Understanding Creativity

- Posted June 25, 2020

- By Emily Boudreau

Understanding the learning that happens with creative work can often be elusive in any K–12 subject. A new study from Harvard Graduate School of Education Associate Professor Karen Brennan , and researchers Paulina Haduong and Emily Veno, compiles case studies, interviews, and assessment artifacts from 80 computer science teachers across the K–12 space. These data shed new light on how teachers tackle this challenge in an emerging subject area.

“A common refrain we were hearing from teachers was, ‘We’re really excited about doing creative work in the classroom but we’re uncertain about how to assess what kids are learning, and that makes it hard for us to do what we want to do,’” Brennan says. “We wanted to learn from teachers who are supporting and assessing creativity in the classroom, and amplify their work, and celebrate it and show what’s possible as a way of helping other teachers.”

Create a culture that values meaningful assessment for learning — not just grades

As many schools and districts decided to suspend letter grades during the pandemic, teachers need to help students find intrinsic motivation. “It’s a great moment to ask, ‘What would assessment look like without a focus on grades and competition?’” says Veno.

Indeed, the practice of fostering a classroom culture that celebrates student voice, creativity, and exploration isn’t limited to computer science. The practice of being a creative agent in the world extends through all subject areas.

The research team suggests the following principles from computer science classrooms may help shape assessment culture across grade levels and subject areas.

Solicit different kinds of feedback

Give students the time and space to receive and incorporate feedback. “One thing that’s been highlighted in assessment work is that it is not about the teacher talking to a student in a vacuum,” says Haduong, noting that hearing from peers and outside audience members can help students find meaning and direction as they move forward with their projects.

- Feedback rubrics help students receive targeted feedback from audience members. Additionally, looking at the rubrics can help the teacher gather data on student work.

Emphasize the process for teachers and students

Finding the appropriate rubric or creating effective project scaffolding is a journey. Indeed, according to Haduong, “we found that many educators had a deep commitment to iteration in their own work.” Successful assessment practices conveyed that spirit to students.

- Keeping design journals can help students see their work as it progresses and provides documentation for teachers on the student’s process.

- Consider the message sent by the form and aesthetics of rubrics. One educator decided to use a handwritten assessment to convey that teachers, too, are working on refining their practice.

Scaffold independence

Students need to be able to take ownership of their learning as virtual learning lessens teacher oversight. Students need to look at their own work critically and know when they’ve done their best. Teachers need to guide students in this process and provide scaffolded opportunities for reflection.

- Have students design their own assessment rubric. Students then develop their own continuum to help independently set expectations for themselves and their work.

Key Takeaways

- Assessment shouldn’t be limited to the grade a student receives at the end of the semester or a final exam. Rather, it should be part of the classroom culture and it should be continuous, with an emphasis on using assessment not for accountability or extrinsic motivation, but to support student learning.

- Teachers can help learners see that learning and teaching are iterative processes by being more transparent about their own efforts to reflect and iterate on their practices.

- Teachers should scaffold opportunities for students to evaluate their own work and develop independence.

Additional Resources

- Creative Computing curriculum and projects

- Karen Brennan on helping kids get “unstuck”

- Usable Knowledge on how assessment can help continue the learning process

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Strategies for Leveling the Educational Playing Field

New research on SAT/ACT test scores reveals stark inequalities in academic achievement based on wealth

How to Help Kids Become Skilled Citizens

Active citizenship requires a broad set of skills, new study finds

Student Testing, Accountability, and COVID

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

What is creativity in education?

- Curriculum integration

- Health, PE & relationships

- Literacy (primary level)

- Practice: early literacy

- Literacy (secondary level)

- Mathematics

Diverse learners

- Gifted and talented

- Neurodiversity

- Speech and language differences

- Trauma-informed practice

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Science of learning

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulation

- Social connection

- Social-emotional learning

- Principles of assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Measuring progress

- Self-assessment

Instruction and pedagogy

- Classroom management

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Co-operative learning

- High-expectation teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Planning and instructional design

- Questioning

Relationships

- Home-school partnerships

- Student wellbeing NEW

- Transitions

Teacher development

- Instructional coaching

- Professional learning communities

- Teacher inquiry

- Teacher wellbeing

- Instructional leadership

- Strategic leadership

Learning environments

- Flexible spaces

- Neurodiversity in Primary Schools

- Neurodiversity in Secondary Schools

Human beings have always been creative. The fact that we have survived on the planet is testament to this. Humans adapted to and then began to modify their environment. We expanded across the planet into a whole range of climates. At some point in time we developed consciousness and then language. We began to question who we are, how we should behave, and how we came into existence in the first place. Part of human questioning was how we became creative.

The myth that creativity is only for a special few has a long, long history. For the Ancient Chinese and the Romans, creativity was a gift from the gods. Fast forward to the mid-nineteenth century and creativity was seen as a gift, but only for the highly talented, romantically indulgent, long-suffering and mentally unstable artist. Fortunately, in the 1920s the field of science began to look at creativity as a series of human processes. Creative problem solving was the initial focus, from idea generation to idea selection and the choice of a final product. The 1950s were a watershed moment for creativity. After the Second World War, the Cold War began and competition for creative solutions to keep a technological advantage was intense. It was at this time that the first calls for STEM in education and its associated creativity were made. Since this time, creativity has been researched across a whole range of human activities, including maths, science, engineering, business and the arts.

The components of creativity

So what exactly is creativity? In the academic field of creativity, there is broad consensus regarding the definition of creativity and the components which make it up. Creativity is the interaction between the learning environment, both physical and social, the attitudes and attributes of both teachers and students, and a clear problem-solving process which produces a perceptible product (that can be an idea or a process as well as a tangible physical object). Creativity is producing something new, relevant and useful to the person or people who created the product within their own social context. The idea of context is very important in education. Something that is very creative to a Year One student – for example, the discovery that a greater incline on a ramp causes objects to roll faster – would not be considered creative in a university student. Creativity can also be used to propose new solutions to problems in different contexts, communities or countries. An example of this is having different schools solve the same problem and share solutions.

Creativity is an inherent part of learning. Whenever we try something new, there is an element of creativity involved. There are different levels of creativity, and creativity develops with both time and experience. A commonly cited model of creativity is the 4Cs [i] . At the mini-c level of creativity, what someone creates might not be revolutionary, but it is new and meaningful to them. For example, a child brings home their first drawing from school. It means something to the child, and they are excited to have produced it. It may show a very low level of skill but create a high level of emotional response which inspires the child to share it with their parents.

The little-c level of creativity is one level up from the mini-c level, in that it involves feedback from others combined with an attempt to build knowledge and skills in a particular area. For example, the painting the child brought home might receive some positive feedback from their parents. They place it on the refrigerator to show that it has value, give their child a sketchbook, and make some suggestions about how to improve their drawing. In high school the student chooses art as an elective and begins to receive explicit instruction and assessed feedback. In terms of students at school, the vast majority of creativity in students is at the mini-c and little-c level.

The Pro-c level of creativity in schools is usually the realm of teachers. The teacher of art in this case finds a variety of pedagogic approaches which enhance the student artist’s knowledge and skills in art as well as building their creative competencies in making works of art. They are a Pro-c teacher. The student will require many years of deliberate practice and training along with professional levels of feedback, including acknowledgement that their work is sufficiently new and novel for them to be considered a creative professional artist at the pro-c level.

The Big-C level of creativity is the rarefied territory of the very few. To take this example to the extreme, the student becomes one of the greatest artists of all time. After they are dead, their work is discussed by experts because their creativity in taking art to new forms of expression is of the highest level. Most of us operate at the mini-c and little-c level with our hobbies and activities. They give us great satisfaction and enjoyment and we enjoy building skills and knowledge over time. Some of us are at the pro-c level in more than one area.

The value of creativity in education

Creativity is valuable in education because it builds cognitive complexity. Creativity relies on having deep knowledge and being able to use it effectively. Being creative involves using an existing set of knowledge or skills in a particular subject or context to experiment with new possibilities in the pursuit of valued outcomes , thus increasing both knowledge and skills. It develops over time and is more successful if the creative process begins at a point where people have at least some knowledge and skills. To continue the earlier example of the ramp, a student rolling a ball down an incline may notice that the ball goes faster if they increase the incline, and slower if they decrease it. This discovery may lead to other possibilities – the student might then go on to observe how far the ball rolls depending on the angle of the incline, and then develop some sort of target for the ball to reach. What started as play has developed in a way that builds the student’s knowledge, skills and reasoning. It represents the beginning of the scientific method of trial and error in experimentation.

Creativity is not just making things up. For something to meet the definition of creativity, it must not only be new but also relevant and useful. For example, if a student is asked to make a new type of musical instrument, one made of salami slices may be original and interesting, but neither relevant nor useful. (On the other hand, carrots can make excellent recorders). Creativity also works best with constraints, not open-ended tasks. For example, students can be given a limit to the number of lines used when writing a poem, or a set list of ingredients when making a recipe. Constrained limits lead to what cognitive scientists call desirable difficulties as students need to make more complex decisions about what they include and exclude in their final product. A common STEM example is to make a building using drinking straws but no sticky tape or glue. Students need to think more deeply about how the various elements of a building connect in order for the building to stand up.

Creativity must also have a result or an outcome . In some cases the result may be a specific output, such as the correct solution to a maths problem, a poem in the form of a sonnet, or a scientific experiment to demonstrate a particular type of reaction. As noted above, outputs may also be intangible: they might be an idea for a solution or a new way of looking at existing knowledge and ideas. The outcome of creativity may not necessarily be pre-determined and, when working with students, generating a specific number of ideas might be a sufficient creative outcome.

Myths about creativity

It is important that students are aware of the components that make up creativity, but it is also critical that students understand what creativity is not, and that the notion of creativity has been beset by a number of myths. The science of creativity has made great progress over the last 20 years and research has dispelled the following myths:

- Creativity is only for the gifted

- Creativity is only for those with a mental illness

- Creativity only lives in the arts

- Creativity cannot be taught

- Creativity cannot be learned

- Creativity cannot be assessed

- Schools kill creativity in their students

- Teachers do not understand what creativity is

- Teachers do not like creative students

The science of creativity has come a long way from the idea of being bestowed by the gods of ancient Rome and China. We now know that creativity can be taught, learned and assessed in schools. We know that everyone can develop their creative capacities in a wide range of areas, and that creativity can develop from purely experiential play to a body of knowledge and skills that increases with motivation and feedback.

Creativity in education

The world of education is now committed to creativity. Creativity is central to policy and curriculum documents in education systems from Iceland to Estonia, and of course New Zealand. The origins of this global shift lie in the 1990s, and it was driven predominantly by economics rather than educational philosophy.

There has also been a global trend in education to move from knowledge acquisition to competency development. Creativity often is positioned as a competency or skill within educational frameworks. However, it is important to remember that the incorporation of competencies into a curriculum does not discount the importance of knowledge acquisition. Research in cognitive science demonstrates that students need fundamental knowledge and skills. Indeed, it is the sound acquisition of knowledge that enables students to apply it in creative ways . It is essential that teachers consider both how they will support their students to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills in their learning area as well as the opportunities they will provide for applying this knowledge in ways that support creativity. In fact, creativity requires two different sets of knowledge: knowledge and skills in the learning area, and knowledge of and skills related to the creative process, from idea generation to idea selection, as well as the appropriate attitudes, attributes and environment.

Supporting students to be creative

In order for teachers to support students to be creative, they should attend to four key areas. Firstly, creativity needs an appropriate physical and social environment . Students need to feel a sense of psychological safety when being creative. The role of the teacher is to ensure that all ideas are listened to and given feedback in a respectful manner. In terms of the physical environment, a set of simple changes rather than a complete redesign of classrooms is required: modifying the size and makeup of student groups, working on both desks and on whiteboards, or taking students outside as part of the idea generation process can develop creative capacity. Even something as simple as making students more aware of the objects and affordances which lie within a classroom may help with the creative process.

Secondly, teachers can support students to develop the attitudes and attributes required for creativity , which include persistence, discipline, resilience, and curiosity. Students who are more intellectually curious are open to new experiences and can look at problems from multiple perspectives, which builds creative capacity. In maths, for example, this can mean students being shown three or four different ways to solve a problem and selecting the method that best suits them. In Japan, students are rewarded for offering multiple paths to a solution as well as coming up with the correct answer.

Thirdly, teachers can support the creative process . It begins with problem solving, or problem posing, and moves on to idea generation. There are a number of methods which can be used when generating ideas such as brainstorming, in which as many ideas as possible are generated by the individual or by a group. Another effective method, which has the additional benefit of showing the relationships between the ideas as they are generated, is mind-mapping. For example, rather than looking at possible causes of World War Two as a list, it might be better to categorise them into political, social and economic categories using a mind map or some other form of graphic organiser. This creative visual representation may provide students with new and useful insights into the causes of the war. Students may also realise that there are more categories that need to be considered and added, thus allowing them to move from surface to deep learning as they explore relationships rather than just recalling facts. Remember that creativity is not possible without some knowledge and skills in that subject area. For instance, proposing that World War Two was caused by aliens may be considered imaginative, but it is definitely not creative.

The final element to be considered is that of the outcomes – the product or results – of creativity . However, as with many other elements of education, it may be more useful to formatively assess the process which the students have gone through rather than the final product. By exploring how students generated ideas, whether the method of recording ideas was effective, whether the final solutions were practical, and whether they demonstrated curiosity or resilience can often be more useful than merely grading the final product. Encouraging the students to self-reflect during the creative process also provides students with increased skills in metacognition, as well as having a deeper understanding of the evolution of their creative competencies. It may in fact mean that the final grade for a piece of work may take into account a combination of the creative process as observed by the teacher, the creative process as experienced and reported by the student, and the final product, tangible or intangible.

Collard, P., & Looney, J. (2014). Nurturing creativity in education . European Journal of Education, 49 (3), 348-364.

Craft, A. (2001). An analysis of research and literature on creativity in education : Report prepared for the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

Runco, M. (2008). Creativity and education . New Horizons in Education, 56 (1), 96-104.

[i] Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity . Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1-12.

By Tim Patston

PREPARED FOR THE EDUCATION HUB BY

Dr Tim Patston

Dr Tim Patston is a researcher and educator with more than thirty years’ experience working with Primary, Secondary and Tertiary education providers and currently is the leader of consultancy activities for C reative Actions . He also is a senior adjunct at the University of South Australia in UniSA STEM and a senior fellow at the University of Melbourne in the Graduate School of Education. He publishes widely in the field of Creative Education and the development of creative competencies and is the featured expert on creativity in the documentary Finding Creativity, to be released in 2021.

Download this resource as a PDF

Please provide your email address and confirm you are downloading this resource for individual use or for use within your school or ECE centre only, as per our Terms of Use . Other users should contact us to about for permission to use our resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools I agree to abide by The Education Hub's Terms of Use.

Did you find this article useful?

If you enjoyed this content, please consider making a charitable donation.

Become a supporter for as little as $1 a week – it only takes a minute and enables us to continue to provide research-informed content for teachers that is free, high-quality and independent.

Become a supporter

Get unlimited access to all our webinars

Buy a webinar subscription for your school or centre and enjoy savings of up to 25%, the education hub has changed the way it provides webinar content, to enable us to continue creating our high-quality content for teachers., an annual subscription of just nz$60 per person gives you access to all our live webinars for a whole year, plus the ability to watch any of the recordings in our archive. alternatively, you can buy access to individual webinars for just $9.95 each., we welcome group enrolments, and offer discounts of up to 25%. simply follow the instructions to indicate the size of your group, and we'll calculate the price for you. , unlimited annual subscription.

- All live webinars for 12 months

- Access to our archive of over 80 webinars

- Personalised certificates

- Group savings of up to 25%

The Education Hub’s mission is to bridge the gap between research and practice in education. We want to empower educators to find, use and share research to improve their teaching practice, and then share their innovations. We are building the online and offline infrastructure to support this to improve opportunities and outcomes for students. New Zealand registered charity number: CC54471

We’ll keep you updated

Click here to receive updates on new resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools

Follow us on social media

Like what we do please support us.

© The Education Hub 2024 All rights reserved | Site design: KOPARA

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

Privacy Overview

Thanks for visiting our site. To show your support for the provision of high-quality research-informed resources for school teachers and early childhood educators, please take a moment to register.

Thanks, Nina

What creativity really is - and why schools need it

Associate Professor of Psychology and Creative Studies, University of British Columbia

Disclosure statement

Liane Gabora's research is supported by a grant (62R06523) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Although educators claim to value creativity , they don’t always prioritize it.

Teachers often have biases against creative students , fearing that creativity in the classroom will be disruptive. They devalue creative personality attributes such as risk taking, impulsivity and independence. They inhibit creativity by focusing on the reproduction of knowledge and obedience in class.

Why the disconnect between educators’ official stance toward creativity, and what actually happens in school?

How can teachers nurture creativity in the classroom in an era of rapid technological change, when human innovation is needed more than ever and children are more distracted and hyper-stimulated ?

These are some of the questions we ask in my research lab at the Okanagan campus of the University of British Columbia. We study the creative process , as well as how ideas evolve over time and across societies. I’ve written almost 200 scholarly papers and book chapters on creativity, and lectured on it worldwide. My research involves both computational models and studies with human participants. I also write fiction, compose music for the piano and do freestyle dance.

What is creativity?

Although creativity is often defined in terms of new and useful products, I believe it makes more sense to define it in terms of processes. Specifically, creativity involves cognitive processes that transform one’s understanding of, or relationship to, the world.

There may be adaptive value to the seemingly mixed messages that teachers send about creativity. Creativity is the novelty-generating component of cultural evolution. As in any kind of evolutionary process, novelty must be balanced by preservation.

In biological evolution, the novelty-generating components are genetic mutation and recombination, and the novelty-preserving components include the survival and reproduction of “fit” individuals. In cultural evolution , the novelty-generating component is creativity, and the novelty-preserving components include imitation and other forms of social learning.

It isn’t actually necessary for everyone to be creative for the benefits of creativity to be felt by all. We can reap the rewards of the creative person’s ideas by copying them, buying from them or simply admiring them. Few of us can build a computer or write a symphony, but they are ours to use and enjoy nevertheless.

Inventor or imitator?

There are also drawbacks to creativity . Sure, creative people solve problems, crack jokes, invent stuff; they make the world pretty and interesting and fun. But generating creative ideas is time-consuming. A creative solution to one problem often generates other problems, or has unexpected negative side effects.

Creativity is correlated with rule bending, law breaking, social unrest, aggression, group conflict and dishonesty. Creative people often direct their nurturing energy towards ideas rather than relationships, and may be viewed as aloof, arrogant, competitive, hostile, independent or unfriendly.

Also, if I’m wrapped up in my own creative reverie, I may fail to notice that someone else has already solved the problem I’m working on. In an agent-based computational model of cultural evolution , in which artificial neural network-based agents invent and imitate ideas, the society’s ideas evolve most quickly when there is a good mix of creative “inventors” and conforming “imitators.” Too many creative agents and the collective suffers. They are like holes in the fabric of society, fixated on their own (potentially inferior) ideas, rather than propagating proven effective ideas.

Of course, a computational model of this sort is highly artificial. The results of such simulations must be taken with a grain of salt. However, they suggest an adaptive value to the mixed signals teachers send about creativity. A society thrives when some individuals create and others preserve their best ideas.

This also makes sense given how creative people encode and process information. Creative people tend to encode episodes of experience in much more detail than is actually needed. This has drawbacks: Each episode takes up more memory space and has a richer network of associations. Some of these associations will be spurious. On the bright side, some may lead to new ideas that are useful or aesthetically pleasing.

So, there’s a trade-off to peppering the world with creative minds. They may fail to see the forest for the trees but they may produce the next Mona Lisa.

Innovation might keep us afloat

So will society naturally self-organize into creators and conformers? Should we avoid trying to enhance creativity in the classroom?

The answer is: No! The pace of cultural change is accelerating more quickly than ever before. In some biological systems, when the environment is changing quickly, the mutation rate goes up. Similarly, in times of change we need to bump up creativity levels — to generate the innovative ideas that will keep us afloat.

This is particularly important now. In our high-stimulation environment, children spend so much time processing new stimuli that there is less time to “go deep” with the stimuli they’ve already encountered. There is less time for thinking about ideas and situations from different perspectives, such that their ideas become more interconnected and their mental models of understanding become more integrated.

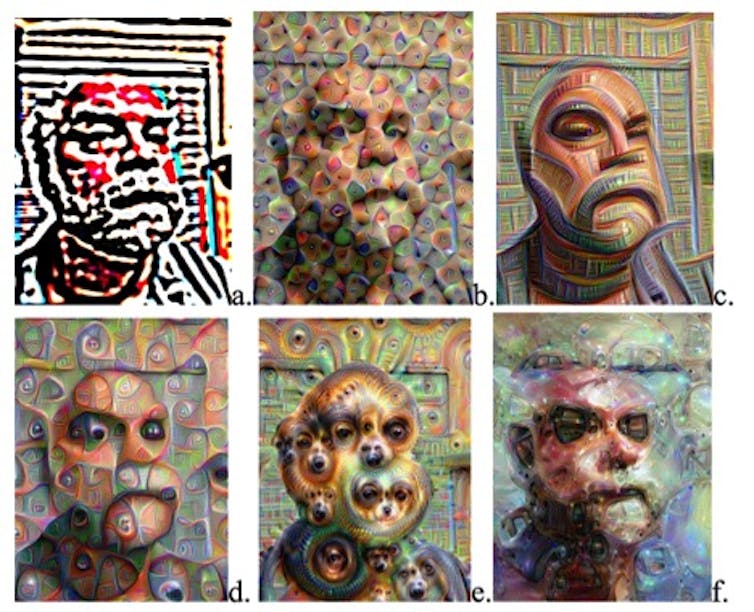

This “going deep” process has been modeled computationally using a program called Deep Dream , a variation on the machine learning technique “Deep Learning” and used to generate images such as the ones in the figure below.

The images show how an input is subjected to different kinds of processing at different levels, in the same way that our minds gain a deeper understanding of something by looking at it from different perspectives. It is this kind of deep processing and the resulting integrated webs of understanding that make the crucial connections that lead to important advances and innovations.

Cultivating creativity in the classroom

So the obvious next question is: How can creativity be cultivated in the classroom? It turns out there are lots of ways ! Here are three key ways in which teachers can begin:

Focus less on the reproduction of information and more on critical thinking and problem solving .

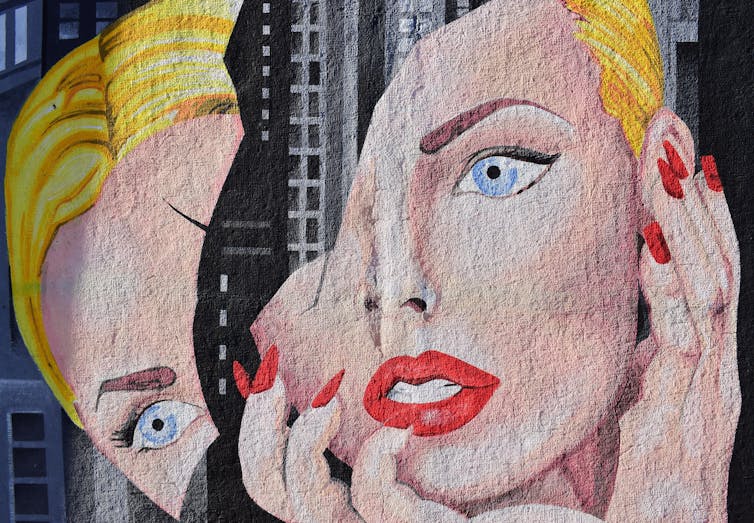

Curate activities that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, such as by painting murals that depict biological food chains, or acting out plays about historical events, or writing poems about the cosmos. After all, the world doesn’t come carved up into different subject areas. Our culture tells us these disciplinary boundaries are real and our thinking becomes trapped in them.

Pose questions and challenges, and follow up with opportunities for solitude and reflection. This provides time and space to foster the forging of new connections that is so vital to creativity.

- Cultural evolution

- Creative pedagody

- Teaching creativity

- Creative thinking

- Back to School 2017

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Creativity in education.

- Anne Harris Anne Harris RMIT University

- and Leon De Bruin Leon De Bruin RMIT University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.383

- Published online: 26 April 2018

Creativity is an essential aspect of teaching and learning that is influencing worldwide educational policy and teacher practice, and is shaping the possibilities of 21st-century learners. The way creativity is understood, nurtured, and linked with real-world problems for emerging workforces is significantly changing the ways contemporary scholars and educators are now approaching creativity in schools. Creativity discourses commonly attend to creative ability, influence, and assessment along three broad themes: the physical environment, pedagogical practices and learner traits, and the role of partnerships in and beyond the school. This overview of research on creativity education explores recent scholarship examining environments, practices, and organizational structures that both facilitate and impede creativity. Reviewing global trends pertaining to creativity research in this second decade of the 21st century, this article stresses for practicing and preservice teachers, schools, and policy makers the need to educationally innovate within experiential dimensions, priorities, possibilities, and new kinds of partnerships in creativity education.

- creative ecologies

- creative environments

- creative industries

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.15.189]

- 185.66.15.189

Character limit 500 /500

Advertisement

How does a creative learning environment foster student creativity? An examination on multiple explanatory mechanisms

- Open access

- Published: 04 August 2020

- Volume 41 , pages 4667–4676, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mudan Fan 1 &

- Wenjing Cai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0000-5851 2 , 3

20k Accesses

14 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Scholars and educators have acknowledged the importance of the learning environment, especially the creative learning environment, on student creativity. However, the current understanding is far from complete to paint a clear picture of how a creative learning environment can stimulate students’ creative outcomes in the classroom. Drawing on Amabile’s componential theory of creativity, the present research aims to test how a creative learning environment can foster undergraduate creativity through three distinct mechanisms (i.e., learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing). A total of 431 students and their teachers from a Chinese university completed questionnaires. The results generally supported the theoretical model in which a creative learning environment is significantly associated with student creativity by enhancing students’ learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing. Implications for theory and educational practice, limitations of the present study, and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Speaking of Creativity: Frameworks, Models, and Meanings

Anchoring the creative process within a self-regulated learning framework: inspiring assessment methods and future research.

Lisa DaVia Rubenstein, Gregory L. Callan & Lisa M. Ridgley

Learning Environments for Academics: Reintroducing Scientists to the Power of Creative Environment

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creativity is becoming increasingly important in modern society (Beghetto and Kaufman 2014 ; Richardson and Mishra 2018 ; Yeh et al. 2012 ). Specifically, as students are the key drivers of societal development, universities around the world have been taking on the mission of fostering creative individuals and producing creativity. Accordingly, researchers and educators are attempting to identify predictors that facilitate student creativity, such as teacher behaviors (e.g., encouragement and other teacher behaviors) (Chan and Yuen 2014 ). More recently, researchers have begun investigating the role of the classroom environment (Tsai et al. 2015 ). Notably missing from the literature is a thorough examination of the creative learning environment, despite suggestions by scholars that student creativity can be nurtured by educators who focus greater effort on building a learning environment that highlights the value of creativity (Davies et al. 2013 ; Richardson and Mishra 2018 ). Therefore, a major purpose of this study is to address the connection between a creative learning environment and student creativity by identifying several important intervening mechanisms.

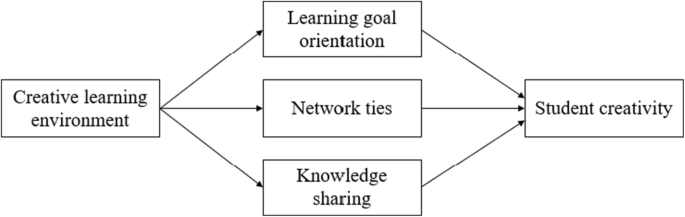

In building a model linking a creative learning environment and creativity, we further draw on the dynamic componential theory of creativity (Amabile and Pratt 2016 ), which suggests that desirable contexts can induce creativity by influencing multiple personal motivations and behaviors. This foundational theory highlights the exploration of personal motivations and social exchanges as mediators in creativity research. Thus, I propose three mediating mechanisms with high potential to help explain the linkage: learning goal orientation , network ties , and knowledge sharing . Specifically, learning goal orientation, referring to students who believe in learning, understanding, and development as ends in themselves (Lerang et al. 2019 ), illustrates students’ internal motivation in seeking knowledge to produce creative outputs (D’Lima et al. 2014 ). As the framework of achievement goal theory highlighting both the personal and contextual aspects of goals, creativity scholars have found that the learning environment in the classroom may form students’ perceived goal orientation, and the goal orientation of students may in turn generate various learning behaviors and outcomes (Peng et al. 2013 ). In line with literature on the significance of student motivation (Meece et al. 2006 ; Schuitema et al. 2014 ), scholars are calling for examining the mediating effect of learning goal orientation in linking the creative learning environment and student creativity.

As students learn in a group and/or classroom, interactions among each other may also be embedded in broader social networks; therefore, the ties among students within social networks can improve the quality of information received (Hommes et al. 2012 ). Network ties represent students’ relations with their teachers and classmates within an academic environment (Chow and Chan 2008 ), which was found not only to be composed of factors in class but also to impact students’ outcomes. Despite the attention given to the acknowledgment that encouraging personal interactions can benefit students more from diverse information exchange in generating creativity (Cheng 2011 ), knowledge on whether network ties can transmit the influence of a creative learning environment on student creativity is still limited.

Finally, scholars have acknowledged that when students are sharing their knowledge, they tend to utilize the knowledge-based resources in the classroom and after class to facilitate their creative activities (Yeh et al. 2012 ). Since creativity theoretically requires various types of knowledge and information (Amabile 2012 ), previous research has indicated that improving university students’ creativity is based on knowledge-management, which involves the process of converting knowledge and creating new knowledge (Van Den Hooff and De Ridder 2004 ), as well as the process of sharing relevant information, ideas, suggestions, and expertise with others (Bartol and Srivastava 2002 ). However, studies thus far fail to provide a clear picture to evidence whether learning contexts may stimulate students’ creativity via knowledge sharing. Taken together, we propose that learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing can mediate the relationship between student creativity and a creative learning environment. Figure 1 shows the hypothesized model.

The hypothesized model

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Creative learning environment and student creativity.

Creativity is generally conceptualized as individual’s ability to generate new ideas (e.g., Amabile 1996 ; Liu 2017 ; Tsai et al. 2015 ). For example, Amabile’s ( 2012 ) definition of creativity—i.e., the production of ideas that are both novel and useful—has been widely used in the educational research area. In the current study, we follow this line of literature, and define creativity in learning as the ability to create new robust ideas and novel ways of dealing with a learning problem, which emerge from discussion and interaction between peers (Rodriguez, Zhou, & Carrió, 2017). To cultivate student’s creativity in the context of classroom, scholars suggest to encourage students to ask more questions, to investigate the causes, effects, and consequences of their observations, and to generate more high-quality questions (Barrow, 2010). Accordingly, it is critical to understand how to effectively boost student creativity with regard to the learning context.

There is reasonable evidence from a number of studies indicating that creativity can be stimulated by contextual factors (Kozbelt et al. 2010 ). Among such factors as classroom interaction and teachers’ positive behaviors and attitudes (Beghetto and Kaufman 2014 ), an important characteristic of teachers is strong facilitation skills. That is, teachers, as supportive facilitators, can inspire students to become intellectual risk-takers and creative problem solvers. Consistently, scholars suggest that creative learning is a key element in the creative process (Chappell and Craft 2011 ); thus, students need to be provided creative learning opportunities in the classroom environment (Richardson and Mishra 2018 ). Therefore, school environments that support and actively accelerate students’ creative expression can promote students’ engagement in creative activities (Davies et al. 2013 ; Tsai et al. 2015 ).

Based on the arguments above, the present study proposes a specific learning environment—i.e., a creative learning environment—that may directly boost students’ creativity. A creative learning environment in class is characterized as valuing ideas, indicating that students are not only allowed but also encouraged to take sensible risks and make mistakes during the learning process (Mishra 2018 ); therefore, students are highly supported in reaching their creative potential (Chan and Yuen 2014 ). For example, in a review of a classroom learning environment, researchers found that when studying in a creative learning environment at school, students are likely to continue to develop their skills and professional knowledge, which significantly spurs the development of their creative responses (Davies et al. 2013 ). As a result, students have more creative achievements (Mishra 2018 ). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

The creative learning environment is positively related to student creativity.

Learning Goal Orientation as a Mediator

Goal orientation is the reason or purpose for a person’s involvement in tasks (VandeWalle et al. 2001 ). Importantly, as a key dimension of individual goal orientation, learning goal orientation has been found to be formed by desirable environments (Schweder et al. 2019 ) and to benefit individuals’ processes of producing creative outcomes (Malmberg 2008 ; VandeWalle et al. 2001 ). For example, scholars empirically illustrated that a learning environment (e.g., a classroom structure characterized as contingency-contract) facilitated students to set more learning goals (Self-Brown and Mathews 2003 ), which then increased individuals’ effort investment towards more achievements(Pintrich 2000 ; Schweder et al. 2019 ). Considering the conceptual and empirical evidence, we propose learning goal orientation as a mediator in the relationship between student creativity and a creative learning environment. Since a creative learning environment is characterized as providing support and resources (Davies et al. 2013 ), individuals are given more opportunities to become interested in and enjoy a learning activity. Thus, when learning in this situation, it is emphasized that students can extend their abilities through greater effort (Richardson and Mishra 2018 ) and can seek out opportunities to practice and improve their skills (Lerang et al. 2019 ), leading to greater achievement.

Creative outputs, theoretically, require abilities and skills to generate novel ideas and solutions (Amabile 1996 ); therefore, learning and developing new knowledge are essential to be creative in class. Consistent with this stream of reasoning, scholars have claimed that an individual’s learning goal orientation can stimulate actions to improve his or her creative competencies (Gong et al. 2009 ). That is, students who have a strong learning goal orientation act more proactively and respond positively to problems and challenges through their knowledge of learning (Chan and Yuen 2014 ). Consequently, these students may experience higher levels of internal motivation to devise creative ideas (Shin et al. 2012 ).

Taken together, we hypothesize the mediating effect of learning goal orientation in the creative learning environment-creativity relationship. Specifically, the space within a classroom that is capable of being used flexibly to promote students’ learning can facilitate the development of learning goal orientation among students, which in turn offers them resources to become creative. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Learning goal orientation mediates the relationship between a creative learning environment and student creativity.

Network Ties as a Mediator

A glance at the academic and wider educational literature reveals that social capital emphasizes personal interactions in terms of social ties (Dawson 2008 ). Scholars specify that creating a creative learning environment in the classroom can promote interaction among students because they can observe an open mindset and good communication climate (Mishra 2018 ). For instance, researchers in the area of tie strength suggest that strong ties involve higher emotional closeness, whereas weak ties are more likely to be nonredundant connections and, thus, to be associated with nonredundant information (Granovetter 1977 ; Perry-Smith 2006 ). Thus, the space within a classroom that is capable of being used flexibly to promote students’ learning can contribute to building their network ties.

Previous studies have also indicated that students’ social capital is an important asset to promote their creativity (Eid and Al-Jabri 2016 ). Specifically, when students build personal ties within their surroundings (e.g., with classmates), they are more willing to make contact with other students because of their common interests in the classroom (Liu et al. 2017 ), which eventually increases their ability not only to solve problems but also to reformulate problems and solutions creatively. Moreover, it is clear that social network ties facilitate new connections among students and teachers, in that they provide individuals with an alternative way to connect with others who share their interests or relational goals (Ellison et al. 2006 ; Parks and Floyd 1996 ). These new connections may result in an increase in achieving their goal in a creative way (Beghetto 2010 ; Soh 2017 ).

Taken together, the mediator of network ties is proposed in the relationship between creativity and a creative learning environment. Specifically, when the class is characterized as promoting learning in a creative way, students are more likely to build a strong network tie. As a result, they tend to be connecting with others (e.g., classmates, and teachers) who may not only provide useful information or new perspectives but also emotional support (Ellison et al. 2007 ), and then put more efforts into creative activities. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Network ties mediate the relationship between creative learning environment and student creativity.

Knowledge Sharing as a Mediator

Knowledge sharing is generally defined as activities through which various types of knowledge (e.g., information and skills) are exchanged and disseminated among people, units, communities, and/or organizations (Bukowitz and Williams 1999 ). Previous education literature has significantly highlighted the importance of knowledge sharing in the classroom (Eid and Al-Jabri 2016 ). Specifically, students accumulate their knowledge through integrating information, experience, and theory from their surroundings (Chang and Chuang 2011 ). That is, when students are studying in a learning environment characterized as having supportive relationships between teachers and learners, students are more likely to interact with others in the group and to share knowledge and experiences. As a result, their performance in class is significantly improved (Eid and Al-Jabri 2016 ). We therefore expect a positive effect of a creative learning environment on student knowledge sharing.

Based on the previous research findings, we further expect that knowledge sharing can stimulate student creativity in class. Specifically, the shared knowledge can improve individuals’ capabilities of forming new knowledge, refining old knowledge, as well as synthesizing more knowledge in the future (Yeh et al. 2012 ). As researchers have suggested, the more knowledge is shared, the more nonoverlapping information emerges from other students within the group (Chow and Chan 2008 ; Eid and Al-Jabri 2016 ; Richter et al. 2012 ). In this situation, students can receive the benefits of collective wisdom, which provides information contributing to their explicit knowledge and subsequently enhancing their creativity (Yeh et al. 2012 ). Therefore, knowledge sharing can leverage students’ engagement in creative activities.

Taken together, we argue that when students are learning in a conducive environment characterized as highlighting creative learning, they have more willingness to share their knowledge with their classmates; therefore, they have more opportunities to access to diverse knowledge and information, which trigger their creative ideas to solve problems. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between a creative learning environment and student creativity.

Sample and Procedure

The participants in the current research were 431 undergraduates in their third year of studies and their teachers from a university in the central region of P.R. China. Before submitting our questionnaires to the undergraduate students, one of the authors asked the dean of the university about whether creativity is encouraged in the classroom. We received the information that creativity was present throughout the courses in all projects and work carried out in School of Business, especially in the two departments—i.e., department of tourism management and department of business administration. Students in the two majors were educated to pursue creative, problem-solving and flexible capabilities that today’s employers demand. Specifically, educators have practically highlighted, and scholars have theoretically found that creativity is significantly required for students both in tourism management and business administration majors (e.g., Blau et al. 2019 ; Liu 2017 ).

Next, the teachers of undergraduate students in the two departments also sent us the confirmation that they not only paid attention to help students develop creative problem-solving skills, but also encouraged students in the class to be creative in learning. Afterwards, teachers were asked to help collect data. Specifically, questionnaires were sent to 440 undergraduate students during their classes, and they were asked to complete the survey. The participants were completely unaware of the goals and aims of the research, and they did not have any prior training in creativity. The teacher in the class announced that all the questionnaires were confidential and would be used only for research. None of the items on the scale had correct answers; the students were to answer each item according to their own perceptions. Subsequently, the teacher received all the questionnaires; and then the teacher rated each student’s creativity. Finally, the teacher sent all the questionnaires to one of the authors directly.

After deleting nine incomplete questionnaires, we received 431 validate responses from undergraduate students (98% response rate). In total, 69.7% of the students were female; 41.8% of the students majored in tourism management, and 58.2% majored in business administration.

Measurements

In order to obtain reliable information from the respondents, existing measures with established validity and reliability from previous literature were selected to operationalize all constructs in our study. In addition, all the scales were widely used in education and creativity research fields. All the variables are assessed with a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree). We used the back-translation procedure (Brislin 1986 ) to translate the English version into a Chinese version. The specific measurements of these constructs’ reliability and convergent validity can be found in Appendix Table 1 .

Creative Learning Environment

The creative learning environment was adapted from Richardson and Mishra ( 2018 ) and measured using 14 items to portray students’ perceptions of the creative learning environment in the class. An example of items is “Multiple ways of knowing and learning are encouraged in class”. The scale had a reliability of 0.91.

Learning Goal Orientation

Following previous studies (Lerang et al. 2019 ), the scale with four items adapted (Skaalvik 1997 ) was used to assess students’ learning orientation in the current study (χ 2 / df = 3.35/2; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04). An example of items is “In class I want to learn something new”. The scale had a reliability of 0.90.

Knowledge Sharing

A 3-item scale (Yeh et al. 2012 ) was used to measure knowledge sharing. “In my class I know who I can contact for specific questions,” is an example of a question from this measure. The scale had a reliability of 0.88.

Creativity-Enhancing Network Activities

Reflecting students’ creativity-enhancing network activities with their classmates, network ties were assessed using a three-item scale (Chow and Chan 2008 ). An example of items is “In general, I have a very good relationship with my classmates”. The scale had a reliability of 0.92.

Student Creativity

The teacher was asked to rate student creativity with a 4-item creativity scale (Farmer et al. 2003 ). An example of items is “This student seeks new ideas and ways to solve problems”. The scale had a reliability of 0.86.

Control Variables

Following previous studies (e.g., Peng et al. 2013 ; Schweder et al. 2019 ), we controlled for students’ age (in years) since past research has indicated that individual learning may vary across student ages. Moreover, because these participants (i.e., students) are from different research backgrounds, we controlled their major (1 = tourism management; 2 = business administration).

Analytical Strategy

We first conducted preliminary analyses to establish the factors’ discriminant validity in the current study. Furthermore, we tested our hypotheses using a PROCESS program developed by Preacher et al. ( 2007 ) in SPSS because it facilitates path analysis-based moderation analyses as well as their combination as a “conditional process model” by using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Specifically, we, in the first step, test the mediation effects through applying OLS regression analyses in the PROCESS program to generate the direct and indirect effects. In the next step, as several methodologists have recently recommended using a bootstrap approach to obtain confidence intervals (CIs), we tested the mediation hypothesis through a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 samples. Since this research aims to unfold the different mechanisms in the creative learning environment-creativity association, in the following analyses, we controlled for other mediators, testing a specific mediator to further validate the mediating effects.

Preliminary Analyses

Before testing hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine discriminate validity using AMOS 21.0. The results are shown in Appendix Table 2 . We evaluated the fit of our models based on five primary fit indices, as suggested by Hu.

Bentler (1999): the χ 2 test of model fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its respective confidence intervals, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). The results show that the hypothesized five-factor model provided a better fit to the data ( χ 2 [198] = 323.82, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04) than other alternative models (Hu and Bentler 1999 ): a three-factor model combining network ties and knowledge sharing ( χ 2 [236] = 1748.77, CFI = 0.84, TLI = 0.81, RMSEA = 0.12), a two-factor model combining learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing ( χ 2 [238] = 1931.58, CFI = 0.82, TLI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.13), and a one-factor model combining all the variables ( χ 2 [241] = 2444.94, CFI = 0.77, TLI = 0.73, RMSEA = 0.15).

Appendix Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and Cronbach’s alphas for all the variables.

Hypotheses Testing

To test the hypotheses, we employed an SPSS macro program (Hayes 2012 ) to estimate the mediation effects. Specifically, we used Model 4 in PROCESS, which generates direct and indirect effects in mediation, where total effects, direct effects and indirect effects are estimated by means of OLS regression analyses. Appendix Table 4 shows the results.

Regarding testing H1, in Model 1, the creative learning environment was positively associated with student creativity ( β = 0.79, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Regarding testing H2, H3 and H4, in Model 2, the creative learning environment was positively associated with learning goal orientation ( β = 0.45, p < 0.001) after controlling network ties and knowledge sharing. In Model 3, the creative learning environment was positively associated with network ties ( β = 0.33, p < 0.001) after controlling learning goal orientation and knowledge sharing. In Model 4, creative learning environment was positively associated with knowledge sharing ( β = 0.14, p < 0.05) after controlling learning goal orientation and network ties. Moreover, when the independent variable (i.e., creative learning environment) and the three mediators (i.e., learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing) were entered in the regression model (i.e., Model 5), the independent variable (learning goal orientation, β = 0.25, p < 0.001; network ties, β = 0.033, p < 0.001; knowledge sharing, β = 0.14, p < 0.001) and the mediators were positively related to student creativity. That is, the relationship between the creative learning environment and creativity was partially mediated by the three mediators.

To further examine the mediating effects, we conducted a bias-corrected bootstrap (10,000 resamples) analysis. The results (in Appendix Table 5 ) showed that the indirect effect of the creative learning environment on creativity through learning goal orientation was 0.11 (95% CI = 0.064, 0.163), supporting H2; through network ties was 0.11 (95% CI = 0.056, 0.170), supporting H3; and through knowledge sharing was 0.02 (95% CI = 0.001, 0.049), supporting H4.

Aiming at opening the black box of how a creative learning environment can contribute to student creativity, the current study proposes and tests a mediation model that examines the relationship between a creative learning environment and student creativity through multiple intervening mechanisms. The results show that a creative learning environment is positively related to student creativity through improving students’ learning goal orientation, knowledge sharing, and network ties concurrently.

Theoretical Implications

The main aim of the present study was to investigate how a creative learning environment can foster student creativity in class through multiple intervening mechanisms. There are several implications of this study that will enrich the current literature. First, this study fills the gap regarding the potential influence of a creative learning environment on creativity. Although previous studies have conceptually suggested that a learning environment that promotes creative activities in class boosts students’ academic outcomes (Davies et al. 2013 ; Richardson and Mishra 2018 ), there is less empirical evidence to establish the benefits for creativity. Thus, this study answers scholars’ call to “provide clear evidence of the effectiveness of creative learning environments” (Davies et al. 2013 , p.89) by theorizing about the positive influences of a creative learning environment on undergraduate students’ creativity.

Moreover, this study represents one of the first attempts to simultaneously examine distinct mechanisms from a different perspective to explain how a creative learning environment elicits student creativity. Specifically, drawing on the dynamic componential model, the findings extend the current understanding of learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing as distinct mediators. In recent years, scholars have increasingly argued that identifying multiple mechanisms can comprehensively reveal the effectiveness of contextual predictors for creativity (Amabile and Pratt 2016 ). Nevertheless, few studies have either explored the possibilities of various mediators simultaneously or focused on undergraduate students’ creativity. This study deepens our understanding of the processes involved in generating student creativity in which a creative learning environment can increase students’ learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing concurrently to further boost their creativity.

Educational Implications

According to the findings, creating a learning environment should consider creative aspects to effectively enhance student creativity in class. Specifically, teachers can encourage students to learn and think creatively (e.g., taking risks, building free and open communication channels, supporting creative ideas, and allowing more freedom and choice while students complete their assignments). Moreover, as students’ learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing are key mediators for transferring the benefits of a creative learning environment, teachers should place value on the understanding of concepts and emphasize student effort over course grades (Lerang et al. 2019 ). In doing so, teachers can build students’ learning goal orientations more in the direction of creative achievement. Regarding the development of students’ network ties, they can be provided with training programs to develop their abilities to manage individual social connections and those of others, thus enabling them to study effectively while developing collaboration skills in class. Finally, teachers can consistently highlight the importance of exchanging and sharing new knowledge, which can help students acquire novel information to enhance their learning processes and effectiveness in a creative manner.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this research. First, the cross-sectional research design cannot entirely rule out the problem of causality (e.g., student creativity may facilitate the process of building a creative learning environment in class). Thus, future research can employ more sophisticated testing to determine the direction of causality. Second, as the findings indicated the partial mediation effects, studies in the future can include other mediators (e.g., collective learning behaviors) that may comprehensively explain the effectiveness of a creative learning environment on student creativity. Finally, regarding the sample of undergraduate students in China in the present study, further research with other samples (e.g., postgraduate students) can extend the generalizability of the findings.

As providing education on creativity is a major challenge and a high priority for future course design for students, determining how to boost student creativity has been the subject of scholars’ attention. This study proposes and examines whether and how multiple mechanisms can mediate the effect of a creative learning environment on undergraduate creativity. The research findings indicate that a creative learning environment can significantly enhance students’ learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing, which in turn facilitate their creativity. The direct implication is that researchers and educators should be more concerned about building creative learning environments and helping students in their development of a learning goal orientation, network ties, and knowledge sharing.

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity and innovation in organizations. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Amabile, T. M. (2012). Componential theory of creativity. Harvard Business School, 12 (96), 1–10.

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36 , 157–183.

Article Google Scholar

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9 (1), 64–76.

Beghetto, R. A. (2010). Creativity in the classroom. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (447–463). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25 (1), 53–69.

Blau, G., Williams, W., Jarrell, S., & Nash, D. (2019). Exploring common correlates of business undergraduate satisfaction with their degree program versus expected employment. The Journal of Education for Business, 94 (1), 31–39.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Beverley Hills, CA: Sage.

Bukowitz, W. R., & Williams, R. L. (1999). The knowledge management fieldbook . Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial times/prentice hall.

Chan, S., & Yuen, M. (2014). Personal and environmental factors affecting teachers’ creativity-fostering practices in Hong Kong. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 12 , 69–77.

Chang, H. H., & Chuang, S.-S. (2011). Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management, 48 (1), 9–18.

Chappell, K., & Craft, A. (2011). Creative learning conversations: Producing living dialogic spaces. Educational Research, 53 (3), 363–385.

Cheng, V. M. (2011). Infusing creativity into eastern classrooms: Evaluations from student perspectives. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6 (1), 67–87.

Chow, W. S., & Chan, L. S. (2008). Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational knowledge sharing. Information & Management, 45 (7), 458–465.

D’Lima, G. M., Winsler, A., & Kitsantas, A. (2014). Ethnic and gender differences in first-year college students’ goal orientation, self-efficacy, and extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. The Journal of Educational Research, 107 (5), 341–356.

Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Collier, C., Digby, R., Hay, P., & Howe, A. (2013). Creative learning environments in education—A systematic literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8 , 80–91.

Dawson, S. (2008). A study of the relationship between student social networks and sense of community. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 11 (3), 224–238.

Eid, M. I., & Al-Jabri, I. M. (2016). Social networking, knowledge sharing, and student learning: The case of university students. Computers & Education, 99 , 14–27.

Ellison, N., Heino, R., & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: Self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11 (2), 415–441.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12 (4), 1143–1168.

Farmer, S. M., Tierney, P., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2003). Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Academy of Management Journal, 46 (5), 618–630.

Gong, Y., Huang, J.-C., & Farh, J.-L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (4), 765–778.

Granovetter, M. S. (1977). The strength of weak ties Social networks (pp. 347-367): Elsevier.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling . Kansas: University of Kansas.

Hommes, J., Rienties, B., de Grave, W., Bos, G., Schuwirth, L., & Scherpbier, A. (2012). Visualising the invisible: A network approach to reveal the informal social side of student learning. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17 (5), 743–757.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6 (1), 1–55.

Kozbelt, A., Beghetto, R. A., & Runco, M. A. (2010). Theories of creativity. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2 , 20–47.

Lerang, M. S., Ertesvåg, S. K., & Havik, T. (2019). Perceived classroom interaction, goal orientation and their association with social and academic learning outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63 (6), 913–934.

Liu, C. H. S. (2017). Remodelling progress in tourism and hospitality students’ creativity through social capital and transformational leadership. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 21 , 69–82.

Liu, S., Zhu, M., Yu, D. J., Rasin, A., & Young, S. D. (2017). Using real-time social media technologies to monitor levels of perceived stress and emotional state in college students: A web-based questionnaire study. JMIR Mental Health, 4 (1), e2.

Malmberg, L.-E. (2008). Student teachers' achievement goal orientations during teacher studies: Antecedents, correlates and outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 18 (5), 438–452.

Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 57 , 487–503.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mishra, B. (2018). The organizational learning inventory: An assessment guide for understanding your institution’s learning capabilities. The Learning Organization, 25 (6), 455–456.

Parks, M. R., & Floyd, K. (1996). Making friends in cyberspace. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 1 (4), JCMC144.

Peng, S.-L., Cherng, B.-L., Chen, H.-C., & Lin, Y.-Y. (2013). A model of contextual and personal motivations in creativity: How do the classroom goal structures influence creativity via self-determination motivations? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 10 , 50–67.

Perry-Smith, J. E. (2006). Social yet creative: The role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 49 (1), 85–101.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 (3), 544–555.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42 (1), 185–227.

Richardson, C., & Mishra, P. (2018). Learning environments that support student creativity: Developing the SCALE. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 27 , 45–54.

Richter, A. W., Hirst, G., Van Knippenberg, D., & Baer, M. (2012). Creative self-efficacy and individual creativity in team contexts: Cross-level interactions with team informational resources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97 (6), 1282–1290.

Schuitema, J., Peetsma, T., & van der Veen, I. (2014). Enhancing student motivation: A longitudinal intervention study based on future time perspective theory. The Journal of Educational Research, 107 (6), 467–481.

Schweder, S., Raufelder, D., Kulakow, S., & Wulff, T. (2019). How the learning context affects adolescents’ goal orientation, effort, and learning strategies. The Journal of Educational Research, 112 (5), 604–614.

Self-Brown, S. R., & Mathews, S. (2003). Effects of classroom structure on student achievement goal orientation. The Journal of Educational Research, 97 (2), 106–112.

Shin, S. J., Kim, T.-Y., Lee, J.-Y., & Bian, L. (2012). Cognitive team diversity and individual team member creativity: A cross-level interaction. Academy of Management Journal, 55 (1), 197–212.

Skaalvik, E. M. (1997). Self-enhancing and self-defeating ego orientation: Relations with task and avoidance orientation, achievement, self-perceptions, and anxiety. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (1), 71–81.

Soh, K. (2017). Fostering student creativity through teacher behaviors. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23 , 58–66.

Tsai, C.-Y., Horng, J.-S., Liu, C.-H., Hu, D.-C., & Chung, Y.-C. (2015). Awakening student creativity: Empirical evidence in a learning environment context. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 17 , 28–38.

Van den Hooff, B., & De Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8 (6), 117–130.

VandeWalle, D., Cron, W. L., & Slocum Jr., J. W. (2001). The role of goal orientation following performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (4), 629–640.

Yeh, Y.-C., Yeh, Y.-L., & Chen, Y.-H. (2012). From knowledge sharing to knowledge creation: A blended knowledge-management model for improving university students’ creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7 (3), 245–257.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number WK2160000013).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Weinan Normal University, Weinan, People’s Republic of China

School of Public Affairs, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, People’s Republic of China

Wenjing Cai

Department of Management and Organization, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wenjing Cai .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fan, M., Cai, W. How does a creative learning environment foster student creativity? An examination on multiple explanatory mechanisms. Curr Psychol 41 , 4667–4676 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00974-z

Download citation

Published : 04 August 2020

Issue Date : July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00974-z

Share this article