- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

References in Research

Definition:

References in research are a list of sources that a researcher has consulted or cited while conducting their study. They are an essential component of any academic work, including research papers, theses, dissertations, and other scholarly publications.

Types of References

There are several types of references used in research, and the type of reference depends on the source of information being cited. The most common types of references include:

References to books typically include the author’s name, title of the book, publisher, publication date, and place of publication.

Example: Smith, J. (2018). The Art of Writing. Penguin Books.

Journal Articles

References to journal articles usually include the author’s name, title of the article, name of the journal, volume and issue number, page numbers, and publication date.

Example: Johnson, T. (2021). The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health. Journal of Psychology, 32(4), 87-94.

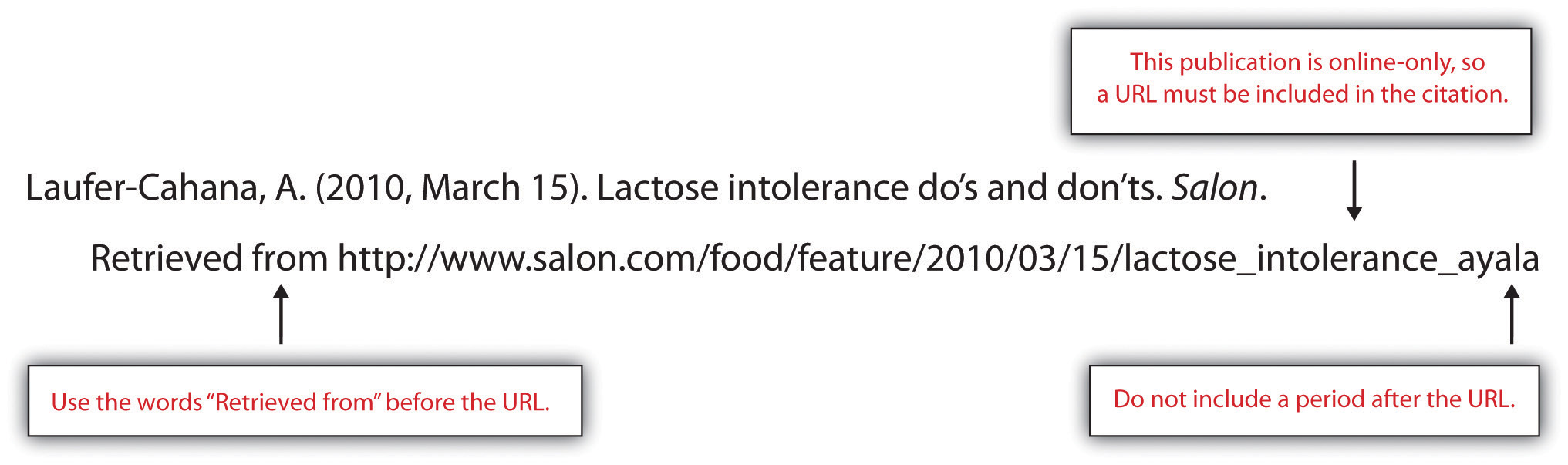

Web sources

References to web sources should include the author or organization responsible for the content, the title of the page, the URL, and the date accessed.

Example: World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

Conference Proceedings

References to conference proceedings should include the author’s name, title of the paper, name of the conference, location of the conference, date of the conference, and page numbers.

Example: Chen, S., & Li, J. (2019). The Future of AI in Education. Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Technology, Beijing, China, July 15-17, pp. 67-78.

References to reports typically include the author or organization responsible for the report, title of the report, publication date, and publisher.

Example: United Nations. (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. United Nations.

Formats of References

Some common Formates of References with their examples are as follows:

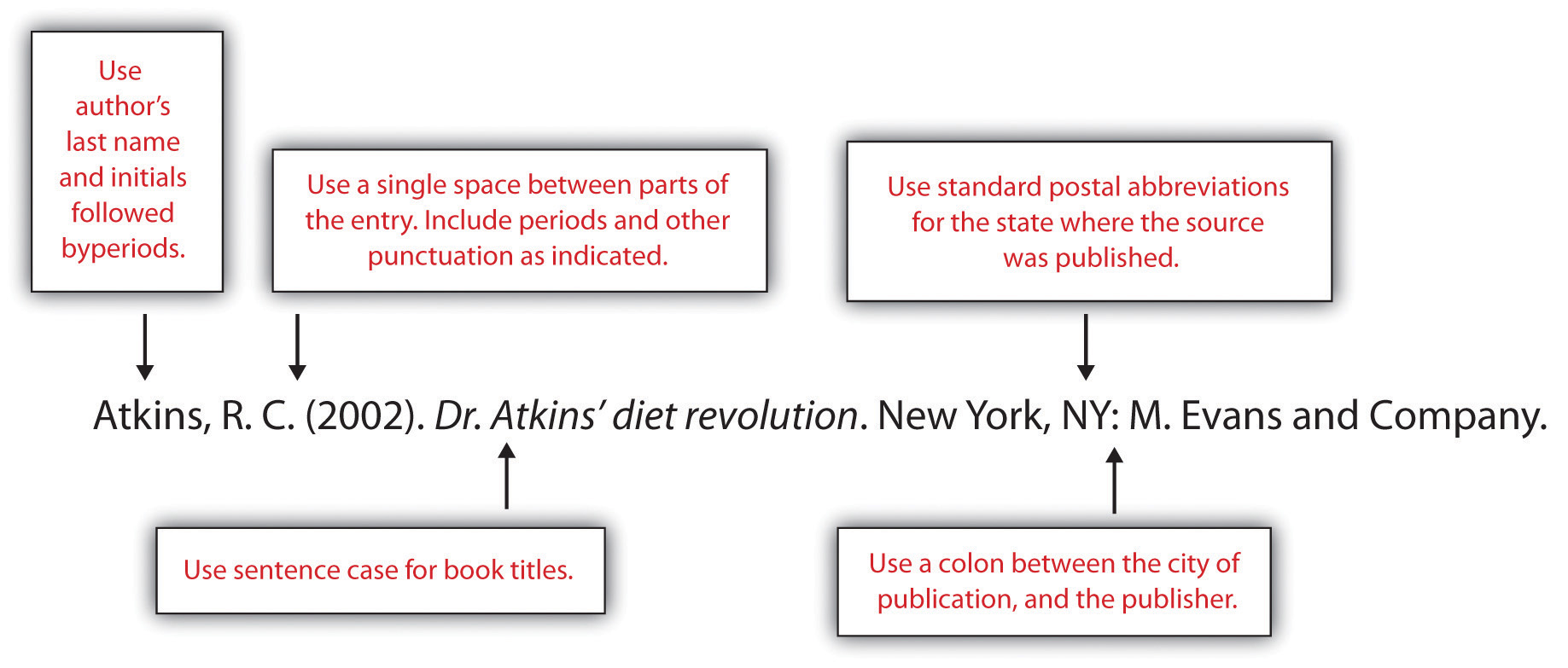

APA (American Psychological Association) Style

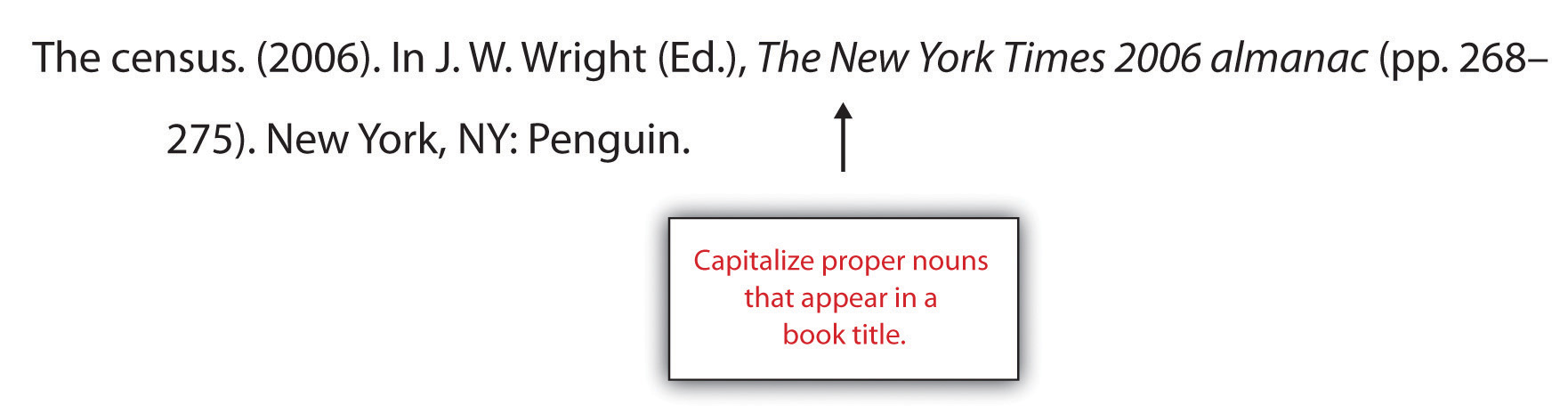

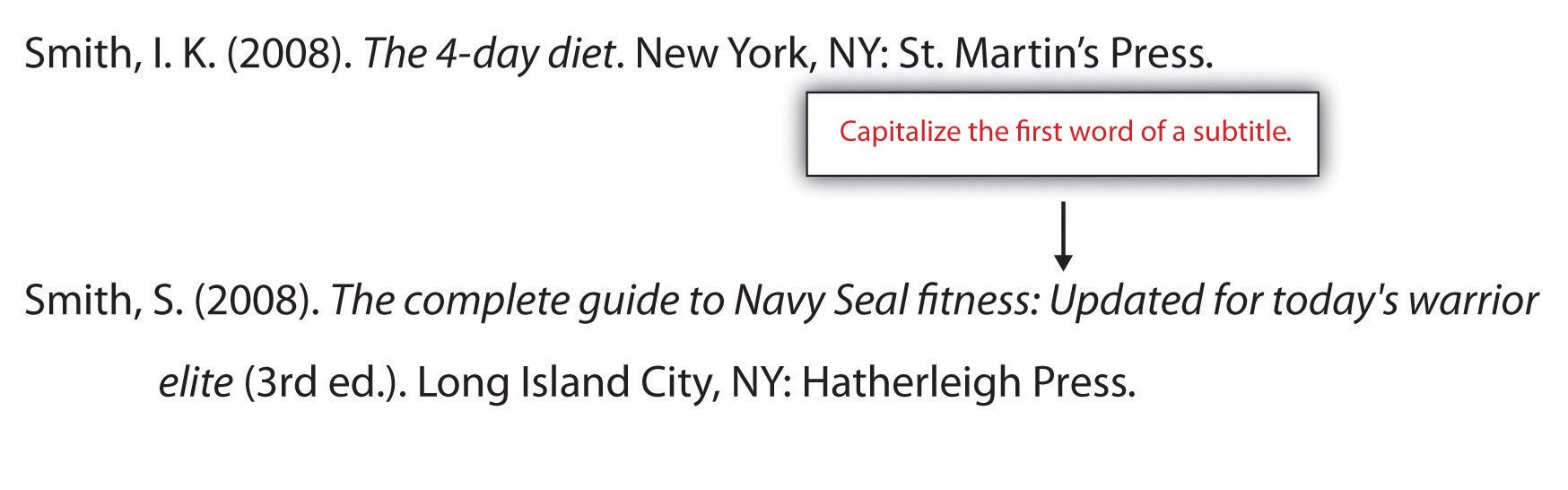

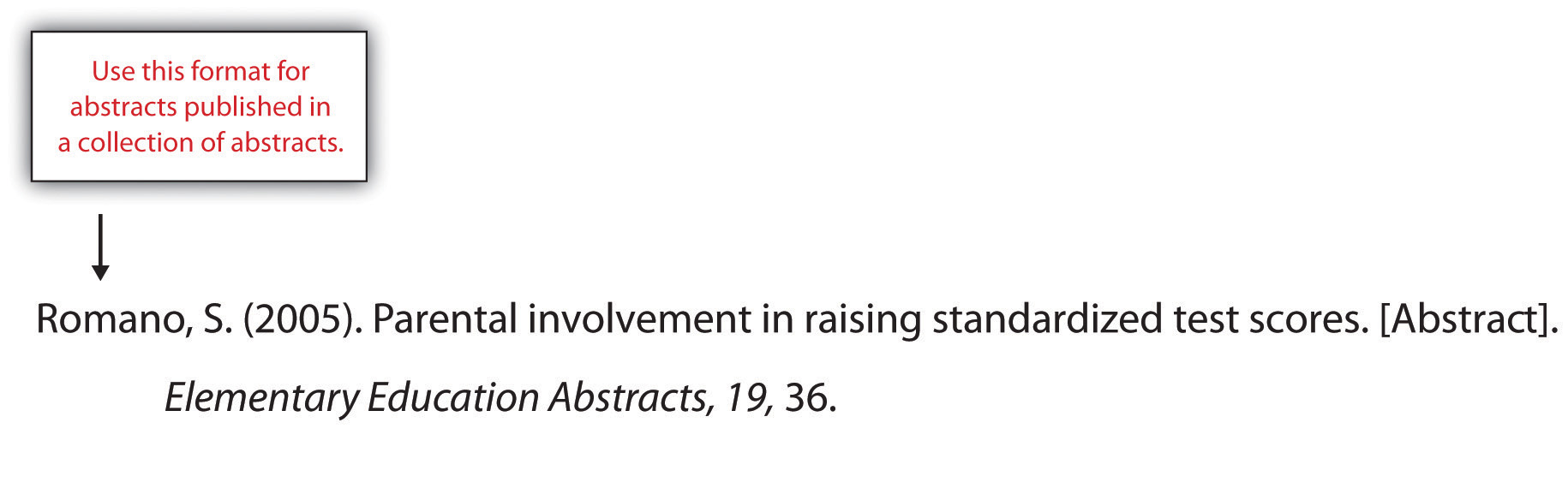

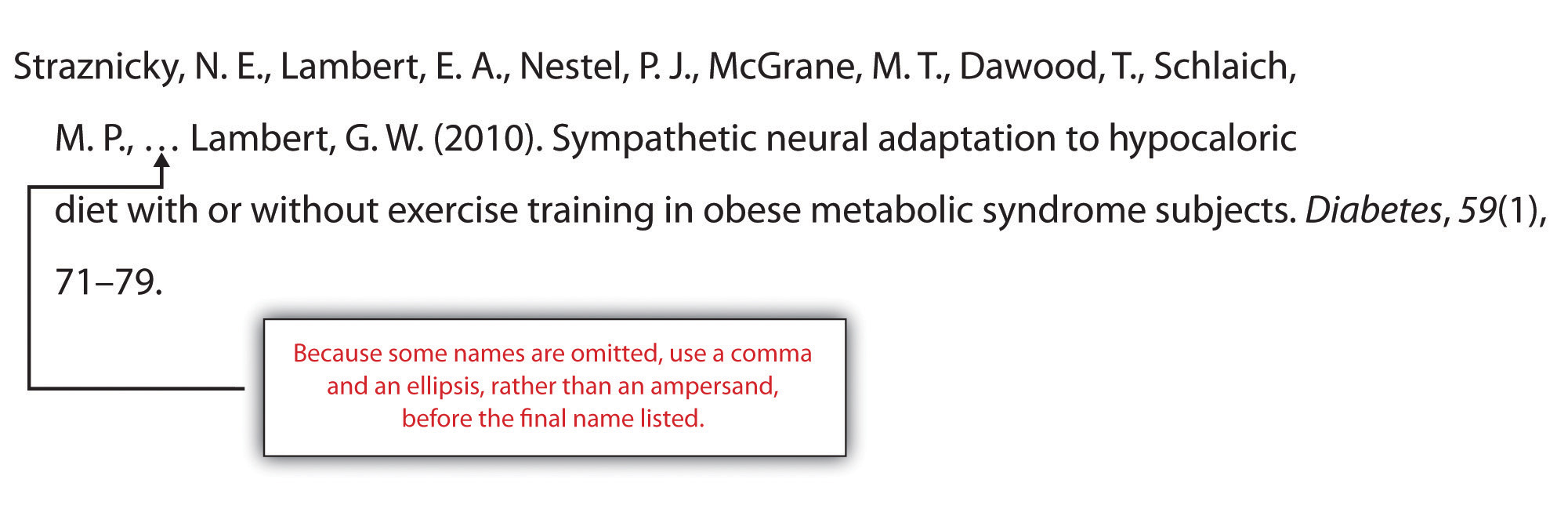

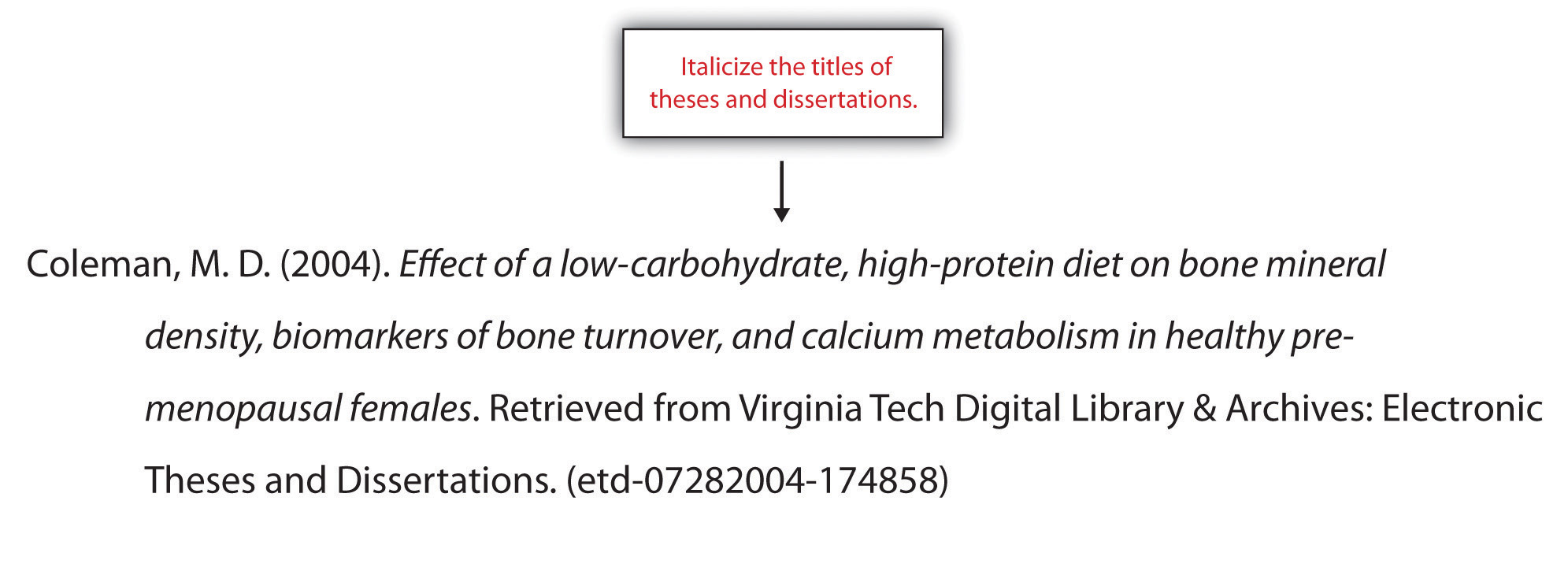

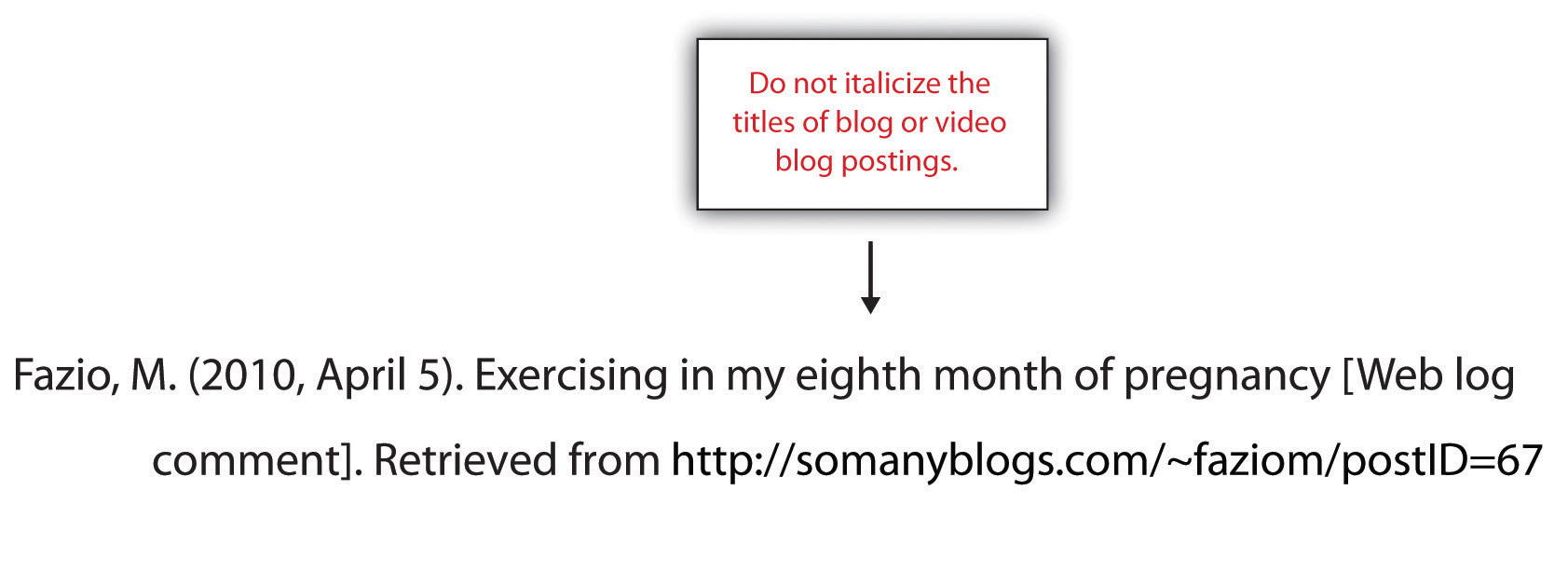

The APA (American Psychological Association) Style has specific guidelines for formatting references used in academic papers, articles, and books. Here are the different reference formats in APA style with examples:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Smith, J. K. (2005). The psychology of social interaction. Wiley-Blackwell.

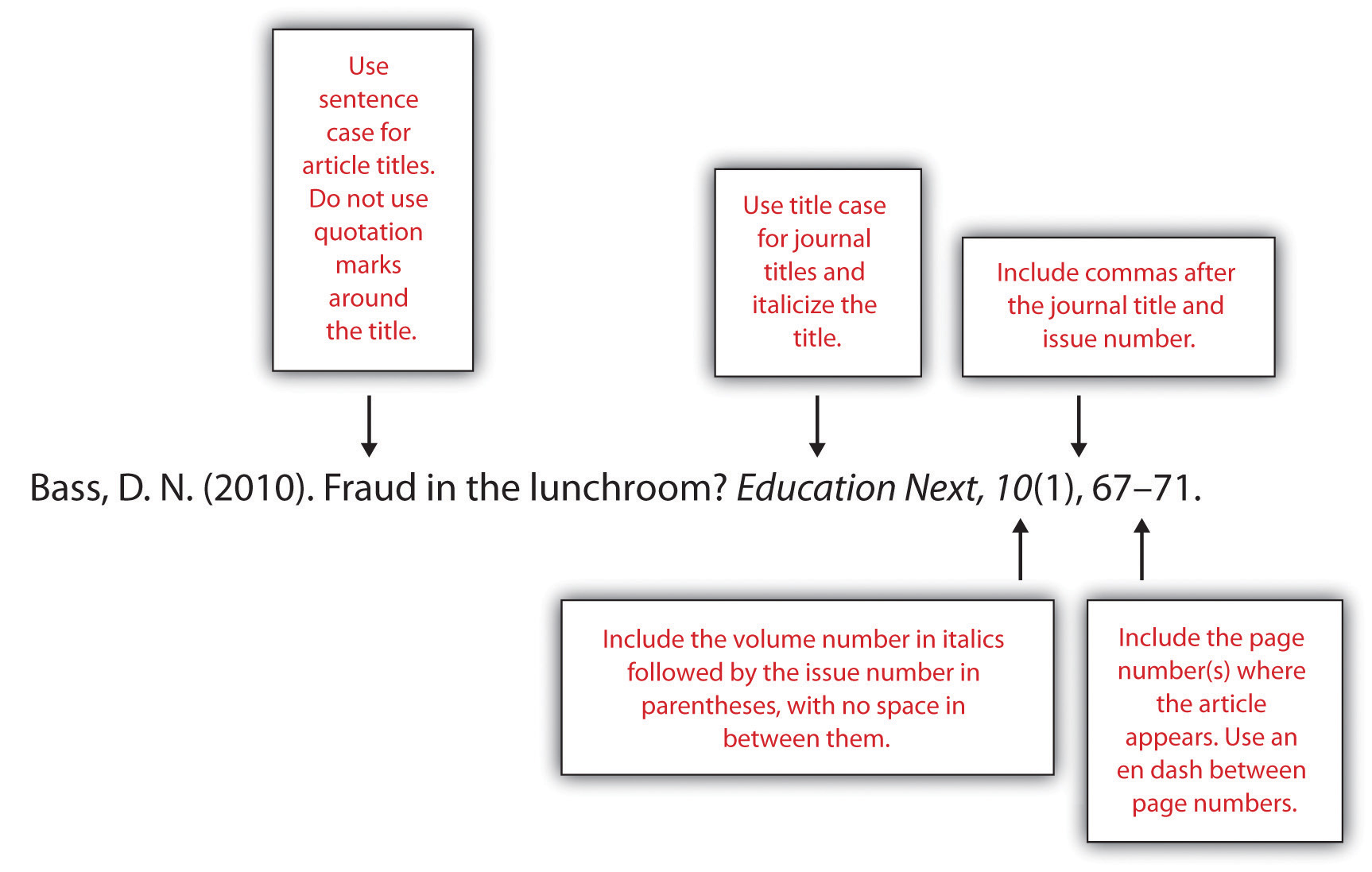

Journal Article

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Brown, L. M., Keating, J. G., & Jones, S. M. (2012). The role of social support in coping with stress among African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 218-233.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication or last update). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 11). COVID-19: How to protect yourself and others. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

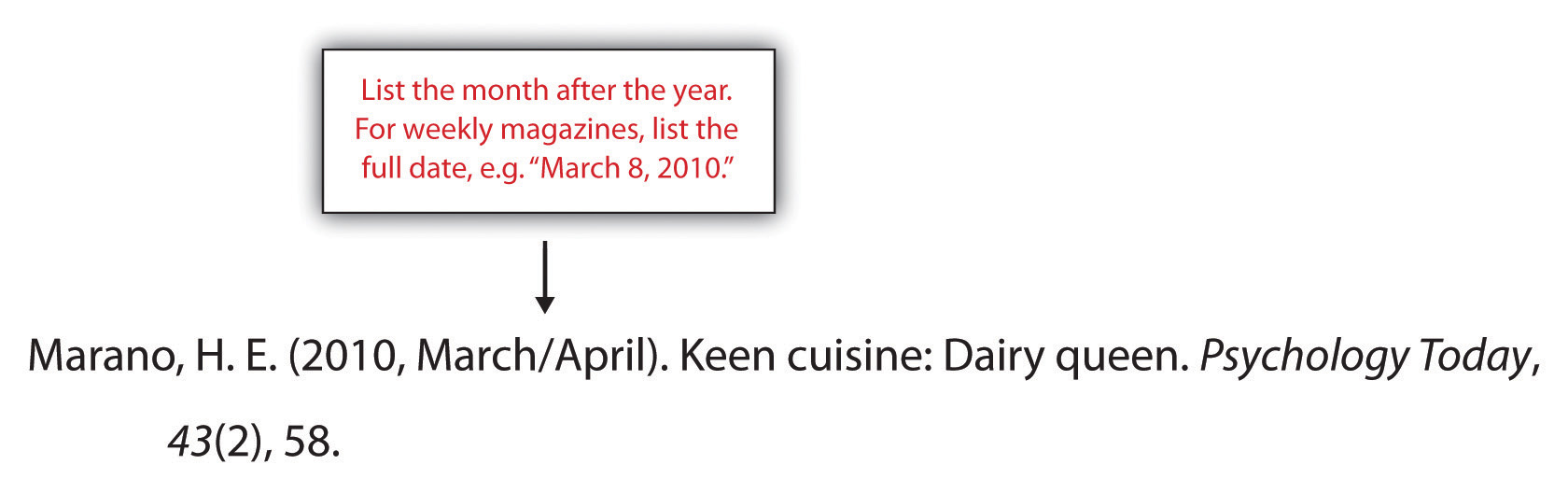

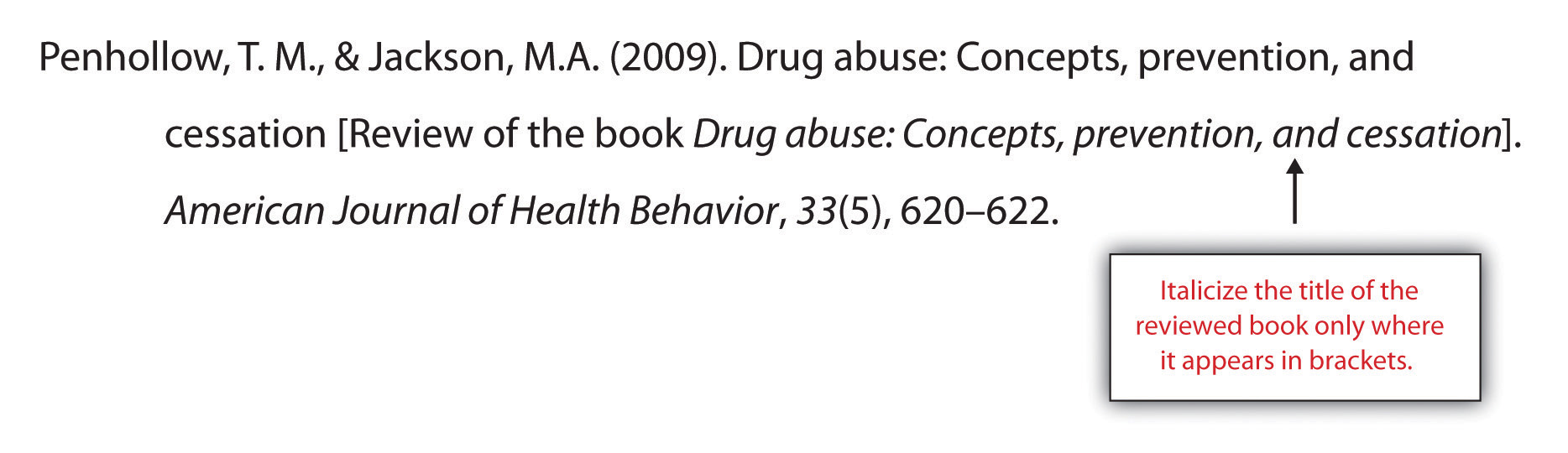

Magazine article

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Magazine, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. (2019, March 11). The power of positive thinking. Psychology Today, 52(3), 60-65.

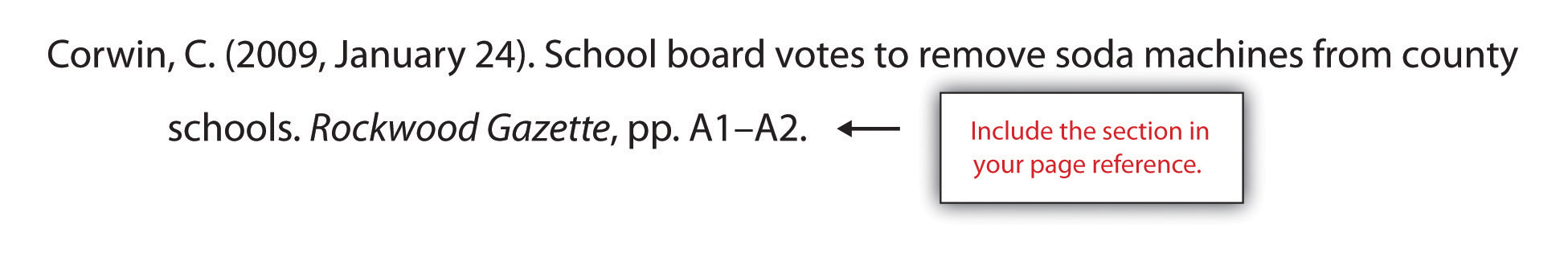

Newspaper article:

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Newspaper, page numbers.

Example: Johnson, B. (2021, February 15). New study shows benefits of exercise on mental health. The New York Times, A8.

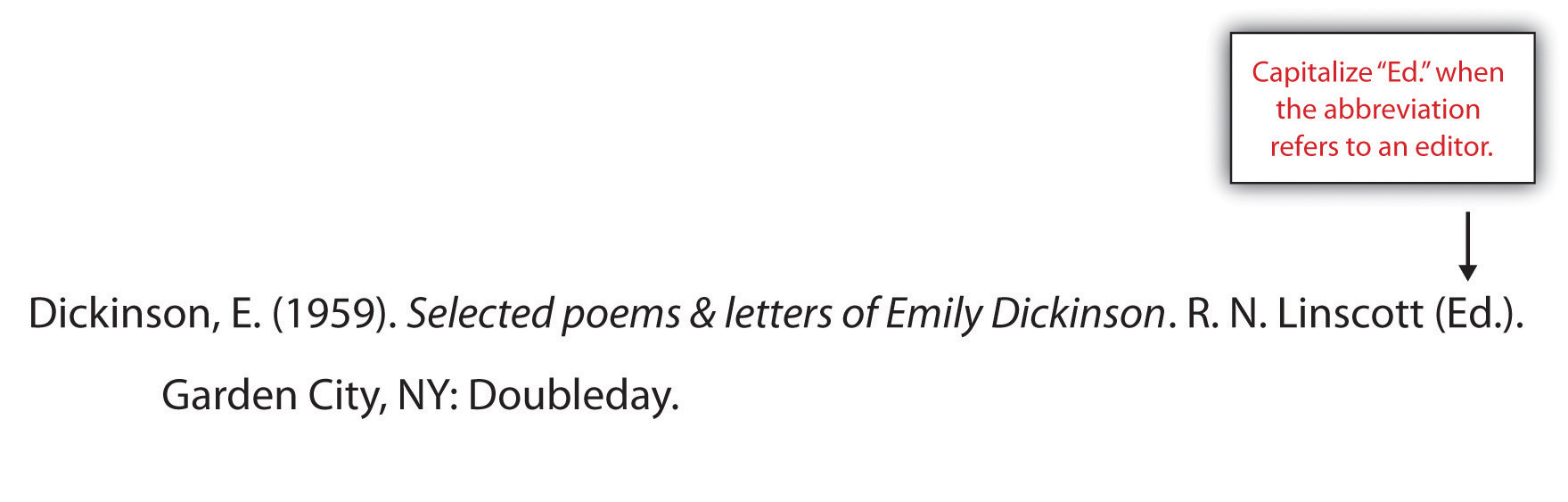

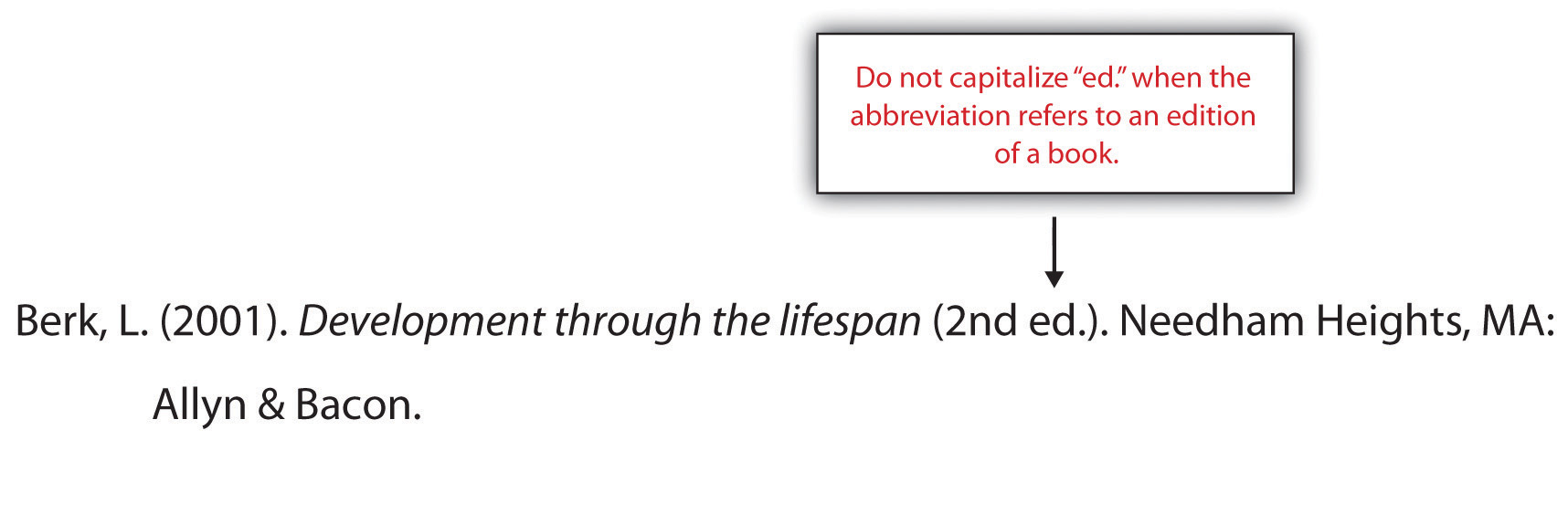

Edited book

Editor, E. E. (Ed.). (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Thompson, J. P. (Ed.). (2014). Social work in the 21st century. Sage Publications.

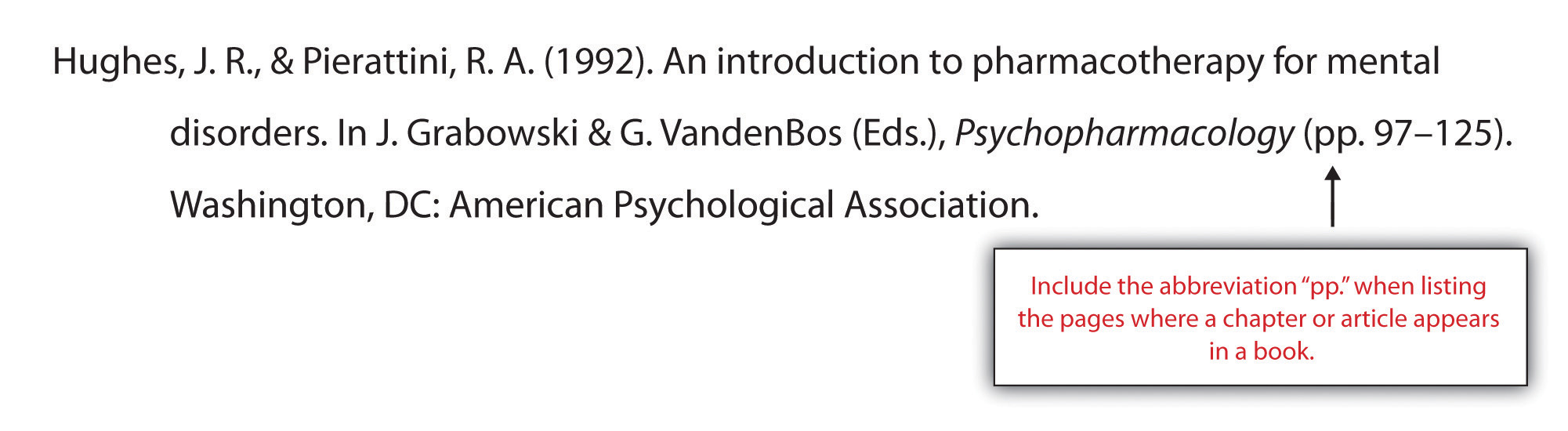

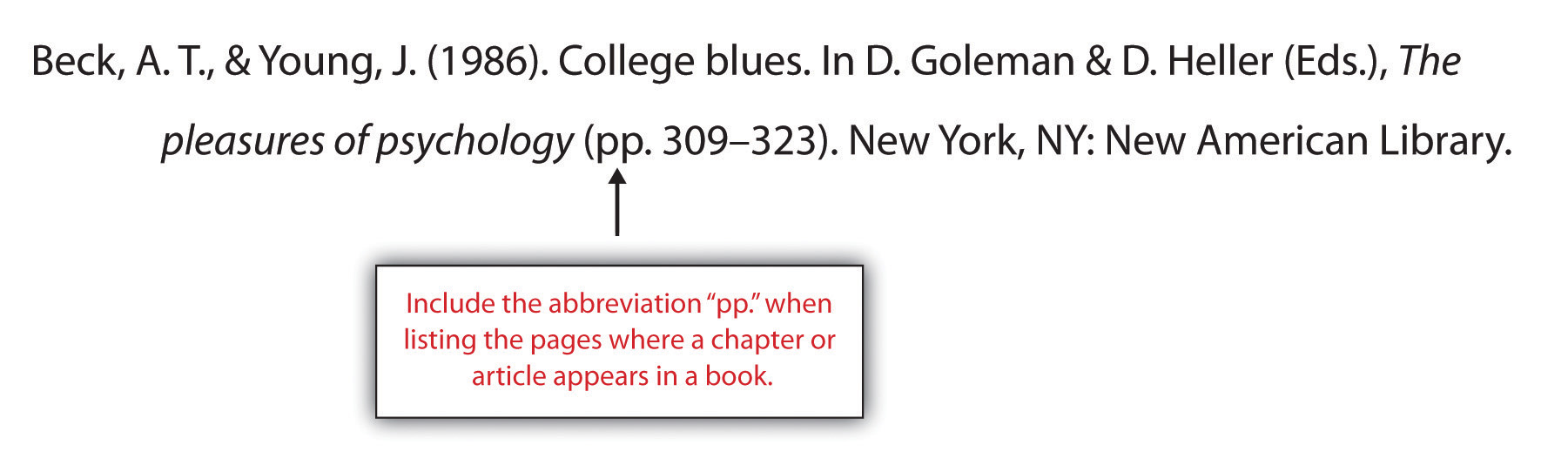

Chapter in an edited book:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of chapter. In E. E. Editor (Ed.), Title of book (pp. page numbers). Publisher.

Example : Johnson, K. S. (2018). The future of social work: Challenges and opportunities. In J. P. Thompson (Ed.), Social work in the 21st century (pp. 105-118). Sage Publications.

MLA (Modern Language Association) Style

The MLA (Modern Language Association) Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the humanities. Here are the different reference formats in MLA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Smith, John. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Journal article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, volume number, issue number, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., et al. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 22, no. 1, 2012, pp. 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name, Publication date, URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC, 11 Dec. 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, Mar. 2019, pp. 60-65.

Newspaper article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, 15 Feb. 2021, p. A8.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Thompson, John P., editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Chapter in an edited book

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last name, Publisher, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, Sage Publications, 2014, pp. 105-118.

Chicago Manual of Style

The Chicago Manual of Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers, dissertations, and books in the humanities and social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Chicago style:

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Publication year): page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. Publication date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Sage Publications, 2014.

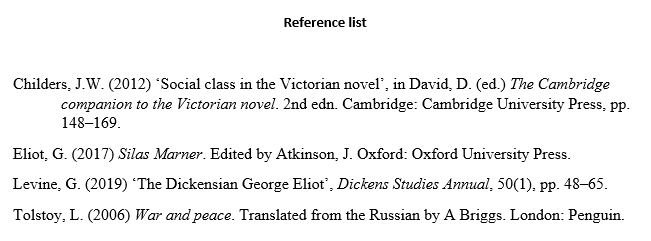

Harvard Style

The Harvard Style, also known as the Author-Date System, is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Harvard Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2005. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number (issue number): page numbers.

Example: Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. 2012. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22 (1): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL. Accessed date.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, month and date of publication.

Example : Smith, Mary. 2019. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, month and date of publication.

Example : Johnson, Bob. 2021. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. 2014. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. 2014. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Vancouver Style

The Vancouver Style, also known as the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals, is a widely used style for writing academic papers in the biomedical sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Vancouver Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title. Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Example : Brown LM, Keating JG, Jones SM. The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents. J Res Adolesc. 2012;22(1):218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name [Internet]. Publication date. [cited date]. Available from: URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others [Internet]. 2020 Dec 11. [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Magazine. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Smith M. The Power of Positive Thinking. Psychology Today. 2019 Mar 1:32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Johnson B. New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health. The New York Times. 2021 Feb 15:A4.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Chapter. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. page numbers.

Example : Johnson KS. The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. p. 105-118.

Turabian Style

Turabian style is a variation of the Chicago style used in academic writing, particularly in the fields of history and humanities. Here are the different reference formats in Turabian style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Year of publication): page numbers.

Example : Brown, LM, Keating, JG, Jones, SM. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” J Res Adolesc 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Publication date. Accessed date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Month Day, Year of publication, page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 1, 2019, 32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Month Day, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, B. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Thompson, JP, ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s Last name, First name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, KS. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by Thompson, JP, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Style

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) style is commonly used in engineering, computer science, and other technical fields. Here are the different reference formats in IEEE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Oppenheim, A. V., & Schafer, R. W. Discrete-Time Signal Processing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Abbreviated Journal Title, vol. number, no. issue number, pp. page numbers, Month year of publication.

Example: Shannon, C. E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379-423, July 1948.

Conference paper

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Paper.” In Title of Conference Proceedings, Place of Conference, Date of Conference, pp. page numbers, Year of publication.

Example: Gupta, S., & Kumar, P. “An Improved System of Linear Discriminant Analysis for Face Recognition.” In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, Harbin, China, Dec. 2011, pp. 144-147.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Date of publication or last update. Accessed date. URL.

Example : National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “Apollo 11.” NASA. July 20, 1969. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/apollo11.html.

Technical report

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Report.” Name of Institution or Organization, Report number, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, J. R. “Development of a New Solar Panel Technology.” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL/TP-6A20-51645, 2011.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Patent.” Patent number, Issue date.

Example : Suzuki, H. “Method of Producing Carbon Nanotubes.” US Patent 7,151,019, December 19, 2006.

Standard Title. Standard number, Publication date.

Example : IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic. IEEE Std 754-2008, August 29, 2008

ACS (American Chemical Society) Style

ACS (American Chemical Society) style is commonly used in chemistry and related fields. Here are the different reference formats in ACS style:

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title Year, Volume, Page Numbers.

Example : Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.; Ma, Y. Facile Preparation of Fe3O4/graphene Composites Using a Hydrothermal Method for High-Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2715-2721.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication.

Example : Carey, F. A. Organic Chemistry; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2008.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In Book Title; Editor’s Last name, First name, Ed.; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume number, Chapter number, Page Numbers.

Example : Grossman, R. B. Analytical Chemistry of Aerosols. In Aerosol Measurement: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Baron, P. A.; Willeke, K., Eds.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 2001; Chapter 10, pp 395-424.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name, URL (accessed date).

Example : National Institute of Standards and Technology. Atomic Spectra Database. https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database (accessed April 1, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Patent Number. Patent Date.

Example : Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W. US Patent 9,999,999, December 31, 2022.

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. In Title of Conference Proceedings, Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume Number, Page Numbers.

Example : Jia, H.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Huang, X. Fast Adsorption of Organic Pollutants by Graphene Oxide. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2017; Volume 1, pp 223-228.

AMA (American Medical Association) Style

AMA (American Medical Association) style is commonly used in medical and scientific fields. Here are the different reference formats in AMA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Article Title. Journal Abbreviation. Year; Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example : Jones, R. A.; Smith, B. C. The Role of Vitamin D in Maintaining Bone Health. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1765-1773.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Guyton, A. C.; Hall, J. E. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: Page Numbers.

Example: Rajakumar, K. Vitamin D and Bone Health. In: Holick, M. F., ed. Vitamin D: Physiology, Molecular Biology, and Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:211-222.

Author’s Last name, First name. Webpage Title. Website Name. URL. Published date. Updated date. Accessed date.

Example : National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)–Patient Version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-prevention-pdq. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Conference presentation title. In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Place of Conference.

Example : Smith, J. R. Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Meta-Analysis. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; September 20-23, 2022; San Diego, CA.

Thesis or dissertation

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Thesis or Dissertation. Degree level [Doctoral dissertation or Master’s thesis]. University Name; Year.

Example : Wilson, S. A. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Bone Health in Postmenopausal Women [Doctoral dissertation]. University of California, Los Angeles; 2018.

ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) Style

The ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) style is commonly used in civil engineering fields. Here are the different reference formats in ASCE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title, volume number, issue number (year): page numbers. DOI or URL (if available).

Example : Smith, J. R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering, vol. 146, no. 3 (2020): 04020010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001668.

Example : McCuen, R. H. Hydrologic Analysis and Design. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2013.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example : Maidment, D. R. “Floodplain Management in the United States.” In: Shroder, J. F., ed. Treatise on Geomorphology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2013: 447-460.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example: Smith, J. R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019: 156-163.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Hurricane Sandy Coastal Risk Reduction Program, New York and New Jersey.” Report No. P-15-001. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; 2015.

CSE (Council of Science Editors) Style

The CSE (Council of Science Editors) style is commonly used in the scientific and medical fields. Here are the different reference formats in CSE style:

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Year;Volume(Issue):Page numbers.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2020;146(3):04020010.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial., ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year:Page numbers.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Bluebook Style

The Bluebook style is commonly used in the legal field for citing legal documents and sources. Here are the different reference formats in Bluebook style:

Case citation

Case name, volume source page (Court year).

Example : Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Statute citation

Name of Act, volume source § section number (year).

Example : Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7401 (1963).

Regulation citation

Name of regulation, volume source § section number (year).

Example: Clean Air Act, 40 C.F.R. § 52.01 (2019).

Book citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number (if applicable). Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example: Smith, J.R. Legal Writing and Analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers; 2015.

Journal article citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Volume number (year): first page-last page.

Example: Garcia, C. “The Right to Counsel: An International Comparison.” International Journal of Legal Information. 43 (2015): 63-94.

Website citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed month day, year).

Example : United Nations. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Oxford Style

The Oxford style, also known as the Oxford referencing system or the documentary-note citation system, is commonly used in the humanities, including literature, history, and philosophy. Here are the different reference formats in Oxford style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The Art of Writing. New York: Penguin, 2020.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue (year): page range.

Example: Garcia, Carlos. “The Role of Ethics in Philosophy.” Philosophy Today 67, no. 3 (2019): 53-68.

Chapter in an edited book citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Lee, Mary. “Feminism in the 21st Century.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed 3 January 2023).

Dissertation or thesis citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name, Year of Publication.

Example : Brown, Susan. “The Art of Storytelling in American Literature.” PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020.

Newspaper article citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day, Year.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. “New Developments in Climate Change Research.” The Guardian, September 15, 2022.

AAA (American Anthropological Association) Style

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) style is commonly used in anthropology research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AAA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2019. The Anthropology of Food. New York: Routledge.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue: page range.

Example : Garcia, Carlos. 2021. “The Role of Ethics in Anthropology.” American Anthropologist 123, no. 2: 237-251.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example: Lee, Mary. 2018. “Feminism in Anthropology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name.

Example : Brown, Susan. 2022. “The Art of Storytelling in Anthropology.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. 2021. “New Developments in Anthropology Research.” The Guardian, September 15.

AIP (American Institute of Physics) Style

The American Institute of Physics (AIP) style is commonly used in physics research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AIP style:

Example : Johnson, S. D. 2021. “Quantum Computing and Information.” Journal of Applied Physics 129, no. 4: 043102.

Example : Feynman, Richard. 2018. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. New York: Basic Books.

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Future of Quantum Computing.” In The Handbook of Physics, edited by John Smith, 125-136. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Conference proceedings citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Paper.” Proceedings of Conference Name, date and location: page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Chen, Wei. 2019. “The Applications of Nanotechnology in Solar Cells.” Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Nanotechnology, July 15-17, Tokyo, Japan: 224-229. New York: AIP Publishing.

Example : American Institute of Physics. 2022. “About AIP Publishing.” AIP Publishing. https://publishing.aip.org/about-aip-publishing/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Patent citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Patent Number.

Example : Smith, John. 2018. US Patent 9,873,644.

References Writing Guide

Here are some general guidelines for writing references:

- Follow the citation style guidelines: Different disciplines and journals may require different citation styles (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). It is important to follow the specific guidelines for the citation style required.

- Include all necessary information : Each citation should include enough information for readers to locate the source. For example, a journal article citation should include the author(s), title of the article, journal title, volume number, issue number, page numbers, and publication year.

- Use proper formatting: Citation styles typically have specific formatting requirements for different types of sources. Make sure to follow the proper formatting for each citation.

- Order citations alphabetically: If listing multiple sources, they should be listed alphabetically by the author’s last name.

- Be consistent: Use the same citation style throughout the entire paper or project.

- Check for accuracy: Double-check all citations to ensure accuracy, including correct spelling of author names and publication information.

- Use reputable sources: When selecting sources to cite, choose reputable and authoritative sources. Avoid sources that are biased or unreliable.

- Include all sources: Make sure to include all sources used in the research, including those that were not directly quoted but still informed the work.

- Use online tools : There are online tools available (e.g., citation generators) that can help with formatting and organizing references.

Purpose of References in Research

References in research serve several purposes:

- To give credit to the original authors or sources of information used in the research. It is important to acknowledge the work of others and avoid plagiarism.

- To provide evidence for the claims made in the research. References can support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research by citing relevant studies, data, or theories.

- To allow readers to find and verify the sources used in the research. References provide the necessary information for readers to locate and access the sources cited in the research, which allows them to evaluate the quality and reliability of the information presented.

- To situate the research within the broader context of the field. References can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge, and can help readers to identify gaps in the literature that the research seeks to address.

Importance of References in Research

References play an important role in research for several reasons:

- Credibility : By citing authoritative sources, references lend credibility to the research and its claims. They provide evidence that the research is based on a sound foundation of knowledge and has been carefully researched.

- Avoidance of Plagiarism : References help researchers avoid plagiarism by giving credit to the original authors or sources of information. This is important for ethical reasons and also to avoid legal repercussions.

- Reproducibility : References allow others to reproduce the research by providing detailed information on the sources used. This is important for verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References provide context for the research by situating it within the broader body of knowledge in the field. They help researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : References provide a means for others to evaluate the research by allowing them to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

Advantages of References in Research

There are several advantages of including references in research:

- Acknowledgment of Sources: Including references gives credit to the authors or sources of information used in the research. This is important to acknowledge the original work and avoid plagiarism.

- Evidence and Support : References can provide evidence to support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research. This can add credibility and strength to the research.

- Reproducibility : References provide the necessary information for others to reproduce the research. This is important for the verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References can help to situate the research within the broader body of knowledge in the field. This helps researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : Including references allows others to evaluate the research by providing a means to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

- Ongoing Conversation: References allow researchers to engage in ongoing conversations and debates within their fields. They can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

- Manuscript Preparation

How to write your references quickly and easily

- 3 minute read

- 229.6K views

Table of Contents

Every scientific paper builds on previous research – even if it’s in a new field, related studies will have preceded and informed it. In peer-reviewed articles, authors must give credit to this previous research, through citations and references. Not only does this show clearly where the current research came from, but it also helps readers understand the content of the paper better.

There is no optimum number of references for an academic article but depending on the subject you could be dealing with more than 100 different papers, conference reports, video articles, medical guidelines or any number of other resources.

That’s a lot of content to manage. Before submitting your manuscript, this needs to be checked, cross-references in the text and the list, organized and formatted.

The exact content and format of the citations and references in your paper will depend on the journal you aim to publish in, so the first step is to check the journal’s Guide for Authors before you submit.

There are two main points to pay attention to – consistency and accuracy. When you go through your manuscript to edit or proofread it, look closely at the citations within the text. Are they all the same? For example, if the journal prefers the citations to be in the format (name, year), make sure they’re all the same: (Smith, 2016).

Your citations must also be accurate and complete. Do they match your references list? Each citation should be included in the list, so cross-checking is important. It’s also common for journals to prefer that most, if not all, of the articles listed in your references be cited within the text – after all, these should be studies that contributed to the knowledge underpinning your work, not just your bedtime reading. So go through them carefully, noting any missing references or citations and filling the gaps.

Each journal has its own requirements when it comes to the content and format of references, as well as where and how you should include them in your submission, so double-check before you hit send!

In general, a reference will include authors’ names and initials, the title of the article, name of the journal, volume and issue, date, page numbers and DOI. On ScienceDirect, articles are linked to their original source (if also published on ScienceDirect) or to their Scopus record, so including the DOI can help link to the correct article.

A spotless reference list

Luckily, compiling and editing the references in your scientific manuscript can be easy – and it no longer has to be manual. Management tools like Mendeley can keep track of all your references, letting you share them with your collaborators. With the Word plugin, it’s possible to select the right citation style for the journal you’re submitting to and the tool will format your references automatically.

Like with any other part of your manuscript, it’s important to make sure your reference list has been checked and edited. Elsevier Author Services Language Editing can help, with professional manuscript editing that will help make sure your references don’t hold you back from publication.

Why it’s best to ask a professional when it comes to translation

- Research Process

How to Choose a Journal to Submit an Article

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Reference List: Common Reference List Examples

Article (with doi).

Alvarez, E., & Tippins, S. (2019). Socialization agents that Puerto Rican college students use to make financial decisions. Journal of Social Change , 11 (1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.5590/JOSC.2019.11.1.07

Laplante, J. P., & Nolin, C. (2014). Consultas and socially responsible investing in Guatemala: A case study examining Maya perspectives on the Indigenous right to free, prior, and informed consent. Society & Natural Resources , 27 , 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2013.861554

Use the DOI number for the source whenever one is available. DOI stands for "digital object identifier," a number specific to the article that can help others locate the source. In APA 7, format the DOI as a web address. Active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list. Also see our Quick Answer FAQ, "Can I use the DOI format provided by library databases?"

Jerrentrup, A., Mueller, T., Glowalla, U., Herder, M., Henrichs, N., Neubauer, A., & Schaefer, J. R. (2018). Teaching medicine with the help of “Dr. House.” PLoS ONE , 13 (3), Article e0193972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193972

For journal articles that are assigned article numbers rather than page ranges, include the article number in place of the page range.

For more on citing electronic resources, see Electronic Sources References .

Article (Without DOI)

Found in a common academic research database or in print.

Casler , T. (2020). Improving the graduate nursing experience through support on a social media platform. MEDSURG Nursing , 29 (2), 83–87.

If an article does not have a DOI and you retrieved it from a common academic research database through the university library, there is no need to include any additional electronic retrieval information. The reference list entry looks like the entry for a print copy of the article. (This format differs from APA 6 guidelines that recommended including the URL of a journal's homepage when the DOI was not available.) Note that APA 7 has additional guidance on reference list entries for articles found only in specific databases or archives such as Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, UpToDate, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and university archives. See APA 7, Section 9.30 for more information.

Found on an Open Access Website

Eaton, T. V., & Akers, M. D. (2007). Whistleblowing and good governance. CPA Journal , 77 (6), 66–71. http://archives.cpajournal.com/2007/607/essentials/p58.htm

Provide the direct web address/URL to a journal article found on the open web, often on an open access journal's website. In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Weinstein, J. A. (2010). Social change (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

If the book has an edition number, include it in parentheses after the title of the book. If the book does not list any edition information, do not include an edition number. The edition number is not italicized.

American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.).

If the author and publisher are the same, only include the author in its regular place and omit the publisher.

Lencioni, P. (2012). The advantage: Why organizational health trumps everything else in business . Jossey-Bass. https://amzn.to/343XPSJ

As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, it is no longer necessary to include the ebook format in the title. However, if you listened to an audiobook and the content differs from the text version (e.g., abridged content) or your discussion highlights elements of the audiobook (e.g., narrator's performance), then note that it is an audiobook in the title element in brackets. For ebooks and online audiobooks, also include the DOI number (if available) or nondatabase URL but leave out the electronic retrieval element if the ebook was found in a common academic research database, as with journal articles. APA 7 allows for the shortening of long DOIs and URLs, as shown in this example. See APA 7, Section 9.36 for more information.

Chapter in an Edited Book

Poe, M. (2017). Reframing race in teaching writing across the curriculum. In F. Condon & V. A. Young (Eds.), Performing antiracist pedagogy in rhetoric, writing, and communication (pp. 87–105). University Press of Colorado.

Include the page numbers of the chapter in parentheses after the book title.

Christensen, L. (2001). For my people: Celebrating community through poetry. In B. Bigelow, B. Harvey, S. Karp, & L. Miller (Eds.), Rethinking our classrooms: Teaching for equity and justice (Vol. 2, pp. 16–17). Rethinking Schools.

Also include the volume number or edition number in the parenthetical information after the book title when relevant.

Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, pp. 3-66). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923)

When a text has been republished as part of an anthology collection, after the author’s name include the date of the version that was read. At the end of the entry, place the date of the original publication inside parenthesis along with the note “original work published.” For in-text citations of republished work, use both dates in the parenthetical citation, original date first with a slash separating the years, as in this example: Freud (1923/1961). For more information on reprinted or republished works, see APA 7, Sections 9.40-9.41.

Classroom Resources

Citing classroom resources.

If you need to cite content found in your online classroom, use the author (if there is one listed), the year of publication (if available), the title of the document, and the main URL of Walden classrooms. For example, you are citing study notes titled "Health Effects of Exposure to Forest Fires," but you do not know the author's name, your reference entry will look like this:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

If you do know the author of the document, your reference will look like this:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

A few notes on citing course materials:

- [Lecture notes]

- [Course handout]

- [Study notes]

- It can be difficult to determine authorship of classroom documents. If an author is listed on the document, use that. If the resource is clearly a product of Walden (such as the course-based videos), use Walden University as the author. If you are unsure or if no author is indicated, place the title in the author spot, as above.

- If you cannot determine a date of publication, you can use n.d. (for "no date") in place of the year.

Note: The web location for Walden course materials is not directly retrievable without a password, and therefore, following APA guidelines, use the main URL for the class sites: https://class.waldenu.edu.

Citing Tempo Classroom Resources

Clear author:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Unclear author:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Conference Sessions and Presentations

Feinman, Y. (2018, July 27). Alternative to proctoring in introductory statistics community college courses [Poster presentation]. Walden University Research Symposium, Minneapolis, MN, United States. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/symposium2018/23/

Torgerson, K., Parrill, J., & Haas, A. (2019, April 5-9). Tutoring strategies for online students [Conference session]. The Higher Learning Commission Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, United States. http://onlinewritingcenters.org/scholarship/torgerson-parrill-haas-2019/

Dictionary Entry

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Leadership. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary . Retrieved May 28, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership

When constructing a reference for an entry in a dictionary or other reference work that has no byline (i.e., no named individual authors), use the name of the group—the institution, company, or organization—as author (e.g., Merriam Webster, American Psychological Association, etc.). The name of the entry goes in the title position, followed by "In" and the italicized name of the reference work (e.g., Merriam-Webster.com dictionary , APA dictionary of psychology ). In this instance, APA 7 recommends including a retrieval date as well for this online source since the contents of the page change over time. End the reference entry with the specific URL for the defined word.

Discussion Board Post

Osborne, C. S. (2010, June 29). Re: Environmental responsibility [Discussion post]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Dissertations or Theses

Retrieved From a Database

Nalumango, K. (2019). Perceptions about the asylum-seeking process in the United States after 9/11 (Publication No. 13879844) [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Retrieved From an Institutional or Personal Website

Evener. J. (2018). Organizational learning in libraries at for-profit colleges and universities [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6606&context=dissertations

Unpublished Dissertation or Thesis

Kirwan, J. G. (2005). An experimental study of the effects of small-group, face-to-face facilitated dialogues on the development of self-actualization levels: A movement towards fully functional persons [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center.

For further examples and information, see APA 7, Section 10.6.

Legal Material

For legal references, APA follows the recommendations of The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation , so if you have any questions beyond the examples provided in APA, seek out that resource as well.

Court Decisions

Reference format:

Name v. Name, Volume Reporter Page (Court Date). URL

Sample reference entry:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

Sample citation:

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

Note: Italicize the case name when it appears in the text of your paper.

Name of Act, Title Source § Section Number (Year). URL

Sample reference entry for a federal statute:

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004). https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ446/PLAW-108publ446.pdf

Sample reference entry for a state statute:

Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, Minn. Stat. §§ 148.171 et seq. (2019). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/148.171

Sample citation: Minnesota nurses must maintain current registration in order to practice (Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, 2010).

Note: The § symbol stands for "section." Use §§ for sections (plural). To find this symbol in Microsoft Word, go to "Insert" and click on Symbol." Look in the Latin 1-Supplement subset. Note: U.S.C. stands for "United States Code." Note: The Latin abbreviation " et seq. " means "and what follows" and is used when the act includes the cited section and ones that follow. Note: List the chapter first followed by the section or range of sections.

Unenacted Bills and Resolutions

(Those that did not pass and become law)

Title [if there is one], bill or resolution number, xxx Cong. (year). URL

Sample reference entry for Senate bill:

Anti-Phishing Act, S. 472, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/472

Sample reference entry for House of Representatives resolution:

Anti-Phishing Act, H.R. 1099, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/1099

The Anti-Phishing Act (2005) proposed up to 5 years prison time for people running Internet scams.

These are the three legal areas you may be most apt to cite in your scholarly work. For more examples and explanation, see APA 7, Chapter 11.

Magazine Article

Clay, R. (2008, June). Science vs. ideology: Psychologists fight back about the misuse of research. Monitor on Psychology , 39 (6). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2008/06/ideology

Note that for citations, include only the year: Clay (2008). For magazine articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For magazine articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print magazine, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

Newspaper Article (Retrieved Online)

Baker, A. (2014, May 7). Connecticut students show gains in national tests. New York Times . http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/nyregion/national-assessment-of-educational-progress-results-in-Connecticut-and-New-Jersey.html

Include the full date in the format Year, Month Day. Do not include a retrieval date for periodical sources found on websites. Note that for citations, include only the year: Baker (2014). For newspaper articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For newspaper articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print newspaper, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

Online Video/Webcast

Walden University. (2013). An overview of learning [Video]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Use this format for online videos such as Walden videos in classrooms. Most of our classroom videos are produced by Walden University, which will be listed as the author in your reference and citation. Note: Some examples of audiovisual materials in the APA manual show the word “Producer” in parentheses after the producer/author area. In consultation with the editors of the APA manual, we have determined that parenthetical is not necessary for the videos in our courses. The manual itself is unclear on the matter, however, so either approach should be accepted. Note that the speaker in the video does not appear in the reference list entry, but you may want to mention that person in your text. For instance, if you are viewing a video where Tobias Ball is the speaker, you might write the following: Tobias Ball stated that APA guidelines ensure a consistent presentation of information in student papers (Walden University, 2013). For more information on citing the speaker in a video, see our page on Common Citation Errors .

Taylor, R. [taylorphd07]. (2014, February 27). Scales of measurement [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDsMUlexaMY

Walden University Academic Skills Center. (2020, April 15). One-way ANCOVA: Introduction [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_XnNDQ5CNW8

For videos from streaming sites, use the person or organization who uploaded the video in the author space to ensure retrievability, whether or not that person is the speaker in the video. A username can be provided in square brackets. As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, include the publisher after the title, and do not use "Retrieved from" before the URL. See APA 7, Section 10.12 for more information and examples.

See also reference list entry formats for TED Talks .

Technical and Research Reports

Edwards, C. (2015). Lighting levels for isolated intersections: Leading to safety improvements (Report No. MnDOT 2015-05). Center for Transportation Studies. http://www.cts.umn.edu/Publications/ResearchReports/reportdetail.html?id=2402

Technical and research reports by governmental agencies and other research institutions usually follow a different publication process than scholarly, peer-reviewed journals. However, they present original research and are often useful for research papers. Sometimes, researchers refer to these types of reports as gray literature , and white papers are a type of this literature. See APA 7, Section 10.4 for more information.

Reference list entires for TED Talks follow the usual guidelines for multimedia content found online. There are two common places to find TED talks online, with slightly different reference list entry formats for each.

TED Talk on the TED website

If you find the TED Talk on the TED website, follow the format for an online video on an organizational website:

Owusu-Kesse, K. (2020, June). 5 needs that any COVID-19 response should meet [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/kwame_owusu_kesse_5_needs_that_any_covid_19_response_should_meet

The speaker is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on the TED website. For citations, use the speaker's surname.

TED Talk on YouTube

If you find the TED Talk on YouTube or another streaming video website, follow the usual format for streaming video sites:

TED. (2021, February 5). The shadow pandemic of domestic violence during COVID-19 | Kemi DaSilvalbru [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGdID_ICFII

TED is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on YouTube since it is the channel on which the video is posted. For citations, use TED as the author.

Walden University Course Catalog

To include the Walden course catalog in your reference list, use this format:

Walden University. (2020). 2019-2020 Walden University catalog . https://catalog.waldenu.edu/index.php

If you cite from a specific portion of the catalog in your paper, indicate the appropriate section and paragraph number in your text:

...which reflects the commitment to social change expressed in Walden University's mission statement (Walden University, 2020, Vision, Mission, and Goals section, para. 2).

And in the reference list:

Walden University. (2020). Vision, mission, and goals. In 2019-2020 Walden University catalog. https://catalog.waldenu.edu/content.php?catoid=172&navoid=59420&hl=vision&returnto=search

Vartan, S. (2018, January 30). Why vacations matter for your health . CNN. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/why-vacations-matter/index.html

For webpages on the open web, include the author, date, webpage title, organization/site name, and URL. (There is a slight variation for online versions of print newspapers or magazines. For those sources, follow the models in the previous sections of this page.)

American Federation of Teachers. (n.d.). Community schools . http://www.aft.org/issues/schoolreform/commschools/index.cfm

If there is no specified author, then use the organization’s name as the author. In such a case, there is no need to repeat the organization's name after the title.

In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Common Reference List Examples

Didn't find what you need? Search our website or email us .

Read our website accessibility and accommodation statement .

- Previous Page: Reference List: Overview

- Next Page: Common Military Reference List Examples

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / How to Cite Sources

How to Cite Sources

Here is a complete list for how to cite sources. Most of these guides present citation guidance and examples in MLA, APA, and Chicago.

If you’re looking for general information on MLA or APA citations , the EasyBib Writing Center was designed for you! It has articles on what’s needed in an MLA in-text citation , how to format an APA paper, what an MLA annotated bibliography is, making an MLA works cited page, and much more!

MLA Format Citation Examples

The Modern Language Association created the MLA Style, currently in its 9th edition, to provide researchers with guidelines for writing and documenting scholarly borrowings. Most often used in the humanities, MLA style (or MLA format ) has been adopted and used by numerous other disciplines, in multiple parts of the world.

MLA provides standard rules to follow so that most research papers are formatted in a similar manner. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the information. The MLA in-text citation guidelines, MLA works cited standards, and MLA annotated bibliography instructions provide scholars with the information they need to properly cite sources in their research papers, articles, and assignments.

- Book Chapter

- Conference Paper

- Documentary

- Encyclopedia

- Google Images

- Kindle Book

- Memorial Inscription

- Museum Exhibit

- Painting or Artwork

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Sheet Music

- Thesis or Dissertation

- YouTube Video

APA Format Citation Examples

The American Psychological Association created the APA citation style in 1929 as a way to help psychologists, anthropologists, and even business managers establish one common way to cite sources and present content.

APA is used when citing sources for academic articles such as journals, and is intended to help readers better comprehend content, and to avoid language bias wherever possible. The APA style (or APA format ) is now in its 7th edition, and provides citation style guides for virtually any type of resource.

Chicago Style Citation Examples

The Chicago/Turabian style of citing sources is generally used when citing sources for humanities papers, and is best known for its requirement that writers place bibliographic citations at the bottom of a page (in Chicago-format footnotes ) or at the end of a paper (endnotes).

The Turabian and Chicago citation styles are almost identical, but the Turabian style is geared towards student published papers such as theses and dissertations, while the Chicago style provides guidelines for all types of publications. This is why you’ll commonly see Chicago style and Turabian style presented together. The Chicago Manual of Style is currently in its 17th edition, and Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations is in its 8th edition.

Citing Specific Sources or Events

- Declaration of Independence

- Gettysburg Address

- Martin Luther King Jr. Speech

- President Obama’s Farewell Address

- President Trump’s Inauguration Speech

- White House Press Briefing

Additional FAQs

- Citing Archived Contributors

- Citing a Blog

- Citing a Book Chapter

- Citing a Source in a Foreign Language

- Citing an Image

- Citing a Song

- Citing Special Contributors

- Citing a Translated Article

- Citing a Tweet

6 Interesting Citation Facts

The world of citations may seem cut and dry, but there’s more to them than just specific capitalization rules, MLA in-text citations , and other formatting specifications. Citations have been helping researches document their sources for hundreds of years, and are a great way to learn more about a particular subject area.

Ever wonder what sets all the different styles apart, or how they came to be in the first place? Read on for some interesting facts about citations!

1. There are Over 7,000 Different Citation Styles

You may be familiar with MLA and APA citation styles, but there are actually thousands of citation styles used for all different academic disciplines all across the world. Deciding which one to use can be difficult, so be sure to ask you instructor which one you should be using for your next paper.

2. Some Citation Styles are Named After People

While a majority of citation styles are named for the specific organizations that publish them (i.e. APA is published by the American Psychological Association, and MLA format is named for the Modern Language Association), some are actually named after individuals. The most well-known example of this is perhaps Turabian style, named for Kate L. Turabian, an American educator and writer. She developed this style as a condensed version of the Chicago Manual of Style in order to present a more concise set of rules to students.

3. There are Some Really Specific and Uniquely Named Citation Styles

How specific can citation styles get? The answer is very. For example, the “Flavour and Fragrance Journal” style is based on a bimonthly, peer-reviewed scientific journal published since 1985 by John Wiley & Sons. It publishes original research articles, reviews and special reports on all aspects of flavor and fragrance. Another example is “Nordic Pulp and Paper Research,” a style used by an international scientific magazine covering science and technology for the areas of wood or bio-mass constituents.

4. More citations were created on EasyBib.com in the first quarter of 2018 than there are people in California.

The US Census Bureau estimates that approximately 39.5 million people live in the state of California. Meanwhile, about 43 million citations were made on EasyBib from January to March of 2018. That’s a lot of citations.

5. “Citations” is a Word With a Long History

The word “citations” can be traced back literally thousands of years to the Latin word “citare” meaning “to summon, urge, call; put in sudden motion, call forward; rouse, excite.” The word then took on its more modern meaning and relevance to writing papers in the 1600s, where it became known as the “act of citing or quoting a passage from a book, etc.”

6. Citation Styles are Always Changing

The concept of citations always stays the same. It is a means of preventing plagiarism and demonstrating where you relied on outside sources. The specific style rules, however, can and do change regularly. For example, in 2018 alone, 46 new citation styles were introduced , and 106 updates were made to exiting styles. At EasyBib, we are always on the lookout for ways to improve our styles and opportunities to add new ones to our list.

Why Citations Matter

Here are the ways accurate citations can help your students achieve academic success, and how you can answer the dreaded question, “why should I cite my sources?”

They Give Credit to the Right People

Citing their sources makes sure that the reader can differentiate the student’s original thoughts from those of other researchers. Not only does this make sure that the sources they use receive proper credit for their work, it ensures that the student receives deserved recognition for their unique contributions to the topic. Whether the student is citing in MLA format , APA format , or any other style, citations serve as a natural way to place a student’s work in the broader context of the subject area, and serve as an easy way to gauge their commitment to the project.

They Provide Hard Evidence of Ideas

Having many citations from a wide variety of sources related to their idea means that the student is working on a well-researched and respected subject. Citing sources that back up their claim creates room for fact-checking and further research . And, if they can cite a few sources that have the converse opinion or idea, and then demonstrate to the reader why they believe that that viewpoint is wrong by again citing credible sources, the student is well on their way to winning over the reader and cementing their point of view.

They Promote Originality and Prevent Plagiarism

The point of research projects is not to regurgitate information that can already be found elsewhere. We have Google for that! What the student’s project should aim to do is promote an original idea or a spin on an existing idea, and use reliable sources to promote that idea. Copying or directly referencing a source without proper citation can lead to not only a poor grade, but accusations of academic dishonesty. By citing their sources regularly and accurately, students can easily avoid the trap of plagiarism , and promote further research on their topic.

They Create Better Researchers

By researching sources to back up and promote their ideas, students are becoming better researchers without even knowing it! Each time a new source is read or researched, the student is becoming more engaged with the project and is developing a deeper understanding of the subject area. Proper citations demonstrate a breadth of the student’s reading and dedication to the project itself. By creating citations, students are compelled to make connections between their sources and discern research patterns. Each time they complete this process, they are helping themselves become better researchers and writers overall.

When is the Right Time to Start Making Citations?

Make in-text/parenthetical citations as you need them.

As you are writing your paper, be sure to include references within the text that correspond with references in a works cited or bibliography. These are usually called in-text citations or parenthetical citations in MLA and APA formats. The most effective time to complete these is directly after you have made your reference to another source. For instance, after writing the line from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities : “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…,” you would include a citation like this (depending on your chosen citation style):

(Dickens 11).