This New Year, our focus is clearer. Wiley Education Services is now Wiley University Services. Explore our flexible, career-connected services.

Top Challenges Facing U.S. Higher Education

Last updated on: November 2, 2021

Historically, colleges and universities have relied on traditional economic models to sustain them. For the majority of private institutions, that meant enrolling a stable number of tuition-paying students. In the case of public institutions, it meant receiving consistent state appropriations, in addition to tuition revenue. The pace of change in the economy, as well as the global COVID-19 pandemic, has impacted the reliability of traditional models, putting pressure on institutions to readjust their strategies.

Below is a list of the top challenges confronting U.S. institutions:

- Student Enrollment is Declini ng Overall : In a survey conducted by Inside Higher Ed and Gallup, only 34 percent of the institutions polled met their enrollment targets for the fall 2017 term by May 1 (declining from 37 percent in 2016 and 42 percent in 2015). In addition, 85 percent of senior admission staff reported that they are very concerned about reaching institutional enrollment targets.

- Financial Difficulties: Inside Higher Ed also surveyed 400 chief business officers in 2017 and reported that 71 percent agreed that higher education institutions are facing significant financial difficulties. This is an increase of 8 percent from 2016.

- Fewer High School Graduates: T he Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education data estimated that in 2017 there were 80,000 fewer high school graduates than in the previous year, a decline of more than 2 percent. The sharpest declines were in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana.

- Decreased State Funding: Multi-year decreased state funding for public institutions and community colleges has resulted in reduced critical services for students, putting significant strain on institutions.

- Lower World Rankings: Decreased state funding for flagship universities is responsible, in part, for the United States slipping in world rankings. Times Higher Education’s publication of the 14th annual World University Rankings of 1,000 institutions from 77 countries revealed that America’s domination of the rankings has slipped. For the first time in the history of the report, no U.S. school ranked in the top two spots.

- Declining International Student Enrollments: According to estimates cited by ICEF Monitor, 28 percent of all international students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities in 2001, but by 2014, the amount dropped to 22 percent. In addition, 40 percent of U.S. college and university deans expected declines in international student enrollments for the fall 2017 term.

To address these challenges, a number of institutions have reported that they will increase their focus on:

- Online Education: A survey of chief academic officers conducted by Inside Higher Ed revealed that 82 percent plan to grow their institution’s online course offerings to expand access to adult and non-traditional students in the next year.

- International Student Recruitment: In an attempt to offset the decline in the number of U.S. high school graduates, an increasing number of admission officers plan to expand their international student recruitment programs.

- College Mergers and Acquisitions: Schools with little brand‐name recognition and low endowments may not be able to effectively navigate the impact of decreased domestic and international student enrollments and decreased state funding. Some institutions may choose to merge to save money, add depth or breadth to their operations, or supplement resources.

Updates for 2021

While the above challenges remain valid, there have been new trends heating up the higher education industry:

- COVID-19 Impact: As the global COVID-19 pandemic changed the way we live, it also resulted in a new group of challenges for higher ed. Not only did universities have to transition their on-campus classes to virtual settings, but they have also have had to address concerns around enrollment, finances, and student support . While it’s too early to tell what the long-term effects will be, presidents and chancellors have voiced their concerns in this Inside Higher Ed survey . For more information about supporting students in virtual settings, check out our Virtual Instruction Resources .

- AI Will Personalize the Student Journey: While some higher education professionals worry that AI could weaken the personal connection students have with universities, studies have shown that AI boosts personalization . Administrators should explore the variety of benefits AI offers and identify ways to tailor student support for every step of their journey.

- Competency-Based Education: Competency-based education has long been inconsistent in the education landscape. Universities should work together to clearly define standards and measurements when awarding credit for work experience. This will help students graduate faster.

- Personal growth and career advancement are top-of-mind for online students: Online students seek to achieve personal and career success through their degrees. Our 2021 Voice of the Online Learner report shows that online learners list their top outcomes as salary increase, new career, a promotion, and increased confidence in the workplace.

The trends outlined above suggest that higher ed administrators will need to explore new technologies and strategies to reach new student populations . Read the full article from Enrollment Management Report about shifts in higher education driving new approaches within institutions.

For higher education trends and approaches to change management, visit our Resources page.

Subscribe today to Enrollment Management Report for proven solutions to admit, recruit, and retain high-quality students.

Research Report

Voice of the online learner 2023.

Inside Higher Ed: 2023 Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officers

State of the Education Market 2023 Graduate Report

Recent articles.

Putting community first: growing nursing program enrollments at Florid...

These cutting-edge techniques are an enrollment game changer

New year, new trends: Discover three insights and predictions for 2023...

Ohio University: Continuous Progress Through a Student-Centered Partne...

Is Your University Prepared to Recruit Graduate Students to Online Pro...

Marketing Practices That Make You A Top-Of-Mind University

Student Retention Strategies

It’s Time for Your University’s Digital Wellness Check-Up

Personalize Your Student Engagement Process in 6 Steps

Academic Ghost Hunters: Bringing Learners Back to Lifelong Learning...

Small Changes Can Make Your Courses More Inclusive

By Simplifying the Student Application Process, Your University Wins...

Let's Talk.

Complete the form below, and we’ll be in contact soon to discuss how we can help.

If you have a question about textbooks, please email [email protected].

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Organization *

- Country * Afghanistan Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Brunei Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Colombia Comoros Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Polynesia Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Greenland Grenada Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati North Korea South Korea Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Micronesia Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine, State of Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russia Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Saint Martin Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Sudan, South Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Togo Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela Vietnam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S. Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- I'm interested in * Wiley University Services Wiley Beyond Advancement Courses Wiley Edge Other

- What would you like to learn more about—partnership models, technology services, media request assistance, etc.? *

By submitting your information, you agree to the processing of your personal data as per Wiley's privacy policy and consent to be contacted by email.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

4 trends that will shape the future of higher education

Higher education needs to address the problems it faces by moving towards active learning, and teaching skills that will endure in a changing world. Image: Vasily Koloda for Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Diana El-Azar

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

Listen to the article

- Measures adopted during the pandemic do not address the root causes of the problems facing higher education.

- Institutions need to undertake true reform, moving towards active learning, and teaching skills that will endure in a changing world.

- Formative assessment is more effective than high-stakes exams in equipping students with the skills they need to succeed.

Since the onset of the recent pandemic, schools and universities have been forced to put a lot of their teaching online. On the surface, this seems to have spurred a series of innovations in the education sector. Colleges around the world embraced more flexibility, offering both virtual and physical classrooms. Coding is making its way into more school curricula , and the SAT exam for college admission in the US has recently been shortened and digitized , making it easier to take and less stressful for students.

These changes might give the illusion that education is undergoing some much-needed reform. However, if we look closely, these measures do not address the real problems facing higher education. In most countries, higher education is inaccessible to the socio-economically underprivileged, certifies knowledge rather than nurtures learning, and focuses on easily-outdated knowledge. In brief, it is failing on both counts of quality and access.

Have you read?

Four ways universities can future-proof education, the global education crisis is even worse than we thought. here's what needs to happen, covid-19’s impact on jobs and education: using data to cushion the blow, higher education trends.

In the last year, we have started to see examples of true reform, addressing the root causes of the education challenge. Below are four higher education trends we see taking shape in 2022.

1. Learning from everywhere

There is recognition that as schools and universities all over the world had to abruptly pivot to online teaching, learning outcomes suffered across the education spectrum . However, the experiment with online teaching did force a reexamination of the concepts of time and space in the education world. There were some benefits to students learning at their own pace, and conducting science experiments in their kitchens . Hybrid learning does not just mean combining a virtual and physical classroom, but allowing for truly immersive and experiential learning, enabling students to apply concepts learned in the classroom out in the real world.

So rather than shifting to a “learn from anywhere ” approach (providing flexibility), education institutions should move to a “learn from everywhere ” approach (providing immersion). One of our partners, the European business school, Esade, launched a new bachelor’s degree in 2021, which combines classes conducted on campus in Barcelona, and remotely over a purpose-designed learning platform, with immersive practical experiences working in Berlin and Shanghai, while students create their own social enterprise. This kind of course is a truly hybrid learning experience.

2. Replacing lectures with active learning

Lectures are an efficient way of teaching and an ineffective way of learning. Universities and colleges have been using them for centuries as cost-effective methods for professors to impart their knowledge to students.

However, with digital information being ubiquitous and free, it seems ludicrous to pay thousands of dollars to listen to someone giving you information you can find elsewhere at a much cheaper price. School and college closures have shed light on this as bad lectures made their way into parents’ living rooms, demonstrating their ineffectiveness.

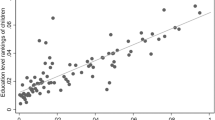

Education institutions need to demonstrate effective learning outcomes, and some are starting to embrace teaching methods that rely on the science of learning. This shows that our brains do not learn by listening, and the little information we learn that way is easily forgotten (as shown by the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve , below). Real learning relies on principles such as spaced learning, emotional learning, and the application of knowledge.

The educational establishment has gradually accepted this method, known as 'fully active learning'. There is evidence that it not only improves learning outcomes but also reduces the education gap with socio-economically disadvantaged students. For example, Paul Quinn College, an HBCU based in Texas, launched an Honors Program using fully active learning in 2020, combined with internships at regional employers. This has given students from traditionally marginalised backgrounds the opportunity to apply the knowledge gained at university in the real world.

3. Teaching skills that remain relevant in a changing world

According to a recent survey, 96% of Chief Academic Officers at universities think they are doing a good job preparing young people for the workforce . Less than half (41%) of college students and only 11% of business leaders shared that view. Universities continue to focus on teaching specific skills involving the latest technologies, even though these skills and the technologies that support them are bound to become obsolete. As a result, universities are forever playing catch up with the skills needed in the future workplace.

What we need to teach are skills that remain relevant in new, changing, and unknown contexts. For example, journalism students might once have been taught how to produce long-form stories that could be published in a newspaper; more recently, they would have been taught how to produce shorter pieces and post content for social media. More enduring skills would be: how to identify and relate to readers, how to compose a written piece; how to choose the right medium for your target readership. These are skills that cross the boundaries of disciplines, applying equally to scientific researchers or lawyers.

San Francisco-based Minerva University, which shares a founder with the Minerva Project, has broken down competencies such as critical thinking or creative thinking into foundational concepts and habits of mind . It teaches these over the four undergraduate years and across disciplines, regardless of the major a student chooses to pursue.

4. Using formative assessment instead of high-stake exams

If you were to sit the final exam of the subject you majored in today, how would you fare? Most of us would fail, as that exam did not measure our learning, but rather what information we retained at that point in time. Equally, many of us hold certifications in subject matters we know little about.

Many people gain admission to higher education based on standardized tests that skew to a certain socio-economic class , rather than measure any real competency level. Universities then try to rectify this bias by imposing admission quotas, rather than dissociating their evaluation of competence from income level. Many US universities are starting to abandon standardized tests, with Harvard leading the charge , and there have been some attempts to replace high-stake exams with other measures that not only assess learning outcomes but actually improve them.

Formative assessment, which entails both formal and informal evaluations through the learning journey, encourages students to actually improve their performance rather than just have it evaluated. The documentation and recording of this assessment includes a range of measures, replacing alphabetical or numerical grades that are uni-dimensional.

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent social and political unrest have created a profound sense of urgency for companies to actively work to tackle inequity.

The Forum's work on Diversity, Equality, Inclusion and Social Justice is driven by the New Economy and Society Platform, which is focused on building prosperous, inclusive and just economies and societies. In addition to its work on economic growth, revival and transformation, work, wages and job creation, and education, skills and learning, the Platform takes an integrated and holistic approach to diversity, equity, inclusion and social justice, and aims to tackle exclusion, bias and discrimination related to race, gender, ability, sexual orientation and all other forms of human diversity.

The Platform produces data, standards and insights, such as the Global Gender Gap Report and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion 4.0 Toolkit , and drives or supports action initiatives, such as Partnering for Racial Justice in Business , The Valuable 500 – Closing the Disability Inclusion Gap , Hardwiring Gender Parity in the Future of Work , Closing the Gender Gap Country Accelerators , the Partnership for Global LGBTI Equality , the Community of Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officers and the Global Future Council on Equity and Social Justice .

The International School in Geneva just launched its Learner Passport that includes measures of creativity, responsibility and citizenship. In the US, a consortium of schools have launched the Mastery Transcript Consortium that has redesigned the high school transcript to show a more holistic picture of the competencies acquired by students.

Education reform requires looking at the root cause of some of its current problems. We need to look at what is being taught (curriculum), how (pedagogy), when and where (technology and the real world) and whom we are teaching (access and inclusion). Those institutions who are ready to address these fundamental issues will succeed in truly transforming higher education.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education and Skills .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

What helped this founder pivot and help modernize the largest transit system in the US?

Johnny Wood and Linda Lacina

April 25, 2024

Why we need global minimum quality standards in EdTech

Natalia Kucirkova

April 17, 2024

How we can prepare for the future with foundational policy ideas for AI in education

TeachAI Steering Committee

April 16, 2024

How boosting women’s financial literacy could help you live a long, fulfilling life

Morgan Camp

April 9, 2024

How age-friendly universities can improve the lives of older adults

David R. Buys and Aaron Guest

March 26, 2024

How universities can use blockchain to transform research

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

A crisis is looming for U.S. colleges — and not just because of the pandemic

This article about college financial health was produced in partnership with The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. This is part 1 of the Colleges in Crisis series .

Dozens of colleges and universities nationwide started 2020 already under financial stress. They’d spent the past decade grappling with declining enrollments and weakening support from state governments.

Now, with the added pressures of the coronavirus pandemic , the fabric of American higher education has become even more strained: The prospect of lower revenues has already forced some schools to slash budgets and could lead to waves of closings, experts and researchers say.

To examine how institutions were positioned to respond to such a crisis, The Hechinger Report created a Financial Fitness Tracker that put the nation’s public institutions and four-year nonprofit colleges and universities through a financial stress test, examining key metrics including enrollment, tuition revenue, public funding and endowment health.

Schools faring the worst in these areas — meaning that they are projected to dip under the 20th percentile in a particular category — are marked with warning signs in the tracker. A total of 2,662 schools were included in the analysis, and 2,264 had enough data to be evaluated in every category. All data predates the pandemic.

Our analysis of the stress test results found:

- Nationwide, more than 500 colleges and universities show warning signs in two or more metrics.

- The problems were not evenly spread among states. Combined, Ohio and Illinois have more than 10 percent of all the institutions potentially facing trouble. Ohio has 36 institutions with two or more warning signs. Illinois has 26.

- Roughly 1,360 colleges and universities have seen declines in first-year fall enrollment since 2009, including about 800 four-year institutions.

- Nearly 30 percent of all four-year schools brought in less tuition revenue per student in 2017-18 than in 2009-10.

- About 700 public campuses received less in state and local appropriations in 2017-18 than in 2009-10, and about 190 private four-year institutions saw the size of their endowments fall relative to their costs.

Many factors can cause colleges to struggle financially, according to a review of the data and interviews with 39 college finance researchers, student advocates, state officials, school administrators and faculty members. Over the last decade, enrollment slipped as the economy grew. Demographics are working against institutions in parts of the country as the number of teens — and thus the number of high school graduates — drops. State support still lags behind what it was before the Great Recession. Many colleges and universities have a history of mismanaging their finances , increasing spending even as enrollments fell or going deeply into debt to construct new buildings.

At worst, institutions under financial stress can fold — sometimes overnight, as government and accrediting oversight fails to prevent precipitous closures that throw students’ lives into disarray. Even in the case of orderly closings, students’ educations can be significantly disrupted — many drop out and never finish their degrees.

More than 50 public and nonprofit institutions have closed or merged since 2015, and experts expect to see more closures in the coming academic year. Even if colleges manage to stay open, they may have to make deep cuts to do so, which could ultimately hurt students as well.

“Think of the revenue shocks these universities are suffering,” said Gregory Price, an economics and finance professor at the University of New Orleans, noting that if students aren’t on campuses for the coming academic year or choose not to attend at all, schools could miss out on even more. “I don’t want to sound too alarmist, but this could possibly be devastating.”

The “stress test” that informed The Hechinger Report’s Financial Fitness Tracker was developed by Robert Zemsky, a University of Pennsylvania education professor; Susan Shaman, the former director of institutional research at Penn; and Susan Campbell Baldridge, a professor and former provost at Middlebury College. Their methodology draws on a uniform set of federal data that most schools have reported steadily over the past decade and allows public and private institutions to be scored according to similar standards. (For-profit schools are not included in their methodology.)

The Hechinger Report’s Financial Fitness Tracker takes the researchers' “stress test” and applies it to individual schools to make the scores transparent and public.

For private colleges, the Hechinger Report tool tracked enrollment, retention, average tuition revenue per student and endowment-to-spending ratios. For public four-year colleges, the metrics were enrollment, retention, average tuition revenue per student and state funding. And for public two-year colleges, the analysis checked enrollment, state and local funding and the ratio of tuition revenue to instructional costs.

Related : Enrollment and financial crises threaten growing list of academic disciplines

The stress test is not a crystal ball to predict closures. Many colleges on the verge of collapse remain that way for years, continually finding ways to survive. Others, whose circumstances may look less dire, can close suddenly. Interpreting the nuances of any given institution’s financial situation is complicated.

Even so, experts say the metrics in the tool provide valuable insights. “They’re a really great starting point,” said Doug Webber, an associate economics professor at Temple University. Enrollment and tuition revenue, in particular, “don’t tell you everything, but they get you a lot of the way there.”

For more of NBC News' in-depth reporting, download the NBC News app

A deeper look at Ohio, which is one of the centers of the nation’s higher education financial crisis, shows how these trends interact to create different forms of financial stress at different types of institutions. In Ohio, state budget cuts and a declining population of teens have combined to create financial struggles for schools. Ohio has lagged behind the national average in restoring funding to higher education following the 2008 recession. All kinds of institutions — from large public universities to small private schools — face challenges.

“We’re just swimming deep in the ocean right now,” said Chris Pines, a former full-time philosophy and humanities professor at the University of Rio Grande in southeastern Ohio, who recently lost his position due to the school's financial problems. “We’re treading water and there’s no raft. I don’t know what the long-term future looks like.”

Enrollment declines lead to difficult cuts

Colleges have lost hundreds of thousands of students since 2010, when undergraduate enrollment peaked at just above 18 million. That figure declined to 16.6 million in 2018. Nearly 600 two- and four-year institutions saw their incoming fall enrollments drop more than a quarter in that time period.

“If your enrollment is cratering, then you’re probably not going to be raising tuition, because that’s just going to compound the problem,” Temple University’s Webber said. “So you’re going to be spending less.”

The University of Rio Grande, a private four-year university in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, has struggled with falling enrollment for years. The university, which partners with the public Rio Grande Community College, plays an important role for the surrounding counties, which include some of Ohio’s poorest residents. About half of the students at the two schools receive Pell Grants, a form of federal aid for low-income students.

Both institutions have recently faltered. Their combined enrollment fell from 3,264 students in 2012-13 to 2,227 in 2018-19, according to federal data. The number of high school students in Ohio has dropped within the last decade, leading to fewer high school graduates, according to state and federal data. Those who do enroll at Rio Grande’s campuses often don’t stay; annual retention rates hover just above 50 percent for full-time students and are often even lower for part-time students.

Related: With enrollment sliding, liberal arts colleges struggle to make a case for themselves

In April 2019, Rio Grande faculty secretly held a vote of no confidence in the schools’ governing boards, alleging that administrators had kept spending as if the supply of new students would keep increasing. The board’s mistakes, the faculty argued, had led to “persistent and severe budget deficits.”

Shortly after that no-confidence vote, 18 professors — about a fifth of the full-time faculty — were told they would be let go, according to Rio Grande officials. (Two were brought back full-time and two will work as part-time adjuncts.) Programs that were deemed too small were eliminated entirely, such as the school’s music program.

Pines, who was among the 18 let go and will only be teaching part-time this fall, said many faculty viewed the budget problems as a “foreseeable train wreck.”

News How higher education's own choices left it vulnerable to the pandemic crisis

The reductions saved the school nearly $1 million, according to Ryan Smith, the university’s president, who assumed his role in October 2019, after the cuts had been made. He said he understood the frustration of faculty members, but that the downsizing had been necessary. “We kind of bottomed out as far as what we were offering before,” he said.

Pines says he can’t completely fault the prior administration for making the tough cuts, but he worries for recent and future graduates: “How would the bigger world perceive the value of our degree if, basically, you gutted most of your qualified faculty?”

Related: Some colleges seek radical solutions to survive

Smith has restructured some of the university’s debt to fully fund pension liabilities and hired a marketing director; the administration also added more sports teams to try to attract students. Smith projects enrollment growth this fall and believes the school will ultimately be able to increase the number of programs it offers. When that happens, it’ll be a challenge to figure out “how do we grow back to where we were?” he said. “But we’ve got to be able to survive today.”

State funding cuts add to financial problems

As in most states , Ohio’s higher education system hasn’t fully recovered from the recession of a decade ago. In 2018, the state was still spending 17 percent less per student than it spent in 2008. Nationally, that figure was 13 percent less. More than half of public campuses nationwide have had state and local appropriations decrease since 2008, according to federal data.

Higher education finance experts predict more cuts ahead for public institutions as the coronavirus decimates state budgets. Some have already started. In May, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, announced $110 million in higher education cuts, a nearly 4 percent budget reduction for each institution.

News Dozens of colleges have abruptly closed — and efforts to protect students have failed

Eighteen Ohio institutions lost more than $1 million each. The cut for the University of Akron, for instance, was more than $3.7 million. The school had already run deficits for the last three years and, in late spring, announced that it needed to shave $65 million from its $325 million budget. In mid-July, the board of trustees voted to eliminate 97 full-time professor positions — more than 1 in 6 at the university — and 60 other staff members. (The plan still needs to be ratified by the union.)

Related: Budget cuts are taking the heaviest toll on colleges that serve the neediest students

The budget cut was based on “significant” revenue losses from the spring campus closure, enrollment projections and state funding trends, Christine Boyd, director of media relations, said in an email.

“Throughout the budget process, great care has been taken to preserve academic quality and ensure that support services — from financial aid to academic support — remain strong to help our students on their degree journey,” Boyd added.

Lt. Gov. Jon Husted suggested in June to the news website Cleveland.com that there were limits to how much the state could help struggling institutions. “You can never subsidize something enough to escape the laws of economics,” he said.

Husted told The Hechinger Report that the state intended to continue supporting higher education but had to balance the budget. He added that the higher education landscape had already been changing, with students concerned about the cost of a degree and looking for other options.

“They’re facing great challenges,” he said, adding that the colleges that can adapt will succeed. “That’s just the reality.”

Pamela Schulze, a family studies professor at the University of Akron and its faculty union president, says the state has to help public colleges and universities survive, including by providing more funding. “Of course the state can do something about it, because it’s the state university system,” Schulze said. “If they leave their university system in tatters, we really are not going to be able to fulfill our role in the state of Ohio.”

Schools with shrinking endowments scramble to raise money

State money and tuition are not schools’ only sources of funds. Many colleges and universities rely on money from their endowments, particularly to weather financial storms. Schools typically draw down a percentage of their endowments every year, trying to spend only the interest and keep the funds growing.

The larger their endowment, the less schools have to rely on other sources of revenue, and the greater financial stability they have. But about 330 schools in our tracker saw their endowments decrease over the last decade relative to their costs, according to federal data; 57 percent were private institutions.

Among them is Wilberforce University, a historically Black university outside of Dayton, Ohio. Its endowment dropped from $12 million in 2014 to $8.2 million in 2018.

News Getting a college degree was their dream. Then their school suddenly closed for good.

The median endowment for historically Black colleges and universities is half that of other colleges and universities of the same size, according to a 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office. Schools with small endowments were already in a precarious position, Price, the University of New Orleans professor, said. Now, he added, coronavirus-related revenue losses threaten to make it even harder for these schools to survive.

“It’s going to be very challenging for a place like Wilberforce to sustain itself,” Price said.

Related: Already stretched universities now face tens of billions in endowment losses

Wilberforce is currently on probation with its accreditor because of financial problems; the issues stretch back for years. In 2012, hundreds of students demanded transfer applications as a protest because “we’re not getting our quality education,” as one student put it, according to a local news report. In 2013, students held another protest , holding signs saying “Fix the dorms now” and “Broken promises,” according to a news report.

In the spring of 2019, Wilberforce’s president, Elfred Pinkard, announced an ambitious effort to raise $2 million in about two months and $5 million by the end of the year. Wilberforce fell well short of those goals, but, buoyed by a $1.2 million anonymous gift last fall, coupled with $1.7 million in loan forgiveness, Pinkard said, they met the $5 million goal in June.

Fundraising is a crucial way to boost endowments, but Price said HBCUs have historically struggled to get philanthropists’ attention, despite the important role they play in helping Black Americans achieve upward mobility. To survive, schools must find ways to persuade more donors to give.

Pinkard, who was appointed at the end of 2017, remains optimistic. In response to student concerns raised during the protests, members of the board of trustees were replaced. Officials have renovated and repaired campus buildings and started a dual-enrollment program for nearby high schoolers.

“We have been very intentional and disciplined in our attention to charting a sustainable path forward,” Pinkard said in a statement. “We join the community of institutions in higher education who are all vulnerable but determined to reimagine higher education in a post-COVID-19 environment.”

Still, with too many colleges competing for a shrinking pool of students and the consequences of the coronavirus bearing down, higher education may face tumultuous years ahead, Price warned.

“A lot of underendowed, financially fragile institutions are going to have to shut their doors, unfortunately,” he said.

Sign up for The Hechinger Report’s higher education newsletter .

Sarah Butrymowicz is senior editor for investigations at The Hechinger Report.

Pete D’Amato is the data visualization developer at The Hechinger Report.

The Seekers

- Posted November 7, 2022

- By Lory Hough

- Entrepreneurship

In the education world, it’s easy to identify problems, less easy to find solutions. Everyone has a different idea of what could or should happen, and change is never simple — or fast. But solutions are out there, especially if you look close to the source: people who have been impacted in some way by the problem. Meet eight current students and recent graduates who experienced something — sometimes pain, sometimes frustration, sometimes hope — and are now working on ways to help others.

SEEKER: Elijah Armstrong, Ed.M.'20

“This motivated me to become an activist in the space of disability and education,” he says. “Education is supposed to act as a gateway for students, but far too often, for people with disabilities, it acts as a barrier.”

His experience led him to start a nonprofit while he was in college at Penn State called Equal Opportunities for Students “as a way to help tell the stories of marginalized students in education.” Then last year, he won the 2021 Paul G. Hearne Emerging Leader Award, an award given by the American Association of People with Disabilities that recognizes up and coming leaders with disabilities. With his prize money, Armstrong started his own award program: the Heumann-Armstrong Educational Awards, named partly for disability rights activist Judy Heumann. The award is given annually to students (sixth grade and up) who have experienced ableism — the social prejudice against people with disabilities — and have fought against it.

“Students with disabilities face barriers in education that aren’t faced by their non-disabled peers,” he says. “At all levels of education, students are forced to do intense emotional and logistical labor to fight for accommodations or go without accommodations at all. This is on top of the day-to-day challenges of having a disability or chronic illness, and the challenges that go along with that. Students with disabilities should have ways of being compensated for that labor and denoting that labor on resumes.”

One of the unique aspects of the award program, he says, is that winners aren’t restricted on how they can use their award money, although several from the inaugural round have used it to fund their own activism. For example, Otto Lana, a high school student, started a company called Otto’s Mottos that sells T-shirts and letterboards to help purchase communication devices for non-speaking students who can’t afford them. Himani Hitendra, a middle schooler, has been producing videos to educate her teachers and classmates about her disability, as well as ways they can be more inclusive. Jennifer Lee, a Princeton student, founded the Asian Americans with Disabilities Initiative.

Armstrong, who is also currently living and working in Washington, D.C. as a fellow with the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, says beyond awarding money to other young activists, one of the biggest and most impactful ways he thinks he’s helping to challenge the education system is through the videos his nonprofit produces for each of the winners.

“We highlight the award winners and give them a platform to tell their stories in a way that gives them agency,” he says. “Education doesn’t often take the voices or experiences of disabled students into account when discussing accessibility in education. We want to make sure we develop a platform that gives voice to the narratives of these students, so that everyone can listen to and learn from them.”

Learn about his nonprofit: equalopportunitiesforstudents.org

SEEKER: Elisa Guerra, Ed.M.’21

In the early 2000s, Guerra wasn’t finding the kind of educational experience for her young children near her home in Aguascalientes, México, that she was looking for — one that was warm, but also ambitious and fun and stimulating.

“I saw a gap between what schools offered at that time and what parents like me were dreaming of for their young,” she says. “After my son went through three different schools and none was a true fit, I decided that I needed to imagine and create the school I wanted for my children.”

So Guerra, without any formal teaching experience, started Colegio Valle de Filadelfia, a small preschool with 17 kids that was based on what she was doing informally at home with her ownchildren. Those first few years, she says she pretty much did every job the school had, learning along the way.

“I taught. I answered the phone. I designed our programs. I managed promotion and enrollment,” she says. “I also changed diapers, cleaned noses, and mopped puke.” For many years, she served as the principal.

She also fine-tuned their learning model, what they started calling Método Filadelfia , or the Philadelphia Method. Based on the work of Glenn Doman and The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, their model isn’t your typical approach for helping young children learn.

“We teach — playfully and respectfully — tiny children, starting at age three, to read, and [we also teach] art, physical excellence, and world cultures as the first steps of global citizenship,” she says. Music lessons, including violin, are started at the preschool level, and classes are taught in two foreign languages in addition to a student’s first language. When Guerra first started the school, there were no commercial textbooks that fit what she was trying to do, so she wrote her own.

Since then, schools across Mexico, as well as Costa Rica, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Ecuador now use her textbooks. Al Jazeera made a documentary about her as part of their Rebel Educator series. Twice she was a finalist for Global Teacher of the Year. Just before the pandemic hit, she was appointed to unesco’s International Commission on the Futures of Education, a small group that includes writers, activists, professors (including Professor Fernando Reimers, Ed.M.’84, Ed.D.’88), anthropologists, entrepreneurs, and country presidents. (When UNESCO first reached out to her, she thought it was a scam and almost didn’t respond back to them.)

And it all started 23 years ago with an idea and, as she says, some naivete.

“In retrospect, it was crazy. Most people I know who have opened schools have done it ‘the right way,’ if such a thing exists,” Guerra says. “They were experienced teachers, or they even ran schools as principals, before jumping out to create a new one. They could do better because they knew better. I did not have that advantage. I had so much to learn myself. But in a way, that was also a blessing because I also had much less to ‘unlearn.’ …I said before that I became a teacher accidentally, but that is only partly accurate. Indeed, I was not expecting my life to take the path of education. But once I found myself there, it was my decision to stay. The discovery of a passion for teaching was the accident. To embrace the teaching profession was a choice.”

Read more about her work: elisaguerra.net/english/

SEEKER: Cynthia Hagan, Ed.M.’22

“I’ve lived here for 35 years and have witnessed the impact of poverty and the opioid crisis on our communities,” she says, “both on current realities and hopes for the future.”

Initially, when she first applied to Harvard, she thought she’d create a children’s program using puppets, inspired, in part, by Sesame Street , but after taking a few classes, Hagan’s ideas on how to help children in her state evolved.

“I became fascinated with the concept of designing for joy as introduced to us in the course What Learning Designers Do,” taught by Senior Lecturer Joe Blatt, she says. “Joy is an often-overlooked ingredient for learning.” The power of story also began to stick.

After creating a class project called Adventure Box, focused on increasing third-grade reading levels for children experiencing homelessness, Hagan’s idea for Book Joy emerged.

Research shows that children who are not proficient in reading by the third grade, when they transition from learning to read to reading to learn, are four times more likely to drop out of high school, and six times as likely to be incarcerated as an adult.

“I knew that the overall thirdgrade reading levels of children experiencing poverty in rural Appalachia were significantly lagging,” she says. “It just seemed like a logical move to modify Adventure Box to meet the needs of this population.”

She decided to focus first on McDowell County, West Virginia, once one of the largest coal producing areas in the world, where the child poverty rate in 2019 was a staggering 48.6%.

Hagan’s idea with Book Joy is simple but potentially life altering for the young children they began targeting starting this past September: give each incoming kindergarten student a curated box filled with high-quality books (printed and audio) based on interest and reading level, plus fun related activities to conceptualize the reading experience, and then follow up with new boxes quarterly (December, March, June) until third grade. The goal is to significantly increase third-grade reading proficiency.

For the launch this fall, Book Joy partnered with Scholastic to get discounted books and with Random House for free books. McDowell’s assistant superintendent/federal programs manager has been actively involved. Twice a year, Book Joy will conduct assessments with the students, their parents, and their teachers, to see how each box is working, and then tweak the content. They’ll also use feedback to improve on future boxes and teachers can use assessments to provide individualized intervention, as needed.

“When their interests, reading levels, or personal circumstances change,” says Hagan, “so does the contents of their box.”

Another goal for Book Joy, beyond improving third-grade reading proficiency for children in one of the poorest districts in Hagan’s state, is something fundamental to this former librarian: to bring joy to reading and learning, hence the name, Book Joy.

“Each box is truly a gift created just for them. No two boxes will be alike because no two children are alike,” she says. “And we are designing these boxes from an edutainment perspective, putting as much focus on eliciting joy as we do in choosing the best aligned reading material. We want every design element of the box, from the moment the children lay eyes on it to the emptying of every item, to elicit joy.”

Discover how you can help: givebookjoy.org

SEEKER: Ben Mackey, Ed.M.’13

In 2020, the district unanimously passed the Environmental & Climate Resolution, a massive overhaul of how schools in the Dallas Independent School District approach climate change. It includes reviewing and revising current policies across all schools and setting goals for reducing the district’s environmental footprint, while also keeping an eye on spending.

Mackey, a former math teacher and principal, says that it was young people in the district who really got the ball rolling when it came to making sure the district was thinking about its impact on the environment and then making a plan for change — something few districts are doing.

“The genesis of this resolution and the work really started with students,” he says. “When I took office in 2019, there was a small but mighty group of students who had been coming and attending every board meeting and sharing their perspectives and imploring the school board to make strides in its sustainability work. I was able to work with these students to get this resolution drafted and passed by the school board.”

What passed is a 10-year plan to drastically improve the district’s sustainability practices, including some steps that have already been taken, including switching energy plans and contracting for 100% renewable energy, which is expected to save the district $1 million a year on top of the energy benefits. By 2027, all plates, utensils, and trash bags will be 100% compostable.

Longer term, the district has applied for a federal grant to pilot 25 electric busses and will begin moving away from gas-powered maintenance equipment. It will limit synthetic fertilizer. The district also created a set of policies that say any new school built or existing school remodeled must include LEED silver certified standards. Another goal is to plant more trees to combat the “heat island” effect that schools that are primarily blacktop experience.

“One area that stuck out to our community group and administration as they were formulating the recommendation is how the increase in tree canopy cover can combat carbon emissions, improve learning environments, and serve to decrease energy usage,” he says. “We’re aiming to increase canopy cover at all campuses to at least 30% and we’re working with a number of phenomenal partner organizations to get this started, including the Texas Trees Foundation and the Cool Schools Parks initiatives.”

Mackey, who is the executive director of a statewide education nonprofit called Texas Impact Network(in addition to being on the school board), says his advice to other districts that want to reduce their school’s climate footprint is to get buy-in across the district — and just get started.

“Dallas ISD’s process started with students at our board meetings, speaking every single month, about the need and importance for this to happen. These students reached out to trustees and school staff and continued to come forward with both a charge and ideas for what success looks like,” he says. “The hardest part is often to get it off the ground and I’d encourage all who care about this to call your school board trustees and be a consistent and sensible voice who will share their mind and provide concrete solutions to make this work happen.”

Sign up for his monthly newsletters: benfordisd.com

SEEKER: Michael Ángel Vázquez, Ed.M.’19, current Ph.D. student

That’s why he’s trying to make the graduate years, at least for Ed School students, less stressful.

“I just went through this huge burst of depression my first year, my master’s year,” he says, “and I realized that I wasn’t the only one that was going through that.”

Part of the problem, says Vázquez, a former teacher in the Navajo Nation, is that while universities often offer great resources, many students don’t know where to turn for help or don’t even think they should ask for help.

“There’s so much pressure to feel like you know everything and not admit when you don’t,” he says.

Vázquez decided to create a comprehensive student-to-student guidebook, based on resources he knew about and those shared by other students. This “labor of love,” as he calls it, includes everything from where to find books and readings to how to save money, including where to grocery shop, how to sign up for MassHealth, how to apply for snap benefits, and how to sell items to other students through the Harvard Grad Market. He has a section on job hunting. The mental health section offers tips for finding therapists, wellness options at Harvard, ways to combat vitamin D deficiencies, and advice for advocating for yourself. Other documents include ways to prep for graduation, must-have lists for living in a colder climate, and a link to local tenants’ rights.

“I just felt like it was important to do whatever was possible for the next group of students to have a safe, happy experience, because, ultimately, learning should be fun, should be exciting,” he says. Endemic to being back in school, with all of the pressure, “it’s very common for that fun and excitement of learning” to take a back seat. “I don’t want that be the case. This guidebook is just one way to mitigate that a little bit and make it more fun and exciting for people.”

None of this support and concern for the well-being of other students surprises Vázquez’s professors, who point out that he has been one of the most active students since he got to Harvard. He’s been especially in-tune with first-gen students (he’s first gen, starting with attending the University of Southern California) and for students of color, both at the Ed School and at the college, where he’s a tutor at Adams House. He’s also been a teaching fellow for ethnic studies classes at the Ed School since 2019 and will now help teach ethnic studies to undergraduates at Harvard starting this fall. He hopes creating and sharing his guide helps all of the students he’s around.

“As a student and as somebody who is a teaching fellow and who has worked in different organizing groups on campus and off campus, I see that grad school and organizing are often very stressful,” he says. “I really want to drill that it’s OK to not know something and that learning is shared, which is why I did this. There were things I didn’t know at first. I want to share that knowledge with others, and I want it to be community-built. When you admit you don’t know something, that’s when you truly learn something.”

SEEKER: Grace Kossia, Ed.M.’17

“Anytime one of my friends unconsciously has a math moment, I always yell out, ‘You’re a mathematician!’” she says. “Too many people are walking through this life convinced that they could never be good at math. Math isn’t meant to be something we’re good at — it’s simply something we do, and when mistakes happen, we learn.”

It’s this philosophy that she and her coworkers bring to their edtech nonprofit based in Brooklyn, New York, playfully called Almost Fun, which last year helped 1.5 million middle and high school students with free online math lessons.

“The title ‘Almost Fun’ winks at the way students perk up when they engage with our resources and find unexpected joy while learning math,” she says. “We value being real with our students, and part of that is understanding that math can be a hard pill to swallow and that schoolwork may not be the number one thing students are going to want to do. However, with the right approach, we can curate experiences that make math learning ‘almost fun’ and something to look forward to for even the least confident learners.”

The backbone of their approach includes explaining concepts using easy-to-understand examples, rather than through clinical, mathematical definitions. Their distributive property lesson, for example, relates expanding and factoring an expression to opening and closing an umbrella. Their functions lesson uses a vending machine to explain how functions represent the relationship between inputs and outputs. Another lesson compares absolute value to the overall power of a superhero or villain.

Kossia says their site is meant to complement existing online sites like Khan Academy, which she says has been a trailblazer in edtech that serves many students. But as helpful as Khan is, some students still need more help — or just a different approach.

“There is still a critical number of students who struggle with high levels of math anxiety and low math confidence, which limits their ability to take full advantage of the support online resources like Khan offer,” she says. “At Almost Fun, we want to position ourselves as a complement to these existing resources by using creative math analogies to explain foundational math concepts and bridge the gaps in students’ math confidence and motivation, so that they can better benefit from the support other resources offer.”

Kossia remembers the gaps she struggled to fill after she immigrated to the United States from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the time, she was good at math, and decided to major in mechanical engineering in college. She had a hard time.

“I quickly realized that I had many gaps in my understanding of math and physics, which were essential skills I needed in this journey,” she says. “This chipped away at my confidence, but I was determined not to give up. I wanted to prove to myself and other people like me, especially Black women, that it could be done.” Later, when she worked as a physics teacher, her struggles helped her relate to students who were anxious about physics and pushed her to design creative lessons that focused on learning by doing, as opposed to learning by memorizing.

“At Almost Fun, I do the same thing but with math as the primary focus,” she says. “We believe math is more than just sets of memorized steps; it’s a way of describing relationships between things in our world.”

Access resources and lesson plans: almostfun.org

SEEKER: Shaina Lu, Ed.M.’17

“Learning about gentrification is unavoidable in placebased learning in a place like Chinatown,” Lu says. “However, it could be kind of a drag to spend your fourth-grade summer learning about gentrification.”

So Lu, an artist and former media arts teacher in Boston Public Schools, decided to make learning about this heavy topic more interesting: she created a graphic novel.

“ Noodle and Bao was my response to that feeling. I wanted to write and draw a story that elementary kids would devour and love — There’s a cat selling food in a cart! Neighborhood kids dress up and infiltrate a snobby restaurant! — but would also pay homage to some of these inspirational histories and present-day struggles they were learning about,” she says. While the novel isn’t specifically set in Boston’s Chinatown — it’s set in a fictional Town — Lu says it’s inspired by the many residents, activists, and community members of Boston’s Chinatown that she has met and worked with over the years — people who “have done so much exciting work that is more than comic book-worthy.”

Set to publish in the fall of 2024 by HarperCollins, Noodle and Bao also explores historical events from Boston’s Chinatown, most notably a fight for the land that now houses the community center where Lu worked and where elderly residents passionately voiced their displeasure to hotel developers at a meeting.

Lu says the graphic novel is just one example of something that has been important to her for many years: the intersection of art, education, and activism. Another example is a creative placemaking project she recently worked on in Chinatown with a local student in partnership with a local resident.

“The resident, youth, and I painted a community mural that featured [the resident’s] personal lens on the history of Chinatown,” she says. “The mural was painted on a condemned building on a border of Chinatown that is elslowly being eroded away by the neighboring district. It’s hard to parse out which separate part was ‘art’ or ‘activism,’ or ‘education,’ so I feel like they’re interwoven.”

Although she’s interested in teaching, Lu says classrooms are tricky places. “There’s an inherent power structure with the teacher as the fountain of knowledge and students as recipients of that.” Instead, “I’m interested in disrupting the capitalist status quo of education with ‘winners and losers’ as described by activist- philosopher Grace Lee Boggs in her 1970 essay, Education: The Great Obsession .”

She’s not interested, though, in disrupting the system on her own. “I hope to be, alongside others, building a new system, where people’s needs and interests and social responsibility define their learning, rather than their ability to produce,” she says. “There’s actually so much incredible person- centered education out there, both in and out of schools. I’ve worked with teachers who engaged students with civics project-based learning about gentrification, youth workers who have helped young people organize community gardens for their neighborhoods, and more.”

Learn about her art: shainadoesart.com

SEEKER: Justis Lopez, Current Ed.L.D. student

“I hold near to me that there are ancestors that wanted to study, but didn’t get the chance to,” he says. “There are relatives that wanted to pursue their dreams, but they put food on the table instead so that I could pursue mine, and for that I am eternally grateful and full of joy.”

It’s this gratitude and happiness for life that Lopez, a DJ known as DJ Faro (for the Spanish word, lightkeeper), is bringing to his time at the Ed School and to Project Happyvism, the culturally responsive nonprofit he started with his friend, Ryan Parker, a youth empowerment teacher and activist, that is rooted in hip hop and is a combination of happiness + activism.

“Project Happyvism is a feeling, a philosophy, and a movement that centers joy and love as a radical form of activism,” he says, meaning the commitment to loving yourself and those around you unconditionally.

“The organization embraces the beauty and need for joy,” he says, “and emphasizes the fact that maintaining happiness about who you are and what you think, say, and do in a world that consistently goes against the grain of your identity is a form of activism in itself, hence: happyvism.”

The project started from a song and video that Lopez and Parker wrote and produced and has since expanded to include helping others write songs (what they call “joy anthems”) in their recording studio, publishing a children’s book, Happyvism: A Story About Choosing Joy , and working with K–12 districts on related curriculum. They also started Joy Lab, a community gathering space in Manchester, Connecticut, where Lopez grew up, that offers yoga, wellness and equity workshops, and book readings. He plans on starting a Joy Lab at the Ed School during his time here.

“I’m just trying to create the spaces I wish I had for myself growing up,” Lopez says. “Spaces that center healing, hope, and hip hop.”

Although this is his first year as a student at the Ed School, Lopez has been involved with the school in the past, including as an organizer, MC, and DJ at the Alumni of Color Conference, thanks to Lecturer Christina Villarreal, Ed.M.’05, who later convinced him that getting into Harvard was a possibility. He also attended the Hip Hop Experience Lab conference run by Lecturer Aysha Upchurch, Ed.M.’15.

Previously, Lopez was a high school social studies teacher in Connecticut and created a hip hop class and afterschool program in the Bronx. He worked in the Hartford public schools as a climate, culture, and equity strategist, and was an adjunct professor at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas. One day, he’d like to reach even higher and become the secretary of education for the United States.

“Policy is created by people and it’s important to have people in positions of leadership that understand the experiences of the students and educators they serve,” he says. “An important factor of that being a classroom teacher. When you have taught in the classroom you understand the human-centered perspective that is needed in education that goes beyond any policy. Of the last 11 U.S. secretaries of education, only three have been classroom teachers. Secretary Cardona makes the fourth. I want to build upon the human-centered approach he has brought to the role.”

Find your joy and watch their music video: projecthappyvism.com

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Food for Thought

Up Next: CubbyCase

A subscription box filled with education products and activities

Every Child Has a Voice

Building social-emotional learning skills through the arts

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

3 Solutions to Challenges in Higher Education

August 16, 2017

A career in higher education can be an enriching work experience, not only from a professional development perspective, but a sense of belonging as well. When everyone under the academic umbrella – administrators, faculty and students – is working toward the common goal of success, the fruits of labor-intensive efforts can be realized and shared.

At the same time, though, as administrators can attest, higher education can also have its challenges.

The following are some of the biggest demands in the higher education sphere and what leadership can do to accomplish them.

Challenge No. 1: Payments associated with college attendance

As seniors graduate from high school, the odds of their success in the working environment are significantly higher by earning a college degree in the discipline of their choosing. But not everyone has the financial means to get their college careers started, and as a result, enrollment has fallen in recent years. According to the latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 19 million individuals were enrolled in an undergraduate or graduate program in 2015, down from 20.3 million in 2010.

Student loan balances are exceeding $1 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve. The financial toll is difficult for families as well, specifically for parents. According to The Institute for College Access & Success, parents who earn $30,000 or less per year have to spend more than 75 percent of their earnings to finance their children going to a four-year university. Indeed, student debt is at record highs, with student loan balances exceeding $1 trillion , according to the Federal Reserve.

This issue is not lost on college admissions directors. In fact, more than 87 percent of private institutions believe that they are losing potential applicants due to parents’ and students’ concerns about how much money they’ll owe by attending a college or university, according to a survey conducted by Inside Higher Ed.

Potential Solution: Get involved in advocacy for new solutions for student debt.

If there were an immediate answer to student debt, it would have been implemented by now. But one of the ways it may be resolved is by looking to other countries to see how they’re addressing this issue. For instance, as noted by The New York Times , university students in Australia are borrowing right around the same amount as American undergraduates, but the repayment system is different because the amount they owe at any given time is determined by how much they’re earning. For example, when the newly graduated are just starting out in the workforce, they’re absolved from paying anything until they start earning approximately $40,000 in annual salary. Once their pay exceeds this amount is when payments are due, but only up to 4 percent of their regular income until the balance is paid off in full.

“The idea is that no one facing economic hardship should have to choose between paying student debt and paying for basic necessities,” wrote Susan Dynarski, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan. “When earnings drop, loan payments drop immediately, allowing borrowers to devote their reduced budgets to essential needs.

Higher education leaders may want to consider speaking or contacting their local and state legislators to talk to them about what public policy efforts are underway that address student debt. There could be strength in numbers.

Challenge No. 2: Low graduation rates

While a majority of public university graduates believe their degree was ultimately worth the price of admission , according to polling from Gallup, many students fail to cross the finish line. Based on survey data from the Pew Research Center, less than half of 25- to 34-year-olds – 47 percent – had a two-year degree in 2015, slightly above the 42 percent worldwide average. In terms of higher education attainment, America trails Korea, Japan, Canada, Ireland, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom, among others. This is well short of the goal established by the Department of Education for 60 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds to earn an associate degree by 2020.

Unsurprisingly, more advanced degrees are even less common. As of 2015, only 11 percent of 25- to 64-year-olds in the U.S. had a master’s degree and just 2 percent had a doctorate, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Poland, Switzerland, Sweden, Spain, Slovenia and Italy are among the countries where citizens are more likely to have a graduate-level degree or equivalent.

Potential Solution: Implement support-based programs

Going to college is supposed to challenge one’s thinking and requires dedication and work to accomplish assignments and successfully pass exams. However, not to the point in which students decide that graduating isn’t worth the effort. To solve this issue, several universities are implementing programs designed to provide increased support for students. For example, a few years ago, the City University of New York system put in place something called the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP). As noted by The New York Times , ASAP provides students with various support systems and financial resources aimed at helping undergraduates succeed in their educational endeavors. Since 2007, when the ASAP initiative first launched, graduation rates have improved dramatically. In fact, students who utilized the ASAP program were two times more likely to have graduated than those who did not.

Administrators can draw from these kinds of programs to see how they may be applicable to graduate-level curricula and overcoming the various stresses that students face on their road to commencement.

Challenge No. 3: The skills gap

Recent college graduates have reason to celebrate, as the vast majority of employers are seeking to hire them. In fact, roughly three-quarters of business owners say they plan to put graduates to work this year , according to a poll conducted by Harris Poll on behalf of CareerBuilder. That’s up from 67 percent last year alone.

Yet despite having the necessary qualifications, employers are struggling to find the right fit for their open positions. Almost 60 percent of U.S. employers say some of their hiring searches take 12 weeks or longer to complete, a separate survey from CareerBuilder found. This is costing businesses nearly $1 million in estimated lost work productivity.

“The gap between the number of jobs posted each month and the number of people hired is growing larger as employers struggle to find candidates to fill positions at all levels within their organizations,” said Matt Ferguson, CareerBuilder CEO. “There’s a significant supply and demand imbalance in the marketplace, and it’s becoming nearly a million-dollar problem for companies.”

This is an issue higher education leaders can work on by learning how to better bridge the gap, benefiting not only students but potential employers as well.

Potential Solution: Go to the data

What are universities doing to bridge the skills gap? Many are turning to the numbers, accessing data on what businesses are looking for in new hires. For instance, some administrators and faculty are coordinating course material so that it aligns with the skills that companies hope to find in job applicants, The Wall Street Journal reported . This has involved compiling labor market data, population forecasts and information on where businesses are hiring so that the appropriate modifications can be implemented. University systems have also put together specific classes that help students learn about various skill-sets that are in demand.

By focusing on these strategies and other proactive measures, today’s challenges in higher education may be tomorrow’s leadership triumphs. Contact Maryville University today to learn more about the online Doctor of Education in Higher Education Leadership program and how you could join the community of problem-solvers addressing issues such as these.

Recommended Reading

Higher Education Leadership: The Prerequisites to Change

Five Challenges of Today’s Provost

The Institute for College Access & Success

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System – How Much Student Debt is Out There?

Career Builder – 74 Percent of Employers Say They Plan to Hire Recent College Graduates This Year, According to Annual CareerBuilder Survey

Career Builder – The Skills Gap is Costing Companies Nearly $1 Million Annually, According to New CareerBuilder Survey

Gallup – College Admissions Directors: Debt Concerns Cost Applicants

The New York Times – America Can Fix Its Student Loan Crisis. Just Ask Australia

Pew Research Center – U.S. still has a ways to go in meeting Obama’s goal of producing more college grads

The Wall Street Journal – Colleges Drill Down on Job-Listing Terms

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

Take Your Next Brave Step

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.4 Issues and Problems in Higher Education

Learning objectives.

- Explain why certain college students flounder.

- Describe what is meant by legacy admissions and summarize the criticism of this policy.

- List any two factors that affect college and university graduation rates.

- Describe the extent of physical and sexual violence on the nation’s campuses.

The issues and problems discussed so far in this chapter concern elementary and secondary schools in view of their critical importance for tens of millions of children and for the nation’s social and economic well-being. However, higher education has its own issues and problems. Once again, we do not have space to discuss all these matters, but we will examine some of the most interesting and important. (Recall that Chapter 7 “Alcohol and Other Drugs” discussed alcohol abuse on campus, a very significant higher education problem.)