Informative Essay — Purpose, Structure, and Examples

What is informative writing?

Informative writing educates the reader about a certain topic. An informative essay may explain new information, describe a process, or clarify a concept. The provided information is objective, meaning the writing focuses on presentation of fact and should not contain personal opinion or bias.

Informative writing includes description, process, cause and effect, comparison, and problems and possible solutions:

Describes a person, place, thing, or event using descriptive language that appeals to readers’ senses

Explains the process to do something or how something was created

Discusses the relationship between two things, determining how one ( cause ) leads to the other ( effect ); the effect needs to be based on fact and not an assumption

Identifies the similarities and differences between two things; does not indicate that one is better than the other

Details a problem and presents various possible solutions ; the writer does not suggest one solution is more effective than the others

Purpose of informative writing

The purpose of an informative essay depends upon the writer’s motivation, but may be to share new information, describe a process, clarify a concept, explain why or how, or detail a topic’s intricacies.

Informative essays may introduce readers to new information .

Summarizing a scientific/technological study

Outlining the various aspects of a religion

Providing information on a historical period

Describe a process or give step-by-step details of a procedure.

How to write an informational essay

How to construct an argument

How to apply for a job

Clarify a concept and offer details about complex ideas.

Explain why or how something works the way that it does.

Describe how the stock market impacts the economy

Illustrate why there are high and low tides

Detail how the heart functions

Offer information on the smaller aspects or intricacies of a larger topic.

Identify the importance of the individual bones in the body

Outlining the Dust Bowl in the context of the Great Depression

Explaining how bees impact the environment

How to write an informative essay

Regardless of the type of information, the informative essay structure typically consists of an introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction

Background information

Explanation of evidence

Restated thesis

Review of main ideas

Closing statement

Informative essay introduction

When composing the introductory paragraph(s) of an informative paper, include a hook, introduce the topic, provide background information, and develop a good thesis statement.

If the hook or introduction creates interest in the first paragraph, it will draw the readers’ attention and make them more receptive to the essay writer's ideas. Some of the most common techniques to accomplish this include the following:

Emphasize the topic’s importance by explaining the current interest in the topic or by indicating that the subject is influential.

Use pertinent statistics to give the paper an air of authority.

A surprising statement can be shocking; sometimes it is disgusting; sometimes it is joyful; sometimes it is surprising because of who said it.

An interesting incident or anecdote can act as a teaser to lure the reader into the remainder of the essay. Be sure that the device is appropriate for the informative essay topic and focus on what is to follow.

Directly introduce the topic of the essay.

Provide the reader with the background information necessary to understand the topic. Don’t repeat this information in the body of the essay; it should help the reader understand what follows.

Identify the overall purpose of the essay with the thesis (purpose statement). Writers can also include their support directly in the thesis, which outlines the structure of the essay for the reader.

Informative essay body paragraphs

Each body paragraph should contain a topic sentence, evidence, explanation of evidence, and a transition sentence.

A good topic sentence should identify what information the reader should expect in the paragraph and how it connects to the main purpose identified in the thesis.

Provide evidence that details the main point of the paragraph. This includes paraphrasing, summarizing, and directly quoting facts, statistics, and statements.

Explain how the evidence connects to the main purpose of the essay.

Place transitions at the end of each body paragraph, except the last. There is no need to transition from the last support to the conclusion. A transition should accomplish three goals:

Tell the reader where you were (current support)

Tell the reader where you are going (next support)

Relate the paper’s purpose

Informative essay conclusion

Incorporate a rephrased thesis, summary, and closing statement into the conclusion of an informative essay.

Rephrase the purpose of the essay. Do not just repeat the purpose statement from the thesis.

Summarize the main idea found in each body paragraph by rephrasing each topic sentence.

End with a clincher or closing statement that helps readers answer the question “so what?” What should the reader take away from the information provided in the essay? Why should they care about the topic?

Informative essay example

The following example illustrates a good informative essay format:

How to Write an Informative Essay: Everything You Need to Know

Did you know that informative essays aren't just for school? They're also used in jobs like journalism, marketing, and PR to explain complex ideas and promote things. This shows how useful they are outside of the classroom.

So, if you're planning to write one, that's a great choice! It's interesting but can be tough. To do it well, you need to plan, research, and organize carefully. Keep your tone balanced, give clear info, and add your own thoughts to stand out.

In this guide, our essay writer will give you tips on starting and organizing your essay effectively. At the end, you'll also find interesting essay samples. So, let's jump right into it.

What is an Informative Essay

To give a good informative essay definition, imagine them as windows to new knowledge. Their main job is to teach others about a particular topic. Whether it's for a school project or something you stumble upon online, these essays are packed with interesting facts and insights.

Here's a simple breakdown from our admission essay writing service of what makes an informative essay tick:

- Keeping It Real: These essays are all about the facts. No opinions allowed. We want to keep things fair and honest.

- Topics Galore: You can write about anything you find interesting, from science and history to things about different cultures.

- Where You Find Them: Informative essays can pop up anywhere, from your classroom assignments to the pages of magazines or even online articles.

- Research: Like a good detective, informative essays rely on solid evidence. That means digging into trustworthy sources to gather reliable information.

- Stay Neutral: To keep things fair, informative essays don't take sides. They present the facts and let readers draw their own conclusions.

- Structure: These essays have a clear roadmap. They start with an introduction to set the stage, then present the main points with evidence, and wrap up with a summary to tie it all together.

- Write for Your Audience: Keep your writing simple and easy to understand. Think about who will be reading it.

- Give Just Enough Detail: Don't overload people with info. Find the right balance so it's interesting but not overwhelming.

Ready to Ignite Minds with Your Informative Essay?

Our qualified writers are here to craft a masterpiece tailored to your needs worthy of an A+

Reasons to Write an Informative Essay

Writing informative essays, whether following the IEEE format or another style, is a great way to teach and share ideas with others. Here's why it's worth giving it a try:

.webp)

- Make Complex Ideas Easy : Informative essays simplify complicated topics so everyone can understand them. They break down big ideas into simple parts, helping more people learn and share knowledge.

- Encourage Thinking : When you read these essays, you're encouraged to think for yourself. They give you facts and evidence so you can form your own opinions about different topics. This helps you become better at understanding the world around you.

- Inspire Doing : They can motivate people to take action and make positive changes by raising awareness about important issues like the environment, fairness, or health. By reading these essays, people might be inspired to do something to help.

- Leave a Mark : When you write informative essays, you're leaving a legacy of knowledge for future generations. Your ideas can be read and learned from long after you're gone, helping others understand the world better.

How to Start an Informative Essay

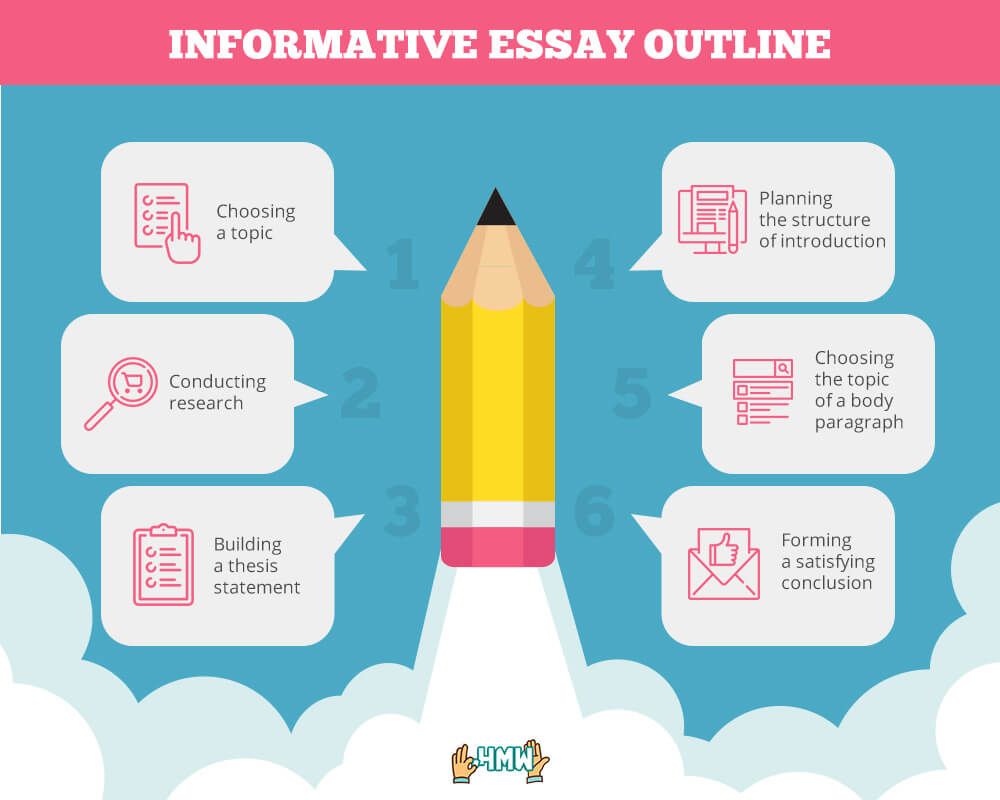

If you're still doubting how to start with an informative essay outline, no worries! Here's a step-by-step guide to help you tackle this task like a pro. Alternatively, you can simply order essay and have it done by experts.

- Choose an Exciting Topic : Pick something that really grabs your attention. Writing about what you're genuinely interested in makes the whole process way more fun. Plus, it's easier to write confidently about things you know a bit about.

- Dig into Research : Spend some quality time digging up info from reliable sources. Take good notes, so you have all the facts you need to back up your essay. The better your research, the stronger your essay will be.

- Set Your Essay's Goal : Decide what you want your essay to do. Are you explaining something, analyzing a problem, or comparing ideas? Knowing your goal helps you focus your writing.

- Sketch Out Your Essay : Make a simple plan for your essay. Start with an intro that grabs attention and states your main idea. Then, map out your main points for the body paragraphs and plan a strong finish for your conclusion.

- Kick Off with an Awesome Introduction : Start with a killer opening line to hook your readers. Give a bit of background on your topic and clearly state your main idea.

- Flesh Out Your Body Paragraphs : In each paragraph, cover one key point backed up with evidence from your research. Keep it clear and simple, and don't forget to cite your sources.

- Wrap Up Strong : Sum up your main points in your conclusion and restate your main idea in a memorable way. Leave your readers with something to think about related to your topic.

Informative Essay Outline

Many students don't realize how helpful outlining can be for writing an informative essay. Spending a bit of time on it can actually save you loads of time later on when you're writing. To give you a head start, here's a simple format from our term paper writing services :

I. Introduction

- Start with something catchy to grab attention

- Give a little background info on your topic

- State your main idea clearly in your thesis statement

II. Body Paragraphs

A. Talk about your first main idea

- Share evidence or facts that support this idea

- Explain what the evidence means

- Transition smoothly to the next point

B. Move on to your second main idea

- Provide evidence or facts for this point

- Explain why this evidence matters

- Transition to the next paragraph

C. Address your third main idea

- Offer supporting evidence or facts

- Explain the significance of this evidence

- Transition to the next part

III. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement to remind readers of your main point

- Summarize the key points you've covered in the body paragraphs

- Leave readers with some final thoughts or reflections to ponder

IV. Optional: Extra Sections

- Consider addressing counterarguments and explaining why they're not valid (if needed)

- Offer suggestions for further research or additional reading

- Share personal anecdotes or examples to make your essay more relatable (if it fits)

Informative Essay Structure

Now that you've got a plan and know how to start an essay let's talk about how to organize it in more detail.

Introduction :

In your informative essay introduction, your aim is to grab the reader's interest and provide a bit of background on your topic. Start with something attention-grabbing, like a surprising fact or a thought-provoking question. Then, give a quick overview of what you'll be talking about in your essay with a clear thesis statement that tells the reader what your main points will be.

Body Paragraphs:

The body paragraphs of an informative essay should dive into the main ideas of your topic. Aim for at least three main points and back them up with evidence from reliable sources. Remember the 'C-E-E' formula: Claim, Evidence, Explanation. Start each paragraph with a clear point, then provide evidence to support it, and finally, explain why it's important. Mastering how to write an informative essay also requires smooth transitions from one section to the next, so don't forget to use transition words.

Conclusion :

You may already guess how to write a conclusion for an informative essay, as it's quite similar to other writing types. Wrap up by summarizing the main points you've made. Restate your thesis to remind the reader what your essay was all about. Then, leave them with some final thoughts or reflections to think about. Maybe suggest why your topic is important or what people can learn from it.

Informative Essay Examples

Essay examples show how theoretical ideas can be applied effectively and engagingly. So, let's check them out for good structure, organization, and presentation techniques.

Additionally, you can also explore essay writing apps that offer convenience and flexibility, allowing you to work on assignments wherever you are.

7 Steps for Writing an Informative Essay

Before you leave, here are 7 simple yet crucial steps for writing an informative essay. Make sure to incorporate them into your writing process:

.webp)

- Choose Your Topic: If you're given the freedom to choose your topic, opt for something you're passionate about and can explain effectively in about five paragraphs. Begin with a broad subject area and gradually narrow it down to a specific topic. Consider conducting preliminary research to ensure there's enough information available to support your essay.

- Do Your Research: Dive deep into your chosen topic and gather information from reliable sources. Ensure that the sources you use are credible and can be referenced in your essay. This step is crucial for building a solid foundation of knowledge on your topic.

- Create an Outline: Once you've collected your research, organize your thoughts by creating an outline. Think of it as a roadmap for your essay, briefly summarizing what each paragraph will cover. This step helps maintain coherence and ensures that you cover all essential points in your essay.

- Start Writing: With your outline in hand, begin drafting your essay. Don't strive for perfection on the first attempt; instead, focus on getting your ideas down on paper. Maintain an objective and informative tone, avoiding overly complex language or unnecessary embellishments.

- Revise Your Draft: After completing the initial draft, take a break before revisiting your work. Read through your essay carefully, assessing how well your arguments are supported by evidence and ensuring a smooth flow of ideas. Rewrite any sections that require improvement to strengthen your essay's overall coherence and clarity.

- Proofread: Once you've revised your essay, thoroughly proofread it to catch any spelling or grammar errors. Additionally, verify the accuracy of the facts and information presented in your essay. A polished and error-free essay reflects positively on your attention to detail and credibility as a writer.

- Cite Your Sources: Finally, include a citations page to acknowledge the sources you've referenced in your essay. Follow the formatting guidelines of the chosen citation style, whether it's MLA, APA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and proper credit to the original authors. This step is essential for maintaining academic integrity and avoiding plagiarism accusations.

Final Remarks

Fantastic! Now that you know how to write an informative essay and absorbed the essentials, let's recap the key points:

- You've learned the basics of informative essay writing.

- Ready to choose an interesting topic that connects with your audience.

- You've understood how to organize your essay clearly, with each paragraph serving a purpose.

- You have step-by-step guidance for writing engagingly.

- You've gained valuable tips to improve your writing skills and make your essay stand out.

By applying these insights, you're set to write an engaging essay that informs and inspires your readers!

Want to Unleash the Brilliance of Your Ideas?

Claim your expertly crafted informative essay today and command attention with your brilliant insights!

Related Articles

.webp)

Writing an Informative Essay

Informative essays engage readers with new, interesting, and often surprising facts and details about a subject. Informative essays are educational; readers expect to learn something new from them. In fact, much of the reading and writing done in college and the workplace is informative. From textbooks to reports to tutorials like this one, informative writing imparts important and useful information about a topic.

This tutorial refers to the sample informative outline and final essay written by fictional student Paige Turner.

Reasons to Write Informatively

Your purpose for writing and the audience for whom you are writing will impact the depth and breadth of information you provide, but all informative writing aims to present a subject without opinions or bias. Some common reasons to write informatively are to

- report findings that an audience would find interesting,

- present facts that an audience would find useful, and

- communicate information about a person, place, event, issue, or change that would improve an audience’s understanding.

Characteristics of Informative Essays

Informative essays present factual information and do not attempt to sway readers’ opinions about it. Other types of academic and workplace writing do try to influence readers’ opinions:

- Expository essays aim to expose a truth about an issue in order to influence how readers view the issue.

- Persuasive essays aim to influence readers’ opinions, so they will adopt a particular position or take a certain course of action.

Expository and persuasive essays make “arguments.” The only argument an informative essay makes is that something exists, did exist, is happening, or has happened, and the point of the essay is not to convince readers of this but to tell them about it.

- Informative essays seek to enlighten and educate readers, so they can make their own educated opinions and decisions about what to think and how to act.

Strategies for Writing Informatively

Informative essays provide useful information such as facts, examples, and evidence from research in order to help readers understand a topic or see it more clearly. While informative writing does not aim to appeal emotionally to readers in order to change their opinions or behaviors, informative writing should still be engaging to read. Factual information is not necessarily dry or boring. Sometimes facts can be more alarming than fiction!

Writers use various strategies to engage and educate readers. Some strategies include

- introducing the topic with an alarming fact or arresting image;

- asserting what is true or so about the subject in a clear thesis statement;

- organizing the paragraphs logically by grouping related information;

- unifying each paragraph with a topic sentence and controlling idea;

- developing cohesive paragraphs with transition sentences;

- using precise language and terminology appropriate for the topic, purpose, and audience; and

- concluding with a final idea or example that captures the essay’s purpose and leaves a lasting impression.

Five Steps for Getting Started

1. Brainstorm and choose a topic.

- Sample topic : The opioid epidemic in the United States.

- The opiod epidemic or even opiod addiction would would be considered too broad for a single essay, so the next steps aim to narrow this topic down.

2. Next, write a question about the topic that you would like to answer through research.

- Sample question : What major events caused the opioid crisis in the United States?

- This question aims to narrow the topic down to causes of the epidemic in the US.

3. Now go to the Purdue Global Library to find the answers to your research question.

As you begin reading and collecting sources, write down the themes that emerge as common answers. Later, in step four, use the most common answers (or the ones you are most interested in writing and discussing) to construct a thesis statement.

- Sample answers: aggressive marketing, loopholes in prescription drug provider programs, and economic downturn.

4. Next, provide purpose to your paper by creating a thesis statement.

The thesis attempts to frame your research question. The sample thesis below incorporates three of the more common answers for the research question from step two: What caused the opioid crisis in the United States?

- Thesis Statement : Aggressive marketing, loopholes in prescription drug provider programs, and economic downturn contributed to the current opioid crisis in the United States.

- Writing Tip : For additional help with thesis statements, please visit our Writing a Thesis Statement article. For help with writing in 3rd person, see our article on Formal Vs. Informal Writing .

5. Now follow each numbered step in the “Suggested Outline Format and Sample” below.

Sample answers have been provided for “I. Introduction” and “II. First Cause.” A complete sample outline can be seen here. A complete sample informative essay can be seen here.

Suggested Outline Format and Sample

I. INTRODUCTION

A. First provide a topic sentence that introduces the main topic: Sample topic sentence : There is a current prescription pain medication addiction and abuse epidemic possibly caused by an excessive over prescription of these medications.

B. Now provide a couple sentences with evidence to support the main topic: Sample sentence one with evidence to support the main topic : According to Dr. Nora Volkow, Director of National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), in testimony before the 115th Congress, “In 2016, over 11 million Americans misused prescription opioids … and 2.1 million had an opioid use disorder due to prescription opioids” (Federal Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis, 2017, p. 2).

C. Sample sentence two with evidence to support the main topic : Volkow indicated “more than 300,000 Americans have died of an opioid overdose” since 2013 (Federal Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis, 2017, p.2).

D. Sample sentence three with evidence to support the main topic : According to Perez-Pena (2017), the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported more than 25,000 people in the United States died in 2015 from overdosing on opioids Fentanyl, Oxycodone, and Hydrocodone.

E. Toward the end of the introduction, include your thesis statement written in the 3rd-person point-of-view: Sample thesis statement : Potential solutions to the growing opioid epidemic may be illuminated by examining how opioid addiction is triggered through aggressive pharmaceutical marketing, how opioid addiction manifests among prescribed patients, and how economic downturns play a role in the increase of opioid addiction.

F. Write down the library sources you can use in this introductory paragraph to help support the main topic.

- Federal Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis, 2017

- Perez-Pena, 2017

- Writing Tip : For more help writing an introduction, please refer to this article on introductions and conclusions .

II. FIRST CAUSE

A. First provide a topic sentence that introduces the first cause of the opioid epidemic: Sample topic sentence that introduces the first cause : One issue that helped contribute to the opioid epidemic is aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical manufacturers.

B. Now provide sentences with evidence to support the first cause: Sample sentence one with evidence that supports the first cause : Perez-Pena (2017) concluded that while the healthcare industry was attempting to effectively and efficiently treat patients with chronic pain, pharmaceutical companies were providing funding to prominent doctors, medical societies, and patient advocacy groups in order to win support for a particular drug’s adoption and usage.

C. Sample sentence two with evidence to support the first cause : In fact, pharmaceutical companies continue to spend millions on promotional activities and materials that deny or trivialize any risks of opioid use while at the same time overstating each drug’s benefit (Perez-Pina, 2017).

D. Next, add more information or provide concluding or transitional sentences that foreshadows the upcoming second cause: Sample concluding and transitional sentence that foreshadow the second cause : Although aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical companies played a large role in opioid addiction, patients are to blame too, as many take advantage of holes in the healthcare provider system in order to remedy their addiction.

E. Write down the library sources you can use in this body paragraph to help support the first cause:

- Writing Tip : For more assistance working with sources, please visit the Using Sources page here.

III. SECOND CAUSE

A. First provide a topic sentence that introduces the second cause.

B. Now provide sentences with evidence to support the second cause.

C. Next, add more information or provide concluding or transitional sentences that foreshadows the upcoming third cause.

D. Write down the library sources you can use in this body paragraph to help support the second cause:

- Writing Tip : Listen to Writing Powerful Sentences for information and features of effective writing.

IV. THIRD CAUSE

A. First provide a topic sentence that introduces the third cause.

B. Now provide sentences with evidence to support the third cause.

C. Next, add more information or provide a concluding sentence or two.

D. Write down the library sources you can use in this body paragraph to help support the third cause:

V. CONCLUSION: Summary of key points and evidence discussed.

- Writing Tip : For more help writing a conclusion, refer to this podcast on endings .

- Writing Tip : Have a question? Leave a comment below or Purdue Global students, click here to access the Purdue Global Writing Center tutoring platform and available staff.

- Writing Tip : Ready to have someone look at your paper? Purdue Global students, click here to submit your assignment for feedback through our video paper review service.

See a Sample Informative Essay Outline here .

See a sample informative essay here., share this:.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

2 Responses

- Pingbacks 0

dang bro i got an A

Having faith with all this mentioned, that i will pass my english class at a college. Thank you for posting.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

How to Write an Informative Essay?

09 May, 2020

15 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

The bad news is that if you're anything like the majority of students, you're overwhelmed with all kinds of essays your teachers ask you to create. It feels as if they multiply day on day. However, the good news is that here, at HandMade Writing blog, you can find all the answers on how to craft a decent informative essay in no time. So, without further ado, let's dive into the essence of the issue together!

What is an Informative Essay?

An informative essay is a piece of writing that seeks to inform or explain a subject or topic to educate the reader. When writing an informative essay consider the audience and correspond to their level. Do not over-explain to experts where knowledge can be assumed or under-explain to novices that lack basic understating.

There are in four main categories:

- To define a term

- To compare and contrast a subject

- To analyze data

- To provide a how-to guide on a subject

An informative paper should be written in an objective tone and avoid the use of the first person.

You may order an informative essay written from scratch at our professional essay writing service – our essay writers are available 24/7.

What is the Purpose of an Informative Essay?

The purpose of an informative essay is to educate the reader by giving them in-depth information and a clear explanation of a subject. Informative writing should bombard the reader with information and facts that surround an issue. If your reader comes away feeling educated and full of facts about a subject than you have succeeded.

Examples of informative writing are pamphlets, leaflets, brochures, and textbooks. Primarily texts that are used to inform in a neutral manner.

What is the Difference Between an Informative Essay and Expository Essay?

An expository essay and an informative essay are incredibly similar and often confused. A lot of writers class them as the same type of essay. The difference between them is often hazy and contradictory depending on the author’s definition.

In both essays, your purpose is to explain and educate. An expository essay is here to define a single side of an argument or the issue. It’s the first step to writing an argumentative essay through taking the argument on the next level. Informative essays are less complicated. They are just about the information. Such essays generally require less research on a topic, but it all depends on the assignment level and subject. The difference between the two essay types is so subtle that they are almost interchangeable.

How to Plan an Informative Essay Outline

Your plan for an informative essay outline should include:

- Choosing a topic

- Conducting research

- Building a thesis statement

- Planning the structure of introduction

- Choosing the topic of a body paragraph

- Forming a satisfying conclusion

By following the list above, you will have a great outline for your informational writing.

Related Post: How to write an Essay outline

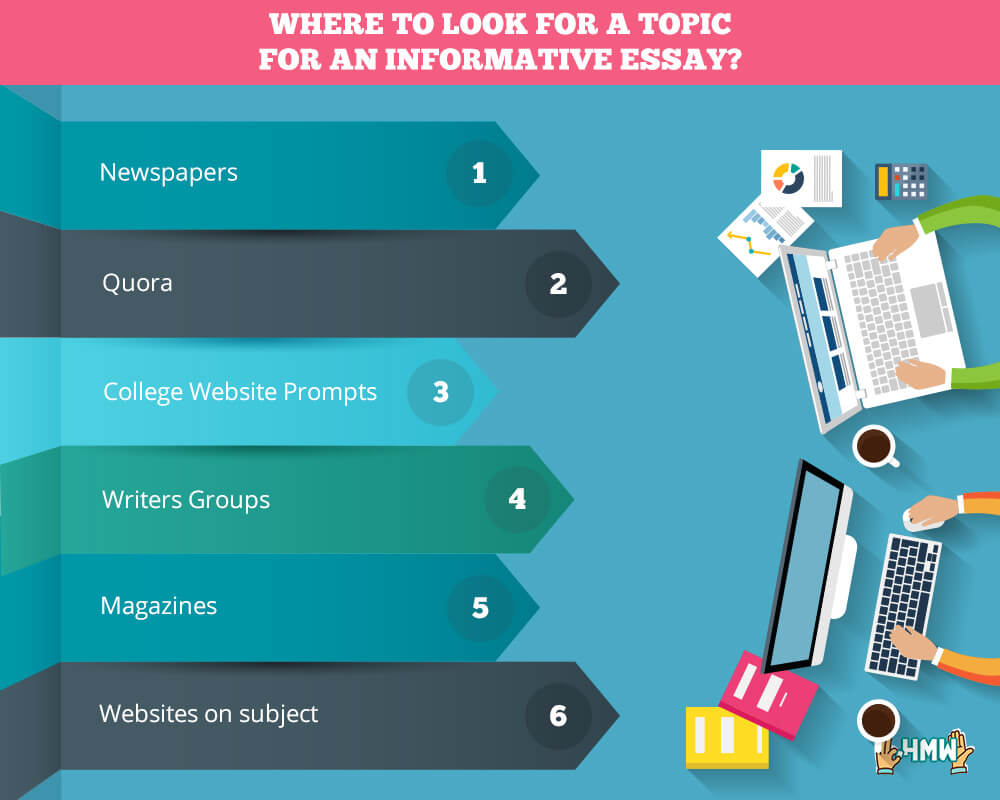

How to Choose an Informative Essay Topic

One of the most difficult tasks when writing is coming up with a topic. Here is some general advice when you are choosing a topic for your essay:

- Choose a topic that you are interested in. Your interest in writing on the subject will make the essay more engaging.

- Choose a theme that you know a little about. This way you will be able to find sources and fact easier.

- Choose a topic that can explain something new or in a different way.

- Choose a topic that you can support with facts, statistics, and

- Choose a topic that is relevant to the subject.

- Remember the four types of categories information essays cover.

Inspiration and Research for Your Ultimate Topic

Your perfect informative essay title can come from numerous sources. Here is where you can potentially seek for relevant topics:

Not only will they inspire you, but they will also provide with some of the research you need.

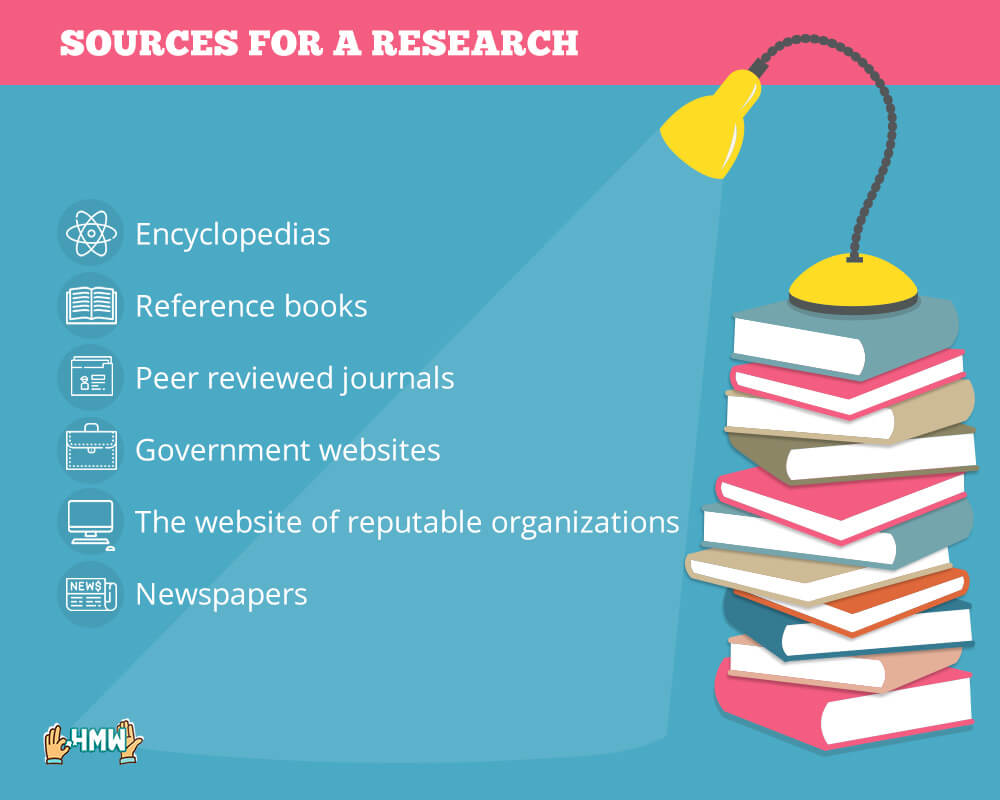

Researching an Informative Essay

The best sources should be objective. Some excellent sources for an informative essay include:

Always remember to check if the source of information will have a bias. For example, a newspaper journalist may have a political leaning, and their article might reflect that. A charities site for motor neuron disease may also come as biased. Analyze the source for the writer’s agenda.

Informational research should answer the five W’s (who, what, where, why and how), and these will form the majority of your essay’s plan. So, if I were writing about the different types of pollution I’d research what kinds of pollution there are, who and how they affect, why they happen, and where they are most likely to occur.

Collating and organizing this information will form your thesis statement and paragraph layout.

Still struggling to find a topic for your informational writing? Then, here are some ideas to that might inspire you.

Examples of Informative Essay Topics for College Students

- How to avoid stress

- What ecological problems are we faced with today?

- What are the effects of obesity?

- What is cyberbullying?

- How has the internet changed the world?

- How to adjust to college life

- Where to find the best part-time jobs

- How to get along with your room-mate

- Guidance on how to write a college application

- How caffeine affects studying

Examples of Informative Essay Topics for High School

- How to start your own vegetable garden

- The reason for and effects of childhood obesity

- Outline the consequences of texting and driving

- How to make your favorite food

- What is climate change? And what are its effects?

- The different types of pollution

- The history of the Titanic.

- An essay on the Great Depression

- The life and times of Ernst Hemmingway

- How to have a great vacation

Related Posts: Argumentative essay topics | Research paper topics

Informative Essay Example

When you have finished planning and research, you have to start writing. But, how do you start an informative essay? The simple answer is to just go with it. Do not get overly critical. Just pour out all the information you have. You can shape it up later.

Important points to consider are: never use first person pronouns and keep the topic objective not subjective . Remember, your purpose is to educate the reader in the most thorough way possible by explaining a topic with statistics and facts.

As usual, the essay should include an introduction, main body, and conclusion. All information should be presented in a clear and easy to understand manner. The flow of information should be signposted. We will delve into these areas in more detail now.

Related Post: How to Write a Narrative essay

How to Write an Introduction for an Informative Essay?

An introductory paragraph of an informative essay should comprise of the following things:

A Hook to Ensnare the Reader

An introductory paragraph for informative writing should start with a hook. A hook needs to be in the first sentence and something that will ‘wow’ the reader and impel them to read on. Alarming statistics on the subject/topic make up great hooks for informative essays. For example, if you were writing an essay on cyber-bullying, citing the number of children who have considered suicide due to cyberbullying could be a powerful opening message.

A Thesis Statements for Direction

All introductions should include a thesis statement. The best practice is to place it at the end of the introductory paragraph to summarize your argument. However, you do not want to form an argument or state a position. It is best to use the thesis statement to clarify what subject you are discussing.

Related Post: What is a thesis statement

It may also be better to place the statement after the hook, as it will clarify the issue that you are discussing.

For example, ‘Research conducted by Bob the Scientist indicates that the majority of issues caused by cyberbullying can be overcome through the informative literature on the subject to educate bullies about the consequences of their actions.’

How to Write the Body of an Informative Essay

When writing the body of an informative paper, it is best to break the paragraph down into four distinct steps.

The Claim or Statement

The claim or statement is a single, simple sentence that introduces the main topic of the paragraph. It can be narrow or broad depending on the level and depth of the essay. Think of this as the ‘what’ aspect. For example, the claim for a high-school informative paper would be broader than a claim written at the university level. This is the first step to signposting your essay. It provides a logical and easy way to follow a discussion.

The Supporting Evidence

After making a claim you want to back it up with supporting evidence. Supporting evidence could be findings from a survey, the results of an experiment, documented casual effects or a quote. Anything that lends support to the claim or statement in the first sentence would work. This is the ‘why’ aspect of your research. By using supporting evidence like this, you are defining why the statement is essential to the topic.

Explanation

After you state the supporting evidence, you want to explain ‘how’ this finding is important to the subject at hand. That usually unpacks the supporting evidence and makes it easier for the reader to understand. So, an explanation is to explain how this claim and the supporting research affects your thesis statement.

Concluding Sentence

You should always finish a body paragraph with a concluding sentence that ties up the paragraph nicely and prompts the reader on to the next stage. This is a signpost that the topic and the paragraph are wrapped up.

How to Write the Conclusion of an Informative Essay

Writing a conclusion to an informative paper can be hard as there is no argument to conclude – there is only information to summarize. A good conclusion for these types of essays should support the information provided on the subject. It should also explain why these topics are important.

Here are some Tips on writing informative essay conclusions:

Rephrase Your Thesis Statement

It is vital that you rephrase the thesis and not copy it word for word. That will allow you restate the theme or key point of your essay in a new way. You will simultaneously tie your conclusion back to the introduction of your essay. Echoing your introduction will bring the essay full circle.

Read Through Your Body Paragraphs

Read through the body paragraphs of your essay and ask if a brief overview of the main points of the essay would form a good conclusion for the essay. Generally, it is best to restate the main points of the essay in a conclusion using different words.

Finish the Conclusion With a Clincher

A clincher gives your concluding paragraph a powerful finish. It is a sentence that leaves the reader thinking about your essay long after they have put it down.

Some excellent examples of clinchers are:

- A statement of truth

- A thought-provoking quote relevant to the subject and thesis statement

- A lingering question that none of the research has answered or puts the research into a new light

- Whether it provides an answer to a common question

- Challenge your reader with a quote from an expert that forces them to think about or change their own behavior

- Something that shifts the focus onto the future and the long-time implications of your research

Context and Significance of the Information

A conclusion should always try to frame why the topic was important, and in what context it was important. By doing this your research matters.

Remember: A concluding paragraph should never include new information.

Informative Essay Sample

Be sure to check the sample essay, completed by our writers. Use it as an example to write your own informative paper. Link: Tesla motors

Tips for Writing an Excellent Informative Essay

Here are a few tips for writing an informative paper

- When writing the main body paragraph, concentrate on explaining information only once. Avoid repeating the same information in the next section.

- Focus on the subject. Make sure all the information that you include is relevant to the topic you are describing. Do not include information that “goes off.”

- Write in a logical way that is signposted. Writing like this will make an essay flow and mean it is easier to understand.

- Always revise the essay at least three times. This way, you will find where to expand ideas in the paragraph, where to trim back ideas until everything has the right balance.

- Be familiar with the academic reference style you are writing in

- Write to your audience. Make sure you know who you are writing it for.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Format an Essay

Last Updated: August 26, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Carrie Adkins, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Aly Rusciano . Carrie Adkins is the cofounder of NursingClio, an open access, peer-reviewed, collaborative blog that connects historical scholarship to current issues in gender and medicine. She completed her PhD in American History at the University of Oregon in 2013. While completing her PhD, she earned numerous competitive research grants, teaching fellowships, and writing awards. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 85,290 times.

You’re opening your laptop to write an essay, knowing exactly what you want to write, but then it hits you—you don’t know how to format it! Using the correct format when writing an essay can help your paper look polished and professional while earning you full credit. There are 3 common essay formats—MLA, APA, and Chicago Style—and we’ll teach you the basics of properly formatting each in this article. So, before you shut your laptop in frustration, take a deep breath and keep reading because soon you’ll be formatting like a pro.

Setting Up Your Document

- If you can’t find information on the style guide you should be following, talk to your instructor after class to discuss the assignment or send them a quick email with your questions.

- If your instructor lets you pick the format of your essay, opt for the style that matches your course or degree best: MLA is best for English and humanities; APA is typically for education, psychology, and sciences; Chicago Style is common for business, history, and fine arts.

- Most word processors default to 1 inch (2.5 cm) margins.

- Do not change the font size, style, or color throughout your essay.

- Change the spacing on Google Docs by clicking on Format , and then selecting “Line spacing.”

- Click on Layout in Microsoft Word, and then click the arrow at the bottom left of the “paragraph” section.

- Using the page number function will create consecutive numbering.

- When using Chicago Style, don’t include a page number on your title page. The first page after the title page should be numbered starting at 2. [4] X Research source

- In APA format, a running heading may be required in the left-hand header. This is a maximum of 50 characters that’s the full or abbreviated version of your essay’s title. [5] X Research source

- For APA formatting, place the title in bold at the center of the page 3 to 4 lines down from the top. Insert one double-spaced line under the title and type your name. Under your name, in separate centered lines, type out the name of your school, course, instructor, and assignment due date. [6] X Research source

- For Chicago Style, set your cursor ⅓ of the way down the page, then type your title. In the very center of your page, put your name. Move your cursor ⅔ down the page, then write your course number, followed by your instructor’s name and paper due date on separate, double-spaced lines. [7] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Double-space the heading like the rest of your paper.

Writing the Essay Body

- Use standard capitalization rules for your title.

- Do not underline, italicize, or put quotation marks around your title, unless you include other titles of referred texts.

- A good hook might include a quote, statistic, or rhetorical question.

- For example, you might write, “Every day in the United States, accidents caused by distracted drivers kill 9 people and injure more than 1,000 others.”

- "Action must be taken to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving, including enacting laws against texting while driving, educating the public about the risks, and giving strong punishments to offenders."

- "Although passing and enforcing new laws can be challenging, the best way to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving is to enact a law against texting, educate the public about the new law, and levy strong penalties."

- Use transitions between paragraphs so your paper flows well. For example, say, “In addition to,” “Similarly,” or “On the other hand.” [12] X Research source

- A statement of impact might be, "Every day that distracted driving goes unaddressed, another 9 families must plan a funeral."

- A call to action might read, “Fewer distracted driving accidents are possible, but only if every driver keeps their focus on the road.”

Using References

- In MLA format, citations should include the author’s last name and the page number where you found the information. If the author's name appears in the sentence, use just the page number. [14] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For APA format, include the author’s last name and the publication year. If the author’s name appears in the sentence, use just the year. [15] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- If you don’t use parenthetical or internal citations, your instructor may accuse you of plagiarizing.

- At the bottom of the page, include the source’s information from your bibliography page next to the footnote number. [16] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Each footnote should be numbered consecutively.

- If you’re using MLA format , this page will be titled “Works Cited.”

- In APA and Chicago Style, title the page “References.”

- If you have more than one work from the same author, list alphabetically following the title name for MLA and by earliest to latest publication year for APA and Chicago Style.

- Double-space the references page like the rest of your paper.

- Use a hanging indent of 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) if your citations are longer than one line. Press Tab to indent any lines after the first. [17] X Research source

- Citations should include (when applicable) the author(s)’s name(s), title of the work, publication date and/or year, and page numbers.

- Sites like Grammarly , EasyBib , and MyBib can help generate citations if you get stuck.

Formatting Resources

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/392149/WE_Formatting-your-essay.pdf

- ↑ https://content.nroc.org/DevelopmentalEnglish/unit10/Foundations/formatting-a-college-essay-mla-style.html

- ↑ https://camosun.libguides.com/Chicago-17thEd/titlePage

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/page-header

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/title-page

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html

- ↑ https://www.uvu.edu/writingcenter/docs/handouts/writing_process/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://www.deanza.edu/faculty/cruzmayra/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://library.menloschool.org/chicago

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maansi Richard

May 8, 2019

Did this article help you?

Jan 7, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Information Literacy

11 A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy

By emily metcalf.

Introduction

Welcome to “A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy,” a step-by-step guide to understanding information literacy concepts and practices.

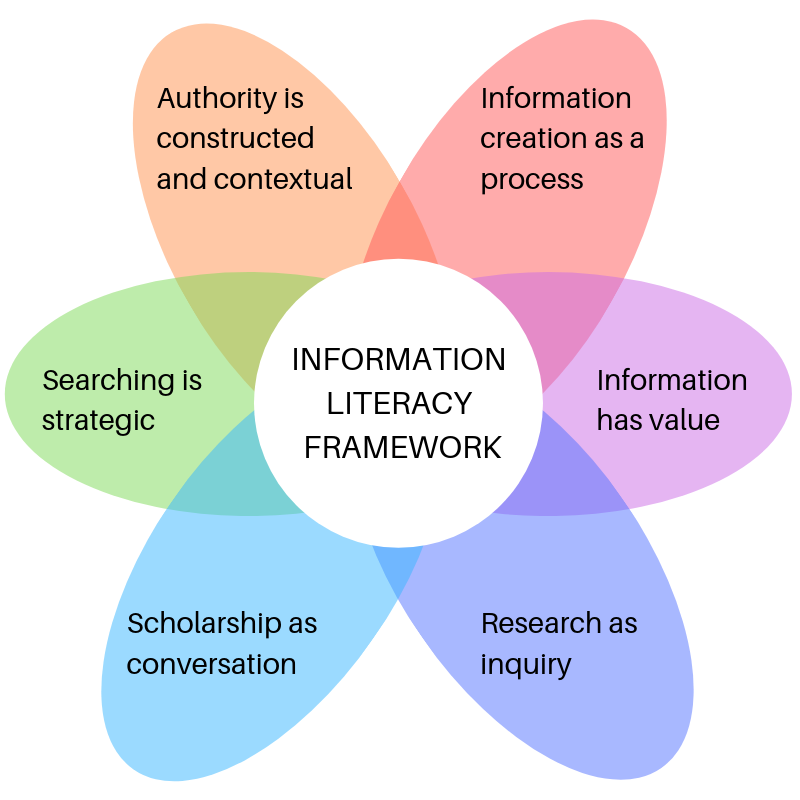

This guide will cover each frame of the “ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education ,” a document created by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) to help educators and librarians think about, teach, and practice information literacy (see Figure 11.1). The goal of this guide is to break down the basic concepts in the Framework and put them in accessible, digestible language so that we can think critically about the information we’re exposed to in our daily lives.

To start, let’s look at the ACRL definition of “information literacy,” so we have some context going forward:

Information Literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Boil that down and what you have are the essentials of information literacy: asking questions, finding information, evaluating information, creating information, and doing all of that responsibly and ethically.

We’ll be looking at each of the frames alphabetically, since that’s how they are presented in the framework. None of these frames is more important than another, and all need to be used in conjunction with the others, but we have to start somewhere, so alphabetical it is!

In order, the frames are

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

Just because we’re laying this out alphabetically does not mean you have to go through it in order. Some of the sections reference frames previously mentioned, but for the most part you can jump to wherever you like and use this guide however you see fit. You can also open up the framework using the link above or in the attached resources to read the framework in its original form and follow along with each section.

The following sections originally appeared as blog posts for the Texas A&M Corpus Christi’s library blog. Edits have been made to remove institutional context, but you can see the original posts in the Mary and Jeff Bell Library blog archives .

Authority is Constructed and Contextual

The first frame is “ Authority is Constructed and Contextual .” There’s a lot to unpack in that language, so let’s get started.

Start with the word “authority.”

At the root of “authority” is the word “author.” So start there: who wrote the piece of information you’re reading? Why are they writing? What stake do they have in the information they’re presenting? What are their credentials (You can straight up google their name to learn more about them)? Who are they affiliated with? A public organization? A university? A company trying to make a profit? Check it out.

Now let’s talk about how authority is “constructed.”

Have you ever heard the phrase “social construct”? Some people say gender is a social construct or language, written and spoken, is a construct. “Constructed” basically means humans made it up at some point to instill order in their communities. It’s not an observable, scientifically inevitable fact. When we say “authority” is constructed, we’re basically saying that we as individuals and as a society choose who we give authority to, and sometimes we might not be choosing based on facts.

A common way of assessing authority is by looking at an author’s education. We’re inclined to trust someone with a PhD over someone with a high school diploma because we think the person with a PhD is smarter. That’s a construct. We’re conditioned to think that someone with more education is smarter than people with less education, but we don’t know it for a fact.

There are a lot of reasons someone might not seek out higher education. They might have to work full time or take care of a family or maybe they just never wanted to go to college. None of these factors impact someone’s intelligence or ability to think critically.

If aliens land on South Padre Island, TX, there will be many voices contributing to the information collected about the event. Someone with a PhD in astrophysics might write an article about the mechanical workings of the aliens’ spaceship. Cool; they are an authority on that kind of stuff, so I trust them.

But the teenager who was on the island and watched the aliens land has first-hand experience of the event, so I trust them too. They have authority on the event even though they don’t have a PhD in astrophysics.

So, we cannot think someone with more education is inherently more trustworthy or smarter or has more authority than anyone else. Some people who are authorities on a subject are highly educated, some are not.

Likewise, let’s say I film the aliens landing and stream it live on Facebook. At the same time, a police officer gives an interview on the news that says something contradicting my video evidence. All of a sudden, I have more authority than the police officer. Many of us are raised to trust certain people automatically based on their jobs, but that’s also a construct. The great thing about critical thinking is that we can identify what is fact and fiction, and we can decide for ourselves who to trust.

The final word is “contextual.”

This one is a little simpler. If I go to the hospital and a medical doctor takes out my appendix, I’ll probably be pretty happy with the outcome. If I go to the hospital and Dr. Jill Biden, a professor of English, takes out my appendix, I’m probably going to be less happy with the results.

Medical doctors have authority in the context of medicine. Dr. Jill Biden has authority in the context of education. And Doctor Who has authority in the context of inter-galactic heroics and nice scarves.

This applies when we talk about experiential authority, too. If an eighth-grade teacher tells me what it’s like to be a fourth-grade teacher, I will not trust their authority. I will, however, trust a fourth-grade teacher to tell me about teaching fourth grade.

The Takeaway

Basically, when we think about authority, we need to ask ourselves, “Do I trust them? Why?” If they do not have experience with the subject (like witnessing an event or holding a job in the field) or subject expertise (like education or research), then maybe they aren’t an authority after all.

P.S. I’m sorry for the uncalled-for dig, Dr. Biden. I’m sure you’d do your best with an appendectomy.

Ask Yourself

- In what context are you an authority?

- If you needed to figure out how to do a kickflip on a skateboard, who would you ask? Who’s an authority in that situation?

Information Creation as a Process

The second frame is “ Information Creation as a Process .”

Information Creation

So first of all, let’s get this out of the way: everyone is a creator of information. When you write an essay, you’re creating information. When you log the temperature of the lizard tank, you’re creating information. Every Word Doc, Google Doc, survey, spreadsheet, Tweet, and PowerPoint that you’ve ever had a hand in? All information products. That YOU created. In some way or another, you created that information and put it out into the world.

One process you’re probably familiar with if you’re a student is the typical research paper. You know your professor wants about five to eight pages consisting of an introduction that ends in a thesis statement, a few paragraphs that each touch on a piece of evidence that supports your thesis, and then you end in a conclusion paragraph which starts with a rephrasing of your thesis statement. You save it to your hard drive or Google Drive and then you submit it to your professor.

This is one process for creating information. It’s a boring one, but it’s a process.

Outside of the classroom, the information-creation process looks different, and we have lots of choices to make.

One of the choices you’ll need to make is the mode or format in which you present information. The information I’m creating right now comes to you in the mode of an Open Educational Resource . Originally, I created these sections as blog posts. Those five-page essays I mentioned earlier are in the mode of essays.

When you create information (outside of a course assignment), it’s up to you how to package that information. It might feel like a simple or obvious choice, but some information is better suited to some forms of communication. And some forms of communication are received in a certain way, regardless of the information in them.

For example, if I tweet “Jon Snow knows nothing,” it won’t carry with it the authority of my peer-reviewed scholarly article that meticulously outlines every instance in which Jon Snow displays a lack of knowledge. Both pieces of information are accurate, but the processes I went through to create and disseminate the information have an effect on how the information is received by my audience.

And that is perhaps the biggest thing to consider when creating information: your audience.

The Audience Matters

If I just want my twitter followers to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then a tweet is the right way to reach them. If I want my tenured colleagues and other various scholars to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then I’m going to create a piece of information that will reach them, like a peer-reviewed journal article.

Often, we aren’t the ones creating information; we’re the audience members ourselves. When we’re scrolling on Twitter, reading a book, falling asleep during a PowerPoint presentation—we’re the audience observing the information being shared. When this is the case, we have to think carefully about the ways information was created.

Advertisements are a good example. Some are designed to reach a 20-year old woman in Corpus Christi through Facebook, while others are designed to reach a 60-year old man in Hoboken, NJ over the radio. They might both be selling the same car, and they’re going to put the same information (size, terrain, miles per gallon, etc.) in those ads, but their audiences are different, so their information-creation process is different, and we end up with two different ads for different audiences.

Be a Critical Audience Member

When we are the audience member, we might automatically trust something because it’s presented a certain way. I know that, personally, I’m more likely to trust something that is formatted as a scholarly article than I am something that is formatted as a blog. And I know that that’s biased thinking and it’s a mistake to make that assumption.

It’s risky to think like that for a couple of reasons:

- Looks can be deceiving. Just because someone is wearing a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not an axe murderer and just because something looks like a well-researched article, doesn’t mean it is one.

- Automatic trust unnecessarily limits the information we expose ourselves to. If I only ever allow myself to read peer-reviewed scholarly articles, think of all the encyclopedias and blogs and news articles I’m missing out on!

If I have a certain topic I’m really excited about, I’m going to try to expose myself to information regardless of the format and I’ll decide for myself (#criticalthinking) which pieces of information are authoritative and which pieces of information suit my needs.

Likewise, as I am conducting research and considering how best to share my new knowledge, I’m going to consider my options for distributing this newfound information and decide how best to reach my audience. Maybe it’s a tweet, maybe it’s a Buzzfeed quiz, or maybe it’s a presentation at a conference. But whatever mode I choose will also convey implications about me, my information creation process, and my audience.

You create information all of the time. The way you package and share it will have an effect on how others perceive it.

- Is there a form of information you’re likely to trust at first glance? Either a publication like a newspaper or a format like a scholarly article?

- Can you think of some voices that aren’t present in that source of information?

- Where might you look to find some other perspectives?

- If you read an article written by medical researchers that says chocolate is good for your health, would you trust the article?

- Would you still trust their authority if you found out that their research was funded by a company that sells chocolate bars? Funding and stakeholders have an impact on the creation process, and it’s worth thinking about how this can compromise someone’s authority.

Information Has Value

Onwards and upwards! We’re onto frame 3: “ Information Has Value .”

What Counts as Value?

There are a lot of different ways we value things. Some things, like money, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for goods and services. On the other hand, some things, like a skill, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for money (which we exchange for more goods and services). Some things are valuable to us for sentimental reasons, like a photograph or a letter. Some things, like our time, are valuable because they are finite.

The Value of Information

Information has all kinds of value.

One kind is monetary. If I write a book and it gets published, I’m probably going to make some money off of that (though not as much money as the publishing company will make). So that’s valuable to me.

But I’m also getting my name out into the world, and that’s valuable to me too. It means that when I apply for a job or apply for a grant, someone can google me and think, “Oh look! She wrote a book! That means she has follow-through and will probably work hard for us!” That kind of recognition is a sort of social value. That social value, by the way, can also become monetary value. If I’ve produced information, a university might give me a job, or an organization might fund my research. If I’ve invented a machine that will floss my teeth for me, the patent for my invention could be worth a lot of money (plus it’d be awesome. Cool factor can count as value.).

In a more altruistic slant, information is also valuable on a societal level. When we have more information about political candidates, for example, it influences how we vote, who we elect, and how our country is governed. That’s some really valuable information right there. That information has an effect on the whole world (plus outer space, if we elect someone who’s super into space exploration). If someone is trying to keep information hidden or secret, or if they’re spreading misinformation to confuse people, it’s probably a sign that the information they’re hiding is important, which is to say, valuable.

On a much smaller scale, think about the information on food packages. If you’re presented with calorie counts, you might make a different decision about the food you buy. If you’re presented with an item’s allergens, you might avoid that product and not end up in an Emergency Room with anaphylactic shock. You know what’s super valuable to me? NOT being in an Emergency Room!

But if you do end up in the Emergency Room, the information that doctors and nurses will use to treat your allergic reaction is extremely valuable. That value of that information is equal to the lives it’s saved.

Acting Like Information is Valuable

When we create our own information by writing papers and blog posts and giving presentations, it’s really important that we give credit to the information we’ve used to create our new information product for a couple of reasons.

First, someone worked really hard to create something, let’s say an article. And that article’s information is valuable enough to you to use in your own paper or presentation. By citing the author properly, you’re giving the author credit for their work, which is valuable to them. The more their article is cited, the more valuable it becomes because they’re more likely to get scholarly recognition and jobs and promotions.

Second, by showing where you’re getting your information, you’re boosting the value of your new information product. On the most basic level, you’ll get a higher grade on your paper, which is valuable to you. But you’re also telling your audience, whether it’s your professor or your boss or your YouTube subscribers, that you aren’t just making stuff up—you did the work of researching and citing, and that makes your audience trust you more. It makes the audience value your information more.

Remember early on when I said the frames all connect? “Information Has Value” ties into the other information literacy frames we’ve talked about, “Information Creation as a Process” and “Authority as Constructed and Contextual.” When I see you’ve cited your sources of information, then I, as the audience, think you’re more authoritative than someone who doesn’t cite their sources. I also can look at your information product and evaluate the effort you’ve put into it. If you wrote a tweet, which takes little time and effort, I’ll generally value it less than if you wrote a book, which took a lot of time and effort to create. I know that time is valuable, so seeing that you were willing to dedicate your time to create this information product makes me feel like it’s more valuable.

Information is valuable because of what goes into its creation (time and effort) and what comes from it (an informed society). If we didn’t value information, we wouldn’t be moving forward as a society, we’d probably have died out thousands of years ago as creatures who never figured out how to use tools or start a fire.

So continue to value information because it improves your life, your audiences’ lives, and the lives of other information creators. More importantly, if we stop valuing information a smarter species will eventually take over and it’ll be a whole Planet of the Apes thing and I just don’t have the energy for that right now.

- Can you think of some ways in which a YouTube video on dog training has value? Who values it? Who profits from it?

- Think of some information that would be valuable to someone applying to college. What does that person need to know?

Research as Inquiry

Easing on down the road, we’ve come to frame number 4: “ Research as Inquiry .”

“Inquiry” is another word for “curiosity” or “questioning.” I like to think of this frame as “Research as Curiosity,” because I think it more accurately captures the way our adorable human brains work.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

When you think to yourself, “How old is Madonna?” and you google it to find out she’s 62 (as of the creation of this resource), that’s research! You had a question (“how old is Madonna?”), you applied a search strategy (googling “Madonna age”) and you found an answer (62). That’s it! That’s all research has to be!

But it’s not all research can be. This example, like most research, is comprised of the same components we use in more complex situations. Those components are a question and an answer, inquiry and research, “how old is Madonna?” and “62.” But when we’re curious, we go back to the inquiry step again and ask more questions and seek more answers. We’re never really done, even when we’ve answered the initial question and written the paper and given the presentation and received accolades and awards for all our hard work. If it’s something we’re really curious about, we’ll keep asking and answering and asking again.

If you’re really curious about Madonna, you don’t just think, “How old is Madonna?” You think “How old is Madonna? Wait, really ? Her skin looks amazing! What’s her skincare routine? Seriously, what year was she born? Oh my god, she wrote children’s books! Does my library have any?” Your questions lead you to answers which, when you’re really interested in a topic, lead you to more and more questions. Humans are naturally curious ; we have this sort of instinct to be like, “huh, I wonder why that is?” and it’s propelled us to learn things and try things and fail and try again! It’s all research as inquiry.

And to satisfy your curiosity, yes, the library I currently work at does own one of Madonna’s children’s books. It’s called The Adventures of Abdi , and you can find it in our Juvenile Collection on the second floor at PZ8 M26 Adv 2004. And you can find a description of her skincare routine in this article from W Magazine: https://www.wmagazine.com/story/madonna-skin-care-routine-tips-mdna . You’re welcome.

Identifying an Information Need

One of the tricky parts of research as inquiry is determining a situation’s information need. It sounds simple to ask yourself, “What information do I need?” and sometimes we do it unconsciously. But it’s not always easy. Here are a few examples of information needs:

- You need to know what your niece’s favorite Paw Patrol character is so you can buy her a birthday present. Your research is texting your sister. She says, “Everest.” And now you’re done. You buy the present, you’re a rock star at the birthday party. Your information need was a short answer based on a three-year old’s opinion.

- You’re trying to convince someone on Twitter that Nazis are bad. You compile a list of opinion pieces from credible news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times , gather first-hand narratives of Holocaust survivors and victims of hate crimes, find articles that debunk eugenics, etc. Your information need isn’t scholarly publications, it’s accessible news and testimonials. It’s articles a person might actually read in their free time, articles that aren’t too long and don’t require access to scholarly materials that are sometimes behind paywalls.

- You need to write a literature review for an assignment, but you don’t know what a literature review is. So first you google “literature review example.” You find out what it is, how one is created, and maybe skim a few examples. Next, you move to your library’s website and search tool and try “oceanography literature review,” and find some closer examples. Finally, you start conducting research for your own literature review. Your information need here is both broader and deeper. You need to learn what a literature review is, how one is compiled, and how one searches for relevant scholarly articles in the resources available to you.

Sometimes it helps to break down big information needs into smaller ones. Take the last example, for instance: you need to write a literature review. What are the smaller parts?

- Information Need 1: Find out what a literature review is

- Information Need 2: Find out how people go about writing literature reviews

- Information Need 3: Find relevant articles on your topic for your own literature review

It feels better to break it into smaller bits and accomplish those one at a time. And it highlights an important part of this frame that’s surprisingly difficult to learn: ask questions. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know what it is, so ask. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know how to find articles, so ask. The quickest way to learn is to ask questions. Once you stop caring if you look stupid, and once you realized no one thinks poorly of people who ask questions, life gets a lot easier.

So, let’s add this to our components of research: ask a question, determine what you need in order to thoroughly answer the question, and seek out your answers. Not too painful, and when you’re in love with whatever you’re researching, it might even be fun.

- When you have a question, ask it.

- When you’re genuinely interested in something, keep asking questions and finding answers.

- When you have a task at hand, take a second to think realistically about the information you’ll need to accomplish that task. You don’t need a peer-reviewed article to find out if praying mantises eat their mates, but you might if you want to find out why.

- What’s the last thing you looked up on Wikipedia? Did you stop when you found an answer, or did you click on another link and another link until you learned about something completely different?

- If you can’t remember, try it now! Search for something (like a favorite book or tv show) and click on linked words and phrases within Wikipedia until you learn something new!

- What was the last thing you researched that you were really excited about? Do you struggle when teachers and professors tell you to “research something that interests you”? Instead, try asking yourself, “What makes me really angry?” You might find you have more interests than you realized!

Scholarship as Conversation

We’ve made it friends! My favorite frame: “ Scholarship as Conversation .” Is it weird to have a favorite frame of information literacy? Probably. Am I going to talk about it anyway? You betcha!

What does “Scholarship as Conversation” mean?