Why education matters for economic development

Harry a. patrinos.

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Why education is the key to development

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Børge Brende

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Infrastructure is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, infrastructure.

Education is a human right. And, like other human rights, it cannot be taken for granted. Across the world, 59 million children and 65 million adolescents are out of school . More than 120 million children do not complete primary education.

Behind these figures there are children and youth being denied not only a right, but opportunities: a fair chance to get a decent job, to escape poverty, to support their families, and to develop their communities. This year, decision-makers will set the priorities for global development for the next 15 years. They should make sure to place education high on the list.

The deadline for the Millennium Development Goals is fast approaching. We have a responsibility to make sure we fulfill the promise we made at the beginning of the millennium: to ensure that boys and girls everywhere complete a full course of primary schooling.

The challenge is daunting. Many of those who remain out of school are the hardest to reach, as they live in countries that are held back by conflict, disaster, and epidemics. And the last push is unlikely to be accompanied by the double-digit economic growth in some developing economies that makes it easier to expand opportunities.

Nevertheless, we can succeed. Over the last 15 years, governments and their partners have shown that political will and concerted efforts can deliver tremendous results – including halving the number of children and adolescents who are out of school. Moreover, most countries are closing in on gender parity at the primary level. Now is the time to redouble our efforts to finish what we started.

But we must not stop with primary education. In today’s knowledge-driven economies, access to quality education and the chances for development are two sides of the same coin. That is why we must also set targets for secondary education, while improving quality and learning outcomes at all levels. That is what the Sustainable Development Goal on education, which world leaders will adopt this year, aims to do.

Addressing the fact that an estimated 250 million children worldwide are not learning the basic skills they need to enter the labor market is more than a moral obligation. It amounts to an investment in sustainable growth and prosperity. For both countries and individuals, there is a direct and indisputable link between access to quality education and economic and social development.

Likewise, ensuring that girls are not kept at home when they reach puberty, but are allowed to complete education on the same footing as their male counterparts, is not just altruism; it is sound economics. Communities and countries that succeed in achieving gender parity in education will reap substantial benefits relating to health, equality, and job creation.

All countries, regardless of their national wealth, stand to gain from more and better education. According to a recent OECD report , providing every child with access to education and the skills needed to participate fully in society would boost GDP by an average 28% per year in lower-income countries and 16% per year in high-income countries for the next 80 years.

Today’s students need “twenty-first-century skills,” like critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, and digital literacy. Learners of all ages need to become familiar with new technologies and cope with rapidly changing workplaces.

According to the International Labour Organization, an additional 280 million jobs will be needed by 2019. It is vital for policymakers to ensure that the right frameworks and incentives are established so that those jobs can be created and filled. Robust education systems – underpinned by qualified, professionally trained, motivated, and well-supported teachers – will be the cornerstone of this effort.

Governments should work with parent and teacher associations, as well as the private sector and civil-society organizations, to find the best and most constructive ways to improve the quality of education. Innovation has to be harnessed, and new partnerships must be forged.

Of course, this will cost money. According to UNESCO, in order to meet our basic education targets by 2030, we must close an external annual financing gap of about $22 billion. But we have the resources necessary to deliver. What is lacking is the political will to make the needed investments.

This is the challenge that inspired Norway to invite world leaders to Oslo for a Summit on Education for Development , where we can develop strategies for mobilizing political support for increasing financing for education. For the first time in history, we are in the unique position to provide education opportunities for all, if only we pull together. We cannot miss this critical opportunity.

To be sure, the responsibility for providing citizens with a quality education rests, first and foremost, with national governments. Aid cannot replace domestic-resource mobilization. But donor countries also have an important role to play, especially in supporting least-developed countries. We must reverse the recent downward trend in development assistance for education, and leverage our assistance to attract investments from various other sources. For our part, we are in the process of doubling Norway’s financial contribution to education for development in the period 2013-2017.

Together, we need to intensify efforts to bring the poorest and hardest to reach children into the education system. Education is a right for everyone. It is a right for girls, just as it is for boys. It is a right for disabled children, just as it is for everyone else. It is a right for the 37 million out-of-school children and youth in countries affected by crises and conflicts. Education is a right regardless of where you are born and where you grow up. It is time to ensure that the right is upheld.

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate . Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter .

Author: Erna Solberg is Prime Minister of Norway. Børge Brende is Norway’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Image: Students attend a class at the Oxford International College in Changzhou. REUTERS/Aly Song.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Growth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Why shifting from prediction to foresight can help us plan for future disruption

Roger Spitz

May 3, 2024

5 ways businesses can help to alleviate poverty

Sreevas Sahasranamam and Vivek Soundararajan

The state of world prosperity: 4 key data points you need to understand

Wolfgang Fengler and Homi Kharas

Money matters: Your guide to financial literacy

Meagan Andrews and Haleh Nazeri

OECD upgrades global economic outlook, and other economics stories to read

Why investing in people is essential to revive growth: Key quotes from leaders at the #SpecialMeeting24

Gayle Markovitz and Kate Whiting

May 2, 2024

2021 Theses Doctoral

Essays in the Economics of Education

Nguyen, Dieu Hoa Thi

Education is at the center of upskilling human capital in developing countries, thereby positively influencing economic growth and development. For decades, many education policies targeted at developing countries have been narrowly focused on improving access to basic education (Barrett et al., 2015). However, access to education does not always translate into educational attainment. Thus, beyond the initial goal of expanding access to education in developing countries, there has been a growing focus on delivering quality education on the development agenda for developing countries in recent years. One popular policy instrument in enhancing education quality has been school choice. Analysis of school choice and the subsequent academic performance outcomes can provide new insight on the economics of education to policymakers, schools, parents and students alike. This dissertation consists of three essays, which focus on understanding the demand for public schools and the returns to school quality in a merit-based competitive school assignment system. In particular, these papers investigate how positive recognition of ability through awards can affect the students’ decision-making process; what the students might gain from attending a more selective school; and how students balance between their preferences for school characteristics and maximizing their chances of admission in a competitive school choice market. Altogether, this dissertation highlights the role of information as well as educational background in explaining differences in school choice decisions and achievement outcomes. In chapter 1, I examine the role of positive recognition on students’ school choice decisions and achievement outcomes in the context of academic competitions. Academic competitions are an essential aspect of education. Given the prevalence and the amount of resources spent organizing them, a natural question that arises is the extent of the impact on winners’ education outcomes when their talent is recognized. I exploit the award structure in Vietnam’s annual regional academic competitions to answer this question. By leveraging the pre-determined share of awards, I apply a regression discontinuity design to assess the effects of receiving a Prize and receiving an Honorable Mention. I find that both types of awards lead to improvements in educational outcomes, and the results are persistent after three years. I also find some evidence of specialization associated with receiving a Prize Award. I hypothesize that long-term effects can be partially explained by school choice: winners are significantly more likely to apply to and consequently enroll in higher-quality schools. There are also prominent differences in educational choices and outcomes along gender lines: female students are more sensitive to award receipts than male students. These findings underscore the positive motivational effects of awards, even among the top performers in a highly competitive schooling market. In chapter 2, I explore the impacts of attending a selective school on students’ educational outcomes. Students in Vietnam are assigned to public high schools based on their performance in a placement exam as well as their ranked choice of schools. Public schools are often oversubscribed, which contributes to exogeneous admission score cutoffs below which students are not considered for admission. By applying a regression discontinuity research design to these admission score cutoffs, I find that students who are marginally admitted to their top-choice public schools are exposed to significantly higher-achieving peers while finding themselves at the bottom of the ability distribution. They experience some improvements in standardized test scores at the end of their high school, but fare worse in school-based achievements and graduation outcomes. These findings highlight the importance of the potential trade-offs between attending more selective schools with better peer quality while receiving a lower ordinal rank in the ability distribution in the assigned school. In addition, the impacts of selective schools on students vary along the lines of the students’ own attitude towards studying as well as their middle school educational background. This substantial heterogeneity collectively highlights the importance of considering the students’ past educational background in interpreting how selective schools might impact students’ outcomes. In chapter 3, I investigate students’ preferences, strategic behaviors and welfare outcomes under a competitive school choice market by conducting a survey on school choice participants in two school districts in Vietnam. The original survey data on school choice participants, coupled with administrative data, afford me the opportunity to understand true preferences and strategies without involving strong assumptions on the students’ beliefs. In order to balance out their own preferences and chance of admission in such a competitive setting, the majority of students exhibit strategic behaviors. However, students from less advanced educational backgrounds tend to have large belief errors and are more likely to make strategic mistakes. Consequently, these students are at a disadvantage, as they find themselves among lower-achieving peers in their new schools. With preference data from the survey, I estimate the students’ preferences for school characteristics and find evidence of heterogeneity in students’ preferences for school characteristics: students from more advanced educational backgrounds value school selectivity and teacher qualification more than their peers. Using these estimates to evaluate students’ welfare under the current assignment mechanism as well as a counterfactual strategy-proof deferred acceptance algorithm, I find that switching to deferred acceptance algorithm can be welfare-improving, particularly for high-performing students. Overall, this paper provides a starting point to directly study the drawbacks of manipulable assignment mechanisms by using survey data and highlight the potential disparity in preferences and application strategies that can further widen the gap in educational mobility.

Geographic Areas

- Education--Economic aspects

- Public schools

- School choice--Econometric models

- School contests

This item is currently under embargo. It will be available starting 2026-05-26.

More About This Work

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

The Role of Education in Development

- First Online: 30 August 2019

Cite this chapter

- Tristan McCowan 6

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education ((PSGHE))

1719 Accesses

1 Citations

Understanding the role of education in development is highly complex, on account of the slippery nature of both concepts, and the multifaceted relationship between them. This chapter provides a conceptual exploration of these relationships, laying the groundwork for the rest of the book. First, it assesses the role of education as a driver of development, including aspects of economic growth, basic needs and political participation. Second, it looks at the constitutive perspective, involving education as national status, human right and human development. Finally, it assesses the ‘other face’ of education and its negative impacts, as well as the specificities of higher education in relation to other levels.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Almond, G., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy five nations . London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Becker, G. S. (1962, October). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70 (Suppl.), 9–49.

Article Google Scholar

Beckett, K. (2011). R. S. Peters and the concept of education. Educational Theory, 61 (3), 239–255.

Bengtsson, S., Barakat, B., & Muttarak, R. (2018). The role of education in enabling the sustainable development agenda . London: Routledge.

Boni, A., Lopez-Fogues, A., & Walker, M. (2016). Higher education and the post 2015 agenda: A contribution from the human development approach. Journal of Global Ethics, 12 (1), 17–28.

Google Scholar

Boni, A., & Walker, M. (2013). Human development and capabilities: Re-imagining the university of the twenty-first century . London: Routledge.

Boni, A., & Walker, M. (2016). Universities and global human development: Theoretical and empirical insights for social change . London: Routledge.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life . New York: Basic Books.

Bush, K., & Saltarelli, D. (2000). The two faces of education in ethnic conflict . Paris: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future (Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bynner, J., Dolton, P., Feinstein, L., Makepiece, G., Malmberg, L., & Woods, L. (2003). Revisiting the benefits of higher education: A report by the Bedford Group for Lifecourse and Statistical Studies, Institute of Education . Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England.

Castells, M. (1994). The university system: Engine of development in the new world economy. In J. Salmi & A. Verspoor (Eds.), Revitalizing higher education (pp. 14–40). Oxford: Pergamon.

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. F., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., et al. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity . Washington, DC: U. S. Office of Education.

Dewey, J. (1966 [1916]). Democracy and education . New York: MacMillan.

Diamond, J. M. (1997). Guns germs and steel: The fate of human societies . New York: W. W. Norton.

Fraser, N. (1998). From redistribution to recognition? Dilemmas of justice in a ‘post-socialist’ age. In A. Philipps (Ed.), Feminism and politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . London: Penguin Books.

Garrod, N., & Macfarlane, B. (2009). Challenging boundaries: Managing the integration of post-secondary education . Abingdon: Routledge.

Giroux, H., & McLaren, P. (1986). Teacher education and the politics of engagement: The case for democratic schooling. Harvard Educational Review, 56 (3), 213–240.

Green, A. (1990). Education and state formation: the rise of education systems in England, France and the USA . London: Macmillan.

Hanushek, E. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 73, 204–212.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2008). The role of cognitive skills in economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 46 (3), 607–668.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom . London: Routledge.

Huntington, S., & Nelson, J. (1976). No easy choice: Political participation in developing countries . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Klees, S. J. (2016). Human capital and rates of return: Brilliant ideas or ideological dead ends? Comparative Education Review, 60 (4), 644–672.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22 (1), 3–42.

Luescher-Mamashela, T. M., Kiiru, S., Mattes, R., Mwollo-ntallima, A., Ng’ethe, N., & Romo, M. (2011). The university in Africa and democratic citizenship: Hothouse or training ground? Wynberg: Centre for Higher Education Transformation.

Mamdani, M. (2018). The African university. London Review of Books, 40 (14), 29–32.

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72, 413–434.

Marginson, S. (2017). Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education, 44 (2), 287–301.

Martin, C. (2018). Political authority, personal autonomy and higher education. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 25 (2), 154–170.

Mazrui, A. A. (1975). The African university as a multinational corporation: Problems of penetration and dependency. Harvard Educational Review, 45, 198.

McCowan, T. (2004). The growth of private higher education in Brazil: Implications for equity and quality. Journal of Education Policy, 19 (4), 453–472.

McCowan, T. (2009). Rethinking citizenship education: A curriculum for participatory democracy . London: Continuum.

McCowan, T. (2013). Education as a human right: Principles for a universal entitlement to learning . London: Bloomsbury.

McCowan, T. (2015). Theories of development. In T. McCowan & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Education and international development: An introduction . London: Bloomsbury.

McCowan, T., Ananga, E., Oanda, I., Sifuna, D., Ongwenyi, Z., Adedeji, S., et al. (2015). Students in the driving seat: Young people’s views on higher education in Africa (Research Report). Manchester: British Council.

McGrath, S. (2010). The role of education in development: An educationalist’s response to some recent work in development economics. Comparative Education, 46, 237–253.

McGrath, S. (2014). The post-2015 debate and the place of education in development thinking. International Journal of Educational Development, 39, 4–11.

McMahon, W. W. (2009). Higher learning, greater good . Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

Milbrath, L., & Goel, M. (1977). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics? (2nd ed.). Chicago: Rand McNally College.

Milton, S. (2019). Syrian higher education during conflict: Survival, protection, and regime security. International Journal of Educational Development, 64, 38–47.

Milton, S., & Barakat, S. (2016). Higher education as the catalyst of recovery in conflict-affected societies. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 14 (3), 403–421.

Mincer, J. (1981). Human capital and economic growth (Working Paper 80). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w0803.pdf .

Newman, J. H. (1947 [1852]). The idea of the university: Defined and illustrated . London: Longmans, Green.

Novelli, M., & Lopez Cardozo, M. (2008). Conflict, education and the global south: New critical directions. International Journal of Educational Development, 28 (4), 473–488.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Oketch, M. O., McCowan, T., & Schendel, R. (2014). The impact of tertiary education on development: A rigorous literature review . London: Department for International Development.

Parsons, S., & Bynner, J. (2002). Basic skills and political and community participation: Findings from a study of adults born in 1958 and 1970 . London: Basic Skills Agency.

Perkin, H. (2007). History of universities. In J. J. F. Forest & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International handbook of higher education (pp. 159–206). Dordrecht: Springer.

Peters, R. S. (1966). Ethics and education . London: George Allen and Unwin.

Pherali, T., & Lewis, A. (2019). Developing global partnerships in higher education for peacebuilding: A strategy for pathways to impact. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00367-7 .

Prakash, M. S., & Esteva, G. (2008). Escaping education: Living as learning in grassroots cultures (2nd ed.). New York: Peter Lang.

Rist, G. (2002). The history of development: From western origins to global faith . London: Zed Books.

Robertson, S. (2016). Piketty, capital and education: A solution to, or problem in, rising social inequalities? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37 (6), 823–835.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. The Journal of Political Economy, 94 (5), 1002–1037.

Sachs, J. D. (2008). Common wealth: Economics . New York: Penguin Press.

Santos, B. de S. (2015). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide . New York: Routledge.

Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review, 51, 1–17.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. (1999a). Development as freedom . New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999b). Democracy as a universal value. Journal of Democracy, 10 (3), 3–17.

Smith, A., & Vaux, T. (2003). Education, conflict and international development . London: DFID.

Stewart, F. (1985). Planning to meet basic needs . London: Macmillan.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2007). Making globalization work . London: Allen Lane.

Streeten, P. (1977). The basic features of a basic needs approach to development. International Development Review, 3, 8–16.

Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2015). Rethinking Knowledge production and circulation in comparative and international education: Southern theory, postcolonial perspectives, and alternative epistemologies. Comparative Education Review , 59 (1), v–viii.

Tilak, J. B. G. (2003). Higher education and development in Asia. Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, 17 (2), 151–173.

Tomaševski, K. (2001). Human rights obligations: Making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. Right to Education Primers No. 3. Gothenburg: Novum Grafiska.

Unterhalter, E. (2003). The capabilities approach and gendered education: An examination of South African complexities. Theory and Research in Education, 1 (1), 7–22.

Willis, P. (1978). Learning to Labour: How working class kids get working class jobs . Aldershot Gower: Saxon House/Teakfield.

Winch, C. (2006). Graduate attributes and changing conceptions of learning. In P. Hager & S. Holland (Eds.), Graduate attributes, learning and employability (pp. 67–89). Dordrecht: Springer.

Wolff, J., & de-Shalit, A. (2013). On fertile functionings: A response to Martha Nussbaum. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 14(1), 161–165.

World Bank. (1999). Knowledge for development. World Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UCL Institute of Education, London, UK

Tristan McCowan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tristan McCowan .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

McCowan, T. (2019). The Role of Education in Development. In: Higher Education for and beyond the Sustainable Development Goals. Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19597-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19597-7_2

Published : 30 August 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-19596-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-19597-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

How popularising higher education affects economic growth and poverty alleviation: empirical evidence from 38 countries

- Jian Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3228-8163 1 na1 ,

- Eryong Xue ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7079-5027 2 na1 ,

- Yukai Wei ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5202-7307 2 &

- Yunshu He ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4814-9835 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 520 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1016 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The popularisation of higher education supports UNESCO’s aim of developing inclusive and equitable quality education to achieve the fourth Sustainable Development Goal. However, the effect of popularising higher education on economic growth and poverty alleviation remains unexplored. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of higher education and adult education within populations (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (gross domestic product; GDP) and the poverty line using panel data from 38 countries. OLS and quantile regression were performed using data for the period 1995–2021 extracted from the OECD and World Bank databases. The results showed that the population segments with higher education had a significantly positive impact on GDP growth. Moreover, an increased proportion of the population with higher education, of working age, was found to be a contributing factor to GDP growth. Popularising higher education also played a positive role during the initial stage of social and economic development. This study also highlighted that popularising higher education play a key role to influence a country’s educational development and scientific and technological innovation drives the deepening of a country’s economy. It suggested that both national and local governments worldwide should pay much attention to the popularisation degree of higher education to greatly improve the innovative ability of talents and scientific and technological innovation in higher education for both the economic growth and poverty alleviation.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

Worldwide divergence of values

Participatory action research

Introduction.

The popularisation of higher education critically contributes to UNESCO’s efforts to realise the fourth Sustainable Development Goal of inclusive and equitable quality education (Ainscow, 2020 ; Bamberger and Kim, 2022 ).Popularisation of higher education expands the scale of higher education and its high growth rate introduces considerable challenges to the management structure of higher education, triggering a series of theoretical and practical concerns relating to the nature and function of higher education (Balestra and Ruiz, 2015 ; Brand, 2021 ). Given that education and social and economic development are mutually reinforcing, the expansion of higher education leads to an ascending spiral of development for individuals and/or economies. By contrast, a lack of education or early withdrawal from education leads to a downward spiral for them (Camilla, 2023 ). This relationship between education and development undergirds the model of poverty alleviation based on the return on education (Decancq, 2017 ). The previous studies emphasise the importance of the return on education as a multidimensional anti-poverty mechanism and thus a key factor in poverty alleviation (Fang et al., 2022 ; Chelli et al., 2022 ; Garritzmann, 2016 ). For example, return on education is the key factor enabling a transition from poverty alleviation through education to poverty alleviation through education (Gillian et al., 2021 ; Gong and Hong, 2021 ). Poverty alleviation is realised through an interlinking of these two processes and the promotion of the latter (Granata, 2022 ; Habibi and Zabardast, 2020 ). The educational resources can meet the needs of the poor mainly through the return on education at the levels of survival and life quality. In addition, the previous studies highlighted that, with a continuous expansion in the scale of higher education, its economic effect gradually appears to become marginal (Hoeller et al., 2014 ). The density of colleges and universities worldwide has increased considerably in recent years, but it is still inadequate to meet increasing demands resulting from the ongoing popularisation of higher education (Jericho, 2016 ). The increase in the number of colleges and universities has a positive effect in promoting economic development but with marginal benefits. (Julian, 2018 ).

Through reviewed the current relevant studies, it is found that there have limited studies that have simultaneously explored the effects of popularising higher education on economic growth and poverty alleviation. The previous research revealed that most studies have focused on the relations between popularisation of higher education and economic growth. However, a few empirical investigations have examined the effect of population segments with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and poverty reduction. Considering the scope and limitations of previous studies, it aimed to address the above research gap by investigating the effect of a population segment with high levels of higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line at a wide scale using panel data from 38 countries. The main research questions addressed in this study are as follows.

Q1: What is the effect of a population segment with higher education on GDP growth?

Q2: What is the effect of adult education on GDP growth?

Q3: What impact does a population segment with higher education have on reducing the proportion of those experiencing poverty?

Q4: What is the relation between an increased level of adult education and the proportion of the population experiencing poverty?

All these questions are relevant to an exploration of the effect of the population segment with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line. This study is divided into several sections: the first section concentrates on examining the effect of popularising higher education on economic growth and the poverty line, the relationship between popularisation of higher education and poverty alleviation, and the relationship between popularisation of higher education and poverty alleviation. In the second section of method, to address this research gap, this study performed OLS and quantile regressions using data extracted from the OECD and World Bank databases for the period 1995–2021. An OLS regression model and a panel quantile model were used to analyse the effect of a population segment with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line within 38 OECD countries. The impact of the proportion of people aged 24–64 years and 25–34 years who had completed higher education in relation to their peers on GDP and the proportion of people living in poverty in 38 OECD countries have been measured and analysed. The results and discussion have been provided at the last.

Literature review

The effect of popularising higher education on economic growth.

The population segment with higher education is regarded as an important contributor to economic growth, generating scientific knowledge and providing labour, which in turn increases human capital and productivity (Jungblut, 2017 ; Kalamova, 2020 ; Liu, 2017 ). As the scale of higher education expands, the emergence of knowledge power as a large-scale global phenomenon reflects the important role of an expanded educated labour force in the advancement of science and technology and the economy. For example, the relationship between higher education and economic development in European Union countries between 1997 and 2016 was analysed. Their findings revealed a statistically significant correlation between expanding higher education and economic growth in the selected countries. The one-way cause-and-effect relationship between education and economic development in these countries suggests that an increase in the proportion of the population enroled in higher education boosts economic performance. In addition, using a survey sample of 35 households, a retrospective study in Brazil, examined the role of educational expansion in reducing income inequality and poverty. Its findings suggest that it would take decades to reduce inequality and poverty in this country and that this outcome could only be achieved through a major expansion of the higher education sector. The growth needed to achieve this outcome would be considerable (Lamichhane et al., 2021 ). This reduction in inequality and poverty could only be achieved if optimistic assumptions about growth, matching job skills and the return on education do not fall short. In brief, education is not a panacea for reducing poverty and inequality. How three major stages of education contributed to the growth in labour productivity in 125 countries during the period 1999–2014 was also explored. They found that human capital is consistent with the educational returns of an average number of years of formal education at the levels of primary, secondary, and higher education. Their analysis showed that higher education had the greatest impact on labour productivity in the economies under study (Ledger et al., 2019 ). In addition, popularising higher education plays an important role in promoting economic growth, as the scale of higher education can guarantee the scale of human resources development by improving the quality of human resources and cultivating and distributing innovative scientific and technological talents. The scale of higher education guarantees the spread of science and technology and the popularisation of scientific and technological achievements (Mathias, 2023 ; Megyesiova and Lieskovska, 2018 ). The expanded scale of higher education worldwide has a spatial spillover effect on economic growth, which is strengthened through international cooperation in the fields of science and technology.

Popularising higher education also plays a direct role in cultivating and transporting scientific and technological talents to promote international scientific and technological cooperation (Mitic, 2018 ; Özdoğan Özbal, 2021 ; OECD, 2022 ; Pinheiro and Pillay, 2016 ). The scale of postgraduate education inhibited the total number of scientific and technological innovation achievements, indicating that there may be a trade-off between ‘quantity expansion’ and ‘quality upgrading’ of scientific and technological innovation achievements. Nevertheless, the positive effect on the number of high-tech innovation outcomes is significant, indicating that the supporting effect of graduate education on scientific and technological innovation is mainly concentrated in the high-tech fields (Pinheiro and Pillay, 2016 ; Rowe, 2019 ; Sahnoun and Abdennadher, 2022 ). The ‘talent increment’ of regional expansion and the ‘resource stock’ of graduate education have a combined promoting effect on high-tech innovation. There are differences in the effect of graduate education supporting high-tech innovation among provinces with different characteristics relating to the development of graduate education. The incremental expansion of high-quality talent is essential for enhancing the efficiency of material capital and stabilising the advantage of resource stocks. Using education statistics from OECD countries, Russia, and several other countries that participate in OECD education research, comparative and correlational analysis methods were applied to analyse how the scale of growth in young people’s participation in higher education is reflected in changes in their employment and economic activity. The results of their analysis showed that the growth in economic activity involving young graduates with a master’s degree exceeded that of college graduates after the 2009 financial crisis, and graduates fared better in the 2020 crisis, which was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The effect of popularisation of higher education on poverty alleviation

Popularisation of higher education is regarded as an essential factor contributing to poverty alleviation (Samo, 2022 ; Adams, 2013 ; Zapp, 2022 ). The higher education’s role in promoting economic growth can only be fully realised through the cultivation of talents suitable for the actual development situation of the country. Countries with food shortages, for example in Africa, also need to procure and train the right agricultural talent. Key drivers of sustainable agricultural production include access to improved technologies, sustainable growth of human, biological and natural resource capital, improvements in institutional performance and a favourable economic policy environment. Higher education graduates with the necessary ‘soft skills and business skills constitute an important pillar. Chakeredza ( 2008 ), who explored the effect of popularising higher education on poverty alleviation, suggested that the number of hungry people in Africa will continue to increase. Higher education in agriculture must be transformed, and efforts must focus on retaining faculty and on reviewing and redesigning institutional management systems, curriculum content and education delivery.

There are many reasons for poverty, with a lack of education being an important one. Insufficient quality education leads to educational poverty. Using PISA data, Agasisti et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the extent of educational poverty in European countries, considering its incidence, breadth, depth and severity. For this study, they adopted an additive multidimensional poverty measure proposed by Alkirew and Foster. Their findings indicated that between 2006 and 2015, the depth and severity of poverty decreased in most of the countries under study. Moreover, the incidence of educational poverty in many European countries was related mainly to student characteristics and school factors. The expansion of higher education has a positive effect on economic development and poverty reduction by improving work skills within the labour force. Increased enrolment in higher education encourages individuals born in families with low education levels to avail of higher education opportunities. Evidently, the expanded scale of higher education in the process of promoting economic growth has enhanced the equity effect of intergenerational social mobility. The expansion of higher education improves total factor productivity, thus promoting economic transformation and advancement globally (Samo, 2022 ; Adams, 2013 ; Zapp, 2022 ). Furthermore, the previous studies have shown that the structure of higher education talent training has a significant impact on economic development. Therefore, government departments need to make constant efforts to improve relevant systems and promote the optimisation and upgrading of the structure of higher education talent training to meet the needs of future economic development.

Theoretical underpinnings

The relationship between education and economic growth is a classic issue in the study of educational economics. For example, in Solow’s view, the growth of per capita output comes from per capita capital stock and technological progress, but capital investment has the problem of diminishing marginal returns, and the long-term sustainable development of the economy depends on technological progress (Solow, 1957 ). The emphasis on technological progress is a very important point in Solow’s growth theory. It was Schultz who systematically analyzed the contribution of education to economic growth. Influenced by the progress of economic growth theory and national accounting methods, Schulz proposed human capital theory in the process of explaining Solow residuals (Schultz, 1961 ). believes that once human capital is included in economic growth, it will solve the paradoxes and puzzles faced in economic growth research. Starting with the difference in income of different types of workers in the labour market, he found that education and health factors are the main reasons for the income difference, and further clarified that the reason for the income difference is the difference in labor productivity (Schultz, 1961 ). Schultz ( 1961 ) believes that human resources include the quantity and quality of labor, and he mainly focuses on the skills and knowledge of people who can improve labor productivity. As for how to measure human capital investment, Schulz believes that the cost of human capital can be measured in the same way as physical capital. Lucas ( 1988 ) focuses on the mechanism of human capital accumulation and why human capital does not show diminishing marginal returns like physical capital. Lucas divides the effect of human capital into internal effect and external effect. Romer ( 1990 ) internalised technological progress, revealed the relationship between human capital and technological progress, and proposed that the stock of human capital determines the economic growth rate, and it is human capital rather than population that determines economic growth. Romer starts with three hypotheses: first, technological progress is central to long-term economic growth; Second, technological progress is formed by people’s response to market incentives, and market incentives determine technological progress. Third, technology is a special kind of product, and once the cost of the initial input is produced, the technology can be reproduced indefinitely at no cost or very low cost.

In other words, higher education is more about improving students’ ability and productivity, thereby increasing students’ income, and promoting economic growth. Higher education mainly affects economic growth through two aspects: one is the same as Schulz’s improvement of individual ability, and the internal effect of human capital, which directly affects the production process (Schultz, 1961 ). Second, Lucas emphasised the external effect of human capital, and the comprehensive effect of human capital on the whole society, which has the characteristics of increasing marginal benefit (Lucas, 1988 ). It emphasises that the human capital invested in technological innovation and the existing knowledge and technology stock of the whole society jointly determine technological innovation.

Research hypotheses and analytical model

In this study, an OLS regression model and a panel quantile model were used to analyse the effect of a population segment with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line within 38 OECD countries. The study’s hypotheses were as follows:

Hypothesis 1: The effect of a population segment with higher education has a positive impact on GDP growth.

Hypothesis 2: Some level of adult education has a positive impact on GDP growth.

Hypothesis 3: A population segment with higher education has a positive impact by reducing the proportion of the population experiencing poverty.

Hypothesis 4: An increase in the level of adult education has a positive impact by reducing the proportion of the population experiencing poverty.

The widely used Mankiw-Romer-Weil model was applied in this study. The overall level of development of higher education and the popularisation of higher education were considered core elements that independently promote economic development and alleviate poverty. The following model was constructed by incorporating the variable of quality higher education into the Solow model:

where Y it refers to the output of i country in t year. The independent variables Qit and P it respectively represent the scale of development and the degree of popularisation of higher education in i country in t year. The following specific model was constructed:

The independent variables were the proportion of people aged 25–64 years with higher education (A) and the proportion of people aged 25–34 years with higher education within the same age group (B). The first variable reflects the population segment that has completed higher education and can work in the corresponding age group. The second reflects the degree of popularisation of higher education. The proportion of those who have completed higher education in relation to their peers is in the normal state, which can reflect the enrolment rate for the previous process of higher education, thus indicating the degree of popularisation of higher education.

The dependent variables were GDP and the poverty line (D). GDP is a measure the overall level of a country’s economic and social development. The poverty line refers to the proportion of people living on less than US$1.25 a day as a percentage of the country’s total population or the proportion of people living in poverty. Thus, it reflects the level of equity in social development. The figure of US$2.15 is used in the World Bank’s index and is based on the purchasing power parity in 2017 (see Table 1 ).

Data sources and selection of variables

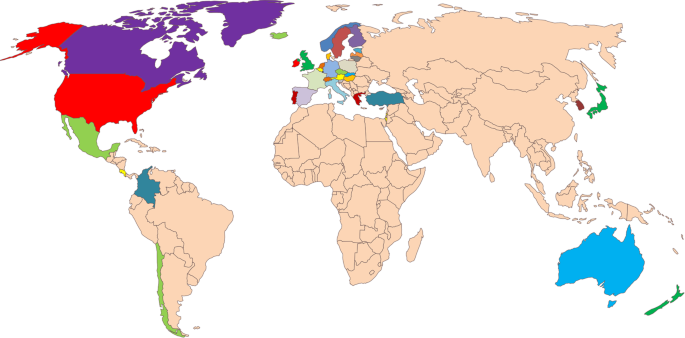

This study measured the impact of the proportion of people aged 24–64 years and 25–34 years who had completed higher education in relation to their peers on GDP and the proportion of people living in poverty in 28 OECD countries. Specifically, this study assessed the impact of the overall level of development of higher education and the degree of its popularisation (the breadth of development of higher education) on GDP (the height of development of economic and social development) and the poverty line (the breadth of development of economic and social development). Data were sourced from the OECD database and the World Bank website covering the period 1995–2021. This study selected 38 OECD countries for this study: the United States, UK, France, Germany, Italy, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Japan, Finland, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, South Korea, Slovakia, Chile, Slovenia, Estonia, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania Colombia and Costa Rica. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 38 OECD countries. Of these countries, 20 were founding members of the OECD when it was established in 1961, while the remaining 18 subsequently became members. After 1994, OECD membership expanded rapidly. Five new members were added within three years. OECD then entered a period of accelerated development, and its operations and advancement reached an optimal stage. Therefore, this study selected data from the OECD database and the World Bank website covering the period 1995–2021 to explore the relationship between higher education and economic and social development in OECD member countries.

It expresses the geographical relations of the Atlantic region and simplifies the latitude and longitude lines and country symbols, highlighting the geographical distribution by highlighting OECD countries in color and other countries in apricot color.

The impact of the population segment with higher education on GDP growth

This study explored the impact of the population segment with higher education on GDP, taking the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education (B) and the proportion of people aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education (A) as the independent variables for the OLS regression. The square value of model R was 0.097, indicating that the two independent variables could explain 9.73% of the change in GDP. The model passed an F test ( F = 46.137, p = 0.000 < 0.05), indicating that at least one of the two independent variables impacted the GDP regression coefficient (C). The following formula was used:

The final analysis revealed that the regression coefficient value of A was 1.553 and the significance level was 0.01 ( t = 7.141, p = 0.000 < 0.01). Therefore, A had a significantly positive influence on C. Accordingly, the proportion of the population aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education, that is, the overall level of development of higher education was found to have a positive impact on GDP. The influence coefficient value was 1.533, indicating that an increase in the proportion of the population with completed higher education led to an increase in GDP.

The regression coefficient value of B was −0.813 at a 0.01 level of significance ( t = −4.300, p = 0.000 < 0.01), indicating that B had a significantly negative influence on C. The proportion of the population aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education, that is, the degree of popularisation of higher education had a negative effect on GDP, and the influence coefficient value was −0.813.

The negative impact on economic and social development caused by an increase in the popularity of higher education and the proportion of young people’s higher education experience may be attributed to the excess capacity of higher education. The development of higher education should be adapted to the national context. An excess of higher education and a lack of investment lead to a rise in the social cost of education and a decline in social outputs, which hinder social and economic development. At the same time, young people aged between 25 and 34 years occupy the position of’ export’ in the education process. With the increasing popularity of higher education, the supply of talents in the labour market generated through the recruitment of former higher education exceeds the demand for graduates with higher education within recruiting organisations. Consequently, issues such as wasted educational resources and knowledge, unemployment, excessive education, excess talents, an imbalance in the structure of higher education, excessive expansion and decreasing compatibility undermine economic operations and hinder GDP growth.

In this study, the variance decomposition and Pearson coefficient based on covariance calculation were analyzed. The variable of the number of 25–34-year-old who have completed higher education as a percentage of their peers explains 50.74% of the change in GDP. The variable of the proportion of 25–64-year-old who have completed higher education explains 49.26% of the change in GDP. The variable of 25- to 34-year-olds who completed higher education as a percentage of their peers explained 45.88% of the change in poverty line. The variable of the proportion of people aged 25–64 who have completed higher education explains 54.12% of the change in GDP (See Table 2 ).

The proportion of people aged 25–34 who have completed higher education in their peers and the proportion of people aged 25–64 who have completed higher education in their peers, GDP and poverty line showed significant correlation coefficients. The correlation between the proportion of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–34 and the proportion of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–64 is 0.931, and shows a significance of 0.01, which indicates that there is a significant positive correlation between the proportion of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–34 and the proportion of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–64. The correlation between the proportion of the number of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–34 and the GDP is 0.209, and the significance is 0.01, which indicates that there is a significant positive correlation between the number of people who have completed higher education at the age of 25–34 and the GDP. The correlation between the number of people who have completed higher education and the poverty line at the age of 25–34 is −0.365, with a significance of 0.01, indicating a significant negative correlation between the number of people who have completed higher education and the poverty line at the age of 25–34 (See Table 2 ).

White test and BP test were used in this study. The test null hypothesis is that the model has no heteroscedasticity. The table above shows that both tests reject the null hypothesis ( p < 0.05), indicating that the model does have heteroscedasticity. When there is a heteroscedasticity problem, Robust and robust standard false regression is used (See Table 3 ).

The impact of a population segment with higher education on the poverty line

This study also explored the impact of a population segment with higher education on the poverty line. Specifically, this study performed an OLS regression in which the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education (B) and the proportion of those aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education (A) were the independent variables. As Table 2 shows, the R squared value was 0.134. This means that variables A and B could explain 13.37% of the change in the poverty line (D). The model passed the F test ( F = 48.771, p = 0.000 < 0.05), which means that at least one variable (A or B) had an impact on the poverty line. The formula for the change in the poverty line was expressed as follows:

The final analysis revealed that the regression coefficient value of the proportion of people aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education (A) was 0.005 but with no significance ( t = 0.428, p = 0.669 > 0.05), indicating that the population segment with higher education did not have an impact on the poverty line.

The regression coefficient value of the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education (B) was −0.048 at a significance level of 0.01 ( t = −4.305, p = 0.000 < 0.01), which means that in relation to their peers, the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education had a significantly negative impact on the proportion of poor people. A higher proportion of people aged 25–34-years who had completed higher education corresponded to a higher penetration rate of higher education and a lower proportion of those living in poverty. This phenomenon can be attributed to OECD’s support for the development of higher education in various countries. When the development of higher education reaches a certain level, the reduction of the proportion of the population segment experiencing poverty will no longer be affected by a simple expansion of the scale of extended higher education and the superposition of the total number of highly educated human resources. It will be influenced more by the reasonable distribution of educational resources and educational equity within higher education and its popularisation, that is, the increase in the proportion of the school-aged population aged 25–34 years based on the increase of the previous enrolment rate (see Table 4 ).

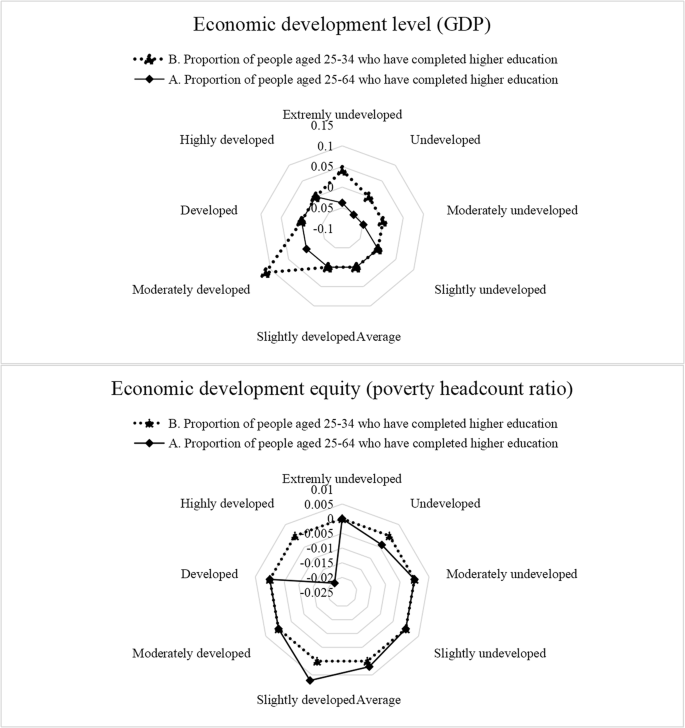

The effect of adult education on GDP growth

For quantile regression analysis, a total of nine models (with decimal points ranging from 0.10 to 0.90 and at intervals of 0.10) were estimated in this analysis, which aimed to explore the impact of the independent variables A and B on the dependent variable, GDP (C). When the quantile value was between 0.1 and 0.3, the proportion of the population aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education (A) had no significant positive impact on GDP growth, indicating that the development of higher education did not significantly affect economic and social development in poorer OECD countries. When the quantile value was between 0.4 and 0.6, the level of development of higher education had a significantly negative impact on economic and social development. Thus, for a country that had developed over a period, the advancement of higher education required multiple inputs, such as capital, material, and human resources.

During the early stage of the development of higher education, such inputs may, however, have a negative and weakening impact on social and economic development. The added cost of education and the lag between the output of educational achievements and the input of talents puts increased pressure on economic and social development during a certain period. When the quantile value was 0.7 or higher, the improvement of the overall level of higher education had a significantly positive impact on GDP growth, indicating the realisation of the talent training outcomes of higher education. Teaching and research outcomes were thus transformed into socially productive resources and power, with talents with higher education contributing to economic and social development.

When the quantile value was 0.1, the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education in relation to their peers (variable B), indicating the popularisation of higher education, had no significant impact on GDP growth. Thus, in extremely backward countries, the popularisation of higher education had little effect on economic and social development. When the quantile value ranged between 0.2 and 0.6, the popularisation of higher education had a significantly positive effect on GDP growth, indicating its contribution to economic growth.

When the quantile value was 0.7, the influence of variable B on variable C was no longer significant, indicating that social development would soon face the problem of overcapacity in higher education. When it exceeded 0.7, the ratio of eligible people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education in relation to their peers had a significantly negative impact on GDP growth, revealing that with the development of the economy, society and education, higher education had become overexpanded. Thus, the cost of investing in education exceeded the social benefits, leading to overcapacity whereby the supply of higher education talents exceeded the demand. This situation led to wasted educational resources and excessive competition of talents, hindering economic growth (See Table 5 ).

The increased level of adult education and the proportion of the population experiencing poverty

Using the same model, this study explored the influence of the independent variables, A and B, on the poverty line (dependent variable D). The proportion of the population aged 25–64 years who had completed higher education (independent variable A) had no significant influence on the proportion of the population living in poverty, indicating that popularisation of education and economic and social development have been achieved to a certain extent in OECD countries, and improvements targeting the population experiencing poverty could no longer be achieved simply by increasing the volume and quantity of higher education. When the quantile value was 0.1, the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who had completed higher education in relation to their peers (independent variable B) had no significant effect on the proportion of the population experiencing poverty (dependent variable D). Therefore, the strategy of increasing higher education enrolment and the ratio of the eligible population through the fair allocation of educational resources, and thus the popularisation of education, would not be effective for a small population segment experiencing poverty. In other words, the population segment experiencing poverty in highly developed countries is less receptive to the popularisation of higher education. When the quantile value was 0.2, the independent variable, B, had a significantly positive impact on the dependent variable D, that is, an increase in the popularity of higher education led to an increase in the population segment experiencing poverty. This phenomenon can be interpreted as reflecting the inherent disadvantages of the welfare state in the field of education. A rise in the number of eligible young people aged 25–34 years who have completed higher education reflects the development trend of higher education towards fairness and popularisation following the redistribution of higher education resources.

The fair distribution of higher education resources leads to a lack of competition in the areas of teaching and career development. To a certain extent, reducing students’ willingness and enthusiasm to work may lead to poverty caused by the failure to achieve teaching results. When the quantile value was between 0.3 and 0.4, the independent variable, B, had no significant influence on the dependent variable D. In relatively poor countries, the popularisation of higher education contributes little to reducing the degree of poverty, so it may be necessary to explore ways of alleviating poverty from the perspective of improving the overall level and expanding the scale of basic higher education. When the quantile value was 0.5 or above, the independent variable B had a significantly negative impact on the dependent variable D, indicating that for countries with a relatively high proportion of their population experiencing poverty, the following strategy would be more effective.

Considering the quantile data, this study deemed that the degree of sensitivity of countries at different stages of economic development to the level of development and popularisation of higher education could be more intuitively evaluated using a radar map (see Fig. 2 ). Countries with sub-points 0.1–0.9 were defined along a spectrum as extremely backward, backward, moderately backward, slightly backward, moderate, preliminarily developed, moderately developed, developed, and highly developed. From the perspective of economic development, increasing the proportion of young people who complete higher education and popularising higher education had an obvious positive effect in backward and medium-developed countries, whereas the effect in highly developed countries was not obvious. Overall, the sensitivity of OECD countries to the high level of education penetration was found to be higher than the level of development of higher education. From the perspective of equitable economic development, the overall level of development of higher education had no significant impact on the poverty link in OECD countries, whereas OECD countries with differing economic development backgrounds and at varying stages of development evidenced relatively significant and stable sensitivity to the proportion of young and middle-aged people who completed higher education and the popularisation of higher education.

The dashed line represents the proportion of people aged 25–34 years who have completed higher education. The solid line represents the proportion of people aged 25–64 years who have completed higher education, the impact of the overall level of higher education.

Our findings indicated that population segments with higher education had a significantly positive impact on GDP growth in 38 OECD countries. An increase in the proportion of the population segment of working age who completed higher education was found to contribute to GDP growth. Moreover, an improvement in the popularity of higher education played a positive role during the initial stage of economic and social development.

At the same time, oversupply and overcapacity may result from a continuous improvement of higher education. A very large number of young people who have completed higher education can lead to excessive competition and wasted academic qualifications (Mathias, 2023 ; Megyesiova and Lieskovska, 2018 ). In turn, higher education knowledge unemployment, overinvestment, a structural imbalance, disorderly expansion and wasted resources can occur, which have detrimental impacts on economic operations.

Some studies have shown that strengthening the quality of higher education helps to improve cognitive abilities within the labour force, thereby enhancing the growth of the knowledge economy (Ainscow, 2020 ; Bamberger and Kim, 2022 ). Other studies have reported regional heterogeneity relating to the marginal effect of improving the quality of higher education on economic growth. Some scholars have analysed the influence of the quality of higher education on economic development from the perspective of human capital investment theory. Their findings indicate that the quality of higher education determines the composition and growth trend of social human capital. Because of differences in the degrees of development of different economies, the quality of higher education has a phased influence on economic growth (Balestra and Ruiz, 2015 ; Brand, 2021 ). Case studies of African developing countries by international scholars have revealed that quality factors are key to realising the economic development function of higher education. From the perspectives of both efficient financial investments by states in education poverty alleviation and the effects of economic, time and emotional investments of poor families and individuals in education poverty alleviation, it is necessary to take the return on education into consideration. Moreover, it is important to respond to reasonable concerns regarding the return on education for poor people and to strengthen their cognitive capacities to rationalise as well as their expectations regarding returns on education (Li et al., 2023 ). In this way, the intention to participate and behaviour of anti-poverty education will be generated, and the strategic upgrading of poverty alleviation combined with the promotion of aspirations and cognitive capacities will be emphasised.

Implications

Our use of panel data from 38 countries to deepen understanding of the effect of popularising higher education on economic growth and poverty reduction also has practical implications. The economic, social, and higher education undertakings in OECD countries evidence a certain level of development. The population segment with higher education has no significant impact on reducing the proportion of the population segment experiencing poverty. Simply increasing the proportion of people who complete higher education and expanding the scale of higher education will not effectively reduce poverty (Li and Xue, 2021 ). Providing more educational opportunities to poor people through the slanting of educational resources can help to reduce the proportion of poor people (Ainscow, 2020 ; Bamberger and Kim, 2022 ). For example, popularising higher education plays a key role to influence a country’s development level and scientific and technological innovation drives the deepening of a country’s economy (Bamberger and Kim, 2022 ). Technological progress is the core of economic growth, scientific and technological innovation brings technological change and development in all aspects, human capital promotes economic growth, and higher education trains talents and improves the capital attribute of human (Camilla, 2023 ). For endogenous economic growth theory, the economy does not rely on external forces to achieve sustained growth, and endogenous technological progress determines sustained economic growth. Popularising higher education worldwide brings the accumulation of human capital, improves the quality of workers, and scientific and technological innovation makes technological progress and high-quality economic development, practically. Human capital accumulation is also the process of continuous input of labour force, which covers the accumulation of human capital by labour force factors in formal education, training, and other learning processes. From the perspective of human capital, popularising higher education is the most direct and efficient way to promote the accumulation of human capital and improve the quality of labour force (Balestra and Ruiz, 2015 ; Brand, 2021 ). The popularisation degree of higher education is one of the important indicators to measure the development level of a country’s economic, and it is also the common trend of the development of higher education in all countries after World War II. In this transitional era, how to continue the achievements of higher education in the popular era and solve the existing problems as soon as possible is the heavy responsibility of our times. Therefore, at the initial stage of popularisation of higher education, it is necessary to re-examine the process of higher education popularisation globally and explore the internal logics between the popularisation of higher education and Sustainable Development Goal of inclusive and equitable quality education (Ainscow, 2020 ; Bamberger and Kim, 2022 ).

For policy suggestions, this study suggests that both national and local governments worldwide should pay much attention to the popularisation degree of higher education to greatly improve the innovative ability of talents and scientific and technological innovation in higher education. For example, they could promote scientific and technological innovation in an organised manner to serve national and regional economic and social development. Faced with the current situation in which global higher education has entered a stage of popularisation and new challenges and problems in serving regional economic and social development, national governments should continue to optimise the distribution and structure of higher education resources to support different regions, focusing on the major strategy of enhancing national competitiveness, serving economic and social development, and promoting common prosperity.

Contributions

This study novelty contributes on examining how popularising higher education affects economic growth and poverty alleviation, conceptually, methodologically, and practically. For instance, this study focuses on epitomising the conceptual and analytical model to explore the effects of higher education and adult education within populations (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (gross domestic product; GDP) and the poverty line. In addition, this study novelty combines both Mankiw-Romer-Weil model Solow model to investigate the effects of higher education and adult education within populations on economic growth and the poverty through OLS regression model and quantile model. For the practical aspect, this study practically uncovers the implicit significance of the popularisation of higher education for advocating UNESCO’s aim of developing inclusive and equitable quality education to achieve the fourth Sustainable Development Goal.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. Data could have been collected from a larger sample of OECD countries to explore the effect of population segments with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line. In addition, a qualitative component could be included in future studies to uncover the cultural and historical contexts of the effect of popularising higher education on economic growth and poverty reduction at the local level. Future studies should also investigate the causal relationship between the popularisation of higher education and economic growth. Additional empirical data and advanced research methods can be used to enable a shift from correlation to causality.

In conclusion, this study examined the effect of the population segment with higher education and adult education (popularisation of higher education) on economic growth (GDP) and the poverty line using panel data from 38 countries. The population segment with higher education was found to have a significant positive impact on promoting GDP growth. An increase in the proportion of the working-age population segment that had completed higher education was evidently conducive to GDP growth. Popularisation of higher education was also found to play a positive role in the initial stage of economic and social development.

Data availability