Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

- 3 Questions: How history helps us solve today's issues

3 Questions: How history helps us solve today's issues

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

Science and technology are essential tools for innovation, and to reap their full potential, we also need to articulate and solve the many aspects of today’s global issues that are rooted in the political, cultural, and economic realities of the human world. With that mission in mind, MIT's School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences has launched The Human Factor — an ongoing series of stories and interviews that highlight research on the human dimensions of global challenges. Contributors to this series also share ideas for cultivating the multidisciplinary collaborations needed to solve the major civilizational issues of our time.

Malick Ghachem is an attorney and a professor of history at MIT who explores questions of slavery and abolition, criminal law, and constitutional history. He is the author of "The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution" (Cambridge University Press, 2012), a history of the law of slavery in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) between 1685 and 1804. He teaches courses on the Age of Revolution, slavery and abolition, American criminal justice, and other topics. MIT SHASS Communications recently asked him to share his thoughts on how history can help people craft more effective public policies for today's world. Q: Your new research focuses on economic globalization and political protest in Haiti, a country with a complex social, political, and economic history. What lessons can we learn from Haiti's history that can inform more effective public policies? A: I think the most important lesson for public policy may be that we cannot ignore the distant past — and in the case of Haiti, by "distant past" I mean only so far back as the 18th century. (With apologies to colleagues who study the yet more distant centuries of ancient and medieval history!) Public policy has a short-term memory, however, and this is especially true of economic policy, which tends to look back only so far as the early 20th century to understand, for example, how a financial crisis comes about and what it entails.

Haiti showcases the decisive present-day impact and legacies of a history that goes back more than 300 years, to the rise of the slave plantation system. My current work tells the story of a planter rebellion in the 1720s against the French Indies Company, an event that ended the era of slave-trading monopolies in Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was known under French rule) and left large-scale sugar planters in effective control of the colony.

Some of the key political and social cleavages that have characterized Haitian life ever since date back to this period. A history of Haiti that begins with the revolutionary years leading up to Haitian independence in 1804, or any period thereafter, will necessarily lack a handle on just how deeply rooted are Haiti’s current circumstances.

We can see this on any number of levels. Colonial history continues to hamper prospects for broad-based education in Haiti, as my colleague Michel DeGraff’s work on the linguistic politics of French vs. Haitian Kreyòl powerfully demonstrates. The environment is another example. Part of the resistance to accepting the reality of climate change (whether in Haiti or elsewhere) is a reluctance to acknowledge that history in this deep sense matters. Yet it is clear that deforestation in Haiti begins no later than the 17th century, when French settlers began using trees for purposes of lumber and fuel. By the time of Haiti’s independence, the lack of forest cover had already left many parts of the country vulnerable to flooding.

That historical perspective, in turn, suggests one of the difficulties that besets even the most well-intentioned relief work in Haiti today. Such work tends to focus on repairing the immediate damage caused by the latest “natural” catastrophe, whether an earthquake, a hurricane-induced flood, or an outbreak of contagious disease. These tragedies rightly call upon the generous aid of first-responders, but after the sense of emergency passes, the eyes of the world often turn elsewhere.

An understanding of how these tragedies draw on the full weight of Haitian history encourages and even demands a longer-term commitment to the problems at hand. And it suggests that effective responses to what seem like essentially medical, environmental, or legal problems must cut across conventional categories of policy analysis and understandings of responsibility. Take the case of United Nations liability for the cholera outbreak in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

The natural impulse of human rights lawyers in that context was to file suit against the U.N., which then spent several years digging in its heels and denying its role in the outbreak. But the U.N.’s position in Haiti is a legacy of the much deeper impact that individual nations/states — most notably, France and the United States — have had on Haitian affairs over the course of three centuries. Framing responsibility in narrowly legal or chronological terms runs head-on into this reality and limits rather than expands our sense of the potential remedies.

Q: What connections do you see between economic conditions (including globalization and monetary policy) and the ability of a people or a culture to make innovations in science, technology, and public policy?

A: Waking up hungry each morning does not leave one with great deal of energy for scientific (or any other kind of) work during the day. The resources that make possible scientific and technological innovation are the same ones that sustain the relatively high standard of daily living many of us enjoy in the United States.

Haiti’s economy has long existed in a state of colonial dependency upon one or another foreign power; today it is the United States. The country’s economy is also beset by many woes, among them an ongoing currency crisis that makes the Haitian gourde an increasingly ineffective form of money. This fact places a premium on access to U.S. dollars, which elites and companies enjoy at the expense of workers paid in the local currency.

This is a crisis of sovereignty that takes the form of a monetary crisis. The earliest such currency crisis dates back (again) to the 1720s, and it’s one dimension of my current research. One of the two key triggers of the revolt against the Indies Company was a suspicion that the Company intended to eliminate the use of local Spanish silver coins, on which most colonists depended for their livelihood. The lack of a reliable and stable currency remained a problem throughout the colonial period and continues to severely constrict the economic horizons of many Haitians today.

Q: As MIT President Reif has said, solving the great challenges of our time will require multidisciplinary problem-solving — bringing together expertise and ideas from the sciences, technology, the social sciences, arts, and humanities. Can you share why you believe it is critical for any effort to address the well-being of human populations, and the planet itself, to incorporate tools and perspectives from the field of history? Also, what challenges do you see to multi-disciplinary collaborations — and how can we overcome them?

A: President Reif’s observation is correct and important. We also need to appreciate that, even within the world of the social sciences and the humanities, there are deep and abiding differences about how best to understand and implement public policy.

Let’s take the case of development economics. There is a growing literature, associated mostly with political economy and the new institutional economics, that seeks to explain the disparities in wealth and income between more and less “developed” nations. These works tend to suggest that there is a unifying model, theory, or historical pattern that accounts for the disparities: political corruption, institutional competence, the rule of law, protection of private property, etc. These phenomena are all important, but the particular forms they take can really only be understood on a case-by-case basis.

It’s important to do the unglamorous, nitty-gritty, heavily historical work of understanding the local and the particular — which requires much more patience that even those social scientists who speak of “path dependence” tend to exhibit. I believe that this kind of sustained patience for understanding the local in historical contexts is itself a tool of public policy, a way of seeing and talking about the world, and (if wielded correctly) an instrument of power and justice.

One of the principal ways historians can contribute to problem-solving work at MIT and elsewhere is by helping to identify what the real problem is in the first place. When we can understand and articulate the roots and sources of a problem, we have a much better chance of solving it.

Interview prepared by MIT SHASS Communications Editorial team: Kathryn O'Neill, Emily Hiestand (series editor)

Share this news article on:, related links.

- Malick Ghachem

- MIT History

- Online course: (21H.319) Race, Crime, and Citizenship in American Law

- Book: "The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution"

- Article: "Election Insights: Malick Ghachem on Criminal Justice Reform"

- Article: "Black Histories Matter"

Related Topics

- International development

- Education, teaching, academics

Related Articles

Analyzing the 2016 election: Insights from 12 MIT scholars

SHASS welcomes six new faculty members

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

3 Questions: Enhancing last-mile logistics with machine learning

Read full story →

Women in STEM — A celebration of excellence and curiosity

A blueprint for making quantum computers easier to program

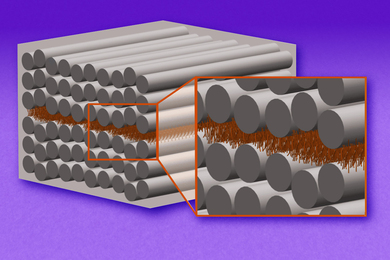

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

From neurons to learning and memory

A biomedical engineer pivots from human movement to women’s health

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

About • Fellowship • Writing • Speaking • Bibliography • Subscribe • Community • Support

Problem-solution history

History gets a bad rap. Most people find it boring—as did I, throughout all my school years, until I finally got excited about it in my mid-twenties and began catching up on my education. The problem is the way it is written and taught.

History is often presented as a collection of facts. The facts might be a jumble, or hopefully organized in an understandable sequence. I call this name-and-date history . It’s the boring history that most people associate with the subject and that most people suffer through in school. At its best, a historian can pick out the most interesting or exciting facts, and tell them in an engaging, lively manner. I call this storytime history . The material is somewhat motivated and it’s at least entertaining. But in any case the student doesn’t retain much if anything, and what little they retain is not very useful, because it isn’t connected to anything and doesn’t represent a deep understanding.

The better historians go beyond name-and-date history. They integrate facts into casual sequences to create coherent narratives. I call this cause-and-effect history. At this level the student actually has a chance of achieving real understanding. Even at this level, though, the ideas can quickly become overwhelming. At its best, cause-and-effect history simplifies, condenses and essentializes until it reaches a high level of integration. This is big-picture history , a term coined by Scott Powell (to whom I am indebted for most of the perspective just outlined). With big-picture history the student can not only understand, but retain that understanding in a usable package.

What I am trying to do in this blog is something I’m calling problem-solution history . Since I’m telling the story of human progress, I want to tell not only what happened, not only why it happened, but why we decided to make it happen . To do that, I need to clearly explain the problems humans face and how almost every aspect of the modern world is a solution to one of those problems.

Only in this context can you appreciate, protect, and defend what we have accomplished so far—and be inspired to push progress further, faster. Without this background, it’s easy to hate DDT without realizing that it was a replacement for arsenic , to despise plastic without realizing that it saved the elephants , or to be disgusted by industrial furnaces without realizing that they averted worldwide famine . It’s easy to propose doing away with modern technolgy and reverting to a seemingly halcyon past, without realizing that this means un-solving problems that those who came before us worked so hard to solve.

« Unsustainable The 13th labor of Hercules »

Get posts by email:

Copyright © Jason Crawford. Some rights reserved: CC BY-ND 4.0

Privacy policy

Get posts by email

- inspirko.org

Inspirational topics for a quality life.

Problem solving

Entertaining introduction.

Problem-solving is an essential skill that we use every day, whether we realize it or not. From fixing a broken bike to figuring out how to make a delicious meal with limited ingredients, problem-solving is at the core of our daily lives. But what exactly is problem-solving? It's the process of identifying a problem, developing a plan to solve it, and implementing that plan to reach a solution. And while it may sound straightforward, the reality is that problem-solving can be a tricky and sometimes frustrating process.

Imagine you're trying to bake a cake, but you realize you're missing an ingredient. You could throw in the towel and give up on the cake altogether, or you could think creatively and find a solution. Maybe you could substitute a similar ingredient or adjust the recipe to work without it. The ability to think critically and outside the box is essential for effective problem-solving, and it's a skill that can be developed with practice.

Problem-solving has been a part of human history for as long as we've existed. Our ancestors had to solve problems every day just to survive, from hunting for food to building shelter. Over time, we've developed more sophisticated methods of problem-solving, from the scientific method to design thinking. But even with all our technological advances, we still face new challenges that require innovative problem-solving.

In this text, we'll explore the fascinating world of problem-solving, from its history to its practical applications in everyday life. We'll also dive into the principles of effective problem-solving and debunk some common myths surrounding the topic. So buckle up and get ready to exercise your brain – because problem-solving is about to become your new favorite pastime.

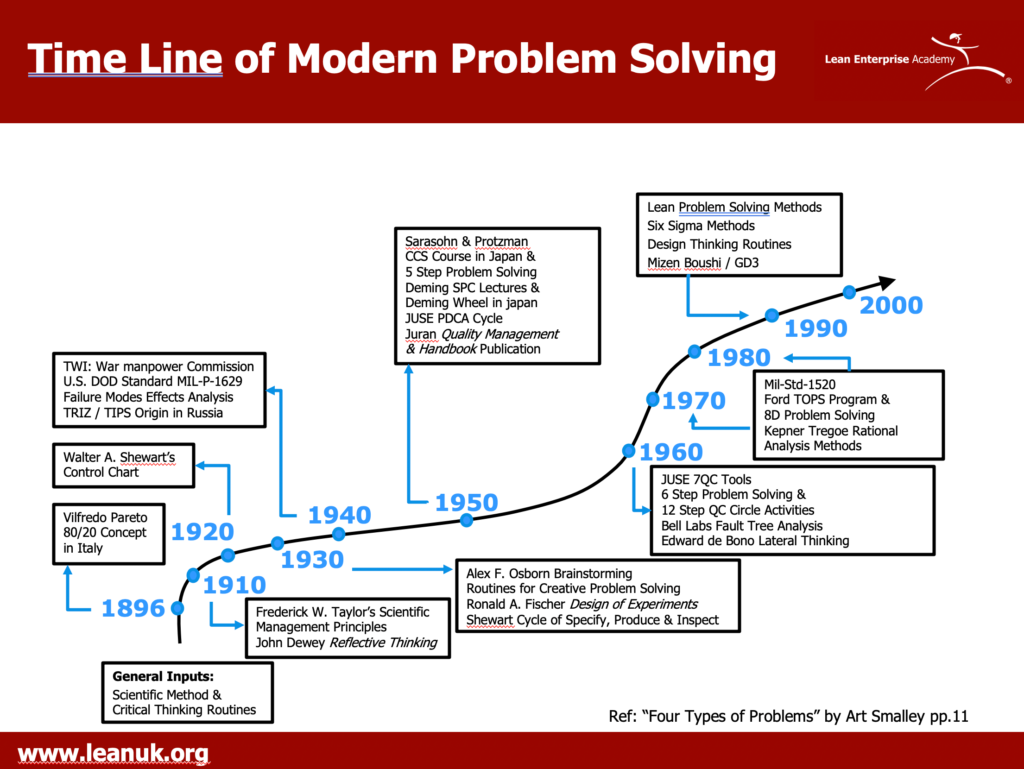

Short History

As mentioned in the previous chapter, problem-solving has been a part of human history since the beginning. Our ancestors had to solve problems every day to survive, such as finding food and water, building shelter, and protecting themselves from predators. These early humans developed practical problem-solving skills based on trial and error, and they passed their knowledge down through the generations.

As civilizations developed, problem-solving became more complex. For example, ancient civilizations like the Greeks and Romans developed advanced systems for building structures, creating art, and governing their societies. The Greeks developed a method of inquiry called dialectic, which involved questioning and answering to arrive at the truth. The Romans developed a legal system that relied on solving disputes between individuals and groups.

In the Middle Ages, problem-solving continued to be important, particularly in the fields of mathematics and science. Many of the mathematical and scientific advancements made during this time laid the foundation for modern science and engineering. In the Renaissance, problem-solving became more focused on the arts, with artists like Leonardo da Vinci using their creativity to solve complex problems in fields like engineering, anatomy, and architecture.

In the modern era, problem-solving has become even more crucial, as technology and globalization have made the world more complex and interconnected. Today, we face challenges like climate change, resource depletion, and social inequality, which require innovative problem-solving to address. Many fields, such as engineering, computer science, and business, have developed problem-solving methodologies, such as design thinking and lean startup, to help people tackle these complex challenges.

In short, problem-solving has been a fundamental part of human history and has evolved alongside the development of civilizations and societies. From our earliest ancestors to the present day, problem-solving has been essential to our survival and progress. And as we face new challenges in the future, we'll need to continue developing innovative problem-solving skills to overcome them.

Famous People

Throughout history, there have been many famous people who have made significant contributions to the field of problem-solving. These individuals have used their creativity, intelligence, and persistence to tackle some of the world's most complex problems and come up with innovative solutions. Here are just a few examples:

Thomas Edison - Edison is perhaps best known for inventing the light bulb, but he was also a prolific problem-solver who held over 1,000 patents in his lifetime. Edison famously said, "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work," reflecting his perseverance in the face of challenges.

Albert Einstein - Einstein is one of the most famous scientists in history, known for his groundbreaking work in physics. He was also an excellent problem-solver, using his intuition and mathematical skills to make revolutionary discoveries about the nature of the universe.

Steve Jobs - Jobs was the co-founder of Apple and is credited with revolutionizing the personal computer, music, and mobile phone industries. He was a master problem-solver who believed that design thinking was the key to innovation and success.

Marie Curie - Curie was a pioneering physicist and chemist who made significant contributions to the field of radioactivity. She was also an excellent problem-solver, using her analytical skills to develop new scientific theories and techniques.

Elon Musk - Musk is a modern-day problem-solving genius, known for his work with Tesla, SpaceX, and other ventures. He has a reputation for thinking big and tackling audacious goals, like colonizing Mars and creating a high-speed transportation system.

These individuals and many others have shown that effective problem-solving requires creativity, persistence, and a willingness to take risks. They have tackled some of the world's most complex problems and come up with innovative solutions that have changed the course of history. Their examples show us that problem-solving is not just a practical skill, but also a powerful tool for innovation and progress.

Shocking Facts

Problem-solving is an essential skill that we use every day, but there are some surprising and shocking facts about problem-solving that many people are not aware of. Here are a few:

Most people are terrible at problem-solving - Studies have shown that most people struggle with even simple problem-solving tasks. In fact, only about 20% of the population is considered to be proficient in problem-solving.

Problem-solving ability declines with age - As we age, our problem-solving abilities tend to decline. This is due to changes in the brain and decreased cognitive function.

Lack of sleep can impair problem-solving ability - A lack of sleep can significantly impair our ability to solve problems. Studies have shown that people who are sleep-deprived make more errors and take longer to complete tasks that require problem-solving.

Stress can hinder problem-solving - While a certain amount of stress can be beneficial for problem-solving, too much stress can actually hinder our ability to think creatively and come up with solutions.

Our problem-solving ability is affected by our mindset - Our mindset can play a significant role in our ability to solve problems. People with a growth mindset, who believe that their abilities can be developed through hard work and perseverance, tend to be better problem-solvers than those with a fixed mindset, who believe that their abilities are predetermined and unchangeable.

These shocking facts highlight the importance of developing effective problem-solving skills and taking care of our mental and physical health to optimize our problem-solving ability. By understanding these factors, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Secrets of the Topic

While problem-solving may seem straightforward, there are some secrets to effective problem-solving that can help us achieve better results. Here are a few:

Break the problem down into smaller parts - When faced with a complex problem, it can be helpful to break it down into smaller, more manageable parts. This can help us better understand the problem and come up with more targeted solutions.

Use analogies and metaphors - Using analogies and metaphors can help us approach problems from a fresh perspective and generate new ideas. By comparing the problem to something else, we can often identify similarities and differences that we may not have otherwise noticed.

Ask the right questions - Asking the right questions is essential for effective problem-solving. By asking open-ended questions, we can encourage creative thinking and generate new ideas. It's also important to ask questions that help us better understand the problem and its underlying causes.

Use trial and error - While trial and error may not be the most efficient problem-solving method, it can be effective for complex problems with multiple solutions. By trying different approaches and learning from our mistakes, we can ultimately arrive at a solution that works.

Collaborate with others - Collaboration can be a powerful tool for problem-solving. By working with others, we can draw on their expertise and perspectives, and generate more creative solutions. It's important to cultivate a culture of collaboration and open communication to make the most of this approach.

By understanding these secrets of effective problem-solving, we can improve our ability to solve complex problems and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Effective problem-solving requires a set of principles to guide our approach. These principles are based on research and experience, and can help us approach problems in a structured and effective way. Here are a few key principles of effective problem-solving:

Define the problem - Before we can solve a problem, we need to define it clearly. This involves identifying the underlying issue, understanding its scope and impact, and clarifying our goals and objectives.

Generate multiple solutions - Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, rather than just one. This allows us to consider a range of options and choose the best one.

Evaluate the solutions - Once we have generated multiple solutions, we need to evaluate them based on a set of criteria, such as feasibility, impact, and cost. This helps us choose the best solution for the problem at hand.

Implement the solution - Once we have selected a solution, we need to implement it effectively. This may involve developing a plan, allocating resources, and communicating the solution to stakeholders.

Monitor and adjust - Effective problem-solving requires ongoing monitoring and adjustment. We need to track the progress of the solution, identify any issues or challenges that arise, and make adjustments as necessary.

By following these principles, we can approach problems in a structured and effective way, and achieve better results. These principles are applicable to a range of fields, from business and engineering to education and healthcare. By applying them consistently, we can develop our problem-solving skills and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Using the Topic to Improve Everyday Life

Effective problem-solving is not just about solving complex business or technical problems. It can also be used to improve our everyday lives. Here are some ways in which we can use problem-solving to improve our daily experiences:

Time management - Many of us struggle with managing our time effectively. By using problem-solving techniques, we can identify the root causes of our time management issues and develop effective strategies to address them.

Personal relationships - Relationships can be complex, and we often encounter problems that require creative solutions. By using problem-solving techniques, we can communicate more effectively, resolve conflicts, and strengthen our relationships.

Health and wellness - Many health and wellness issues, such as weight management and stress reduction, require effective problem-solving skills. By breaking down the problem into smaller parts and developing targeted solutions, we can improve our overall health and well-being.

Financial management - Financial management can be a challenge for many people. By using problem-solving techniques, we can identify areas where we can reduce expenses or increase income, and develop effective strategies to achieve our financial goals.

Personal growth - Effective problem-solving can also be used to facilitate personal growth and development. By identifying our strengths and weaknesses, setting goals, and developing action plans, we can achieve our full potential and live a more fulfilling life.

By applying problem-solving principles to our everyday lives, we can improve our overall quality of life and achieve greater success in all areas. Effective problem-solving is a versatile and valuable skill that can be used in virtually any context to achieve better results.

Practical Uses

Effective problem-solving has practical uses in a range of fields, from business to healthcare to education. Here are a few practical uses of problem-solving:

Business - Problem-solving is essential in the business world, where companies face complex challenges like market competition, changing customer needs, and financial constraints. Business leaders use problem-solving techniques to identify problems, generate solutions, and implement changes that improve performance and profitability.

Healthcare - Problem-solving is essential in healthcare, where medical professionals face complex diagnoses, treatment plans, and patient care issues. Healthcare professionals use problem-solving techniques to identify the underlying causes of health problems, develop effective treatment plans, and improve patient outcomes.

Education - Problem-solving is essential in education, where teachers and students face a range of challenges, from student engagement to curriculum design. Teachers use problem-solving techniques to identify areas where students are struggling, develop effective teaching strategies, and improve student performance.

Engineering - Problem-solving is essential in engineering, where engineers face complex design challenges, from building structures to developing new technologies. Engineers use problem-solving techniques to identify design issues, develop innovative solutions, and test and implement those solutions in real-world contexts.

Government - Problem-solving is essential in government, where policymakers face complex social and economic challenges, from reducing poverty to improving infrastructure. Government officials use problem-solving techniques to identify underlying issues, develop effective policies, and implement changes that improve outcomes for citizens.

These are just a few examples of the practical uses of problem-solving. Effective problem-solving is essential in virtually every field, and can be used to improve performance, productivity, and outcomes in a range of contexts.

Recommendations

Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience. Here are a few recommendations for improving your problem-solving abilities:

Develop your critical thinking skills - Critical thinking is an essential component of effective problem-solving. By developing your critical thinking skills, you can identify underlying issues, evaluate potential solutions, and make informed decisions.

Practice creative thinking - Creative thinking is essential for generating innovative solutions to complex problems. By practicing creative thinking techniques, such as brainstorming, mind mapping, and analogical thinking, you can develop your ability to think outside the box.

Build your knowledge base - Effective problem-solving requires a strong foundation of knowledge in the relevant field. By building your knowledge base through education, research, and practical experience, you can become more effective at identifying and solving problems.

Collaborate with others - Collaboration is a powerful tool for problem-solving. By working with others, you can draw on their expertise and perspectives, generate new ideas, and achieve better results.

Practice problem-solving in different contexts - Effective problem-solving requires adaptability and versatility. By practicing problem-solving in different contexts, you can develop your ability to apply problem-solving principles in a range of situations.

By following these recommendations, you can improve your problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in your personal and professional life. Effective problem-solving is a valuable skill that can help you overcome challenges, achieve your goals, and make a positive impact on the world.

Effective problem-solving has many advantages, both personal and professional. Here are a few:

Improved decision-making - Effective problem-solving involves evaluating potential solutions and making informed decisions based on evidence and analysis. By developing your problem-solving abilities, you can become a better decision-maker in all areas of your life.

Increased efficiency - Effective problem-solving involves identifying and addressing underlying issues, which can lead to increased efficiency in personal and professional contexts. By addressing problems before they become larger issues, you can save time, resources, and energy.

Increased innovation - Effective problem-solving requires creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, which can lead to increased innovation in personal and professional contexts. By generating new ideas and approaches, you can improve your performance and achieve better results.

Improved teamwork - Effective problem-solving often requires collaboration and communication, which can lead to improved teamwork in personal and professional contexts. By working with others to identify and solve problems, you can develop stronger relationships and achieve better outcomes.

Improved self-confidence - Effective problem-solving requires persistence, resilience, and the ability to overcome obstacles. By developing your problem-solving abilities, you can improve your self-confidence and achieve greater success in all areas of your life.

These advantages highlight the importance of developing effective problem-solving skills. By becoming a better problem-solver, you can achieve better outcomes, overcome challenges, and make a positive impact on the world around you.

Disadvantages

While effective problem-solving has many advantages, there are also some potential disadvantages to consider. Here are a few:

Overthinking - Effective problem-solving involves analysis and evaluation, but too much of this can lead to overthinking. Overthinking can cause stress and anxiety, and can also lead to indecision and procrastination.

Analysis paralysis - Analysis paralysis is a type of overthinking that occurs when we become stuck in the analysis phase of problem-solving and struggle to make a decision or take action. This can lead to missed opportunities and wasted time.

Lack of creativity - Effective problem-solving requires creativity and innovative thinking, but some individuals may struggle with this aspect of problem-solving. A lack of creativity can lead to a limited range of solutions and missed opportunities for improvement.

Resistance to change - Effective problem-solving often requires change, which can be difficult for some individuals to accept. Resistance to change can limit the effectiveness of problem-solving efforts and lead to missed opportunities for improvement.

Resource constraints - Effective problem-solving often requires resources, such as time, money, and personnel. Resource constraints can limit the effectiveness of problem-solving efforts and lead to suboptimal solutions.

These disadvantages highlight the importance of being mindful of the potential downsides of problem-solving and taking steps to mitigate them. By balancing analysis and creativity, being open to change, and being mindful of resource constraints, we can overcome these potential disadvantages and achieve greater success in our problem-solving efforts.

Possibilities of Misunderstanding the Topic

While problem-solving may seem straightforward, there are some common misunderstandings that can lead to ineffective problem-solving. Here are a few possibilities of misunderstanding the topic:

Assuming there is only one solution - Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, rather than assuming there is only one correct answer. By considering a range of options, we can identify the best solution for the problem at hand.

Focusing on symptoms rather than underlying causes - Effective problem-solving requires us to identify the underlying causes of a problem, rather than just addressing the symptoms. By addressing the root cause of a problem, we can develop more targeted and effective solutions.

Ignoring potential biases - Effective problem-solving requires us to be aware of our biases and assumptions, which can influence our thinking and decision-making. By recognizing and addressing these biases, we can improve the quality of our problem-solving efforts.

Assuming a linear problem-solving process - Effective problem-solving is not always a linear process, and can involve a range of approaches, from trial and error to creative thinking. By being flexible and adaptive, we can achieve better results in our problem-solving efforts.

Overlooking the importance of implementation and monitoring - Effective problem-solving is not just about generating solutions, but also about implementing them effectively and monitoring their success. By tracking progress and making adjustments as necessary, we can ensure that our problem-solving efforts are effective and sustainable.

By understanding these possibilities of misunderstanding the topic, we can approach problem-solving in a more effective and nuanced way, and achieve better results. Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience, and by being mindful of these potential misunderstandings, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Controversy

While problem-solving is generally seen as a positive and necessary skill, there are some controversies surrounding its use in certain contexts. Here are a few examples:

In some industries, there is a focus on rapid problem-solving that may prioritize speed over accuracy. This can lead to rushed solutions that may not be effective in the long term.

Some people argue that problem-solving can be overused, and that individuals may rely too heavily on problem-solving techniques rather than using intuition or common sense.

There is debate over whether problem-solving is a skill that can be taught or if it is an innate ability. Some people argue that problem-solving is a learned skill that can be developed through practice, while others argue that some people are naturally better problem-solvers than others.

In some cases, problem-solving can be a source of stress or burnout, particularly in high-pressure environments where there is a constant need to identify and solve problems.

There is debate over the role of problem-solving in decision-making, and whether problem-solving should be the primary approach to decision-making or whether other approaches, such as intuition, should also be considered.

These controversies highlight the complexity and nuance of problem-solving as a skill. While problem-solving is generally seen as a positive and necessary skill, there are potential downsides and debates over its use in certain contexts. By being aware of these controversies, we can approach problem-solving in a more nuanced and informed way, and achieve better results.

Debunking Myths

There are some common myths surrounding problem-solving that can lead to ineffective or inefficient problem-solving efforts. Here are a few of these myths, and why they are not accurate:

Myth: There is only one correct solution to a problem. Reality: Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, and evaluating them based on a set of criteria to choose the best option.

Myth: Problem-solving is a linear process that always follows the same steps. Reality: Problem-solving can involve a range of approaches, from trial and error to creative thinking, and may require adaptation and flexibility based on the specific context and problem.

Myth: Effective problem-solving requires a high IQ or advanced education. Reality: While knowledge and experience can be helpful in effective problem-solving, problem-solving is a skill that can be developed through practice and effort.

Myth: Problem-solving always involves complex, technical problems. Reality: Problem-solving can be applied to a range of issues and challenges, from personal relationships to time management.

Myth: Problem-solving requires perfectionism and an aversion to risk-taking. Reality: Effective problem-solving involves taking calculated risks and being willing to make mistakes and learn from them.

By debunking these myths, we can approach problem-solving in a more effective and realistic way, and achieve better results. Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience, and by recognizing these common myths, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Other Points of Interest on This Topic

Effective problem-solving is a broad and multifaceted topic with many points of interest. Here are a few additional points of interest on this topic:

The role of emotional intelligence in effective problem-solving. Emotional intelligence, which involves the ability to recognize and manage emotions in oneself and others, can be an important factor in effective problem-solving.

The impact of culture on problem-solving approaches. Different cultures may have different problem-solving approaches, and understanding these differences can be important for effective problem-solving in a global context.

The role of technology in problem-solving. Technology, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, is increasingly being used to enhance problem-solving abilities and improve outcomes.

The relationship between problem-solving and innovation. Effective problem-solving is often a key component of innovation, and innovation can lead to improved problem-solving approaches and outcomes.

The importance of ethical considerations in problem-solving. Effective problem-solving requires consideration of ethical implications and potential consequences, and ethical decision-making should be a key consideration in problem-solving efforts.

These points of interest highlight the complexity and richness of effective problem-solving as a topic. By exploring these additional areas of interest, we can develop a deeper understanding of problem-solving and improve our abilities to solve problems in a range of contexts.

Subsections of This Topic

Effective problem-solving is a vast topic that encompasses many different subtopics and approaches. Here are a few examples of the different subsections of problem-solving:

Root cause analysis - Root cause analysis is a problem-solving approach that involves identifying the underlying cause of a problem and addressing it directly, rather than just treating the symptoms.

Creative thinking - Creative thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves generating new and innovative solutions to a problem, often through techniques like brainstorming and analogical thinking.

Design thinking - Design thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves a human-centered, iterative process of problem-solving that emphasizes empathy, collaboration, and experimentation.

Lean problem-solving - Lean problem-solving is a problem-solving approach that involves eliminating waste and inefficiencies in a process or system, often through the use of tools like the Kaizen method.

Six Sigma - Six Sigma is a problem-solving approach that involves using data and statistical analysis to identify and eliminate defects and improve performance.

By understanding these different subsections of problem-solving, we can develop a more nuanced and effective approach to problem-solving in a range of contexts. Each subsection offers a unique set of tools and approaches that can be used to identify and solve problems more effectively and efficiently.

Effective problem-solving is an essential skill for success in both personal and professional contexts. By developing our problem-solving abilities, we can overcome challenges, achieve our goals, and make a positive impact on the world around us.

Throughout this article, we have explored various aspects of effective problem-solving, including its history, famous problem-solvers, principles, advantages, and disadvantages. We have also discussed some of the myths and controversies surrounding problem-solving, as well as some of the different subsections of the topic.

Ultimately, effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience. By developing our critical and creative thinking skills, building our knowledge base, collaborating with others, and practicing problem-solving in different contexts, we can become more effective problem-solvers and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Effective problem-solving is not always easy, and there may be challenges and setbacks along the way. But by being mindful of the potential misunderstandings, controversies, and downsides of problem-solving, we can approach this important skill in a more nuanced and effective way, and achieve better outcomes.

In conclusion, effective problem-solving is a skill that can be developed and honed with practice and effort. By being mindful of the various aspects of problem-solving and continuously working to improve our abilities, we can become more effective problem-solvers and achieve greater success in all areas of our lives.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

This supplement elaborates on the history of the articulation, promotion and adoption of critical thinking as an educational goal.

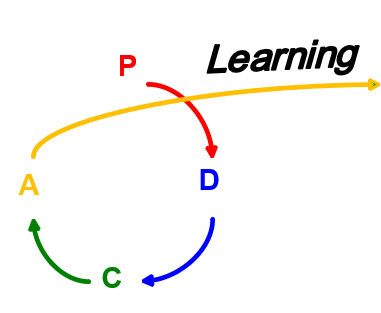

John Dewey (1910: 74, 82) introduced the term ‘critical thinking’ as the name of an educational goal, which he identified with a scientific attitude of mind. More commonly, he called the goal ‘reflective thought’, ‘reflective thinking’, ‘reflection’, or just ‘thought’ or ‘thinking’. He describes his book as written for two purposes. The first was to help people to appreciate the kinship of children’s native curiosity, fertile imagination and love of experimental inquiry to the scientific attitude. The second was to help people to consider how recognizing this kinship in educational practice “would make for individual happiness and the reduction of social waste” (iii). He notes that the ideas in the book obtained concreteness in the Laboratory School in Chicago.

Dewey’s ideas were put into practice by some of the schools that participated in the Eight-Year Study in the 1930s sponsored by the Progressive Education Association in the United States. For this study, 300 colleges agreed to consider for admission graduates of 30 selected secondary schools or school systems from around the country who experimented with the content and methods of teaching, even if the graduates had not completed the then-prescribed secondary school curriculum. One purpose of the study was to discover through exploration and experimentation how secondary schools in the United States could serve youth more effectively (Aikin 1942). Each experimental school was free to change the curriculum as it saw fit, but the schools agreed that teaching methods and the life of the school should conform to the idea (previously advocated by Dewey) that people develop through doing things that are meaningful to them, and that the main purpose of the secondary school was to lead young people to understand, appreciate and live the democratic way of life characteristic of the United States (Aikin 1942: 17–18). In particular, school officials believed that young people in a democracy should develop the habit of reflective thinking and skill in solving problems (Aikin 1942: 81). Students’ work in the classroom thus consisted more often of a problem to be solved than a lesson to be learned. Especially in mathematics and science, the schools made a point of giving students experience in clear, logical thinking as they solved problems. The report of one experimental school, the University School of Ohio State University, articulated this goal of improving students’ thinking:

Critical or reflective thinking originates with the sensing of a problem. It is a quality of thought operating in an effort to solve the problem and to reach a tentative conclusion which is supported by all available data. It is really a process of problem solving requiring the use of creative insight, intellectual honesty, and sound judgment. It is the basis of the method of scientific inquiry. The success of democracy depends to a large extent on the disposition and ability of citizens to think critically and reflectively about the problems which must of necessity confront them, and to improve the quality of their thinking is one of the major goals of education. (Commission on the Relation of School and College of the Progressive Education Association 1943: 745–746)

The Eight-Year Study had an evaluation staff, which developed, in consultation with the schools, tests to measure aspects of student progress that fell outside the focus of the traditional curriculum. The evaluation staff classified many of the schools’ stated objectives under the generic heading “clear thinking” or “critical thinking” (Smith, Tyler, & Evaluation Staff 1942: 35–36). To develop tests of achievement of this broad goal, they distinguished five overlapping aspects of it: ability to interpret data, abilities associated with an understanding of the nature of proof, and the abilities to apply principles of science, of social studies and of logical reasoning. The Eight-Year Study also had a college staff, directed by a committee of college administrators, whose task was to determine how well the experimental schools had prepared their graduates for college. The college staff compared the performance of 1,475 college students from the experimental schools with an equal number of graduates from conventional schools, matched in pairs by sex, age, race, scholastic aptitude scores, home and community background, interests, and probable future. They concluded that, on 18 measures of student success, the graduates of the experimental schools did a somewhat better job than the comparison group. The graduates from the six most traditional of the experimental schools showed no large or consistent differences. The graduates from the six most experimental schools, on the other hand, had much greater differences in their favour. The graduates of the two most experimental schools, the college staff reported:

… surpassed their comparison groups by wide margins in academic achievement, intellectual curiosity, scientific approach to problems, and interest in contemporary affairs. The differences in their favor were even greater in general resourcefulness, in enjoyment of reading, [in] participation in the arts, in winning non-academic honors, and in all aspects of college life except possibly participation in sports and social activities. (Aikin 1942: 114)

One of these schools was a private school with students from privileged families and the other the experimental section of a public school with students from non-privileged families. The college staff reported that the graduates of the two schools were indistinguishable from each other in terms of college success.

In 1933 Dewey issued an extensively rewritten edition of his How We Think (Dewey 1910), with the sub-title “A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process”. Although the restatement retains the basic structure and content of the original book, Dewey made a number of changes. He rewrote and simplified his logical analysis of the process of reflection, made his ideas clearer and more definite, replaced the terms ‘induction’ and ‘deduction’ by the phrases ‘control of data and evidence’ and ‘control of reasoning and concepts’, added more illustrations, rearranged chapters, and revised the parts on teaching to reflect changes in schools since 1910. In particular, he objected to one-sided practices of some “experimental” and “progressive” schools that allowed children freedom but gave them no guidance, citing as objectionable practices novelty and variety for their own sake, experiences and activities with real materials but of no educational significance, treating random and disconnected activity as if it were an experiment, failure to summarize net accomplishment at the end of an inquiry, non-educative projects, and treatment of the teacher as a negligible factor rather than as “the intellectual leader of a social group” (Dewey 1933: 273). Without explaining his reasons, Dewey eliminated the previous edition’s uses of the words ‘critical’ and ‘uncritical’, thus settling firmly on ‘reflection’ or ‘reflective thinking’ as the preferred term for his subject-matter. In the revised edition, the word ‘critical’ occurs only once, where Dewey writes that “a person may not be sufficiently critical about the ideas that occur to him” (1933: 16, italics in original); being critical is thus a component of reflection, not the whole of it. In contrast, the Eight-Year Study by the Progressive Education Association treated ‘critical thinking’ and ‘reflective thinking’ as synonyms.

In the same period, Dewey collaborated on a history of the Laboratory School in Chicago with two former teachers from the school (Mayhew & Edwards 1936). The history describes the school’s curriculum and organization, activities aimed at developing skills, parents’ involvement, and the habits of mind that the children acquired. A concluding chapter evaluates the school’s achievements, counting as a success its staging of the curriculum to correspond to the natural development of the growing child. In two appendices, the authors describe the evolution of Dewey’s principles of education and Dewey himself describes the theory of the Chicago experiment (Dewey 1936).

Glaser (1941) reports in his doctoral dissertation the method and results of an experiment in the development of critical thinking conducted in the fall of 1938. He defines critical thinking as Dewey defined reflective thinking:

Critical thinking calls for a persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends. (Glaser 1941: 6; cf. Dewey 1910: 6; Dewey 1933: 9)

In the experiment, eight lesson units directed at improving critical thinking abilities were taught to four grade 12 high school classes, with pre-test and post-test of the students using the Otis Quick-Scoring Mental Ability Test and the Watson-Glaser Tests of Critical Thinking (developed in collaboration with Glaser’s dissertation sponsor, Goodwin Watson). The average gain in scores on these tests was greater to a statistically significant degree among the students who received the lessons in critical thinking than among the students in a control group of four grade 12 high school classes taking the usual curriculum in English. Glaser concludes:

The aspect of critical thinking which appears most susceptible to general improvement is the attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one’s experience. An attitude of wanting evidence for beliefs is more subject to general transfer. Development of skill in applying the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning, however, appears to be specifically related to, and in fact limited by, the acquisition of pertinent knowledge and facts concerning the problem or subject matter toward which the thinking is to be directed. (Glaser 1941: 175)

Retest scores and observable behaviour indicated that students in the intervention group retained their growth in ability to think critically for at least six months after the special instruction.

In 1948 a group of U.S. college examiners decided to develop taxonomies of educational objectives with a common vocabulary that they could use for communicating with each other about test items. The first of these taxonomies, for the cognitive domain, appeared in 1956 (Bloom et al. 1956), and included critical thinking objectives. It has become known as Bloom’s taxonomy. A second taxonomy, for the affective domain (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia 1964), and a third taxonomy, for the psychomotor domain (Simpson 1966–67), appeared later. Each of the taxonomies is hierarchical, with achievement of a higher educational objective alleged to require achievement of corresponding lower educational objectives.

Bloom’s taxonomy has six major categories. From lowest to highest, they are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Within each category, there are sub-categories, also arranged hierarchically from the educationally prior to the educationally posterior. The lowest category, though called ‘knowledge’, is confined to objectives of remembering information and being able to recall or recognize it, without much transformation beyond organizing it (Bloom et al. 1956: 28–29). The five higher categories are collectively termed “intellectual abilities and skills” (Bloom et al. 1956: 204). The term is simply another name for critical thinking abilities and skills:

Although information or knowledge is recognized as an important outcome of education, very few teachers would be satisfied to regard this as the primary or the sole outcome of instruction. What is needed is some evidence that the students can do something with their knowledge, that is, that they can apply the information to new situations and problems. It is also expected that students will acquire generalized techniques for dealing with new problems and new materials. Thus, it is expected that when the student encounters a new problem or situation, he will select an appropriate technique for attacking it and will bring to bear the necessary information, both facts and principles. This has been labeled “critical thinking” by some, “reflective thinking” by Dewey and others, and “problem solving” by still others. In the taxonomy, we have used the term “intellectual abilities and skills”. (Bloom et al. 1956: 38)

Comprehension and application objectives, as their names imply, involve understanding and applying information. Critical thinking abilities and skills show up in the three highest categories of analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The condensed version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom et al. 1956: 201–207) gives the following examples of objectives at these levels:

- analysis objectives : ability to recognize unstated assumptions, ability to check the consistency of hypotheses with given information and assumptions, ability to recognize the general techniques used in advertising, propaganda and other persuasive materials

- synthesis objectives : organizing ideas and statements in writing, ability to propose ways of testing a hypothesis, ability to formulate and modify hypotheses

- evaluation objectives : ability to indicate logical fallacies, comparison of major theories about particular cultures

The analysis, synthesis and evaluation objectives in Bloom’s taxonomy collectively came to be called the “higher-order thinking skills” (Tankersley 2005: chap. 5). Although the analysis-synthesis-evaluation sequence mimics phases in Dewey’s (1933) logical analysis of the reflective thinking process, it has not generally been adopted as a model of a critical thinking process. While commending the inspirational value of its ratio of five categories of thinking objectives to one category of recall objectives, Ennis (1981b) points out that the categories lack criteria applicable across topics and domains. For example, analysis in chemistry is so different from analysis in literature that there is not much point in teaching analysis as a general type of thinking. Further, the postulated hierarchy seems questionable at the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. For example, ability to indicate logical fallacies hardly seems more complex than the ability to organize statements and ideas in writing.

A revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson et al. 2001) distinguishes the intended cognitive process in an educational objective (such as being able to recall, to compare or to check) from the objective’s informational content (“knowledge”), which may be factual, conceptual, procedural, or metacognitive. The result is a so-called “Taxonomy Table” with four rows for the kinds of informational content and six columns for the six main types of cognitive process. The authors name the types of cognitive process by verbs, to indicate their status as mental activities. They change the name of the ‘comprehension’ category to ‘understand’ and of the ‘synthesis’ category to ’create’, and switch the order of synthesis and evaluation. The result is a list of six main types of cognitive process aimed at by teachers: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. The authors retain the idea of a hierarchy of increasing complexity, but acknowledge some overlap, for example between understanding and applying. And they retain the idea that critical thinking and problem solving cut across the more complex cognitive processes. The terms ‘critical thinking’ and ‘problem solving’, they write:

are widely used and tend to become touchstones of curriculum emphasis. Both generally include a variety of activities that might be classified in disparate cells of the Taxonomy Table. That is, in any given instance, objectives that involve problem solving and critical thinking most likely call for cognitive processes in several categories on the process dimension. For example, to think critically about an issue probably involves some Conceptual knowledge to Analyze the issue. Then, one can Evaluate different perspectives in terms of the criteria and, perhaps, Create a novel, yet defensible perspective on this issue. (Anderson et al. 2001: 269–270; italics in original)

In the revised taxonomy, only a few sub-categories, such as inferring, have enough commonality to be treated as a distinct critical thinking ability that could be taught and assessed as a general ability.

A landmark contribution to philosophical scholarship on the concept of critical thinking was a 1962 article in the Harvard Educational Review by Robert H. Ennis, with the title “A concept of critical thinking: A proposed basis for research in the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability” (Ennis 1962). Ennis took as his starting-point a conception of critical thinking put forward by B. Othanel Smith:

We shall consider thinking in terms of the operations involved in the examination of statements which we, or others, may believe. A speaker declares, for example, that “Freedom means that the decisions in America’s productive effort are made not in the minds of a bureaucracy but in the free market”. Now if we set about to find out what this statement means and to determine whether to accept or reject it, we would be engaged in thinking which, for lack of a better term, we shall call critical thinking. If one wishes to say that this is only a form of problem-solving in which the purpose is to decide whether or not what is said is dependable, we shall not object. But for our purposes we choose to call it critical thinking. (Smith 1953: 130)

Adding a normative component to this conception, Ennis defined critical thinking as “the correct assessing of statements” (Ennis 1962: 83). On the basis of this definition, he distinguished 12 “aspects” of critical thinking corresponding to types or aspects of statements, such as judging whether an observation statement is reliable and grasping the meaning of a statement. He noted that he did not include judging value statements. Cutting across the 12 aspects, he distinguished three dimensions of critical thinking: logical (judging relationships between meanings of words and statements), criterial (knowledge of the criteria for judging statements), and pragmatic (the impression of the background purpose). For each aspect, Ennis described the applicable dimensions, including criteria. He proposed the resulting construct as a basis for developing specifications for critical thinking tests and for research on instructional methods and levels.

In the 1970s and 1980s there was an upsurge of attention to the development of thinking skills. The annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Educational Reform has attracted since its start in 1980 tens of thousands of educators from all levels. In 1983 the College Entrance Examination Board proclaimed reasoning as one of six basic academic competencies needed by college students (College Board 1983). Departments of education in the United States and around the world began to include thinking objectives in their curriculum guidelines for school subjects. For example, Ontario’s social sciences and humanities curriculum guideline for secondary schools requires “the use of critical and creative thinking skills and/or processes” as a goal of instruction and assessment in each subject and course (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 30). The document describes critical thinking as follows:

Critical thinking is the process of thinking about ideas or situations in order to understand them fully, identify their implications, make a judgement, and/or guide decision making. Critical thinking includes skills such as questioning, predicting, analysing, synthesizing, examining opinions, identifying values and issues, detecting bias, and distinguishing between alternatives. Students who are taught these skills become critical thinkers who can move beyond superficial conclusions to a deeper understanding of the issues they are examining. They are able to engage in an inquiry process in which they explore complex and multifaceted issues, and questions for which there may be no clear-cut answers (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 46).

Sweden makes schools responsible for ensuring that each pupil who completes compulsory school “can make use of critical thinking and independently formulate standpoints based on knowledge and ethical considerations” (Skolverket 2018: 12). Subject syllabi incorporate this requirement, and items testing critical thinking skills appear on national tests that are a required step toward university admission. For example, the core content of biology, physics and chemistry in years 7-9 includes critical examination of sources of information and arguments encountered by pupils in different sources and social discussions related to these sciences, in both digital and other media. (Skolverket 2018: 170, 181, 192). Correspondingly, in year 9 the national tests require using knowledge of biology, physics or chemistry “to investigate information, communicate and come to a decision on issues concerning health, energy, technology, the environment, use of natural resources and ecological sustainability” (see the message from the School Board ). Other jurisdictions similarly embed critical thinking objectives in curriculum guidelines.

At the college level, a new wave of introductory logic textbooks, pioneered by Kahane (1971), applied the tools of logic to contemporary social and political issues. Popular contemporary textbooks of this sort include those by Bailin and Battersby (2016b), Boardman, Cavender and Kahane (2018), Browne and Keeley (2018), Groarke and Tindale (2012), and Moore and Parker (2020). In their wake, colleges and universities in North America transformed their introductory logic course into a general education service course with a title like ‘critical thinking’ or ‘reasoning’. In 1980, the trustees of California’s state university and colleges approved as a general education requirement a course in critical thinking, described as follows:

Instruction in critical thinking is to be designed to achieve an understanding of the relationship of language to logic, which should lead to the ability to analyze, criticize, and advocate ideas, to reason inductively and deductively, and to reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief. The minimal competence to be expected at the successful conclusion of instruction in critical thinking should be the ability to distinguish fact from judgment, belief from knowledge, and skills in elementary inductive and deductive processes, including an understanding of the formal and informal fallacies of language and thought. (Dumke 1980)

Since December 1983, the Association for Informal Logic and Critical Thinking has sponsored sessions at the three annual divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association. In December 1987, the Committee on Pre-College Philosophy of the American Philosophical Association invited Peter Facione to make a systematic inquiry into the current state of critical thinking and critical thinking assessment. Facione assembled a group of 46 other academic philosophers and psychologists to participate in a multi-round Delphi process, whose product was entitled Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction (Facione 1990a). The statement listed abilities and dispositions that should be the goals of a lower-level undergraduate course in critical thinking. Researchers in nine European countries determined which of these skills and dispositions employers expect of university graduates (Dominguez 2018 a), compared those expectations to critical thinking educational practices in post-secondary educational institutions (Dominguez 2018b), developed a course on critical thinking education for university teachers (Dominguez 2018c) and proposed in response to identified gaps between expectations and practices an “educational protocol” that post-secondary educational institutions in Europe could use to develop critical thinking (Elen et al. 2019).

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

- Our Mission

Defining Authenticity in Historical Problem Solving

At Sammamish High School, we've identified seven key elements of problem-based learning, an approach that drives our comprehensive curriculum. I teach tenth grade history, which puts me in a unique position to describe the key element of authentic problems.

What is an authentic problem in world history? My colleagues and I grappled with this question when we set about to design a problem-based learning (PBL) class for AP World History. We looked enviously at some of our peer disciplines such as biology which we imagined having clear problems for students to work on (they didn't, but that is another blog post).

We consulted a number of sources in research. What did the College Board say? What do the state standards say? We reached out to Walter Parker, the social studies methods instructor at the University of Washington School of Education, to help us clarify our thinking.

We arrived at two ways to think about authentic problems. One I will call the work of historians in the field, and the other was the work of historical actors at the time. We quickly felt a healthy tension between these two ideas.

Living the Decisions

The work of historians involves creating and debating the frameworks for the historical narratives our students use to interpret history. One problem that historians debate is the question of periodization, or how history should be divided chronologically in order to better understand it. We know these chunks of time -- or eras -- by the more familiar labels given them by historians: classical, medieval and modern, to name a few. These debates are highly charged because they are so important in defining what students entering the field should study. For example, should World War I be considered a turning point in world history, or is World War I really a European civil war whose significance as a global turning point diminishes with passing of each decade?

It was exciting to consider that our students would engage in such high-level and rigorous academic thinking. We could think of many meaty questions for them to explore and discuss: What was the legacy of Mongol rule? Is the modern era a time of progress? Even the question, "Is there really such a thing as world history?" However, we wondered, was it realistic to ask students to do the work of historians? Could we prepare them well enough to have these highly abstract but critical conversations? College professors spend years steeping themselves exclusively in their discipline, while our students devote one seventh of their class time to world history. My colleague and I had both engaged students in such debates during our practice, but not in an integrated systematic way.

Our approach to authentic problems came from a different perspective: that of the historical actor and decision-makers. By giving students roles based around a historical problem we could ask them, "What would you do, and why?" This, of course, is nothing new. Teachers have been creating simulations and role-plays to engage their students for generations. We wanted to build a unit or "challenge cycle" around these activities.

Ultimately, we decided that it would be difficult for students to do the work of historians if they had not done the work of historical actors. By "living" the decisions through problem-based simulations, our students would collectively be better prepared to engage in the larger questions that are debated in the discipline of history.

Challenge Cycles

What did this look like in World History? We created challenge cycles based on each of the eras into which the course was divided. Our first attempt at building a PBL challenge cycle took place when we studied the Early Modern Era (1450-1750) and focused on the theme of diplomacy. Students were assigned to empire teams based on their interests, and they played the role of foreign policy advisors. Their mission: to determine how diplomacy could help their empire maintain and expand power. The simulation component culminated in a round of treaty negotiations between empires. We found that while students were energized and came to know their roles deeply, they were not directly engaging in the conversations and debates that historians have.

After we piloted our first PBL units, we built in a day for a debrief discussion explicitly linking the challenge cycle with the authentic questions that historians address. This debrief day also allowed students to drop their simulation roles, which frequently put them in competitive or modestly adversarial relationships with one another. They were free to argue against the position their historical figure would have taken. For example, during our diplomacy challenge debrief, the Ottoman Empire could argue the position of their Spanish archrivals. We also broke down our challenge cycle into components that allowed students to deepen their understanding of their historical actors in relation to others. In our diplomacy challenge, this meant building in a diplomatic reception in which our student diplomats had to toast an empire with which they wanted to engage in trade.

Diplomats and Historians

What kind of comments have we heard from students? Their response has become more positive as we have refined our pilot units. Here is a brief sample from a survey we took on our diplomacy challenge unit:

- "We all were sort of competing, which made us try harder."

- "The reception was super neat."

- "I really enjoyed knowing about my empire, therefore I wanted to learn more about that empire and master it . . . I liked the process: 1st power point, to get to know the empire. 2nd Toast. This process helped me understand the empires. ."

- "Elaborate more on what actually happened instead of the Socratic seminar [debrief] because I would've liked to know more concrete details."

- "Remove the reception (I think this could have been a two-week project)."

After a year of designing and testing the curriculum, we have come to understand that some problems and their components feel more authentic than others. Representatives of the early modern empires were rarely gathered together at one reception, and diplomacy is obviously conducted over a longer period of time with changing players. However, the toasts our student diplomats made at that diplomatic reception would not have been out of place at a White House state dinner (although our students' were briefer), and the skills they used in trying to woo a trading partner were just as real.

As we continue to refine this course of study, the healthy tension between the work of the historian and the work of the actor remains, as does the desire to create a curriculum where students can meaningfully engage in both.

Editor's Note: Visit " Case Study: Reinventing a Public High School with Problem-Based Learning " to stay updated on Edutopia's coverage of Sammamish High School.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Visualization as an Aid to Problem-Solving: Examples from History

This paper presents a historical overview of visualization as a human problem-solving tool. Visualization strategies, such as mental imagery, pervade historical accounts of scientific discovery and invention. A selected number of historical examples are presented and discussed on a wide range of topics such as physics, aviation, and the science of chaos. Everyday examples are also discussed to show the value of visualization as a problem-solving tool for all people. Several counter examples are also discussed showing that visualization can sometimes lead to erroneous conclusions. Many educational implications are discussed, such as reconsidering the dominant role and value schools place on verbal, abstract thinking. These issues are also considered in light of emerging computer-based technologies such as virtual reality. (Contains 17 references.) (AuthorJLB) *************************** *****:.A.*******A.***.AA:.A::****i'"i.A:.A Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best th...

Related Papers

The Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on Mathematical Education

Michal Yerushalmy

New Zealand Journal of Mathematics 32, 173-194.

Anna Sierpinska

Carina Savander-Ranne