Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

A hub for quantum

Top stories.

- University of Chicago chemists discover a key protein in how lysosomes work

- Study finds increase in suicides among Black and Latino Chicagoans

- Howard Stein, acclaimed UChicago philosopher and historian of physics, 1929‒2024

A smarter way to solve the student debt problem

Blanket loan forgiveness less effective than helping those who need it most, research suggests.

Editor’s Note: This piece was written by Constantine Yannelis, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and shared by Chicago Booth Review . The essay is based on testimony Yannelis submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs’ Subcommittee on Economic Policy in April 2021.

Education is the single highest-return investment most Americans will make, so getting our system of higher-education finance right is fundamentally important for U.S. households and the economy.

A key point in the student-loan debate is that the outcomes of borrowers vary widely. Undeniably, a significant number of borrowers are struggling, and are sympathetic candidates for some kind of relief. Student-loan balances have surged over the past decades. According to the New York Fed, last year student loans had the highest delinquency rate of any form of household debt.

Most student borrowers end up as higher earners who do not have difficulties repaying their loans. A college education is, in the vast majority of cases in America, a ticket to success and a high-paying job. Of those who struggle to repay their loans, a large portion attended a relatively small number of institutions—predominantly for-profit colleges.

The core of the problem in the student-loan market lies in a misalignment of incentives for students, schools, and the government. This misalignment comes from the fact that borrowers use government loans to pay tuition to schools. If borrowers end up getting poor jobs, and they default on their loans, schools are not on the hook—taxpayers pay the costs. How do we address this incentive problem? There are many options, but one of the most commonly proposed solutions is universal loan forgiveness.

Various forms of blanket student-loan cancellation have been suggested, but all are extremely regressive, helping higher-income borrowers more than lower-income ones. This is primarily because people who go to college tend to earn more than those who do not go to college, and people who spend more on their college education—such as those who attend medical and law schools—tend to earn more than those who spend less on their college education, such as dropouts or associate’s degree holders.

My own research with Sylvain Catherine of the University of Pennsylvania demonstrates that most of the benefits of a universal-loan-cancellation policy in the United States would accrue to high-income individuals, those in the top 20 percent of the earnings distribution, who would receive six to eight times as much debt relief as individuals in the bottom 20 percent of the earnings distribution. These basic patterns are true for capped forgiveness policies that limit forgiveness up to $10,000 or $50,000 as well.

Another problem with capped student-loan forgiveness is that many struggling borrowers will still face difficulties. A small number of borrowers have large balances and low incomes. Policies forgiving $10,000 or $50,000 in debt will leave their significant problems unaddressed.

While income phaseouts—policies that limit or cut off relief for people above a certain income threshold—make forgiveness less regressive, they are blunt instruments and lead to many individuals who earn large amounts over their lives, such as medical residents and judicial clerks, receiving substantial loan forgiveness.

A fact that is often missed in the policy debate is that we already have a progressive student-loan forgiveness program, and that is income-driven repayment.

If policy makers want to make sure that funds get into the hands of borrowers at the bottom of the income distribution in a progressive way, blanket student-loan forgiveness does not accomplish this goal. Rather, the policy primarily benefits high earners.

While I am convinced from my own research that student-loan forgiveness is regressive, this is also the consensus of economists. The Initiative on Global Markets at Chicago Booth asked a panel of prominent economists to weigh in on this statement: “Having the government issue additional debt to pay off current outstanding loans would be net regressive.” The panel included economists from leading institutions from both the left and the right. The results of the survey were telling. Not a single economist disagreed with the idea that student-loan forgiveness is regressive. This is because the facts are clear—to borrow a phrase commonly used, “The science is settled”—student-loan forgiveness is a regressive policy that mostly benefits upper-income and upper-middle-class individuals.

Another facet of this policy issue is the effect of student-loan forgiveness on racial inequality. One of the most distressing failures of the federal loan program is the high default rates and significant loan burdens on Black borrowers. And student debt has been implicated as a contributor to the Black-white wealth gap. However, the data show that student debt is not a primary driver of the wealth gap, and student-loan forgiveness would make little progress closing the gap but at great expense. The average wealth of a white family is $171,000, while the average wealth of a Black family is $17,150. The racial wealth gap is thus approximately $153,850. According to our paper, which uses data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, and not taking into account the present value of the loan, the average white family holds $6,157 in student debt, while the average Black family holds $10,630. These numbers are unconditional on holding any student debt.

Thus, if all student loans were forgiven, the racial wealth gap would shrink from $153,850 to $149,377. The loan-cancellation policy would cost about $1.7 trillion and only shrink the racial wealth gap by about 3 percent. Surely there are much more effective ways to invest $1.7 trillion if the goal of policy makers is to close the racial wealth gap. For example, targeted, means-tested social-insurance programs are far more likely to benefit Black Americans relative to student-loan forgiveness. For most American families, their largest asset is their home, so increasing property values and homeownership among Black Americans would also likely do much more to close the racial wealth gap. Still, the racial income gap is the primary driver of the wealth gap; wealth is ultimately driven by earnings and workers’ skills—what economists call human capital. In sum, forgiving student-loan debt is a costly way to close a very small portion of the Black-white wealth gap.

How can we provide relief to borrowers who need it, while avoiding making large payments to well-off individuals? There are a number of policy options for legislators to consider. One is to bring back bankruptcy protection for student-loan borrowers.

Another option is expanding the use of income-driven repayment. A fact that is often missed in the policy debate is that we already have a progressive student-loan forgiveness program, and that is income-driven repayment (IDR). IDR plans link payments to income: borrowers typically pay 10–15 percent of their income above 150 percent of the federal poverty line. Depending on the plan, after 20 or 25 years, remaining balances are forgiven. Thus, if borrowers earn below 150 percent of the poverty line, as low-income individuals, they never pay anything, and the debt is forgiven. If borrowers earn low amounts above 150 percent of the poverty line, they make some payments and receive partial forgiveness. If borrowers earn a high income, they fully repay their loan. Put simply, higher-income people pay more and lower-income people pay less. IDR is thus a progressive policy.

IDR plans provide relief to struggling borrowers who face adverse life events or are otherwise unable to earn high incomes. There have been problems with the implementation of IDR plans in the U.S., but these are fixable, including through recent legislation. Many countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia successfully operate IDR programs that are administered through their respective tax authorities.

Beyond providing relief to borrowers, which is important, we could do more to fix technical problems and incentives. We could give servicers more tools to contact borrowers and inform them of repayment options such as IDR, and we could also incentivize servicers to sign more people up for an IDR plan. But while we may be able to make some technical fixes, servicers are not the root of the problem in the student-loan market: a small number of schools and programs account for a large portion of adverse outcomes.

To fix this, policy makers can also directly align the incentives for schools and borrowers. For example, Brazil, which has had similar problems with its student-loan program, recently gave schools skin in the game by requiring them to pay a fee based on dropout and default rates. This helped align the incentives of the schools and the student borrowers. Making revenues go directly to schools from IDR plans, or implementing income-share agreements in which individuals pay an uncapped portion of their income, could also help align the incentives of schools, students, and taxpayers.

Federal student loans are an important part of college financing and intergenerational mobility. The root of our student-loan crisis is a misalignment of incentives. Since the problem has been so slow moving and continuous, I like the analogy of a frog slowly boiling in a pot of water over a flame. Policies such as student-debt cancellation are not extinguishing the flame—they aren’t fixing the incentive problem. All they do is move the frog into a slightly cooler pot of water. And if we don’t fix the core of the problem, even if we forgive $50,000 of debt for current borrowers, balances will continue to grow, and we will be facing a similar crisis in 10 or 20 years.

Recommended stories

Why a 19th-century bank failure still matters

Household spending swings dramatically in reaction to coronavirus

Get more with UChicago News delivered to your inbox.

Related Topics

Latest news, prof. john list named speaker for uchicago’s 2024 convocation ceremony.

Big Brains podcast

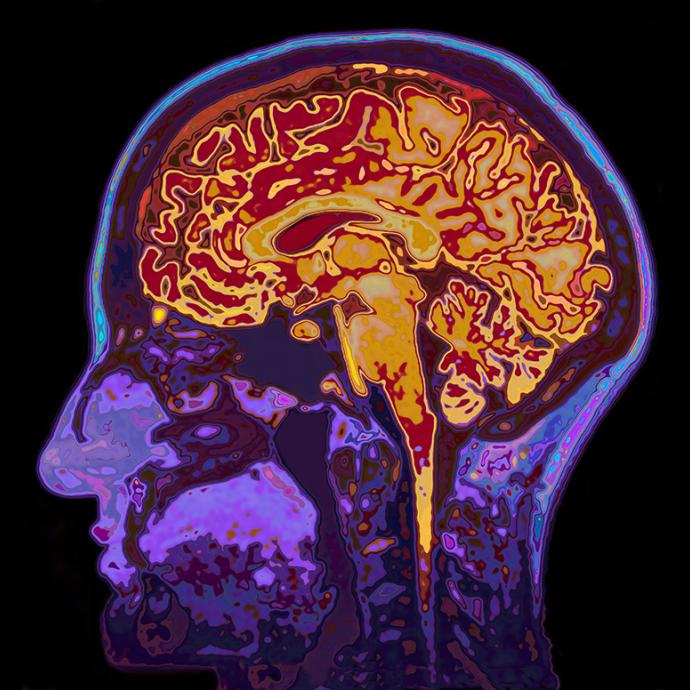

Big Brains podcast: Where has Alzheimer’s research gone wrong?

Biological Sciences Division

Did Spinosaurus hunt its prey deep underwater or from shore? Analysis continues

UChicago Class Visits

Students discover ‘Poetry is Everything’

Where do breakthrough discoveries and ideas come from?

Explore The Day Tomorrow Began

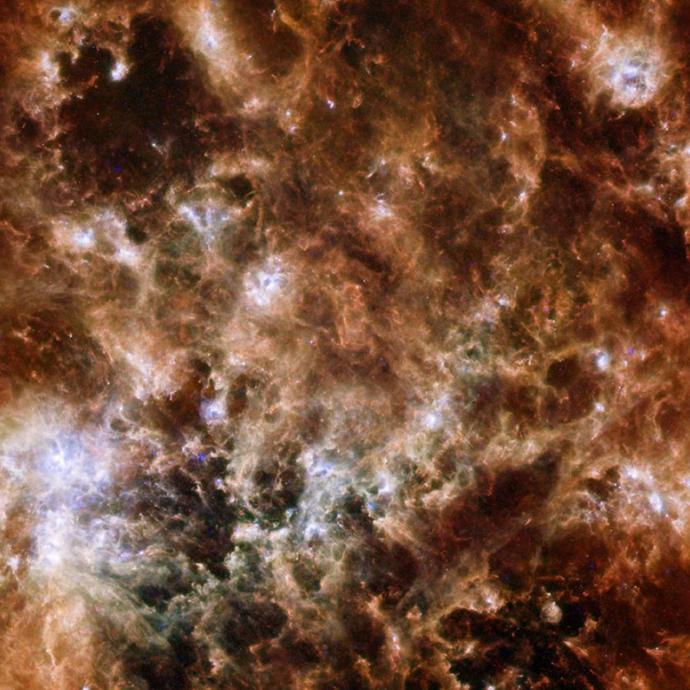

Scientists find one of the most ancient stars that formed in another galaxy

The College

Anna Chlumsky, AB’02, named UChicago’s 2024 Class Day speaker

Around uchicago.

Harris School of Public Policy

UChicago event examines unionization in college athletics, paying student athletes

Alumni Awards

Two Nobel laureates among recipients of UChicago’s 2024 Alumni Awards

Faculty Awards

Profs. John MacAloon and Martha Nussbaum to receive 2024 Norman Maclean Faculty…

Sloan Research Fellowships

Five UChicago scholars awarded prestigious Sloan Fellowships in 2024

UChicago physicists develop a modular robot with liquid and solid properties

Mental health

In event at UChicago, Courtney B. Vance urges Black men to seek mental health care

UChicago Medicine

“I saw an opportunity to leverage the intellectual firepower of a world-class university for advancing cancer research and care.”

It’s in our core

New initiative highlights UChicago’s unique undergraduate experience

- Share full article

Advertisement

The Toll of Student Debt in the U.S.

By Ella Koeze and Karl Russell Aug. 26, 2022

The amount of student debt held in America is roughly equal to the size of the economy of Brazil or Australia. More than 45 million people collectively owe $1.6 trillion, according to U.S. government data.

That figure has skyrocketed over the last half-century as the cost of higher education has continued to rise. The growth in cost has substantially been more than the increase in most other household expenses.

The average cost of college has risen faster than inflation

$22,700 for ’20-’21

academic year

Average cost of public

higher education

adjusted for inflation

Not adjusted

for inflation

’80-’81

’90-’91

’00-’01

’10-’11

’20-’21

for ’20-’21

1980-’81

2000-’01

1975-’76

’85-’86

’95-’96

’05-’06

’15-’16

The rising cost of college has come at a time when students receive less government support, placing a greater burden on students and families to take out loans in order to fund their education.

Funding from states in particular has steadily declined, accounting for roughly 60 percent of spending on higher education just before the pandemic, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute, down from around 70 percent in the 1970s.

States’ and local government’s share of spending on higher education has been declining

Share of higher education expenditures.

Tuition-related charges

Other charges

State appropriations

and other sources

To address the growing crisis, President Biden announced a plan on Wednesday to wipe out significant amounts of student debt for millions of people. It was a step toward making good on a campaign promise to alleviate, as Mr. Biden has said, an unsustainable problem that has saddled generations of Americans.

“The burden is so heavy that even if you graduate,” he said, “you may not have access to the middle-class life that the college degree once provided.”

The typical undergraduate student with loans now finishes school with nearly $25,000 in debt, an Education Department analysis shows.

According to the plan , borrowers will be eligible for $10,000 in debt relief as long as they earn less than $125,000 a year or are in households earning less than $250,000. (Income will be assessed based on what borrowers reported in 2021 or 2020.)

Student debt, however, has a widely disparate impact on different populations.

Black people are increasingly carrying a larger student debt load …

Share of families by race that have an education loan.

Hispanic 14%

… as are millennials, who owe far more than older and younger generations

Total balances of student loans by age.

$500 billion

60 and older

As student debt has grown in recent years, people’s ability to repay it has declined.

When the pandemic brought the global economy to a standstill in 2020, President Trump issued a moratorium on student debt payments and forced interest rates down to zero. Mr. Biden adopted similar policies. The moves helped millions of people lower their loan balances and prevented borrowers unable to pay their loans from defaulting on them.

Nonetheless, there has been a sharp increase in the number of people whose loan balances have stayed the same or have grown since the start of the pandemic.

The pandemic moratorium lowered defaults, but balances still loom

Number of borrowers by loan status at the end of each year.

+7.5 million borrowers

from 2019 to 2021

25 million borrowers

Balance is the same

or higher than one year prior

Balance is lower

–4.7 million

–1.5 million

90 days or more

–1.8 million

Balance is the same or

higher than one year prior

On Wednesday, Mr. Biden announced that the pandemic-era pause on payments would expire at the end of the year. He also reiterated his commitment to providing relief, in particular to lower- and middle-income households . How exactly to do that has been a topic of debate inside the White House and out.

One provision of the program involves an income cap: Debt relief may apply only to individuals or families who earn below a certain amount. The point of that provision, according to the White House, is to make sure no one who earns a high income will benefit from the relief.

An independent analysis from the Wharton School of Business showed that households earning between $51,000 and $82,000 a year would see the most relief — regardless of whether an income cap were applied. This is in part because more people at middle income levels hold student loans.

With or without an income cap, most relief would go to middle-income households

Current plan

If no income cap

$10,000 per person, income

cap of $125,000 individual

or $250,000 household

$10,000 per person,

no income caps

Share of debt relief

In the current plan ,

14% of the debt relief

will go to the lowest

fifth of earners.

Bottom fifth

≤$28,784

≤$50,795

Middle fifth

≤$82,400

≤$141,096

If there were no income cap ,

only 2 percentage points

more relief would go to the

top 10 percent of earners.

If there were no income cap

$10,000 per person, income cap of $125,000

individual or $250,000 household

$10,000 per person, no income caps

30% of debt relief

If there were no income cap , only

2 percentage points more relief would

go to the top 10 percent of earners.

Bottom fifth of earners

Second-lowest fifth

Second-highest fifth

Top fifth of earners

Millions of people stand to benefit from the relief, but Mr. Biden’s announcement kicked off a heated debate about its merits.

On both sides of the political aisle, analysts and officials have worried about the plan’s effects on inflation, in part because wiping away debt could inject money into the economy. (White House economic advisers made the case that by resuming loan payments and including income caps, the plan would have a negligible effect on rising consumer prices.)

Others have argued that while the relief could help many people, it does not address the underlying problems of how expensive college has become. Some economists have even warned the move could encourage colleges and universities to raise prices with the federal government footing the bill.

“I understand that not everything I’m announcing today is going to make everybody happy,” Mr. Biden said on Wednesday. “But I believe my plan is responsible and fair.”

A Guide to Making Better Financial Moves

Making sense of your finances can be complicated. the tips below can help..

Credit card debt is rising, and shopping for a card with a lower interest rate can help you save money. Here are some things to know .

Whether you’re looking to make your home more energy-efficient, install solar panels or buy an electric car, this guide can help you save money and fight climate change .

Starting this year, some of the money in 529 college savings accounts can be used for retirement if it’s not needed for education. Here is how it works .

Are you trying to improve your credit profile? You can now choose to have your on-time rent payments reported to the credit bureaus to enhance your score.

Americans’ credit card debt and late payments are rising, and card interest rates remain high, but many people lack a plan to pay down their debt. Here’s what you can do .

There are few challenges facing students more daunting than paying for college. This guide can help you make sense of it all .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The racial wealth gap is thus approximately $153,850. According to our paper, which uses data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, and not taking into account the present value of the loan, the average white family holds $6,157 in student debt, while the average Black family holds $10,630. These numbers are unconditional on holding any student ...

Solving the Student Debt Crisis. For people across the United States, student loan debt is a growing portion of the household balance sheet. More than 40 million Americans have . outstanding student loan balances. 1. In 2019, the total amount of student debt owed surpassed $1.5 trillion, now the largest source of non-mortgage debt. 2. The ...

By Ella Koeze and Karl Russell Aug. 26, 2022. The amount of student debt held in America is roughly equal to the size of the economy of Brazil or Australia. More than 45 million people ...