What Will Your Life Be Like in 2050?

Will it be just like today, but electric? Or will it be very different?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Lloyd-Alter-bw-883700895c6844cf9127ab9289968e93.jpg)

- University of Toronto

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HaleyMast-2035b42e12d14d4abd433e014e63276c.jpg)

- Harvard University Extension School

Hulton Archives/ Getty Images

- Environment

- Business & Policy

- Home & Design

- Current Events

- Treehugger Voices

- News Archive

New Scientist magazine's chief reporter Adam Vaughan recently published "Net-zero living: how your day will look in a carbon-neutral world ." Here, he imagines what a typical day would be like in the future—through the lens of Isla, "a child today, in 2050"—after we've cut carbon emissions. Vaughan says “most of us are lacking a visualization of what life will be like at net zero” and acknowledges the writing is fiction: "By its nature, it is speculative – but it is informed by research, expert opinion, and trials happening right now.”

Isla lives in the south of the United Kingdom—will it still be a united kingdom in 2050?—and her life looks pretty much like life does today: She has a house, a car, a job, and a cup of tea in the morning. There are wind turbines, great forests, and giant machines sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. It all sounds like a green and pleasant land, but it didn’t sound like the future to me.

It’s an interesting exercise, imagining what it will be like in 30 years. I thought I would give it a try: Here is some speculative fiction about Edie, living in Toronto, Canada in 2050.

Edie’s alarm goes off at 4:00 a.m. She gets up, folds up the bed in the converted garage in an old house in Toronto that is her apartment and workshop, and makes herself a cup of caffeine-infused chicory; only the very rich can afford real coffee 1 .

She considers herself to be very lucky to have this garage in what was her grandparents’ house. The only people who live in houses these days either inherited them or are multi-millionaires from all over the world, but especially from Arizona and other Southern states 2 , desperate to move Canada with its cooler climate and plentiful water and can afford the million-dollar immigrant visa fee.

She hurries to prepare her pushcart, actually a big electric cargo bike, filling it with the tomatoes, and preserves and pickles she prepared with fruits and vegetables she bought from backyard gardeners. Edie then rides it downtown where all the big office buildings have been converted into tiny apartments for climate refugees. The streets downtown look very much like Delancey Street in New York looked like in 1905, with e-pushcarts lining the roads where cars used to park.

Edie is lucky to be working. There are no office or industrial jobs anymore: Artificial Intelligence and robots took care of that 3 . The few jobs left are in service, culture, craft, health care, or real estate. In fact, selling real estate has become the nation’s biggest industry; there is a lot of it, and Sudbury is the new Miami.

Fortunately for Edie, there is a big demand for homemade foods from trustworthy sources. All the food in the grocery stores is grown in test tubes or made in factories. Edie sells out and rides home in time for siesta. There may be lots of electricity from wind and solar farms, but even running tiny heat pumps 4 for cooling is really expensive at peak times. The streets are unpleasantly hot, so many people sleep through the midday.

She checks the balance in her Personal Carbon Allowance (PCA) account to see if she has enough to buy another imported battery for her pushcart e-bike 5 after her nap; batteries have a lot of embodied carbon and transportation emissions and might eat up a month’s worth of her PCA. If she doesn’t have enough then she will have to buy carbon credits, and they are expensive. She sets her alarm for 6:00 p.m. when the streets of Toronto will come alive again on this hot November day.

The New Scientist article is illustrated with an image showing people walking and biking, turbines spinning, electric trains running, with kayaks, not cars. This is not an uncommon vision: There are many who suggest we just have to electrify everything and cover it all with solar panels and then we can keep on with the happy motoring.

I am not so optimistic. If we don't keep the global rise in temperature to under 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) then things are going to get messy. So this story was not just a speculative fantasy but based on previous writing about the need for sufficiency and worries about the embodied carbon of making everything , with some notes from previous Treehugger posts:

- Thanks to climate change, "Coffee plantations in South America, Africa, Asia, and Hawaii are all being threatened by rising air temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns, which invite disease and invasive species to infest the coffee plant and ripening beans." More in Treehugger.

- "Dwindling water supplies and below-average rainfall have consequences for those living in the West." More in Treehugger.

- "We're witnessing the Third Industrial Revolution Playing out in real time." More in Treehugger.

- Tiny heat pumps for tiny spaces are probably going to be common. More in Treehugger.

- Electric cargo bikes will be a powerful tool for low-carbon commerce. More in Treehugger.

- 2022 in Review: The Year E-Cargo Bikes Took Over

- This Mass Timber Passivhaus Rental Building Is Perfect for Active Adults

- Building a Sustainable Condo Today Involves Designing for the Future

- Five, Just Five, Solutions to Roll Back Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- A Car Ban Will Improve the State of the Climate, But Is It Ableist?

- Nobody's Perfect, and You Don't Have to Be

- What's the Right Way to Build in a Climate Crisis?

- 2021 in Review: The Year in Tiny Living

- 2021 in Review: The E-Bike Revolution Hits the Streets

- Two Views of the Future of the Office

- Is Any Party in the Canadian Election Taking Climate Seriously?

- The Rise of Tall Wood

- Best of Green Awards 2021: Eco Tech

- The Future of Main Street, Post-Pandemic

- How We Get Around Determines What We Build, and Also Determines Much of Our Carbon Footprint

- Best of Green Awards 2021: Sustainable Travel

An unsettling peek into the reality of life in 2050

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Rather than just imagine the future, what if we could walk around in it? In an installation, designer Anab Jain invites visitors to enter an apartment in the middle of the 21st century.

What will our world look like in 30 years?

Many of us fear the worst. Today, violent storms and wildfires are ripping through the world; we’re rapidly losing crop biodiversity ; and large numbers of people are already suffering from chronic food insecurity . Any of these situations, it seems, could spiral out of control over the coming decades.

But why just worry about the future when you can step into it? Anab Jain , a TED Fellow and the cofounder of London future-design studio Superflux (watch her TED Talk: “ Why we need to imagine different futures ”), builds potential tomorrows that people can experience firsthand right now — and gain insights that we could apply to take control of our destinies. “A lot of us in the West don’t think climate change is our problem; we always think about it as somebody else’s problem,” Jain says. “It’s too big and too difficult to deal with. We take in the data, but we don’t apply it to what this means for our own lives.” In an installation called Mitigation of Shock , the Superflux team aim to show us what our lives might be like if we do nothing to combat global warming, by taking us into a flat in London — in the year 2050. Let’s step in ….

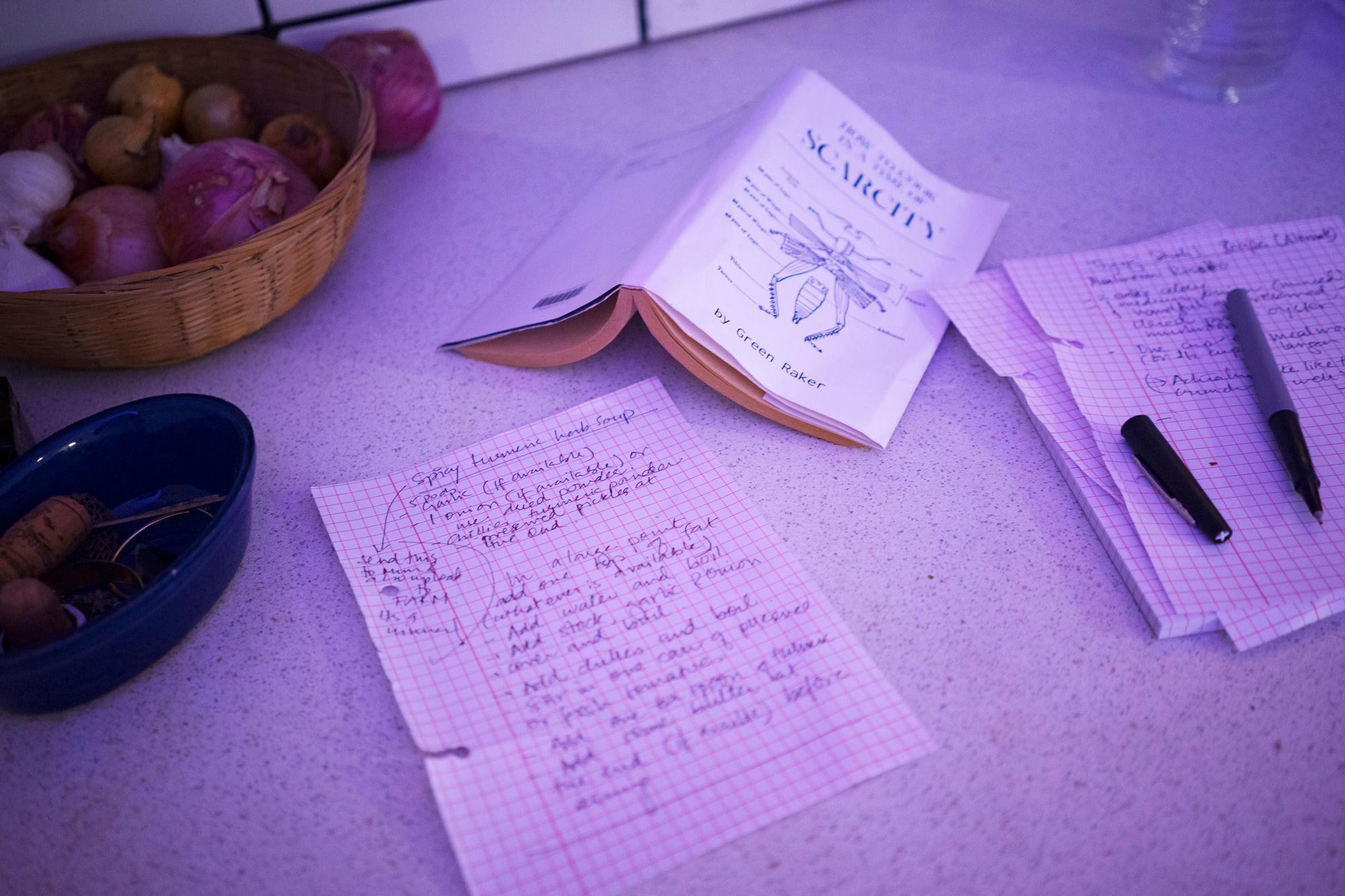

A door marked “64” takes you into a small apartment. There’s a couch that looks like it was just sat on. Shelves contain a family’s worth of books, toys and gadgets, and a coffee table holds a partial cup of coffee and a half-eaten cookie. Beyond the dining room table is a kitchen counter with recipe books; shelves overhead are full of containers of home-preserved food. The radio is tuned to the news. So far, it’s not that different from many apartments you could find in Europe today.

But as you look around, your gaze falls on a newspaper on the coffee table. The headline reads “Worldwide crop failures in 2049: How will we eat?” You hear the radio announcer talking about eco-terrorists, the hijacking of supermarket trucks, extreme weather and poor air quality. Flip through a ledger on the dining room table, and you’ll see a record of the family’s experiments in growing food, next to vials of carefully labeled seeds. The jars of preserves on the shelves turn out to be marked with the month, year and place where the food was foraged. Scan the cookbooks on the shelves, and you’ll see titles like How to Cook in Scarcity and, more alarmingly, Pets as Protein . Recipes tacked to the kitchen wall offer ways to prepare mealworms and foxes.

Turning the corner into the next room, you realize that you’ve wandered into a factory of sorts. The humming space is bathed in a fluorescent glow, and the industrial shelving units are filled with boxes of plants growing in a swirling fog circulated by tiny fans. Oyster mushrooms are being cultivated on the top shelves, along with smaller plastic containers full of live mealworms. As you peer out a window above a table brimming with a jumble of hardware, you can see storm clouds darkening the sky as people squabble over food in the streets.

“We created this living space to imagine what we might need to live in a world where some of the most drastic impacts of climate change have already occurred,” says Jain. Mitigation of Shock — which is now on view at Barcelona’s Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) — is part of an exhibition called “After the End of the World,” which envisions the future toll of centuries of human impact and negligence. The installation takes what’s happening now and fast-forwards the action in one specific direction. In that way, it’s less a calculated prediction than an educated extrapolated guess of the future.

The scenario is fictionalized, as are the recipe books (thank goodness). However, the solutions that Superflux co-founder Jon Ardern and the studio team have built are very real. The plants on the shelves are being fed using fogponics and LED lights, all controlled using Arduinos, or microcontroller units. “The Arduinos are connected to ultrasonic sensors in a box of nutrient-rich water,” says Jain. “When the Arduino tells the sensor to go off, it converts the water into a nutrient mist that is dispersed to the plants’ roots by using computer fans.”

This is only one possible future of many, Jain hastens to add. “There could be others — worse or better,” she says. Right now, many people in developed nations can go to the supermarket and buy whatever they fancy, from Peruvian avocados to Kenyan green beans. But the way things are going, there’s a chance that this casual abundance will start to vanish. After visiting the installation, the Superflux team hopes that people walk away with a more visceral idea of what living with food insecurity might look like.

They also want people to realize we already have some of what we need to adapt. “Fogponics and hydroponics already are in use, although people currently see them as a hobby. Foraging, home preserving, growing food on allotments, and local food networks exist, too, but not as a form of survival,” says Jain. “We made the food production system using off-the-shelf stuff that we bought and hacked together and coded. The question then becomes, what if your life—your family’s life—depended on it?”

The apartment is also cluttered with discarded gadgets. There’s an unused surveillance camera, something that resembles a Nest smart thermostat, and a smart cup that will tell you when your drink is hot enough. “There’s also a fridge with a smart panel that tells you it’s run out of milk, but there’s nowhere to buy milk,” says Jain. “In our scenario, these things are now irrelevant — detritus, just lying around. We wanted to hint at the shiny future that is being predicted by tech companies and corporations. The lived reality will be somewhere in the middle.”

Jain has been intrigued by the response from visitors so far. “A lot of people have told me that they feel freaked out by it,” she says. “And some have said, ‘This feels totally normal — it’s already happening.’ It’s very different, depending on your emotional connection to what’s happening around you. How much time have you spent absorbing and internalizing the information we’ve been given and the changes that have already occurred?” Jain’s best-case scenario for the installation would be for folks leave wanting to make some behavioral shift. “We’re still buying from supermarkets; most of us are still not feeling that shortage, insecurity or vulnerability,” she says. “I think the news is like a fire outside the window. You close the window if you think the fire’s going to be bad. But what if the fire starts coming in through the window? That’s the feeling we want to give people: that it’s happening now, but we also have the tools, strategies and, most importantly, the imagination for whatever comes next.”

Mitigation of Shock was on exhibit at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona through April 29, 2018.

About the author

Karen Frances Eng is a contributing writer to TED.com, dedicated to covering the feats of the wondrous TED Fellows. Her launchpad is located in Cambridge, UK.

- art and design

- TED Fellows

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

11 book and music recommendations that will ignite your imagination

8 mouthwatering TV shows and movies about the future of food and our planet

9 must-watch adventure, fantasy and romance movies you didn’t know were about climate

Gallery: During lockdown, this street photographer created a vibrant, surreal world starring his parents

Leather is bad for animals and the planet — but what if we made it in a lab?

Gallery: 11 otherworldly photos of land, sea and sky at night

24/7 darkness, polar bears and ice everywhere: 8 striking photos of Arctic researchers at work

Could tiny homes be the adorable, affordable and sustainable housing that our planet needs?

6 ways to give that aren't about money

Let’s stop calling them “soft skills” -- and call them “real skills” instead

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

The 7 types of people you need in your life to be resilient

There’s a know-it-all at every job — here’s how to deal

Mental time travel is a great decision-making tool -- this is how to use it

Gallery: Using design to build a community

Skyscrapers are boring: One architect against the tyranny of the tower

Take an intentional walk -- and experience your community in a whole new way

What if we did everything right? This is what the world could look like in 2050

According to studies, these accumulations of ice are thawing at a pace so fast that they could disappear in 25 years. Image: REUTERS/Marcos Brindicci (ARGENTINA) - GM1E5CG0XS301

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Christiana Figueres

Tom rivett-carnac.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Climate Change is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, climate change.

This is an extract from the World Economic Forum's Book Club pick for March 2020: The Future We Choose by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac. Join our Book Club to discuss.

The World We Are Creating

It is 2050. Beyond the emissions reductions registered in 2015, no further efforts were made to control emissions. We are heading for a world that will be more than 3 degrees warmer by 2100.

The first thing that hits you is the air.

The World Economic Forum launched its official Book Club on Facebook in April 2018. Readers worldwide are invited to join and discuss a variety of books, both fiction and non-fiction. It is a private Facebook group dedicated to discussing one book every month.

Each month, we announce a new book on our social media channels. We then publish an extract and begin a chapter-by-chapter discussion with group members. Selected comments and questions are sent to the author, who in return sends us a video response.

Unlike other book clubs, the group features the direct involvement of the authors, giving you - our global audience with members all around the globe - a chance to directly connect with some of the most influential thinkers and experts in the world.

We have featured authors such as Steven Pinker, Elif Shafak, Yuval Noah Harari, and Melinda Gates.

You can join the Book Club here .

Follow us on Twitter here .

Follow us on Instagram here .

In many places around the world, the air is hot, heavy, and depending on the day, clogged with particulate pollution. Your eyes often water. Your cough never seems to disappear. You think about some countries in Asia, where out of consideration sick people used to wear white masks to protect others from airborne infection. Now you wear a daily mask to protect yourself from air pollution. You can no longer walk out your front door and breathe fresh air: there is none. Instead, before opening doors or windows in the morning, you check your phone to see what the air quality will be. Everything might look fine— sunny and clear— but you know better. When storms and heat waves overlap and cluster, the air pollution and intensified surface ozone levels make it dangerous to go outside without a specially designed face mask (which only some can afford).

Southeast Asia and Central Africa lose more lives to filthy air than do Europe or the United States. There few people work outdoors anymore, and even indoors the air tastes slightly acidic, making you feel nauseated throughout the day. China stopped burning coal ten years ago, but that hasn’t made much difference in air quality around the world because you are still breathing dangerous exhaust fumes from millions of cars and buses everywhere. China has experimented with seeding rain clouds— the process of artificially inducing rain— hoping to wash pollution out of the sky, but results are mixed. Seeding clouds to artificially create more rain is difficult and unreliable, and even the wealthiest countries cannot achieve consistent results. In Europe and Asia, the practice has triggered international incidents because even the most skilled experts can’t control where the rain will fall, never mind that acid rain is deleterious to crops, wreaking havoc on food supply. As a result, crops are increasingly grown under cover to protect them from the weather, a trend that will only get stronger.

Our world is getting hotter. Over the next two decades, projections tell us that temperatures in some areas of the globe will rise even higher, an irreversible development utterly beyond our control. The world’s ecosystems have stopped absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and are, on balance, emitting it. Oceans, forests, plants, trees, and soil had for many years absorbed half the carbon dioxide we spewed out. Now there are few forests left, most of them either logged or consumed by wildfire, and the permafrost is belching greenhouse gases into an already overburdened atmosphere.

The increasing heat of the Earth is suffocating us, and in five to ten years, vast swaths of the planet will be uninhabitable. By 2100, Australia, North Africa, and parts of the western United States might be entirely abandoned. Now everyone knows what the future holds for their children and grandchildren: tipping point after tipping point has been reached until eventually there will be no more civilization. Humans will be cast to the winds again, gathering in small tribes, hunkered down and living on whatever patch of land might sustain them.

The planet has already reached several such tipping points. First was the vanishing of coral reefs. Some of us still remember diving amid majestic coral reefs, brimming with multicolored fish of all shapes and sizes. Corals are now almost gone. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia is the largest aquatic cemetery in the world. Efforts have been made to grow artificial corals farther north and south from the equator where the water is a bit cooler, but these efforts have failed, and marine life has not returned. Soon there will be no reefs anywhere— it is only a matter of a few years before the last 10 percent dies off.

The second tipping point was the melting of the ice sheets in the Arctic. There is no summer Arctic sea ice anymore because warming is worse at the poles— between 6 and 8 degrees higher than other areas. The melting happened silently in that cold place far north of most of the inhabited world, but its effects were soon noticed. The Great Melting was an accelerant of further global warming. The white ice used to reflect the sun’s heat, but now it’s gone, so the dark sea water absorbs more heat, expanding the mass of water and pushing sea levels even higher. More moisture in the air and higher sea surface temperatures have caused a surge in extreme hurricanes and tropical storms. Recently, coastal cities in Bangladesh, Mexico, and the United States have suffered brutal infrastructure destruction and extreme flooding, killing many thousands and displacing millions. This happens with increasing frequency now. Every day, because of rising water levels, some part of the world must evacuate to higher ground. Every day the news shows images of mothers with babies strapped to their backs, wading through floodwaters, and homes ripped apart by vicious currents that resemble mountain rivers. News stories tell of people living in houses with water up to their ankles because they have nowhere else to go, their children coughing and wheezing because of the mold growing in their beds, insurance companies declaring bankruptcy leaving survivors without resources to rebuild their lives. Contaminated water supplies, sea salt intrusions, and agricultural runoff are the order of the day. Because multiple disasters are always happening simultaneously in every country, it can take weeks or even months for basic food and water relief to reach areas pummeled by extreme floods. Diseases such as malaria, dengue, cholera, respiratory illnesses, and malnutrition are rampant.

Now all eyes are on the western Antarctic ice sheet. If and when it disappears, it could release a deluge of freshwater into the oceans, raising sea levels by over five meters. Cities like Miami, Shanghai, and Dhaka will be uninhabitable—ghostly Atlantises dotting the coasts of each continent, their skyscrapers jutting out of the water, their people evacuated or dead.

Those around the world who chose to remain on the coast because it had always been their home have more to deal with than rising water and floods— they must now witness the demise of a way of life-based on fishing. As oceans have absorbed carbon dioxide, the water has become more acidic, and the pH levels are now so hostile to marine life that all countries have banned fishing, even in international waters. Many people insist that the few fish that are left should be enjoyed while they last— an argument, hard to fault in many parts of the world, that applies to so much that is vanishing.

As devastating as rising oceans have been, droughts and heatwaves inland have created a special hell. Vast regions have succumbed to severe aridification followed by desertification, and wildlife has become a distant memory. These places can barely support human life; their aquifers dried up long ago, and their groundwater is almost gone. Marrakech and Volgograd are on the verge of becoming deserts. Hong Kong, Barcelona, and Abu Dhabi have been desalinating seawater for years, desperately trying to keep up with the constant wave of immigration from areas that have gone completely dry.

The Sahara Desert, which was once contained in Africa, now extends to Europe, into areas of Spain, Greece, and southern France. Extreme heat is on the march. If you live in Paris, you endure summer temperatures that regularly rise to 44 degrees Celsius (111 degrees Fahrenheit). This is no longer the headline-grabbing event it would have been thirty years ago. Everyone stays inside, drinks water, and dreams of air conditioning. You lie on your couch, a cold wet towel over your face, and try to rest without dwelling on the poor farmers on the outskirts of town who, despite recurrent droughts and wildfires, are still trying to grow grapes, olives, or soy— luxuries for the rich, not for you.

You try not to think about the 2 billion people who live in the hottest parts of the world, where, for upward of forty-five days per year, temperatures skyrocket to 60 degrees Celsius (140 degrees Fahrenheit)— a point at which the human body cannot be outside for longer than six hours because it loses the ability to cool itself down. Places such as central India are becoming uninhabitable. For a while people tried to carry on, but when you can’t work outside, when you can fall asleep only at four a.m. for a couple of hours because that’s the coolest part of the day, there’s not much you can do but leave. Mass migrations to less hot rural areas are beset by a host of refugee problems, civil unrest, and bloodshed over diminished water availability.

Inland glaciers around the world are almost gone. The millions who depended on the Himalayan, Alpine, and Andean glaciers to regulate water availability throughout the year are in a state of constant emergency: there is no more snow turning to ice atop mountains in the winter, so there is no more gradual melting for the spring and summer. Now there are either torrential rains leading to flooding or prolonged droughts. The most vulnerable communities with the least resources have already seen what ensues when water is scarce: sectarian violence, mass migration, and death.

Even in some parts of the United States, there are fiery conflicts over water, battles between the rich who are willing to pay for as much water as they want and everyone else demanding equal access to the life-enabling resource. The taps in nearly all public facilities are locked, and those in restrooms are coin-operated. At the federal level, Congress is in an uproar over water redistribution: states with less water demand what they see as their fair share from states that have more. Government leaders have been stymied on the River and the Rio Grande shrink further. Looming on the horizon are conflicts with Mexico, no longer able to guarantee deliveries of water from the depleted Rio Conchos and Rio Grande. Similar disputes have arisen in Peru, China, and Russia.

Food production swings wildly from month to month, season to season, depending on where you live. More people are starving than ever before. Climate zones have shifted, so some new areas have become available for agriculture (Alaska, the Arctic), while others have dried up (Mexico, California). Still others are unstable because of the extreme heat, never mind flooding, wildfire, and tornadoes. This makes the food supply in general highly unpredictable. One thing hasn’t changed, though— if you have money, you have access. Global trade has slowed as countries such as China stop exporting and seek to hold on to their own resources. Disasters and wars rage, choking off trade routes. The tyranny of supply and demand is now unforgiving; because of its scarcity, food is now wildly expensive. Income inequality has always existed, but it has never been this stark or this dangerous.

Whole countries suffer from epidemics of stunting and malnutrition. Reproduction has slowed overall, but most acutely in those countries where food scarcity is dire. Infant mortality is sky high, and international aid has proven to be politically impossible to defend in light of mass poverty. Countries with enough food are resolute about holding on to it.

In some places, the inability to gain access to such basics as wheat, rice, or sorghum has led to economic collapse and civil unrest more quickly than even the most pessimistic sociologists had previously imagined. Scientists tried to develop varieties of staples that could stand up to drought, temperature fluctuations, and salt, but we started too late. Now there simply aren’t enough resilient varieties to feed the population. As a result, food riots, coups, and civil wars throw the world’s most vulnerable from the frying pan into the fire. As developed countries seek to seal their borders from mass migration, they too feel the consequences. Stock markets are crashing, currencies are wildly fluctuating, and the European Union has disbanded.

As committed as nations are to keeping wealth and resources within their borders, they’re determined to keep people out. Most countries’ armies are now just highly militarized border patrols. Lockdown is the goal, but it hasn’t been a total success. Desperate people will always find a way. Some countries have been better global Good Samaritans than others, but even they have now effectively shut their borders, their wallets, and their eyes.

When the equatorial belt became mostly uninhabitable just a few years ago, you watched the news with disbelieving eyes. Undulating crowds of migrants, half a billion people, were moving north from Central America toward Mexico and the United States. Others moved south toward the tips of Chile and Argentina. The same scenes played out across Europe and Asia. Most people who lived between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn were driving or walking away in a giant band of humanity. Enormous political pressure was placed on northern and southern countries to either welcome migrants or keep them out. Some countries let people in, but only under conditions approaching indentured servitude. It will be years before the stranded migrants are able to find asylum or settle into new refugee cities that have formed along the borders.

Even if you live in areas with more temperate climates such as Canada and Scandinavia, you are still extremely vulnerable. Severe tornadoes, flash floods, wildfires, mudslides, and blizzards are always in the back of your mind. Depending on where you live, you have a fully stocked storm cellar, an emergency go-bag in your car, or a six-foot fire moat around your house. People are glued to oncoming weather reports. No one shuts their phones off at night. When the emergency hits, you may only have minutes to respond. The alert systems set up by the government are basic and subject to glitches and irregularities depending on access to technology. The rich, who subscribe to private, reliable satellite-based alert systems, sleep better.

The weather is unavoidable, but lately the news about what’s going on at the borders has become too much for most people to endure. Because of the alarming spike in suicides, and under increasing pressure from public health officials, news organizations have decreased the number of stories devoted to genocide, slave trading, and refugee virus outbreaks. You can no longer trust the news. Social media, long the grim source of live feeds and disaster reporting, is brimming with conspiracy theories and doctored videos. Overall, the news has taken a strange, seemingly controlled turn toward distorting reality and spinning a falsely positive narrative.

Everyone living within a stable country is physically safe, yes, but the psychological toll is mounting. With each new tipping point passed, they feel hope slipping away. There is no chance of stopping the runaway warming of our planet, and no doubt we are slowly but surely heading toward human extinction. And not just because it’s too hot. Melting permafrost is also releasing ancient microbes that today’s humans have never been exposed to— and as a result have no resistance to. Diseases spread by mosquitoes and ticks are rampant as these species flourish in the changed climate, spreading to previously safe parts of the planet, overwhelming us. Worse still, the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance has only intensified as the population has grown denser in the last inhabitable areas and temperatures continue to rise.

The demise of the human species is being discussed more and more— its trajectory seems locked in. The only uncertainty is how long we’ll last, how many more generations will see the light of day. Suicides are the most obvious manifestation of the prevailing despair, but there are other indications: a sense of bottomless loss, unbearable guilt, and fierce resentment at previous generations who did nothing to ward off this final, unstoppable calamity.

The World We Must Create

It is 2050. We have been successful at halving emissions every decade since 2020. We are heading for a world that will be no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer by 2100.

In most places in the world, the air is moist and fresh, even in cities. It feels a lot like walking through a forest, and very likely this is exactly what you are doing. The air is cleaner than it has been since before the Industrial Revolution.

You have trees to thank for that. They are everywhere.

It wasn’t the single solution we required, but the proliferation of trees bought us the time we needed to vanquish carbon emissions. Corporate donations and public money funded the biggest tree- planting campaign in history. When we started, it was purely practical, a tactic to combat climate change by relocating the carbon: the trees took carbon dioxide out of the air, released oxygen, and put the carbon back where it belongs, in the soil. This of course helped to diminish climate change, but the benefits were even greater. On every sensory level, the ambient feeling of living on what has again become a green planet has been transformative, especially in cities. Cities have never been better places to live. With many more trees and far fewer cars, it has been possible to reclaim whole streets for urban agriculture and for children’s play. Every vacant lot, every grimy unused alley, has been repurposed and turned into a shady grove. Every rooftop has been converted to either a vegetable or a floral garden. Windowless buildings that were once scrawled with graffiti are instead carpeted with verdant vines.

The greening movement in Spain had begun as an effort to combat rising temperatures. Because of Madrid’s latitude, it is one of the driest cities in Europe. And even though the city now has a grip on its emissions, it was previously at risk of desertification. Because of the “heat island” effect of cities— buildings trap warmth and dark, paved surfaces absorb heat from the sun— Madrid, home to more than 6 million people, was several degrees warmer than the countryside just a few miles away. In addition, air pollution was leading to a rising incidence of premature births, and a spike in deaths was linked to cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses. With a health care system already strained by the arrival of subtropical diseases like dengue fever and malaria, government officials and citizens rallied. Madrid made dramatic efforts to reduce the number of vehicles and create a “green envelope” around the city to help with cooling, oxygenating, and filtering pollution. Plazas were repaved with porous material to capture rainwater; all black roofs were painted white; and plants were omnipresent. The plants cut noise, released oxygen, insulated south- facing walls, shaded pavements, and released water vapor into the air. The massive effort was a huge success and was replicated all over the world. Madrid’s economy boomed as its expertise put it on the cutting edge of a new industry.

Most cities found that lower temperatures raised the standard of living. There are still slums, but the trees, largely responsible for countering the temperature rise in most places, have made things far more bearable for all.

Reimagining and restructuring cities was crucial to solving the climate challenge puzzle. But further steps had to be taken, which meant that global rewilding efforts had to reach well beyond the cities. The forest cover worldwide is now 50 percent, and agriculture has evolved to become more tree-based. The result is that many countries are unrecognizable, in a good way. No one seems to miss wideopen plains or monocultures. Now we have shady groves of nut and fruit orchards, timberland interspersed with grazing, parkland areas that spread for miles, new havens for our regenerated population of pollinators.

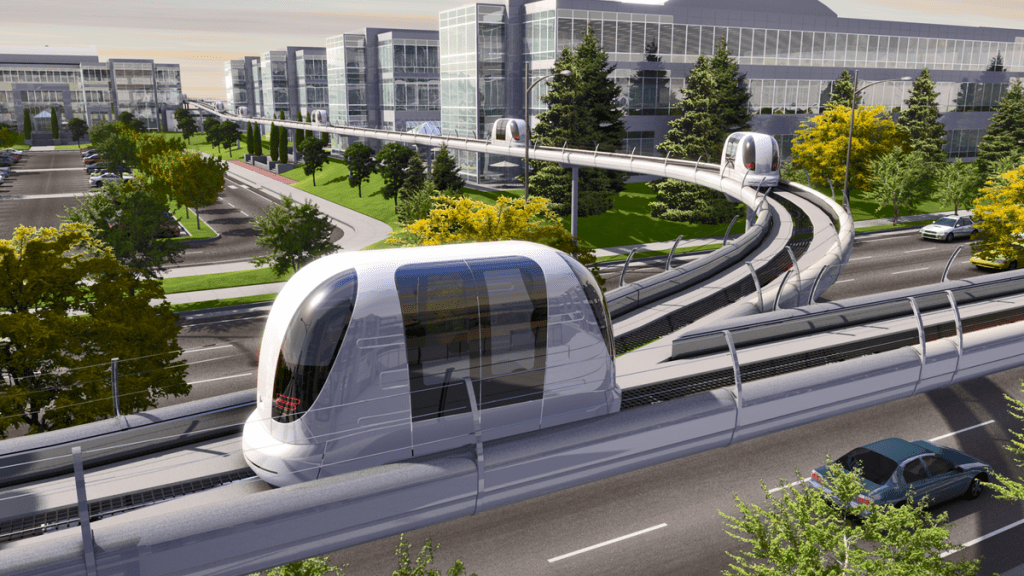

Luckily for the 75 percent of the population who live in cities, new electric railways crisscross interior landscapes. In the United States, high- speed rail networks on the East and West coasts have replaced the vast majority of domestic flights, with East coast connectors to Atlanta and Chicago. Because flight speeds have slowed down to gain fuel efficiency, passenger bullet trains make some journeys even faster and with no emissions whatsoever. The U.S. Train Initiative was a monumental public project that sparked the economy for a decade. Replacing miles and miles of interstate highways with a new transportation system created millions of jobs— for train technology experts, engineers, and construction workers who designed and built raised rail tracks to circumvent floodplains. This massive effort helped to reeducate and retrain many of those displaced by the dying fossil fuel economy. It also introduced a new generation of workers to the excitement and innovation of the new climate economy.

Running parallel to this mega public works effort was an increasingly confident race to harness the power of renewable sources of energy. A major part of the shift to net- zero emissions was a focus on electricity; achieving the goal required not only an overhaul of existing infrastructure but also a structural shift. In some ways, breaking up grids and decentralizing power proved easy. We no longer burn fossil fuels. There is some nuclear energy in those countries that can afford the expensive technology,6 but most of our energy now comes from renewable sources like wind, solar, geothermal, and hydro. All homes and buildings produce their own electricity— every available surface is covered with solar paint that contains millions of nanoparticles, which harvest energy from the sunlight, and every windy spot has a wind turbine. If you live on a particularly sunny or windy hill, your house might harvest more energy than it can use, in which case the energy will simply flow back to the smart grid. Because there is no combustion cost, energy is basically free. It is also more abundant and more efficiently used than ever.

Smart tech prevents unnecessary energy consumption, as artificial intelligence units switch off appliances and machines when not in use. The efficiency of the system means that, with a few exceptions, our quality of life has not suffered. In many respects, it has improved.

For the developed world, the wide-ranging transition to renewable energy was at times uncomfortable, as it often involved retrofitting old infrastructure and doing things in new ways. But for the developing world, it was the dawn of a new era. Most of the infrastructure that it needed for economic growth and poverty alleviation was built according to the new standards: low carbon emissions and high resilience. In remote areas, the billion people who had no electricity at the start of the twenty-first century now have energy generated by their own rooftop solar modules or by wind-powered minigrids in their communities. This new access opened the door to so much more. Entire populations have leaped forward with improved sanitation, education, and health care. People who had struggled to get clean water can now provide it to their families. Children can study at night.

Remote health clinics can operate effectively. Homes and buildings all over the world are becoming self- sustaining far beyond their electrical needs. For example, all buildings now collect rainwater and manage their own water use. Renewable sources of electricity made possible localized desalination, which means clean drinking water can now be produced on-demand anywhere in the world. We also use it to irrigate hydroponic gardens, flush toilets, and shower. Overall, we’ve successfully rebuilt, reorganized, and restructured our lives to live in a more localized way. Although energy prices have dropped dramatically, we are choosing local life over long commutes. Due to greater connectivity, many people work from home, allowing for more flexibility and more time to call their own.

We are making communities stronger. As a child, you might have seen your neighbors only in passing. But now, to make things cheaper, cleaner, and more sustainable, your orientation in every part of your life is more local. Things that used to be done individually are now done communally— growing vegetables, capturing rainwater, and composting. Resources and responsibilities are shared now. At first you resisted this togetherness— you were used to doing things individually and in the privacy of your own home. But pretty quickly the camaraderie and unexpected new network of support started to feel good, something to be prized. For most people, the new way has turned out to be a better recipe for happiness.

Food production and procurement are a big part of the communal effort. When it became clear we needed to revolutionize farms, with increased community reliance on small farms. Instead of going to a big grocery store for food flown in from hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away, you buy most of your food from small local farmers and producers. Buildings, neighborhoods, and even large extended families form a food purchase group, which is how most people buy their food now. As a unit they sign up for a weekly dropoff, then distribute the food among the group members. Distribution, coordination, and management are everyone’s responsibility, which means you might be partnered with a downstairs neighbor for distribution one week and your upstairs neighbor the next.

While this community approach to food production makes things more sustainable, food is still expensive, consuming up to 30 percent of household budgets, which is why growing your own is such a necessity. In community gardens, on rooftops, at schools, and even hanging from vertical gardens on balconies, food sometimes seems to be growing everywhere.

We’ve come to realize, by growing our own, that food is expensive because it should be expensive— it takes valuable resources to grow it, after all. Water. Soil. Sweat. Time. For that reason, the most resource- depleting foods of all— animal protein and dairy products— have practically disappeared from our diets. But the plant-based replacements are so good that most of us don’t notice the absence of meat and dairy. Most young children cannot believe we used to kill any animals for food. Fish is still available, but it is farmed and yields are better managed by improved technology.

We make smarter choices about bad foods, which have become an ever- diminishing part of our diets. Government taxes on processed meats, sugars, and fatty foods helped us reduce the carbon emissions from farming. The biggest boon of all was to our collective health. Thanks to reduced cancers, heart attacks, and strokes, people are living longer, and health services around the world cost less and less. In fact, a huge portion of the costs of combating climate change were recuperated by governments’ savings on public health.

Along with outrageous spending on health care, gasoline and diesel cars are also anachronisms. Most countries banned their manufacture in 2030, but it took another fifteen years to get the internal combustion engine off the road completely. Now they are seen only in transport museums or at special rallies where classic car owners pay an offset fee to allow them to drive a few short miles around the track. And of course, they are all hauled in on the backs of huge electric trucks.

When it came to making the switch, some countries were already ahead of the curve. Technology-driven countries such as Norway and bicycle-friendly nations like the Netherlands managed to impose a moratorium on cars much earlier. Unsurprisingly, the United States had the hardest time of all. First, it restricted their sale, and then it banned them from certain parts of cities— Extreme Low Emission Zones. Then came the breakthrough in the battery storage capacity of electric vehicles, the cost reductions that came from finding alternative materials for manufacture, and finally the complete overhaul of the charging and parking infrastructure. This allowed people easier access to cheap power for their electric vehicles. Even better, car batteries are now bi-directionally connected with the electric grid, so they can either charge from the grid or provide power to the grid when they aren’t being driven. This helps back up the smart grid that is running on renewable energy.

The ubiquity and ease of electric vehicles were alluring, but satisfaction of our appetite for speed finally did the trick. Supposedly, to stop a bad habit you have to replace it with one that is more salubrious or at least as enjoyable. At first China dominated the manufacture of electric vehicles, but soon U.S. companies started making vehicles that were more desirable than ever before. Even some classic cars got an upgrade, switching from combustion to electric engines that could go from zero to sixty mph in 3.5 seconds. What’s strange is that it took us so long to realize that the electric motor is simply a better way of powering vehicles. It gives you more torque, more speed when you need it, and the ability to recapture energy when you brake, and it requires dramatically less maintenance.

As people from rural areas moved to the cities, they had less need even for electric vehicles. In cities it’s now easy to get around— transportation is frictionless. When you take the electric train, you don’t have to fumble around for a metro card or wait in line to pay— the system tracks your location, so it knows where you got on and where you got off, and it deducts money from your account accordingly. We also share cars without thinking twice. In fact, regulating and ensuring the safety of driverless ride-sharing was the biggest transportation hurdle for cities to overcome. The goal has been to eliminate private ownership of vehicles by 2050 in major metropolitan areas. We’re not quite there yet, but we’re making progress.

We have also reduced land transport needs. Threedimensional (3D) printers are readily available, cutting down on what people need to purchase away from home. Drones organized along aerial corridors are now delivering packages, further reducing the need for vehicles. Thus we are currently narrowing roads, eliminating parking spaces, and investing in urban planning projects that make it easier to walk and bike in the city. Parking garages are used only for ride-sharing, electric vehicle charging, and storage— those ugly concrete stacking systems and edifices of yore are now enveloped in green. Cities now seem designed for the coexistence of people and nature.

International air travel has been transformed. Biofuels have replaced jet fuel. Communications technology has advanced so much that we can participate virtually in meetings anywhere in the world without traveling. Air travel still exists, but it is used more sparingly and is extremely costly. Because work is now increasingly decentralized and can often be done from anywhere, people save and plan for “slow- cations”— international trips that last weeks or months instead of days. If you live in the United States and want to visit Europe, you might plan to stay there for several months or more, working your way across the continent using local, zero-emissions transportation.

While we may have successfully reduced carbon emissions, we’re still dealing with the after-effects of record levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The long-living greenhouse gases have nowhere to go other than the alreadyloaded atmosphere, so they are still causing increasingly extreme weather— though it’s less extreme than would have been had we continued to burn fossil fuels. Glaciers and Arctic ice are still melting, and the sea is still rising. Severe droughts and desertification are occurring in the western United States, the Mediterranean, and parts of China. Ongoing extreme weather and resource degradation continue to multiply existing disparities in income, public health, food security, and water availability. But now governments have recognized climate change factors for the threat multipliers that they are. That awareness allows us to predict downstream problems and head them off before they become humanitarian crises. So while many people remain at risk every day, the situation is not as drastic or chaotic as it might have been. Economies in developing nations are strong, and unexpected global coalitions have formed with a renewed sense of trust. Now when a population is in need of aid, the political will and resources are available to meet that need.

The ongoing refugee situation has been escalating for decades, and it is still a major source of strife and discord. But around fifteen years ago, we stopped calling it a crisis. Countries agreed on guidelines for managing refugee influxes— how to smoothly assimilate populations, how to distribute aid and resources, and how to share the tasks within particular regions. These agreements work well most of the time, but things get thrown off balance occasionally when a country flirts with fascism for an election cycle or two.

Technology and business sectors stepped up, too, seizing the opportunity of government contracts to provide largescale solutions for distributing food and providing shelter for the newly displaced. One company invented a giant robot that could autonomously build a four-person dwelling within days. Automation and 3D printing have made it possible to quickly and affordably construct high-quality housing for refugees. The private sector has innovated with water transportation technology and sanitation solutions. Fewer tent cities and housing shortages have led to less cholera.

Everyone understands that we are all in this together. A disaster that occurs in one country is likely to occur in another in only a matter of years. It took us a while to realize that if we worked out how to save the Pacific Islands from rising sea levels this year, then we might find a way to save Rotterdam in another five years. It is in the interest of every country to bring all its resources to bear on problems across the world. For one thing, creating innovative solutions to climate challenges and beta testing them years ahead of using them is just plain smart. For another, we’re nurturing goodwill; when we need help, we know we will be able to count on others to step up.

The zeitgeist has shifted profoundly. How we feel about the world has changed, deeply. And unexpectedly, so has how we feel about one another.

When the alarm bells rang in 2020, thanks in large part to the youth movement, we realized that we suffered from too much consumption, competition, and greedy self-interest. Our commitment to these values and our drive for profit and status had led us to steamroll our environment. As a species we were out of control, and the result was the near-collapse of our world. We could no longer avoid seeing on a tangible, geophysical level that when you spurn regeneration, collaboration, and community, the consequence is impending devastation.

Extricating ourselves from self- destruction would have been impossible if we hadn’t changed our mindset and our priorities, if we hadn’t realized that doing what is good for humanity goes hand in hand with doing what is good for the Earth. The most fundamental change was that collectively— as citizens, corporations, and governments— we began adhering to a new bottom line: “Is it good for humanity whether profit is made or not?”

The climate change crisis of the beginning of the century jolted us out of our stupor. As we worked to rebuild and care for our environment, it was only natural that we also turned to each other with greater care and concern. We realized that the perpetuation of our species was about war more than saving ourselves from extreme weather. It was about being good stewards of the land and of one another. When we began the fight for the fate of humanity, we were thinking only about the species’ survival, but at some point, we understood that it was as much about the fate of our humanity. We emerged from the climate crisis as more mature members of the community of life, capable of not only restoring ecosystems but also of unfolding our dormant potentials of human strength and discernment. Humanity was only ever as doomed as it believed itself to be. Vanquishing that belief was our true legacy.

Join our Book Club to discuss the extract.

To join the Book Club, click here .

To follow the Book Club on Twitter, click here .

To follow the Book Club on Instagram, click here .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Climate Change .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How direct biomass estimation can improve forest carbon accounting

Marco Albani

March 20, 2024

How pairing digital twin technology with AI could boost buildings’ emissions reductions

Philip Panaro, Sarah Parlow and François Amman

March 19, 2024

Warning on Great Barrier Reef bleaching and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

March 18, 2024

Access to financial services can transform women’s lives – an expert explains how

Kateryna Gordichuk and Kate Whiting

In pictures: These are the top underwater photographs of the year

March 14, 2024

4 ways geopolitical tensions are increasing carbon emissions

Laia Barbarà and Claudia Galea

March 12, 2024

What the World Will Look Like in 2050 If We Don’t Cut Carbon Emissions in Half

Before COVID-19 crashed into our world, governments had two major crises to tackle: the oil price crash and the climate crisis . Now that three crises have converged, so too can the path through them. We can rebuild clean and healthy with trillions of dollars of stimulus , transitioning away from fossil fuels to clean infrastructure and industries that create millions of jobs, overcome deep social inequalities and create a thriving economy.

In our book, The Future We Choose , we outline two possible futures; one where we act to halve emissions in this decade, and the one imagined in extract below, if we fail.

It is 2050 . Beyond the emissions reductions registered in 2015, no further efforts were made to control emissions. We are heading for a world that will be more than 3 degrees warmer by 2100.

The first thing that hits you is the air.

In many places around the world, the air is hot, heavy, and depending on the day, clogged with particulate pollution. Your eyes often water. Your cough never seems to disappear. You can no longer simply walk out your front door and breathe fresh air. Instead, before opening doors or windows in the morning, you check your phone to see what the air quality will be. Everything might look fine—sunny and clear—but you know better. When storms and heat waves overlap and cluster, the air pollution and intensified surface ozone levels can make it dangerous to go outside without a specially designed face mask (which only some can afford).

Our world is getting hotter, an irreversible development now utterly beyond our control. We have already passed tipping points, like The Great Melting of the Arctic sea ice , which used to reflect the sun’s heat. Oceans, forests, plants, trees, and soil had for many years absorbed half the carbon dioxide we spewed out. Now there are few forests left, most of them either logged or consumed by wildfire, and the permafrost is belching greenhouse gases into an already overburdened atmosphere.

In five to 10 years, vast swaths of the planet will be increasingly inhospitable to humans. We don’t know how habitable the regions of Australia, North Africa, and the western United States will be by 2100. No one knows what the future holds for their children and grandchildren.

More moisture in the air and higher sea surface temperatures have caused a surge in extreme hurricanes and tropical storms. Coastal cities in Bangladesh, Mexico, the United States, and elsewhere have suffered brutal infrastructure destruction and extreme flooding, killing many thousands and displacing millions. This happens with increasing frequency now.

Because multiple disasters are often happening simultaneously, it can take weeks or even months for basic food and water relief to reach areas pummeled by extreme floods. Diseases such as malaria, dengue, cholera, respiratory illnesses, and malnutrition are rampant.

Melting permafrost is releasing ancient microbes that today’s humans have never been exposed to—and as a result have no resistance to. Diseases spread by mosquitoes and ticks are rampant as these species flourish in the changed climate, spreading to previously safe parts of the planet, increasingly overwhelming us. Worse still, the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance has only intensified as the population has grown denser in habitable areas and temperatures continue to rise.

Every day, because of rising water levels, some part of the world must evacuate to higher ground. Every day you see images of mothers with babies strapped to their backs, wading through floodwaters. News stories tell of people living in houses with water up to their ankles because they have nowhere else to go, their children coughing and wheezing because of the mold growing in their beds, insurance companies declaring bankruptcy leaving survivors without resources to rebuild their lives.

Those who remain on the coast must now witness the demise of a way of life based on fishing. As oceans have absorbed carbon dioxide, the water has become more acidic and is now so hostile to marine life that all but a few countries have banned fishing, even in international waters. Many people insist that the few fish that are left should be enjoyed while they last—an argument, hard to fault in many parts of the world, that applies to so much that is vanishing.

As devastating as rising oceans have been, droughts and heat waves inland have created a special hell. Vast regions have succumbed to severe aridification, sometimes followed by desertification. Wildlife there has become a distant memory.

Cities such as Marrakech and Volgograd are on the verge of becoming deserts. Hong Kong, Barcelona, Abu Dhabi, and many others have been desalinating seawater for years, desperately trying to keep up with the constant wave of immigration from areas that have gone completely dry.

Extreme heat is on the march. If you live in Paris, you endure summer temperatures that regularly rise to 111°F (43.8°C). This is no longer the headline-grabbing event it would have been 30 years ago. Everyone stays inside, drinks water, and dreams of air-conditioning. You lie on your couch, a cold, wet towel over your face, and try to rest without dwelling on the poor farmers on the outskirts of town who, despite recurrent droughts and wildfires, are still trying to grow grapes, olives, or soy—luxuries for the rich, not for you.

You try not to think about the 2 billion people who live in the hottest parts of the world , where, for upward of 45 days per year, temperatures skyrocket to 140°F (60°C) —a point at which the human body cannot be outside for longer than about six hours because it loses the ability to cool itself down. Places such as central India are becoming increasingly challenging to inhabit. For a while people tried to carry on, but when you can’t work outside, when you can fall asleep only at 4 a.m. for a couple of hours because that’s the coolest part of the day, there’s not much you can do but leave. Mass migrations to less hot rural areas are beset by a host of refugee problems, civil unrest, and bloodshed over diminished water availability.

Even in some parts of the United States, there are fiery conflicts over water, battles between the rich who are willing to pay for as much water as they want and everyone else demanding equal access to the life-enabling resource. The taps in nearly all public facilities are locked, and those in restrooms are coin-operated. At the federal level, Congress is in an uproar over water redistribution: states with less water demand what they see as their fair share from states that have more. Government leaders have been stymied on the issue for years, and with every passing month the Colorado River and the Rio Grande shrink further

Food production swings wildly from month to month, season to season, depending on where you live. More people are starving than ever before. Climate zones have shifted, so some new areas have become available for agriculture (Alaska, the Arctic), while others have dried up (Mexico, California). Still others are unstable because of the extreme heat, never mind flooding, wildfire, and tornadoes.

One thing hasn’t changed, though—if you have money, you have access. Global trade has slowed as countries such as China stop exporting and seek to hold on to their own resources. Disasters and wars rage, choking off trade routes. The tyranny of supply and demand is now unforgiving; because of its increasing scarcity, food can now be wildly expensive. Income inequality has never been this stark or this dangerous.

As committed as nations are to keeping wealth and resources within their borders, they’re determined to keep people out. Most countries’ armies are now just highly militarized border patrols. Lockdown is the goal, but it hasn’t been a total success. Desperate people will always find a way.

Ever since the equatorial belt started to become difficult to inhabit, an unending stream of migrants has been moving north from Central America toward Mexico and the United States. Others are moving south toward the tips of Chile and Argentina. The same scenes are playing out across Europe and Asia. Some countries have been better global Good Samaritans than others, but even they have now effectively shut their borders, their wallets, and their eyes.

Even if you live in areas with more temperate climates such as Canada and Scandinavia, you are still extremely vulnerable. Severe tornadoes, flash floods, wildfires, mudslides, and blizzards are often in the back of your mind. Depending on where you live, you have a fully stocked storm cellar, an emergency go-bag in your car, or a six-foot fire moat around your house. People are glued to weather forecasts . Only the foolhardy shut their phones off at night. If an emergency hits, you may only have minutes to respond.

The weather is unavoidable, but lately the news about what’s going on at the borders has become too much for most people to endure. Under increasing pressure from public health officials, news organizations have decreased the number of stories devoted to genocide, slave trading, and refugee virus outbreaks. You can no longer trust the news. Social media, long the grim source of live feeds and disaster reporting, is brimming with conspiracy theories and doctored videos.

The demise of the human species is being discussed more and more. For many, the only uncertainty is how long we’ll last, how many more generations will see the light of day. Suicides are the most obvious manifestation of the prevailing despair, but there are other indications: a sense of bottomless loss, unbearable guilt, and fierce resentment at previous generations who didn’t do what was necessary to ward off this unstoppable calamity.

Adapted from THE FUTURE WE CHOOSE: Surviving the Climate Crisis by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac, published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Fight to Free Evan Gershkovich

- Meet the 2024 Women of the Year

- John Kerry's Next Move

- The Quiet Work Trees Do for the Planet

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Column: The Internet Made Romantic Betrayal Even More Devastating

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

What will the world be like in 2050?

Talk details.

- EssayBasics.com

- Pay For Essay

- Write My Essay

- Homework Writing Help

- Essay Editing Service

- Thesis Writing Help

- Write My College Essay

- Do My Essay

- Term Paper Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Write My Research Paper

- Assignment Writing Help

- Essay Writing Help

- Call Now! (USA) Login Order now

- EssayBasics.com Call Now! (USA) Order now

- Writing Guides

Life In The Future (2050) (Essay Sample)

Table of Contents

Introduction

How far into the future have you gone in your daydreaming or reflections? I recently took the time to think about what life in the future may look like.

For this essay, I asked myself, “What will life be like in 2050?” 2050 seems far away but with modern technology, economic development, scientific advances, and climate change, we will find ourselves in that day and age soon.

Want to write about life in the year 2050? You can read the essays below for your guidance. If you need extra help, think about availing our affordable essay writing services .

What will life be like in 2050 essay

The 2000s came with innovations in many fields and sectors across the world. Most notably, the Internet kicked in and revolutionized the world, connecting people globally and creating an international village of Internet citizens.

Social media took it further by establishing a platform where you could manage your network of relationships.

From 2010, more new inventions were introduced to the global population, and the trend seems to be continuing at a steady rate. Life ahead seems to hold more surprises.

This paper aims to outline possible future scenarios of what life may look like after the next few decades, specifically by 2050.

Heading into the 21st century

Space explorations.

The 21st century brought to the fore more technology-oriented inventions than ever before.

While the 20th century saw man land on the moon, the 21st century will witness man visit several of the many planets that dot the universe.

The first to be explored will be Mars, also called the Red Planet. The mission is likely to be accomplished by 2030, as planned by NASA. This will write a new chapter in history and set a precedent for future explorations by subsequent human generations.

Discovering the cure for AIDS

Moreover, increased investment in research activities is likely to pave the way for the discovery of a vaccine for Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Increased acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community

Sex and gender issues are another aspect that will change by 2050.

Homosexuality has become a familiar topic of conversation in the current generation. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues are slowly being talked about and recognized amid heated debates among more conservative groups.

By 2050, they are likely to be such a universally accepted community that the law will require employers across the world to set aside a percentage of their employment vacancies for LGBT candidates. Such a mandate will be implemented alongside the existing gender-based directive of the equal female-and-male employee ratio.

The digitization of media

Media technology continues to rapidly evolve. At present, social media is taking the lead in relaying quick news bits and community engagement. Without question, it poses a threat to traditional sources of media including television, newspapers, radios, and magazines.

By 2025, some traditional media sources, specifically print newspapers, will have a diminished readership as online news sites and social media will have penetrated their share of readership.

The rise of e-commerce and e-cars

Mobile phones will play a greater role in retail shopping and financial transactions. Electronic money will replace paper money.

Additionally, with declining oil reserves across the world, electric cars will step in for petrol cars in the next few decades. Consequently, there will be a major shift in job trends, as some roles will be taken over by AI or will no longer be relevant.

The ever-changing face of US politics

The United States made history in 2016 by electing a president with no prior experience in politics. The electorate is breaking away from the traditional mentality of choosing experienced politicians with track records.

To say that a female president will be elected into office after President Donald Trump’s era is not shallow speculation. By 2050, the U.S. will have tasted female leadership.

Also, if Trump’s anti-immigration policy and deportation of illegal immigrants get adequate support in subsequent leaderships, the United States may have stunted population growth and few cases of immigration. These kinds of policies will impact America’s role as a global influencer.

Global warming continues to be a problem

Finally, global warming will become an even bigger problem. We will continue to see a rise in sea levels. At the same time, pollution will damage our freshwater sources.

From another perspective, dictatorships, chiefly in Asia, will destabilize the world. North Korea, China, and other emerging nuclear-armed countries will become major security threats to the entire world.

While such countries may trigger increased regional wars, World War 3 will not occur. In addition to this, terrorist groups will dominate major regions of the world.

With many changes up ahead – good and bad – in the coming decades, it would be good to prepare and anticipate how it will personally affect us.

Life In The Future 2050 Short Essay

In this day and age where we live in a developed world, it would be so easy to let our imaginations run wild when we think of what society would look like in the year 2050.

Nowadays, the technological advances we’ve made in almost every industry show incredible progress. Virtual reality is shaping the world of gaming, as well as e-learning and employee onboarding. Artificial intelligence is helping us run our households. Solar energy is being featured in many progressive homes and structures.

What about if we fast-forward to 2050? We may see a completely different list of developing countries as we continue to witness technology changing the lives of the global population. Self-driving cars may be a common occurrence as we seek to find ways to promote safer roads. More environmentally-friendly products and services will be used in homes and offices as we become more aware of the effects of climate change. Finally, robots may change the face of manufacturing. Manual labor may no longer be needed, which will result in tremendous job losses.

These are just a few of many life-altering changes that we could see happening in the coming years.

How to Write an Essay About The Future

A good way to envision the future is to daydream. When we describe something that hasn’t happened yet, we largely utilize our imagination. As such, we need to take time to sit down and think about our image of the future. Ask yourself all sorts of questions that will stimulate your imagination. Will we be able to finally contact other planets? How will genetic engineering cause demographic changes? Are we going to care more deeply about renewable resources? What will the state of the ozone layer be given our current trend? After asking yourself all these questions, the next step is to do some actual research. Look for credible sites and authors that focus on forecasting and predicting. See how they line up with your speculations. Choose the trends that most accurately align with each other.

Will Life Be Better In The Future?

It depends on what you mean by “better.” Are driverless cars really the best way to ensure road safety? Will young people truly benefit from the progress we make as a society? Will technology really bring people together? In other words, will these revolutionary changes really be for a more connected and happy society or simply a matter of convenience? It is hard to answer this question definitively. We don’t know if life will be better for every member of the global population in 2050, but we know that it will certainly be different for everyone.

- Show search

Perspectives

The Science of Sustainability

Can a unified path for development and conservation lead to a better future?

October 13, 2018

- A False Choice

- Two Paths to 2050

- What's Possible

- The Way Forward

- Engage With Us

The Cerrado may not have the same name recognition as the Amazon , but this vast tropical savannah in Brazil has much in common with that perhaps better-known destination. The Cerrado is also a global biodiversity hotspot, home to thousands of species only found there, and it is also a critical area in the fight against climate change, acting as a large carbon pool.

But Brazil is one of the two largest soy producers in the world—the crop is one of the country’s most important commodities and a staple in global food supplies—and that success is placing the Cerrado in precarious decline. To date, around 46% of the Cerrado has been deforested or converted for agriculture.

Producing more soy doesn’t have to mean converting more native habitat, however. A new spatial data tool is helping identify the best places to expand soy without further encroachment on the native landscapes of the Cerrado. And with traders and bankers working together to offer preferable financing to farmers who expand onto already-converted land, Brazil can continue to produce this important crop, while protecting native habitat and providing more financial stability for farmers.

The Cerrado is just one region of a vast planet, of course, but these recent efforts to protect it are representative of a new way of thinking about the relationship between conservation and our growing human demands. It is part of an emerging model for cross-sector collaboration that aims to create a world prepared for the sustainability challenges ahead.

Is this world possible? Here, we present a new science-based view that says “Yes”—but it will require new forms of collaboration across traditionally disconnected sectors, and on a near unprecedented scale.

Download a PDF version of this feature. Click to see translated versions of this page.

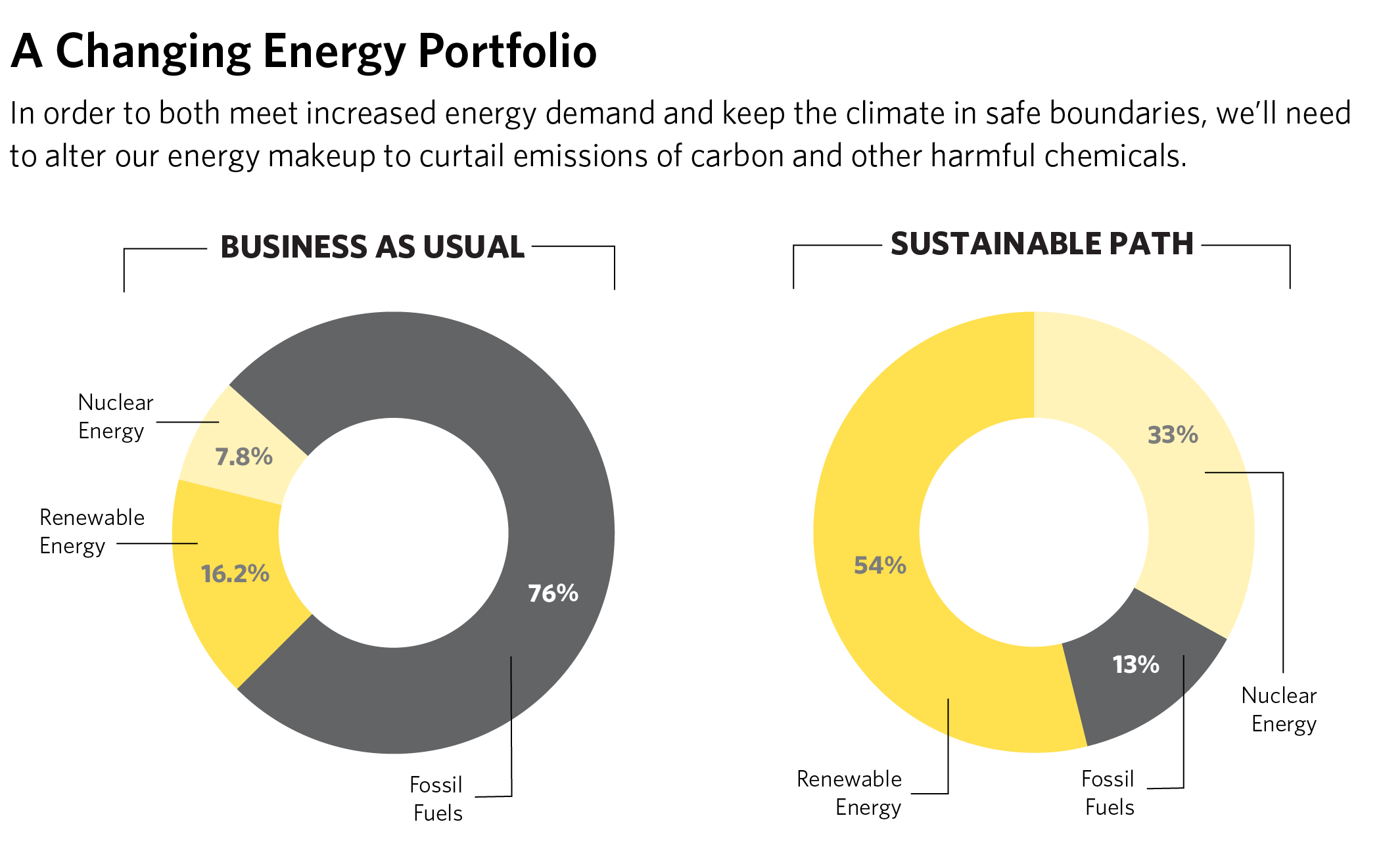

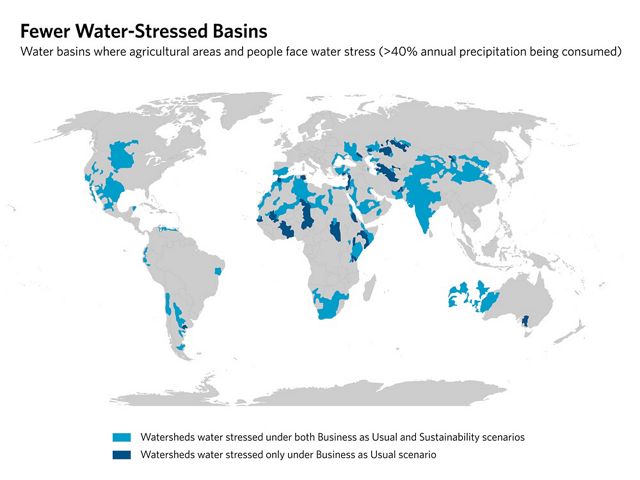

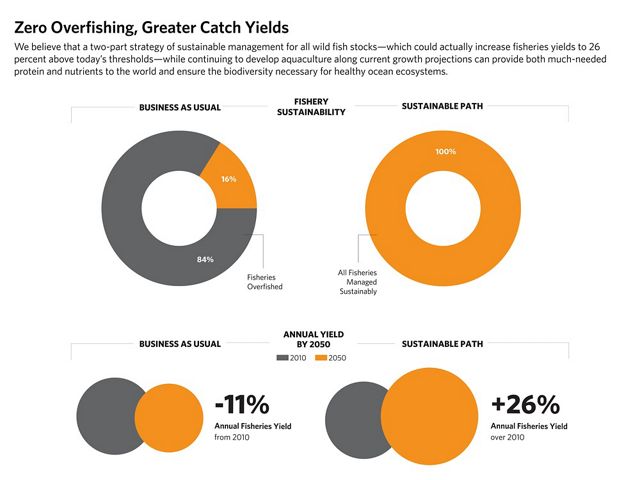

I. A False Choice