The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

Read 12 Masterful Essays by Joan Didion for Free Online, Spanning Her Career From 1965 to 2013

in Literature , Writing | January 14th, 2014 3 Comments

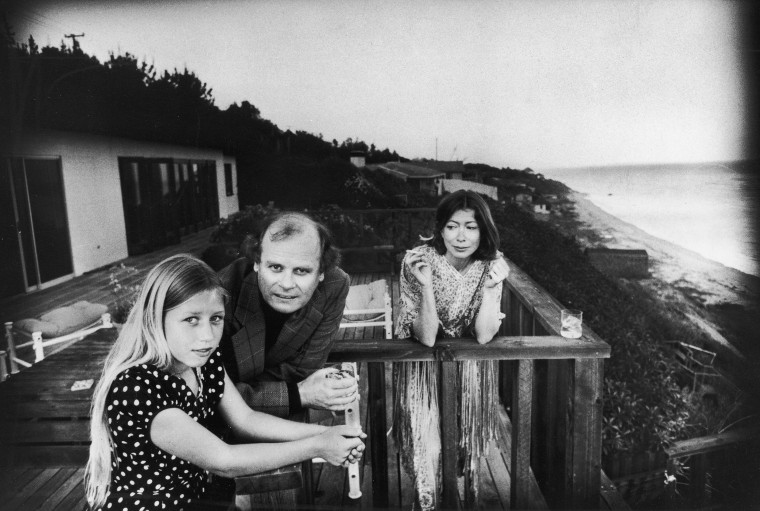

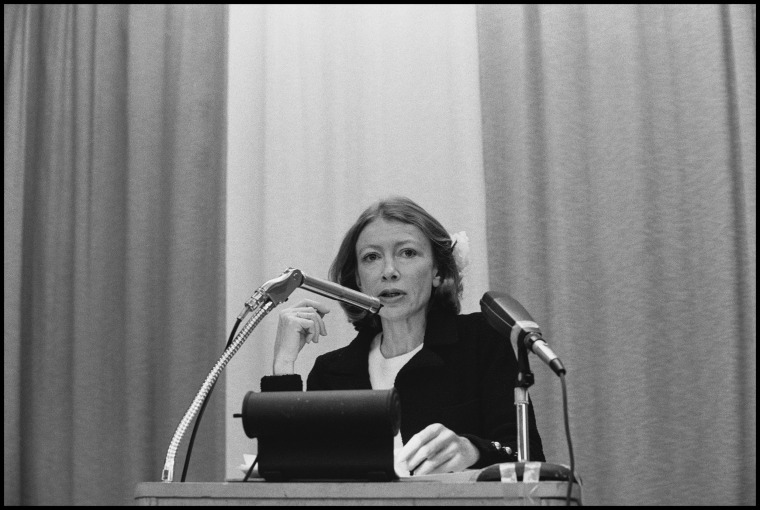

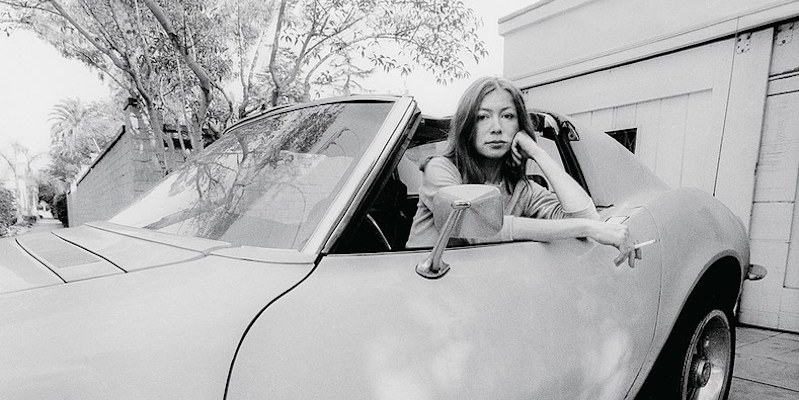

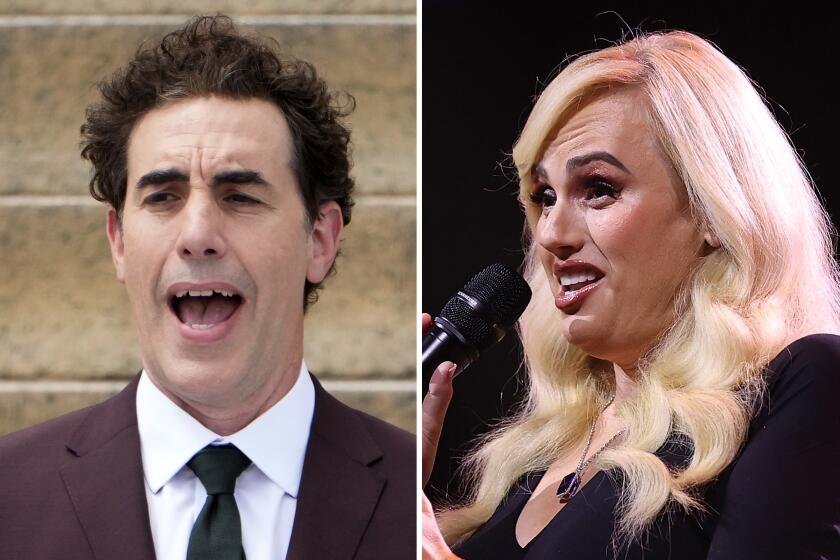

Image by David Shankbone, via Wikimedia Commons

In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time—to prod her reader. She rhetorically asks and answers: “…was anyone ever so young? I am here to tell you that someone was.” The wry little moment is perfectly indicative of Didion’s unsparingly ironic critical voice. Didion is a consummate critic, from Greek kritēs , “a judge.” But she is always foremost a judge of herself. An account of Didion’s eight years in New York City, where she wrote her first novel while working for Vogue , “Goodbye to All That” frequently shifts point of view as Didion examines the truth of each statement, her prose moving seamlessly from deliberation to commentary, annotation, aside, and aphorism, like the below:

I want to explain to you, and in the process perhaps to myself, why I no longer live in New York. It is often said that New York is a city for only the very rich and the very poor. It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city only for the very young.

Anyone who has ever loved and left New York—or any life-altering city—will know the pangs of resignation Didion captures. These economic times and every other produce many such stories. But Didion made something entirely new of familiar sentiments. Although her essay has inspired a sub-genre , and a collection of breakup letters to New York with the same title, the unsentimental precision and compactness of Didion’s prose is all her own.

The essay appears in 1967’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem , a representative text of the literary nonfiction of the sixties alongside the work of John McPhee, Terry Southern, Tom Wolfe, and Hunter S. Thompson. In Didion’s case, the emphasis must be decidedly on the literary —her essays are as skillfully and imaginatively written as her fiction and in close conversation with their authorial forebears. “Goodbye to All That” takes its title from an earlier memoir, poet and critic Robert Graves’ 1929 account of leaving his hometown in England to fight in World War I. Didion’s appropriation of the title shows in part an ironic undercutting of the memoir as a serious piece of writing.

And yet she is perhaps best known for her work in the genre. Published almost fifty years after Slouching Towards Bethlehem , her 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking is, in poet Robert Pinsky’s words , a “traveler’s faithful account” of the stunningly sudden and crushing personal calamities that claimed the lives of her husband and daughter separately. “Though the material is literally terrible,” Pinsky writes, “the writing is exhilarating and what unfolds resembles an adventure narrative: a forced expedition into those ‘cliffs of fall’ identified by Hopkins.” He refers to lines by the gifted Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins that Didion quotes in the book: “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap / May who ne’er hung there.”

The nearly unimpeachably authoritative ethos of Didion’s voice convinces us that she can fearlessly traverse a wild inner landscape most of us trivialize, “hold cheap,” or cannot fathom. And yet, in a 1978 Paris Review interview , Didion—with that technical sleight of hand that is her casual mastery—called herself “a kind of apprentice plumber of fiction, a Cluny Brown at the writer’s trade.” Here she invokes a kind of archetype of literary modesty (John Locke, for example, called himself an “underlabourer” of knowledge) while also figuring herself as the winsome heroine of a 1946 Ernst Lubitsch comedy about a social climber plumber’s niece played by Jennifer Jones, a character who learns to thumb her nose at power and privilege.

A twist of fate—interviewer Linda Kuehl’s death—meant that Didion wrote her own introduction to the Paris Review interview, a very unusual occurrence that allows her to assume the role of her own interpreter, offering ironic prefatory remarks on her self-understanding. After the introduction, it’s difficult not to read the interview as a self-interrogation. Asked about her characterization of writing as a “hostile act” against readers, Didion says, “Obviously I listen to a reader, but the only reader I hear is me. I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.”

It’s a curious statement. Didion’s cutting wit and fearless vulnerability take in seemingly all—the expanses of her inner world and political scandals and geopolitical intrigues of the outer, which she has dissected for the better part of half a century. Below, we have assembled a selection of Didion’s best essays online. We begin with one from Vogue :

“On Self Respect” (1961)

Didion’s 1979 essay collection The White Album brought together some of her most trenchant and searching essays about her immersion in the counterculture, and the ideological fault lines of the late sixties and seventies. The title essay begins with a gemlike sentence that became the title of a collection of her first seven volumes of nonfiction : “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Read two essays from that collection below:

“ The Women’s Movement ” (1972)

“ Holy Water ” (1977)

Didion has maintained a vigorous presence at the New York Review of Books since the late seventies, writing primarily on politics. Below are a few of her best known pieces for them:

“ Insider Baseball ” (1988)

“ Eye on the Prize ” (1992)

“ The Teachings of Speaker Gingrich ” (1995)

“ Fixed Opinions, or the Hinge of History ” (2003)

“ Politics in the New Normal America ” (2004)

“ The Case of Theresa Schiavo ” (2005)

“ The Deferential Spirit ” (2013)

“ California Notes ” (2016)

Didion continues to write with as much style and sensitivity as she did in her first collection, her voice refined by a lifetime of experience in self-examination and piercing critical appraisal. She got her start at Vogue in the late fifties, and in 2011, she published an autobiographical essay there that returns to the theme of “yearning for a glamorous, grown up life” that she explored in “Goodbye to All That.” In “ Sable and Dark Glasses ,” Didion’s gaze is steadier, her focus this time not on the naïve young woman tempered and hardened by New York, but on herself as a child “determined to bypass childhood” and emerge as a poised, self-confident 24-year old sophisticate—the perfect New Yorker she never became.

Related Content:

Joan Didion Reads From New Memoir, Blue Nights, in Short Film Directed by Griffin Dunne

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

10 Free Stories by George Saunders, Author of Tenth of December , “The Best Book You’ll Read This Year”

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (3) |

Related posts:

Comments (3), 3 comments so far.

“In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time,..”

Dead link to the essay

It should be “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” with the “s” on Towards.

Most of the Joan Didion Essay links have paywalls.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Book lists by.

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

6 Essays By Joan Didion You Should Know

Joan Didion is lauded as one of the best literary journalists to emerge from the New Journalism school in the ’60s, among Tom Wolfe , Terry Southern and Hunter S. Thompson, and one of California’s wittiest contemporary writers . Best known for her sharply reported stories that service frequently dystopian and despondent cultural commentary, even Didion’s more journalistic works are in part personal essay. It’s precisely her authorial presence that lends credence, honesty and depth to her work. Her subjectivity makes her observations all the more resonant, and in a way, more accurate too. Here’s a look at some of the California writer’s greatest hits.

‘some dreamers of the golden dream’.

‘This is a story about love and death in the golden land, and begins with the country,’ the essay begins. Making good on her promise, this piece reports a lascivious tale of adultery and murder in San Bernardino County in 1966. In true Didion form, however, atmosphere and place play characters just as important as the perpetrators and, in that way, this piece is about much more than the details of a single crime.

‘John Wayne: A Love Song’

Though this essay presents itself as an ode the great American frontiersman of the silver screen, it charts a loss of innocence – personal, though perhaps also cultural – against Wayne’s larger than life persona . ‘In a world we understand early to be characterized by venality and doubt and paralyzing ambiguities, he suggested another world… a place where a man could move free, could make his own code and live by it.’

Having kept a notebook from the age of five, Didion considers the compulsion to capture our lives. She writes, ‘however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I.” This observation seems especially fitting for a writer who candidly reports through the filter of the self.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

‘On Self Respect’

This philosophical musing pays homage to the wrestling with the self that perhaps writers know best. It was first published in Vogue magazine in 1961, where it can be found in its original form . ‘To assign unanswered letters their proper weight, to free us from the expectations of others, to give us back to ourselves – there lies the great, the singular power of self-respect.’

‘The Santa Ana’

Didion calls upon the eerie desert mythology of the Santa Anas, the wicked winds that brings a tangible unease and tension to Los Angeles whenever they blow through the city. In this essay, LA is not always sunny as it’s so often portrayed. In this strange ode to place, Didion writes, ‘the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The winds shows us how close to the edge we are.’

‘Goodbye to All That’

In one of Didion’s most known essays, she recounts a love affair with New York City that calls upon the city’s deeply arresting aura with delicious turns of phrase: ‘I would stay in New York, I told him, just six months, and I could see the Brooklyn Bridge from my window. As it turned out the bridge was the Triborough, and I stayed eight years.’

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Guides & Tips

The solo traveler’s guide to lake tahoe.

A Solo Traveler's Guide to California

See & Do

Off-the-grid travel destinations for your new year digital detox .

Places to Stay

The best vacation villas to rent in california.

The Best Hotels With Suites to Book in San Francisco

The Best Hotels to Book in Calistoga, California

The Best Accessible and Wheelchair-Friendly Hotels to Book in California

The Best Beach Hotels to Book in California, USA

The Best Hotels in Santa Maria, California

The Best Hotels to Book in Santa Ana, California

The Best Family-Friendly Hotels to Book in San Diego, California

The Best Motels to Book in California

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 787009

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

Shop NewBeauty Reader’s Choice Awards winners — from $13

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Joan Didion’s best books, from essays to fiction

On Thursday, it was announced that prolific writer Joan Didion had died at the age of 87.

An executive at her publisher, Knopf, confirmed the author's death to TODAY in an email and said that Didion passed away at her home in Manhattan from Parkinson's disease.

Here, we round up seven necessary reads by the late author, who was best known for work on mourning and essays and magazine contributions that captured the American experience.

Here are the best books by Joan Didion:

'the year of magical thinking' (2005).

Probably her best known work, this gutting work of non-fiction profiles Didion's experience grieving her husband John Gregory Dunne while caring for comatose daughter Quintana Roo Dunne.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" quickly became an iconic representation of mourning, capturing the sorrow and ennui of that period. It won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Awards, and was later adapted into a play starring Vanessa Redgrave.

'Blue Nights' (2011)

A continuation of what is started in "The Year of Magical Thinking," this poignant 2011 work of non-fiction features personal and heartbreaking memories of Quintana, who passed away at the age of 39, not long after Didion's husband died.

"It is a searing inquiry into loss and a melancholy meditation on mortality and time,” wrote book critic Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times.

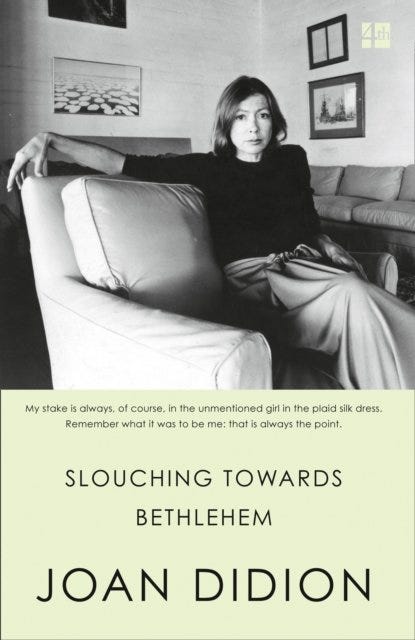

'Slouching Towards Bethlehem' (1968)

Didion's first collection of nonfiction writing is revered as an essential portrait of America — particularly California — in the 1960s.

It focuses on her experience growing up in the Sunshine state, icons of that time John Wayne and Howard Hughes, and the essence of Haight-Ashbury, a neighborhood in San Francisco that became the heart of the counterculture movement.

'The White Album' (1979)

A reflective collection of essays, "The White Album" explores several of the same topics Didion touched on in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," this time focusing on the history and politics of California in the late 1960s and early '70s. Its matter-of-fact and intimate stories give the reader a feeling of what California and the atmosphere was like during that time period.

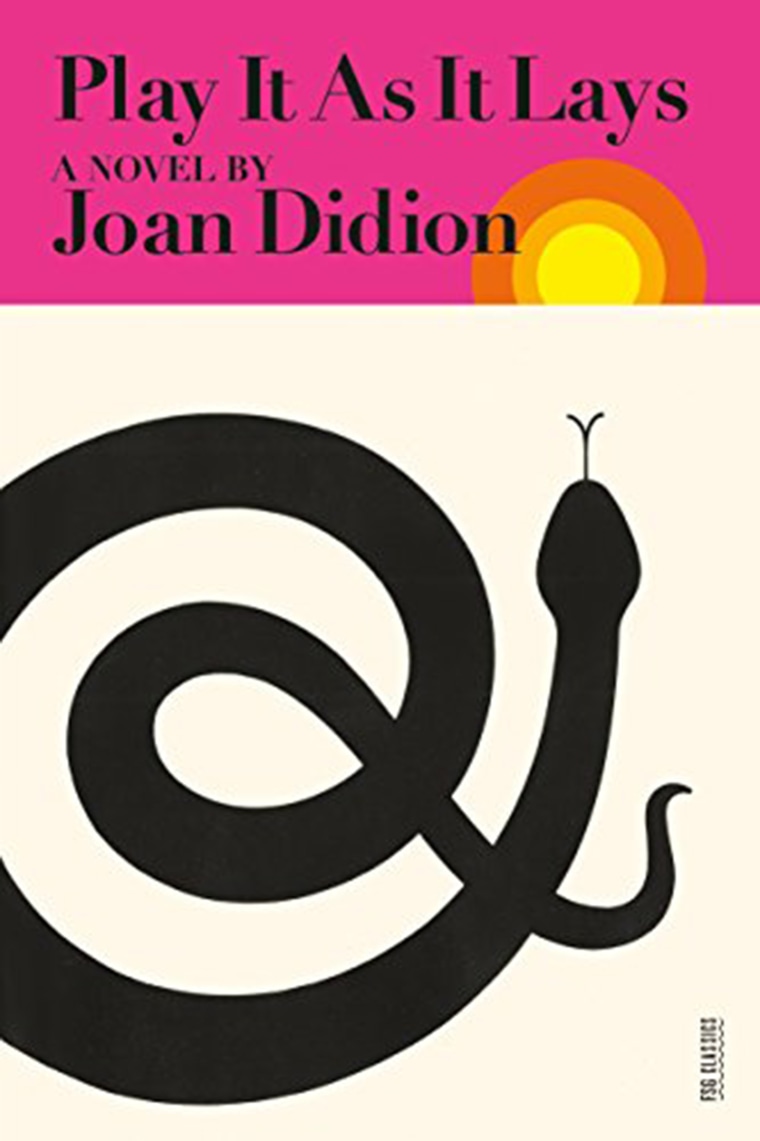

'Play it as it Lays' (1970)

Set during a time before Roe vs. Wade, this terrifying and at times disturbing novel profiles a struggling actress living in Los Angeles whose life begins to unravel after she has a back-alley abortion.

"(Didion) writes with a razor, carving her characters out of her perceptions with strokes so swift and economical that each scene ends almost before the reader is aware of it, and yet the characters go on bleeding afterward," wrote book critic John Leonard for the New York times.

'Miami' (1987)

A great example of Didion's journalistic work, "Miami" paints a portrait of life for Cuban exiles in the south Florida city.

Didion writes a stunning and passionate page-turner set against the backdrop of Miami’s decline caused by economic and political changes with the refugee immigration from Cuba after Fidel Castro’s rise to power.

Alexander Kacala is a reporter and editor at TODAY Digital and NBC OUT. He loves writing about pop culture, trending topics, LGBTQ issues, style and all things drag. His favorite celebrity profiles include Cher — who said their interview was one of the most interesting of her career — as well as Kylie Minogue, Candice Bergen, Patti Smith and RuPaul. He is based in New York City and his favorite film is “Pretty Woman.”

Browse By Category

Interiors & decor, fashion & style, health & wellness, relationships, w&d product, food & entertaining, travel & leisure, career development, book a consultation, amazon shop, shop my home, designing a life well-lived, essential joan didion pieces to read now, later, forever, wit & delight lives where life and style intersect., more about us ›.

Interiors & Decor

Fashion & Style

Health & Wellness

Most popular, how writing a personal contract improved my life (and tips for creating your own), i’ve remodeled 3 kitchens—these are my biggest design regrets in each one, 3 ways to optimize your closet (plus, a tour of my new closet space).

“Syntax and sensibility: Nobody wed them quite like Joan Didion,” says New York Times columnist Frank Bruni , in a profession of love to Joan and her unusually placed prepositional phrases.

Nobody does anything quite like Joan Didion. The way she almost unsentimentally audits death and memory. The way she waves a bony index finger, more knowing than yours. The way she, without judgment, sets the scene of a five-year-old named Susan on LSD in the height of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury hippie culture.

She’s fearless, she’s cool as hell, she’s thisbig and could paper-cut you to death page-by-page with any one of her masterpieces.

Where do you start with her repertoire? She’s done it all: fiction, essays, political commentaries, memoirs, journalistic pieces and just about everything in between. Joan, now 83, has never not been relevant, but she’s in the headlines again these days, as Netflix recently debuted the long-awaited Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold , a documentary-slash-love-letter made by her nephew, Griffin Dunne. (Yes, son of Dominick Dunne, Hollywood legend.)

Have you cozied up and clicked play on The Center Will Not Hold already? Great. Either way, let’s use this occasion to revisit Joan the Great, or Our Mother of Sorrows, as Vanity Fair once begrudgingly called her.

Below are some of Joan’s essential readings, though really, every subject paired with a predicate strung together by Joan is essential. W hether you’re picking up The Year of Magical Thinking for the first time (what’s your address? I’ll send you tissues) or you’re paging through Slouching Towards Bethlehem again , scrounging for the meaning of life for the umpteenth time, happy reading.

The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) Don’t lie down while reading The Year of Magical Thinking , or you’ll choke on your tears.

The title refers to the psychological and anthropological phrase – cross your fingers enough and you’ll avoid the inevitable – though it may as well been called The Year of Joan Didn’t Deserve or The Year You Wouldn’t Wish Upon the Devil , as it tiptoes along the time following the death of Joan’s husband, fellow writer John Gregory Dunne, which coincided with the hospitalization of her beloved daughter Quintana Roo. The seemingly small scenes make your heart hurt the most. Like when Joan, shortly after John’s death, stares into his closet, remarking that she can’t give his things away – what if John comes back for them? It’s raw, it’s brave, it’s beautiful. It’ll ruin you and wreck you and rebuild you.

The Year of Magical Thinking is a seminal book on grief and bereavement and it’s simply a must read for any thinking, feeling human being. No wonder it won the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

“Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

“I know why we try to keep the dead alive: we try to keep them alive in order to keep them with us. I also know that if we are to live ourselves there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead.”

“We were not having any fun, he had recently begun pointing out. I would take exception (didn’t we do this, didn’t we do that) but I had also known what he meant. He meant doing things not because we were expected to do them or had always done them or should do them but because we wanted to do them. He meant wanting. He meant living.”

On Self-Respect (1961) Joan first proved her astute skills in Vogue , in 1961, with the publishing of On Self-Respect (which you can also find in Slouching Towards Bethlehem ). New to the Vogue staff, Joan was given the opportunity to write the essay after another writer assigned to the piece failed to follow through. The title was already placed as a headline on the cover, so Joan swept in and wrote her first major piece – elegant and critical and thoughtful – not only to an exact word count, to place into the layout, but to an exact character count. She’s been flexing her power, letter by letter, ever since.

Read it in full here .

“Once, in a dry season, I wrote in large letters across two pages of a notebook that innocence ends when one is stripped of the delusion that one likes oneself.”

“Self-respect is something that our grandparents, whether or not they had it, knew all about. They had instilled in them, young, a certain discipline, the sense that one lives by doing things one does not particularly want to do, by putting fears and doubts to one side, by weighing immediate comforts against the possibility of larger, even intangible, comforts.”

Goodbye to All That (1967) Joan set the standard for “New York, I love you, but I must leave you” essays, now floating around every book and blog, with Goodbye to All That in 1967. I could list a dozen essays (I’ll spare you) that trample over the trope, the New York love affair gone wrong arc. Joan did it first. She wrote about her love/hate/love relationship with the city, how it gave her life and then took that life. “It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends. I can remember now, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, when New York began for me, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment it ended, can never cut through the ambiguities and second starts and broken resolves to the exact place on the page where the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was.” “ I was in love with New York. I do not mean ‘love’ in any colloquial way, I mean that I was in love with the city, the way you love the first person who ever touches you and you never love anyone quite that way again.”

Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) Perhaps Joan’s most renowned series of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem now acts as a time capsule for a life and time many of us never lived yet sometimes dream about. With a few exceptions, most of the essays are set in California in the ’60s, giving a vivid vibe of life then+there – including mass murders, kidnapped heiresses and the explosion of American counterculture.

That five-year-old named Susan, the one on LSD? You’ll find her in the titular essay, a famous piece about the sex-and-drug-filled Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco in the ’60s. Susan is the center of the disturbing passage, as well as the most chilling scene of The Center Will Not Hold . While discussing Goodbye , Joan – then a mother to a young girl herself – is asked what it was like to find the kindergartener high.

After a long pause, waving her arm about, she says simply, with a slight smile, “It was gold.” That’s the audacious Joan, the one who could immerse herself into any culture without judgment and the one who knows a journalistic goldmine when she finds it, the one we know, we love.

The entire book is a classic collection of journalism and includes a few of the essays mentioned above: Goodbye to All That and On Self-Respect . Perhaps my favorite piece though is O n Keeping a Notebook . (At least today it is. Ask again tomorrow.)

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

The White Album (1979) If Slouching Towards Bethlehem didn’t earn Joan the title of California’s most prominent voice, her 1979 collection of essays, The White Album , did. The New York Times review of The White Album , after claiming “California belongs to Joan Didion,” just as Kilimanjaro belongs to Ernest Hemingway and Oxford, Mississippi belongs to William Faulkner, says, “Joan Didion’s California is a place defined not so much by what her unwavering eye observes, but by what her memory cannot let go.”

Her memories are worth a read.

“ We tell ourselves stories in order to live…We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices.”

“I suppose everything had changed and nothing had.”

Play It As It Lays (1970) Joan writes what she knows best, even when tackling fiction: the American west, angst, despair. This short but not-so-sweet novel tells the story of Maria and captures an intense mood of a teetering woman with just enough words, no more. I won’t give any more away.

“There was silence. Something real was happening: this was, as it were, her life. If she could keep that in mind she would be able to play it through, do the right thing, whatever that meant.”

“Everything goes. I am working very hard at not thinking about how everything goes.”

Blue Nights (2011) Think of Blue Nights as The Year of Magical Thinking, Part II , the companion piece Joan never wanted to write. Before Magical Thinking was even published, Joan’s daughter Quintana Roo died at just 39 years old. Joan refused to amend it though, instead, writing an entire new ode to the new type of grief she felt – a mother’s grief, compounded by a wife’s grief. It touches on themes of parenthood, failure, adoption, and memory, as well as memory’s ultimate uselessness if you don’t appreciate the moment as it’s occurring.

Whatever sense Joan had made out of her life, she lost it alongside losing John and then Quintana, now living a mother’s nightmare. Did she protect Quintana enough? Pay enough attention to her? Did she love her enough?

Whereas Magical Thinking is a sharp and polished masterpiece, Blue Nights feels as if Joan has taken a beating. She has. She’s older now, baffled at the state of her life, too tired to attempt to make sense of the chaos. Yet she’s graceful as ever in her words. Read for yourself.

“This book is called ‘ Blue Nights ’ because at the time I began it I found my mind turning increasingly to illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness. Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning.”

“Memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember.”

“In theory mementos serve to bring back the moment. In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here. How inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here is something else I could never afford to see.”

Additional readings, if you just can’t get enough:

- Insider Baseball (1988)

- Eye on the Prize (1992)

- The Teachings of Speaker Gingrich (1995)

- Fixed Opinions, or the Hinge of History (2003)

- Politics in the New Normal America (2004)

- The Case of Theresa Schiavo (2005)

- The Deferential Spirit (2013)

- California Notes (2016)

- Joan’s packing list from The White Album

- Joan’s favorite books of all time, delightfully hand-written

Images via Kate Worum .

Megan is a writer, editor, etc.-er who muses about life, design and travel for Domino, Lonny, Hunker and more. Her life rules include, but are not limited to: zipper when merging, tip in cash and contribute to your IRA. Be a pal and subscribe to her newsletter Night Vision or follow her on Instagram .

BY Megan McCarty - December 4, 2017

Like what you see? Share Wit & Delight with a friend:

Reading this post convinces me I should read all of Joan Didion’s works! – Charmaine Ng | Architecture & Lifestyle Blog http://charmainenyw.com

Megan, Thank you for a further introduction to the writing of Joan Didion. I recently subscribed to the “Saturday Evening Post” email newsletter, and she is featured in their fiction section along with many other authors of note. I plan to read her books “Democracy” and “Play It As It Lays” for a sample of her fiction. My personal efforts in writing are aimed towards the short story and mostly general fiction. Thank you once again.

David Russell, Michigan

Awesome post really interesting thanks for your work.

Most-read posts:

Did you know W&D now has a resource library of Printable Art, Templates, Freebies, and more?

take me there

Get our best w&d resources, for designing a life well-lived.

7 Versatile Spring Wardrobe Basics to Add to Your Closet in 2024

7 of My Favorite Winter-to-Spring Outfits I’ve Worn Lately

8 Quick and Easy Spring Decor Ideas That Will Refresh Your Home

6 Mindset Shifts That Have Changed My Life for the Better

The Key Wellness Pillars and Habits I’m Prioritizing in My Life This Year

My 2024 Daily Routine Prioritizes What Matters—Here’s What It Looks Like

More stories.

Thank you for being here. For being open to enjoying life’s simple pleasures and looking inward to understand yourself, your neighbors, and your fellow humans! I’m looking forward to chatting with you.

Hi, I'm Kate. Welcome to my happy place.

ABOUT WIT & DELIGHT

follow @WITANDDELIGHT

A LIFE THAT

Follow us on instagram @witanddelight_, designing a life well-lived.

fashion & style

Get our best resources.

Did you know W&D now offers Digital Art, Templates, Freebies, & MORE?

legal & Privacy

Wait, wait, take me there.

Site Credit

Accessibility STatement

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Let Me Tell You What I Mean by Joan Didion review – elegant essays spanning four decades

Rejection letters, California dreams and clear reflections on writing in a collection that explores self-doubt

I n the first essay of this new volume of previously uncollected pieces, Joan Didion makes a case against newspapers. Too often, she argues, their reporting style rests on “a quite factitious ‘ objectivity’”, which “lends the entire venture a mendacity” by failing to make explicit the writer’s own particular set of influences and biases. Didion praises instead magazines that cultivate a personal voice, and which aim to impart character and atmosphere rather than straightforward information: “They assume that the reader is a friend, that he is disturbed about something, and that he will understand if they talk to him straight; this assumption of a shared language and a common ethic lends their reports a considerable cogency of style.” Often, she concludes, the real story is “the story not in the newspaper”.

This could be read as a slanted manifesto for Didion’s own style. Across her 60-year career, from her landmark essay collections Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979), through her formally innovative novels, to her devastating 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking , Didion has established a way of narration that focuses not so much on events as on subtexts, atmospheres and perceptions. She is usually present in her essays as a voice rather than a character, observer rather than participant – though the boundaries regularly blur. Yet even when she’s not saying directly what she’s feeling, it’s there in the architecture of every cool, clear sentence, in the sounds, gestures and images on which she chooses to focus her attention.

At university, Didion writes here in mock self-deprecation, “I would try to contemplate the Hegelian dialectic and would find myself concentrating instead on a flowering pear tree outside my window and the particular way the petals fell on my floor”. Half of the 12 essays in this collection were written for the Saturday Evening Post in the late 1960s, while the latest is from 2000; in them we see Didion exploring the possibility of that attention to detail, working out who exactly the “I” in her writing is, and what it is she’s seeing.

Didion’s essay collections have always included overtly personal moments – “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce,” she writes in “In the Islands” from The White Book , adding: “I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind.” This new collection contains several pieces of relatively straight autobiography: a funny essay describing the pain of her rejection from Stanford and subsequent summer spent “in sullen but mild rebellion” (“On Being Unchosen by the College of One’s Choice”); “Telling Stories”, which describes how out of place the 19-year-old Didion felt in the writers’ workshop she took for a semester in 1954, attempting to remain inconspicuous by shrinking into her raincoat while others regaled the group with experiences that seemed far more redolent of the “writer’s life” – international, glamorous, drug-induced – than anything Didion had known growing up in Sacramento. (She went on to take a job composing advertising copy for Vogue, which she credits with teaching her to write.) The same essay includes a ream of rejection letters for an early short story widely condemned as too depressing: “I’m sorry,” wrote a representative of Good Housekeeping magazine, “we are seldom inclined to give our readers this bad a time.”

But the pieces most revealing of Didion’s self are those that discuss the act of writing itself. In “Why I Write” (1976) Didion directly confronts the question of the first person – of what it means for a writer to assume an identity on the page and a relationship with an invisible reader. “In many ways,” she observes, “writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind .” In another essay, on Hemingway’s style, she parses precisely how the very grammar of his sentences reveal “a certain way of looking at the world”: Didion too has a specific way of looking that binds together all her work, whether she’s watching Nancy Reagan pretend to pick flowers for a photoshoot, attending a meeting of Gamblers Anonymous or a reunion of airforce veterans in a Las Vegas hospitality suite, or parsing the mission statement of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia LLC. Didion writes of “needing room in which to play with what I did not understand”. Her pieces often feel ambiguous, even ambivalent, and her detachment can at times be bemusing: the reader is left wondering where her stake is grounded in the stories she tells. Yet her particular skill lies in asking questions too far-reaching to be contained on the page, that reverberate far beyond the essay, as her images lodge themselves in the reader’s conscience.

The collection – expansively introduced by Hilton Als – touches on many of the themes that run through Didion’s work: the power of illusion, which she learned about at Vogue and later in Hollywood; the unspoken dynamics of makeshift, often precarious communities; the dangerous thrill of pursuing dreams. Recalling San Simeon, the castle on a hill in California which she would glimpse from the highway as a child, she reflects on the impact of knowing that just beyond reach lay this opulent paradise of shimmering turrets and battlements. “San Simeon,” she writes, “was an imaginative idea that affected me, shaped my own imagination in the way that all children are shaped by the actual and emotional geography of the place in which they grow up, by the stories they are told and the stories they invent.” There’s an echo here of Didion’s most famous line: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In that essay – “The White Album” – Didion describes a period between 1966 and 1971 when she “I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself”. Let Me Tell You What I Mean , its chapters largely rooted in this discombobulating period, is a valuable addition to the literature of self-doubt and self-awareness, an elegant untangling of what and why we remember and forget.

- Joan Didion

Most viewed

We earn a commission for products purchased through some links in this article.

Joan Didion: A guide to five of her most influential books

An overview of the Didion books you'll revisit for the rest of your days

Joan Didion inspired countless writers and readers to put pen to paper and write about the world as they see it. Her unique style, restrained yet honest, affecting yet never sentimental, is peerless. Famed for her incisive depictions of American life and personal journalism, she never wasted a word, nor a character. Her seminal essay for Vogue , On Self-Respect first published in 1961, was written not to a word count or a line count, but to an exact character count.

Didion's work chronicled the mood of the '60s, the highs and the lows, as well as the human experience in general - few writers have explored the subject of death and loss with as much insight, control or candour. Her skill lay not only in her style of prose, but her ability to astutely observe the behaviour of others. She saw what others missed.

Here, we celebrate five of her most influential books.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968

Although Slouching Towards Bethlehem wasn't Didion's first book ( Run, River of 1963 was), it was the one that cemented her as a prominent writer. A collection of essays about California in the '60s, her work explores the beauty and the ugliness of the decade, from the hippy community of San Francisco's Haight Ashbury to a woman accused of murdering her husband. Considered an essential portrait of American life in the '60s, Slouching Towards Bethlehem received positive attention as soon as it was published and its fandom has only grown over the decades since.

The White Album, 1979

Another collection of essays, The White Album deals with the late '60s to late '70s and the aftermath of the former. She studies the Women's Movement, shares her psychiatric report, parties with Janis Joplin and visits Linda Kasabian, who served as a lookout while members of the Manson family murdered Sharon Tate, in prison. These diverse essays see Didion capture the anxiety of the era and try to make sense of the Manson murders, the event many believe caused the '60s to end abruptly.

Where I Was From, 2003

Didion revisits the California she grew up in, specifically Sacramento County where she lived with her family, but also the state more generally. She questions the history she was taught, debunks Californian mythology and traces her ancestors and their journey moving west. She writes candidly about her upbringing, while exploring class issues with nuance. Where I Was From is one of Didion's lesser-known books, but shouldn't be.

The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005

Written in the aftermath of her husband's sudden death, The Year of Magical Thinking is an account of loss and grief - and the ways in which it can drive us to insanity. Hers was one of the first books to talk about bereavement beyond funerals, tracking the days and months that follow with her signature detachment. She writes about her own 'magical thinking' - how she can't bring herself to get rid of her husband's shoes because she thought he might need them when he returns. It sounds like pure misery, but Didion's deadpan tone impressively stops it from being so.

Blue Nights, 2011

Just a month before The Year of Magical Thinking was published, Didion's daughter, Quintana died of acute pancreatitis, aged 39. Blue Nights - a devastating account of her daughter's life and death - challenges how much tragedy one person can take. She laments over the passage of time and worries about growing older, lonelier. This is a heartbreaking tome, but solace for anyone who has ever faced the incomparable loss of losing a child.

A run down of Beyoncé's new album, 'Cowboy Carter'

The most stylish London pubs

Stylish designer homewares to buy now

'And Just Like That...' S3: what you need to know

Olivia Colman speaks out on the gender pay gap

Princess of Wales reveals cancer diagnosis

'Suits' is getting a reboot

The ultimate food and drink gift guide 2024

Update your collection with these cookbooks

Inside the 'Barbie: The World Tour' book

Marisa Abela: Becoming Amy Winehouse

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

Why Joan Didion Matters More than Ever

By Nathan Heller

Joan Didion, who turns eighty in December, has tended to be both too easily admired and too rapidly dismissed. The admiration often rises from a sense that Didion’s writing is an exercise in frank self-revelation, the disclosures of an astute cultural observer who is fragile, and yet, in the high speed and higher fashion of her life, profoundly cool. Her following among English majors past and present has become its own cliché; a lot of little magazines and literary websites fill with arch essays that want to tell you things, churn with incantatory parallels, and narrate in a self-aware first person attuned to the damning ironies of public life. Those who dismiss Didion do so on similar terms. Her writing is called out for being solipsistic, histrionic, and gratuitously portentous: what Martin Amis, in one of the most attentive criticisms, described as a “somewhat top-heavy interest in madness and stupefaction—the vanished knack of ‘making things matter.’”

Both claims have grounds, but, as this fall’s crowd-funded documentary-in-progress about Didion will surely reveal, neither is fair. What sets Didion apart is not the intimacy of her writing or her Cassandra dreams for American culture (although both are noteworthy). It’s her careful craft across a broader spectrum than most writers have available, her skill in making work that acts not only on the way you think but on the way you feel. Airplane pilots speak of “angle of attack,” and, in Didion’s best nonfiction, the angle is precise both intellectually and emotionally. Her defining quality isn’t candor or conviction but unusual, almost unrivaled, compositional control.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion’s debut essay collection, introduced readers to that style nearly half a century ago. Line by line, the book shimmers with vivifying details (“He had with him a small red book of Mao’s poems, and as he talked he squared it on the table, aligned it with the table edge first vertically and then horizontally”) and phrases so pristinely metered and charged as to be unimprovable (“This is the country in which a belief in the literal interpretation of Genesis has slipped imperceptibly into a belief in the literal interpretation of Double Indemnity, the country of the teased hair and the Capris and the girls for whom all life’s promise comes down to a waltz-length white wedding dress and the birth of a Kimberly or a Sherry or a Debbi and a Tijuana divorce and a return to hairdressers’ school”). But a lot of people can write stylishly, and many journalists might have reported such essays as well or better. (Didion has claimed a distaste for one-on-one interviews.) Her strength lay in the narrative vantage that she brought to the page, an approach that rested, as much as anything, on the way she cast herself.

This aspect of her craft goes past the caricature. At first glance, Didion’s writing appears to be filled with intimacies—the stories from her daily routine, her anxieties, her past. But how candid were these reports? The idea that Didion is a compulsively confessional writer, a frail and unhinged casualty of modern life, is largely an effect of this self-portraiture itself; look closely, and her hot outpourings cool to stone. As the critic Katie Roiphe pointed out just over a decade ago, the most striking thing about Didion’s self-disclosures was how little they disclose. Yes, she describes herself as being “quarrelsome” and “frightened” and “recalcitrant.” But this was to establish at once that the tourism piece she was writing from Hawaii was not, in fact, the usual sort of Hawaii tourism piece. Yes, Didion quotes from her own 1968 evaluation at the psychiatric clinic of St. John’s Hospital in her second collection, The White Album. Yet that does crucial work instantiating and, in some sense, officializing the general cultural anxiety she’s been trying to describe. (It also sets up a flash-cut structure for the scrapbook-style essay that follows.) She discusses her own insecurities on a return to her alma mater, Berkeley, in the sprawling hybrid essay “Pacific Distances”—but this effects a crucial turn from discussion of the post-sentimental present to the atomic-age past. Every bit of self-disclosure in Didion’s work was pruned to the minimum of necessary information and deployed as functionally as cathedral columns. Those who praise her candor are as mistaken as those who slam her solipsism. Didion’s talent is Mozartian, building simultaneously on several scales, in several registers—and always with a razor arc of finely tuned control.

The result climbs to a pitch most writing fails to reach. Didion’s nonfiction is more widely loved than her five novels (or her screenplays), in part because it’s more imaginatively seductive: Her controlled first person helps imbue the writer’s habits with the lambent glamour of a lifestyle-magazine spread. To read her is to fall into a world of cooking for Janis Joplin, reading Orwell at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel beach, zooming down the Mexican coast, and tracking New York junkies over the first days of the Christmas season . It’s to get to know a character who has precise aversions (Madison Avenue in the morning, air conditioning of any sort) and eccentrically discerning tastes (Henri Bendel jasmine soap, Payard cakes, open Corvettes, a really puzzling amount of fried chicken). Decades before the “humblebrag” became a pop-culture trope, Didion was one of its finest practitioners. (“I would be construed as the kind of loon who had maybe 300 degrees of sea view and kept all the chairs in a kind of sooty nook behind the fireplace.”)

Does that mean her quiet glamour was a trick of the pen? It depends how you define glamour. In Didion’s unconstructed moments—in an interview, say—she emerges less as a beacon of the writerly good life than as an avid craft hound, eager to tell you about her technical choices for getting the words on the page. Her fascination with her writing, as a craft, is genuine and deep. Only a person who loves the writer’s desk this much would think to describe magazine journalism, not an obviously glamorous profession, as if it were the last leg of a rock tour. Didion’s delight in her work is transfigured by that work, allowing her to cast the writing business as a high-flying, impossibly exciting job.

By Audrey Noble

By Hannah Jackson

By Madeline Fass

It was Didion’s luck, and readers’, that this controlled portrait of dissolution was perfectly pitched to echo the atomizations and upheavals of the American sixties. She rapidly became one of the era’s leading chroniclers and balladeers. But the cultural circumstances of that era and its burnt-out wake did not last, and, much to Didion’s credit, neither did her approach. In some of the lesser essays of The White Album, Didion’s writing sometimes has a played-out, schticky quality, and she may have known it: Immediately after publishing that book, she explicitly left her early style behind.

From there, in ways not always noted, she kept experimenting, changing, challenging herself. She tried using fractured, metered sentences in her fiction. She turned her nonfiction away from observational reporting and toward the argued analytical essay—an approach that culminated in her piece about the Central Park Jogger assault case, “ Sentimental Journeys .” And she reinvented her critical project. Perhaps because Didion had been adept at a particular sort of self-narration in the public eye, she could spot versions and perversions of the same in others, and increasingly she targeted writers ( Woody Allen, Bob Woodward ) who she thought were fooling right-minded people with elaborate mirages. She helped to transform the analytical mind-set of political journalism. (It is common today to speak of the “narrative” in electoral politics; Didion largely invented this way of thinking.) She became celebrated. She became reliable. Then, when she was on the cusp of her seventies, death in the family tore her life apart.

The books that narrated that crisis, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, brought Didion mainstream popularity. It’s often assumed that this was due to their heartrending subject matter—the death of Didion’s husband, John Gregory Dunne, and of her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne. Yet many people have written frank accounts of wrenching family losses; few catch the national imagination so vividly. Didion was specially equipped to write these books because, in some sense, they were works for which she’d been rehearsing all her working life. Her carefully balanced first person, apparently confessional but functionally constructed, allowed her to seem raw while still offering legibility of meaning and form. Her eye for ominous irony let her turn a fleeting crisis and sustained loss into a captivating investigative narrative. Her romanticization of the writer’s life gained full expression in the flash-cut memories woven through the books: Didion driving across the desert by night at more than a hundred miles per hour; Didion and Quintana ordering room service from a string of five-star hotels; Didion struggling “to keep myself on the correct track” in the weeks following Dunne’s death.

The speed, the tumult, the glamour—it had all been there, but never so urgently. Many writers write vexed introspection, or detail-oriented reporting, or counterintuitive cultural commentary, or lifestyle journalism. But so far only Didion has done all four in perfect synthesis, a prose that, at its best, can fire on every cylinder and work on multiple fields of the imagination at once. The ultimate standard for great writing is not clarity or intelligence or entertainment. It’s the capacity to haunt: to get under the reader’s skin and stay there even as external circumstances change. Didion’s finest books are haunting, which is why they are still discovered, admired, and pawed-over. To read her is to understand what writing, at its most exquisitely controlled, can do.

To contribute to the campaign for We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order to Live, please go to Kickstarter .

Vogue Daily

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Architectural Digest.. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

“To Be A Writer, You Must Write”: How Joan Didion Became Joan Didion

Evelyn mcdonnell on the writing process of one of america's leading literary ladies.

Joan Didion looks straight at the camera, with her fist curled in front of her mouth—as if to indicate it is through her hands that the taciturn thinker speaks. Appropriately, a manual typewriter takes up half the frame in this iconic black-and-white photo taken by Nancy Ellison in 1976.

When she was a teenager, Didion taught herself to type and to write by pecking out stories by Ernest Hemingway and Joseph Conrad on an Olivetti Lettera 22. Her goal: “To learn how the sentences worked,” she told the Paris Review . Thus began her immersion in the physical act as well as the craft of writing. Call it a form of machine learning. “I’m only myself in front of my typewriter,” Didion once told an editor at Ms. magazine.

At some point her father, in one of his random financial schemes, bought a load of Royal 200 typewriters, one of which became Didion’s accomplice. She took it with her everywhere. A typewriter is included in the carry-on items in the packing list she published in The White Album . Her idea was not to write on the plane, but while she waited in the airport, she would sit “and start typing the day’s notes.” This is one of many instructive lessons offered by Joan Didion. She must have hauled a typewriter with her in 1955, when, at age twenty, she took a train alone from Boston back to Sacramento, after a month spent in Mademoiselle ’s guest editor program. She typed multiple letters to her Mademoiselle colleague and college friend Peggy LaViolette on hotel stationery along the way. “Never being one to throw myself wholeheartedly into Adventure, I carefully got a seat alone, barricaded myself in with wicker basket, typewriter, mangled copies of old magazines and thought I could sleep all night,” she typed in one missive.

Many writers become so attached to a physical process that changing tools with the times is not easy; some never manage it. Neil Gaiman, the futurist, has said he prefers to write his novels in longhand. I still print out my writing and edit it on paper, a routine I was chuffed to hear Didion recommend to Hilton Als in an interview late in her life. Over the decades Didion graduated from notebook to manual typewriter to electric typewriter to computer, again demonstrating her openness to progress. Still, she did complain to author Maxine Hong Kingston about the transition to electric in a 1978 letter, saying that combined with moving and quitting smoking, the “reprogramming…had caused an inordinate amount of stress.” She switched to a computer in 1987 and eventually came to love the editing capabilities of word processing programs. “It did for me what geometry was supposed to have done,” she said.

Writers are prone to obsessive interest in other writers’ processes. We write because we are readers, and we read, in part, to see how others write. Didion was a bookworm. When she wasn’t sitting on the fender of her car, she was far from the snakes at the Sacramento library on a Friday night with her friend Maurice, or maybe her gal pal Nancy Kennedy (whose brother Anthony later became a Supreme Court justice and spoke at Joan’s memorial). Photos and videos document her various homes stacked floor to ceiling with books. Among the items sold at auction by her estate in 2022 were Didion’s collections of works by George Orwell, Elizabeth Hardwick, Joyce Carol Oates, and Norman Mailer.

Joan was an avid consumer of culture in general, with broad interests that did not divide art into high and low: She named one anthology after a Yeats poem, another after a Beatles album. Writer and friend Calvin Trillin called her Brentwood home “the West Coast literary consulate,” but she and Dunne largely financed it with Hollywood hack work. She loved biker films, interviewed Jim Morrison for the Saturday Evening Post and Joan Baez for the New York Times , wrote an important essay about Georgia O’Keeffe, and was close friends with writer and artist Eve Babitz ( Slow Days, Fast Company ) and writer and screenwriter Nora Ephron ( When Harry Met Sally ).

There’s a 1971 interview with Joan on YouTube, posted by the Center for Sacramento History. Some of the audio is missing, but the footage of Didion in her office in her Franklin Avenue house is, well, pure gold. She’s wearing a brown flared miniskirt and a black V-neck shirt that fastens in the back. She has tucked her shoulder-length strawberry blond hair behind her ears, as she did, and freckles dot her cheeks. She’s talking about growing up in rural environments; her Valley accent is strong. I’m not talking San Fernando Valley here; I’m talking the almost southern twang of the Central Valley, that Didion said she picked up from the many refugees from the Oklahoma dust bowl with whom she went to school. This is how Didion spoke: not with the English accent of Vanessa Redgrave, who portrayed her in the stage version of The Year of Magical Thinking , or the crisp patrician consonants of Barbara Caruso, who reads the audiobook of that text, but like a freckle-faced country girl. The camera pans across shelves full of books and books piled on the desk, lingering on volumes written by Didion and Dunne. Joan snips an article out of a newspaper in front of a cabinet of haphazardly placed manila folders, presumably full of other clippings. She’s talking about worrying herself sick about a comma being out of place while admitting she doesn’t have the same fastidious approach to her housekeeping. (This is the secret life of women writers: We can’t be good mothers, wives, daughters, writers, cooks, and housekeepers.) She sits on a black leather couch with leopard-print pillows, smoking a cigarette and reading a paperback that’s open on her lap.

“I like words and I’m very excited by seeing what can be done with words,” she says. “ Play It a s It Lays is a very short novel. I worked on it for five years but when I finished it, I thought every word was exactly right. Now I can’t even read it because words pop out at me, or sentences that I think ought to be changed.”

Didion once told a participant in a writing seminar that to get through writer’s block, you had to write one sentence, and then another, and then another.

To be a writer, you must write.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The World According to Joan Didion by Evelyn McDonnell. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Evelyn McDonnell

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Enduring Epics: Emily Wilson and Madeline Miller on Breathing New Life Into Ancient Classics

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

How Joan Didion the Writer Became Joan Didion the Legend

By Lili Anolik

In a 1969 column for Life, her first for the magazine, Joan Didion let drop that she and husband, John Gregory Dunne, were at the Royal Hawaiian hotel in Honolulu “in lieu of filing for divorce,” surely the most famous subordinate clause in the history of New Journalism, an insubordinate clause if ever there was one. The poise of it, the violence, the cool-bitch chic—a writer who could be the heroine of a Godard movie!—takes the breath away, even after all these years. Didion goes on: “I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind. I want you to understand exactly what you are getting.” I suppose I’m operating under a similar set of impulses—a mixture of candor, self-justification and self-dramatization, the dread of being misapprehended coupled with the certainty that misapprehension is inevitable (Didion’s style is catching, but not so much as her habit of thought)—when I tell you I’m scared of her.

Before I get into why, I need to clarify something I said. Or, rather, something I didn’t say and won’t say, but which I’m anxious you’re going to think I said: that Didion isn’t a brilliant writer. She is a brilliant writer—sentence for sentence, among the best this country’s ever produced. And I’m not disputing her status as cultural icon either. As large as she looms now, she’ll loom larger as time passes—I’d bet money on it. In fact, I don’t want to diminish or assault her in any way. What I do want to do is get her right. And over the past 11 years, since 2005, when she published the first of her two loss memoirs, one about Dunne, the other about Quintana, her daughter, she’s been gotten wrong. And not just wrong, egregiously wrong, wrong to the point of blasphemy. I’m talking about the canonization of Didion, Didion as St. Joan, Didion as Our Mother of Sorrows. Didion is not, let me repeat, not a holy figure, nor is she a maternal one. She’s cool-eyed and cold-blooded, and that coolness and coldness—chilling, of course, but also bracing—is the source of her fascination as much as her artistry is; the source of her glamour too, and her seductiveness, because she is seductive, deeply. What she is is a femme fatale, and irresistible. She’s our kiss of death, yet we open our mouths, kiss back.

The subject of this piece, though, is not just a who, Didion, but a what, Hollywood. So to bring them together, which is where they belong, a natural pairing, this: I think that Didion, along with Andy Warhol, her spiritual twin as well as her artistic, created L.A.—that is, modern L.A., contemporary L.A., the L.A. that is synonymous with Hollywood. And I think that Didion alone was the vehicle—or possibly the agent—of L.A.’s destruction. I think that for the city of Los Angeles, Didion is the Ángel de la Muerte.

There. I said it. Now you know why I’m scared. Who wants to get on the Ángel de la Muerte’s bad side? Not that I believe I’m going to. Because I have one last thing to add, and I don’t care how weird and screw-loose it sounds: I think she wanted me to say it.

An Ingénue, Disingenuous

The Joan Didion who moved from New York to L.A. in June of 1964 was no more Joan Didion than Norma Jeane Baker was Marilyn Monroe, or Marion Morrison was John Wayne, or, for that matter, Andrew Warhola was Andy Warhol. She was a native daughter, but only sort of. The California she grew up in—the Sacramento Valley—was closer in spirit to the Old West than to the sun-kissed, pleasure-mad movie colony. Just shy of 30, she’d recently married Dunne. Both had been working as journalists, she for Vogue, he for Time. Her first book, a novel, the traditional if not quite conventional Run River, had been published the year before. Critics hadn’t taken much notice; neither had readers. Hurt, likely a little angry too, she was ready for a new scene. Dunne was equally itchy to blow town. Plus, he had a brother in the industry, Dominick —Nick.

In his memoir Popism, Warhol wrote, “The Hollywood we were driving to that fall of ‘63 was in limbo. The Old Hollywood was finished and the New Hollywood hadn’t started yet.” Old Hollywood, of course, didn’t know it was finished. Was carrying on like it was show business as usual. And it still hadn’t wised up the following spring when the Didion-Dunnes arrived.

Nick, young though he was, was Old Hollywood. Professionally he hadn’t made it: a second-rate producer in a second-rate medium, TV. But socially he’d hit the heights. He and wife Lenny threw lavish, stylish parties, and lots of them. A month before the Didion-Dunnes showed, they’d thrown their most lavish and stylish, a black-and-white ball inspired by the Ascot scene in My Fair Lady. (That the ball—a ball!—wasn’t in color is a detail almost too on the nose. Soon the whole town would turn psychedelic, and such evenings would seem so old-fashioned as to have been in black and white even if they weren’t.) Among the splendidly monochromatic: Ronald and Nancy Reagan, David Selznick and Jennifer Jones, Billy Wilder, Loretta Young, Natalie Wood. Also present, Truman Capote, who, in a gesture either of rip-off or homage, would stage his own black-and-white ball in New York. Nick’s invitation would get lost in the mail.

In later years, Didion and Dunne would play a double game with Hollywood: they were participants who were also onlookers; supported by the industry but not owned by it; in the thick of it and above the fray. They seemed much less ambivalent in their early years. In their early years, they wanted in. A line invoked by both so often you know they must have believed it gospel is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon: “We don’t go for strangers in Hollywood.” How lucky for them then that they were the brother and sister-in-law of Nick, and thus part of the Hollywood family, if poor relations. And, as poor relations, they were given castoffs: clothes, Natalie Wood’s (for Didion); houses, too. They rented Sara Mankiewicz’s, fully furnished, though Mankiewicz did pack up the Oscar won by her late husband, Herman, for writing Citizen Kane.