Social Groups: Definition, Types, Importance, Examples

Definition : A social group refers to two or more individuals who share a common social identification, and who perceive themselves to be members of the same social category Hence, the shared perception or understanding that the individual feels as though they belong to a group is instrumental in defining a social group. It is this shared perception that distinguishes social groups from aggregates, this shared perception is referred to as social identification . An aggregate is a group of people who are at the same place at the same time, for example, a number of individuals waiting together at a bus stop may share a common identification, but do not perceive themselves as belonging to a group, hence a collection of individuals waiting at a bus stop are an aggregate and not a social group. Another collection of individuals that needs to be distinguished from social groups are categories, categories consist of sets of people who share similar characteristics across time and space. A similar characteristic can be race or gender, again the feeling of belonging amongst the individuals involved is what distinguished individuals in a social group and individuals in a category.

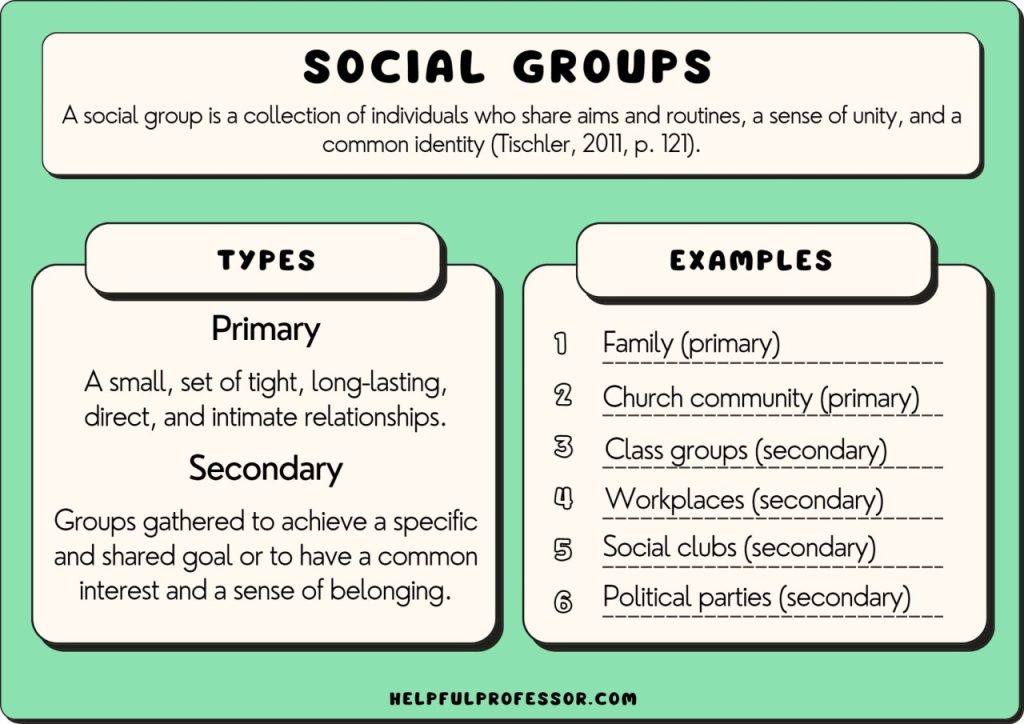

Types of Social Groups

Social groups are of two kinds- primary and secondary groups . The former is small and tightly knit, bound by a very strong sense of belonging, family is a typical example of this kind of social group. In this type of group, the common interest shared amongst the individuals is the emotional attachment to the group in and of itself. Conversely, secondary groups are large impersonal groups, whose members are bound primarily by a shared goal or activity as opposed to emotional ties. For this reason, individuals typically join secondary groups later in life. Employees at a company would constitute as a secondary group. As individuals within a secondary group grow closer they might form a primary group, wherein the individuals are no longer goal-oriented but are instead a group based on emotional connection.

Lastly, reference groups refer to a group to which an individual or another group is compared. Sociologists call any group that individuals use as a standard for evaluating themselves and their own behaviour a reference group. The behaviours of individuals in groups are usually considered aspirational and therefore are grounds for comparison. From the existence of multiple groups, one can also make the distinction between in-groups and out-groups. This distinction is entirely relative to the individuals, hence reference groups are typically out-groups ie. groups that an individual is not a part of, though an individual may aspire to be a part of the reference group.

The acknowledgment of in-groups and out-groups is relevant to an individual’s perception and thus behaviour. Individuals are likely to experience a preference or affinity towards members of their groups,, this is referred to as in-group bias. This bias may result in groupthink, wherein a group believes that there is only one possible solution or mindset which will lead to a consensus. These poor decisions are not the result of individual incompetence when it comes to decision making but instead but instead due to the social rules and norms that exist in the group, such as the nature of leadership and the nature of homogeneity.

A byproduct of in-group bias is intergroup aggression- experience feelings of contempt and a desire to compete to the members of out-groups. This desire to ‘harm’ members of the out-group is a result of dehumanization wherein the members of the out-group are less they deserve the humane treatment. It is a combination of intergroup aggression and groupthink which often results in harmful prejudice. The dehumanization of out-groups is often used as a political agenda. A notable example from history is the way that the Jewish community (out group) were dehumanized by Nazis (in group), through means such as stereotyping. Hence, prejudice can be a result of extreme intergroup aggression.

Group Behaviour and Social Roles

Within a social group individuals typically display group behaviour, which is seen through the expression of cohesive social relationships. This group behaviour is likely the result of social or psychological interdependence for the satisfaction of needs, attainment of goals or consensual validation of attitudes or values. Hence, group behaviour which is expressed through cooperative social interaction hinges on interdependence. It is this group behaviour that yields the development of an organized role relationship. Social roles are the part people play as members of a social group. With each social role you adopt, your behaviour changes to fit the expectations both you and others have of that role. In addition to social roles, groups also create social norms- these are the unwritten rules of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours that are considered acceptable in a particular social group. The ability to develop roles and norms which are guided by a common interest is referred to as social cohesion. The behaviour attached to the norms and roles fulfilled by individuals within a certain social group is usually not the same behaviours exhibited when that individual is not with their group ie. social interaction theory. For example, in a family (which is a social group) a mother is likely not to behave in the way she would in another social group such as at her place of work.

All social groups have an individual who fulfils the leadership role, a leader is an individual who influences the other members of a group, their position may or may not be explicitly stated.

Leadership function considers the intention by which the leader behaves on, either instrumental or expressive. An instrumental leader is focused on a group’s goals, giving orders and making plans in order to achieve those goals. An expressive leader, by contrast, is looking to increase harmony and minimize conflict within the group. In addition to leadership function, there are also three different leadership styles. Democratic leaders focus on encouraging group participation as obsessed with acting and speaking on behalf of the group. Secondly, laissez-faire leaders take a more hands-off approach by encouraging self-management. Lastly, authoritarian leaders are the most controlling by issuing roles to members and setting rules, usually, without input from the rest of the group.

In secondary groups, every member is has a definitive role, however as secondary groups are goal oriented the roles differ from group to group. It is also not uncommon within secondary groups for roles to change. For example, in a school research assignment, initially individuals may fulful roles such as writer, illustrator, researcher, etc in order to write a report. But in the second half which is focused on presenting the repot, members may take up new roles such as presenter, debator, etc, as the goals of the group shifts.

Norms can be simply defined as the expectations of behaviour from group members. These norms which dictate group behaviour can largely be attributed to the groups’ goals and leadership styles. However norms need not only be the result of in-group occurrences, reference groups oftentimes dictate what is and what is not acceptable behaviour. Typically there are norms that apply to the group as a whole known as general norms . Additionally, there are also norms that are role-specific. For example consider a family (ie. a primary group) everyone in the family attends dinner at 8 pm, while the father cooks dinner and the child sets the table. Everyone attending dinner is a general norm while the act of cooking dinner and setting the table are role-specific to the father and child, respectively.

The Importance of Social Groups

Social groups, primary groups, such as family, close friends, and religious groups, in particular, are instrumental an individuals socialization process. Socialization is the process by which individuals learn how to behave in accordance with the group and ultimately societies norms and values. According to Cooley self-identity is developed through social interaction. Hence, from an identity perspective, primary social groups offer the means through which an individual can create and mold their identity. The development of identity is most rapid and crucial in childhood, hence the importance of family and friends, but the development of identity does continue throughout one’s life. Additionally, from a psychological perspective, primary groups are able to offer comfort and support. Secondary groups, such as members of a group assignment, tend to have less of an influence on identity, in part because individuals within these types of groups are older and hence have a self-identity as well as are familiar with the socialization process.

Natasha Dmello

Natasha D'Mello is currently a communications and sociology student at Flame University. Her interests include graphic design, poetry and media analysis.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.1 Social Groups

Learning objectives.

- Describe how a social group differs from a social category or social aggregate.

- Distinguish a primary group from a secondary group.

- Define a reference group and provide one example of such a group.

- Explain the importance of networks in a modern society.

A social group consists of two or more people who regularly interact on the basis of mutual expectations and who share a common identity. It is easy to see from this definition that we all belong to many types of social groups: our families, our different friendship groups, the sociology class and other courses we attend, our workplaces, the clubs and organizations to which we belong, and so forth. Except in rare cases, it is difficult to imagine any of us living totally alone. Even people who live by themselves still interact with family members, coworkers, and friends and to this extent still have several group memberships.

It is important here to distinguish social groups from two related concepts: social categories and social aggregates. A social category is a collection of individuals who have at least one attribute in common but otherwise do not necessarily interact. Women is an example of a social category. All women have at least one thing in common, their biological sex, even though they do not interact. Asian Americans is another example of a social category, as all Asian Americans have two things in common, their ethnic background and their residence in the United States, even if they do not interact or share any other similarities. As these examples suggest, gender, race, and ethnicity are the basis for several social categories. Other common social categories are based on our religious preference, geographical residence, and social class.

Falling between a social category and a social group is the social aggregate , which is a collection of people who are in the same place at the same time but who otherwise do not necessarily interact, except in the most superficial of ways, or have anything else in common. The crowd at a sporting event and the audience at a movie or play are common examples of social aggregates. These collections of people are not a social category, because the people are together physically, and they are also not a group, because they do not really interact and do not have a common identity unrelated to being in the crowd or audience at that moment.

A social aggregate is a collection of people who are in the same place at the same time but who otherwise have nothing else in common. A crowd at a sporting event and the audience at a movie or play are examples of social aggregates.

Eliud Gil Samaniego – Art – Aguilas de Mexicali – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

With these distinctions laid out, let’s return to our study of groups by looking at the different types of groups sociologists have delineated.

Primary and Secondary Groups

A common distinction is made between primary groups and secondary groups. A primary group is usually small, is characterized by extensive interaction and strong emotional ties, and endures over time. Members of such groups care a lot about each other and identify strongly with the group. Indeed, their membership in a primary group gives them much of their social identity. Charles Horton Cooley, whose looking-glass-self concept was discussed in Chapter 5 “Social Structure and Social Interaction” , called these groups primary , because they are the first groups we belong to and because they are so important for social life. The family is the primary group that comes most readily to mind, but small peer friendship groups, whether they are your high school friends, an urban street gang, or middle-aged adults who get together regularly, are also primary groups.

Although a primary group is usually small, somewhat larger groups can also act much like primary groups. Here athletic teams, fraternities, and sororities come to mind. Although these groups are larger than the typical family or small circle of friends, the emotional bonds their members form are often quite intense. In some workplaces, coworkers can get to know each other very well and become a friendship group in which the members discuss personal concerns and interact outside the workplace. To the extent this happens, small groups of coworkers can become primary groups (Elsesser & Peplau, 2006; Marks, 1994).

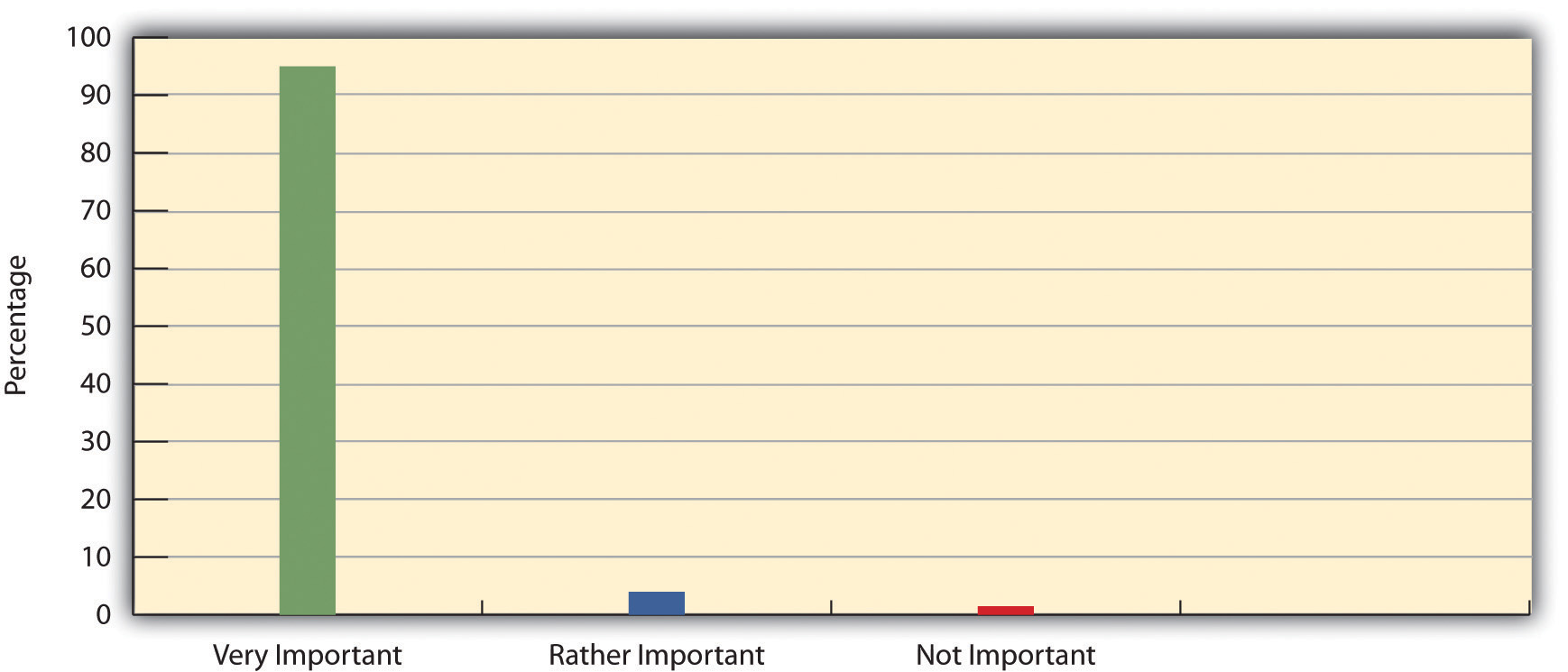

Our primary groups play significant roles in so much that we do. Survey evidence bears this out for the family. Figure 6.1 “Percentage of Americans Who Say Their Family Is Very Important, Quite Important, Not Too Important, or Not at All Important in Their Lives” shows that an overwhelming majority of Americans say their family is “very important” in their lives. Would you say the same for your family?

Figure 6.1 Percentage of Americans Who Say Their Family Is Very Important, Quite Important, Not Too Important, or Not at All Important in Their Lives

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 2002.

Ideally, our primary groups give us emotional warmth and comfort in good times and bad and provide us an identity and a strong sense of loyalty and belonging. Our primary group memberships are thus important for such things as our happiness and mental health. Much research, for example, shows rates of suicide and emotional problems are lower among people involved with social support networks such as their families and friends than among people who are pretty much alone (Maimon & Kuhl, 2008). However, our primary group relationships may also not be ideal, and, if they are negative ones, they may cause us much mental and emotional distress. In this regard, the family as a primary group is the setting for much physical and sexual violence committed against women and children (Gosselin, 2010) (see Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” ).

A secondary group is larger and more impersonal than a primary group and may exist for a relatively short time to achieve a specific purpose. The students in any one of your college courses constitute a secondary group.

Jeremy Wilburn – Students in Classrooms at UIS – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Although primary groups are the most important ones in our lives, we belong to many more secondary groups , which are groups that are larger and more impersonal and exist, often for a relatively short time, to achieve a specific purpose. Secondary group members feel less emotionally attached to each other than do primary group members and do not identify as much with their group nor feel as loyal to it. This does not mean secondary groups are unimportant, as society could not exist without them, but they still do not provide the potential emotional benefits for their members that primary groups ideally do. The sociology class for which you are reading this book is an example of a secondary group, as are the clubs and organizations on your campus to which you might belong. Other secondary groups include religious, business, governmental, and civic organizations. In some of these groups, members get to know each other better than in other secondary groups, but their emotional ties and intensity of interaction generally remain much weaker than in primary groups.

Reference Groups

Primary and secondary groups can act both as our reference groups or as groups that set a standard for guiding our own behavior and attitudes. The family we belong to obviously affects our actions and views, as, for example, there were probably times during your adolescence when you decided not to do certain things with your friends to avoid disappointing or upsetting your parents. On the other hand, your friends regularly acted during your adolescence as a reference group, and you probably dressed the way they did or did things with them, even against your parents’ wishes, precisely because they were your reference group. Some of our reference groups are groups to which we do not belong but to which we nonetheless want to belong. A small child, for example, may dream of becoming an astronaut and dress like one and play like one. Some high school students may not belong to the “cool” clique in school but may still dress like the members of this clique, either in hopes of being accepted as a member or simply because they admire the dress and style of its members.

Samuel Stouffer and colleagues (Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, Star, & Williams, 1949) demonstrated the importance of reference groups in a well-known study of American soldiers during World War II. This study sought to determine why some soldiers were more likely than others to have low morale. Surprisingly, Stouffer found that the actual, “objective” nature of their living conditions affected their morale less than whether they felt other soldiers were better or worse off than they were. Even if their own living conditions were fairly good, they were likely to have low morale if they thought other soldiers were doing better. Another factor affecting their morale was whether they thought they had a good chance of being promoted. Soldiers in units with high promotion rates were, paradoxically, more pessimistic about their own chances of promotion than soldiers in units with low promotion rates. Evidently the former soldiers were dismayed by seeing so many other men in their unit getting promoted and felt worse off as a result. In each case, Stouffer concluded, the soldiers’ views were shaped by their perceptions of what was happening in their reference group of other soldiers. They felt deprived relative to the experiences of the members of their reference group and adjusted their views accordingly. The concept of relative deprivation captures this process.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

Members of primary and some secondary groups feel loyal to those groups and take pride in belonging to them. We call such groups in-groups . Fraternities, sororities, sports teams, and juvenile gangs are examples of in-groups. Members of an in-group often end up competing with members of another group for various kinds of rewards. This other group is called an out-group . The competition between in-groups and out-groups is often friendly, as among members of intramural teams during the academic year when they vie in athletic events. Sometimes, however, in-group members look down their noses at out-group members and even act very hostilely toward them. Rival fraternity members at several campuses have been known to get into fights and trash each other’s houses. More seriously, street gangs attack each other, and hate groups such as skinheads and the Ku Klux Klan have committed violence against people of color, Jews, and other individuals they consider members of out-groups. As these examples make clear, in-group membership can promote very negative attitudes toward the out-groups with which the in-groups feel they are competing. These attitudes are especially likely to develop in times of rising unemployment and other types of economic distress, as in-group members are apt to blame out-group members for their economic problems (Olzak, 1992).

Social Networks

These days in the job world we often hear of “networking,” or taking advantage of your connections with people who have connections to other people who can help you land a job. You do not necessarily know these “other people” who ultimately can help you, but you do know the people who know them. Your ties to the other people are weak or nonexistent, but your involvement in this network may nonetheless help you find a job.

Modern life is increasingly characterized by such social networks , or the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. Some of these relationships involve strong bonds, while other relationships involve weak bonds (Granovetter, 1983). Facebook and other Web sites have made possible networks of a size unimaginable just a decade ago. Social networks are important for many things, including getting advice, borrowing small amounts of money, and finding a job. When you need advice or want to borrow $5 or $10, to whom do you turn? The answer is undoubtedly certain members of your social networks—your friends, family, and so forth.

The indirect links you have to people through your social networks can help you find a job or even receive better medical care. For example, if you come down with a serious condition such as cancer, you would probably first talk with your primary care physician, who would refer you to one or more specialists whom you do not know and who have no connections to you through other people you know. That is, they are not part of your social network. Because the specialists do not know you and do not know anyone else who knows you, they are likely to treat you very professionally, which means, for better or worse, impersonally.

A social network is the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. Our involvement in certain networks can bring certain advantages, including better medical care if one’s network includes a physician or two.

Gavin Llewellyn – My social networks – CC BY 2.0.

Now suppose you have some nearby friends or relatives who are physicians. Because of their connections with other nearby physicians, they can recommend certain specialists to you and perhaps even get you an earlier appointment than your primary physician could. Because these specialists realize you know physicians they know, they may treat you more personally than otherwise. In the long run, you may well get better medical care from your network through the physicians you know. People lucky enough to have such connections may thus be better off medically than people who do not.

But let’s look at this last sentence. What kinds of people have such connections? What kinds of people have friends or relatives who are physicians? All other things being equal, if you had two people standing before you, one employed as a vice president in a large corporation and the other working part time at a fast-food restaurant, which person do you think would be more likely to know a physician or two personally? Your answer is probably the corporate vice president. The point is that factors such as our social class and occupational status, our race and ethnicity, and our gender affect how likely we are to have social networks that can help us get jobs, good medical care, and other advantages. As just one example, a study of three working-class neighborhoods in New York City—one white, one African American, and one Latino—found that white youths were more involved through their parents and peers in job-referral networks than youths in the other two neighborhoods and thus were better able to find jobs, even if they had been arrested for delinquency (Sullivan, 1989). This study suggests that even if we look at people of different races and ethnicities in roughly the same social class, whites have an advantage over people of color in the employment world.

Gender also matters in the employment world. In many businesses, there still exists an “old boys’ network,” in which male executives with job openings hear about male applicants from male colleagues and friends. Male employees already on the job tend to spend more social time with their male bosses than do their female counterparts. These related processes make it more difficult for females than for males to be hired and promoted (Barreto, Ryan, & Schmitt, 2009). To counter these effects and to help support each other, some women form networks where they meet, talk about mutual problems, and discuss ways of dealing with these problems. An example of such a network is The Links, Inc., a community service group of 12,000 professional African American women whose name underscores the importance of networking ( http://www.linksinc.org/index.shtml ). Its members participate in 270 chapters in 42 states; Washington, DC; and the Bahamas. Every two years, more than 2,000 Links members convene for a national assembly at which they network, discuss the problems they face as professional women of color, and consider fund-raising strategies for the causes they support.

Key Takeaways

- Groups are a key building block of social life but can also have negative consequences.

- Primary groups are generally small and include intimate relationships, while secondary groups are larger and more impersonal.

- Reference groups provide a standard for guiding and evaluating our attitudes and behaviors.

- Social networks are increasingly important in modern life, and involvement in such networks may have favorable consequences for many aspects of one’s life.

For Your Review

- Briefly describe one reference group that has influenced your attitudes or behavior, and explain why it had this influence on you.

- Briefly describe an example of when one of your social networks proved helpful to you (or describe an example when a social network helped someone you know).

- List at least five secondary groups to which you now belong and/or to which you previously belonged.

Barreto, M., Ryan, M. K., & Schmitt, M. T. (Eds.). (2009). The glass ceiling in the 21st century: Understanding barriers to gender equality . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Elsesser, K., & Peplau L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59 , 1077–1100.

Gosselin, D. K. (2010). Heavy hands: An introduction to the crimes of family violence (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.

Maimon, D., & Kuhl, D. C. (2008). Social control and youth suicidality: Situating Durkheim’s ideas in a multilevel framework. American Sociological Review, 73, 921–943.

Marks, S. R. (1994). Intimacy in the public realm: The case of co-workers. Social Forces, 72, 843–858.

Olzak, S. (1992). The dynamics of ethnic competition and conflict . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., DeVinney, L. C., Star, S. A., & Williams, R. M., Jr. (1949). The American soldier: Adjustment during army life (Studies in Social Psychology in World War II, Vol. 1). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sullivan, M. (1989). Getting paid: Youth crime and work in the inner city . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Social Groups

Learning objectives.

- Describe how a social group differs from a social category or social aggregate.

- Distinguish a primary group from a secondary group.

- Define a reference group and provide one example of such a group.

- Explain the importance of networks in a modern society.

Most of us feel comfortable using the word “group” without giving it much thought. In everyday use, it can be a generic term, although it carries important clinical and scientific meanings. Moreover, the concept of a group is central to much of how we think about society and human interaction. Often, we might mean different things by using that word. We might say that a group of kids all saw the dog, and it could mean 250 students in a lecture hall or four siblings playing on a front lawn. In everyday conversation, there isn’t a clear distinguishing use. So how can we hone the meaning more precisely for sociological purposes?

Defining a Group

The term group is an amorphous one and can refer to a wide variety of gatherings, from just two people (think about a “group project” in school when you partner with another student), a club, a regular gathering of friends, or people who work together or share a hobby. In short, the term refers to any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share a sense that their identity is somehow aligned with the group. Of course, every time people are gathered it is not necessarily a group. A rally is usually a one-time event, for instance, and belonging to a political party doesn’t imply interaction with others. People who exist in the same place at the same time but who do not interact or share a sense of identity—such as a bunch of people standing in line at Starbucks—are considered an aggregate , or a crowd. Another example of a nongroup is people who share similar characteristics but are not tied to one another in any way. These people are considered a category , and as an example all children born from approximately 1980–2000 are referred to as “Millennials.” Why are Millennials a category and not a group? Because while some of them may share a sense of identity, they do not, as a whole, interact frequently with each other.

Interestingly, people within an aggregate or category can become a group. During disasters, people in a neighborhood (an aggregate) who did not know each other might become friendly and depend on each other at the local shelter. After the disaster ends and the people go back to simply living near each other, the feeling of cohesiveness may last since they have all shared an experience. They might remain a group, practicing emergency readiness, coordinating supplies for next time, or taking turns caring for neighbors who need extra help. Similarly, there may be many groups within a single category. Consider teachers, for example. Within this category, groups may exist like teachers’ unions, teachers who coach, or staff members who are involved with the PTA.

Types of Groups

Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929) suggested that groups can broadly be divided into two categories: primary groups and secondary groups (Cooley 1909). According to Cooley, primary groups play the most critical role in our lives. The primary group is usually fairly small and is made up of individuals who generally engage face-to-face in long-term emotional ways. This group serves emotional needs: expressive functions rather than pragmatic ones. The primary group is usually made up of significant others, those individuals who have the most impact on our socialization. The best example of a primary group is the family.

Secondary groups are often larger and impersonal. They may also be task-focused and time-limited. These groups serve an instrumental function rather than an expressive one, meaning that their role is more goal- or task-oriented than emotional. A classroom or office can be an example of a secondary group. Neither primary nor secondary groups are bound by strict definitions or set limits. In fact, people can move from one group to another. A graduate seminar, for example, can start as a secondary group focused on the class at hand, but as the students work together throughout their program, they may find common interests and strong ties that transform them into a primary group.

SOCIOLOGY IN THE REAL WORLD

Best friends she’s never met.

Writer Allison Levy worked alone. While she liked the freedom and flexibility of working from home, she sometimes missed having a community of coworkers, both for the practical purpose of brainstorming and the more social “water cooler” aspect. Levy did what many do in the Internet age: she found a group of other writers online through a web forum. Over time, a group of approximately twenty writers, who all wrote for a similar audience, broke off from the larger forum and started a private invitation-only forum. While writers in general represent all genders, ages, and interests, it ended up being a collection of twenty- and thirty-something women who comprised the new forum; they all wrote fiction for children and young adults.

At first, the writers’ forum was clearly a secondary group united by the members’ professions and work situations. As Levy explained, “On the Internet, you can be present or absent as often as you want. No one is expecting you to show up.” It was a useful place to research information about different publishers and about who had recently sold what and to track industry trends. But as time passed, Levy found it served a different purpose. Since the group shared other characteristics beyond their writing (such as age and gender), the online conversation naturally turned to matters such as child-rearing, aging parents, health, and exercise. Levy found it was a sympathetic place to talk about any number of subjects, not just writing. Further, when people didn’t post for several days, others expressed concern, asking whether anyone had heard from the missing writers. It reached a point where most members would tell the group if they were traveling or needed to be offline for awhile.

The group continued to share. One member on the site who was going through a difficult family illness wrote, “I don’t know where I’d be without you women. It is so great to have a place to vent that I know isn’t hurting anyone.” Others shared similar sentiments.

So is this a primary group? Most of these people have never met each other. They live in Hawaii, Australia, Minnesota, and across the world. They may never meet. Levy wrote recently to the group, saying, “Most of my ‘real-life’ friends and even my husband don’t really get the writing thing. I don’t know what I’d do without you.” Despite the distance and the lack of physical contact, the group clearly fills an expressive need.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

One of the ways that groups can be powerful is through inclusion, and its inverse, exclusion. The feeling that we belong in an elite or select group is a heady one, while the feeling of not being allowed in, or of being in competition with a group, can be motivating in a different way. Sociologist William Sumner (1840–1910) developed the concepts of in-group and out-group to explain this phenomenon (Sumner 1906). In short, an in-group is the group that an individual feels she belongs to, and she believes it to be an integral part of who she is. An out-group , conversely, is a group someone doesn’t belong to; often we may feel disdain or competition in relationship to an out-group. Sports teams, unions, and sororities are examples of in-groups and out-groups; people may belong to, or be an outsider to, any of these. Primary groups consist of both in-groups and out-groups, as do secondary groups.

While group affiliations can be neutral or even positive, such as the case of a team sport competition, the concept of in-groups and out-groups can also explain some negative human behavior, such as white supremacist movements like the Ku Klux Klan, or the bullying of gay or lesbian students. By defining others as “not like us” and inferior, in-groups can end up practicing ethnocentrism, racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism—manners of judging others negatively based on their culture, race, sex, age, or sexuality. Often, in-groups can form within a secondary group. For instance, a workplace can have cliques of people, from senior executives who play golf together, to engineers who write code together, to young singles who socialize after hours. While these in-groups might show favoritism and affinity for other in-group members, the overall organization may be unable or unwilling to acknowledge it. Therefore, it pays to be wary of the politics of in-groups, since members may exclude others as a form of gaining status within the group.

BIG PICTURE

Bullying and cyberbullying: how technology has changed the game.

Most of us know that the old rhyme “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is inaccurate. Words can hurt, and never is that more apparent than in instances of bullying. Bullying has always existed and has often reached extreme levels of cruelty in children and young adults. People at these stages of life are especially vulnerable to others’ opinions of them, and they’re deeply invested in their peer groups. Today, technology has ushered in a new era of this dynamic. Cyberbullying is the use of interactive media by one person to torment another, and it is on the rise. Cyberbullying can mean sending threatening texts, harassing someone in a public forum (such as Facebook), hacking someone’s account and pretending to be him or her, posting embarrassing images online, and so on. A study by the Cyberbullying Research Center found that 20 percent of middle school students admitted to “seriously thinking about committing suicide” as a result of online bullying (Hinduja and Patchin 2010). Whereas bullying face-to-face requires willingness to interact with your victim, cyberbullying allows bullies to harass others from the privacy of their homes without witnessing the damage firsthand. This form of bullying is particularly dangerous because it’s widely accessible and therefore easier to accomplish.

Cyberbullying, and bullying in general, made international headlines in 2010 when a fifteen-year-old girl, Phoebe Prince, in South Hadley, Massachusetts, committed suicide after being relentlessly bullied by girls at her school. In the aftermath of her death, the bullies were prosecuted in the legal system and the state passed anti-bullying legislation. This marked a significant change in how bullying, including cyberbullying, is viewed in the United States. Now there are numerous resources for schools, families, and communities to provide education and prevention on this issue. The White House hosted a Bullying Prevention summit in March 2011, and President and First Lady Obama have used Facebook and other social media sites to discuss the importance of the issue.

According to a report released in 2013 by the National Center for Educational Statistics, close to 1 in every 3 (27.8 percent) students report being bullied by their school peers. Seventeen percent of students reported being the victims of cyberbullying.

Will legislation change the behavior of would-be cyberbullies? That remains to be seen. But we can hope communities will work to protect victims before they feel they must resort to extreme measures.

Reference Groups

A reference group is a group that people compare themselves to—it provides a standard of measurement. In U.S. society, peer groups are common reference groups. Kids and adults pay attention to what their peers wear, what music they like, what they do with their free time—and they compare themselves to what they see. Most people have more than one reference group, so a middle school boy might look not just at his classmates but also at his older brother’s friends and see a different set of norms. And he might observe the antics of his favorite athletes for yet another set of behaviors.

Some other examples of reference groups can be one’s cultural center, workplace, family gathering, and even parents. Often, reference groups convey competing messages. For instance, on television and in movies, young adults often have wonderful apartments and cars and lively social lives despite not holding a job. In music videos, young women might dance and sing in a sexually aggressive way that suggests experience beyond their years. At all ages, we use reference groups to help guide our behavior and show us social norms. So how important is it to surround yourself with positive reference groups? You may not recognize a reference group, but it still influences the way you act. Identifying your reference groups can help you understand the source of the social identities you aspire to or want to distance yourself from.

College: A World of In-Groups, Out-Groups, and Reference Groups

For a student entering college, the sociological study of groups takes on an immediate and practical meaning. After all, when we arrive someplace new, most of us glance around to see how well we fit in or stand out in the ways we want. This is a natural response to a reference group, and on a large campus, there can be many competing groups. Say you are a strong athlete who wants to play intramural sports, and your favorite musicians are a local punk band. You may find yourself engaged with two very different reference groups.

These reference groups can also become your in-groups or out-groups. For instance, different groups on campus might solicit you to join. Are there fraternities and sororities at your school? If so, chances are they will try to convince students—that is, students they deem worthy—to join them. And if you love playing soccer and want to play on a campus team, but you’re wearing shredded jeans, combat boots, and a local band T-shirt, you might have a hard time convincing the soccer team to give you a chance. While most campus groups refrain from insulting competing groups, there is a definite sense of an in-group versus an out-group. “Them?” a member might say. “They’re all right, but their parties are nowhere near as cool as ours.” Or, “Only serious engineering geeks join that group.” This immediate categorization into in-groups and out-groups means that students must choose carefully, since whatever group they associate with won’t just define their friends—it may also define their enemies.

Social Networks

These days in the job world we often hear of “networking,” or taking advantage of your connections with people who have connections to other people who can help you land a job. You do not necessarily know these “other people” who ultimately can help you, but you do know the people who know them. Your ties to the other people are weak or nonexistent, but your involvement in this network may nonetheless help you find a job.

Modern life is increasingly characterized by such social networks , or the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. Some of these relationships involve strong bonds, while other relationships involve weak bonds (Granovetter, 1983). Facebook and other Web sites have made possible networks of a size unimaginable just a decade ago. Social networks are important for many things, including getting advice, borrowing small amounts of money, and finding a job. When you need advice or want to borrow $5 or $10, to whom do you turn? The answer is undoubtedly certain members of your social networks—your friends, family, and so forth.

The indirect links you have to people through your social networks can help you find a job or even receive better medical care. For example, if you come down with a serious condition such as cancer, you would probably first talk with your primary care physician, who would refer you to one or more specialists whom you do not know and who have no connections to you through other people you know. That is, they are not part of your social network. Because the specialists do not know you and do not know anyone else who knows you, they are likely to treat you very professionally, which means, for better or worse, impersonally.

Gavin Llewellyn – My social networks – CC BY 2.0.

Now suppose you have some nearby friends or relatives who are physicians. Because of their connections with other nearby physicians, they can recommend certain specialists to you and perhaps even get you an earlier appointment than your primary physician could. Because these specialists realize you know physicians they know, they may treat you more personally than otherwise. In the long run, you may well get better medical care from your network through the physicians you know. People lucky enough to have such connections may thus be better off medically than people who do not.

But let’s look at this last sentence. What kinds of people have such connections? What kinds of people have friends or relatives who are physicians? All other things being equal, if you had two people standing before you, one employed as a vice president in a large corporation and the other working part time at a fast-food restaurant, which person do you think would be more likely to know a physician or two personally? Your answer is probably the corporate vice president. The point is that factors such as our social class and occupational status, our race and ethnicity, and our gender affect how likely we are to have social networks that can help us get jobs, good medical care, and other advantages. As just one example, a study of three working-class neighborhoods in New York City—one white, one African American, and one Latino—found that white youths were more involved through their parents and peers in job-referral networks than youths in the other two neighborhoods and thus were better able to find jobs, even if they had been arrested for delinquency (Sullivan, 1989). This study suggests that even if we look at people of different races and ethnicities in roughly the same social class, whites have an advantage over people of color in the employment world.

Gender also matters in the employment world. In many businesses, there still exists an “old boys’ network,” in which male executives with job openings hear about male applicants from male colleagues and friends. Male employees already on the job tend to spend more social time with their male bosses than do their female counterparts. These related processes make it more difficult for females than for males to be hired and promoted (Barreto, Ryan, & Schmitt, 2009). To counter these effects and to help support each other, some women form networks where they meet, talk about mutual problems, and discuss ways of dealing with these problems. An example of such a network is The Links, Inc., a community service group of 12,000 professional African American women whose name underscores the importance of networking ( http://www.linksinc.org/index.shtml ). Its members participate in 270 chapters in 42 states; Washington, DC; and the Bahamas. Every two years, more than 2,000 Links members convene for a national assembly at which they network, discuss the problems they face as professional women of color, and consider fund-raising strategies for the causes they support.

Key Takeaways

- Groups are a key building block of social life but can also have negative consequences.

- Primary groups are generally small and include intimate relationships, while secondary groups are larger and more impersonal.

- Reference groups provide a standard for guiding and evaluating our attitudes and behaviors.

- Social networks are increasingly important in modern life, and involvement in such networks may have favorable consequences for many aspects of one’s life.

Barreto, M., Ryan, M. K., & Schmitt, M. T. (Eds.). (2009). The glass ceiling in the 21st century: Understanding barriers to gender equality . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Elsesser, K., & Peplau L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59 , 1077–1100.

Gosselin, D. K. (2010). Heavy hands: An introduction to the crimes of family violence (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.

Maimon, D., & Kuhl, D. C. (2008). Social control and youth suicidality: Situating Durkheim’s ideas in a multilevel framework. American Sociological Review, 73, 921–943.

Marks, S. R. (1994). Intimacy in the public realm: The case of co-workers. Social Forces, 72, 843–858.

Olzak, S. (1992). The dynamics of ethnic competition and conflict . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., DeVinney, L. C., Star, S. A., & Williams, R. M., Jr. (1949). The American soldier: Adjustment during army life (Studies in Social Psychology in World War II, Vol. 1). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sullivan, M. (1989). Getting paid: Youth crime and work in the inner city . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13 The Psychology of Groups

This module assumes that a thorough understanding of people requires a thorough understanding of groups. Each of us is an autonomous individual seeking our own objectives, yet we are also members of groups—groups that constrain us, guide us, and sustain us. Just as each of us influences the group and the people in the group, so, too, do groups change each one of us. Joining groups satisfies our need to belong, gain information and understanding through social comparison, define our sense of self and social identity, and achieve goals that might elude us if we worked alone. Groups are also practically significant, for much of the world’s work is done by groups rather than by individuals. Success sometimes eludes our groups, but when group members learn to work together as a cohesive team their success becomes more certain. People also turn to groups when important decisions must be made, and this choice is justified as long as groups avoid such problems as group polarization and groupthink.

Learning Objectives

- Review the evidence that suggests humans have a fundamental need to belong to groups.

- Compare the sociometer model of self-esteem to a more traditional view of self-esteem.

- Use theories of social facilitation to predict when a group will perform tasks slowly or quickly (e.g., students eating a meal as a group, workers on an assembly line, or a study group).

- Summarize the methods used by Latané, Williams, and Harkins to identify the relative impact of social loafing and coordination problems on group performance.

- Describe how groups change over time.

- Apply the theory of groupthink to a well-known decision-making group, such as the group of advisors responsible for planning the Bay of Pigs operation.

- List and discuss the factors that facilitate and impede group performance and decision making.

- Develop a list of recommendations that, if followed, would minimize the possibility of groupthink developing in a group.

The Psychology of Groups

Psychologists study groups because nearly all human activities—working, learning, worshiping, relaxing, playing, and even sleeping—occur in groups. The lone individual who is cut off from all groups is a rarity. Most of us live out our lives in groups, and these groups have a profound impact on our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Many psychologists focus their attention on single individuals, but social psychologists expand their analysis to include groups, organizations, communities, and even cultures.

This module examines the psychology of groups and group membership. It begins with a basic question: What is the psychological significance of groups? People are, undeniably, more often in groups rather than alone. What accounts for this marked gregariousness and what does it say about our psychological makeup? The module then reviews some of the key findings from studies of groups. Researchers have asked many questions about people and groups: Do people work as hard as they can when they are in groups? Are groups more cautious than individuals? Do groups make wiser decisions than single individuals? In many cases the answers are not what common sense and folk wisdom might suggest.

The Psychological Significance of Groups

Many people loudly proclaim their autonomy and independence. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, they avow, “I must be myself. I will not hide my tastes or aversions . . . . I will seek my own” ( 1903/2004 , p. 127). Even though people are capable of living separate and apart from others, they join with others because groups meet their psychological and social needs.

The Need to Belong

Across individuals, societies, and even eras, humans consistently seek inclusion over exclusion, membership over isolation, and acceptance over rejection. As Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary conclude, humans have a need to belong : “a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and impactful interpersonal relationships” ( 1995 , p. 497). And most of us satisfy this need by joining groups. When surveyed, 87.3% of Americans reported that they lived with other people, including family members, partners, and roommates ( Davis & Smith, 2007 ). The majority, ranging from 50% to 80%, reported regularly doing things in groups, such as attending a sports event together, visiting one another for the evening, sharing a meal together, or going out as a group to see a movie ( Putnam, 2000 ).

People respond negatively when their need to belong is unfulfilled. For example, college students often feel homesick and lonely when they first start college, but not if they belong to a cohesive, socially satisfying group ( Buote et al., 2007 ). People who are accepted members of a group tend to feel happier and more satisfied. But should they be rejected by a group, they feel unhappy, helpless, and depressed. Studies of ostracism —the deliberate exclusion from groups—indicate this experience is highly stressful and can lead to depression, confused thinking, and even aggression ( Williams, 2007 ). When researchers used a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner to track neural responses to exclusion, they found that people who were left out of a group activity displayed heightened cortical activity in two specific areas of the brain—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. These areas of the brain are associated with the experience of physical pain sensations ( Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003 ). It hurts, quite literally, to be left out of a group.

Affiliation in Groups

Groups not only satisfy the need to belong, they also provide members with information, assistance, and social support. Leon Festinger’s theory of social comparison ( 1950 , 1954 ) suggested that in many cases people join with others to evaluate the accuracy of their personal beliefs and attitudes. Stanley Schachter ( 1959 ) explored this process by putting individuals in ambiguous, stressful situations and asking them if they wished to wait alone or with others. He found that people affiliate in such situations—they seek the company of others.

Although any kind of companionship is appreciated, we prefer those who provide us with reassurance and support as well as accurate information. In some cases, we also prefer to join with others who are even worse off than we are. Imagine, for example, how you would respond when the teacher hands back the test and yours is marked 85%. Do you want to affiliate with a friend who got a 95% or a friend who got a 78%? To maintain a sense of self-worth, people seek out and compare themselves to the less fortunate. This process is known as downward social comparison .

Identity and Membership

Groups are not only founts of information during times of ambiguity, they also help us answer the existentially significant question, “Who am I?” Common sense tells us that our sense of self is our private definition of who we are, a kind of archival record of our experiences, qualities, and capabilities. Yet, the self also includes all those qualities that spring from memberships in groups. People are defined not only by their traits, preferences, interests, likes, and dislikes, but also by their friendships, social roles, family connections, and group memberships. The self is not just a “me,” but also a “we.”

Even demographic qualities such as sex or age can influence us if we categorize ourselves based on these qualities. Social identity theory , for example, assumes that we don’t just classify other people into such social categories as man, woman, Anglo, elderly, or college student, but we also categorize ourselves. Moreover, if we strongly identify with these categories, then we will ascribe the characteristics of the typical member of these groups to ourselves, and so stereotype ourselves. If, for example, we believe that college students are intellectual, then we will assume we, too, are intellectual if we identify with that group ( Hogg, 2001 ).

Groups also provide a variety of means for maintaining and enhancing a sense of self-worth, as our assessment of the quality of groups we belong to influences our collective self-esteem ( Crocker & Luhtanen, 1990 ). If our self-esteem is shaken by a personal setback, we can focus on our group’s success and prestige. In addition, by comparing our group to other groups, we frequently discover that we are members of the better group, and so can take pride in our superiority. By denigrating other groups, we elevate both our personal and our collective self-esteem ( Crocker & Major, 1989 ).

Mark Leary’s sociometer model goes so far as to suggest that “self-esteem is part of a sociometer that monitors peoples’ relational value in other people’s eyes” ( 2007 , p. 328). He maintains self-esteem is not just an index of one’s sense of personal value, but also an indicator of acceptance into groups. Like a gauge that indicates how much fuel is left in the tank, a dip in self-esteem indicates exclusion from our group is likely. Disquieting feelings of self-worth, then, prompt us to search for and correct characteristics and qualities that put us at risk of social exclusion. Self-esteem is not just high self-regard, but the self-approbation that we feel when included in groups ( Leary & Baumeister, 2000 ).

Evolutionary Advantages of Group Living

Groups may be humans’ most useful invention, for they provide us with the means to reach goals that would elude us if we remained alone. Individuals in groups can secure advantages and avoid disadvantages that would plague the lone individuals. In his theory of social integration, Moreland concludes that groups tend to form whenever “people become dependent on one another for the satisfaction of their needs” ( 1987 , p. 104). The advantages of group life may be so great that humans are biologically prepared to seek membership and avoid isolation. From an evolutionary psychology perspective, because groups have increased humans’ overall fitness for countless generations, individuals who carried genes that promoted solitude-seeking were less likely to survive and procreate compared to those with genes that prompted them to join groups ( Darwin, 1859/1963 ). This process of natural selection culminated in the creation of a modern human who seeks out membership in groups instinctively, for most of us are descendants of “joiners” rather than “loners.”

Motivation and Performance

Groups usually exist for a reason. In groups, we solve problems, create products, create standards, communicate knowledge, have fun, perform arts, create institutions, and even ensure our safety from attacks by other groups. But do groups always outperform individuals?

Social Facilitation in Groups

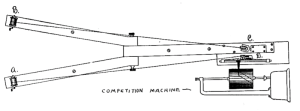

Do people perform more effectively when alone or when part of a group? Norman Triplett ( 1898 ) examined this issue in one of the first empirical studies in psychology. While watching bicycle races, Triplett noticed that cyclists were faster when they competed against other racers than when they raced alone against the clock. To determine if the presence of others leads to the psychological stimulation that enhances performance, he arranged for 40 children to play a game that involved turning a small reel as quickly as possible (see Figure 1). When he measured how quickly they turned the reel, he confirmed that children performed slightly better when they played the game in pairs compared to when they played alone (see Stroebe, 2012 ; Strube, 2005 ).

Triplett succeeded in sparking interest in a phenomenon now known as social facilitation : the enhancement of an individual’s performance when that person works in the presence of other people. However, it remained for Robert Zajonc ( 1965 ) to specify when social facilitation does and does not occur. After reviewing prior research, Zajonc noted that the facilitating effects of an audience usually only occur when the task requires the person to perform dominant responses, i.e., ones that are well-learned or based on instinctive behaviors. If the task requires nondominant responses, i.e., novel, complicated, or untried behaviors that the organism has never performed before or has performed only infrequently, then the presence of others inhibits performance. Hence, students write poorer quality essays on complex philosophical questions when they labor in a group rather than alone ( Allport, 1924 ), but they make fewer mistakes in solving simple, low-level multiplication problems with an audience or a coactor than when they work in isolation ( Dashiell, 1930 ).

Social facilitation, then, depends on the task: other people facilitate performance when the task is so simple that it requires only dominant responses, but others interfere when the task requires nondominant responses. However, a number of psychological processes combine to influence when social facilitation, not social interference, occurs. Studies of the challenge-threat response and brain imaging, for example, confirm that we respond physiologically and neurologically to the presence of others ( Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, & Salomon, 1999 ). Other people also can trigger evaluation apprehension, particularly when we feel that our individual performance will be known to others, and those others might judge it negatively ( Bond, Atoum, & VanLeeuwen, 1996 ). The presence of other people can also cause perturbations in our capacity to concentrate on and process information ( Harkins, 2006 ). Distractions due to the presence of other people have been shown to improve performance on certain tasks, such as the Stroop task , but undermine performance on more cognitively demanding tasks ( Huguet, Galvaing, Monteil, & Dumas, 1999 ).

Social Loafing

Groups usually outperform individuals. A single student, working alone on a paper, will get less done in an hour than will four students working on a group project. One person playing a tug-of-war game against a group will lose. A crew of movers can pack up and transport your household belongings faster than you can by yourself. As the saying goes, “Many hands make light the work” ( Littlepage, 1991 ; Steiner, 1972 ).

Groups, though, tend to be underachievers. Studies of social facilitation confirmed the positive motivational benefits of working with other people on well-practiced tasks in which each member’s contribution to the collective enterprise can be identified and evaluated. But what happens when tasks require a truly collective effort? First, when people work together they must coordinate their individual activities and contributions to reach the maximum level of efficiency—but they rarely do ( Diehl & Stroebe, 1987 ). Three people in a tug-of-war competition, for example, invariably pull and pause at slightly different times, so their efforts are uncoordinated. The result is coordination loss : the three-person group is stronger than a single person, but not three times as strong. Second, people just don’t exert as much effort when working on a collective endeavor, nor do they expend as much cognitive effort trying to solve problems, as they do when working alone. They display social loafing ( Latané, 1981 ).

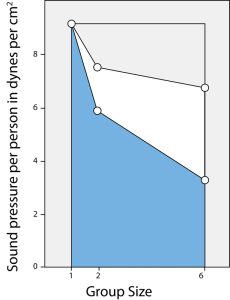

Bibb Latané, Kip Williams, and Stephen Harkins ( 1979 ) examined both coordination losses and social loafing by arranging for students to cheer or clap either alone or in groups of varying sizes. The students cheered alone or in 2- or 6-person groups, or they were lead to believe they were in 2- or 6-person groups (those in the “pseudo-groups” wore blindfolds and headsets that played masking sound). As Figure 2 indicates, groups generated more noise than solitary subjects, but the productivity dropped as the groups became larger in size. In dyads, each subject worked at only 66% of capacity, and in 6-person groups at 36%. Productivity also dropped when subjects merely believed they were in groups. If subjects thought that one other person was shouting with them, they shouted 82% as intensely, and if they thought five other people were shouting, they reached only 74% of their capacity. These loses in productivity were not due to coordination problems; this decline in production could be attributed only to a reduction in effort—to social loafing (Latané et al., 1979, Experiment 2).

Social loafing is no rare phenomenon. When sales personnel work in groups with shared goals, they tend to “take it easy” if another salesperson is nearby who can do their work ( George, 1992 ). People who are trying to generate new, creative ideas in group brainstorming sessions usually put in less effort and are thus less productive than people who are generating new ideas individually ( Paulus & Brown, 2007 ). Students assigned group projects often complain of inequity in the quality and quantity of each member’s contributions: Some people just don’t work as much as they should to help the group reach its learning goals ( Neu, 2012 ). People carrying out all sorts of physical and mental tasks expend less effort when working in groups, and the larger the group, the more they loaf ( Karau & Williams, 1993 ).

Groups can, however, overcome this impediment to performance through teamwork . A group may include many talented individuals, but they must learn how to pool their individual abilities and energies to maximize the team’s performance. Team goals must be set, work patterns structured, and a sense of group identity developed. Individual members must learn how to coordinate their actions, and any strains and stresses in interpersonal relations need to be identified and resolved ( Salas, Rosen, Burke, & Goodwin, 2009 ).

Researchers have identified two key ingredients to effective teamwork: a shared mental representation of the task and group unity. Teams improve their performance over time as they develop a shared understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting. Some semblance of this shared mental model is present nearly from its inception, but as the team practices, differences among the members in terms of their understanding of their situation and their team diminish as a consensus becomes implicitly accepted ( Tindale, Stawiski, & Jacobs, 2008 ).

Effective teams are also, in most cases, cohesive groups ( Dion, 2000 ). Group cohesion is the integrity, solidarity, social integration, or unity of a group. In most cases, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals. Members tend to enjoy their groups more when they are cohesive, and cohesive groups usually outperform ones that lack cohesion.

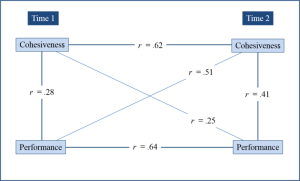

This cohesion-performance relationship, however, is a complex one. Meta-analytic studies suggest that cohesion improves teamwork among members, but that performance quality influences cohesion more than cohesion influences performance ( Mullen & Copper, 1994 ; Mullen, Driskell, & Salas, 1998 ; see Figure 3). Cohesive groups also can be spectacularly unproductive if the group’s norms stress low productivity rather than high productivity ( Seashore, 1954 ).

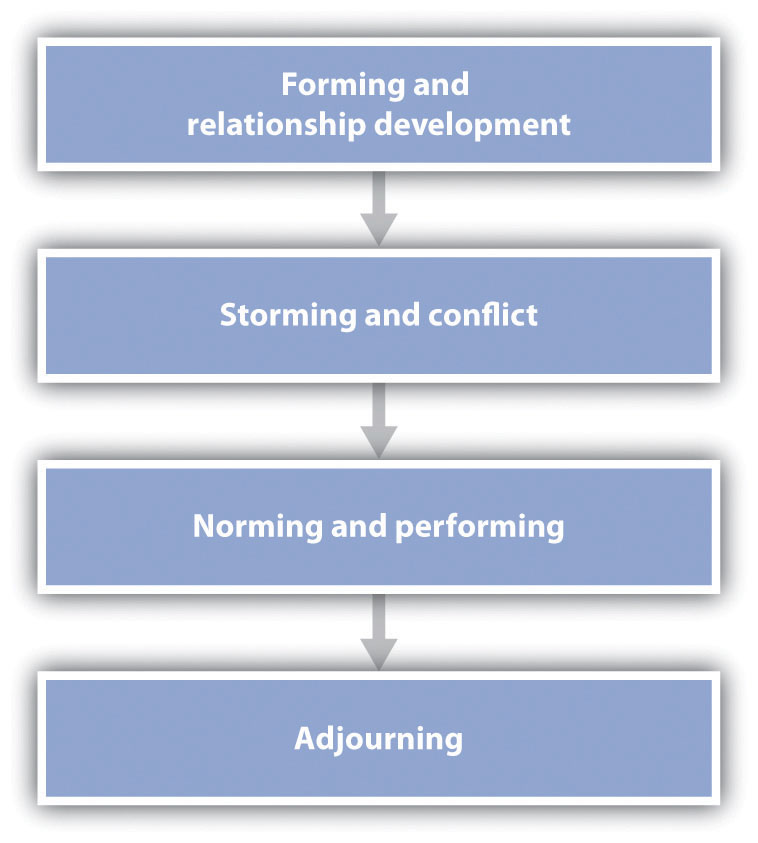

Group Development

In most cases groups do not become smooth-functioning teams overnight. As Bruce Tuckman’s ( 1965 ) theory of group development suggests, groups usually pass through several stages of development as they change from a newly formed group into an effective team. As noted in Focus Topic 1, in the forming phase, the members become oriented toward one another. In the storming phase, the group members find themselves in conflict, and some solution is sought to improve the group environment. In the norming, phase standards for behavior and roles develop that regulate behavior. In the performing, phase the group has reached a point where it can work as a unit to achieve desired goals, and the adjourning phase ends the sequence of development; the group disbands. Throughout these stages groups tend to oscillate between the task-oriented issues and the relationship issues, with members sometimes working hard but at other times strengthening their interpersonal bonds ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ).

Focus Topic 1: Group Development Stages and Characteristics

Stage 1 – “Forming”. Members expose information about themselves in polite but tentative interactions. They explore the purposes of the group and gather information about each other’s interests, skills, and personal tendencies.

Stage 2 – “Storming”. Disagreements about procedures and purposes surface, so criticism and conflict increase. Much of the conflict stems from challenges between members who are seeking to increase their status and control in the group.

Stage 3 – “Norming”. Once the group agrees on its goals, procedures, and leadership, norms, roles, and social relationships develop that increase the group’s stability and cohesiveness.

Stage 4 – “Performing”. The group focuses its energies and attention on its goals, displaying higher rates of task-orientation, decision-making, and problem-solving.

Stage 5 – “Adjourning”. The group prepares to disband by completing its tasks, reduces levels of dependency among members, and dealing with any unresolved issues.

Sources based on Tuckman (1965) and Tuckman & Jensen (1977)

We also experience change as we pass through a group, for we don’t become full-fledged members of a group in an instant. Instead, we gradually become a part of the group and remain in the group until we leave it. Richard Moreland and John Levine’s ( 1982 ) model of group socialization describes this process, beginning with initial entry into the group and ending when the member exits it. For example, when you are thinking of joining a new group—a social club, a professional society, a fraternity or sorority, or a sports team—you investigate what the group has to offer, but the group also investigates you. During this investigation stage you are still an outsider: interested in joining the group, but not yet committed to it in any way. But once the group accepts you and you accept the group, socialization begins: you learn the group’s norms and take on different responsibilities depending on your role. On a sports team, for example, you may initially hope to be a star who starts every game or plays a particular position, but the team may need something else from you. In time, though, the group will accept you as a full-fledged member and both sides in the process—you and the group itself—increase their commitment to one another. When that commitment wanes, however, your membership may come to an end as well.

Making Decisions in Groups

Groups are particularly useful when it comes to making a decision, for groups can draw on more resources than can a lone individual. A single individual may know a great deal about a problem and possible solutions, but his or her information is far surpassed by the combined knowledge of a group. Groups not only generate more ideas and possible solutions by discussing the problem, but they can also more objectively evaluate the options that they generate during discussion. Before accepting a solution, a group may require that a certain number of people favor it, or that it meets some other standard of acceptability. People generally feel that a group’s decision will be superior to an individual’s decision.

Groups, however, do not always make good decisions. Juries sometimes render verdicts that run counter to the evidence presented. Community groups take radical stances on issues before thinking through all the ramifications. Military strategists concoct plans that seem, in retrospect, ill-conceived and short-sighted. Why do groups sometimes make poor decisions?

Group Polarization

Let’s say you are part of a group assigned to make a presentation. One of the group members suggests showing a short video that, although amusing, includes some provocative images. Even though initially you think the clip is inappropriate, you begin to change your mind as the group discusses the idea. The group decides, eventually, to throw caution to the wind and show the clip—and your instructor is horrified by your choice.

This hypothetical example is consistent with studies of groups making decisions that involve risk. Common sense notions suggest that groups exert a moderating, subduing effect on their members. However, when researchers looked at groups closely, they discovered many groups shift toward more extreme decisions rather than less extreme decisions after group interaction. Discussion, it turns out, doesn’t moderate people’s judgments after all. Instead, it leads to group polarization : judgments made after group discussion will be more extreme in the same direction as the average of individual judgments made prior to discussion ( Myers & Lamm, 1976 ). If a majority of members feel that taking risks is more acceptable than exercising caution, then the group will become riskier after a discussion. For example, in France, where people generally like their government but dislike Americans, group discussion improved their attitude toward their government but exacerbated their negative opinions of Americans ( Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969 ). Similarly, prejudiced people who discussed racial issues with other prejudiced individuals became even more negative, but those who were relatively unprejudiced exhibited even more acceptance of diversity when in groups ( Myers & Bishop, 1970 ).

Common Knowledge Effect

One of the advantages of making decisions in groups is the group’s greater access to information. When seeking a solution to a problem, group members can put their ideas on the table and share their knowledge and judgments with each other through discussions. But all too often groups spend much of their discussion time examining common knowledge—information that two or more group members know in common—rather than unshared information. This common knowledge effect will result in a bad outcome if something known by only one or two group members is very important.

Researchers have studied this bias using the hidden profile task . On such tasks, information known to many of the group members suggests that one alternative, say Option A, is best. However, Option B is definitely the better choice, but all the facts that support Option B are only known to individual groups members—they are not common knowledge in the group. As a result, the group will likely spend most of its time reviewing the factors that favor Option A, and never discover any of its drawbacks. In consequence, groups often perform poorly when working on problems with nonobvious solutions that can only be identified by extensive information sharing ( Stasser & Titus, 1987 ).

Groups sometimes make spectacularly bad decisions. In 1961, a special advisory committee to President John F. Kennedy planned and implemented a covert invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs that ended in total disaster. In 1986, NASA carefully, and incorrectly, decided to launch the Challenger space shuttle in temperatures that were too cold.

Irving Janis ( 1982 ), intrigued by these kinds of blundering groups, carried out a number of case studies of such groups: the military experts that planned the defense of Pearl Harbor; Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs planning group; the presidential team that escalated the war in Vietnam. Each group, he concluded, fell prey to a distorted style of thinking that rendered the group members incapable of making a rational decision. Janis labeled this syndrome groupthink : “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action” (p. 9).

Janis identified both the telltale symptoms that signal the group is experiencing groupthink and the interpersonal factors that combine to cause groupthink. To Janis, groupthink is a disease that infects healthy groups, rendering them inefficient and unproductive. And like the physician who searches for symptoms that distinguish one disease from another, Janis identified a number of symptoms that should serve to warn members that they may be falling prey to groupthink. These symptoms include overestimating the group’s skills and wisdom, biased perceptions and evaluations of other groups and people who are outside of the group, strong conformity pressures within the group, and poor decision-making methods.

Janis also singled out four group-level factors that combine to cause groupthink: cohesion, isolation, biased leadership, and decisional stress.

- Cohesion : Groupthink only occurs in cohesive groups. Such groups have many advantages over groups that lack unity. People enjoy their membership much more in cohesive groups, they are less likely to abandon the group, and they work harder in pursuit of the group’s goals. But extreme cohesiveness can be dangerous. When cohesiveness intensifies, members become more likely to accept the goals, decisions, and norms of the group without reservation. Conformity pressures also rise as members become reluctant to say or do anything that goes against the grain of the group, and the number of internal disagreements—necessary for good decision making—decreases.