HJF Medical Research International

Participants at HJF Medical Research International in Abuja, Nigeria, have been vaccinated in the first Phase 2 clinical trial of a Lassa fever virus (LASV) vaccine candidate to date, according to IAVI, a nonprofit scientific research organization and the trial sponsor. The study ( IAVI C105/PREVAIL15 ) is funded by CEPI , an innovative global partnership working to accelerate the development of vaccines against epidemic and pandemic threats.

Maurice is one of many who have benefited from PEPFAR’s promise to deliver quality healthcare in remote communities through a mobile clinic outreach program. Before the mobile clinic, members of Maurice’s community would have to travel to Tanzania by foot - an eight-day journey in territory inhabited by wild animals and warring clans, to receive health services. “Some people would die there, and it was hard,” Maurice says.

When Edith Okafor, a 50-year-old widow and caregiver of four boys, walked into the Clinical Training and Research Centre (CTRC), 44 Nigerian Army Reference Hospital Kaduna (NARHK) to begin antiretroviral therapy in April 2007, she had no idea that that encounter would become the beacon of hope in her state of despair.

Geoffrey Mwakyusa (49), a resident of the Kyela District Council in the Mbeya Region, is among hundreds of thousands of people in the area who have connected with Community-based HIV Service Providers (CBHSP) to find out their HIV status through the distribution of HIV self-testing kits.

Ahead of the October 20 Mashujaa Day celebrations in Kericho, Kenya’s Deputy President H.E. Rigathi Gachagua, EGH, visited the Kericho, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)/ Walter Reed Project (WRP) Clinical Research Center (CRC), where he inaugurated the biosafety level 3 tuberculosis (TB) Reference Laboratory.

The African Cohort Study (AFRICOS) celebrated its 10th Anniversary on Wednesday 1st November, 2023, with a Research Symposium to review key findings from the study, share ongoing analyses, and discuss plans under the theme titled, “Progress and Future Directions.”

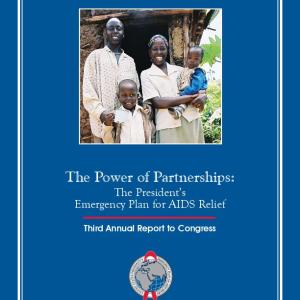

In 2007, Joyce, David and their two children were featured on the cover of PEPFAR’s annual report to Congress, but their story about how PEPFAR transformed their lives began in 2005. David and Joyce were expecting their second child in 2005 when David discovered he was living with HIV. The next day, David brought his wife, Joyce, to Kericho District Hospital to get tested.

September 28, 2023, marked a significant milestone, as HJF Medical Research International Ltd/Gte. (HJFMRI Ltd/Gte.) celebrated the grand opening of its new laboratories and office complex in Abuja, Nigeria.

Deborah is one of the oldest stories of PEPFAR’s impact in Kenya and is a true testament to the purpose and mission of PEPFAR. More than 20 years ago, Deborah was diagnosed with HIV.

HJFMRI helped coordinate entomology surveillance teams to quickly gather data in a race against emerging dengue and yellow fever outbreaks in Kenya.

HJFMRI develops partnerships, infrastructure, and expertise around the world to help researchers solve complex challenges in global health. Learn more about us.

HJFMRI Focus Areas

HJFMRI has decades of experience supporting partners in a wide range of complex research endeavors. Our multidisciplinary team of experts works to implement flexible, comprehensive approaches to vaccine development, clinical research, infectious disease surveillance and therapeutics, global health program implementation, capacity building, and military-military health initiatives.

HJFMRI's Services

HJFMRI facilitates medical research by providing a range of responsive, flexible services to support clinical testing and global health program implementation around the world. We provide support services in protocol planning, site development, research operations, data collection and analysis, regulatory compliance, and international program staffing and contracts.

HJFMRI is proud to partner with organizations from across the globe to advance global health, including host country governments, public institutions, private entities, universities, and foundations.

Maseno University and School of Medicine, Kenya

Site Director

Prof. Collins Ouma is the Program Leader, Health Challenges and Systems within the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), where he leads amongst other things translation of research evidence to policy. His research focuses on public health, genetic, and environmental factors that predisposes the human populations to both infectious and non-infectious diseases in sub-Saharan Africa.

Dr. Samuel Bonuke Anyona , Lecturer, Medical Biochemistry, Maseno University [email protected]

Dr. Anyona is a faculty member in the Department of Medical Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Maseno University and a post-doctoral fellow under the career development (K43) grant award. His research activities focus on pediatric populations living under intense malaria transmission in western Kenya, a region holoendemic for Plasmodium falciparum. Dr. Anyona acquired hands-on experience with various techniques including; molecular genetics, molecular biology (including cloning and construct designs), biochemical and immunofluorescence analyses (both by flow cytometry and microscopy), bioinformatics, and statistics. Dr. Anyona is an alumnus of the HBNU Fogarty Global Health Fellowship Program.

Dr. Ayodo is a basic science researcher trained in genetic epidemiology of infectious diseases but now focusing on applied epidemiology and implementation research. The focus of his work is to develop community intervention models to eliminate or sustain low transmission of infectious diseases. I am also actively involved in understanding the origin of man in attempt to understand the biology of diseases of conditions such as sickle cell disease.

Dr. Kiprotich Chelimo , Senior Lecturer of Biomedical Sciences and Technology, Maseno University [email protected]

Dr. Chelimo is involved in a number of long-term active and ongoing training and research collaborations with several international institutions including: University of New Mexico-USA (current institution ofaffiliation for Dr. Perkins), University of Massachussets Medical School (MA-USA), Case Western Reserve University (Ohio-USA), Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI, Centre for Global Health Research), and International Cancer Institute (Kenya). His current focus in these collaborations is to work closely with other expert scientist in supporting and nurturing a crop of upcoming scientists in my area of expertise. To date, as a senior Faculty at Maseno University in Kenya, he has mentored over 12 postgraduate students to completion.

Dr. Michael Gicheru , Associate Professor of Immunology, Kenyatta University [email protected]

Dr. Gicheru has long-term active and ongoing collaborations with Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI, Centre for Global Health Research), Maseno University, University of New Mexico-USA (current institution of affiliation for Dr. Perkins), and several other institutions with current common interests in Africa with the main aim of forming a consortium to effectively mentor endemic area scientists. To date, as a senior Faculty at Kenyatta University in Kenya, he has mentored over 90 postgraduate students to completion. Dr. Gicheru has contributed to the development of vervet monkey model for leishmaniasis and evaluation of leishmania vaccine candidates in nonhuman primate model.

Dr. John Michael Ong’echa , Principal Research Officer, Kenya Medical Research Institute

Dr. Ong’echa is a Principal Research Officer with the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Therapeutic Sciences (CREATES), Strathmore University, Kenya. He has significant experience working on the genetics and immunology of infectious diseases. His training in immunology and genetics and many years working on Dr. Perkins’ NIH-funded project entitled “Genetic Basis of Severe Malarial Anemia – R01 AI051305” and my FIC funded R01 (Global Research Initiative Program (GRIP) – R01 TW007631) titled ‘Molecular Immunologic Role of Cytokines in the Development of Malarial Immunity’ (2007-2011) has given him adequate experience in conducting field studies. In addition, through Dr. Perkins’ D43 training grant (D43 TW005884) where I served as the Program Co-Director, he has been able to successfully mentor a large number of African scientists, most of whom have now developed independent careers in research. Dr. Ong’echa has also been involved in other additional multi-country and multi-institutional training programs.

Dr. Evans Raballah , Senior Lecturer, Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology [email protected]

Dr. Raballah is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences. He holds a doctorate degree in Immunology, specializing in Immunogenetics of infectious diseases. His academic and research interests are in the fields of malaria, bacteremia, HIV and COVID-19. His major scholarly contribution was defining the CD4+ cells and their intracellular IFN-g and IL-17 cytokines in severe malarial anemia in a pediatric population of western Kenya. He has further published over 25 manuscripts in peer reviewed refereed journals. In 2016, he received the Junior Researcher of the year award of Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology. He currently serves as the Co-ordinator of Medical Biotechnology program in the department of Medical Laboratory sciences and a member of the departmental postgraduate committee. Dr. Raballah is an alumnus of the HBNU Fogarty Global Health Fellowship Program.

+254 709 983000/ +254 709 983676

Our History

Our policies, partnerships and collaborators, major research themes, research platforms, scientific departments.

- Policy Briefs

- Publications

- Capacity Strengthening

- Data Access

Established in 1989

Who is KEMRI Wellcome Trust?

The KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP) is based within the KEMRI Centre for Geographic Medical Research – (Coast). Our core activities are funded by the Wellcome Trust. We conduct integrated epidemiological, social, laboratory and clinical research in parallel, with results feeding into local and international health policy. Our research platforms include state-of-the-art laboratories, a demographic surveillance system covering a quarter of a million residents, partnership with Kilifi County Hospital in health care and hospital surveillance, a clinical trials facility, a vibrant engagement programme and a dedicated training facility.

The KWTRP leadership includes the Ag. Executive Director Edwine Barasa, the KEMRI Centre Director Dr. Joseph Mwangangi, Deputy Director George Warimwe and the Chief Operating Officer Catherine Kenyatta.

- Our mission

To undertake cutting-edge and novel research relevant to national, regional and global needs.

To conduct high quality, purposeful, and relevant research in human health, building sustainable research capacity and leadership.

- To conduct research to the highest international scientific and ethical standards on the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the region in order to provide the evidence base to improve health.

- To train an internationally competitive cadre of Kenyan and African research leaders to ensure the long term development of health research in Africa

The Kenyan Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) was established through the Science and Technology (Amendment) Act of 1979, which has since been amended to Science, Technology and Innovation Act, 2013 with the mandate to carry out health science research in Kenya. The Kilifi-based Centre for Geographic Medicine Coast (CGMR-C) is among the 12 KEMRI centers.

The Wellcome Trust was established in 1936 by an endowment left by Henry Wellcome in his will. Henry Wellcome was a rich businessman and philanthropist in the UK. He also travelled in Sudan and Egypt, where he took an interest in malaria control and commissioned a floating laboratory on the Nile. The Wellcome Trust continues to support research in Africa and was one of the first research institutions to partner with the new independent Government of Kenya in 1964, creating the Wellcome Trust Research Laboratories in Nairobi. In the 1980s a few Wellcome Trust funded scientists including Stephen Oppenheimer and Bill Watkins began working in Kilifi District Hospital in collaboration with KEMRI. In 1989 the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP) was formed, led by Kevin Marsh and Norbert Peshu. Due to the continued growth of research activities in Kilifi, in 1995 KEMRI granted the Kilifi Station a full Centre status as “KEMRI Centre for Geographic Medicine Research – Coast (KEMRI CGMRC).

Finding ways to beat malaria; Initial work focused on malaria, a devastating disease that was causing the deaths of many children. Working closely with colleagues in the Ministry of Health, researchers conducted studies on insecticide-treated bed nets, antimalarial drugs to prevent malaria in pregnant women and descriptions of severe malaria. Over the last 15 years there has been impressive improvements in malaria control across Africa with Kilifi registering 90 percent drop in malaria cases. Today KWTRP continues to build on its early success in bed net trials with work led from Nairobi that provides information and advice to the national malaria control Programme’s of 14 countries, supported by statistical models to generate maps of malaria risk.

In Kilifi Hospital, KWTRP facilitated the creation of a High Dependency Paediatric Unit where severely sick children had intensive monitoring and treatment. The first studies on clinical definitions of severe malaria in children were based on simple observation by the bedside. Work on severe malaria continues today with increasingly sophisticated laboratory work, DNA sequencing and retinal imaging, and clinical trials that have informed the use of anti-epilepsy drugs and fluids in severely unwell children.

As the Programme developed it was apparent that malaria was just one of a host of health problems confronting children on the coast and that often these problems were interrelated. The focus therefore expanded to include work including pneumonia, meningitis, HIV and malnutrition. Other studies included social science and health systems perspectives, as well as research on community involvement.

In early studies KWTRP engaged shopkeepers with a training programme to ensure they gave anti-malarials at the correct dose. If done well this prevents the need for hospital admissions. These successes have been built on in recent times, with KWTRP studies now showing that SMS messages can help doctors and patients to use anti-malarials correctly. KWTRP has also shown how training and support packages can help doctors and nurses in hospital to improve their patient care. These interventions result in patients getting the correct treatment and saving lives.

The cornerstone of research success is community involvement. This is done through regular interactions with opinion leaders and a network of community representatives, the Schools Engagement Programme, social media and regular open days. The programme builds mutual understanding between researchers and the community, and ensures that research is responsive to community views and interests. This research findings have done much to improve the health of the partnering community in Kilifi, and health around Africa. The work has been enhanced by modern technology which now includes online interaction with secondary schools.

Apart from conducting the highest quality research, one of the objectives is to support the development of scientific leadership in Kenya through deliberate capacity building initiatives. KWTRP has a particular focus on building links with schools in the community, which involves promoting better understanding of science and research. In addition, it has a structured internship programme for introducing Kenyan graduates to research training master’s degree and PhD students. Young researchers are supported through a system of career development to join other research institutions in the region or to develop careers with the programme.

The Kenya Medical Research Institute is a national body mandated by an Act of Parliament to provide overall leadership and guidance for health research in Kenya. The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme is embedded within the KEMRI Centre for Geographic Medicine Research-Coast as one of the KEMRI center’s in Kenya.

Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is an independent charity funding research to improve human and animal health. Established in 1936 and with an endowment of around 13 billion, it is the UK’s largest non-governmental source of funds for biomedical research. As a privately endowed charity, it is independent from governments, from industry and from donors.

The governing document of the Wellcome Trust is its constitution. This represents an updated version of the will of Sir Henry Wellcome, through which the Wellcome Trust was established in 1936. Ultimate responsibility for all activities lies with the Board of Governors.

The Wellcome Trust has since 1989 funded the Core activities of the KEMRI|Wellcome Trust research programme. Which includes administrative support, and support of the key platforms of clinical services, community engagement, Laboratory’s and the Kilifi Health Demographic Surveillance system. This has over time ensured continuation of the research work undertaken by the Programme.

The University of Oxford is internationally renowned for the quality and diversity of its research, with over 3000 academic staff and 3000 postgraduate students working on research. The university’s position as a centre of excellence is enhanced by the ongoing development of interdisciplinary research centers, and collaboration with international academic and industrial partners. The University has a critical mass of supported researchers both local and international, who work within the Programme. This collaboration has also resulted into a well-defined research capacity building platform for researchers in Africa.

The Department of Health in the County provides overall leadership in health service delivery, and facilitates a cordial co-existence with our research centre. Medical staff from the county and periphery health facilities participates in research activities, including clinical research.

The Nairobi programme has close working relations with the Nairobi county health department working closely with the various health institutions under its mandate to facilitate the research work done. Focus is mainly on policy and improving of health care systems. This has over time been extended to include research in key populations in the city.

In Nairobi, the Programme has forged strong links with the Ministries of Health and Education, with several of the Programme researchers acting as technical advisers to the Kenyan Government departments and playing a major part in the development of national strategies.

A series of clinical trials focusing on in-patient hospital care have led to collaborations in Eastern Uganda, notably in Soroti and Mbale District Hospitals. Mbale Clinical Research Unit has been founded on the grounds of Mbale District Hospital and includes a collaboration with Busitema University.

The work of the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme is also based on other partnerships. Key researchers hold academic positions at a number of institutions including the universities of Oxford and Warwick, the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Imperial College, and the Institute of Child Health in London.

KWTRP Researchers are also committed to engaging with the local community, to discuss their research and to build mutual understanding and trust between researchers and the community by responding to various concerns. By developing such strong links, the Programme can ensure that its activities are accepted and approved by local communities – a prerequisite for its long-term studies. Moreover, the close juxtaposition of research and application can help ensure that its activities are focused on delivering practical benefits.

And finally, in a national and international context, the key relationships with policy makers and health officials help to ensure that important research findings make a difference to medical care – and thus have an influence far beyond the geographic areas in which the team works.

The Programme has two main bases in Kenya but works in many other parts of the country and is increasingly involved in regional collaborations to support research in neighbouring countries.

The Ugandan unit is based in Mbale town within the Mbale Regional Referral Hospital and was founded in 2008 in response to the need for evidenced based clinical guidelines.

- Civil Society

- Document Centre

- Education NGOs and CSOs

- Education Suppliers

- Government Agencies

- Independent Schools

- Other Organisations

- Research Institutes

- Universities

- Universities and Colleges

Research Institutes in Kenya

The Kenya Medical Research Institute is one of East Africa’s leading medical research centres and is the national body responsible for carrying out health science research in Kenya. The Kenya Institute of Education promotes development and delivery of relevant, high-quality, affordable education and training programmes, materials and services. The Kenya Agricultural Research Institute has the objective of food security through improved productivity and environmental conservation.

- All member countries

- Our network:

- Commonwealth Education Online

- Commonwealth Governance Online

- Commonwealth Health Online

PUBLICATIONS, NEWS & EVENTS

Find a mentor.

All publications resulting from the research or research training supported by this award must acknowledge FIC and all co-funders with the following or comparable footnote: This project was supported by NIH Research Training Grant D43TWW009345 funded by the Fogarty International Center, the NIH Office of the Director Office of AIDS Research, the NIH Office of the Director Office of Research on Women's Health, The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

The content of this website is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the academic institutions affiliated with this program.

Kenya has hosted more NPGH Fogarty Fellows than any other country, so previous projects have covered a wide range of topics: everything from shock-related mortality in pediatric patients to STI modeling in non-human primates . Though much research has focused on HIV/AIDS, there have been many different approaches including the effect of hormonal birth control on HIV risk , partner notification in serodiscordant couples , and the interplay between iron deficiency, malaria, and HIV . Dr. Bukusi, Co-Director of the Research Care and Treatment Program at the Kenya Medical Research Institute, gave an interview about her career as an HIV/AIDS researcher on our blog , and Fan Lee, a 2014-2015 Fogarty Scholar also wrote about her experiences at the start of her fellowship.

For a list of projects in Kenya: click here -->

Affiliated Institutions

KEMRI conducts research from 12 research centers that focus on different areas of national and strategic importance: Centre for Biotechnology Research and Development (CBRD); Centre for Clinical Research (CCR); Centre for Geographic Medicine Research-Coast (CGMR-C); Centre for Global Health Research (CGHR); Centre for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases Control Research (CIPDCR); Centre for Microbiology Research (CMR); Centre for Public Health Research (CPHR); Centre for Respiratory Diseases Research (CRDR); Centre for Traditional Medicine and Drug Research (CTMDR); Centre for Virus Research (CVR); The Eastern and Southern Africa Centre of International Parasite Control (ESACIPAC). KEMRI also has a graduate school known as the KEMRI Graduate School of Health Sciences (KGSHS), a Health Safety and Environment Program, and a production centre.

KEMRI Centre for Global Health Research (CGHR): CGHR is located in Kisumu City, western Kenya, an area that is endemic for major infectious diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDs. Research conducted in CGHR focuses on infectious diseases of medical importance. Specifically, the Centre has carried out cutting-edge research focusing on trials on the efficacy of drugs, emergence of drug and vector resistance, epidemiology, immunology, molecular biology, vector biology, climate and human health, characterization of malaria vaccine candidate antigens, malaria vaccine trials, malaria in pregnancy and interaction of malaria and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), schistosomiasis, intestinal helminthes, HIV/AIDS and its impact on the community, HIV interaction with other infectious diseases, tuberculosis and reproductive health.

The Center consists of two administrative buildings, an entomology building, two refurbished laboratory blocks, a new state-of-the-art multidisciplinary laboratory complex and a clinic. The administrative blocks houses the Center Director’s office, offices for senior scientists, collaborating scientists and visiting scientists, senior administrators, a data section, a computer room, a library, storage facilities and 5 modern seminar rooms for training, meetings and holding seminars, with seating capacity ranging from 8 to 40 people. The seminar rooms are equipped with modern audio-visual (AV) equipment including LCDs, permanent and portable screens, TVs and VCRs. Two of the seminar rooms are also equipped with video-conference facilities. The laboratory facilities consist of separate well-equipped rooms for basic laboratory diagnostics, immunology and molecular biology laboratories, parasite cultures and drug sensitivity testing, a clinical hematology and biochemistry laboratory, an insectary and insecticide-testing huts. The current laboratory equipment in the Centre include a modern compound, inverted and fluorescent microscopes, differential Coulter counters, multiparameter biochemistry machines, Hb electrophoresis equipment, refrigerated bench-top centrifuges, multifunctional ELISA readers and automated washers, twin CO2 conventional incubators, liquid scintillation counters, level II biosafety cabinets, FACS count, four and five-color FACSCaliburs and FACScan, PCR enclosures and high capacity PCR machines, real-time PCR machines, 377 and 3100 ABI gene sequencers, UVP gel imaging systems, and nanopure water purification systems. There are numerous -70 ultra-freezers and several bulk liquid nitrogen tanks for sample storage.

The center has recently installed a liquid nitrogen generator with capacity to produce 500 liters of liquid nitrogen per day. In addition to the above facilities, there are several facilities for conducting hospital-based clinical studies. The biggest of these is a stand-alone Clinical Research Centre located at the New Nyanza Provincial Hospital in Kisumu City. It consists of a pediatric ward, clinical laboratory, offices and HIV counseling facilities. Plans are at an advanced stage to convert part of this facility into a vaccine trial site. This will be in addition to an already existing state-of-the-art and well-equipped vaccine and drugs trial site with capacity to conduct GCP/GLP compliant trials at Kombewa, situated about 30 kilometers from Kisumu City. Read more…

The hospital’s mission is to “provide accessible specialized quality health care, facilitate medical training, research; participate in national health planning and policy,” and its mandate includes providing facilities for medical education and research, as well as participating in national health planning. As a regional referral hospital, there is a wealth of data that can be utilized to inform and improve health care provision within and outside Kenya, especially around HIV care and treatment. KNH provides HIV care for thousands of inpatients each month and sees hundreds of HIV-infected adults and children each day at the HIV Comprehensive Care Center (CCC). The CCC has >5,000 HIV-infected adults registered in outpatient follow-up and >700 HIV-infected children enrolled in care. Eighty-one percent of these adults are currently on ART and 467 new patients were initiated during the last 6 months of 2011 alone. In the inpatient setting, KNH has implemented routine provider-initiated HIV testing (PITC), successfully testing approximately 1,000 patients monthly and finding prevalence to be >6% in this population.

The KNH Department of Research Chair Dr. Nelly Mugo, and Vice-Chair Dr. John Kinuthia, who both earned MPH degrees at UW with Fogarty funding, have identified implementation science as their current research priority and this has been endorsed at meetings with the hospital’s Deputy CEO as recently as May 2012 when Dr. Carey Farquhar met with KNH leadership to discuss research directions for the institution and future collaborations.

AIDS International Research Training Program (AIRTP): Since 1985 when Drs. Joan Kreiss and King Holmes began working in Nairobi in collaboration with the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta National Hospital, UW faculty have conducted several hundred research projects on HIV prevention, treatment and pathogenesis. This longstanding partnership between UW and KNH, and the solid research foundation that has been built over more than two decades, can be readily leveraged to focus on implementation science training relevant to the HIV care cascade. More than 450 papers have been published with AITRP trainees as first or co-authors and this number has steadily increased by 20-30 publications each year for the last 5 years. All of these publications address HIV and a significant proportion have been led by Kenyan investigators and have Kenyans as first authors, including several papers in high-profile journals such as the Lancet and JAMA. Major research projects that have been completed or are ongoing are included below to demonstrate the ability of the UW/Kenya collaboration to absorb new trainees. Those based at KNH will also build capacity for research at the institution. All will provide rich opportunities for trainees in the proposed program to conduct research in a rigorous manner with strong mentorship by experienced U.S. and Kenyan investigators. Read more…

Primary Faculty

Research themes.

- Shock-related mortality in pediatrics

- STI modeling in non-human primates

- Effects of hormonal birth control on HIV risk

- Partner notification in serodiscordant couples

- Interplay between iron deficiency, malaria, and HIV

For a list of projects in Kenya: click here

Current Fogarty Trainees

Past fogarty trainees.

- COSMAS GITOBU

- FLORENCE JAGUGA

- JEPCHIRCHIR KIPLAGAT

- DIANA MARANGU

- JAMES KANGETHE

- SIGRID COLLIER

- GRANT CALLEN

- DICKENS ONYANGO

- ASHLEY KARCZEWSKI

- NEIL SIRCAR

- SUSAN JACOB

- IRENE MUKUI

- MICHAEL SCANLON

- NICOLE YOUNG

- JERRY ZIFODYA

- NANCY NGUMBAU

- GEORGE OMONDI PAUL

- ALIZA MONROE-WISE

- EHETE BAHIRU

- ANNE KAGGIAH

- ANJULI WAGNER

- MACKENZIE FLYNN

- ODESSA LACSINA

- GEORGE AYODO

- ERIC MURIUKI

- JENNIFER MARK

- LINNET MASESE

- MARILYN KIOKO

- CYRUS AYIEKO

- DANIEL CHIVATSI

- ELIZABETH IRUNGU

- KAREN HAMRE

- BARTHOLOMEW ONDIGO

- FRANKLINE ONCHIRI

- JOHN CRANMER

- ROSE BOSIRE

Recent and Ongoing Projects

Collaborating institutions.

All publications resulting from the research or research training supported by this award must acknowledge FIC and all co-funders with the following or comparable footnote: This project was supported by NIH Research Training Grant # D43 TW009345 funded by the Fogarty International Center, the NIH Office of the Director Office of AIDS Research, the NIH Office of the Director Office of Research on Women's Health, The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences

© University of Washington, 2024

Country Selection

Regulatory Authority

Scope of assessment, regulatory fees, ethics committee, scope of review, ethics committee fees, oversight of ethics committees.

Clinical Trial Lifecycle

Submission Process

Submission content, timeline of review, initiation, agreements & registration, safety reporting, progress reporting.

Sponsorship

Definition of Sponsor

Site/investigator selection, insurance & compensation, risk & quality management, data & records management, personal data protection.

Informed Consent

Documentation Requirements

Required elements, participant rights, emergencies, vulnerable populations, children/minors, pregnant women, fetuses & neonates, mentally impaired.

Investigational Products

Definition of Investigational Product

Manufacturing & import, quality requirements, product management, definition of specimen, specimen import & export, consent for specimen, requirements, additional resources.

Quick Facts

Clinical research in Kenya is regulated and overseen by the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) and the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) .

Pharmacy and Poisons Board

As per the PPA , the CTRules , and the G-KenyaCT , Kenya’s PPB is the regulatory authority responsible for clinical trial approvals, oversight, and inspections. As described in KEN-21 , the PPB and its Expert Committee on Clinical Trials (ECCT) evaluate all matters relating to clinical trials and grant permission for clinical trials to be conducted in Kenya. See KEN-20 , KEN-21 , and KEN-16 for more information about PPB.

Per the PPA and the CTRules , the PPB is authorized to undertake various mandated duties regarding regulation of medicines including (Note: the requirements provide overlapping and unique elements so each of the items listed below will not necessarily be in each source):

- Advise the government in all matters relating to the safety, packaging, labelling, distribution, and disposal of medicines

- Ensure that all medicinal products manufactured in, imported into, or exported from the country conform to prescribed standards of quality, safety, and efficacy

- Ensure that the personnel, premises, and practices employed in the manufacture, storage, marketing, distribution, and sale of medicinal substances comply with the defined codes of practice and other prescribed requirements

- Grant or revoke licenses for the manufacture, importation, exportation, distribution, and sale of medicinal substances

- Maintain a register of all authorized medicinal substances

- Publish, at least once every three (3) months, lists of authorized or registered medicinal substances and lists of products with marketing authorizations

- Regulate narcotic, psychotropic substances, and precursor chemical substances

- Consider applications for approval and alterations of dossiers intended for use in marketing authorization of medical products and health technologies

- Inspect and license all manufacturing premises, importing and exporting agents, wholesalers, distributors, pharmacies (including those in hospitals and clinics), and other retail outlets

- Prescribe a system for sampling, analysis, and other testing procedures of finished medicinal products released into the market to ensure compliance with the labeled specifications

- Conduct post-marketing surveillance of safety and quality of medical products

- Monitor the market for the presence of illegal or counterfeit medicinal substances

- Regulate the promotion, advertising, and marketing of medicinal substances in accordance with approved product information

- Approve the use of any unregistered medicinal substance for purposes of clinical trials, compassionate use, and emergency use authorization during public health emergencies

- Approve and regulate clinical trials on health products

- Disseminate information on medical products to health professionals and to the public to promote their rational use

- Collaborate with other national, regional, and international institutions on medicinal substances regulation

- Advise the Cabinet Secretary on matters relating to control, authorization, and registration of medicinal substances

- Implement any other function relating to the regulation of medicinal substances

Please note: Kenya is party to the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing ( KEN-3 ), which may have implications for studies of investigational products developed using certain non-human genetic resources (e.g., plants, animals, and microbes). For more information, see KEN-15 .

National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation

As delineated in the STI-Act and G-ECBiomedRes , in addition to obtaining the PPB’s permission to conduct research in Kenya, the principal investigator or the head of a research institution must obtain a favorable opinion from an ethics committee accredited by NACOSTI and a NACOSTI research license prior to initiating a study. NACOSTI’s role is to regulate and ensure quality in the science, technology, and innovation sector, and to advise the Kenyan government on related matters. According to Part II of the STI-Act , NACOSTI has specific research coordination and oversight functions, and it liaises with the National Innovation Agency and the National Research Fund to ensure funding and implementation of prioritized research programs. See KEN-32 for more information about NACOSTI’s mandate and functions.

Contact Information

According to the G-KenyaCT and KEN-22 , the PPB contact information is as follows:

Pharmacy and Poisons Board P.O. Box 27663 - 00506 Lenana Road Opp. DOD Nairobi, Kenya

Telephone: (+254) 02 3562107/2716905/6; (+254) 733 884411 / 720 608811; and ( +254) 709 770 100 or (+254) 709 770 xxx (where xxx represents the extension of the officer or office) Fax: +254-02-2713431

Email: [email protected] or [email protected] For Clinical Trials Inquiries: [email protected]

According to KEN-29 , the NACOSTI contact information is as follows:

National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation off Waiyaki, Upper Kabete P. O. Box 30623 00100 Nairobi, Kenya

Phone (landline): (+254) 020 4007000, (+254) 020 8001077 Phone (mobile): 0713 788 787 / 0735 404 245

Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

In accordance with the PPA , the CTRules , the G-KenyaCT , and KEN-21 , Kenya’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) , together with its Expert Committee on Clinical Trials (ECCT), is responsible for reviewing, evaluating, and approving applications for clinical trials using registered or unregistered investigational products (IPs). The G-KenyaCT specifies that the scope of the PPB’s assessment includes all clinical trials (Phases I-IV). As delineated in the CTRules , the G-KenyaCT , and KEN-21 , the PPB review and approval process may not be conducted in parallel with the ethics committee (EC) review. Rather, EC approval must be obtained prior to applying for PPB approval. As delineated in the STI-Act and G-ECBiomedRes , the principal investigator or the head of a research institution must obtain a favorable opinion from an EC accredited by the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) and a NACOSTI research license prior to initiating a study.

Clinical Trial Review Process

Per the CTRules and the G-KenyaCT , the PPB, through the ECCT, communicates the decision to approve, request additional information, or reject the application to the sponsor or the representative in writing within 30 working days of receiving a valid application. The G-KenyaCT indicates that in the case of rejection, the applicant may appeal and provide additional information to satisfy PPB requirements. In specific cases, the PPB may decide to refer the matter to external experts for recommendation.

As specified in the G-KenyaCT , each ECCT member, prior to reviewing the application, will declare any conflict of interest in the study and should have no financial or personal interests, which could affect their impartiality. During the protocol review, the reviewers must use the standard criteria (including available clinical and non-clinical data etc.) defined by the PPB. Confidentiality must be maintained during the review. Per the CTRules and the G-KenyaCT , the PPB/ECCT’s review must consider:

- The reliability and robustness of the data generated in the clinical trial, taking account statistical approaches, design of the clinical trial, and methodology, including sample size and randomization, comparator, and endpoints

- Compliance with the requirements concerning the manufacturing and import of IPs and auxiliary medicinal products

- Compliance with the labelling requirements

- The completeness and adequateness of the investigator's brochure

Regarding protocol amendments, the CTRules and the G-KenyaCT stipulate that any new information affecting the conduct/management of the trial, safety of the participants, and manufacture of the IP necessitating changes to the protocol, consent form, and trial sites require immediate submission of the amended documents to PPB for review and approval. Arrangements must be in place to take appropriate urgent safety measures to protect participants against any immediate hazard where new events relating to the conduct of the trial, or the development of the IP are likely to affect the safety of the participants. A copy of a favorable opinion letter from the EC on record must be submitted with the request for approval of a proposed amendment to the PPB. PPB approval must be obtained for all substantial amendments. Minor amendments or administrative changes may be implemented after getting the EC’s approval, but a record of these amendments must be kept for possible inspection by the PPB. See Submission Process and Submission Content sections for additional details on amendment submissions. Also, see the G-KenyaCT for examples of substantial amendments.

In addition, per the G-KenyaCT , the sponsor or the representative is required to request approval annually from the PPB at least six (6) weeks prior to the expiration of the previous approval.

Per the CTRules and the G-KenyaCT , the PPB may withdraw the authorization to conduct a clinical trial if it finds that the safety of the participants in the trial is compromised or that the scientific reasons for conducting the trial have changed. Additionally, per the CTRules , the PPB may revoke the approval if it determines that the IP has expired or is not usable.

As delineated in the G-KenyaCT , the PPB may inspect clinical trial sites to ensure that the generally accepted principles of good clinical practice (GCP) are met. The objectives of the inspection are to:

- Ensure that participants are not subjected to undue risks and that their rights, safety, and wellbeing are protected

- Validate the quality of the data generated

- Investigate complaints

- Verify the accuracy and reliability of clinical trial data submitted to the PPB in support of research or marketing applications

- Assess compliance with PPB guidelines and regulations governing the conduct of clinical trials

- Provide real-time assessment of ongoing trials

Per CRO-Inspect , the PPB is responsible for inspecting clinical trial and bioequivalence study sites that generate data for registration of medicines. The PPB requires that these sponsor and contract research organization sites comply with applicable good practices, including GCP, good laboratory practice (GLP), and good documentation practices. Based on risk assessments, the PPB will determine compliance with generally accepted good practice through inspections and, where appropriate, document reviews. In addition, see Cert-Emrgcy for information about GCP and good manufacturing practice certifications during emergencies.

Special Circumstances and Public Health Emergencies

The CTRules delineates that the PPB may, in special circumstances, authorize the conduct of a clinical trials under fast-track procedures or non-routine procedures. PPB may recognize and use clinical trial decisions, reports, or information from other competent authorities authorizing fast-track clinical trials. The special circumstances may include:

- A public health emergency

- The rapid spread of an epidemic disease

- Any other circumstance as may be determined by the PPB

The G-KenyaCT outlines PPB’s scope of assessment of a clinical trial application during a public health emergency. The PPB will conduct an expedited review and liaise with relevant stakeholders (including relevant ECs and other oversight bodies) to facilitate a holistic review of an application in a fast-track manner. The following prioritization criteria must be applied in the selection of applications for expedited review:

- Epidemiology of the emergency

- Morbidity and mortality associated with the emergency and/or condition under study

- Supporting scientific data/information available for the IP at the time of submission

- Feasibility of the implementation of the trial design within the context of the emergency

- Benefit impact of the intervention and/or trial design

In addition, PPB’s assessment will consider the following:

- The research does not compromise the response to an outbreak or appropriate care

- Studies are designed to yield scientifically valid results under the challenging and often rapidly evolving conditions of disasters and disease outbreak

- The research is responsive to the health needs or priorities of the disaster victims and affected communities and cannot be conducted outside a disaster situation

- The participants are selected fairly and adequate justification is given when particular populations are targeted or excluded, for example, health workers

- The potential burdens and benefits of research participation and the possible benefits of the research are equitably distributed

- The risks and potential individual benefits of experimental interventions are assessed realistically, especially when they are in the early phases of development

- Communities are actively engaged in study planning to ensure cultural sensitivity, while recognizing and addressing the associated practical challenges

- The individual informed consent of participants is obtained from individuals capable of giving informed consent

- Research results are disseminated, data are shared, and any effective interventions developed or knowledge generated are made available to the affected communities

STI-Act stipulates that NACOSTI issues research licenses if it finds that the conduct of the research is beneficial to the country and will not adversely affect any aspect of the nature, environment, or security of the country. The license issued will have NACOSTI’s seal and will indicate the commencement and expiration of the research. In addition, NACOSTI maintains a register of all persons granted a license, which is available for public inspection during normal working hours free of charge.

KEN-31 states that if a research license application does not meet the conditions required under the STI-Act , NACOSTI must reject the application and communicate the reasons to the applicant. Any person may appeal NACOSTI’s decision to the Cabinet Secretary within 30 days of being notified of the decision. For approved research, NACOSTI may conduct an evaluation to assess compliance with the conditions of the license. If the research project has not been completed within the stipulated period, the researcher may apply for renewal of the license and pay the requisite fee. The researcher is expected to apply for renewal by attaching a progress report instead of a proposal. KEN-31 indicates that the duration of the research license is one (1) year.

Per the PPA and the G-KenyaCT , the sponsor or the representative is responsible for paying a fee to the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) to submit a clinical trial application for authorization. The PPB currently requires a non-refundable application fee of $1,000 USD, or the equivalent in Kenya Shillings at the prevailing bank rates.

Payment Instructions

As stated in Annex 2 of the G-KenyaCT , payment is to be made by a bank check payable to the “Pharmacy and Poisons Board” and presented to the PPB’s accounts office upon submitting the application.

Payment can also be made by electronic fund transfer (EFT) to the PPB Bank account, if required. The sponsor or the representative is responsible for all bank charges associated with the EFT. Details of the EFT payment should be obtained from the PPB prior to initiating such a transaction.

As delineated in KEN-31 , the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) charges a fee that varies depending on the applicant’s status as Kenyan or non-Kenyan, and standing as a researcher (i.e., student, public/private institution, private company). The fees are non-refundable and apply for research license renewals. Details on additional requirements are provided in the Submission Content section.

- Student, Undergraduate/Diploma: East African Community (EAC) Countries – 100 Kenya Shillings; Kenyan Citizens – 100 Kenya Shillings; Rest of Africa – 200 Kenya Shillings; Non-Africans - $150 USD

- Research (Masters): EAC Countries – 1,000 Kenya Shillings; Kenyan Citizens – 1,000 Kenya Shillings; Rest of Africa – 2,000 Kenya Shillings; Non-Africans - $350 USD

- Research (PhD): EAC Countries – 2,000 Kenya Shillings; Kenyan Citizens – 2,000 Kenya Shillings; Rest of Africa – 4,000 Kenya Shillings; Non-Africans - $400 USD

- Post-Doctoral: EAC Countries – 5,000 Kenya Shillings; Kenyan Citizens – 5,000 Kenya Shillings; Rest of Africa – 10,000 Kenya Shillings; Non-Africans - $500 USD

- Public Institutions: Kenyan Citizens – 10,000 Kenya Shillings

- Private Institutions, Commercial/Market Research, Companies: Kenyan Citizens – 20,000 Kenya Shillings

KEN-31 indicates that the applicant must submit the research license application online through the Research Information Management System (RIMS) ( KEN-24 ). Applicants should pay the applicable fee through mobile money transfer or direct bank deposit.

As per KEN-31 , East African citizens have two (2) options for payment to the Kenya Shillings Account: 1) mobile money transfer or 2) direct bank deposit.

Mobile money transfer payments should be made via Mpesa Express. Payment using this method will be made after initiating the application process. The system will prompt the applicant to make the payment.

Direct bank deposits should be made to:

Kenya Commercial Bank Branch: Kipande House Account Name: National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation Account Number: 1104162547 Swift Code: KCBLKENX Transaction Description: Research License Fee

Non-Kenyans should use the following U.S. Dollar Account:

NCBA Bank Branch: City Centre Account Name: National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation Account Number: 2904970067 Swift Code: CBAFKENX Transaction Description: Research License Fee

As per the G-KenyaCT , the G-ECBiomedRes , and KEN-30 , Kenya requires an independent review of research through a National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) -accredited ethics committee (EC) in one (1) of the local institutions charged with the responsibility of conducting research in human participants. KEN-25 provides a list of the accredited institutional ECs.

Ethics Committee Composition

As delineated in the G-ECAccred , institutional ECs should consist of at least seven (7) members, or an odd number above seven (7). The G-ECBiomedRes states that these members should be multidisciplinary and multisectoral in composition, collectively encompass relevant scientific expertise, balanced age and gender distribution, and include laypersons representing community interests and concerns. Per the G-ECAccred , the composition should meet the following requirements:

- At least one (1) member with knowledge and understanding of Kenyan law

- At least one-third of the members must be female, and one-third must be male

- At least one (1) member who is unaffiliated with the institution

- At least two (2) members must have research expertise and experience, one (1) of whom must be in the health field

- At least one (1) member must be a lay member

- For ECs reviewing clinical research, at least two (2) members must be clinicians, one (1) of whom is currently in active practice or clinical research

- Reflect the regional and ethnic diversity of the people of Kenya

The chairperson must also have some basic training and/or experience in bioethics and leadership. All EC appointments are the responsibility of the institution’s administrative head. See the G-ECAccred and the G-ECBiomedRes for detailed institutional EC requirements.

Terms of Reference, Review Procedures, and Meeting Schedule

Per G-ECBiomedRes , ECs need to have independence from political, institutional, professional, and market influences. As delineated in the G-ECAccred , the G-ECBiomedRes , and the STI-Regs , institutional ECs must operate within written standard operating procedures (SOPs) which delineate the EC’s process for conducting reviews. Per the G-ECAccred , SOPs should include but are not limited to information on EC scope, responsibility, and objectives, institutions served, committee functions, terms and conditions of member appointment, business procedures including meeting schedules and types of reviews, documentation, recordkeeping, and archiving procedures, quorum requirements, communication procedures, and complaint process and dispute resolution procedures. Per the G-ECAccred and the STI-Regs , these documents must be provided to NACOSTI.

Per the G-ECAccred , the quorum for NACOSTI-accredited EC meetings must be:

- At least 50 percent of the membership must form the quorum

- A lay person must be present in all meetings

- For ECs reviewing clinical research, at least two (2) members must be clinicians, one (1) of whom is currently in active practice or clinical research.

The G-ECBiomedRes also defines quorum requirements:

- The minimum number of members required to compose a quorum (e.g., more than half the members)

- The professional qualifications requirements (e.g., physician, lawyer, statistician, paramedical, or layperson) and the distribution of those requirements over the quorum; no quorum should consist entirely of members of one (1) profession or one (1) gender; a quorum should include at least one (1) member whose primary area of expertise is in a non-scientific area, and at least one (1) member who is independent of the institution/research site

Per G-ECBiomedRes , EC member terms of appointment should be established that include the duration of an appointment, the policy for the renewal of an appointment, the disqualification procedure, the resignation procedure, and the replacement procedure. A statement of the conditions of appointment should be drawn up that includes the following:

- A member should be willing to publicize their full name, profession, and affiliation

- All reimbursement for work and expenses, if any, within or related to an EC should be recorded and made available to the public upon request

- A member should sign a confidentiality agreement regarding meeting deliberations, applications, information on research participants, and related matters

Regarding training, EC members should have initial and continued education regarding the ethics and science of biomedical research. The conditions of appointment should indicate the availability and requirements of introductory training, as well as on-going continuing education. This education may be linked to cooperative arrangements with other ECs in the area, country, and region.

For detailed institutional EC requirements and information on other administrative processes, see the G-ECAccred and the G-ECBiomedRes . See KEN-17 and KEN-26 for examples of accredited EC submission and review guidelines.

According to G-ECBiomedRes , the primary scope of information assessed by the institutional ethics committees (ECs) relates to maintaining and protecting the dignity and rights of research participants and ensuring their safety throughout their participation in a clinical trial. The G-ECAccred further states that the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) accredits ECs in order to uphold the standard of ethics review in the country; develop public confidence and trust in the national research system; facilitate equitable access to research and human health records in health facilities; and facilitate coordination and collaboration among ECs. See the G-ECAccred and the G-ECBiomedRes for detailed ethical review guidelines.

Role in Clinical Trial Approval Process

As per the G-KenyaCT and KEN-21 , the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) ’s review and approval of a clinical trial application is dependent upon obtaining approval by an accredited institutional EC. Consequently, the PPB and EC reviews may not be conducted in parallel.

As set forth in the G-ECBiomedRes , ECs must be constituted to ensure an independent and competent review and evaluation of all ethical aspects of clinical trials. ECs must review research involving human participants to ensure they meet these ethical principles:

- Respect for persons, including respect of autonomy, protection of vulnerable groups, and protection of privacy and confidentiality

- Beneficence

- Justice, which in research means equitable distribution of the benefits and the burdens

For additional details on the principles and benchmarks for ethical review, see G-ECBiomedRes .

Per the G-ECBiomedRes , expedited review may be permitted for protocols involving no more than minimal risk to research participants.

The G-ECBiomedRes indicates that all ECs should carry out regular monitoring of approved protocols involving human participants. In case of any adverse events, the EC should report this immediately to Kenya’s National Bioethics Committee (NBC).

Per the G-ECBiomedRes , with collaborative research projects, the collaborating investigators, institutions, and countries must function as equal partners with safeguards to avoid exploitation of local researchers and participants. An external sponsoring agency should submit the research protocol to their country’s EC, as well as the Kenyan EC where the research is to be conducted. Further, this research must be responsive to the health needs of Kenya and reasonably accessible to the community in which the research was conducted. Consideration should be given to the sponsoring agency agreeing to maintain health services and faculties established for the purposes of the study in Kenya after the research has been completed. Such collaborative research must have a local/Kenyan co-principal investigator.

As per the G-KenyaCT , G-ECBiomedRes , and KEN-30 , Kenya requires an independent review of research through a National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) -accredited ethics committee (EC) in one (1) of the local institutions charged with the responsibility of conducting research in human participants. The EC fee to review a clinical trial application will vary depending on the institution. See KEN-25 for a list of NACOSTI-accredited institutional ECs. For an example of institutional fee requirements charged by the Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU) at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) , see KEN-27 .

As set forth in the STI-Act and KEN-32 , the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) is the central body responsible for the oversight, promotion, and coordination of research. NACOSTI’s role is to regulate and ensure quality in the science, technology, and innovation sector, and to advise the Kenyan government on related matters. As per the G-ECAccred , NACOSTI has delegated the task of reviewing research proposals for ethical clearance to accredited institutional ethics committees (ECs) to ensure that research conducted in the country observes high research ethics standards.

Per the G-ECBiomedRes , Kenya's National Bioethics Committee (NBC) advises NACOSTI on research ethics. In addition, NBC offers dispute resolution if an applicant is dissatisfied with the decision of an EC. Finally, the NBC must terminate research at any stage if it is found to be harmful to the participants.

Registration, Auditing, and Accreditation

As per the STI-Regs and the G-ECAccred , NACOSTI is responsible for accrediting institutional ECs. Per the G-ECAccred , the application requirements for accreditation are:

- A completed application form ( KEN-10 or Annex III of the G-ECAccred )

- Copy of the standard operating procedures (SOPs)

- Copies of abridged curriculum vitaes (CVs) (no more than four (4) pages) for each member of the proposed EC (including the training attended)

- Profile of the organization/institution detailing the areas of competence (no more than four (4) pages)

Per the G-ECAccred , NACOSTI issues a certificate of accreditation to accredited institutional ECs, which is valid for three (3) years from the date of NACOSTI’s notification. All accredited ECs must submit annual reports to NACOSTI by July 31st for review and monitoring. Applications for renewal of accreditation should be made six (6) months before expiry of the accreditation period. Failure to renew accreditation or failure to maintain the appropriate standards for continuity of accreditation will mean that the accredited status of the EC will lapse at the end of the current accreditation period. Accreditation must be terminated if the accredited committee fails to maintain the required standards. For re-accreditation review purposes, ECs must provide the SOPs under which they will operate. The SOPs are not required as part of the annual reporting process, unless they have been amended, but are required to be stated/included for the reaccreditation review process (every three (3) years). See the G-ECAccred for additional details on the accreditation process.

In accordance with the PPA , the STI-Act , the CTRules , the G-KenyaCT , the G-ECBiomedRes , KEN-21 , and KEN-16 , Kenya requires the sponsor or the representative to obtain clinical trial authorization from the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) ’s Expert Committee on Clinical Trials (ECCT) and an independent ethics review through a National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) -accredited ethics committee (EC) in a local institution. In addition, the STI-Act and KEN-31 specify that applicants must obtain a research license from NACOSTI prior to initiating a study. The G-KenyaCT also states that the PPB review and approval process may not be conducted in parallel with the EC review. EC approval must be obtained prior to applying for PPB approval.

Regulatory Submission

As described in the G-KenyaCT and KEN-16 , the sponsor or the representative is expected to submit the clinical trial application electronically via the PPB online system ( KEN-16 ). The clinical trial application form is available in the online system ( KEN-16 ). Per the G-KenyaCT , in the event of a multicenter clinical trial, the sponsor should only file one (1) application to the PPB. According to KEN-34 , all application documents should be signed, dated, and version referenced, if applicable, and should be in English. See Annex 7 of the G-KenyaCT to view a flowchart of the submission and approval process.

The G-KenyaCT indicates that when an application for a clinical trial is accepted, an acknowledgement of receipt will be issued with a reference number for each application. This PPB/ECCT reference number must be quoted in all correspondence concerning the application in the future. This will be communicated through email to the applicant or through KEN-16 .

Per the G-KenyaCT , sponsors (applicants) can request pre-submission meetings with the PPB to discuss pertinent issues prior to formal submissions. The request must be made in an official letter and include the following information:

- Background information on the disease to be treated

- Background information on the product

- Quality development

- Non-clinical development

- Clinical development

- Regulatory status

- Rationale for seeking advice

- Proposed questions and applicant’s positions

In addition, the letter must be addressed to the Chief Executive Officer of the PPB and sent to [email protected] and copied to [email protected] . The request for a meeting should propose two (2) different dates for the meeting with the proposed dates being at least three (3) weeks away.

Per G-KenyaCT , any new information that affects the conduct/management of the trial, safety of the participants, and manufacture of the product necessitating changes to the protocol, consent form, and trial sites, etc. will require immediate submission of the amended documents to the PPB for review and approval. Minor amendments or administrative changes may be implemented after getting the EC’s approval, but a record of these amendments must be kept for possible inspection by the PPB.

National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation

Per KEN-31 , an application for a NACOSTI research license should be submitted online via the Research Information Management System (RIMS) ( KEN-24 ).

Ethics Review Submission

Each institutional EC has its own required submission procedures, which can differ significantly regarding the application format and number of copies. See KEN-17 for an example of a NACOSTI-accredited EC’s guidelines.

Regulatory Authority Requirements

As per the CTRules , the G-KenyaCT , and KEN-34 , the following documentation must be submitted (signed, dated, and version referenced) to the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) (Note: the sources provide overlapping and unique elements so each of the items listed below will not necessarily be in each source):

- Cover letter

- Study protocol

- Proof of study registration in the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry ( KEN-19 )

- Patient information leaflet and informed consent form (ICF)

- Investigators brochure (IB) and package inserts

- Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD), including stability data for the investigational product (IP)

- Adequate data and information on previous studies and phases to support the current study

- Good manufacturing practice (GMP) certificate of the IP from the site of manufacture issued by a competent health authority in the manufacturer’s jurisdiction of origin

- Certificate of analysis of the IP

- Pictorial sample of the IPs, including the labeling text

- Signed investigator(s) curriculum vitae(s) (CV(s)), including that of the study pharmacist (the CV should include the current workload of the principal investigator (PI))

- Evidence of contractual agreement between the relevant parties

- Evidence of recent good clinical practice (GCP) training of the core study staff

- Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) information, including the charter, composition, and meeting schedule

- Detailed study budget

- Financial declaration by the sponsor and PI ( KEN-2 and Annex 5 of the G-KenyaCT )

- No conflict of interest declaration by the sponsor and PI

- Signed declarations by the sponsor, PI, and the monitor that the study will be carried out according to the protocol and applicable laws, regulations, and GCP requirements ( KEN-1 and Annex 4 of the G-KenyaCT )

- Indemnity cover for PI, investigators, and study pharmacist

- Clinical trials insurance cover for the study participants

- Copy of favorable opinion letter from local ethics committee (EC)

- Copy of current practice licenses for the investigators and study pharmacist

- Copy of approval letter(s) from collaborating institutions or other regulatory authorities, if applicable

- For multicenter/multi-site studies, an addendum for each of the proposed sites including, among other things, the sites’ capacity to carry out the study (e.g., personnel, equipment, laboratory)

- A signed statement by the applicant indicating that all information contained in, or referenced by, the application is complete and accurate, and is not false or misleading (Annex 4 of the G-KenyaCT )

- Payment of fees

- Statistical analysis plan

- A signed checklist ( KEN-34 and Annex 2 of the G-KenyaCT )

Per the G-KenyaCT , a request for approval of an amendment must include a summary of the proposed amendments; the reason for the amendment; the impact of the amendment on the original study objectives; the impact of the amendments on the study endpoints and data generated; and the impact of the proposed amendments on the safety and wellbeing of study participants.

KEN-35 describes the submission content for requesting annual approval from the PPB.

Per the STI-Regs and KEN-31 , non-Kenyan applicants must be affiliated with a Kenyan institution. Per KEN-31 , applicants must apply online through National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) ’s Research Information Management System (RIMS) website ( KEN-24 ) and upload the following:

- Passport size color photo in JPG or PNG format

- Scanned ID/passport in PDF format

- Introductory letter from relevant institution signed by an authorized officer

- Affiliation letter from relevant local institution for foreigners signed by an authorized officer and valid for one (1) year

- Grant letter from the funding agency to support the amount indicated for the research’s funding

- PPB clinical trial approval

- Prior Informed Consent (PIC), Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT), or Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) where applicable, for applications to conduct research on genetic resources and derivatives

- Approved research proposal in PDF format

- Certificate of ethical clearance of the research (see list of accredited ECs in KEN-25 )

- Evidence of payment as the last page of the uploaded proposal

Per KEN-31 , the following conditions apply to the research license:

- The research license is valid for the proposed research, site, and specified period

- Both the research license and any rights thereunder are non-transferable

- NACOSTI may monitor and evaluate the research

- The licensee must inform the relevant County Director of Education, County Commissioner, and County Governor before research commencement

- Excavation, filming, and collection of specimens are subject to further permissions from relevant government agencies

- The research license does not give authority to transfer research materials

- The licensee shall submit one (1) hard copy and upload a soft copy of their final report within one (1) year of completion of the research

- NACOSTI reserves the right to modify the conditions of the research license including its cancellation without prior notice

KEN-31 states that if the research is not completed within the stipulated period, the applicant may apply for renewal of the research license and pay the requisite fee. A progress report should be submitted with the request for renewal instead of a proposal. The progress report must indicate the objectives and activities that have been accomplished, as well as the research work that has yet to be undertaken. KEN-31 further indicates that submissions requesting renewal should be made at least 30 days prior to the expiration of the approval period.

Ethics Committee Requirements

EC requirements vary depending on the specific EC. Examples of NACOSTI-accredited EC requirements are delineated in the Ethics and Research Application Form ( KEN-9 ) used by the Kenyatta National Hospital-University of Nairobi (KNH-UoN) Ethics and Research Committee and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) . As specified in KEN-9 , the following documentation is required to obtain ethics approval from these two (2) ECs:

- Three (3) copies of the application form (including at least one (1) copy with original linked signatures)

- Three (3) copies of relevant documentation (ICFs, questionnaires, data instruments, drug information summary, data collection forms, debriefing statements, advertisements, etc.)

- Three (3) copies of protocol and grant/contract

- One (1) copy of protocol and IB for trials

- Three (3) copies of thesis/dissertation proposal, where applicable to students

- PI name and contact information

- Project title

- Research personnel

- Funding information

- Project description

- Methodology and procedures

- Participants description (e.g., selection/withdrawal criteria and treatment)

- Risk benefits and adverse events (See Safety Reporting section for additional information)

- Research data confidentiality

- Consent/assent forms and waiver

As set forth in the G-ECBiomedRes , a foreign sponsoring agency must also submit its research protocol for ethics review according to its own country’s standards. This research must be responsive to the health needs of Kenya and reasonably accessible to the community in which the research was conducted.

Clinical Protocol

Per the G-KenyaCT , research must be conducted in accordance with requirements set forth in the International Council for Harmonisation's Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2) ( KEN-14 ). The CTRules the G-KenyaCT , the G-ECBiomedRes , and KEN-14 outline the key elements of a research protocol in Kenya (Note: the sources provide overlapping and unique elements so each of the items listed below will not necessarily be in each source.):

- A project title that adequately captures the essence of the study

- The names, addresses, signatures, and updated abridged curriculum vitae of the investigators

- Evidence that the PI has prior training in good clinical practice

- Contact information for the EC and collaborating institutions

- A summary of the project

- Introduction, background, and literature review, including nonclinical data

- Study objectives, rationale, questions, and hypothesis/es

- Study site, design, and methodology

- Ethical considerations

- Role of investigators

- Publication policy

- Consent explanation - elements of consent explanations

- ICF with signature provisions for participants and the PIs

- Risks and benefits

- Mode of assessment of the safety and efficacy of the IP

- Mode of collecting, analyzing, and reporting the statistics of the clinical trial

- Source data documents of the clinical trial

- Quality control and quality assurance

- Confidentiality

- Recruitment, selection, treatment, and withdrawal of participants

- Compensation and post-trial access program

- Undue inducement and coercion

- Voluntariness

- Alternative treatment(s) if available

- Storage of specimens

- MTA, where applicable

- Data management and statistical analysis

In addition, per the G-KenyaCT , the protocol should have a clear description of study stoppage rules indicating reasons, who makes the decision, and how the decision will be communicated to the PPB and the EC.

Based on the CTRules and the G-KenyaCT , the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) 's review and approval of an application to conduct a clinical trial is dependent upon obtaining ethics approval from a National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) -accredited ethics committee (EC) . Therefore, the PPB and EC reviews may not be conducted in parallel. In addition, the STI-Act and KEN-31 specify that all applicants must obtain a research license from NACOSTI prior to initiating a study.

Regulatory Authority Approval

Per the G-KenyaCT , sponsors (or applicants) can request pre-submission meetings to discuss pertinent issues prior to formal submissions. The request must be made in an official letter addressed to the Chief Executive Officer of the PPB and sent to [email protected] and copied to [email protected] . The request for a meeting should propose two (2) different dates for the meeting with the proposed dates being at least three (3) weeks away. (See Submission Process section for details on the content of request.)

Per the G-KenyaCT , upon receipt of a clinical trial application, the PPB’s Clinical Trial Directorate of Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance screens the application package for completeness, which takes five (5) days. If accepted, the sponsor or the representative is issued an acknowledgement of receipt. If additional information is needed, the sponsor will have 10 days to respond. The PPB aims to respond to applications within 30 working days. The sponsor or the representative must reference the PPB/Expert Committee on Clinical Trials (ECCT) number in all future application-related correspondence. The application is then evaluated by the ECCT and PPB staff according to their respective standard operating procedures. The PPB/ECCT’s decision to approve, request additional information, or reject the application is communicated to the sponsor or the representative in writing within 30 days of receiving a valid application. If additional information is requested, the sponsor has 90 days to respond after which the PPB has 15 days to issue a final decision. In certain cases, the PPB may refer the application to external experts for their recommendation.