Word-of-mouth in business-to-business marketing: a systematic review and future research directions

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing

ISSN : 0885-8624

Article publication date: 10 January 2023

Issue publication date: 18 December 2023

The purpose of this study is to review and analyze the status of word-of-mouth (WOM) research in the business-to-business (B2B) context and discuss and identify new possible future directions.

Design/methodology/approach

A systematic review was conducted and 36 articles on B2B WOM were collected to evaluate the current state of the literature and clarify possible future research directions.

This thematic analysis categorize these articles into three themes: WOM generation, WOM usage and reference marketing. Under each theme, the authors reveal research findings unique to B2B research and different from business-to-consumer (B2C) WOM research. This study identifies several research questions that should be addressed by future research.

Originality/value

Both academic researchers and business practitioners recognize that WOM plays an essential role in B2B marketing. However, no review paper focuses on WOM in the B2B context. Findings in the B2C WOM literature suggest that WOM substantially influences firms’ performance, but that managers cannot simply attempt to extrapolate B2C findings to the B2B arena. By synthesizing and assessing prior research on WOM in the B2B context, this study contributes to a better understanding of the B2B WOM phenomenon and facilitates future research on this topic.

- Business-to-business marketing

- Recommendation

- Systematic review

- Word-of-mouth

Ishii, R. and Kikumori, M. (2023), "Word-of-mouth in business-to-business marketing: a systematic review and future research directions", Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 38 No. 13, pp. 45-62. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2022-0099

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Ryuta Ishii and Mai Kikumori.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence maybe seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

1. Introduction

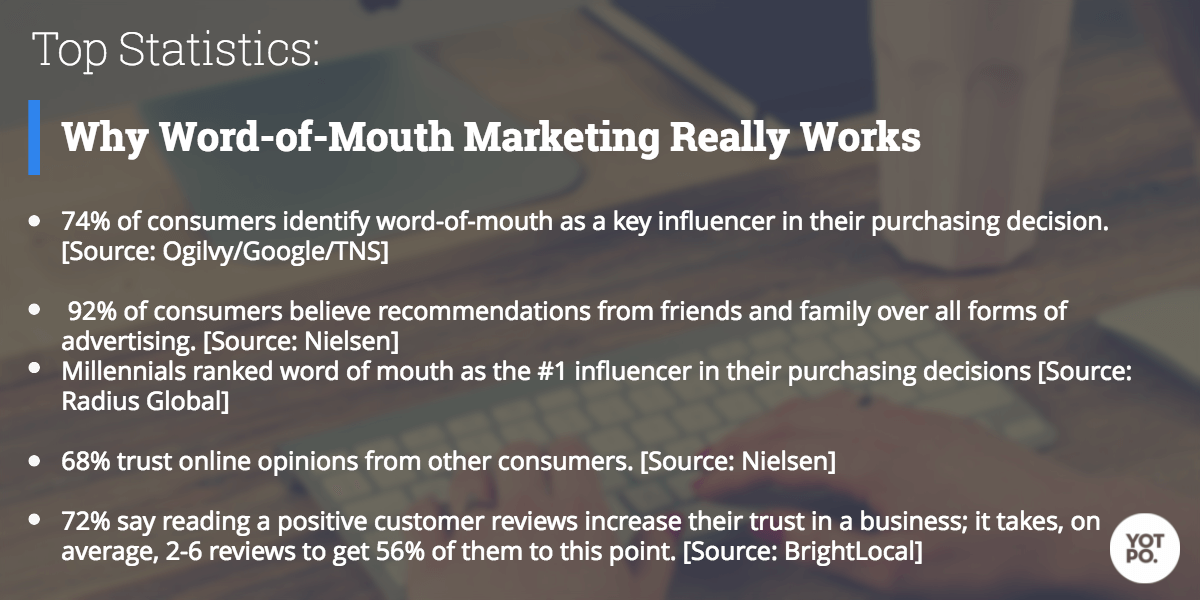

In the field of business-to-consumer (B2C) marketing, it is widely accepted that word-of-mouth (WOM) has a meaningful influence on consumers’ buying decisions. Whether face-to-face or electronic, WOM has a more substantial impact on sales than other elements of the marketing mix, such as advertising and personal selling ( Kim and Hanssens, 2017 ; You et al. , 2015 ). The volume of consumer reviews on a particular product improves product awareness and drives consumers to purchase it ( Babić Rosario et al. , 2016 ; Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006 ; Zhu and Zhang, 2010 ). Both positive and negative WOM can improve product evaluations and purchase intentions ( Allard et al. , 2020 ; Berger et al. , 2010 ). Furthermore, from a long-term perspective, consumers acquired through WOM bring about twice as much value to a company as other consumers ( Villanueva et al. , 2008 ).

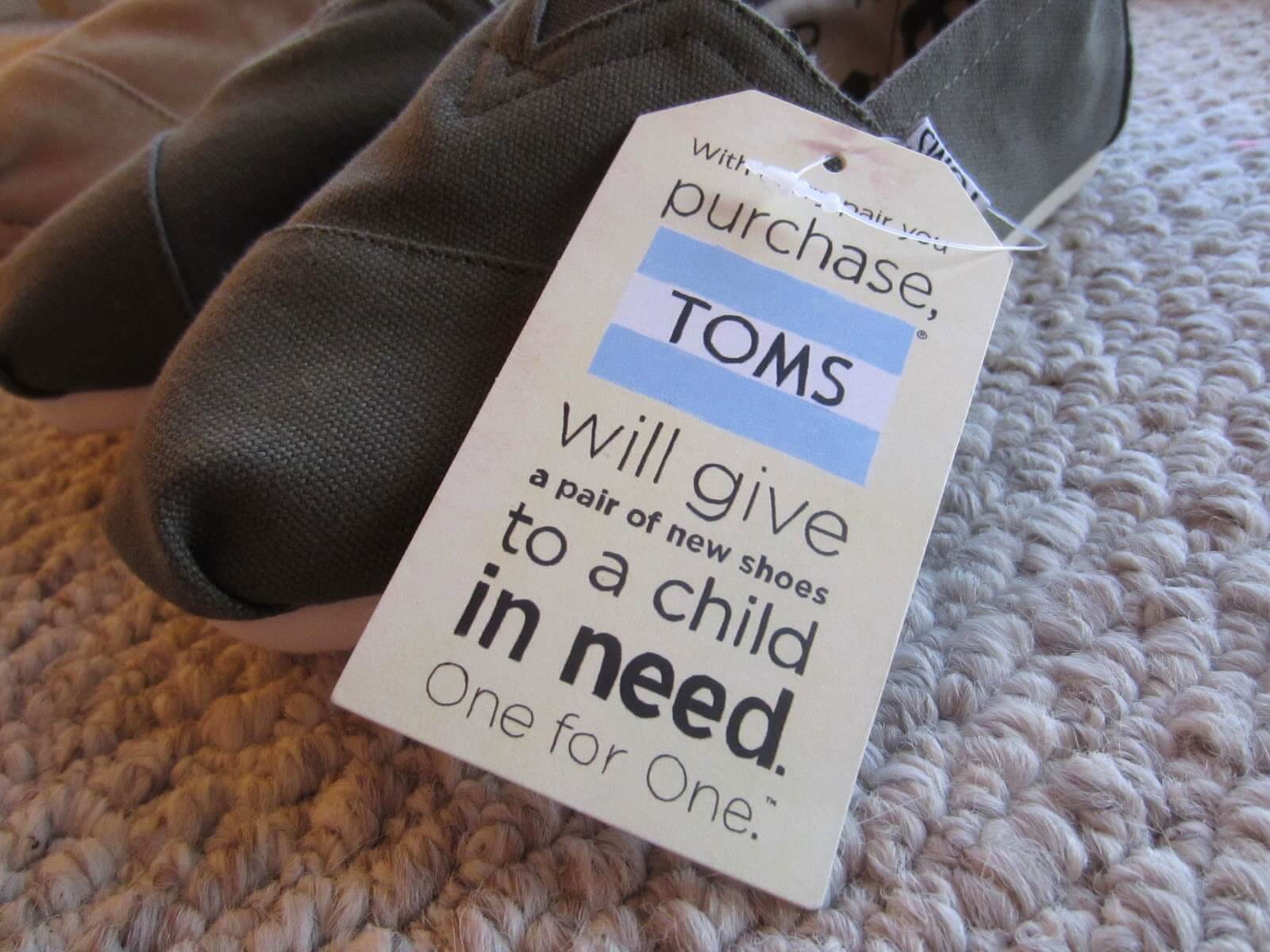

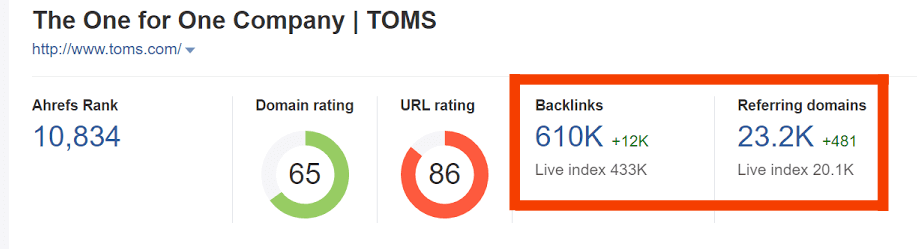

WOM has a considerable influence on purchasing decisions, not only in B2C but in business-to-business (B2B) marketing as well ( Money, 2004 ). For example, purchasing managers in buying firms often obtain WOM information from their internal coworkers (e.g. salespersons and other purchasing managers) or external partners (e.g. exchange partners and business friends) when searching for a new supplier or evaluating a novel industrial product ( Money et al. , 1998 ; Tóth et al. , 2020 ). B2B buyers have begun forming online communities and use electronic WOM from other buyers in the community ( Steward et al. , 2018 ). Given that WOM plays a vital role in the purchasing decisions of buyer firms, seller firms proactively use it to promote their products and services. For example, they ask their existing customers to recommend their products to potential customers ( Hada et al. , 2013 ; Hada et al. , 2014 ) and post customer reviews of their products on their websites as case studies ( Jaakkola and Aarikka-Stenroos, 2019 ; Jalkala and Salminen, 2009 ). This practice, referred to as reference marketing or referral marketing, is widely used in business markets.

Therefore, the topic of WOM has attracted the attention of marketing managers and academic researchers because of its key influence on both B2C and B2B marketing. Indeed, to date, many reviews have been published on WOM ( Babić Rosario et al. , 2020 ; Berger, 2014 ; de Matos and Vargas Rossi, 2008 ; Donthu et al. , 2021 ; King et al. , 2014 ). However, all these reviews focus on WOM in the B2C context and not in the B2B context. Findings in the B2C WOM literature suggest that WOM substantially influences firms’ performance, but that managers cannot simply attempt to extrapolate B2C findings to the B2B arena. Thus, it is essential to synthesize research findings and identify future research directions on the role of WOM in B2B marketing.

Therefore, the purpose of our study is to review and analyze the status of WOM research in the B2B context, synthesize research findings to date and identify possible future directions using a systematic review method. This method differs from a traditional narrative review in that it removes the subjective bias of the researcher. It ensures exhaustive and comprehensive literature searches through a replicable, scientific and transparent process.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We first define and clarify the concept of WOM along with relevant concepts, such as referrals, recommendations and references in the Section 2. Next, we describe the systematic review method and the data collection procedure in the Section 3. Subsequently, we conduct descriptive and thematic analyses of the reviewed articles in the Sections 4 and 5. Finally, we present managerial implications, discuss our analysis, and show possible directions for future research in the Sections 6 and 7.

2. Word-of-mouth in the business-to-business context

WOM is defined as:

An oral or written communication process between a sender and an individual or group of receivers, regardless of whether they share the same social network, with the purpose of sharing and acquiring information on an informal basis ( Barreto, 2014 , p. 647).

Marketing scholars have used various terms to refer to the WOM phenomenon in the B2B context, such as WOM ( Faroughian et al. , 2012 ; Kim, 2014 ), referral ( Hartmann and de Grahl, 2011 ; Wallenburg, 2009 ) and recommendation ( Olaru et al. , 2008 ). Several authors have even used a combination of these terms, such as WOM referrals ( Money et al. , 1998 ; Roth et al. , 2004 ) and WOM recommendation ( Chenet et al. , 2010 ). However, these terms are often used interchangeably in the B2B WOM literature ( Aarikka-Stenroos and Sakari Makkonen, 2014 ; Tóth et al. , 2020 ). Thus, we only use the term “WOM” here. However, we need to draw a clear line between the terms WOM and reference. As discussed earlier, in B2B marketing, selling firms often use customers’ WOM as a marketing and sales tool. Such seller-initiated active utilization of customers’ WOM is referred to as reference marketing. Although reference marketing is included in the WOM phenomenon, B2B marketing scholars distinguish between “WOM,” which is informal communication among customers wherein the seller does not intervene, and “reference,” which is communication using WOM in which the seller intervenes.

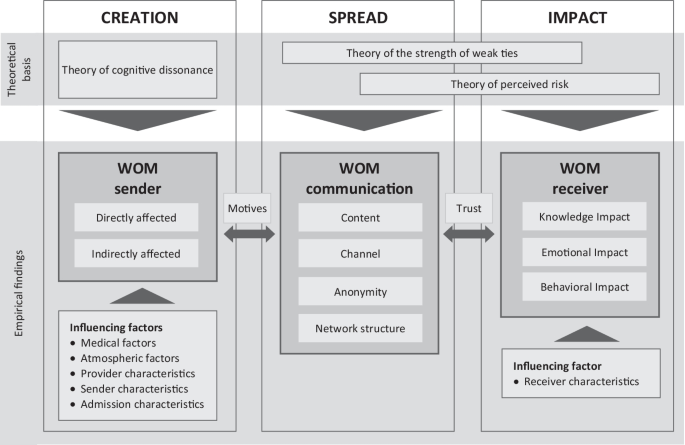

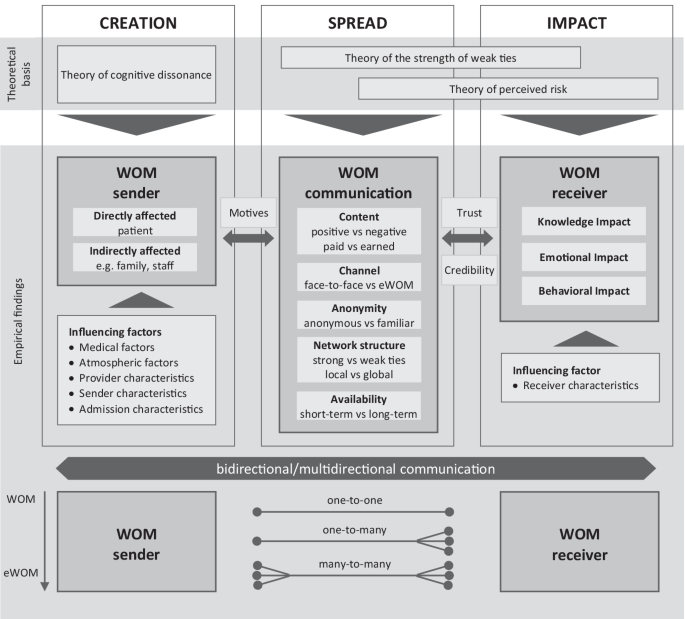

Based on the above discussion, the WOM phenomenon in B2B marketing can be classified into two categories: “pure WOM” and “reference marketing.” As shown in Figure 1 , “pure WOM” is the process where a sender (e.g. an existing buyer or a salesperson) sends WOM to a receiver (e.g. a potential customer or an internal colleague). Suppliers do not directly intervene in this process, but they can be indirectly involved by incentivizing a sender to generate WOM about themselves or their offerings. “Reference marketing” is the process where a supplier uses WOM from a sender (i.e. reference customer) to provide information to a receiver (e.g. a potential customer). Suppliers can intervene in this process by choosing the sender as a reference customer.

WOM sender;

WOM receiver; and

A WOM sender (e.g. an existing buyer or reference customer) sends positive or negative WOM to internal colleagues or external buyers or provides experiential information related to suppliers. A WOM receiver (i.e. a potential customer) receives and processes WOM information from the senders and uses it for purchase-related decision-making. A supplier encourages existing customers to send WOM to prospective customers or to use WOM information from reference customers as a marketing tool. In the next section, we conduct a systematic review while considering these terminologies and classifications.

3. Methodology

We adopted the systematic review method to analyze the status quo of B2B WOM research. The advantages of this method are described in recent studies published in the Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing ( Chawla et al. , 2020 ; Minerbo and Brito, 2021 ; Yaghtin et al. , 2021 ) and others ( Hulland and Houston, 2020 ; Transfield et al. , 2003 ). We searched and reviewed articles based on the procedure established by Transfield et al. (2003) . First, we developed a review protocol, which included a review question, the focus of this research and the data collection strategy for relevant articles. We searched, collected and assessed the quality and relevance of the identified articles based on this protocol. We then conducted both descriptive and thematic analyses to reveal specific and detailed information on reviewed articles and summarized the key findings of the literature. Finally, we synthesized the findings into an integrated conceptual framework to investigate the WOM phenomenon in the B2B context and identified possible directions for future research. In this section, we describe the process of data collection and synthesis.

3.1 Review question

A systematic review is driven by a review question from which search strings for scientific database searches are defined, criteria for inclusion or exclusion are specified, and an overall process for collecting relevant literature is established. As stated earlier, we aim to synthesize research findings and identify future research directions on the role of WOM in B2B marketing. Therefore, we set two review questions: (1) “What do we know about WOM in B2B marketing?” and (2) “What do we not know about WOM in B2B marketing?”

3.2 Database and search terms

EBSCO Business Source Complete;

Science Direct; and

These databases have a worldwide reputation as reliable platforms; cover most of the published articles on business and marketing; and allow us to search for articles using the title, abstract and keywords.

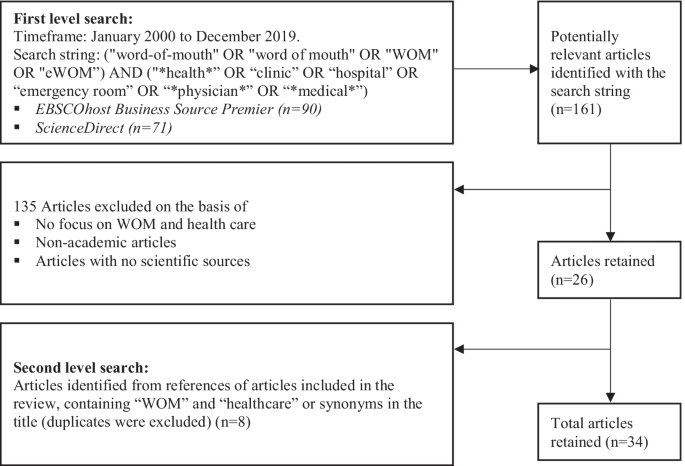

Given that the review questions are about the findings and research gaps in B2B WOM, it is necessary to choose articles focusing on the context of business markets or B2B marketing. Therefore, we set two groups of keywords: the first group focused on WOM, including four keywords: “WOM,” “referral,” “customer reference” and “customer review”; and the second group was about B2B, also including four keywords: “business-to-business,” “industrial markets,” “industrial marketing” and “supplier.” We used the three databases to search for published articles containing WOM-related keywords in the first group and B2B-related keywords in the second group, either in the title, abstract or keywords. We conducted our initial search in January 2021 with no publication time limit. As shown in Figure 2 , 141 articles were obtained as the set of initial samples: 71 from EBSCO Business Source Complete, 32 from Science Direct and 38 from Emerald. After removing duplicate articles, 111 articles remained.

3.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To ensure an unbiased selection of literature for our review, we established clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. We focused on peer-reviewed, full-text accessible, original research articles published in English. Therefore, non-peer-reviewed business articles and editorials were excluded. We included journals from two widely recognized international journal lists: the Academic Journal Guide (Chartered Association of Business Schools) and the Journal Quality List (Australian Business Deans Council). We included articles that address the WOM phenomenon as the explained object (e.g. studies that treat WOM as the dependent variable in quantitative studies) and articles that use WOM to explain a specific phenomenon (e.g. quantitative studies that have WOM as an independent variable in quantitative studies). We excluded articles that focused on the B2C context rather than B2B. We decided to include articles that considered WOM in both B2B and B2C contexts (e.g. comparing WOM effects in B2B and B2C contexts). We also decided to exclude articles that discussed WOM in general, since, at least in the academic field, WOM refers to B2C WOM, not B2B WOM. A key term associated with WOM is social media. Although communication among customers on social media can be viewed as a WOM phenomenon, the use of social media by firms is difficult to capture as a WOM phenomenon. Hence, studies focusing on WOM in social media were included in the review, whereas studies on social media usage were excluded.

3.4 Selection of relevant articles

Two researchers reviewed 111 literature summaries. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, they screened the articles relevant to our review questions. However, for several references, it was difficult to determine whether to include them in our review based solely on reading the abstracts. In those cases, we manually read the full text to obtain the information needed to decide. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved through consultation.

Most of the 111 references focused on WOM in a B2C context and the use of social media by B2B firms. Based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, these references were excluded. Similarly, applying that criterion, editorial and economic articles were also excluded. Among the 111 articles, many focused on WOM in the B2C context and social media in the B2B context. Because the latter studies focused on the usage, design and management of social media by B2B companies, they were also removed, and 33 articles were extracted. Finally, by examining the citations of these 33 articles, 3 additional important articles were identified. Occasionally, review articles that focused on WOM in general were also cited; however, we did not add them as key references because the review articles implicitly focused on the B2C context (e.g. individual consumer reviews, informal communication among consumers). Consequently, there were 36 studies in total.

3.5 Extraction, analysis and synthesis

After determining the literature to be included in the review, the last step in the data collection process was to create a data extraction form. To extract the data, we used a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This sheet contained the following information for the collected literature: title, authors, publication journal, year of publication, article type, sample size, industry context, country, major research findings, type of WOM, etc. To reduce subjective bias as much as possible, each author reviewed all 36 references and completed the required fields in the spreadsheet. When disagreements arose among the authors regarding coding and classification, decisions were made through discussion. The final spreadsheet was helpful in conducting the descriptive and thematic analysis that followed.

4. Descriptive analysis

Literature on WOM in B2B marketing emerged in the 1970s, when academic scholars paid great attention to industrial buying behaviors and investigated the difference between B2B and B2C marketing strategies ( Sheth, 1973 ; Webster and Wind, 1972 ). The pioneering works of Martilla (1971) and Webster (1970) revealed that WOM is generated either by internal colleagues (i.e. intrafirm WOM) or external firms (i.e. interfirm WOM) and is an essential factor that influences business organizations’ decision-making processes. For almost three decades after these works, very little research focused on WOM in B2B marketing. Since the 2000s, however, more than 30 WOM-related articles have been published. Specifically, 2 articles (5.6%) were published between 2001 and 2005, 9 (25%) between 2006 and 2010, 11 (30.6%) between 2011 and 2015 and 11 (30.6%) between 2016 and 2020. There were at least three causes of the widespread recognition among researchers and the gradual increase in the number of WOM-related articles. First, online review websites have increased in B2B marketing, and WOM communication among buyers has influenced purchasing decisions. Second, in the context of B2B marketing, the use of social networking services has become commonplace, and communication about products and services has become active in buyer communities and professional networks. Third, the spread of the internet has increased the need for companies to establish their own websites and to post customer feedback as a form of testimonials on those websites.

As shown in Table 1 , the 36 articles included in this review were published in 15 separate journals. Of the 15 journals, 11 were rated three and above in the Academic Journal Guide (AJG; Chartered Association of Business School, 2021 ). According to the ABDC Journal Quality List (JQL), eight were A* journals, five were A and two were B ( Australian Business Deans Council, 2019 ). In the Scimago Journal Rank indicator, most journals (80%) belonged to the Q1 category. These results indicate that the articles included in this review are of good quality and that the editors and reviewers of top-level journals are paying attention to this topic. Regarding the number of articles, approximately half the articles (44%) were published in the two leading journals specializing in B2B marketing: Industrial Marketing Management (31%, n = 11) and Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing (14%, n = 5). This suggests that B2B marketing scholars have contributed considerably to our understanding of the WOM phenomenon in the B2B context. Other journals that feature in our study and are of international repute include Journal of Marketing (6%, n = 2), Journal of Marketing Research (6%, n = 2), European Journal of Marketing (8%, n = 3), Journal of Supply Chain Management (8%, n = 3) and Journal of Services Marketing (6%, n = 2). Other articles were also published in internationally recognized journals in the field of marketing and business, such as the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science and Journal of Business Research . Most of these journals are general journals on marketing and business. The appearance of articles on B2B WOM in such journals suggests that various marketing researchers are interested in this topic.

Figure 3 shows the trend over time and current proportion of each methodology used by the selected articles. According to the present proportion of methodologies used, of the 36 articles, most were empirical studies (94%, n = 34), with the most common method being quantitative analyses with data collection by mail or an online survey (47%, n = 17). This trend is similar to that of other topics in B2B marketing. The qualitative interview method (25%, n = 9) was also often used by the selected articles. Compared to quantitative methods, qualitative methods are used in the early stages of a particular research field because they are better at examining new and complex phenomena in an exploratory manner ( Granot et al. , 2012 ; Woodside and Wilson, 2003 ). Indeed, several articles in our review stated that they use qualitative methods because there are few studies on B2B WOM, and there is an insufficient description of the phenomenon and elaboration of the concepts ( Jaakkola and Aarikka-Stenroos, 2019 ; Jalkala and Salminen, 2010 ). Therefore, a relatively large proportion of qualitative studies in the selected articles suggests that the study on B2B WOM is in its early stages.

No literature reviews (e.g. systematic reviews or meta-analyses) were found. Notably, the time-series trends indicate a gradual increase in the number of experimental methods in recent years. This is because B2B marketing is beginning to pay more attention to experimental methods: the use of experimental stimuli in a B2B context is difficult because the purchase of B2B products/services involves multiple persons, and the buying process is a long one. Hence, experimental methods tend to be shunned in B2B marketing research. However, the experimental method is a valuable gold standard for analyzing causal relationships ( Hada, 2021 ). In fact, experimentation is used extensively in B2C WOM research.

Figure 4 shows the loci of the empirical studies analyzed in this review. Of the 34 empirical studies, 25 explicitly indicated the country where data were collected. The two major regions were Europe (32%, n = 8, three studies in the UK, two in Germany, two in a particular European country, and one in Finland) and the USA (28%, n = 7). Four studies were conducted in China and one each in Australia, Canada and India. Moreover, three studies collected data from multiple countries (i.e. USA and Japan) to compare the organizational buying behaviors. Overall, most extant literature has focused on organizational behaviors of developed Western countries. Such overall trends indicate that researchers in the USA and Western Europe are the main contributors to research on B2B WOM. Additionally, we should be cautious about applying such research findings to WOM behaviors in other regions such as Asia and Africa.

Table 2 shows the industries that the empirical studies in this review considered as the research context. Overall, most studies focused on B2B services, which, unlike tangible industrial products, are characterized by their intangible and variable nature, making it difficult to assess their quality before buying or experiencing them. Therefore, WOM information plays a crucial role in the evaluation and purchase of B2B services. Previous studies ( Faroughian et al. , 2012 ; Hada et al. , 2014 ; Jalkala and Salminen, 2009 ; Money, 2004 ) have often focused on three services: “IT and software procurement,” “logistics and transportation” and “financial service.” In the information technology (IT) and logistics service industries, it has been found that sellers and buyers actively use WOM, the latter in making purchasing decisions. Several studies have focused on reference marketing in the context of IT procurement or logistics services. This suggests that in the IT and logistics industries, selling firms actively use WOM information as a marketing tool, whereas buying firms rely on it to make purchasing decisions. Further, start-up companies often face purchasing decisions regarding logistics and financial services ( Money et al. , 1998 ; Roth et al. , 2004 ). Other services that frequently appear in empirical studies are telephone and food services, which were investigated in two studies. Other services include printing, advertising and packaging. Some studies have focused on the transactions of tangible industrial goods rather than services. Specifically, they have examined the role of WOM in the purchasing decisions of pharmaceuticals, electronic machinery and processing equipment.

5. Thematic analysis

WOM generation;

WOM usage; and

reference marketing.

Table 3 presents an overview of research findings from the reviewed articles. This section offers the contributions and discusses the main research findings for each theme.

5.1 Theme I: word-of-mouth generation

The first theme is WOM generation and focuses on the sender or source of WOM; 16 (44%) of the 36 studies in this review come under this theme, where the research question is, “Why do customer firms send positive or negative WOM messages?” These studies investigate the antecedents of WOM communication. This theme has two characteristics: first, prior research on this theme has often treated positive WOM messages, such as recommendations and referrals, as positive outcome indicators, along with repurchase intention, satisfaction, loyalty and relationship continuity. By stating that “a widely studied outcome variable within the relationship marketing literature is word-of-mouth,” Brock and Yu Zhou (2012 , p. 372) emphasized the importance of WOM as a performance indicator in B2B research. Second, 13 (81%) of the 16 studies used a quantitative survey as the empirical method. Most of these survey studies focused on B2B services, such as logistics, IT, and finance. This suggests that B2B service marketers emphasize WOM generation.

Prior research on B2C marketing identifies satisfaction, loyalty, quality, perceived value and trust as essential antecedents of WOM generation ( de Matos and Vargas Rossi, 2008 ). WOM studies in B2B marketing extend these research findings of B2C WOM by identifying moderating variables specific to B2B marketing. Olaru et al. (2008) showed that the effect of service value on positive WOM generation is moderated by organization type (government versus private firm) and contract length (long versus short). Anaza and Rutherford (2014) considered both individual and organizational levels of the interorganizational relationship between seller and buyer. They found that positive WOM is created by loyalty to individual salespersons and satisfaction with seller firms.

Studies under this theme have identified the antecedents of WOM generation, such as firm strategy, organizational capabilities, strategic orientation and interfirm relationships, which have not been assessed in WOM research in the B2C context. Hartmann and de Grahl (2011) focused on the concept of organizational flexibility and indicated that logistics service providers can promote customer referrals by responding flexibly to customers’ needs and changes in the environment. Mo et al. (2020) found that an increase of out-of-the-channel-loop perception, which means a channel member’s perception of exclusion from a supplier’s distribution channel networks, decreases positive WOM generation.

Prior research has also investigated the generation of negative WOM messages when B2B service failure occurs. Wang and Huff (2007) identified the conditions under which buyers generate negative WOM when a seller violates the buyer’s trust by failing to meet the buyer’s confident expectations. Specifically, they showed that buyers in the early stages of trust development and/or those who perceive a high likelihood of repeated violation respond negatively and sensitively to a violation of trust.

Overall, prior studies have shown that firm characteristics and interfirm factors generate WOM or moderate the effects of WOM. However, there has been no attempt to examine who generates WOM within a firm or what happens to buyer firms and purchasing managers as a result of WOM generation. These are research questions to be addressed in the future, and we discuss them in detail in the next section.

5.2 Theme II: word-of-mouth usage

Research under the theme of WOM usage has addressed the following questions: What types of WOM messages do customer firms use? Why do customer firms use WOM messages as a source of information for purchase decision-making? What are the consequences of WOM usage? These questions are rarely addressed in B2C WOM research and are specific to the field of B2B marketing.

As shown in Table 4 , WOM information used by customer firms is classified into four types based on the sender–receiver relationship (within-firm versus between-firm) and communication mode (face-to-face versus internet). The first type is the intrafirm offline WOM . Martilla (1971) conducted exploratory interviews with 66 managers in the paper industry and found that there are opinion leaders in each company who have a considerable influence on the purchasing decisions for industrial products through WOM communication within the company. The second type is the intrafirm online WOM . Steward et al. (2018) showed that sellers’ scorecards (performance appraisal systems) available on company intranets can be regarded as WOM information within a company and that they influence purchasing decisions in B2B markets. The third is interfirm offline WOM , which has been the focus of many studies. Money et al. (1998) and Roth et al. (2004) found that start-up firms often refer to WOM information from relatives, friends, and business acquaintances when they make purchase decisions for B2B services such as logistics, advertising and finance. Hada et al. (2014) also focused on the face-to-face WOM prompted by suppliers (i.e. face-to-face reference) in B2B markets and showed that B2B marketers often use such reference information from other companies in the purchase process. Fourth is interfirm online WOM . According to Steward et al. (2018) , professional B2B buyers have formed online communities in recent years and refer to other buyers’ reviews of B2B products and services. Many studies in this review examine online reference marketing, where sellers post buyers’ WOM reviews on their own website and use it as a marketing tool ( Jalkala and Salminen, 2009 ; Terho and Jalkala, 2017 ). They show that online WOM from other companies (i.e. interfirm online WOM) is often used in B2B marketing.

Previous studies also address the research questions: Why do customer firms use WOM messages as sources of information for purchase decision-making? What are the consequences of WOM usage? These studies investigate the antecedents and consequences of WOM usage. The former focuses mainly on firm characteristics as a factor influencing WOM usage. For example, Money et al. (1998) conducted exploratory interviews with purchasing managers of 48 start-up firms in Japan and the USA and showed that organizational culture plays a vital role in selecting B2B service providers. Specifically, Japanese companies are more likely to use WOM information sources than US companies because Japanese companies have a strong culture of collectivism and uncertainty avoidance. In addition, Yang et al. (2017) found that firms performing above expectations tend to choose suppliers based on partners’ referrals because they are more inclined to maintain the status quo and are less willing to take risks.

Existing studies focusing on the consequences of WOM usage investigate the effects of WOM usage and WOM type on outcome variables such as satisfaction and relationship continuity. In thesecases, the supplier is selected through WOM information. For example, Money (2004) indicated that buyer firms’ switching behaviors are influenced by the use of WOM and tie strength between the sender and receiver (buyer firms). Specifically, firms that use WOM information to select B2B service providers are less likely to switch to existing suppliers than those that do not. In addition, Japanese firms in Japan do not tend to change service providers when they consult WOM sources with high likability and/or expertise. Furthermore, Kim (2014) found that the higher the expertise of the WOM source and the more similar the buyer and the WOM source, the more likely that the buyer will establish a strong relationship and continue business with a supplier.

In summary, prior research has shown that using WOM to select business partners allows firms to form strong relationships with them and reduce the likelihood of switching to other firms in the future. In addition, prior research has shown that firms use WOM to reduce uncertainty and maintain their current favorable performance. However, there is insufficient empirical evidence on the relationship between WOM usage and firm performance. Insights are needed on how firms should use different types of WOM and under what conditions WOM usage is effective.

5.3 Theme III: reference marketing

Studies on reference marketing have addressed the question of how a B2B firm implements reference marketing. What are the consequences of this? Compared to Themes I and II, this theme is more recent in B2B marketing research. Approximately 70% of the studies under this theme have been published within the past 10 years. Since almost half (44.4%) of these studies use qualitative interviews, this topic is characterized by being in its early stages and is oriented toward theory building.

the supplier (i.e. selling firm);

reference customer (i.e. WOM source, WOM sender); and

potential customer (i.e. WOM receiver).

Figure 5 shows how the three parties are involved, depending on whether the communication mode is online (internet) or offline (face-to-face). In offline reference marketing, the supplier first asks the reference customer to spread positive WOM about the products or the supplier. The reference customer then shares their experience with the supplier’s brand with potential customers ( Hada et al. , 2014 ; Jaakkola and Aarikka-Stenroos, 2019 ). In the case of online reference marketing, the supplier posts the reference customer’s reviews on their website as success stories or testimonials. The website is then used to encourage potential customers to initiate a business relationship with the supplier and buy the brand ( Jalkala and Salminen, 2010 ; Tóth et al. , 2020 ).

supplier-focused;

reference customer-focused; and

potential customer-focused research.

Supplier-focused research investigates how B2B firms implement reference marketing and whether such practices lead to high firm performance. Jalkala and Salminen (2010) conducted exploratory interviews with 38 companies in the information and communication industry and showed that B2B firms use WOM (online references) collected from reference customers in two ways: the external use of customer references to promote sales and enhance the firm’s reputation and the internal use of customer references for employee training and customer understanding. Terho and Jalkala (2017) , using quantitative survey data collected from 220 B2B firms, found that both external and internal uses of customer references lead to high sales performance (e.g. new customer acquisition and large market share). Reference customer-focused research is limited: Jaakkola and Aarikka-Stenroos (2019) conducted interviews with 76 B2B firms in the knowledge-intensive services industry and examined the value of reference marketing to the supplier, reference customer and potential customer. They showed that reference customers try to strengthen their business relationships with suppliers by sharing their experiences with potential customers, but they also experience the risk of leaking information that could potentially harm the reference. Potential customer-focused research has been conducted to understand B2B customer behaviors. Hada et al. (2014) examined how reference valence and source credibility affect potential customers’ evaluation of suppliers. Through multiple experiments, they found that the effect of a positive reference is more meaningful when prospective buyers and source firms (i.e. reference customers) have previous business experience. They also showed that source credibility plays an important role only when the reputation of reference customers is high.

In sum, prior research has investigated the effectiveness of reference marketing from the perspective of three parties: suppliers, reference customers and potential customers. Although these studies have advanced our understanding of reference marketing, further work is needed to examine its impact on firm performance. New insights are required on what references firms should use and how to encourage their own salespeople to use references.

6. Managerial implications

By identifying three themes and summarizing the findings in each theme, we offer some useful suggestions for business managers. Specifically, we provide practical insights to sales managers of firms who sell goods/services and purchasing managers who buy them, respectively.

Sales managers of suppliers or selling firms should refer to research findings on decision-making regarding how existing customers communicate WOM (Theme I), how WOM is evaluated (Theme 2), and how reference customers’ WOM is leveraged (Theme 3). For example, the following suggestions can be drawn from prior literature. According to previous research on WOM generation ( Anaza and Rutherford, 2014 ), the loyalty of the purchasing manager toward the sales manager triggers positive WOM. Hence, salespeople should treat loyal customers with care, not only in terms of their large direct contribution to sales, but also in terms of their indirect contribution to sales through sales promotions to other companies. Research findings on WOM usage ( Yang et al. , 2017 ) indicate that in a highly competitive environment, high-performing firms are more likely to select business partners based on WOM; therefore, firms in a highly commoditized and highly competitive environment should place importance on existing customers as WOM generators. Furthermore, according to the research findings of reference marketing in Theme 3 ( Terho and Jalkala, 2017 ), firms should use customers’ opinions and success stories not only as a promotional tool but also as a learning material for sales representatives.

Purchasing managers in buyer firms should refer to research findings on decision-making regarding what benefits firms can obtain from sending WOM to other firms (Themes 1 and 3) and when firms should use WOM as a source of information (Theme 2). Jaakkola and Aarikka-Stenroos (2019) show that the dissemination of WOM as a customer reference allow firms not only to build close business relationships with supplier firms, but also to form strong relationships with potential customers. Kim (2014) reveals that using the WOM of other firms that have high expertise and are similar to one’s own firm to select business partners reduces the likelihood of switching business partners; thus, WOM from such firms should be considered important in making purchasing decisions.

Throughout this review, we indicated that WOM has a considerable influence on purchasing decisions in the B2B context. Although some B2B marketing managers may underestimate the role of WOM, online review websites for B2B products/services are widespread and online communities among purchasing managers are formed. Considering these trends, it is anticipated that WOM is more and more likely to drive purchasing decisions in the B2B context, just as WOM is a powerful influence in B2C marketing. Therefore, B2B marketing managers are required to use WOM as a strategic tool for firm success.

7. Discussion and future research directions

We conducted a systematic literature review of 36 articles to determine the current state of research on WOM in the B2B context. The following section discusses the future research directions for WOM research within all the three themes; that is, WOM generation, WOM usage and reference marketing. For each theme, we identify several research questions that should be addressed in future works. In addition to the three themes above, we identify promising research directions in two emerging themes not addressed by previous studies: collecting and managing WOM information about the supplier’s brand.

7.1 Word-of-mouth generation

Although B2B WOM research has examined the antecedents of WOM generation, it has only considered WOM generation as a positive outcome, along with other outcome indicators such as satisfaction and loyalty. Therefore, future research needs to address why buyers talk about selling firms and seller brands. Buyer firms probably send WOM messages to others to maintain their reputation in the market and to develop trust with their suppliers. It would be useful to assess such relationship drivers.

It is also helpful to focus on the WOM generation behaviors of individual purchasing managers in buyer firms. Some purchasing managers frequently send WOM to other buyers, while others generate none. Based on the findings of WOM research in the B2C context ( Berger, 2014 ; Donthu et al. , 2021 ; King et al. , 2014 ), psychological propensities such as altruism, self-enhancement and product involvement motivate buyers to send WOM. Additionally, purchasing managers with a vast informal network of contacts outside their firms are likely to generate WOM messages to maintain their networks. Therefore, it is essential to conduct qualitative and quantitative studies to examine the WOM communication behaviors of buyer firms.

To our surprise, no study has focused on the consequences of WOM generation. To deepen our understanding of WOM generation behaviors, it is necessary to investigate not only its antecedents but also its consequences. Future research should address the following research question: What are the consequences of WOM generation? For example, considering individual buyers, those who often send WOM to other buyers may obtain useful WOM information from other buyers in return. Consequently, the buyer can have a high level of knowledge about the market and its competitors. Providing such empirical evidence on the behaviors of buyer organizations and purchasing managers would contribute to the advancement of WOM research in the B2B context.

It is necessary to conduct qualitative and quantitative studies on the role of a supplier in generating WOM about their products or services. What kind of behavior is adopted by the suppliers in the first place? Although academic scholars, mainly in northern Europe, have assessed the online reference marketing activities of suppliers, other WOM activities have not been investigated. For example, how do suppliers make efforts to generate WOM about their offerings? What kind of firms focus on activities to induce WOM communication about their products? How supplier–sender relationships drive WOM generation? Future research should address these questions.

7.2 Word-of-mouth usage

Many studies have focused on factors that influence WOM usage behaviors. These studies address the question of when and why buyer firms use WOM information. While existing research has shown that organizational culture and performance affect WOM usage behaviors, there are many unanswered questions. For example, what product characteristics drive B2B firms to use WOM information? It is possible that B2B firms are more likely to use WOM when purchasing complex or innovative products. Future research should provide further empirical evidence on this topic.

B2B firms use various types of information sources: online and offline WOM, customer references, advertisements, salespeople and catalogs. Prior research has begun to address the use of WOM combined with other information sources ( Steward et al. , 2018 ; Tóth et al. , 2020 ). However, there is room for further investigation. Examples include the following: Which has a more substantial influence: online or offline WOM? How do salespeople’s explanations and external WOM information influence buyers’ purchase decisions? How much and what kind of WOM is used by B2B firms in the purchase decision-making process? Although pioneering research on WOM in the B2B context has addressed the latter questions ( Martilla, 1971 ), little research has focused on WOM in organizational purchase behavior since then. How much importance do purchasing managers give to WOM information from inside and outside the organization (i.e. intrafirm and interfirm WOM)? How do opinion leaders in an organization influence the purchase decision-making process? What are the characteristics of opinion leaders in an organization? Further research is needed to address these research questions.

One of the main questions on this topic is, “Does WOM usage lead to positive outcomes?” According to previous studies, WOM usage reduces uncertainty about suppliers and B2B offerings and enables firms to search for suitable exchange partners. Consequently, a mismatch of exchange partners can be prevented, thereby improving satisfaction and relationship continuity with the supplier. However, there is no satisfactory evidence on this topic. Intuitively, WOM communication is expected to increase satisfaction in an uncertain environment. Thus, future research can consider environmental factors. Furthermore, Money et al. (1998) showed that the effect of WOM usage on the intention of relationship continuity varies across nations. They focused only on collectivism and uncertainty avoidance among Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions, but how do other cultural dimensions affect WOM usage behaviors? Further research is required to investigate the role of organizational culture.

The following questions about WOM usage can be considered: What types of WOM improve supplier evaluation? How does WOM valence, a concept often used in WOM research in the B2C context, affect B2B offerings? Can negative WOM enhance supplier evaluations? Further, the effects of online reviews remain unclear: What types of online reviews are helpful for B2B firms? Future research should address these questions and provide empirical evidence.

7.3 Reference marketing

The most important consequence is firm performance, such as in sales, profits and market share. Thus, B2B marketers are interested in the impact of reference marketing on firm performance. Terho and Jalkala (2017) found that reference marketing, which consists of both external and internal use of online references, leads to high performance (e.g. new customer acquisition and market share). However, the effectiveness of reference marketing depends on various conditions and situations. Under what conditions is reference marketing effective? Which firms should invest in reference marketing? What type of reference marketing will improve firm performance? The number and type of references, the content of the references and the profile of the reference customers should impact firm performance.

A further exciting topic is the use of references in sales strategy, which has long been used in B2B marketing to promote the sales of a firm’s offerings. In B2B marketing, customer references are not an alternative for a salesperson but rather a supplementary means. Thus, B2B firms need to combine customer and salesperson references to improve their performance. However, little is known about the relationship between sales management and customer references. How does a salesperson use customer references as a sales tool? Do salespeople who use references achieve higher sales than those who do not? How does a sales force respond to potential customers who receive WOM messages about the firm? These questions are of great academic and practical relevance. Therefore, future research should address these questions.

Examining the motivations of existing customers to serve as reference customers can yield rich managerial implications because it can provide selling firms with guidelines regarding the selection and recruitment of reference customers. Intuitively, one of the motivations for a customer to become a reference customer at a supplier’s request would be to strengthen their relationship with the supplier. However, little empirical evidence is provided on reference customer behaviors. Why does a reference customer send WOM for their suppliers? How does becoming a reference customer lead to a close relationship with suppliers? Future studies are encouraged to investigate these research questions.

7.4 Word-of-mouth collection

The theme of WOM collection addresses how firms collect WOM information about their own brands. Prior research in this review assumes that existing customers’ WOM about the supplier’s brand is valuable information for potential customers (e.g. potential customers can rely on WOM information to make accurate purchase decisions). However, it is also beneficial to the supplier itself. WOM information about a supplier’s brand represents the customer’s honest evaluation of the supplier’s products, which allows the supplier to understand the strengths and weaknesses of its own brand, the uniqueness of its own products, and points to be improved in its services. This is a valuable source of information for the supplier. Therefore, firms should actively collect such WOM information about their B2B products/services to develop product innovations and understand the appeal of their brands.

However, according to this systematic review, no studies focused on supplier WOM behavior regarding supplier branding and collection behavior by suppliers. Therefore, future research should address this topic. For example, how can firms collect WOM information about their products from existing customers? It would not be so easy to collect face-to-face WOM information from existing customers. Collecting negative WOM from existing customers is challenging because they do not want to communicate it directly to suppliers. However, suppliers need to collect such information because negative WOM contains information on what needs to be improved in their brands and what customers need. How can firms collect negative WOM? Perhaps, it might be more efficient to collect it indirectly from intermediaries rather than directly from customers ( Ishii, 2021 ).

Regardless of whether WOM is positive or negative, it is valuable information for a firm. It is also precious for an individual salesperson. This is because salespeople who understand the firm’s brand and capture customer needs through WOM can achieve better sales performance than other salespeople. Therefore, salespeople may hesitate to inform other salespeople or their supervisors about WOM about their brand and may keep the information confidential. If this is true, a key factor for WOM collection is establishing a system to gather WOM information from the in-house salespersons. The collection of WOM information, if regarded as the generation of market information, is included in market-oriented behavior ( Ishii, 2020 ; Mostafiz et al. , 2021 ; Powers et al. , 2020 ). It would be interesting to provide empirical evidence on whether the collection of WOM information enhances firm outcomes.

7.5 Word-of-mouth management

The second is the management of WOM about the firm’s brand. Prior studies generally focus on the role of positive WOM, such as sending out positive WOM and posting positive WOM on the company’s website. While previous studies ( Gruber et al. , 2010 ; Homburg and Fürst, 2005 ) have addressed how B2B firms respond to customer complaints (i.e. a type of negative WOM), to the authors’ knowledge, no research has addressed how they respond to negative electronic WOM. This is because, as mentioned above, negative WOM is not often received by suppliers. However, now that social networking services have become widespread, and B2B purchasing managers have formed connections through LinkedIn, Facebook, etc. and informal communication in closed networks has become more accessible, negative WOM can spread quickly among customers. Therefore, how a company responds to negative WOM may impact its survival.

For example, how should B2B firms respond to negative WOM on online review websites? Currently, online review websites for B2B brands are becoming popular. Owing to the source’s anonymity, negative WOM is more likely to be communicated online than in person. Therefore, it will become increasingly critical for B2B marketers to manage negative WOM. Another unanswered question is how B2B marketers should respond to negative WOM on social networking sites. Some B2B brand firms have their own social networking accounts and may receive complaints or requests for improvement on their timelines or through direct messages. How should companies respond to such customer feedback to maintain their high evaluation by their customers? Academic researchers in the field of B2B marketing are expected to make efforts to address these research questions.

8. Conclusion

Both academic researchers and business practitioners have recognized that WOM plays an essential role in B2B marketing. In fact, many B2B studies have examined WOM and reference marketing during the past 20 years. However, no reviews focus on WOM in the B2B context. Since various findings have been presented on this topic, it is imperative to assess the current state of WOM research and clarify unaddressed research questions. This study aims to synthesize the findings from existing studies on WOM in the B2B context, propose an integrated conceptual framework and identify potential research directions.

Through a systematic review, 36 articles on B2B WOM were selected. We then described the published journals, the countries used as the subject of the empirical analysis, and the methods used by these articles. Our thematic analysis categorized these articles into three themes:

Under each theme, we summarized research findings unique to B2B research different from B2C WOM research. We identified several research questions that should be addressed by future research. By synthesizing and assessing prior research on WOM in the B2B context, we hope to have contributed to a better understanding of the B2B WOM phenomenon and facilitated future research on this topic.

WOM phenomenon

Search strategy

Research methods used in selected articles

Researched contexts in selected articles

WOM flowchart in reference marketing

Journals included in the analysis

Overview of the findings from the reviewed articles

Four types of WOM

Aarikka-Stenroos , L. and Sakari Makkonen , H. ( 2014 ), “ Industrial buyers’ use of references, word-of-mouth and reputation in complex buying situation ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 344 - 352 .

Allard , T. , Dunn , L.H. and White , K. ( 2020 ), “ Negative reviews, positive impact: consumer empathetic responding to unfair word of mouth ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 84 No. 4 , pp. 86 - 108 .

Anaza , N.A. and Rutherford , B. ( 2014 ), “ Increasing business-to-business buyer word-of-mouth and share-of-purchase ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 427 - 437 .

Australian Business Deans Council ( 2019 ), “ ABDC journal quality list ”, available at: http://abdc.edu.au/research/abdc-journal-quality-list/ (accessed 28 August 2021 ).

Babić Rosario , A. , de Valck , K. and Sotgiu , F. ( 2020 ), “ Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: what we know and need to know about eWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 422 - 448 .

Babić Rosario , A. , Sotgiu , F. , De Valck , K. and Bijmolt , T.H. ( 2016 ), “ The effect of electronic word of mouth on sales: a meta-analytic review of platform, product, and metric factors ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 53 No. 3 , pp. 297 - 318 .

Barreto , A.M. ( 2014 ), “ The word-of-mouth phenomenon in the social media era ”, International Journal of Market Research , Vol. 56 No. 5 , pp. 631 - 654 .

Berger , J. ( 2014 ), “ Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: a review and directions for future research ”, Journal of Consumer Psychology , Vol. 24 No. 4 , pp. 586 - 607 .

Berger , J. , Sorensen , A.T. and Rasmussen , S.J. ( 2010 ), “ Positive effects of negative publicity: when negative reviews increase sales ”, Marketing Science , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 815 - 827 .

Brock , J.K.U. and Yu Zhou , J. ( 2012 ), “ Customer intimacy ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 370 - 383 .

Cartwright , S. , Liu , H. and Raddats , C. ( 2021 ), “ Strategic use of social media within business-to-business (B2B) marketing: a systematic literature review ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 97 no, pp. 35 - 58 .

Chartered Association of Business School ( 2021 ), “ Academic Journal Guide 2021 ”, available at: http://charteredabs.org/academic-journal-guide-2021/ (accessed August 28 2021 ).

Chawla , V. , Lyngdoh , T. , Guda , S. and Purani , K. ( 2020 ), “ Systematic review of determinants of sales performance: Verbeke et al.’s (2011) classification extended ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 35 No. 8 , pp. 1359 - 1383 .

Chenet , P. , Dagger , T.S. and O’Sullivan , D. ( 2010 ), “ Service quality, trust, commitment and service differentiation in business relationships ”, Journal of Services Marketing , Vol. 24 No. 5 , pp. 336 - 346 .

Chevalier , J.A. and Mayzlin , D. ( 2006 ), “ The effect of word of mouth on sales: online book reviews ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 43 No. 3 , pp. 345 - 354 .

Christofi , M. , Vrontis , D. and Cadogan , J.W. ( 2021 ), “ Micro-foundational ambidexterity and multinational enterprises: a systematic review and a conceptual framework ”, International Business Review , Vol. 30 No. 1 , p. 101625 .

de Matos , C.A. and Vargas Rossi , C.A. ( 2008 ), “ Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: a meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 36 No. 4 , pp. 578 - 596 .

Dobrucalı , B. ( 2019 ), “ Country-of-origin effects on industrial purchase decision making: a systematic review of research ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 34 No. 2 , pp. 401 - 411 .

Donthu , N. , Kumar , S. , Pandey , N. , Pandey , N. and Mishra , A. ( 2021 ), “ Mapping the electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) research: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 135 , pp. 758 - 773 .

Faroughian , F.F. , Kalafatis , S.P. , Ledden , L. , Samouel , P. and Tsogas , M.H. ( 2012 ), “ Value and risk in business-to-business e-banking ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 41 No. 1 , pp. 68 - 81 .

Friend , S.B. and Johnson , J.S. ( 2014 ), “ Key account relationships: an exploratory inquiry of customer-based evaluations ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 43 No. 4 , pp. 642 - 658 .

Gao , W. , Liu , Y. and Qian , L. ( 2016 ), “ The personal touch of business relationship: a study of the determinants and impact of business friendship ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , Vol. 33 No. 2 , pp. 469 - 498 .

Godes , D. ( 2012 ), “ The strategic impact of references in business markets ”, Marketing Science , Vol. 31 No. 2 , pp. 257 - 276 .

Granot , E. , Brashear , T.G. and Motta , P.C. ( 2012 ), “ A structural guide to in‐depth interviewing in business and industrial marketing research ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 27 No. 7 , pp. 547 - 553 .

Gruber , T. , Henneberg , S.C. , Ashnai , B. , Naude , P. and Reppel , A. ( 2010 ), “ Complaint resolution management expectations in an asymmetric business‐to‐business context ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 25 No. 5 , pp. 360 - 371 .

Hada , M. ( 2021 ), “ Two steps: a primer on B2B experiments ”, available at: www.ama.org/2021/01/26/two-steps-a-primer-on-b2b-experiments/ (accessed 8 September 2022 ).

Hada , M. , Grewal , R. and Lilien , G.L. ( 2013 ), “ Purchasing managers’ perceived bias in supplier-selected referrals ”, Journal of Supply Chain Management , Vol. 49 No. 4 , pp. 81 - 95 .

Hada , M. , Grewal , R. and Lilien , G.L. ( 2014 ), “ Supplier-selected referrals ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 78 No. 2 , pp. 34 - 51 .

Hansen , H. , Samuelsen , B.M. and Silseth , P.R. ( 2008 ), “ Customer perceived value in B-t-B service relationships: investigating the importance of corporate reputation ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 37 No. 2 , pp. 206 - 217 .

Hartmann , E. and de Grahl , A. ( 2011 ), “ The flexibility of logistics service providers and its impact on customer loyalty: an empirical study ”, Journal of Supply Chain Management , Vol. 47 No. 3 , pp. 63 - 85 .

Homburg , C. and Fürst , A. ( 2005 ), “ How organizational complaint handling drives customer loyalty: an analysis of the mechanistic and the organic approach ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 69 No. 3 , pp. 95 - 114 .

Hulland , J. and Houston , M.B. ( 2020 ), “ Why systematic review papers and meta-analyses matter: an introduction to the special issue on generalizations in marketing ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 351 - 359 .

Ishii , R. ( 2020 ), “ Manufacturers’ and distributors’ capabilities influencing dual channel choice ”, Marketing Intelligence and Planning , Vol. 39 No. 1 , pp. 151 - 166 .

Ishii , R. ( 2021 ), “ Intermediary resources and export venture performance under different export channel structures ”, International Marketing Review , Vol. 38 No. 3 , pp. 564 - 584 .

Jaakkola , E. and Aarikka-Stenroos , L. ( 2019 ), “ Customer referencing as business actor engagement behavior – creating value in and beyond triadic settings ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 80 no, pp. 27 - 42 .

Jalkala , A. and Salminen , R.T. ( 2009 ), “ Communicating customer references on industrial companies’ web sites ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 38 No. 7 , pp. 825 - 837 .

Jalkala , A. and Salminen , R.T. ( 2010 ), “ Practices and functions of customer reference marketing – leveraging customer references as marketing assets ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 39 No. 6 , pp. 975 - 985 .

Kim , H. ( 2014 ), “ The role of WOM and dynamic capability in B2B transactions ”, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 84 - 101 .

Kim , H. and Hanssens , D.M. ( 2017 ), “ Advertising and word-of-mouth effects on pre-launch consumer interest and initial sales of experience products ”, Journal of Interactive Marketing , Vol. 37 , pp. 57 - 74 .

King , R.A. , Racherla , P. and Bush , V.D. ( 2014 ), “ What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: a review and synthesis of the literature ”, Journal of Interactive Marketing , Vol. 28 No. 3 , pp. 167 - 183 .

Lussier , B. , Grégoirea , Y. and Vachon , M.-A. ( 2017 ), “ The role of humor usage on creativity, trust and performance in business relationships: an analysis of the salesperson-customer dyad ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 65 , pp. 168 - 181 .

Martilla , J.A. ( 1971 ), “ Word-of-mouth communication adoption process ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 173 - 178 .

Minerbo , C. and Brito , L.A.L. ( 2021 ), “ An integrated perspective of value creation and capture: a systematic literature review ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 768 - 789 .

Mo , C. , Yu , T. and de Ruyter , K. ( 2020 ), “ Don’t you (forget about me) the impact of out ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 54 No. 4 , pp. 761 - 790 .

Molinari , L.K. , Abratt , R. and Dion , P. ( 2008 ), “ Satisfaction, quality and value and effects on repurchase and positive word‐of‐mouth behavioral intentions in a B2B services context ”, Journal of Services Marketing , Vol. 22 No. 5 , pp. 363 - 373 .

Money , R.B. ( 2004 ), “ Word-of-mouth promotion and switching behavior in Japanese and American business-to-business service clients ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 57 No. 3 , pp. 297 - 305 .

Money , R.B. , Gilly , M.C. and Graham , J.L. ( 1998 ), “ Explorations of national culture and word-of-mouth referral behavior in the purchase of industrial services in the United States and Japan ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 62 No. 4 , pp. 76 - 87 .

Mostafiz , M.I. , Sambasivan , M. and Goh , S.K. ( 2021 ), “ Antecedents and consequences of market orientation in international B2B market: role of export assistance as a moderator ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 36 No. 6 , pp. 1058 - 1075 .

Novais , L.R. , Maqueira , J.M. and Bruque , S. ( 2019 ), “ Supply chain flexibility and mass personalization: a systematic literature review ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 34 No. 8 , pp. 1791 - 1812 .

Olaru , D. , Purchase , S. and Peterson , N. ( 2008 ), “ From customer value to repurchase intentions and recommendations ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 23 No. 8 , pp. 554 - 565 .

Powers , T.L. , Kennedy , K.N. and Choi , S. ( 2020 ), “ Market orientation and performance: industrial supplier and customer perspectives ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 35 No. 11 , pp. 1701 - 1714 .

Roth , M.S. , Money , R.B. and Madden , T.J. ( 2004 ), “ Purchasing processes and characteristics of industrial service buyers in the US and Japan ”, Journal of World Business , Vol. 39 No. 2 , pp. 183 - 198 .

Ruokolainen , J. and Aarikka-Stenroos , L. ( 2016 ), “ Rhetoric in customer referencing: fortifying sales arguments in two start-up companies ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 54 , pp. 188 - 202 .

Salminen , R.T. and Möller , K. ( 2006 ), “ Role of references in business marketing – towards a normative theory of referencing ”, Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing , Vol. 13 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 51 .

Sheth , J.N. ( 1973 ), “ A model of industrial buyer behavior ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 50 - 56 .

Steward , M.D. , Narus , J.A. and Roehm , M.L. ( 2018 ), “ An exploratory study of business-to-business online customer reviews: external online professional communities and internal vendor scorecards ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 46 No. 2 , pp. 173 - 189 .

Terho , H. and Jalkala , A. ( 2017 ), “ Customer reference marketing: conceptualization, measurement and link to selling performance ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 64 , pp. 175 - 186 .

Tóth , Z. , Nieroda , M.E. and Koles , B. ( 2020 ), “ Becoming a more attractive supplier by managing references – the case of small and medium-sized enterprises in a digitally enhanced business environment ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 84 , pp. 312 - 327 .

Transfield , D. , Denyer , D. and Smart , P. ( 2003 ), “ Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 207 - 222 .

Villanueva , J. , Yoo , S. and Hanssens , D.M. ( 2008 ), “ The impact of marketing-induced versus word-of-mouth customer acquisition on customer equity growth ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 48 - 59 .

Vissa , B. ( 2012 ), “ Agency in action: entrepreneurs’ networking style and initiation of economic exchange ”, Organization Science , Vol. 23 No. 2 , pp. 492 - 510 .

Wallenburg , C.M. ( 2009 ), “ Innovation in logistics outsourcing relationships: proactive improvement by logistics service providers as a driver of customer loyalty ”, Journal of Supply Chain Management , Vol. 45 No. 2 , pp. 75 - 93 .

Wang , S. and Huff , L.C. ( 2007 ), “ Explaining buyers’ responses to sellers’ violation of trust ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 41 Nos 9/10 , pp. 1033 - 1052 .

Webster , F.E. ( 1970 ), “ Informal communication in industrial markets ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 7 No. 2 , pp. 186 - 189 .

Webster , F.E. and Wind , Y. ( 1972 ), “ A general model for understanding organizational buying behavior ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 12 - 19 .

Woodside , A.G. and Wilson , E.J. ( 2003 ), “ Case study research methods for theory building ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 18 Nos 6/7 , pp. 493 - 508 .

Yaghtin , S. , Safarzadeh , H. and Zand , M.K. ( 2021 ), “ B2B digital content marketing in uncertain situations: a systematic review ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 37 No. 9 , pp. 1852 - 1866 .

Yang , Z. , Zhang , H. and Xie , E. ( 2017 ), “ Performance feedback and supplier selection: a perspective from the behavioral theory of the firm ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 63 , pp. 105 - 115 .

You , Y. , Vadakkepatt , G.G. and Joshi , A.M. ( 2015 ), “ A meta-analysis of electronic word-of-mouth elasticity ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 79 No. 2 , pp. 19 - 39 .

Zhang , J. , Jiang , Y. , Shabbir , R. and Zhu , M. ( 2016 ), “ How brand orientation impacts B2B service brand equity? an empirical study among Chinese firms ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 83 - 98 .

Zhu , F. and Zhang , X. ( 2010 ), “ Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: the moderating role of product and consumer characteristics ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 74 No. 2 , pp. 133 - 148 .

Zhu , Y. , Lynette Wang , V. , Wang , Y.J. and Nastos , J. ( 2020 ), “ Business-to-business referral as digital coopetition strategy: insights from an industry-wise digital business network ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 54 No. 6 , pp. 1181 - 1203 .

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Wesley Johnston, and anonymous reviewers for providing valuable insights and constructive comments.

Funding : This work was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K12883.

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Ryuta Ishii is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the College of Business Administration, Ritsumeikan University, Japan. His research interests focus on business-to-business relationships, channel management and international marketing. His work has been published in Industrial Marketing Management , International Marketing Review , Marketing Intelligence & Planning and other journals.

Mai Kikumori is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the College of Business Administration, Ritsumeikan University, Japan. Her research interests focus on digital marketing and social interactions, particularly in word-of-mouth, online review and social media usage.

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

MINI REVIEW article

A literature review of word of mouth and electronic word of mouth: implications for consumer behavior.

- Economía Española e Internacional, Econometría e Historia e Instituciones Económicas, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain

The rise and spread of the Internet has led to the emergence of a new form of word of mouth (WOM): electronic word of mouth (eWOM), considered one of the most influential informal media among consumers, businesses, and the population at large. Drawing on these ideas, this paper reviews the relevant literature, analyzing the impact of traditional WOM and eWOM in the field of consumer behavior and highlighting the main differences between the two types of recommendations, with a view to contributing to a better understanding of the potential of both.

Introduction

Consumers increasingly use online tools (e.g., social media, blogs, etc.) to share their opinions about the products and services they consume ( Gupta and Harris, 2010 ; Lee et al., 2011 ) and to research the companies that sell them. These tools are significantly changing everyday life and the relationship between customers and businesses ( Lee et al., 2011 ).

The rapid growth of online communication through social media, websites, blogs, etc., has increased academic interest in word of mouth (WOM) and electronic word of mouth (eWOM) (e.g., Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004 ; Brown et al., 2007 ; Cheung and Thadani, 2012 ; Hussain et al., 2017 ; Yang, 2017 ). Specifically, the present paper will review the literature on how these two media have evolved, the main differences between them, and the degree to which they influence both businesses and consumers, now that they have become some of the most influential information sources for decision-making.

Word of mouth is one of the oldest ways of conveying information ( Dellarocas, 2003 ), and it has been defined in many ways. One of the earliest definitions was that put forward by Katz and Lazarsfeld (1966) , who described it as the exchanging of marketing information between consumers in such a way that it plays a fundamental role in shaping their behavior and in changing attitudes toward products and services. Other authors (e.g., Arndt, 1967 ) have suggested that WOM is a person-to-person communication tool, between a communicator and a receiver, who perceives the information received about a brand, product, or service as non-commercial. Likewise, WOM has been defined as communication between consumers about a product, service, or company in which the sources are considered independent of commercial influence ( Litvin et al., 2008 ). These interpersonal exchanges provide access to information related to the consumption of that product or service over and above formal advertising, i.e., that goes beyond the messages provided by the companies and involuntarily influences the individual’s decision-making ( Brown et al., 2007 ). WOM is widely regarded as one of the most influential factors affecting consumer behavior ( Daugherty and Hoffman, 2014 ). This influence is especially important with intangible products that are difficult to evaluate prior to consumption, such as tourism or hospitality. Consequently, WOM is considered the most important information source in consumers’ buying decisions ( Litvin et al., 2008 ; Jalilvand and Samiei, 2012 ) and intended behavior. For example, tourist satisfaction is of utmost importance because of its influence on behavioral intentions, WOM and purchasing decisions. In other words, overall satisfaction leads to the possibility of revisiting and recommending the destination ( Sotiriadis and Van Zyl, 2013 ).

Similarly, previous research indicates that consumers regard WOM as a much more reliable medium than traditional media (e.g., television, radio, print advertisements, etc.) ( Cheung and Thadani, 2012 ). It is thus considered one of the most influential sources of information about products and services ( Lee and Youn, 2009 ). Users generally trust other consumers more than sellers ( Nieto et al., 2014 ). As a result, WOM can influence many receivers ( Lau and Ng, 2001 ) and is viewed as a consumer-dominated marketing channel in which the senders are independent of the market, which lends them credibility ( Brown et al., 2007 ). This independence makes WOM a more reliable and credible medium ( Arndt, 1967 ; Lee and Youn, 2009 ).

Today’s new form of online WOM communication is known as electronic word-of-mouth or eWOM ( Yang, 2017 ). This form of communication has taken on special importance with the emergence of online platforms, which have made it one of the most influential information sources on the Web ( Abubakar and Ilkan, 2016 ), for instance, in the tourism industry ( Sotiriadis and Van Zyl, 2013 ). As a result of technological advances, these new means of communication have led to changes in consumer behavior ( Cantallops and Salvi, 2014 ; Gómez-Suárez et al., 2017 ), because of the influence they enable consumers to exert on each other ( Jalilvand and Samiei, 2012 ) by allowing them to obtain or share information about companies, products, or brands ( Gómez-Suárez et al., 2017 ).

One of the most comprehensive conceptions of eWOM was proposed by Litvin et al. (2008) , who described it as all informal communication via the Internet addressed to consumers and related to the use or characteristics of goods or services or the sellers thereof. The advantage of this tool is that it is available to all consumers, who can use online platforms to share their opinions and reviews with other users. Where once consumers trusted WOM from friends and family, today they look to online comments (eWOM) for information about a product or service ( Nieto et al., 2014 ).

As a result of ICT, today consumers from all over the world can leave comments that other users can use to easily obtain information about goods and services. Both active and passive consumers use this information medium (eWOM). Individuals who share their opinions with others online are active consumers; those who simply search for information in the comments or opinions posted by other customers are passive consumers ( Wang and Fesenmaier, 2004 ).

Electronic word of mouth also provides companies with an advantage over traditional WOM insofar as it allows them both to try to understand what factors motivate consumers to post their opinions online and to gauge the impact of those comments on other people ( Cantallops and Salvi, 2014 ). However, consumers’ use of technology to share opinions about products or services (eWOM) can be a liability for companies, as it can become a factor they do not control ( Yang, 2017 ). To counteract this, businesses are seeking to gain greater control of customers’ online reviews by creating virtual spaces on their own websites, where consumers can leave comments and share their opinions about the business’s products and services ( Vallejo et al., 2015 ). By way of example, in the field of tourism, companies are starting to understand that ICT-enabled media influence tourists’ purchasing behavior ( Sotiriadis and Van Zyl, 2013 ).

Understandably, companies view both types of recommendations – WOM and eWOM – as a new opportunity to listen to customers’ needs and adjust how they promote their products or services to better meet them, thereby increasing their return. A negative or positive attitude toward the product or service will influence customers’ future purchase intentions by allowing them to compare the product or service’s actual performance with their expectations ( Yang, 2017 ).

In the field of consumer behavior, some previous studies (e.g., Park and Lee, 2009 ) have shown that consumers pay more attention to negative information than to positive information ( Cheung and Thadani, 2012 ). For example, the customers most satisfied with a product or service tend to become loyal representatives thereof via positive eWOM ( Royo-Vela and Casamassima, 2011 ), which can yield highly competitive advantages for establishments, businesses, or sellers, especially smaller ones, which tend to have fewer resources. Some studies have suggested that traditional WOM is the sales and marketing tactic most often used by small businesses.

Additionally, eWOM offers businesses a way to identify customers’ needs and perceptions and even a cost-effective way to communicate with them ( Nieto et al., 2014 ). Today, eWOM has become an important medium for companies’ social-media marketing ( Hussain et al., 2017 ).

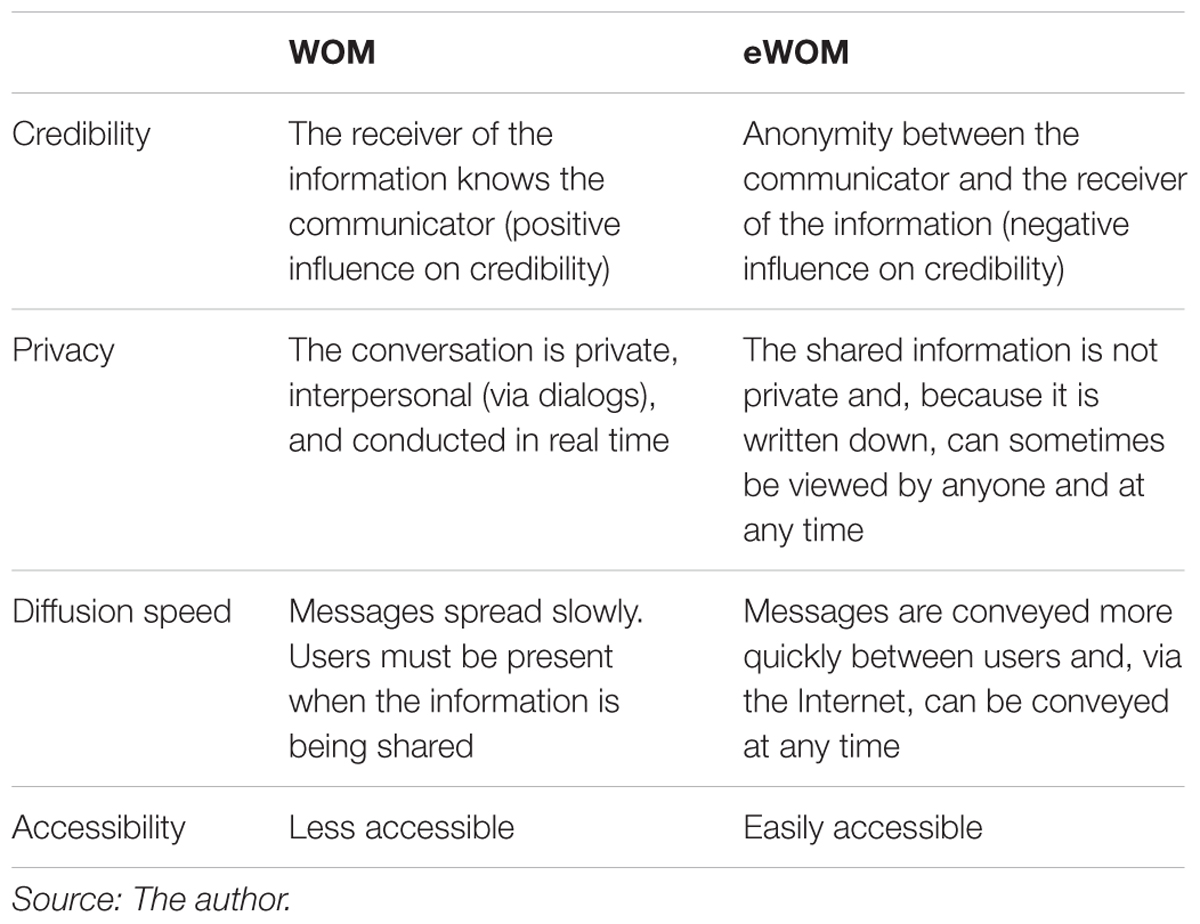

WOM vs. eWOM