Judith Butler: their philosophy of gender explained

Lecturer in Gender Studies, University of Adelaide

Disclosure statement

Anna Szorenyi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Adelaide provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the American philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler, both for intellectuals and for queer communities. There are scholarly books, university courses, fan clubs, social media pages and comics dedicated to Butler’s thinking.

They (Butler’s preferred pronoun) did not single-handedly invent queer theory and today’s proliferation of gender identities, but their work is often credited with helping to make these developments possible.

In turn, political movements have often inspired Butler’s work. Butler served on the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission , spoke at the Occupy Wall Street protests, has defended Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaigns, and famously declined a Civil Courage Award in Berlin because of racist comments made by the organisers.

This has at times led to controversy. Some right-wing movements and religious figures who are attached to conservative gender roles have seen Butler as a threat to society. This is ironic, given Butler’s work has always maintained a commitment to justice, equality and non-violence.

Gender performativity

The most influential concept in Butler’s work is “gender performativity”. This theory has been refined across Butler’s work over several decades, but it is addressed most directly in Gender Trouble (1990), Bodies That Matter (1993) and Undoing Gender (2004).

In these works, Butler sets out to challenge “essentialist” understandings of gender: in other words, assumptions that masculinity and femininity are naturally or biologically given, that masculinity should be performed by male bodies and femininity by female bodies, and that these bodies naturally desire their “opposite”.

Living in gay and lesbian communities, Butler had seen how even in feminist circles, these assumptions often resulted in unliveable lives for those who did not follow gendered expectations.

Butler therefore set out to challenge the way descriptions of current ways of performing masculinity and femininity are usually also taken to be values about the right way to do gender. Butler uses the concept of gender “norms” to describe this confusion of what “is” with what “should be”, a confusion that prevents us seeing other possible ways of life as legitimate, or even imagining such possibilities at all.

Instead, Butler proposes that gender is not biological, but “performative”. The term “performativity” does not simply mean performance. We can think of it in terms of the linguist J.L. Austin’s concept of the “performative utterance”, which refers to a statement that brings about that which it states. The classic example is “I now pronounce you man and wife”. Spoken by a person socially approved to do so, these words create a married couple.

Butler argues that gender works in this way: when we name a child as “girl” or “boy”, we participate in creating them as that very thing. By speaking of people (or ourselves) as “man” or “woman”, we are in the process creating and defining those categories.

Some gender theory distinguishes between biological “sex” and social “gender” , but Butler finds this counterproductive. For Butler, it makes no sense to talk about biological “sex” existing outside of its social meanings. If there is such a thing, we can’t encounter it, because we are born into a world that already has a particular understanding of gender, and that world then retrospectively tells us the meaning of our anatomy. We can’t know ourselves outside of those social meanings. In fact, much of Butler’s work reminds us we cannot fully know ourselves at all.

At this point, Butler is often accused of thinking gender is entirely caused by language and has nothing to do with bodies, or that we can simply decide what gender to be when we wake up in the morning.

But this is not what they mean. Butler argues that we reproduce gender not only through repeated ways of speaking, but also of doing. We dress in certain ways, do certain exercises at the gym, use particular body language, visit particular kinds of medical specialists, and so on. Through such repetitions, gender is reinforced, layer by layer, until it seems inescapable.

However, this work of creating and redefining gender is never finished – for gender norms to hold, they must be constantly repeated. This means in the longer term, gender norms are intrinsically open to change. We can never get them exactly “right”, and if we stop doing them, or do them differently, we participate in changing their meaning. This opens up possibilities for gender to change.

These are not easy ways to think, because they challenge some of our most familiar assumptions about what a person is, what gender is, and how language works. This is one reason why Butler’s writing has been notorious for being “difficult”. But the popularity of their work shows there are many people who feel their lives are not adequately described by “common sense” ways of thinking.

Read more: Explainer: what does it mean to be 'cisgender'?

Grievable life, vulnerability and non-violence

Over the past 20 years, Butler’s writing has expanded beyond gender into other areas of political exclusion and oppression. An underlying theme across much of this more recent work is a concern about the ways some people are discounted as “human”.

Butler summarises this through the concept of “grievable life”, which draws attention to the ways in which some lives are not publicly mourned, because they were never publicly acknowledged as being properly alive in the first place. For example, Butler points out that AIDS victims rarely receive obituaries in mainstream US newspapers, nor do prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, Palestinians killed by the Israeli military, Black people killed by US police, or refugees and stateless people who die crossing borders.

These populations can be abandoned to unliveable, precarious lives and unnoticed deaths without any serious public accountability. In our contemporary globalised, neoliberal world, more and more people are living in such situations, without adequate social support, health care, sustainable environments or access to the public sphere. Butler calls this situation “precarity”.

Often this exclusion is justified through “frames of war”, which position certain groups of people as threats to “security”. To defend this security, it is tempting to violently impose precarity on others, as the US administration did after 9/11 in the “war on terror”.

To counter such frames of war, Butler proposes an ethics of non-violence, based on the understanding that we become ourselves only in relation to others. This means that no life is fully secure, self-contained or independent. We cannot choose who shares the planet with us, and they can always hurt us. Ultimately, if we are to survive together, we must learn to acknowledge and live with mutual vulnerability, as challenging as that may be.

This may sound idealistic, but it is not an ethics that assumes people are “nice”. It starts from the proposition that they are not. Performing non-violence will always be ambivalent and difficult, especially in a violent world. But it is in our own interests to realise that our own capacity to live a “liveable life” depends on life-sustaining conditions that also allow others (human and non-human) to live.

Butler finds performative enactments of this approach in some collective protests, such as the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York and the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey, in which people from different backgrounds gathered to call for a more just and equitable world.

Butler reminds us that vulnerability is not all bad; it is what makes life possible. All bodies must be in some way open to the world and to others. They must be able to take in and give out: to eat, breathe, speak, be intimate. A body unable to do this could not be alive. Ultimately, Butler reminds us, often poetically, that to be fully ourselves, we need each other.

- Queer theory

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Partner, Senior Talent Acquisition

Deputy Editor - Technology

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

- Memberships

- Employer opportunities

Explore our Memberships

Become a part of the FW family for as little as $1 per week.

Employer Opportunities

Turn words into action. Work with us to build a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

FW was founded in 2018 with a promise to help women connect, learn and lead.

Leadership Summit

Hear from notable women around the country on topics including leadership, business, finance, wellness and culture.

Two days of inspiring keynote speeches, panel discussions and interactive sessions.

- Publications

- Newsletters

How to ask for what you want

Catherine Brenner, Louise Adler and Sam Mostyn offered their advic...

Reclaiming your power at forty

Em Rusciano outlines four lessons we can all take from her own sei...

Making The Case: How To Successfully Argue For A Pay Rise

In our latest series, Making The Case, Future Women's arguer-in-ch...

There's No Place Like Home

Putting survivors of family violence at the centre of the story.

Gender equality in print

Books written and edited by the FW team.

- FW Masterclass Series

Platinum+ Emerging Leader

Change makers, fw masterclass.

Your next step as an effective leader.

A program for mid-career women and exceptional graduates to fast track their career journey.

A program designed for men who want to become better managers and leaders.

Connect with expert mentors and an advisory board of like-minded women to solve a professional challenge.

How critical thinking can help advance gender equality and why you should ‘test everything you hear’

"We can definitely get way ahead in gender equality with a lot of these discussions.”

By Kate Kachor

Critical thinking can help break down gender bias in the workplace, but only if leaders encourage others to feel comfortable to “question everything”.

This was the broad takeaway from an expert panel at this week’s Future Women Leadership Summit 2022.

“Diversity of thought is really good in producing different outcomes. So, the value of critical thinking is – it’s basically what’s often referred to as cognitive discernment,” Vitae co-founder and CEO Shelley Laslett said.

“It allows us to make sense of what’s going on both in our own minds, our internal processes, and also our external processes.”

Laslett said critical thinking is particularly valuable in the workplace because it increases EQ and IQ – at both the individual and group level.

“We know that the most profitable and most successful firms have high levels of diverse thinking because they have high levels of diverse views,” she said.

Amanda Rose, the Founding Director of Western Sydney Women, said the way she described critical thinking, in its simplest form, is “test everything you hear”.

“I think if you want to break any bias in any way, we need to put in the effort and we need to encourage others to feel comfortable to be able to disagree with you, to be able to ask questions,” she said.

“With gender bias, the problem is, and those women who work with men will know this, you sit in a room you have a conversation and things are said and they are taken as word. As gospel – ‘yep, that’s just the way it is’.”

She said women have been conditioned not to ask questions, and not to disagree.

“I had someone say ‘sorry, I don’t agree with that’. I said why are you sorry for having a different opinion? We should be embracing that, and leaders should be embracing that,” she said.

“So, I think we need to encourage our teams, whether male or female, to ask someone in the room ‘what do they think?’”

Aparna Sundararajan, a senior research strategist with ADAPT senior research, agreed.

Amanda Rose (left) Aparna Sundarajan (centre left) Kiera Peacock (centre right) and Tarang Chawla (right) discussed critical thinking at Future Women’s Leadership Summit 2022

“I think we all are conditioned to think in a pre-set way, influenced by our culture and tradition and if we have the curiosity to find objective reasoning then we might be able to get to the back alleys and nooks and crannies and find information that has probably been hidden,” she said.

“So, in that way we can definitely get way ahead in gender equality with a lot of these discussions.”

Kiera Peacock, a partner at Marque Lawyers, said in her experience with critical thinking involved a level of vulnerability.

“In professional services it’s quite an interesting one dealing with critical thinking because clients come to you and they want the answer – and they want one answer,” she said.

“So, there’s a certain vulnerability in applying critical thinking in that context so I think the important thing in the professional services field is to create that sense, by critically thinking I’m trying to get you the best outcome. And while that may not lead you to a yes or no answer, this is the journey you’re coming with me on, and this is where I’m trying to get you to.”

Laslett said it was important to also understand is that critical thinking is inherent to being human.

“When it comes to being too critical – if we’re looking at only the negative or only the risk or only the downside, and we’re not open to possibility and open to ideas, open to difference, open to any form of innovation – that’s when we’re going to get caught in that box of being too critical,” she said.

The expert panel on critical thinking and solving complex problems at Future Women’s Leadership Summit 2022

Rose offered that when people are being overly critical it usually comes from a place of fear.

“They fear change, they fear being wrong, they fear what they’ve been working on or what they believed in is wrong,” she said.

“So, when someone is very critical to you, find out why. What’s the fear behind that? It happens a lot with generational workplaces where someone is younger is the boss of someone who’s older and there’s that resistance and that fear.”

She also pressed while critical thinking “is brilliant”, it’s important to remain true to who you are.

“Don’t budge from your morals. Your core belief system should not change,” she said.

PHOTOGRAPHER: MARK BROOME

events fwsummit gold membership

More from Future Women’s 2022 International Leadership Summit

Melissa Leong: Barriers can be broken with the breaking of bread

Taking on a leadership role in your own life

The horror reality one in four women face

The benefits and risks of ‘being yourself’ at work

Why Dr Julia Baird is searching for grace (and you should too)

Clare Bowditch and her curious career

Why we can’t lean in or girlboss our way out of inequity

Tackling the ‘big problems’ women face in the world starts with the truth

Your inbox just got smarter.

If you’re not a member, sign up to our newsletter to get the best of Future Women in your inbox.

Equity, Diversity and Inclusion E.D.I.

- Intersectionality

- Abrahamic Religions

- East & South Asian Religions

- Indigenous Spirituality

- New Religious Movements

- Atheism & Secularism

- Anti-Black Racism

- Asian Studies

- Indigenous Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Invisible Disabilities

- Mental Illness

- Universal Design

- Mental Health Awareness

- 2SLGBTQAI+ Resources

- Gender Expression and Identity

- Gender Bias

- Gender Wage Gap

- History of Women and Gender

- Critical Thinking: Gender Critical and Gender Reveals

Evaluating Sources

Biological gender vs. gender identity: gender critical feminists, society views of gender: gender reveal parties.

- Critical Thinking: Gender and Sport

- Decolonization

Although librarians have carefully compiled these sources, there is no substitute for your own evaluation . Use the following guides to help you.

- CARS Evaluation Checklist CARS = Credibility, Accuracy, Reasonableness, and Support

- The CRAAP Test CRAAP = Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose

- Critical Evaluation of Information Sources Questions to ask, and where to find the answers when evaluating sources

Gender Critical is the belief that someone’s sex is biological, unchanging, and cannot be combined with someone’s gender identity (Observer Editorial, 2021). This belief is sometimes paired with a belief that the oppression of women is based on their biological sex, and that women have a right to have single-sex spaces. Some with this viewpoint often question or deny the recognition of trans women as women and may be against changes to gender recognition laws which "allow those who feel they are the opposite sex to change their birth certificate without surgery, hormones or a gender dysphoria diagnosis” (Samuelson, K., 2021).

“Gender-critical feminism, at its core, opposes the self-definition of trans people, arguing that anyone born with a vagina is in its own oppressed sex class, while anyone born with a penis is automatically an oppressor. In a TERF world, gender is a system that exists solely to oppress women, which it does through the imposition of femininity on those assigned female at birth.” (Burns, K., 2019).

- Burns, K. (2019). The rise of anti-trans “radical” feminists, explained. | Vox

- Lawford-Smith, H. (2020). What Is Gender Critical Feminism (and why is everyone so mad about it)? [Blog Post]

- The Observer view on the right to free expression |The Observer Editorial

- Samuelson, K. (2021). What are gender-critical beliefs? Judge-led panel ruled that such views should be protected under the Equality Act | The Week

Those who voice gender-critical views are often labelled as transphobic or as TERFs (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) by the Trans communities; even when the speaker doesn't believe themselves transphobic. The view can be as simple as stating that sex exists as a distinctive category separate from a person's gender identity. Using the lens of intersectionality, there may be cases where a person's sex and gender identity are at a cross-roads (Suissa, J. & Sullivan, A., 2021a). However, when a trans woman or man is not considered their gender and denied those gender rights, that crosses into transphobic views.

Gender critical feminists say they support LGB rights and that trans issues have overshadowed the rest of the LGBTQ+ community, which has lead to the creation of the LGB Alliance (Ricketts, A., 2021).

- Flaherty, C. (2019). The Trans Divide | Inside Higher Ed

- Intersectionality LibGuide

- Ricketts, A. (2021). Controversial campaign group registered as a charity despite its 'offensive' social media activity |ThirdSector

- Saul, J. (2020) Why the words we use matter when describing anti-trans activists | The Conversation

- Suissa, J. & Sullivan, A. (2021a). The Gender Wars and Academic Freedom | The Philosophers Magazine

One main view of many gender-critical feminists is the view women are suppressed by their biological sex, and men are the oppressor. Unfortunately, these views of men continue onto Trans Women as it is believed that the masculine way they were raised continues to affect them. This viewpoint does not carry onto trans men.

Trans author Jay Hulme described in a blog post how transphobes interact with trans men differently than trans women. He explains that for transphobes men are dangerous predators and carry that thought process to trans women. On the other hand, they see trans men as “brainwashed victims of the patriarchy” because to them being trans is something they see as fundamentally wrong and we must have been coerced into it (Hulme, J, 2019).

"As a trans man, I am, and always will be, belittled, disrespected, spoken down to, and patronised, by transphobes. After all, they think I have been brainwashed and fooled into “thinking I’m a man” what could I possibly know? What value could my words or experience possibly have? This is the same with all trans men. No matter how old they are, they are treated like children by transphobes. (Hulme, J, 2019)."

- Hulme, J. (2019). Transphobes and Trans Men [Blog Post]

Gender-critical feminists will most often point to the laws and policies around trans women using female bathrooms, changing rooms, or other female-only spaces. “When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman – and, as I’ve said, gender confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones – then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside” (J.K. Rowling, 2020). The relaxation of policies has allowed transgender people to change their identity and gender on their identification cards without requiring gender reassignment surgery and this leads gender-critical feminists to believe they will act in dangerous ways. “I read that the Scottish government is proceeding with its controversial gender recognition plans, which will in effect mean that all a man needs to ‘become a woman’ is to say he’s one” (J.K. Rowling, 2020). However, as Zanghellini, points out "a trans person can only obtain a gender recognition certificate after a relatively lengthy process, requiring them to provide evidence of having lived in their acquired gender for at least 2 years, as well as a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria" (2020, p.2).

Dr. Kathleen Stock believes that women-only areas should not allow transgender people who still have male genitalia (Doherty-Cove, J., 2018). Dr. Stock says “Most trans people are law abiding and wouldn’t dream of harming anyone. However, many trans women are still males with male genitalia, many are sexually attracted to females, and they should not be in places where females undress or sleep in a completely unrestricted way.”

“Gender-critical propaganda is almost entirely focused on the supposed depravity of trans women, citing rare cases to paint trans women as threats to women and children” (Burns, K. 2019). One area which does support the gender-critical concerns is assault by trans people within prison. However, the opposite is also true, that there are also assaults on trans people. In this section, describing cases in prison, I use the terms they use in the articles which is self-identifies as male or female, but legally/physically is a female or male.

One of the largest and most public cases in the United Kingdom, is that of Karen White who began transitioning in a men's prison to a woman but legally remained a man with male genitalia. Karen requested a transfer to a women's prison where she sexually assaulted multiple women in a short period of time (Parveen, N., 2018a). She has been sentenced to life because of these jail assaults. Karen is now at a male prison although is undergoing gender reassignment surgery (Parveen, N., 2018a and 2018b).

The Ministry of Justice (UK) updated their policy in 2016, to allow trans prisoners to transfer to the prison they identify with on a case-by-case basis and with the permission of a transgender board. The Ministry of Justice has apologised for moving Karen White to the women’s prison, saying that her previous offending history had not been considered (Parveen, N., 2018b).

In 2020, most incarcerated trans people in America were still housed in facilities based on the sex they were assigned at birth (Neus, N., 2021). In 1994, the US Supreme Court ruled that “failing protect trans people in custody is unconstitutional because it qualifies as cruel and unusual punishment” (Farmer v Brennan case) (Neus, N., 2021). A 2007 study on California correctional facilities found “s exual assault is 13 times more prevalent among transgender inmates, with 59% reporting being sexually assaulted” (Jenness, V., Maxson, C.L., Matsuda, K.N., & Sumner, J.M., 2007).

Although opponents housing people according to their gender identity fear that men will falsely claim to be transgender so they can assault women in a woman prison. Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, the executive director for the National Center for Transgender Equality believes that there is no evidence of false claims and that "there are criteria for determining that someone really is transgender... It's not as simple as simply declaring that you are transgender" (Neus, N., 2021).

- Doherty-Cove, J. (2018). 'Trans women are still males with male genitalia' - university lecturer airs controversial views | The Argus

- Jenness, V., Maxson, C.L., Matsuda, K. N., & Sumner, J. M. (2007). Violence in California Correctional Facilities: An Empirical Examination of Sexual Assault [PDF] | UC Irvine Center for Evidence-Based Corrections

- Neus, N. (2021). Trans women are still incarcerated with men and it's putting their lives at risk | CNN

- Parveen, N. (2018a). Karen White: how 'manipulative' transgender inmate attacked again | The Guardian

- Parveen, N. (2018b). Transgender prisoner who sexually assaulted inmates jailed for life |The Guardian

- Shaw, D. (2020). Eleven transgender inmates sexually assaulted in male prisons last year | BBC News

- Zanghellini, A. (2020). Philosophical Problems With the Gender-Critical Feminist Argument Against Trans Inclusion

J.K. Rowling

J.K. Rowling has been labelled a TERF and anti-trans. She wrote a blog post describing the seemingly innocent journey which led to this description - a few innocent tweets, an accidently liked tweet, and following certain twitter profiles (J.K. Rowling, 2020). She explains that these incidents began as she was learning and researching the concept of gender identity. She lists 5 reasons why she worries about new trans activism and why she is speaking up.

“So, I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe. When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman – and, as I’ve said, gender confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones – then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside. That is the simple truth.” (J.K. Rowling, 2020).

However, in her blog she questions the amount of youth who are identifying as trans and transitioning. She worries about trans women regretting the transition and detransitioing only to discover their bodies have been altered irrevocably. She is firm that ‘woman’ is not a costume or stereotypical ideas that a man thought up (J.K. Rowling, 2020) and so are many others who are gender critical. But in defining ‘woman’ or ‘trans woman’ even gender critical feminists fall into the trap of using stereotypes – if a trans woman is wearing pink and jewelry they will state that not all women are girly and the tran woman is trying to fit a stereotype. And yet, if a trans woman wears more relaxed clothes – they aren’t trying enough to ‘pass’ or appear feminine. Women come in all shapes, sizes, and styles and there is no one definition that fits all of us.

J.K. Rowling states that most gender-critical feminists do not hate trans people, and most “became interested in this issue in the first place out of concern for trans youth, and they’re hugely sympathetic towards trans adults who simply want to live their lives, but who’re facing a backlash for a brand of activism they don’t endorse” (J.K. Rowling, 2020).

However, J.K. Rowling is firmly on the side that believes your sex matters more than your gender, and her experiences as a woman can’t be defined or discussed without that distinction.

"If sex isn't real, there's no same-sex attraction. If sex isn't real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives. It isn't hate to speak the truth. (J.K. Rowling, 2020a).

- ADEGBEYE, O. (2020). Ignorance is power too: why JK Rowling deliberately repeats untruths about trans people | The Correspondent

- Calvario, L. (2020). GLAAD President says J.K. Rowling's words create dangerous environment for Transgender community (exclusive). | ET

- De Hingh, V. (2020). I’m trans and I understand JK Rowling’s concerns about the position of women. But transphobia is not the answer. | The Correspondent

- GLAAD Accountability Project - J.K. Rowling

- Montgomerie, K. (2020). Addressing The Claims In JK Rowling’s Justification For Transphobia | Medium

- Rowling, J.K. (2020). Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues [Blog Post]

- Rowling, J.K. [@jk_rowling] (Jun 6, 2020a). Tweet. | Twitter

Kathleen Stock

Kathleen Stock was a philosophy professor at the University of Sussex for 18 years. Students protested, created poster campaigns, and called for her resignation. Kathleen Stock began speaking about her gender critical views in 2018 and since then has received bullying from a small group of extreme colleagues which combined with the students protests, lead to her quitting the University of Sussex in 2021 (Barnett, E., 2021). She says that her views are being misconstrued and that she is not a bigot or transphobic - that she is sympathetic to people who feel they are not in the right body (Moorhead, J., 2021). However, Kathleen is concerned and opposes “the institutionalisation of the idea that gender identity is all that matters – that how you identify automatically confers all the entitlements of that sex” (Moorhead, J., 2021).

In 2021, Kathleen published “Material Girls” a book which sought to answer the question “do trans women count as women” (Moorhead, J. 2021). Her view of women is at the biological level, and therefore trans women can have the gender identity of a woman but cannot be a woman (Stock, K., 2022). She worries that trans woman are no longer required to have reassignment surgery, take hormones, or appear as a woman to use woman only space – that a man simply needs to say they feel they have a female gender identity (Stock, K., 2018). In a review of “Material Girls”, Stock is described as “concerned about harms to non-trans women that ensue when gender identity displaces sex as the criterion for demarcating access to women’s sports and women’s only spaces like locker rooms, bathrooms, shelters, and prisons” (Briggle, A., 2021). Stock points out that not all trans women are bad however in the book most mentions of trans women are not in a positive light. She highlights Karen White who is indeed the transexual pretender, rapist, and violent offender that she worries most trans women are – but is it in fact that White has a penis and is a trans women or is it that White is a convicted pedophile detained for multiple rapes and other sexual offenses against women (Briggle, A., 2021)? She has also written journal articles and blog posts on the topics of biological sex, and academic freedom to discuss gender.

Since quitting the University of Sussex, Kathleen has been using her freedom to voice gender critical views and fighting out against institutional silence over gender discussions and debates. She said she is the voice for many of her colleagues who are unable to speak up about these issues without being censored professionally and by their employer (Women's Liberation Now, 2020 & Barnett, E., 2021). An open article from 12 philosophy scholars are alarmed over recent “proposals to censure or silence colleagues who advocate certain positions in these discussions, such as skepticism about the concept of gender identity or opposition to replacing biological sex with gender identity in institutional policy making” (12 Leading Scholars, 2019).

- (2021). Kathleen Stock: University of Sussex free speech row professor quits | BBC News

- 12 Leading Scholars. (2019). Philosophers Should Not Be Sanctioned Over Their Positions on Sex and Gender | Inside Higher Ed

- Adams, R. (2021). Kathleen Stock says she quit university post over ‘medieval’ ostracism | The Guardian

- Barnett, E. (2021). Women's Hour: Professor Kathleen Stock; Royal Ballet principal Leanne Benjamin; Richard Ratcliffe. | BBC Radio

- Briggle, A. (2021). Which Reality? Whose Truth? A Review Kathleen Stock’s Material Girls: Why Reality Matters for Feminism, Adam Briggle | Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective

- Moorhead, J. (2021). Kathleen Stock: taboo around gender identity has chilling effect on academics | The Guardian

- Stock, K. (2018). Changing the concept of “woman” will cause unintended harms | The Economist

- Stock, K. (2022). The Importance of Referring to Human Sex in Language. | Law and Contemporary Problems

- Suissa, J., & Sullivan, A.. (2021b) The Gender Wars, Academic Freedom and Education | Journal of Philosophy of Education

- Women's Liberation Now. (2020) 11 Women in Academia Censored or Threatened [Blog Post]

Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer wrote “The Female Eunuch”, which became an international bestseller and is considered an important text in the feminist movement. The book describes women as eunuchs or castrates, robbed of their natural energy by the patriarchal society. “Greer famously drew attention to deeply entrenched cultural constructs that linked sex to shame and disgust, calling out the hypocrisy of a society that blamed women for men’s misogyny” (Nelson, C., 2020). Her views on what makes a woman a woman are clear and do not include transgender women. Germaine has stated that men are welcome to have gender reassignment to make them more comfortable in their body, that is fine but that does not make them a woman (BBC, 2015). Although she has backed away from her transphobic views in various interviews, her underlying thoughts of transgender women are the unfairness that “a man who has lived for 40 years as a man and had children with a woman and enjoyed the services—the unpaid services of a wife, which most women will never know... then decides that the whole time he’s been a woman” (Wahlquist, C., 2016). These views match those of the gender critical feminists and Germaine Greer’s book and views may be one of the foundations on which the gender critical movement was created.

- BBC. (2015). Germaine Greer: Transgender women are 'not women' - BBC Newsnight [YouTube]

- GLAAD Accountability Project - Germaine Greer

- Nelson, C. (2020). Friday essay: The Female Eunuch at 50, Germaine Greer's fearless feminist masterpiece | The Conversation

- Wahlquist, C. (2016). Germaine Greer tells Q&A her trans views were wrong, but then restates them |The Guardian

Gender has become a controversial topic as our understanding of the topic has grown beyond a binary system based on biology. Do we allow discussions of gender in academic situations? Is there a way to hold discussions about gender while maintaining a welcoming and inclusive environment?

Gender has historical significance through the lens of many different disciplines which we should be able to remember and discuss. Grace Lavery, a trans woman and professor of 19 th -century British literature at Berkley, says “Historically speaking, issues around sexuality and gender have been of relatively marginal importance for philosophy departments, and relatively significant importance for humanities departments and the literary or cultural studies” (Burns, K. 2019). However, LGBTQ+ is not a new phenomenon, it is only in the most recent centuries that the choices and lifestyle of LGBTQ+ communities has been allowed to be free. By discussing history as the binary, we mistakenly believed it was some of the LGBTQ+ communities may feel left out, dismissed, or suppressed.

There must be a way to balance understanding our historical gender perspective and the significance that perspective had on literature, historical decisions, politics, and the economy (for example) with respecting our current understanding of gender identities, including LGBTQ+ people and not causing harm to any one. Are difficult conversations appropriate for the academic environment? And how do we make sure difficult conversations can be discussed, fair and yet not harm others?

Informing parents of the sex of their fetus is the step in “reinforcing misinformed sex and gender binaries” which creates expectations and structures which tighten social gender constraints instead of loosening them (Oswald, F., Champion, A., Walton, K., & Pederson, C.L., 2019). The reinforced rigid ideas about gender are “highlighted through these visual thematic representations – girls are pink, boys are blue, and these categories are very distinct” (Oswald, F., Champion, A., Walton, K., & Pederson, C.L., 2019). The mother who sparked the gender reveal trend “now believes the gender-reveal party has helped conservatives create increasingly restrictive pink and blue boxes for children, which support their anit0liberal agenda” (Schiller, R., 2019).

The focus on gender can hurt the transgender and non-binary communities for while society is -becoming more open minded to gender expression, and gender identity in older children, teens and adults – it also is becoming hyper fixated on the gender of fetus’s. “At least when the child is born, you are getting al l the information at once: the sex, the colour of their hair, who they look like, how long they are what their heart rate is. With the gender reveal you have isolated one aspect of this person” (Jenna Myers Karvunidis in Schiller, R., 2019). The parties elevate the gender as central to the fetus’ future identity and begins the journey of stereotypes, bias, and a disconnect with society’s openness to the LGBTQ+ community.

Although they are considered gender reveals, “they actually proclaim the likely sex of the fetus based on the ultrasound scan to detect the presence or absence of a penis and/or a maternal blood test to identify the fetus’s chromosomes” (Jack, A, 2020). As the LGBTQ+ community has shown us, the gender of a fetus is it’s sex, as gender identity and expression are very different things. Jenna Myers Karvundis, the creator of gender reveal parties, says “plot-twist, the world’s first gender-reveal party baby is a girl who wears suits” (Wong, B. 2019). A new trend is to hold a redo gender reveal party, for when the baby’s gender no longer matches their older selves. The Gwaltney family created a gender reveal party to show off their non-binary child, their new name and their pronouns correcting the mistaken girl gender reveal they did when they were pregnant (Lee, A., 2020). Coming out as Trans parties are gaining more popularity and are considered celebratory of gender self-determination in a direct contrast with infant gender reveal parties (Dockray, H., 2019).

There are also concerns growing over the reactions of some parents and the disappointment they feel when a gender they do not prefer is revealed. The evolution of sex-selection technologies adds a layer of complexity to the already fraught social underpinnings of gender reveal parties and the assumed correlation of sex and gender (Jack, A., 2020). Sex-selective abortions or infanticides still occurs in significant numbers globally, although it is seen as unethical worldwide (Jack, A., 2020).

In rebellion against society’s views on gender, some families are raising their children gender-free. Kori Doty believes in giving her child space to identity and present their own gender, based on their own ideas and opinions (in Matei, A., 2020). In the United States, six states allow parents to label their baby’s gender as X on their birth certificates, however this gender-free parenting style still gets a lot of pushback (Bracken, A., 2020). Some forms of this type of parenting include not reveal their child’s gender to the outside world until they are ready to identify for themselves, others allow their child toys, clothes and activities that cross gender lines (Bracken, A., 2020). Gender-free parenting works best in as early as possible, as children are shaped by their early experiences.

- Blunt, R. (2019). The dangers – physical and psychological – of gender reveal parties | BBC News

- Bracken, A., (2020). How to Raise a Gender-Neutral Baby | Parents

- Dockray, H. (2019). Gender reveals are awful. (Trans)gender reveals are a different story. | Mashable

- Feuerherd, B. (2019). Plane crashes after unloading 350 gallons of pink water in gender reveal stunt | New York Post

- Giesler, C. (2018). Gender-reveal parties: performing community identity in pink and blue | Journal of Gender Studies

- Haller, S. (2019). Hungry Hippo gender reveal deemed 'the worse' was 'one of the happiest days' for the couple | USA Today

- How to Raise a Child Without Imposing Gender | The New York Times

- Jack, A. (2020). The Gender Reveal Party: A New Means of Performing Parenthood and Reifying Gender under Capitalism | International Journal of Child, Youth, & Family Studies

- Lapin, T., (2021). New York dad-to-be killed by exploding gender reveal device | New York Post

- Lee, A. (2020). A mom threw a belated gender reveal party for her transgender son 17 years after she 'got it wrong' | CNN

- Licea, M. (2019). Car bursts into flames during gender reveal joyride fail. | The New York Post

- Matei, A. (2020). Raising a theybie: the parent who wants their child to grow up gender-free | The Guardian

- McLaughlin, E.C. (2019). Partygoers thought they'd built a clever gender reveal device. It turned out to be a deadly pipe bomb. | CNN

- Morales, C., & Waller, A., (2021). Gender Reveal Party Wildfire. | The New York Post

- Oswald, F., Champion, A., Walton, K., & Pederson, C. (2021). Revealing more than gender: Rigid gender-role beliefs and transphobia are related to engagement with fetal sex celebrations. | Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity

- Schiller, R. (2019). Why the mother who started gender-reveal parties regrets them | The Guardian

- Smith, R. (2020). The Growing Horror of the Gender Reveal Party | Vogue

- Sparks, H. (2020). Gender reveal goes horribly wrong after sister hit with dart |New York Post

- Steinbuch, Y., (2021). Two killed when plane used for gender reveal crashes in Cancun |New York Post

- Wong, B. (2019). This Woman Helped Popularize Gender Reveal Parties. Now There's A 'Plot Twist.' | Huffpost

- “Raising Baby Grey” Explores the World of Gender-Neutral Parenting | The New Yorker

- << Previous: History of Women and Gender

- Next: Critical Thinking: Gender and Sport >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 8:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ufv.ca/EquityDiversityInclusion

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Reframing the discourse on race, gender and identity

“I seem these days always to be in search of what is affirming,” said Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie . “I am desperately drawn to what is meaningful, what is human, what is beautiful.”

Upon accepting the USC Norman Lear Center ’s 2019 Everett M. Rogers Award , the Nigerian author, cultural critic and feminist noted how deeply encouraging it was to be in the company of past honorees and their scholarship.

Adichie is the author of six books, including Americanah , which won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was named one of The New York Times’ Top 10 Best Books of 2013. Her “ The Danger of a Single Story ” is one of the most-watched TED talks of all time. A MacArthur “Genius” Fellow and a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, she was named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World in 2015.

On Feb. 7, a crowd of hundreds gathered in the Wallis Annenberg Hall Forum as Adichie was honored for her inspiring contributions to the global conversation about gender, race and identity.

Lear Center Director Martin Kaplan hailed Adichie for her gifts as a storyteller to inspire and empower.

“Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie uses stories to grow our empathy and our aspirations,” Kaplan said. “In her fiction and her essays, in her novels and her talks, she weaves her insights into the narrative of human experience.”

Dean Willow Bay echoed Kaplan’s praise for the impact of Adichie’s storytelling. “We must be deliberate in recognizing and celebrating the power of stories, but we must also be deliberate in naming and celebrating our storytellers ,” Bay said.

Bay also introduced special guest presenter Danai Gurira, an actor, playwright and activist best known for her roles Okoye in the film Black Panther and as Michonne from the television series The Walking Dead .

In introducing Adichie, Gurira spoke of their work together in adapting Americanah into a television miniseries. She also recognized how deeply Adichie’s writing has spoken not only to her own journey, but to countless others.

“Her body of work proves that great storytelling, storytelling that is courageous and unflinchingly pursues the truth, storytelling that delves with specificity and complexity into places both uncomfortable and unexpected,” Gurira said. “That sort of storytelling is universally appealing and shatters seemingly insurmountable walls about whose stories get to be boldly told. That sort of storytelling forms bridges, bringing us all that much closer together on equal footing.”

In Adichie’s own words, here are four takeaways from her remarks, which included an audience Q&A.

Fake news and the what ifs

As a storyteller, I’m interested in the singular and the specific, because from this, I believe springs the universal. And I’m also interested in the idea of what is possible. I read all genres, I like to think of myself as a very catholic reader, but one genre that I’ve had very great difficulty getting into is speculative fiction. And yet I found myself thinking in speculative terms lately. So what if? What if everyone simply refuses to use the expression “fake news”?

Because it is saying that over and over again that gives it legitimacy. There is inaccurate news, there’s biased news, there's incomplete news, but that expression “fake news” is heavy with the ugly connotation that journalism is some kind of deliberate conspiracy. It is not.

And the man who has made that expression, “fake news,” so common really just uses it to mean news that he does not like. Whether it is true or not is irrelevant. What if? What if journalists all over this country decided to burn, forever, that idea of false equivalences?

What if? What if instead of focusing on balance, we focused on truth? What if we stopped pretending that both sides of an issue are equal, when they are not? What if we decided that news should not entertain us, but should inform us and educate us? What if we all agreed that we have to be nimble and alert and clear-eyed and skeptical, that we have to be active rather than reactive?

The link between critical thinking and empathy

There are, today, valid and worrying concerns that face our future as humans. There’s inequality, gender, racial, economic, there’s climate change [and] artificial intelligence, but I find myself most worried about the possible death of critical thinking, and consequently, the death of empathy.

Because both are central to how we understand and deal with all of the other challenges we face. It might seem odd to connect critical thinking and empathy, but the two are related. If we are able to think critically, then we’re more able to exercise empathy. Critical thinking is, quite simply, the ability to think clearly. To hold ideas in your mind, to weigh them. To dissect them. And if we’re able to do this, then we're able to truly see other human beings.

Kalu Makan says that to read a book is to be alive in a body that is not your own. And I would broaden that to storytelling, to listen to stories is to be alive in a body that is not your own.

That, for me, is the best example of that link between critical thinking and empathy. To be alive in a body that is not your own. To hear another person’s story. To truly see another person. And this matters. It matters because empathy and critical thinking are starting points, will radically change the way we deal with everything.

‘Stop canceling people’

On the one hand, there’s something I find very encouraging about activism, about young people who are all really, I think, coming from a well-meaning place, which is that they want better for everybody. What worries me is that … it very often feels quite extreme in the way that it seems like people no longer think of people as complex humans, that one slip and you’re done, right? And people say you’re canceled and you’re no longer relevant, and it seems to me not a very productive way of thinking about these things, and also really not practical because we're all flawed, and in some ways, then it becomes a question of how many flaws can you take?

So, what I would say … is it’s not so much that you shouldn’t call people out … it’s also that maybe you should read a little more. And I’m not kidding. And by read a little more, I mean don’t have an opinion until you look at the primary source…. And maybe just read things that are outside of social media. I think sometimes context is lacking in the way that things are seen….

The people who are canceled are actual human beings who often mean well…. I was talking to a young person the other day and I said, “Well, do you want to know what they really think?” She said, “No, no, no, I already know the world.” So that’s bad. It’s almost as though … there’s no room for nuance, there’s no room for sort of expanding on what one word means.

Listening, reporting and humanizing

[W]henever the foreign journalist is going to Africa and sometimes they sort of think that I have all the answers to things, right? … [T]hey’re like, “So, what should we do when we go to Africa?” And I love having that power, because of course I don’t have all the answers, right? But I kind of pretend I do. I’m like, “Yes, well, the thing to do when you go to Africa...” But really what I say is just if it’s possible to put everything you know about Africa in a backpack, right? And then leave that backpack behind when you go. That’s the way to go. It’s just to have an open mind.

I think that often when you’re reporting on something, you find yourself trying to make your story aligned to what you already have in your mind…. [I]n general, I would say the problem with stereotypes really, again, is not that they’re false ... it’s that they’re incomplete. And I think what's important in, especially covering communities that are powerless, communities that are marginalized, is that the humanizing of those communities has to be, in my opinion, center stage.

[T]he thing that surprises you about people, the thing that doesn’t align with what you expect, often those are the things that humanize people, and in some ways, I think fiction writing is similar…. [I]t’s things that surprise me about humanity that I make note of, and those are the things that I find to be worthy of storytelling. And in some ways, I think journalism is similar, and I think that’s how we ultimately humanize people and end up not making them stereotypes.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 2019 Everett M. Rogers Award Honoree Internationally acclaimed author and global humanitarian Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is being honored with the 2019 Everett M. Rogers Award. Dean Willow Bay and Marty Kaplan of the Norman Lear Center provide opening remarks, followed by Danai Gurira, actor on Walking Dead and Black Panther. Adichie will be honored for reframing the discourse on race, gender and identity. Join #theafricanarrative Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Danai Gurira USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center Posted by USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism on Thursday, February 7, 2019

For more photos from the event, see the Flickr page .

About the Everett M. Rogers Award

Presented since 2007 on behalf of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism’s Norman Lear Center, the award honors the late USC Annenberg professor Everett M. Rogers, whose Diffusion of Innovation is the second-most cited book in the social sciences. The award committee is listed here .

This piece was also published in the Spring 2019 issue of the USC Annenberg Magazine.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to quick search

- Skip to global navigation

- Return Home

- Recent Issues (2021-)

- Back Issues (1982-2020)

- Search Back Issues

The Challenge to Critical Thinking Posed by Gender-Related and Learning Styles Research

Permissions : This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy .

Recent national reports on the quality of higher education consistently rank the development of critical thinking skills as a primary objective for university curricula and instructors (Association of American Colleges, 1985; National Institute of Education, 1984). Rare indeed is a curricular reform that does not genuflect in the direction of improved critical thinking. Faculty too are often quick to pay allegiance to the importance of critical thinking for their classrooms. Fortunately, however, such movements typically generate thoughtful skepticism as a byproduct of their success.

Two streams of modern research threaten the popularity of critical thinking, particularly certain forms of critical thinking. This paper attempts to describe the nature and limits of this challenge. The first two sections describe specific criticisms of critical thinking; the final section attempts to respond to those criticisms. Our objective is to examine the extent to which gender-related and learning styles research programs demonstrate the inappropriateness of critical thinking instruction for certain students.

Gender-Related Research and Critical Thinking

Moral development studies by Piaget, Kohlberg, and Erikson define development as movement toward autonomy and autonomous judgment. Women, however, tend to have much more tenaciously embedded relationships with others than do men and to develop a mode of judgement that is contextual. Thus, women are often perceived as deviant or deficient from the perspective of developmental models derived from male subjects (Gilligan, 1987). Developmental models based on male subjects may consequently be misleading for either descriptive or prescriptive purposes.

In an effort to rectify this problem, Carol Gilligan’s In A Different Voice (1982) presents a moral development model more appropriate for women. Gilligan’s model focuses on notions of responsibility and care, in sharp contrast to the morality of rights developed by Kohlberg (1981) and Piaget (1948). According to this argument, just as previous studies of moral development concentrated almost exclusively on the developmental stages of men, conceptions of truth and knowledge have also been shaped throughout history by male-dominated majority culture (Belenky et al., 1986). Men have constructed the prevailing theories, written the history, and established the values that have become the guiding principles for both men and women.

This domination of developmental models by male perspectives has affected several disciplines. In sociology (Smith, 1974), history (Lerner, 19.79), anthropology (Slocum, 1980), and other social sciences (Spender, 1981), women have been studied in terms of their deviance from the male norm, or have been subsumed by the male-biased research paradigm focusing on the pursuit of objectivity and the assumed gap between the knower and the object of study. Relatively little attention or value has been accorded to the modes of knowing, learning, and valuing that may be specific or common to women. Hence, an important objective of gender-related research is to describe habits of mind common to women and to determine ways to approach these differences in the classroom.

At the forefront of such research is Women’s Ways of Knowing (Belenky et al., 1986). This work is based on interviews with 135 women, 90 from colleges and 45 from family agencies that assist those seeking help with parenting. The women interviewed represented various class and ethnic backgrounds. A recurring theme of the interviews was the feeling of alienation many women experience in educational environments. A dearth of reinforcement and praise, cited in many interviews, often led these women to believe themselves incapable of intelligent thought. Feelings of self-doubt and intellectual inferiority are almost inescapable for many female students.

Exacerbating these feelings is the emphasis on abstract, non-contextual thought in higher education (Belenky et al., 1986). Personal experience and contextual knowledge provide the majority of these women with their most reliable sources of information. Many cited out-of-school incidents as their most educationally rewarding experiences, with childbearing and -rearing as oft-cited examples. While highly valued among women, however, these experiences often wield little clout in a university setting. Given their discomfort with abstract thought, many of the female interviewees actively resisted critical modes of analysis favored in the university. Many of them construed critical thinking as an adversarial activity and, therefore, found it uncomfortable and unrewarding. The majority of interviewees reported that they learned best by trying to understand others’ positions (Clinchy, 1987).

This way of knowing frequently implies a personal relationship between the knower and the object to be known. The approach to research used by many feminist scholars reflects this emphasis on sharing. For example, in “A Feminist Research Ethos” (1988), Ann Bristow and Jody Esper contrast the male research approach of interrogating subjects with the feminist approach of conducting a dialogue with their subjects. In contrast to male researchers’ attempts to remain aloof from the subjects of their studies, feminist researchers try to minimize the distance between themselves and those they are studying (Malhotra, 1988). The adversarial procedures that some women view as part of critical thinking are not conducive to forming the close relationships that female researchers seek with their interviewees or respondents.

In the study by Belenky et al., the subjects’ disdain for what was defined as “critical thinking” extended beyond academic settings. Many commented that men are adversarial and combative even in casual conversation. The women in this study, on the other hand, reported a preference for conversations that were sharing and collaborative. Critical thinking, to these women, is synonymous with “male logic,” a thought process they find adversarial uncomfortable, and alienating.

Based on these interviews, the authors of Women’s Ways of Knowing conclude that women prefer less critical modes of thought. They term critical, analytic thought processes “separate knowing,” and suggest that “connected knowing” is a thought process more suited to women. Connected knowers are not aloof; unlike separate knowers, they attempt to “get behind the other person’s eyes.” Because connected knowing implies a relationship between the self and the subject or object of knowledge, most women feel quite comfortable with such a style of knowing.

In a conference at the University of Chicago, one of the book’s authors, Blythe McVicker Clinchy, recommended that women be taught un critical thinking: “I am saying that many women would rather think with someone than think against someone.” Connected knowing’s emphasis on acceptance over evaluation makes it an appropriate means to such an end (Clinchy, 1987).

Thus, the final recommendation of much of the gender-related research, particularly Women’s Ways of Knowing, is for educators to emphasize connected knowing as acceptable and even desirable. By trying to see the world from the perspective of those being studied or evaluated, we are, according to this argument, better able to comprehend and accept. In contrast, forcing women to comply with fundamentally “male” ways of knowing, such as abstract, objective thought, may undermine women’s sense of intellectual self-worth and ultimately alienate them from the educational process. These claims will be evaluated in the final section of this paper.

Learning Styles Research and Critical Thinking

Avoiding potential alienation in the classroom also provides much of the impetus for learning styles research. Most who tout the importance of learning styles recommend that learning and teaching styles be strategically matched for academic success. Matching entails identifying a student’s learning style and then selecting a teaching style that complements it. This advice is based on the assumption that one must meet students where they are, not where the teacher might like them to be.

Scott G. Paris (1988), for instance, urges teachers to apply a model of instruction compatible with the students’ learning model or metaphor. The key here is to create a match among the learner’s task, context, and strategy so that the required actions fit into the learner’s ongoing behavior. His rationale for advocating matching among educators and learners is to encourage students to employ their learning strategies with greater frequency, even when they are working independently of the instructor. Significantly, Paris notes that matching is desirable only when it reinforces a positive learning style.

Almost all research advocating the matching of learning and teaching styles claims that matching enhances performance on tests. To improve success in college, “college students … should choose professors whose teaching styles complement their own learning styles” (Radebaugh et al., 1988). The findings of Charkins et al. (1985) corroborate such research by concluding that achievement and attitude are positively affected by a matching strategy.

Efficiency is sometimes provided as a justification for matching. Students who are strategically matched with their professors require fewer iterative repetitions to master the material. In one study, matched students needed one to three repetitions, compared to four to seven repetitions required by mismatched students, to reach a particular level of mastery (Pask, 1988).

Other research promotes matching as an ideal way to cultivate selfconfidence in learners (Charkins et al., 1985; Claxton and Murrell, 1987; Paris, 1988). Poorly prepared students seem to benefit the most from this approach. When these learners are initially confronted with a confusing teaching style, they risk failure, which can discourage them and jeopardize their future academic success. Matching thus appears to facilitate their development primarily by affirming their sense of self-worth.

Evaluating the Challenge to Critical Thinking

Gender-related research.

Both gender-related and learning styles research are very concerned with creating classrooms that engage rather than alienate learners. An educational approach based on male perspectives is inadequate for many female learners in most classrooms. Similarly, a learning style that addresses some students shortchanges other learners who could be matched with a more compatible style.

While we have much to learn from both gender-related and learning styles research, we should not exaggerate their implications. Research detailing differences in ways of knowing and learning styles is marvelously descriptive. Indeed, it reminds instructors that their students are not a monolithic glob. The bulk of this research, however, ultimately fails to offer educators a prescription for encouraging students to improve their ways of knowing or their learning styles.

Gender-related research, while undoubtedly intended to benefit women, contains the potential for ultimately harming them. If the recommendations of Blythe Clinchy are widely embraced, for example, necessary skills of analysis and evaluation may be taught to women in a cursory fashion. Sensitive instructors may hesitate to provide women critical feedback on a paper or an examination because they do not want to make their students uncomfortable.

It is important to note that the distaste for critical modes of thought expressed by so many female interviewees may be misdirected contempt. Much of their discomfort was based on having observed hostile males in conversations or in classrooms. Indeed, casual observation confirms that in academic and social settings, men’s behavior is typically more aggressive and bombastic than women’s. Bellicose males, however, are not necessarily exemplary critical thinkers; they are just noisy. Critical thinking should not be confused with gratuitous aggression.

Thus, a recommendation to teach women uncritical thinking may be entirely unnecessary. Instead, a recommendation that pugnacious conversationalists and certain professors moderate their aggression might be a more appropriate inference from gender-related research programs. Certainly, demonstrating that critical thought and engaging conversation are not mutually exclusive is more beneficial than excusing the majority of women from the realms of critical thought. One of the essential steps in critical thinking is examining the assumptions or perspectives guiding behavior or arguments as a preliminary step toward evaluation. When one becomes “connected” in this way, the resulting evaluation is more fair. Connected knowing can, thereby, be a step toward better critical thinking.

Another recommendation made in Women’s Ways of Knowing is that academics place more stress on personal experience as a basis for judgment. An over-emphasis on personal experience, in an effort to engage more women students in effective learning, could be a very limiting strategy, however. While personal experience can be extremely useful as a means of defining a particular idea or concept, heavy reliance on personal experience could be a great educational disservice to women. Thus, when women mention personal experience in class or in papers, they should not be denounced for lack of academic sophistication. Instead, they should be reminded that personal experience can deceive. Alerting students to the reality that personal experience can be a precarious compass by which to chart life is far more valuable than invariably accepting their personal experience as reliable evidence, even when that acceptance emanates from a desire to affirm rather than alienate.

Implying that critical thinking denies the necessity of understanding another’s position is to attack a caricature of critical thinking. Female subjects in gender-related research studies convey an intense preference for understanding the other person’s point of view. Critical thinking shares that desire. If one does not understand different sides of an issue, it is unlikely that the analysis of the issue will be worthwhile (Browne and Keeley, 1986; Meyers, 1986).

Learning Styles Research

Restricting critical thinking to a select body of students based on inferences from learning styles research can restrict students’ development. While the intentions behind matching learning and teaching styles are noble, the wisdom of matching is easily exaggerated. In the extreme, matching could lead to complacency and stagnation among learners. Instructors’ attempts to match teaching and learning styles could unnecessarily limit students’ acquisition of other, perhaps temporarily uncomfortable, learning styles.

Clearly, clumsy mismatching may create even greater risks, but strategic mismatching, using critical thinking, deserves consideration (Doyle and Rutherford, 1984). Through selective mismatching, professors can equip students for a variety of learning styles that they are apt to encounter later in their educational experience: “Students will encounter professors who teach and test for comprehension and memorization or other styles. Accommodating a student’s learning style might not serve him well when he is taught and tested using different styles” (Doyle and Rutherford, 1985).

Research advocating matching often relies heavily on the rationale that matching is conducive to academic success. But poorly specified dependent measures are common in such research. For example, improved scores on objective tests are repeatedly cited as evidence that matching positively affects students. Particular types of tests, however, tend to measure the success of one learning style more favorably than others. Thus, if professors encourage higher order thinking throughout the semester, but use objective tests, as opposed to essay tests, they are probably testing for a learning style they did not actively encourage. If the professor and the students have been matched for higher order thinking, such test results are ill-equipped to measure the relative success or failure of the match (Schmeck, 1981).

Any matching strategy that results in improved scores on objective tests provides strong evidence for benefits of matching only if we accept a definition of “success” that entails high scores on objective examinations. If, however, we decide that academic success is more appropriately defined as facility with complex, contemplative thought, many of the studies encouraging matching lack persuasive evidence. As Anthony Grasha (1984) perceptively notes, “To date, researchers have not delineated what constitutes content achievement, learner satisfaction, applications of content, abilities to think creatively, problem-solving or decision-making skills, self-concept, the types of learning methods used in continuing education, the quality of life for the learner and the instructor, or the motivation of people to pursue continuing education” (Grasha, 1984). In short, matching may or may not be desirable depending upon how dependent variables such as success and improvement are defined. Until more specific definitions are forthcoming, educators should proceed with caution prior to adopting matching strategies.

Determining the one “best” solution to teaching all levels of learning abilities in one classroom is difficult, if not impossible. Invariably, single solutions will benefit some at the expense of others (Good and Stipek, 1983). Instead of encouraging professors to match their teaching styles to the learning styles of their students, a more pragmatic approach would be to encourage professors to instruct in a way that encourages several styles, including critical thinking. Such intervention “will create a positive alignment of styles that will enable students to perform well. Also, such practices will better prepare students for other classes and improve the quality of teaching at the same time” (Ramsden, 1988). Such a strategy also circumvents boredom, a sure route to alienation in a classroom. Repetitive use of a single learning style is not conducive to effective pedagogy (Grasha, 1984).

Learning styles and gender-related research do deserve integration into classroom praxis. What they warrant, however, is a moderate approach that is cognizant of their potential misuse as well as of their advantages. A certain resignation characterizes much of the research on learning styles and gender. Rather than encouraging educators to intervene in students’ educational experience, the recommendation is to accommodate. But educators should not fear motivating students toward change. Intervention, in an effort to encourage movement toward more complete appreciation of alternative ways of knowing, including critical thinking, is a crucial responsibility of educators. Students move from one level to another only with guidance and practice. Ideally, professors serve as bridges between levels. If the purpose of education were merely to reassure students that the level at which they are currently functioning is satisfactory, a university education would lose much of its potential as a stimulus for personal growth.

- Arlie, D. et al. (1984). Cognitive style as a predictor of achievement: A multivariate analysis. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Communication Association, San Francisco, CA.

- Association of American Colleges (1985). Integrity in the college curriculum. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges.

- Belenky, M.F., Clinchy, B.M., Golderger, N.R., & Mattuck, J.T. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing. New York: Basic Books.

- Bristow, A., & Esper, J. (1988). A feminist research ethos. In Nebraska Sociological Feminist Collective, A feminist ethic for social science research. Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Browne, M.N., & Keeley, S.M. (1986). Asking the right questions: A guide to critical thinking. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Charkins, R.J., O’Toole, D.M., & Wetzel, J.N. (1985). Linking teacher and student learning styles with student achievement and attitudes. Journal of Economic Education, 16, 111-120.

- Claxton, C.S., & Murrell, P.H. (1987). Learning styles: Implications for improving educational practices. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Higher Education.

- Clinchy, B.M. (1987). Separate and connected knowing and undergraduate teaching and learning. Paper presented at the University of Chicago Meeting on Critical Thinking and Context: Intellectual Development and Interpretive Communities, Chicago, IL.

- Clinchy, B.M., & Zimmerman, C. (1985). Connected and separate knowing. Paper presented at Symposium on Gender Differences in Intellectual Development: Women’s Ways of Knowing at the Eighth Biennial Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, Tours, France.

- Doyle, W., & Rutherford, B. (1984). Classroom research on matching learning and teaching styles. Theory Into Practice, 23, 20-25.

- Dunn, R. (1988). Commentary: Teaching students through their perceptual strengths or preferences. Journal of Reading, 31, 304-309.

- Gilligan, C. (1987). In a different voice. In Bellah (Ed.), lndividualism and commitment in American life. New York: Harper & Rowe.

- Good, T.L, & Stipek, D.J. (1983). Individual differences in the classroom: A psychological perspective. In Fenstermache (Ed.), Individual differences and the common curriculum. Eighty-second yearbook of the national society for the study of education, Part I. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Grasha, A.F. (1984). Learning Styles: The journey from Greenwich Observatory (1796) to the college classroom (1984). Improving College and University Teaching, 32, 46-53.

- Kohlberg, L. (1981). The philosophy of moral development. New York: Harper & Row.

- Malhotra, J. (1988). In Nebraska Sociological Feminist Collective, A feminist ethic for social science research. Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Meyers, C. (1986). Teaching students to think critically. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, C. (1988). Cognitive learning strategies: Implications for college practice. In Weinstein et al., (Eds.), Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment, instruction, and evaluation. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc.

- National Institute of Education. (1984). lnvolvement in learning: Realizing the potential of American higher education. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Humanities.

- Paris, S.G. (1988). Models and metaphors of learning strategies. In Weinstein et al., (Eds.), Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment , instruction, and evaluation. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc.

- Pask, G. (1988). Learning strategies, teaching strategies, and conceptual or learning style. In Schmeck, R.R., (Ed.), Learning strategies and learning styles. New York: Plenum Press.

- Piaget, J. (1948). The moral judgment of the child. New York: Free Press.

- Radebaugh, M.R., Leach, J.N., Morrill, C., Shreeve, W., Slatton, S. (1988). Reading your professors: A survival skill. The Journal of Reading, 31, 328-332.

- Ramsden, P. (1988). Context and strategy: Situational influences on learning. In R.R. Schmeck (Ed.), Learning strategies and learning styles. New York: Plenum Press.

- Schmeck, R.R. (1981). Improving learning by improving thinking. Educational Leadership, 38, 384-385.

- Slocum, S. (1980). Woman the gatherer: Male bias in anthropology. In S. Ruth (Ed.), Issues in feminism (pp. 239-252). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Smith, D. (1974). Women’s perspective as a radical critique of sociology. Sociological Inquiry, 44 (1), 7-13.

- Spender, D. (1981). The gatekeeper: A feminist critique of academic publishing. In H. Roberts (Ed.), Doing feminist research. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 November 2023

Systemic thinking and gender: an exploratory study of Mexican female university students

- Marco Cruz-Sandoval ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-4023 1 ,

- Martina Carlos-Arroyo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5987-1041 2 ,

- Araceli de los Rios-Berjillos 3 &

- José Carlos Vázquez-Parra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9197-7826 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 807 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

520 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

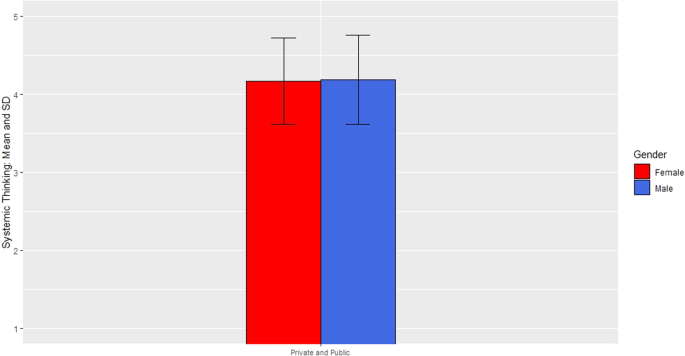

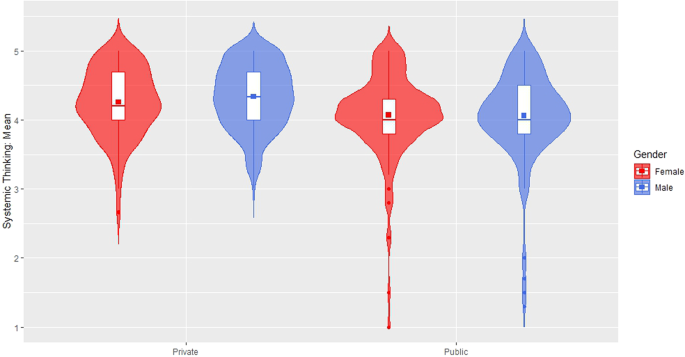

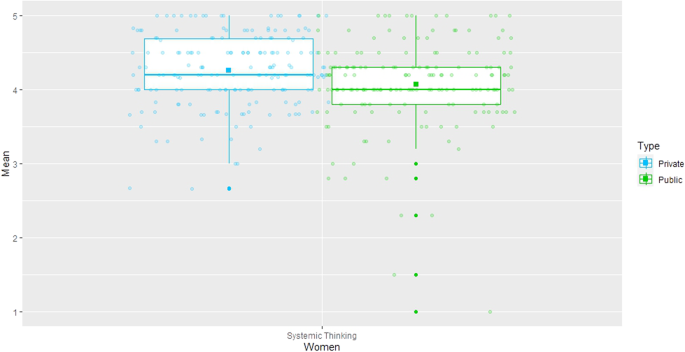

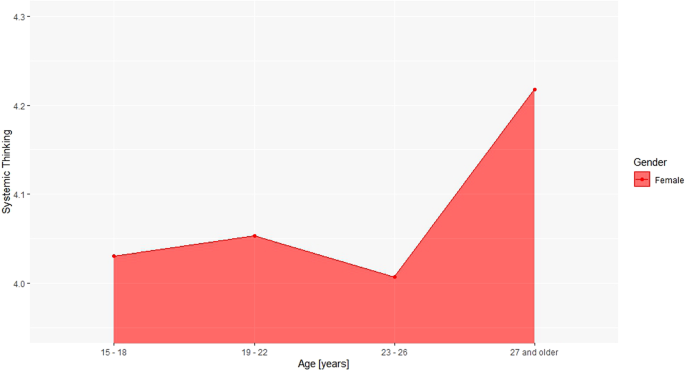

Metrics details