy was used for any supervised, physiotherapist-led, noninvasive treatment (mobilizations, application of ice and heat, diathermy, electrotherapy modalities). These were grouped and analyzed together. Exercises and stretching that were performed by the participants at home (home exercise program) or under a physiotherapist’s supervision were not included in physiotherapy. Acupuncture and extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) were regarded as a separate intervention to physiotherapy. Interventions that had accompanying physiotherapy were grouped and analyzed separately from those that did not, regardless of intensity and frequency. For example, studies with a treatment group who received IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy (eg, ice packs and diathermy) were included in the intervention category IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy; those with a treatment group receiving only IA corticosteroid (with or without a home exercise program) were included in the IA corticosteroid category. Patients in the following groups were considered control groups and were analyzed together: no treatment, placebo, sham procedures, IA normal saline or lidocaine, simple analgesia, and home exercise alone.

The following tools and questionnaires that were found in included studies represented our function outcome measure: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder score, Constant-Murley, and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. All patient-reported pain and function scales were uniformly converted to a scale from 0 to 10 and a scale from 0 to 100, respectively.

The Review Manager version 5 (RevMan) software was used for pairwise meta-analyses and their accompanying forest plots and heterogeneity tests (χ 2 and I 2 ). TSA software version 0.9β (Copenhagen Trial Unit) was used for TSAs; random-effect models with 5% type I error and 20% power and O’Brien-Fleming α-spending function were used for all TSA analyses. The required information size was estimated by the software based on the power (20%), mean difference, variance, and heterogeneity. Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp) with the mvmeta extension (multivariate random-effects meta-regression) was used for network meta-analyses (frequentist approach). 18

When exact mean and SD values were not reported in the included articles, approximate values (to the nearest decimal place) were derived from the graphs. When only interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported, the SD was calculated as IQR divided by 1.35. When only the median was reported, the mean was assumed to be the same. When CIs of means were reported, SDs were calculated by dividing the length of the CI by 3.92 and then multiplying by the square root of the sample size. When SEs of mean were given, these were converted to SDs by multiplying them by the square root of the sample size. In studies in which only means and the population were given, the SD was imputed using the SDs of other similar studies using the prognostic method (ie, calculating the mean of all SDs). 19 Pooled means were calculated by adding all the means, multiplied by their sample size, and then dividing this by the sum of all sample sizes. Pooled SDs were calculated with the following formula: SD pooled = √(SD 1 2 [ n 1 -1]) + (SD 2 2 [ n 2 -1]) + … + (SD k 2 [ n k -1]) / ( n 1 + n 2 + … + n k – k ), where n indicates sample size and k , the number of samples. The following formula was used for the sample size calculation as part of GRADE’s assessment for imprecision 20 :

In which N indicates the sample size required in each of the groups; ( x 1 – x 2 ) indicates the minimal clinically relevant difference (MCRD), defined as 1 point for VAS pain, effect size of 0.45 for functional scores, and 10° for ER ROM; SD 2 indicates the population variance, calculated using pooled SD from our treatment groups; a = 1.96, for 5% type I error; and b = 0.842, for 80% power.

The MCRD for function on functional scales would have been set at 10 points. However, because SMDs were used, which produce effect sizes, rather than MDs, the 10 points were divided by the population SD (ie, 22) that was used to calculate the optimal information size (effect sizes can be converted back to functional scores when multiplied by SD).

Potential publication bias was evaluated by Egger test for asymmetry of the funnel plot in comparisons including more than 10 studies. Expecting wide-range variability in studies’ settings, a random-effects metasynthesis was employed in all comparisons.

Subgroup analyses were conducted with independent samples t tests in Graphpad version 8 (Prism) comparing pooled means and SDs. All statistical significance levels were set at P < .05, tests were 2-tailed, and clinical significance was defined as a MD or SMD being equal or higher than our predefined MCRD.

Of the 65 eligible studies, a total of 34 studies 21 - 54 were included in pairwise meta-analyses with a total of 2402 participants with frozen shoulder. Duration of symptoms ranged from 1 month to 7 years and length of follow-up from 1 week to 2 years, with most follow-up occurring at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies. 21 - 87 eTable 2 in the Supplement shows the results of the risk-of-bias assessment.

Table 2 summarizes the findings of the present review. Where feasible (ie, results at similar follow-up times in at least 3 studies), pairwise meta-analyses were conducted. The results of abduction ROM, flexion ROM, and quality of life were pooled only based on direction of effect, and their certainty of evidence was not graded. eTable 3 in the Supplement summarizes the results of comparisons reported by 1 or 2 studies only. eTable 4 in the Supplement demonstrates how the strength of evidence for each outcome measure within each comparison was derived for all follow-up time categories, per GRADE. eTable 5 in the Supplement shows the heterogeneity for each comparison ( I 2 statistic) and where studies were removed to reduce heterogeneity based on sensitivity analyses.

We conducted pairwise meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of each intervention with other interventions (or placebo/no treatment) in the short-term (early, 2-6 weeks; late, 8-12 weeks) and mid-term (4-6 months). Data for long-term follow-up (>12 months) were inadequate for analyses. Numerical data are only presented for the statistically significant comparisons; those for nonsignificant comparisons appear in the forest plots (eFigure 1, eFigure 2, and eFigure 3 in the Supplement ).

IA corticosteroid appeared to be associated with superior outcomes compared with control for early short-term pain (moderate certainty; MD, −1.4 visual analog scale [VAS] points; 95% CI, −1.8 to −0.9 VAS points; P < .001), ER ROM (high certainty; MD, 4.7°; 95% CI, 2.7° to 6.6°; P < .001), and function (high certainty; SMD, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.9; P < .001) and late short-term pain (moderate certainty; MD, −1.0 VAS points; −1.5 to −0.5 VAS points; P < .001), ER ROM (high certainty; MD, 6.8°; 95% CI, 3.4° to 10.2°; P < .001), and function (moderate certainty; SMD, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8; P < .001).

IA corticosteroid was associated with better outcomes than control only for function (moderate certainty; SMD, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.5; P = .01). However, effects for pain and ER ROM were similar (moderate certainty for both).

Physiotherapy was found to be associated with improved outcomes compared with control in the early short-term for ER ROM (moderate certainty; MD, 11.3°; 95% CI, 8.6°-14.0°; P < .001). Data for other follow-up time periods were insufficient for quantitative analysis.

Combined treatment with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy was associated with superior outcomes vs control for early short-term ER ROM (high certainty; MD, 17.9°; 95% CI, 12.1°-23.7°; P < .001). Data for other follow-up periods were insufficient for quantitative analysis.

IA corticosteroid was associated with significant benefits compared with physiotherapy for early short-term function (moderate certainty; MD, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.7; P < .001) and late short-term pain (high certainty; MD, −1.1 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.7 to −0.5 VAS points; P < .001) only. Differences for early short-term pain (moderate certainty), late short-term function (moderate certainty), and early and late short-term ER ROM (moderate and high certainty, respectively) were insignificant.

IA corticosteroid was associated with better outcomes than physiotherapy for ER ROM (moderate certainty; MD, 4.6°; 95% CI, 0.7°-8.6°; P = .02). However, no significant differences in pain (low certainty) or function (moderate certainty) were observed.

Compared with IA corticosteroid alone, combined treatment with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy was only associated with superior outcomes for early short-term ER ROM (moderate certainty; MD, 11.6°; 95% CI, 3.7°-19.4°; P = .004). Pain and function in the early short-term (moderate and low certainty, respectively) and late short-term function (high certainty) were similar between groups.

No significant differences were found between the groups in pain, function, or ER ROM. These results had high, moderate, and high certainty, respectively.

Combined therapy with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy was associated with significant benefits compared with physiotherapy alone only for early short-term function (low certainty; SMD, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.3-1.0; P < .001). Differences for early short-term pain and ER ROM and late short-term function were not significant (moderate certainty for all).

No significant differences were found between the groups for pain, function, or ER ROM. These comparisons had moderate, low, and high certainty, respectively.

Compared with subacromial administration, administering corticosteroid intra-articularly was only associated with superior outcomes for early short-term pain (moderate certainty; MD, −0.6 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.1 to −0.1 VAS points; P = .02) and late short-term function (moderate certainty; SMD, 0.3; 95% CI, 0 to 0.6; P = .03). Improvements in late short-term pain (moderate certainty) and ER ROM (high certainty) and early short-term function (high certainty) were similar with the 2 interventions.

No significant differences were found between the groups for pain or ER ROM. These comparisons had moderate and high certainty, respectively.

Adding arthrographic distension to IA corticosteroid appeared to be associated with greater improvements in early and late short-term pain (early: high certainty; MD, −0.9 VAS points; −1.3 to −0.4 VAS points; P < .001; late: high certainty; MD, −0.8 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.1 to −0.5 VAS points; P < .001). Early and late short-term function (moderate and high certainty, respectively) and early and late short-term ER ROM (high certainty for both) were similar with or without distension.

No differences were found with the addition of acupuncture to physiotherapy for early short-term pain and ER ROM. These comparisons had low and high certainty, respectively.

Despite several statistically significant differences in pairwise comparisons, most did not reach the threshold for MCRD. Only IA corticosteroid vs no treatment or placebo for early and late short-term pain and function, physiotherapy with and without IA corticosteroid vs no treatment or placebo for early short-term ER ROM, IA corticosteroid vs physiotherapy for early short-term function and late short-term pain, and combination therapy with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy compared with IA corticosteroid for early short-term ER ROM and with physiotherapy for early short-term function reached MCRD.

For the primary outcome measure, the clinically and statistically significant results underwent TSA, which confirmed the results ruling out a type I error in 2 comparisons (IA corticosteroid vs no treatment or placebo for early and late short-term pain) but not in the comparison of IA corticosteroid vs physiotherapy for late short-term pain. This suggests that more studies may be needed to confirm the benefit of IA corticosteroid compared with physiotherapy with more confidence.

eFigures 1 to 3 in the Supplement illustrate the results of the pairwise meta-analyses and associated forest plots for early short-term, late short-term, and mid-term follow up for pain and ER ROM. eFigure 4 in the Supplement illustrates the forest plots for function, and eFigure 5 and eFigure 6 in the Supplement illustrate the TSA graphs.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the network maps and treatment rank probabilities for the primary outcome measure (pain) for late short-term (8-12 weeks) and mid-term (4-6 months) follow-up, respectively. eFigure 7 and eFigure 8 in the Supplement illustrates the network forests with their consistency tests.

In the late short-term, arthrographic distension plus IA corticosteroid had the highest probability (96%) of being the most effective treatment. IA corticosteroid had the highest probability (85%) of being the second most effective. Physiotherapy was the least effective treatment, followed by no treatment or placebo. No data existed in the late short-term for combined treatment with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy ( Figure 2 B).

In the mid-term, combined treatment with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy had the highest probability (43%) of being the best treatment with physiotherapy. IA corticosteroid had the highest probability (34%) of being the second best treatment. No treatment or placebo followed by subacromial corticosteroid had the highest probability of being the worst interventions ( Figure 3 B).

The potential benefit of home exercise was assessed by comparing the mean improvement in pain in patients who received (1) IA corticosteroid plus a home exercise program vs IA corticosteroid without home exercise, and (2) no treatment or placebo plus home exercise vs no treatment/placebo without home exercise. For the first comparison, a statistically significant (but clinically small) mean benefit of home exercise on pain improvement was identified at 8 to 12 weeks (MD, −0.5 VAS points; 95% CI, −0.9 to −0.1 VAS points; P = .01). The benefit of home exercise was much more substantial (clinically and statistically) in those receiving no treatment or placebo (MD, −1.4 VAS points; 95% CI, −1.8 to −1.1 VAS points; P < .001). Both results are based on 10 studies 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 49 with low overall risk of bias.

Similarly, we assessed for an effect of IA placebo by comparing samples who received IA placebo and no treatment from the IA corticosteroid vs no treatment or placebo comparison. Both subgroups received a home exercise program. Based on 9 studies 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 49 with high overall risk of bias, IA placebo was associated with statistically and clinically significant effects on pain compared with no treatment (MD, −1.6 VAS points; 95% CI, −2.1 to −1.1 VAS points; P < .001).

There was insufficient data for a similar subgroup analysis at mid-term follow-up. Subgroup analyses for the effect of chronicity on the effectiveness of treatment modalities could not be evaluated because studies including patients with mixed stages and chronicity of frozen shoulder did not include subgroup data. Finally, subgroup analyses according to physiotherapeutic interventions were not possible because of high clinical heterogeneity (various combinations of modalities and treatment durations used). Most studies used electrotherapy modalities (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, therapeutic ultrasound, diathermy) combined with mobilizations, stretching, or exercises with or without heat and ice packs.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and network meta-analysis to comprehensively analyze all nonsurgical randomized clinical trials pertaining to the treatment of frozen shoulder as well as the largest systematic review ever published in the field. Based on the available evidence, it appears that the use of an IA corticosteroid for patients with frozen shoulder of duration less than 1 year is associated with greater benefits compared with all other interventions, and its benefits may last as long as 6 months. This has important treatment ramifications for the general and specialist musculoskeletal practitioner, providing them with an accessible, cost-effective, 88 and evidence-based treatment to supplement exercise regimes, which we anticipate will inform national guidelines on frozen shoulder treatments moving forward.

In the short-term, IA corticosteroid appeared to be associated with better outcomes compared with no treatment in all outcome measures. Adding arthrographic distension to IA corticosteroid may be associated with positive effects that last at least as long as 12 weeks compared with IA corticosteroid alone; however, these benefits are probably not clinically significant. Compared with physiotherapy, IA corticosteroid seemed to be associated with better outcomes, with clinically significant differences. Combination therapy with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy may be associated with significant benefits compared with IA corticosteroid alone or physiotherapy alone for ER ROM and function, respectively, at 6 weeks. Compared with control, combined IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy appeared to be associated with an early benefit in ER ROM (as long as 6 weeks), with clinical significance. Subacromial administration of corticosteroid appeared to be as efficacious as IA administration. The addition of acupuncture to physiotherapy did not seem to be associated with any added benefits. Based on the network meta-analysis, arthrographic distension with IA corticosteroid was probably the most effective intervention for pain at 12 weeks follow-up. IA corticosteroid alone ranked second, and as demonstrated by the pairwise meta-analysis, the benefit of adding distension appeared clinically nonsignificant.

Most compared interventions appeared to be associated with similar outcomes at 6-month follow up, without significant differences. The only intervention that was associated with mid-term statistically significant benefits compared with control and physiotherapy (without reaching clinical significance) was IA corticosteroid for function and ER ROM. No mid-term data exist assessing the effectiveness of adding arthrographic distension to IA corticosteroid and acupuncture to physiotherapy or comparing physiotherapy (with or without IA corticosteroid) with no treatment. Our network meta-analysis found that combined therapy with IA corticosteroid and physiotherapy, physiotherapy alone, and IA corticosteroid alone were the most effective interventions for pain at 6 months follow-up. However, according to our pairwise meta-analyses, their clinical benefit compared with other treatments (or even no treatment) appeared very small.

A home exercise program with simple ROM exercises and stretches administered with or without IA corticosteroid appeared to be associated with short-term pain benefits. This was statistically significant but clinically nonsignificant compared with no treatment when accompanied by IA corticosteroid. It was both clinically and statistically significant on its own.

Several systematic reviews have been published assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions for frozen shoulder. Sun et al 89 looked at the effectiveness if IA corticosteroid by comparing it with no treatment, and their findings were similar to ours, reporting that IA corticosteroid may be associated with benefits on pain, function, and ROM that are most pronounced in the short-term and can last as long as 6 months. The systematic review of both randomized and observational studies by Song et al 90 is also in agreement with our results, showing a possible early benefit of IA corticosteroid, which likely diminishes in the mid-term. An earlier systematic review by Maund et al, 88 which was only based on limited evidence (meta-analyses of 2 and 3 studies), was largely inconclusive, demonstrating possible benefits of IA corticosteroid (with and without physiotherapy) in conjunction with a home exercise program. A Cochrane review on arthrographic distension 91 was also in agreement with our results, showing that arthrographic distension with IA corticosteroid may be associated with short-term benefits in pain, ROM, and function. Their comparison of combined treatment vs IA corticosteroid alone yielded no significant differences; however, it was only based on 2 studies. A 2018 systematic review by Saltychev et al 92 also supports our findings, having demonstrated a small but clinically insignificant benefit of the addition of arthrographic distension to IA corticosteroid. In their systematic review, Catapano et al 93 reported that the addition of arthrographic distension to IA corticosteroid may be associated with a clinically significant benefit at 3 months; however, no quantitative analyses were conducted. Finally, a Cochrane review investigating the effects of manual therapy and exercise 94 concluded that they are probably associated with worse outcomes compared with IA corticosteroid in the short-term, which is in accordance with the findings of the present review, and another study 95 investigating the effectiveness of electrotherapy modalities was inconclusive because of lack of sufficient evidence.

In this review we aimed to assess the comparative effectiveness of all interventions for frozen shoulder, both surgical and nonsurgical; however, conclusions on the former could not be reached given that included studies did not assess the same interventions, which precluded pooling their results. The existing literature is conflicting regarding the superiority of arthroscopic capsular release (ACR) over nonoperative modalities; De Carli et al 62 reported no short-term or long-term benefits of ACR plus MUA compared with IA corticosteroid plus physiotherapy in function or ROM. Conversely, Mukherjee et al 75 found that ACR was associated with significant improvements in pain, function, and ROM compared with IA corticosteroid in the short-term and mid-term. Gallacher et al 63 demonstrated mixed results, concluding that compared with IA corticosteroid plus arthrographic distension, combined treatment with ACR and IA corticosteroid may be associated with improved function, external rotation, and flexion ROM but not quality of life and abduction ROM in the short-term and mid-term. The risk of complications, where reported, was not higher in the surgical groups. 63 The existing evidence on MUA, which is not a surgical procedure per se although it is administered under general anesthesia, is more consistent, suggesting its lack of long-term superiority compared with other commonly used nonsurgical treatments or even no treatment. 65 , 71 , 76

Because of the paucity of robust evidence, no firm recommendations exist for clinical practice. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, 96 influenced in turn by the BESS/BOA recommendations, recommend a stepped approach, starting with physiotherapy and only considering IA corticosteroid if there is no, or slow, progress. 96 With our review, we provide convincing evidence that IA corticosteroid is associated with better short-term outcomes than other treatments, with possible benefits extending in the mid-term; therefore, we recommend its early use with an accompanying home exercise program. This can be supplemented with physiotherapy to further increase the chances of resolution of symptoms by 6 months.

Most patients in the included studies had duration of symptoms of less than 1 year; therefore, our management recommendations are strongest for this subgroup, which includes patients most commonly encountered in clinical practice. Based on the underlying pathophysiology of the condition, usual practice is to only administer IA corticosteroid in the painful and not freezing phase (also advised by NICE guidance 95 ); however, this is not backed up by evidence. In our review, studies that included patients with symptoms for more than 1 year reported equally substantial improvements in outcome measures including ROM and function; therefore, the benefits of corticosteroids may also apply to the freezing phase of frozen shoulder. 48 , 79

Despite the comprehensiveness and rigor of our methods, which include thorough risk of bias assessments and grading of evidence, we do recognize its limitations. Frozen shoulder of all chronicity was analyzed together; therefore; conclusions about specific stages and their most effective management could not be drawn. Most studies included a home exercise program, but its frequency, intensity, and duration were not taken into account in comparisons nor were separate analyses made adjusting for it. Finally, physiotherapy interventions, regardless of nature and duration, were grouped and analyzed together to minimize imprecision; in reality, some might be more effective than others. However, we only present findings that derived from thorough quantitative analyses, which were in turn substantially reinforced by the TSA, minimizing the risk for type I errors; most previous similar meta-analyses did not use TSA. Additionally, we present the first network meta-analysis including all conservative treatments for frozen shoulder. Furthermore, we based our recommendations on both statistically and clinically significant results.

Based on the findings of the present review, we recommend the use of IA corticosteroid for patients with frozen shoulder of duration less than 1 year because it appeared to have earlier benefits than other interventions; these benefits could last as long as 6 months. We also recommend an accompanying home exercise program with simple ROM exercises and stretches. The addition of physiotherapy in the form of an electrotherapy modality and supervised mobilizations should also be considered because it may add mid-term benefits and can be used on its own, especially when IA corticosteroid is contra-indicated. Implicated health care professionals should always emphasize to patients that frozen shoulder is a self-limiting condition that usually lasts for a few months but can sometimes take more than 1 year to resolve and its resolution may be expedited by IA corticosteroid. This should be offered at first contact, and an informed decision should be made by the patient after the risks and alternative therapies are presented to them. In the future, other interventions that have shown promising results and currently have inadequate evidence for definitive conclusions (eg, MUA, ACR, specific types of electrotherapy and mobilizations) should be assessed with large, well-designed randomized studies. Finally, future studies should include subgroup analyses assessing the effectiveness of specific interventions on frozen shoulder of different chronicity and stage.

Accepted for Publication: October 22, 2020.

Published: December 16, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29581

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2020 Challoumas D et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Neal L. Millar, MD, PhD, Institute of Infection, Immunity, and Inflammation, College of Medicine, Veterinary and Life Sciences University of Glasgow, 120 University Ave, Glasgow G12 8TA, United Kingdom ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Dr. Challoumas had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Challoumas, McLean, Millar.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Challoumas, Millar.

Statistical analysis: Challoumas.

Obtained funding: Millar.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Challoumas, McLean.

Supervision: Challoumas, Millar.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: This work was funded by grant MR/R020515/1 from the Medical Research Council UK.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Frozen shoulder

- Related content

- Peer review

- Marta Karbowiak , trauma and orthopaedics core trainee 1 ,

- Thomas Holme , trauma and orthopaedics registrar 2 ,

- Maisum Mirza , general practitioner 3 ,

- Nashat Siddiqui , consultant orthopaedic and upper limb surgeon 2

- 1 Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester, UK

- 2 Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Kingston upon Thames, UK

- 3 Warlingham Green Medical Practice, Warlingham, UK

- Correspondence to M Karbowiak mkarbowiak{at}doctors.org.uk

What you need to know

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk of developing frozen shoulder and having bilateral symptoms than the general population

Recovery times vary, but can be years, and some patients are left with residual pain or functional impairment

Physiotherapy is the most commonly used intervention and can be supplemented by intra-articular steroid injections

Treatments offered in secondary care include joint manipulation under anaesthesia, arthroscopic capsular release, and hydrodilatation

The UK FROST trial compared manipulation under anaesthetic, arthroscopic capsular release, and early structured physiotherapy with intra-articular corticosteroid injections, and found that none of the interventions were clinically superior

Frozen shoulder is a common and often debilitating condition that lacks a clear consensus on management, partly owing to a lack of high quality evidence on the various treatments options. In this clinical update, we offer an overview of the latest evidence on management of frozen shoulder, incorporating the clinical implications of recently published research, including the UK FROST study—the largest randomised controlled trial in this field to date, which compares surgical treatments with early structured physiotherapy and intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

What is frozen shoulder?

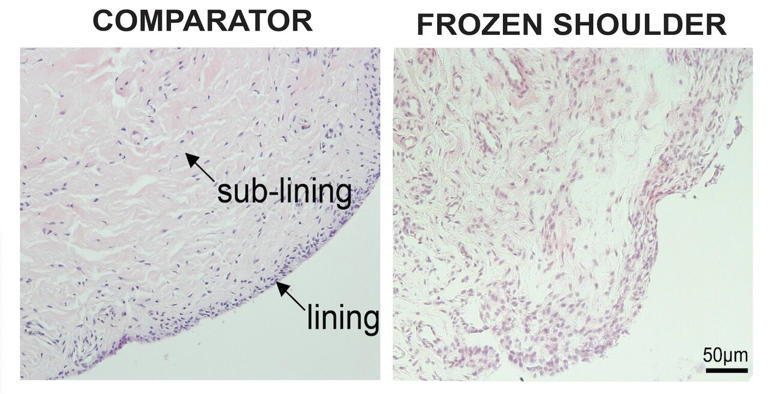

Frozen shoulder is a condition that results in development of thickened, fibrosed joint capsule, contraction of the joint, and reduced intra-articular volume. 1 The exact cause of these changes is unknown, with several possible processes suggested in the literature. 1 Over the years, uncertainty has surrounded the definition and classification of this condition, leading to inconsistencies in both clinical practice and scientific studies. 2 This is partially owing to the wide spectrum of clinical presentations, with patients experiencing different levels and combinations of symptoms. This also means their lives can be affected in many different ways, depending on the severity of the condition and their daily activities.

Who gets it?

The age of onset is usually in the fifth decade of life, with peak incidence between the ages of 40 and 60. 3 Women are more commonly affected than men, with one study reporting the incidence as 3.38 and 2.36 per 1000 person years, respectively. 4

Patients with diabetes have a 10% to 20% lifetime risk of developing frozen shoulder, 5 6 and are more likely to have bilateral shoulder involvement than the general population. 7 Frozen shoulder has been linked to conditions such as hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolaemia, and heart disease, although evidence is insufficient to determine whether these associations are independent. 8

How is it diagnosed?

Frozen shoulder is primarily a clinical diagnosis ( box 1 ). Patients can present with a range of symptoms related to the shoulder, although pain is often the initial trigger for presentation. Three distinct phases are commonly described, 11 with each phase typically lasting several months:

Diagnosis of frozen shoulder 9

History—insidious onset of shoulder pain, often anterolateral initially; pain at night; sometimes minimal trauma associated around time of onset

Examination—painful movement restriction, passive external rotation less than 30°, passive elevation less than 100°; cases where the disease affects the posterior capsule more than the anterior can present with reduction in internal rotation

Investigations—plain radiographs are useful to check for arthritic changes in the glenohumeral joint and are recommended by the British Elbow and Shoulder Society 10 ; ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging may be considered depending on the clinical features and differential diagnoses

Freezing/proliferative phase—stiffness with progressively worsening pain (usually constant but exacerbated by movement)

Frozen/adhesive phase—ongoing stiffness with improved pain levels, reduction in range of motion, in particular on external rotation

Thawing/resolution phase—gradual improvement in range of motion.

The clinical course can be variable 2 and not all people with frozen shoulder will experience all three of these stages. Pain at night is a common feature, often causing considerable disruption to sleep. Patients can also experience sudden jerking movements associated with pain. 2 Diagnostic pointers for frozen shoulder are summarised in box 2 , and differential diagnoses are listed in table 1 .

When to refer to secondary care

British Elbow and Shoulder Society guidelines 10 advise to refer:

Cases of atypical presentation or marked functional limitation

Persistence of pain despite primary care interventions beyond three months

American Family Physician guidelines recommend referral to a shoulder specialist if no improvement is seen with physiotherapy and corticosteroid injections after three months 12

Differential diagnoses

- View inline

What is the clinical course of frozen shoulder?

Frozen shoulder is often described in literature as a “self-limiting” condition, and patients typically experience resolution of symptoms without or regardless of any treatment. 13 Most people with the condition make a full recovery, although recovery time tends to be slow—between one and three years. 14 15 Some experience residual symptoms: the original prospective study on frozen shoulder from 1975 found that half of patients had residual clinical restriction in range of movement after 5-10 years, and 7% had ongoing functional limitation. 11 Similar rates were reported in more recent literature, with one study 6 of patients under the care of a specialist shoulder clinic followed up at average 52 months finding that 41% reported residual symptoms. Recurrence of primary frozen shoulder after the initial resolution of symptoms is poorly reported in literature, but in our experience is rare. Up to 20% of patients can develop the condition on the opposite side. 5 Patients with diabetes generally have poorer response to treatment and, with interventions such as manipulation under anaesthetic, are at higher risk of requiring further procedures. 16

How is frozen shoulder managed?

After establishing a clinical diagnosis of frozen shoulder, explain the typical progression of the condition. Discuss the range of available management options and the risks associated with each intervention ( table 2 ). An individual approach involving exploring the extent of functional limitation and establishing treatment goals can aid in deciding the appropriate treatment.

Summary of treatment options

Advise patients to continue to use the arm as pain allows. 9 Over-the-counter or prescription painkillers can help to alleviate pain, which is often the most debilitating symptom experienced in the early stages and can limit engagement with physiotherapy. Sleeping on the unaffected side or using pillows for support in bed can help with night time pain. Heat or ice packs over the affected area can be used for additional pain relief. Shoulder stiffness can lead to other musculoskeletal symptoms, most commonly neck and lower back pain, which can also be targeted with physiotherapy. In the early stages, we recommend patients try simple home exercises such as placing things higher up to encourage reaching, gentle stretching, and pendulum exercises. 17

Physiotherapy

The main role of physiotherapy is in the frozen/adhesive phase (when the initial symptoms of pain have subsided) with stretches and strengthening exercises. This should be sustained with additional resistance based exercises in the thawing/resolution phase. 18 Structured approaches include group or individual physiotherapy, with formal range of motion exercises, soft tissue massage, and trigger point release. 19 The recommended initial treatment course is six to 12 weeks. 5

Corticosteroid injections

Corticosteroid injections can help in reducing pain and improving range of movement, particularly in the early stages of the condition and when combined with physiotherapy. A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis on the management of frozen shoulder assessed the effectiveness of available treatment strategies across 65 studies with 4097 patients. 20 The authors found that intra-articular (IA) corticosteroid injections were associated with short term improvement in external rotation and pain compared with no treatment or placebo. IA corticosteroid injections with physiotherapy were found to be superior to IA corticosteroid injections alone for early range of motion only. Physiotherapy with IA corticosteroid injections was found to be superior to physiotherapy alone for short term outcomes using several symptom and functional scoring systems, but not for range of motion or medium term function.

IA steroid injections are associated with better pain relief compared with subacromial injections. 21 Interestingly, a 2021 clinical trial found that, even though ultrasound guided IA injections were associated with greater accuracy than blind IA injections, no difference was seen between them in pain and functional outcome scores. 22

Corticosteroid injections are generally considered safe and are associated with mild side effects only. In one study, three of 58 patients (5.2%) reported mild self-limiting nausea and dizziness. 23 Another reported that, of 133 participants, one patient (0.7%) experienced prolonged pain at the injection site, and three patients (2.3%) developed transient facial flushing. 24 Steroid injections can affect blood glucose control in patients with diabetes, particularly in the first day after the intervention. 25

Surgical options—arthroscopic capsular release and manipulation under anaesthetic

Arthroscopic capsular release (ACR) is a surgical procedure carried out under general or regional anaesthesia. The shoulder capsule is divided using arthroscopic instruments and the shoulder is re-examined to confirm optimal release. Manipulation under anaesthetic (MUA) is a procedure where the shoulder is manipulated by the surgeon to stretch and tear the joint capsule. It is carried out under general or regional anaesthesia.

The recently published UK FROST study compared ACR, MUA, and early structured physiotherapy with intra-articular corticosteroid injection. 26 The study is the largest randomised controlled trial of these interventions to date, with 503 participants recruited across 35 UK hospitals. In UK FROST, short term outcomes of ACR at three months were overall worse compared with physiotherapy with corticosteroid injection or MUA. However, at 12 months ACR was found to be associated with better functional scores (Oxford Shoulder Score, OSS) compared with both MUA and physiotherapy (OSS difference 2.01 and 3.06, respectively), although this was less than the clinically important effect size of 4-5 OSS points. The study authors concluded that none of the three interventions was clinically superior, but that ACR carried higher risks (3.9% in this cohort had a serious adverse event compared with 1% of those who had MUA), and MUA was the most cost effective intervention.

One weakness of UK FROST is that it was unable to determine to what extent the improvements in outcomes were the result of the interventions rather than the natural course of the condition. A randomised controlled trial of 125 patients in Finland 17 comparing MUA with supportive treatment (home exercises) found no difference in terms of pain levels or functional ability between the two groups at 12 month follow-up; minimal differences were noted in range of motion in favour of the MUA group. Another smaller RCT comparing ACR with supportive care did not find any significant differences between the two in functional outcome scores. 27

MUA is generally associated with low rates of adverse events—UK FROST 26 recorded two serious (1%) and 15 non-serious (7.5%) adverse events for 201 patients. These were largely minor reactions such as residual stiffness, nerve pain, and paraesthesia. One case (0.5%) of septic joint arthritis was recorded, and three patients (1.5%) experienced postoperative worsening of shoulder pain. MUA was found to be cost effective as functional improvement was seen sooner, meaning less need for prolonged physiotherapy and follow-up.

Hydrodilatation

Hydrodilatation involves injecting fluid into the shoulder joint to disrupt the capsular adhesions, and is usually performed in a clinic setting. Solutions used and volumes injected vary in literature, but most clinicians use normal saline with local anaesthetic and corticosteroid. 28 Hydrodilatation was not included in the UK-FROST study as it was not widely available until recently. It has since become a common management option alongside MUA and ACR in many UK secondary care centres.

A 2008 Cochrane review 29 noted hydrodilatation was associated with short term improvement in pain, function, and range of motion. However, a more recent 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis 28 found that the procedure had an overall insignificant effect on clinical outcomes—the authors noted minimal improvement in pain and range of motion (number needed to treat of 12) with no significant improvement in disability. One small randomised controlled trial 30 comparing MUA and hydrodilatation found that functional scores were significantly better in the hydrodilatation cohort with higher patient satisfaction rates, although the study was conducted in a small patient cohort (38 joints in total). At present, comparisons with surgical treatments are difficult owing to a lack of high quality evidence. A Delphi study 31 backed by the British Elbow and Shoulder Society is under way to help inform future directions of research. Adverse events reported with the use of hydrodilatation include pain, flushing, syncopal episodes, and one case of glenohumeral joint infection. 28

Education into practice

How might you explain the different stages of frozen shoulder to a patient first presenting with the condition?

What strategies could be used in the community to widen the access to physiotherapy for patients?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

A patient with experience of the condition reviewed a draft of the manuscript. In response to their feedback, we developed the section on management to include more detail about analgesia and adjuncts to physiotherapy.

How this article was created

We conducted a Medline search using the terms “frozen shoulder” and “adhesive capsulitis” to identify the relevant references and review the latest published evidence. We also searched the Cochrane library and consulted the British Elbow and Shoulder Society website for current guidelines.

Information resources for patients

British Elbow & Shoulder Society Website: advice on common shoulder conditions, when to seek medical advice, and recommended self-care measures: https://bess.ac.uk

Patient.info: information about the condition and management: https://patient.info/bones-joints-muscles/frozen-shoulder-leaflet

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: resource outlining treatment options and home exercises: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/frozen-shoulder/

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: information on managing shoulder pain and recommended exercises: https://www.csp.org.uk/publications/shoulder-pain-exercises

We have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Provenance and peer review: commissioned, based on an idea from the author; externally peer reviewed.

- Peloquin C ,

- Robinson CM ,

- Clipsham K ,

- Bridgman JF

- Guyver PM ,

- Goodchild L ,

- Brownson P ,

- Siegel LB ,

- Klinger HM ,

- von Knoch M

- Levine WN ,

- Kashyap CP ,

- Blaine TA ,

- Bigliani LU

- Macfarlane RJ ,

- Loganathan K

- Kivimäki J ,

- Pohjolainen T ,

- Malmivaara A ,

- Russell S ,

- Jariwala A ,

- Richards J ,

- Challoumas D ,

- Brealey SD ,

- UK FROST Study Group

- Smitherman JA ,

- Cricchio M ,

- Saltychev M ,

- Virolainen P ,

- Fredericson M

- Buchbinder R ,

- Johnston RV ,

- Quraishi NA ,

- Johnston P ,

- Chakrabarti AJ

- Brealey S ,

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 April 2022

Living with a frozen shoulder – a phenomenological inquiry

- Suellen Anne Lyne 1 , 2 ,

- Fiona Mary Goldblatt 1 , 2 &

- Ernst Michael Shanahan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8309-3289 1 , 2

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 23 , Article number: 318 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

8347 Accesses

12 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) is an inflammatory condition affecting the capsule of the glenohumeral joint. It is characterised by a painful restricted range of passive and active movement in all planes of motion. The impact of frozen shoulder on affected individuals remains poorly characterised. In this study we sought to better understand the lived experience of people suffering from frozen shoulder to characterise the physical, psychological and socioeconomic impact of the condition.

A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach was undertaken. Purposeful sampling was used to identify individuals for interview. Semi-structured interviews were performed and continued until saturation was achieved. A biopsychosocial framework was used during the analysis in order to generate themes which best described the phenomenon and reflected the lived experience of individuals’ suffering from this condition.

Ten interviews were conducted, and five main themes emerged including; the severity of the pain experience, a loss of independence, an altered sense of self, the significant psychological impact, and the variable experience with healthcare providers.

Conclusions

These findings offer an insight into the lived experience of individuals with frozen shoulder, both on a personal and sociocultural level. The pain endured has profound impacts on physical and mental health, with loss of function resulting in a narrative reconstruction and altered sense of self. Our findings illustrate that frozen shoulder is much more than a benign self-limiting musculoskeletal condition and should be managed accordingly.

Trial registration

ANZCTR 12620000677909 Registered 28/04/2020 https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=379719&isReview=true

Peer Review reports

Frozen shoulder is often poorly diagnosed and inadequately managed, and this study adds important insights on the lived experience of individuals suffering from frozen shoulder.

The severity and pervasiveness of the pain endured, a loss of independence and patients’ altered sense of self are profound representations of living with a frozen shoulder.

This study challenges us to reconsider whether our current treatment targets for frozen shoulder are appropriate.

An emphasis on early and effective pain management and on managing the psychological sequelae of the disease emerge from this study as key treatment targets.

Frozen shoulder is a common but often under-recognised condition. It is an inflammatory and fibrosing condition affecting the glenohumeral joint capsule, characterised by shoulder pain and stiffness with significant resultant disability [ 1 , 2 ]. The aetiology is unknown, however a number of risk factors have been identified including diabetes and shoulder trauma [ 1 , 3 ]. Frozen shoulder is considered primary if it occurs spontaneously, or secondary if there is an antecedent event such as trauma. The combined prevalence is estimated between 3 and 5% in the general population, but rates as high as 20% are reported in people with diabetes [ 4 , 5 ]. Peak age of onset is 40–60 years and women are affected slightly more often than men [ 6 , 7 ]. Given frozen shoulder typically affects those of working age, there are resultant economic impacts, both on a personal and societal level [ 8 ].

Frozen shoulder is predominantly a clinical diagnosis. Restriction of movement occurs in all planes of motion, both passive and active, and there is insufficient joint degeneration to account for the restricted movement [ 9 ]. The pathognomonic feature is almost complete loss of external rotation [ 7 ]. Additional investigations are usually non-contributory but can be useful in ruling out other pathologies. The natural history of frozen shoulder remains poorly understood [ 10 ], but the most commonly accepted description of disease progression is defined by three overlapping clinical phases. Phase one manifests as severe shoulder pain, typically worse at night, with concurrent progressive loss of motion. This phase can last 2–9 months and is known as the painful phase . Phase two, the frozen phase , lasts 4–12 months and is characterised by gradual reduction in pain, but persistent and considerable restriction in movement. Phase three, termed the resolution or thawing phase, and can last 12–36 months [ 3 ]. Few effective treatments are available which significantly alter the natural history of disease [ 2 ]. The extent of recovery is variable, with some reporting persistent pain and residual limitation of movement. In one large case series 35% of people had mild to moderate and 6% had severe symptoms, at a mean follow up of 4.4 years [ 11 ]. Recurrence is uncommon, although the contralateral shoulder can become affected in 6–17% of patients within the first 5 years [ 11 ]. In current practice the management of frozen shoulder has been primarily undertaken by orthopaedic surgeons and physical therapists who emphasise biomechanics and restoration of range of motion. This approach has tended to shape our understanding of the condition and influence treatment targets.

The clinical picture of frozen shoulder is well described but the impact on individual suffering is poorly characterised. Some people describe difficulties with basic activities of daily living, such as showering, dressing and cooking [ 8 ]. The pain is reported to interfere with sleep, which further intensifies the pain and impacts one’s ability to engage with domestic, social and occupational activities [ 12 , 13 ]. What remains poorly described is the experience of protracted and debilitating shoulder pain which has the potential for profound physical, psychological and socioeconomic consequences [ 14 ]. A recent systematic review of patients’ experiences with shoulder disorders in general concluded that patients contend with considerable disruption to their lives, impacting sleep, cognitive function and emotional wellbeing [ 12 ]. However, there is very limited data reporting the impact of frozen shoulder. One paper focused on patients’ experiences with conventional care pathways [ 8 ] and another examined patients’ experience of a specific treatment, Bowen’s technique [ 15 ]. To our knowledge, there have been no papers describing a holistic exploration of the lived experience of frozen shoulder.

Despite its prevalence, treatment outcomes for frozen shoulder continue to be modest [ 2 ]. Given this reality, it is important to ask why our treatments appear to be missing the mark. Is it possible our therapeutic targets are not the most appropriate for this poorly understood condition? Little is reported about the experience of individuals suffering from frozen shoulder, so in this paper we set out to better understand the lived experience. We believe this work to be important in helping to better manage this common medical condition. By improving understanding of the impact on the individual, we aim to increase practitioner awareness of the disease and its severity, facilitate earlier diagnosis and better design therapies which improve outcomes that are important to patients [ 16 ].

A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach was employed to explore the lived experience of a group of individuals suffering from frozen shoulder. Participants were identified from a group of patients with a recent diagnosis of frozen shoulder based on assessment by a specialist Rheumatologist. Inclusion criteria included male and female participants, aged over 18 years. There were no exclusion criteria. Patients were referred to the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network (SALHN) rheumatology outpatient clinic from community and hospital settings, including general practice, physiotherapists and specialty services, with the exception of one participant who was not previously known to the service. Purposive sampling was used to select individuals for interview. Patients who reported significant psychosocial impact from their frozen shoulder were invited to participate.

Interviews took place either in person at the rheumatology outpatient clinic or via audio and video telehealth, between June and August 2020. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted using an interview guide (Supplementary File 1 ) Following an introduction to orientate participants, the interviewer asked the interviewee to describe the impact of the frozen shoulder on their life. Questions were “directed to the participants’ experiences, feelings, beliefs and convictions about the theme in question” [ 17 ]. An iterative approach was used for the interviews, meaning that knowledge acquired in each interview helped guide questioning for interviews of subsequent participants and enabled identification of emergent themes [ 18 ]. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and data de-identified. Each transcript was given to the respective interviewee to read, and an opportunity provided to amend or add any material they felt relevant. Interviews were conducted by a single researcher, SL, who had no involvement in the participants’ medical care prior to study commencement, minimising risk of bias. SL is a rheumatologist who had professional knowledge of the condition and was trained in qualitative interview techniques. Interviewing was continued until saturation was achieved, that is until interviewees introduced no new perspectives, no new themes emerged, and no further coding was possible [ 19 , 20 ]. The SALHN Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (OFR number: 81.20, ANZCTR 12620000677909).

A phenomenological approach was deemed the most appropriate enquiry method because the research sought to understand the participants’ conscious experience; their judgments, perceptions and emotions [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. The philosophy of Husserl and methods described by Colaizzi were applied to analyse the interviews [ 21 , 24 ]. This involves reading the interviews in their entirety, repeatedly if necessary, in order to become familiar with the data set and develop a holistic sense of the interview, the “gestalt” [ 25 ]. The researchers attempt to bracket out their own prejudices and presuppositions to avoid prejudging the data and therefore allow true realisation of the essence of the experience in order to “enter the unique world of the informant/participant” [ 26 , 27 ]. Coding was conducted using NVivo 12 Qualitative Data Analysis Software [ 28 ]. Coding was performed by the three authoring researchers and all interviews were at least dual coded. The authors are rheumatologists with experience in qualitative research. Codes were collated and sorted, and units of meaning delineated, taking into account the literal content, the number of times the unit of meaning arose, and how the meaning was delivered. Themes were derived from the data rather than being identified in advance. Themes emerged as units of meaning were clustered, bringing together recurrent experience and its variant manifestations, in order to get to the essence of the phenomenon and elucidate the “lived experience” [ 29 , 30 ].