- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of essay

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of essay (Entry 2 of 2)

transitive verb

- composition

attempt , try , endeavor , essay , strive mean to make an effort to accomplish an end.

attempt stresses the initiation or beginning of an effort.

try is often close to attempt but may stress effort or experiment made in the hope of testing or proving something.

endeavor heightens the implications of exertion and difficulty.

essay implies difficulty but also suggests tentative trying or experimenting.

strive implies great exertion against great difficulty and specifically suggests persistent effort.

Examples of essay in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'essay.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle French essai , ultimately from Late Latin exagium act of weighing, from Latin ex- + agere to drive — more at agent

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Phrases Containing essay

- essay question

- photo - essay

Articles Related to essay

To 'Essay' or 'Assay'?

You'll know the difference if you give it the old college essay

Dictionary Entries Near essay

Cite this entry.

“Essay.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/essay. Accessed 3 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of essay.

Kids Definition of essay (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on essay

Nglish: Translation of essay for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of essay for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about essay

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 29, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of essay in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I want to finish off this essay before I go to bed .

- His essay was full of spelling errors .

- Have you given that essay in yet ?

- Have you handed in your history essay yet ?

- I'd like to discuss the first point in your essay.

- boilerplate

- composition

- dissertation

- essay question

- peer review

- go after someone

- go all out idiom

- go down swinging/fighting idiom

- go for it idiom

- go for someone

- shoot the works idiom

- smarten (someone/something) up

- smarten up your act idiom

- square the circle idiom

- step on the gas idiom

essay | Intermediate English

Examples of essay, collocations with essay.

These are words often used in combination with essay .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of essay

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

cloak-and-dagger

used to describe an exciting story involving secrets and mystery, often about spies, or something that makes you think of this

Shoots, blooms and blossom: talking about plants

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Verb

- Intermediate Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

Add essay to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

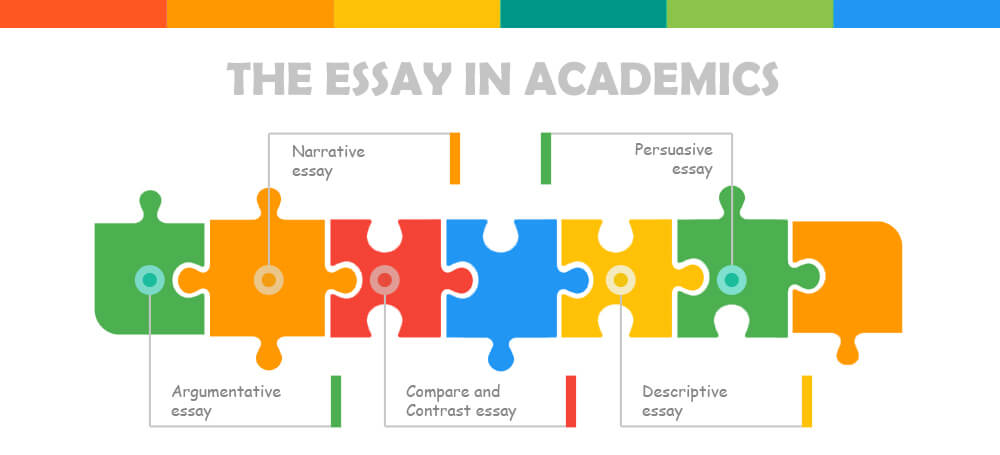

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.

anything resembling such a composition: a picture essay.

an effort to perform or accomplish something; attempt.

Philately . a design for a proposed stamp differing in any way from the design of the stamp as issued.

Obsolete . a tentative effort; trial; assay.

to try; attempt.

to put to the test; make trial of.

Origin of essay

Other words from essay.

- es·say·er, noun

- pre·es·say, verb (used without object)

- un·es·sayed, adjective

- well-es·sayed, adjective

Words that may be confused with essay

- assay , essay

Words Nearby essay

- essay question

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use essay in a sentence

As several of my colleagues commented, the result is good enough that it could pass for an essay written by a first-year undergraduate, and even get a pretty decent grade.

GPT-3 also raises concerns about the future of essay writing in the education system.

This little essay helps focus on self-knowledge in what you’re best at, and how you should prioritize your time.

As Steven Feldstein argues in the opening essay , technonationalism plays a part in the strengthening of other autocracies too.

He’s written a collection of essays on civil engineering life titled Bridginess, and to this day he and Lauren go on “bridge dates,” where they enjoy a meal and admire the view of a nearby span.

I think a certain kind of compelling essay has a piece of that.

The current attack on the Jews,” he wrote in a 1937 essay , “targets not just this people of 15 million but mankind as such.

The impulse to interpret seems to me what makes personal essay writing compelling.

To be honest, I think a lot of good essay writing comes out of that.

Someone recently sent me an old Joan Didion essay on self-respect that appeared in Vogue.

There is more of the uplifted forefinger and the reiterated point than I should have allowed myself in an essay .

Consequently he was able to turn in a clear essay upon the subject, which, upon examination, the king found to be free from error.

It is no part of the present essay to attempt to detail the particulars of a code of social legislation.

But angels and ministers of grace defend us from ministers of religion who essay art criticism!

It is fit that the imagination, which is free to go through all things, should essay such excursions.

British Dictionary definitions for essay

a short literary composition dealing with a subject analytically or speculatively

an attempt or endeavour; effort

a test or trial

to attempt or endeavour; try

to test or try out

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Cultural definitions for essay

A short piece of writing on one subject, usually presenting the author's own views. Michel de Montaigne , Francis Bacon (see also Bacon ), and Ralph Waldo Emerson are celebrated for their essays.

The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write an Essay

I. What is an Essay?

An essay is a form of writing in paragraph form that uses informal language, although it can be written formally. Essays may be written in first-person point of view (I, ours, mine), but third-person (people, he, she) is preferable in most academic essays. Essays do not require research as most academic reports and papers do; however, they should cite any literary works that are used within the paper.

When thinking of essays, we normally think of the five-paragraph essay: Paragraph 1 is the introduction, paragraphs 2-4 are the body covering three main ideas, and paragraph 5 is the conclusion. Sixth and seventh graders may start out with three paragraph essays in order to learn the concepts. However, essays may be longer than five paragraphs. Essays are easier and quicker to read than books, so are a preferred way to express ideas and concepts when bringing them to public attention.

II. Examples of Essays

Many of our most famous Americans have written essays. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson wrote essays about being good citizens and concepts to build the new United States. In the pre-Civil War days of the 1800s, people such as:

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (an author) wrote essays on self-improvement

- Susan B. Anthony wrote on women’s right to vote

- Frederick Douglass wrote on the issue of African Americans’ future in the U.S.

Through each era of American history, well-known figures in areas such as politics, literature, the arts, business, etc., voiced their opinions through short and long essays.

The ultimate persuasive essay that most students learn about and read in social studies is the “Declaration of Independence” by Thomas Jefferson in 1776. Other founding fathers edited and critiqued it, but he drafted the first version. He builds a strong argument by stating his premise (claim) then proceeds to give the evidence in a straightforward manner before coming to his logical conclusion.

III. Types of Essays

A. expository.

Essays written to explore and explain ideas are called expository essays (they expose truths). These will be more formal types of essays usually written in third person, to be more objective. There are many forms, each one having its own organizational pattern. Cause/Effect essays explain the reason (cause) for something that happens after (effect). Definition essays define an idea or concept. Compare/ Contrast essays will look at two items and show how they are similar (compare) and different (contrast).

b. Persuasive

An argumentative paper presents an idea or concept with the intention of attempting to change a reader’s mind or actions . These may be written in second person, using “you” in order to speak to the reader. This is called a persuasive essay. There will be a premise (claim) followed by evidence to show why you should believe the claim.

c. Narrative

Narrative means story, so narrative essays will illustrate and describe an event of some kind to tell a story. Most times, they will be written in first person. The writer will use descriptive terms, and may have paragraphs that tell a beginning, middle, and end in place of the five paragraphs with introduction, body, and conclusion. However, if there is a lesson to be learned, a five-paragraph may be used to ensure the lesson is shown.

d. Descriptive

The goal of a descriptive essay is to vividly describe an event, item, place, memory, etc. This essay may be written in any point of view, depending on what’s being described. There is a lot of freedom of language in descriptive essays, which can include figurative language, as well.

IV. The Importance of Essays

Essays are an important piece of literature that can be used in a variety of situations. They’re a flexible type of writing, which makes them useful in many settings . History can be traced and understood through essays from theorists, leaders, artists of various arts, and regular citizens of countries throughout the world and time. For students, learning to write essays is also important because as they leave school and enter college and/or the work force, it is vital for them to be able to express themselves well.

V. Examples of Essays in Literature

Sir Francis Bacon was a leading philosopher who influenced the colonies in the 1600s. Many of America’s founding fathers also favored his philosophies toward government. Bacon wrote an essay titled “Of Nobility” in 1601 , in which he defines the concept of nobility in relation to people and government. The following is the introduction of his definition essay. Note the use of “we” for his point of view, which includes his readers while still sounding rather formal.

“We will speak of nobility, first as a portion of an estate, then as a condition of particular persons. A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny; as that of the Turks. For nobility attempers sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles. For men’s eyes are upon the business, and not upon the persons; or if upon the persons, it is for the business’ sake, as fittest, and not for flags and pedigree. We see the Switzers last well, notwithstanding their diversity of religion, and of cantons. For utility is their bond, and not respects. The united provinces of the Low Countries, in their government, excel; for where there is an equality, the consultations are more indifferent, and the payments and tributes, more cheerful. A great and potent nobility, addeth majesty to a monarch, but diminisheth power; and putteth life and spirit into the people, but presseth their fortune. It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings. A numerous nobility causeth poverty, and inconvenience in a state; for it is a surcharge of expense; and besides, it being of necessity, that many of the nobility fall, in time, to be weak in fortune, it maketh a kind of disproportion, between honor and means.”

A popular modern day essayist is Barbara Kingsolver. Her book, “Small Wonders,” is full of essays describing her thoughts and experiences both at home and around the world. Her intention with her essays is to make her readers think about various social issues, mainly concerning the environment and how people treat each other. The link below is to an essay in which a child in an Iranian village she visited had disappeared. The boy was found three days later in a bear’s cave, alive and well, protected by a mother bear. She uses a narrative essay to tell her story.

VI. Examples of Essays in Pop Culture

Many rap songs are basically mini essays, expressing outrage and sorrow over social issues today, just as the 1960s had a lot of anti-war and peace songs that told stories and described social problems of that time. Any good song writer will pay attention to current events and express ideas in a creative way.

A well-known essay written in 1997 by Mary Schmich, a columnist with the Chicago Tribune, was made into a popular video on MTV by Baz Luhrmann. Schmich’s thesis is to wear sunscreen, but she adds strong advice with supporting details throughout the body of her essay, reverting to her thesis in the conclusion.

VII. Related Terms

Research paper.

Research papers follow the same basic format of an essay. They have an introductory paragraph, the body, and a conclusion. However, research papers have strict guidelines regarding a title page, header, sub-headers within the paper, citations throughout and in a bibliography page, the size and type of font, and margins. The purpose of a research paper is to explore an area by looking at previous research. Some research papers may include additional studies by the author, which would then be compared to previous research. The point of view is an objective third-person. No opinion is allowed. Any claims must be backed up with research.

VIII. Conclusion

Students dread hearing that they are going to write an essay, but essays are one of the easiest and most relaxed types of writing they will learn. Mastering the essay will make research papers much easier, since they have the same basic structure. Many historical events can be better understood through essays written by people involved in those times. The continuation of essays in today’s times will allow future historians to understand how our new world of technology and information impacted us.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

The Essay: History and Definition

Attempts at Defining Slippery Literary Form

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

"One damned thing after another" is how Aldous Huxley described the essay: "a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything."

As definitions go, Huxley's is no more or less exact than Francis Bacon's "dispersed meditations," Samuel Johnson's "loose sally of the mind" or Edward Hoagland's "greased pig."

Since Montaigne adopted the term "essay" in the 16th century to describe his "attempts" at self-portrayal in prose , this slippery form has resisted any sort of precise, universal definition. But that won't an attempt to define the term in this brief article.

In the broadest sense, the term "essay" can refer to just about any short piece of nonfiction -- an editorial, feature story, critical study, even an excerpt from a book. However, literary definitions of a genre are usually a bit fussier.

One way to start is to draw a distinction between articles , which are read primarily for the information they contain, and essays, in which the pleasure of reading takes precedence over the information in the text . Although handy, this loose division points chiefly to kinds of reading rather than to kinds of texts. So here are some other ways that the essay might be defined.

Standard definitions often stress the loose structure or apparent shapelessness of the essay. Johnson, for example, called the essay "an irregular, indigested piece, not a regular and orderly performance."

True, the writings of several well-known essayists ( William Hazlitt and Ralph Waldo Emerson , for instance, after the fashion of Montaigne) can be recognized by the casual nature of their explorations -- or "ramblings." But that's not to say that anything goes. Each of these essayists follows certain organizing principles of his own.

Oddly enough, critics haven't paid much attention to the principles of design actually employed by successful essayists. These principles are rarely formal patterns of organization , that is, the "modes of exposition" found in many composition textbooks. Instead, they might be described as patterns of thought -- progressions of a mind working out an idea.

Unfortunately, the customary divisions of the essay into opposing types -- formal and informal, impersonal and familiar -- are also troublesome. Consider this suspiciously neat dividing line drawn by Michele Richman:

Post-Montaigne, the essay split into two distinct modalities: One remained informal, personal, intimate, relaxed, conversational and often humorous; the other, dogmatic, impersonal, systematic and expository .

The terms used here to qualify the term "essay" are convenient as a kind of critical shorthand, but they're imprecise at best and potentially contradictory. Informal can describe either the shape or the tone of the work -- or both. Personal refers to the stance of the essayist, conversational to the language of the piece, and expository to its content and aim. When the writings of particular essayists are studied carefully, Richman's "distinct modalities" grow increasingly vague.

But as fuzzy as these terms might be, the qualities of shape and personality, form and voice, are clearly integral to an understanding of the essay as an artful literary kind.

Many of the terms used to characterize the essay -- personal, familiar, intimate, subjective, friendly, conversational -- represent efforts to identify the genre's most powerful organizing force: the rhetorical voice or projected character (or persona ) of the essayist.

In his study of Charles Lamb , Fred Randel observes that the "principal declared allegiance" of the essay is to "the experience of the essayistic voice." Similarly, British author Virginia Woolf has described this textual quality of personality or voice as "the essayist's most proper but most dangerous and delicate tool."

Similarly, at the beginning of "Walden, " Henry David Thoreau reminds the reader that "it is ... always the first person that is speaking." Whether expressed directly or not, there's always an "I" in the essay -- a voice shaping the text and fashioning a role for the reader.

Fictional Qualities

The terms "voice" and "persona" are often used interchangeably to suggest the rhetorical nature of the essayist himself on the page. At times an author may consciously strike a pose or play a role. He can, as E.B. White confirms in his preface to "The Essays," "be any sort of person, according to his mood or his subject matter."

In "What I Think, What I Am," essayist Edward Hoagland points out that "the artful 'I' of an essay can be as chameleon as any narrator in fiction." Similar considerations of voice and persona lead Carl H. Klaus to conclude that the essay is "profoundly fictive":

It seems to convey the sense of human presence that is indisputably related to its author's deepest sense of self, but that is also a complex illusion of that self -- an enactment of it as if it were both in the process of thought and in the process of sharing the outcome of that thought with others.

But to acknowledge the fictional qualities of the essay isn't to deny its special status as nonfiction.

Reader's Role

A basic aspect of the relationship between a writer (or a writer's persona) and a reader (the implied audience ) is the presumption that what the essayist says is literally true. The difference between a short story, say, and an autobiographical essay lies less in the narrative structure or the nature of the material than in the narrator's implied contract with the reader about the kind of truth being offered.

Under the terms of this contract, the essayist presents experience as it actually occurred -- as it occurred, that is, in the version by the essayist. The narrator of an essay, the editor George Dillon says, "attempts to convince the reader that its model of experience of the world is valid."

In other words, the reader of an essay is called on to join in the making of meaning. And it's up to the reader to decide whether to play along. Viewed in this way, the drama of an essay might lie in the conflict between the conceptions of self and world that the reader brings to a text and the conceptions that the essayist tries to arouse.

At Last, a Definition—of Sorts

With these thoughts in mind, the essay might be defined as a short work of nonfiction, often artfully disordered and highly polished, in which an authorial voice invites an implied reader to accept as authentic a certain textual mode of experience.

Sure. But it's still a greased pig.

Sometimes the best way to learn exactly what an essay is -- is to read some great ones. You'll find more than 300 of them in this collection of Classic British and American Essays and Speeches .

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- The Writer's Voice in Literature and Rhetoric

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- What Is Expository Writing?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- What Is Tone In Writing?

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- Writers on Writing: The Art of Paragraphing

- Topical Organization Essay

- What Does "Persona" Mean?

- Mood in Composition and Literature

- Compose a Narrative Essay or Personal Statement

What is Essay? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Essay definition.

An essay (ES-ey) is a nonfiction composition that explores a concept, argument, idea, or opinion from the personal perspective of the writer. Essays are usually a few pages, but they can also be book-length. Unlike other forms of nonfiction writing, like textbooks or biographies, an essay doesn’t inherently require research. Literary essayists are conveying ideas in a more informal way.

The word essay comes from the Late Latin exigere , meaning “ascertain or weigh,” which later became essayer in Old French. The late-15th-century version came to mean “test the quality of.” It’s this latter derivation that French philosopher Michel de Montaigne first used to describe a composition.

History of the Essay

Michel de Montaigne first coined the term essayer to describe Plutarch’s Oeuvres Morales , which is now widely considered to be a collection of essays. Under the new term, Montaigne wrote the first official collection of essays, Essais , in 1580. Montaigne’s goal was to pen his personal ideas in prose . In 1597, a collection of Francis Bacon’s work appeared as the first essay collection written in English. The term essayist was first used by English playwright Ben Jonson in 1609.

Types of Essays

There are many ways to categorize essays. Aldous Huxley, a leading essayist, determined that there are three major groups: personal and autobiographical, objective and factual, and abstract and universal. Within these groups, several other types can exist, including the following:

- Academic Essays : Educators frequently assign essays to encourage students to think deeply about a given subject and to assess the student’s knowledge. As such, an academic essay employs a formal language and tone, and it may include references and a bibliography. It’s objective and factual, and it typically uses a five-paragraph model of an introduction, two or more body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Several other essay types, like descriptive, argumentative, and expository, can fall under the umbrella of an academic essay.

- Analytical Essays : An analytical essay breaks down and interprets something, like an event, piece of literature, or artwork. This type of essay combines abstraction and personal viewpoints. Professional reviews of movies, TV shows, and albums are likely the most common form of analytical essays that people encounter in everyday life.

- Argumentative/Persuasive Essays : In an argumentative or persuasive essay, the essayist offers their opinion on a debatable topic and refutes opposing views. Their goal is to get the reader to agree with them. Argumentative/persuasive essays can be personal, factual, and even both at the same time. They can also be humorous or satirical; Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal is a satirical essay arguing that the best way for Irish people to get out of poverty is to sell their children to rich people as a food source.

- Descriptive Essays : In a descriptive essay, the essayist describes something, someone, or an event in great detail. The essay’s subject can be something concrete, meaning it can be experienced with any or all of the five senses, or abstract, meaning it can’t be interacted with in a physical sense.

- Expository Essay : An expository essay is a factual piece of writing that explains a particular concept or issue. Investigative journalists often write expository essays in their beat, and things like manuals or how-to guides are also written in an expository style.

- Narrative/Personal : In a narrative or personal essay, the essayist tells a story, which is usually a recounting of a personal event. Narrative and personal essays may attempt to support a moral or lesson. People are often most familiar with this category as many writers and celebrities frequently publish essay collections.

Notable Essayists

- James Baldwin, “ Notes of a Native Son ”

- Joan Didion, “ Goodbye To All That ”

- George Orwell, “ Shooting an Elephant ”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, “ Self-Reliance ”

- Virginia Woolf, " Three Guineas "

Examples of Literary Essays

1. Michel De Montaigne, “Of Presumption”

De Montaigne’s essay explores multiple topics, including his reasons for writing essays, his dissatisfaction with contemporary education, and his own victories and failings. As the father of the essay, Montaigne details characteristics of what he thinks an essay should be. His writing has a stream-of-consciousness organization that doesn’t follow a structure, and he expresses the importance of looking inward at oneself, pointing to the essay’s personal nature.

2. Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own”

Woolf’s feminist essay, written from the perspective of an unknown, fictional woman, argues that sexism keeps women from fully realizing their potential. Woolf posits that a woman needs only an income and a room of her own to express her creativity. The fictional persona Woolf uses is meant to teach the reader a greater truth: making both literal and metaphorical space for women in the world is integral to their success and wellbeing.

3. James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel”

In this essay, Baldwin argues that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin doesn’t serve the black community the way his contemporaries thought it did. He points out that it equates “goodness” with how well-assimilated the black characters are in white culture:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, having, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality, much in common with Little Women. Sentimentality […] is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; […] and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.

This essay is both analytical and argumentative. Baldwin analyzes the novel and argues against those who champion it.

Further Resources on Essays

Top Writing Tips offers an in-depth history of the essay.

The Harvard Writing Center offers tips on outlining an essay.

We at SuperSummary have an excellent essay writing resource guide .

Related Terms

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Expository Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Persuasive Essay

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

- Hide all quotations

What does the noun essay mean?

There are 12 meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun essay , nine of which are labelled obsolete. See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

essay has developed meanings and uses in subjects including

Entry status

OED is undergoing a continuous programme of revision to modernize and improve definitions. This entry has not yet been fully revised.

How common is the noun essay ?

How is the noun essay pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the noun essay come from.

Earliest known use

The earliest known use of the noun essay is in the late 1500s.

OED's earliest evidence for essay is from 1597, in the writing of Francis Bacon, lord chancellor, politician, and philosopher.

It is also recorded as a verb from the Middle English period (1150—1500).

essay is a borrowing from French.

Etymons: French essai .

Nearby entries

- esrache, v. 1477

- esraj, n. 1921–

- ESRO, n. 1961–

- ess, n. 1540–

- -ess, suffix¹

- -ess, suffix²

- essamplerie, n. 1393

- essart, n. 1656–

- essart, v. 1675–

- essarting, n. a1821–

- essay, n. 1597–

- essay, v. 1483–

- essayal, n. 1837–

- essayer, n. 1611–

- essayette, n. 1877–

- essayfy, v. 1815–

- essay-hatch, n. 1721–

- essayical, adj. 1860–

- essaying, n. 1861–

- essaying, adj. 1641–

- essayish, adj. 1863–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use

Pronunciation, compounds & derived words, entry history for essay, n..

essay, n. was first published in 1891; not yet revised.

essay, n. was last modified in March 2024.

Revision of the OED is a long-term project. Entries in oed.com which have not been revised may include:

- corrections and revisions to definitions, pronunciation, etymology, headwords, variant spellings, quotations, and dates;

- new senses, phrases, and quotations which have been added in subsequent print and online updates.

Revisions and additions of this kind were last incorporated into essay, n. in March 2024.

Earlier versions of this entry were published in:

OED First Edition (1891)

- Find out more

OED Second Edition (1989)

- View essay, n. in OED Second Edition

Please submit your feedback for essay, n.

Please include your email address if you are happy to be contacted about your feedback. OUP will not use this email address for any other purpose.

Citation details

Factsheet for essay, n., browse entry.

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

That Viral Essay Wasn’t About Age Gaps. It Was About Marrying Rich.

But both tactics are flawed if you want to have any hope of becoming yourself..

Women are wisest, a viral essay in New York magazine’s the Cut argues , to maximize their most valuable cultural assets— youth and beauty—and marry older men when they’re still very young. Doing so, 27-year-old writer Grazie Sophia Christie writes, opens up a life of ease, and gets women off of a male-defined timeline that has our professional and reproductive lives crashing irreconcilably into each other. Sure, she says, there are concessions, like one’s freedom and entire independent identity. But those are small gives in comparison to a life in which a person has no adult responsibilities, including the responsibility to become oneself.

This is all framed as rational, perhaps even feminist advice, a way for women to quit playing by men’s rules and to reject exploitative capitalist demands—a choice the writer argues is the most obviously intelligent one. That other Harvard undergraduates did not busy themselves trying to attract wealthy or soon-to-be-wealthy men seems to flummox her (taking her “high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out” to the Harvard Business School library, “I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence”). But it’s nothing more than a recycling of some of the oldest advice around: For women to mold themselves around more-powerful men, to never grow into independent adults, and to find happiness in a state of perpetual pre-adolescence, submission, and dependence. These are odd choices for an aspiring writer (one wonders what, exactly, a girl who never wants to grow up and has no idea who she is beyond what a man has made her into could possibly have to write about). And it’s bad advice for most human beings, at least if what most human beings seek are meaningful and happy lives.

But this is not an essay about the benefits of younger women marrying older men. It is an essay about the benefits of younger women marrying rich men. Most of the purported upsides—a paid-for apartment, paid-for vacations, lives split between Miami and London—are less about her husband’s age than his wealth. Every 20-year-old in the country could decide to marry a thirtysomething and she wouldn’t suddenly be gifted an eternal vacation.

Which is part of what makes the framing of this as an age-gap essay both strange and revealing. The benefits the writer derives from her relationship come from her partner’s money. But the things she gives up are the result of both their profound financial inequality and her relative youth. Compared to her and her peers, she writes, her husband “struck me instead as so finished, formed.” By contrast, “At 20, I had felt daunted by the project of becoming my ideal self.” The idea of having to take responsibility for her own life was profoundly unappealing, as “adulthood seemed a series of exhausting obligations.” Tying herself to an older man gave her an out, a way to skip the work of becoming an adult by allowing a father-husband to mold her to his desires. “My husband isn’t my partner,” she writes. “He’s my mentor, my lover, and, only in certain contexts, my friend. I’ll never forget it, how he showed me around our first place like he was introducing me to myself: This is the wine you’ll drink, where you’ll keep your clothes, we vacation here, this is the other language we’ll speak, you’ll learn it, and I did.”

These, by the way, are the things she says are benefits of marrying older.

The downsides are many, including a basic inability to express a full range of human emotion (“I live in an apartment whose rent he pays and that constrains the freedom with which I can ever be angry with him”) and an understanding that she owes back, in some other form, what he materially provides (the most revealing line in the essay may be when she claims that “when someone says they feel unappreciated, what they really mean is you’re in debt to them”). It is clear that part of what she has paid in exchange for a paid-for life is a total lack of any sense of self, and a tacit agreement not to pursue one. “If he ever betrayed me and I had to move on, I would survive,” she writes, “but would find in my humor, preferences, the way I make coffee or the bed nothing that he did not teach, change, mold, recompose, stamp with his initials.”

Reading Christie’s essay, I thought of another one: Joan Didion’s on self-respect , in which Didion argues that “character—the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life—is the source from which self-respect springs.” If we lack self-respect, “we are peculiarly in thrall to everyone we see, curiously determined to live out—since our self-image is untenable—their false notions of us.” Self-respect may not make life effortless and easy. But it means that whenever “we eventually lie down alone in that notoriously un- comfortable bed, the one we make ourselves,” at least we can fall asleep.

It can feel catty to publicly criticize another woman’s romantic choices, and doing so inevitably opens one up to accusations of jealousy or pettiness. But the stories we tell about marriage, love, partnership, and gender matter, especially when they’re told in major culture-shaping magazines. And it’s equally as condescending to say that women’s choices are off-limits for critique, especially when those choices are shared as universal advice, and especially when they neatly dovetail with resurgent conservative efforts to make women’s lives smaller and less independent. “Marry rich” is, as labor economist Kathryn Anne Edwards put it in Bloomberg, essentially the Republican plan for mothers. The model of marriage as a hierarchy with a breadwinning man on top and a younger, dependent, submissive woman meeting his needs and those of their children is not exactly a fresh or groundbreaking ideal. It’s a model that kept women trapped and miserable for centuries.

It’s also one that profoundly stunted women’s intellectual and personal growth. In her essay for the Cut, Christie seems to believe that a life of ease will abet a life freed up for creative endeavors, and happiness. But there’s little evidence that having material abundance and little adversity actually makes people happy, let alone more creatively generativ e . Having one’s basic material needs met does seem to be a prerequisite for happiness. But a meaningful life requires some sense of self, an ability to look outward rather than inward, and the intellectual and experiential layers that come with facing hardship and surmounting it.

A good and happy life is not a life in which all is easy. A good and happy life (and here I am borrowing from centuries of philosophers and scholars) is one characterized by the pursuit of meaning and knowledge, by deep connections with and service to other people (and not just to your husband and children), and by the kind of rich self-knowledge and satisfaction that comes from owning one’s choices, taking responsibility for one’s life, and doing the difficult and endless work of growing into a fully-formed person—and then evolving again. Handing everything about one’s life over to an authority figure, from the big decisions to the minute details, may seem like a path to ease for those who cannot stomach the obligations and opportunities of their own freedom. It’s really an intellectual and emotional dead end.

And what kind of man seeks out a marriage like this, in which his only job is to provide, but very much is owed? What kind of man desires, as the writer cast herself, a raw lump of clay to be molded to simply fill in whatever cracks in his life needed filling? And if the transaction is money and guidance in exchange for youth, beauty, and pliability, what happens when the young, beautiful, and pliable party inevitably ages and perhaps feels her backbone begin to harden? What happens if she has children?

The thing about using youth and beauty as a currency is that those assets depreciate pretty rapidly. There is a nearly endless supply of young and beautiful women, with more added each year. There are smaller numbers of wealthy older men, and the pool winnows down even further if one presumes, as Christie does, that many of these men want to date and marry compliant twentysomethings. If youth and beauty are what you’re exchanging for a man’s resources, you’d better make sure there’s something else there—like the basic ability to provide for yourself, or at the very least a sense of self—to back that exchange up.

It is hard to be an adult woman; it’s hard to be an adult, period. And many women in our era of unfinished feminism no doubt find plenty to envy about a life in which they don’t have to work tirelessly to barely make ends meet, don’t have to manage the needs of both children and man-children, could simply be taken care of for once. This may also explain some of the social media fascination with Trad Wives and stay-at-home girlfriends (some of that fascination is also, I suspect, simply a sexual submission fetish , but that’s another column). Fantasies of leisure reflect a real need for it, and American women would be far better off—happier, freer—if time and resources were not so often so constrained, and doled out so inequitably.

But the way out is not actually found in submission, and certainly not in electing to be carried by a man who could choose to drop you at any time. That’s not a life of ease. It’s a life of perpetual insecurity, knowing your spouse believes your value is decreasing by the day while his—an actual dollar figure—rises. A life in which one simply allows another adult to do all the deciding for them is a stunted life, one of profound smallness—even if the vacations are nice.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

I’m an Economist. Don’t Worry. Be Happy.

By Justin Wolfers

Dr. Wolfers is a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan and a host of the “Think Like an Economist” podcast.

I, too, know that flash of resentment when grocery store prices feel like they don’t make sense. I hate the fact that a small treat now feels less like an earned indulgence and more like financial folly. And I’m concerned about my kids now that house prices look like telephone numbers.

But I breathe through it. And I remind myself of the useful perspective that my training as an economist should bring. Sometimes it helps, so I want to share it with you.

Simple economic logic suggests that neither your well-being nor mine depends on the absolute magnitude of the numbers on a price sticker.

To see this, imagine falling asleep and waking up years later to discover that every price tag has an extra zero on it. A gumball costs $2.50 instead of a quarter; the dollar store is the $10 store; and a coffee is $50. The 10-dollar bill in your wallet is now $100; and your bank statement has transformed $800 of savings into $8,000.

Importantly, the price that matters most to you — your hourly pay rate — is also 10 times as high.

What has actually changed in this new world of inflated price tags? The world has a lot more zeros in it, but nothing has really changed.

That’s because the currency that really matters is how many hours you have to work to afford your groceries, a small treat, or a home, and none of these real trade-offs have changed.

This fairy tale — with some poetic license — is roughly the story of our recent inflation. The pandemic-fueled inflationary impulse didn’t add an extra zero to every price tag, but it did something similar.

The same inflationary forces that pushed these prices higher have also pushed wages to be 22 percent higher than on the eve of the pandemic. Official statistics show that the stuff that a typical American buys now costs 20 percent more over the same period. Some prices rose a little more, some a little less, but they all roughly rose in parallel.

It follows that the typical worker can now afford two percent more stuff. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it’s a faster rate of improvement than the average rate of real wage growth over the past few decades .

Of course, these are population averages, and they may not reflect your reality. Some folks really are struggling. But in my experience, many folks feel that they’re falling behind, even when a careful analysis of the numbers suggests they’re not.

That’s because real people — and yes, even professional economists — tend to process the parallel rise of prices and wages in quite different ways. In brief, researchers have found that we tend to internalize the gains due to inflation and externalize the losses. These different processes yield different emotional responses.

Let’s start with higher prices. Sticker shock hurts. Even as someone who closely studies the inflation statistics, I’m still often surprised by higher prices. They feel unfair. They undermine my spending power, and my sense of control and order.

But in reality, higher prices are only the first act of the inflationary play. It’s a play that economists have seen before. In episode after episode, surges in prices have led to — or been preceded by — a proportional surge in wages.

Even though wages tend to rise hand-in-hand with prices, we tell ourselves a different story, in which the wage rises we get have nothing to do with price rises that cause them.

I know that when I ripped open my annual review letter and learned that I had gotten a larger raise than normal, it felt good. For a moment, I believed that my boss had really seen me and finally valued my contribution.

But then my economist brain took over, and slowly it sunk in that my raise wasn’t a reward for hard work, but rather a cost-of-living adjustment.

Internalizing the gain and externalizing the cost of inflation protects you from this deflating realization. But it also distorts your sense of reality.

The reason so many Americans feel that inflation is stealing their purchasing power is that they give themselves unearned credit for the offsetting wage rises that actually restore it.

Those who remember the Great Inflation of the ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s have lived through many cycles of prices rising and wages following. They understand the deal: Inflation makes life more difficult for a bit, but you’re only ever one cost-of-living adjustment away from catching up.

But younger folks — anyone under 60 — had never experienced sustained inflation rates greater than 5 percent in their adult lives. And I think this explains why they’re so angry about today’s inflation.

They haven’t seen this play before, and so they don’t know that when Act I involves higher prices, Act II usually sees wages rising to catch up. If you didn’t know there was an Act II coming, you might leave the theater at intermission, thinking you just saw a show about big corporations exploiting a pandemic to take your slice of the economic pie.

By this telling, decades of low inflation have left several generations ill equipped to deal with its return.

While older Americans understood that the pain of inflation is transitory, younger folks aren’t so sure. Inflation is a lot scarier when you fear that today’s price rises will permanently undermine your ability to make ends meet.

Perhaps this explains why the recent moderate burst of inflation has created seemingly more anxiety than previous inflationary episodes.

More generally, being an economist makes me an optimist. Social media is awash with (false) claims that we’re in a “ silent depression ,” and those who want to make American great again are certain it was once so much better.

But in reality, our economy this year is larger, more productive and will yield higher average incomes than in any prior year on record in American history. And because the United States is the world’s richest major economy, we can now say that we are almost certainly part of the richest large society in its richest year in the history of humanity.

The income of the average American will double approximately every 39 years. And so when my kids are my age, average income will be roughly double what it is today. Far from being fearful for my kids, I’m envious of the extraordinary riches their generation will enjoy.

Psychologists describe anxiety disorders as occurring when the panic you feel is out of proportion to the danger you face. By this definition, we’re in the midst of a macroeconomic anxiety attack.

And so the advice I give as an economist mirrors that I would give were I your therapist: Breathe through that anxiety, and remember that this, too, shall pass.

Justin Wolfers is a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan and a host of the “Think Like an Economist” podcast.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A chronological approach can be useful when your essay is about a series of events. Don’t rule out other approaches, though—even when the chronological approach is the obvious one, you might be able to bring out more with a different structure.

Explore the tabs below to see a general template and a specific example outline from an essay on the invention of the printing press.

- Thesis statement

- Discussion of event/period

- Consequences

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages

- Background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press

- Thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation

- High levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe

- Literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites

- Consequence: this discouraged political and religious change

- Invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg

- Implications of the new technology for book production

- Consequence: Rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible

- Trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention

- Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation

- Consequence: The large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics

- Summarize the history described

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period

Essays with two or more main subjects are often structured around comparing and contrasting . For example, a literary analysis essay might compare two different texts, and an argumentative essay might compare the strengths of different arguments.

There are two main ways of structuring a compare-and-contrast essay: the alternating method, and the block method.

Alternating

In the alternating method, each paragraph compares your subjects in terms of a specific point of comparison. These points of comparison are therefore what defines each paragraph.

The tabs below show a general template for this structure, and a specific example for an essay comparing and contrasting distance learning with traditional classroom learning.

- Synthesis of arguments

- Topical relevance of distance learning in lockdown

- Increasing prevalence of distance learning over the last decade

- Thesis statement: While distance learning has certain advantages, it introduces multiple new accessibility issues that must be addressed for it to be as effective as classroom learning

- Classroom learning: Ease of identifying difficulties and privately discussing them

- Distance learning: Difficulty of noticing and unobtrusively helping

- Classroom learning: Difficulties accessing the classroom (disability, distance travelled from home)

- Distance learning: Difficulties with online work (lack of tech literacy, unreliable connection, distractions)

- Classroom learning: Tends to encourage personal engagement among students and with teacher, more relaxed social environment

- Distance learning: Greater ability to reach out to teacher privately

- Sum up, emphasize that distance learning introduces more difficulties than it solves

- Stress the importance of addressing issues with distance learning as it becomes increasingly common

- Distance learning may prove to be the future, but it still has a long way to go

In the block method, each subject is covered all in one go, potentially across multiple paragraphs. For example, you might write two paragraphs about your first subject and then two about your second subject, making comparisons back to the first.

The tabs again show a general template, followed by another essay on distance learning, this time with the body structured in blocks.

- Point 1 (compare)

- Point 2 (compare)

- Point 3 (compare)

- Point 4 (compare)

- Advantages: Flexibility, accessibility

- Disadvantages: Discomfort, challenges for those with poor internet or tech literacy

- Advantages: Potential for teacher to discuss issues with a student in a separate private call

- Disadvantages: Difficulty of identifying struggling students and aiding them unobtrusively, lack of personal interaction among students

- Advantages: More accessible to those with low tech literacy, equality of all sharing one learning environment

- Disadvantages: Students must live close enough to attend, commutes may vary, classrooms not always accessible for disabled students

- Advantages: Ease of picking up on signs a student is struggling, more personal interaction among students

- Disadvantages: May be harder for students to approach teacher privately in person to raise issues

An essay that concerns a specific problem (practical or theoretical) may be structured according to the problems-methods-solutions approach.

This is just what it sounds like: You define the problem, characterize a method or theory that may solve it, and finally analyze the problem, using this method or theory to arrive at a solution. If the problem is theoretical, the solution might be the analysis you present in the essay itself; otherwise, you might just present a proposed solution.

The tabs below show a template for this structure and an example outline for an essay about the problem of fake news.

- Introduce the problem

- Provide background

- Describe your approach to solving it

- Define the problem precisely

- Describe why it’s important

- Indicate previous approaches to the problem

- Present your new approach, and why it’s better

- Apply the new method or theory to the problem

- Indicate the solution you arrive at by doing so

- Assess (potential or actual) effectiveness of solution

- Describe the implications

- Problem: The growth of “fake news” online

- Prevalence of polarized/conspiracy-focused news sources online

- Thesis statement: Rather than attempting to stamp out online fake news through social media moderation, an effective approach to combating it must work with educational institutions to improve media literacy

- Definition: Deliberate disinformation designed to spread virally online

- Popularization of the term, growth of the phenomenon

- Previous approaches: Labeling and moderation on social media platforms

- Critique: This approach feeds conspiracies; the real solution is to improve media literacy so users can better identify fake news

- Greater emphasis should be placed on media literacy education in schools

- This allows people to assess news sources independently, rather than just being told which ones to trust

- This is a long-term solution but could be highly effective

- It would require significant organization and investment, but would equip people to judge news sources more effectively

- Rather than trying to contain the spread of fake news, we must teach the next generation not to fall for it

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Signposting means guiding the reader through your essay with language that describes or hints at the structure of what follows. It can help you clarify your structure for yourself as well as helping your reader follow your ideas.

The essay overview

In longer essays whose body is split into multiple named sections, the introduction often ends with an overview of the rest of the essay. This gives a brief description of the main idea or argument of each section.

The overview allows the reader to immediately understand what will be covered in the essay and in what order. Though it describes what comes later in the text, it is generally written in the present tense . The following example is from a literary analysis essay on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

Transitions

Transition words and phrases are used throughout all good essays to link together different ideas. They help guide the reader through your text, and an essay that uses them effectively will be much easier to follow.

Various different relationships can be expressed by transition words, as shown in this example.

Because Hitler failed to respond to the British ultimatum, France and the UK declared war on Germany. Although it was an outcome the Allies had hoped to avoid, they were prepared to back up their ultimatum in order to combat the existential threat posed by the Third Reich.