Elements of Creative Writing

J.D. Schraffenberger, University of Northern Iowa

Rachel Morgan, University of Northern Iowa

Grant Tracey, University of Northern Iowa

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9780915996179

Publisher: University of Northern Iowa

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Robert Moreira, Lecturer III, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 3/21/24

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell, content is accurate, error free and unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book is relevant and up-to-date.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is clear and easy to understand.

Consistency rating: 5

I would agree that the text is consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 5

Text is modular, yes, but I would like to see the addition of a section on dramatic writing.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Topics are presented in logical, clear fashion.

Interface rating: 5

Navigation is good.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

No grammatical issues that I could see.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I'd like to see more diverse creative writing examples.

As I stated above, textbook is good except that it does not include a section on dramatic writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: One Great Way to Write a Short Story

- Chapter Two: Plotting

- Chapter Three: Counterpointed Plotting

- Chapter Four: Show and Tell

- Chapter Five: Characterization and Method Writing

- Chapter Six: Character and Dialouge

- Chapter Seven: Setting, Stillness, and Voice

- Chapter Eight: Point of View

- Chapter Nine: Learning the Unwritten Rules

- Chapter One: A Poetry State of Mind

- Chapter Two: The Architecture of a Poem

- Chapter Three: Sound

- Chapter Four: Inspiration and Risk

- Chapter Five: Endings and Beginnings

- Chapter Six: Figurative Language

- Chapter Seven: Forms, Forms, Forms

- Chapter Eight: Go to the Image

- Chapter Nine: The Difficult Simplicity of Short Poems and Killing Darlings

Creative Nonfiction

- Chapter One: Creative Nonfiction and the Essay

- Chapter Two: Truth and Memory, Truth in Memory

- Chapter Three: Research and History

- Chapter Four: Writing Environments

- Chapter Five: Notes on Style

- Chapter Seven: Imagery and the Senses

- Chapter Eight: Writing the Body

- Chapter Nine: Forms

Back Matter

- Contributors

- North American Review Staff

Ancillary Material

- University of Northern Iowa

About the Book

This free and open access textbook introduces new writers to some basic elements of the craft of creative writing in the genres of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. The authors—Rachel Morgan, Jeremy Schraffenberger, and Grant Tracey—are editors of the North American Review, the oldest and one of the most well-regarded literary magazines in the United States. They’ve selected nearly all of the readings and examples (more than 60) from writing that has appeared in NAR pages over the years. Because they had a hand in publishing these pieces originally, their perspective as editors permeates this book. As such, they hope that even seasoned writers might gain insight into the aesthetics of the magazine as they analyze and discuss some reasons this work is so remarkable—and therefore teachable. This project was supported by NAR staff and funded via the UNI Textbook Equity Mini-Grant Program.

About the Contributors

J.D. Schraffenberger is a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of two books of poems, Saint Joe's Passion and The Waxen Poor , and co-author with Martín Espada and Lauren Schmidt of The Necessary Poetics of Atheism . His other work has appeared in Best of Brevity , Best Creative Nonfiction , Notre Dame Review , Poetry East , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Rachel Morgan is an instructor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. She is the author of the chapbook Honey & Blood , Blood & Honey . Her work is included in the anthology Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in American and has appeared in the Journal of American Medical Association , Boulevard , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Grant Tracey author of three novels in the Hayden Fuller Mysteries ; the chapbook Winsome featuring cab driver Eddie Sands; and the story collection Final Stanzas , is fiction editor of the North American Review and an English professor at the University of Northern Iowa, where he teaches film, modern drama, and creative writing. Nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize, he has published nearly fifty short stories and three previous collections. He has acted in over forty community theater productions and has published critical work on Samuel Fuller and James Cagney. He lives in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Contribute to this Page

What is Creative Writing? A Key Piece of the Writer’s Toolbox

Not all writing is the same and there’s a type of writing that has the ability to transport, teach, and inspire others like no other.

Creative writing stands out due to its unique approach and focus on imagination. Here’s how to get started and grow as you explore the broad and beautiful world of creative writing!

What is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is a form of writing that extends beyond the bounds of regular professional, journalistic, academic, or technical forms of literature. It is characterized by its emphasis on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes or poetic techniques to express ideas in an original and imaginative way.

Creative writing can take on various forms such as:

- short stories

- screenplays

It’s a way for writers to express their thoughts, feelings, and ideas in a creative, often symbolic, way . It’s about using the power of words to transport readers into a world created by the writer.

5 Key Characteristics of Creative Writing

Creative writing is marked by several defining characteristics, each working to create a distinct form of expression:

1. Imagination and Creativity: Creative writing is all about harnessing your creativity and imagination to create an engaging and compelling piece of work. It allows writers to explore different scenarios, characters, and worlds that may not exist in reality.

2. Emotional Engagement: Creative writing often evokes strong emotions in the reader. It aims to make the reader feel something — whether it’s happiness, sorrow, excitement, or fear.

3. Originality: Creative writing values originality. It’s about presenting familiar things in new ways or exploring ideas that are less conventional.

4. Use of Literary Devices: Creative writing frequently employs literary devices such as metaphors, similes, personification, and others to enrich the text and convey meanings in a more subtle, layered manner.

5. Focus on Aesthetics: The beauty of language and the way words flow together is important in creative writing. The aim is to create a piece that’s not just interesting to read, but also beautiful to hear when read aloud.

Remember, creative writing is not just about producing a work of art. It’s also a means of self-expression and a way to share your perspective with the world. Whether you’re considering it as a hobby or contemplating a career in it, understanding the nature and characteristics of creative writing can help you hone your skills and create more engaging pieces .

For more insights into creative writing, check out our articles on creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree and is a degree in creative writing worth it .

Styles of Creative Writing

To fully understand creative writing , you must be aware of the various styles involved. Creative writing explores a multitude of genres, each with its own unique characteristics and techniques.

Poetry is a form of creative writing that uses expressive language to evoke emotions and ideas. Poets often employ rhythm, rhyme, and other poetic devices to create pieces that are deeply personal and impactful. Poems can vary greatly in length, style, and subject matter, making this a versatile and dynamic form of creative writing.

Short Stories

Short stories are another common style of creative writing. These are brief narratives that typically revolve around a single event or idea. Despite their length, short stories can provide a powerful punch, using precise language and tight narrative structures to convey a complete story in a limited space.

Novels represent a longer form of narrative creative writing. They usually involve complex plots, multiple characters, and various themes. Writing a novel requires a significant investment of time and effort; however, the result can be a rich and immersive reading experience.

Screenplays

Screenplays are written works intended for the screen, be it television, film, or online platforms. They require a specific format, incorporating dialogue and visual descriptions to guide the production process. Screenwriters must also consider the practical aspects of filmmaking, making this an intricate and specialized form of creative writing.

If you’re interested in this style, understanding creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree can provide useful insights.

Writing for the theater is another specialized form of creative writing. Plays, like screenplays, combine dialogue and action, but they also require an understanding of the unique dynamics of the theatrical stage. Playwrights must think about the live audience and the physical space of the theater when crafting their works.

Each of these styles offers unique opportunities for creativity and expression. Whether you’re drawn to the concise power of poetry, the detailed storytelling of novels, or the visual language of screenplays and plays, there’s a form of creative writing that will suit your artistic voice. The key is to explore, experiment, and find the style that resonates with you.

For those looking to spark their creativity, our article on creative writing prompts offers a wealth of ideas to get you started.

Importance of Creative Writing

Understanding what is creative writing involves recognizing its value and significance. Engaging in creative writing can provide numerous benefits – let’s take a closer look.

Developing Creativity and Imagination

Creative writing serves as a fertile ground for nurturing creativity and imagination. It encourages you to think outside the box, explore different perspectives, and create unique and original content. This leads to improved problem-solving skills and a broader worldview , both of which can be beneficial in various aspects of life.

Through creative writing, one can build entire worlds, create characters, and weave complex narratives, all of which are products of a creative mind and vivid imagination. This can be especially beneficial for those seeking creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree .

Enhancing Communication Skills

Creative writing can also play a crucial role in honing communication skills. It demands clarity, precision, and a strong command of language. This helps to improve your vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, making it easier to express thoughts and ideas effectively .

Moreover, creative writing encourages empathy as you often need to portray a variety of characters from different backgrounds and perspectives. This leads to a better understanding of people and improved interpersonal communication skills.

Exploring Emotions and Ideas

One of the most profound aspects of creative writing is its ability to provide a safe space for exploring emotions and ideas. It serves as an outlet for thoughts and feelings , allowing you to express yourself in ways that might not be possible in everyday conversation.

Writing can be therapeutic, helping you process complex emotions, navigate difficult life events, and gain insight into your own experiences and perceptions. It can also be a means of self-discovery , helping you to understand yourself and the world around you better.

So, whether you’re a seasoned writer or just starting out, the benefits of creative writing are vast and varied. For those interested in developing their creative writing skills, check out our articles on creative writing prompts and how to teach creative writing . If you’re considering a career in this field, you might find our article on is a degree in creative writing worth it helpful.

4 Steps to Start Creative Writing

Creative writing can seem daunting to beginners, but with the right approach, anyone can start their journey into this creative field. Here are some steps to help you start creative writing .

1. Finding Inspiration

The first step in creative writing is finding inspiration . Inspiration can come from anywhere and anything. Observe the world around you, listen to conversations, explore different cultures, and delve into various topics of interest.

Reading widely can also be a significant source of inspiration. Read different types of books, articles, and blogs. Discover what resonates with you and sparks your imagination.

For structured creative prompts, visit our list of creative writing prompts to get your creative juices flowing.

Editor’s Note : When something excites or interests you, stop and take note – it could be the inspiration for your next creative writing piece.

2. Planning Your Piece

Once you have an idea, the next step is to plan your piece . Start by outlining:

- the main points

Remember, this can serve as a roadmap to guide your writing process. A plan doesn’t have to be rigid. It’s a flexible guideline that can be adjusted as you delve deeper into your writing. The primary purpose is to provide direction and prevent writer’s block.

3. Writing Your First Draft

After planning your piece, you can start writing your first draft . This is where you give life to your ideas and breathe life into your characters.

Don’t worry about making it perfect in the first go. The first draft is about getting your ideas down on paper . You can always refine and polish your work later. And if you don’t have a great place to write that first draft, consider a journal for writing .

4. Editing and Revising Your Work

The final step in the creative writing process is editing and revising your work . This is where you fine-tune your piece, correct grammatical errors, and improve sentence structure and flow.

Editing is also an opportunity to enhance your storytelling . You can add more descriptive details, develop your characters further, and make sure your plot is engaging and coherent.

Remember, writing is a craft that improves with practice . Don’t be discouraged if your first few pieces don’t meet your expectations. Keep writing, keep learning, and most importantly, enjoy the creative process.

For more insights on creative writing, check out our articles on how to teach creative writing or creative writing activities for kids.

Tips to Improve Creative Writing Skills

Understanding what is creative writing is the first step. But how can one improve their creative writing skills? Here are some tips that can help.

Read Widely

Reading is a vital part of becoming a better writer. By immersing oneself in a variety of genres, styles, and authors, one can gain a richer understanding of language and storytelling techniques . Different authors have unique voices and methods of telling stories, which can serve as inspiration for your own work. So, read widely and frequently!

Practice Regularly

Like any skill, creative writing improves with practice. Consistently writing — whether it be daily, weekly, or monthly — helps develop your writing style and voice . Using creative writing prompts can be a fun way to stimulate your imagination and get the words flowing.

Attend Writing Workshops and Courses

Formal education such as workshops and courses can offer structured learning and expert guidance. These can provide invaluable insights into the world of creative writing, from understanding plot development to character creation. If you’re wondering is a degree in creative writing worth it, these classes can also give you a taste of what studying creative writing at a higher level might look like .

Joining Writing Groups and Communities

Being part of a writing community can provide motivation, constructive feedback, and a sense of camaraderie. These groups often hold regular meetings where members share their work and give each other feedback. Plus, it’s a great way to connect with others who share your passion for writing.

Seeking Feedback on Your Work

Feedback is a crucial part of improving as a writer. It offers a fresh perspective on your work, highlighting areas of strength and opportunities for improvement. Whether it’s from a writing group, a mentor, or even friends and family, constructive criticism can help refine your writing .

Start Creative Writing Today!

Remember, becoming a proficient writer takes time and patience. So, don’t be discouraged by initial challenges. Keep writing, keep learning, and most importantly, keep enjoying the process. Who knows, your passion for creative writing might even lead to creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree .

Happy writing!

Brooks Manley

Creative Primer is a resource on all things journaling, creativity, and productivity. We’ll help you produce better ideas, get more done, and live a more effective life.

My name is Brooks. I do a ton of journaling, like to think I’m a creative (jury’s out), and spend a lot of time thinking about productivity. I hope these resources and product recommendations serve you well. Reach out if you ever want to chat or let me know about a journal I need to check out!

Here’s my favorite journal for 2024:

Gratitude Journal Prompts Mindfulness Journal Prompts Journal Prompts for Anxiety Reflective Journal Prompts Healing Journal Prompts Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Journal Prompts Mental Health Journal Prompts ASMR Journal Prompts Manifestation Journal Prompts Self-Care Journal Prompts Morning Journal Prompts Evening Journal Prompts Self-Improvement Journal Prompts Creative Writing Journal Prompts Dream Journal Prompts Relationship Journal Prompts "What If" Journal Prompts New Year Journal Prompts Shadow Work Journal Prompts Journal Prompts for Overcoming Fear Journal Prompts for Dealing with Loss Journal Prompts for Discerning and Decision Making Travel Journal Prompts Fun Journal Prompts

Inspiring Ink: Expert Tips on How to Teach Creative Writing

You may also like, 250+ journal prompts for every scenario and circumstance.

A Guide to Morning Journaling + 50 Prompts

Famous diaries: the 10 most famous published diaries, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Productivity

- Favorite Journals

Useful Links

10 Impactful Elements of Creative Writing

Wondering how can you think like J.K. Rowling and craft a creative masterpiece like Harry Potter? Is that even possible for you? Of course, it is quite doable for anyone having a flair for creative writing. But only a passion would not be enough as you need to know how things work in creative writing.

It means you must be aware of the elements of creative writing. Speaking of which, this exciting blog post sheds light on each of these elements in detail for you to form a good base for such writing. So, without further ado, let’s get to read them all.

Table of Contents

The Elements of Creative WritingYou Should Know

Characterization.

Development: Characters with a range of features including emotions, depth, and complexity can capture readers’ attention and propel the story along. Character development is an important element of creative writing!

Arcs and Growth: The development of characters throughout the narrative can create an interesting journey that viewers can relate to.

Plot and Structure

Engaging Plot: A series of occurrences that intrigue readers, containing components such as suspense, opposition, and resolution.

Structure: A structure that is carefully constructed either to adhere to conventional formats or to attempt unconventional storytelling for a stronger effect.

Setting and Atmosphere

Vivid Settings: Writing that creates vivid imagery and allows readers to experience the story’s environment.

Atmospheric Elements: Creating an atmosphere with vivid descriptions of the setting to add to the emotion of the story.

Dialogue and Voice

Authentic Dialogue: Discussions that expose personality attributes, propel the storyline forward, and sound realistic.

Distinctive Voice: The writer’s style and character are expressed through the storytelling.

Theme and Symbolism

Exploration of Themes: Implicit ideas or themes that give the story more substance and significance.

Symbolic Elements: Employment of symbols or figures of speech to express additional layers of meaning and interpretation.

Emotional Resonance

Eliciting Emotions: Evoking feelings in readers, encouraging understanding, bonding, and making a lasting impression.

Authenticity of Emotions: Depiction of real feelings and events that are true to life.

Language and Style

Vivid Language: Employing vivid language, figurative comparisons, and sensory details to form pictures in the mind and to stimulate the senses.

Narrative Style: Developing a distinctive writing style to establish the mood and pacing of the narrative.

Foreshadowing and Pacing

Foreshadowing: Scattered hints and clues placed throughout the story, sparking curiosity and suspense.

Pacing: Varying the pace of the story to keep the reader engaged and emotionally invested.

Suspense and Tension

Suspenseful Elements: Creating excitement about what will happen next in the narrative.

Tension Creation: Factors that create suspense and keep readers interested in the conclusion.

Originality and Innovation

Innovative Storytelling: Trying out different ways of telling a story, such as different narrative forms, genres, and perspectives, which can result in interesting and original stories.

Unexpected Twists: Unanticipated features that defy expectations and draw in viewers.

Understanding Elements with the Help of a Creative Writing Example

Going through creative writing examples is often a good way to adapt the right technique for tackling this task. Here you go with an example.

The Creative Writing Piece

In a peaceful spot in the city, surrounded by towering skyscrapers, was an old house. Its worn-out exterior didn’t give away the secrets inside, especially in the attic, where forgotten gems were collecting dust.

Anna, once full of life as a cellist, now found comfort in the peace and quiet of her home. Her music stopped playing after a heartbreaking incident that took away her brother, Daniel, leaving her with a deep sadness in her heart.

On a stormy afternoon, Anna was trying to avoid thinking about painful memories, so she went into her attic. She found an old music box, with tarnished edges, and she nervously wound it up. A sad melody filled the quiet room.

Anna’s body shuddered as the melancholic tune filled her soul, bringing up memories she had wanted to forget. Daniel’s favorite song was playing, the song they’d shared during their happiest times together. Her eyes blurred with tears as a mix of nostalgia and pain overwhelmed her.

Anna ran her fingers over the detailed carvings on the music box in a trance. The grooves reminded her of all the good times she had with Daniel – his wide grin, and the bond they had. She was filled with emotion as she remembered it all, tears streaming down her face.

As the music tapered off, Anna’s determination increased. She held onto the music box tightly, dead set on figuring out what it meant. She stayed up all night and kept searching, and eventually found hints – a worn-out photo, an outdated show ticket – each one being a small lead to a song that had been forgotten.

Anna had a moment of self-reflection and remembered how much she loved music. She carefully picked up her cello and slowly plucked at the strings, feeling the music stir up her emotions. Gradually, the forgotten melody came back to her and filled the house, blending with the pitter-patter of rain hitting the windows.

Anna used music to find her way to recovery. Every tune she played was a step towards accepting her situation, a reminder of Daniel’s presence. The attic, which had once been a place of grief, now filled with the bittersweet sound of reflection and optimism.

In her music, Anna found that even when she had forgotten certain melodies, they still had the power to bring healing and renewal.

Breaking Down Elements of Creative Writing from the Story

You can get all the ideas about composition and more about creative writing in the comprehensive guide to master creative writing by experts.

Element 1: Idea Generation

Anna, a disheartened cellist who can’t stop thinking about the awful accident that involved her brother, finds comfort in a dusty attic. There she finds an old music box that plays a sorrowful tune, and it brings back memories, causing her to go on a mission to understand its importance.

Element 2: Character Development

Anna: A once-passionate cellist now withdrawn, struggling with unresolved emotions stemming from her brother’s accident.

Brother: A pivotal character in flashbacks, portrayed as a source of inspiration and unresolved grief in Anna’s life.

Element 3: Plot and Structure

The narrative alternates between the present, where Anna discovers the music box, and poignant flashbacks revealing her relationship with her brother and the accident’s aftermath. The structure slowly unravels the emotional layers of Anna’s journey.

Element 4: Setting and Atmosphere

The attic serves as a metaphorical space for introspection, filled with forgotten relics that evoke nostalgia and pain. The contrast between the melancholic tune of the music box and the present silence heightens the emotional atmosphere.

Element 5: Dialogue and Voice

Conversations between Anna and her brother in flashbacks reveal their bond, regrets, and unspoken emotions. Anna’s internal monologue and interactions reflect her inner turmoil and gradual emotional healing.

Element 6: Theme and Symbolism

Themes of loss, healing, and the restorative power of music are explored. The music box symbolizes Anna’s unresolved emotions and her quest to rediscover joy amidst grief.

Element 7: Emotional Resonance

Readers empathize with Anna’s grief and find hope in her journey toward healing. Authentic emotions and gradual healing resonate throughout the narrative, evoking a range of emotions in the audience.

Element 8: Language and Style

Descriptive prose paints vivid images of both physical and emotional landscapes, evoking nostalgia and heartache. The narrative style, with its lyrical prose and introspective reflections, establishes a poignant and contemplative tone.

Element 9: Foreshadowing and Pacing

Clues within the narrative hint at the music box’s significance, building anticipation. Alternating between reflective moments and revelations maintains a pace that allows emotions to linger while propelling the story forward.

Element 10: Originality and Innovation

The blend of music, memories, and emotional introspection creates a narrative that resonates uniquely. Unexpected revelations within Anna’s journey offer hope amidst sorrow, adding depth to the story. The expert writers working with professional paper writing service providers also vouch this element to be very important for the effectiveness of creative writing.

Creative writing is like painting with words! You create characters, plots, and settings and inject emotions to make stories come alive. With interesting characters, emotional appeal, an exciting story, and vivid descriptions, you can draw readers in and make them feel like they’re right there in the adventure. It’s a great way to evoke emotion and fire up imaginations!

This blog post was all about helping you get better with creative writing with knowing the elements of creative writing in good detail.

Get Your Custom Essay Writing Solution From Our Professional Essay Writer's

Timely Deliveries

Premium Quality

Unlimited Revisions

Calculate Your Order Price

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Principles of Creative Writing: An Ultimate Guide

Explore the art of storytelling with our blog on the Principles of Creative Writing. Uncover the key techniques that transform words into captivating narratives. From character development to plot intricacies, we'll guide you through the fundamental principles that breathe life into your writing, helping you craft compelling and imaginative stories.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Report Writing Course

- Effective Communication Skills

- Speed Writing Course

- E-mail Etiquette Training

- Interpersonal Skills Training Course

Table of Contents

1) Understanding Creative Writing Principles

2) Principles of Creative Writing

a) Imagination knows no bounds

b) Crafting compelling characters

c) Plot twists and turns

d) Setting the stage

e) Point of View (POV) and voice

f) Dialogue - The voice of your characters

g) Conflict and tension

h) Show, don't tell

i) Editing and revising with precision

j) The power of theme and symbolism

k) Pacing and rhythm

l) Emotionally resonant writing

m) Atmosphere and mood

3) Conclusion

Understanding Creative Writing Principles

Before we move on to the Principles for Creative Writers, let’s first understand the concept of Creative Writing. Creative Writing is an exploration of human expression, a channel through which Writers communicate their unique perspectives, experiences, and stories.

This form of writing encompasses various genres, such as fiction, poetry, drama, and more. Unlike Technical or Academic Writing, Creative Writing is driven by the desire to evoke emotions, engage readers, and transport them to alternate worlds.

Take your academic writing to the next level – join our Academic Writing Masterclass and unlock the art of effective writing and communication!

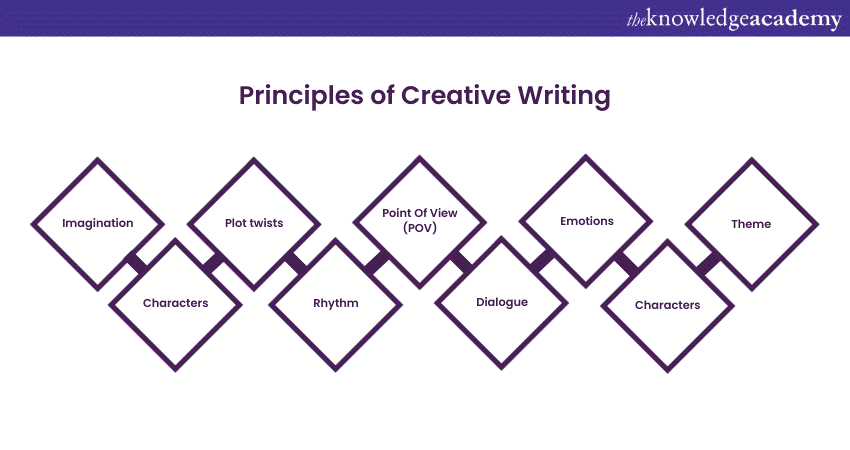

Principles of Creative Writing

Now that you know the meaning of Creative Writing, let’s explore its principles.

Principle 1: Imagination k nows n o b ounds

Your imagination is a treasure trove of ideas waiting to be explored. To cultivate your creative imagination:

a) Allow yourself to think without limitations.

b) Let thoughts collide and see where they lead.

c) Keep a journal to jot down fleeting ideas and use them as springboards for your writing.

Break free from conventional thought patterns—experiment with "what if" scenarios – twist familiar elements into something new. Blend genres, combine unrelated concepts, or put your characters in unexpected situations .

Principle 2: Crafting c ompelling c haracters

Characters are the heart of your story. Develop characters with distinct personalities, motivations, strengths, and flaws. Delve into their backgrounds, understanding their past experiences and how they shape their choices. Consider their beliefs, fears, desires, and relationships with others in the story .

Readers connect with characters they can relate to. Make your characters multifaceted by giving them relatable qualities. Flaws make characters human, so don't hesitate to bestow imperfections upon them. Your readers will find themselves emotionally invested in their journeys as they face challenges and grow.

Principle 3: Plot t wists and t urns

A well-crafted story thrives on plot twists and turns. These unexpected shifts keep readers engaged, encouraging them to explore the unknown alongside your characters. The art of plot twists lies in weaving surprises that challenge characters' assumptions and drive the story in unexpected directions.

Develop logical and unforeseen twists, leaving your audience eager to discover what happens next. Experiment with various narrative structures. Choose the structure that best serves your story's theme and tone.

Principle 4: Setting the s tage

Transport readers into your story's world by vividly describing its physical elements – sights, sounds, smells, and textures. The setting isn't merely a backdrop; it's a living, breathing entity that influences the mood and atmosphere of your narrative. Create an immersive experience that makes readers feel like they're living the story alongside your characters. Make the setting integral to your storytelling, whether a bustling urban landscape or serene countryside.

Principle 5: Point of View (POV) and v oice

Point of View (POV) and voice are essential tools that shape how your story is perceived. POV determines the perspective through which readers experience the narrative – whether through a character's eyes (first person), an external observer (third person limited), or an all-knowing narrator (third person omniscient). Each POV offers a distinct vantage point, influencing what readers know and how they connect with the characters.

On the other hand, voice is the unique style and tone of your writing that reflects the narrator's personality and worldview. Skilful manipulation of POV and voice deepens readers' immersion and connection with the story .

Principle 6: Dialogue - The v oice of y our c haracters

Dialogue is a powerful tool for revealing character relationships and advancing the plot. It's the medium through which characters reveal their personalities, motivations, and conflicts. Make your dialogue sound natural by paying attention to speech patterns, interruptions, and nuances.

Each character should possess a distinctive voice, reflecting their background, emotions, and quirks. Effective dialogue moves the plot forward, adds depth to relationships, and provides insight into characters' inner worlds.

Master your copywriting skills today with our Copywriting Masterclass and create compelling content that drives conversions. Join now!

Principle 7: Conflict and t ension

Conflict drives your story forward. Whether internal (within a character's mind) or external (between characters or forces), conflicts create stakes and keep readers invested. Make conflicts meaningful by connecting them to your characters' goals and desires. Tension, on the other hand, keeps readers engaged by evoking curiosity and emotional investment.

Principle 8: Show, d on't t ell

"Show, don't tell" is a principle that encourages subtlety and reader engagement. Instead of directly stating emotions or information, show them through actions, behaviours, and sensory details. Allow readers to draw their own conclusions, fostering a deeper connection to the narrative.

For example, instead of stating, "She was sad," show her wiping away a tear and gazing out the rain-soaked window. This approach not only immerses readers in the story but also invites them to interpret and empathise with the characters' experiences.

Principle 9: Editing and r evising with p recision

Your first draft is just the beginning. Editing and revising refine your work into its best version. Editing is not just about correcting grammar; it's about refining your prose to convey your message with clarity and impact. Read your work critically, checking for consistency in tone, pacing, and character development. Trim unnecessary elements and tighten sentences to eliminate any ambiguity. Embrace the art of revision to sculpt your rough draft into a polished masterpiece.

Principle 10: The p ower of t heme and s ymbolism

Themes and symbolism add meaning to your writing, inviting readers to explore more profound insights. A theme is your story's central idea or message, while symbolism uses objects, actions, or concepts to represent abstract ideas. By infusing your narrative with meaningful themes and symbolism, you create a tapestry of thought-provoking connections that engage readers on both intellectual and emotional levels.

Principle 11: Pacing and r hythm

The rhythm of your writing affects how readers engage with your story. Experiment with sentence lengths and structures to create a natural flow that guides readers seamlessly through the narrative. Vary pacing to match the intensity of the scenes; fast-paced action should have short, punchy sentences, while contemplative moments can benefit from longer, more introspective prose. Mastering rhythm and flow keep readers entranced from start to finish.

Principle 12: Emotionally r esonant w riting

The goal of Creative Writing is to evoke emotions in your readers. Develop empathy for your characters and encourage readers to feel alongside them. Tap into your own experiences and emotions to connect with readers on a human level. Emotionally charged writing doesn't just entertain; it leaves a mark on readers' hearts, reminding them of shared experiences and universal truths.

Principle 13: Atmosphere and m ood

The atmosphere and mood of a story set the tone for readers' experiences. Through careful selection of words, sentence structures, and descriptive details, you can shape the emotional ambience of your narrative. Whether you're writing an exciting thriller, a magical fantasy, or a serious drama, infuse your writing with an atmosphere that wraps readers in the emotions you want them to feel.

Conclusion

The Principles of Creative Writing provide a roadmap for crafting stories that captivate and inspire. These principles allow you to transform your writing from ordinary to extraordinary easily. As you work on becoming a Creative Writer, remember that practice is key. Each principle mentioned here is like a tool in your Writer's toolbox, waiting to be improved and used effectively.

Elevate your writing skills with our Creative Writing Training . Join today to unleash your creativity!

Frequently Asked Questions

Upcoming business skills resources batches & dates.

Fri 12th Apr 2024

Fri 14th Jun 2024

Fri 30th Aug 2024

Fri 11th Oct 2024

Fri 13th Dec 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure

- Microsoft Excel & Certification Course

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

The Word Count

Because every word counts

- Search Button

8 Elements of Effective Creative Writing (The Art of the Craft)

~ 4-minute read

January is International Creativity Month, and I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to discuss the basic, but crucial, aspects of creative writing. The Art of the Craft article series will go in-depth into the various elements and techniques that go into crafting a work of creative writing. From novel writing to poetry, The Word Count will cover it all!

Already know what you’re hoping to see in The Art of Craft article series? Comment with the topic(s) you want The Word Count to address next!

What is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is the act of using your power of storytelling to create literary productions or compositions in an imaginative and original way. Creative writing is the artistic expression of a lens through which to view the world, a message conveyed through an inventive tale.

What Counts as Creative Writing?

Any work which uses imagery, drama, and narrative to communicate to an audience is considered creative writing. Examples include poems, short stories, novels, scripts, screenplays, and creative nonfiction.

What are the 8 Main Elements of Creative Writing?

Voice refers to the unique style and way a writer expresses oneself on the page. This is similar to how you can recognize someone through the nuances of their personality. A successful creative piece will have a natural, clear, and consistent voice.

The tone of a creative work is the attitude that the writer showcases toward what they are sharing in the story.

Style is the deliberate way in which writers choose words and place them together to craft the story.

4.) Characters

Characters are the people, animals, inanimate objects, or natural forces, etc. whose actions carry the story forward. The crucial act of developing characters takes time and consideration. Creative writers must know their characters in precise detail to effectively develop a connection with their audience.

The sequence of incidents that befall characters in a story is known as the plot. The plot of creative works includes elements, such as suspense-building and conflict that guide the characters throughout the story.

6.) Point of View

Point of View (POV) refers to the perspective that the narrator has on the characters and the events transpiring in the story.

7.) Setting

The setting of a creative work is the place and time period in which the characters dwell and the story takes place.

Theme is the underlying meaning of a creative story, the important statement that the writer aims to share with their audience.

How Do I Get Started Writing my Book?

Step 1: Make Time to Write This is the most important, but oftentimes forgotten, rule of being a writer of any kind. You need to make consistent time in your schedule to write. Not only will this help you develop a stronger sense of commitment, but over time it will train your brain so you can get into “writer mode” even quicker during your writing sessions.

Step 2: Get Ideas for Writing Just as it is crucial for a creative writer to make time to write, so is it important for them to set aside time to observe the world, and comb through the story ideas that pop up along the way.

Step 3: Write Aurally and Visually Even well-written works can become dull and dry without dialogue, interactions, and details that bring them to life! Be thorough when researching genres, setting details, cultures, etc.

Step 4: Draw from your Experiences Besides researching, you can look back at your experiences for ways to bring a character, their dialogue, or the overall story to life.

Step 5: Read One of the best ways to grow as a writer is to explore what others in your genre are doing and understand the specific aspects of what you like or dislike in what you see.

International Creativity Month is a time to embrace your creative muse. If you were looking for a sign to pursue creative writing, here it is. Don’t wait for the perfect time or the right level of confidence to embark on the journey.

As a good friend once told me, “Anything worth doing is worth doing it scared.”

If you are unsure or anxious at the prospect of being a creative writer, The Word Count is here to help guide you because every word counts .

Do you want to learn more about the craft of creative writing? Subscribe to our blog today and get notified when our next post goes live!

#TheArtOfTheCraft, #InternationalCreativityMonth, #CreativeWritingBasics, #CreativeWritingTips, #HowToBecomeAWriter, #CreativeWritingElements, #TheWordCount

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from The Word Count

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

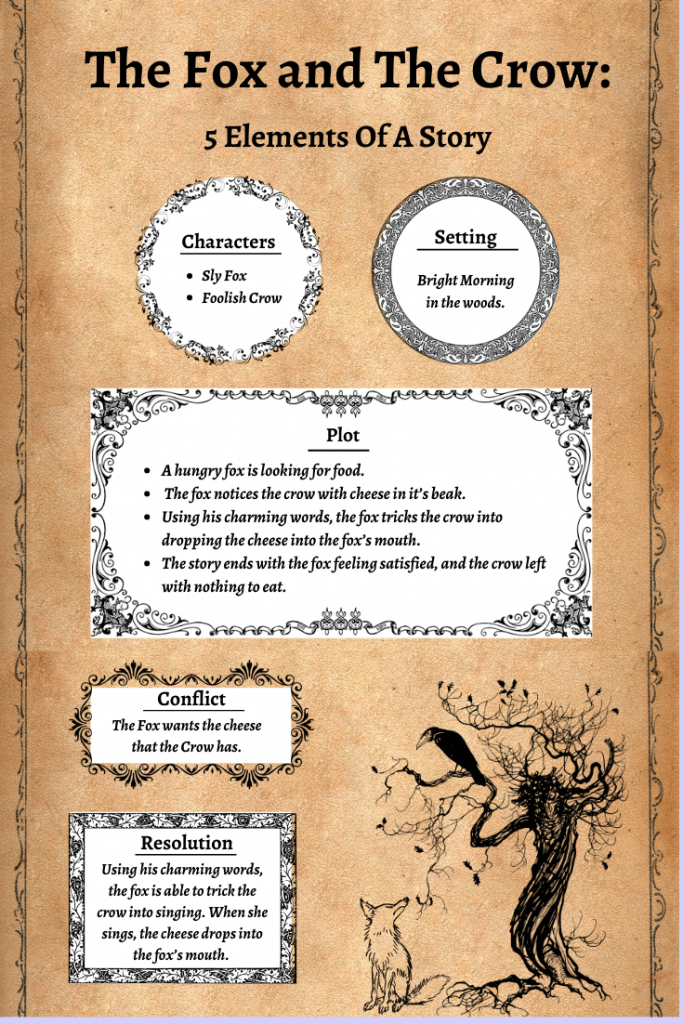

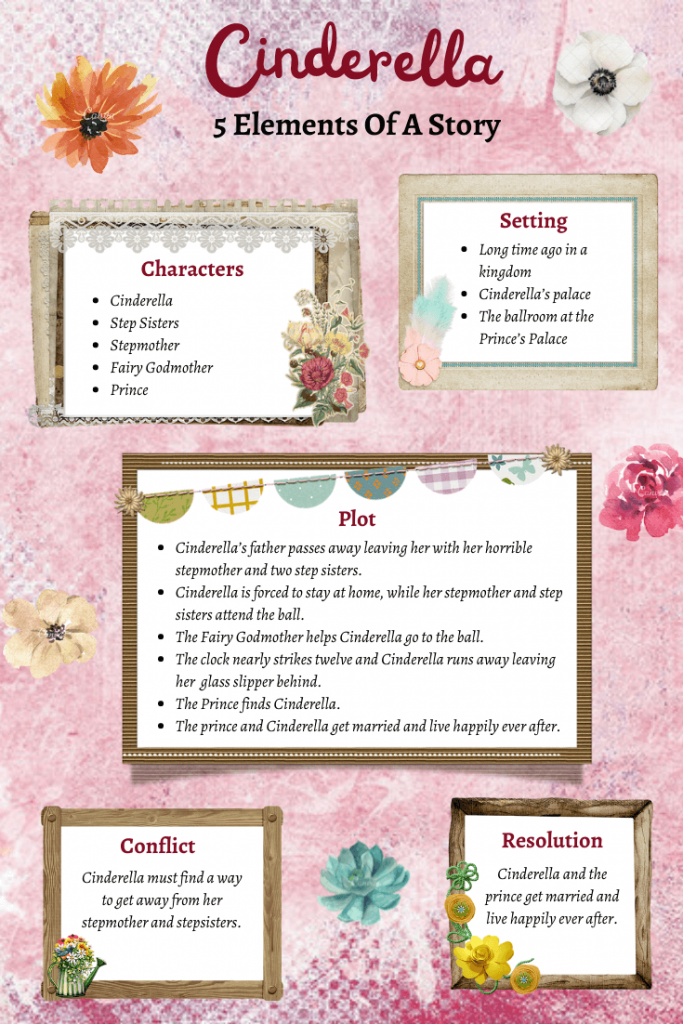

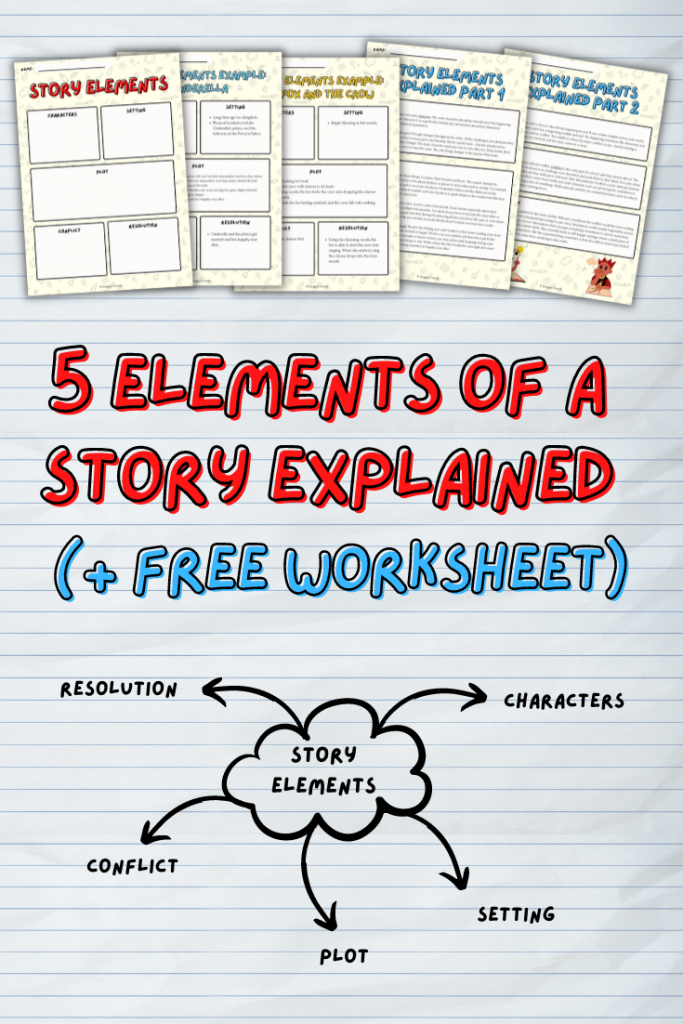

5 Elements Of a Story Explained With Examples (+ Free Worksheet)

What do all good stories have in common? And no it’s not aliens or big explosions! It’s the five elements of a story: Characters, Setting, Plot, Conflict and Resolution. Story elements are needed to create a well-structured story. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing a short story or a long novel, the core elements are always there.

What are Story Elements?

1. characters, 4. conflict, 5. resolution, the fox and the crow, free story elements worksheet (pdf), why are story elements needed, what are the 7 elements of a story, what are the 5 important story elements, what are the 12 elements of a short story, what are the 6 important elements of a story, what are the 9 story elements, what are the 8 elements of a story.

This short video lesson explains the main points relating to the five story elements:

Story elements are the building blocks needed to make a story work. Without these blocks, a story will break down, failing to meet the expectations of readers. Simply put, these elements remind writers what to include in stories, and what needs to be planned. By understanding each element, you increase the chances of writing a better story or novel.

Over the years, writers have adapted these elements to suit their writing process. In fact, there can be as few as 4 elements in literature all the way up to 12 elements. The most universally used story elements contain just five building blocks:

These five elements are a great place to start when you need help planning your story. You may also notice that these story elements are what most book outlining techniques are based on.

5 Elements Of A Story

Below we have explained each of the five elements of a story in detail, along with examples.

Characters are the most familiar element in stories. Every story has at least one main character. Stories can also have multiple secondary characters, such as supporting characters and villain/s. The main character should be introduced at the beginning. While introducing this character it is a good idea to include key information about this character’s personality, past and physical appearance. You should also provide a hint to what this character’s major conflict is in the story (more on conflict later).

The main character also goes through changes throughout the story. All the challenges and obstacles they face in the story allow them to learn, grow and develop. Depending on your plot, they might become a better person, or even a worse one – if this is a villain’s origin story. But be careful here – Growth should not be mistaken for a personality change! The main character must stay true to who they are. Deep inside their personality should stay more or less the same. The only thing that changes is the lessons they learn, and how these impact them.

Check out this post on 20 tips for character development for more guidance.

Settings in stories refer to three things: Location, Time Period and Mood. The easiest element to understand is location . Location is the physical place/s the story takes part in mostly. For example, the tale of Cinderella takes part in two main locations: Cinderella’s Palace and the Ballroom at the Prince’s Palace. It is a good idea to explain each new location in great detail, so the readers feel like they are also right there with the characters. The physical location is also something that can be included at the beginning of the story to set the story’s tone.

Next comes the time period . Every story is set in some time period. Some stories especially about time travel may be set across multiple time periods. You don’t always have to include the exact date or year in your story. But it is a good idea that during the planning phase, you know the year or even dates the story is set in. This can help you include accurate details about location and even key events. For example, you don’t want to be talking about characters using mobile phones in the 18th century – It just wouldn’t make sense (Unless of course, it’s a time travel story)!

The final part of the setting is the mood . The mood is the feeling you want readers to feel when reading your story. Do you want them to be scared, excited or happy? It’s the way you explain and describe a particular location, object or person. For example in horror stories, you may notice dark language being used throughout, such as gore, dismal, damp or vile. While a fairy tale such as Cinderella uses light and warm language like magical, glittering, beautiful or happily ever after. The choice of words sets the mood and adds an extra layer of excitement to a story.

The plot explains what a story is about from beginning to end. It can contain multiple scenes and events. In its simplest form, a plot has a beginning, middle and end. The beginning introduces the characters and sometimes shows a minor conflict. The middle is where the major conflict occurs. And the ending is where all conflicts are resolved, and the story comes to a close. The story mountain template is a great way to plan out a story’s plot.

A story is not a story without conflict. Conflict is also a key part of a story’s plot (see section above). The purpose of conflict in stories is to challenge your characters and push them to their limits. It is only when they face this conflict, do they really grow and reach their full potential. Conflicts can be internal, external or both. Internal conflicts come from inside your main character, such as not having the confidence in themself or having a fear of something. While external conflicts are created elsewhere, such as natural disasters or evil villains creating havoc.

The resolution is a solution to the main conflict. Without a resolution, the conflict would be neverending, and this could lead to a disappointing ending to your story. Resolutions could include huge battle scenes or even the discovery of new information which changes everything. Sometimes in stories resolutions don’t always solve the conflict 100%. This normally leads to cliffhanger endings, where a small piece of conflict still exists somewhere. But the important thing to remember is that all conflicts need some kind of resolution in stories to make them satisfying to the reader.

Story Elements Examples

We explained each story element above, and now it’s time to put our teachings into practice. Here are some common story element examples we created.

The fox and the crow is one of Aesop’s most famous fables . It tells the story of a sly fox who tricks a foolish crow into giving her breakfast away. You can read the full fable on the read.gov website .

Here are the elements of a story applied to the fable of the fox and the crow:

- Characters: A sly fox and a foolish crow.

- Setting: Bright Morning in the woods.

- Plot: A hungry fox is looking for food. The fox notices the crow with cheese in its beak. Using his charming words, the fox tricks the crow into dropping the cheese into the fox’s mouth. The story ends with the fox feeling satisfied, and the crow left with nothing to eat.

- Conflict: The Fox wants the cheese that the Crow has.

- Resolution: Using his charming words, the fox is able to trick the crow into singing. When she starts to sing, the cheese drops into the fox’s mouth.

Cinderella is one of the most famous fairy tales of all time. It tells the tale of a poor servant girl who is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters. One night with the help of her fairy godmother, she attends the ball. It is at the ball that the prince falls in love with Cinderella. Eventually leading to a happy ending.

Here are the elements of a story applied to the short story of Cinderella:

- Characters: Cinderella, the stepsisters, the stepmother, the fairy godmother, and the prince.

- Setting: Long time ago in a kingdom. Physical locations include Cinderella’s Palace and the ballroom at the Prince’s Palace.

- Plot: Cinderella’s father passes away leaving her with her horrible stepmother and two stepsisters. They abuse her and make her clean the house all day. One day, an invite comes from the Prince’s palace inviting everyone to the ball. Cinderella is forced to stay at home, while her stepmother and sisters attend. Suddenly Cinderella’s fairy godmother appears and helps her get to the ball. But she must return home by midnight. At the ball, Cinderella and the Prince fall in love. The clock nearly strikes twelve and Cinderella runs away leaving a glass slipper behind. The prince then searches the kingdom to find Cinderella. Eventually, he finds her. The two get married and live happily ever after.

- Conflict: Cinderella must find a way to get away from her stepmother and stepsisters.

- Resolution: Cinderella and the prince get married.

Put everything you learned into practice with our free story elements worksheet PDF. This PDF includes a blank story elements anchor chart or graphic organiser, two completed examples and an explanation of each of the story elements. This worksheet pack is great for planning your own story:

Common Questions About Story Elements

Writing a story is a huge task. Simply just putting pen to paper isn’t really going to cut it, especially if you want to write professionally. Planning is needed. That’s where the story elements come in. Breaking a story down into different components, helps you plan out each area carefully. It also reminds you of the importance of each element and the impact they can have on the final story.

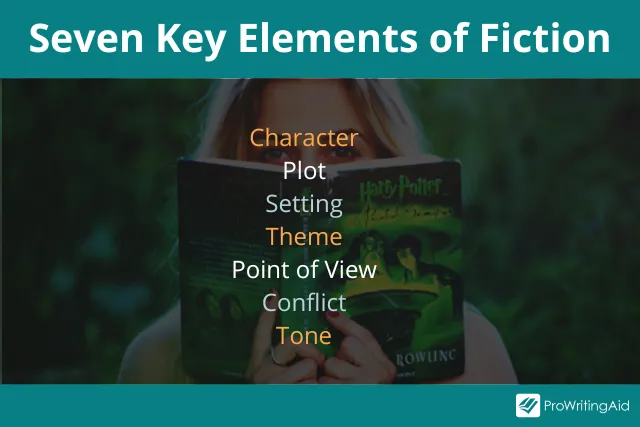

Some writers have expanded the traditional 5 elements to 7 elements of a story. These 7 elements include:

- Theme: What is the moral or main lesson to learn in your story?

- Characters: Who are your main and supporting characters?

- Setting: Where is your story set? Think about location and time period.

- Plot: What happens in your story?

- Conflict: What is the main conflict? Is this conflict internal or external?

- Point of View: Is this story written in first, second or third person view?

- Style: What kind of language or tone of voice will you use?

The 5 elements of a story include:

- Setting: Where is your story set? Think about location, time period and mood.

- Plot: What are the key events that happen in your story ?

- Resolution: How is the main conflict solved?

The longest version of the story elements includes 12 elements:

- Protagonist: Who is the main character or hero of the story?

- Antagonist : Who is the villain of the story?

- Setting : Where is your story set? Think about location and time period.

- Conflict : What is the main conflict? Is this conflict internal or external?

- Sacrifice : What will the main character lose if they fail?

- Rising Action : What action/s lead up to the main conflict?

- Falling Action: What happens after the conflict had ended?

- Message: What is the key message of your story?

- Language : What kind of words would you use? Think about the tone of voice and mood of the story.

- Theme: What is the overall moral or main lesson to learn in your story?

- Reality: How does your story relate to the real world?

Some versions of the story elements, completely remove the conflict element. In the 6 elements structure, conflict is included in the plot element:

- Plot: What happens in your story? Think about the main conflict.

We could consider the order of events, in this 9 story elements structure:

- Tension: What is the source of conflict?

- Climax: The moment when the main conflict happens.

- Plot: What happens in your story?

- Purpose: Why do certain events happen in your story?

- Chronology: What is the order of main events in your story?

The story elements can also be adapted to contain 8 elements:

- Style: What kind of language or words will you use?

- Tone: What is the overall mood of the story? Is it dark, funny or heartfelt?

Got any more questions about the key elements of a story? Share them in the comments below!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

Whether you’ve been struck with a moment of inspiration or you’ve carried a story inside you for years, you’re here because you want to start writing fiction. From developing flesh-and-bone characters to worlds as real as our own, good fiction is hard to write, and getting the first words onto the blank page can be daunting.

Daunting, but not impossible. Although writing good fiction takes time, with a few fiction writing tips and your first sentences written, you’ll find that it’s much easier to get your words on the page.

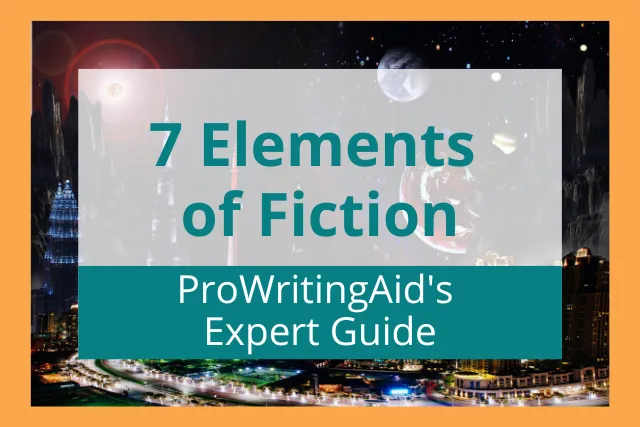

Let’s break down fiction to its essential elements. We’ll investigate the individual components of fiction writing—and how, when they sit down to write, writers turn words into worlds. Then, we’ll turn to instructor Jack Smith and his thoughts on combining these elements into great works of fiction. But first, what are the elements of fiction writing?

Introduction to Fiction Writing: The Six Elements of Fiction

Before we delve into any writing tips, let’s review the essentials of creative writing in fiction. Whether you’re writing flash fiction , short stories, or epic trilogies, most fiction stories require these six components:

- Plot: the “what happens” of your story.

- Characters: whose lives are we watching?

- Setting: the world that the story is set in.

- Point of View: from whose eyes do we see the story unfold?

- Theme: the “deeper meaning” of the story, or what the story represents.

- Style: how you use words to tell the story.

It’s important to recognize that all of these elements are intertwined. You can’t build the setting without writing it through a certain point of view; you can’t develop important themes with arbitrary characters, etc. We’ll get into the relationship between these elements later, but for now, let’s explore how to use each element to write fiction.

1. Fiction Writing Tip: Developing Fictional Plots

Plot is the series of causes and effects that produce the story as a whole. Because A, then B, then C—ultimately leading to the story’s climax , the result of all the story’s events and character’s decisions.

If you don’t know where to start your story, but you have a few story ideas, then start with the conflict . Some novels take their time to introduce characters or explain the world of the piece, but if the conflict that drives the story doesn’t show up within the first 15 pages, then the story loses direction quickly.

That’s not to say you have to be explicit about the conflict. In Harry Potter, Voldemort isn’t introduced as the main antagonist until later in the first book; the series’ conflict begins with the Dursley family hiding Harry from his magical talents. Let the conflict unfold naturally in the story, but start with the story’s impetus, then go from there.

2. Fiction Writing Tip: Creating Characters

Think far back to 9th grade English, and you might remember the basic types of story conflicts: man vs. nature, man vs. man, and man vs. self. The conflicts that occur within stories happen to its characters—there can be no story without its people. Sometimes, your story needs to start there: in the middle of a conversation, a disrupted routine, or simply with what makes your characters special.

There are many ways to craft characters with depth and complexity. These include writing backstory, giving characters goals and fatal flaws, and making your characters contend with complicated themes and ideas. This guide on character development will help you sort out the traits your characters need, and how to interweave those traits into the story.

3. Fiction Writing Tip: Give Life to Living Worlds

Whether your story is set on Earth or a land far, far away, your setting lives in the same way your characters do. In the same way that we read to get inside the heads of other people, we also read to escape to a world outside of our own. Consider starting the story with what makes your world live: a pulsing city, the whispered susurrus of orchards, hills that roil with unsolved mysteries, etc. Tell us where the conflict is happening, and the story will follow.

4. Fiction Writing Tip: Play With Narrative Point of View

Point of view refers to the “cameraman” of the story—the vantage point we are viewing the story through. Maybe you’re stuck starting your story because you’re trying to write it in the wrong person. There are four POVs that authors work with:

- First person—the story is told from the “I” perspective, and that “I” is the protagonist.

- First person peripheral—the story is told from the “I” perspective, but the “I” is not the protagonist, but someone adjacent to the protagonist. (Think: Nick Carraway, narrator of The Great Gatsby. )

- Second person—the story is told from the “you” perspective. This point of view is rare, but when done effectively, it can create a sense of eeriness or a personalized piece.

- Third person limited—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator usually writes from the perspective of one or two characters.

- Third person omniscient—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator knows what is happening in each character’s heads and in the world at large.

If you can’t find the right words to begin your piece, consider switching up the pronouns you use and the perspective you write from. You might find that the story flows onto the page from a different point of view.

5. Fiction Writing Tip: Use the Story to Investigate Themes

Generally, the themes of the story aren’t explored until after the aforementioned elements are established, and writers don’t always know the themes of their own work until after the work is written. Still, it might help to consider the broader implications of the story you want to write. How does the conflict or story extend into a bigger picture?

Let’s revisit Harry Potter’s opening scenes. When we revisit the Dursleys preventing Harry from knowing about his true nature, several themes are established: the meaning of family, the importance of identity, and the idea of fate can all be explored here. Themes often develop organically, but it doesn’t hurt to consider the message of your story from the start.

6. Fiction Writing Tip: Experiment With Words

Style is the last of the six fiction elements, but certainly as important as the others. The words you use to tell your story, the way you structure your sentences, how you alternate between characters, and the sounds of the words you use all contribute to the mood of the work itself.

If you’re struggling to get past the first sentence, try rewriting it. Write it in 10 words or write it in 200 words; write a single word sentence; experiment with metaphors, alliteration, or onomatopoeia . Then, once you’ve found the right words, build from there, and let your first sentence guide the style and mood of the narrative.

Now, let’s take a deeper look at the craft of fiction writing. The above elements are great starting points, but to learn how to start writing fiction, we need to examine the craft of combining these elements.

Primer on the Elements of Fiction Writing

First, before we get into the craft of fiction writing, it’s important to understand the elements of fiction. You don’t need to understand everything about the craft of fiction before you start keying in ideas or planning your novel. But this primer will be something you can consult if you need clarification on any term (e.g., point of view) as you learn how to start writing fiction.

The Elements of Fiction Writing

A standard novel runs between 80,000 to 100,000 words. A short novel, going by the National Novel Writing Month , is at least 50,000. To begin with, don’t think about length—think about development. Length will come. It is true that some works lend themselves more to novellas, but if that’s the case, you don’t want to pad them to make a longer work. If you write a plot summary—that’s one option on getting started writing fiction—you will be able to get a fairly good idea about your project as to whether it lends itself to a full-blown novel.

For now, let’s think about the various elements of fiction—the building blocks.

Writing Fiction: Your Protagonist

Readers want an interesting protagonist , or main character. One that seems real, that deals with the various things in life we all deal with. If the writer makes life too simple, and doesn’t reflect the kinds of problems we all face, most readers are going to lose interest.

Don’t cheat it. Make the work honest. Do as much as you can to develop a character who is fully developed, fully real—many-sided. Complex. In Aspects of the Novel , E.M Forster called this character a “round” characte r. This character is capable of surprising us. Don’t be afraid to make your protagonist, or any of your characters, a bit contradictory. Most of us are somewhat contradictory at one time or another. The deeper you see into your protagonist, the more complex, the more believable they will be.

If a character has no depth, is merely “flat,” as Forster terms it, then we can sum this character up in a sentence: “George hates his ex-wife.” This is much too limited. Find out why. What is it that causes George to hate his ex-wife? Is it because of something she did or didn’t do? Is it because of a basic personality clash? Is it because George can’t stand a certain type of person, and he didn’t realize, until too late, that his ex-wife was really that kind of person? Imagine some moments of illumination, and you will have a much richer character than one who just hates his ex-wife.

And so… to sum up: think about fleshing out your protagonist as much as you can. Consider personality, character (or moral makeup), inclinations, proclivities, likes, dislikes, etc. What makes this character happy? What makes this character sad or frustrated? What motivates your character? Readers don’t want to know only what —they want to know why .

Usually, readers want a sympathetic character, one they can root for. Or if not that, one that is interesting in different ways. You might not find the protagonist of The Girl on the Train totally sympathetic, but she’s interesting! She’s compelling.

Here’s an article I wrote on what makes a good protagonist.

Also on clichéd characters.

Now, we’re ready for a key question: what is your protagonist’s main goal in this story? And secondly, who or what will stand in the way of your character achieving this goal?

There are two kinds of conflicts: internal and external. In some cases, characters may not be opposing an external antagonist, but be self-conflicted. Once you decide on your character’s goal, you can more easily determine the nature of the obstacles that your protagonist must overcome. There must be conflict, of course, and stories must involve movement. Things go from Phase A to Phase B to Phase C, and so on. Overall, the protagonist begins here and ends there. She isn’t the same at the end of the story as she was in the beginning. There is a character arc.

I spoke of character arc. Now let’s move on to plot, the mechanism governing the overall logic of the story. What causes the protagonist to change? What key events lead up to the final resolution?

But before we go there, let’s stop a moment and think about point of view, the lens through which the story is told.

Writing Fiction: Point of View as Lens

Is this the right protagonist for this story? Is this character the one who has the most at stake? Does this character have real potential for change? Remember, you must have change or movement—in terms of character growth—in your story. Your character should not be quite the same at the end as in the beginning. Otherwise, it’s more of a sketch.

Such a story used to be called “slice of life.” For example, what if a man thinks his job can’t get any worse—and it doesn’t? He started with a great dislike for the job, for the people he works with, just for the pay. His hate factor is 9 on a scale of 10. He doesn’t learn anything about himself either. He just realizes he’s got to get out of there. The reader knew that from page 1.

Choose a character who has a chance of undergoing change of some kind. The more complex the change, the better. Characters that change are dynamic characters , according to E. M. Forster. Characters that remain the same are static characters. Be sure your protagonist is dynamic.

Okay, an exception: Let’s say your character resists change—that can involve some sort of movement—the resisting of change.

Here’s another thing to look at on protagonists—a blog I wrote: https://elizabethspanncraig.com/writing-tips-2/creating-strong-characters-typical-challenges/

Writing Fiction: Point of View and Person

Usually when we think of point of view, we have in mind the choice of person: first, second, and third. First person provides intimacy. As readers we’re allowed into the I-narrator’s mind and heart. A story told from the first person can sometimes be highly confessional, frank, bold. Think of some of the great first-person narrators like Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield. With first person we can also create narrators that are not completely reliable, leading to dramatic irony : we as readers believe one thing while the narrator believes another. This creates some interesting tension, but be careful to make your protagonist likable, sympathetic. Or at least empathetic, someone we can relate to.

What if a novel is told in first person from the point of view of a mob hit man? As author of such a tale, you probably wouldn’t want your reader to root for this character, but you could at least make the character human and believable. With first person, your reader would be constantly in the mind of this character, so you’d need to find a way to deal with this sympathy question. First person is a good choice for many works of fiction, as long as one doesn’t confuse the I-narrator with themselves. It may be a temptation, especially in the case of fiction based on one’s own life—not that it wouldn’t be in third person narrations. But perhaps even more with a first person story: that character is me . But it’s not—it’s a fictional character.

Check out my article on writing autobiographical fiction, which appeared in The Writer magazine. https://www.writermag.com/2018/07/31/filtering-fact-through-fiction/

Third person provides more distance. With third person, you have a choice between three forms: omniscient, limited omniscient, and objective or dramatic. If you get outside of your protagonist’s mind and enter other characters’ minds, you are being omniscient or godlike. If you limit your access to your protagonist’s mind only, this is limited omniscience. Let’s consider these two forms of third-person narrators before moving on to the objective or dramatic POV.

The omniscient form is rather risky, but it is certainly used, and it can certainly serve a worthwhile function. With this form, the author knows everything that has occurred, is occurring, or will occur in a given place, or in given places, for all the characters in the story. The author can provide historical background, look into the future, and even speculate on characters and make judgments. This point of view, writers tend to feel today, is more the method of nineteenth-century fiction, and not for today. It seems like too heavy an authorial footprint. Not handled well—and it is difficult to handle well—the characters seem to be pawns of an all-knowing author.

Today’s omniscience tends to take the form of multiple points of view, sometimes alternating, sometimes in sections. An author is behind it all, but the author is effaced, not making an appearance. BUT there are notable examples of well-handled authorial omniscience–read Nobel-prize winning Jose Saramago’s Blindness as a good example.

For more help, here’s an article I wrote on the omniscient point of view for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/omniscient-pov/

The limited omniscient form is typical of much of today’s fiction. You stick to your protagonist’s mind. You see others from the outside. Even so, you do have to be careful that you don’t get out of this point of view from time to time, and bring in things the character can’t see or observe—unless you want to stand outside this character, and therein lies the omniscience, however limited it is.

But anyway, note the difference between: “George’s smiles were very welcoming” and “George felt like his smiles were very welcoming”—see the difference? In the case of the first, we’re seeing George from the outside; in the case of the second, from the inside. It’s safer to stay within your protagonist’s perspective as much as possible and not describe them from the outside. Doing so comes off like a point-of-view shift. Yet it’s true that in some stories, the narrator will describe what the character is wearing, tell us what his hopes and dreams are, mention things he doesn’t know right now but will later—and perhaps, in rather quirky stories, the narrator will even say something like “Our hero…” This can work, and has, if you create an interesting narrative voice. But it’s certainly a risk.

The dramatic or objective point of view is one you’ll probably use from time to time, but not throughout your whole novel. Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants” is handled with this point of view. Mostly, with maybe one exception, all we know is what the characters say and do, as in a play. Using this point of view from time to time in a longer work can certainly create interest. You can intensify a scene sometimes with this point of view. An interesting back and forth can be accomplished, especially if the dialogue is clipped.

I’ve saved the second-person point of view for the last. I would advise you not to use this point of view for an entire work. In his short novel Bright Lights, Big City , Jay McInerney famously uses this point of view, and with some force, but it’s hard to pull off. In lesser hands, it can get old. You also cause the reader to become the character. Does the reader want to become this character? One problem with this point of view is it may seem overly arty, an attempt at sophistication. I think it’s best to choose either first or third.

Here’s an article I wrote on use of second person for The Writer magazine. Check it out if you’re interested. https://www.writermag.com/2016/11/02/second-person-pov/

Writing Fiction: Protagonist and Plot and Structure