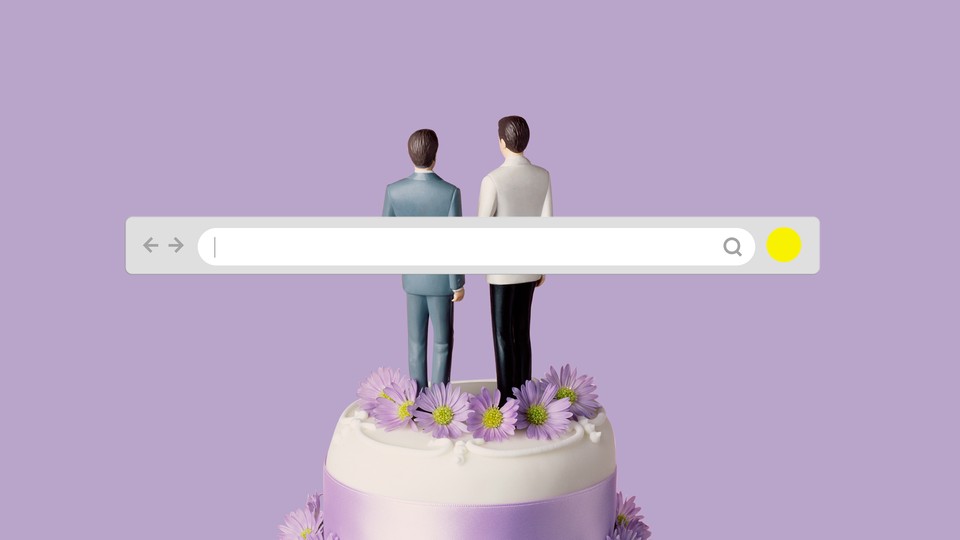

The Implications of Supreme Court’s 303 Creative Decision Are Already Being Felt

D ays after the Supreme Court handed down their decision in 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis and ruled in favor of a web designer who did not want to service same-sex couples because she says it infringes on her first amendment rights, a hairdresser in the small town of Traverse City, Michigan publicly posted about refusing service to clients who may have different pronouns than what they were assigned at birth.

“If a human identifies as anything other than a man/woman, please seek services at a local pet groomer,” Christine Geiger, the hair salon owner, said in a since-deleted Facebook post. “You are not welcome at this salon. Period.”

The Facebook page for the salon has also been deleted, but critics claim Geiger’s messaging is evidence of the troubling precedent set by 303 Creative.

“[This case is] a green light for people to engage in what was previously understood as discrimination,” said Katherine Franke, Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Gender & Sexuality Law at Columbia University. “People feel that they now are immune from any kind of consequences for engaging in that kind of violent bigoted speech.”

More from TIME

The ruling comes during a moment rife with uncertainty for LGBTQ+ rights. A May Department of Homeland Security briefing revealed that threats of violence against the queer community have increased within the last year, and nearly 500 anti-LGBTQ bills targeting gender-affirming care and drag have been introduced this legislative session. While many have been faced with temporary injunctions or found unconstitutional, and experts say that 303 Creative does not allow for explicit discrimination, changing attitudes about the LGBTQ+ community over the past year have been troubling.

“It’s not reasonable to interpret 303 Creative to allow that salon to engage in discrimination,” said Sarah Warbelow, the Human Rights Campaign’s Legal Director, “but these are exactly our long founded concerns. Not only for the real discrimination that will be permissible as a result of 303 Creative, but that it will inspire, discriminatory behavior, and really disgusting public discourse about LGBTQ people.”

In throwing out decades of legal precedent that have upheld anti-discrimination policies, legal experts say the case could open the door to more worrisome implications for the future. “It doesn’t eliminate [LGBTQ protections],” Warbelow says, “but it certainly created a crack.”

What was 303 Creative about?

The case was brought forward by Lorie Smith, a web designer who sought a pre enforcement challenge (a legal action filed before a plaintiff engages in conduct that they believe may go against a specific law) saying she was deterred from expanding her graphic design business to offer wedding websites because Colorado’s anti-discrimination law would require her to service queer couples. Smith says she does not condone gay marriages due to Christian beliefs, and she believed the law infringed on her rights.

By a 6-to-3 vote, the Supreme Court agreed, though not based on religious freedom protections, but rather free speech. The majority opinion found that because Smith’s website included text that would be customized to tell her client’s love story, it fell under the creator’s expression and therefore under the definition of “pure speech.”

“In this case, Colorado seeks to force an individual to speak in ways that align with its views but defy her conscience about a matter of major significance. The First Amendment envisions the United States as a rich and complex place where all persons are free to think and speak as they wish, not as the government demands,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote.

What are the implications of this case?

Legal experts like Rutgers law professor Katie Eyer says that the case was “decided on relatively narrow grounds” and “has emboldened much broader claims in the lower courts and among others who might wish to discriminate.”

In other words, the Court found that Smith had a broad “free speech” right that did not require her to follow Colorado anti-discrimination law, “but they also provided no limiting provisions on that right,” Franke says. That means that lower courts do not have a precise definition of “expressive activity” that would help decipher the types of businesses that are exempt from adhering to anti-discrimination standards. Experts expect increased litigation seeking to expand the category of expressive speech from websites to other creative activities, like baking a cake, though the exact way this plays out is yet to be seen.

“There’s also nothing in the opinion, that limits this right only to people who object to same sex marriage,” Franke adds. To be clear, the precedent set by 303 Creative would not allow the Michigan hairdresser to deny service to someone solely based on their gender or sexuality as cutting hair does not constitute speech.

But experts do question whether the ruling would expand to allow a web designer like Smith to deny servicing an interfaith couple, or one of a different religion.

What is even more troubling, Eyer adds, is that much of the clarification surrounding what qualifies as speech exempt from anti-discrimination laws will be decided in the lower courts. “This trajectory has really emboldened would-be discriminators to make even broader arguments about where they are entitled to discriminate,” she says. But that won’t change the lived realities of Americans who belong to protected groups. “Fundamentally, what any group that’s protected by anti-discrimination law wants, even if they win a lawsuit, is not to experience discrimination.”

Looking ahead

Attorneys are already looking to decipher whether 303 Creative allows other businesses or entities to refuse services to people based on the decision.

The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, for instance, is challenging two court cases: Billard v. Diocese of Charlotte— in which a gay substitute teacher who was fired after revealing his sexuality online successfully sued the school for discrimination—and the similar Fitzgerald v. Roncalli High School and Archdiocese of Indianapolis, per the Washington Post .

Attorneys representing the dioceses argue that hiring decisions should qualify as protected free speech. “If a for-profit business gets constitutional protection when deciding what services to sell [to] the general public, then, of course, a non-profit religious school gets constitutional protection when deciding who is religiously qualified to teach and embody the faith at a religious school,” Luke Goodrich, Vice President and Senior Counsel at The Becket Fund, told TIME in an email statement.

Experts TIME spoke to say that these cases do not have strong legal backing because the Court explicitly said the ruling did not apply to employment discrimination, but other cases like Braidwood Management Inc. v. Becerra could set a new precedent. In June, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Braidwood Management Inc, a Houston company that said that federal anti-discrimination laws do not apply to them because their religion dictates that people should be cisgender and heterosexual. Franke says that this case relates more to religious freedom than free speech, but the potential implications of this ruling could be troubling. That case may reach the Supreme Court in 2024, according to a case briefing from Columbia Law School.

The Texas Supreme Court also agreed to hear oral arguments related to a lawsuit by a Texas judge who first made headlines in 2019 when she filed a suit claiming that giving out marriage licenses to queer couples infringed on her religious freedom. Attorneys argue that 303 Creative is now applicable in the suit.

Other cases like Klein v. Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries —where a bakery refused to sell a wedding cake to a same-sex couple—will also be remanded for further consideration given the recent Supreme Court ruling to see if the creation of wedding cakes constitutes commercial speech in the same way Smith’s website does.

Those decisions could continue to pushback against previous legal understandings of equal protections.

“You would think that this would be a time when we express a strong American value of either tolerance or inclusion for all people in our society…but they’re doing just the opposite,” Franke says. “This is a brand new way of understanding the Constitution. Some rights are first tier” religious liberty, free speech, gun rights. And other rights, yes, you have them, but they’re second tier rights: LGBT equality, sex based equality, reproductive rights, and public health and safety. And when those rights come into conflict with first tier rights, they have to yield.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Skip to Main Content - Keyboard Accessible

- LII Supreme Court Bulletin

303 Creative LLC v. Elenis

LII note: The U.S. Supreme Court has now decided 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis .

- civil rights

- First Amendment

- freedom of speech

- discrimination

Issues

Does a public accommodation law violate the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment when it compels an artist to create custom designs that go against her beliefs?

This case asks the Supreme Court to balance public accommodation anti-discrimination laws and First Amendment rights. The Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act (“CADA”) limits a public accommodation’s ability to refuse services to a customer based on their identity, such as sexual orientation. 303 Creative LLC and its owner Lorie Smith argue that CADA violates their First Amendment rights to free artistic expression and religious belief. Respondent Aubrey Elenis, Director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division, counters that CADA regulates discriminatory commerce, not speech, and thus does not violate 303 Creative LLC’s First Amendment rights. The outcome of this case has heavy implications for LGBTQ+ rights, freedom of speech and religion, and creative expression.

Questions as Framed for the Court by the Parties

Whether applying a public-accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the free speech clause of the First Amendment.

Facts

Colorado's Anti-Discrimination Act (“CADA”) limits a place of public accommodation’s ability to refuse services to a customer based on their identity. 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis at 2. Under CADA, a place of public accommodation includes “any place of business engaged in any sales to the public and any place offering services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations to the public.” Id. In particular, the Accommodation Clause prevents a public accommodation from “directly or indirectly” refusing services “to an individual or a group” on account of their sexual orientation. Id. CADA’s Communication Clause prevents a public accommodation from “directly or indirectly” publishing a communication that suggests that their full range of “goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations” will be refused to a customer on account of their sexual orientation. Id.

Petitioner 303 Creative LLC (“303 Creative”) is a for-profit, graphic and website design company owned by Petitioner Lorie Smith (“Smith”), its founder and sole member-owner. Id. at 4. 303 Creative does not currently offer wedding-related services, but Smith intends to do so in the future. Id. Smith is willing to work with all people regardless of their sexual orientation and is also generally willing to create designs or websites for LGBTQ+ customers. Id. However, Smith genuinely believes that same-sex marriages conflict with God’s will. Id. Keeping in line with her religious beliefs, Smith does not plan on offering wedding-related services for same-sex weddings, regardless of who requests the service. Id.

Smith intends to publish a statement on 303 Creative’s business website explaining Smith’s religious objections to same-sex marriage. Id. Smith has not yet posted the proposed statement, nor does 303 Creative currently offer wedding-related services, because Smith does not wish to violate CADA. Id. at 6. Smith brought a pre-enforcement challenge to CADA in the United States District Court for the District of Colorado , alleging that its Accommodation and Communication Clauses violate the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment. Id. Respondent Aubrey Elenis, Director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division (“the Director”), moved to dismiss Smith’s complaint . Id.

At a motion hearing, the parties agreed that the case should be resolved through summary judgment , as there is no dispute as to the facts, but only as to the law. After completing summary judgment briefing, the district court found that Smith only established standing to challenge CADA’s Communication Clause, not the Accommodation Clause. Id. Following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Masterpiece Cakeshop, LTD. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission , the district court denied Smith’s summary judgment motion regarding CADA’s Communication Clause. Id. at 6–7. The district court further ruled that Smith needed to show cause as to why final judgment should not be granted in favor of the Director. Id. at 7.

After additional briefing, the district court ruled in favor of the Director on the motion for summary judgment. Id. Smith timely appealed the district court’s final judgment. Id.

On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit found that Smith had standing to challenge both the Accommodation Clause and Communication Clause. Brief for Petitioners , 303 Creative LLC and Lorie Smith, at 10. However, the Tenth Circuit ultimately affirmed the district court’s decision granting summary judgment in favor of the Director. Elenis at 47.

The Supreme Court granted Smith certiorari on February 22, 2022. Brief for Petitioners at 1.

Analysis

Regulation of speech or conduct.

Smith argues that the enforcement of CADA against artists like her violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment by compelling her to speak against her beliefs. Brief for Petitioners , 303 Creative LLC and Lorie Smith at 15. Smith contends that, under Hurley v. Irish-American, Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc. , the Free Speech Clause is violated if the forced accommodation involves a form of expression and the complaining speaker’s own message was affected by the speech they were forced to accommodate. Id. at 17–18. Smith posits that her custom wedding websites exist as pure speech because their individual components, that is, the printed word, pictures, drawings, etc., are forms of expression. Id. at 19. Smith also argues that her websites are expressive in nature because they express the unique moments of a couple’s love story and their plans for their future. Id. Smith contends that her own message is affected by CADA’s Accommodation Clause because it compels her to create speech that she otherwise would not make because it conflicts with her sincerely held religious beliefs. Id. at 20. Smith argues that the Accommodation Clause changes her message by forcing her to create speech celebrating same-sex marriage, which she deeply disagrees with, making the enforcement of CADA against her a constitutional violation. Id. at 23.

Smith further asserts that CADA compels speech, not conduct. Id. at 24. Smith contends that CADA makes speech itself the public accommodation and forces Smith to speak against her beliefs. Id. Smith argues that her websites are pure speech and not commercial conduct that can be regulated in compliance with the First Amendment. Id. at 24–26. Smith maintains that CADA does not regulate speech incidental to conduct, because the Accommodation Clause forces her to speak when she otherwise would remain silent, without any actual regulation of her conduct. Id. at 28. Smith argues that CADA regulates her speech, and not her clients’ speech, because she personally and actively creates, designs, and publishes her websites and designs. Id. at 29.

In response, the Director argues that the Accommodation Clause regulates discriminatory sales practices, not speech. Brief for Respondents , Aubrey Elenis et al. at 12. The Director contends that Smith’s reliance on Hurley is misplaced because Hurley dealt with the unique application of public accommodations law to a private parade organizer’s decision on which messages to include in their parade, not business practices, as is in this case . Id. at 17. The Director argues that the conduct that CADA targets (i.e., selling goods and services to the public) is not a form of expressive conduct. Id. at 20. The Director posits that by enforcing CADA, the state neither seeks to force Smith to recite state messages or speech, nor does it seek to alter or change Smith’s own message. Id at 19 . The Director contends that CADA aims at ensuring equal access to public accommodations and leaves the public accommodation free to choose whatever ideologies it wishes to present. Id. The Director asserts that Smith retains control over her services and what she may sell to the public; CADA only affects Smith’s ability to refuse those services and sales to same-sex couples that she would offer to heterosexual couples. Id. 19–20.

The Director further maintains that the Accommodation Clause focuses only on commercial conduct and is triggered once someone decides to offer services to the public, regardless of what those services are. Id. The Director argues that several Supreme Court decisions have made clear that public accommodations law can regulate conduct when it mandates equal access to goods and services, “even if the businesses engage in activities protected by the First Amendment.” Id. at 13. The Director posits that requiring businesses to comply with equal access does not turn a regulation of conduct into a burden on their expression, even if those businesses provide custom services. Id. at 14.

REGULATION OF CONTENT AND VIEWPOINT

Smith argues that not only does CADA compel speech, but it also does so based on the speaker’s content and viewpoint . Brief for Petitioners at 31. Smith contends that the Accommodation Clause forces her to create websites that celebrate same-sex marriage, which necessarily alters the content of her speech. Id. at 31–32. Smith posits that her choice to discuss a specific topic, namely opposite-sex marriage, serves as a trigger for the enforcement of CADA against her, and therefore CADA selectively penalizes some content. Id. Smith argues that CADA only grants access to her accommodation to those who disagree with the message she wishes to express, further targeting her viewpoint. Id. at 33. Smith maintains that the Communication Clause also regulates her speech based on content and viewpoint, because it only applies to speech on certain topics. Id. at 34.

The Director counters that Smith may create websites and designs expressing whatever message she wants to communicate; all that the Accommodation Clause requires is that she offers her services to the public regardless of her customer’s sexual orientation. Brief for Respondents at 15. The Director maintains that CADA leaves the content of Smith’s goods and services unregulated and completely within her control because she may choose the content and design of her websites without interference. Id. The Director also argues that the Communication Clause prohibits solely commercial speech that facilitates illegal discrimination. Id. at 44. The Director asserts that the Communication Clause does not prevent Smith from expressing her opposition to same-sex marriage—instead, CADA simply regulates speech that denies equal service, in violation of the law, based on a customer’s protected characteristic. Id. at 44–45. The Director contends that Smith is still able to express her beliefs concerning same-sex marriage while complying with her legal obligation to provide goods and services equally. Id. at 45.

STANDARD OF REVIEW AND STATE INTERESTS

Smith argues that because CADA compels speech and discriminates based on content and viewpoint, thus implicating a fundamental right , the law must satisfy strict scrutiny . Brief for Petitioners at 36. To pass strict scrutiny, Smith contends that the Director must prove that enforcing CADA against artists like Smith furthers a compelling government interest, and the enforcement is narrowly tailored to achieving that interest. Id. Smith maintains that the Director’s interests in eliminating discrimination and maintaining access to goods and services are too broad to serve as compelling interests. Id. at 37. Smith argues that the Director cannot show that Smith’s speech will undermine the state’s interest in combating discrimination because Smith “does not discriminate against anyone” and “will happily serve everyone” regardless of their sexual orientation. Id. Smith argues that allowing her to speak does not affect access to goods and services, because there are many designers in Colorado that will convey the messages that Smith refuses to convey. Id.

Smith further posits that the Director has multiple alternative options to achieve their interests, which proves that the enforcement of CADA is not narrowly tailored to that end. Id. at 47. Smith maintains that the Director could enforce CADA so as to allow speakers who serve all people to refuse certain projects based on their message, carve out textual exemptions for artists who decline projects based on their message, or narrow the definition of public accommodation under CADA. Id. at 47–48. Smith argues that the Director fails to show why less-intrusive methods such as these will fail and only speech compulsion will succeed. Id. at 49.

The Director responds that the state has a compelling interest in protecting equal access and equal dignity of all customers, which is supported by American history and tradition. Brief for Respondents at 35–36. The Director contends that the state’s interest in ensuring equal access is compelling because the denial of services based on identity has the effect of demoting someone to a second-class citizen. Id. at 39. The Director asserts that there are no less restrictive alternative means available to CADA. Id. at 40. The Director argues that discretionary exemptions suggested by Smith that allow businesses to deny equal access would swallow the state’s interest in providing equal access as a whole. Id. at 41. The Director also argues that Smith failed to show how an exemption to CADA for artists is feasible and that such an exemption has no limiting principle. Id. at 30–31.

The Director further contends that the correct level of scrutiny to apply is intermediate scrutiny because any burden on Smith’s speech is incidental to the Accommodation Clause’s regulation of conduct. Id. at 25. The Director posits that if there is a burden on Smith’s speech, that is simply the effect of CADA, rather than the law’s intent, and therefore intermediate scrutiny is more appropriate. Id. The Director maintains that applying intermediate scrutiny to a law that is not aimed at suppression, but that unintentionally burdens speech, is in line with Supreme Court cases upholding similar public accommodation laws, such as Ward v. Rock Against Racism and United States v. Albertini . Id. at 26.

Discussion

Principles of freedom under the first amendment.

Colorado state legislators (“State Legislators”), in support of Smith, argue that forcing individuals to express messages that they disagree with violates the fundamental rule of protection under the First Amendment. Brief of Amici Curiae Colorado State Legislators (“State Legislators” ) , in Support of Petitioners at 11. The State Legislators argue that nondiscriminatory laws such as CADA impose speech conditions that substantially interfere with speakers’ autonomy and freedom of speech. Id. at 9. The State Legislators further contend that enforcing such laws often weaponizes state action to eliminate a constitutional constraint, the Free Speech Clause. Id. at 12.

Six First Amendment Scholars (“Scholars”), in support of the Director, counter that allowing expressive freedom to supersede other laws of general applicability would jeopardize the very freedom the First Amendment aims to protect. Brief of Amici Curiae First Amendment Scholars (“Scholars” ) , in Support of Respondent at 18. The Scholars contend that allowing discrimination on the basis of the First Amendment in the commercial context inevitably permits subjective invalidation of general laws. Id. at 19. The Scholars argue that such distorted effects dilute free speech protection and weaken the First Amendment’s goal of “furthering the free and robust exchange of ideas” by creating unacceptable applications of the rule. Id.

SOCIETAL EFFECT OF PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION LAWS

The State Legislators, in support of Smith, argue that recognizing a compelling state interest in enforcing CADA would allow the government to subjectively infringe on speakers’ artistic expression. Brief of State Legislators at 16 . The State Legislators claim that the government wielding its enforcing power will inevitably lead to hostility and inequity toward religious viewpoints and identities. Id. at 18. State Legislators further purport that government action censuring speech protected under the First Amendment not only facilitate policies contrary to speakers’ conscience but also to their personal identities. Id. at 20.

Professor Dale Carpenter and others (“Professor Carpenter”), in support of Smith, argues that the government may ensure equal access to goods and services even if the Court recognizes Smith’s First Amendment right to decline to create a custom service. Brief of Amici Curiae Prof. Dale Carpenter et al. (“ Professor Carpenter ” ) , in Support of Petitioners at 18. Professor Carpenter distinguishes the bulk of goods and services, which people shall generally have access to, from expressive goods and services such as Smith’s, which he contends are protected under the First Amendment. Id. Professor Carpenter further notes that, although the Court has previously recognized a state interest in preventing entities from leveraging the monopoly of their services to silence other speakers, merely characterizing a business as a monopoly is not sufficient to deny that business protections under the First Amendment. Id. at 20.

The National Women ’ s Law Center (“NWLC”) and thirty-five additional organizations, in support of the Director, counter that public accommodation laws such as CADA guard against real-world harms caused by excluding certain groups from public accommodations. Brief of Amici Curiae The National Women’s Law Center et al. (“NWLC” ) , in Support of Respondent at 12. NWLC argues that these laws reflect society’s recognition of discrimination and perpetuated economic and social inequality. Id. at 6. NWLC notes that discriminating against people in public accommodations stigmatizes them and deprives them of individual dignity. Id. at 13.

Local governments and mayors (collectively “Local Governments”), in support of the Director, claim that enforcing CADA allows local communities to become diverse and pluralistic. Brief of Amici Curiae Local Governments and Mayors (“Local Governments”) , in Support of Respondent at 5. Local Governments contend that discrimination not only impedes individuals who face discrimination from accessing goods and services, but also harms their well-being and economic security. Id. at 6. Local Governments argue that protections under CADA ensure an equal opportunity to access services and earn a living, thereby allowing individuals who are discriminated against to fully participate in public life. Id. at 4. Furthermore, Local Governments argue that CADA would benefit society as a whole by improving business performance and the economy due to increased economic activities of the individuals who experience discrimination. Id. at 14.

Conclusion

Written by:.

Gigi Scerbo

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Nelson Tebbe for his guidance and insights into this case.

Additional Resources

- Peter Brown, Can a Web Designer Refuse to Build a Gay Marriage Website ? , New York Law Journal (Nov. 7, 2022).

- Samuel E. Ferguson, Mixed Messaging: Previewing 303 Creative and its Place in Current Free Speech Jurisprudence , Minnesota Law Review (Nov. 1, 2022).

- Christopher Jackson, Supreme Court Poised to Issue Blockbuster Decision on Free Speech , JD Supra (Nov. 17, 2022).

- Michael Smith, Column: Supreme Court Case a Unique Conflict of First, 14th Amendments , The Pilot (Nov. 5, 2022).

Web Designer’s Free Speech Supreme Court Victory Is a Win for All

In 303 Creative v. Elenis , the US Supreme Court prohibited Colorado from forcing Lorie Smith to create a message that contradicted her beliefs. Some progressives have criticized the decision—not because of the legal principles it enforced, but because of Smith’s specific beliefs at issue.

The court ruled the government may not compel Smith to endorse same-sex marriage. But it did so because of fundamental free speech tenets that benefit all of us, regardless of our views on same-sex marriage or any other issue.

Our First Amendment operates under a Golden Rule: “Do unto speech you oppose as to speech you support.” If we don’t protect the speech we loathe, we can’t protect the speech we love. The 303 Creative decision reaffirms this bedrock principle. And, following a long line of cases, it rejects government efforts to compel speech or coerce ideological conformity.

In 1943, the American Civil Liberties Union represented Jehovah’s Witnesses in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette . The state sought to compel schoolchildren to salute the American flag to instill national unity. But, even at the height of World War II, the court held that the First Amendment barred this compelled speech, declaring that “if there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official … can prescribe what shall be orthodox” or “force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

That fixed star protects all views, whether popular and majoritarian or disfavored and contrarian. And, as Barnette said, it shields “the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order.” After all, today’s heresies are sometimes tomorrow’s orthodoxies.

Colorado acknowledged that Smith, a website and graphic designer, customizes each website she creates—combining traditional art with technical elements to express herself through online works of art. Smith wants to create custom wedding websites consistent with her belief that marriage is the union of husband and wife.

Colorado also agreed Smith has always been intentional about ensuring the messages she creates align with her personal values. She declines to create messages that promote certain political views or that disparage other people, including those who identify as LGBTQ. The messages she will not express remain constant, no matter who asks her.

As Colorado stipulated, Smith is “willing to work with all people regardless of … sexual orientation.” Her decisions about what to create turn on the message she’s communicating, never the person requesting it. That means Smith designs websites for everyone, including her LGBTQ clients, so long as the message she is asked to create is consistent with her beliefs.

Colorado additionally admitted that thousands of other website designers create custom websites. And the lower appellate court found same-sex couples have no problem accessing websites to celebrate their weddings. Beyond conceding these critical facts, Colorado agreed with the central constitutional principle at stake: The government may not “force[] a speaker to convey the government’s ideological message.”

Given these concessions, you might wonder why this case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Colorado still tried to commandeer Smith’s speech, demanding she create and publish custom websites celebrating a view of marriage that violated her beliefs. Back in Barnette , the Supreme Court condemned this type of compulsion as an invasion of “the sphere of intellect and spirit.”

It’s also antithetical to our democratic form of government. As the appellate court put it, Colorado’s goal was the shockingly anti-democratic one of “excising certain ideas or viewpoints” the state disliked “from the public dialogue.”

Fortunately, in 303 Creative , the Supreme Court rejected Colorado’s unconstitutional efforts, declaring it violated the First Amendment by “us[ing] its law to compel” Smith “to create speech she does not believe.” The court confirmed “the Constitution’s commitment to the freedom of speech means all of us will encounter ideas we consider unattractive, misguided, or even hurtful. But tolerance, not coercion, is our Nation’s answer.”

Consistent with the free speech Golden Rule, this decision ensures that an LGBTQ website designer can’t be forced to create a website criticizing same-sex marriage. But this case also protects speech far beyond the marriage context. A Democratic artist need not design posters promoting the Republican Party, nor must a videographer who supports Roe v. Wade film a pro-life rally.

Consider the consequences if the Supreme Court had ruled the opposite way. The court framed the legal question the case posed as “whether applying a public accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

The court’s ruling safeguards free speech rights while ensuring nondiscrimination laws remain firmly in place. States may—and should—continue to outlaw denials of goods or services based on a protected classification.

As Colorado itself stipulated, Smith’s websites constitute expression that she creates—she selects her projects based on the message, not who requests it. The Supreme Court rightly re-affirmed that the government may not compel any of us to say things we don’t believe.

That’s the beauty of free speech. It allows all of us to discuss our common ground, debate our differences, and pursue our varying visions of truth and justice free from government compulsion.

The case is 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis , US, No. 21-476, 6/30/23.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

Kristen Waggoner is CEO and president of Alliance Defending Freedom and argued 303 Creative v. Elenis before the US Supreme Court on behalf of Lorie Smith.

Nadine Strossen is a past president of the American Civil Liberties Union and senior fellow at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn about bloomberg law.

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Freedom of Speech

[ Editor’s Note: The following new entry by Jeffrey W. Howard replaces the former entry on this topic by the previous author. ]

Human beings have significant interests in communicating what they think to others, and in listening to what others have to say. These interests make it difficult to justify coercive restrictions on people’s communications, plausibly grounding a moral right to speak (and listen) to others that is properly protected by law. That there ought to be such legal protections for speech is uncontroversial among political and legal philosophers. But disagreement arises when we turn to the details. What are the interests or values that justify this presumption against restricting speech? And what, if anything, counts as an adequate justification for overcoming the presumption? This entry is chiefly concerned with exploring the philosophical literature on these questions.

The entry begins by distinguishing different ideas to which the term “freedom of speech” can refer. It then reviews the variety of concerns taken to justify freedom of speech. Next, the entry considers the proper limits of freedom of speech, cataloging different views on when and why restrictions on communication can be morally justified, and what considerations are relevant when evaluating restrictions. Finally, it considers the role of speech intermediaries in a philosophical analysis of freedom of speech, with special attention to internet platforms.

1. What is Freedom of Speech?

2.1 listener theories, 2.2 speaker theories, 2.3 democracy theories, 2.4 thinker theories, 2.5 toleration theories, 2.6 instrumental theories: political abuse and slippery slopes, 2.7 free speech skepticism, 3.1 absoluteness, coverage, and protection, 3.2 the limits of free speech: external constraints, 3.3 the limits of free speech: internal constraints, 3.4 proportionality: chilling effects and political abuse, 3.5 necessity: the counter-speech alternative, 4. the future of free speech theory: platform ethics, other internet resources, related entries.

In the philosophical literature, the terms “freedom of speech”, “free speech”, “freedom of expression”, and “freedom of communication” are mostly used equivalently. This entry will follow that convention, notwithstanding the fact that these formulations evoke subtly different phenomena. For example, it is widely understood that artistic expressions, such as dancing and painting, fall within the ambit of this freedom, even though they don’t straightforwardly seem to qualify as speech , which intuitively connotes some kind of linguistic utterance (see Tushnet, Chen, & Blocher 2017 for discussion). Still, they plainly qualify as communicative activity, conveying some kind of message, however vague or open to interpretation it may be.

Yet the extension of “free speech” is not fruitfully specified through conceptual analysis alone. The quest to distinguish speech from conduct, for the purpose of excluding the latter from protection, is notoriously thorny (Fish 1994: 106), despite some notable attempts (such as Greenawalt 1989: 58ff). As John Hart Ely writes concerning Vietnam War protesters who incinerated their draft cards, such activity is “100% action and 100% expression” (1975: 1495). It is only once we understand why we should care about free speech in the first place—the values it instantiates or serves—that we can evaluate whether a law banning the burning of draft cards (or whatever else) violates free speech. It is the task of a normative conception of free speech to offer an account of the values at stake, which in turn can illuminate the kinds of activities wherein those values are realized, and the kinds of restrictions that manifest hostility to those values. For example, if free speech is justified by the value of respecting citizens’ prerogative to hear many points of view and to make up their own minds, then banning the burning of draft cards to limit the views to which citizens will be exposed is manifestly incompatible with that purpose. If, in contrast, such activity is banned as part of a generally applied ordinance restricting fires in public, it would likely raise no free-speech concerns. (For a recent analysis of this issue, see Kramer 2021: 25ff).

Accordingly, the next section discusses different conceptions of free speech that arise in the philosophical literature, each oriented to some underlying moral or political value. Before turning to the discussion of those conceptions, some further preliminary distinctions will be useful.

First, we can distinguish between the morality of free speech and the law of free speech. In political philosophy, one standard approach is to theorize free speech as a requirement of morality, tracing the implications of such a theory for law and policy. Note that while this is the order of justification, it need not be the order of investigation; it is perfectly sensible to begin by studying an existing legal protection for speech (such as the First Amendment in the U.S.) and then asking what could justify such a protection (or something like it).

But of course morality and law can diverge. The most obvious way they can diverge is when the law is unjust. Existing legal protections for speech, embodied in the positive law of particular jurisdictions, may be misguided in various ways. In other words, a justified legal right to free speech, and the actual legal right to free speech in the positive law of a particular jurisdiction, can come apart. In some cases, positive legal rights might protect too little speech. For example, some jurisdictions’ speech laws make exceptions for blasphemy, such that criminalizing blasphemy does not breach the legal right to free speech within that legal system. But clearly one could argue that a justified legal right to free speech would not include any such exception. In other cases, positive legal rights might perhaps protect too much speech. Consider the fact that, as a matter of U.S. constitutional precedent, the First Amendment broadly protects speech that expresses or incites racial or religious hatred. Plainly we could agree that this is so as a matter of positive law while disagreeing about whether it ought to be so. (This is most straightforwardly true if we are legal positivists. These distinctions are muddied by moralistic theories of constitutional interpretation, which enjoin us to interpret positive legal rights in a constitutional text partly through the prism of our favorite normative political theory; see Dworkin 1996.)

Second, we can distinguish rights-based theories of free speech from non-rights-based theories. For many liberals, the legal right to free speech is justified by appealing to an underlying moral right to free speech, understood as a natural right held by all persons. (Some use the term human right equivalently—e.g., Alexander 2005—though the appropriate usage of that term is contested.) The operative notion of a moral right here is that of a claim-right (to invoke the influential analysis of Hohfeld 1917); it thereby correlates to moral duties held by others (paradigmatically, the state) to respect or protect the right. Such a right is natural in that it exerts normative force independently of whether anyone thinks it does, and regardless of whether it is codified into the law. A tyrannical state that imprisons dissidents acts unjustly, violating moral rights, even if there is no legal right to freedom of expression in its legal system.

For others, the underlying moral justification for free speech law need not come in the form of a natural moral right. For example, consequentialists might favor a legal right to free speech (on, e.g., welfare-maximizing grounds) without thinking that it tracks any underlying natural right. Or consider democratic theorists who have defended legal protections for free speech as central to democracy. Such theorists may think there is an underlying natural moral right to free speech, but they need not (especially if they hold an instrumental justification for democracy). Or consider deontologists who have argued that free speech functions as a kind of side-constraint on legitimate state action, requiring that the state always justify its decisions in a manner that respects citizens’ autonomy (Scanlon 1972). This theory does not cast free speech as a right, but rather as a principle that forbids the creation of laws that restrict speech on certain grounds. In the Hohfeldian analysis (Hohfeld 1917), such a principle may be understood as an immunity rather than a claim-right (Scanlon 2013: 402). Finally, some “minimalists” (to use a designation in Cohen 1993) favor legal protection for speech principally in response to government malice, corruption, and incompetence (see Schauer 1982; Epstein 1992; Leiter 2016). Such theorists need not recognize any fundamental moral right, either.

Third, among those who do ground free speech in a natural moral right, there is scope for disagreement about how tightly the law should mirror that right (as with any right; see Buchanan 2013). It is an open question what the precise legal codification of the moral right to free speech should involve. A justified legal right to freedom of speech may not mirror the precise contours of the natural moral right to freedom of speech. A raft of instrumental concerns enters the downstream analysis of what any justified legal right should look like; hence a defensible legal right to free speech may protect more speech (or indeed less speech) than the underlying moral right that justifies it. For example, even if the moral right to free speech does not protect so-called hate speech, such speech may still merit legal protection in the final analysis (say, because it would be too risky to entrust states with the power to limit those communications).

2. Justifying Free Speech

I will now examine several of the morally significant considerations taken to justify freedom of expression. Note that while many theorists have built whole conceptions of free speech out of a single interest or value alone, pluralism in this domain remains an option. It may well be that a plurality of interests serves to justify freedom of expression, properly understood (see, influentially, Emerson 1970 and Cohen 1993).

Suppose a state bans certain books on the grounds that it does not want us to hear the messages or arguments contained within them. Such censorship seems to involve some kind of insult or disrespect to citizens—treating us like children instead of adults who have a right to make up our own minds. This insight is fundamental in the free speech tradition. On this view, the state wrongs citizens by arrogating to itself the authority to decide what messages they ought to hear. That is so even if the state thinks that the speech will cause harm. As one author puts it,

the government may not suppress speech on the ground that the speech is likely to persuade people to do something that the government considers harmful. (Strauss 1991: 335)

Why are restrictions on persuasive speech objectionable? For some scholars, the relevant wrong here is a form of disrespect for citizens’ basic capacities (Dworkin 1996: 200; Nagel 2002: 44). For others, the wrong here inheres in a violation of the kind of relationship the state should have with its people: namely, that it should always act from a view of them as autonomous, and so entitled to make up their own minds (Scanlon 1972). It would simply be incompatible with a view of ourselves as autonomous—as authors of our own lives and choices—to grant the state the authority to pre-screen which opinions, arguments, and perspectives we should be allowed to think through, allowing us access only to those of which it approves.

This position is especially well-suited to justify some central doctrines of First Amendment jurisprudence. First, it justifies the claim that freedom of expression especially implicates the purposes with which the state acts. There are all sorts of legitimate reasons why the state might restrict speech (so-called “time, place, and manner” restrictions)—for example, noise curfews in residential neighborhoods, which do not raise serious free speech concerns. Yet when the state restricts speech with the purpose of manipulating the communicative environment and controlling the views to which citizens are exposed, free speech is directly affronted (Rubenfeld 2001; Alexander 2005; Kramer 2021). To be sure, purposes are not all that matter for free speech theory. For example, the chilling effects of otherwise justified speech regulations (discussed below) are seldom intended. But they undoubtedly matter.

Second, this view justifies the related doctrines of content neutrality and viewpoint neutrality (see G. Stone 1983 and 1987) . Content neutrality is violated when the state bans discussion of certain topics (“no discussion of abortion”), whereas viewpoint neutrality is violated when the state bans advocacy of certain views (“no pro-choice views may be expressed”). Both affront free speech, though viewpoint-discrimination is especially egregious and so even harder to justify. While listener autonomy theories are not the only theories that can ground these commitments, they are in a strong position to account for their plausibility. Note that while these doctrines are central to the American approach to free speech, they are less central to other states’ jurisprudence (see A. Stone 2017).

Third, this approach helps us see that free speech is potentially implicated whenever the state seeks to control our thoughts and the processes through which we form beliefs. Consider an attempt to ban Marx’s Capital . As Marx is deceased, he is probably not wronged through such censorship. But even if one held idiosyncratic views about posthumous rights, such that Marx were wronged, it would be curious to think this was the central objection to such censorship. Those with the gravest complaint would be the living adults who have the prerogative to read the book and make up their own minds about it. Indeed free speech may even be implicated if the state banned watching sunsets or playing video games on the grounds that is disapproved of the thoughts to which such experiences might give rise (Alexander 2005: 8–9; Kramer 2021: 22).

These arguments emphasize the noninstrumental imperative of respecting listener autonomy. But there is an instrumental version of the view. Our autonomy interests are not merely respected by free speech; they are promoted by an environment in which we learn what others have to say. Our interests in access to information is served by exposure to a wide range of viewpoints about both empirical and normative issues (Cohen 1993: 229), which help us reflect on what goals to choose and how best to pursue them. These informational interests are monumental. As Raz suggests, if we had to choose whether to express our own views on some question, or listen to the rest of humanity’s views on that question, we would choose the latter; it is our interest as listeners in the public good of a vibrant public discourse that, he thinks, centrally justifies free speech (1991).

Such an interest in acquiring justified beliefs, or in accessing truth, can be defended as part of a fully consequentialist political philosophy. J.S. Mill famously defends free speech instrumentally, appealing to its epistemic benefits in On Liberty . Mill believes that, given our fallibility, we should routinely keep an open mind as to whether a seemingly false view may actually be true, or at least contain some valuable grain of truth. And even where a proposition is manifestly false, there is value in allowing its expression so that we can better apprehend why we take it to be false (1859: chapter 2), enabled through discursive conflict (cf. Simpson 2021). Mill’s argument focuses especially on the benefits to audiences:

It is is not on the impassioned partisan, it is on the calmer and more disinterested bystander, that this collision of opinions works its salutary effect. (1859: chapter 2, p. 94)

These views are sometimes associated with the idea of a “marketplace of ideas”, whereby the open clash of views inevitably leads to the correct ones winning out in debate. Few in the contemporary literature holds such a strong teleological thesis about the consequences of unrestricted debate (e.g., see Brietzke 1997; cf. Volokh 2011). Much evidence from behavioral economics and social psychology, as well as insights about epistemic injustice from feminist epistemology, strongly suggest that human beings’ rational powers are seriously limited. Smug confidence in the marketplace of ideas belies this. Yet it is doubtful that Mill held such a strong teleological thesis (Gordon 1997). Mill’s point was not that unrestricted discussion necessarily leads people to acquire the truth. Rather, it is simply the best mechanism available for ascertaining the truth, relative to alternatives in which some arbiter declares what he sees as true and suppresses what he sees as false (see also Leiter 2016).

Note that Mill’s views on free speech in chapter 2 in On Liberty are not simply the application of the general liberty principle defended in chapter 1 of that work; his view is not that speech is anodyne and therefore seldom runs afoul of the harm principle. The reason a separate argument is necessary in chapter 2 is precisely that he is carving out a partial qualification of the harm principle for speech (on this issue see Jacobson 2000, Schauer 2011b, and Turner 2014). On Mill’s view, plenty of harmful speech should still be allowed. Imminently dangerous speech, where there is no time for discussion before harm eventuates, may be restricted; but where there is time for discussion, it must be allowed. Hence Mill’s famous example that vociferous criticism of corn dealers as

starvers of the poor…ought to be unmolested when simply circulated through the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered orally to an excited mob assembled before the house of a corn dealer. (1859: chapter 3, p. 100)

The point is not that such speech is harmless; it’s that the instrumental benefits of permitting its expressions—and exposing its falsehood through public argument—justify the (remaining) costs.

Many authors have unsurprisingly argued that free speech is justified by our interests as speakers . This family of arguments emphasizes the role of speech in the development and exercise of our personal autonomy—our capacity to be the reflective authors of our own lives (Baker 1989; Redish 1982; Rawls 2005). Here an emphasis on freedom of expression is apt; we have an “expressive interest” (Cohen 1993: 224) in declaring our views—about the good life, about justice, about our identity, and about other aspects of the truth as we see it.

Our interests in self-expression may not always depend on the availability of a willing audience; we may have interests simply in shouting from the rooftops to declare who we are and what we believe, regardless of who else hears us. Hence communications to oneself—for example, in a diary or journal—are plausibly protected from interference (Redish 1992: 30–1; Shiffrin 2014: 83, 93; Kramer 2021: 23).

Yet we also have distinctive interests in sharing what we think with others. Part of how we develop our conceptions of the good life, forming judgments about how to live, is precisely through talking through the matter with others. This “deliberative interest” in directly served through opportunities to tell others what we think, so that we can learn from their feedback (Cohen 1993). Such encounters also offer opportunities to persuade others to adopt our views, and indeed to learn through such discussions who else already shares our views (Raz 1991).

Speech also seems like a central way in which we develop our capacities. This, too, is central to J.S. Mill’s defense of free speech, enabling people to explore different perspectives and points of view (1859). Hence it seems that when children engage in speech, to figure out what they think and to use their imagination to try out different ways of being in the world, they are directly engaging this interest. That explains the intuition that children, and not just adults, merit at least some protection under a principle of freedom of speech.

Note that while it is common to refer to speaker autonomy , we could simply refer to speakers’ capacities. Some political liberals hold that an emphasis on autonomy is objectionably Kantian or otherwise perfectionist, valorizing autonomy as a comprehensive moral ideal in a manner that is inappropriate for a liberal state (Cohen 1993: 229; Quong 2011). For such theorists, an undue emphasis on autonomy is incompatible with ideals of liberal neutrality toward different comprehensive conceptions of the good life (though cf. Shiffrin 2014: 81).

If free speech is justified by the importance of our interests in expressing ourselves, this justifies negative duties to refrain from interfering with speakers without adequate justification. Just as with listener theories, a strong presumption against content-based restrictions, and especially against viewpoint discrimination, is a clear requirement of the view. For the state to restrict citizens’ speech on the grounds that it disfavors what they have to say would affront the equal freedom of citizens. Imagine the state were to disallow the expression of Muslim or Jewish views, but allow the expression of Christian views. This would plainly transgress the right to freedom of expression, by valuing certain speakers’ interests in expressing themselves over others.

Many arguments for the right to free speech center on its special significance for democracy (Cohen 1993; Heinze 2016: Heyman 2009; Sunstein 1993; Weinstein 2011; Post 1991, 2009, 2011). It is possible to defend free speech on the noninstrumental ground that it is necessary to respect agents as democratic citizens. To restrict citizens’ speech is to disrespect their status as free and equal moral agents, who have a moral right to debate and decide the law for themselves (Rawls 2005).

Alternatively (or additionally), one can defend free speech on the instrumental ground that free speech promotes democracy, or whatever values democracy is meant to serve. So, for example, suppose the purpose of democracy is the republican one of establishing a state of non-domination between relationally egalitarian citizens; free speech can be defended as promoting that relation (Whitten 2022; Bonotti & Seglow 2022). Or suppose that democracy is valuable because of its role in promoting just outcomes (Arneson 2009) or tending to track those outcomes in a manner than is publicly justifiable (Estlund 2008) or is otherwise epistemically valuable (Landemore 2013).

Perhaps free speech doesn’t merely respect or promote democracy; another framing is that it is constitutive of it (Meiklejohn 1948, 1960; Heinze 2016). As Rawls says: “to restrict or suppress free political speech…always implies at least a partial suspension of democracy” (2005: 254). On this view, to be committed to democracy just is , in part, to be committed to free speech. Deliberative democrats famously contend that voting merely punctuates a larger process defined by a commitment to open deliberation among free and equal citizens (Gutmann & Thompson 2008). Such an unrestricted discussion is marked not by considerations of instrumental rationality and market forces, but rather, as Habermas puts it, “the unforced force of the better argument” (1992 [1996: 37]). One crucial way in which free speech might be constitutive of democracy is if it serves as a legitimation condition . On this view, without a process of open public discourse, the outcomes of the democratic decision-making process lack legitimacy (Dworkin 2009, Brettschneider 2012: 75–78, Cohen 1997, and Heinze 2016).

Those who justify free speech on democratic grounds may view this as a special application of a more general insight. For example, Scanlon’s listener theory (discussed above) contends that the state must always respect its citizens as capable of making up their own minds (1972)—a position with clear democratic implications. Likewise, Baker is adamant that both free speech and democracy are justified by the same underlying value of autonomy (2009). And while Rawls sees the democratic role of free speech as worthy of emphasis, he is clear that free speech is one of several basic liberties that enable the development and exercise of our moral powers: our capacities for a sense of justice and for the rational pursuit a lifeplan (2005). In this way, many theorists see the continuity between free speech and our broader interests as moral agents as a virtue, not a drawback (e.g., Kendrick 2017).

Even so, some democracy theorists hold that democracy has a special role in a theory of free speech, such that political speech in particular merits special protection (for an overview, see Barendt 2005: 154ff). One consequence of such views is that contributions to public discourse on political questions merit greater protection under the law (Sunstein 1993; cf. Cohen 1993: 227; Alexander 2005: 137–8). For some scholars, this may reflect instrumental anxieties about the special danger that the state will restrict the political speech of opponents and dissenters. But for others, an emphasis on political speech seems to reflect a normative claim that such speech is genuinely of greater significance, meriting greater protection, than other kinds of speech.

While conventional in the free speech literature, it is artificial to separate out our interests as speakers, listeners, and democratic citizens. Communication, and the thinking that feeds into it and that it enables, invariably engages our interests and activities across all these capacities. This insight is central to Seana Shiffrin’s groundbreaking thinker-based theory of freedom of speech, which seeks to unify the range of considerations that have informed the traditional theories (2014). Like other theories (e.g., Scanlon 1978, Cohen 1993), Shiffrin’s theory is pluralist in the range of interests it appeals to. But it offers a unifying framework that explains why this range of interests merits protection together.

On Shiffrin’s view, freedom of speech is best understood as encompassing both freedom of communication and freedom of thought, which while logically distinct are mutually reinforcing and interdependent (Shiffrin 2014: 79). Shiffrin’s account involves several profound claims about the relation between communication and thought. A central contention is that “free speech is essential to the development, functioning, and operation of thinkers” (2014: 91). This is, in part, because we must often externalize our ideas to articulate them precisely and hold them at a distance where we can evaluate them (p. 89). It is also because we work out what we think largely by talking it through with others. Such communicative processes may be monological, but they are typically dialogical; speaker and listener interests are thereby mutually engaged in an ongoing manner that cannot be neatly disentangled, as ideas are ping-ponged back and forth. Moreover, such discussions may concern democratic politics—engaging our interests as democratic citizens—but of course they need not. Aesthetics, music, local sports, the existence of God—these all are encompassed (2014: 92–93). Pace prevailing democratic theories,

One’s thoughts about political affairs are intrinsically and ex ante no more and no less central to the human self than thoughts about one’s mortality or one’s friends. (Shiffrin 2014: 93)

The other central aspect of Shiffrin’s view appeals to the necessity of communication for successfully exercising our moral agency. Sincere communication enables us

to share needs, emotions, intentions, convictions, ambitions, desires, fantasies, disappointments, and judgments. Thereby, we are enabled to form and execute complex cooperative plans, to understand one another, to appreciate and negotiate around our differences. (2014: 1)

Without clear and precise communication of the sort that only speech can provide, we cannot cooperate to discharge our collective obligations. Nor can we exercise our normative powers (such as consenting, waiving, or promising). Our moral agency thus depends upon protected channels through which we can relay our sincere thoughts to one another. The central role of free speech is to protect those channels, by ensuring agents are free to share what they are thinking without fear of sanction.

The thinker-based view has wide-ranging normative implications. For example, by emphasizing the continuity of speech and thought (a connection also noted in Macklem 2006 and Gilmore 2011), Shiffrin’s view powerfully explains the First Amendment doctrine that compelled speech also constitutes a violation of freedom of expression. Traditional listener- and speaker-focused theories seemingly cannot explain what is fundamentally objectionable with forcing someone to declare a commitment to something, as with children compelled to pledge allegiance to the American flag ( West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette 1943). “What seems most troubling about the compelled pledge”, Shiffrin writes,

is that the motive behind the regulation, and its possible effect, is to interfere with the autonomous thought processes of the compelled speaker. (2014: 94)

Further, Shiffrin’s view explains why a concern for free speech does not merely correlate to negative duties not to interfere with expression; it also supports positive responsibilities on the part of the state to educate citizens, encouraging and supporting their development and exercise as thinking beings (2014: 107).

Consider briefly one final family of free speech theories, which appeal to the role of toleration or self-restraint. On one argument, freedom of speech is important because it develops our character as liberal citizens, helping us tame our illiberal impulses. The underlying idea of Lee Bollinger’s view is that liberalism is difficult; we recurrently face temptation to punish those who hold contrary views. Freedom of speech helps us to practice the general ethos of toleration in a manner than fortifies our liberal convictions (1986). Deeply offensive speech, like pro-Nazi speech, is protected precisely because toleration in these enormously difficult cases promotes “a general social ethic” of toleration more generally (1986: 248), thereby restraining unjust exercises of state power overall. This consequentialist argument treats the protection of offensive speech not as a tricky borderline case, but as “integral to the central functions of the principle of free speech” (1986: 133). It is precisely because tolerating evil speech involves “extraordinary self-restraint” (1986: 10) that it works its salutary effects on society generally.

The idea of self-restraint arises, too, in Matthew Kramer’s recent defense of free speech. Like listener theories, Kramer’s strongly deontological theory condemns censorship aimed at protecting audiences from exposure to misguided views. At the core of his theory is the thesis that the state’s paramount moral responsibility is to furnish the social conditions that serve the development and maintenance of citizens’ self-respect and respect for others. The achievement of such an ethically resilient citizenry, on Kramer’s view, has the effect of neutering the harmfulness of countless harmful communications. “Securely in a position of ethical strength”, the state “can treat the wares of pornographers and the maunderings of bigots as execrable chirps that are to be endured with contempt” (Kramer 2021: 147). In contrast, in a society where the state has failed to do its duty of inculcating a robust liberal-egalitarian ethos, the communication of illiberal creeds may well pose a substantial threat. Yet for the state then to react by banning such speech is

overweening because with them the system’s officials take control of communications that should have been defused (through the system’s fulfillment of its moral obligations) without prohibitory or preventative impositions. (2021: 147)

(One might agree with Kramer that this is so, but diverge by arguing that the state—having failed in its initial duty—ought to take measures to prevent the harms that flow from that failure.)

These theories are striking in that they assume that a chief task of free speech theory is to explain why harmful speech ought to be protected. This is in contrast to those who think that the chief task of free speech theory is to explain our interests in communicating with others, treating the further issue of whether (wrongfully) harmful communications should be protected as an open question, with different reasonable answers available (Kendrick 2017). In this way, toleration theories—alongside a lot of philosophical work on free speech—seem designed to vindicate the demanding American legal position on free speech, one unshared by virtually all other liberal democracies.

One final family of arguments for free speech appeals to the danger of granting the state powers it may abuse. On this view, we protect free speech chiefly because if we didn’t, it would be far easier for the state to silence its political opponents and enact unjust policies. On this view, a state with censorial powers is likely to abuse them. As Richard Epstein notes, focusing on the American case,

the entire structure of federalism, divided government, and the system of checks and balances at the federal level shows that the theme of distrust has worked itself into the warp and woof of our constitutional structure.

“The protection of speech”, he writes, “…should be read in light of these political concerns” (Epstein 1992: 49).

This view is not merely a restatement of the democracy theory; it does not affirm free speech as an element of valuable self-governance. Nor does it reduce to the uncontroversial thought that citizens need freedom of speech to check the behavior of fallible government agents (Blasi 1977). One need not imagine human beings to be particularly sinister to insist (as democracy theorists do) that the decisions of those entrusted with great power be subject to public discussion and scrutiny. The argument under consideration here is more pessimistic about human nature. It is an argument about the slippery slope that we create even when enacting (otherwise justified) speech restrictions; we set an unacceptable precedent for future conduct by the state (see Schauer 1985). While this argument is theoretical, there is clearly historical evidence for it, as in the manifold cases in which bans on dangerous sedition were used to suppress legitimate war protest. (For a sweeping canonical study of the uses and abuses of speech regulations during wartime, with a focus on U.S. history, see G. Stone 2004.)

These instrumental concerns could potentially justify the legal protection for free speech. But they do not to attempt to justify why we should care about free speech as a positive moral ideal (Shiffrin 2014: 83n); they are, in Cohen’s helpful terminology, “minimalist” rather than “maximalist” (Cohen 1993: 210). Accordingly, they cannot explain why free speech is something that even the most trustworthy, morally competent administrations, with little risk of corruption or degeneration, ought to respect. Of course, minimalists will deny that accounting for speech’s positive value is a requirement of a theory of free speech, and that critiquing them for this omission begs the question.

Pluralists may see instrumental concerns as valuably supplementing or qualifying noninstrumental views. For example, instrumental concerns may play a role in justifying deviations between the moral right to free communication, on the one hand, and a properly specified legal right to free communication, on the other. Suppose that there is no moral right to engage in certain forms of harmful expression (such as hate speech), and that there is in fact a moral duty to refrain from such expression. Even so, it does not follow automatically that such a right ought to be legally enforced. Concerns about the dangers of granting the state such power plausibly militate against the enforcement of at least some of our communicative duties—at least in those jurisdictions that lack robust and competently administered liberal-democratic safeguards.

This entry has canvassed a range of views about what justifies freedom of expression, with particular attention to theories that conceive free speech as a natural moral right. Clearly, the proponents of such views believe that they succeed in this justificatory effort. But others dissent, doubting that the case for a bona fide moral right to free speech comes through. Let us briefly note the nature of this challenge from free speech skeptics , exploring a prominent line of reply.

The challenge from skeptics is generally understood as that of showing that free speech is a special right . As Leslie Kendrick notes,

the term “special right” generally requires that a special right be entirely distinct from other rights and activities and that it receive a very high degree of protection. (2017: 90)

(Note that this usage is not to be confused from the alternative usage of “special right”, referring to conditional rights arising out of particular relationships; see Hart 1955.)

Take each aspect in turn. First, to vindicate free speech as a special right, it must serve some distinctive value or interest (Schauer 2015). Suppose free speech were just an implication of a general principle not to interfere in people’s liberty without justification. As Joel Feinberg puts it, “Liberty should be the norm; coercion always needs some special justification” (1984: 9). In such a case, then while there still might be contingent, historical reasons to single speech out in law as worthy of protection (Alexander 2005: 186), such reasons would not track anything especially distinctive about speech as an underlying moral matter. Second, to count as a special right, free speech must be robust in what it protects, such that only a compelling justification can override it (Dworkin 2013: 131). This captures the conviction, prominent among American constitutional theorists, that “any robust free speech principle must protect at least some harmful speech despite the harm it may cause” (Schauer 2011b: 81; see also Schauer 1982).

If the task of justifying a moral right to free speech requires surmounting both hurdles, it is a tall order. Skeptics about a special right to free speech doubt that the order can be met, and so deny that a natural moral right to freedom of expression can be justified (Schauer 2015; Alexander & Horton 1983; Alexander 2005; Husak 1985). But these theorists may be demanding too much (Kendrick 2017). Start with the claim that free speech must be distinctive. We can accept that free speech be more than simply one implication of a general presumption of liberty. But need it be wholly distinctive? Consider the thesis that free speech is justified by our autonomy interests—interests that justify other rights such as freedom of religion and association. Is it a problem if free speech is justified by interests that are continuous with, or overlap with, interests that justify other rights? Pace the free speech skeptics, maybe not. So long as such claims deserve special recognition, and are worth distinguishing by name, this may be enough (Kendrick 2017: 101). Many of the views canvassed above share normative bases with other important rights. For example, Rawls is clear that he thinks all the basic liberties constitute

essential social conditions for the adequate development and full exercise of the two powers of moral personality over a complete life. (Rawls 2005: 293)

The debate, then, is whether such a shared basis is a theoretical virtue (or at least theoretically unproblematic) or whether it is a theoretical vice, as the skeptics avow.

As for the claim that free speech must be robust, protecting harmful speech, “it is not necessary for a free speech right to protect harmful speech in order for it to be called a free speech right” (Kendrick 2017: 102). We do not tend to think that religious liberty must protect harmful religious activities for it to count as a special right. So it would be strange to insist that the right to free speech must meet this burden to count as a special right. Most of the theorists mentioned above take themselves to be offering views that protect quite a lot of harmful speech. Yet we can question whether this feature is a necessary component of their views, or whether we could imagine variations without this result.

3. Justifying Speech Restrictions

When, and why, can restrictions on speech be justified? It is common in public debate on free speech to hear the provocative claim that free speech is absolute . But the plausibility of such a claim depends on what is exactly meant by it. If understood to mean that no communications between humans can ever be restricted, such a view is held by no one in the philosophical debate. When I threaten to kill you unless you hand me your money; when I offer to bribe the security guard to let me access the bank vault; when I disclose insider information that the company in which you’re heavily invested is about to go bust; when I defame you by falsely posting online that you’re a child abuser; when I endanger you by labeling a drug as safe despite its potentially fatal side-effects; when I reveal your whereabouts to assist a murderer intent on killing you—across all these cases, communications may be uncontroversially restricted. But there are different views as to why.

To help organize such views, consider a set of distinctions influentially defended by Schauer (from 1982 onward). The first category involves uncovered speech : speech that does not even presumptively fall within the scope of a principle of free expression. Many of the speech-acts just canvassed, such as the speech involved in making a threat or insider training, plausibly count as uncovered speech. As the U.S. Supreme Court has said of fighting words (e.g., insults calculated to provoke a street fight),

such utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality. ( Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire 1942)