- Our Mission

Celebrating Linguistic Diversity in Your Classroom

A fun and meaningful activity can help early elementary students appreciate the different languages in their backgrounds.

Language diversity has never been more real in classrooms around the world. With globalization comes increased mobility, and the language of instruction may not be the one our students choose when they think; speak to their parents, grandparents, and friends; watch TV; read; and listen to music. Acknowledging our students’ language backgrounds and experiences can be powerful: Not only does it contribute to fostering a sense of belonging, but also it supports learners in building their self-identity and celebrating each other’s differences. The question is: How can we do it in a meaningful and engaging way?

Language portraits support language-diverse classrooms

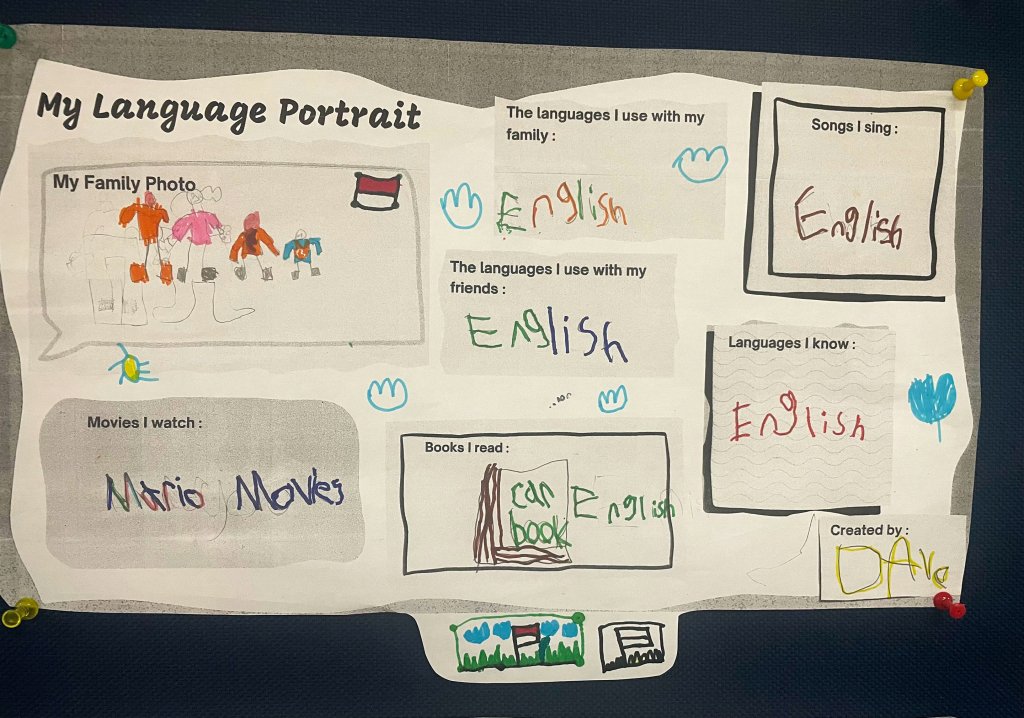

I’ve found that students can use language as a way to create a portrait of themselves. In my class, I have students make language portraits . Language portraits can come in different shapes and sizes, such as posters, collages, questionnaires, journals, and even poetry. The more creativity involved, the more likely students are to be engaged and share their narratives!

Their format is flexible and can be adapted to different contexts, school essential agreements, grade levels, and students’ needs, to name a few. Through them, students are encouraged to inquire into how, when, and why they use certain languages. The language portraits all depend on the prompts, which can even be cocreated with students. They might include the following:

- The language(s) I think in

- The language(s) I use with my family and friends

- The language(s) I am learning now

- The language(s) I have picked up along the way

- The language(s) I would love to learn

With my grade one students this year, the prompts included “Songs I sing,” “Books I read,” “The language I use with my family and friends,” “Languages I know,” “Movies I watch,” and “My family photo.” The students’ colorful drawings and writings were a delight to look at, but, most important, their reflections resulted in many insights to support their learning and their sense of belonging.

Language Portraits Have a 6-Step Process

Receiving a task to complete without any context or purpose is uninspiring, to say the least. Therefore, I planned a six-step process for the learning experience in my grade one class.

- To set the scene, we read Victor D. O. Santos’s story, Little Polyglot Adventures: Dylan’s Birthday Present as a group.

- I modeled the making of my own language portrait while explaining how my language of preference varies according to what I’m doing and to whom I’m speaking.

- In small groups, I sat together with my students to brainstorm and discuss the languages they’re exposed to and use.

- Ready, set, go: Students developed their language portraits.

- My students proudly presented their productions by explaining each section of their language portraits. This was an essential part of the process; without it, a language portrait might be just one more task to be completed and forgotten forever.

- Language portraits were displayed on the outside board as a celebration of their reflection and learning.

The process above worked very well for my context and age group and is not a fixed recipe or formula for success. I encourage teachers to think of their students when setting the mood and supporting students to reflect on their language backgrounds.

Language Portraits Help Guide Instruction

Through these presentations, I found out that my Indonesian student communicates in Indonesian with his Indonesian mother and French with his Madagascan father. Another student speaks Mandarin to their grandparents and is learning Korean by watching Korean dramas. English is the main language of instruction at school, but there could be other languages in my students’ backgrounds.

Knowing this information guides me when choosing books for our reading corner, tales to read, and facts that will speak to them. It also helps me to connect with my students: One smiled from ear to ear one morning when I surprised him with a “Bonjour.” Now, when we sing “Happy Birthday,” we do so in all the languages represented in our class. Chaotic? Yes. Inclusive? Always!

Apart from the helpful data for planning, goal setting, and developing learning experiences that reflect my students’ realities, language portraits have been equally valuable for my students. Most of them had never really thought about how the languages they speak make them multilingual or wondered where their communication preferences come from. Creating a language portrait is a powerful, reflective exercise of self-identity.

Language Portraits Have Lasting Benefits

My school saves students’ language portraits in their digital portfolios, enabling teachers, families, and students to easily refer to them in the future and make comparisons. In the past, I placed them in students’ pass-on files and physical portfolios, which they carried to other grades. The examples I’ve shared reflect my experience with grade one, but language portraits can be developed across a continuum, from early grades to high school, with different levels of support and guidance according to grade-level needs.

Language portraits have developed my first-grade students’ understanding of their own language experiences and raised their awareness and appreciation of differences. My students support each other to communicate and are curious about how to say words in other languages. Those who are developing their fluency in English understand that they aren’t alone and that most in our class come from diverse backgrounds.

Acknowledging and celebrating diversity fosters communication skills, confidence, and well-being. Above all, it helps students to be proud of themselves and their languages and to feel seen and valued—all of which are so important when building a culturally responsive learning community and preparing students for a multicultural world.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

- How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

Published on November 1, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Table of contents

What is a diversity essay, identify how you will enrich the campus community, share stories about your lived experience, explain how your background or identity has affected your life, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Diversity essays ask students to highlight an important aspect of their identity, background, culture, experience, viewpoints, beliefs, skills, passions, goals, etc.

Diversity essays can come in many forms. Some scholarships are offered specifically for students who come from an underrepresented background or identity in higher education. At highly competitive schools, supplemental diversity essays require students to address how they will enhance the student body with a unique perspective, identity, or background.

In the Common Application and applications for several other colleges, some main essay prompts ask about how your background, identity, or experience has affected you.

Why schools want a diversity essay

Many universities believe a student body representing different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community.

Through the diversity essay, admissions officers want students to articulate the following:

- What makes them different from other applicants

- Stories related to their background, identity, or experience

- How their unique lived experience has affected their outlook, activities, and goals

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Think about what aspects of your identity or background make you unique, and choose one that has significantly impacted your life.

For some students, it may be easy to identify what sets them apart from their peers. But if you’re having trouble identifying what makes you different from other applicants, consider your life from an outsider’s perspective. Don’t presume your lived experiences are normal or boring just because you’re used to them.

Some examples of identities or experiences that you might write about include the following:

- Race/ethnicity

- Gender identity

- Sexual orientation

- Nationality

- Socioeconomic status

- Immigration background

- Religion/belief system

- Place of residence

- Family circumstances

- Extracurricular activities related to diversity

Include vulnerable, authentic stories about your lived experiences. Maintain focus on your experience rather than going into too much detail comparing yourself to others or describing their experiences.

Keep the focus on you

Tell a story about how your background, identity, or experience has impacted you. While you can briefly mention another person’s experience to provide context, be sure to keep the essay focused on you. Admissions officers are mostly interested in learning about your lived experience, not anyone else’s.

When I was a baby, my grandmother took me in, even though that meant postponing her retirement and continuing to work full-time at the local hairdresser. Even working every shift she could, she never missed a single school play or soccer game.

She and I had a really special bond, even creating our own special language to leave each other secret notes and messages. She always pushed me to succeed in school, and celebrated every academic achievement like it was worthy of a Nobel Prize. Every month, any leftover tip money she received at work went to a special 509 savings plan for my college education.

When I was in the 10th grade, my grandmother was diagnosed with ALS. We didn’t have health insurance, and what began with quitting soccer eventually led to dropping out of school as her condition worsened. In between her doctor’s appointments, keeping the house tidy, and keeping her comfortable, I took advantage of those few free moments to study for the GED.

In school pictures at Raleigh Elementary School, you could immediately spot me as “that Asian girl.” At lunch, I used to bring leftover fun see noodles, but after my classmates remarked how they smelled disgusting, I begged my mom to make a “regular” lunch of sliced bread, mayonnaise, and deli meat.

Although born and raised in North Carolina, I felt a cultural obligation to learn my “mother tongue” and reconnect with my “homeland.” After two years of all-day Saturday Chinese school, I finally visited Beijing for the first time, expecting I would finally belong. While my face initially assured locals of my Chinese identity, the moment I spoke, my cover was blown. My Chinese was littered with tonal errors, and I was instantly labeled as an “ABC,” American-born Chinese.

I felt culturally homeless.

Speak from your own experience

Highlight your actions, difficulties, and feelings rather than comparing yourself to others. While it may be tempting to write about how you have been more or less fortunate than those around you, keep the focus on you and your unique experiences, as shown below.

I began to despair when the FAFSA website once again filled with red error messages.

I had been at the local library for hours and hadn’t even been able to finish the form, much less the other to-do items for my application.

I am the first person in my family to even consider going to college. My parents work two jobs each, but even then, it’s sometimes very hard to make ends meet. Rather than playing soccer or competing in speech and debate, I help my family by taking care of my younger siblings after school and on the weekends.

“We only speak one language here. Speak proper English!” roared a store owner when I had attempted to buy bread and accidentally used the wrong preposition.

In middle school, I had relentlessly studied English grammar textbooks and received the highest marks.

Leaving Seoul was hard, but living in West Orange, New Jersey was much harder一especially navigating everyday communication with Americans.

After sharing relevant personal stories, make sure to provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your perspective, activities, and goals. You should also explain how your background led you to apply to this university and why you’re a good fit.

Include your outlook, actions, and goals

Conclude your essay with an insight about how your background or identity has affected your outlook, actions, and goals. You should include specific actions and activities that you have done as a result of your insight.

One night, before the midnight premiere of Avengers: Endgame , I stopped by my best friend Maria’s house. Her mother prepared tamales, churros, and Mexican hot chocolate, packing them all neatly in an Igloo lunch box. As we sat in the line snaking around the AMC theater, I thought back to when Maria and I took salsa classes together and when we belted out Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” at karaoke. In that moment, as I munched on a chicken tamale, I realized how much I admired the beauty, complexity, and joy in Maria’s culture but had suppressed and devalued my own.

The following semester, I joined Model UN. Since then, I have learned how to proudly represent other countries and have gained cultural perspectives other than my own. I now understand that all cultures, including my own, are equal. I still struggle with small triggers, like when I go through airport security and feel a suspicious glance toward me, or when I feel self-conscious for bringing kabsa to school lunch. But in the future, I hope to study and work in international relations to continue learning about other cultures and impart a positive impression of Saudi culture to the world.

The smell of the early morning dew and the welcoming whinnies of my family’s horses are some of my most treasured childhood memories. To this day, our farm remains so rural that we do not have broadband access, and we’re too far away from the closest town for the postal service to reach us.

Going to school regularly was always a struggle: between the unceasing demands of the farm and our lack of connectivity, it was hard to keep up with my studies. Despite being a voracious reader, avid amateur chemist, and active participant in the classroom, emergencies and unforeseen events at the farm meant that I had a lot of unexcused absences.

Although it had challenges, my upbringing taught me resilience, the value of hard work, and the importance of family. Staying up all night to watch a foal being born, successfully saving the animals from a minor fire, and finding ways to soothe a nervous mare afraid of thunder have led to an unbreakable family bond.

Our farm is my family’s birthright and our livelihood, and I am eager to learn how to ensure the farm’s financial and technological success for future generations. In college, I am looking forward to joining a chapter of Future Farmers of America and studying agricultural business to carry my family’s legacy forward.

Tailor your answer to the university

After explaining how your identity or background will enrich the university’s existing student body, you can mention the university organizations, groups, or courses in which you’re interested.

Maybe a larger public school setting will allow you to broaden your community, or a small liberal arts college has a specialized program that will give you space to discover your voice and identity. Perhaps this particular university has an active affinity group you’d like to join.

Demonstrating how a university’s specific programs or clubs are relevant to you can show that you’ve done your research and would be a great addition to the university.

At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to study engineering not only to emulate my mother’s achievements and strength, but also to forge my own path as an engineer with disabilities. I appreciate the University of Michigan’s long-standing dedication to supporting students with disabilities in ways ranging from accessible housing to assistive technology. At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to receive a top-notch education and use it to inspire others to strive for their best, regardless of their circumstances.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

In addition to your main college essay , some schools and scholarships may ask for a supplementary essay focused on an aspect of your identity or background. This is sometimes called a diversity essay .

Many universities believe a student body composed of different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community, which is why they assign a diversity essay .

To write an effective diversity essay , include vulnerable, authentic stories about your unique identity, background, or perspective. Provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your outlook, activities, and goals. If relevant, you should also mention how your background has led you to apply for this university and why you’re a good fit.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/diversity-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, how to write about yourself in a college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to write a scholarship essay | template & example, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Language diversity in the classroom: From intention to practice

Related Papers

Sabrina Sembiante

Educational Researcher

Rebecca Wheeler

Karen Hornick

Stephen May

Literacy Research: Theory, Method, & Practice

Chris K . Chang-Bacon

This study bridges the dichotomies between the study of multilingualism and multi-dialecticism to explore the mythologies surrounding what is often called Standard English (*SE). While literacy and teacher education have made progress toward preparing teachers to work with linguistically diverse populations, such preparation is usually geared exclusively toward multilingual learners. Through this study, I argue that the field must also prepare teachers for the dialectal diversity that characterizes U.S. classrooms but is often framed through racialized deficit ideologies. To fulfill this goal, this study outlines a module on multidialecticism embedded into a course on teaching multilingual learners. Drawing on survey data, participant reflections, and classroom observations, I explore the affordances and limitations of this module, asking how teachers' conceptualizations of linguistic diversity developed over the course of the semester. Initial findings highlight participants' reliance on surface-level structural features, commonality arguments, and cosmetic word exchanges in conceptualizing *SE. While varying degrees of complexity and sociolinguistic analysis emerged through participants' engagement in the module, changes were generally minor cosmetic shifts through which underlying deficit ideologies were maintained. This study brings into question the extent to which the field has made progress in

Linguistics and Education

Megan Weaver

Language Arts

English Teaching Practice and Critique

This paper aims to address concerns of English teachers considering opening up their classrooms to multiple varieties of English. Drawing on the author’s experience as a teacher educator and professional developer in different regions of the USA, this narrative paper groups teachers’ concerns into general categories and offers responses to the most common questions. Teachers want to know why they should make room in their classrooms for multiple Englishes; what they should teach differently; how they learn about English variation; how to balance Standardized English and other Englishes; and how these apply to English Learners and/or White speakers of Standardized English. The study describes the author’s approach to teaching about language as a way to promote social justice and equality, the value of increasing students’ linguistic repertoires and why it is necessary to address listeners as well as speakers. As teachers attempt to adopt and adapt new approaches to teaching English language suggested in the research literature, they need to know their challenges and concerns are heard and addressed. Teacher educators working to support these teachers need ways to address teachers’ concerns. This paper emphasizes the importance of teaching mainstream, White, Standard English-speaking students about English language variation. By emphasizing the role of the listener and teaching students to hear language through an expanded language repertoire, English teachers can reduce the prejudice attached to historically stigmatized dialects of English. This paper provides a needed perspective on how to work with teachers who express legitimate concerns about what it means to de-center Standardized English in English classrooms.

Journal of College Reading and Learning

Rachele Lawton

In spite of years of sociolinguistic research establishing that all language varieties are valid and equal, there is a disconnect between this knowledge and pedagogical practices at the college level. Certain Englishes, particularly those of minoritized speakers, are stigmatized, and "standard" English is upheld as the goal of writing and literacy instruction. To better understand this disconnect , we conducted a study to examine writing and literacy instructors' attitudes toward "standard" and "nonstandard" Englishes in the community college setting. Employing a critical discursive approach to analyze language ideologies, we discovered that instructors held beliefs that were deeply rooted in standard language ideology, including attitudes toward nonstan-dard Englishes that superficially expressed tolerance but which underlyingly revealed rejection through lack of appreciation and validation. We argue that professional development that focuses on developing critical language awareness is needed for instructors , which-crucially-must begin with increasing awareness of the language ideologies that govern our beliefs, as these ideologies ultimately discriminate against speakers of stigmatized languages.

American Speech

Nicoleta Bateman

RELATED PAPERS

Atherosclerosis

Peter Laggner

Revista Cuadernos Fhycs Unju

Jorge Kulemeyer

Archivos de medicina veterinaria

Norma Pereyra

Cadernos de Saúde Pública

Paulo Peiter

Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project

Kevin Pickering

Blood Advances

Junichi Hara

Musikolastika: Jurnal Pertunjukan dan Pendidikan Musik

Bahtiar Arbi

Sidhartha Bhowmick

Renata Aliani

American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology

Rebecca Bertrand

Journal of Complexity

Xizhong Zheng

International Journal of Political Science

Joaquim Tres

Deasy Putri Avanda Sari (C1C020176)

Natural Science: Journal of Science and Technology

Wilson Novarino

Molecular Therapy

Caralee Schaefer

Ciencia latina

Maxwell Mezomo

Revista Latinoamericana de Bioética

Luis Alfredo

Ricyde. Revista Internacional De Ciencias Del Deporte

Jose Linaza

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Izu Nwachukwu

Sergij Shiyanovskii

ChemistrySelect

Hande Karaoglu

Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics

Scott Wolpert

msal.gov.ar

ALEJANDRA BARRIO

Open Forum Infectious Diseases

Francisco Diaz

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Language Diversity in the Classroom

- John Edwards

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Multilingual Matters

- Copyright year: 2009

- Main content: 312

- Keywords: Language Diversity ; language education ; Foreign Language Teaching ; bilingual education

- Published: November 16, 2009

- ISBN: 9781847692276

Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom Essay

Issues around cultural diversity in classroom, the concept of multiculturalism in australia, political and social climate influence on students’ achievements, culturally competent and multicultural education.

Diversity in a classroom can be a rewarding experience for students, as it could increase their awareness of other cultures and teach them how to collaborate with people from different backgrounds. However, diversity can also be challenging for teachers because it requires them to use an informed approach to developing a positive and inclusive classroom environment and adjust the lessons to the needs of all students. When I was in school, there were a lot of students in my class who came from different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. For example, we had two students from immigrant families whose first language was not English, as well as several Indigenous students. We also had children from different socio-economic backgrounds, including those from low-income families. As the majority of the students were white and from middle-class families, students from other backgrounds were seen as different and sometimes struggled to communicate or blend in with the rest of the class.

Unfortunately, my school did not address these students’ differences in any formal way. However, some teachers attempted to facilitate communication with students from immigrant families by engaging them in discussion and encouraging them to develop their English skills. This was particularly helpful for one of the students, who had the opportunity to improve her English skills. Others, however, were shy to participate in the conversation and made little progress with their language skills. My classmates did not try to address the cultural, socio-economic, and linguistic differences, which led to students forming several different small groups. There was also a problem of bullying in my school, and students from diverse backgrounds were often targeted by bullies.

Thus, I believe that my school and teachers did not address classroom diversity appropriately. I think it would be more practical if the school has taken action against the bullying of students from minority groups and taught students about cultural diversity and communicating with people from various backgrounds. Providing English lessons for students from immigrant families would also help to promote communication. Finally, I believe that the school could offer extra-curricular activities aimed at improving children’s awareness of other cultures. This could assist in addressing barriers to communication and facilitate a sense of community while also teaching students to respect those who are different in any way.

Overall, if I had to teach a class that has students from diverse backgrounds, I would aim to ensure that all students get equal opportunities to learn. To do that, I would partner with children from all backgrounds and their parents to develop a suitable curriculum. I would also apply teaching methods that promote discussion in the classroom, which would help to engage students from different cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic backgrounds. I would also partner with school leaders to develop and implement an effective strategy for preventing bullying and promoting cultural awareness in all students through extra-curricular events and activities.

The first topic of the class explored the concept of multiculturalism as it applies to Australia. In particular, the readings focused on political approaches to multiculturalism, as well as on its integration in schools. For instance, Jupp (2002) described some of the criticism of multiculturalism. According to Jupp (2002), multiculturalism raised several issues with the Indigenous peoples, as they were perceived as distinct from other minority cultural groups. Multiculturalism was considered to be an alternative to cultural assimilation, which threatened the identity of Aboriginal people. However, it was also seen as a divisive policy contradicting the notion of ‘one Australia’.

A similar discussion is evident in the second reading, as it discusses the application of multiculturalism to education. Smolicz (1999) raises the issue of dominant versus minority groups, arguing that most approaches to politics and education in these settings lead to cultural reductionism. Another problem with cultural assimilation that is noted by the author is that it does not lead to equal treatment. Smolicz (1999) argues that educational programs promoting multiculturalism should incorporate minority ethnic content into the curriculum. Thus, the chapter shows the necessity of integrating minority cultures into teaching.

Hill and Alan (2004) also describe the relationship between political movements and education in Australia. The authors consider the conflict between cultural assimilation in education and preserving Indigenous identity. Leeman and Reid (2006) reflect on the essence of multicultural education in Australia, showing how it aims to promote cultural assimilation by reducing social exclusion and fostering communication among the students. The article also notes that preserving the Indigenous culture is critical, as the loss of culture can have a profound effect on the youth.

My plan of addressing cultural diversity in the classroom appears to be similar to the approach promoted in multicultural education. However, the readings show that this approach is not always correct. For example, helping students to learn the English language could affect their cultural values and heritage, as culture and language are tightly connected (Smolicz, 1999). My plan would also promote cultural assimilation, which can have a negative influence on the students and their identity. Particularly in the case of Indigenous populations, cultural assimilation does not help to resolve the problems experienced by minority groups (Smolicz, 1999). While various events can help to improve cultural awareness among students and reduce tension between dominant and minority groups, it does not integrate minority cultures into the curriculum. Thus, I can see that my approach is rather one-sided and does not target the cultural needs of minority students.

Based on the readings for Topic 1, I would make some corrections to my approach. First of all, it would be critical to include education about minority cultures in the curriculum. For instance, when studying a topic, it would be beneficial to consider it from the viewpoint of the dominant culture, as well as the minority groups. This strategy would help to engage minority students in the discussion while taking into account their cultural heritage. Secondly, I would also consider additive bilingualism as a strategy for addressing multiculturalism (Smolicz, 1999). Given the importance of language to cultural heritage, it would be beneficial to provide students from minority cultural groups with the opportunity to learn their native language in the same way as they are learning English. This strategy would require a commitment from the school and its leaders, but it could be a helpful solution. Lastly, while I believe that extra-curricular events for promoting cultural awareness are useful, it is also essential to address the minority groups’ needs for cultural separatism. Introducing extra-curricular activities for students of specific minority groups would enable them to retain their cultural identity.

The readings for Topic 2 explored the impact of the political and social climate on students’ achievement. For example, Cummins (1997) shows that the coercive and collaborative relations of power impact both the educator role definitions and educational structures, thus affecting the interactions between teachers and students and students’ engagement in learning. While coercive relations of power reinforce the relationship between the dominant and the subordinate group, collaborative relations promote empowerment and communication across the boundaries. Delpit (1988) also considers the influence of power structures on learning in culturally diverse classrooms. The author shows how interrelations of power affect students’ learning, explaining how teachers can target oppressive power structures within their classrooms to promote a safe learning environment.

Other authors also consider students’ academic achievement as a result of the roles reinforced by dominant cultural groups. For example, Fordham and Ogbu (1986) state that the problem of underachievement of black students arose as part of cultural stereotypes created by the dominant white culture, which deemed black people less intellectually capable. As a result, academic achievement is often seen as white people’s prerogative, and black Americans began to discourage their peers from “acting white” and striving for academic success (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986). The authors thus show that the problem of academic achievement is rooted in stereotypes that were enforced by the dominant culture.

Kohl (2007) offers another viewpoint on students’ lack of academic achievement, arguing that non-learning is a choice stemming from the desire to avoid oppression, racism, and similar challenges. For instance, students from cultural or ethnic minorities might find the majority of textbooks racist and thus refuse to study the material presented in it. The author explains that the best strategy, in this case, is to teach the students how to acknowledge, question, and confront oppression in all settings instead of avoiding it. Finally, Mansouri and Trembath (2005) also highlight the role of the political climate in the minority students’ classroom achievement. The article shows how educators should seek to challenge social inequality experienced by minority groups, thus engaging in a dialogue with students and parents.

After reading the materials for this topic, it became clear that I did not address underachievement and academic struggles as part of my plan for promoting cultural diversity. I believe that this was mainly because I did not acknowledge the effect that social inequality has on students and their academic life. The articles on this topic showed that students from minority groups are often less likely to succeed academically, and their learning is affected by external social and political forces. In particular, I found Cummins’ (1997) discussion of influences useful in explaining minority students’ attitudes towards learning. However, it is also important that all of the articles highlighted the teacher’s role in mediating the relationship between coercive power relations and academic achievement.

Therefore, based on the readings, it would be essential to expand my plan for addressing cultural diversity. In particular, it is critical to establish a collaborative relationship with all students, thus empowering them to achieve academic success. The knowledge of this topic would also help address underachieving students. As an educator, I should allow students to challenge the information presented in textbooks and other readings so that they would learn how to acknowledge and question oppressive systems in real life. Additionally, it would be useful to offer students and parents additional resources for improving achievement. For example, if the student is struggling despite the efforts to address the problem, they could benefit from a minority-friendly psychologist, who would help them to improve motivation.

The materials for Topic 3 review strategies for culturally competent and multicultural education. Grant and Sleeter (2003) offer a questionnaire that can be used by teachers to examine the extent to which a classroom or a school is accommodating to the needs of students from minority groups. The assessment considers a variety of learning components, from visuals in presentations to staff resources. Additionally, the questionnaire examines gender equality in education, which is also relevant to the topic of classroom diversity. Based on this activity, educators can determine the gaps in their approach to diversity. Ladson-Billings (1995) reflect on the components of culturally relevant teaching, drawing a link between cultural competence and academic success. In particular, the author argues that teachers should use students’ culture as a “vehicle for learning” (p. 161). The article also suggests some useful strategies for teaching in culturally diverse classrooms, including parent involvement, promoting sociopolitical consciousness, and fostering a collaborative relationship with students.

Other authors stress the importance of comprehensive multicultural education in their texts. For instance, Nieto and Bode (2008) define multicultural education as “a process of comprehensive school reform and basic education for all students” (p. 44). They also describe seven critical features of multicultural education, which can be used by teachers to apply multiculturalism in their classrooms. Pearce (2005) explains some of the main mistakes made by teachers in culturally diverse classrooms, which include avoiding differences and racism. According to the author, teachers should provide a safe environment for critical, cross-cultural discussions to promote diversity. Lastly, Burridge, Buchanan, and Chodkiewicz (2009) offer comprehensive strategies for teachers to respond to cultural diversity. The authors state that teachers should counter racism, promote representations of cultural diversity, and encourage cultural exchange throughout schools.

Overall, the resources for Topic 3 provided useful insights into creating a practical approach to cultural diversity. Looking at the initial essay, I understand that my plan for addressing cultural diversity was somewhat relevant, but not comprehensive. For instance, in terms of school policies, it only considered anti-bullying efforts. However, as shown by Grant and Sleeter (2003), schools are also involved in establishing an inclusive environment for all students. To develop my plan further, I would focus on changes on the school level. For example, it is essential to ensure that the plan for selecting study materials includes the criteria for multicultural education and that the school library reflects cultural and language diversity (Grant & Sleeter, 2003). Special events hosted by the school should also consider diversity and should be relevant to students from all cultural, racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds.

Another essential addition to my plan would be a collaboration with parents in all aspects of learning. Ladson-Billings (1995) note that families are often a valuable cultural resource for young students, and thus involving parents in various events and discussing learning goals with them could improve the school’s approach to cultural diversity. For instance, when planning events for students, I could consult with parents about the aspects of their culture that could be reflected in the event.

Furthermore, the resources also provided a useful framework for resolving diversity-related problems in class, such as cultural differences, racism, and more. As a teacher, I should be active in responding to these problems instead of avoiding them. For example, taking note of cultural differences among the students and challenging racist views or expressions are meaningful strategies for addressing diversity-related issues. In general, all of the approaches explained in the materials for this topic could be successfully incorporated in an Australian classroom. Moreover, these strategies could complement the ones developed after reading the articles for previous topics, thus forming a comprehensive plan for approaching diversity.

Burridge, N., Buchanan, J. D., & Chodkiewicz, A. K. (2009). Dealing with difference: Building culturally responsive classrooms. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 1 (3), 68-83.

Cummins, J. (1997). Minority status and schooling in Canada. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 28 (3), 411-430.

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, 58 (3), 280-299.

Fordham, S., & Ogbu, J. U. (1986). Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of ‘acting white’”. The Urban Review, 18 (3), 176-206.

Grant, C. A., & Sleeter, C. (2003). Action research activity 5.2: Classroom and school assessment. In C. A. Grant & C. Sleeter (Eds.), Turning on learning: Five approaches for multicultural teaching plans for race, class, gender, and disability (pp. 213-215). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Hill, B., & Allan, R. (2004). Multicultural education in Australia. In J. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 979-996). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Jupp, J. (2002). The attack on multiculturalism. In J. Jupp (Ed.), From white Australia to Woomera: The story of Australian immigration (pp. 105-122). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kohl, H. (2007). ‘I won’t learn from you!’: Confronting student resistance. In W. Au, B. Bigelow & S. Karp (Eds.), Rethinking our classrooms: Teaching for equality and justice (vol. 1, pp. 165-166). Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools Ltd.

Ladson‐Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159-165.

Leeman, Y., & Reid, C. (2006). Multi/intercultural education in Australia and the Netherlands. Compare A Journal of Comparative and International Education , 36 (1), 57-72.

Mansouri, F., & Trembath, A. (2005). Multicultural education and racism: The case of Arab-Australian students in contemporary Australia. International Education Journal, 6 (4), 516-529.

Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2009). Multicultural education and school reform. In S. Nieto & P. Bode (Eds.), Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (5th ed., pp. 42-62). Sydney, Australia: Pearson.

Pearce, S. (2003). The teacher as a problem. In S. Pearce (Ed.), You wouldn’t understand: White teachers in multiethnic classrooms (pp. 29-51). Trent, UK: Trentham Books.

Smolicz, J.J. (1999). Culture, ethnicity and education: Multiculturalism in a plural society. In M. Secombe & J. Zadja (Eds.), J.J. Smolicz on education and culture . Melbourne, Australia: James Nicholas Publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, November 27). Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom. https://ivypanda.com/essays/multicultural-diversity-and-performance-in-the-classroom/

"Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom." IvyPanda , 27 Nov. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/multicultural-diversity-and-performance-in-the-classroom/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom'. 27 November.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom." November 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/multicultural-diversity-and-performance-in-the-classroom/.

1. IvyPanda . "Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom." November 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/multicultural-diversity-and-performance-in-the-classroom/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Multicultural Diversity and Performance in the Classroom." November 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/multicultural-diversity-and-performance-in-the-classroom/.

- Multicultural Australia: Multiculturalism and the Context

- Multiculturalism in Education

- Arguments For and Against Multiculturalism

- Multiculturalism in the International Community

- “The Menace of Multiculturalism" by McKenzie Critique

- Power of Agency in a Multicultural Classroom

- Multiculturalism and Diversity in Higher Education Institutions

- Canadian Immigration and Multiculturalism

- Policy of Ethnicity and Identity: Multiculturalism

- Multiculturalism, the Italian Culture

- School Climate and Student Culture

- Cultural Agents in Organizing and Influencing Learning

- Language Preferences in Multicultural Class

- Education and Religion: Old and New Patterns

- Cross-Cultural Interactions at Wake Forest University

- Language Diversity in the Classroom: From Intention to Practice

In this Book

- Edited by Geneva Smitherman and Victor Villanueva. Foreword by Suresh Canagarajah

- Published by: Southern Illinois University Press

It’s no secret that, in most American classrooms, students are expected to master standardized American English and the conventions of Edited American English if they wish to succeed. Language Diversity in the Classroom: From Intention to Practice works to realign these conceptions through a series of provocative yet evenhanded essays that explore the ways we have enacted and continue to enact our beliefs in the integrity of the many languages and Englishes that arise both in the classroom and in professional communities.

Edited by Geneva Smitherman and Victor Villanueva, the collection was motivated by a survey project on language awareness commissioned by the National Council of Teachers of English and the Conference on College Composition and Communication.

All actively involved in supporting diversity in education, the contributors address the major issues inherent in linguistically diverse classrooms: language and racism, language and nationalism, and the challenges in teaching writing while respecting and celebrating students’ own languages. Offering historical and pedagogical perspectives on language awareness and language diversity, the essays reveal the nationalism implicit in the concept of a “standard English,” advocate alternative training and teaching practices for instructors at all levels, and promote the respect and importance of the country’s diverse dialects, languages, and literatures.

Contributors include Geneva Smitherman, Victor Villanueva, Elaine Richardson, Victoria Cliett, Arnetha F. Ball, Rashidah Jammi` Muhammad, Kim Brian Lovejoy, Gail Y. Okawa, Jan Swearingen, and Dave Pruett.

The volume also includes a foreword by Suresh Canagarajah and a substantial bibliography of resources about bilingualism and language diversity.

Table of Contents

- Front Cover

- Title page, Copyright page

- pp. vii-viii

- pp. ix-xviii

- Introduction

- 1. The Historical Struggle for Language Rights in CCCC

- Geneva Smitherman

- 2. Race, Class(es), Gender, and Age: The Making of Knowledge about Language Diversity

- Elaine Richardson

- 3. The Expanding Frontier of World Englishes: A New Perspective for Teachers of English

- Victoria Cliett

- 4. Language Diversity in Teacher Education and in the Classroom

- Arnetha F. Ball and Rashidah Jaami Muhammad

- 5. Practical Pedagogy for Composition

- Kim Brian Lovejoy

- 6. “Resurfacing Roots” : Developing a Pedagogy of Language Awareness from Two Views

- Gail Y. Okawa

- pp. 109-133

- 7. Language Diversity and the Classroom: Problems and Prospects, a Bibliography

- C. Jan Swearingen and Dave Pruett

- pp. 134-150

- Contributors

- pp. 151-156

- pp. 157-162

- Series Statement

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Professional development

- Using inclusive practices

Raising awareness of diversity in the language classroom

In most groups of learners there will be some obvious differences that everyone can see (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity).

Depending on the setting, there may be differences in the learners’ linguistic profiles (which languages a person understands/speaks/ reads/writes) and lifestyle choices (e.g. working patterns, dietary choices, religious affiliations). Even in apparently homogeneous groups there will be aspects of identity that individual members may or may not be happy to disclose, such as specific skills and talents (e.g. musical prowess or sporting achievement) or sexual orientation. In the language learning context, perhaps the most significant dimensions of diversity relate to physical or sensory impairment (e.g. a long-term health issue or hearing loss) and neurodiversity (i.e. non-typical ways of processing information, often identified as dyslexia, dyspraxia or another specific learning difference). It is these aspects that this article focuses on, because of the challenges they present for language learners. Inclusive classrooms

In many schools and colleges, the drive to create a more inclusive learning environment is picking up pace. Teachers (as well as publishers and exam boards) are discovering that it is possible to adapt classroom management, materials and processes to make them more accessible to increasingly diverse cohorts of learners. The use, for example, of pastel-coloured handouts and more multisensory activities is very much to be applauded and encouraged. However, these practical changes in the classroom will remain superficial signs of inclusive practice unless they are accompanied by a fundamental shift in underlying attitudes, of both the teaching staff and the students themselves. To achieve this, members of the learning community need to become aware of just how diverse they are as a group, and to value what each individual can contribute – including themselves. Teachers play a crucial role in establishing an inclusive culture in their classrooms and can build awareness-raising activities into the language curriculum. There are several ways in which this can be achieved, including group discussions, the use of materials featuring diverse characters and experiential activities. Activities for raising awareness of diversity

Our first goal as language teachers is always to encourage our learners to make use of their developing language. Giving them a genuine communicative purpose and making it personal to them are two good ways of achieving this. For students beginning their journey to greater self-awareness, teachers could devise an inventory of learning skills for them to rate themselves on. This could include items such as ‘I keep my notes in order’, ‘I always make a note of homework and the date it should be done’ or whatever is appropriate to their level. Students could rate themselves privately, but then discuss with other students which ones they find most challenging, exchanging tips about how they could improve these aspects of learning. From these discussions, it will probably become clear that some students have already got good study strategies in place, even if some of them seem a little unusual. Revisiting the checklist later in the course helps learners to reflect on how they have improved and what they still need to work on. Students could work in small groups to create class surveys and explore how other members of the class like to work. Each group could take a topic, such as ‘learning vocabulary’, ‘writing’ or ‘grammar practice’, create a checklist or a short interview schedule and then gather the information from their peers. When they have gathered and sorted the data, they could present to the class what the most common/ ingenious/effective strategies and methods might be. The ensuing discussion will quite probably reveal the diversity in the group, and the hidden talents that some students bring to their learning. Exploration of learning strategies could also be embedded into a board game, a letter-writing activity (perhaps letters to an academic ‘agony aunt/uncle’) or even a game of bingo. For more ideas, see Anderson (2017) and Smith (2017). Making use of materials that include a diverse range of characters is another great way of initiating discussion and raising awareness of the issues. There may be no explicit mention made in the text of this diversity, thereby sending the implicit message that this is just how the world is. Students may see characters that they can relate to more easily, and feel more included generally. Other materials, such as the ‘Adventures on Inkling Island’ comic strips (Smith, 2018), explicitly showcase the daily challenges and talents of neurodiverse people, demonstrating that being different can be a strength in some situations. A powerful way of enabling people to understand how it might feel to be in the minority on a daily basis, whether in terms of physical abilities or cognitive function, is to set up experiential activities which challenge the participants to perform unusual tasks in conditions that make their usual way of working impossible. As well as being a fun way of introducing the topic for further discussion, these activities are usually very memorable and drive home the message that – in the vast majority of cases – lack of success in academic tasks is not due to laziness or stupidity. Conclusion

Raising awareness of hidden aspects of diversity in the group does not demand that individuals publicly identify their characteristics (e.g. ‘Hands up if you’re dyslexic!’). Rather, it is about creating an environment where people could safely share that information if they felt it was relevant to the discussion. Most importantly from a language teaching perspective, a classroom community that is aware of and embraces its own diversity is likely to engender more productive learning. In addition, awareness-raising activities could enable some individuals to understand themselves better, and so adapt their learning strategies to become more effective and efficient learners. This self-awareness can also lead to enhanced self-esteem, sustained motivation and, ultimately, success.

Anderson, J (2017) ‘Peer-needs Analysis: Sensitising learners to the needs of their classmates’. English Teaching Professional.

Smith, AM (2018) Adventures on Inkling Island. Morecambe: ELT well.

Smith, AM (2017) Raising Awareness of SpLDs. Morecambe: ELT well.

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

All Teachers Are Language Teachers: Celebrating Linguistic Diversity in the Classroom

06/07/23 | by Joseph A. Pearson, M.S.Ed.

In today’s diverse and interconnected world, classrooms are filled with students from various linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Regardless of the subject area of grade level, educators must equip themselves with the knowledge and skills necessary to support students with diverse linguistic needs. In this blog post, we will delve into the importance of embracing linguistic diversity and discuss how teachers can enhance their abilities to create inclusive learning environments. Ultimately, all teachers are language teachers with the responsibility to support multilingual learners.

In May of 2023, educational leaders from Moreland University engaged in a comprehensive discussion on teaching multilingual learners. I was joined by our Chief Academic Officer Dr. Kerri Valencia and Director of Research and Data Analytics Dr. Daphne Moriel de Cedeño, along with two esteemed faculty members, Barry Fargo, M.Ed. and Dr. Adam Morgan in our webinar, “Artificial Intelligence and Inclusive Education: Teaching Multilingual Learners in 2023-24 and Beyond.” Together we explored powerful ways educational technology and artificial intelligence (AI) can help teachers personalize learning and innovate lessons to equitably promote language acquisition. By highlighting best practices, inclusive strategies, and tools to support multilingual students in the evolving landscape of educational technology, the webinar provides valuable insights for educators seeking to create inclusive and responsive learning environments.

Let’s explore the ideas and perspectives shared by the panelists in this webinar. To encourage creating inclusive learning environments, panelists offer valuable insights on the role of teachers as facilitators of language acquisition and advocates for multilingual learners. Each panelist brings unique expertise to the discussion on why all teachers are language teachers.

Dr. Daphne Moriel De Cedeño stresses the importance of language acquisition skills for all students, stating, “All teachers are teachers of multilingual learners because all students are lifelong language learners.” Teachers must develop students’ language skills in every classroom, regardless of whether students are learning their first or fifth language. Strategies to develop students’ language include explicitly teaching vocabulary, providing sentence frames to support communication, integrating culturally relevant learning materials, and creating a safe classroom climate for language learning. When teachers support language learning in instruction, they promote culturally rich learning with, “…both windows and mirrors into the lives of diverse people.”

Educators can create an environment that fosters the cognitive, social, emotional, and linguistic growth of their students by reflecting on their own language use in the classroom. Barry Fargo, M.Ed. highlights the capacity and responsibility that teachers possess in supporting the holistic development of multilingual learners by developing their own metalinguistic awareness : “A great place for teachers to start to become prepared to teach multilingual learners is to grow their own metalinguistic awareness by reflecting on their language use in the classroom.” Understanding that all teachers are language teachers, according to Barry, is fundamental to cultivating an equitable, inclusive, and supportive learning atmosphere.

Dr. Kerri Valencia speaks to the role of technology in the linguistically diverse classroom. She recommends, “In terms of technology, it’s critical to use technology as a tool and not a crutch. Just as we need to teach through an additive lens towards our students, we need to have the same approach to technology.” She also underscores the significance of ongoing professional development, reflection, and adaptation of curriculum to meet the needs of linguistically diverse learners. One way that teachers can support multilingual learners is by honoring students’ first languages and incorporating them into the learning process. Allowing students to engage in multilingual communication through inclusive instructional strategies including translanguaging helps foster engaging environments that celebrate student identities. Language learning is universal, and teachers should value the linguistic diversity within their classrooms.

Finally, Dr. Adam Morgan emphasizes the importance of student-centered learning in supporting multilingual learners. Highlighting the impact of a student-centered approach, he shares, “Professional development and experience are essential to supporting multilingual learners, but having a laser-like focus on the student will enable you to meet their needs regardless of language and cultural barriers.” By focusing on the individual needs and strengths of each student, educators can effectively address language and cultural differences and ensure every student receives the support successful language acquisition.

These perspectives shed light on the integral role teachers of all subject areas and grade levels play in fostering language acquisition and supporting multilingual learners. By embracing students’ diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, reflecting on their instructional practices, and continuously seeking professional growth, educators promote inclusion and empower all students to thrive. In this way, educators can appreciate diversity within their classrooms and celebrate the rich tapestry of linguistic backgrounds.

M.Ed. Teaching Multilingual Learners

At Moreland University, we understand the importance of equipping teachers with the necessary skills to teach multilingual learners effectively. Our Master’s Degree in Education (M.Ed.) with a focus on Teaching Multilingual Learners is designed to prepare educators to meet the unique needs of culturally and linguistically diverse student populations. Through this program, educators delve into fundamental concepts of language, language development, and culturally-linguistically diverse populations. They learn pedagogical principles and approaches to integrate language instruction through a socio-cultural lens across various domains of linguistic development.

Educators acquire practical strategies to apply theories and methods for grammar and vocabulary in diverse educational contexts. The curriculum places particular emphasis on assessing and providing feedback to learners, as well as developing strategies for building a language-supported classroom. With our M.Ed. program, educators can enhance their expertise and empower themselves to create inclusive learning environments that foster the linguistic development of multilingual learners.

Embracing linguistic diversity is essential for teachers in the modern educational landscape. All educators should be equipped, enabled, and empowered to teach students with diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. As teachers, we play a crucial role in celebrating and supporting the rich diversity present in our classrooms. Through programs like Moreland University’s M.Ed. Teaching Multilingual Learners, educators can expand their knowledge and skills, making a positive impact on the educational journey of their students.

Remember, all teachers are language teachers who can create responsive and inclusive learning environments where multilingual students can thrive!

Additional Reading

March 15, 2023

Here’s How ChatGPT Thinks You Should Use ChatGPT in Schools

Impact of AI on education. The response from ChatGPT aligns with what we’ve heard from educators. In classrooms, the impact of AI is already being felt. We recently spoke with Moreland University

December 7, 2020

Resourceful Problem Solving in Online Special Education

Five Moreland University instructors share accounts of supporting students with special needs during COVID-19 Special Education has been impacted more severely than almost any other educational sector due to COVID-19. […]

May 25, 2022

Summer 2022 Data-Driven Professional Development

Moreland University’s mission is to teach teachers around the world to be resourceful problem-solvers and tech-savvy educators through an online, collaborative, activity- based learning system designed for tomorrow’s students in […]

©2024 MORELAND UNIVERSITY. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy & Terms of Use

Teachers Dread PD. Here’s How One School Leader Made It Engaging

- Share article

On most days, Courtney Walker, the assistant principal at Carrollton High School in Carrollton, Ga., doesn’t make it too far down her to-do list. That’s because she’s always adjusting the school’s master schedule to make room for new learning opportunities for students and teachers.

Walker joined the school in 2019 as an assistant principal for attendance and assessment, but quickly developed a “passion” for creating learning pathways for the 100 teachers in her school, which serves about 1,700 students.

“Educators are one of the largest group of stakeholders [in school], and they’re experts in what they do. They should have a voice in what kind of professional learning they receive,” Walker said in an interview with Education Week.

With her leadership team, which consists of her principal, other assistant principals, and the student dean, Walker has created five different personal learning pathways for teachers that guide their professional development for the year, in a structure that mirrors how high school students choose career pathways.

Teachers take a baseline assessment, choose an area of instruction they want to work on, and attend four sessions over a year to learn and practice their new skills. The pathways are run by expert teachers at the school, a model that favors peer learning over one-size-fits-all lectures by outside experts.

Many teachers dislike PD. Too much of it isn’t customized or relatable. In a nationally representative survey of over 1,400 teachers conducted in October 2023, EdWeek found that almost half of the respondents said the PD they are required to take is irrelevant and not connected to their most pressing needs. By contrast, 41 percent of the more than 650 school leaders surveyed as part of the same effort, said the PD they provided was “very relevant.”

There’s a middle ground here, and leaders like Walker are trying to build on it. Her efforts appear to have borne fruit. Teacher resignations and retirements at the school are back to pre-pandemic levels, after doubling in the 2021-22 school year. And while it’s notoriously hard to connect student learning directly to teacher PD, student outcomes on state assessments in subjects like American literature, U.S. history, and biology, have improved.

Walker’s efforts were recognized recently at a gathering of assistant principals from across the country, where she was named the National Assistant Principal of the Year. Here’s what Walker said about the connection between good PD and meeting a school’s goals.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was your transition like from educator to administrator?

Working with kids is totally different from working with adults. I used to be an elementary school teacher. Adults approach professional learning very differently from students learning in a classroom. That was something I really had to work through. And in moving from the classroom setting to administration, I realized that I had to present [professional] learning that looks authentic to educators, and something that they are vested in.

With students, they’re easier in terms of implementing change, because they’re pretty open and excited. But a lot of the educators are veteran, and they’re a lot older than I am, and they’ve got a lot of expertise in their field. I wanted to respect that.

My job was to figure out how to help dial in their gifts and talents, and push them toward things they are passionate about. I don’t ever want to assume that I know what they need, because they know the needs of their students.

How did you include educator voices in your PD?

The professional learning pathways for our teachers are similar to the career pathways we’ve created for our students. Teachers self-identify areas for growth, and they attend professional learning that directly addresses their need. We wanted teachers to lead this learning.

So, we gave them a structure of five pathways of learning, which were linked to our teacher-evaluation standards and district initiatives.

[A pathway could read something like: “increasing student ownership over learning through self-assessments,” according to a presentation Walker shared.]

All teachers took a needs-based assessment at the beginning of the process, and within two years, were able to attend a training that was their first or second choice.

A teacher stays with a pathway all year long, but the difference is that you’re meeting in small groups of four or five, instead of a big 40-person training. In a meeting, teachers from different disciplines learn strategies, roll them out, and then report back on how they’re working.

What about PD on specific subjects?

In parallel to the schoolwide learning pathways, we also have common course teams that meet every week. They look at student data within their subject, what instructional strategies were adopted, and drill down to what each individual student needs.

It’s running both ways, right? You have teachers of the same content working together. And then you’re looking much more broadly, across the building and across curriculums, about strategies that are beneficial.

The third area of work are “data digs” we do three times a year to zoom out and check if we’re making progress toward our school’s goals.

Teachers have a lot on their plates. How do you encourage them if their interest in the PD is flagging?

I give teachers time throughout the school year to reflect on which of their practices are working. It’s important to prompt or coach them in that reflection process. Making time for this is important, so we have a 90-minute planning block for these pathway meetings four times a year.

We observe their classroom for strategies that they discussed with peers in their pathway session. If they’re supposed to use self-assessments and checklists in the classroom, then we’re looking for that. It’s an opportunity to give feedback and say, hey, I noticed that you had students self-assess on this skill and I think it went well. That connection between teacher reflection and administrator feedback is critical. It’s also an opportunity to push them when they need to see things from a different perspective.

One of the things that our teachers asked for this year was to implement peer observations. They wanted to watch another teacher in action. One of our math teachers watched an AP Environmental Science class to observe how questions were being framed and asked.

What is the role you played specifically in making this happen?

When we started to do PD this way, we needed to have a structure in place to be able to support this. I created the framework, our five pathways [of learning], analysis protocols for our teams, which meant making agendas, meeting minutes, and assigning roles in the teams. And then I’ve worked very closely with all the team leaders to support them. I do monthly touch points to make sure it’s being rolled out. But teachers are the ones driving the training.

Do you miss teaching?

Oh yeah! This year, some of our English teachers let me teach some lessons in their classrooms. There’s nothing quite like it.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- People Directory

- Safety at UD

- Campus & Community

- Nation & World

- Culture & Society

For the Record, Friday, April 12, 2024

Article by UDaily Staff April 12, 2024

University of Delaware community reports new presentations, awards and publications

For the Record provides information about recent professional activities and honors of University of Delaware faculty, staff, students and alumni.

Recent presentations, awards and publications include the following:

Presentations

On April 7, Margaret Stetz , Mae and Robert Carter Professor of Women's Studies and professor of humanities, was an invited participant in the online interdisciplinary research seminar sponsored by Delaware Valley British Studies, which brings together faculty and doctoral students in the mid-Atlantic region. The topic of the most recent meeting was the British West Indies in the late 1830s, during the period of mandatory "apprenticeship" for the formerly enslaved population.

Awards

Bema Amponsah , academic advisor in University Studies, was recently awarded the NACADA Region 2 Excellence in Advising - New Advisor Certificate of Merit. This award recognizes individuals who have demonstrated qualities associated with outstanding academic advising of students and who have served as an advisor for a period of at least one but no more than three years. Amponsah was recognized at the Regional Conference on April 4 in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Nicole Rehbach , academic advisor II in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, was recently awarded the NACADA Region 2 Webinar Scholarship. This scholarship recognizes an individual who seeks professional development through the use of a NACADA webinar and is committed to arranging for others from their institution to participate in the webinar as well. Rehbach was able to share the webinar titled “Accessible Language for Better Advising: Inviting Dialogue for Student Success” with the Advisor Network on campus on March 14. She was recognized for her scholarship at the Regional Conference on April 4 in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Thomas Ilvento , professor in the Department of Applied Economics and Statistics, received the American Statistical Association (ASA) 2024 Philadelphia Chapter College Teaching Excellence Award for College or University Educator. This award recognizes local educators who have consistently inspired within their students a love and passion for statistics. Recipients are selected based upon sustained commitment to the profession of teaching statistics and impact on their students, including learning statistical content and their views about the discipline, both in and out of the classroom.

Dustin Frohlich , processing and collections management archivist at the UD Library, Museums and Press, won third place in the Mid Atlantic Regional Archives Conference’s Finding Aid Awards for his work on the Shipley-Bringhurst-Hargraves Family Papers finding aid . The award recognizes finding aids with outstanding content that enable researchers to more effectively access and use archival materials.

Annie Johnson , associate university librarian for publishing, preservation, research and digital access at the UD Library, Museums and Press, was elected to the board of the Library Publishing Coalition (LPC). The LPC extends the impact and sustainability of library publishing and open scholarship by providing a professional forum for developing best practices and shared expertise. Johnson’s term runs through June 2027.

Deborah Steinberger , associate professor of French in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, was awarded a three-year, $18,000 French in Higher Education innovation grant from the French Embassy and the Albertine Foundation to create an internship program for students of French at the graduate and undergraduate levels.

Publications