You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Analysis & Opinion

Racial Gaps in Voter Turnout Are Growing — and Undermining Democracy

The difference in turnout between white and nonwhite voters has soared since 2008, especially in regions once covered by strict Voting Rights Act protections.

- Arlyss Herzig

- Vote Suppression

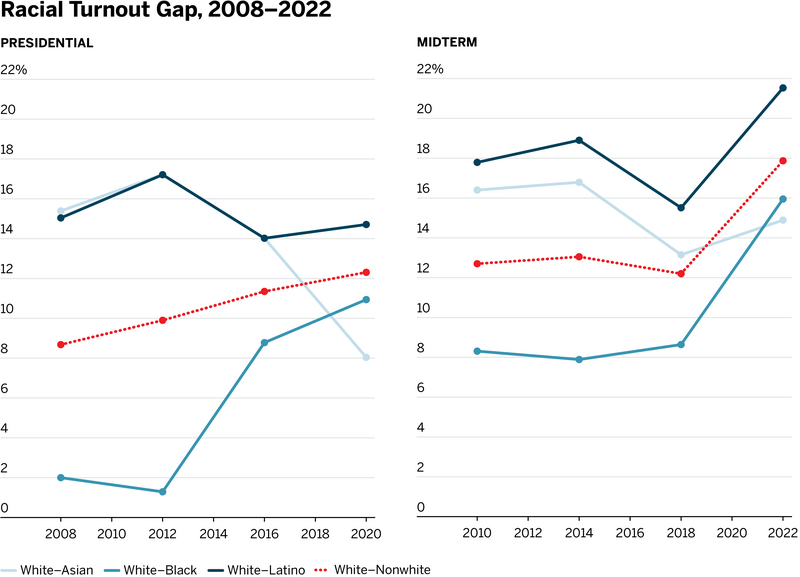

A new report from the Brennan Center shows just how far we are from fulfilling the country’s promise of a democracy equally open to all Americans. The racial turnout gap — the difference between white and nonwhite turnout rates in elections — has been consistently growing since at least 2008, reaching 18 percentage points in the 2022 midterm elections. If the gap did not exist, nearly 14 million additional ballots would have come from voters of color that year.

And although the 2022 midterms saw the largest gap in recent years, the disparity in turnout isn’t new: the 2012 election was the only election in recent times to reach near parity between the turnout rates for Black and white voters, and at no point in at least 16 years has the turnout gap closed for any other group.

To better understand how the racial turnout gap has grown across the nation since 2008, we used nearly 1 billion vote records between 2008 and 2022. This voter snapshot data offers a better understanding of turnout compared to even the largest survey samples. The data also helped us observe how regional and socioeconomic factors influence the racial turnout gap. We found evidence that the ballot box reflects the voices of different racial groups at decidedly unequal rates, disproportionately uplifting white citizens.

While the turnout gap has never fully closed, it was smaller during the Obama presidential years than today. In presidential elections, the racial turnout gap has grown consistently since at least 2008 (the first election for which nationwide voter files are available). In 2008 the gap was 9 points, and by 2020 it had grown to 12 points. Things were no better in the midterms: in 2022, even with the second highest turnout for a midterm election in 20 years, both the white-Latino gap and white-Black gap were the largest they have been since at least 2010.

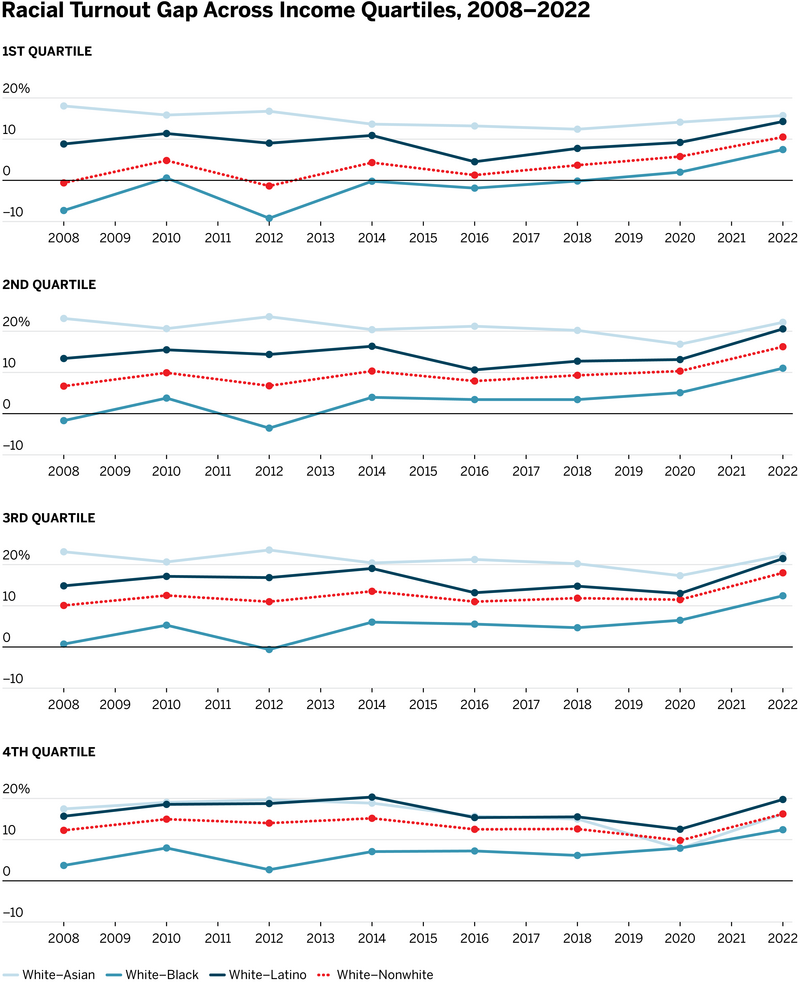

Importantly, these turnout gaps exist even when accounting for regional differences, income, and education. Though these factors account for some of the gap, they cannot fully explain it. White voter turnout has exceeded that of any nonwhite group since 2014 in every geographic region. While turnout tends to vary based on a neighborhood’s median household income and proportion of residents with a college degree, we still find racial turnout gaps in high- and low-income neighborhoods alike. The same is true of neighborhoods with high and low levels of education.

Myriad factors drive the nationwide racial turnout gap, like political disaffection, high rates of incarceration, inaccessibility at polling places, and language barriers, among other disenfranchising forces. However, the widening of the gap is occurring alongside a wave of restrictive voting laws going into effect. Within the past decade alone, almost 100 restrictive voting laws have been enacted in at least 29 states. And the mounting attacks on democracy are not felt equally by all — when access to the ballot is restricted, voters of color are more likely to be disenfranchised .

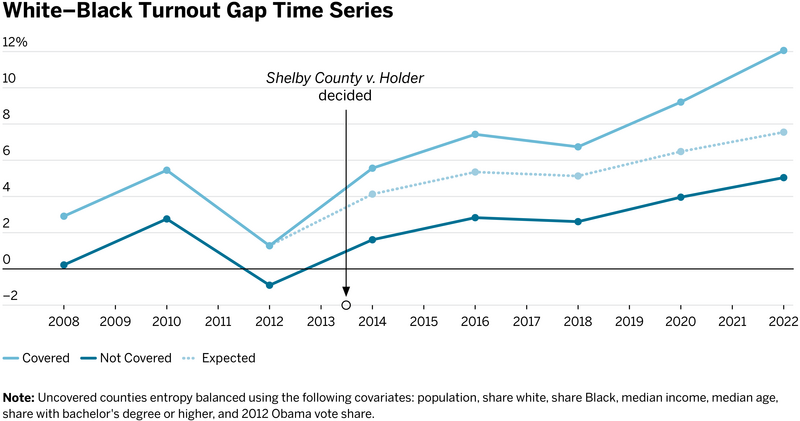

One key driver of the growth in the turnout gap in recent years is the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder. The decision severely weakened the Voting Rights Act by gutting Section 5, which required federal approval for any changes to election rules and practices in areas with a history of racially discriminatory voting policies, a process known as preclearance. Pointing to Black turnout surpassing white turnout in covered states in the 2012 election, the ruling claimed that federal approval was no longer necessary to protect the right to vote.

The same day the Supreme Court announced its decision, Texas passed a discriminatory voter ID law that had formerly been blocked by the federal government. Mississippi, Alabama, and North Carolina soon followed with similar legislation that established voter ID and other restrictive voting laws aimed at Black communities. A federal court later described North Carolina’s law as “target[ing] African Americans with almost surgical precision.” The decision also allowed for many more local changes to go unchallenged. Prior to 2013, county administrators needed permission to move polling places, draw school board districts, and make other administrative and policy changes.

We use advanced statistical tools to prove the cumulative, negative effect of all the changes made in the aftermath of Shelby County . As the chart below shows, the changes in the white-Black turnout gap moved in tandem in counties that were covered and not covered by Voting Rights Act approval requirements during the years before Shelby County . After the decision, however, the gap has grown more quickly in the formerly covered counties. Though the racial turnout gap has increased everywhere since the Shelby County decision, it has grown almost twice as quickly in formerly covered jurisdictions than in similar, non-covered ones.

In fact, the white-Black turnout gap in formerly covered regions was 5 percentage points greater in 2022 than it would have been if the preclearance had applied, while the white-nonwhite gap was about 4 points higher. These gaps are especially significant in light of the fact that, according to Brennan Center research, since Shelby County was decided at least 62 Senate, gubernatorial, and presidential races in the states containing areas subject to preclearance have been decided by fewer than 5 percentage points.

We show that these effects were largest in counties where state and local practices were constrained by Section 5, as well as in counties that had racially discriminatory policies blocked by Section 5 in the years before the Shelby County decision. The effect is clear: the ruling cost hundreds of thousands of votes from voters of color in formerly covered counties in the 2022 midterm election.

Discriminatory voting policies and practices further remove us from America’s vision of a representative democracy. These laws target voters of color, likely increasing the racial turnout gap, impacting the ability of communities of colors to elect representatives that are responsive to their needs. Despite the Supreme Court’s view that racial differences in political participation are a thing of the past, this study provides compelling evidence that the Shelby County decision has accelerated this disturbing trend in democracy.

Related Issues:

California Advances Legislation to Protect Voters and Workers Against Intimidation

At a hearing Wednesday, the California State Assembly Committee on Elections passed the Peace Act with support from the Brennan Center.

Frivolous Lawsuit Targets Maryland’s Voter Rolls and Voting Systems

The case is part of a nationwide strategy to sow doubt in the 2024 election ahead of November.

We’re Defending Michigan Voters from a Lawsuit Threatening Their Ability to Vote

Mass purges are the new voter suppression, people of color are being deterred from voting, disparity between white and nonwhite voter turnout reaches new high, closing arguments in lawsuit against texas voter suppression law, related resources.

Growing Racial Disparities in Voter Turnout, 2008–2022

The gap is increasing nationwide, especially in counties that had been subject to federal oversight until the Supreme Court invalidated preclearance in 2013.

Kevin Morris

Coryn Grange

Informed citizens are democracy’s best defense.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Republican Gains in 2022 Midterms Driven Mostly by Turnout Advantage

1. voter turnout, 2018-2022, table of contents.

- Other key findings from the study

- Political preferences differ a lot by race and ethnicity … and so does voter turnout

- Voters and nonvoters

- Voting methods in the 2022 election

- Gender, race and the 2022 vote

- Education and voting preferences

- Age and the 2022 election

- Party, ideology and the 2022 election

- Urban, suburban, rural voting in 2022

- Religion and the 2022 election

- Racial and ethnic composition of 2022 voters

- Rural, suburban and urban composition of 2022 voters

- Educational composition of 2022 voters

- Age composition of 2022 voters

- Religious composition of 2022 voters

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

American Trends Panel: Pew Research Center’s online probability survey panel , which consists of more than 12,000 adults who take two to three surveys each month. Some panelists have been participating in surveys since 2014.

Defectors/Defection: People who either switch their vote to a different party’s candidate from one election to the next, or those who in a given election do not support the candidate of the party they usually support. Also referred to as “vote switching.”

Drop off/Drop-off voters: People who vote in a given election but not in a subsequent election. The term commonly refers to people who vote in a presidential election but not in the next midterm. It can also apply to any set of elections.

Midterm elections: General elections held in all states and the District of Columbia in the even-numbered years between presidential elections. All U.S. House seats are up for election every two years, as are a third of U.S. Senate seats (senators serve six-year terms).

Mobilize: Efforts by candidates, political campaigns and other organizations to encourage or facilitate eligible citizens to turn out to vote.

Nonvoter: Citizens who didn’t have a record of voting in any voter file or told us they didn’t vote.

Panel survey: A type of survey that relies on a group of people who have agreed to participate in multiple surveys over a time period. Panel surveys make it possible to observe how individuals change over time because the answers they give to questions in a current survey can be compared with their answers from a previous survey.

Party affiliation/Party identification: Psychological attachment to a particular political party, either thinking of oneself as a member of the party or expressing greater closeness to one party than another. Our study categorizes adults as Democrats or Republicans using their self-reported party identification in a survey.

Split-ticket voting/Straight-ticket voting: Voters typically cast ballots for more than one office in a general election. People who vote only for candidates of the same party are “straight-ticket” voters, while those who vote for candidates of different parties are “split-ticket” voters.

Turnout: Refers to “turning out” to vote, or simply “voting.” Also used to refer to the share of eligible adults who voted in a given election (e.g., “The turnout in 2020 among the voting eligible population in the U.S. was 67%”).

Validated voters/Verified voter: Citizens who told us in a post-election survey that they voted in the 2022 general elections and have a record for voting in a commercial voter file. (The two terms are interchangeable).

Voter file: A list of adults that includes information such as whether a person is registered to vote, which elections they have voted in, whether they voted in person or by mail, and additional data. Voter files do not say who a voter cast a ballot for. Federal law requires states to maintain electronic voter files, and businesses assemble these files to create a nationwide list of adults along with their voter information.

The elections of 2018, 2020 and 2022 were three of the highest-turnout U.S. elections of their respective types in decades. About two-thirds (66%) of the voting-eligible population turned out for the 2020 presidential election – the highest rate for any national election since 1900. The 2018 election (49% turnout) had the highest rate for a midterm since 1914. Even the 2022 election’s turnout, with a slightly lower rate of 46%, exceeded that of all midterm elections since 1970.

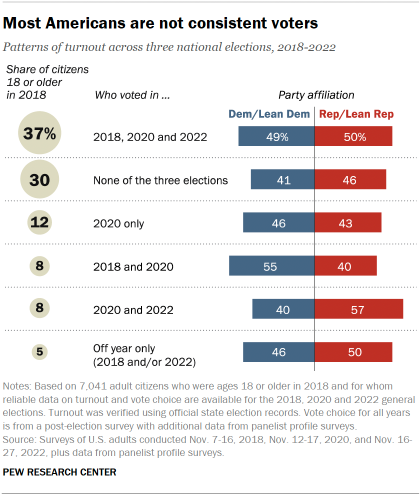

While sizable shares of the public vote either consistently or not at all, many people vote intermittently. Given how closely divided the U.S. is politically, these intermittent voters often determine the outcome of elections and how the balance of support for the two major political parties swings between elections.

Overall, 70% of U.S. adult citizens who were eligible to participate in all three elections between 2018 and 2022 voted in at least one of them, with about half that share (37%) voting in all three.

Adults who voted in at least one election during the period divide evenly between Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party or Republicans and Republican-leaning independents in their current party affiliation (48% each). The subset who voted in all three elections are similarly divided (49% Democrats, 50% Republicans). Citizens who did not vote in any of the three tilt Republican by 46% to 41%.

Democrats outnumbered Republicans among the 8% of adult citizens who voted in 2018 and 2020 but not 2022 (55% Democratic, 40% Republican). A similar-sized group (8%) voted in 2020 and 2022 but not 2018, and this group’s composition tilts Republican (57%, vs. 40% Democratic). The 12% who voted in 2020 and opted out of both the 2018 and 2022 midterms were roughly evenly divided among Democrats (46%) and Republicans (43%).

Given the sizable number of intermittent voters and chronic nonvoters, as well as the fact that this group, collectively, is fairly evenly divided in partisan affiliation, both parties have plenty of potential supporters on the sidelines in any given election.

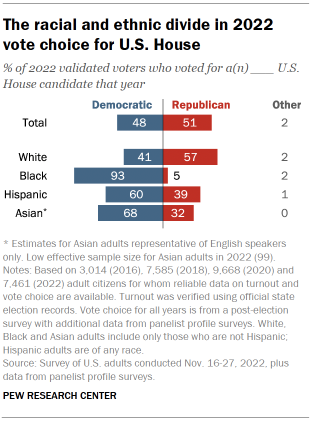

Race and ethnicity are fundamental dividing lines in American politics, with political preferences and electoral participation varying greatly by race and ethnicity.

In the current partisan alignment, Black, Hispanic and Asian voters are all majority Democratic groups, to different degrees, though Republican candidates have gained some ground in the past four years among Hispanic voters.

Black voters remain Democratic stalwarts, voting 93% to 5% for the party’s candidates for U.S. House in 2022. Hispanic and Asian voters clearly favored Democratic candidates as well, but by narrower margins: 60% to 39% for Hispanic voters, and 68% to 32% for Asian voters.

But White Americans are much more consistent voters than Black, Hispanic or Asian Americans. Compared with the national average of 37% who voted in 2018, 2020 and 2022, 43% of White citizens who were age eligible to vote in all three elections did so; just 24% did not vote in any of these.

Black, Hispanic and Asian adults lagged far behind, with 27% of Black, 19% of Hispanic and 21% of Asian age-eligible citizens voting in all three elections. Hispanic citizens were most likely to have not voted in any of the most recent three general elections (47%, compared with 36% for Black and 31% for Asian citizens ages 22 and older in 2022).

Differences by education

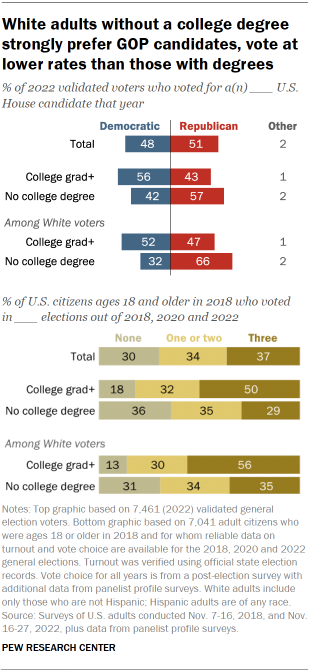

Over the past few election cycles, Republicans have gained ground among White adults who do not have a college degree, who make up 41% of eligible voters. This group is about average in its consistency of voter turnout, with 35% of those ages 22 and over in 2022 voting in 2018, 2020 and 2022, and 31% voting in none of these three elections. White voters without a college degree favored Republican House candidates 66% to 32% in 2022.

By contrast, White adults with college degrees vote at very high rates: 56% of those eligible turned out in all three elections and just 13% participated in none of them. College-educated White adults make up 24% of the eligible electorate but about a third of voters in 2022 (34%). White voters with college degrees had tilted Republican for several decades, but in the past four elections have favored Democratic candidates (52% to 47% in 2022).

The education gap in White voters’ preferences in 2022 was not apparent among either Black or Hispanic voters (the sample size of Asian voters without a college degree was too small to produce a reliable estimate). College-educated Black and Hispanic adults also voted at higher rates than Black and Hispanic adults without a college degree in each of the three elections.

A small education gap appeared in 2020 presidential preference among Hispanic voters: College-educated Hispanic voters preferred Biden by a margin of 69% to 29%, while Hispanic voters without a college degree preferred Biden by a somewhat narrower margin (58% to 39%). But no significant education gap in candidate preference was observed for Black or Hispanic voters in 2018 or 2022, nor for Black voters in 2020.

The upshot of racial differences in candidate preference and turnout patterns is that Republican candidates benefited from both the relatively large size of the White adult population without a college degree and their somewhat higher turnout rates compared with Black, Hispanic and Asian adults.

Growth in support for Democratic candidates among White voters with a college degree, along with the high turnout levels among this group, offset some of the growth in support for the Republican Party among White voters without a college degree. But college-educated White adults remain a smaller share of all eligible voters than White adults without a college degree.

The two most recent midterms – 2022 and 2018 – both featured unusually high turnout compared with nearly every other recent midterm election year. But the differences between those who turned out to vote in 2022 versus 2018 – and between those who did not vote – accounted for much of the difference in outcomes between the two elections.

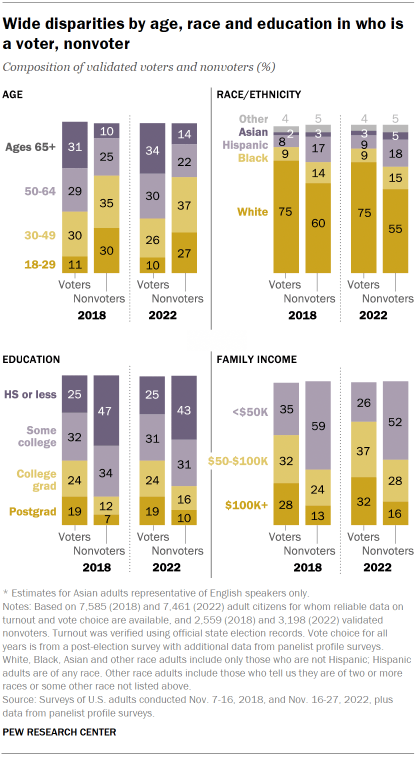

The stark demographic differences between voters and nonvoters in 2022 are similar to those seen in previous U.S. elections.

Voters were much older, on average, than nonvoters. Adults under 50 made up 36% of voters, but 64% of nonvoters. This is very similar to the pattern seen in 2018 – although those under 50 made up a somewhat larger share of voters in 2018 (40%).

Turnout also differed by race and ethnicity.

Three-quarters of voters (75%) were White, non-Hispanic adults. But this group accounted for a smaller share (55%) of nonvoters. Hispanic adults and Black, non-Hispanic adults each made up 9% of voters, but slightly larger shares of nonvoters (18% and 15%, respectively). Asian Americans made up 3% of voters, and a slightly higher share (5%) of nonvoters. These differences are nearly identical to the patterns seen in 2018.

There are also large educational and income differences between voters and nonvoters. Adults with a college degree made up 43% of voters in 2022, but only 25% of nonvoters. Those without a college degree made up 56% of voters, but 74% of nonvoters.

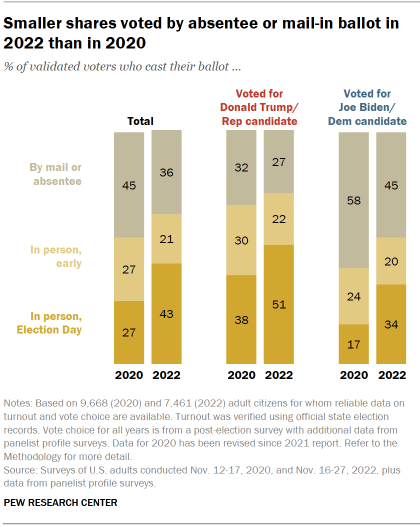

As concerns over the COVID-19 pandemic declined, fewer voters reported having voted absentee or by mail in 2022 than in 2020.

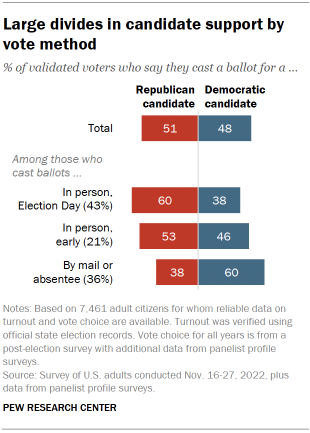

In 2022, 43% of voters said they cast their ballot in person on Election Day. A somewhat smaller share (36%) said they cast an absentee or mail-in ballot, and 21% said they voted in person before Election Day.

In the 2020 election, held during the first year of the coronavirus pandemic, 45% of voters said they cast their ballots by absentee or mail-in ballot, while identical shares (27%) said they voted in person either on Election Day or beforehand.

As was the case in 2020, voters who supported Republican candidates were more likely to report having voted in person on Election Day than by other methods. About half (51%) of those who supported Republicans said they voted this way, while smaller shares said they voted by mail or absentee ballot (27%) or voted in person before Election Day (22%). In 2020, 38% said they voted in person on Election Day, while somewhat smaller shares said they voted by mail or absentee (32%) or voted in person before Election Day (30%).

Voters who supported Democratic candidates were more likely to say they cast absentee or mail-in ballots (45%). About one-third (34%) said they voted in person on Election Day and two-in-ten said they voted in person before Election Day. In 2020, a 58% majority said they voted by mail or absentee ballot, while just 17% said they voted in person on Election Day.

Reflecting these patterns, Republicans won a majority of votes among those who said they voted in person on Election Day, 60% to 38%. Democrats won – by an identical margin – voters who said they voted by mail or absentee ballot. Those who said they voted in person before Election Day were divided: 53% supported Republican candidates, while 46% voted for Democratic candidates.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Education & Politics

- Election 2022

- Election System & Voting Process

- Gender & Politics

- Generations, Age & Politics

- Political Parties

- Race, Ethnicity & Politics

- Voter Demographics

- Voter Files

- Voter Participation

Changing Partisan Coalitions in a Politically Divided Nation

What’s it like to be a teacher in america today, more americans disapprove than approve of colleges considering race, ethnicity in admissions decisions, partisan divides over k-12 education in 8 charts, school district mission statements highlight a partisan divide over diversity, equity and inclusion in k-12 education, most popular, report materials.

- 2016-2022 Validated Voters Detailed Tables

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- DynamicPowerPoint.com

- SignageTube.com

- SplitFlapTV.com

Voter Turnout Personalized Videos Created in PowerPoint

Oct 24, 2020 | Articles , Case Studies , DataPoint , Elections , Evergreen , Government , Non-profit

In this video, we show you how you can create personalized voter turnout videos using PowerPoint. The examples shown are for the US election, but will also work for any country, state, province, or municipal election. This could be used to increase voter turnout on a non-partisan basis or to improve voter turnout for your political party or to get people out to vote on a specific issue. The tool used in the video is DataPoint Enterprise edition.

Look at the video above to see how we created these personalized voter turnout videos and to see examples. So how did we do this?

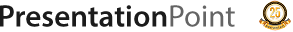

Step 1: Gather Voter Turnout & Other Data

My first step whenever I am creating data-driven presentations or personalized videos is to gather the data I needed. In this case, my approach was to combine personal information about a voter with the issues important to them and then with the voter turnout numbers in their area in the last election.

The voter personal information and issues important to them could come from a poll or survey you did in their area or by having them fill out an online form such as a “Who should I vote for?” online quiz they could fill out and provide their name and email.

In this case, I just put in some sample information. The names are made up and any relation to any real people in these areas is not intended.

The voter turnout information is readily available online and I grabbed the real data from a government website.

For simplicity’s sake, I put all the information in a single spreadsheet, but I could have easily had one spreadsheet with the voter information and issues and one spreadsheet with voter turnout and just combined them in the PowerPoint presentation.

Here is what the spreadsheet looks like.

Submit a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Pin It on Pinterest

- StumbleUpon

- Print Friendly

Voter turnout

What is 'voter turnout', measuring turnout, studying voter turnout, can reforms increase turnout, what if everyone voted, data sources, suggested readings.

Important legislation in the twentieth century, most notably the Voting Rights Act of 1965, has led to a long-term increase in the ability of Americans to participate in elections. The effects of other legislation intended to increase turnout, such as the National Voter Registration Act, have been more limited to specific administrative practices across states.

This explainer was last updated on April 28, 2021.

Because high voter turnout is considered a mark of a thriving democracy, policymakers and citizens often support electoral reform measures based on whether they will increase turnout, either overall or for particular groups.

Although the idea of voter turnout is simple, measuring it is complicated. And even if the number of people who voted in an election is accurately counted, it's often unclear what turnout should be compared to—the number of eligible voters? Registered voters?

Political debates often rage over whether particular reforms will raise or lower turnout, either overall or for particular groups. In the 2020 election particularly, the rapid changes in how elections were administered, due to the pandemic, resulted in particularly heated discussions over election reforms and their effects.

Turnout can be measured in the aggregate by simply counting up the number who vote in an election. Data from the United States Elections Project (USEP) indicates that 159.7 million voters participated in the 2020 presidential election. While it was previously difficult to determine the number of ballots cast and instead had to rely on the most ballots cast in a “highest off” (i.e. the office with the most votes for a candidate), more and more states are reporting total ballots counted alongside the results of the election. Nonetheless, in 2020, seven states (Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Texas) did not record how many people turned out to vote.

With the number of voters determined, we can now discuss the selection of the denominator to calculate the turnout rate . Often, states and news sources will provide turnout numbers that use registration as the denominator. This results in inconsistent measurements across states due to inconsistent practices, policies, and/or laws around the maintenance of their voter registration lists. For a more consistent measure, it is better to use a measure that reflects the population of possible voters.

The easiest comparison is with the voting age population (VAP)-that is, the number of people who are 18 and older according to U.S. Census Bureau. However, VAP includes individuals who are ineligible to vote, such as non-citizens and those disfranchised because of felony convictions. Thus, two additional measures of the voting-eligible population have been developed:

- Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) , which is based on Census Bureau population estimates generated using the American Community Survey.

- Voting Eligible Population (VEP), which is calculated by removing felons (according to state law), non-citizens, and those judged mentally incapacitated.

The denominator one chooses to calculate the turnout rate depends on the purposes of the analysis and the availability of data. Usually, VEP is the most preferred denominator, followed by CVAP, and then VAP. The estimated VEP in 2020 was 239.4 million, compared to an estimated VAP of 257.6 million.

Figure 1 shows the nationwide turnout rate in federal elections, calculated as a percentage of VEP by the USEP , from 1980 to 2020. In addition to the variation across time, the most notable pattern in this graph is the difference in turnout between years with presidential elections ("on years") and those without presidential elections ("off years"). Elections that occur in odd-numbered years and at times other than November typically have significantly lower turnout rates than the ones shown on the graph. (The turnout rate in the 2020 presidential election was the greatest since 1904.)

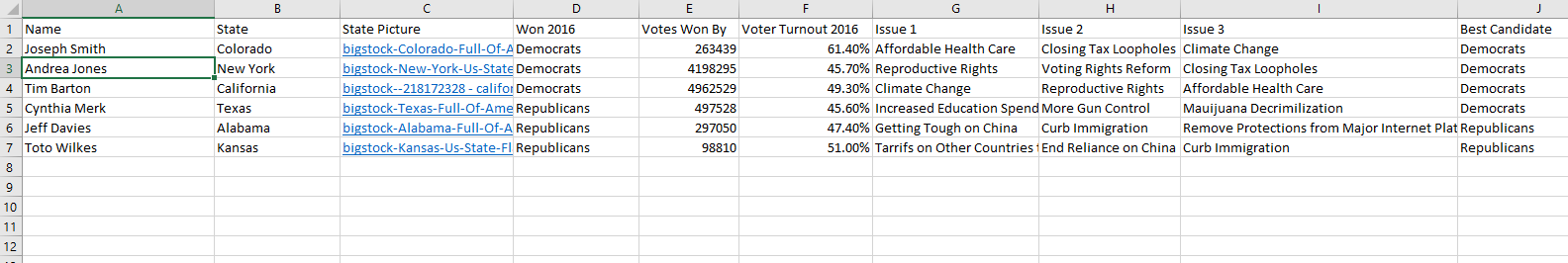

Figure 2 shows turnout rates in the 2020 election for each state. Although there are exceptions, states with the highest turnout rates in presidential elections tend to be in the north, while states with lower turnout rates tend to be in the south.

Sometimes we want to measure the turnout rates of groups of voters, or study the factors that lead individual citizens to vote. In these cases, we need individual measures of turnout based on answers to public opinion surveys.

The chief difficulty in using public opinion surveys to ascertain individual voter turnout is the problem of social-desirability bias , whereby many respondents who did not vote will nonetheless say they did to look like good citizens. As a result, estimates of turnout rates based on surveys will be higher than those based on administrative records. (For example, 78% of respondents to the 2012 American National Election Studies survey reported voting, compared to the actual turnout rate of 58% as reflected in the graph above.) To guard against over-reporting turnout in surveys, some studies use voter registration records to independently verify whether respondents voted, but few do.

Even with the problems of over-reporting, public opinion surveys are usually the only way we can study the turnout patterns of subpopulations of voters, such as regional or racial groups. It would be safe to use these surveys if all groups over-report on whether they voted by equal amounts, but there is evidence they don’t.

One consequence of the secret ballot is the inability to directly tie demographic factors to an actually recorded vote. Instead, researchers have relied on Voting and Registration Supplement (VRS) of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) to gather information about the demographic factors that affect turnout. The CPS is a monthly survey on employment and the economy. The VRS, which is administered every November in even-numbered years, asks respondents whether they voted in the most recent election. Because the CPS already has a rich set of demographic information about each voter and has been conducted for decades, this is often the best source of data

The dominant theory for why turnout varies focuses on a type of cost-benefit calculation as seen from the perspective of the voter. Voters balance what they stand to gain if one candidate beats another, vs. their economic or social costs of voting. Other scholarship has challenged this approach by showing that going to the polls is largely based on voting being intrinsically rewarding.

A long history of political science research has shown that the following demographic factors are associated with higher levels of voter turnout: more education, higher income, older age, and being married (see table below). Women currently vote at slightly higher levels than men.

Can particular election reforms such as Election Day registration, vote-by-mail, early voting, photo ID, etc., have an effect on voter turnout? Research results in most of these areas have been mixed at best. The one reform that is most consistently correlated with higher levels of turnout is Election Day registration (EDR) , although even here, there is disagreement over whether EDR causes higher turnout or if states with existing higher turnout levels are more likely to pass EDR laws (it’s probably a combination of the two).

What about the roles that campaigns play in stimulating voter turnout? This is most visible in presidential elections, where candidates pour disproportionate resources into campaigning in battleground states—those that are closely divided along partisan lines and thus are most likely to swing the result of the Electoral College vote. In 2020, the average turnout in the 8 states where the presidential margin of victory was 5 percentage points or less was 70%, compared to 59% in the nine states where the margin of victory was greater than 30 points. (For the states in-between, the average turnout rate was 68%.)

Field experiments to test the effects of campaign communications on voter turnout have shown that personalized methods work best in mobilizing voters and mass e-mails are virtually never effective in stimulating turnout.

We care about turnout levels for two reasons. First, they're considered a measure of the health of a democracy, so higher turnout is always better than lower turnout. Second, if we believe that lower turnout levels exclude citizens with particular political views, then increasing turnout would “unskew” the electorate.

Early research seemed to justify skepticism that increasing turnout in federal elections would radically change the mix of opinions among those who actually vote. However, more recent research suggests that voters in national elections are more likely to be Republican and to oppose redistributive social policies than non-voters. Differences between voters and non-voters on other issues such as foreign policy are much less pronounced.

When it comes to local elections, overall turnout rates tend to be much lower than elections held to coincide with federal elections, and the demographic characteristics of voters are much more skewed compared to non-voters.

American National Election Studies

The United States Election Project

U.S. Census Bureau—Voting and Registration

Aldrich, John H. 1993. "Rational Choice and Turnout." American Journal of Political Science 37 (1): 246–278.

Green, Donald P., and, Alan S Gerber. 2015. Get Out the Vote: How to Increase Voter Turnout . Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Hur, Aram and Christopher H. Achen. 2013. “Coding Voter Turnout Responses in the Current Population Survey.” Public Opinion Quarterly 77(4); 985 – 993.

Leighley, Jan E., and Nagler, Jonathan . 2013. Who Votes Now?: Demographics, Issues, Inequality, and Turnout in the United States . Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Silver, Brian D., Barbara A. Anderson, and Paul. R. Abramson. 1986. "Who Overreports Voting? " American Political Science Review 80 (2): 613–624.

Riker, William H., and Peter C. Ordeshook. 1968. "A Theory of the Calculus of Voting." American Political Science Review 62 (1): 25–42.

Wolfinger, Raymond E., and Steven J. Rosenstone. 1980. Who Votes? New Haven: Yale University Press.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Remember Eric Garner? George Floyd?

Lawyers reap big profits lobbying government regulators under the radar

Younger votes still lean toward Biden — but it’s complicated

“What if 80 percent of the adults in America actually voted? What would that be like and how could we get there?” asked Archon Fung of the Harvard Kennedy School.

Sarah Grucza/Ash Center

Turn voting into a celebration, not a chore

John Laidler

Harvard Correspondent

Panel examines ways to challenge civic culture, increase turnout

Just 56 percent of eligible American voters in cast ballots for president in the 2016 election, and nearly two-thirds remained on the sidelines in the 2014 midterms.

With the November election approaching, a Harvard panel on Friday cited those and other statistics to highlight how low voter turnout remains a stubborn challenge to American democracy, while also suggesting possible solutions.

“The vote is the most fundamental act of American democracy and yet very few of us actually turn out to vote,” said Archon Fung, Winthrop Laflin McCormack Professor of Citizenship and Self-Government at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Sponsored by the Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, the panel was part of HUBweek (Oct. 8‒14), the annual ideas festival co-founded by Harvard, The Boston Globe, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Fung noted that in recent presidential elections, far fewer Americans voted for the winning candidate than cast no vote at all. And he said the U.S. ranks near the bottom of advanced nations with its voting rates.

“The equivalent of the moonshot for American democracy would be getting to 80 percent participation,” a goal the Kennedy School is promoting with other groups, Fung said.

“What if 80 percent of the adults in America actually voted? What would that be like and how could we get there?” asked Fung, who called voting not only a civic responsibility but critical to promoting equality, making government responsive, and restoring trust in government.

The panel included Archon Fung of Harvard (from left), Democracy Works CEO Kathryn Peters, Corley Kenna of Patagonia, and John Horton of Lyft. This year, Lyft is offering discounted rides to the polls, and partnering with nonprofits to offer free rides in underserved communities.

Policy initiatives could help raise voting rates, Fung said, but changing civic culture is also key.

“How can we get companies and schools and other kinds of organizations to think that it’s part of their civic responsibility to encourage full participation?” he said. Fung added that we also need to change the idea of voting “from a chore to a celebration.”

As an example of what organizations can do, Fung cited the Kennedy School’s commitment this year to get 90 percent of its voting-eligible students to register.

More like this

Corporate activism takes on precarious role

Kathryn Peters, co-founder and chief operating officer of Democracy Works, discussed her organization’s TurboVote web platform , which seeks to increase voting by providing people with voting information specific to their geographic area.

Because voting procedures vary across the country, Peters said, “With TurboVote, we’ve built effectively a voter concierge that lets anyone walk through and find the process to be as understandable and welcoming as possible.”

Peters said she has seen the value of online relationships in spurring people to vote.

“Snapchat deciding that they were going to be excited about voting this year is possibly one of the biggest stories in the 18- to 23-[year-old] new-voter demographic that I can think of,” she said.

Corley Kenna, senior director of Global Communications and Public Relations for Patagonia, described the outdoor retailer’s efforts to promote voting.

“Our company culture is a lot about being responsible stewards of our resources but also being responsible citizens and … one of the most important responsibilities that we have in our society is voting,” Kenna said. This election season, “We are talking to our community about how democracy requires showing up.”

As it did in 2016, the company is also closing its stores and giving employees Election Day off to send the message that “it’s more important to vote than to shop” that day, Kenna said. It also helped launch a campaign in which 300 companies have pledged policies that ensure that employees have time to vote.

John Horton, senior manager of East Coast community affairs for Lyft, outlined how the ride-hailing company became involved in boosting voter turnout.

“We’re all about solving problems,” he said, and since lack of transportation can be a barrier to voting, “we thought, here is a problem we can easily attack.”

Lyft this year is offering discounted rides to the polls, and partnering with nonprofits to offer free rides in underserved communities. The company is also closing part of its corporate offices on Election Day, and has registered 16,000 new voters.

Fung asked his fellow panelists what strategy they would advocate to meet the 80 percent voting goal. Peters said she would support Civic Nation’s #VoteTogether program, which throws parties during election seasons.

“That idea of having it festive, of civics not being dour, is really important,” said Peters, who would also like other states “to adopt a voting system that looks like Colorado,” which combines mail-in balloting and other measures to make voting easy.

Horton said educating people about where and when to vote, and setting uniform election dates, would be important.

Kenna said she would like to see a uniform, mail-in ballot system across the country and to make Election Day a national holiday where “we celebrate our democracy and the fact that it works when we vote.”

Share this article

You might like.

Mother, uncle of two whose deaths at hands of police officers ignited movement talk about turning pain into activism, keeping hope alive

Study exposes how banks sway policy from shadows, by targeting bureaucrats instead of politicians

New IOP poll shows they still plan to show up to vote but are subject to ‘seismic mood swings’ over specific issues

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

What are you looking for?

Popular searches.

- public health

- extreme weather

Media Briefings

Trends in voter turnout

October 18, 2022

Journalists: Get Email Updates

What are Media Briefings?

More than two thirds of American adults voted in the 2020 presidential election—the highest voter turnout rate this century. As we approach the 2022 midterms, political and special interest groups will be increasingly focused on “getting out the vote” among different demographic blocks. At SciLine’s media briefing, three experts discussed what the research says about demographic trends in voter turnout, including patterns specific to different age groups, the persistent gender voting gap, and additional complexities that arise at the intersection of gender and race. They also discussed voter-ID laws and other barriers that influence political participation among different populations and communities. Brief presentations were followed by reporter Q&A.

Journalists: video free for use in your stories

High definition (mp4, 1920x1080)

Introduction

RICK WEISS: Hello, everyone. Welcome to SciLine’s media briefing on trends in voter turnout—a topic in the news with pretty big implications for what’s going to happen at the local and state polls in November. I’m SciLine’s director, Rick Weiss. And for those not familiar with us, SciLine is a philanthropically funded, editorially independent free service for journalists and scientists based at the nonprofit American Association for the Advancement of Science. Our mission is pretty straightforward. It’s just to make it easier for reporters like you to get more scientifically validated evidence into your news stories. And that means—again, as I often tell reporters I’m talking to, that means not just stories that are about science, per se, but really, any story that can be strengthened by some science, which is just about any story that we can think of.

Today’s briefing is actually a great example of that. You know, who turns out to the elections in November and how that affects the results is a political story, but social and political scientists have studied these dynamics, and their findings can and should inform your political reporting. So, I’m looking forward to hearing what these experts have to tell us today. Among other things you should know about SciLine before we get started is that we do offer a free matching service that helps connect you directly, one on one, to scientists who are both very knowledgeable in their fields and are great communicators. We do that for you on deadline or as needed. So, just go to the sciline.org website and click on I need an expert. And while you’re there, you can check out our other helpful reporting resources.

A couple of quick logistical details before we get started. We’re going to have three panelists who will make short presentations of just maybe six or seven minutes each before we open things up for Q&A. To enter a question either during or after their presentations, just hover over the bottom of your Zoom window, select Q&A, enter your name, news outlet and your question, and if you want to pose that question to a particular panelist, be sure to note that. A full video of this briefing should be available on our website by the end of the day today or early this evening. A time-stamped transcript should be up within a day or two after that. And if you’d like a raw copy of the recording more immediately than any of that, just submit a request through that Q&A box, and we’ll send you a link to that video by the end of today. You can also use the Q&A box to alert SciLine staff to any technical difficulties.

All right. To get started, I’m not going to take time to give full introductions to our speakers. Their bios are on the website. I just want to tell you that we will hear first from Dr. Jane Junn, who is the USC associates chair in social sciences and a professor of political science and gender and sexuality studies—everything you want to hear about today—at the University of Southern California. She’ll be speaking about voter turnout, gender gap and how that intersects with how race influences voter participation. Second, we’re going to hear from Dr. John Holbein, who is an associate professor of public policy, politics and education at the University of Virginia. He’s going to talk about age and voter turnout and how that relationship intersects with race as well and what’s known about what works to increase youth voter participation. And third, we’ll hear from Dr. Nazita Lajevardi who is an associate professor in the department of political science at Michigan State, and she’s going to talk to us about U.S. voter ID laws and other similar legislation in states across the country and what the research tells us about how these laws influence political participation, who’s most affected by them and some of the challenges, actually, to studying their actual impact. OK. Let’s get started. And over to you to start us off, Dr. Junn.

Gender and voter turnout

JANE JUNN: Great. Thank you. And I’m delighted to be here. Let’s just begin. I have a very brief presentation and just want to give you three things to think about—all the reporters, journalists in the room, just three things to think about when you consider the big and broader question of gender and voting in U.S. elections. That’s my email address there. And you probably also have it in the link where you can contact me.

So, I’ll give you the takeaways, and I’d like to give you three. The first one is that women are the modal voter—by that, meaning the biggest category of voters with respect to sex—in the American electorate. For example, in the last election—I mean, sometimes people find this surprising, but it’s been true now for quite a long time, really since the ’60s, particularly in presidential elections. So, as you all know, women gained the right to vote by constitutional amendment in the 19th Amendment, which was ratified and then became a part of federal law through the Constitution in 1920, a little more than a hundred years ago. And at that time, of course, they were zero part of the voting population for the most part, and now they make up 53.1% of the electorate—that is, people who come out to vote. That’s how we define the electorate. And that’s more than men, which are at about 47%—just under 40% of the electorate. And this is data from 2020’s presidential election, so not a midterm but 2020. But even in the midterms, what you’ll see is a similar distribution. And that’s even true at local levels and state levels as well. So, women are the modal voter, meaning the biggest category, and have been, outnumbering men in the electorate for many decades. These—and what’s relevant about that is, well, women voters are the most powerful group in the American electorate. Despite the fact that elected officials are disproportionately male, women are disproportionately a part of the electorate.

The second point I’d like to make is that the gender gap is a race gap. So, you all know that women overall support Democrats more than men, but that’s not true for all women. So, in other words, not all women support Democratic candidates by a majority. Instead—and you’ll see in the red highlight—white female voters support Republicans while women of color are very heavy Democrats. And this all begins to change when the gender gap appears in the 1980s. It changes because women of voters—women of color voters enter the electorate about 20 years after the Voting Rights Act and 20 years after the Immigration and Nationality Act are a part of federal law. And they carry white women with them, only making white female voters look to be more Democratic when, in fact, white female voters have voted majority Republican for president in every election since 1948, except for two. And we can talk about those, if you like. You can guess which ones those are. But—and the second point is that the gender gap is a race gap.

And the final point that I’d like to make—and this is related to gender and race together—that every election has a unique electorate. So, even if you’re looking at stuff—what happens in ’20, and you’ll say, well, it should repeat itself in ’22. Well, no, because every election is a unique electorate. And it’s important to make the following distinctions—that is, between voter turnout, which is driven heavily by mobilization efforts, and the distinction between voter turnout and what drives that and what drives partisan candidate choice. Second thing to distinguish that’s important are national patterns from states and localities. So, you might see California voting in a very particular way versus, let’s say, Georgia. And finally, contours of the electorate change over time. And in particular, these are related not only to age, as John will talk about in a moment, but also voter restrictions, as Nazita will talk about, but also the change in the population as a function of young people coming in and older people dropping out. And then in addition to that, perhaps the most important element of change in the electorate over time is the introduction of voters from diverse backgrounds as a function of immigration to the United States.

So, I’ll just give you a tiny little bit of data. It’s just a pie chart of the race and gender composition of the 2020 electorate. And you can see that white women are the biggest chunk of the pie, right? That’s a massive piece—looks like strawberry rhubarb pie. They’re a little bit pinker than the white men, who are the dark red category, because they’re a little less Democratic—I’m sorry, a little less Republican. And all the blues are Black women, Latina women, Black men. And that, actually—second to the last one on the legend should say Latino men and other. So, you can see that about a quarter of the population of voters—it’s the electorate—are voters of color. They’re heavily Democratic whereas whites are heavily Republican. And, in particular, white women make up the biggest slice of the pie. So, if you see advertising being directed at white female voters, that’s why. They’re the biggest slice of the pie.

So, the gender gap now—I just want to give you a brief way of—let’s look at 2020. This is vote-cast data. This is the kind of official data of exit polls conducted by the Associated Press and other associated media organizations, the National Opinion Research Center. What you’ll see here is those who voted for Biden—just look at the middle column, voted for Biden—46% of men, 55% of women, which yields a big gender gap, right? That shows that the difference between women’s and men’s support of the Democratic candidate is plus 9%, right? And you’ll see that just the reverse is true, where men are more supportive of Trump, the Republican, than for Biden. But the gender gap is nevertheless there. And as, again, you can see in the second column over which the share of voters—that women make up the largest share of voters in the population, 53 to 47.

Now having said that, you think, oh, well, you know, everybody’s—women are Democratic. But that’s not the case, right? So, this is just a disaggregation of the vote. A vote choice is given to exit polls, which is a great scientific study of voters on Election Day, whether they voted in person or by mail, for example. And it disaggregates the proportion of who voted for Biden versus who voted for Trump by race and gender together. And what you’ll see is whites, whether they’re male or female, voted for Trump by a majority, 59-52, men versus women. And then African American men, women, Latino men, Latina women and all others are heavily Democratic. And I think it’s a pretty clear indicator of the second point that I wanted to make, which is that the gender gap is a race gap.

Now, over time, the last thing I’ll call your attention to is the share of voters column. That’s the first column. You’ll see that white females, again, are the biggest share of the pie, and that over time what’s happened is that the proportion of voters who are nonwhite and, in this case, minority has increased. And this has gone up, you know, really dramatically since the 1980s. And that’s part of the reason why you see the gender gap appearing in the first place. That’s all I’ve got. I’d be happy to take your questions after the other presentations.

RICK WEISS: Fantastic—a lot of information there for us to mull and get questions around and, of course, a huge teaser about what are the two elections where white women went Democratic? We won’t—we’ll just let that dangle for a while. And I suspect we will get a question about that to satisfy people’s curiosity in the Q&A. Meanwhile, over to you, Dr. Holbein.

JOHN HOLBEIN: OK. Can you all hear me?

RICK WEISS: Yes.

Age and voter turnout

JOHN HOLBEIN: Perfect. So, thanks so much for being here. I’m going to be talking to you today about some of the age dynamics of voter participation. And all of these things that I’m going to be talking about either are included in my recent book, Making Young Voters , or built off of that.

So. in the United States, it has been sort of a truism that young people are less likely to vote than older citizens. So, this is true going back all the way to the 1980s and even further to the 1970s, when 18-year-olds first gained the right to vote. They have consistently—young people have consistently voted at a lower rate than older citizens. So, you can see here this difference between older citizens and younger citizens, with older citizens being on the top and younger citizens being on the bottom, and the gap between those two groups’ rates of voter participation being plotted with the black line. So, as you can see, in 2020, youth voter participation went up to a level that we haven’t seen in decades. But still, that gap between younger and older voters remained relatively constant within the span of about a 20 to 30 percentage point voter participation gap between older and younger citizens.

And so, you might say to yourself, you know, what is this in context to other places, or is this just a phenomenon that happens all around the world? And the answer is, it’s not. So, the United States’ gap between older and younger citizens is somewhat unique relative to other countries. And in fact, the United States stands out in kind of the bad way, having one of the lowest rates of youth voter participation in the world and one of the largest age gaps in voter participation that we have data on. One other phenomenon that you should be aware of when you’re writing about youth voter participation is that many of the cleavages that we see among all adults are already present when young people are coming to the polls for the first time. So, we can see large gaps in voters—the voter participation among young voters by socioeconomic status—measures of socioeconomic status, education and income and also by racial categorizations, as well. And these differences between white and minority young voters, high- and low-income youth voters and high education status young voters versus lower—they’re large. These gaps are quite large.

So, the question is, why don’t more young people in the United States vote? The conventional wisdom here is that young people are apathetic, disinterested and disengaged. So, I don’t have to provide you with a summary of what everyone has ever said about this, but all you need to do is go to Google and Google in millennials are, and you’ll see some search result kind of like this. They’ve often been called the Me Me Me Generation. And this is a common thread, going all the way back to the days of Aristotle and to our more contemporary democracy, where people lament how disinterested, how apathetic, how turned off to social issues young people are. And the problem is that—or, no, the implication of this, if we want to address youth voter participation, is to increase political interest—right?—to make them care more about who is running for office, to care more about politics or public affairs more generally. That’s the approach we would want to take. The problem is that this conventional wisdom is not accurate, or at least not an accurate reflection of young people.

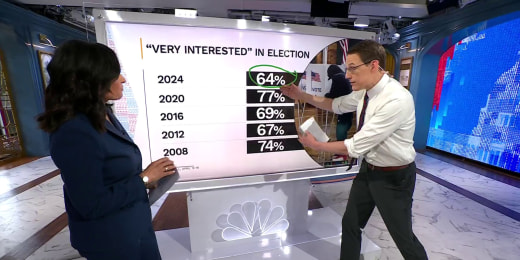

So, what I’m plotting here for you are two measures of political interest that we have from the American National Election Study, a highly reputable political science poll that’s used for many different research questions. And as you can see, across time and across all years, young people have always been very interested in politics. And that is capping out almost at the highest level possible, with 90-plus percent of young people regularly saying that they’re interested in elections. They care about who holds office. They intend to vote. And in fact, I just looked up the statistic for 2022. Again, close to 90% of young people say that they are going to vote in the upcoming midterm elections. The problem is that they don’t, right? So, there’s this persistent gap, what we term in the book the follow-through gap, right?

So, this is the gap—the difference between good intentions or a desire to participate in politics and actually following through. And it turns out that young people are nearly twice—or more than twice as likely to not follow through on their intention to participate. So, it’s less about a problem about voter apathy. They say that they want to vote. They say they plan to vote. They say they care about the issues that are on the ballot, but they just don’t follow through. And there are a number of reasons why that’s the case. And these tie in to some of the solutions that we have in the—that are discussed in our book for addressing youth voter participation. So, on the one side, making voting easier increases the chances that young people will show up and follow through and actually cast the ballot and follow through on their intention, right? So, Nazita is going to talk a little bit more about some of those specific reforms. We believe the preview of what we find is that making registration, specifically, easier helps young people disproportionately.

And the second piece of this is trying to focus on civics education reforms that put a meaningful change or that change meaningfully the way in which young people approach politics. So, rather than hitting them over the head with facts and figures about American government and politics, mostly historical, and forcing them to memorize those facts, getting them more actively involved in a more active form of learning works to increase youth voter participation. So, we see this in models that were—are starting to pop up throughout the United States and elsewhere that are trying to rethink civics education. So, the Democracy Prep network of charter schools is trying a new model of youth civics education in the which young people are not just memorizing facts and figures about American democracy, but they’re getting involved in politics. They’re meeting with elected officials. They’re help canvassing to mobilize people who are old enough to register and to vote, even long before they’re able to do that themselves. And what we see is from good evidence-based research that that increases the chances that young people who are coming through those programs will vote later on in their lives. And it’s a fairly large increase that we see.

The second thing that schools can do as we’re rethinking civics education is to help them overcome this barrier of voter registration. So, we see that when schools do this, when they help their young people register—this evidence comes from a program called the First-Time Voter Program, which helped do that across the United States—that that increases youth voter participation as well. The final thing that I want to note here is something that I mentioned earlier—is that the choke point seems to be, for many young people, the voter registration step of the process. In our research, we interviewed many young people across the United States, and they said again and again, things like voter registration—it’s archaic. It’s complex. I’m worried about making mistakes. Many young people do make mistakes on their voter registration forms, and they see it as costly and time-intensive. So, many of the reforms that make voter registration easier that are on the ballot—we have less evidence about automatic voter registration, although I’m happy to talk a little bit about that. But from historical evidence we have, reforms that make registration easier, such as online registration, pre-registration of 16-, 17-year-olds and same-day registration increase the chances that young people will vote. So, with that, I’ll stop and say thanks and hand the microphone over to Nazita.

RICK WEISS: Fascinating and, again, a lot of great data there to work with—we’ll continue on over to Dr. Lajevardi.

Voter ID laws and voter turnout

NAZITA LAJEVARDI: Hi, everyone. It’s a pleasure to be here with you. I am going to talk a little bit about voter ID laws and voter turnout. So, I think it’s probably not surprising to those of us here today that voting is, of course, one of the most centermost tenets of American democracy. It’s important. It allows citizens to choose their leaders, to influence policy and ultimately shape the democracy in which they reside. It is also the case that, when citizens do not vote, representatives can ignore them. They can ignore their preferences. And so therefore, the laws that come about and that can regulate who can and cannot vote in the course—you know, in elections has been subject to debate throughout the course of American democracy. But it remains really central to our debate today about who can and cannot vote.

The reality is, of course, as we all know, that the United States has long excluded groups from participating in the franchise. I’m happy to talk more throughout history about these different types of barriers that once existed. But for now, we’re going to kind of jump ahead to the post-civil rights era where there was continued resistance, and there has been continued resistance that is aimed to curtail the voting rights of Black Americans in particular, but other racial and ethnic minorities. It is true that Black Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities have the vote, but there are efforts to reduce the influence of that vote. Whether intentional or not, we have to take a deep dive and have a look at those. The focus today, of course, is going to be on voter ID laws, which are a form of voter registration requirement. But there are many different ways in which we’ve seen resistance in this post-1965 era. You can think about gerrymandering at large elections, where polling locations are, etc., etc. But today, the focus is going to be on voter ID laws. Today, they represent one of the country’s most important barriers to voting and thus, I would argue, one of the nation’s most important civil rights issues.

So, voter ID laws—what are they? These are laws that require a person to provide some form of official identification before they are allowed either to register to vote or to receive a ballot, or to actually cast a ballot on Election Day. As of 2022, 35 states currently have a voter ID law in place. But the reality is, is that prior to 2006, no state actually required identification in order for your vote to count. These laws have proliferated across the country. They’ve become stricter. But the reality is, is that the types and severity of these laws, they vary by state. They vary in the years that they’re introduced. And so, they’re—you know, tracing them over time and trying to assess the impacts can be a bit tricky. We’ll get through the—we’ll get to the methodological issues in a moment. There is, of course, arguments on both sides. So, proponents of voter ID laws argue that these are warranted, that they do not really reduce the participation of citizens. And we should really be thinking about voter fraud here. They’re helpful in reducing voter fraud, and this could potentially be a widespread phenomenon. And so, these laws at least help to verify the identification of voters in an increasingly contentious election environment.

Opponents of voter ID laws argue that these are burdensome and that they are effective barriers, that they place material burdens on segments of the population and that, frankly, they operate like poll taxes because you do need means, in order to participate, to be able to get the right type of identification in order to participate in elections. There is a map of voter ID laws that’s currently in effect by state. I urge you to go to the link that I have in my slides here. They’re—the map is created by the National Conference of State Legislatures. What you’ll see there is that there are five categories of voter ID laws that they classify. You can have strict photo ID, strict non-photo ID, non-strict photo ID, non-strict non-photo ID or no photo ID law. The reality is, is that no state—no two state laws are identical. And there can be quite a bit of overlap across categories. So, the NCSL does provide really a simplified way of categorizing these laws. What you should know is that these laws vary typically on two dimensions. So, whether the state asks for a photo ID or whether it accepts ID without a photo as well, as well as what actions are available to the voter who does not have an ID. That’s an important component here. The strictest type of photo ID laws are laws that require registrants who are attempting to vote on Election Day to present a government-issued photo ID as well as qualifying identification at a time after they cast their ballot in order for their vote to count.

So, Bernard Fraga, in his book, The Turnout Gap , in 2018, he provides a really instructive example of how a strict photo ID law could be enforced in a state like Indiana. So, a voter in Indiana who doesn’t have the right type of ID who wishes to have a provisional ballot counted must within a week after the election visit the county election board in person and either produce photo ID or sign an affidavit indicating that they are indigent or have a religious objection to being photographed. The reality is, of course, that not all registrants have this type of photo ID. And scholars have spent a lot of time to try to identify and measure the impact of voter ID laws on turnout, especially minority turnout. And this is where my qualification comes out. We need to talk about methodology and voter ID laws. These laws are not being introduced in a vacuum.

So, Highton, 2017, notes that it is not possible to design and conduct an experiment where we randomize some states to have a strict photo ID law and some states to not have these laws. And as such, scholars are really trying to measure these effects of these laws in a number of different ways. These studies—they differ in their findings, in the samples that they look to, in their results and their methods. But on balance, most of them are generally discovering that the very, very strictest forms of strict ID laws—they do have negative effects on voter turnout.

Now, again, the literature is always evolving, and it’s always changing. But I think it’s important to put out there that we need to have many, many studies in order to evaluate how these laws are impacting voter turnout. I’m going to draw your attention to some of these studies. I personally have co-authored three studies that have looked at this question. Across all three, we find a negative effect on—a persistent negative significant effect on minority voter turnout. Our work is not alone. So, Fraga, 2018, also finds similar effects. I have a link here for you guys to have a look at these studies. This work is supplemented with surveys looking in particular states like Wisconsin or in other surveys like the Current Population Survey.

Fraga and Miller, 2022, a very recent paper that was just published, looks at Texas, and I think this is a very clever design. Texas was supposed to have their strict ID law go into effect, but in 2016 a court actually stayed that decision and allowed people without qualifying identification to cast ballots. But they had people fill out a declaration explaining why they didn’t have the right type of ID. And so, Fraga and Miller basically estimate that about 16,000 Texans would have been barred from casting a ballot in that election. And they find that these voters are more likely to be Black and Latinx. So, it’s not just that voter ID laws suppress turnout. There is other scholarship that matters here, too. It is also the case that minorities are less likely to possess valid forms of ID that are necessary to comply with these statutes. And so, the material burdens of actually acquiring an ID fall harder on them.

So, there’s a number of studies here that sort of delve into that. You’re free to have a look at those. And it is also the case that minorities are more likely than white Americans to be asked to present an ID at the polls. So, these laws are being applied differentially by race as well. It’s not just the existence of these laws. It is also the case that poll workers are interpreting them and executing them differentially as well. I’m just going to conclude about, you know, are we going to get voting rights legislation soon? I’m sorry to inform you that, no, we’re not. It doesn’t look so good. Hopefully the midterms will help us get some more movement, but it seems quite doubtful. I want to draw your attention to HR 1, as well as the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, that had made some efforts to try to strengthen our voting rights legislation. The John Lewis Voting Rights Act in particular was trying to restore Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act and was going to have a preclearance requirement for any change made to a voter ID law that was going to make ID law stricter. And so, that’s a bit of a depressing place to conclude. But I think it’s important to talk about the fact that, you know, in order to have a more representative democracy, you know, we have to consider the barriers that are enacted through these legal mechanisms.

What is being done well in press coverage of these issues, and where is there room for improvement?

RICK WEISS: Fantastic. Thank you, Dr. Lajevardi for a very data-rich presentation. I’ll remind reporters attending that these slides will go up on our website after the briefing, and you’ll be able to click on those various links and do that facilitated research that can help you with your story preparation. So, we’re going to start with the Q&A now. I’ll remind reporters that you can put your questions in the Q&A icon at the bottom of your screen. But while that starts to populate, I like to start things off here with my own question, which is meant to be something of practical helpfulness and value to the reporters attending. And I’d like to ask each of our speakers to answer the question of whether there’s something that they would point to from their experience looking at news stories on this topic that reporters could either do better than they’re doing now or maybe something that they’re doing great that you want to applaud them for. And why don’t we just go around the horn and see what kind of advice each of our speakers might have for reporters on this beat? Starting with you, Jane.

JANE JUNN: Great. Thank you, Rick. Looking forward to your questions. And I am going to talk about one of the things that I think reporters do really well, and that is talk to voters in the areas where they’re reporting from. I mean, as research scholars, most of us are—I mean, some of us are pretty close in to collecting data from individuals. But generally speaking, most of the data that you’ve looked at—and I think that’s true for all three of these academic presentations today—are based on large studies of, you know, thousands of people, and we aggregate them all into little data points, and then we give you slides which show points over time. What we lose in that is really the fine grain reasons for why people say that they do what they did and why they came out and all the very specific things that make politics interesting and make politics really about people and not just about national trends or what’s going to happen in a specific election or Supreme Court decision.

So, I think one of the things that journalists do exceptionally well is talk to regular people about what they think about politics and why they’re doing what they’re doing. And without that, I think that we would be much poorer off for it as scholars. I rely heavily on media reports from voters. I mean, I talk to as many people as I can, but it’s not nearly what we can cover across the whole 50 states and cities, rural areas and the United States as a whole. So, hats off to you for bringing us the truth from ordinary people about what they like and don’t like about politics.

RICK WEISS: Great. Thank you. John.

JOHN HOLBEIN: Great. Thanks. Yeah. I would just echo what Jane said, that it’s really, really valuable to get these stories, especially of young people and the challenges that they face, and I rely on that as well. I think one of the challenges about reporting on youth voting participation is that many of the things that influence and shape whether or not young people are going to cast the ballot are happening in between elections, right? So, they’re being exposed to civics education curricula. They’re being exposed to voter registration systems and have to—they have to navigate. They’re moving. They’re—you know, the things that are happening to young people don’t start and stop with a political campaign. And yet many of the—most of the attention that we get towards youth voter participation being so low is only something that comes up every four, two years. Whereas the challenges that are standing in the way of young people are ever-present.

The other thing is kind of low-hanging fruit, and it’s kind of a—it’s a caricature. But we do see this narrative show up that the reason why young people vote is that they just don’t care, that they’re just apathetic. They’re not interested in politics—that there’s just something fundamentally, morally wrong with the levels of how plugged-in young people are to politics. And that just doesn’t square with the data. So, I would say that those two things are two areas that could be improved. I realize the timing one is difficult because when readership cares about this is when elections are happening. But in as much as we can think about youth voter participation more than just during elections, but as a fundamental structural issue that we face in American politics, it will be to our benefit.

RICK WEISS: That’s some advice that should go to editors in addition to reporters. We’ll see if we can send some of that upstream. Nazita, over to you.

NAZITA LAJEVARDI: Thank you. Yeah, I guess, I think a lot of the reporting on voter ID laws sort of echoes what politicians and what political elites have to say about them. And any sort of reporting that does turn to scholarship often focuses on one study. And I was trying to make clear that there is a diversity of studies out there and that, you know, as scholars, you know, we’re sort of really trying to understand this issue, but it’s going to take many studies, you know, in order to draw more firm conclusions.